Abstract

The use of quasi-markets in diverse areas of social and health care has grown internationally. This has been accompanied by a growing awareness of how governments can manage these markets in order to meet their goals, with a range of terms emerging to encapsulate this such as market “shaping”, “stewarding” or “steering”. The task is further complicated because there are many types of quasi-market, encompassing contracting, commissioning, tendering and the use of individual budgets. In this paper we provide a narrative review of the evidence on attempts at management of quasi-markets based on the tools of individual budgets or voucher systems (referred to as personalization markets). Though much theory exists, we find limited empirical evidence to guide practitioners in market shaping activities of quasi-markets using individual budgets or voucher systems. More practice-orientated empirical evidence is needed regarding what does and does not work in supporting quasi-markets.

Introduction and background

Quasi-markets have become a common feature of public sector service provision internationally (Cutler and Waine Citation1997; LeGrand and Bartlett Citation1993; Rhodes Citation2007). Originally, quasi-markets proliferated under new public management approaches to public service provision – a paradigm that emphasizes the use of market philosophies and business sector practices in the delivery of government funded services (LeGrand and Bartlett Citation1993; Osborne Citation2010). Proponents of new public management argued that markets could deliver services more efficiently than government; through competition governments can improve service quality while reducing costs (Girth et al. Citation2012; LeGrand and Bartlett Citation1993). Supply-side factors have been accompanied by demand-side drivers including the desire to give citizens a greater choice in the design and delivery of the services they utilize (Girth et al. Citation2012). Markets, it has been argued, give citizens greater choice through facilitating services provision by a diverse range of providers (rather than one government provider) (LeGrand Citation2007).

The shift from direct service provision toward the use of market mechanisms in the public sector has famously been described as a change from governments “rowing” to “steering”. Steering was seen as a radically new way of performing government (Osborne and Gaebler Citation1992) whereby government increased its contracting, commissioning and tendering to non-government organizations (Dearnaley Citation2013). Often used for care and welfare-based services, these arrangements are not markets in the usual sense intended by neoclassical economic theory, which has led to the term “quasi-markets”. The consumer of the services and the purchaser are separate entities, reducing the drive to economize upon which market efficiencies are thought to depend (Slater and Tonkiss Citation2001). In addition, providers are not necessarily in competition for profit, prices are often fixed, consumer purchasing power is exercised differently than traditional markets (i.e. voucher systems or allocated budgets), and at the point of service the “product” is free or subsidized (LeGrand Citation2007; LeGrand and Bartlett Citation1993).

In industrialized countries quasi-markets now exist across care and welfare based services, such as health care (Exworthy, Powell, and Mohan Citation1999), childcare (Penn Citation2007), education (Adnett and Davies Citation2003; Dow and Braithwaite Citation2013), disability (Carey et al. Citation2017; Glasby and Littlechild Citation2009; Needham Citation2010) and aged care (Baxter, Rabiee, and Glendinning Citation2013; Braithwaite, Makkai, and Braithwaite Citation2007; Glasby and Littlechild Citation2009). The diversity of areas in which quasi-markets now operate is mirrored by a diversity in the range of mechanisms used to create and manage these markets. There has been particular growth in in personalization markets, whereby individualized budget approaches and voucher systems are given directly to individuals who then purchase services from the market (Dickinson and Glasby Citation2010). These have been a dominant feature of a range of service reforms in the UK and Australia in particular (Carey et al. Citation2017), and growing discussion about how governments perform stewardship within this new market context (Gash et al. Citation2013). This paper reviews the evidence explicitly on this most recent, and increasingly popular, approach to quasi-markets that has emerged with the turn to personalization.

Despite the growth of quasi-markets in various forms, the evidence base is highly contested (Lowery Citation1998). Many examples of monopolies (i.e. providers having excessive market power), market gaps (i.e. a lack of meaningful choice) or other market failures have emerged in public service quasi-markets from childcare (Sumsion Citation2012) to employment (Considine and O’Sullivan Citation2015). For example, employment service markets in Australia have seen wide-spread gaming of the system while failing to boost long term employment of vulnerable groups (Considine and O’Sullivan Citation2015). In childcare, closures have led to large market gaps (Sumsion Citation2012). A broader criticism of quasi-market approaches is that they maintain the focus of responsiveness on the relationship between funder-provider, rather than provider-client (Taylor-Gooby Citation2008). Currently, it remains unclear whether the introduction of competition and provider diversity through markets has improved service quality or citizen outcomes (Considine, Lewis, and O’Sullivan Citation2011; Gash Citation2014; Needham and Glasby Citation2015; Williams and Dickinson Citation2016).

While market-purists continue to argue that markets can self-regulate to create efficiency and support growth and prosperity (LeGrand Citation2007), there is growing recognition in practice on the need to manage public sector quasi-markets, and potentially even rethink their design. This has stemmed from the responsibility of governments to protect the wellbeing of citizens through guarding against market gaps or problems which could cause harm. Across the academic literature and in practice we see growing interest in how governments might manage public sector quasi-markets to address market failures (Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke Citation2006; Cogan, Hubbard, and Kessler Citation2005; Gash Citation2014; Girth et al. Citation2012; Hudson Citation2015; Scotton Citation1999). At the most basic level, governments are expected to create the conditions upon which public sector quasi-markets, including personalization markets, can work effectively. This means ensuring that:

New providers can to enter the market and grow.

Providers are competing actively, and in desirable ways.

Providers are able to exit the market [in an orderly way].

Those choosing services (whether service users or public officials choosing on their behalf) must be able to and motivated to make informed choices.

Levels of funding must be appropriate to achieve government’s objectives (Gash Citation2014, 23).

In addition to these basic responsibilities, there are expectations that governments should go further to guard against market gaps and failures. Attempts to redress quasi-market problems through active management have variously been referred to as “market shaping” (Needham et al. Citation2018), “market stewardship” (Carey et al. Citation2017; Gash Citation2014; Moon et al. Citation2017) and “market steering” (Gash Citation2014). Gash (Citation2014) provides an overview of market stewardship responsibilities, whereby governments must:

Engage closely with users, provider organizations and others to understand needs, objectives and enablers of successful delivery.

Set the “rules of the game” and allowing providers and users to respond to the incentives this creates.

Constantly monitor the ways in which the market is developing and how providers are responding to these rules, and the actions of other providers.

Adjust the rules of the game in an attempt to steer the system (much of which is, by design, beyond their immediate control) to achieve their high-level aims (Gash Citation2014, 6).

While these principles, along with the basic responsibilities outlined earlier, are informative, they tell us little about the actual practice of market shaping (i.e. what specific actions do government agencies take to shape quasi-markets). Indeed, despite increased efforts to undertake and support quasi-market shaping/stewardship for care and welfare services there is no systematic knowledge of what approaches have been tried, what problems they have sought to address, and what works. In this paper we provide a narrative review of the evidence on market shaping/stewarding efforts in quasi-markets, including both the academic and gray literature. The paper aims to synthesize what is known about effective quasi-market shaping activities within personalization markets, as well as identify existing gaps in knowledge.

With substantial theory but limited empirical evidence on effective management of quasi-markets underpinned by individual budgets, this paper takes a broad approach – examining management across domains of care (health, education, aged care, disability, health). From the limited evidence identified, we find that a tension exists between who is best placed to manage quasi-markets – central governments or local actors? Evidence indicates that while the latter is more effective, barriers exist to local level action. Overall, from our review we argue that policy-makers are currently “operating blind” when it comes to quasi-market management of individual budget programs, despite growing calls for market shaping and stewarding efforts. More practice-orientated empirical evidence is needed of what does and does not work in supporting complex quasi-markets underpinned by individual budget or voucher systems.

Methods

The intent of this meta-analysis is to search both the peer-reviewed and gray literature in order to understand what quasi-market shaping/stewarding activities have been empirically studied and detect patterns in what is, and is not, effective. While meta-analyses often rely on statistical analysis, we took a thematic approach or narrative synthesis – examining qualitative insights from empirical case studies. Overall, narrative synthesis through thematic analysis seeks to uncover concepts and their meanings from the data (rather than pre-determining them), using interpretive approaches to ground the analysis in that data (i.e. existing studies) (Dixon-Woods et al. Citation2005). Thematic approaches are useful for hypothesis generation and explanation of particular phenomena, although they provide a less-detailed picture of the context and quality of the individual studies that comprise the review (Dixon-Woods et al. Citation2005). Drawing on the Cochrane approach, reviews take a large quantity of literature and synthesize down to a relatively small number of studies deemed relevant. It is not unusual to see Cochrane reviews with very small sample sizes (e.g. Siegfried Citation2014; Thomas et al. Citation2015).

The review sought to answer the questions:

What market management efforts (otherwise known as market shaping, market stewardship and market steering) for quasi-markets have been shown to be effective in care and welfare contexts?

Here, management refers to efforts to redress a problem within an existing market through some type of activity or action. Care and welfare contexts refers to any area of care within the welfare state in which quasi-market mechanisms are used.

Table 1. Overview studies.

Searches were run in the following databases: Google, Google Scholar, HMIC, Medline, Assia Proquest, EBSCO, Social Care Online, Social Sciences Citation Index, Sociological Abstracts EMBASE, ISI Citation Index.

The search terms used were:

(Thin market OR market gap OR undersupply OR underserv* OR market failure OR asymmetry) AND (care OR quasi-market OR quasi market).

(Market stewardship OR market shaping OR market levers OR market management) AND (care OR quasi-market OR quasi market).

(voucher OR voucher assisted OR Personalization OR personal* care OR personal* budgets OR individual service funds OR individual* care OR individual* budget) AND (care OR quasi-market OR quasi market).

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

Published before 1990.

In language other than English.

Non-empirical research (ie: theory based, no case study or data collection).

Does not concern a quasi-market underpinned by individual budgets or voucher systems.

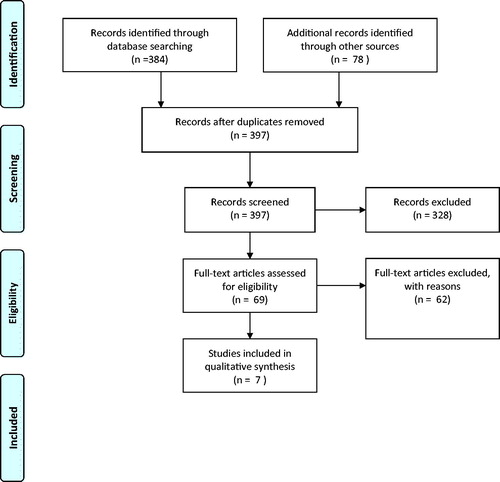

In total, 675 sources were identified and 7 were included in the final data set (see ). The large number of excluded studies is mostly accounted for by the final criteria determining the type of quasi-market of concern. Many papers did not concern quasi-markets, or those that did had a broader view of quasi-markets such as considering commissioning and contracting. As our focus is on quasi-markets underpinned by individual budgets or voucher systems we excluded papers concerning these other types of quasi-markets. No “pre and post” design studies were identified in the review. It is usual for systematic reviews to reduce possible papers from a large number to a very small number, for example a systematic review into alcohol advertising identified 4114 possibly relevant papers and through the application of exclusion criteria this was reduced to just four to be included in the final review (Siegfried et al. Citation2014).

The seven papers in the final data set sought insight into what was occurring within a specific quasi-market and shed light on market stewardship techniques. Sources were coded qualitatively and thematically, seeking to identify which management efforts had been tried, what they sought to address and what the implications were.

The papers examined a wide variety of care and welfare contexts (health, childcare, aged care, education, social care). It is worth noting that differences in language such as market stewardship and shaping reflect geographical preferences and are used interchangeably in this paper. Also, while the review originally sought to identify studies where different market management activities had been explicitly empirically tested (e.g. a pre and post design to the research), no such studies or evidence is available. It is worth noting that more theoretical (N = 42) than empirical papers were identified – highlighting the gap between commentary/rhetoric and empirical knowledge in the field.

Findings

At present, little empirically based evidence exists that supports practitioners to determine what market-shaping activities they should undertake in individual budget quasi-markets and under which circumstances. provides an overview of market stewardship and steering efforts have been tried and reported on in the literature. Papers were a mixture of reporting on specific activities, and seeking insight into the actions that were being taken to manage individual budget quasi-markets (often without deep analysis of effectiveness).

Findings were spread across the full range of quasi-markets, from competitive contracting to personalization markets. Not surprisingly, with regard to the former the most analyzed quasi-market was the UK NHS with several detailed studies assessing market management strategies (and a whole host of commentary and theoretical pieces).

While concerned with autonomous school markets, Destler and Page (Citation2010) found a reluctance to undertaken market management even when authority was given. In their case, school districts where given the job of promoting supply and encouraged to undertake necessary activities to achieve this. Through interviews, the research found that due to professional norms, ideology and belief in free market reforms there was a reluctance to undertake market stewardship and shaping activities even in noncompetitive markets where school districts understood the risks and implications of thin markets.

Gash et al. (Citation2013) provide the most comprehensive and detailed analysis of quasi-market management and design, examining a multitude of markets and management activities through a mixed methods approach (including document analysis, interviews and workshops). Gash et al. (Citation2013) study is also the only paper to examine market management strategies against external criteria for successful quasi-markets – using the principles outlined earlier in this paper for effective stewardship (e.g. enabling informed choice, low barriers to entry and exit). Though as Gash et al. (Citation2013) bundle management efforts together to assess against these criteria, insight into specific activities is less clear. For example, with regard to building informed choice they found that the combination of publishing available services, publishing ratings of services, and providing extra funding for “good” providers (determined on the basis of whether providers’ services aligned with policy goals) collectively boosted the ability of participants to make informed choices.

With regard to barriers to entry and exit, findings were mixed. Tight regulation not surprisingly creates increased barriers to market entry, though regardless of regulation it is often challenging for small providers to establish themselves in quasi-markets (Gash et al. Citation2013). Gash et al. (Citation2013) also found that removing poor providers from the market is more difficult than one might intuitively think. They found that commissioners can be “too attached” to existing providers and relationships, making them unwilling to force an exit from the market. They also found low confidence in the ability of governments to manage major transitions in the market, creating a preference for the status quo. While pertaining to design rather than management per se, Gash et al. (Citation2013) argue that effective market design tends to happen without input from prospective providers – setting markets up to need higher levels of management due to design shortcomings.

Based on their empirical research, Gash et al. (Citation2013) make a range of recommendations for market stewardship/shaping. These include: the need for central and local commissioners to test major changes to incentive structures and work closely with providers in the sector to understand implications; identifying ways to build in flexibility to contracts; publish supply and demand information.

Baxter, Rabiee, and Glendinning (Citation2013) provide a comprehensive analysis of efforts to shape a personalized market in aged care, examining efforts across three councils in England. Across their case studies they tracked the introduction of market brokers (local authority employees acting as intermediaries between support planners and providers), the creation of Market Development Officers to improve information flow regarding supply and demand, and changes to contracts. They found that brokers boosted subjective ratings of service quality, yet some providers felt that the new role created market distortions (not all providers were presented to plan holders). More critically, however, the introduction of brokers created more administrative burden for councils, providers and plan holders alike. This is concerning given one of the major challenges or limitations of personalization schemes has been the ability of participants to handle and manage large administrative loads (Dickinson and Glasby Citation2010; Needham and Glasby Citation2014). Market Development Officers had a less equivocal contribution, and were found to significantly boost supply within the market. This included specialist providers, but also capacity building for non-specialist providers to enter the market (e.g. a local takeaway shop preparing and delivering meals) (Baxter, Rabiee, and Glendinning Citation2013).

The changes to contracts that were examined by Baxter, Rabiee, and Glendinning (Citation2013) included an increase in flexibility in negotiating service. Once a contract was signed, plan holders were still able to make adjustments in both services and corresponding costs. This created more flexibility and tailored services (with appropriate financial compensation), increasingly choice and control.

In another personalization market, this one using vouchers to boost aged care home services, Defourny et al. (Citation2010) sought to understand differences between for-profit and not-for-profit providers. Their research uncovered insights for voucher assisted markets as a whole, as well as the specifics of how not-for-profits and for-profits behave in market contexts. With regard to markets as a whole, they found that accredited providers of all types are most efficient due to better organization, quality also increased when workers are trained on respectful relationships. With regard to the profit orientation of providers, not-for-profits did performed better in terms of both equality and efficiency. They were also more likely to have a limited geographical focus which meant they offered local services tailored to local needs, while for-profit providers were more likely to offer “one size fits all” services nationally.

While individually, these studies provide insight into the specific dynamics of individual markets it is difficult to draw overarching conclusions. Studies are spread across a wide range of market types, from the NHS to personalization, without a concentrated effort in any particular area. None-the-less there are a range of important insights within the literature identified.

Discussion

While we sought to identify studies where different market stewardship/shaping activities had been empirically tested through pre and post-test designs, no such studies or evidence was found. Rather, the review identified a range of insights created by more general empirical research. Yet, our review revealed that despite considerable discussion regarding the need to steward or shape public sector markets, at present there is limited empirical evidence to guide practitioners within the public policy/public administration literature. Overall, better practice-orientated empirical evidence is needed to help practitioners to make decisions about market shaping activities, and what is likely to be effective in different contexts. With regard to the evidence identified in this review, the limited empirical evidence identified coalesced around two themes; the first was who should carry out market shaping, the second is around efforts to support the growth of personalization markets. In the remainder of the discussion we address each of these in turn.

Several studies, particularly those focused on the NHS, advised against centrally set targets and rules for markets. Gash et al. (Citation2013) also draws the conclusion that market shapers must work closely with providers in developing and supporting quasi-markets. This is further supported in related commentary, for example in discussion of a case study of education markets Temple (Citation2006) argues that central governments can override natural supply and demand signals in the market creating market distortions and collapse. While this research indicates that authority for market shaping should be devolved to the local level, we found evidence to suggest that local actors may be reluctant to take up market shaping activity even where authority is given (Destler and Page Citation2010). Destler and Page found that attempts to push stewardship actions to the local level can be met with resistance, for example in the NHS Allen and Petsoulas (Citation2016) found that attempts to allow for local variability in prices, by allowing local pricing variations for commissioners, were rarely taken up. Rather, the allocation of financial risk tended to be done outside the formal structures of the market, even when attempts to change those formal structures were made. They suggest that pricing within quasi-markets can often be more complex than analysis of pricing rules would suggest. This was also supported by Gash et al’s. (Citation2013) findings that market stewards are reluctant to take action to remove poor providers. In the NHS Allen and Petsoulas (Citation2016) found that attempts to allow for local variability in prices, by allowing local pricing variations for commissioners, were rarely taken up. Together, this evidence suggests that there are tensions between central and local efforts to manage markets.

This is consistent with the economic arguments of Hayek regarding information flows in markets. Hayek (Citation1945) argued that that enormous effort and time is required for local actors to convey “knowledge of all the particulars” to a central agency, which is then faced with the task of integrating vast amounts of information in order to make decisions. In particular, Hayek noted the effort and delay involved in gathering and transmitting this knowledge to economic planners seeking to set prices for goods – the same dilemma faced by the administrators of complex market-based schemes for public service delivery. In contrast to neoclassical market theories, Hayek emphasized the dynamic and contingent effects of competition and innovation (Slater and Tonkiss Citation2001). From this perspective, market processes are context-dependent and unpredictable; market actors are always acting under conditions of relative uncertainty and no single actor (including the central regulator) has full control of events. Hence, Hayek’s perspective on market management and support provides a conceptual rationale for supporting market shaping. However, the empirical research suggests that that even though local actors may be more appropriately positioned in terms of local connections and knowledge, without capability development they are unlikely to engage in market stewardship or shaping activities (Destler and Page Citation2010; Allen and Petsoulas Citation2016; Broadhurst and Landau Citation2017). This highlights the need to understand local barriers to market shaping/stewarding and how to overcome them.

A second concentrated area of findings were identified in relation to personalization markets. This literature focused on different efforts to boost personalization markets. Following on from the focus on local versus central market shapers, some of the research concentrated on the role new local market actors could play in market shaping – such as brokers, market development officers (Baxter, Rabiee, and Glendinning Citation2013). Counter to the evidence on contract-based markets more broadly, these local actors appeared to have significant impact on competition and choice. These findings highlight that what works in one type of quasi-market (e.g. personalization) is not necessarily transferable to another (e.g. contracting). Other research on personalization looks at how different providers behaved in markets (Defourny et al. Citation2010), suggesting that promoting local suppliers and not-for-profits is more likely to result in locally responsive markets. Again, this research speaks to the importance of local knowledge in market management.

Overall, the empirical work on supporting quasi-market arrangements to succeed, and in turn to meet their policy goals, is limited and ad hoc. Thus it becomes important to consider how decisions reagarding market stewardship are being made in the absence of any robust evidence on best practice. Political science theories of the policy processes provide some useful insights into the role evidence plays in the policy decision making process. A key concept to emerge from these theories is that policy makers are constrained by “bounded rationality” whereby due to biological and cognitive constraints they are unable to take into account all evidence which may be relevant for a particular policy problem (Baumgartner, Jones, and Mortensen Citation2014; Workman, Jones, and Jochim Citation2009; Zahariadis Citation2014). To compensate for this evidence overload policy makers use two shortcuts – “rational”, where certain sources of information are prioritized and clear goals are pursued, and “irrational” where beliefs, values, emotions, and gut feelings are used to make decisions quickly (Cairney and Oliver Citation2017). In the absence of any robust evidence base on quasi markets policy makers in the position of stewarding or shaping quasi-markets have little option but to rely upon the second decision making short-cut, thus making decisions based upon their own values, belief systems, and practical judgements. It is worth noting that this type of decision making is a common features of policy making irrespective of the availability of evidence (Head Citation2008; Cairney Citation2016a).

However, policy process theories also show that in a complex and unpredictable policy decision making environment power is shared between different actors all wishing to “push” their particular policy ideas or agenda (Cairney and Oliver Citation2017; Cairney Citation2016b). To do this political actors utilize tactics of coalition forming, manipulation, and persuasion by establishing a dominant way to “frame” a particular policy problem and reduce the ambiguity policy makers may be feeling about particular policy decisions (Cairney and Oliver Citation2017). In a context where there is a lack of a robust evidence base such as the case of market shaping/stewardship, these tactics are likely to be even more successful in inducing policy makers to frame a problem in one principal way. This can become problematic when problems are then only viewed through a narrow ideological lens, limiting the scope of solutions. Conversely, as has happened in market stewardship, it may also lead to policy experimentation where there are different ideas being championed which lack the backing of an evidence base and have shown to be detrimental to users (Considine, Lewis, and O’Sullivan Citation2011). Thus developing an evidence base for policy makers and practitioners engaged in market shaping/stewardship is vital to ensure balance in the way decisions on best practice solutions to emerging issues are being made. Without this evidence base decisions will continue to be made based on nothing more than underlying value and belief systems and emotional responses to problems. Further, this also increases the chances that those with the resources to push a particular policy agenda will be able to exert disproportionate influence on decision makers in the absence of any counteracting evidence base.

Conclusion

There are growing calls for governments to actively manage quasi-markets underpinned by individual budgets or voucher systems, with highly variable outcomes seen worldwide. Governments internationally continue to institute quasi-market arrangements, despite tensions regarding whether quasi-market are able to meet the policy goals that underpin their use, which often relate to social care and the equitable provision of public services rather than market growth or business innovation in isolation. Our evidence review revealed that at present the evidence base practitioners can draw on to make market stewardship and shaping decisions is very limited. This means that there will be an increased tendency for policy makers and practitioners to base judgements on well established value and belief systems and make decisions using shortcuts that rely on emotions and familiarity with information. Additionally a lack of evidence increases the opportunity for policy actors seeking to influence decision makers to be more effective in using persuasive and manipulative strategies to influence the emotional responses to policy problems. Without evidence of what works, decisions may be made that lead to worse outcomes for users and potentially cement a particular ideological position. As Head (Citation2010, 80) rightly notes, the “need for good information is one of the foundations for good policy and review processes”.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adnett, N., and P. Davies. 2003. “Schooling Reforms in England: From Quasi-Markets to Co-opetition?” Journal of Education Policy 18 (4): 393–406. doi:10.1080/0268093032000106848.

- Allen, P., and C. Petsoulas. 2016. “Pricing in the English NHS Quasi Market: A National Study of the Allocation of Financial Risk through Contracts.” Public Money & Management 36 (5): 341–348. doi:10.1080/09540962.2016.1194080.

- Baumgartner, F. R., B. D. Jones, and P. B. Mortensen. 2014. “Punctuated Equilibrium Theory: Explaining Stability and Change in Public Policymaking.” In Theories of the Policy Process. 3rd ed, edited by P. A. Sabatier and C. M. Weible, 59–103. New York: Westview Press.

- Baxter, K., P. Rabiee, and C. Glendinning. 2013. “Managed Personal Budgets for Older People: What Are English Local Authorities Doing to Facilitate Personalized and Flexible Care?” Public Money & Management 33 (6): 399–406. doi:10.1080/09540962.2013.835998.

- Braithwaite, J., T. Makkai, and V. Braithwaite. 2007. Regulating Aged Care: Ritualism and the New Pyramid. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Broadhurst, S., and K. Landau. 2017. “Learning Disability Market Position Statements, Are They Fit for Purpose?” Tizard Learning Disability Review 22 (4): 198–205. doi:10.1108/TLDR-03-2017-0011.

- Brown, T. L., M. Potoski, and D. M. Van Slyke. 2006. “Managing Public Service Contracts: Aligning Values, Institutions, and Markets.” Public Administration Review 66 (3): 323–331. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00590.x.

- Cairney, P. 2016a. The Politics of Evidence Based Policy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Pivot.

- Cairney, P. 2016b. The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making. 1st ed. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Pivot.

- Cairney, P., and K. Oliver. 2017. “Evidence-Based Policymaking is Not Like Evidence-Based Medicine, So How Far Should You Go to Bridge the Divide Between Evidence and Policy?” Health Research Policy and Systems 15 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/s12961-017-0192-x.

- Carey, G., H. Dickinson, E. Malbon, and D. Reeders. 2017. “The Vexed Question of Market Stewardship in the Public Sector: Examining Equity and the Social Contract Through the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme.” Social Policy & Administration 52: 387–407. doi:10.1111/spol.12321.

- Cogan, J. F., R. G. Hubbard, and D. P. Kessler. 2005. “Making Markets Work: Five Steps to a Better Health Care System.” Health Affairs 24 (6): 1447–1457. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1447.

- Considine, M., J. Lewis, and S. O’Sullivan. 2011. “Quasi-Markets and Service Delivery Flexibility Following a Decade of Employment Assistance Reform in Australia.” Journal of Social Policy 40 (4): 811–833. doi:10.1017/S0047279411000213.

- Considine, M., and S. O’Sullivan. 2015. Contracting-Out Welfare Services. Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Cutler, T., and B. Waine. 1997. “The Politics of Quasi-Markets How Quasi-Markets Have Been Analysed and How They Might Be Analysed.” Critical Social Policy 17 (51): 3–26. doi:10.1177/026101839701705101.

- Dearnaley, P. 2013. “Competitive Advantage in the New Contrived Social Care Marketplace: How Did We Get Here?” Housing, Care and Support 16 (2): 76–84. doi:10.1108/HCS-03-2013-0002.

- Defourny, J., A. Henry, S. Nassaut, and M. Nyssens. 2010. “Does the Mission of Providers Matter on a Quasi-Market? The Case of the Belgian ‘Service Voucher’ Scheme: Does the Mission of Providers Matter on a Quasi-Market?” Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 81 (4): 583–610. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8292.2010.00423.x.

- Destler, K., and S. B. Page. (2010). Building Supply in Thin Markets: Districts’ Efforts to Promote the Growth of Autonomous Schools. Working Paper. Bellingham, WA: Western Washington University.

- Dickinson, H., and J. Glasby. 2010. The Personalisation Agenda: Implications for the Third Sector. Working Paper. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham.

- Dixon-Woods, M., S. Agarwal, D. Jones, B. Young, and A. Sutton. 2005. “Synthesising Qualitative and Quantiative Evidence: A Review of Possible Methods.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1177/135581960501000110.

- Dow, K., and V. Braithwaite. 2013. Review of Higher Education Regulation Report. Canberra : Department of Innovation. file: http:///Users/Gem/Desktop/finalreviewreport.pdf.

- Exworthy, M., M. Powell, and J. Mohan. 1999. “The NHS: Quasi-Market, Quasi-Hierarchy and Quasi-Network?” Public Money and Management 19 (4): 15–22. doi:10.1111/1467-9302.00184.

- Gash, T. 2014. Professionalising Government’s Approach to Commissioning and Market Stewardship. London: Institute of Government.

- Gash, T., N. Panchamia, S. Sims, and L. Hotson. 2013. Making Public Service Markets Work. London: Institute of Government.

- Girth, A. M, A. Hefetz, J. M. Johnston, and M. E. Warner. 2012. “Outsourcing Public Service Delivery: Management Responses in Noncompetitive Markets.” Public Administration Review 72 (6): 887–900. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02596.x.

- Glasby, J., and R. Littlechild. 2009. Putting Personalisation into Practice. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Hayek, F. 1945. “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” The American Economic Review 35 (4): 519–530.

- Head, B. W. 2008. “Three Lenses of Evidence-Based Policy.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 67 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00564.x.

- Head, B. W. 2010. “Reconsidering Evidence-Based Policy: Key Issues and Challenges.” Policy and Society 29 (2): 77–94. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2010.03.001.

- Hudson, B. 2015. “Dealing with Market Failure: A New Dilemma in UK Health and Social Care Policy?” Critical Social Policy 35 (2): 281–292. doi:10.1177/0261018314563037.

- LeGrand, J. 2007. Delivering Public Services through Choice and Competition: The Other Invisible Hand. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- LeGrand, J., and W. Bartlett. 1993. Quasi-Markets and Social Policy. London: Macmillan.

- Lindholst, A. C., O. H. Petersen, and K. Houlberg. 2018. “Contracting Out Local Road and Park Services: Economic Effects and Their Strategic, Contractual and Competitive Conditions.” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 64–85.

- Lowery, D. 1998. “Consumer Sovereignty and Quasi-Market Failure.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 8 (2): 137–172. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024376.

- Moon, K., D. Marsh, H. Dickinson, and G. Carey. 2017. Is All Stewardship Equal? Developing a Typology of Stewardship Approaches. Canberra, Australia: University of New South Wales.

- Needham, C. 2010. “Debate: Personalized Public Services – a New State/Citizen Contract?” Public Money & Management 30 (3): 136–138. doi:10.1080/09540961003794246.

- Needham, C., and J. Glasby. 2014. Debates in Personalisation. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Needham, C., and J. Glasby. 2015. “Personalisation – Love It or Hate It?” Journal of Integrated Care 23 (5): 268–276. doi:10.1108/JICA-08-2015-0034.

- Needham, C., K. Hall, K. Allen, E. Burn, C. Mangan, and M. Henwood. 2018. Market-Shaping and Personalisation, A Realist Review of the Literature. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham.

- Osborne, S. 2010. “Public Governance and Public Service Delivery: A Research Agenda for the Future.” In The New Public Governance, edited by S. Osborne, 413–429. New York: Routledge.

- Osborne, D., and T. Gaebler. 1992. Reinventing Government. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Penn, H. 2007. “Childcare Market Management: How the United Kingdom Government Has Reshaped Its Role in Developing Early Childhood Education and Care.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 8 (3): 192–207. doi:10.2304/ciec.2007.8.3.192.

- Ranerup, A. 2007. Rationalities in the Design of Public E-Services. Journal of E-Government 3 (4): 39–64. doi:10.1300/J399v03n04_03.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. 2007. “Understanding Governance: Ten Years On.” Organization Studies 28 (8): 1243–1264. doi:10.1177/0170840607076586.

- Scotton, R. 1999. “Managed Competition:The Policy Context.” Australian Health Review 22 (2): 103. doi:10.1071/AH990103.

- Siegfried, N. 2014. “Does Banning or Restricting Advertising for Alcohol Result in Less Drinking of Alcohol?” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Drug and Alcohol Group).

- Siegfried, N., D. C. Pienaar, J. E. Ataguba, J. Volmink, T. Kredo, M. Jere, and C. D. Parry. 2014. Restricting or Banning Alcohol Advertising to Reduce Alcohol Consumption in Adults and Adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD010704. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010704.pub2.

- Slater, D., and F. Tonkiss. 2001. Market Society: Markets and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Sumsion, J. 2012. “ABC Learning and Australian Early Education and Care: A Retrospective Ethical Audit of a Radical Experiment.” Chapter 12. In Childcare Markets Local and Global: Can They Deliver Equitable Service, edited by E. Lloyd, & H. Penn, 209–225. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Taylor-Gooby, P. 2008. “Choice and Values: Individualised Rational Action and Social Goals.” Journal of Social Policy 37 (2): 167–185. doi:10.1017/S0047279407001699.

- Temple, P. 2006. “Intervention in a Higher Education Market: A Case Study.” Higher Education Quarterly 60 (3): 257–269. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2273.2006.00320.x.

- Thomas, R., L. Barker, G. Rubin, and A. Dahlmann-Noor. 2015. “Assistive Technology for Children and Young People With Low Vision.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD011350. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011350.pub2.

- Viitanen, T. K. 2011. Child Care Voucher and Labour Market Behaviour: Experimental Evidence from Finland. Applied Economics 43 (23): 3203–3212. doi:10.1080/00036840903508346.

- Williams, I., and H. Dickinson. 2016. “Going It Alone or Playing to the Crowd? A Critique of Individual Budgets and the Personalisation of Health Care in the English National Health Service: Individual Budgets and the Personalisation of Health Care.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 75 (2): 149–158. doi:10.1111/1467-8500.12155.

- Workman, S., B. D. Jones, and A. E. Jochim. 2009. “Information Processing and Policy Dynamics.” Policy Studies Journal 37 (1): 75–92. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00296.x.

- Yang, K., J. Y. Hsieh, and T. S. Li. 2009. “Contracting Capacity and Perceived Contracting Performance: Nonlinear Effects and the Role of Time.” Public Administration Review 69 (4): 681–696.

- Zahariadis, N. 2014. “Ambiguity and Multiple Streams.” In Theories of the Policy Process. 3rd ed, edited by Paul A. Sabatier and C. M. Weible. New York: Westview Press.