Abstract

At the intersection between theory and practice on “design” and “policy,” there is small but expanding knowledge base on the concept of “design for policy.” Government interest in design methods for policy-making has grown significantly since the late 1990s, particularly within policy labs. Policy labs are multidisciplinary government teams experimenting with a range of innovation methods, including design, to involve citizens in public policy development. There are more than 100 labs across the globe and around 14 at national and regional levels in the UK. While new policy labs continue to pop up, some are changing and some are closing their doors. How have the operating models of policy labs evolved? How might we enhance the resilience of labs? These are some of the questions explored in a 2-year Arts and Humanities Research Council Fellowship called People Powering Policy. The research draws on insight from established Labs including Policy Lab in the Cabinet Office, HMRC Policy Lab and the Northern Ireland Innovation Lab as well as emerging labs to address the research question: how might policy labs be developed, reviewed and evaluated? Based on interviews, workshops and immersive residencies the main outputs were a Typology of Policy Lab Financing Models and a Lab Proposition Framework for establishing, reviewing and evaluating policy labs. The typology outlines four models for UK labs financing models – Sponsorship (funding from one or multiple departments), Contribution (labs recover part of the costs of projects), Cost Recovery (labs charge for projects on a not-for-profit basis), Hybrid (labs benefit from multiple income sources such as Sponsorship, charging and knowledge exchange funding) and Consultancy (labs charge a consultancy rate with a profit margin to expand operations). The Lab Proposition Framework comprises of four components (1) Proposition – the vision, governance and finance models; (2) Product – the offering, user needs and tools; (3) People – the people skills, knowledge diffusion and wider capacity building; (4) Process – the routes to engagement, user journey and promotion mechanism.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

A substantial bank of knowledge exists on “policy” and “design” as separate concepts but a limited body of academic theory and scholarly knowledge exists at the intersection between the two concepts that is “design for policy” (Bason Citation2014, 3; Amatullo Citation2014, 152; Junginger Citation2014, 57; Staszowski, Brown, and Winter Citation2014, 155; Jegou, Thevenet, and Vincent Citation2014, 156; Halse Citation2014, 210). While designers and governments have been applying design principles to public sector services since the 1960s (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008, 5; Puttick, Baeck, and Colligan Citation2014, 13), the application of design to public policy has only gained traction since the late 1990s (Bason Citation2014, 3; Howlett Citation2014, 199), particularly in policy labs. Policy labs are multi-disciplinary government units using a range of innovation methods, including design, to collaboratively engage users and stakeholders in service and policy development (Whicher Citation2020, 4). In the UK, there are policy labs and user-centered policy design teams operating at national level (for example, Policy Lab which moved from the Cabinet Office to the Department of Education in 2020, HMRC Policy Lab and Ministry of Justice User-centered Policy Design Team) and regional levels (for example, the Northern Ireland Innovation Lab and Welsh Government Innovation Lab) and many used to operate at local levels. Staszowski, Brown, and Winter (Citation2014, 163), succinctly acknowledge that although the overall design agenda is growing within government (albeit with a prevalence for digital public services), design for policy is still an emerging practice. As such, in the case of “design for policy,” it could be argued that practice is well in advance of theory. As these labs mature and gain credibility there is an opportunity to review their progress. There is a need to evaluate the impact of policy labs in order for them to gain greater traction across government. Consequently, the research question guiding this article is how might policy labs and user-centered policy design teams be developed, sustained and evaluated? This question was addressed as part of a 2-year Arts and Humanities Research Council project called People Powering Policy drawing on immersive residencies, interviews and workshops with established and emerging labs. Consequently, a number of iteratively tested and validated outputs have been created including a Lab Proposition Framework for developing, reviewing and evaluating policy labs and user-centered policy design teams and a Typology of Policy Labs’ Financing Models.

2. Design for policy and policy labs in a UK context

As observed by Williamson (Citation2015, 251), Bason and Schneider (Citation2014, 34) and Junginger (Citation2012, 117), the are a number of denominations or classifications for specialist government units applying design approaches to policy-making. They operate under a number of guises with slightly different nuances including “policy labs,” “policy innovation labs,” “social labs,” “design labs,” “co-design labs,” “public sector innovation labs,” “government innovation labs” (or “i-teams”), “public and social innovation labs” (or “psilabs”), “public innovation spaces” and “user-centered policy design teams,” among other terms (Williamson Citation2015, 251; Bason and Schneider Citation2014, 34; Junginger Citation2012, 117). Fundamentally, the implication is that these labs deal with innovation in public services and public policies. Furthermore, when also considering the wider non-governmental space there are more examples such as Living Labs. The European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL), with more than 150 active labs, defines Living Labs as “user-centered, open innovation ecosystems based on a systematic user co-creation approach integrating research and innovation processes in real life communities and settings.”Footnote1 There are a growing number of non-governmental players within the policy lab space, including academics, designers, management consultants, community groups and think tanks, but this article refers to design for policy being conducted within government-owned teams. The terms policy lab and user-centered policy design team (UCPD) have been adopted as the operational terms for this research to narrow the focus on design for policy (rather than the wider topic of design for public services) and due to the preeminence of their use in the UK – the dominant context for this research. For Williamson (Citation2015, 252), “labification” means apply the scientific approaches of experimentation, testing and measurement to the policy process.

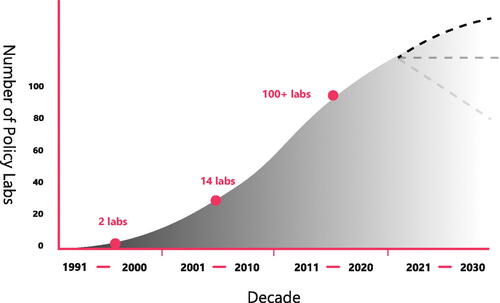

Nesta is a UK innovation foundation and has taken a leading role in creating a global community of government policy labs through their “States of Change” work and research.Footnote2 According to Nesta, in the decade 1991 to 2000 there were only two policy labs in operation – Helsinki Design Lab in Finland (now closed) and PS21 in Singapore. In the period 2001 to 2010, a further 14 Labs were established around the world (Puttick, Baeck, and Colligan Citation2014, 13) and by the subsequent decade, the number of labs had grown exponentially with Nesta estimating more than 100 in operation (see ). There is no data on what proportion of these Labs use design methods or what proportion use design methods for policy-making. A study commissioned by the EU Policy Lab has identified 65 in Europe (Fuller and Lochard Citation2016, 4–5) and in the UK, in 2020, there were around ten national labs and three regional labs in operation (Whicher Citation2020, 15).

In the UK, there appear to be two overarching policy agendas under which design for policy has gained traction – Open Policy-making and Devolution (Taylor Citation2014, 14; Siodmok Citation2014, 25; Williamson Citation2015, 258). Open Policy-making has become a dominant paradigm for experimentation in government focused on developing and delivering policy in a fast-paced and digital world using collaborative and iterative approaches while devolution is the transfer of power from national, centralized government to devolved, decentralized government. Specifically, in a UK context, growing interest in design for policy can be condensed into six main factors – the changing nature of evidence, growing interest in user-centered approaches, a focus on end-to-end policy-making, a drive for more meaningful public consultation, the need for rapid policy prototyping (particularly in the context of COVID-19 response) and the rise of futures thinking (such as speculative design) (Whicher Citation2020, 15).

Over the course of the last decade there has been a drive in government to take decision-making closer to the citizen and design research has been embraced as one of a number of approaches for understanding the lived-experiences of the citizen to inform more “open policy-making” (Siodmok Citation2020). There has been a gradual shift in emphasis away from the idea of “doing to” the citizen toward “doing with” the citizen. As articulated by one interviewee, “The ultimate goal is to find the Holy Grail of user-centred policy-making.” it is important to articulate that a design approach to policy is not about “supplanting or usurping empirical approaches but complementing and enhancing them.” This is the notion of “big data plus thick data” (Siodmok Citation2020). Economists tend to be the gatekeepers of policy, making generalization from large datasets (big data) while design researchers conduct deep research into smaller samples (thick data) (Maffei, Leoni, and Villari Citation2020;124). Policy Lab uses “big data to see the big picture before then using thick data to zoom into the detail of people’s lived experiences” (Siodmok Citation2020). As such, design research is about humanizing the numbers. Design research can contribute to evidence-based policy-making by supplementing traditional quantitative-based evidence with in-depth qualitative-based evidence.

Traditionally, the policy process has been very siloed and there has been a need to “bring policy development and service delivery together with the public” according to a policy lab interviewee. Design research can take a “holistic view of the policy cycle or “journey” balancing the demands of people on all sides” – ministers, policy-makers, intermediaries and policy “users” according to another. Sometimes, policy users or beneficiaries are not actively involved in public engagement exercises prior to very formalized public consultation, which can often isolate those best placed to provide input to the policy process. Once a policy reaches public consultation it is unlikely to significantly change its trajectory and sometimes public consultation has been seen as a “tick box exercise.” However, there is a drive within government to transform public engagement and public consultation to ensure that it is more meaningful and actively engages those who would not normally participate in formalized engagement and consultation processes.

COVID-19 has accelerated progression on many socio-economic issues such as cashless society, remote workforces and low carbon economy but perhaps most significantly it has accelerated the mode of policy-making. COVID-19 necessitated rapid, iterative policy-making where ministers and senior civil servants were required to adopt even shorter decision-making times. According to government interviewees, there is a perception that the “timelines of traditional academic research do not correspond to the pace of policy-making.” One of the reasons why design research and practice has gained traction in government is because it has resulted in “shorter cycles of decision-making particularly through policy prototyping” and getting something “live into the field for iterating and testing.” By introducing rapid policy prototyping at the early stages of the policy cycle, design approaches can de-risk delivery further down the line by ensuring that policy concepts are desirable, feasible and viable. Prototyping is central to all design processes and prototyping policy is also very much an emerging concept but one which unprecedented times is pushing governments to explore (Kimbell and Bailey Citation2017, 214). There is also a need to adopt a longer-term outlook in policy-making. Governments are also experimenting with more niche design research areas like speculative design and design futures – using alternative possible futures to provoke, inspire and provide a critical commentary to inform policy-making.

3. Method

This research has been conducted as part of an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Fellowship project called “People Powering Policy.”Footnote3 The aim of the project was to understand if, where and how design might add value to the policy process through greater citizen participation, particularly within policy labs. The Fellowship took place between September 2017 and August 2019 and involved four live policy projects with HMRC Digital (the UK tax office), the Northern Ireland Department of Health, the Financial Conduct Authority’s Behavioral Insights Team and the Welsh Government Permanent Secretary’s Group. Through the four immersive policy projects, interviews and 21 co-design workshops a number of outputs were created: a Typology of Policy Labs’ Financing Models, a Lab Proposition Framework for establishing, reviewing and evaluating policy labs and UCPD teams, a Design for Policy Model demonstrating how design can add value to the policy cycle and PROMPT – a Design for Policy Toolkit. This article focuses on the Typology of Policy Labs’ Financing Models and the Lab Proposition Framework. This enquiry focuses specifically on the research question: how might policy labs and user-centered policy design teams be developed, reviewed and evaluated?

This explorative research has adopted a design research framework in order to iteratively construct a framework to develop, review and evaluate policy labs and user-centered policy design teams. A Design research framework advocates the concept of research “for design, by design” through iterative and collaborative approaches combining “divergent and convergent thinking” (Blessing and Chakrabarti Citation2009, 9; https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/what-framework-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond). A design research framework prescribes explorative, inductive approaches where broad insight is gathered from research participants and iteratively refined, tested and validated. For the purposes of this intervention, there were five evolving stages to the design research approach:

Stage 1: Investigation into the changing financing models of Policy Lab, iLab and EU Policy Lab (interviews with lab heads and teams – n10 in September 2016 and April 2020).

Stage 2: Investigation into the governance and impact of iLab (interviews with senior civil servants, lab head, lab staff and clients – n30 September to December 2016).

Stage 3: Explorative investigation into the drivers and barriers facing HMRC Policy Lab and iLab (two immersive, one-month residencies with labs in November 2017 and September 2018).

Stage 4: Explorative workshops to define the user needs and feasibility of HMRC Policy Lab and Welsh Government Innovation Lab (London workshop 35 participants in November 2017, Cardiff workshop 18 participants in December 2018).

Stage 5: Explorative workshop to consolidate the Labs Proposition Framework (n19 participants from seven labs in November 2018).

Stage 1: Through on-going research as well as commercial interventions, including design for policy training, the author has established a long-standing relationship with Policy Lab (in the Cabinet Office from 2014 to 2020 and subsequently in the Department for Education from mid-2020) and iLab in the Northern Ireland Department of Finance. Over time, it was observed how the financing models for the two labs were changing. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with the heads and policy officers of Policy Lab, iLab and EU Policy Lab (n6) in September 2016 to collect data for the years 2014 and 2016. Telephone interviews were conducted with the heads and policy officers of Policy Lab and iLab (n4) in April 2020 to collect data for 2020 – the 2020 data for EU Policy Lab was taken from their website due to the unavailability of participants. The questions centered on the number of staff members, dominant innovation methods, annual budgets, how they charge clients for projects as well as other questions not included in this study. The outcome of this examination was a typology of lab financing models (see section 4). The main insights from this were that the financing models of policy labs have evolved from when they were established as they gain credibility and legitimacy contributing to the overall Lab Proposition Framework to develop, review and evaluate labs.

Stage 2: From September to December 2016, the author was commissioned to conduct an evaluation of the governance structures and projects of iLab. The evaluation was based on 30 interviews with Lab staff, the wider Northern Ireland Civil Service (including senior civil servants) and external stakeholders. Details of this evaluation are presented elsewhere (Whicher Citation2017; Whicher and Crick Citation2019); however, it is part of the journey toward inductively and iteratively creating the framework to develop, review and evaluate policy labs. This stage contributed to the research by demonstrating the need to build impact into lab operations from the outset in order to demonstrate value and enhance resilience. The evaluation included four impact case studies of project interventions, SWOT analysis of the operating model, leadership, processes, methods and people skills as well as a series of recommendations for enhancing iLab’s operations. A number of the recommendations that were made directly relate to the Lab Proposition Framework including having a clear offer for clients, developing selection criteria for projects, conducting a skills audit of lab staff, building capacity for the innovation methods among the wider department and civil service, adapting financing models to ensure resilience and engaging externally to create a community of practice.

Stage 3: Through capacity building initiatives with HMRC Digital and iLab opportunities emerged to engage them more closely in the AHRC Fellowship and to conduct two one-month immersive residencies to understand the drivers and barriers facing labs. The collaboration with HMRC Policy Lab took place in November 2017 in London while the one-month residency on a policy project brokered through iLab took place in September 2018 in Belfast. Through immersive experiences with the two labs a series of thematic drivers and barriers to the emergence, monitoring and on-going assessment of labs were developed. This stage was an important part of the design research approach iteratively constructing, deconstructing and testing assumptions and ultimately refining and validating emerging ideas. With unparalleled access to lab heads it was an opportunity to sense-check the emerging typology and framework to ensure they were fit for purpose and corresponded to lab needs. Identifying the different and evolving finance models and their associated strengths and weaknesses led to a more in-depth examination of how the operating models of labs have emerged and changed. The investigations from Policy Lab, HMRC Policy Lab and iLab informed a set of questions that required framing as part of work to establish HMRC Policy Lab. From the experience with labs a series of pertinent questions emerged, which were relevant for developing HMRC Policy Lab including: What is the vision for the lab? What is the role of the lab in the wider organizational transformation? How can the lab demonstrate impact and value? Is there a clear “offer” for lab clients? Does the lab offer training as well as projects? What are the main innovation methods adopted by the lab? Do lab staff have the right skills or are there gaps? How can the lab build capacity for the approaches across the wider department? How do potential clients hear about the lab? What is the user journey? What is the selection criteria for projects? How does the lab engage externally with the public, if at all?

Stage 4: The aforementioned questions were used to inform the structure for collaboratively developing HMRC Policy Lab and exploring the feasibility of a Welsh Government Innovation Lab. The HMRC Policy Lab workshop took place in December 2017 and the participation was managed by the head of the lab and included representatives from HMRC, Her Majesty’s Treasury, the Home Office and the Department for Work and Pensions (n35). This was the first time that the emerging framework was put to the test to establish a lab. The workshop involved three hands-on exercises (1) Mapping the HMRC Policy Lifecycle; (2) Exploring the opportunities and obstacles to HMRC Policy Lab and (3) Developing the HMRC Policy Lab proposition. The first exercise involved visually mapping the policy cycle and identifying where the lab could add value to the policy process. Based on the HMRC Policy Lifecycle, in small groups, participants explored the opportunities and obstacles to expanding HMRC Policy Lab. The exercise enabled an identification of the potential pitfalls as well as where the Lab could meaningfully enhance policy impact. The third exercise of the day focused on collectively defining the operating conditions of HMRC Policy Lab by brainstorming ideas around the Lab’s proposition statement, the skills people would need, the Lab’s offering as well as the selection criteria for projects. The workshop acted as a springboard for consolidating the concept of HMRC Policy Lab and generating wide engagement and support for its activities. Based on the insight gathered by participants, a series of recommendations were made for enhancing the impact of HMRC Policy Lab, which were provided to the lab head. This workshop was subsequently refined and replicated with the Permanent Secretary’s Group to explore the feasibility of a Welsh Government Innovation Lab. This workshop took place in December 2018 in Cardiff with 18 participants. The Welsh Government workshop was an opportunity to further test and refine the framework and questions for defining a proposition or offer for labs.

Stage 5: Having iteratively developed and tested the typology and framework with a number of different labs – national and regional – there was a need to gain broader input from other labs in order to validate the outputs. As such, the author organized a workshop called “Lab Evolutions” in November 2018 co-hosted by Policy Lab in the Cabinet Office Sky Room. The workshop involved 19 participants from seven policy labs or UCPD teams (Policy Lab, iLab, HMRC Policy Lab, Ministry of Justice User-centered Policy Design Team, Department for Work and Pensions Policy Exploration Team, Department for Education Teachers Policy and Service Design Team as well as Welsh Government Innovation Lab). The session began with a labs showcase with each lab presenting a design for policy intervention, sharing good practices and providing insights on how the lab may have evolved. The main workshop was composed of three exercises (1) exploring the drivers and barriers to the expansion and consolidation of labs; (2) mapping the policy process and where design can add value; and (3) deconstructing and reconstructing the Lab Proposition Framework. The first exercise involved sharing baseline data from labs around the rationale for establishing the lab, their dominant innovation methods, how practices have evolved and other comparators such as number of staff. This exercise was conducted by each lab team then the labs were mixed up into different groups to enable more fruitful exchange and collaboration. The second exercise involved mapping and validate the policy process, where design can add value and specifically what design tools the labs use at different stages of the policy cycle for their interventions. The third exercise involved a question sorting exercise where a set of questions were provided to labs and they had to sort them thematically and allocate a thematic heading. The questions included those questions mentioned early around establishing, reviewing and evaluating labs. The purpose of this exercise was to validate the Labs Proposition Framework.

The outcome from the above five-stage process was the Typology and Framework involving iLab, Policy Lab, HMRC Policy Lab and Welsh Government Innovation Lab in more in-depth ways as well as validating the approaches in a more light-touch way with MoJ UCPD Team, DWP Policy Exploration Team, DfE Teachers Policy and Service Design Team.

4. A typology of policy lab financing models

In the UK, policy labs operate at multiple levels of governance – local and city (for example, Bexley Innovation Lab), regional (Northern Ireland Innovation Lab and Welsh Government Innovation Lab), national (Policy Lab and HMRC Policy Lab) and there is even a supranational lab (EU Policy Lab). The distinction is useful for “understanding the degree of influence and scale” (Bason and Schneider Citation2014, 35). Speaking at the Lab Connections conference hosted by the EU Policy Lab, Vincent (Citation2016) asserted that there is no blueprint for Labs: “Let’s forget the McDonald’s vision for Labs. They are all different depending on the local culture. There is no blueprint.” Many of the UK Labs are in their fourth, fifth or sixth year of operation, how have the operating models of policy labs evolved?

While MindLab (2001–2018) in Denmark was seen as the early trail blazer or archetype for labs across Europe, Policy Lab in the Cabinet Office was the pioneer in the UK. Established under the Open Policy-making agenda, Policy Lab brings “people-centered design approaches to policy-making” through the triumvirate of design, data and digital. Between 2014 and 2016 Policy Lab led 12 large projects and involved 4,000 civil servants in projects, workshops and training with a budget of approximately £800,000 (Whicher Citation2017, 30). Also in 2014, the Northern Ireland Department of Finance established the Northern Ireland Public Sector Innovation (iLab). iLab aims “to improve public services and policy by creating a safe space to co-create ideas, test prototypes and refine concepts with citizens, civil servants and stakeholders” (Whicher Citation2017, 6). Similarly, in its first 2 years, iLab led 18 projects with a budget of approximately £700,000 focused on a wide range of service and policy challenges. The challenges ranged from improving the use of data analytics within the government and reviewing business rates to encouraging people to pay court fines and optimizing how patients manage their medication. In September 2016, the author was commissioned to perform an evaluation of iLab’s activities as well as its governance including its leadership, operating model, methods and capacity (Whicher Citation2017; Whicher and Crick Citation2019). Over the years, demand for Policy Lab and iLab services has grown and the budgets and operating models have evolved. Based on interviews conducted with Policy Lab and iLab on how they have evolved, broadly, there are four main financing models for UK labs with an emerging fifth model:

Sponsorship model – Lab receives a top slice of funding from one or multiple government departments.

Contribution model – Lab receives sponsorship but also recovers a proportion of implementation costs from clients.

Cost Recovery model – Lab recovers all costs from projects on a not-for-profit basis or may charge a small administration fee.

Hybrid model – Lab benefits from multiple sources of funding such as sponsorship, charging for projects as well as collaborative, research or knowledge exchange funding.

Consulting model – Lab operates like an internal consulting function charging for projects with a commercial margin in order to grow the labs operations (hypothetical model).

A lab’s journey through the financing models might start with sponsorship, where the team is 100% funded by one or multiple government departments. After a year or two when the lab has begun to build credibility, it may start to charge clients a proportion of the costs of projects (such as 50%) in a Contribution model while still receiving sponsorship from the host department(s). Once it has established legitimacy after 2–3 years, a lab might be able to charge the full cost of projects on a not-for-profit basis in Cost Recovery model. At this point it might start to look for additional collaborative funding sources in a Hybrid model. The Hybrid model combines different models including sponsorship, commercial income and collaborative funding such as public–private partnerships, knowledge exchange initiatives and European funding. Some UK labs are now starting to transition to a Consulting model where they still benefit from mix income sources like collaborative funding but they have also build in a profit margin to reinvest in expanding the operations of the lab ().

Table 1. Overview of a regional, national and supranational lab.

The resilience of the two UK labs lies in the experimental way that the operating models have developed organically through a continuous learning and credibility building process. Policy Lab was initially sponsored by 17 central government departments, who contributed in cash or kind to the lab’s first year budget of £350,000. This budget covered staff salaries, project costs and consultancy. In the second year, the Lab asked for a smaller contribution from departments, but began charging for some projects. The total budget in the second year was just under £450,000. By its third year it had transitioned to a Cost Recovery model servicing central government departments on a not-for-profit basis. Emerging from its experimental phase, Policy Lab was able to consolidate and enter a new stage of governance. Although in early 2020 Policy Lab operated a Cost Recovery model, it is conceivable in the future that they could transition to a Consulting model building in a commissioning fee of 10–30% to enhance lab operations. Dr Andrea Siodmok leaving Policy Lab in early 2020 may expose Policy Lab without the stability of her longstanding leadership. In her words (Siodmok Citation2020):

[Policy Lab] has grown from simply being an idea – a single line in the Civil Service Reform plan – to becoming a vibrant, multi-disciplinary innovation team of fifteen experts applying deeply human insights and innovative tools to support policy-makers across the system. At last week’s count the Lab had delivered 104 projects supporting the Prime Minister, government departments and external partners.Footnote4

A further change also took place when Policy Lab moved from the Cabinet Office to the Department of Education to be closer to the Policy Profession but still retaining its cross-government brief. It is not uncommon for successful initiatives within the Cabinet Office to be moved or even spun out of government such as the Behavioral Insights Team.Footnote5

iLab also began life with a Sponsorship model funded entirely by its host the Department of Finance with a set up fund of £350,000 but by 2018, it had transitioned to a Contribution model with the majority of its funding still from its host but it also recovered around 50% of the cost of projects from clients. The intervention rate also increased over the years so that by 2020, iLab was recovering 100% of the costs of projects. However, in 2018, iLab also began to collaborate on a European funded project called User Factor,Footnote6 which constitutes a transition to a Hybrid model as funding is still derived from its host department, it charges for projects and it also benefits from collaborative funding. For iLab, it was important for these transitions not to be undertaken too quickly so as to jeopardize the potentially fragile modus operandi of the Lab. Now, for the Head of iLab, one of the challenges will be ensuring that the lab is “not a casualty of COVID cost savings.” Advocates of policy labs contend that design for policy is as relevant, if not more so, in the context of COVID-19 because of the need for prototyping policy at pace. However, there is also a need to demonstrate the impact of policy labs and design for policy in this brave new world and gain wider credibility across the UK Policy Profession if the approaches are to become more mainstream in the UK.

It should also be acknowledged that the distinctions between these models are blurring and that a lab might not fully fit within a single model. For example, before it closed, MindLab in Denmark could be considered a Hybrid model operating predominantly a Sponsorship model with elements of a Consulting model as it was 80% financed by three central government departments and one local municipality but also with 20% commercial income ().

Table 2. Strengths and weaknesses of the operating models.

Each model has its associated strengths and weaknesses. For example, the Sponsorship Model hinges on the regular renewal of a contract across multiple government departments (often annually). With the Sponsorship model there is a risk that if key advocates (like the Permanent Secretary’s Group) withdraw their support that the Lab will close its doors or be spun out of government. The Contribution and Cost Recovery models hinge on a highly effective and efficient work programme and continuous pipeline of projects as well as crucially a strong reputation. These models provide flexibility to service a range of clients enabling labs to develop selection criteria to ensure “client readiness” for user-centered design approaches and affords relative freedom to pursue higher value, strategic projects. The Hybrid model spreads risk through a portfolio approach across multiple sources of income including sponsorship, commercial and collaborative funding. It seeks to emulate the Innovate UK “Catapult” model where one third of income is underpinned from core public sector funding (Sponsorship), one third from commercial services (Consulting) and one third from collaborative knowledge exchange or public-private partnerships. Income generated from multiple sources protects the lab from cost savings exercises however, again it requires effective leadership and an efficient project pipeline to manage peaks and troughs. The Consulting model enhances resilience through income generation but relies on an established track record, strong leadership and senior civil servant endorsement. Although ultimately nothing can fully shield a policy lab from political decision-making, operating a Consulting model can enhance the resilience in light of constricting public sector budgets. It is important for labs to practice what they preach and apply design methods to continuous reflection on their own operation. In the aftermath of COVID-19, it will be timely for labs to once again reflect on their journeys moving forward.

5. Lab Proposition framework for establishing, reviewing and evaluating policy labs

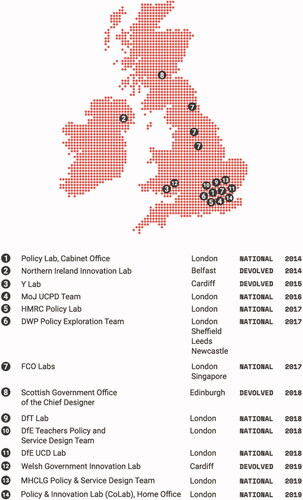

The number of UK policy labs and user-centered policy design teams has grown significantly since 2014 when Policy Lab in the Cabinet Office and the Northern Ireland Innovation Lab (iLab) in the Department for Finance were established. There are now about 4000 designers working in central government – mostly interaction and service designers but a growing number of “policy designers” and even government's first “speculative designer.” By 2020, there were around 10 policy labs or user-centered policy design teams in central government (see : Map of Policy Labs and UCDP teams 2020) and three at devolved levels in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. However, a number of labs at national and particularly local level have closed such as the Department for Trade and Investment’s UKTI Ideas Lab (2014–2017) and local initiatives in Cornwall, Kent, Leeds, Monmouthshire, Shropshire, Surrey, Wakefield and Wolverhampton, among others (Fuller and Lochard Citation2016, 4–5). Why have policy labs and UCPD teams been more successful at national level than local level? Funding cuts no doubt play a significant role but this question requires further investigation. What is the lifecycle of a policy lab? How might we enhance the resilience of labs?

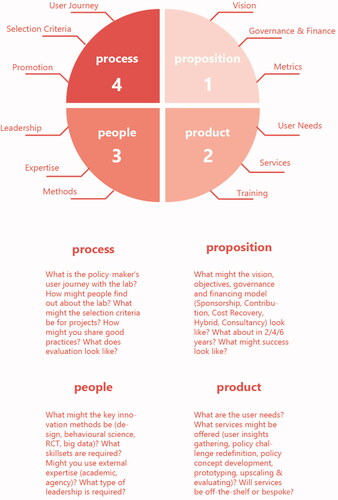

In 2017, the author was asked to support HMRC Digital in establishing HMRC Policy Lab and undertook a capacity building exercise in design for policy with a cohort of 25 civil servants. Although it is not possible to share details specifically of the HMRC Policy Lab case based on this intervention as well as a subsequent intervention with the Welsh Government, a framework for establishing, reviewing and evaluating policy labs and UCDP teams was developed. It is important for labs to practice what they preach and apply design approaches to continuously reflecting on their work. Policy labs can be vulnerable to political ebbs and flows and changing budgets, leadership and contexts and thus it is important to establish credibility, foster resilience, create a foundation for legitimacy and evaluate impact. At its core the framework for establishing, reviewing and evaluating policy labs has four components – Proposition, Product, People and Process (see ). This is exploratory research was developed inductively through interviews, workshops and immersive work with policy labs. Taking a design approach, this model has been iteratively developed and tested but still remains at its early stages of development and is intended as a provocation to encourage more researchers to develop models to develop, monitor and evaluate policy labs.

Proposition refers to the vision, governance, finance models and metrics of success for the lab. Policy labs tend to transition through a number of financing models (see Typology of Policy Lab Financing Models) from when they are first established tending to be entirely sponsored by one or more government departments to when they begin to charge for projects perhaps first asking clients to make a contribution and subsequently recovering the full cost to when they might benefit from multiple income sources. It is important for labs to develop a longer-term vision in order to foster resilience and legitimacy. Very often, labs are established as a one year experiment and thus after their first year of inception should seek to develop a forward-thinking vision that is continuously revisited each year in light of changing priorities and environments. It is also important for labs to understand their role in the wider departmental transformation – such as under the digital agenda. It can also be challenging to set concrete key performance indicators (KPIs) for Labs. On the one hand, setting stringent and quantitative KPIs reinforces old bureaucratic practices but on the other hand, without KPIs labs can drift from their core raison d'être. Further research is required to understand whether indicators such as “enhanced user satisfaction” are sufficient for protecting labs against the changing political tides. For this stage of the Proposition Framework, labs could explore the following questions: What is the vision for the lab now and moving forward? What is the governance structure and financing models? How does the lab contribute to the wider transformation agenda for the department? What does success look like? How can the lab demonstrate impact and value?

Product refers to the service and training offer and how that corresponds to user needs. As the lab begins to develop a “market” for their services they may transition from bespoke projects for each client to a set of “off-the-shelf package products.” Examples of off-the-shelf products might be: (1) supporting teams to conduct user research and redefine the policy challenge, (2) engaging the public in co-designing policy concept, (3) prototyping and iterating policy options with users, (4) implementing more meaningful public consultation, (5) piloting, upscaling, monitoring and evaluating implementation. It is common for “clients” engaging with labs to not commission an end-to-end policy process from the outset rather to take projects step by step. A clear “menu” of services offered enables potential clients to see where design for policy approaches can add value at different stages of the policy cycle. It is also crucial for labs to embed the various innovation and design methods beyond the walls of the lab. Change management of any sort on an institution scale is challenging. It is important to move beyond ad hoc training and design sprints to fostering an agile, iterative and co-creative mindset within government. This can be done through integrating design methods into accredited civil service training modules and leadership initiatives as well as identifying champions. Questions for labs to explore include: What are the user needs? Is there a clear “offer” for potential clients? Will labs offer capacity building and mentoring?

People refers to the methods, skillsets, expertise and leadership required. Policy labs use a range of innovation methods including, but not limited to, design, big data, behavioral insights, co-production, ethnography, system dynamics modeling, lean and randomized control trials. At least in the UK, the dominant approaches are the triumvirate of design, data and digital. In light of further austerity measures in the aftermath of COVID-19 it is likely that there will be a recruitment freeze within the civil service. Sometimes lab staff are redeployed staff from other areas of the business who then procure external design expertise from agencies or academia. Very often labs contract out the design expertise to agencies, consultants or academics in the early days of the lab and seek to internalize that expertise as the lab gains notoriety and demand grows for lab services. At the point where external consultants leave and a lab seeks to build its internal capacity it is vital for a structured knowledge transfer to take place between the consultants handing over to the internal staff. As part of the process, labs could conduct a skills audit of their teams to ascertain if they have the appropriate policy, design and digital skills or whether there are gaps. It is important to have a multidisciplinary team with experts in policy and service delivery processes but also experts in the innovation or design methods such as service designers, policy designers, user researchers and interaction designers. Questions that labs might like to explore include: What are the key innovation methods offered by the lab? Do lab staff have the right skills or are there gaps? How might knowledge transfer be managed from external consultants to internal lab members? How can the lab build capacity for the approaches across the wider department?

Process refers to the user journey of the policy-maker engaging with the lab, the selection criteria for projects and how good practices will be shared. Design can be a difficult concept for policy-makers to grasp so there should be a clearly articulated user journey to enable policy-makers that are new to the approaches to understand the process. A key insight that emerged from the enquiry is the need for labs to develop selection criteria for projects. There is a temptation for labs to take on any project that comes their way. However, with limited capacity labs should be more selective about the projects they implement so as not to limit their potential by only dealing with the low hanging fruits. Some policy teams might see labs as a spare pair of hands, particularly in the context of restricted budgets, rather than an opportunity to develop new best practice and showcase results. As such, labs might consider exploring the following questions when defining selection criteria: Is the project consistent with the wider transformation agenda? Is the project of strategic importance to the department? Does the Sponsor have the necessary personal commitment, position and authority to implement outcomes from the lab? Does the Sponsor have resources for prototyping, testing and upscaling? Is there a reputational risk for the lab? What is the likelihood of achieving a consensus in the project that will result in realizable benefits? Is the Sponsor potentially prepared to share the results with the wider department or even make the results public? It is also vital to create a community of advocates in order to enhance credibility and embed the approaches beyond the lab. Labs tend to be a “safe space to innovate” and therefore operate behind closed doors; however, in order to share the approaches more widely labs should evaluate their interventions and share case studies and good practices. There is a need to “demystify” labs. A number of UK labs have active blogs sharing lessons from projects and contributing to a theoretical grounding – like Policy Lab – but a number of labs also work with very sensitive issues and do not share project examples with the wider community of practitioners – like HMRC Policy Lab. Questions for examination include: How do potential clients hear about the lab? What is the user journey? What is the selection criteria for projects? How does the lab engage externally with the public, if at all?

6. Conclusion

Policy labs and user-centered policy design team (UCPD) are multi-disciplinary government units experimenting with a range of innovation methods, including design, to collaboratively engage citizens in service and policy development. Design for policy is a creative, user-centered approach to problem-solving engaging users, stakeholders and delivery teams at multiple stages of the policy process. However, it remains an emerging domain where government practice is well in advance of academic theory. Since 2014, there has been a proliferation of policy labs at local, regional and national levels in the UK. However, it should also be noted that there has been a waxing and waning of labs in the UK local and city government over the years. In recent years, UK labs have expanded the repertoire of methods and tools in their toolboxes but the dominant approaches are “anchored in the trio of digital, data and design” (Williamson Citation2015, 258; Siodmok Citation2014, 25). Through interviews, workshops and immersive residencies as part of an AHRC Fellowship called People Powering Policy, a framework has been iteratively created to develop, monitor and evaluate policy labs and user-centered design teams exploring Proposition, Product, People and Process. Proposition refers to the vision, governance, finance models and metrics of success for the lab. Product refers to the service and training offer and how that corresponds to user needs. People refers to the methods, skillsets, expertise and leadership required. Process refers to the user journey of the policy-maker engaging with the lab, the selection criteria for projects and how good practices will be shared. A Typology of Policy Lab Financing Models was also developed outlining four main models for UK labs operations as well as an emerging fifth model – Sponsorship (funding from one or multiple departments), Contribution (labs recover part of the costs of projects), Cost Recovery (labs charge for projects on a not-for-profit basis), Hybrid (labs benefit from multiple income sources such as Sponsorship, charging and knowledge exchange funding) and Consultancy (labs charge a consultancy rate with a profit margin to expand operations). Labs and UCPD teams should practice what they preach and use design approaches to continuously review and innovate their models. This is particularly pertinent in the context of COVID-19, which has necessitated rapid, iterative policy-making with even shorter decision-making times. To mitigate against the risks of labs falling “casualty” to cost-saving exercises, labs should review how they add value to policy-making using the Labs Proposition Framework and how to enhance their financial resilence through adapting their financing models as per the typology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

3 Additional information about the project can be found at: https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=AH%2FP009263%2F1 and https://www.pdr-consultancy.com/work/people-powering-policy

6 User Factor is an Interreg Atlantic Area funded project with 8 partners led by PDR at Cardiff Metropolitan University operating from 2018 to 2021 worth €2 million to explore next practice in design support programmes to support SMEs to use service design. http://userfactor.eu/

References

- Amatullo, M. 2014. “The Branchekode.dk Project: Designing with Purpose and across Emergent Organizational Culture.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Bason, C. 2014. “Introduction: The Design for Policy Nexis.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Bason, C., & Schneider, A. (2014) ‘Public Design in Global Perspective: Empirical Trends’, In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Blessing, L., and Chakrabarti, A. (2009). ‘DRM, a Design Research Methodology’. Springer-Verlag London, UK.

- Fuller, M., and A. Lochard. 2016. “Public Policy Labs in European Union Member States.” Report prepared for EU Policy Lab, European Joint Research Centre, EUR28044. doi:10.2788/799175.

- Halse, J. 2014. “Tools for Ideation: Evocative Visualization and Playful Modelling as Drivers of the Policy Process.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Her Majesty’s Treasury. 2018. The Green Book. Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation. London, UK: HM Treasury.

- Howlett, M. 2014. “From the ‘Old’ to the ‘New’ Policy Design: design Thinking beyond Markets and Collaborative Governance.” Policy Sciences 47 (3): 187–207. doi:10.1007/s11077-014-9199-0.

- Jegou, F., R. Thevenet, and S. Vincent. 2014. “Friendly Hacking into the Public Sector: (Re)Designing Public Policies within Regional Governments.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Junginger, S. 2012. “Public Innovation Labs – A Byway to Public Sector Innovation?” In Highways and Byways to Radical Innovation, edited by J. Christensen and S. Junginger, 1st ed. Kolding: University of Southern Denmark & Design School.

- Junginger, S. 2014. “Towards Policymaking as Designing: Policymaking beyond Problem-Solving and Decision-Making.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Kimbell, L., and J. Bailey. 2017. “Prototyping and the New Spirit of Policymaking.” CoDesign International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 13 (3): 214–226.

- Maffei, S., F. Leoni, and B. Villari. 2020. “Data-Driven Anticipatory Governance. Emerging Scenarios in Data-for-Policy Practices.” Policy Design and Practice 3 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1080/25741292.2020.1763896.

- Nesta. 2015. ‘World of Labs.’ Accessed 04 January 2018 https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/world-labs

- Puttick, R., P. Baeck, and P. Colligan. 2014. “i-Teams. The Teams and Funds Making Innovation Happen in Governments around the World.” Nesta and Bloomberg Philanthropies Report, London, UK.

- Sanders, E., and P. J. Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” Codesign 4 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/15710880701875068.

- Siodmok, A. 2014. “Designer Policies.” RSA Journal 4: 24–29.

- Siodmok, A. 2020. “Lab Long Read: Human-Centred Policy? Blending ‘Big Data’ and ‘Thick Data’ in National Policy.” Open Policy Blog, 17 January 2010. https://openpolicy.blog.gov.uk/2020/01/17/lab-long-read-human-centred-policy-blending-big-data-and-thick-data-in-national-policy/

- Staszowski, E., S. Brown, and B. Winter. 2014. “Reflections on Designing for Social Innovation in a Public Sector: A Case Study in New York City.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Taylor, M. 2014. “The Policy Presumption.” RSA Journal 4: 10–15.

- Vincent, S. (2016) ‘La 27e Region’, Labs Connection conference hosted by EU Policy Lab, 17 October 2016.

- Whicher, A. 2017. “Evaluation of the Northern Ireland Public Sector Innovation Lab.” Independent Report Commissioned by the Northern Ireland Department of Finance, Produced by PDR – International Design and Research Centre, Cardiff Metropolitan University, UK.

- Whicher, A. 2020. “Challenges of the Future Design & Public Policy.” AHRC Design Fellowship Report, Cardiff, June 2020.

- Whicher, A., and T. Crick. 2019. “Co-Design, Evaluation and the Northern Ireland Innovation Lab.” Public Money & Management 39 (4): 290–299. doi:10.1080/09540962.2019.1592920.

- Williamson, B. 2015. “Governing Methods: Policy Innovation Labs, Design and Data Science in the Digital Governance of Education.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 47 (3): 251–271. doi:10.1080/00220620.2015.1038693.