Abstract

The idea that the future is too serious and strategic to be discussed with people who are not “experts” is so commonly shared that citizens’ voices are lacking in most decision-making processes and future-oriented choices whether we look at political or research and innovation agendas. Yet, proofs to contradict this vision are now multiplying and can be found in a growing number of case studies and scientific publications. Citizens are proving not only to be legitimate actors to contribute to the future agenda-setting of local, national or European levels but also relevant and pertinent contributors. However, this practice of participatory agenda-setting—even though it is getting greater attention—remains relatively experimental, atypical and sporadic. The limits and drawbacks of citizen participation processes have already been highlighted in the literature but rather than calling this practice to an end it actually calls for more experimentation as the difficulties do not diminish the democratic need, legitimacy and value of such governance practices. Especially, since many western democracies are becoming very fragile. We will see in the preliminary part of this paper, the many challenges that undermine not only the functioning of democratic processes but also the citizens’ role and sense of agency in the governance of the society they live in, as well as the role of elected officials and experts regarding agenda-setting, then we will look into the lack of future thinking not only in the political sphere but also the educational and social practices, analyze the values of participatory processes and its potential limits and risks and finally review an experimental case of participatory foresight and policy design from the small town of Marcoussis (France) which successfully conducted a participatory agenda-setting experiment—and voted—after a 2 years-long process, their local agenda for the future together with its inhabitants, civil servants and elected officials. Marcoussis has engaged around 600 people (out of a population of 8000 inhabitants) in 25 moments, using very diverse methods and techniques (forum-theater, philosophy talks, market of ideas for the future, collective distillation) and setting the process in unusual and non-administrative contexts (entering into schools, ‘hacking’ their local popular festivals) to touch a very diverse set of citizens and gather as many contributions as possible. In this case analysis, we will inspect the preliminary conditions of how Marcoussis set up their participatory foresight and agenda-setting process, then review the creative tools and design methods that were experimented and finally, draw the lessons learned in terms of participatory agenda-setting processes and democratic innovations.

1. “Those responsible for our future”

Even though, recent decades have witnessed a shift in the fields of planning and future studies toward more open and participatory processes” , foresight and future agenda setting is still often seen as something too complex and important to be left to laypeople. Future thinking should rather remain the task of politics and experts only.

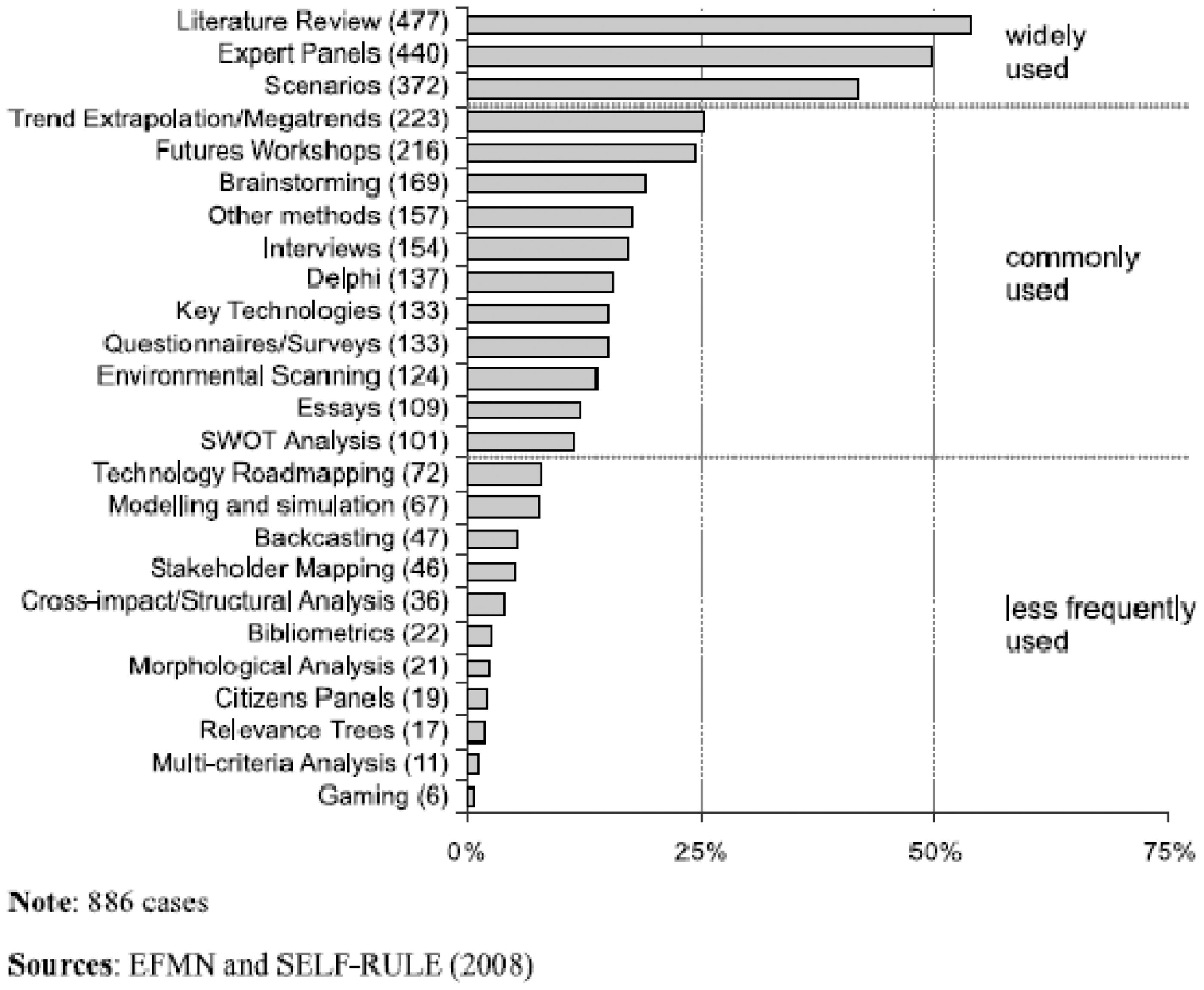

The Classifications of foresight methods conducted by The European Foresight Monitoring Network and The SELF-RULE in 2008 showed that most foresight methods still focused on Literature Review and Expert Panels (50%) whereas Citizens Panels, for example, was a method used in about 2% of cases. Turturean (Citation2011) adds that “pooling voting, brainstorming, Forecast Genius, Sci Fi, Roadmapping, etc. were methods which could be found only exceptionally in foresight.” We will see that the methods used in the study case of this article refer to those rather experimental and uncommon foresight methods.

The idea that the future is too serious and complex to be discussed with people who are not “experts” is still so commonly shared that citizens’ voices are, even now, lacking in a lot of decision making processes and future oriented choices whether we look at political or research and innovation agendas. Since citizens are not considered as “legitimate” or even “capable” of thinking about the future and deciding about it, nor given a chance to do so, many citizens consider it is not their role nor responsibility to participate in strategic and decisive future thinking and agenda-setting activities. “We have contributed, given our ideas but it’s now in the hands of those who are responsible for our future”Footnote1—meaning politicians and experts—commented a Bulgarian citizen who participated in a European research project called CIMULACT which gave voice to citizens on setting the future European research agenda. This expression, “those responsible for our future,” reveals a lot about how citizens perceive their limited role and power of contribution in shaping the future of society.

This assumption in which elected representatives are solely responsible for society’s future and decisions is very much entrenched into the conception and practice of most modern democracies. The essence of democracy, the “governance by the people” is organized, in practice, through a structure of representative government. People elect representatives that are given a mandate to rule, decide and make choices for them—in their name and interest—(whether we are in parliamentary or presidential democracy). This mechanism relieves citizens from most governance responsibilities. And for nearly a century, citizens have grown accustomed of being very rarely involved or consulted in governance’s questions or decisions, beyond voting once every couple of years. Unfortunately, these mechanics seem to be growingly dysfunctioning as “many across the world are dissatisfied with how democracy is working” (Pew Report 2019). Democracies are now “suffering from a withdrawal of public confidence and participation” (DeBardeleben and Pammett Citation2009) and it is now the very model of representative democracy that is being questioned (Michels Citation2010).

When the future is not drawn by politicians, it is drawn by experts. Either scientists who have particular knowledge and expertise in a field (biology, economy, etc.) or “future experts” meaning foresight experts and strategy consultants. Both types tend to influence the future by giving some directions to research and innovation and/or political agenda. The first is seen as a legitimate actor to draw the future because of the deep knowledge they have on specific issues and topics. The second has developed a series of methods that allow them to “explore or anticipate” the future by combining different factors and hypotheses of evolution based on advanced analysis of trends and statistics, in order to develop contrasted scenarios of plausible futures. Foresight practice has demonstrated (and assumed) both its value and limits (Godet Citation2000), especially because of the combinatorial explosion of almost infinite factors to be calculated and more broadly, the growing unpredictability of the real world of the 21st century (societal, technological, accelerated climatic changes). Yet, it is not because the future is uncertain that we should not look at it, on the contrary (Aaron Citation2000).

Whether politicians or experts contribute to influencing and defining future directions and agendas, citizens tend to be absent from the equation. But why is it so? Why thinking about the future isn’t a strategic conversation in which citizens are invited to take part? Why inventing the future isn’t an ordinary social and democratic practice?

In this paper, we will first look into the difficulties yet the importance of future thinking, then we will analyze the values of participatory processes and their potential limits and risks and finally review a case of participatory foresight and policy design, which I, personally, took part in, from the small town of Marcoussis (France). In this case analysis, we will inspect the preliminary conditions for setting up a participatory foresight and agenda-setting process, then review the creative tools and design methods that were experimented and finally, draw the lessons learned in terms of participatory foresight and agenda-setting processes.

2. The future in a myopic world

“Tomorrow will not be like yesterday. It will be new and depend on us. It is less to be discovered than to be invented.” (Gaston Berger, 1964).

Not only politicians’ representativity is regularly questioned but, more essentially, politicians’ capacity to offer “rallying” long-term vision (over 20, 30, 40 years) appears to become scarce. Politicians—when they do—think about the future, do it with a shorter and shorter time horizon. Four, five, six years at best, which usually simply corresponds to the length of their term of office. This widely recognized “disorder of democratic governance” is often referred to as short-termism, policy short-sightedness or political myopia (Boston Citation2016). This “presentist bias” as Boston calls it, is critical as it prioritizes short-term objectives and quick policy implementation “over long-term ones to the detriment of overall societal outcomes.” On top of that, elected representatives’ trust level has never been so low in mature Western democracies (Tormey Citation2015). Political competences are now rather measured on politicians’ ability to maneuver in a complex environment of actors, power struggles, influences games than their capacity to offer and carry long-term political visions (Issa Citation2015).

In a certain way, this is not entirely the politicians’ fault. Indeed, who is trained to imagine, develop and carry long-term visions? It is extremely rare to be taught about future thinking at school, whether in primary school, secondary or even university. The practice of foresight, the methods and tools of vision building, are largely absent in most educational curriculums. Even though “over recent decades many people have seen and experienced first hand just how inspiring, innovative and profoundly useful futures approaches in education can be. Yet over time such innovations remain remarkably rare” (Gidley, Bateman, and Smith Citation2004). However, it is now more acknowledged that future thinking is not only a useful and key skill but a necessary competence for “future-ready” children and citizens. The OECD is not only promoting future thinking in school (through its Schooling for Tomorrow Knowledge Base program) but adds that “futures thinking offers ways of addressing, even helping to shape, the future; it is not about gazing into a crystal ball. It illuminates the ways that policy, strategies and actions can promote desirable futures and help prevent those we consider undesirable. It stimulates strategic dialogue, widens our understanding of the possible, strengthens leadership, and informs decision-making. UNESCO Futures Literacy program (started in 2012), proposes to increase citizen’s capacity to envision and reflect on the future: “Futures Literacy is an essential competence for the 21st century. Being futures literate empowers the imagination, enhances our ability to prepare, recover and invent as changes occur.”

Farsightedness is critical in policymaking (Ascher Citation2009) but also in research and innovation agenda setting. And “the ‘reactive’ approaches to policymaking have not only increasingly proven ineffective but also far most costly (in both human and financial terms) than anticipating and preparing for the crisis before it occurs” comments Tõnurist and Hanson (Citation2020) in their OECD working paper on Anticipatory Innovation Governance, which calls for more proactive and future-oriented governments.

Not only there is a lack of future thinking in policymaking, but there is also a lack of participatory approaches and more democratic processes. Thinking about the future and setting agendas means making strategic, political choices, which illustrates a particular conception of society as we want it, with values, fundamental principles, etc. Today, not only society is suffering from generalized myopia (looking only at what stands right before our eyes, right now) but also lacks the voices and views of those “experiencing” the results of decisions that are made: citizens.

3. “Nothing about me or for me without me:” thinking about the future for greater democracy

If politicians and experts, as well as media (McCombs and Shaw Citation1972), hold fundamental roles in agenda-setting—even though with a short-term focus –, it seems that we are missing a key stakeholder in the equation: citizens. What could their role be in agenda-setting, and more specifically future-oriented agenda-setting?

Building upon the motto “nothing about me or for me without me,” the policy design practice (or user-centred policy design) brings a lot of attention—and care—in bringing citizens into policymaking processes. Citizen participation contributes to a better democracy (Michels Citation2011). Laurens De Graaf (De Graaf Citation2007) explains that by “involving stakeholders and (groups of) citizens at an early stage of the policy process rather than consulting them immediately before the implementation phase, we can create a broader support for policy decisions and, therefore, make government policy more effective and legitimate.” On top of that “engaging citizens in policy making allows governments to tap into wider sources of information, perspectives and potential solutions, and improves the quality of the decisions reached” (Michels and De Graaf Citation2010). Even in research agenda setting processes, citizen-based approaches deliver “multi-perspective and inter- and transdisciplinary approaches to stated challenges (portraying clear societal needs), while expert-based reports more often suggested traditional research formats in singular fields” (Rosa, Gudowsky, and Warnke Citation2018).

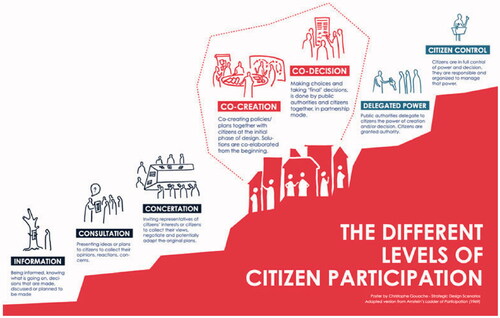

Not only greater citizen participation can allow better governance and policies but “people worldwide are crying out to have more say in the public decisions that most impact their lives locally and nationally” says Dr. Carolyn J. LukensmeyerFootnote2. “Around the world, citizens are de- manding new forms of democracy, in which their engagement extends beyond the ballot box and tokenistic consultation” adds Professor John GaventaFootnote3. It appears clearly that participatory democracy and citizen engagement in policy-making go beyond the “simple” consultation in which “government asks for and receives citizens’ feedback on policy-making.” We are moving toward active participation and co-production of policy-making. As the OECD (Citation2001) frames it, active participation “means that citizens themselves take a role in the exchange on policy-making, for instance by proposing policy options. At the same time, the responsibility for policy formulation and the final decision rests with the government. Engaging citizens in policy-making is an advanced two-way relation between government and citizens based on the principle of partnership.” The ambition is to progressively experiment and reach higher levels of Arnstein’s participation ladder (Citation1969), meaning, going from information or even consultation levels to partnership levels or even delegated powers (or collaboration and empowerment if we refer to the IAP2 Spectrum of Participation) .

4. As participatory processes are becoming more and more “trendy,” the risk of “fake participation” is growing accordingly

Citizen participation, participatory democracy, deliberative democracy, citizen consultation, etc.—whatever these concepts may be called—are becoming very “trendy” concepts at the moment—especially politically–. Inspiring democratic innovations are multiplying everywhere but as citizen participation becomes more and more a “must-have” (and that no one can—politically and publicly—claim that there should not be any citizen participation), we are also observing the rise of “fake participation” (Gouache Citation2020) or “participation-washing.” Redesigning a whole neighborhood, ordering studies, making plans, taking strategic decisions, ordering construction works, all that without any exchange with citizens… and coming at the end of the planning to ask them what color they would like the benches to be painted in, is a good example of deceitful participatory process. Yet many so-called participatory processes are simulacrums of participation. The reasons behind conducting such processes, however, can be multiple. They can be intentionally designed that way so as to respond to hidden agendas like trying to limit a risk of conflict with citizens (trying to avoid a petition, a demonstration, etc.) or to polish a political image, or to respond to political tactics and strategies, etc. And sometimes, they are just “badly designed” (wrong tools, chaotic process, insufficient planning, etc.). In that last case, the result is mostly due to a lack of competence and resources from the public authority rather than a tokenistic intention.

This type of “fake” participation process in which citizens are asked to express their opinions on non-decisive or unimportant matters can be very harmful to democracy. It is even worse than doing nothing. Why? First, because “citizen participation has proved itself equally useful and successful in complex technical matters as well as in controversial social and ethical questions” (Hierlemann Citation2019). Second, because democracies are already “suffering from a withdrawal of public confidence and participation” (DeBardeleben and Pammett, Citation2009). The current trust level of governments is quite low (in modern western democracies) and “many across the world are dissatisfied with how democracy is working” (Pew Report Citation2019). Therefore, the people who accept to take part in citizen participatory processes are, potentially, the few most active and dedicated citizens you may begin with. Yet we disrespect them by having them decide upon futile matters and none of the crucial/strategic aspects that will impact their daily ways of living. This type of fake participation process can be extremely harmful as you immediately “lose” the citizens who showed up and came out angry, frustrated, disappointed, —once more, by politics and administrations–. This simply reinforces the growing conviction that governments do not really care, do not really listen to citizens but only fake to do so. This is damaging democracy. Aware of this risk, the case presented in this paper, proposes an honest and genuine—yet humble and perfectible—participatory process in which the local government really wanted to get people’s views, ideas, and desires regarding where to go in the future.

5. Marcoussis (Fr), a village that experimented with participatory foresight and policy design

“When facing the many challenges our town and our world has to deal with right now but also in the future, we know we need to innovate but we also know we can not respond to these challenges alone. We need the collaboration of public authorities, of local stakeholders and citizens all togethers,” stated the town of Marcoussis. “We don’t want to just fix problems, we want to draw a desirable future that we want to go toward.”

Building upon this logic of involving citizens to draw the future and elaborate a policy agenda, the town of Marcoussis (south of Paris, France) initiated an inspiring process in 2016.

The town of Marcoussis (France) experimented with this approach under the leadership of the Mayor, Olivier Thomas who seized the opportunity of the redefinition of their Agenda 21 (local sustainable development program), to initiate a participatory process of co-creation of “Marcoussis tomorrow,” Marcoussis in 2038. This village of 8000 inhabitants invited over 500 citizens in a two year long process of co-definition of the future of Marcoussis. In order to conduct this participatory foresight and policy design process, the town of Marcoussis used multiple approaches, including a design-based toolkit created to conduct local participatory foresight processes: Visions +21 (co-created by the French Ministry of Environment and a design and innovation lab called Strategic Design Scenarios (Belgium)).

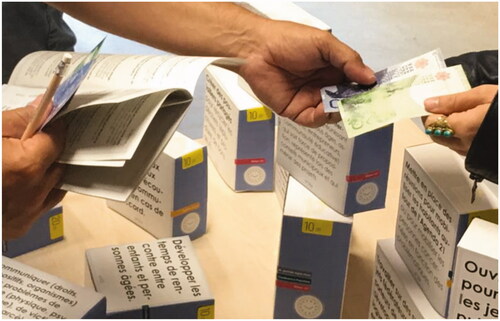

The multiple approaches were the following: first, a work led by the elected officials together with 150 citizens on the question of well-being (and what it meant in living in Marcoussis). At the end of this stage (using the SPIRAL Footnote4approach), 1110 criteria of well-being were identified and discussed. Then, the town used the Visions + 21 toolboxes to run four participatory activities. The first one looked at the perceptions of elected officials and town civil servants regarding Agenda 21 and sustainability in general. Then, the following activity aimed at discussing the challenges that were the most relevant ones for the town together with a mixed group of 1/3 of citizens, 1/3 of civil servants and 1/3 of elected officials. This mixed group then identified strategic directions to be taken in order for the town to be resilient (when facing its challenges), then finally co-created 4 desirable scenarios for the future. In parallel to this process and in order to enlarge the conversation, the town conducted 3 extra activities. One called the “voice opener” and designed for local NGOs to get familiar with Agenda 21, one called the “popular conference” and designed as a convivial philosophical moment to question happiness in the future in Marcoussis, and one called the forum-theater (or Theater of the OppressedFootnote5) and meant for the youth of Marcoussis to express themselves regarding the future. The global process generated 107 ideas for the future of Marcoussis. These were then submitted to the inhabitants on the occasion of a big and open “Market for the future”.

6. Going beyond the usual suspects…

At this stage, one could say that Marcoussis had done an impressive work of exploring the future in rather uncommon ways . Indeed, they combined multiple techniques and indirect approaches like questioning well-being and what it means for people in terms of social needs, instead of falling into the trap of asking right away the question to the citizens: what would you like the future to be like in Marcoussis? in which citizens tend to come up with a Christmas-list type of answers. Even though the town had involved a wide range of actors, citizens, youth, NGOs, etc., they felt that they did not go enough beyond the usual suspects (Lee and Abbot, Citation2003), or in other words: “it’s always the same” [people who participate]. Indeed, because of the topic as well as the format (mostly workshop-style activity), the town “attracted”—by default—a certain type of citizens: first, retired people (as they often have time to offer), then the ones that are active locally (socially engaged), plus the ones who are climate activists or at least sustainability-sensitive and finally the ones who have a certain level of education and/or skills to be comfortable discussing and reflecting “philosophical” questions (the future, well-being, etc.). Conscious of this issue, the town, together with the innovation lab Strategic Design Scenarios (SDS) (co-author of the original Visions + 21 toolboxes) decided to elaborate an ad-hoc approach which would both overcome the usual suspect's limitations as well as allow the collective distillation (Visions + 21 toolboxes) of the 107 ideas. This process was called the “Market for the future”

If you wish to get “random citizens” or at least more unusual suspects you should not invite citizens to come over to the town hall but rather go to people wherever they might be. Following this logic, the town and SDS decided to “hack” a public event where “lay” people would be. The choice was made to hack the local popular Wheat Festival (Fête du blé). Over a weekend, this festival gathers people around old tractors, farming tools and of course beers, wine, food, music and games. This local popular event brings a very heterogeneous crowd of people from middle-age inhabitants, elderly ones, young ones, families, etc. And, more importantly, people who are not aficionados of participatory approaches and who most likely never heard about the local Agenda 21.

7. A market for the future with fictional local money to invest for the future of Marcoussis

There was no chance to “catch” people if the town had set a stand amongst the many stands of the festival. Therefore, they decided to set up a table right at the entrance of the Festival. Why? So that the visitors would believe this table is the “official entrance table” to the festival (even though it’s a free entrance festival). Upon their arrival, inhabitants were handed over a set of banknotes. Not only this is an unusual thing (to arrive somewhere and to be given cash right off) but the banknotes were, strangely, not euros. But an unknown currency called “Marcoussous” (the suffix “sous” meaning money in old french). A fictional local currency of Marcoussis. Each participant (they first had to confirm they were inhabitants of Marcoussis) would receive 200 Marcoussous and be invited to enter a room were the market was set up (there is a building on the festival location). People were then asked to buy the ideas of the future (from the 107 ideas) which, according to them, were the most crucial, the most important for the future of Marcoussis. Similarly to participatory budgeting, the point here is to have the citizens decide upon what matters and what are the needs that need to be fulfilled, according to them .

The strategy in the process is that the budget is limited. Similar to the town budget where the Mayor and the counselors have to take decisions and investment priorities, citizens cannot invest in everything, they have to make [political] choices and reflect on them. Amongst the 107 ideas, not all of them “cost” the same price. Some are more “expensive” to implement than others. The fact that citizens had “real” and realistically designed paper bills in their hands made the “game” very real and serious. Families, couples and friends were discussing and arguing about their investments. “It’s difficult, there are so many good ideas worth investing in… but we don’t have an unlimited budget,” “Can I borrow some money from you, this one is too expensive, I don’t have enough left but it’s a really good one” are some of the comments which could be heard during the session. “People took the ‘game-like’ experience very seriously almost as if they were investing their own money” commented one elected official acting as one of the market stalls’ merchant. As people would invest in the ideas they felt as more relevant and meaningful for the village, the team would record, live, the results for everyone to see.

During the day, over a hundred people of all ages were able to contribute in a “fun” way to the definition of priorities for the future of Marcoussis. The market session was then followed by a session of collective distillation with a group of stakeholders from the territory composed of NGOs, elected officials, civil servants and local businesses. They were all invited to also invest in the ideas and add their choices to those of the citizens (the vote of the “distillers” were not prevailing over the choices of the citizens but complementing it on an equal basis 1 = 1). Finally, the group analyzed the market results in order to see what was coming out of it. It is important to mention here that the stakeholder's group (including the Mayor and other elected officials), even though they did not transform citizens’ outputs, held the responsibility to ensure and guarantee that whatever would come out of the process would be in line with ethics, law and the general interest. Taking this in consideration, they, however, did not have to change or censor any of the output as no content needed to be filtered. One hypothesis could be that since the whole process was a collective and multi-stakeholder one, potential unethical ideas did not survive the process (because of collective control and responsibility). The other—maybe complementary—hypothesis is that the initial framework of the process (building a vision of a sustainable, desirable future) has, by default, prevented unethical and undesirable inputs to emerge or remain throughout the process.

The multiple key elements of this vision of the future then appeared: Marcoussis 2038 would be a village whose living environment is preserved (forests, fields, river, etc.), a village in which diversity, solidarity (especially intergenerational) and conviviality are at the heart. It is also a connected village (connected to other territories by high mobility) and a territory that exploits its assets, particularly agricultural ones to develop a responsible and sustainable economy (organic local food, solar farm, etc.). It is finally a territory of democracy and active citizenship. This vision of Marcoussis is not revolutionary or extravagant, it is the vision of citizens caring for their village, who value their quality of life in green and preserved environment, who love the atmosphere of their village where everyone knows one another, help one another. It is also a village that is opened and connected to its neighbor territories and resolutely innovative in terms of the local economy and sustainable energy.

8. Building upon a design practice: using the power of visualization

The participatory process that was designed in Marcoussis did not end with the Market for the future. It ended with the creation of the vision of Marcoussis 2038. But again, a future vision is only of interest if it is apprehensible and shareable. Therefore it shall not all be resumed into a 15 text pages PDF. Summarizing such content and process into a written text reduces most of the value and effort that have been put into it.

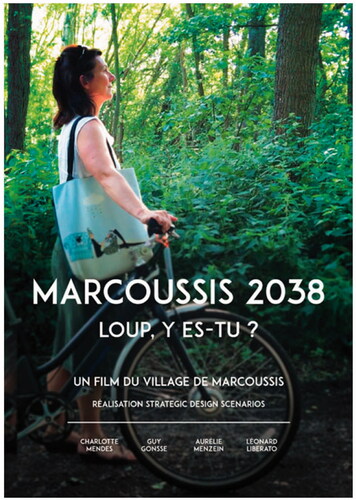

Building upon the design practice of visualizing solutions, concepts and scenarios, Strategic Design Scenarios proposed to visualize this vision of Marcoussis in 2038. Future visualizations may support democratic social conversations (Jégou and Gouache Citation2015) and therefore help enlarge the discussion about the future. To allow citizens of Marcoussis to imagine their village in the future (based on the ideas they chose), the team decided to make a participatory short film: Marcoussis 2038, Loup y-es tu? (Figure 6) Footnote6 (Marcoussis 2038, Wolf are you there?)Footnote7. Participatory film? Because all the actors of the film are not professional actors but citizens of the village and were shot in the streets of Marcoussis in one weekend.

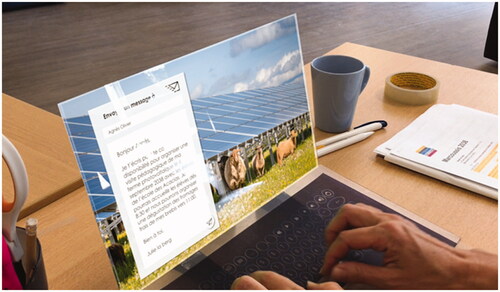

This short film shows a moment of everyday life in Marcoussis in 2038. It does not picture the whole vision of Marcoussis in the future but just bits of it that were selected by citizens. It is a quick glimpse into the casual everyday-life future of Marcoussis. In opposition with sanitized and ultra-technological SciFi films, the short film displays an ordinary day, a “future mundane” (Foster Citation2013) in 2038 in Marcoussis where the past, present and future are combined altogether. As Foster would call it, the film offers a vision of an “accretive space” where past, present and future cohabit all together. A futuristic computer, responsive advertising under bock or an interactive poster display offer some evidences that we are indeed in the future. But space, chairs, decoration remind us that time has piled up and that the future does not wipe off everything from the past. On the contrary, the film offers a vision where the future is a sort of “inevitable evolution” but does not mean that social relations, conviviality, simplicity, etc. are completely gone. Finally, anecdotical proofs of the future may also be found dispersed throughout the film, a paper poster on the fridge which shows the 2032 Festival of Female Rockers, a discreet blackboard on the counter informing about a walking tour by the river on the June 16 2038 and so on. As for the “real” ideas from the vision they are seamlessly presented throughout the whole film: a shared coworking space, soft mobility, a carpooling station, a public child center, organic food, local complementary currency, etc. They “lie in the background” of the main narrative/story.

Even though Strategic Design Scenarios remained the “warrant” of the esthetic quality of the process, the film was made in a participatory way. Indeed, people participated in “the production process by contributing to the script [the Mayor himself and his team], acting [citizens], location scouting [civil servants and citizens] and all other activity [editing, stage logistics, gathering of accessories with civil servants and citizens] of the film production” (Goris, Witteveen, and Lie Citation2015). Once the film was edited, the last challenge was to spread it for citizens to see .

9. Going beyond classic institutional communication

Most often, when public institutions produce communication materials, they tend to deliver very neutrally—or dull—materials. In terms of channels, public authorities often rely on the town magazine or journal, paper mails, a post on the town’s website and eventually some posters in public buildings (or on street display). Of course, if the short film is to be published only on the local government website—or even the town’s Facebook page when there is one—dissemination will be rather limited considering that most citizens do not consult on a regular basis the town’s website or social network page.

Following a logic of “friendly hacking” (Jégou, Vincent, and Thevenet Citation2013), the team decided, once more, to “hack” a local event to showcase the short-film: the Strawberry Festival (Fête de la Fraise). At the Festival, not only did the town have an interactive stand to present the results of the process but the Mayor himself made a public invitation—right in the middle of the festival—to invite every participant to follow him to the local public cinema for the public showing of the short-film. The film was presented to citizens and later on, during the French Public Innovation Week (every year in November), the short-film was screened again at the cinema before every films in place of the commercials for one week .

10. Lessons learned and reflections from the case of Marcoussis

The example of Marcoussis constitutes an emblematic case of integral participatory foresight and policy design process. The town of Marcoussis achieved the key following—non-exhaustive—results: making the future reachable and discussable, going beyond the usual suspects by meeting citizens where they are (and not the opposite), gamifying participatory approaches to make them enjoyable, designing a process which allows quick and light citizen participation (20–30 min contribution instead of 3 h long evening workshop), being honest and genuine with the participatory process all along and finally respecting people’s voice. Indeed, all along the process, great care has been brought to remain as open, inclusive and true as possible, meaning that the voice of the citizens has been respected and really valued all the way—in contrast to many participatory or consultation processes where citizens are asked to generate ideas, proposals, etc. but in the end, the elected officials pick and decide whatever they wish, regardless of the citizens’ inputs or choices—.

In order for the future to be discussable, the framework has made the future concrete, meaning translated the future into real-world challenges that citizens can relate to and understand. In order for the future to be reachable, the process has set a double-time horizon, first, a vision in 20 years, then a policy agenda for the next 5 years. This allows to both avoid pure “blue-sky thinking” and ensure that people realize they can contribute to change the future (UNDP Citation2015). Regarding the usual and unusual suspects, the process had the double value of including both in the process. At some stage, volunteer and interested citizens would contribute and at others, completely random and lay citizens would contribute. This gives a chance to both “type” of citizens’ voices to be heard (and not only the ones who naturally speak up). This last aspect is key in terms of the democratic process as the conversation should not be confiscated by a small group of willing citizens alone (Community Links and Council on Social Action UK Citation2008). The town government felt “stuck”—and frustrated—with this issue and was unable to overcome it for years until the experience of Marcoussis 2038 opened up new ways of collaborating with citizens. Of course, other successful methods are often used to ensure diversity of views in participatory processes such as sortition—random selection of citizens—(Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2018) but in the case of Marcoussis, sortition was a bit out of reach due to capacity and budget limitations. Whatever the method, the critical point is that you cannot satisfy yourself by only putting an “open to all” sign on the door, you have to proactively recruit citizens.

If you wish to attract diverse and random citizens to your process, you have to offer them a pleasurable or “fun” experience. This point may, at first, appear “superfluous” or at best “nice to have” but the case of Marcoussis has proven to be undeniably crucial. Policy matters are, for a majority of people, not something they rely on or feel naturally attracted to. The perception—by citizens—of policy-making processes is often rather negative. The little experience citizens have of policy-making is often limited to what is showcased by media: long and conflictual debates, never-ending arguments, or even “schoolyard squabbles” as French people say (meaning that politicians are like kids squabbling). Therefore, most citizens (beyond the few willing citizens) are not attracted by policy-making processes—nor they do value them –. Taking this in consideration, we need to offer them a policy-making experience that profoundly differs from what they perceive or might have experienced (“boring” or “useless” neighborhood councils/meetings for example). This is why the town of Marcoussis made a lot of effort in inventing and designing a fun and pleasurable experience. Building upon the gaming mechanisms, the idea was to offer citizens a gamified experience (described more in detail earlier in this article). Even though gamification is still new and emerging in participatory processes (Thiel, Ertiö, and Baldauf Citation2017) multiple experiments show a trend toward great usability of gamified participatory processes (Gade Johansen and Bech Pedersen Citation2019). “Gamification can be a useful tool to promote civic engagement and improve the relationship between citizens and the State” (Coronado Escobar and Vasquez Urriago Citation2014). The study of the case of Marcoussis confirms, from an empirical point of view, the current scientific observations.

The genuine process of Marcoussis was made possible only because the local situation gathered a certain number of key ingredients: first, strong political support and dedication by the Mayor himself (putting his hands on), second, a strong internal mutual trust between the elected officials and the civil servants (allowing, therefore, the civil servants to take initiatives and experiment or “try out”), third, a quite solid history of social & community engagement and volunteering, fourth, the support of experienced designers with participatory foresight and policy innovation processes and fifth, the true intention to elaborate and implement both a strategy and an action plan at the end of the process (which town council voted in 2018). Finally, it is also important to take into account the length of the process: roughly 2 years in total. The town of Marcoussis acknowledged from the beginning that in order to be integral and “fine,” their process would—necessarily—take some time. They, therefore, dedicated specific resources—even though quite limited (which required even more ingenuity to be able “to do a lot with a little”)—time and effort to be able to carry on their process. These specific ingredients do not undervalue the inspiring character of the case of Marcoussis but may constitute clear limitations for replicability in other context and cities.

The story of Marcoussis is a stimulating—even though perfectible—case of local participatory democratic process or even “democratic innovation” (Smith Citation2009) as Marcoussis went beyond the “familiar institutionalized forms of citizen participation” (referendums, citizen councils, etc.). This case also confirms the readiness and willingness of citizens to be more active and involved in local policymaking or agenda-setting processes as long as we offer them a pleasurable experience as well as a “promise of concrete” output (in this case the Agenda 21 strategy and action plan). The case of Marcoussis reinforces the conviction that greater participatory forms of democracy are possible and meaningful yet to be continued and experimented with. Hopefully, the experience will profoundly transform the “ways of doing” policymaking in Marcoussis but will also inspire others to explore and invent creative and genuine forms of participatory foresight and participatory agenda setting.

Notes

1 Quote from a Bulgarian citizen participating to the CIMULACT, H2020 EU research project on Citizen and multi-actor consultation on Horizon 2020. He explains that he happily contributed to the participatory process but that the decisions were not his but in the hands “of those responsible for our future” meaning policymakers & experts.

2 Dr. Lukensmeyer is Executive Director of the National Institute for Civil Discourse from the University of Ari-zona. Citation from Nabatchi and Leighninger (Citation2015). Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy.

3 Pr. Gaventa is Director of Research at the Institute of Development Studies, UK. Citation from Nabatchi and Leighninger (Citation2015). Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy.

4 SPIRAL stands for Societal Progress Indicators for the Responsibility of All. SPIRAL is an approach of collective learning aiming at gradually building, from the local level to the global one, the ability of society to ensure the well-being of all through co-responsibility between its different stakeholders: citizens, public and private actors. https://wikispiral.org/

5 The Theatre of the Oppressed (TO) describes theatrical forms that the Brazilian theatre practitioner Augusto Boal first elaborated in the 1970s, initially in Brazil and later in Europe. Boal's techniques use theatre as means of promoting social and political change. Originally developed out of Boal’s work with peasant and worker populations, it is now used all over the world for social and political activism, conflict resolution, community building, therapy, and government legislation. In the Theatre of the Oppressed, the audience becomes active, such that as "spect-actors" they explore, show, analyse and transform the reality in which they are living.

6 The short-film is accessible here: https://vimeo.com/277469930

7 It is believed by some experts and historians that the french writer Charles Perrault would have written its version of the Little Red Riding Hood based on a real event that happened in Marcoussis in 1962 where a young female shepherd got partly devored by a wolf.

References

- Aaron, H. 2000. “Seeing through the Fog: Policymaking with Uncertain Forecasts.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 19 (2): 193–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6688(200021)19:2<193::AID-PAM2>3.0.CO;2-Q.

- Arnstein, S. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 35 (4): 216–224.

- Ascher, W. 2009. Bringing in the Future: Strategies for Farsightedness and Sustainability in Developing Countries. University of Chicago Press;

- Berger, G. 1964. Phénoménologie du temps et prospective. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Bertelsmann, Stiftung. 2018. Citizens’ Participation Using Sortition—A Practical Guide To Using Random Selection To Guarantee Diverse Democratic Participation, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh.

- Boston, J. 2016. How to Overcome Political Myopia. Statecrafting. http://www.tjryanfoundation.org.au/cms/page.asp?ID=2427

- Community Links, Council on Social Action UK. 2008. Willing citizens and the making of the good society: the ideas underpinning the practical work of the Council on Social Action, CoSA paper no. 1, Community Links. Published by Community Links ©2008 ISBN 978-0-9561012-1-1

- Coronado Escobar, J. E., and A. R. Vasquez Urriago. 2014. Gamification: an effective mechanism to promote civic engagement and generate trust? In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, pages 514–515. ACM.

- DeBardeleben, J., and Jon Pammett. 2009. Activating the citizen: Dilemmas of participation in Europe and Canada. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Foster, N. 2013. The future mundane, Core 77’s Design Directory.

- Gade Johansen, A., and C. Bech Pedersen. 2019. Gamified Participation, Challenging the Current Participation Methods in Urban Development with Minecraft. Urban Design Institute of Architecture & Design, Aalborg University, Danemark.

- Gidley, J., & D. Bateman, and C. Smith. 2004. Futures in Education: Principles, practices and potential, monograph No 5, the strategic foresight monograph series.

- Godet, M. 2000. La prospective en quête de rigueur [Foresight in Search of Rigor], Futuribles n° 249.

- Goris, M., L. Witteveen, and R. Lie. 2015. “Participatory Film-making for Social Change: Dilemmas in Balancing Participatory and Artistic Qualities.” Journal of Arts & Communities 7 (1): 63–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/jaac.7.1-2.63_1.

- Gouache, C. 2020. Why Do We Need Participatory Democracy If We Already Have Democracy? Baseline Study of the Active Citizens network, URBACT.

- Graaf, L. de. 2007. Gedragen beleid. Een bestuurskundig onderzoek naar interactief beleid en draagvlak in de stad Utrecht. Delft: Eburon.

- Hierlemann, D. 2019. Participatory Democracy: From the Talk of the Town to a Fundamental Cultural Change. From local to European: Putting citizens at the centre of the EU agenda, European Committee of Regions, p. 86, https://doi.org/10.2863/597145

- Issa, P. 2015. Where Have the Long-term Visions Gone? Medium, https://medium.com/social-entrepreneurs/where-have-the-long-term-visions-gone-22b91c7122ca

- Jégou, F., S. Vincent, and R. Thevenet. 2013. Friendly Hacking into Public Sector: Co-creating Public Polices within Regional Governments. Co-Create Conference. Helsinki: Aalto University.

- Jégou, F., and C. Gouache. 2015. “Envisioning as an Enabling Tool for Social Empowerment and Sustainable Democracy.” In Responsible Living: Concepts, Education and Future Perspectives, edited by V. W. Thoresen, R. J. Didham, J. Klein, D. Doyle, 253–271. Cham: Springer.

- Lee, M., and C. Abbot. 2003. The Usual Suspects? Public Participation under the Aarhus ConventionThe Modern Law Review, 66(1), 80-108. Retrieved May 28, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1097549

- McCombs, M., and D. Shaw. 1972. “The Agenda-setting Function of Mass Media.” Public Opinion Quarterly 36 (2): 176–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/267990.

- Michels, A., and L. de Graaf. 2010. “Examining Citizen Participation: Local Participatory Policy Making and Democracy.” Local Government Studies 36 (4): 477–491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2010.494101.

- Michels, A. 2011. “Innovations in Democratic Governance: How Does Citizen Participation Contribute to a Better Democracy?” International Review of Administrative Sciences 77 (2): 275–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852311399851.

- Nabatchi, T., and M. Leighninger. 2015. Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy.

- OECD. 2001. Citizens as Partners: OECD Handbook on Information, Consultation and Public Participation in Policy-Making, Éditions OCDE. Paris.

- OECD, 2017. Futures thinking in brief, Schooling for tomorrow: Knowledge bank. Paris. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/schoolingfortomorrow-thestarterpackfuturesthinkinginaction.htm

- Pew Research Center. 2019. April “Many Across the Globe Are Dissatisfied With How Democracy Is Working.” p.5

- Rosa, A., N. Gudowsky, and P. Warnke. 2018. “But Do They Deliver? Participatory Agenda Setting on the Test Bed.” European Journal of Futures Research 6 (1): 14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40309-018-0143-y.

- Smith, G. 2009. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation (Theories of institutional Design). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thiel, S. K., T. P. Ertiö, and M. Baldauf. 2017. Why so serious? The role of gamification on motivation and engagement in e-participation. Interaction Design and Architecture(s). p.167

- Tõnurist, P., et, and A. Hanson. 2020. Anticipatory Innovation Governance: Shaping the Future through Proactive Policy Making Documents de travail de l'OCDE sur la gouvernance publique, n° 44. Paris : Éditions OCDE.

- Tormey, S. 2015. The End of Representative Politics. Cambridge. Polity Press.

- Turturean, C. 2011. “Classifications of Foresight Methods.” The Yearbook of the “Gh. Zane” Institute of Economic Researches 20: 113–123.

- UNDP Global Centre for Public Service Excellence. 2015. Foresight, The Manual. Singapore