Abstract

Indigenous polities often face the consequences of decisions that emerge from processes outside of their control. The U.S. Supreme Court decision on McGirt v. Oklahoma in 2020, which recognized nearly a third of the state of Oklahoma as potentially within the jurisdiction of five Native American tribes, is one such example. The lawsuit generating this decision was a legal appeal by an individual – not a tribe – and may have implications that include recognizing tribal jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters throughout much of the state. The decision was celebrated by tribes and those advocating for greater recognition of their territorial authority. Yet, for tribal leaders and other practitioners of Indigenous self-determination, the decision potentially shifts major administrative burdens to resource-limited tribes. In an attempt to mitigate the significant costs of administering this territory, these tribes have initiated negotiations with the state of Oklahoma and local municipalities to clarify jurisdiction and coordinate administrative responsibilities. Outrage over these negotiations came from mostly academics and activists who perceived negotiations as a rejection of greater jurisdictional sovereignty. This paper uses the McGirt decision as a point of entry to explore differences in how practitioners and academics grounded in Indigenous politics understand the impact of policy shifts even when they further mutually desired commitments.

1. Introduction

Scholars taking up the study of Indigenous autonomy typically hold similar values to the practitioners working within this field. Both see Indigenous self-determination and autonomy as key to improving outcomes for Indigenous peoples and a mechanism of further redress for past wrongs. In fact, the field of Indigenous or NativeFootnote1 studies was created, in part, to serve the interest of Indigenous peoples (see Deloria Citation1969; Biolsi and Zimmerman Citation2004; Richardson Citation2007). We are unaware, for instance, of any scholar in the field of Indigenous studies who has argued against the importance of self-determination for Indigenous peoples. A similar sentiment might also be made of tribal officials or administrators (we will refer to these groups as “practitioners” of Indigenous self-determination and autonomy) who vocalize their commitment to the sovereign or autonomous status of their polities in nearly every speech, interview, or presentation.

It was no surprise that scholars and practitioners celebrated the United States Supreme Court ruling in favor of Jimcy McGirt against the State of Oklahoma (McGirt v. Oklahoma Citation2020) (the case referred to hereafter as McGirt). The petitioner was not a sympathetic defendant given his crime – was found guilty of multiple sex offenses against minors – yet a decision in favor of McGirt involved the jurisdictional status of Native lands and ultimately expanded the potential reach and power of many Native Nations in Oklahoma.Footnote2 Undoubtedly scholars from the fields of law, sociology, criminology, and politics will examine the origins and effects of what is likely a seminal decision for indigenous polities in the United States. However, in this paper, we are interested in what happened between scholars and practitioners after the decision. Both scholars and practitioners perceived the increased recognition of territorial control as positive, yet the implications of McGirt meant very different things for these groups. For scholars, this was an expansion of tribal power upon which they should seize. Among practitioners, such as tribal officials, one implication was an unsolicited increase in the responsibilities over policy domains at the expense of other obligations such as social services. This split between scholars and tribal officials and what it means for understanding Indigenous politics is the subject of this work.

This paper is divided into four sections. The first explores previous research within the public policy as to the relationship between scholars and practitioners in Indigenous studies. The second provides a background to the McGirt decision and its potential implications for tribes in the region. The third foregrounds the response from many scholars to the tribe’s decision to negotiate with state officials over sharing jurisdiction and the claim that tribes were ceding recently expanded sovereignty. The fourth section considers characteristics of scholars and practitioners in Indigenous studies that have shaped the split over the implications of the McGirt decision. This section uses the McGirt decision to consider questions that might reflect back on the relationship between Indigenous governance practitioners and scholars and activists.

2. Scholar and practitioner relationships in public policy/administration and indigenous studies

Interest in the relationship between scholars and practitioners in public policy and administration goes back at least to the early 1990s (Schön Citation1991). Although there are many sources for the attention given to this relationship (see Tsui Citation2013), scholarship has taken a broad interest in whether these groups share similar values (see Gibson and Deadrick Citation2010 for one of many reviews). Aside from the degree to which scholars and practitioners share values, there is continued focus on the need for scholarship to contribute to societal value (Alford and Hughes Citation2008), evaluate the accuracy of how practitioners “think” (Schön Citation1991), and make the field relevant to the sectors it studies (Streib, Slotkin, and Rivera Citation2001). Other studies recognize that the credibility of public administration scholarship is associated with its relevance to practitioners. For instance, Henry (Citation1995) acknowledges how a tightly coupled relationship between research and practice was a central feature of the field of public administration’s most respected period (approximately the 1920s to the 1940s) whereas Englehart (Citation2001) has warned of the use of “science” to place theory above practice.

Public administration studies have identified how scholars and practitioners differ in what they may value. One key difference is the focus on what might be called “rigor” over “relevance” (see Buick et al. Citation2016, 36 or Sullivan Citation2011). Research by Armstrong and Alsop (Citation2010) and Radin (Citation2013), to name just a few of many studies, describe how scholars invest greater value in finding generalizable principles and sound methods than practitioners who are compelled more by the utility in solving specific problems. Whether solving specific problems through designing relevant research questions, as Wilkerson (Citation1999) argues, requires direct experience working within this field or close collaboration, and is one of the many perspectives on how to tighten the coupling of scholars and practitioners in public policy and administration.

A striking commonality between Indigenous studies and public administration is their shared mission to directly engage with practitioners to solve relevant problems. This is true not only of research in Indigenous governance but also the more broadly constructed field of Indigenous studies which includes research and projects in the humanities (see Castleden and Garvin Citation2008). As a field, Indigenous studies place considerable value on supporting practitioners and informing issues of policy (see Mauro and Hardison Citation2000 for a description around ecological policy). The origin of this commitment harkens to the foundation of the field which sought, in part, to be of service to Indigenous peoples and ensure the presence of Indigenous peoples and their knowledge in higher education. As Cook-Lynn (Citation1997) observes of the early convening of scholars who organized what would become Native American studies, “American Indians were not just the inheritors of trauma but were also heirs to vast legacies of knowledge about the continent and universe.” (9). These earlier calls for inclusion into higher education have expanded to include not only the presence of Indigenous peoples and their knowledge but also their methods and epistemologies (see the work associated with Smith Citation1999 or Kovach Citation2010). Some Indigenous scholarship has even turned traditional notions of university-based research “on its head” and argued that a scholarly convention is a form of ritual similar to what has been associated with “pre-modern” peoples (Wilson Citation2008).

In the field of Indigenous public administration and policy, the drive to create research valued by Indigenous peoples is shared widely. Such research takes a variety of approaches, but a few themes have emerged over the last decade. One theme is the interest in intergovernmental relationships. For instance, looking at records of local government meetings in the United States, Evans (Citation2011) identifies possible conditions in which Native tribes are more successful in creating policy favorable to tribes. Conner and Witt (Citation2016) found Native tribes that adopt partnerships with outside governments fared better in measures of organizational capacity. A recent and, therefore, perhaps less developed, theme in Indigenous public administration is how evidence might differ along with Indigenous and non-indigenous inquiry (see Ronquillo Citation2011). Drawing from previous work by Iaccarino (Citation2003) on Western notions of science and civilization as well as Cairney, Oliver, and Wellstead (Citation2016) on public administration’s use of American-dominant notions of evidence, Althaus (Citation2020) suggests that, if the field of public administration is to be of greater value for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples it must reexamine how it prioritizes certain forms of evidence. Better possible outcomes for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, for Althaus (Citation2020), include more nuanced ecological policies and effective justice systems (203–204).

Before discussing this article’s primary case study, we would like to identify a few topics in which scholars have been critical of Indigenous polities. None of these examples include scholars willing to undermine Indigenous self-determination as a project per se. Rather, they criticize how it is expressed and conceptualized. One prominent critique focuses on how many of the notions concerning political power have European, not Indigenous origins. Alfred (Citation1999) argues that the use of the term “sovereignty,” a mainstay in Indigenous political discourse, is a hallmark of colonial thought rather than an accurate manifestation of traditional Mohawk governance beliefs. Working within this similar tradition is Coulthard (Citation2014), who suggests that tribal practitioners who accept official recognition from settler states sanction European rather than Indigenous notions of legitimacy.

In terms of instances of disagreements between scholarship and practitioners, there are examples in both the United States and Australia. For instance, Wilkins and Wilkins (Citation2017) criticize Native tribes for violating the human rights of members who were purged from tribal rolls for political and economic gain. Scholars have been disparaging of practitioners’ decisions over the extraction of environmental resources across British settler societies (see Horowitz Citation2018 for general discussion). Such criticism also includes government policy and corporate interests and, therefore, is not exclusively focused on Indigenous polities, yet governance practitioners are often implicated in this research along with the negative outcomes (see Sincovich et al. Citation2018). Such criticism in Indigenous governance literature, has, to our knowledge, not included explicit discussions on these disagreements between scholars and practitioners in terms of their meaning, restraints, or avenues for systematic research in Indigenous studies. We offer the following discrepancy for an example. The McGirt decision was initially celebrated by scholars and practitioners for increasing tribal agency. Yet, scholarly criticism immediately followed when tribes, considering their responsibilities to their members, exercised their agency by negotiating with state and local authorities to deal with the aftermath of the McGirt decision.

3. The McGirt decision: background and implications

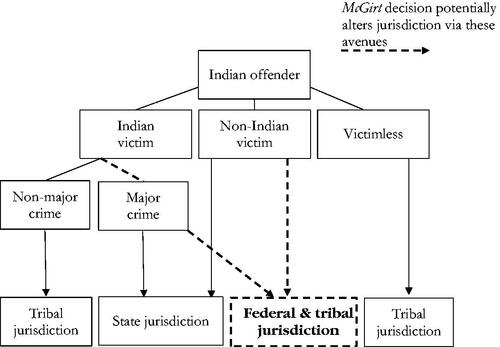

In the legal case, at stake was not whether Mr. McGirt had committed a crime, rather whether he had been tried in the correct jurisdiction given he was an enrolled member of The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, a Native American tribe that had been relocated to the region in the 19th century. Native defendants that committed major felonies on territory deemed as Native land, were required by the earlier court and legislative precedent to be tried in federal rather than state court. Complicating this unusual arrangement in the American legal system, was the federal government’s transfer of its authority to certain states to prosecute Native defendants for crimes that took place on Native lands. In the McGirt case, at issue was if criminal jurisdiction had been properly transferred to the state. By ruling in favor of Mr. McGirt, the Court recognized that both the land status of much of Oklahoma was akin to a form of title that confers rights to tribes and that the Creek Nation, whose land Mr. McGirt’s crimes took place on, possessed jurisdiction over it (see for geographic region and for accused and victim categorization and its link to jurisdiction). The State of Oklahoma did not have jurisdiction over Mr. McGirt given his status as a Native American and the location of the crime.

Figure 2. Approximation of effect McGirt decision on jurisdiction considering offender and victim ethnic status for alleged crime taking place on “reservation” land (adapted from A Roadmap for Making Native America Safer Citation2013).

The status of land has multiple implications for Natives and non-Natives regarding jurisdiction. To avoid a highly detailed history of the evolution of Native jurisdiction in the US, we will provide a brief synopsis. Native peoples were considered their own independent countries for the first few decades after the end of the American Revolution. By the 1830s, there had been greater claims by the federal and state governments over the criminal affairs of tribes (Ford Citation2008). However, the federal and state government’s jurisdiction was incomplete over Native lands when both the accused and victim were Natives until the late 19th century. It took Congress passing the Major Crimes Act (Citation1885) to finally place jurisdiction of capital crimes (murder, manslaughter, kidnapping, rape, assault, burglary, etc.) into federal jurisdiction. States had been left out of prosecuting Native peoples as states were found to have little to no jurisdiction over reservations as tribes had a direct relationship with the federal government that superseded states (see Fletcher (Citation2006) for the description of what is referred to as the “Marshall Trilogy”). It was only in the mid-20th century in which the federal government, through Acts of Congress, granted authority of criminal affairs to some states.

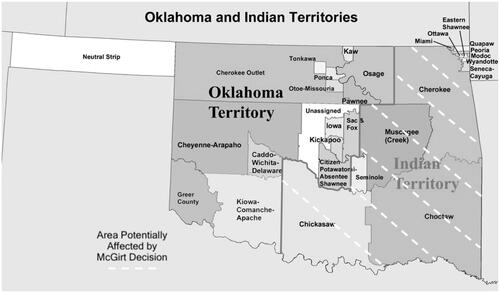

Native land status in Oklahoma is immensely complex even by American standards. Its heterogeneity is due to shifts in land policies and the varied ways that populations migrated to the state. We will provide a brief outline for the objectives of this article, but this is not a comprehensive account of how Native title and tribal lands developed within Oklahoma. What is now Oklahoma was occupied by multiple tribes including but not limited to Kiowa, Wichita, and Comanche. Under the Andrew Jackson Administration in the 1830s, the federal government made the Oklahoma region the location for tribes removed from the east coast and Great Lakes. A well-known example of the 1830s removal is the Cherokee’s Trail of Tears. Along with the Cherokee were four other tribes in this period: the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole. This group often referred to as the “Five Civilized Tribes” – now “The Five Tribes” – signed treaties with the federal government which included land on which they were to be settled in Oklahoma (or what was called “Indian Territory” in this period (see for map of Oklahoma by type of Indian land)). These tribes were settled on “trust land” which restricts its ownership and transfer to tribal members (see Foreman Citation1971 for a history of these tribes). Native “reservations,” in the US legal system are usually associated with trust land where tribal jurisdictional powers are greater because outside interests brought by non-Natives had not been established.

Over the latter 19th century, trust lands of the Five Civilized Tribes were eroded as more tribes were relocated to Oklahoma and the federal government appropriated existing lands to accommodate recent arrivals. The removal of native land ownership, trust status of reservation land, and the accompanying diminishment of tribal authority was not a one-off process but a series of legislative acts starting in the 1860s and ending in the 1900s (the undermining of tribal authority in Oklahoma continued into the 1950s). One major land reform act was in 1887 when Congress passed the General Allotment Act which altered the status of reservation land in Oklahoma to a system close to “freehold,” which meant that non-tribal owners could own land that had been designated for Natives (Hoig Citation1984).

Opening Native land during this period allowed for the Oklahoma Land Run, in which non-Natives, primarily from the east, were offered land in the Oklahoma Territory (Hightower Citation2018). Needless to say, this altered the political, social, and demographic composition of the territory. As Frymer (Citation2017) points out in his analysis of US westward expansion and ethnic politics in the 19th century, the federal policy typically altered the racial composition of territories to a more acceptable (from the perspective of the settler state) racial mixture before territories were incorporated into statehood. With its high percentage of Native peoples in the territory, it took a comparatively long period for Oklahoma to become a state which took place in 1907. This was relatively late for statehood when compared to adjacent states such as Kansas to the north (admitted 1861), Texas to the south and west (admitted 1845), and Arkansas to the east (admitted 1836), each of whom was admitted approximately 45–70 years prior to Oklahoma (see Frymer Citation2017 for analysis of statehood and racial composition).

Central to the McGirt decision was the status of reservation (or trust) land that had been moved freehold (or allotted land). Although it was clear that much of this land was no longer held in trust and therefore the jurisdictional status as a reservation had been extinguished for tribes. Although language around land status is generally inconsistent, the regions that were once trust land but had this status removed were and still are referred to as “tribal territory” but not “reservation land.” Tribal territory signifies less jurisdictional authority over such a region by tribes. It also indicates that greater authority by state governments. In the case of Oklahoma, most of the remaining land that was held in trust and designated as a “reservation” had been dissolved by the time of statehood. The McGirt decision opened the possibility that the original territory granted to the Five Civilized Tribes was still a reservation for criminal jurisdiction (see Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole land base on ).

Mr. McGirt’s attorneys successfully claimed that the jurisdictional authority of tribes and the status of land had not been properly “extinguished.” This follows previous Supreme Court decisions that held the federal government to a high standard for the extinguishment of Native jurisdiction, especially when treaties were signed recognizing tribal authority (see Washington v. United States Citation2018 as an example for resource rights). Treaties signed in the 1860s between the federal government and tribes that were relocated to Oklahoma are still binding despite the removal of trust land status in the McGirt decision. Selling land did not mean the removal of sovereignty in the case of major crimes. The effects of the McGirt decision on jurisdiction are therefore complex (see ). What the McGirt decision potentially affects is to rearrange jurisdictional avenues by directing certain Indian defendants to tribal or federal courts – depending upon the severity of the accusation – when the alleged crime took place on “reservation” lands.

The McGirt case was closely watched. By recognizing the land upon which the crime was committed as a form of Native title, such a designation would have implications for public policy and the terms upon which Native Nations and the state of Oklahoma interacted. Tribes, scholars, and activists with normative commitments to Native autonomy and self-determination applauded the decision. Affirming that nearly one-third of Oklahoma (see ) was a territory that had not been entirely ceded by Native tribes, the Court’s decision was considered a major victory shared by those supporting a greater form of autonomy for tribes.

Riyaz Kanji, the lawyer who argued on behalf of Mr. McGirt said “[we] will be quoting that decision for the rest of our lives” (Brave NoiseCat Citation2020). It clarified the status of land for members of the Five Civilized tribes, as Cherokee Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. stated, the “opinion today that the United States government should be held to its treaty obligations” and “Cherokee Nation is glad the [the Court] has finally resolved this case and rendered a decision which recognizes” (Polansky Citation2020) the reservations of the Five Civilized tribes. Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby’s press release read “We applaud the Supreme Court’s ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma (Citation2020) which holds that the Creek Nation’s treaty territory boundaries remain intact” (Polansky Citation2020). Along with enthusiasm for the decision there were cautions as to the potential reach of the decision for other tribes as Cherokee journalist and activists Rebecca Nagel states “strong language for tribal advocates to use, but at the same time, [the judge writing the Court’s opinion] was very, very clear about what this decision applied to and it just applies to Muscogee [another name for the Creek Nation where the crime had been committed]” (Johnston Citation2020).

4. Criticism of next steps

The shared sense of an important milestone in the McGirt case was almost immediately challenged by how tribes should proceed given this foundational shift. By ruling that part of Oklahoma was reservation land and subject to tribal or federal criminal jurisdiction, it meant that previously decided cases were incorrectly sent to state court rather than federal or tribal court. Approximately 850 currently imprisoned offenders were identified as Native and had been convicted of a crime that took place on reservation land which included a Native victim (Killman Citation2020). These cases may be reviewed and retried. Future cases with Native defendants and Native alleged victims could be potentially tried in federal or tribal court.

Shortly after the McGirt decision was released, it was revealed that the Creek Nation as well as the nearby Seminole Nation, had been in discussions with the State of Oklahoma over an agreement-in-principle (hereafter “the agreement”) that would clarify and potentially share criminal (and forms of civil) jurisdiction. This would mean that the tribe would not be entirely responsible for prosecuting and adjudicating crimes on their lands that had been deemed as “reservation.” The agreement recommended that Oklahoma’s Congressional representatives to the federal government enact certain changes in federal law to clarify jurisdiction and responsibility regarding tribal lands in Oklahoma (James and Lewis Citation2020). This would actively seek to draft Congressional legislation with the hope that it is not done so without the input of tribes. As Cherokee Chief Hoskin noted of Native history and the need to work with Congress to shape legislation “[i]f you’re not at the table – you know this from our history – you’re on the menu” (Crawford Citation2020). Initially, it appeared that leadership from the Five Tribes supported this agreement, but support was withdrawn after substantial criticism by scholars and activists (Murphy Citation2020).

The agreement drew the ire of scholars and activists who had praised the McGirt decision. Yet tribes have compelling reasons to relinquish (the Agreement in Principle does not relinquish, but it does invite co-jurisdiction) some of their jurisdictional control. The sovereignty recognized in the McGirt decision extended the power of tribes to prosecute their own citizens. Tribes have limited resources and directing these toward imprisoning their own citizens (and Natives of a different tribe) may not reflect the priorities of many tribes or address the needs of their citizens. It is worth noting here that the McGirt case was not brought by tribes and, in a certain sense, the expanded judication was decided for them, or perhaps most accurately, thrust upon them. By spending resources, both in terms of financial and staffing, toward prosecution and incarceration, tribes have less to fund healthcare, education, housing, and other services they deliver to their members.

Given that the prosecution and imprisonment of convicted offenders would usually be funded by the State of Oklahoma, the voluntarily adopting of these costs by tribes would prioritize a carceral notion of authority at the expense of others. And, of course, sovereign nations are free to select how they rank their priorities, which may include ceding jurisdictional responsibilities that work against their own interest or diminish their capacity in other domains. The resources directed toward incarceration would be significant. The average cost of housing a prisoner in the United States in 2019 was $36,000 (Bureau of Prisons Citation2019) and the per capita income for Native Americans in Oklahoma in 2018 was approximately $16,000 (Administration for Children & Families Citation2018). A critical perspective on the McGirt decision may follow other instances whereby further recognition of tribal authority shifts financial and social responsibilities from federal and state responsibilities to tribes (see Biolsi Citation2004 for an analysis of the furthering of tribal sovereignty as an abjuration of obligation to Native people).

It is entirely possible that tribes wished to intercede in possible legislation by engaging state government through the agreement. The McGirt decision undermined and complicated the Oklahoma’s jurisdictional authority. There is a concern by many tribal administrators that the expanded power of tribes in this part of Oklahoma would be misunderstood and overstated to the point where it could become a threat to other non-Native interests. Headlines surrounding the McGirt decision were overblown and included “U.S. Supreme Court deems half of Oklahoma a Native American reservation” (Hurley Citation2020 in Reuters) or “Supreme Court Rules That About Half of Oklahoma Is Native American Land” (Wamsley Citation2020 in the Washington Post). These make the decision sound as though Native peoples would control the political lives of non-Natives and their property, which is inaccurate. Cherokee Nation Chief Hoskin predicted that legislation would be passed to clarify land status and jurisdiction resulting from McGirt, “100 percent, you can guarantee they [Congress] will respond. Congress has a history to responding to Supreme Court cases which move the needle on tribal sovereignty” (Agoyo Citation2020). Such a concern has precedent dating to the 19th century in which Congress reduced tribal authority in response to court decisions that recognized tribal criminal and civil jurisdiction over regions.Footnote3

Substantial outrage greeted reports that some of the Five Tribes were engaged in negotiations with the state of Oklahoma after McGirt. The justifications for not fully pursuing jurisdiction over this area outlined in the previous paragraph were not made to, did not reach, or were uncompelling to many scholars and activists. U.S. Poet Laureate, scholar, activist, and Creek Nation citizen Joy Harjo wrote “What was an unprecedented victory is being undone—we are giving up our sovereignty. Heartbreaking” (Harjo Citation2020). In an essay titled Efforts to Undo Historic Victory in McGirt (Nagel Citation2020), lawyer, activist, and Cherokee Nation citizen Mary Katheryn Nagel said that the McGirt decision “should not subdue us into submission” and “[i]t is critical that we remain vigilant and poised, ready to pounce, on any and all attacks on McGirt as well as all future efforts to pass anti-sovereignty legislation[…].” Creek Nation citizen, policy advocate, curator, and writer Suzan Harjo claimed that an agreement with the state of Oklahoma “would nullify the Supreme Court’s decision in the McGirt case” and “Now is the time to stand for sovereignty, not give it away” and “it is the present generations’ duty to guard and protect it” (Agoyo Citation2020).

5. Considering disagreements between scholars and practitioners: three questions and observations

This article has limitations that should be acknowledged. It would be inaccurate to consider “scholars” and “practitioners” as monolithic groups easily divided into two categories. As often is the case, scholars and activists might be administrators and contribute to policy decisions (see Cobb Citation2005) or as collaborators for future development (see Harjo Citation2006). Organizing diverse perspectives to neatly fall within one of these two categories is also inexact. In fact, certain tribal legislators were critical of the agreement. Cherokee Nation council member Wes Nofire called the agreement “a sacrifice of our sovereignty” and planned to challenge it with a resolution (Agoyo Citation2020). It is unclear if legislators are entirely practitioners as they act outside of the executive functions of a tribe in most cases. We approach this limitation by contrasting instances in which there is little disagreement (in our case, that McGirt was a victory for tribal autonomy and recognition) against open criticism (e.g. certain tribes were in error from the opinion of multiple scholars in their potential policy responses to the McGirt decision). We also make no prediction to the effects of such jurisdictional change on crime, safety or equality. The part of this interaction to which we attend, is the relationship between scholars and practitioners, rather than the policy predictions or implications.

Limitations aside, this article demonstrates an avenue for further research on the interaction of scholars and practitioners working in Indigenous issues. Such research could add to a greater understanding of Indigenous issues and those who focus on them, but it is also necessary because of the policy effects scholarly criticism might have as seen in the McGirt decision. Partly motivated by the criticism of scholars and activists, tribal officials backed out of the earliest drafts of their agreement in principle with outside governments. It currently remains unclear what the next steps either tribes or Congress may take in response to the McGirt decision and what role scholars and activists might have in shaping how practitioners respond. This case and article bring up a point of entry to consider the ways those committed to Indigenous sovereignty may differ, as well as how we might ruminate on disagreement itself. Here we have outlined three questions that might guide such a conceptualization.

Are indigenous polities obliged to explain their decisions to scholars and activists?

Given the sovereign status of Native tribes in the United States, and those on which this article focused, explanation to scholars and activists would seem to be unnecessary. Yet, criticism in part generated from scholars and activists appears to have made tribal leaders alter their course. Perhaps administrative obligations and competing priorities that tribal leaders and practitioners face are not as apparent or of major concern to scholars. Scholars and activists might have an entrenched commitment to proving sovereignty that may obscure their appreciation for the limited resources of tribes and the need for services to be delivered to tribal citizens. There is precedent for such analysis. Ansell and Weber (Citation1999) identified that the field of organizational theory has had a greater ability to incorporate new concepts, such as networks, when compared to the field of international relations largely because it did not have a fixation on the concept of sovereignty. The concept of sovereignty could be a blinding torch rather than an illuminating candle. It could be, therefore, that the practicality that defines practitioners may imbue them with the liability of greater responsibilities. The McGirt decision and its aftermath give us a sense that established notions of differences between Indigenous governance practitioners and scholars still apply.

Are scholars of Indigenous communities and activists obliged to ask tribes before criticizing them?

It is striking that scholars and activists who criticized the potential agreement did not seem to ask for the administrator’s rationale before condemning them for relinquishing sovereignty. One might find this particularly unexpected for scholars who, when witnessing a seemingly counterintuitive action by tribes, could have used this instance as the basis for a deeper inquiry into their own perspectives and the political realities of Natives. In the past, it might be assumed that scholars see themselves as researchers who wished to know more about something before using normative critiques to judge it. Today one might hope that they would have a sequential relationship beginning with the knowledge to be followed by judgment. It is also curious, and noteworthy, that the great empathy for Native governance may be committed to abstractions such as sovereignty and jurisdiction more than administration which shapes the daily lives of tribal members. Or perhaps they do not see tribal administration as an extension of the sovereignty of a people. Rather, they may see the decisions of leaders and practitioners, in this case, as an extension of the process of dispossession. It might also seem here, that scholars would want to ask further questions, gather empirical evidence (via picking up a phone), and weigh it before making an intellectual or moral decision. Perhaps there is an inverse relationship between one’s willingness to express oneself through public media and one’s interest in seeking out the perspectives of others who do not explicitly express their views on such media.

How explicit should a conversation about the relationship between Indigenous polities and scholars be?

The McGirt decision and its aftermath might, at the risk of sounding flippant, be a point of entry into a larger conversation about conversations per se. It seems that if either practitioner explained their decisions or scholars and activists asked for their rationale, it could be the grounds for a generative discussion of these issues and perhaps a template for management and exploration of differing opinions about tribal priorities or what is sacred (i.e. sovereignty). Perhaps blinded by an insistence that Indigenous communities be an inspirational “counterculture” to the modern state (Sahlins Citation1999), Indigenous-focused scholars have shown disinterest in intratribal conflict and differing points of view about the priorities of a tribe and what can be waived to attain communal goals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 A note on nomenclature. In this article we will refer to Indigenous peoples in the United States as “Native Americans” (or “Native”). Given the widespread and accepted use of the terms “tribe” or “tribal” as they pertain to Native American polities, this paper will use these terms while acknowledging these are considered pejorative in other regions. When we refer to Native peoples outside of the United States or more globally, we will use the term “Indigenous peoples.”

2 Oklahoma is home to 39 tribes, 38 of which are federally recognized, which is a term indicating the federal government has a relationship with these groups that allow for federal funding but also place them in a polity-to-polity interaction. Federally recognized status is conferred by signing a treaty the federal government in the 18th or 19th century (treaty making ended in the 1870s), by Congressional Act (i.e. voting) or by an administrative process (often referred to as the acknowledgment process.

3 Regarding criminal jurisdiction, congress passed the Major Crimes Act (Citation1885) to undermine decision in Ex parte Crow Dog (Citation1883) which the federal court murder conviction of a Native man was overturned by the Supreme Court due to the victim of the crime being Native and the location an Indian reservation. In economic autonomy, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (Citation2018) as a restrictive response to the Supreme Court’s California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians (Citation1987) ruling that granted significant powers to tribes to avoid state-level regulation.

References

- Administration for Children & Families. 2018. “Tribal federal medical assistance percentage reference table for FYs 2017-2018.” https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/tribal-fmap-reference-fy2018

- Agoyo, A. 2020. “No ‘surrender’: Muscogee (Creek) Nation stands firm on sovereignty after historic Supreme Court win.” Indianz.com. https://www.indianz.com/News/2020/07/20/no-surrender-muscogee-creek-nation-stand.asp

- Alford, J., and O. Hughes. 2008. “Public Value Pragmatism as the Next Phase of Public Management.” The American Review of Public Administration 38 (2): 130–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008314203.

- Alfred, T. 1999. Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Althaus, C. 2020. “Different Paradigms of Evidence and Knowledge: Recognising, Honouring, and Celebrating Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 79 (2): 187–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12400.

- Ansell, C., and S. Weber. 1999. “Organizing International Politics: Sovereignty and Open Systems.” International Political Science Review 20 (1): 73–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512199201004.

- Armstrong, F., and A. Alsop. 2010. “Debate: Co‐Production Can Contribute to Research Impact in the Social Sciences.” Public Money & Management 30 (4): 208–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2010.492178.

- Biolsi, T. 2004. “Political and Legal Status (“Lower 48” States).” In A Companion to the Anthropology of American Indians, edited by T. Biolsi. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Biolsi, T., and L. J. Zimmerman, eds. 2004. Indians & Anthropologists: Vine Deloria Jr. And the Critique of Anthropology. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

- Brave NoiseCat, J. 2020. “The McGirt case is a historic win for tribes: for federal Indian law, this might be the Gorsuch Court.” The Atlantic, July 12. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/07/mcgirt-case-historic-win-tribes/614071/

- Buick, F., D. Blackman, J. O’Flynn, M. O’Donnell, and D. West. 2016. “Effective Practitioner–Scholar Relationships: Lessons from a Coproduction Partnership.” Public Administration Review 76 (1): 35–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12481.

- Bureau of Prisons. 2019. “Annual determination of average cost of incarceration fee.” Department of Justice. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/19/2019-24942/annual-determination-of-average-cost-of-incarceration-fee-coif

- Cairney, P., K. Oliver, and A. Wellstead. 2016. “To Bridge the Divide between Evidence and Policy: Reduce Ambiguity as Much as Uncertainty.” Public Administration Review 76 (3): 399–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12555.

- California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians. 1987. 480 U.S. 202.

- Castleden, H., and T. Garvin. 2008. “Modifying Photovoice for Community-Based Participatory Indigenous Research.” Social Science & Medicine 66 (6): 1393–1405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.030.

- Cobb, A. 2005. “The National Museum of the American Indian as Cultural Sovereignty.” American Quarterly 57 (2): 485–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2005.0021.

- Coulthard, G. 2014. Red Skin, White Masks. Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Cook-Lynn, E. 1997. “Who Stole Native American Studies?” Wicazo Sa Review 12 (1): 9–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1409161.

- Conner, T., and S. Witt. 2016. “The Role of Capacity and Problem Severity in Adopting Voluntary Intergovernmental Partnerships: The Case of Tribes, States, and Local Governments.” State and Local Government Review 48 (2): 87–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X16653450.

- Crawford, G. 2020. Tribal Controversy: CN Chief, Councilor Butt Heads during Committee Meeting. Tahlequah, OK: Tahlequah Daily Press.

- Deloria, V. Jr. 1969. Custer Died for Your Sins. New York, NY: McMillen.

- Englehart, J. K. 2001. “The Marriage between Theory and Practice.” Public Administration Review 61 (3): 371–374. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00037.

- Evans, L. 2011. “Expertise and Scale of Conflict: Governments as Advocates in American Indian Politics.” American Political Science Review 105 (4): 663–682. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055411000347.

- Ex parte Crow Dog. 1883. 109 U.S. 556.

- Fletcher, M. 2006. “The Iron Cold of the Marshall Trilogy.” North Dakota Law Review 82: 628.

- Ford, L. 2008. “Indigenous Policy and Its Historical Occlusions: The North American and Global Context of Australian Settlement.” Australian Indigenous Law Review 12: 69–80.

- Foreman, G. 1971. The Five Civilized Tribes. Norman, OK: The University of Oklahoma Press.

- Frymer, P. 2017. Building an American Empire: The Era of Territorial and Political Expansion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gibson, P. A., and D. Deadrick. 2010. “Public Administration Research and Practice: Are Academician and Practitioner Interests Different?” Public Administration Quarterly 34 (2): 145–168.

- Harjo, J. 2020. “U.S. poet laureate Joy Harjo condemns tribes move for agreement-in-principle with State of Oklahoma.” Tribal Town Radio. https://tribaltownradio.wordpress.com/2020/07/17/u-s-poet-laureate-joy-harjo-condemns-chief-hills-move-for-agreement-in-principle-with-state-of-oklahoma/

- Harjo, L. 2006. “GIS Support for Empowering the Marginalized Community: The Cherokee Nation Case Study.” In GIS for Sustainable Development, edited by M. Campagna, 433–449. New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Hurley, L. 2020. “U.S. Supreme Court deems half of Oklahoma a Native American reservation.” Reuters, July 9. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-court-oklahoma-idUSKBN24A268

- Henry, N. 1995. Public Administration and Public Affairs. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hightower, M. 2018. 1889: The Boomer Movement, the Land Run, and Early Oklahoma City. Norman, OK: The University of Oklahoma Press.

- Hoig, S. 1984. The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889. Oklahoma City, OK: Oklahoma Historical Society.

- Horowitz, L. S., A. Keeling, F. Lévesque, T. Rodon, S. Schott, and S. Thériault. 2018. “Indigenous Peoples’ Relationships to Large-Scale Mining in Post/Colonial Contexts: Toward Multidisciplinary Comparative Perspectives.” The Extractive Industries and Society 5 (3): 404–414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.05.004.

- Iaccarino, M. 2003. “Science and Culture.” EMBO Reports 4 (3): 220–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.embor781.

- Indian Law and Order Commission. 2013. A Roadmap for Making Native America Safer: Report to the President and Congress of the United States. Washington, DC: Indian Law and Order Commission.

- James, D., and C. Lewis. 2020. “Oklahoma tribes, AG reach agreement in principle: Initial agreement creates cooperative ‘path forward’ in civil, criminal jurisdictions.” CHHI News Service. https://www.theadanews.com/news/local_news/oklahoma-tribes-ag-reach-agreement-in-principle/article_559db9de-59ee-52c6-af8d-c884a542d126.html

- Johnston, Z. 2020. “A chat with Rebecca Nagle about what last week’s historic Supreme Court decision means for Indian Country.” UPROXX, July 13. https://uproxx.com/life/rebecca-nagle-interview-mcgirt-decision-creek-nation/

- Killman, C. 2020. “Supreme Court ruling affects more than 800 ‘Indian Country’ criminal cases in Oklahoma so far.” Tulsa World, October 29. https://tulsaworld.com/news/local/crime-and-courts/supreme-court-ruling-affects-more-than-800-indian-country-criminal-cases-in-oklahoma-so-far/article_ee591c26-fc32-11ea-b0d7-1fe32cb9baca.html

- Kovach, M. 2010. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- McGirt v. Oklahoma. 2020. 591 U.S. ___

- Major Crimes Act. 1885. .—18 U.S.C. § 1153.

- Mauro, F., and P. D. Hardison. 2000. “Traditional Knowledge of Indigenous and Local Communities: International Debate and Policy Initiatives.” Ecological Applications 10 (5): 1263–1269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1263:TKOIAL.2.0.CO;2]

- Murphy, S. 2020. “Oklahoma tribal leaders say they don’t support agreement.” Associated Press, July 19. https://www.swtimes.com/news/20200719/oklahoma-tribal-leaders-say-they-dont-support-agreement

- Nagel, M. K. 2020. “Efforts to undo historic victory in McGirt.” NIWRC. https://www.niwrc.org/rm-article/efforts-undo-historic-victory-mcgirt

- Polansky, C. 2020. “Tribes, State, Officials react to historic SCOTUS ruling on McGirt V. Oklahoma.” Public Radio Tulsa, July 10. https://www.publicradiotulsa.org/post/tribes-state-officials-react-historic-scotus-ruling-mcgirt-v-oklahoma#stream/0

- Radin, B. 2013. Beyond Machiavelli: Policy analysis reaches midlife. 2013 Georgetown, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Richardson, T. A. 2007. “Vine Deloria Jr. as a Philosopher of Education: An Essay of Remembrance.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 38 (3): 221–230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2007.38.3.221.

- Ronquillo, J. C. 2011. “American Indian Tribal Governance and Management: Public Administration Promise or Pretense?” Public Administration Review 71 (2): 285–292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02340.x.

- Sahlins, M. 1999. “Enlightenment? Some Lessons of the Twentieth Century.” Annual Review of Anthropology 28 (1): i–xxiii. 1999. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.28.1.0.

- Schön, D. A. 1991. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Surrey, UK: Ashgate.

- Sincovich, A., T. Gregory, A. Wilson, and S. Brinkman. 2018. “The Social Impacts of Mining on Local Communities in Australia.” Rural Society 27 (1): 18–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10371656.2018.1443725.

- Smith, L. T. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London, UK: Zed Books.

- Streib, G., B. J. Slotkin, and M. Rivera. 2001. “Public Administration Research from a Practitioner Perspective.” Public Administration Review 61 (5): 515–525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00124.

- Sullivan, H. 2011. “Truth Junkies: Using Evaluation in UK Public Policy.” Policy & Politics 39 (4): 499–512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/030557311X574216.

- The Indian Gaming Regulatory. 2018. Act U.S.C. $ 2701.

- Tsui, A. S. 2013. “The Spirit of Science and Socially Responsible Scholarship.” Management and Organization Review 9 (3): 375–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/more.12035.

- Wamsley, L. 2020. “Supreme Court rules that about half of Oklahoma is Native American land.” National Public Radio, July 9. https://www.npr.org/2020/07/09/889562040/supreme-court-rules-that-about-half-of-oklahoma-is-indian-land

- Washington v. United States. 2018. 584 U.S. ___

- Wilkerson, J. M. 1999. “On Research Relevance, Professors’ “Real World” Experience, and Management Development: Are we Closing the Gap?” Journal of Management Development 18 (7): 598–613. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02621719910284459.

- Wilkins, D., and S. H. Wilkins. 2017. Dismembered: Native Disenrollment and the Battle for Human Rights. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Wilson, S. 2008. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Black Point, Canada: Fernwood Publishing