ABSTRACT

The expansion of cyberperformance has been noticeable through the growing access and effective development of digital technologies for the performing arts and reinforced within the pandemic scenario of the last two years. For educational institutions, namely higher education, and especially in the creative sector, creativity has become the keyword for the adaptation to a new reality that has led teachers and artists to experiment with models for online performance for their capacity to reinvent methodologies and forms of interaction. This text presents the first results of the research project CyPet. Based on these first results, it is intended to map the panorama of the performing arts both in the context of online/hybrid teaching and practice and consequently, as the outcome, to propose a new pedagogical model for both higher education and the artistic post-pandemic reality.

1. Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic led to profound changes in teaching. These changes affected education at all levels and particularly the teaching of performing arts. The present study is part of the CyPeT research project, funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) in Portugal. The aim of the project is to analyse the problems and the strategies developed for the teaching of performing arts during confinement and propose a new pedagogical model. To that end, we present a diagnosis of the higher education reality based on the analysis of the results of the questionnaires applied to Portuguese Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and, for the artistic practices, based on the analysis of results from semi-structured interviews with artists who, during the period of confinement, used new strategies for the presentation and dissemination of their work through cyberperformance.

These constitute the first outputs from the research project. An overall perspective, ‘(…) if art is the field of the sensitive, its history is that of the artists’ resilience’ (Isaacsson Citation2021, 5). That is why the performing arts resisted in times of confinement by opening doors in cyberspace to find new territories for their social existence, expanding the practice to the digital and continuously nourishing society with poetic and sensitive material. In this sense, cyberperformance expands artistic performative practices and extends its scope to higher education as a creative territory.

In addition to the results obtained through the questionnaires and interviews, this article presents some concepts related to cyberperformance and online teaching, considered essential for the construction, at a later stage, of a pedagogical model in this domain ().

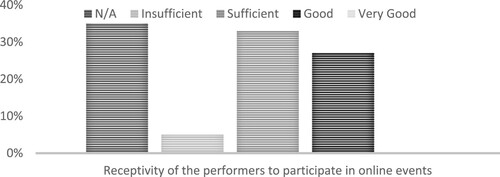

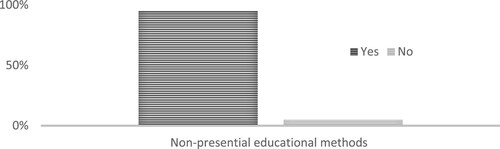

Figure 1. Non-presential educational methods in the Portuguese higher education institutions during the pandemic. Source: Authors.

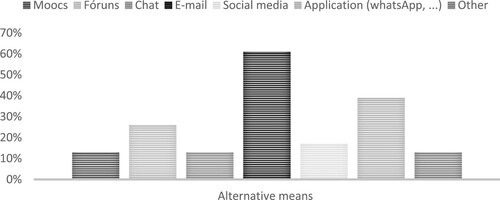

Figure 4. Alternative means used by teachers to share content and interact with students. Source: Authors.

In the analysis of the socio-psychological effects of confinement periods, it is concluded that reactivity, adaptability, and above all creativity played a predominant role in resisting the covid-19 pandemic (Elisondo Citation2022). The pandemic context massified the experience of distance communication, bringing to new light performative practices that, until then, have been predominantly experimental. Our digital tools, most of which are inside a single machine, the computer, are often democratically accessible instead of specialized, learned by individual experience rather than through the secret knowledge of a Master. Computers came to change the way we think about the world and the way we communicate with each other. As such, the artistic creative processes also changed. Artists no longer depend on a formal or informal structure (such as the fine arts college or the studio of the Master) for acquiring the needed skills and tools to develop their projects. Instead, digital artists rely on the capacity to constantly update their skills and improve their literacy for digital production. Therefore, creativity is deeply inscribed in the unique ways democratic and widely distributed tools are thought, developed to be applied or appropriated, to artistic conceptualization and production. The role of formal and informal education is less about transmitting settled and defined knowledge but instead stimulating self-reflection, autonomous development, and curiosity. This is transversal to installations, Internet artworks, and performances, to affect the arts in general which, as Bourriaud states, are in a state of constant cultural postproduction (Citation2006). Postproduction, as a term, relates to the audiovisual production process of editing existent material, both visual, audio, and textual. Bourriaud borrows the term ‘postproduction’ from video editing to describe artworks based on previous artworks which implies their re-use combined with other cultural elements at large. Postproduction lays grounds on sharing rather than on authorship and, as stated by the author, digital developments, data storage in particular, affect and are affected by artistic movements.

Such is the case with cyberperformance. The term cyberformance was coined by Helen Varley Jamieson. It was first used in 2000 and reinforced with the publication of her thesis in 2008. At the time, the artist conceptualized cyberformance as the experience of a performance with remote performers grouped together in real-time through Internet applications such as chatrooms. For Gomes (Citation2013, 132) cyberformance ‘is a live performance that is developed with digital technologies using the Internet, often in virtual worlds’. Both Jamieson (Citation2008) and Gomes (Citation2013) use the term for artistic performances that take place in virtual worlds. In this investigation, we chose to use the term ‘cyberperformance’ and, in its understanding, it is in line with the vision of Duarte (Citation2016) and Najima (Citation2020) who emphasize that cyberperformance is: (i) unfinished, since its existence requires the updating and the participation of the spectator; (ii) happens live, as artists and audience share time; (iii) located in cyberspace, and can happen unrestrictedly on several virtual platforms; (iv) geographically distributed because it happens simultaneously in physical and virtual places; furthermore, it has an attitude and is digital. Sullivan (Citation2020, 198) states, however, that online streaming questions the traditional understandings of performance even more from the need to be in real-time ‘live’, as the root of all performance.

The link between cyberperformance, performing arts and online teaching is the thread that guides this research project by analysing how online teaching of the performing arts was delivered in Portuguese Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), during the periods of confinements imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic and mandatory social isolation in 2020–2021.

With the suspension of face-to-face teaching activities, the need for teachers and students to migrate to the online reality arose, along with the need to transfer and adapt methodologies and pedagogical practices of face-to-face learning, to what was called ‘emergency remote teaching’ (Moreira, Henriques, and Barros Citation2020, 352). It is worth noting that remote teaching is a broader category, according to Woolway, Badillo, and Lemov (Citation2021, 127), ‘it includes online teaching, but also other tools that you can use when you are away from the student: email, texts and phone calls’. During the period of emergency, remote teaching was an important phase in which face-to-face was replaced, by the teacher in the role of the ‘YouTuber’ using prerecording video in the classes, with videoconferencing systems, and the creation of groups on WhatsApp and other social networks. Between periods of confinement, some educational institutions chose to use mixed methodologies or ‘hybrid teaching’, which alternates face-to-face and online classes. According to Bidarra (Citation2022), blended learning is a teaching methodology that uses digital technologies, as well as online sessions as strategies to support conventional teaching, trying to enhance learning through two modalities: face-to-face and online. The practice of online teaching revealed itself difficult as a pedagogical alternative to teaching in the physical space of the classroom especially in the performing arts, which, by their essence, have always made use of face-to-face interaction. The need to adapt and find creative solutions, led us, as a research group, to the study of cyberperformance, as a mean to enrich and inform pedagogical practices in the field of the performing arts. It was in this scenario that the exploratory research project CyPeT was created, aiming to explore the theory and practice of cyberperformance from the creative, performative, and communicational angles, towards the development of a new pedagogical model which allowed the inclusion of cyberperformance in Higher Education curricula.

2. The online teaching of the performing arts as a creativity challenge

The response to online teaching imposed during the confinement periods, in the years 2020–2021, faced many challenges. The ‘new normal’, as this phase became known, demanded from teachers and artists the ability to ‘reinvent themselves’, to adapt, and to be creative in even more precarious conditions than usual (Brönstrup Citation2020). In the Portuguese context, studies in this period are still scarce. Most publications focus on how institutions have been adapting to remote teaching, with emphasis on the required technological means, teaching strategies, and interaction with students (Flores et al. Citation2021). Even scarcer is research linked to online teaching of the performing arts. Flores and Gago (Citation2020), Flores et al. (Citation2021), and Marques (Citation2021) present generalist research about online teaching during confinement, and specific to performance, Gomes (Citation2021) and Cunha and Maia (Citation2021) address online teaching in the performing arts.

All the investigations mentioned above revealed problems and challenges associated with the abrupt transition from face-to-face teaching to emergency remote teaching. Among the main difficulties identified by the authors are the conditions for distance learning, namely network problems, the lack of adequate equipment, and the diversity (and inequality) in access to technological resources on the part of students and teachers (Judd et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020 apud Flores et al. Citation2021). Further ahead, in the next section, we deepen this subject in the analysis of questionnaires carried out within Portuguese HEIs.

Despite technological difficulties, creativity made possible good practices and successful experiences. Creativity is inherent to human beings, making possible individual discoveries and reinvention in the most difficult circumstances. It is present in our society in various instances, enabling scientific, cultural, political, economic, and educational advances over time. In the scope of the university, it could not be different, as the creative processes are important for structuring and thinking the didactic structure of the classroom, nonetheless, ‘it is observed that the world has changed quickly, however, many didactic formats used in the classroom remain the same’ (Tussi, Neves, and Fásvero Citation2022, 740). The emergence of distance communication has highlighted a pressing issue that demands creative solutions: how to adapt artistic practices that traditionally require corporeality to a virtual space that dematerializes it? How can this creative adaptation be carried out by teachers without previous technological training? This question was even more pressing because the pandemic situation highlighted the current gap between a society that tends to disengage from traditional cultural media (theater, cinema, books) preferring digital content, and the teaching of artistic production through electronic devices.

By the time the transposition of the face-to-face class to the online was necessary, as mentioned by Resnick (Citation2022), it needed to go beyond the structure of the classroom and the way socially we think about it. Society, as a network, is diverse and complex. Creative education has the challenge of incite this dynamism, and by including collaboration, which boosts the creativity, it can change the classes, projects, and other activities. In this sense, the study of cyberperformance meets this creative gap in the teaching of online performing arts.

Cyberperformance, as a form of live artistic expression, unfolds on digital platforms, virtual environments, and virtual worlds. As a mediated, intermedial, hybrid, collaborative artistic practice, it is of a socially intervening nature (Gomes Citation2015; Gomes Citation2017; Jamieson Citation2008). Cyberperformance challenges the Cartesian division between mind and body and reexamines the concept of simulated reality by asserting that virtual reality is just as real and consequential as the physical world. Cyberperformance’s genealogy intertwines with performance and net art. As an online practice, has an inclination towards being processual and open-ended (Duarte Citation2016; Gomes Citation2017; Najima Citation2020). Art developed with and for digital media presupposes ongoing and independent learning that respond to the interest in creatively exploring and critically reflecting upon new technologies. From here, new initiatives emerge that evoke engagement, and personalization through the articulation of content and considering its potential with network communities and the renewed concepts of participation, collaboration, autonomous learning skills, and multidirectional and creative dynamics.

In discussing the challenges associated with digital performance, Julia Varley, an actress and director of Odin Teatret, highlights the effort required to engage audiences through digital platforms. She draws attention to the perceived difference between live presence, where the actors’ risks are palpable, and the digital realm, which may seem mundane or lacking in intensity due to issues like wi-fi disruptions or glitchy backgrounds. Varley's insights resonate with the ethos of cyberformance, particularly as exemplified by Helen Varley Jamieson (Citation2008, 38). In cyberformance, the acknowledgment of technology and its flaws is part of the performance. This approach, evident in works like ‘Flanker Origami,’ deliberately exposes the mechanisms and glitches, creating a fluid relationship with technology. Such a stance contrasts with high-tech perfectionism, emphasizing the authenticity and visibility of the risks involved in the digital creative process (Mastrominico, Citation2022). Cyberperformance remains a pertinent and contemporary term that spans a rich evolutionary history, moving beyond its origins in Internet 1.0 virtual worlds like Second Life. It maintains a connection with a wide range of artistic traditions, encompassing elements of experimentation and innovation. The term is open and capable of embracing the spectrum of online practices, from avant-garde and experimental approaches to the more popular and widespread performances seen on platforms like TikTok. Its relevance is underscored by its recognition in recent scientific literature, where it continues to be actively discussed as it describes current practices in the evolving landscape of online artistic expressions.

For all its characteristics, cyberperformance has become a departing practice for the development of creative classes in the online context, precisely because of its connection between the existing dynamics in online performance and the digital platforms and social networks as privileged spaces for the development of a ‘pedagogy of connections’ (Santana and Moreira Citation2020, 208).

3. Method

Two different instruments were used to collect information about the strategies, difficulties, and limitations faced during the confinement period (fundamental information for the pedagogical model), these are:

A questionnaire: ‘Online teaching of performing arts in a context of confinement’ sent to all coordinators of performing arts courses at Portuguese higher education institutions (HEIs). From a total of fifty degrees, the corpus consisted of twenty-three participants (corresponding to a percentage above 46% of the population, which may reinforce the internal validation).

Six semi-structured interviews with artists who, during the confinement period, used new presentation and dissemination strategies for their performances.

3.1. Participants

All the coordinators of the first cycles of study in performing arts in Portuguese Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) were contacted to complete the questionnaire: ‘Online Teaching of the performing arts in a context of confinement’, of which twenty-three participated in the study.

To what concerns the semi-structured interviews, the corpus was defined by an intentional sampling since it was intended to hear artists and artistic groups. Six interviews were made. While the results of the questionnaires were subject to statistical treatment, the interviews were subject to content analysis according to a qualitative model (Bryman Citation2012).

3.2. Measures

Given the nature of the instruments of this study, it has been decided to combine quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

To collect data about the impact of the pandemic, the questionnaire included open-ended and closed-ended questions (Yes/no questions, Multiple choice questions, and Ranking questions) related to cyberperformance, creativity, and Higher Education. Since closed-ended questions have discrete responses, it was necessary to include into the research a quantitative analysis based on descriptive statistical techniques.

The descriptive, open-ended questions of the questionnaire and of the interviews were submitted to a content analysis (separately).

A guide of topics was created which included questions referring to the challenges that COVID-19 brought to creativity. This method of data treatment was based on Grounded theory.

Originating from the work of Strauss and Glaser (Citation1967), Grounded theory proposes a systematic and qualitative set of procedures used to generate an inductive theory based on the systematic analysis of data obtained in natural contexts (Charmaz Citation2014; Glaser and Strauss Citation1967).

3.3. Procedures and analysis

The data collection took place between April and July 2022. All participants gave formal consent to participate, and the research respected all ethical principles. Participation was voluntary and without incentives, and confidentiality was ensured as well as the right to access the study’s results. The open questions of the questionnaire and the interviews were codified separately.

The data was treated through open coding and categories were structured from the data collected. The categorization system was subject to triangulations based on the interpretations of different researchers that led to a single categorization system. The content analysis was done by identifying keywords and analysing the frequency of categories and terms used in the discourse.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the questionnaires applied to Portuguese higher education institutions

The questionnaire ‘Online Teaching of the performing arts in a context of confinement’ was sent from April to July 2022 to all coordinators of first cycles of study in the performing arts at Portuguese Higher Education Institutions (HEI) and anonymity and data protection were assured to all participants. From a total of fifty degrees, the corpus consisted of twenty-three participants.

The first set of questions outlined the profile of the respondents to identify their role in the process of transition to online teaching during confinement, and how they assessed their digital skills in terms of information processing, communication, content creation, security, and problem-solving. Then, they were asked about the difficulties found and the strategies adopted to overcome them.

Most respondents are the coordinators of the cycle of studies and half of them are also teachers. 63.5% were in the areas of music, 21% of theater, 7.75% of dance, and 7.75% of theater and dance, which does not necessarily mean that most courses in the areas of the performing arts are focused on music, but only that, in this questionnaire, the teachers in this area were the most predisposed to collaborate. As for the use of non-presential educational methods (occasionally or regularly), 95% of the Portuguese higher education institutions used these hybrid methods in 2020/2021:

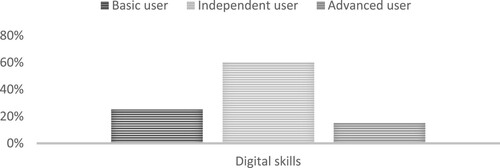

In terms of digital skills, according to the project DIGCOMP, five subcategories were considered: (1) Information Processing, (2) Communication, (3) Content Creation, (4) Security, and (5) Problem-Solving. In general, regarding all the digital skills involved in the answers, an average of 60%, of coordinators/teachers in the performing arts consider themselves Independent Users, that is, autonomous in the use of digital technologies. An average of 25% of respondents consider themselves Basic Users and only 15% self-assess themselves as Advanced Users:

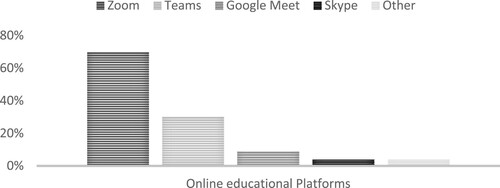

The first technologies that allowed the use of videoconferencing appeared in the 1970s through the lines of communication of telephone companies. For this, ISDN (Integrated Services Digital Network) and IP (Internet Protocol) lines were used, but still, signal quality was low. Later, broadband and satellite systems replaced telephone lines, but without the necessary stability for good transmission (Soares Citation2020). Currently, long-distance cabling and data centers distribute signal and storage data, and any digital device, such as a smartphone, tablet, or laptop, can be used as video collaboration system. Several platforms facilitate the interaction between students and teachers, many of which are free and easy to access. These platforms aim to reduce bureaucracy and distances and to connect people, among the most used and accessible, are Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet. With confinement, between 2020 and 2021, videoconferencing platforms became popular. Of the Portuguese HEIs with degrees in Performing Arts, 69.6% have used the Zoom platform, followed by 30% Microsoft Teams, and the remaining HEIs have used Google Meet, Skype, and others. It must be stressed that each respondent could choose more than one platform.

In addition to videoconferencing platforms, MOOCs, forums, e-mail, groups, and communities on social networks, applications such as WhatsApp, and others were used for teachers to share content and interact with students. Among these, the most used resource was e-mail with 60.9% of responses, followed by WhatsApp with 39%, and, in the third position, the forums. Often, these resources were used simultaneously.

The questionnaire was also constituted by a series of open-ended questions that provide an understanding of the concerns and difficulties found in teaching/learning in online environments.

Concerning the difficulties, the results indicate that ‘Image freezing’ and ‘delay’ were the biggest constraints. Especially in Music, respondents reported the ‘impossibility of acting simultaneously’. The sound quality in instrumental music classes was reported as being very low. Nuances of the physical and expressive qualities of the sound are lost.

In addition, network/wi-fi coverage problems have been also detected in specific geographic areas of the country. The dependence of teachers and students on personal equipment created inequalities and differences in quality and interferences in sound, creating the impossibility of interacting simultaneously. Students without computers could not process data in real-time (audio processing, for example). In dance, respondents emphasize the lack of music synchronization for all users (dancers), the inexistence of an appropriate space for exercising movements at home, the difficulty teachers had in visualizing all the students at the same time, and, consequently, the difficulty in providing feedback. Only 5% showed no difficulties at all.

Respondents state that technological difficulties stand out. One respondent describes how ‘the system did not allow a real image and sound, which limited the student's development.’ Others point out that even with ‘computer simulators, the results were below the desired level.’ For this reason, the respondent considers that the level of skills acquired by the students was compromised, and the assessment could not be evaluated in the same way as in the physical space. In the area of dance, constraints resulting from changes in perception of the body and its movement are described, making evident the need to find strategies and didactic resources that allow the effective transmission of the technique, the correct evaluation of the student’s performance, and the analysis of progression.

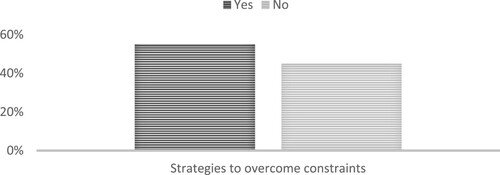

In theater, difficulties associated with the use of long shots stand out as well as the impossibility of using multiple shots to have a real perception of the exercises. The poor sound quality is presented as compromising both in terms of expressiveness and in terms of the evaluation of the work developed. According to Moreira, Henriques, and Barros (Citation2020, 361) ‘the teacher is a central element in this process, because to have elements for the evaluation of the different indicators considered, he needs actively to stimulate the discussion’. As a mediator, the teacher needs digital and metacommunication skills. Regarding the strategies to overcome the constraints reported in the questionnaires, 55% of respondents indicate that these have been developed:

When asked about which strategies and with what results, respondents mentioned:

- Creation of a website to host recordings made by students;

- Change in the focus of interaction;

- Adaptation of the exercises for the online context;

- Use of personal easily accessible material resources (e.g. props, filming spaces; online image search) because these are easily accessible;

- Delivery of video recordings of students’ performance to the teacher for feedback and evaluation;

- Reinforcement of the use of recording and conjugation of the synchronous with the asynchronous;

- Simulation of practices.

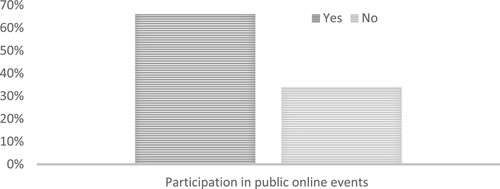

When asked if teachers participated in public online events related to the university (conferences, workshops), 66% of those questioned responded positively.

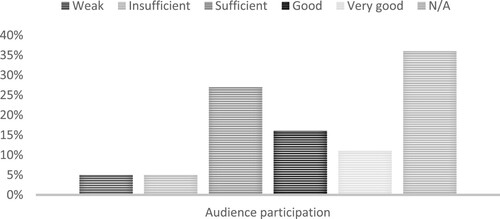

Regarding the receptivity of the performers to participate in online events, 33% of the respondents considered the receptivity sufficient, 27% good, 5% insufficient, and 35% of respondents did not answer this question:

Concerning public participation, 27% indicated that it was sufficient, 16% good, 11% very good, 5% weak, 5% insufficient, and 36% of the sample did not respond or evaluate:

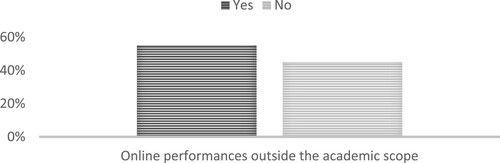

When asked if teachers have presented their work outside the academic context, 55% of the respondents answered affirmatively:

However, one of the respondents points out that at the performative level, the interaction was limited, as the fear of breaking the connection was at stake. Others reported that the interaction took place ‘through specific platforms (Jamulus)’ or highlight the ‘online concerts’, or even the ‘use of questionnaires/questionnaires’. To what concerns strategies, tools and methods learned for online teaching that will continue in use after the transition to education in the physical space, the following aspects were referred:

- Synchronous communication through video interaction;

- Use of recordings of the students’ performances for self-correction and subsequent discussion;

- Use of online platforms by students and teachers based abroad;

- Based on the responses obtained, several challenges were identified and will be considered in the design of the new pedagogical model:

- The acoustic quality of real-time;

- The possibility of creating the illusion of physical presence, as this has been the reason for its constant comparison with the online presence models;

- The absence of direct and physical visual contact between the teacher and the students;

- Synchrony and the possibility to interact in agogic and dynamic terms;

- The ‘delay’;

- The technical quality of the tools/resources available to students and teachers;

- The development of better and more advanced software for online performances.

In addition to the adaptation to existing digital media, teachers emphasize the need for improvements and the creation of new and specific software and telecommunication platforms. It is also important to mention that the student ‘learns actively, from the context in which he finds himself – face-to-face or virtual – when it is significant, relevant’ (Silva Citation2020, 251), regardless of the idealized technological scenario and its flaws. We learn by facing complex challenges that expand our skills, our perception, and knowledge, ‘[…] not only to adapt to reality, but above all, to transform, to intervene in it, recreating it’ (Freire Citation1996, 163).

4.2. Results of interviews carried out with artists and artistic groups

The interviews with artists intended to obtain detailed information about their professional experience developed in the context of cyberperformance during confinement. Thus, six interviews took place between May 31 and July 31, 2022. All respondents consented to participate in the study and to the use of the information collected by the research team responsible for the CyPet project. In the artistic context, and contrary to what happened in most of the HEIs considered, there were some experiences prior to the pandemic which in some way facilitated the transition from the physical space to the virtual space. Furthermore, it is important to mention that:

Many of the strategies adopted in online performances resulted from other previous experiences that served as inspiration;

The cases with a more positive balance are those where the entire performance was planned since the beginning for an online audience, aware that the change in the mode of presentation requires profound changes in the creative process itself;

Several platforms were used to present online performances, such is the case with Zoom, Teams, Google Meet, Skype, MOOCs, forums, chats, email, or groups on social networks, such as WhatsApp and Facebook;

Several artists recognize advantages in using online models and (even favoring hybrid models) regarding the possibility of:

- Engage in a dialogue with a wider and more diversified public (both in terms of geography, age, and economic conditions);

- Play with image manipulation creating performances that combine fiction and reality, virtual and physical spaces;

- Design new opportunities to expand cinematographic and video art languages;

- Provide greater visibility to the work developed due to the ease of dissemination;

- Convert spectators into active audiences;

Despite the existence of advantages, there are also new requirements regarding the need for continuous training (to reduce technical constraints, but also to promote greater interactivity with the public) and the need for investment in the acquisition of new and better equipment;

In addition, technical problems include delay, signal interruption, and the internet speed;

It should be noted that, even now, with the overcome of major constraints raised from the pandemic, some of the interviewees continue to perform in virtual spaces, although preferentially opting for a mixed format.

5. Discussion and interpretation of results obtained

The results obtained also allow us to conclude that the use of cyberperformance triggered new processes in the creation of performance in a broader sense.

Vieira (Citation2021), inspired by Costa and Viseu (Citation2008), presents a model particularly well suited to the teaching of cyberperformance that favors the curricular integration of ICT, the T@R model: Training – Action – Reflection. In this model, Training triggers the work of teachers/performers as an Action with students/audience by creating concrete learning situations with available technologies within their respective projects. Here we integrate research and training to rethink the creative processes specific to cyberperformance. In a cyclical model, the action results in performance, and the reflection upon it, or its revision, feeds the analysis of the process. Among the observations made in the interviews, there is, for instance, greater awareness of the mediation of the camera and its effects on the construction of meaning. One of the interviewees says: ‘When we see something through a screen, whether live or through a recording, we are seeing the producer's gaze, it is not our gaze’. The camera and the cameraman while mediating the gaze, become producers of meaning and actively participate in the construction of the work. Perhaps for this reason, there are testimonials that point to a concern about the essence of this new genre, as some directors wonder if the changes are not bringing this format too close to the commercial cinema or content aimed at entertainment.

One of the most differentiating aspects of cyberperformance, as the interviews pointed out, is the spectator, who is invited to abandon his passive role and participate actively. One of the most frequent criticisms regarding the behavior of online audiences is the fact that viewers turn off the camera (often to do other activities while at the performance), especially when they realize that it is required their active participation, to play the role of performers instead of remaining passive. The Internet imposes a redefinition of the spectator, by promoting the indistinct role between actors and spectators, while simultaneously diluting the distinction between fiction and reality. If we consider the participation outside the 2D universe and reflect on the interaction in a purely virtual world, as is the case of Second Life, this fictionalization of the spectator/actor is even reinforced imposing an absolute revision of the concept of actor/spectator living together on the same digital stage.

At the same time, perhaps one of the most promising aspects of online performance is the fact that it covers all communicational systems. The Internet is a medium in which the user/audience/viewer/spectator can enter, interact, choose paths, observe processes, and multiply visions and points of view, in a state of submersion close to consciousness. The spectator, in cyberspace, feels as if in a kaleidoscopic dimension where all the voices: places, memory, imagination, and desire; are summoned as texts, images, and sounds; and where space is inhabited with others from distant places and cultures, real or fictional. In his work Society of the Spectacle (Citation2005), Philosopher Guy Debord describes society as ‘fundamentally spectacularist’ (Citation2005, 10). Sustained on the role of the individual as passive consumer to whom appearences stands for reality. This leads to the premise that performance, by its nature, creates a distance from this ‘model of life’ (Citation2005, 8) that is the spectacle within which the individual is a passive spectator. In cyberperformance, the spectator is compelled to move away from it by abandoning this role to become part of the performance. Without the participation of its public, the performance does not exist as such. The audience react in physical copresence with the performers. Connected through the technology that allows access to the performance (computer, mobile phone), and during the performance, the audience can choose to be seen or not, to be heard or not, to assume or not a participative role but these are decisions to be made rather than a scripted procedure to be followed. The power to act cannot, however, remain on the surface. The capacity for action and interaction necessitates a level of awareness and preparation to ensure that the exchange between the actor and spectator transcends mere simulation or enactment.

In essence, the emergence of this novel spectator requires appropriate education. To encapsulate this idea, Gomes (Citation2021) draws on the insights of Sullivan (Citation2020), underscoring that online performances hold the potential to explore innovative modes of audience interaction. With social networks, artists, groups, and associations can forge pathways to foster online engagements, thereby immersing audiences in an increasingly digital experience.

6. Conclusions

The growing need felt by the performing arts to turn to digital environments, uploading recordings of theater plays, uploading artworks, live streaming of home rehearsals, or creating performances specifically for the Internet, disrupted established practices, and brought new creative challenges to artists and groups of artists. In the higher education context, and despite previous advances in e-learning and blended learning, the immediate response of most institutions during the pandemic was to translate their classes/methodologies to videoconferencing platforms, such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, or Google Meet.

The present study is part of a broader project that aims to develop a new pedagogical model that can be integrated into Higher Education curricula. Aware that the definition of this model would benefit from the crossing of experiences between the teaching and artistic world, it was chosen, from a methodological point of view, to use questionnaires (applied to the academy context) and interviews (carried out with artists and performers).

The results point out, on the one hand, the fact that teaching online performance has constituted a phenomenon arising from an extraordinary circumstance and with immediate consequences. In this context, it doesn’t have, at this point, associated critical thinking. It is, so far, a last-resource solution. On the other hand, regarding the artistic context, different experiences were identified, showing that the results depend mainly on the strategy adopted since the change from the physical space to the online or hybrid space requires profound changes in the creative process itself and does not benefit from a simple transposition. It also requires education at the level of audiences as their role in the performance changed from passive presence to active participation.

Finally, it should be noted that, despite the constraints, some elements can and should be seen as positive, opening new opportunities in performative and teaching practices for the future ahead.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ana Carvalho

Ana Carvalho is Assistant Professor and BA Art Multimedia coordinator at University of Maia. PhD in Information and Communication in Digital Platforms from the University of Porto and Master in Interactive Art and Design from Falmouth University. Her scientific activity has as central themes the intersections between image and sound, in its articulation with different media, from performance to video, extending to digital arts. She is currently a member of CIAC (Center for Research in Arts and Communication, University of Algarve).

Célia Vieira

Célia Vieira is an associate professor at the University of Maia (Porto, Portugal) and a researcher at CIAC (Centre for Research in Art and Communication). She specialised in the field of Comparative Literature, with her thesis Theory of the Iberian naturalist novel and its French influence (Faculty of Letters of Porto), and has numerous publications in the fields of comparative literature (Portuguese, French and Spanish), digital humanities and intermedial studies, including Inter Media. Littérature, Cinéma, Intermédialité (org) (Éditions L Harmattan 2011) or Dictionnaire des Naturalismes (collaboration) (Honoré Champion ed. 2017). She is currently a member of the team of the international project “Rémanence des naturalismes/vérismes de l’Europe néolatine du XIXe siècle dans les cultures artistiques contemporaines (XXe / XXIe)” (PSL / Sorbonne Nouvelle).

Inês Guerra Santos

Inês Guerra Santos, has an academic and professional path dedicated to Social Sciences, with an emphasis on Socio-cultural Communication. PhD from the University of Salamanca. Since 1997, she had the privilege of contributing to academia as a university lecturer. She now assumes the position of Associate Professor at the Maia University. In addition, she has held various leadership roles over the years: President of an Organic Unit at the Maia University, Coordinator of the Degree in Public Relations since 2012, and responsible for the International Office of the same University for ten years. Throughout her career, she has published several articles in specialized journals, book chapters and organized academic events. She has participated in and led various research projects, including the participation, as a Researcher, in the CYPet Project, funded by FCT.

Rosimária Rocha

Rosimária Rocha is an invited assistant teacher at the University of Maia; researcher at CIAC- (Research Center for Art and Communication)- University of Algarve, works on the CyPeT Project – “Development of a new pedagogical model for teaching cyberperformance in higher education; PhD in Digital Media-Art by Open University / University of Algarve(2022); Master in Arts -Federal University of Bahia; Postgraduate in Integrated Management – Faculties of Northern Mato Verde; Degree in Music-University Center of Southern Minas; Graduated in Pedagogy- State University of Montes Claros. She works in the area(s) of Arts and Humanities with an emphasis on Arts/Music and Technology.

References

- Bidarra, J. 2022. “Problemas e Perspetivas do Ensino Híbrido.” Paper presented at the Seminário Tecnologias no Ensino/ Formação- Nova Era “Novos contextos: Distância e Proximidade”. Realizado em abril de 2022. https://pt.slideshare.net/bidarra/problemas-e-perspetivas-do-ensino-hibrido.

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. 2006. Postproduction. Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World. Massachussets: The MIT Press.

- Brönstrup, C. 2020. “Teatro virtual e nostalgia da presença.” In Pesquisa em Artes Cênicas em Tempos Distópicos: rupturas, distanciamentos e proximidades [livro eletrônico], edited by Patrícia Fagundes, Mônica Fagundes Dantas, and Andréa Moraes. Porto Alegre: UFRGS.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. New York, NY: Oxford.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Costa, F., and S. Viseu. 2008. “Formação – Acção – Reflexão: Um modelo de preparação de professores para a integração curricular das TIC.” In Costa & Viseu. As TIC na Educação em Portugal. Concepções e práticas, edited by Fernando Costa, Helena Peralta, and Sofia Viseu, 238–258. Lisboa: Porto Editora.

- Cunha, M. M., and S. V. Maia. 2021. “Dar voz as artes: experiências artísticas em tempos de pandemia.” In Emoções, Artes e Intervenção- Perspetivas Multidiciplinares, 241–252. Coimbra: Almedina. http://hdl.handle.net/10316/97588.

- Debord, G. 2005. Society of the Spectacle. London: Rebel Press.

- Duarte, S. 2016. “Ciberformance, Second Life e ‘Synthetic Performances’.” Ouvirouver: Uberlândia 12 (2): 448–460. https://doi.org/10.14393/OUV19-v12n2a2016-15.

- Elisondo, Romina Cecilia. 2022. “Creative Processes and Emotions in Covid-19 Pandemic.” Creativity studies 15 (2): 389–405. https://doi.org/10.3846/cs.2022.14264. ISSN 2345-0479 / eISSN 2345-0487.

- Flores, M. A., and M. Gago. 2020. “Teacher Education in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic in Portugal: National, Institutional and Pedagogical Responses.” Journal of Education for Teaching 46 (4): 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1799709.

- Flores, M., E. Machado, P; Alves, and D. Vieira. 2021. “Ensinar em tempos de COVID-19: um estudo com professores dos ensinos básico e secundário em Portugal.” Revista Portuguesa de Educação 34 (1): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.21814/rpe.21108.

- Freire, P. 1996 (2006). Pedagogia da autonomia. São Paulo: Paz e terra.

- Glaser, B., and A. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Gomes, C. 2013. Ciberformance: A performance em ambientes e mundos virtuais. Tese de Doutoramento em Ciências da Comunicação. Lisboa: Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

- Gomes, Clara. 2015. Ciberformance: a performance em ambientes e mundos virtuais. Lisboa, Portugal: LEYA.

- Gomes, C. 2017. “Ciberformance: performance e netactivismo.” In Netactivismo, edited by Isabel Babo, José Bragança de Miranda, and Manuel José Damásio e Massimo Di Felice, 308–324. Lisboa: Edições Universitárias Lusófonas. Colecção: Imagens, Sons, Máquinas e Pensamento.

- Gomes, I. M. S. 2021. “A digitalização do teatro em Portugal e a pandemia de COVID-19.” In Tese de mestrado em Comunicação, Cultura e Tecnologias da Informação, 1–55. Lisboa: Instituto Universitário de Lisboa.

- Isaacsson, M. 2021. “Teatro e tecnologias de presença à distância: invenções, mutações e dinâmicas.” Urdimento –Revista de Estudos em Artes Cênicas, Florianópolis 3 (42): 1–22.

- Jamieson, H. V. (2008). “Adventures in Cyberformance - Experiments at the Interface of Theatre and the Internet.” Master's thesis in Drama, Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland Universty of Technology.

- Marques, D. 2021. “O impacto da pandemia de Covid-19 na digitalização do Ensino Superior.” Dissertação de Mestrado em Gestão de serviços. Universidade do Porto.

- Mastrominico, B. 2022. “Bodies:On:Live - Magdalena:On:Line.” In International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 18 (1): 196–199.

- Moreira, J. A. M., S; Henriques, and D. Barros. 2020. “Transitando de um ensino remoto emergencial para uma educação digital em rede, em tempos de pandemia.” Revista Dialogia, São Paulo 34: 351–364. https://doi.org/10.5585/dialogia.n34.17123. ISSN: 1983-9294.

- Najima, F. M. 2020. “Ciberperformances e a Cibernética. Revista outras Fronteiras.” Cuiabá-MT 7 (1): 1–19. ISSN: 2318-5503.

- Resnick, M. 2022. Jardim de infância para a vida toda: por uma aprendizagem criativa, mão na massa e relevante para todos. Trad.: Mariana Casetto Cruz, Lívia Rulli Sobral. Porto Alegre: Penso.

- Santana, C., and J. Moreira. 2020. “Cartografando experiências de aprendizagem em plataformas digitais: perspectivas emergentes no contexto das pedagogias das conexões.” In Espaços de aprendizagem em redes colaborativas na era da mobilidade, edited by Simone Lucena, Marilene Batista da Cruz Nascimento, and Paulo Boa Sorte. Aracaju/SE: EDUNIT.

- Silva, M. G. C. 2020. “Ensino remoto de emergência na educação infantil bilíngue.” In Educação em tempos de pandemia: Brincando um mundo possível, edited by Fernanda Coelho Liberali, Valdite Pereira Fuga, Ulysses Camargo Corrêa Diegues, and Márcia Pereira de Carvalho. 1st ed., 245–252. Campinas, SP: Pontes Editores.

- Soares, I. R. 2020. “Webconferência: os momentos síncronos na prática.” Goiânia: Instituto Federal de Goiás, Pró-Reitoria de ensino, Diretoria de educação à distância. Accessed July 29. 2022. https://ifg.edu.br/attachments/article/19169/Webconfer%C3%AAncias_%20os%20momentos%20s%C3%ADncronos%20na%20pr%C3%A1tica!%20.

- Sullivan, E. 2020. “Live to Your Living Room: Streamed Theatre, Audience Experience, and the Globe’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream Participations.” Journal of Audience and Reception Studies.Volume 17 (1): 92–119.

- Tussi, G., E. Neves, and A. Fásvero. 2022. “Aprendizagem criativa e formação docente no Ensino Superior.” Revista Educar Mais 6 (1): 737–747. https://doi.org/10.15536/reducarmais.6.2022.2859.

- Vieira, M. 2021. “Integração das tecnologias digitais na prática pedagógica.” Master's thesis in Education and Digital Technologies. Porto, Universidade do Porto.

- Woolway, E., E. Badillo, and D. Lemov. 2021. “Conclusão: Planejando para o futuro.” In Ensinando na sala de aula online: sobrevivendo e sendo eficaz no novo normal. Org. Doug Lemov, Equipe Teach Like a Champion. Trad. Sandra Maria Mallmann da Rosa. Porto Alegre: Penso. ISBN: 978-65-81334-20-8.