ABSTRACT

Digital Arts – Refugee Engagement (DA-RE) is an exploratory research partnership between refugee youth, academics, practitioners and community activists. Arts-based activities were combined with digital literacy to develop the capabilities of refugee youth in Turkey and Bangladesh. DA-RE’s participants co-created digital arts and connected with one another across the two settings in a digital third space to share narratives from their situated perspectives and lived experiences. In these ways, they developed skills of engagement and agency through the project, but at the heart of DA-RE was the intention to explore the links between refugee youths’ own creative agency, harnessed in new contexts enabled by the project, and their existing digital literacies. DA-RE sought to identify, with a theory of change, potential opportunities for refugee youth to both use this capability in the host community and provide a platform for their digital arts to offer a counter-narrative to ‘othering’ discourses at work in both their host communities and in the UK, where the project was coordinated, in so doing converting (digital) literacy into capability with positive consequences for social good.

Introduction

Digital Arts – Refugee Engagement (DA-RE) is a research project conducted by a partnership of refugee youth, academics, practitioners and activists from Turkey, Bangladesh and the UK. The research was undertaken by Bournemouth University, UK, University of Chittagong, Bangladesh, Maltepe University and Gate of Sun in Turkey. DA-RE was further supported by academic advisers from London College of Communication and University of Derby, UK. DA-RE was conducted across two centres of activity, a refugee camp in Bangladesh and a social enterprise working with refugees in Turkey ().

In Bangladesh, the University of Chittagong led activities in the Kutupalang and Balukhali Rohingya refugees camps located in Ukhia, a sub- district of Cox’s Bazar, considered the world’s largest refugee camp. The Rohingya is an ethno-linguistic and religious minority and Bangladesh hosts about 1.3 million Rohingya refugees in Ukhia and Teknaf, two sub-districts of Cox’s Bazar.

In Turkey, DA-RE formed a partnership between refugee youth participants, Maltepe University and Gate Of Sun. The highest number of the world’s refugees come from Syria since 2016 and many have fled into Turkey, which hosts the largest number of Syrian refugees in the world, some 3.6 million people (Safak-Ayvazoglu and Kunuroglu Citation2021). Gate of Sun is a social enterprise that serves as a film production house and an open space for cultural exchange in Gaziantep, Turkey. It aims to improve social cohesion among host and guest communities by producing audio-visual art with artists and filmmakers and providing co-working spaces and equipment. Maltepe University’s Research and Application Center for Street-Involved Children (SOYAÇ) brings together refugee youth and university students to create an inclusive, therapeutic community of actively participating university students, faculty members and any other interested stakeholders in which all members focus on non-hierarchical compassion.

Across the two settings, DA-RE’s participants’ motivations to be artivists were varied but consistent in their seeing the potential for participation in the project to not only increase exposure to their creative works but also to offer counter-narratives. The Bangladesh project team was comprised of young refugee Rohingya painters, photographers, youtubers, social media activists, musicians and digital storytellers, a Rohingya youth research assistant and four anthropology graduates from the host community who were already trained and skilled in the documentation of refugee art-based activities. In Turkey, the participants working with DA-RE produced 10 digital art works, including short films, music video, podcasts, animations, blogs and digital journalism. In total, the sample of refugee youth participants across the settings consisted of 25, 12 from Bangladesh, aged between 18 and 25 (10 male, 2 female) and 13 from Turkey, aged between 18 and 30 (9 male, 4 female). The gender imbalance was an important aspect and is given due prominence later in the article.

In both settings, the project did not intend to ‘teach’ digital literacy. Instead, researchers worked with a more ‘dynamic’ and negotiated concept of literacy and, in order to do so, aimed to facilitate a ‘third space’ in which we could understand refugee youths’ existing digital literacies and combine these with good practices in the use of arts- based approaches for learning, narrating and voicing their lived experiences and future aspirations. These concepts will next be explained in the conceptual framework for DA-RE.

Conceptual framework

Crucial to solidarity—digital or non—is the ability to listen beyond, despite and across borders. (Marino Citation2021, 177)

Digital literacies

By understanding the existing digital literacies of the participants from the outset, the study was able to focus on developing capabilities from these literacies, informed by the work of Sen (Citation2008) and through a theory of change for digital literacy which consisted of four elements – access, awareness, capability and consequences (McDougall and Rega Citation2022). Our use of a theory of change was in recognition that creative practice and arts-led research projects can struggle to evidence impact, and subsequently that ‘The adoption of a theory of change approach enables creative practice researchers to evidence aspirations or intentions just as well as concrete outcomes … and provides a language to narrate their stories and articulate value in terms they understand.’ (Boulil and Hanney Citation2022, 127)

We could see that our participants had, despite their circumstances, already high levels of access (the means to be included as an individual in the full digital ecosystem, through technological access and the skills to use the technology). Through the project, the intention was to develop further, through the work they developed and the reflections they shared, their levels of awareness of how digital content and online information re-present people, places, news and issues from particular points of view with particular intentions and how the digital environment we are engaging with is created and constructed, including who has a voice. Therefore, in terms of generating new outcomes through and in the project itself, DA-RE was seeking to work at the more agentive levels of capability and consequences. Capability happens when people use their access to media and digital information, digital skills and awareness of digital ecosystems to use their digital literacies for particular purposes in their lives. This capability can also lead to new forms of civic engagement through digital technology, improved employability through creativity and / or digital skills or resolving specific problems However, there is no innate reason why this capability will lead to people using their digital literacies for social good unless this is combined with consequences – the development of digital literacy capability into positive change. Consequences in particular ways, through the conversion of capability into positive change, requiring an active desire for our media to promote equality and social justice. Far from being the inevitable outcome of digital literacy, the evidence suggests the opposite. Polarising discourse, ‘othering’ representations, misinformation and conspiracy narratives are often produced by the digitally literate.

Third space

The distinction between capability and consequences can be subtle or nuanced, but it is about the uses of digital literacy, the intention to use capability in a positive way, informed by an understanding of digital society and the harms caused by information disorder and discursive othering in increasing marginalisation. For example, Syrian artists lack opportunities to express themselves through art in the host community in Turkey and the long war in Syria has created new challenges for artivists who were already not supported by their community before the war. To address such barriers to visibility, placing emphasis on digital literacy as a form of context-bound civic capability as opposed to a set of neutral, universal competences was put into practice in DA-RE with transferable ‘third space’’ design principles, informed by previous work (Rega and McDougall Citation2021) rather than by importing a model. However, in addressing both the emerging proof of concept from DA-RE and the tensions and challenges in play in the motivating imperatives of such a partnership, this study also speaks to the complexity of combining digital literacy with arts and ideas of ‘engagement’ within such third spaces.

DA-RE’s hypothesis was that where refugee youth’s existing digital literacies can be harnessed in combination with arts- based methods, it can be possible to generate this rich ‘third space’ for meaning-making:

This third space involves a simultaneous coming and going in a borderland zone between different modes of action. A prerequisite for this is that we must believe that we can inhabit these different sites, making each a space of relative comfort. To do so will require inventing creative ways to cross perceived and real “borders.” The third space is thus a place of invention and transformational encounters, a dynamic in-between space that is imbued with the traces, relays, ambivalences, ambiguities and contradictions, with the feelings and practices of both sites, to fashion something different, unexpected. (Bhabha Citation1994, 406).

Third Spaces for digital arts literacy work involve the reciprocal exchange of aspects of the ‘first space’ of everyday living literacy practices with an impactful unsettling of the ‘second spaces’ of formalised research, with the ultimate goal being to make the research experience itself a third space. This is at once very different to ways of thinking about literacy which fix levels and competences to be taught and learned, this dynamic, ‘productively unsettled’ understanding is always more negotiated and ideological. This way of both working in (third) space and thinking about digital literacy can, in turn, converge to facilitate a ‘safe space’ for equality, diversity and inclusion and inter-cultural understanding between refugees and host communities through reciprocal knowledge exchanges; pluralist and counter-hegemonic media production and digital storytelling providing ‘the partial promise of voice’ (Dreher Citation2012) for seldom heard or ‘marginalised’ groups. Such a safe third space must be characterised by a combination of guidance and participation, as Bademci and Karadayi’s previous work has found:

Guided participation refers to the process and systems of involvement between people as they communicate and coordinate efforts while participating in culturally valued activity Within guided participation, newcomers to a socio-cultural community develop their understanding and skills through participation with others within culturally organised activities. (Bademci and Karadayi Citation2013, 166)

Digital arts

If digital arts activities have both the potential to enable refugee youth to express themselves and develop their existing digital skills, combining these into new forms of capability, then their artistic outputs, digitally circulated, have the potential to ‘change the story’ to generate self-efficacy and engage audiences in an alternative discourse than one of refugees, migrants and asylum seekers as passive and silenced, or dangerous and ‘other’:

Art, poetry and storytelling can all be used as a springboard for developing alternative discourses of asylum and reaching broader audiences (O’Neill and Hubbard Citation2012, 12).

Where this third space intersection of digital literacies and art-based activities can develop inter-cultural, participatory and community media production, this resonates also with approaches from action learning and postcolonial and indigenous epistemologies (see Manyozo Citation2013, 19–20). Neag and Supa (Citation2020) conducted social media ethnography conducted with young refugees from African and Middle Eastern countries living in Europe:

The social media ethnography, through open coding and thematic analysis, identified four emerging themes relevant to our research on migration and emotions. These are: (1) new places and social connections; (2) purpose lost and found; (3) transition, longing and belonging; and (4) co-presence, support and local identity. (Citation2020, 773)

Methods and ethics

The refugee youth in the two settings worked with practitioners, research assistants and academics in participant-led research with the outcomes providing us with a focussed ethnography of the emerging narratives, reflections and identity-negotiations brought to the surface by artistic and performative exchanges, enhanced and shared across space and time through digital technology.

DA-Re moved through three research stages. Firstly, an applied, targeted analysis of the findings from our (AHRC-funded) baseline development project was used to compare and synthesise the barriers to refugee youth engagement in Turkey and Bangladesh combined with a critical review of arts-based activities combined with digital literacy, both research- based and practitioner facilitated, involving refugee youth, drawing out best practice and successful implementation of arts, media and technology in supporting the capabilities of the participants. Crucially, the review was co-created with the new partners in the two settings to verify the conceptual framework. In phase 2 (Intervention), the digital arts activities were facilitated in the two settings, with exchanges between them at key points, and in stage 3 (exchange), the work was exhibited virtually, together with a live-streamed virtual event across the UK, Turkey and Bangladesh which was analysed as research data, along with participant interviews.

For the first stage baseline research, DA-RE researchers worked in two Rohingya refugee camps and the findings of this preparatory research showed that the Bangladeshi Government are resistant to the social and local integration of the Rohingya refugees. The Rohingya people are even not officially recognised as refugees in Bangladesh Despite these obstacles, many national and international NGOs are working in the 34 temporary camps and Rohingya Refugees have similar access to mobile networks as the host population in Ukhia and Teknaf of Cox’s Bazar. Participants of DA-RE in the Bangladesh Rohingya refugee camps were heavily engaged, selected through purposive sampling in social networking which has connected them with diaspora Rohingyas living across the world. Participants were linked with global rights activism and also commercial platforms for selling digital arts. However, as with the rest of Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees experience variable network coverage and device ownership in settlements and camps and there are also socio-cultural challenges associated with ‘inclusively’ connecting young refugee women among the Rohingyas.

In Turkey, a safe space was created for the youth with grounding exercises and experiential group meetings to explore refugee youth’s needs and expectations and ensure their sense of agency as the project unfolded. These grounding exercises (guided participation, see above) were reflective and partly therapeutic activities convened throughout the process of the digital arts productions. These were an important element, as those involved testify:

We were able to introduce you (the other people in the group, including the group facilitator and assistants) to Syria in a better way through our foods and songs. I wanted to watch my film with you. We created trust for each other on a deep level, we could share things very private/special to us.

My film narrates my story. When I joined these meetings, I was taking common points of everyone’s issues/troubles and adding them to the film. I will explain it with an example/a metaphor. People carry two things in their hands … Every week, I need to replace these two things, if I do not, then I cannot take new things. If I think about it, I cannot work the thing that I wanted. We are taking things all week and every week when you (referring to the group facilitator) ask about how our week was, then we are letting go of these things, we are emptying them. All week we are loading things and when we get together with you, we are discharging, leaving our loads. Without emptying the load of that week, I cannot perform my work. When we leave the meetings every week, we are able to think about our projects.

The ethical principles of the project were reflected in the research design which was crafted in collaboration with local partners with a long experience in working with refugees in Turkey and Bangladesh. Nasir Uddin and his team in the anthropology department of the university of Chittangong have been working alongside Rohingya refugees since their arrival in Bangladesh. Amr Aijouni is a Syrian refugee himself, who founded Gate of Sun, a creative social enterprise specialised in video production, and Ozden Bademci of Maltepe University has been active in supporting the psychological wellbeing of refugees and marginalised groups in her country. The objectives of DA-RE have therefore been negotiated from the outset with the various actors involved, the young participants in the project and two main desires emerged from the baseline assessment which informed DA-RE: (1) the need to have a platform that amplifies their artistic work in order to reach an international audience beyond the perimeter of the refugee camp (in Bangladesh) but also (2) the possibility to tell their stories to host communities (in Turkey), and these are the two main objectives around which DA-RE focused its activities. The aim of the project, working on capabilities related to digital and artistic literacies, was to mobilise the afore-mentioned existing aspirations in terms of consequences (related to contested dynamics between the concepts of voices and listening, as explained in the introduction of this article). The provision of the permanent virtual exhibition and the live event gathering international participations were conceived to directly respond these articulated needs.

To further situate DA-RE in a broader international development discourse in relation to Global Challenges and Sustainable Development Goals we can frame the project as directly addressing SDG10 (Reduce inequalities within and among countries), by providing a space for digital arts to offer a counter-narrative to ‘othering’ discourses at work in host communities and internationally, and therefore promoting reflection and critical thinking in the audience. Furthermore, the accounts provided in the artistic productions displayed in the virtual exhibitions provide a powerful trigger to reflect, explore and gain awareness on the urgency of working towards the achievement of most of the other 17 development goals, for instance SDG1 (no poverty), SDG 2 (zero hunger) and SDG 13 (climate action).

For refugee-engaging digital literacy and arts-based work to increase equality, diversity and inclusion, a more situated and intersectional approach to participation is required and the potential for projects to unintentionally reproduce colonial power relations must be addressed as a first principle, to avoid, or at least mitigate against ‘the unrecognised contradiction within a position that valorises the concrete experience of the oppressed, while being so uncritical about the historical role of the intellectual’ (Spivak Citation1988, 69).

Therefore, the power dynamics inherent to inter-cultural partnerships must be scrutinised, especially where Global South ‘agency’ is framed by ‘neoliberal capacity building’. The textual process is a site of tension, as arts-based methods in ‘third spaces’ do not ‘always already’ avoid the reproduction of ‘colonialist extractionist modes of research’ and raise the issue of working within the structures of both digital capitalism and neoliberal development models, ‘using troublesome tools for constructivist ends.’ (McLean Citation2021, 14).

Indeed, as the photographer Del Grace Volcano recently expressed, it is not about ‘taking’ photos but rather working collaboratively to establish project work (see Hogan Citation2022), whilst enabling a renegotiation of refugee youth’s ‘Textual (Re)presentation’ and to address the ‘(Re)production of vulnerability’ maintained by the ‘theoretical inadequacy and academic vacuum in understanding the critical conditionalities’ of refugee experience through ethnographic principles (Uddin Citation2021). This also speaks to the inherent tensions in ideas about ‘giving voice’ or even our ethical listening to seldom heard voices, as the project framed the intentions, as these present complex consequences of visibility (Rega and Medrado Citation2021) in threshold moments of exposure or ‘raising awareness’, when considered from a Global South perspective. The Global South perspective is a phrasing we apply here in the broader sense of the ‘geography of oppression’ or an ‘epistemology of the South’, knowledge born in struggle with resists epistemic monocultures and the intersecting modes of domination – capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy (de Sousa Santos Citation2015, 4 and Citation2022) – rather than the precise location, acknowledging the problematic ethics of Global North researchers ‘locating’ refugees and research partners in fieldwork settings in this way.

To further instil this sensitivity, DA-RE was informed by ethical guidance for researching digital migration from the previous work of Sara Marino, whose insights enabled DA-RE to contribute to knowledge about aiming to involve participants in different stages of the research process. In tandem with this, our recent research into media literacy work in third spaces has developed in us a way of thinking about literacy of all kinds as dynamic rather than static and generated a set of transferable design thinking and working principles for this kind of developmental research activity (Rega and McDougall Citation2021). Informing DA-RE, these included negotiating nuanced local contexts; working with values for capacity and resilience and looking out for both inter- cultural nuance and textual moments that require close listening and reflexivity with regard to hierarchies of attention. Our intention was, then, to intersect this conception of dynamic literacies (Potter and McDougall Citation2017) with ‘a dynamic conception of voice in which listening is clearly foregrounded.’ (Dreher Citation2012, 157).

Results

The virtual exhibition of the work produced in the two settings and a recording of the panel are online at https://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/research/projects/da-re-digital-arts-refugee-engagement.

Our participants gave consent for their work to be shared online and to be named and our ethical responsibility extends to crediting them here, in addition to this article being an output of equal collaboration between all partners. Our creative, digital artivists, were Ayala Begum; Mohammad Jonayek; Md Iddris: Rio Yassin Abdumonab; Loai Dalati; Shahida; Mohammed Zunaid; Md. Raihan; Anisul Mustafa; Mohammad Sahat Zia; Mohammad Arfat; Mohammad Royal Shafi; Mohammad Asom; Fadia Alnasser; Michael Hart; Ahmed Hassun; Youssef Haji and Ahmed Durbula. Their work can be viewed in the virtual exhibition curated on the project website (CEMP / DA-RE Citation2022). Indeed, it MUST be viewed, for this article to carry any purpose or meaning, or for the project itself to achieve any impact ().

The ‘third spaces’ enabled by DA-RE were multi-directional. The reciprocal exchanges between the refugee youth in the two settings were in real time, through Zoom, and did enable funds of knowledge and digital literacies to move across and between borders, but the richer exchange space was that between the digital literacies which the participants brought with them to DA-RE and the artistic activities in which they differently motivated. Participants referred to themselves and one another as refugees but primarily presented themselves as artists, musicians, film-makers, animators, writers, poets and motivational speakers*. So, whilst the themes of their media work related to identity negotiation, digital storytelling, counter-representing lived experience as refugee youth, this was at most equal in importance and in many cases less important than the sharing of their work as creatives.

The over-arching theory of change and the way we sought to articulate value as impact, albeit curtailed by the funding cut we faced (elaborated further in the section on limitations), sees the fusion of literacy, digital media and arts as dynamic and environmental, drawing on re-appraisals of Freire’s contribution to epistemology and social change in the digital age (Suzina and Tufte Citation2022). Fry (Citation2022) offers a similar ecosystem conception, seeing this work as an intersect of context, content, power and paradigm, always differently inter-related in geo-cultural context and broadly ‘Freireian’ in the impulse to ‘understand the whole environment of possibility’ (Fry Citation2022, 157). In a more direct (re) articulation of value in this Freirian language, Magallenes-Blanco (Citation2022) writes from the perspective of collaborative indigenous epistemology work in Mexico, but offering much for our project and the broader field of intentionality:

We work on communication practice, products and strategies to decolonise ourselves from the dominant culture, from the ideas that others have built up about us, that have divided us and made us invisible … .we must create and create and create without limits and without formats Irreverently free! (Citation2022, 27)

In conducting thematic analysis of the textual ‘data’ (in the form of digital arts), we seek to locate the connecting points of the digital literacies our participants brought to DA-RE and the digital arts contexts the project’s third space provided and to identify moments of conversion, in these connecting points, of literacy into capability and to think about these as liminal spaces, visibility thresholds (Rega and Medrado Citation2021) with consequences. Neag and Sefton-Green observe how ‘Forging a new life means not only finding a place to stay but, today, also making a presence visible across the migrant’s different platforms.’ (Citation2021, 17), whilst Marino (Citation2021) observes the complex tension between the technological processing of refugee and migrant identities into ‘data subjects’ and technology for social good, a more productive narrative of technologies for social good: ‘an alternative, techno- mediated framework where the possibility of a counter-hegemonic project around a new idea for social justice for refugees can potentially be imagined.’ (Citation2021, 8). DA-RE was informed by this (more) productive notion of ‘techno-mediation’ in the desire to create, in the third space, the potential for the use of existing digital literacies converging with artistic resources of hope. The approach this project tried to take to contribute to social good in this way was to enable a space for ethical listening to the stories that were shared by our participants in this convergence of their literacy repertoires and the possibilities DA-RE presented, to connect and to tell.

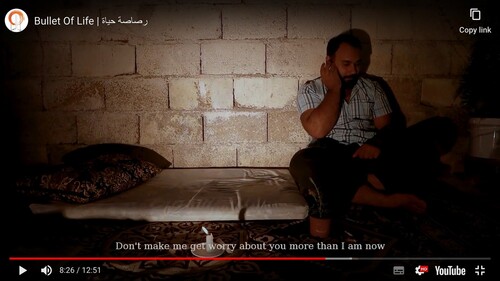

Eighteen digital art texts / portfolios were produced for DA-RE. The project generated three uploaded paintings; four collections of poetry with photographs; five films; two educational / informative videos for YouTube; one music video; one collection of videography and two photojournalism pieces. The work can be categorised into four ‘meta-representational’ critical positionings, providing different, but thematically connected, motivations for the attention our participants wish for and from their audiences.

Firstly, counter-representational storying of life in the camps included accounts of non-formal education, inter-generational digital networking and participative development, including advocacy for cultural preservation (for example, the historical duty for Rohingya youth to preserve this) but also educational and informative material itself, in the form of language development video for YouTube and documentary material on the metaverse and digital reading. Education was consistently a site of hope (‘Education is future’) and aspiration, but also of collective responsibility (for ‘learning together’ and ‘working together in danger’) from within and between the participant groups, as opposed to being something to access externally or in host communities.

Second, narratives of crisis and trauma were aesthetically rich as well as deeply reflective, including artistic portrayals of fire and flood in the camps; documentary footage of war and displacement; the dramatisation of the loss of family and photographs and poems requiring no ‘intellectual’ analysis: ‘I hate this name, refugee’; ‘Why am I alive?’; ‘No more refugee life’; ‘Insomnia’; ‘Memories left in Rakhine’ ‘Attempting to forget the atrocious past.’

The third theme, gender equality, was the focus across all media, including ‘artivist’ work such as ‘Her Freedom’ and ‘Daughter the Great’, these offering deep critical work about culture and community both prior to and during migration, along with nuanced reflections, such as ‘Trying to be Beautiful’, in the current setting. However, we also observed how different examples of performativity intersect with variations in gender and that women's voices need to be accounted for at a much larger scale than was possible within this exploratory study ().

The fourth element was a fusion of aspects of the other three, converging in hopeful, but complex digital arts, ‘Thinking of a Blurred Future’ and a portrayal of suffering through gestures and symbol, but concluding by reaching for a goal.

In accounting for the situated meaning of the work generated, in interviews and the live panel, our refugee youth research assistants described both refugee camps and social media platforms as, again, a kind of hybrid third space. They described hospitality and kindness when conducting the field work and being referred to other people to gather more stories, beyond the participant groups. These are not only reflections on the experience of conducting the project, but important paratextual ‘data’ requiring our attention, as the researchers described the collection and collation of ‘stories of joy, sorrows, inspirations and lots of deprivations’. The motivations described, on behalf of the participants, but by their peer research assistants, for the work produced, were focussed almost always on being heard across the world, for example, ‘voices are bound by state and margin, art becomes the voice to the world,’ but also the duality of using digital arts as both a reflective document of life and also ‘a medium for speaking to own community, host community and the world’. Our interpretation above was also partially ‘triangulated’ through the thematic categorisation of the work from within the participant communities – art as a source of joy in suffering; the importance of education; keeping alive the soul in deprivation; curating memories of the past and alternatively documenting the present life ().

During the panel discussion at our virtual event, participants prioritised visibility and reaching audiences for their artistic work over reflections on lived experience or how they ‘felt’ during this project and these moments were richly indicative of the problems and tensions we acknowledged earlier. However, we did witness, across our panel and the wider audience, more ‘productive understandings of mobility’ through the contextual discussion about the work which had been shared, as aesthetic practice was articulated as activism, accounting for, as Nasir Uddin described, the act of digitally storytelling the ‘atrocious past, critical present and uncertain future’. The ways in which the combination of refugee youths’ digital literacies with digital arts contexts enabled reflexivity on sensitive topics and traumatic experience were understood as conflicted in terms of the tension between the desire to participate and self-represent, with the well-rehearsed efficacy benefits, and the challenges of finding time and managing complex processes of ‘integration’ alongside this kind of identity work. The panel reflected on the relationship between digital arts, inner reflexivity and external / collective change (in our rubric, capability with good consequences).

Findings and discussion

The findings from this project bring forth provisional new knowledge about voice and agency. Using our theory of change for the ‘uses of digital literacy’, as opposed to viewing literacy as either a neutral and innately positive competence or a deficit, we seek to connect DA-RE’s findings to more general questions around how voice and agency intersect with the ‘problem space’ of citizenship, and how ‘represented’ our participants feel.

As stated, the intention to convert existing digital literacies into capability through art-based activities to facilitate positive consequences in terms of social justice and social good was at the foreground of the project, and in terms of the theory of change, the project leveraged high levels of access, developed more reflexive awareness and moved towards the more agentive levels of capability and consequences. The conversion of digital literacy into capability was evident for both of the second space organisations we worked with (Gate of Sun and the University of Chittagong), as they developed new ways of working to further their objectives. In DA-RE, we could also see this capability conversion taking place across the digital literacy third spaces, the inter-cultural exchanges and film production and in the exhibition of digital arts and the attendant opportunities to potentially grow as creative artivists. The artistic activities were used to channel experiences into messages, the digital literacy skills were utilised in the process and developed further by the partners, but there was, as expected, no sense in which digital literacy in and of itself constituted the capability needed for these forms of reflection and expression. Instead, in this relation, the application of such literacies into artistic acts, or modes of artivism, was the significant threshold. It is important to highlight that participants referred to themselves and one another as refugees but primarily presented themselves as artists, musicians, film- makers, animators, writers, poets and motivational speakers. So, whilst the themes of their work related to identity negotiation, digital storytelling, counter-representing lived experience as refugee youth, this was at most equal in importance and in many cases less important than the sharing of their work as creatives. Participants expressed a variety of motivations to produce their work, from the importance of articulating their lived experience in the camps and in the host community (this was different across the two settings, since most of the Syrian refugees have been living out of camps which have subsequently been closed) to broader social justice objectives such as gender equality or early marriage, to the need to expose injustice and criminal activity but also messages of hope and resilience for one another and to others in similar situations – ‘nothing is impossible’; ‘everybody wins by their own means’.

Moving to consequences, in DA-RE the use of existing digital literacies combined with artistic practices was intentionally, from the outset, driven by the desire to contribute to social good and social justice. At the level of observable positive change, therefore, it must be acknowledged we would expect to move towards this element of the theory of change, it was driven that way by everyone involved, rather than emerging as an organic consequence. However, the configuration of the partnerships meant that these consequences were differently motivated to other projects, as this is always a unique arrangement, whether by design or otherwise. The DA-RE participants are at an early stages of ecosystem change, but our findings show the trajectory to this, as we could see most clearly how the third space partnership itself, in terms of the ethical listening it required by partners and the audience reached with the digital arts, created good consequences from digital literacy work. In this case, consequences could be observed more clearly within the third space, as opposed to the third space being a catalyst for impacts in the first spaces of participants or consistent with new directions of travel for second spaces.

Limitations

DA-RE was initially funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council through the Global Challenges Research Fund. Between the award and the start date the UK Government’s cut to the overseas development budget led to the withdrawal of funding for this project, among many commissioned. The project was ‘salvaged’ through university QR, so that we could honour our commitments to the teams in the two refugee youth settings, with the academic time from the UK given to the project ‘for free’. Therefore, the project’s outcomes were limited to the two virtual exhibitions and linked virtual panel, and the analysis of the artistic work and transcribed panel discussions and interviews with participants. The initial intention, with the much more substantial funding, had been to conduct more extensive fieldwork in the settings as a research team, support travel by the refugee youth participants to the academics and to include longitudinal follow up to see evidence of ecosystem health improvements and capability outcomes for the refugee youth (this had been funded as a three year project). The reduction of scope to exploring short-term potential for positive change was also imposed by the way we had to work remotely, due to covid (the funded project was designed in 2019), not only as researchers engaging with participants through screens, but also in the ways that the partnership itself was reliant on virtual third space by necessity rather than design.

The other limitation we want to acknowledge is the role of the researchers’ positionality and its impact on the research design process, evaluation and outcomes. Early discussions on how we, as academics, could mitigate the influence (and inherent shortcomings) of our own ontological and epistemological categories on the participants’ voice and agency led to a series of considerations that guided our work with refugees. Using Sara Marino’s notion of ‘fragmented methodology’ (Citation2021) as a starting point, we visualised the research design process as receptive of the tensions naturally occurring within migration and especially refugee research between researchers and participants. In this context, working with a diverse team of academics, practitioners and refugee youths across borders encouraged us to prioritise trust building through continuous interactions and recognition of our participants as active subjects and as co-participants in the research process. While we recognise that the establishment of trust has ‘deep-seated cultural and personal roots’ that demand ‘flexible and open approaches instead of a one-for-all homogenising methodology’ (Marino Citation2021, 77) the involvement of our participants at different stages of the research design process, including the organisation of the virtual exhibition and the review of this publication allowed us to mitigate the risks of imposing our presence as the ‘colonial observers’. The active role that our participants had in leading the conversation around the transformative impact of digital arts and literacies on their lives, often in dialogue with trusted practitioners, encouraged the researchers to take a step back and adopt a listening role.

The other consideration worth mentioning is the long-term impact of our study, especially on the community of refugee youth we worked with. This aspect is of crucial importance as refugee research often has a short temporality once the results of any given projects are published. Marino (Citation2021) has previously observed that in order to counter-act the tension between the transformation of refugee and migrant identities into ‘data subjects’ that can easily be forgotten once the research appetite has been satisfied and the renewed interest in how the digital can bring social change, we need ‘an alternative, techno-mediated framework where the possibility of a counter-hegemonic project around a new idea for social justice for refugees can potentially be imagined.’ (Citation2021, 8). DA-RE was informed by this (more) productive notion of ‘techno-mediation’ in the desire to create, in the third space, the potential for the use of existing digital literacies converging with artistic resources of hope. The approach this project tried to pursue is tied to a conceptualisation of social change and social good as ‘spaces of intervention where communities subject to […] datafication can also be recognized as coparticipants and as the only voices that can speak for the trauma and deep emotional struggles experienced by refugees’ (Citation2021, 5546). In this respect, DA-RE contributes to the circulation of social good practices and discourses by creating a space for ethical and meaningful listening to the stories that were shared by our participants. We believe that ‘by harnessing the power of digital innovation as a collaborative […] resource, a more human-centered […] use of technologies can effectively encourage the strengthening of principles of social justice, sustainability, and inclusivity’ (Citation2021, 5548) and serve as a starting point for a longer-term conversation DA-RE is planning to initiate with our participants.

Conclusion

The way in which the project tried to contribute to social good was to enable a space for ethical listening to the stories that were shared by our participants in this convergence of their literacy repertoires and the possibilities DA-RE presented, to connect and to tell those stories to fellow artists experiencing a refugee life and to an international audience. This was very much in line with the motivations described, on behalf of the participants, by the peer research assistants involved in the project, for the work produced, focussed almost always on being heard across the world, for example, ‘voices are bound by state and margin, art becomes the voice to the world.’ Their artistic outputs, digitally circulated, have the potential to ‘change the story’ to generate self-efficacy and engage virtual and media audiences in an alternative discourse than one of refugees, migrants and asylum seekers as passive and silenced, or dangerous and ‘other’, as was also reflected in the virtual panel held at the end of the project. Nevertheless, the sustainable longitudinal impact (consequences) of such an endeavour depends on the responsibility of both host communities and diverse audiences for such research, in the West / Global North especially, to differently engage in these spaces where digital literacy can enable ‘seldom heard voices’ to be articulated. The message was very clear from this project as a whole and explicitly articulated by participants in our virtual panel – an exploratory project such as DA-RE can do more social good through the exposure of the digital arts and the connection to diverse audiences than were we ‘just’ to research the participants’ experiences and situations. But the question we cannot evade is this – what and how do our participants benefit, in any sustainable, longitudinal sense, in order to give justice to their contributions, to develop capabilities with good consequences on their terms, rather than, or in addition to ours? Of course, we are attentive to and utilise our privilege with the intention to assess what Dreher calls ‘the other side of voice’ (Citation2012, 159), and we will use these exploratory findings to apply for the funding to scale up, to mobilise our participants, to build capacity beyond efficacy into training, employment and problem resolution. But there can be no evasion of the paradox of declaring such intentions in an academic article, albeit ‘under erasure’ of, as Spivak saw it, ‘the general violence that is the possibility of an episteme’ (Citation1988, 83), speaking in this way and in this delimited space on behalf of the ‘seldom heard’, if this ‘impact’ can only be realised through benevolent listening on our part.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Einar Thorsen and Dinusha Mendes for their support in securing alternative funds to protect the in-country activities to which our partners had committed. Most importantly, this project was entirely the result of the work, often in adversity, as is captured in the virtual panel recording on the project site, by our refugee youth participants Ayala Begum; Mohammad Jonayek; Md Iddris: Rio Yassin Abdumonab; Loai Dalati; Shahida; Mohammed Zunaid; Md. Raihan; Anisul Mustafa; Mohammad Sahat Zia; Mohammad Arfat; Mohammad Royal Shafi; Mohammad Asom; Fadia Alnasser; Michael Hart; Ahmed Hassun; Youssef Haji and Ahmed Durbula. We are also indebted to Mohammad Zarzou for technical support and creative mentoring and Kiyono Hayami, Eda Çakaloz, Sinem Ünüvar, Ada Yasemin Kardaş for peer support to participants, working with Özden Bademci, and for translation during the virtual panel. In Bangladesh, Nasir Uddin was supported by three research assistants, funded by the project – Tonmoy Chowdhury, Nusrat Kabir Preom and Lisa After Yesmin. From Gate of Sun, support for the project was provided by the following team members: Muhammad Zarzour led the creative team and develop artistic ideas for participants; Razan Ajlouni Local provided translation and meeting reports. Amr Ajlouni is a filmmaker who was responsible for developing ideas and supporting production stages, writing final reports and co-authoring this article; Hussein Mohammed was responsible for team communications and supported participants in administration, zoom meetings and helping with translation in addition to helping all participants in digital work through the Gate of Sun platform and others; Mohanad Haj Mohammed was project lawyer, produced DA-RE expenditure reports, assisted in translation during online sessions and Yamen Hasan supported filming and editing of all projects in collaboration with the participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amr Aljouni

Amr Aljouni is a filmmaker from Damascus, Syria. In 2017, he established Gate of Sun Production House. Since then, he has been widening his experience in entrepreneurship and start-up with experts from Inno Campus, Habitat Turkey, and Impact Hub Istanbul.

Ozden Bademci

Dr. Ozden Bademci holds an associate professorship in clinical psychology and is the Founder Director for Research and Application Centre for Street Children (SOYAÇ) at Maltepe University.

Susan Hogan

Susan Hogan is Professor of Arts and Health at the University of Derby and conducts interdisciplinary research around women's issues and the arts in health, cultural history, and visual sociology.

Sara Marino

Dr. Sara Marino is Senior Lecturer in Communications and Media at London College of Communication, University of the Arts. Her research focuses on the intersections between migration, material cultures and media technologies. Her latest book “Mediating the refugee crisis. Digital Solidarity, Humanitarian Technologies and Border Regimes” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021) uniquely examined how communication technologies have become central to governance, resistance, humanitarianism and activism.

Julian McDougall

Professor Julian McDougall is Professor in Media and Education, Head of the Centre for Excellence in Media Practice and Principal Fellow of Advance HE. He runs the Professional Doctorate (Ed D) in Creative and Media Education at Bournemouth University and convenes the annual International Media Education Summit.

Isabella Rega

Dr. Isabella Rega is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University (UK). Her research focuses on the role of digital media to promote community development and social change. She is the co-author of Media Activism, Artivism and the Fight Against Marginalisation in the Global South South-to-South Communication (Routledge, 2023).

Sarah Skyrme

Sarah Skyrme is a Research Assistant at Manchester University. Her research interests include health, wellbeing, social care policy, disability, and creative methods.

Nasir Uddin

Dr. Nasir Uddin is a cultural anthropologist and Professor of Anthropology at the University of Chittagong. Uddin's theory ‘Subhuman' life is widely cited in the scholarship on refugee, migration, stateless people, asylum seeker, camp people, forcibly displaced people, and illegal migrants. His latest book is “The Rohingya: An Ethnography of ‘Subhuman’ Life” (The Oxford University Press, 2020).

References

- Bademci, O. H., and F. E. Karadayi. 2013. “Working with Street Boys: Importance of Creating a Socially Safe Environment through Social Partnership, and Collaboration through Peer-based Interaction.” Child Care in Practice 19: 162–180. doi:10.1080/13575279.2012.759538.

- Bhabha, H. 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

- Boulil, D., and R. Hanney. 2022. “Change must Come: Mixing Methods, Evidencing Effects, Measuring Impact.” Media Practice and Education 23 (2): 126–137. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/25741136.2022.2056790?journalCode=rjmp21.

- CEMP / DA-RE. 2022. Digital Arts | Refugee Engagement: https://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/research/projects/da-re-digital-arts-refugee-engagement.

- Corbett, C. N., and D. P. Moxley. 2018. “Using the Visual Arts to Form an Intervention Design Concept for Resettlement Support among Refugee Women.” Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services 99 (2): 146–159. doi:10.1177/1044389418767840

- Couldry, N. 2010. Why Voice Matters: Culture and Politics After Neoliberalism. London: Sage.

- de Sousa Santos, B. 2015. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. London: Routledge.

- de Sousa Santos, B. 2022. Paulo Freire Lecture, 21.9.22. London: Loughborough University.

- Dreher, T. 2012. “A Partial Promise of Voice: Digital Storytelling and the Limits of Listening.” Media International Australia 142: 157–166. doi:10.1177/1329878X1214200117

- Fry, K. 2022. “Media Environments: A Dynamic Model of Media Literacy, Activism and Social Change.” In Media Literacy, Equity and Social Justice, edited by B. De Abreu, 149–158. New York: Routledge.

- Georgiou, M. 2018. “Does the Subaltern Speak? Migrant Voices in Digital Europe.” Popular Communication 16 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1080/15405702.2017.1412440

- Hogan, S. 2022. Photography: Arts for Health. Bingley: Emerald Press.

- Holle, F., M. C. Rast, and H. Ghorashi. 2021. “Exilic (Art) Narratives of Queer Refugees Challenging Dominant Hegemonies.” Frontiers in Sociology 6, doi:10.3389/fsoc.2021.641630.

- Horsti, K. 2019. “Refugee Testimonies Enacted: Voice and Solidarity in Media Art Installations.” Popular Communication 17 (2): 125–139. doi:10.1080/15405702.2018.1535656

- Magallenes-Blanco, C. 2022. “A Dialogue on Communication from an Indigenous Perspective in Mexico.” In Freire and the Perseverance of Hope: Exploring Communication and Social Change. Theory on Demand (43), edited by C. Suzina, and T. Tufte, 23–27. London: Institute of Network Cultures.

- Manyozo, L. 2013. Media, Communication and Development: Three Approaches. London: Sage.

- Marino, S. 2021. Mediating the Refugee Crisis: Digital Solidarity, Humanitarian Technologies and Border Regimes. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- McDougall, J., and I. Rega. 2022. “Beyond Solutionism: Differently Motivating Media Literacy.” Media and Communication 10 (4). doi:10.17645/mac.v10i4.5715.

- McLean, J. 2021. “Gives a Physical Sense Almost: Using Immersive Media to Build Decolonial Moments in Higher Education for Radical Citizenship.” Digital Culture and Education 13 (1): 1–19. https://www.digitalcultureandeducation.com/volume-13-papers/mclean-2021.

- Medrado, A., and I. Rega. 2023. Media Activism, Artivism and the Fight Against Marginalisation in the Global South: South-to-South Communication. London: Routledge.

- Neag, A., and J. Sefton-Green. 2021. “Embodied Technology Use: Unaccompanied Refugee Youth and the Migrant Platformed Body.” MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research 71: 9–30. doi:10.7146/mediekultur.v37i71.125346

- Neag, A., and M. Supa. 2020. “Emotional Practices of Unaccompanied Refugee Youth on Social Media.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (5): 766–786. doi:10.1177/1367877920929710

- O’Neill, M., and P. Hubbard. 2012. “Asylum, Exclusion and the Social Role of Arts and Culture.” Moving Worlds: a journal of transcultural writing, Asylum Accounts 12: 2. doi:10.1080/14725861003606878

- Potter, J., and J. McDougall. 2017. Digital Media, Culture and Education: Theorising third space literacies. London: Palgrave Macmillan/Spinger.

- Rega, I., and J. McDougall. 2021. Dual Netizenship: Transferable Principles. Bournemouth University / British Council. https://dualnetizenshiptransferableprinciples.wordpress.com/.

- Rega, I., and A. Medrado. 2021. “The Stepping into Visibility Model: Reflecting on Consequences of Social Media Visibility – a Global South Perspective.” Information, Communication & Society, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1954228.

- Safak-Ayvazoglu, A., and F. Kunuroglu. 2021. “Acculturation Experiences and Psychological Well-being of Syrian Refugees Attending Universities in Turkey: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 14 (1): 96–109. doi:10.1037/dhe0000148

- Sen, A. K. 2008. “Capability and Well-Being.” In The Philosophy of Economics, 3rd ed., edited by D. M. Hausman, 270–293. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Spivak, G. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson, and Lawrence Grossberg, 271. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Suzina, A., and T. Tufte (eds). 2022. Freire and the Perseverance of Hope. Theory on Demand #43. London: Loughborough University, Institute of Network Cultures.

- Uddin, N. 2021. The Rohingya: An Ethnography of 'Subhuman' Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.