Abstract

“Impact” describes how research informs policy and societal change, and “impact agenda” describes strategies to increase engagement between research and policymaking. Both are notoriously difficult to conceptualize and measure. However, funders must find ways to define and identify the success of different research-policy initiatives. We seek to answer, but also widen, their implicit question: in what should we invest if we seek to maximize the impact of research? We map the activities of 346 organizations investing in research-policy engagement. We categorize their activities as belonging to three “generations” fostering linear, relational, and systems approaches to evidence use. Some seem successful, but the available evidence is not clear and organizations often do not provide explicit aims to compare with outcomes. As such, it is difficult to know where funders and researches should invest their energy. We relate these findings to studies of policy analysis, policy process research, and critical social science to identify seven key challenges for the “impact agenda”. They include: clarify the purpose of engagement, who it is for, if it is achievable in complex policymaking systems, and how far researchers should go to seek it. These challenges should help inform future studies of evidence use, as well as future strategies to improve the impact of research.

Introduction

UK research bodies face a major “impact agenda” dilemma. They must invest in the most successful types of research-policy engagement initiative despite facing uncertainty about the evidence for their success and ambiguity about what success might look like. Impact is notoriously difficult to define, conceptualize, measure and evaluate. For most funders, the “impact agenda” has meant thinking about how to measure the impact of research through metrics like citations and in frameworks that capture and monitor impact. It has driven the expansion of national research evaluation activities, such as the Research Excellence Framework in the UK and Excellence in Research for Australia (Williams and Grant Citation2018). While research evaluation has been the key way in which researchers and funders have thought about this dilemma, impacts have rarely been assessed using robust social research methods (Smith and Stewart Citation2017). Recent scholarship has highlighted the need for a more robust approach, providing insight into the contexts of impact in the social sciences and humanities and the gendered and racialised nature of research evaluations (Bastow, Dunleavy, and Tinkler Citation2014; Chubb and Derrick Citation2020). Scholars have also made proposals for improved ways to think about impact beyond citations, demonstrating growing methodological pluralism and a shift from narrow instrumental measures (Gunn and Mintrom, Citation2017; Derrick Citation2018; Ravenscroft et al. Citation2017; Pederson, Grønvad, and Hvidtfeldt 2020). It is no longer enough to tell good stories about individual projects and researchers. In this context, funders must encourage research-policy engagement to help maximize the “impact” of research, and assess current evaluation evidence to identify the most promising approaches (Oliver, Kothari, and Mays Citation2019). In this paper we evaluate that evidence base and relate the findings to key challenges to the impact agenda.

First, we identify and analyze the international evidence on the impact of 346 organizations investing in research-policy engagement. We use a tripartite categorization based on “generations” of thinking about the relationship between evidence and policy. Linear strategies treat knowledge as a product to be made by researchers and supplied to policymakers, focusing on the communication of research. Relational strategies foster collaboration between researchers and policymakers to produce usable knowledge. Systems strategies seek to maximize evidence use by understanding and responding to dynamic policymaking systems (Best and Holmes Citation2010). For each approach the evidence of impact on policy and practice is unclear.

Second, we draw on insights from policy analysis, policy process research, and critical social science to clarify future choices regarding research-policy engagement schemes. We provide examples of where scholarship can support the design of engagement opportunities, the establishment of more realistic expectations for researcher practices, and more informed engagement with the politics of research impact. Learning from policy studies can help us identify the practical constraints to impact in complex policymaking systems. It can also help us reflect on the tradeoffs between impact aims and values, such as to focus on efficient ways to make a return on funder investment or equitable ways to invest in researchers and policy outcomes. We identify seven key challenges for researchers and funders, including: (1) learn from existing systems and practices, (2) clarify who engagement is for, (3) define the policy problem to which impact is a solution, (4) tailor practices to “multi-centric” policymaking, (5) clarify the role of researchers, (6) consider what forms of evidence are valuable and credible, and (7) establish realistic expectations for engagement.

The international experience: three generations of research-policy engagement initiatives

We used a systematic mapping approach to identify organizations that aim to improve academic-government engagement (see Oliver, Kothari, and Mays Citation2019 for a full list). We conducted a systematic search for UK, EU and international research-policy engagement strategies, using website searches and documentary analysis. We aimed to identify any formal or funded activity or practice, in any country, at any time, which attempts to promote or improve research-policy engagement. This search was supplemented by interviews with research-to-policy experts (n = 8), a workshop with over 35 representatives from UK policy and research organizations, intermediary organizations, universities, learned societies and research funders, and an online survey (sent to a 20% sample of organizations within key stakeholder groups). To date, we have identified 346 organizations in 31 countries. This data allows us to put together an empirical picture of the research-policy engagement landscape, and to develop insights of value to other countries fostering research and policy systems (see Oliver et al. Citation2021).

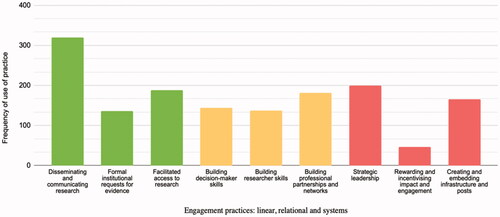

To categorize these activities, we use Best and Holmes (Citation2010) framework to identify linear, relational and systemic approaches, and Langer, Tripney, and Gough (Citation2016) to map key practices. Linear practices are (1) dissemination and communication, (2) responding to formal evidence requests, (3) facilitating access to evidence. Relational practices are (4) building policymaker skills and (5) building researcher skills, (6) building professional partnerships. Systems practices focus on (7) fostering leadership, (8) rewarding and incentivising impact and engagement, and (9) creating and embedding infrastructure. illustrates how frequently the 9 practices were employed (note that many employed more than one). There is a strong focus on dissemination and communication, but many approaches attempt to develop multiple routes to impact and some combine elements of linear, relational, and systems approaches.

Figure 1. What practices do research-policy engagement approaches use? Source: author image adapted from Best and Holmes (Citation2010).

Linear approaches

Linear approaches push evidence out from academia (Dissemination and communication) or pull evidence into government (through formal evidence requests, or facilitating access). Examples of “push” include the writing and dissemination of policy briefs, often based on evidence syntheses (for example, Partners for Evidence-driven Rapid Learning in Social Systems funded by Hewlett and IDRC), and the What Works Network repackaging of research to increase its appeal and accessibility. In line with past studies (Powell, Davies, and Nutley Citation2018), we find that most activity and investment focuses on such practices. However, evaluations show that disseminating evidence alone does little to improve use, failing to address practical, cultural or institutional barriers to engagement (Langer, Tripney, and Gough Citation2016).

Examples of “pull” include formal institutional mechanisms such as science advisory committees, or requests for evidence issued through legislatures and consultations. Learned societies often play a key role in coordinating these responses. Pull approaches also facilitate access to research, by improving the commissioning of research or supporting the co-creation of research or policy briefs. For example, the Sax Institute (Australia) has developed intelligent online tools to support commissioning and help government departments set up research and evaluation projects. The details and impacts of these practices have not been systematically documented or coordinated. There is some case-based evidence that rapid response services and supported commissioning are viewed as valuable by policymakers (e.g. What Works Network Citation2018; Mijumbi-Deve et al. Citation2017). However approaches focused on improving the availability of evidence are unlikely to be sufficient to improve evidence use within real-world policymaking environments (Cairney Citation2019).

Relational approaches

Relational approaches acknowledge that policymakers and researchers have different skills and expertise. They focus on building bridges to share knowledge and promote mutual understanding. Skills-building practices such as the University of Cambridge Center for Science and Policy Fellowships or the Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology’s Effective Scrutiny course, focus on policymaker research skills. Complementary schemes to build researcher engagement skills are supported through fellowships, training or secondment opportunities. Many are aimed at early career researchers and are mostly between 3-12 months. Relatively few are directly supported by funders of research. Existing training is poorly-evidenced, and few studies examine research-policy training as part of wider evaluation.

Relational approaches also seek to build professional partnerships and networks based on long-term, non-transactional joint working to sustain trust, shared priorities and good relationships. Examples include the African Evidence Network (AEN) and the Alliance for Useful Evidence (UK). There is some evidence that networks provide a promising approach to building learning (Boaz et al. Citation2015), although the wider impacts of network initiatives on policymaking are not well-understood. Formalized partnership approaches, in which research and policy organizations agree on and deliver on a shared work programme, are still rare in UK policy. Frequently-cited examples are the practice-oriented Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Heath Research (CLAHRCs) first funded in 2008 and now renamed ARCs (Applied Research Collaborations), and the UK’s Department of Health Policy Research Units. In general, existing evaluations do not convincingly demonstrate that the benefits outweigh the costs (Oliver, Kothari, and Mays Citation2019), although many continue to assert their value, particularly at the practice level (Williams et al. Citation2020). These collaborations highlight debates over what counts as evidence, how other forms of knowledge should be valued and integrated, and issues of power and ownership (Boaz and Nutley Citation2019). However, relational approaches are generally under-theorized (Boaz and Nutley Citation2019), meaning there is a lack of clarity about how participants address these issues.

Systems approaches

Systems approaches, drawing on ideas from complexity theory, aim to provide support for engagement in complex policymaking environments. They address the most commonly documented barriers and facilitators to engagement, including contact, collaboration, researcher and policymaker skills (Oliver et al. Citation2014). Many describe an “ecosystem” of relationships between the researchers, funders and policymakers involved in the production and use of evidence.

The most frequently-reported practice is the promotion of strategic leadership, through convening or advocacy to champion evidence use and engagement. For example, the US Bipartisan Policy Center’s Evidence Project worked successfully on planning, convening and advocating ways to implement the recommendations of the US Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking (2017). Rewarding and incentivising impact and engagement between research and policy may also contribute to a more positive system. Examples include the UK Economic and Social Research Council’s Celebrating Impact Prize or the US Federation of American Scientists Public Service Award. Systems approaches also focus on creating and embedding infrastructure, such as job posts or roles (e.g. specialist policy engagement teams within universities), processes (such as the UK’s Areas of Research Interest supported by the Government Office for Science), and coordination efforts (such as the EU Scientific Knowledge for Environmental Protection – Network of Funding Agencies programme, 2005-2013, which aimed to improve alignment between policy-funder priorities).

Where it exists, work to evaluate these efforts has focused on “intermediate” or “proxy” outcomes. In environmental science for example Posner and Cvitanovic (Citation2019) document methods used to study “boundary spanning” roles and activities. Studies have aimed to support practitioners to identify and orient toward intended outcomes and goals, and explored the success of boundary spanning in relation to outcomes such as the creation of new relationships in case studies. However, we found few examples of organizations providing practical, enduring, and well-evidenced lessons on how to support systemic work, while many focus on single elements within the research-policy system. In a context where the practices of systemic support are poorly understood, it is hard for organizations to know what success should look like. In general, organizations struggle to conceptualize and design systemic support, and fail to consistently draw on scholarship that can shed light on complex policymaking environments.

What can other organizations learn from this evidence?

Linear, relational and systemic approaches involve different assumptions about how best to improve research impact in policy contexts: improve the communication of evidence, relationships between research and practice, or the systems that constrain and facilitate action (Best and Holmes Citation2010; Boaz and Nutley Citation2019; Caplan Citation1979). They have the potential to complement each other: linear approaches to research dissemination have little impact in the absence of trusted relationships, and the imposition of large-scale infrastructure (such as collaborative funding models) will not work well in the absence of a culture which values and incentivises the production and the use of knowledge. However, we know little about what kinds of knowledge or skills are required to support effective relationships, nor how systems-informed practices facilitate better communication and relationships.

This uncertainty is reflected in our analysis of current initiatives. It reveals a great deal of activity, involving multiple actors with different stakes in work at the interface of research and government. Few practices have been evaluated using robust social science methods, and fewer evaluations are in the public domain. In most cases there is an unclear link between initiatives and a strategy to maximize learning across countries, sectors or fields, and much is based on unclear and untested assumptions. Few initiatives connect the differences between generational approaches to clear choices about where to invest or how to design or evaluate different practices (Boaz and Nutley Citation2019). In the absence of evidence to connect investments to outcomes it seems likely that many initiatives will yield limited and/or poorly understood effects.

Taking forward the impact agenda: insights from policy studies

This problem of uncertainty is exacerbated by a lack of theorization of evidence use. Few organizations draw on insights from policy studies to confront tradeoffs between impact aims and values, or support researchers engaging in policymaking environments. To address this limitation, we draw on insights from three different strands of policy studies (see Cairney Citation2021) to inform the ways in which funders and researchers might foster impact and evaluate engagement schemes.

Policy analysis texts provide step-by-step advice on how to use research to define a policy problem, generate feasible solutions, use values and models to predict and compare their effects, and make a recommendation to a policymaker (Bardach and Patashnik Citation2020; Meltzer and Schwartz Citation2019; Mintrom Citation2012; Weimer and Vining Citation2017; Dunn Citation2017). Studies of policy analysts help us understand the limits to their impact in practice and how they respond (Radin Citation2019; Brans, Geva-May, and Howlett Citation2017).

Policy process research helps identify the limited capacity of policymakers to understand and solve policy problems, and situate researcher-policymaker engagement in a complex policymaking environment over which no one has control (Cairney Citation2020).

Critical policy analysis helps identify the politics of research engagement, in which many debates occur simultaneously:

• Whose evidence counts when defining problems, producing solutions, and predicting their unequal impact (Smith Citation2012; Doucet Citation2019).

• How problems are defined in ways that assign blame to some and support to others (Bacchi Citation2009).

• Who should interpret the meaning of political values, rank their importance, and therefore rank the importance of populations and communities (Stone Citation2012), and

• The extent to which new solutions should reinforce or challenge a status quo that already harms marginalized individuals and groups (Michener Citation2019; Schneider and Ingram Citation1997).

We use these insights to identify seven issues at the heart of future evaluations of impact initiatives, which should be considered by designers, implementers and users of strategies to increase research impact.

Rather than trying to design a new policy impact system, adapt to policy systems and practices that exist

Studies of “evidence based policymaking” (EBPM), from a researcher perspective, tend to identify (a) the barriers between their evidence and policy, and (b) what a better designed model of research production and use might look like (Cairney Citation2016; Oliver et al. Citation2014; Parkhurst Citation2017). Yet, the power to redesign engagement is not in the gift of research funders. Rather, funders can help researchers to adapt to their environments. In particular, policy theories identify a complex policymaking environment in which it is not clear (a) who the most relevant policymakers are, (b) how they think about policy problems and the research that may be relevant, and (c) their ability to turn that evidence into policy outcomes.

In that context, initiatives could help researchers identify relevant policymakers, frame problems in ways that are convincing or persuasive, or identifying opportune moments to try to influence policy (Cairney Citation2019). However, few initiatives are informed by these concerns, and training for researchers draws generally on simplified (linear) models of policy processes that are not informed by an understanding of how policymakers use evidence or make choices.

One option may be to inform initiatives by drawing on the general advice given to policy analysts: consider many possible analytical styles – such as rationalism, argumentation, participation, deliberation, or client-focused - to address (a) the different contexts in which analysts engage, and (b) the highly-political ways in which analysts generate policy-relevant knowledge (Mayer, van Daalen, and Bots Citation2013, 50–55). Although relatively few researchers will see policymakers as their clients, they would benefit from knowing more about how policymakers use evidence. Academic-practitioner exchanges, and insider accounts from civil servants, provide some ways to identify and discuss such insights (Cairney Citation2015; Phoenix, Atkinson, and Baker Citation2019).

Clarify the role of support directed at individuals, institutions, and systems

We can think of research-engagement support in terms of individuals, institutions, or systems, but the nature of each type of support – and the relationship between them - is not clear. In general, support is weighted toward individuals (through training, support in responding to calls for evidence, or funding opportunities). Studies of academic impact and policy analysis share a focus on the successful individuals often called “policy entrepreneurs” (Oliver and Cairney Citation2019; Cairney Citation2018). For Mintrom (Citation2019), they “are energetic actors who engage in collaborative efforts in and around government to promote policy innovations”. Descriptions of policy entrepreneurs are similar to the recommendations generated from the personal accounts of impactful researchers:

(1) Do high quality research; (2) make your research relevant and readable; (3) understand policy processes; (4) be accessible to policymakers: engage routinely, flexible, and humbly; (5) decide if you want to be an issue advocate or honest broker; (6) build relationships (and ground rules) with policymakers; (7) be ‘entrepreneurial’ or find someone who is; and (8) reflect continuously: should you engage, do you want to, and is it working? (Oliver and Cairney Citation2019, 1).

One approach is to learn from, and seek to transfer, their success. Another is to recognize that most entrepreneurs fail, and that their success depends more on the nature of (a) their policymaking environments, and (b) the social backgrounds that facilitate their opportunities to engage (Cairney Citation2021). A focus on praising and learning from successful individuals can reinforce inequalities in relation to factors such as “race” and gender, as well as level of seniority, academic discipline, and type of University.

In that context, the idea of institutionalizing engagement is attractive. Instead of leaving impact to the individual, make changes to the rules and norms that facilitate engagement. However, the ability to set the “rules of the game” is not shared equally, and researchers generally need to adapt to – rather than co-design - the institutions in government with which they engage. This point informs a tendency to describe research-government interactions in relation to an “ecosystem”. This metaphorical language can be useful, to encourage participants not to expect to engage in simple policy processes, and to encourage “systems thinking”. However, there are many ways to define systems thinking, and many accounts provide contradictory messages. Some highlight the potential to find the right “leverage” to make a disproportionate impact from a small reform, while others highlight the inability of governments to understand and control policymaking systems (Cairney Citation2021). These distinctions are crucial to the design and evaluation of systems approaches: do they seek to redesign systems or equip individual researchers to adapt to what exists?

Reduce ambiguity by defining the policy problem to which impact is a solution

Funders of research engagement may produce strategy documents explaining the value of impact, but many of their aims are unwritten, they do not produce clear priorities in relation to all aims, and they are only one contributor to “impact policy” in a wider policymaking system. This outcome requires organizations to clarify their objectives when they seek to deliver them in practice. For example, UK funding bodies may seek to: contribute to specific government policy aims (ESRC Citation2019); foster an image of high UK research expertise and the value of government investment in UK funding bodies; support a critical and emancipatory role for research which often leads researchers to oppose government policy; and, foster an equal distribution of opportunities for researchers (on the assumption that impact success can boost their careers).

If so, they need to anticipate and address inevitable tradeoffs. Practices may appear to succeed on one measure (such as to give researchers the support to develop skills or the space to criticize policy) and fail on another (such as to demonstrate a direct and positive impact on current policy). Or, for example, the largest opportunity to demonstrate visible, recordable, and continuous research impact in the UK is in cooperation with Westminster, but impact on a House of Commons committee is not impact on policy outcomes (Oliver, Kothari, and Mays Citation2019). Direct impact on ministers and civil servants is more valuable but more difficult to secure and demonstrate empirically.

Tailor research support to multi-centric policymaking

Policy process research describes “multi-centric policymaking” in which central governments share responsibility with many other policymakers spread across many levels and types of government (Cairney et al. Citation2019). It results from choice, for example when the government shares responsibilities with devolved and local governments. It also results from necessity, since policymakers can only pay attention to a small proportion of their responsibilities, and they engage in a policymaking environment over which they have limited control. This environment contains many policymakers and influencers spread across many venues.

This dynamic presents the biggest challenge to identifying where to invest or act. On the one hand, it could support researchers engaging with policy actors with a clearly defined formal role, including government ministers (supported by civil servants) and parliamentary committees (supported by clerks). However, most policymaking takes place out of the public spotlight, processed informally at a relatively low level of central government, or by non-departmental public bodies or subnational governments (often delivered by third and private sector organizations). Policy analysts or interest groups deal with this problem by investing their time to identify: which policymaking venues matter, their informal rules and networks, and which beliefs are in good currency. They may also work behind closed doors, seek compromise, and accept that they will receive minimal public or professional credit for their work (Cairney and Oliver Citation2020). Such options may be unattractive to researchers aiming to demonstrate impact, since they involve a major investment of time with no expectation of a payoff (unless funding bodies signal the willingness to take a more flexible approach to documenting impact). Current provision for impact generally fails to address these options and compromises (Murji Citation2017).

Clarify the role of researchers when they engage with policymakers

Policy analysts and academic researchers face profound choices on how to engage ethically, and key questions include:

Is your primary role to serve individual clients or a wider notion of the “public good”?

Should you maximize your role as an individual or professional?

What forms of knowledge and evidence count (and should count) in policy analysis?

Should you provide a clear recommendation? (Cairney Citation2021).

In policy analysis texts, we can find a range of responses, including:

The pragmatic client-oriented analyst focused on a brief designed for them, securing impact in the short term (Bardach and Patashnik Citation2020; Meltzer and Schwartz Citation2019; Mintrom Citation2012; Weimer and Vining Citation2017; Dunn Citation2017).

The critical researcher willing to question a policymaker’s (a) definition of the problem and (b) choice regarding what knowledge counts and what solutions are feasible, to seek impact over the long term (Bacchi Citation2009; Stone Citation2012).

These approaches can produce different investment choices in relation to a huge list of policy-relevant skills (see Radin Citation2019, 48). There are many well-established methods to help answer research questions and we should not assume that one method should be the most valued because it is the most used. A focus on a too-small collection of skills or perspectives would diminish the potential value of University engagement with government, and exclude many researchers with skills in other areas. In that context, some US examples highlight the role of diverse skills, including in co-design (the Research and Practice Collaboratory), advocacy (the Center for Child Policy and Advocacy), and community organizing (the Institute for Coordinated Community Response). In terms of a values-based approach, the UK Grantham Institute aims to prepare scholars for critical engagement through their training programme, supporting PhD students to become expert environmental activists.

Establish the credibility of research through expertise and/or co-production

Attempts at collaboration between researchers and policymakers highlight how power and inequality function within knowledge production and use (Boaz and Nutley Citation2019). In particular, expectations for “evidence based” or “coproduced” policies are not mutually exclusive, but we should not underestimate major tensions between their aims and practices, in relation to questions such as:

How many people should participate (a small number of experts or large number of stakeholders)?

Whose knowledge counts (including research, experiential knowledge, practitioner learning)?

Who should coordinate the “co-production” of research and policy (such as researchers leading networks to produce knowledge to inform policy, or engaging in government networks)? (Cairney Citation2021).

Researchers may also engage with different models of evidence-informed governance, such as when central governments (a) try to roll out a uniform policy intervention based on randomized control trials, or (b) delegate policymaking to local actors to harness knowledge from stakeholders and service users (Cairney Citation2017; Cairney and Oliver Citation2017). Such different forms of governance require different skills and competing visions of what counts as policy-relevant evidence.

Establish realistic expectations for researcher engagement practices

Policy analysts appear to expect more direct and short-term impact from their research than academic researchers. Academic researchers may desire more direct impact in theory, but also be wary of the costs and compromises in practice. We can clarify these differences by identifying the ways in which (a) common advice to analysts goes beyond (b) the common advice to academics (summarised by Oliver and Cairney):

Gather data efficiently, tailor your solutions to your audience, and tell a good story (Bardach and Patashnik Citation2020)

Address your client’s question, by their chosen deadline, in a clear and concise way that they can understand (and communicate to others) quickly (Weimer and Vining Citation2017)

Relate your research questions to your client’s resources and motivation (Mintrom Citation2012; Meltzer and Schwartz Citation2019).

“Advise strategically,” to help a policymaker choose an effective solution within their political context (Mayer, van Daalen, and Bots Citation2013, 43–50).

Focus on producing “policy-relevant knowledge” by adapting to the evidence-demands of policymakers and rejecting a naïve attachment to “facts speaking for themselves” (Dunn Citation2017).

In that context, it would be reasonable to set high expectations for research impact, but recognize the professional and practical limits to engagement. Our analysis suggests that most initiatives would benefit from more clarity from the designers of engagement initiatives about what implementers and users can realistically expect to achieve. For example, a funder might decide that a key aim is not to change a particular policy or practice, but rather to broaden discussion and debate around the framing of a policy issue. This goal could be served by strong leadership and convening, or facilitated collaborative discussion, rather than by providing a policy brief or an online tool for policymakers to use.

Yet, as far as we are aware, there is (a) no clear way of describing the goals of different engagement activities, or navigating the values that are implicit in engagement strategies, and (b) very little empirical evidence to inform decisions about what practices to support and why. For funders and others involved in the creation of engagement opportunities, this risks investment in poorly designed solutions to ill-specified problems. For researchers and other users of engagement strategies, it limits the ability to make informed choices about ethical, professional and strategic decisions. Despite growing investment in this area, there is little critical thought about the overall aim of improving researcher-policy engagement, beyond a desire to increase impact. Rather than aiming to increase the noise and volume of research in policy and practice, we urge organizations to support a more reflective consideration of the role of academic researchers in public life.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the activities of 346 organizations internationally provides lessons for funders and researchers aiming to invest in and improve research impact. Overall, we find that research-policy engagement is under-theorized and under-evidenced, with new activity outstripping research capacity to conceptualize and assess these efforts. In general, there is a relative over-investment in “push” activity, which is insufficient to improve how evidence is used in policymaking environments. Our mapping exercise suggests that most training and skills activities focus on helping researchers take their own work forward, rather than addressing policy agendas. Interest in relational practices is expanding, but most initiatives lack clear aims, measures of success, or meaningful engagement with the tradeoffs and politics of impact. Many organizations talk about collaboration, co-design or co-production, but there is little clarity on what these terms mean in practice and what the role of researchers should be. While many organizations aim to advocate, provide leadership, and fund new roles, they struggle to design and implement systems approaches. Only a handful of examples provide useful lessons on how to make sense of systemic support for engagement. The vast majority of organizations fail to draw on relevant research to plan or learn about engagement practices, leaving organizations and researchers ill-equipped to make critical choices. In the absence of evaluation studies in the public domain, we are in the dark as to how organizations design and deliver engagement initiatives, what they to aim achieve, and how successfully they support researchers to address the realities of policymaking.

We argue that a big part of the problem is a lack of clarity on what research engagement is for, and what “impact agenda” success would look like. Existing evaluation, where it is found, is limited by (a) a focus on the activities of individuals or the impacts of individual pieces of research (b) the use of a limited range of outcomes, such as the form and function of engagement projects and (c) inadequate theorization of policy impact aims and consequently relevant research/er practices. How can funders learn from evaluations of current initiatives if the criteria for evaluation are unclear? In that context, we connect seven key challenges to seven general recommendations for research funders seeking to invest in successful research-policy engagement strategies and researchers involved in shaping and delivering them:

Focus less on the abstract design of research engagement models based on what researchers would like to see, and more on tailoring researcher support to what policymakers actually do.

Strike a clear balance between support for individuals, institutions, and systems, as existing initiatives disproportionately target individuals with little clear evidence about how to target institutions or systems. When supporting individuals, foster a meaningful discussion of the tradeoffs between aims, such as to maximize the impact of already successful individuals or support marginalized groups. If seeking to “institutionalise” research engagement, clarify the extent to which one organization can influence overall institutional design. If describing a research-policy “ecosystem,” reject the idea that systems are conducive to disproportionate impact if researchers can pull the right levers. Rather, the same investment by researchers can have a large or negligible impact.

Clarify the overall aim of each form of engagement support, and evaluate practices in relation to that aim. Otherwise, research engagement is a poorly designed solution to a vaguely described problem, with poorly defined indicators of success or failure.

Equip researchers with knowledge of policy processes. Incorporate these insights into impact training alongside advice from practitioners on the “nuts-and-bolts” of engagement. In doing so, discuss how to address the tradeoffs between high-substantive but low-visibility impact and low-substantive but high-visibility impact.

Evaluate the effectiveness of initiatives in new ways, such as in relation to the skills (and support) required of an impactful critical researcher, or in relation to wider impacts such as on how policymakers and publics understand policy problems.

Evaluate initiatives according to clearly-stated expectations for researchers. For example, clarify if researchers should be responsible for forming or engaging with networks to foster co-produced research.

Describe the nature of the relationships between researchers and policymakers that should underpin expectations for engagement and impact. For example, are academic researchers akin to the policy analysts who see policymakers as their clients, or do they perform a more independent role?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bacchi, C. 2009. Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be? NSW: Pearson.

- Bardach, E., and E. Patashnik. 2020. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis. 6th ed. (International student edition). London: Sage.

- Bastow, S., P. Dunleavy, and J. Tinkler. 2014. The Impact of the Social Sciences: How Academics and Their Research Make a Difference. London: SAGE Publishing Ltd.

- Best, A., and B. Holmes. 2010. “Systems Thinking, Knowledge and Action: Towards Better Models and Methods.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 6 (2): 145–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/174426410X502284.

- Boaz, A., S. Hanney, T. Jones, and B. Soper. 2015. “Does the Engagement of Clinicians and Organisations in Research Improve Healthcare Performance: A Three-Stage Review.” BMJ Open 5 (12): e009415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009415.

- Boaz, A., and S. Nutley. 2019. “Using Evidence.” In What Works Now? Evidence-Informed Policy and Practice, edited by A. Boaz, H. Davies, A. Fraser, and S. Nutley. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Brans, M., I. Geva-May, and M. Howlett, eds. 2017. Routledge Handbook of Comparative Policy Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Cairney, P. 2015. “How Can Policy Theory Have an Impact on Policy Making?” Teaching Public Administration 33 (1): 22–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739414532284.

- Cairney, P. 2016. The Politics of Evidence-Based Policymaking. London: Palgrave Pivot.

- Cairney, P. 2017. “Evidence-Based Best Practice is More Political than It Looks: A Case Study of the “Scottish Approach.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 13 (3): 499–515. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/174426416X14609261565901.

- Cairney, P. 2018. “Three Habits of Successful Policy Entrepreneurs.” Policy & Politics 46 (2): 199–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230056771696.

- Cairney, P. 2019. “Evidence and Policymaking’” In What Works Now? Evidence-Informed Policy and Practice, edited by A. Boaz, H. Davies, A. Fraser, and S. Nutley. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Cairney, P. 2020. Understanding Public Policy. 2nd ed. London: Red Globe.

- Cairney, P. 2021. The Politics of Policy Analysis. London: Palgrave Pivot. Early draft https://paulcairney.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/paul-cairney-the-politics-of-policy-analysis-palgrave-pivot-full-draft-27.2.20.pdf

- Cairney, P., T. Heikkila, and M. Wood. 2019. Making Policy in a Complex World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cairney, P., and K. Oliver. 2017. “Evidence-Based Policymaking is Not Like Evidence-Based Medicine, so How Far Should You Go to Bridge the Divide Between Evidence and Policy?” Health Research Policy and Systems 15 (1): 35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0192-x.

- Cairney, P., and K. Oliver. 2020. “How Should Academics Engage in Policymaking to Achieve Impact?” Political Studies Review 18 (2): 228–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918807714.

- Caplan, N. 1979. “The Two Communities Theory and Knowledge Utilization.” American Behavioral Scientist 22 (3): 459–470. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000276427902200308.

- Chubb, J., and G. E. Derrick. 2020. “The Impact a-Gender: Gendered Orientations Towards Research Impact and Its Evaluation.” Palgrave Communications 6 (1): 72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0438-z.

- Derrick, G. 2018. The Evaluators’ Eye: Impact Assessment and Academic Peer Review. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Doucet, F. 2019. Centering the Margins: (Re)Defining Useful Research Evidence Through Critical Perspectives. New York: William T. Grant Foundation.

- Dunn, W. 2017. Public Policy Analysis. 6th ed. London: Routledge.

- Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). 2019. Delivery Plan 2019. Swindon: ESRC. https://www.ukri.org/files/about/dps/esrc-dp-2019/

- Gunn, A., and M. Mintrom. 2017. “Evaluating the Non-Academic Impact of Academic Research: Design Considerations.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 39 (1): 20–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1254429.

- Langer, L., J. Tripney, and D. Gough. 2016. The Science of Using Science: Researching the Use of Research Evidence in Decision-Making. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, University College London.

- Mayer, I., C. E. van Daalen, and P. Bots. 2013. “Perspectives on Policy Analysis: A Framework for Understanding and Design.” In Public Policy Analysis: New Developments, edited by W. Thissen and W. Walker, 41–64. London: Springer.

- Meltzer, R., and A. Schwartz. 2019. Policy Analysis as Problem Solving. London: Routledge.

- Michener, J. 2019. “Policy Feedback in a Racialized Polity.” Policy Studies Journal 47 (2): 423–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12328.

- Mijumbi-Deve, Rhona, Sarah E. Rosenbaum, Andrew D. Oxman, John N. Lavis, and Nelson K. Sewankambo. 2017. “Policymaker Experiences with Rapid Response Briefs to Address Health-System and Technology Questions in Uganda.” Health Research Policy and Systems 15 (1): 37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0200-1.

- Mintrom, M. 2012. Contemporary Policy Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mintrom, M. 2019. “So You Want to Be a Policy Entrepreneur?” Policy Design and Practice 2 (4): 307–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2019.1675989.

- Murji, K. 2017. Racism, Policy and Politics. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Oliver, K., and P. Cairney. 2019. “The Dos and Don’ts of Influencing Policy: A Systematic Review of Advice to Academics.” Palgrave Communications 5 (21): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0232-y.

- Oliver, K., A. Hopkins, A. Boaz, and S. Guillot-Wright. (forthcoming 2021). “Who Undertakes What Strategies to Promote Academic-Government Engagement?” Report for ESRC.

- Oliver, K., A. Hopkins, A. Boaz, S. Guillot-Wright, and P. Cairney. 2020. Research Engagement with Government: Insights from Research on Impact Initiatives, Policy Analysis, and Policymaking. (ESRC briefing).https://paulcairney.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/esrc-government-engagement-reports-final-version-24.6.20.pdf

- Oliver, K., S. Innvar, T. Lorenc, J. Woodman, and J. Thomas. 2014. “A Systematic Review of Barriers to and Facilitators of the Use of Evidence by Policymakers.” BMC Health Services Research 14 (1): 2. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2.

- Oliver, K., A. Kothari, and N. Mays. 2019. “The Dark Side of Coproduction: Do the Costs Outweigh the Benefits for Health Research?” Health Research Policy and Systems 17 (1): 33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3.

- Parkhurst, J. 2017. The Politics of Evidence. London: Routledge.

- Pedersen, D. B., J. F. Grønvad, and R. Hvidtfeldt. 2020. “Methods for Mapping the Impact of Social Sciences and Humanities – a Literature Review.” Research Evaluation 29 (1): 4–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz033.

- Phoenix, J., L. Atkinson, and H. Baker. 2019. “Creating and Communicating Social Research for Policymakers in Government.” Palgrave Communications 5 (1): 98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0310-1.

- Posner, S., and C. Cvitanovic. 2019. “Evaluating the Impacts of Boundary-Spanning Activities at the Interface of Environmental Science and Policy: A Review of Progress and Future Research Needs.” Environmental Science & Policy 92: 141–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.11.006.

- Powell, A. E., H. T. O. Davies, and S. M. Nutley. 2018. “Facing the Challenges of Research-Informed Knowledge Mobilization: ‘Practising What we Preach.” Public Administration 96 (1): 36–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12365.

- Radin, B. 2019. Policy Analysis in the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge.

- Ravenscroft, J., M. Liakata, A. Clare, and D. Duma. 2017. “Measuring Scientific Impact Beyond Academia: An Assessment of Existing Impact Metrics and Proposed improvements.” PloS One 12 (3): e0173152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173152.

- Schneider, A., and H. Ingram. 1997. Policy Design for Democracy. Kansas: University of Kansas Press.

- Smith, K., and E. Stewart. 2017. “We Need to Talk About Impact: Why Social Policy Academics Need to Engage with the UK’s Research Impact Agenda.” Journal of Social Policy 46 (1): 109–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279416000283.

- Smith, L. T. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books.

- Stone, D. 2012. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making. 3rd ed. London: Norton.

- Weimer, D., and A. Vining. 2017. Policy Analysis: Concepts and Practice. 6th ed. London: Routledge.

- What Works Network. 2018. The Rise of Experimental Government. London: Cabinet Office and ESRC.

- Williams, K., and J. Grant. 2018. “A Comparative Review of How the Policy and Procedures to Assess Research Impact Evolved in Australia and the UK.” Research Evaluation 27 (2): 93–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvx042.

- Williams, Oli, Sophie Sarre, Stan Constantina Papoulias, Sarah Knowles, Glenn Robert, Peter Beresford, Diana Rose, et al. 2020. “Lost in the Shadows: Reflections on the Dark Side of Co-Production.” Health Research Policy and Systems 18 (1): 43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00558-0.