Abstract

Through a case of civic action in relation to rural development in Denmark, this paper contributes its deliberations on rural participatory policy by shedding light on the unordered site of controversy where participatory-oriented policy meets public involvement practices that happen beyond procedural limits. Danish rural planning is marked by economic and population decline and by economic pressure on the municipal sector. In this uncertain situation, rural livelihood and development increasingly rely on citizens. Drawing on perspectives from participatory design, public involvement, and Science and Technology Studies, and mobilizing the concept of design Thing, the paper attempts to understand a citizen-initiated participatory design (PD) process as an experimental means of public involvement in a rural setting. It analyses the intersection between the micro-level activities of the PD process and national and municipal plans, policies and procedures. In doing so, it traces how the socio-material PD process was a civic attempt to contest institutional definitions and to move the power to define issues from the authorities to the community. It analyses the role of the PD process in the articulation of shared issues, and how this process was one event in the ongoing community practices of public-ization of issues and of forming publics, so as to define local trajectories for an uncertain future. Continuing the analysis, the paper considers that the process of issue and public formation is neither linear nor uncontested; there is no single public, but rather multiple and porous configurations of difference and change.

Introduction: Forming publics at a site of controversy

The wide-read text by Arnstein (Citation1969) on the ladder of participation offers insight into the site where policy and civic action meet. According to Arnstein, this is a site of difference and power struggle, of multiple, often contesting needs, desires and consequences—some of which may often be unidentified and unarticulated. It is a site of continuous attempts and tactics by the “power holders” on the one side, and the “have-nots” on the other side, to navigate this site of antagonism in order to produce favorable conditions.

In this paper, we focus on the formation of issues and publics through participatory design (PD) at the site of controversy where participatory-oriented policy meets civic community action. The paper traces an instance of civic action, following how the people of a local community act in response to perceived threats to their livelihood and future, and initiate local processes of contestation and constructive criticism to institutional plans, policies, and procedures. These processes may be understood as an experimental means of public involvement outside of procedural settings. Accordingly, in the article, we analyze how one of these—a socio-material PD process—takes shape as an instance of the “public-ization of issues” (Marres Citation2007).

The focus of our analysis is the uncertain future of rural territories that struggle with bleak projections of population and economic decline. This is a complex situation with multiple issues involving a mesh of relationships and without a clear trajectory of resolution. Unlike Arnstein’s account of a battlefield of opponents (which we by no means propose to ignore as a brute reality across the world), we seek to move beyond a “we vs. they”-dichotomy, while still acknowledging the adversarial relationship between policy and civic community. Our aim is to untangle some of the complex web of relationships between people, artifacts, and activities (Linde Citation2014) that exist within and beyond institutions and without clear settlement. The large-scale and long-term advancement of democracy, genuine participatory policy, and sound rural planning to tackle this uncertainty, sparks the consideration of participatory policy in an agonistic site, where dissensus and the legitimacy of adversaries is acknowledged (Mouffe Citation2004), and in which issue formation does and must happen in unordered public sites beyond the limits of procedures (Marres Citation2007).

Publics and design things

In the context of public policy, publics may take different forms: professional associations, producer groups, consumer groups, public interest groups, neighborhood groups, and more (May Citation1991). A public can be defined as a specifiable group of people, emerging and gathering by means of a common interest in or active confrontation of an issue. In the PD literature, publics have been discussed in light of John Dewey’s pragmatist and pluralistic stance (DiSalvo Citation2009; le Dantec and DiSalvo Citation2013). The Deweyan public is characterized by an acknowledgement of the situatedness, multiplicity and dynamics of the configurations of people that form a public. Publics are situated because they are inseparable from the conditions of their origins; they are brought into being and qualified through and in response to issues in context. Publics are multiple in that there is no single public; rather, a multitude of publics can form in relation to a single issue, around different understandings of shared conditions and responses to them. And publics are uneven and dynamic configurations because issue formation and the plurality of voices, opinions and positions continuously change.

In urban planning and urban design, participation is often regarded as a means to involve various stakeholders in realizing a spatial project. Concrete artifacts and the geographical site of the project take center stage in this product-oriented process. However, highlighting the formation of issues and publics shifts the attention. We move beyond the problem-solving logic of PD to consider participation in the ongoing process of democratic future-making, including issue formation.

The PD process that we analyze below was a socio-material process, activating, building, and re-configuring networks among people, artifacts and activities. In this process, design artifacts became a medium for gathering people to explore a vision of physical development in the village. We can conceptualize the PD process as a rurally situated “design Thing” (Latour Citation2005b; Bjögvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren Citation2012; DiSalvo Citation2009, Citation2016)—a socio-material assemblage that constructs a space for social interaction by relating people and concrete artifacts and doings in articulating issues that were previously disparate.

The idea of the Nordic Thing facilitates an understanding of a design Thing: a political and social assembly in a certain time and place at which different interests and perspectives are articulated and negotiated (Bjögvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren Citation2012).

When foregrounding the formation of publics and the concept of a design Thing, the main purpose of PD is not to create a solution or to resolve tension between issues or stakeholders, nor is it to initiate direct change. The task of design here is to draw people together in a collaborative process of issue identification and possible action: what is at issue here? What to do about it? Accordingly, DiSalvo et al. (Citation2014) describe design Things as “relational expressions that draw together humans and non-humans, resources and passions, in order to make issues manifest” (2398). Hence, the promise of design Things, according to the literature, is to make it accessible to participants to identify what is at issue by putting conditions and possible futures under discussion.

Marres (Citation2007) emphasizes an issue-oriented perspective on public involvement, developed from Dewey, Lippman and later Science and Technology Studies (STS) accounts. Issue formation, Marres finds, should be appreciated as a crucial dimension of democratic politics. It concerns the opening up of an issue to critical scrutiny outside the institutional setting that has often defined the issue. While involvement procedures such as public consultations and citizen conferences are intended to consider the concerns of average people, they tend to hinder the articulation of these public concerns because the framings that delimit the topics of discussion do not allow for the formulation of these concerns. In order to understand the difference that publics can make to politics, the publics’ attempts at articulating issues should be attended to. This public-ization of issues may be seen in events and practices that contest official issue definition and seek to move issue formation from the institutional setting to the community.

Centering our focus on the formation of issues and publics through a socio-material PD process allows us to learn about controversies and perceived gaps between policy and community, as well as about tactics to build capacity and power among the community groups actively involved in becoming influential participants in defining trajectories for an uncertain future.

Method

The paper analyses an empirical study conducted in rural Denmark. The empirical work consists of a micro-level, community-based urban design scenario experiment in the village of Hundelev and of observations and interviews with villagers and local authorities before, during and after the PD process, as well as informal talks and email exchanges with villagers and urban planners. The paper analyses the empirical material of the micro-level activities through institutioning these in meso-political contexts (Huybrechts, Benesch, and Geib Citation2017).

In general, the approach to the empirical study has been to follow “practices-in-the-making” (Marres Citation2007; Latour Citation2005a) by immersing ourselves at the site of civic action in rural Denmark, in an effort to understand how a community group attempts to raise issues and gather the wider community in meeting with institutional frames. Our involvement in the PD process allowed us to get first-hand insight into the intersection between community practices and national and municipal plans, policies and procedures.

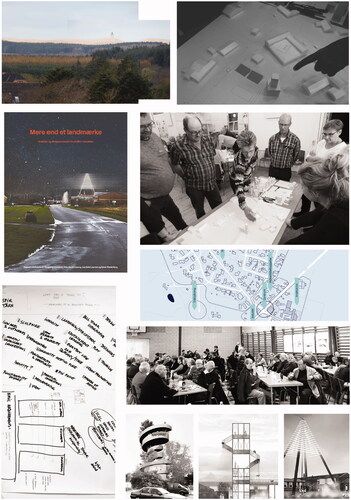

The PD process was a public experiment with a situated, responsive and creative inquiry (Baerenholdt et al. Citation2010) to foster collaborative change-making (Pink, Akama, and Fergusson Citation2017). A local development group (DG) initiated the collaboration between the researchers and the community. The DG reached out to the university after articulating its village vision to construct a 20-m-high tower at a central location in the village. The collaboration took the form of a PD process that developed as a manifold, semi-systematic urban design approach and evolved around the formation of the tower. It included, for example, site analyses, sketching, model making, public meetings, and theoretical reflections on rural architecture and physical planning—see for examples from the process. It centered on analyzing spatial conditions and the potential of the village and synthesizing these in three spatial design scenariosFootnote1.

Figure 1. Illustrative examples of artifacts and activities from the micro-level activity of the PD process. (Illustration: authors.).

By working with design artifacts, the analytical material was transformed into three possible tower designs. Their purpose was not to be solutions but rather scenarios that sparked conversation, raised questions, exposed and juxtaposed considerations among the actors about remembered pasts, experienced presents and anticipated futures of the village. By developing the design scenarios, we not only described and analyzed civic action but also influenced it; such involvement requires careful attention. Kelly (Citation2019) argues that in such a process, it is difficult to foresee potential ethical issues. In response, Kelly suggests that the researcher cultivates the virtues of cooperation, curiosity, creativity, empowerment and reflexivity. Accordingly, we directed our efforts toward establishing a transparent and open dialogue with the community and toward carrying out the process as a social and reflexive activity that invited as many viewpoints as possible, establishing a space for conversations around the conditions, contestations and possible futures of the village.

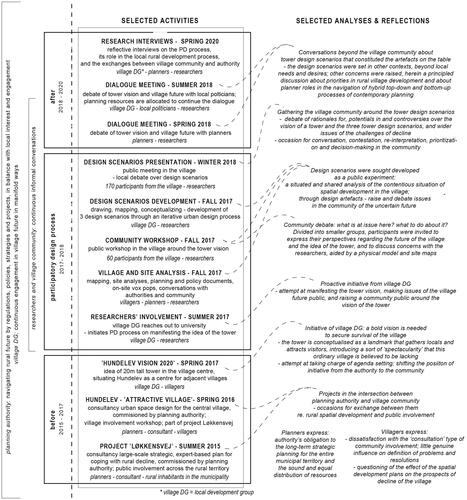

In this paper, the PD process is analyzed in relation to the wider trajectory of rural development and participatory processes in the village and the municipality. is an annotated illustration of the analyzed activities before, during and after the PD process, covering the years 2015–2020. The involved researchers engaged with various actors from the village as well local authorities at different times and in different ways. The illustration provides an overview of the empirical material, which includes the PD process itself, as well as analyses of plans, policies, procedures, and practices, and subsequent interviews with selected actors from the village and the authorities. After the PD process formally concluded in 2018, the researchers kept in contact with the DG and the planners, in the process of analyzing this particular intersection between the community and the policy administration. Key reflections from the analysis have been highlighted in the illustration.

Figure 2. Tracing and analyzing actions and interactions: Annotated illustration of the time, activities and actors, and analyses and critical reflections before, during and after the PD process. (Illustration: authors.).

Analyzing the site of controversy

Rural Denmark is experiencing an overall decline in workplaces and population. Rural areas lost 7% of their population in the period from 2007 to 2012 and 7.8% of their workplaces in the period from 2009 to 2011 (Ministry of Urban and Rural Affairs, Citation2013). Future projections suggest that this decline will continue, thereby affecting rural areas as places where people are able and willing to live and work.

Throughout Europe there have been many attempts to ensure rural economic development through industrialization programs or the relocation of public agencies to rural areas (Tietjen and Jørgensen Citation2016; Hospers and Syssner Citation2018). In Denmark, this is evident in, for example, the 1970s’ regional plansFootnote2, the recent relocation of governmental workplacesFootnote3 to the periphery, and the early subsidies from the national equalization programFootnote4.

However, in recent years a shift has emerged in Europe from focusing solely on governmental subsidies and grants to promoting a place-based development grounded in local strengths and possibilities (Hospers and Syssner Citation2018). In recent Danish rural policies, there is a prevailing focus on place-based qualities and potentials of the challenged rural areas as well as on the quality of life of their inhabitants. The aim is not growth per se, but to preserve these areas as attractive places to live, work and visit (Sloth Hansen, Møller Christensen, and Skou Citation2012; Ministry of the Environment Citation2013; Realdania and BARK Rådgivning A/S Citation2017; Laursen, Møller, and Knudsen Citation2017). As part of this shift, policy and planning measures have been allocated to the municipal level, by obliging rural municipalities to formulate a strategic rural district plan (Tietjen and Jørgensen Citation2016). In this approach, local actors play an increasingly important role. Place-based citizen engagement is considered a key resource to be mobilized in maintaining and creating livable and vibrant communities, and research has shown that local communities with resources such as good collaboration between stakeholders, strong networks and a common identity are more likely to achieve positive development than communities without these resources (Svendsen Citation2007).

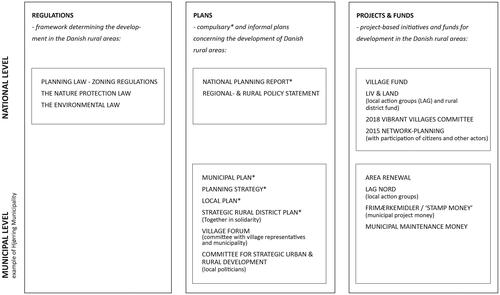

What we see is that many different actors seek to handle the uncertain rural situation, some of these from above—through policies and governmental programs at the national and municipal levels (see for an overview of the current policy and planning structure), and some from below—through civil, private, and cooperative initiatives. This happens in many different ways, in situated encounters of collaboration and contestation between institutional frames, people, artifacts, and activities.

Danish rural policy administration meets village community actions

We now turn to the case study to unpack an instance of the situated encounter between the public policy administration and the local community. In Hjørring Municipality, the planning authority handles rural development with regulation and guidance through compulsory and informal policies and planning documents (). The planning authority is recognized nationally for its strategic and progressive approach to declining rural areas. In 2015, as a signifier of this, it was awarded the Danish Urban Planning Prize for its innovative strategic plan for “differentiated” municipal development. Municipal rural policies focus on local place-based potentials through the mobilization of local communities, demonstrated in, for example, the Rural District Strategy that emphasizes that village development must rest upon local engagement and involvement (Hjørring Municipality Citation2017). However, planners express their awareness of the need to delicately balance the involvement and influence of local communities with the authority’s obligation to attend to a wide range of considerations of public character in relation to rural development, in this case the long-term strategic planning for the entire municipal territory and the sound and equal distribution of resources.

In the village of Hundelev, the local DG was established in 2017Footnote5; it includes committed and proactive representatives from local associations, who invest considerable voluntary resources in sustaining and developing the village as a good place to live for its 229 inhabitants (as of 2019).

The group is acutely aware of the challenge of decline facing the village. Their civic actions in response have been manifold over the years. In addition to active participation in public involvement procedures and processes initiated by the authorities, they have involved themselves through a broad range of practices with different expressions. These include informal meetings with planners and local politicians, engagement with local media, and the very visible initiation and completion of significant local projects, thereby securing the survival of the local school, developing and maintaining joint recreational facilities, and organizing cultural and social activities. In these processes, the DG also works to gather the wider village community around a concern for the future. The articulation of the village vision for the tower and the initiation of the PD process exemplify the group’s initiative to develop common trajectories for the whole village.

The group values an innovative and bold approach to rural planning in the municipality. In general, they indicate that they consider the planning authority’s motivations to be genuine when they are invited to join participatory processes (see He Citation2011 for a discussion of local governments’ incentives, regulation and control of public participation). However, they also express that the participation processes tend to have the character of a “consultation” (Arnstein Citation1969); in their experience, their voices and impact have been considerably constrained by the fact that definitions of key issues, problems, and possibilities for resolution have been produced prior to and outside of the public involvement process, and hence without community influence. The group also expresses skepticism toward the strategic, long-term municipal plans for spatial development; these tend to be considered a “waste of money” as the group experiences little or no actual improvement in terms of rural decline and local circumstances.

Below we analyze and discuss this case as an example of a site of controversy where a community group challenges the policies, plans, and procedures related to both spatial development and participatory processes and opportunities. Incongruities between the community and the administration come into play. These concern, for example, how much power is re-distributed through participation, and whether locals find that they can really influence their own conditions (Arnstein Citation1969). They also concern the encounter between planning expertise with official, comprehensive planning concerns for the entire rural territory and the local sense of urgency for development in a specific village. And they concern the here-and-now drive and engagement of villagers that meets long-term, bureaucratic planning. As adversaries, the planning authority and the local community both attempt to produce perceived favorable conditions. The significance of this encounter between authority and community only seems to increase as economic pressure on the Danish municipal sector and continued rural decline mean that development is increasingly relying on citizens.

Issue formation through the design thing

In the empirical case of the village community’s involvement in rural development, we experienced how the DG attempted to enact a public community concern through a more or less explicit articulation of issues of importance to the threats of local decline and an uncertain future. The vision of and local debates around the tower produced a Thing that contested several issue definitions. One was the authority planning, that is, the issue of rural spatial development. The community did not perceive this planning to be irrelevant, but the expert-based nuances of planning a rural region with de-growth and the allocation of resources to realize the plans appeared obscure to the villagers. They found a need to identify and develop issues themselves.

Taking our cue from the STS related literature introduced in the theory section above, as well as further deliberations on the roles and agency of design processes (Dunne and Raby Citation2013; Smith et al. Citation2016), we analyze the PD process as one of identifying, expressing, and contesting shared issues in the community. Through this lens, we can understand that issues are not pre-specified in sketches, models, and construction plans. Rather they emerge through them (Linde and Book Citation2014). When a design Thing takes the form of a building or another spatial project, we can follow Yaneva’s work on buildings as “multiverses” (Yaneva Citation2005, Citation2012) that bring out controversies and issues in gathering and raising questions, claims, and considerations. In absorbing and organizing issues of importance, buildings as design Things work as “dissipative entropic entities” (Yaneva Citation2005, 535).

Ripley, Thün, and Velikov (Citation2009) can help us elaborate on that conception of spatial design, and hence the role of design processes and artifacts in the articulation of shared issues. With reference to Latour’s work on “matters of concern” (2004), they argue that architecture can be carried out as a critical analysis of a situation, by organizing and orchestrating complex interrelated variables that flow together in a spatial project. This is an understanding of design as a process that begins with the contextual situation and works to develop and articulate a design proposition in and through its relation to multiple issues. The design process and proposition are richly diverse, situated, and engaged with their own contradictions and controversies. It is design used as “a way of exposing the conditions, forces and potentials that might become activated within a proposition” (Latour Citation2004, 6). Hence, they argue, the design artifacts of a proposition do not only concern the visualization of “future architectures” (the object) but “future worlds” (the wider conditions and issues entangled in the object).

In the collaborative process of developing the tower scenarios in the village, and in the subsequent discussions of them, the tower scenarios were used as a process of “discovery” (le Dantec and DiSalvo Citation2013; see also Schoffelen et al. Citation2015). This was an attempt to concretize local experiences and opinions on rural conditions and strategic considerations and make them available for collective scrutiny. Through these concepts, we can understand the design scenarios as dialogical and provisional assembly points. They provoked various practices and expressions by different actors, who took part in the process and brought in their own attitudes and knowledge. Through words, illustrations and models, the vision of the tower—and the rural circumstances entangled with that vision—were exposed, examined, elaborated and made transparent, accessible and experiential by the participants. In developing the scenarios and in the following circulations and discussions of them, we saw local and wider rural conditions and concerns being debated.

With the design Thing, then, the powerful position of taking initiative and defining issues, problems and resolutions shifted from the authority to the community. The “commanding position” of design in defining issues extended to the community, so to speak.

Manifesting constructive criticism toward policy and planning

Regarding the spatial project, municipal planners questioned the idea of the tower as an expression of local self-interest and lobbyism. The planners found themselves seeking to accomplish a sound, equal and comprehensive planning of the wider rural area. Accordingly, one concern of the planners was the tower becoming a largely symbolic manifestation of what was perceived as a “village victory,” that is, of Hundelev’s success as a local community, possibly at the expense of other village communities who could not mobilize such initiative and influence. An incisive question was raised as to why a tower would be best placed in Hundelev, and not in one of the other neighboring villages, which suffer from the same, if not bleaker, future projections.

From the perspective of the DG, however, this civic action represented repressed local knowledge and desires. They pushed for and dared to reimagine their future by themselves, utopian as it may have been. Levitas’ work in Utopia as Method (2013) offers a path to understanding this. She argues that utopian thinking is not irrelevant speculation; rather it constitutes legitimate and useful knowledge, “not as a new, but as a repressed, already existing form of knowledge about possible futures” (Levitas Citation2013, xv). Such thinking does not necessarily engage with entirely new models, distanced from the present, but with potential “alterities of the present” (Pink, Akama, and Fergusson Citation2017) in developing based on current site conditions, local desires and in response to circumstances. Design Things, in this form of speculative expression, are a form of “archaeology” of the past and present. They excavate fragments and recombine them into a new whole: “They are necessarily the product of the conditions and concerns of the generating society, so that whether they are placed elsewhere or in the future, they are always substantially about the present” (Levitas Citation2013, xiv).

In constructing and debating their own design, participants solicited constructive criticism based on what they wanted—and not solely on what they did not want. By enabling participants to take this sort of initiative and actively engage with their conditions and their future, the design Thing of the PD process contributed to the manifestation of constructive criticism of circumstances and developments. Participants used the design Thing to uncover new possibilities and insights and raise questions about what could and ought to change. As such, it helped to empower participants to engage in a process of resistance to what they experienced and anticipated as consequences of policy and plans, and to use the design Thing to gather and critically reimagine a counter-image.

Urry (Citation2016) found that the capacity to “think futures” is emancipatory, as it enables people to break with routine. In his work on scenarios, he refers to the futurist Buckminster Fuller, who found that, though the future is difficult to change, it may be possible to construct an alternative future model to work toward. In the context of uncertain rural futures in Denmark, Møller (Citation2016) found that the major challenge to the future of the villages is to break with linear thinking and “to see the future as anything but an extension of the present” (23).

With the counter-image of the community, the DG acted on their experience of limitations to their possibilities to participate in defining their future. The counter-image contested not only the plans for spatial development, but also the issue of participation policies and procedures. Seen as a response to their dissatisfaction with the actual procedural public participation, the tower design Thing was an attempt to move out of a “consulting” position in reaction to municipal initiatives, to a position of taking charge of issue formation and expressing a constructive critique.

The tower vision and the PD process were, in this perspective, a manifestation of the DG’s attempts to raise an influential local public comprising spatial-political agents, who can resist and critically re-imagine the projected trajectory of decline in their village. They attempted to push for the public-ization of issues by initiating a process that could engage the wider community, produce tangible counter-images and build their capacity to navigate interactions with the planning authority. They contested the limits of public involvement and the lack of impactful local spatial development and insisted on organizing as a collective to raise and identify issues in the controversy of how participatory rural planning can be carried out in meaningful and impactful ways.

Discussion: uneven and tentative formations within the community—between things and things

Through the concept of design Thing, we have highlighted how design worked to infrastructure a process of forming issues and forming a public in the community. This conception outlines the distinction between treating designed things as “fixed products” and treating designing as ongoing infrastructuring. In their work, le Dantec and DiSalvo (Citation2013) stress that this distinction is subtle but important. Yet, they also find that one of their own cases suggests that it is possible that these two distinctive modes of PD for publics can complement each other and coexist. Taking our clue from this suggestion, we now turn to a discussion of how this case of issue and public formation through a design Thing is also a process of unevenness and contestation within the community itself.

In tracing and analyzing the actions and interactions in Hundelev, we saw that the PD process and the tower scenarios were used in two ways simultaneously: as a Thing to form issues and a public, and as a spatial project with an object, a “thing,” as a tangible result—in the form of a tower design.

When we entered the process, this ambiguity between producing a thing and infrastructuring a Thing was already present. To give priority to the infrastructuring mode of designing, and thus to avoid dominance of the problem-solving mode of PD (i.e. seeking a response to already settled issues), we strived to make the process and artifacts around the tower sufficiently open for contestation and re-interpretation, so entangled issues in and beyond the tower vision could be articulated. Our approach was to engage the PD process as a public experiment of designing three scenarios (instead of, e.g. one design proposal). There is an important objective here: to “underdesign” the thing, so to speak, in the pursuit to avoid limiting the participants’ understanding of what can be done (Linde and Book Citation2014). In this way, we sought to produce socio-technical resources for the participants to develop their issues, using design as the starting point, instead of the endpoint, in formulating intentionality (Linde Citation2014; le Dantec and DiSalvo Citation2013).

However, in this process, it is necessary to question if and how a design Thing can profoundly and genuinely embrace conflict and difference in forming issues and publics. Here, we cannot engage fully with this question. But we will attempt to open an engagement by returning briefly to Marres (Citation2007) and le Dantec and DiSalvo (Citation2013), who propose the concept of “attachments” as a productive and dynamic way to consider how issues are opened up for involvement, in distinction to ways of framing issues that tend to prevent genuine involvement. Le Dantec and DiSalvo assert that infrastructuring should be seen as an ongoing process of shaping attachments “by way of a relationship to the material product” (Citation2013, 257). This process is not confined to an a priori (and perhaps controversial) PD process and its procedures. Rather, it intertwines with the activities and interactions that surround and follow that process, for example, the everyday interpretation, adaptation, mediation, contestation and re-designing of the thing.

In her argument for the importance of an issue-oriented and object-oriented perspective on public involvement, Marres suggests that procedural events of public involvement are occasions for other forms of public involvement which are in fact more significant: the broader and less ordered practices of articulating public issues. These practices involve the discovery and expression of attachments—commitments and dependencies—between people, and between things and people. Accordingly, le Dantec and DiSalvo find that infrastructuring through PD works as a “scaffolding for affective bonds that are necessary for the construction of publics” (Citation2013, 260). Artifacts of the design Thing are objects to which those bonds or attachments can adhere and possibly be sustained. They are objects that do not frame issues but invite attachment to issues, engagement and motivation to action.

However, the question of who defines issues is pertinent in the interactions within the community, just as we saw above that it is pertinent in the relationship between the authority and the community. When the DG initiated the PD process around the design of a tower, they worked from their established vision and in the particular procedural setting of the PD process, seeking to enroll the wider community in their cause. Framing issues through that vision and through those procedures was limiting, in that it did not allow a fully open process of issue and public formation in the wider community.

During the PD process and afterwards, this ambiguity was at play, at times obscuring the collective process of issue and public formation. Some villagers, in particular those involved with the DG, were willing to enter the PD process on the terms of a long-range process of shared issue formation and capacity building. At the same time, however, they—and other villagers who conceived of the PD process as a problem-solving endeavor—were keen to push for linear and short-term progress toward realizing their goal of a tower in the village center.

While the village process is an example of how, on this small community scale, several committed people can attempt to gather others to develop collective issues and seek to mobilize and take action as a specifiable group, it is also clear that the village community is not one coherent public, and that the formation of publics is non-linear and uneven. While the wider community seemed to support the PD process and the DG’s activities and commitment in general, the PD process appears today as a tentative conglomeration of actors and local controversies. The interviews with the DG and planners in early 2020 proved this point. There is no tower yet constructed in Hundelev, but the issues that became entangled with it remain and are part of a broader range of public practices and local controversies, including individual opinions, loose connections and fragmentation. In these processes, it is probable that several trajectories of the formation and public-ization of issues will take shape and dissolve around the community’s concerns for the future of the village. It is also likely that smaller interest groups and cases of self-interest will be present, just as it will be difficult to distinguish public formation from less genuine forms of lobbyism (see Linde Citation2014; Marres Citation2007; Arnstein Citation1969). This continues to be a concern for the municipal planners, who are striving to navigate the complex field of municipal interests and public involvement, meeting a strong local advocacy group and their attempts to form a public, but where the wider local community is less distinct to the planners.

These observations speak to the multiplicity and instability of publics, put forth in Dewey’s work. Accordingly, DiSalvo (Citation2009) finds that publics have an inability to form effectively; they tend to remain unformed and tentative. This is so, even though strong issues of collective character exist, as those issues tend to resist collective definition and mobilization.

In Hundelev, a village community facing the bleakness of uncertain rural conditions, the DG has identified the urgent collective issue of mobilizing as influential local advocates, capable of interacting with the institutional frames of rural development with skill and power in the pursuit of producing perceived favorable conditions for the village. However, issue definitions are unevenly distributed, and coalitions remain tentative, always on the brink of re-forming within the complex relationships between people, artifacts, and activities.

Conclusions

We have analyzed an instance of civic action at the site of controversy where participatory-oriented policy meets local community in the Danish rural territory. The significance of this encounter between policy and civic action only seems to increase as rural decline and economic pressure on the municipal sector means that village livelihood and development increasingly rely on citizens. In this rural situation, citizens practice experimental means of public involvement in response to perceived problematics about institutional policies, plans, and procedures that attempt to tackle the uncertainty of the rural future.

Our analysis showed that a micro-level PD process was a gathering point for practices in the community, and that it supported local ongoing efforts that opposed perceived consultation-only involvement practices and sought to engage in issue articulation, public-ization of issues and attempts at raising a specifiable village public.

When considering rural participatory policy in an agonistic site where issue formation necessarily happens in unordered public sites beyond the limits of procedures, it cannot simply target short-term consensus on specific issues. It must consider the slow-paced, pluralistic character of collective future-making where numerous and diverse issues and publics continue to emerge, form, and re-form.

The paper has considered that these formation processes are not linear and consensus-driven; rather, publics are inseparable from the conditions of their origin in that they are brought into being and qualified through and in response to issues in context. Publics are messy, uneven and contingent constellations. The analysis and discussion entail the following learning points about PD for publics.

First, that PD holds promises for infrastructuring the formation of issues and publics. In the case study, we discussed that a PD process can work as a socio-material design Thing that gathers people and issues in a collective scrutiny of conditions and possibilities for the future.

Second, that the formation of publics includes issue identification and issue expression. In our case, we saw that the locally-initiated PD process of the design Thing was an attempt to contest institutional issue definitions and to move the power to define issues from the authority to the community.

Third, that PD for issue and public formation can help participants to build the capacity and power to solicit constructive criticism based on what they want—and not solely on what they do not want. In this case, we saw that the design Thing was a manifestation of the development group’s attempts to raise as influential spatial-political agents, who could resist and critically re-imagine the projected trajectory of decline in their village.

Fourth, that issue and public formation is characterized by unevenness and tentativeness. In our case study, we saw that issue definition within the community was unevenly distributed, and coalitions remained tentative, with design and artifacts as a scaffolding of dynamic attachments between people, things, and activities.

Acknowledgements

The PD process described in this paper was conducted by the authors with assistance of research intern Chrysavgi Konstanti, whom we thank for her contribution. Also thank you to Line Traeholt Hvingel for sharing her insights on the Danish planning and policy system. Further, we thank the local participants from the village and planners from the local authority for the engaged collaborative production of the design scenarios as well as for participating in interviews and meetings. Not least, thank you to the organizers and participants at the Workshop on Participatory Policy Design, at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, in March 2020, and to two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Report on the three design scenarios is available at: vbn.aau.dk/da/publications/mere-end-et-vartegn-analyser-og-designscenarier-for-lokalsamfunds (in Danish).

2 The regional plans (Danish: egnsplaner) intended to create new industries in rural areas, to support economic growth through the creation of workplaces. An example is the governmental support to the Danish windmill industry, initiated to create jobs in the western parts of Jutland (Gaardmand Citation1993).

3 In 2015, the government enacted a policy to relocate governmental workplaces in an attempt to create employment and growth outside the capital region.

4 This refers to the national reform on the equalization of resources between local authorities, settled between the government and the parties of the Danish Parliament, most recently agreed upon in May 2020.

5 Only recently, and after the PD process ended, in 2020, the DG has been formalized as an association with by-laws.

References

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Baerenholdt, J. O., M. Büscher, J. D. Scheuer, and J. Simonsen. 2010. “Perspectives on Design Research.” In Design research. Synergies from interdisciplinary perspectives, edited by J. Simonsen, J. O. Baerenholdt, M. Büscher and J. D. Scheuer, 1–15. London: Routledge.

- Bjögvinsson, Erling, Pelle Ehn, and Per-Anders Hillgren. 2012. “Design Things and Design Thinking: Contemporary Participatory Design Challenges.” Design Issues 28 (3): 101–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00165.

- DiSalvo, C. 2009. “Design and the Construction of Publics.” Design Issues 25 (1): 48–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/desi.2009.25.1.48.

- DiSalvo, C. 2016. “The Irony of Drones for Foraging: Exploring the Work of Speculative Interventions.” In Design Anthropological Futures, edited by R. C. Smith, K. T. Vangkilde, M. G. Kjaersgaard, T. Otto, J. Halse, and T. Binder, 139–154. London: Bloomsbury Press.

- DiSalvo, C., T. Lodato, T. Jenkins, J. Lukens, and T. Kim. 2014. “Making Public Things: How HCI Design Can Express Matters of Concern.” In CHI 14 Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Toronto: ACM Press.

- Dunne, A., and F. Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Gaardmand, A. 1993. Dansk Byplanlaegning 1938–1992. Copenhagen: Arkitektens Forlag.

- He, B. 2011. “Civic Engagement through Participatory Budgeting in China: Three Different Logics at Work.” Public Administration and Development 31 (2): 122–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.598.

- Hjørring Municipality. 2017. Samling Og Sammenhold: Landdistriktsstrategi for Hjørring Kommune. Hjørring: Hjørring Kommune.

- Hospers, G. J., and J. Syssner. 2018. “Introduction – Urbanization, Shrinkage and (in)Formality.” In Dealing with Urban and Rural Shrinkage: Formal and Informal Strategies, edited by G. J. Hospers and J. Syssner, 9–16. Zurich: Lit Verlag.

- Huybrechts, L., H. Benesch, and J. Geib. 2017. “Institutioning: Participatory Design, Co-Design and the Public Realm.” CoDesign 13 (3): 148–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355006.

- Kelly, J. 2019. “Towards Ethical Principles for Participatory Design Practice.” CoDesign 15 (4): 329–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1502324.

- Latour, B. 2004. “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry 30 (2): 225–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/421123.

- Latour, B. 2005a. Re-Assembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, B. 2005b. “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik, or How to Make Things Public.” In Making Things Publics. Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by B. Latour and P. Weibel, 14–41. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Laursen, L. H., J. Møller, and M. Knudsen. 2017. “Forsknings- Og Udviklingsprojekt om muligheder og barrierer for at oprette og udvikle landsbyklynger.” In Architecture & Design Series (A&D Files). 105th ed. Aalborg: Aalborg University.

- Le Dantec, C. A., and C. DiSalvo. 2013. “Infrastructuring and the Formation of Publics in Participatory Design.” Social Studies of Science 43 (2): 241–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312712471581.

- Levitas, R. 2013. Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Linde, P. 2014. “Emerging Public: Totem-Poling the ‘We’s and ‘Me’s of Citizen Participation.” In Making Futures: Marginal Notes on Innovation, Democracy, and Design, edited by P. Ehn, E. M. Nilsson, and R. Topgaard, 269–276. Cambridge: the MIT Press.

- Linde, P., and K. Book. 2014. “Performing the City: Exploring the Bandwidth of Urban Place-Making Through New-Media Tactics.” In Making Futures: Marginal Notes on Innovation, Design, and Democracy, edited by P. Ehn, E. M. Nilsson, and R. Topgaard, 277–302. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Marres, N. 2007. “The Issues Deserve More Credit: Pragmatist Contributions to the Study of Public Involvement in Controversy.” Social Studies of Science 37 (5): 759–780. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312706077367.

- May, P. J. 1991. “Reconsidering Policy Design: Policies and Publics.” Journal of Public Policy 11 (2): 187–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X0000619X.

- Ministry of the Environment. 2013. Green Transition – New Possibilities for Denmark. Copenhagen: Danish Ministry of the Environment.

- Ministry of Urban and Rural Affairs 2013. Regional-og landdistriktspolitisk redegørelse 2013 (Regional and rural policy report 2013). Retrieved from. https://www.livogland.dk/files/dokumenter/publikationer/regional-_og_landdistriktspolitisk_redegoerelse_2013.pdf accessed May 2020

- Møller, J. 2016. “Udfordringer og mulige løsninger for fremtidens landsbyer.” Futuriblerne 44 (5–7): 21–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.7146/ntik.v5i3.25787.

- Mouffe, C. 2004. “Pluralism, Dissensus and Democratic Citizenship.” In Education and the Good Society, edited by F. Inglis, 42–53. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pink, S., Y. Akama, and A. Fergusson. 2017. “Researching Future as an Alterity of the Present.” In Anthropologies and Futures: Researching Emerging and Unknown Worlds, edited by F. Salazar, S. Pink, A. Erwing, and J. Sjöberg, 133–150. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Realdania and BARK Rådgivning A/S. 2017. Stedet Taeller: Perspektiver og erfaringer. København: Tarm Bogtryk A/S.

- Ripley, C., G. Thün, and K. Velikov. 2009. “Matters of Concern.” Journal of Architectural Education 62 (4): 6–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1531-314X.2009.00999.x.

- Schoffelen, J., S. Claes, L. Huybrechts, S. Martens, A. Chua, and A. Moere. 2015. “Visualising Things. Perspectives on How to Make Things Public Through Visualisation.” CoDesign 11 (3–4): 179–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1081240.

- Sloth Hansen, S., S. Møller Christensen, and K. Skou. 2012. Mulighedernes land: Nye veje til udvikling i yderområder. Copenhagen: Realdania.

- Smith, R. C., K. T. Vangkilde, M. G. Kjaersgaard, T. Otto, J. Halse, and T. Binder, eds. 2016. Design Anthropological Futures. London: Bloomsbury Press.

- Svendsen, G. L. H. 2007. Hvorfor klarer nogle udkantssamfund sig bedre end andre? En analyse af udnyttelsen af stedbundne ressourcer i to danske udkantssamfund. IFUL REPORT 2/2007. Esbjerg: Syddansk Universitet, Institut for Forskning og Udvikling i Landdistrikter.

- Tietjen, A., and G. Jørgensen. 2016. “Translating a Wicked Problem: A Strategic Planning Approach to Rural Shrinkage in Denmark.” Landscape and Urban Planning 154: 29–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.01.009.

- Urry, J. 2016. What is the Future? 1st ed. Cambridge, Malden: Polity Press.

- Yaneva, A. 2005. “A Building is a Multiverse.” In Making Things Publics. Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by B. Latour and P. Weibel, 530–535. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Yaneva, A. 2012. Mapping Controversies in Architecture. London: Routledge.