ABSTRACT

As with many popular texts promising templates for successful storytelling, The Writer’s Journey claims that a singular story structure applies to all voices and circumstances, therefore funnelling every character journey into a ‘universal neutral’. This article offers queer temporality as a lens through which to unravel the 12 steps of Vogler’s hero’s journey, informed by queer theory’s critiques of the 8 steps of the heteronormative life journey . It joins other studies critiquing the paradigm from other standpoints, including Indigenous screen storytelling, gaming and interactive narratives, and for development of characters disenfranchised by gender and/or circumstance. Others note the model’s increasing irrelevance as writers uncover its limitations for creative processes of story development. This article homes in on how studies of queer temporalities – rejecting ‘dominant temporal logics’ and ‘chrononormativity’, replacing ‘straight time’ with ‘queer time’, can further destabilise the hero’s journey’s dominance in story development by exploring the breadth of practices in creative writing and screen production beyond the universalising models.

Business as usual is what created this mess in the first placeFootnote1

The continued defence of homogenising models, such as the hero’s journey, is curious, because it suggests there is something to be lost when we stop pretending that we are all the same, devoid of specificity related to the intersections of our race, gender, class, sexuality, body, neurology, and global circumstances. It seems to insist on pushing forward individualism over the collective and, beyond characters and worlds, to protect a division between content and form, whereby the latter is merely the map onto which all stories fit – and to which all lives should aspire. Christopher Vogler, author of The Writer’s Journey celebrates the hero’s journey (on which his book is based) as ‘the recognition of a beautiful design, a set of principles that govern the conduct of life and the rules of storytelling’ (Citation2007 [1998], xiii). Humankind is susceptible to latching on to blueprints for living, even when contemporary conditions suggest these ideas are outdated, or carry with them dangerous assumptions and questionable interpretations. The directives for lives lived correctly underpin the ways our stories are structured and delivered to the mainstream, creating a feedback loop of (hetero)normativity.

Critiques of the ‘universal’ run through feminist and queer theory. The same ‘universal’ is assumed in dominant storytelling formulae, such as the hero’s journey, centralising male, ableist experience, heteronormative life narratives and a colonial paradigm of problem-resolution. Buried within are barriers to exploring the specific consequences of marginalisation, limiting the types of stories told and the voices telling them. This is particularly true for screenwriting practice whose flourishing how-to market of guidebooks is uniquely formulaic and prescriptive, prompting screenwriting scholar Steven Maras to invite challenges to universal forms of story (Citation2017). Regardless of the growing critiques, the hero’s journey template remains standard in the mainstream.

To challenge the hero’s journey paradigm is not controversial. Studies taking up this call include investigations into the limitations of these forms for Indigenous screen storytellers (Hambly Citation2020; Citation2021; Milligan Citation2022), gaming and interactive narratives (Jennings Citation1996; Koenitz et al. Citation2018) and case studies on characters disenfranchised by gender and/or circumstance (Cleary Citation2020; Dancyger and Rush Citation2013). Even in craft terms, the hero’s journey has frequently proved inadequate for commercial realities (Mullins Citation2021) despite its claims to being the supreme narrative pattern.

Unravelling the hero’s journey through queer theory may help us further rethink the primacy of the dominant story structure models (particularly those prescribed to screenwriters) that have a hold on both the discipline and the craft, and regenerate in different incarnations over decades with little to differentiate them.

It is the story that hid my humanity from meFootnote2

Vogler’s text is full of invitations to adapt ‘the mythic pattern to his or her own purpose or the needs of a particular culture’ (Citation2007, 7), throwing the onus on those outside the default subject position (straight, white, able-bodied, cisgendered man) to do the labour. This involves adjusting stories and characters to fit models built for very limited subjectivities, not only as creators but also readers and viewers. The 12-steps of Vogler’s structure wisely bypass stages such as ‘Woman as Temptress’ from Campbell’s original template, but otherwise efforts to be gender neutral are largely cursory and framed in binary ways around love interests and ‘the opposite sex’. Few women (or humans who are not cisgendered men) are convinced by these concessions.

Feminist responses to the hero’s journey have been largely limited to adapting the archetypal systems into ‘heroines’ journeys’ in an attempt to incorporate female otherness (Carriger Citation2020; Murdock Citation1990; Schmidt Citation2011). Helen Jacey (Citation2010a) has challenged the universality of Vogler’s hero’s journey, where avoiding difference serves to exclude women’s experience, but is also wary of heroine’s journey models born of Jungian feminism, such as Murdock’s, which assume innately feminine natures and conflate biological and gender difference. Still dealing in binaries, but resisting the conflation of sex and gender, Gail Carriger (Citation2020)’s formulation of a heroine’s journey works with the same constructs of gender that queer theory critiques by insisting the parallel of the hero’s and heroine’s journey be applied according to gendered narrative arcs, not the protagonist’s assigned biological sex.

Meanwhile, the claim that Campbell’s ‘pattern lies behind every story ever told’ (Vogler Citation2007, 4) is put into question the moment popular or ‘classic’ screen stories are adapted for marginalised characters, inviting protests from those who are used to seeing themselves as central to the journey. The offending characters include female timelords, black mermaids and ghostbusting teams of women – in the case of the latter, angry fans of the original film Ghostbusters (Citation1984) mobilised to ‘1-bomb’ popular online screen database IMDb with 1/10 reviews of the rebooted Ghostbusters (Citation2016) without seeing the film (Hayes Citation2016). When marginalised characters become central to original stories, this also tends to alienate those used to occupying the dominant subject position. Animated feature Turning Red (Citation2022), despite following production house Pixar’s structural staple of the hero’s journey (Rosario Citation2022), was famously reviewed by CinemaBlend Managing Editor Sean O’Connell as too specific and narrow in its scope, due to its cultural setting of Toronto’s Asian communities (Menon Citation2022). Defending his assessment, O’Connell reported (via Twitter) feeling exhausted by a story – centred upon a 13-year-old Chinese Canadian girl hitting puberty – in which he could not see himself (Ibid). O’Connell was apparently unaware he was experiencing the fatigue already felt by those who must regularly take imaginative leaps in order to identify with mainstream central characters. In other words, the so-called universal and flexible form fails to convince even those who occupy its inbuilt default settings when bent to the will of a story from the margins.

Queer lives would not follow the scripts of conventionFootnote3

Linear models, punctuated by an individual’s trajectory over a series of milestones, dominate story development processes, drawing on those same temporal understandings arising from heterosexual ideologies. D.A. Miller suggests that Brokeback Mountain (Citation2005), the story of a complex sexual affair between two cowboys, was not so much celebrated for its queer themes as its ability to be ‘universally’ palatable despite them. Miller tracks the overwhelming tenor of the film’s critical acclaim wherein director Ang Lee is lauded for his lack of overt politics and overall restraint in a craft-centred ‘rhetoric of discretion’ (Citation2007, 52), which includes a New York Review of Books review which praised the film as being ‘so well told that any feeling person can be moved by it’ (Mendelsohn Citation2006) (emphasis added). Likewise, The Kids Are All Right (Citation2010), navigating the love triangle between two queer women and their sperm donor, invites claims that it is ‘a “universal” story about family rather than a film about lesbians’ (Kennedy Citation2014, 120). This might broaden the appeal for a mainstream audience, but it also reminds us that received wisdoms of the ‘universal’ render it synonymous with normal and, by association, with heterosexual (Walters Citation2012). Such critical evaluations of the ‘universal’ across the breadth of screen creation and reception should give pause to those imposing the application of models claiming all stories have ‘common structural elements found universally’ (Vogler Citation2007, xxxvii), such as the hero’s journey.

Of course, many screen stories centred upon LGBTQIA + protagonists are told using universalising structures, and are often held up as triumphs of representation – for example, the coming-of-age queer teen drama Love, Simon (Citation2018). This optimism is unsurprising, given the historical dearth of queer characters on screen (beyond the alarming and reductive tropes including psychopaths, sidekicks and #buryyourgays) and the perceived opportunity for queer viewers to take a break from finding ways to ‘relate’ to central characters that are almost never someone like them. Queer coming out stories map neatly onto the hero’s journey structure, whereby an epiphany triggers coming out of the proverbial closet, ‘a move that is framed as a path towards maturity’ (Windhauser Citation2023, 198). While it is tempting to celebrate stories that centre upon positive representation of queer adolescents (Windhauser Citation2023), such narratives reinforce aspirational notions of transformation while minimising the circumstances within which young queer folx must hide to survive. Though we may be committed to challenging conservative notions in our content, we risk reinforcing them through structural convention (Dancyger and Rush Citation2013).

Vogler believes ‘stories are metaphors by which people measure and adjust their own lives by comparing them to those of the characters’ (Citation2007, 300) (emphasis in original) but the kinds of stories that his formula tends to generate for mainstream screens requires a certain performance of normative values ‘in order to be deemed respectable and/or accepted within the diegesis of the film and by the audience’ (Mccollum and Gaffney Citation2021, 240). Fictionalised queer lives, funnelled into narrative structures predicated on a ‘universal neutral’ and underpinned by heteronormative understandings of time, create stories that are inherently not-queer. This is reflected in the universalising and domesticating tactics for producing, marketing, and reviewing queer screen stories (Kennedy Citation2014; Miller Citation2007; Walters Citation2012) that serve to erase queer difference and experience. As the cynical gay podcaster (played by Billy Eichner) in the comedy feature Bros (Citation2022) rails of a thwarted romantic comedy commission:

He said, “Bobby, we just want to make a movie that shows the world gay and straight relationships are the same. Love is love is love.” I said, “Love is love is love? No, it’s not. That’s bullshit. That is a lie we had to make up to convince you idiots to finally treat us fairly. Love is not love. Our relationships are different. Our sex lives are different”.

There are few, if any, specifically queer critiques of the hero’s journey itself. As Whitney Monaghan argues, the ‘efficacy of queer theory lies in its capacity for resistance: to normativity, to rigid binaries, to linearity’ (Citation2016, 34), which suggests queer theory offers a utility beyond the linear, binary model offered by the hero’s journey. It is important to bear in mind that, as Annamarie Jagose argues, there are intellectual traditions beyond queer theory ‘in which time has also been influentially thought and experienced as cyclical, interrupted, multilayered, reversible, stalled’ (Dinshaw et al. Citation2007, 186). However, queer theory brings with it a range of challenges to heteronormative temporal logics and while these ideas, as will be discussed, are sometimes conflicting, they might also be leveraged to encourage more destabilising of the hero’s journey’s ubiquity in storytelling analysis and craft. ‘When we imprison our stories in strict formulations’ Anthony Mullins reminds us ‘we shut ourselves off from authenticity and truth in storytelling’ (Citation2021, 19). The strategies of resistance offered by queer theory may hold some clues to further destabilising the paradigms, offering ways to leverage linear disruption, to reject tacit definitions of a complete life, and find a language for devising methods less invested in linear momentum than lateral connection.

Strategy: rejecting chrononormativity by moving through and with time

Over-reliance on such frameworks as the hero’s journey and its claims to universalism, ignores the limitations and corruptions within complex circumstances that belie illusions of freewill (Dancyger and Rush Citation2013). Chrononormativity, as defined by Elizabeth Freeman, is ‘the use of time to organise human bodies toward maximum productivity’ (Citation2010, 3). A formula like Vogler’s is ideally placed to help feed a chrononormative system, given its reliance on heteronormative linearity. Its claims to universality are bolstered by its alignment with chrononormativity’s functionality as ‘a mode of implantation, a technique by which institutional forces come to seem like somatic facts’ (Freeman Citation2010, 3). In other words, what might seem universal may in fact be merely ubiquitous thanks to strategic integration into the popular imaginary.

Anyone familiar with how-to guides for writers will recognise how challenges to heteronormativity reveal its striking resemblance to story structure conventions. Freeman argues that we are rewarded for lives that can be narrated in state-sanctioned terms, and ‘as event-centered, goal-oriented, intentional, and culminating in epiphanies or major transformations’ (Citation2010, 5). Sitting somewhere between the anti-futurity and utopian theses of queer temporality (McCann and Monaghan Citation2020), Freeman believes queer temporalities can facilitate ‘moving through and with time, encountering pasts, speculating futures’ (Citation2010, xv) (emphasis added). Applying this idea to developing plots, stories and their narrative applications might mean a (dis)organisation principle that is willing to move through and with time according to which element of the burgeoning story presents itself as in need of attention.

Creating her critically acclaimed and multi-award winning 2017 comedy stage show Nanette was difficult for comedian and author Hannah Gadsby because ‘there is no straight line to be found through trauma’ (Gadsby Citation2022, 324). Writing the hour of stand-up based on traumatic events, including violent homophobia, that had previously been used as comic material, saw Gadsby with content that refused to conform to a structure. Gadsby describes the challenge of developing a cohesive form from the ‘three, contradictory shapes’ (Citation2022, 327) that emerged in the development: ‘Every time I felt myself panicking about the impossibility of making all the pieces fit, I reminded myself: one idea at a time. And I would set the unfinished idea aside and strike up a conversation with a different one’ (Gadsby Citation2022, 326) (emphasis in original). By resisting the urge to funnel these unruly ideas into an existing template, Gadsby was engaged in a process of queering that ‘involves not deciding one’s desire in advance and not shutting off (disavowing) avenues that it might take’ (Campbell et al. Citation2023, 142). Her triad eventually came together with the realisation that three elements – the material, the shape and, importantly, the space between them – were each a discrete layer, and Gadsby commenced the intricate work of weaving them together.

While Gadsby would go on to use the mechanics of the show as content, referencing structure as part of its design (particularly set-ups, punchlines and missing third acts), it was not an external application of a dominant story paradigm that got her there. Neither the process, nor the product, conformed to straight temporality. Gadsby moved through and with time to create a story that, at its core, was a searing critique of heteronormative patriarchy – and developed without using its tools.

Strategy: rejecting dominant temporal logics

Queer stories cannot be held by structures born of heteronormativity, or directly mapped onto straight trajectories. Scholarship into queer temporality challenges the ‘ways that dominant heterosexual ideology comes to shape our understandings of the temporality of social life’ (Monaghan Citation2016, 14). Queer theory’s critiques of upwardly mobile fantasies (Ahmed Citation2010; Berlant Citation2011) illuminate assumptions that queer lives lack the elements required. Vogler’s structure, promising stories that supply ‘abundant, time-tested strategies for survival, success and happiness’ (Citation2007, xiv), can be seen as contributing to the social happiness scripts that ‘encourage us to avoid the unhappy consequences of deviation by making those consequences explicit’ (Ahmed Citation2010, 91).

Put another way, we cannot all ‘trust the path’ (Vogler Citation2007, 365–370) because the path offered is predicated on normalised life narratives by which many of us are ‘rejected or blatantly pathologised’ (McCann and Monaghan Citation2020, 217). It is not simply a case of non-linear design – ‘shuffling’ the stages of a hero’s journey (Vogler Citation2007), or shifting around Acts 1, 2 and 3 for a better beginning, middle and end (Aronson Citation2010) – but an acknowledgement that (sub)culturally specific relationships with time wildly differ.

Jack Halberstam is the first to admit that claims to uniquely queer time might be ‘overly ambitious’ (Citation2005, 12), but argues nonetheless that queerness ‘has the potential to open up new life narratives and alternative relations to time and space’ (Citation2005, 13) (emphasis added). He offers queer time as a utility ‘to make clear how respectability, and notions of the normal on which it depends, may be upheld by a middle-class logic of reproductive temporality’ (Citation2005, 17). In this way he invites us to bend our minds around received logics as a stratagem of resistance against the imposition of normal.

To apply this exercise to the hero’s journey, which according to Vogler is ‘nothing less than a handbook for life, a complete instruction manual in the art of being human’ (Citation2007, xiii), it is tempting to track the model against the eight stages of heteronormativity (McCann and Monaghan Citation2020, 216):

Table 1. Comparing Vogler’s Hero’s Journey, The Three Act Structure and the 8 Stages of Heteronormativity.

Of course, it is possible to overlay any linear template over another and extract some sort of meaning. There are likely countless ways to click these three together, and the birth-to-death metaphor applies neatly here, especially given the habit in white, western cultures of referring to one’s senior years as the third act.

Vogler contends that ‘the basic metaphor of most stories is that of the journey’ (Citation2007, 300) and, therefore, would be unlikely to take exception to the above table of comparisons, but it does demonstrate the problematic linearity – in queer theory terms – of all three trajectories. It draws attention to the connection between societal norms and dominant storytelling patterns, both of which are invested in the primacy of those lives that conform to temporal logics and celebrated milestones, and the marginalisation of those that do not (Monaghan Citation2016). It is neither possible, nor desirable, to create a comparable, one-size-fits-all template for uniquely queer storytelling. The quest is to find queer story engines driven by something other than a constant forward momentum towards milestones, transformations, and epiphanies.

Game designers arguably lead the way in queer approaches to story development, identifying tacit norms and ‘finding points of rupture that destabilize those assumptions, opening up those fields to a wider and potentially more liberatory set of possibilities’ (Clark Citation2017, 4). Game creators like Avery Alder, Joli St Patrick and merritt kopas encourage fellow designers to decentralise the single, human player – the hero – by deconstructing genres in order to undermine their conventions (Clark Citation2017). Alder’s own practice, tabletop role playing games design, values the progress of the collective over the individual and embraces ‘the subversive potential of the anticlimax’ (Ruberg Citation2020, 183). An anticlimax, in hero’s journey terms, would be to build to the moment of resurrection, but then refuse to pay it off, leaving the protagonist untransformed, unchanged by what has been endured.

If, as Halberstam argues, ‘[q]ueer subcultures produce alternative temporalities [whereby] futures can be imagined according to logics that lie outside of those paradigmatic markers of life experience – namely, birth, marriage, reproduction, and death’ (Citation2005, 14), then stories can be imagined in the same way.

Table 2. The Third Act.

Cartoonist Alison Bechdel has said ‘I never learned queer time […] but I was just out living – living my queer time, not having the normal benchmarks that straight people did, not getting married, or having children, being thought of as having some kind of arrested development’ (Citation2022, 1:08:07–1:09:01). But of her bestselling graphic memoir Fun Home: A Queer Tragicomic (2006), Meghan Fox describes Bechdel’s accomplished queering of time, whereby ‘queer futurity is simultaneously contingent on an affective engagement with the past […] her father’s closeted same-sex desires and the loss of his life, as well as a hopeful vision of the future’ (Citation2019, 532). In the book, Bechdel makes explicit her rejection of the hero’s journey paradigm in the final chapter ‘The Antihero’s JourneyFootnote4’, in which the climax is replaced with ‘a cop out’ (Citation2006, 230) and conflict is avoided by all concerned, with a letter from Bechdel’s father where ‘he does and doesn’t come out to me’ (Citation2006, 230).

Fox notes that ‘Inversion is part of the queer formal structure […], which rejects linear narratives and temporalities, turns in on itself’ (Citation2019, 515). Bechdel is positive that ‘being queer has enabled me to play with time in a way that might come to me more easily since I wasn’t built into all those pre-existing time markers’ (Citation2022, 1:09:02–1:09:20). The narrative strategy of Fun Home is one that pivots on the epicentre of queer subjectivity, whereby ‘a shift of the centre/periphery model […] makes a clear statement about the importance of queer lives’ (2019, 524), by not pursuing individual resurrection and audience catharsis as part of a three-act structure.

Strategy: resisting ‘straight’ time

Scholarship into queer temporalities tends ‘to fall on either side of opposing anti-social and affirmative perspectives’ (Monaghan Citation2016, 14). However, as Monaghan goes on to explain, both sides of the debate highlight the valorisation of linear narratives of progress born of heteronormative temporal logics (Citation2016). José Esteban Muñoz defines ‘straight time’ as ‘an autonaturalizing temporality’ (Citation2009, 22) which casts queers ‘as people who are developmentally stalled, forsaken, who do not have the complete life promised by heterosexual temporality’ (Citation2009, 98) – for instance, the abovementioned perceptions of arrested development experienced by Bechdel.

Rejecting straight time in favour of queer time might look like ‘privileging of delay, detour, and deferral’ (Freeman Citation2010, xvi) and ‘narrative without progress’ (Halberstam Citation2011, 88). It might look like the popular American teen drama series Euphoria (Citation2019-), in which the ‘complex depiction of gender and sexuality is ultimately mirrored in the show’s nonlinear format: both the show’s narrative and the characters’ sexual and gendermarkers remain indistinct, fluid, and ephemeral’ (Macintosh Citation2022, 31). It might look like author Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House (Citation2019), which ‘is a radical innovation of memoir, using over one hundred different chapters, each styled after a genre or mode of writing’ (Bussey-Chamberlain Citation2021, 260). The fragments reflect the complexity of Machado’s story and the structure resists contriving an account of domestic abuse into a journey of transformation. As Prudence Bussey-Chamberlain writes, it is important to ‘voice experience through formal experimentation that is more representative of what it means to speak from a marginalized position than purely relying on content to convey meaning’ (Citation2021, 270).

In actor Elliot Page’s memoir Pageboy, memories of navigating queerness and gender ‘shape a non-linear narrative, because queerness is intrinsically non-linear’ (Citation2023, x). His book pulls the reader back and forward through time, in ways that transcend narrative application (even hero’s journeys can be structured using non-linear design) and is instead reminiscent of Natalie Loveless’ encouragement to ‘pay attention not only to which stories we are telling and how we are telling them, but how they, through their very forms, are telling us’ (Citation2019, 24) (emphasis in original). Manifestoes like Loveless’ arrive when new and improved storytelling templates are insufficient, each claiming to deliver fewer directives than the rest while ultimately prescribing a new set of rules.

In a manifesto for queer screen production, the authorsFootnote5 invite storytellers to ‘embrace disruption of the ever-forward momentum’ (Taylor et al. Citation2023, 5). To attempt story development using queer time instead, might mean turning away from hero’s journeys and towards Ursula K. Le Guin’s carrier bag theory of fiction, the purpose of which is ‘neither resolution nor stasis but continuing process’ (Citation2019 [1998], 35). Perhaps time does not need to build towards a high stakes conflict followed by the myth of resurrection and emotional catharsis. It is reductive, according to Le Guin, to conflate narrative with conflict, yet complications and climaxes born of conflict drive hero-driven narrative models.

Other feminist strategies can be leveraged to reject the primacy of conflict as a narrative tool. Helen Jacey promotes the development of what she has termed ‘layers of union’, to take ‘precedence over the conflict, jeopardy and stakes’ (Citation2010b, 147) demanded by dominant storytelling paradigms. Le Guin’s carrier bag holds conflict, stress and struggle as ‘necessary parts of a whole’ (Ibid.) She calls for ‘beginnings without ends […] far more tricks than conflicts, and far fewer triumphs than snares and delusions’ (Ibid.) Page’s queering of the memoir form reflects a life lived queerly, ‘Two steps forward, one step back’ (Citation2023, x).

Strategy: ‘growing sideways’ into lateral structures

Kathryn Bond Stockton challenges entrenched linearities, inviting us to reconsider the notion of growing up, arguing instead for width, where motives and experiences are not tethered to age and we, in fact, grow sideways (Citation2009). A ‘growing sideways’ approach to story development practice would reject the demands for an active protagonist made by so many editorial red pens, recognising that smuggled into this definition of active is the imperative for linear progression (and all the assumptions about what that means). Queered story development might be invested instead in creating a world in which characters navigate their relationships with each other, with no aim to transcend the refuge of the margins.

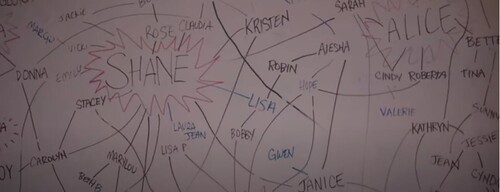

In ‘Let’s Do It’ (2007), the second episode of television drama The L Word (2004–2009), the character Alice Pieszecki (Leisha Hayley) maps the lateral connections of the world of the series; the lesbian scene of Los Angeles. She explains, ‘the point is we're all connected, see? Through love, through loneliness, through one tiny, lamentable lapse in judgement. All of us, in our isolation, we reach out from the darkness, from the alienation of modern life, to form these connections’ ('Pilot: Part 2', Citation2004). An iconic image for fans of the series is the visual aid accompanying this declaration, where Alice tracks each of these relationships on a whiteboard, making an intricate web of names connected by lines ().

Figure 1. ‘The Chart’, The L Word, Season 1 Episode 2 (2004), 38:50.

While not suggesting this scene reflected the process of the series’ script developmentFootnote6, it is a way to visualise a ‘growing sideways’ approach to creating a story where ‘timescales may warp, plots are inconclusive and characters are rule-breakers’ (Campbell et al. Citation2023, 142). A web, as opposed to a timeline, discourages the standardisation of development where the only questions asked in the ‘service’ of ‘breaking’ the story are around what a single protagonist wants and what is stopping them from getting it.

Australian queer filmmaker Angie Black has made a method out of creating such lateral connections and then disrupting them in ways that will dictate the direction of the story at the shooting stage of production. As they explain of their film The First Provocation (Citation2015), the scripted scenes are merely predictions, and the story will unfold depending on how a character responds to the arrival of an unexpected performance, the knowledge of which is withheld from cast and crew. As part of exploring ‘the unexpected in its content and form’ (Black Citation2015, n.p.), the filmmaker argues that ‘[i]t is not just that the work produced investigates themes of queer identities and sexuality, but also that the film process is in itself unstable and queer’ (Black Citation2019, 9) and, by extension, so is the story.

Conclusion, or, enjoy happy endings responsibly

Hollywood’s classical design, which includes Vogler’s version of the hero’s journey, remains the most popular screen narrative form internationally, which problematically invites assumptions of universality (Hambly Citation2021). Vogler adapted his hero’s journey paradigm from Campbell’s mythic studies and Jungian depth psychology (Jacey Citation2010a; Vogler Citation2007) and Syd Field (Citation1979)’s Aristotelian three-act structure (Hambly Citation2021). Scholarly adaptations for gender difference typically look to Jungian feminism (Murdock Citation1990; Pinkola Estes Citation1992) and/or Jungian archetypes (Schmidt Citation2011), wherein only binary notions of gender fit the metaphors. It follows then that heteronormative life narratives underpin a paradigm that Vogler insists is ‘universal and timeless, and its workings can be found in every culture on earth’ (Citation2007, xix).

As gaming scholar Hanna Brady has written, ‘The dominant and common variants aren’t bad stories, but their overwhelming signal strength homogenizes our frame for the world and lies to us by saying there is a right story instead of infinite stories’ (Citation2017, 65). Queer theory, which already questions ‘the careful social scripts that usher even the most queer among us through major markers of individual development and into normativity’ (Dinshaw et al. [Halberstam] Citation2007, 182), offers another lens for examining and critiquing the hero’s journey’s claims to universality, and resisting the homogenisation of our ‘frame’. As this article has discussed, linear event-centred, goal-oriented, transformative structures are far from universal and, as evidenced by the scholarship, antithetical to queer temporalities.

It is important to reiterate, before concluding, that critiques of linearity are not unique to queer theory. What is more, the arguments of this article do not speak for every queer school of thought and certainly not queer communities at large, remembering that ‘asynchrony, multitemporality, and nonlinearity [are not always] automatically in the service of queer political projects and aspirations’ (Dinshaw et al [Jagose] Citation2007, 191).

However, queer temporalities offer approaches to unravelling the hero’s journey in the same way Halberstam – from the anti-social/anti-relational standpoint – seeks to ‘unravel precisely those claims made on the universal from and on behalf of white male subjects’ (Citation2005, 17). Queer storytelling might mean rejecting the calcified templates. It might mean permanently refusing the call.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stayci Taylor

Stayci Taylor is Senior Lecturer in the School of Media and Communication at RMIT. Since completing her PhD by project (screenplay), winning the RMIT prize for research excellence in her category, she has published traditional and non-traditional outputs (creative works) in journals such as Journal of Screenwriting, New Writing, TEXT, Celebrity Studies, Creative Industries Journal and Studies in Australasian Cinema. In 2022 she was named the national leader in her field (film) in The Australian research awards. She is the co-editor of the books A-Z of Creative Writing Methods (Bloomsbury 2022), TV Transformations and Female Transgression: From Prisoner Cell Block H to Wentworth (Peter Lang 2022), The Palgrave Handbook of Script Development (Palgrave Macmillan 2021) and Script Development: Critical Approaches, Creative Practices, International Perspectives (Palgrave Macmillan 2021). Stayci brings to her research a background in writing for television in New Zealand and Australia.

Notes

1 Halberstam Citation2012, 208.

2 Le Guin Citation2019, 33.

3 Ahmed Citation2006, 177.

4 It is important to note that this is also part of the ongoing homage to James Joyces’ Ulysses.

5 Of whom this author is one.

6 The hero’s journey was almost certainly not deployed either, as it rarely (if ever) is for television. For a compelling explanation, see Mullins (Citation2021, 17).

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Aronson, Linda. 2010. Screenwriting Updated: New and Conventional Ways of Writing for the Screen. Crow’s Nest: Allen & Unwin.

- Bechdel, Alison. 2006. Fun Home: A Queer Tragicomic. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Bechdel, Alison. 2022. “The Hauser Forum | Alison Bechdel on ‘The Psychochronology of Everyday Life: Time in Graphic Memoir’” YouTube. February 19. Video, 1:30:47. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8SWfqf_76Z4&t=13s.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Black, Angie. 2015. “The First Provocation.” Sightlines: Filmmaking in the Academy Journal 3. https://www.aspera.org.au/the-first-provocation.

- Black, Angie. 2019. “Capturing the Moment: An Investigation into the Process of Capturing Performance on Film and The Five Provocations: A Feature Film.” PhD diss., La Trobe University. https://search.lib.latrobe.edu.au/permalink/f/ns71rj/opalthesesarticle/21859176

- Bond Stockton, Kathryn. 2009. The Queer Child; Or, Growing Sideways in the Twentieth Century. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Brady, Hanna. 2017. “Building a Queer Mythology.” In Queer Game Studies, edited by Bonnie Ruberg, and Adrienne Shaw, 63–68. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Brokeback Mountain. 2005. Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana (wrs.), Ang Lee (dir.), USA: Focus Features and River Rock Entertainment.

- Bros. 2022. Billy Eichner and Nicholas Stoller (wrs.), Nicholas Stoller (dir.), USA: Universal Pictures.

- Bussey-Chamberlain, Prudence. 2021. “‘Every lover is a destroyer’: queer abuse and experimental memoir in Melissa Febos’ Abandon Me and Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House.” Prose Studies 42 (3): 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/01440357.2022.2144081

- Campbell, Joseph. 1949. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York: Pantheon.

- Campbell, Marion May, Lawrence Lacambra Ypil, Francesca Rendle-Short, Deborah Wardle, Ames Hawkins, Quinn Eades, Stayci Taylor, et al. 2023. “Queering.” In A-Z of Creative Writing Methods, edited by Deborah Wardle, Julienne van Loon, Stayci Taylor, Francesca Rendle-Short, Peta Murray, and David Carlin, 141–143. London: Bloomsbury.

- Carriger, Gail. 2020. The Heroine's Journey: For Writers, Readers, and Fans of Pop Culture. San Francisco: Gail Carriger LLC.

- Clark, Naomi. 2017. “What Is Queerness in Games, Anyway?” In Queer Game Studies, edited by Bonnie Ruberg, and Adrienne Shaw, 3–14. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Cleary, Stephen. 2020. “Writing ‘Passive’ Protagonists and Melodrama,” Draft Zero: working out what make screenplays work, 30 April, Accessed 28 February 2021. http://draft-zero.com/2020/dz-67/.

- Dancyger, Ken, and Jeff Rush. 2013. Alternative Scriptwriting: Beyond the Hollywood Formula. New York: Focal Press.

- Dinshaw, Caroline, Lee Edelman, Roderick A. Ferguson, Carla Freccero, Elizabeth Freeman, Jack Halberstam, Annamarie Jagose, et al. 2007. “Theorizing Queer Temporalities: a roundtable discussion.” GLQ 13 (2-3): 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2006-030

- Euphoria 2019-. Sam Levinson (cr.), USA: HBO.

- Field, Syd. 1979. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. New York: Dell Trade Paperbacks.

- Fox, Meghan C. 2019. “‘Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: Queer Futurity and the Metamodernist Memoir.’.” Modern Fiction Studies 65 (3): 511–537. https://doi.org/10.1353/mfs.2019.0032

- Freeman, Elizabeth. 2010. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Gadsby, Hannah. 2022. Ten Steps to Nanette: A Memoir Situation. Crow’s Nest: Allen & Unwin.

- Ghostbusters. 1984. Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis (wrs.), Ivan Reitman (dir.), USA: Columbia–Delphi Productions.

- Ghostbusters. 2016. Katie Dippold and Paul Feig (wrs.), Paul Feig (dir.), USA: Columbia Pictures.

- Halberstam, Jack. 2005. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: New York University Press.

- Halberstam, Jack. 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Halberstam, Jack. 2012. Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender, and the End of Normal. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Hambly, Glenda. 2020. “‘The Not So Universal Hero’s Journey.” Journal of Screenwriting 12 (2): 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1386/josc_00056_1

- Hambly, Glenda. 2021. “Cultural Difference in Script Development: The Australian Example.” In Script Development: critical approaches, creative practices, international perspectives, edited by Craig Batty, and Stayci Taylor, 69–82. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hayes, Britt. 2016. ‘“Ghostbusters” haters are spamming IMDb with low ratings’, ScreenCrush, 11 July, accessed 1 October 2022. https://screencrush.com/ghostbusters-imdb-what-the/.

- Jacey, Helen. 2010a. “‘The Hero and Heroine’s Journey and the Writing of Loy’.” Journal of Screenwriting 1 (2): 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.1.2.309/1

- Jacey, Helen. 2010b. The Woman in the Story: Writing Memorable Female Characters. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions.

- Jennings, Pamela. 1996. “Narrative Structures for New Media: Towards a New Definition.” Leonardo 29 (5): 345–350. https://doi.org/10.2307/1576398

- Kennedy, Tammie M. 2014. “Sustaining White Homonormativity: The Kids are All Right as Public Pedagogy.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 18 (2): 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2014.849162

- The Kids Are All Right. 2010. Lisa Cholodenko and Stuart Blumberg (wrs.), Lisa Cholodenko (dir.), USA: Focus Features and Gilbert Films.

- Koenitz, Hartmut, Andrea Di Pastena, Dennis Jansen, Brian de Lint, and Amanda Moss. 2018. “The Myth of ‘Universal’ Narrative Models: Expanding the Design Space of Narrative Structures for Interactive Digital Narratives.” In Interactive Storytelling: 11th International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2018 Dublin, Ireland, December 5–8, 2018, Proceedings, edited by Rebecca Rouse, Hartmut Koenitz, and Mads Haahr, 107–120. Cham: Springer.

- Le Guin, Ursula K. 2019. The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. London: Ignota.

- Loveless, Natalie. 2019. How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Love, Simon. 2018. Elizabeth Berger and Isaac Aptaker (wrs.), Greg Berlanti (dir.), USA: Fox 2000 Pictures, New Leaf Literary & Media, Temple Hill Entertainment and Twisted Media.

- Machado, Carmen Maria. 2019. In the Dream House. London: Serpent’s Tail.

- Macintosh, Paige. 2022. “Transgressive TV: Euphoria, HBO, and a New Trans Aesthetic.” Global Storytelling: Journal of Digital and Moving Images 2 (1): 13–38.

- Maras, Steven. 2017. “Towards a Critique of Universalism in Screenwriting Criticism.” Journal of Screenwriting 8 (2): 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.8.2.177_1

- McCann, Hannah, and Whitney Monaghan. 2020. Queer Theory Now: From Foundations to Futures. London: Bloomsbury.

- Mccollum, Victoria, and Kevin Gaffney. 2021. “Screen Production Research: (Queer) Short Filmmaking as a Mode of Enquiry.” Short Film Studies 11 (2): 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1386/sfs_00059_1

- Mendelsohn, Daniel. 2006. “An Affair to Remember”, New York Review of Books, 23 February.

- Menon, Radhika. 2022. “Everything to Know about the Turning Red Controversy,” Bustle, 19 March, Accessed 1 October 2022, https://www.bustle.com/entertainment/pixar-turning-red-period-asian-culture-controversy-explained-cast-response.

- Miller, D. A. 2007. “On the Universality of Brokeback.” Film Quarterly 60 (3): 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2007.60.3.50

- Milligan, Christina. 2022. “The Writing of the Indigenous Feature Film Waru.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Script Development, edited by Stayci Taylor, and Craig Batty, 175–184. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Monaghan, Whitney. 2016. Queer Girls, Temporality and Screen Media: Not ‘Just a Phase’. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mullins, Anthony. 2021. Beyond the Hero’s Journey: A Screenwriting Guide for When You've Got a Different Story to Tell. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press.

- Murdock, Maureen. 1990. The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness. Boston: Shambhala.

- Page, Elliot. 2023. Page Boy. London: Penguin Random House.

- ‘Pilot: Part 2’. 2004. Irene Chaiken, Kathy Greenberg and Michele Abbots (wrs.), Rose Troche (dir.), The L Word, Season 1 Episode 2 (24 January, USA: Showtime).

- Pinkola Estes, Clarissa. 1992. Women Who Run with the Wolves: Contacting the Power of the Wild Woman. London: Rider.

- Rosario, Ruben. 2022. “Delightful ‘Turning Red’ Gives Fuzzy Makeover to Pixar Formula,” miamiartzine, 10 March, Accessed 1 October 2022, https://www.miamiartzine.com/Features.php?op=Article_16470050776133.

- Ruberg, Bonnie. 2020. The Queer Games Avant-Garde: How LGBTQ Game Makers are Reimagining the Medium of Video Games. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. 2011. 45 Master Characters: Mythic Models for Creating Original Characters. Cincinnati: F+W Media.

- Taylor, Stayci, Angie Black, Patrick Kelly, and Kim Munro. 2023. “Manifesto as Method for a Queer Screen Production Practice.” Studies in Australasian Cinema 17 (1-2): 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/17503175.2023.2224618

- Turning Red. 2022. Domee Shi and Julia Cho (wrs.), Domee Shi (dir.), USA: Pixar Animation Studios and Walt Disney Pictures.

- Vogler, Christopher. 2007. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 3rd ed. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions.

- Walters, Suzanna Danuta. 2012. “The Kids Are All Right but the Lesbians Aren’t: Queer Kinship in US Culture.” Sexualities 15 (8): 917–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460712459311

- Windhauser, Brad. 2023. “Queer coming of age: Recognizing the Genre’s Classic Cluster.” Queer Studies in Media & Popular Culture 8 (2): 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1386/qsmpc_00098_1