ABSTRACT

In spite of a range of fundamental issues, biometric surveillance has become an integral part of everyday life. Artists are creating a range of creative responses to the emergence of biometric control that critically interrogate and denormalise it. Most of the existing research in this topic however ignores the exhibitionary context in which surveillance art is usually experienced. This article shifts the analytical perspective to the site of the exhibition in order to attend to the specificity of the artworks’ critical potential – that is influenced by their spatial and narrative context, as well as their juxtaposition with each other. Specifically, it analyses the exhibition Face Value: Surveillance and Identity in the Age of Digital Facial Recognition (2021) as an exemplary case study to discuss how exhibitions can construct a multi-faceted framework through which visitors can get a grip of the ‘society of control’. Drawing on Pisters and Deleuze, this article argues that exhibitions can engender a constellation of ‘circuit breakers’ in which the biometric control of faces is disrupted through a configuration of artistic strategies. In Face Value, these strategies include exposing the black-boxed structures of facial recognition software, showing the human stories behind data and imagining alternative technologies.

[W]e are told by governments, scientists, and security experts that our faces are perfectly readable on the surface, that core truths about us can be extracted by calculations at the surface level of our bodies. This occurs constantly; our pictures are taken by cameras in urban spaces or at national border checkpoints. Over time, how can this not affect how we look at other faces on a daily basis? (Blas and Gaboury Citation2016, 159)

Figure 1. Installation shot Face Value at IMPAKT [Center for Media Culture]. © Pieter Kers | Beeld.nu.

![Figure 1. Installation shot Face Value at IMPAKT [Center for Media Culture]. © Pieter Kers | Beeld.nu.](/cms/asset/2a8db24c-0632-4aee-9ca1-5fc2f93254f9/rjmp_a_2210425_f0001_oc.jpg)

The field of media art presents an important site of critique in which the ubiquity and normalisation of surveillance is challenged. Deploying strategies such as hacking, sousveillance (Mann, Nolan, and Wellman Citation2003) or anti-surveillance camouflage, artists have critically investigated – and drawn attention to – the profiling, categorising, discriminating and controlling dimensions of surveillance. While the disruptive potential of surveillance art has been frequently discussed in academic scholarship, the exhibitionary context in which such works of art are commonly presented and experienced tends to be overlooked (see for example Monahan Citation2022; Stark and Crawford Citation2019).

That context is crucially important as exhibitions are not neutral spaces that showcase art; rather, they are ideological texts and their meanings extend the mere sum of the individual artworks of which they are constituted (O’Neill Citation2007; Lidchi Citation1997; Moser Citation2010). The narrative framing and spatial ordering within which works of art are presented, as well as their position in relation to other works, impacts how they are experienced. Therefore, this article shifts the analytical perspective from individual artworks to the site of the exhibition, to investigate how the juxtaposition of different works of art in an exhibitionary context denormalises the surveillance of faces. Specifically, I focus on the art exhibition Face Value: Surveillance and Identity in the Age of Digital Face Recognition () that I curated for IMPAKT [Centre for Media Culture] in Utrecht, in collaboration with the Netherlands Film Festival.Footnote2 When curating Face Value I approached the exhibition as a ‘research exhibition’, which curator and scholar Simon Sheikh defines as ‘as a site for ongoing research about the formats and thematic concerns of the exhibition’ (Sheikh Citation2013, 40). Through five new media artworks, Face Value investigated the changing meaning of the human face in a society of controlFootnote3 (Deleuze Citation1992) where our faces are continually captured and screened through biometric surveillance.

In this article, I reflect on my curatorial practice and investigate Face Value by deploying the notion of art as a ‘circuit breaker’ as an analytical lens. Specifically, I to investigate how the exhibition disrupts normalised circuits of surveillance control. My analysis draws on the work of media scholar Patricia Pisters (Citation2013), who has applied Gilles Deleuze’s work (Deleuze Citation1995) on circuit breakers in the specific context of surveillance art. Pisters (Citation2013) argues that art can interfere in discussions of surveillance by developing different affective entry points, new ways of relating to and making sense of surveillance, that problematise dominant representations of surveillance as a top-down stream of control that cannot be resisted. By interrupting normalised surveillance circuits – for example through tactics of camouflage, or by questioning some of the key assumptions from which surveillance technologies operate – surveillance artworks can engender feelings of discomfort, confusion, or surprise that spark processes of critical reflection. This article extends this line of argumentation by attending to the circuit breaking potential of exhibitions, which I discuss as sites where visitors are confronted with a constellation of circuit breakers. By bringing together a variety of artistic forms, perspectives and strategies, exhibitions can amplify the denormalising potential of individual artworks and so function as a pressure cooker for critical reflection.

In the following, I first introduce the scholarly debates that Face Value intervenes in and show how biometric surveillance, despite a range of political, social, and cultural concerns, has become a relatively normalised part of everyday life. I continue by stressing the importance of art as a site of critique in which surveillance control is defamiliarised (Stark and Crawford Citation2019) by making audiences experience taken-for-granted circuits of surveillance as strange. Then I zoom in on the case of Face Value, of which I conduct a narrative analysis – attending to the story that visitors ‘take in and take home’ when walking through an exhibition space (Bal Citation1996, 561). This is followed by an investigation of the exhibition’s circuit-breaking potential, which I discuss in relation to three selected artworks that activate different types of interventions to create friction in normalised surveillance circuits.

Normalised surveillance of faces

Installed for risk prediction and protection, biometric technologies are part of an ongoing securitisation of society (Buzan and Wæver Citation2003). While these technologies were initially used in war contexts and for crime prevention purposes, their use has expanded to public protests, examination and attendance screening in education, and even to safeguard control over humanitarian aid in refugee camps. Moreover, surveillance is also used by companies to commodify personal data and predict, influence and modify behaviour for commercial purposes – a process that Shoshanna Zuboff has defined as ‘surveillance capitalism’ (Citation2019). The commercial and governmental use of biometrics has received critique from digital and human rights organisations, journalists, activists, and researchers (amongst others). They have pointed out how biometric surveillance not only poses a threat to privacy but also infringes fundamental human rights including the right to free speech, the right to protest and the right to non-discrimination.Footnote4

Biometric technologies ‘codify discrimination and compound existing inequalities’ (Madianou Citation2019, 596). Biometric recognition is not a neutral process but a normative one, as it works from the assumption that subjects are unitary, autonomous, static and fully knowable – and that the body is an ‘indisputable anchor to which data can be safely secured’ (Amoore Citation2006, 342). More concretely, biometrics scan bodies and classify them into categories of identity, including race, gender and age, that are defined in a binary way and negate ways of being in the world that do not fit one single category or refuse those categories in their self-identification (Browne Citation2015; Magnet Citation2011; Quinan and Hunt, Citation2022). As a result, biometric technologies disproportionately misrecognise subjects that do not comply with the white, cis-gender, male, able norm (Browne Citation2015; Magnet Citation2011). In addition to discrimination through misrecognition, biometric technologies have been, and continue to be applied to the profiling, targeting, and policing of marginalised groups (Browne Citation2015; Jones, Kilpatrick, and Maccanico Citation2022; M’charek, Schramm, and Skinner Citation2014). So, much unlike biometrics’ aura of objectivity, the use of biometric technologies to track, measure and identify people is political and works in discriminatory ways (Browne Citation2015; Magnet Citation2011; Pugliese Citation2005; Wevers Citation2018).

In addition to these urgent political issues, biometric surveillance raises a number of sociocultural concerns about faces, identities and their relations. As artist and queer scholar Zach Blas has argued, ‘[u]nderstanding the face as a biometric code is highly dangerous because it transforms the face into something that can be controlled and regulated, and it grossly reduces the complexities of the face’ (Blas and Gaboury Citation2016, 160). Following Blas, biometric recognition can be understood as a process of ‘informatic capture’ in which somatic complexities are reduced to binary biometric code – and identity is diluted to a set of algorithmically readable traces (Zilio Citation2020, 108, 109). Rather than passive visual registration, informatic capture draws attention to the active seizure of the body as code, which is not a neutral process but one embedded in structures of control (Blas and Gaboury Citation2016).

Despite these urgent political issues, the pervasiveness of surveillance in Europe is increasingly normalised, meaning that it tends to be perceived as an ‘unremarkable, mundane, normal’ part of everyday life (Wood and Webster Citation2009, 263). As social scientist Darren Ellis (Citation2020) argues, this can partly be explained from the covert nature of most surveillance systems (26). Moreover, the ‘complexity of the systems is likely to diminish the ability to meaningfully comprehend them in day to day activities’ (Ellis Citation2020, 16), which leads to a lack of awareness of the implications of these systems.

As Selinger and Rhee (Citation2021) have discussed, the normalisation of surveillance emerges from a set of different sociological and psychological processes that include getting used to surveillance because surveillance measurements that were initially introduced as temporary become permanent; a lack of consideration on surveillance-related risks and issues because that information is not rendered transparent to nonexperts, and the feeling that surveillance is acceptable and even desirable because it is already ubiquitous and thus appears normal.

Various scholars have argued that this normalisation of surveillance in social life tends to lead to the adoption of individual attitudes of indifference, to ‘not caring’, and the idea that no alternatives to the surveillance society can be imagined (Ellis Citation2020; Wood and Webster Citation2009). Recent work by Ellis (Citation2020) brings nuances to this argument by understanding such attitudes as a form of ‘surveillance-apatheia’ rather than surveillance-apathy:

Surveillance-apatheia then is an attitude that individuals learn, which decreases the agitation and anxiety produced by surveillance systems and their associated practices. This attitude stems from the perception that there is little one can do to avoid them, so why concern oneself with deliberation and anxiety of them. (Ellis Citation2020, 19)

Scholars and activists have expressed concerns about the ways in which attitudes of apathy and apatheia withhold subjects from raising fundamental questions about the legitimacy, validity, and appropriateness of surveillance by governmental organisations and commercial entities. As Wood and Webster assert, this normalisation calls for a need to move towards a more critical approach and make surveillance ‘strange and questionable again’(Wood and Webster Citation2009, 270).

Denormalising surveillance through art

Already since the 1980s, artists have been developing creative responses to surveillance that raise important questions about agency and power asymmetries (Krause Citation2018, 139) – and so diminish surveillance apathy and apatheia. This body of artistic work gradually converged ‘into a field of shared artistic interest’ (Krause Citation2018, 139) that has become known as ‘artveillance’ (Brighenti Citation2010) or ‘critical surveillance art’ (Monahan Citation2022). As Feminist Surveillance Scholar Torin Monahan argues, critical surveillance art is not dedicated to creating solutions, but rather ‘seeks to agitate, to fashion situations that expose visibility regimes and challenge audiences to reflect on their places within them’ (Citation2022, 11). As the industry continues to develop new technologies of surveillance, so do artists persist to engage with them, which has resulted in artistic explorations of technologies including CCTV cameras, drones, biometric software, social media platforms and predictive policing systems.

According to philosopher Gilles Deleuze, critical art projects can function as ‘circuit breakers’ in a society of control (Citation1995). Drawing on Deleuze, Pisters deploys the notion of art as a ‘circuit breaker’ to discuss how ‘[a]rtistic interventions can be considered as particularly scaled dimensions of relationalities that address our surveillance brain-screens on an affective level and change our perspectives on power and control’ (Citation2013, 203). In other words, by interfering in specific affects and relationalities vis-à-vis surveillance, artworks function as ‘circuit breakers’ that evoke small disruptions in control systems and structures, for example by temporarily destabilising the hierarchical relationship between watcher and watched. Circuit breakers decelerate power, and this process of slowing down – which can be mobilised through defamiliarisation – attunes our senses to pay attention rather than remain indifferent. As Pisters states, ‘art as a circuit breaker is not an entirely clear, simple or ideal counterforce’ (Citation2013, 210). Rather, the circuit breaking capacity of art can be found in problematising ‘the complex and confusing affects of surveillance [by offering] alternative experiences of the surveillance system’ (Pisters Citation2013, 211).

To disrupt normalised and everyday encounters with surveillance and elude circuits of control, artists frequently turn to strategies of defamiliarisation. Thereby they challenge, complicate, or refuse attitudes of surveillance-apathy or apatheia. As critical data and media scholars Luke Stark and Kate Crawford (Citation2019) have shown, defamiliarisation mobilises feelings of productive discomfort and experiences of estrangement that can activate audiences to reflect on normalised data practices such as technological surveillance. To understand how such defamiliarising processes invite reflection, it is important to pay attention to the ways in which artists intervene into the interconnected domains of materiality and representation.

Material disruptions occur when artists use technologies of surveillance as artistic material – which is characteristic for the genre of surveillance art (Brighenti Citation2010; Cahill Citation2019). When a surveillance system is taken out of its usual context, altered, and placed into an exhibition space, its normalised presence becomes estranged. The creative use of CCTV cameras or facial recognition systems (for example) allows artists to intervene into the technological logics of these systems and repurpose them in ways that dismantle their routine operations or open up their black-boxed qualities (Pasquale Citation2015) to the spectator, who is then steered to critically reflect on them.

Moreover, artists defamiliarise surveillance by intervening into the domain of representation – into what is made present and how it is made present. As Rancière has argued, artists create changes in the symbolic or representational order and give shape to new ways of thinking about, and interfering in, politics.

Within any given framework, artists are those whose strategies aim to change the frames, speeds and scales according to which we perceive the visible, and combine it with a specific invisible element and a specific meaning. Such strategies are intended to make the invisible visible or to question the self-evidence of the visible; to rupture given relations between things and meanings and, inversely, to invent novel relationships between things and meanings that were previously unrelated. (Rancière Citation2010, 141)

These material and representational interventions involve the spectator in a visceral and emotional way. They produce affect, which is an unfamiliar embodied sensation and ‘that which forces us to feel’ (Quinan and Thiele Citation2020, 1). These embodied and visceral effects can function as a catalyst for critical reflection, because we are forced to make sense of it (Stark and Crawford Citation2019, 448; Hengel Citation2018, 134; Buikema Citation2017, 171). In other words, through intervening into the material and representational aspects of surveillance – in their technological logics and in the ways in which surveillance can be seen or otherwise perceived – art can mobilise a sense of estrangement and discomfort that triggers reflection. As these artistic interventions move beyond theoretical critique, and deploy emotional, audio-visual and material approaches to the subject-matter, they have the possibility to mediate expert knowledge to non-expert audiences (Alacovska, Booth, and Fieseler Citation2020; Wevers Citation2023).

Face Value: narrative and visual analysis

The Face Value exhibition explored how the surveillance and datafication of faces, voices and emotions impacts their social and cultural meaning. Through new-media art and an interdisciplinary panel sessionFootnote5, Face Value aimed to deconstruct biometric capture as a merely technological endeavour and reposition it as a social and political issue that requires critical interrogation. By presenting artworks that reveal how biometric surveillance has become deeply engrained into the structures of everyday life, the exhibition was an attempt to emphasise the urgency of understanding the harms and injustices that result from biometric surveillance as well as considering the need for imagining alternative futures.

I curated Face Value as a small group exhibition with a thematically-based organising structure, showing work by emerging and more established artists from different geographical and artistic backgrounds, namely Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Effi & Amir, Josèfa Ntjam, Martine Stig and Ningli Zhu. To encourage visitors to draw connections as well as reflect on contrasting positions in the encounters with the different artworks, I created an exhibition design in which visitors could move through the space in different directions. The exhibition theme was developed via three intersecting narrative threads, that worked to contextualise, but at the same time also emerged from the selection of artworks. The first narrative thread explored the role of biometric surveillance in everyday life. I made a selection of artworks that examine daily uses of biometrics, or that reflect on the day-to-day impact that biometric surveillance has on individuals. Second, the exhibition investigated how, rather than a neutral and objective endeavour, the datafication of faces, voices and emotions through technologies of surveillance has real, embodied effects and is embedded in complex structures of power. Third, the exhibition explored if and how faces, emotions and voices can be reclaimed in a context of continuous datafication. With this third thread, I aimed to foreground counter-narratives and explorations of alternatives to the normalised and normalising control of the face in the context of surveillance. Given the limited scope of this article, I now zoom in on three out of the five artworks that were presented in this narrative context, to analyse how they intervene in normalised surveillance circuits through strategies of defamiliarisation.

Returning the gaze of facial recognition algorithms: Heather-Dewey Hagborg’s How do you see me? (Citation2021)

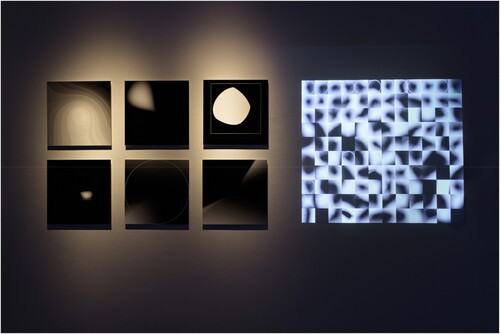

While we are increasingly ‘seen’, analysed and classified by facial recognition systems, their presence and operations remain to a large extent invisible to us. Exhibited as a video projection and a series of six digital prints (), the art installation How do you see me? by artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg renders visible what the biometric machine ‘sees’ when looking at a human face, and which information it deems important.

Figure 2. Installation shot Face Value. Heather Dewey-Hagborg, How do you see me? © Pieter Kers | Beeld.nu.

Through a technical intervention, for which the artist used adversarial processesFootnote6 to generate new images based on her self-portrait, the project intervenes into the system’s circuit and traces the moments in which an image is categorised as a face or recognised as Dewey-Hagborg’s face. This investigation is materialised in video and prints that show abstract black-and-white shapes, with blue and green lines indicating face- detection and recognition. The images reveal the system’s focus on white ovals, which can be interpreted as an indication of the normativity of whiteness that underlies facial recognition systems (Dewey-Hagborg Citation2021). While these shapes are full of signification for machine vision, to the human gaze they are almost completely unrecognisable, which engenders an estranging viewing experience.

By returning the algorithmic gaze of the facial recognition onto itself, Dewey-Hagborg temporarily destabilases normalised circuits of power. The abstract images that emerge from this intervention make tangible how facial recognition systems erase important meanings in the process of ‘informatizing the body’ (Van der Ploeg Citation2009) in ways that are out of our intuitive ability to understand and out of control of the surveilled subject. Moreover, they reveal how the system can be deceived, and momentarily disrupt its circuit of control by tricking it into recognising algorithmically-generated images as the face of the artist. The installation so confronts us with the limits of machine vision, and makes visible what gets lost in digital translation and transformation.

Embodying data: Effi & Amir’s Places of Articulation: Five Obstructions (2020)

The interactive installation work Places of Articulation: Five ObstructionsFootnote7 () by artists Effi & Amir critically investigates automated dialect detection software. This biometric form of surveillance is increasingly used in European asylum procedures to identify from which region asylum seekers originate when they cannot or refuse to show identification documents. On the background of the exhibition wall, visitors can see an illustration that the artists have taken from a manual published by the German immigration authorities (BAMF) that shows a demonstration of two people using dialect detection software. Via small screens that are connected to headphones, visitors can listen to five individuals who share, each in their own language, personal stories about the role of their voice in processes of identification and experiences of identity. While speaking, some of the voices also appear as data points, rendered visible as graphic visuals. Via a microphone that is attached to a sixth screen, visitors can interact with the artwork by speaking out loud so that a datafied version of their voice appears.

Figure 3. Installation shot Face Value. Effi & Amir: Places of Articulation. Five obstructions. © Pieter Kers | Beeld.nu.

Places of Articulation brings the technological process of voice-surveillance to the exhibition space and uses it as an artistic means to invite critical reflection. This material intervention can be encountered in the videos, in which the voices of the narrators are digitally visualised, tracked and analysed. Visitors are also invited to experience this transformation of voice to data by speaking into a microphone, that directly translates the sound of their voice to a graphic visualisation. Similar to Dewey-Hagborg’s How do you see me? this material intervention confronts with the erasure and abstraction that is at work in processes of biometric recognition and so evokes a sense of estrangement. Turned into visual graphics, it appears to be very difficult to recognise a visualisation of a datafied voice as one’s own.

As Torin Monahan argues, the integration of participatory elements in critical surveillance art can be an effective tool for inviting audience reflection:

By fostering ambiguity and decentering the viewing subject, critical surveillance art can capitalize on the anxiety of viewers to motivate questions that might lead to greater awareness of surveillance systems, protocols, and power dynamics. Works that use participation to make viewers uncomfortable can guide moments of self-reflexivity about one’s relationship – and obligation – to others within surveillance networks. (Monahan Citation2022, 89)

Places of Articulation combines this material intervention with a representational intervention that is enabled through the artistic strategy of storytelling. Storytelling is not merely focused on communicating information but offers a ‘sensory/sensuous experience’ that engages the spectator on an emotional level (Neill Citation2008). In a documentary-like filming style, the work foregrounds five personal stories about the role of the voice in processes of identification and experiences of gender, nationality, religion, class and migration. Each in their own way, the stories challenge the assumption that voices are a stable source of identification and show how they change over time and contain complexities that cannot be fully grasped by a dialect detection system.

Together, these interventions establish an estranging visual and affective contrast between embodied storytelling and the datafied graphics that erase this personal context and present the stories as disembodied information. By drawing attention to the human stories behind data, Places of Articulation critiques how biometric capture reduces human complexities, and more specifically, how in this process the ‘[v]oice loses its power as a means of self-affirmation, and is treated solely as fixed sound material – where the socio-cultural dimensions that colour its composition and determine its continuous becoming are ignored’ (Leix Palumbo, CitationForthcoming). Within the context of Face Value, the installation piece operates as a circuit breaker by constructing an ‘artistic counter-archive’ (Monahan Citation2022, 67–68) of personal stories that destabilise an assumption that is central to the circuit of biometric control, which is the idea that voices – similar to other biometric identifiers – carry a certain essential truth about identity that can be technologically extracted and quantified (Kruger, Magnet, and Van Loon Citation2008; Amoore Citation2006; Leix Palumbo, CitationForthcoming; Wevers, Citation2018).

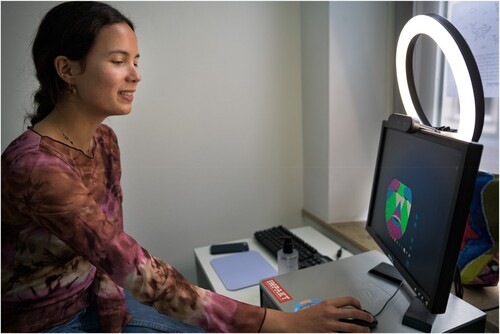

Reclaiming the digital face: Martine Stig’s WeAlgo (2021)

WeAlgo, by artist Martine Stig and programmer Stef Kolman, is an online meeting place where participants can communicate through self-designed digital facemasks (Figures and ). Footnote8 It uses facial recognition software to allow users to have face-to-face conversations – without storing their data. In Face Value, WeAlgo was exhibited as an interactive installation consisting of two parts: a screen with headphones, and a computer station in the hallway of the exhibition that was connected to a webcam. At this station, visitors could enter a private virtual room in WeAlgo and design their masked alter-ego. This mask was streamed in real-time on the video screen in the exhibition space. Through this interactive element, visitors could make their own digital portrait part of the exhibition narrative. During moments without visitor interaction, the screen showed a pre-recorded conversation between the artist and myself – in WeAlgo and hidden behind digital masks – in which we discussed how the project came about and addressed the ethical and political issues of working with facial recognition technology.

WeAlgo positions video conferencing technologies such as Zoom and Teams as an object of critique. During the Covid-19 pandemic, when Face Value was on show, the ‘free’ use of these tools became rapidly normalised and was implemented in the most intimate conversations – from online dates to therapy sessions – despite the fact that the companies offering those tools could extract data from these conversations and sell them to third parties. The designers of WeAlgo creatively intervened into these normalised uses by developing an alternative browser-based meeting space that does not collect, store, share or sell user data.Footnote9

Before entering WeAlgo, visitors can design their own digital face mask and so reclaim a form of anonymity in the digital sphere. Inspired by the concept of a masked ball, Stig and Kolman created a set of colourful lines, dots, shapes that allows for a playful practice of digital masking. The transformation of the visitor’s face to a digital mask happens through a material intervention that consists of a reappropriation of facial recognition software: WeAlgo captures landmark vector data of faces as the basis for the digital masks, so that the user’s emotional expressions can be mimicked. The visual language of facial recognition systems is explicitly represented in the mask’s design to draw the participant’s awareness to the process of informatic capture that is at work – and to invite reflection on the information that this software extracts from our effigies. Rather than affirming dominant myths of objectivity and neutrality, the project departs from biometrics’ fragmentation and failure to fully represent human faces. The platform’s interface is not dedicated to functionality, smoothness and convenience but to play, and thereby slows down routinised habits of online communication. This defamiliarising interface activates a critical distance when users engage in online conversations and thereby breaks the ‘circuit’ of surveillance capitalist processes of data extraction that usually remain covert or are experienced as normal.

The exhibition as a constellation of circuit breakers

By making normalised or hidden aspects of surveillance appear strange, the artworks in Face Value – however momentarily – interfere in circuits of biometric control. They do so through a variety of artistic strategies and approaches that, on an exhibitionary level, cause a series of complementary and sometimes contrasting disruptions. Drawing on Pisters’ discussion of the circuit-breaking potential of surveillance art (Citation2013), exhibitions could be understood as possible constellations of circuit breakers that constantly re-route and challenge the perspective of the visitor. While a single circuit breaker disrupts one stream of power – both in its physical and political sense – a constellation of circuit breakers leads to a sequence of disruptions that continuously ask the visitor’s attention and so challenges attitudes of surveillance apathy and apatheia. In today’s visual culture, that is characterised by the overload of images that people are confronted with on a daily basis, Marion Zilio argues that ‘creative activity cannot be a simple matter of critique or the manipulation of symbols. It must illuminate and reconfigure our attentional apparatuses from the perspective of care, meaning a long-term formation of attention’ (Citation2020, 101). By decelerating normalised circuits of surveillance and engaging the visitor in practices of attentive listening and viewing, Face Values sought to evoke such a sense of care.

In WeAlgo and How Do You See Me? this entailed a deceleration of daily encounters with surveillance in the context of video conferencing and social media. As the artworks highlight, these uses lead – often unconsciously – to the submission of personal data to digital databases. What happens with that data tends to stay out of the user's sight and control. By making some of these covert and abstract processes visible, the artworks in Face Value ask the spectator to pay attention to the moments in which facial data is saved, and to critically reflect on the ways in which it is classified. Together, the works thus operate as circuit breakers that disrupt routinised interactions with surveillance technologies and invite the spectator to rethink their relation to them.

The urgency of such critical reflection is stressed even further in Effi & Amir’s Places of Articulation. This work shifts the visitor's attention from every day, commercially-driven forms of surveillance to the governmental use of surveillance for border control and asylum-seeking procedures. As a spectator, one becomes a witness of five testimonials that make visible how voices are ambiguous markers of identity that are not static but emerge from a persistent becoming in relation to their socio-cultural context. Through giving space to such lived experiences, Face Value stresses the urgency of not remaining indifferent to biometric surveillance and question its role in processes of in- and exclusion.

Conclusion

In this article I have analysed the exhibition Face Value as an exemplary case study to investigate how art exhibitions can function as vehicles for disrupting normalised surveillance. Face Value framed a material and visual investigation of biometric control. Faces, voices, and emotions were taken as a point of departure to deconstruct biometric capture as a merely technological endeavour and reposition it as a social and political issue. Through juxtaposing different artistic strategies, such as storytelling, audience interaction, and play, Face Value activated different forms of interpellation in order to challenge attitudes of apathy and apatheia. The selection of artworks that I have discussed, WeAlgo, How do you see me? and Places of Articulation, demonstrate how art can activate a process of defamiliarisation (Stark and Crawford Citation2019), in which normalised or obscured elements of surveillance are made strange. By reappropriating surveillance technologies, looking back at the machinic gaze, foregrounding personal stories, and shaping alternatives, the artworks destabilise dominant circuits of surveillance control. These artistic interventions are not quick-fixes nor concrete solutions, but rather critical manifestations that activate the viewer to – as strikingly put by feminist philosopher Donna Haraway (Citation2016, 4) – ‘stay with the trouble’.

As I have sought to demonstrate in this article, these playful, speculative, personal, and critical interventions do not only operate in isolation but can amplify each other in the context of an exhibition. In problematising different elements of biometric control through a variety of artistic strategies, exhibitions can function as constellations of circuit breakers and so offer a fruitful context for the creation of new – and much needed – perspectives that make surveillance strange again. Due to the article’s methodological approach and the limited scope, I have not included an empirical, visitor-oriented analysis of the exhibition, nor attended to the role that research-creation (McKnight Citation2020) played in the construction of the exhibition. Further avenues of research into this topic could benefit from a more integrated approach.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to this article was funded by the Dutch Scientific Research Council (NWO) for the project ‘Opening Up the Black Box: Artistic Explorations of Technological Surveillance’. I would like to thank IMPAKT [Centre for Media Culture], and in particular Arjon Dunnewind, for our collaboration on Face Value, and all the artists for allowing me to exhibit their work. I would also like to thank my supervisors, prof. dr. Rosemarie Buikema, prof. dr. Beatrice de Graaf and dr. Evelyn Wan, for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rosa Wevers

Rosa Wevers (MA) works as a PhD candidate Gender Studies at Utrecht University. For her NWO-funded PhD research she analyses how contemporary art exhibitions in Western Europe, confront visitors with critical perspectives on surveillance, and engage them in strategies of resistance. In 2021, she curated the exhibition Face Value: Surveillance and Identity in Times of Digital Face Recognition, in collaboration with IMPAKT and the Netherlands Film Festival. Between 2017 and 2019, Rosa worked at Utrecht University as a teacher in Gender Studies, and as the coordinator of the Gender and Diversity Hub and as research assistant for Museum of Equality and Difference (MOED).

Notes

1 Following Mejias and Couldry (Citation2019), I define datafication as the quantification of elements of human life into digital code, which is a process through which a particular value is generated. An example of datafication in the context of surveillance is the moment in which a human face is digitally recorded and transformed into code so that it can be compared to other faces in a database. In this process, the face is turned into a valuable source of information for security purposes, while other meanings and values are erased.

2 The exhibition took place from 18 September until 10 October 2021 at IMPAKT [Centre for media culture] in Utrecht (the Netherlands). IMPAKT presents critical and creative views on contemporary media culture (see www.impakt.nl).

3 I borrow this term from philosopher Gilles Deleuze, who argues that surveillance should be understood as a networked mechanism through which citizens are ‘watched’ continuously as aggregates of information (which he calls ‘dividuals’). Control is no longer confined to the space of institutions, but dispersed throughout society and directed to people not as individual bodies but as aggregates of information (Deleuze Citation1992).

4 See for example the European Citizen’s Initiative ‘Reclaim your Face’, which is organised by multiple European Digital Rights organisations including EDRI and BITS OF FREEDOM.

5 The hybrid panel session, that I organised as part of the NFF festival in 2021, offered a more in-depth understanding of how biometric technologies discriminate and have a negative impact on human rights and freedom. Together with the four speakers (Christine Quinan, Nakeema Stefflbauer, Ella Jakubowska and Heather Dewey-Hagborg) we addressed the urgency of approaching this topic as a complex issue that requires a multi-disciplinary approach, as it touches upon issues of technology, law, policy, culture, gender, race and class.

6 Adversarial processes are algorithms that generate new images based on given input.

7 From now on abbreviated as Places of Articulation.

8 The design team of WeAlgo consists of Martine Stig (artist), Stef Kolman (product developer), Tomas van der Wansum (software developer, encryption specialist) and Roel Noback (front-end Javascript developer).

9 Nevertheless, WeAlgo cannot be claimed as an innocent artistic practice, as it uses facial recognition software to capture facial information and this software is never inclusive and fails to recognize persons. From a curatorial point of view, I was thus hesitant about whether to include this artwork in the exhibition. After considerations with the artists, we took multiple steps to account for this problem. In a practical sense, we sought for databases that were designed to make recognition software more inclusive, such as the Pilot Parliaments Benchmark Dataset created by the Algorithmic Justice League and researcher Joy Buolamwini (to which we unfortunately never received access) and the open-access Fair Face Dataset. Kolman Kolman used these to test the software on. It must be noted that the faces of participants in the exhibition were not classified in terms of gender and ethnicity. Furthermore, we ordered a ‘selfie ring’ that we installed at the computer station to optimize the light settings – which is crucial for camera recognition. Moreover, I decided to make this issue explicitly part of the exhibition narrative. In the screened conversation between me and Stig, that was on show in the exhibition space, we reflected upon the exclusionary mechanisms of facial recognition technology and discussed the steps that the artist had taken to erase as much bias as possible. Furthermore, the exhibition text explicitly mentioned that the risk of misrecognition was present and invited visitors to get in touch with the exhibition host when this would occur. The hosts would then notify the artists.

References

- Alacovska, Ana, Peter Booth, and Christian Fieseler. 2020. “The Role of the Arts in the Digital Transformation.” Artsformation Report Series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3715612.

- Amoore, Louise. 2006. “Biometric Borders: Governing Mobilities in the War on Terror.” Political Geography 25 (3): 336–351. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.02.001.

- Bal, Mieke. 1996. Double Exposures. The Subject of Cultural Analysis. New York: Routledge.

- Blas, Zach, and Jacob Gaboury. 2016. “Biometrics and Opacity: A Conversation.” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 31 (2): 155–165. doi:10.1215/02705346-3592510.

- Brighenti, Andrea Mubi. 2010. “Artveillance: At the Crossroad of Art and Surveillance.” Surveillance and Society 7 (2): 137–148. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2010.12.002.

- Browne, Simone. 2015. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Buikema, Rosemarie. 2017. Revoltes in de Cultuurkritiek. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Buzan, B., and O. Wæver. 2003. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cahill, Susan. 2019. “Visual Art, Corporeal Economies, and the “New Normal” of Surveillant Policing in the War on Terror.” Surveillance & Society 17 (3/4): 352–366. doi:10.24908/ss.v17i3/4.8661.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1992. “Postscript on the Societies of Control.” October 59: 3–7.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1995. “Control and Becoming.” In Negotiations 1972–1990, edited by Martin Joughin, 169–176. New York: Colombia University Press.

- Dewey-Hagborg, Heather. 2021. “The Politics of Face Recognition.” Utrecht.

- Ellis, Darren. 2020. “Techno-Securitisation of Everyday Life and Cultures of Surveillance-Apatheia.” Science as Culture 29 (1): 11–29. doi:10.1080/09505431.2018.1561660.

- Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hengel, Louis. 2018. “The Arena of Affect: Marina Abramović and the Politics of Emotion.” In Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture: A Comprehensive Guide to Gender Studies, edited by Rosemarie Buikema, Liedeke Plate, and Kathrin Thiele, 123–135. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jones, Chris, Jane Kilpatrick, and Yasha Maccanico. 2022. “Building the Biometric State: Police Powers and Discrimination.” https://www.statewatch.org/media/3143/building-the-biometric-state-police-powers-and-discrimination.pdf.

- Krause, Michael. 2018. “Artistic Explorations of Securitised Architecture and Urban Space.” In Architecture and Control, edited by Annie Ring, Henriette Steiner, and Kiristin Veel, 128–156. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. doi:10.1163/9789004355620

- Kruger, E., S. Magnet, and J. Van Loon. 2008. “Biometric Revisions of the ‘Body’ in Airports and US Welfare Reform.” Body & Society 14 (2): 99–121. doi:10.1177/1357034X08090700.

- Leix Palumbo, Daniel. Forthcoming. “The Weaponisation of Datafied Sound: The Case of Voice Biometrics in German Asylum Procedures.” In Doing Digital Migration Studies, edited by Koen Leurs, and Sandra Ponzanesi. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Lidchi, Henrietta. 1997. “The Poetics and Politics of Exhibiting Other Cultures.” In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, edited by Stuart Hall, 151–222. London: Sage/Open University.

- Madianou, Mirca. 2019. “The Biometric Assemblage: Surveillance, Experimentation, Profit, and the Measuring of Refugee Bodies.” Television and New Media 20 (6): 581–599. doi:10.1177/1527476419857682.

- Magnet, Soshana Amielle. 2011. When Biometrics Fail. Gender, Race, and the Technology of Identity. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mann, Steve, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman. 2003. “Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments.” Surveillance and Society 1 (3): 331–355. doi:10.24908/ss.v1i3.3344.

- M’charek, Amade, Katharina Schramm, and David Skinner. 2014. “Topologies of Race: Doing Territory, Population and Identity in Europe.” Science, Technology & Human Values 39 (4): 468–487. doi:10.1177/0162243913509493.

- McKnight, Stéphanie. 2020. “Creative Research Methodologies for Surveillance Studies.” Surveillance and Society 18 (1): 148–156. doi:10.24908/ss.v18i1.13530.

- Mejias, Ulises A., and Nick Couldry. 2019. “Datafication.” Internet Policy Review 8: 4. doi:10.14763/2019.4.1428.

- Monahan, Torin. 2022. Crisis Vision. Race and the Cultural Production of Surveillance. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Moser, Stephanie. 2010. “The Devil is in the Detail: Museum Displays and the Creation of Knowledge.” Museum Anthropology 33 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01072.x.

- O’Neill, Paul. 2007. “The Curatorial Turn: From Practice to Discourse.” In Issues in Curating Contemporary Art and Performance, edited by Judith Rugg, and Michèle Sedgwick, 13–28. Bristol: Intellect.

- O'Neill, Maggie 2008. “Transnational Refugees: The Transformative Role of Art?” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 9: 2. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802590.

- Pasquale, Frank. 2015. The Black Box Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pisters, Patricia. 2013. “Art as Circuit Breaker: Surveillance Screens and Powers of Affect.” In Carnal Aesthetics, edited by Bettina Papenburg, and Marta Zarzycka, 198–213. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Ploeg, Irma. 2009. “Machine-Readable Bodies: Biometrics, Informatization and Surveillance.” Identity, Security and Democracy, 85–94. doi:10.3233/978-1-58603-940-0-85.

- Pugliese, Joseph. 2005. “In Silico Race and the Heteronomy of Biometric Proxies: Biometrics in the Context of Civilian Life, Border Security and Counter-Terrorism Laws.” Australian Feminist Law Journal 23 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1080/13200968.2005.10854342.

- Quinan, C L, and Mina Hunt. 2022. “Biometric Bordering and Automatic Gender Recognition: Challenging Binary Gender Norms in Everyday Biometric Technologies.” Communication, Culture and Critique 15 (2): 211–226. doi:10.1093/ccc/tcac013.

- Quinan, Christine, and Kathrin Thiele. 2020. “Biopolitics, Necropolitics, Cosmopolitics–Feminist and Queer Interventions: An Introduction.” Journal of Gender Studies 29 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/09589236.2020.1693173.

- Rancière, Jacques. 2010. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. London: Continuum.

- Selinger, Evan, and Hyo Joo Rhee. 2021. “Normalizing Surveillance.” De Gruyter 22 (1): 49–74. doi:10.1515/sats-2021-0002.

- Sheikh, Simon. 2013. “Towards the Exhibition as Research.” In Curating Research, edited by Paul O’Neill, and Nick Wilson, 32–46. London: Open Editions/de Appel.

- Stark, Luke, and Kate Crawford. 2019. “The Work of Art in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: What Artists Can Teach Us About the Ethics of Data Practice.” Surveillance and Society 17 (3–4): 442–455. doi:10.24908/ss.v17i3/4.10821.

- Wevers, Rosa. 2018. “Unmasking Biometrics ‘Biases: Facing Gender, Race, Class and Ability in Biometric Data Collection.” Tijdschrift Voor Mediageschiedenis 21 (2): 89–105. doi:10.18146/2213-7653.2018.368.

- Wevers, Rosa. 2023. “Caged by Data: Exposing the Politics of Facial Recognition Through Zach Blas’ Face Cages.” In Situating Data, edited by Karin van Es, and Nanna Verhoeff, 159–172. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.5117/9789463722971

- Wood, David Murakami, and C. W. R. Webster. 2009. “Living in Surveillance Societies: The Normalisation of Surveillance in Europe and the Threat of Britain’s Bad Example.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 5 (2): 259–273. doi:10.3347/kjp.1992.30.2.65.

- Zilio, Marion. 2020. Faceworld. Translated by Robin MacKay. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. London: Profile Books.