Abstract

This paper explores how co-design can support the analytical, operational, and political policy capacities of government bodies. It specifically covers the policy capacities for public transport of local government units (LGUs) in the Philippines which was then mainly undertaken by the national government. The study area is Pasig City which has its own Pasig Bus Service (PBS) operated by its City Transportation Development and Management Office (CTDMO). To assess and improve the PBS, a design thinking workshop was held with CTDMO and commuter representatives in creating an information exchange platform. Discussions from the workshop were subjected to thematic analysis and coding to determine the kind and frequency of policy capacities expressed. Challenges in conducting the workshop were also identified along with recommendations to ensure the effectiveness of co-design in improving policy capacities of participants and the agency involved.

1. Introduction

Sustainable transportation is a great challenge in Asian countries such as the Philippines where there are increasing population and densities in their cities. With the global average annual population growth rate of 2.4% between 2000 and 2016, forty countries in Asia had cities with growth rates higher than 6%, compared to most developed countries in Europe which have declining populations (United Nations Citation2016). Alongside, global trends and future projections likewise show South and East Asia with the largest vehicle growth leading to heavy traffic, and high levels of fuel consumption and pollution (Ieda, Citation2010).

Likewise, there are several issues in government priorities, institutional arrangements, and implementation of policies on transportation. Low-income Asian countries often concentrate on road infrastructure than public transport. In the Philippines, investments in the former are seven times greater than the latter, and informal indigenous public transport modes which are more accessible to the poor are disregarded or have more restrictive policies compared to private vehicle ownership (Barter, Kenworthy, and Laube Citation2003; Mateo-Babiano Citation2016). Looking on public bus services, there is a poor regulatory framework with the prevalence of small private operators leading to market inefficiencies, and aggressive drivers owing to the “boundary system” where their daily income is based on their number of passengers. Underlying this in developing countries like Sri Lanka and the Philippines are the bus operators who are well-connected personalities, military officers, celebrities, or are politicians themselves, hence the absence of strong political commitment and resistance to rationalize public bus transport (Domingo, Briones, and Gundaya Citation2015; Sohail, Maunder, and Cavill Citation2006).

Studies also identify poor inter-government coordination among the various agencies handling transport, and in different levels of government (Rahman and Abdullah Citation2016; Sohail, Maunder, and Cavill Citation2006; Romero et al. Citation2014). Moreover, international development organizations who provide financing and technical expertise have high influence on the policy directions and transport priorities of developing countries (Wijaya and Imran Citation2019). This, along with top-down approach of in planning and policymaking, give limited opportunities for the public to participate, which often only occur in the latter stages where these are about to be passed or implemented (Ieda, Citation2010; Sohail, Maunder, and Cavill Citation2006).

Amidst recent shifts to decentralization of transport management from national to local agencies in Asian countries, the low capacities of local governments remain with the lack of competent personnel and adequate financial resources (Wijaya and Imran Citation2019), and limited mechanisms to acquire and analyze data, especially on assessing the quality of service of public transport (Sohail, Maunder, and Cavill Citation2006). In the Philippines, regulatory reforms on public transport were set with the Public Utility Modernization Program (PUVMP) guided by Department Order No. 2017-01: “Omnibus Guidelines on the Planning and Identification of Public Road Transportation Services and Franchise Issuance” (Department of Transportation, Citation2017). It devolved the function of route planning to local government units (LGUs) requiring them to conduct route rationalization studies and submit their Local Public Transport Route Plan (LPTRP). Local councils are moreover called to review their transport policies, and amend, revise, or repeal those that conflict with the Guidelines and related national policies (Department of Interior and Local Government & Department of Transportation, Citation2017). However, the implementation of the policy has been snail-paced, with deadlines being extended since most LGUs failed to submit their LPTRPs considering that they used to have limited scope in transportation (Alimondo Citation2019; Baquero and Magdadaro Citation2019; Romero et al. Citation2014)

To promote good governance, a comprehensive Transport Governance Toolkit has been made by the World Resources Institute (WRI) and Prayas Energy Group. Piloted in different states and cities in India, the toolkit details indicators in the areas of transport policy, planning, standard setting, budgeting, and policy and implementing bodies which evaluates their capacities, transparency, accountability, and level of public participation (Sridhar, Gadgil, and Dhingra Citation2019). There have also been research and initiatives using co-production and co-design to promote the engagement of various stakeholders in the identification of transport issues and solutions, mostly made in developed countries such as the UK (Mitchell et al. Citation2016), Sweden (Pettersson, Westerdahl, and Hansson Citation2018), and Italy (Ciasullo, Palumbo, and Troisi Citation2017).

On the other hand, the practice of co-design in the Philippines is not as widespread, especially in governance and public policy. Co-design initiatives in the country have been started by design companies such as IDEO, Tandemic, and On-Off Group with trainings for schools and businesses to improve their services, and projects with government agencies such as the Department of Health on improving sanitation in rural areas (GMA News Citation2013; Tandemic Citation2018; Rappler Citation2016). Meanwhile, there is a study by Millan (Citation2019) comparing design thinking with unstructured consultation in developing a citizen mobile application in Iloilo City, Philippines.

This paper seeks to enrich existing literature and practice by exploring the potential of co-design in enhancing the capacity of local governments. Considering the role of bureaucratic agencies in analyzing issues and recommending, implementing, and evaluating policies as they work with policymakers (Di Francesco Citation2000; Stahl Citation1981; Howlett and Wellstead Citation2011), it looks into the policy capacity of a local transport agency, consisting of analytical, operational, and political capacities, present at individual, organizational, and systemic levels (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2015). As a study area, Pasig City in the Philippines was selected because it has been instituting local transport innovations such as the establishment of a City Transportation Development and Management Office (CTDMO) and operation of the Pasig Bus Service which are both uncommon since such office is not required in the Local Government Code of 1991 (Philippine Congress 1991) and public bus services are mainly operated by the private sector. The succeeding parts discuss related literatures on policy capacity and co-design; the methodology and findings of the Pasig City case study; and conclusions and recommendations.

2. Convergence of policy capacity and co-design

Across the world, several design policy labs, groups, or programs have been established either led by or in partnership among different sectors of society, specifically, governments, non-government organizations, private sectors, and the academe directed to incorporate co-design in policy. The Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) in Europe engaged scientists, researchers, communities, and other stakeholders in a bottom-up approach to ensure science, technology and innovation policies are relevant to societal needs (Deserti, Rizzo, and Smallman Citation2020). In the United Kingdom (UK), there is a UK Policy Lab and Design Council involved in areas such as the UK Criminal Justice System and UK Medical Service where stakeholders participated in design and scenario workshops to guide policymaking, while in South Korea, there is a Citizens’ Policy Design Group with projects on developing consumer-oriented policies, and resolving the migration of rural youth to cities (Koo and Ahn Citation2018; UK Design Council 2020).

In public transport, a Living Lab was constituted in Sweden composed of a wide range of stakeholders such as national and local transport authorities, bus operators, private and non-government organizations, and the academe who assessed public transport conditions and drafted policy guidelines (Pettersson, Westerdahl, and Hansson Citation2018). Meanwhile, Ciasullo, Palumbo, and Troisi (Citation2017), engaged stakeholders in Bologna, Italy through telephone and online surveys, and focus group discussions which facilitated the identification of mobility needs and design of an information exchange platform to guide decision-making on different transport modes. In another study by Mitchell et al. (Citation2016), co-design was found to provide a systematic process and holistic perspective in generating proposals for sustainable transport compared to the traditional consultation method.

A definition of co-design for policymaking is given by Blomkamp (Citation2018) as a “design-led process involving creative and participatory principles and tools to engage different kinds of people and knowledge in public problem solving” with three key components: a process with iterative stages of understanding, ideation, prototyping, testing, and refinement; underlying principles of participatory design and empowerment; and practical and interactive tools. With these, it can help address the various factors that can lead to poor policy design such as the lack of understanding of the problem, unfamiliarity with the implementation environment, unclear and contradicting goals, insufficient data, and lack of political support (Hudson, Hunter, and Peckham Citation2019).

This paper explores the significance of co-design in policymaking, in terms of enhancing policy capacity. “Policy capacity” or “policy analytical capacity” attempts to describe the link between policy development at the bureaucratic level and policy decisions taken by elected and appointed government officials. In the simplest example of the heuristic policy cycle, politicians establish a policy goal, and then rely on their civil servants—permanent employees of the state who are largely unaffected by elections, lobbying, and public pressure—to investigate options for achieving the politicians’ goals. These civil servants then forward the results of their work to the political executive to consider for policy implementation. As Howlett and Wellstead (Citation2011) point out, in practice, policy analysts can no longer be seen simply as technical experts who use specialized techniques to solve specific policy problems as there are now more generalists who engage in a variety of activities that are crucial to the policy process. Stahl (Citation1981) identifies several areas in which public administrators should be equipped with on policy-making: knowledge on the law to understand social values and provide standards for evaluation of public policy; use of analytic tools to anticipate, control, make choices, and evaluate policy consequences; and awareness on power relations among stakeholders.

Earlier writers have used different or inexact terminology: Polidano (Citation2000) uses the term “public sector capacity,” Di Francesco (Citation2000) refers to “policy advice,” and Thissen and Twaalfhoven (Citation2001) refer to “policy analytic activity.” However, these authors have the same general intent as is pursued in subsequent literature that has converged on the term “policy capacity” that reflects the ability of civil servants to produce useful advice and to effectively communicate that advice to government decision makers. This paper hinges on the definition by Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (Citation2015) of policy capacity as the “set of skills and resources – competences and capabilities – necessary to perform policy functions.” It has been categorized into analytical, operational, and political capacity, and present at individual, organizational, and systemic levels.

Analytical capacity at the individual level refers to the ability to acquire and process data on the policy issue and its causes, conduct thorough analysis of options, formulate sound plans for implementation, and carry out detailed policy evaluation (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2018; Hartley and Zhang Citation2018). At the organizational level, aside from having individuals with analytic capacity, this includes having a system of collecting and analyzing data such as an e-governance platform (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2018). It can also be measured through data availability which at the system level can further be enhanced with the accessibility of data to civil society and private sectors, and their participation in contributing data essential for monitoring policy implementation, identifying policy issues on the ground, and validating other data sources using citizen mobile applications employing crowdsourcing data (Hsu Citation2018).

Meanwhile, operational capacity of individuals includes leadership and managerial skills such as planning, staffing, budgeting, delegating, and coordinating. For organizations, this centers on mobilizing and deploying human and financial resources to perform policy functions which covers effective communication within the agency and having standard operating procedures, while at the system level, this can be measured by the level of coordination with other agencies and civil society (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2018; Hartley and Zhang Citation2018).

Lastly, political capacity at the individual level requires knowledge on policy processes, understanding of interests of different stakeholders, and skills in communication, negotiation, and consensus building. This includes, in organizations, a good working relationship with politicians, as well as two-way information exchange mechanisms between the government and citizens. This is expounded at the system level with the existence of an active civil society and their participation in the policy process, the political accountability of government, and level of trust in it (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2018; Hartley and Zhang Citation2018).

Given its iterative process, participatory principles, and interactive tools, co-design can play a significant role in enhancing policy capacities across levels and sectors. This study seeks to fill the gaps in analyzing co-design in policy since most studies relate it with the policymaking process. There are discussions on the different tools of co-design such as environmental scanning, participant observation, open-to-learning conversations, mapping, and sensemaking, and their contribution in problem definition, agenda setting, policy formulation, adoption, implementation, and evaluation (Mintrom and Luetjens Citation2016; Evans and Terrey Citation2016). Organizational ethnography has been used by Kimbell (Citation2015) to analyze initiatives by the UK Policy Lab, and comparisons have likewise been made on experiences of Western and Asian countries on applying co-design alongside the policy process (Koo and Ahn Citation2018).

Culling from these studies, the convergence of co-design and the components of policy capacity is also present. In terms of analytical policy capacity, it allows for the consideration of new or vague policy issues, therefore leading to a broader understanding and sharper definition of policy problems (Evans and Terrey Citation2016; Mintrom and Luetjens Citation2016; Kimbell and Bailey Citation2017). Its various creative activities require the participation of stakeholders in all stages of the co-design process, thereby strengthening evidence-based decision-making, especially of the individual analytical capacity level of participants from the government. These would also have an effect to citizens’ analytical capacity, as these enable them to better make sense of and articulate their experiences and concerns (Kimbell Citation2015).

On developing operational policy capacity, the process of prototyping can be significant in portraying policy implementation and possible issues with stakeholders. While this is a step to refine and redesign the selected alternative (Brown Citation2008), it can also reinforce the operational capacity of individual participants from the government, as well as at the organizational level of the implementing agency, as this can let them prepare, re-align, organize, or acquire the needed human, financial, technical and other resources to ensure that the proposed policy will be carried out well (Kimbell and Bailey Citation2017; Koo and Ahn Citation2018; Evans and Terrey Citation2016).

Finally, co-design can enhance political policy capacity as it opens up policymaking to different sectors inside and outside government, and initiating learning relationships among them. It fosters empathy, especially of individual policymakers and bureaucrats, to the various problems of the marginalized, and the effect of existing policies to them (Mintrom and Luetjens Citation2016). Its interactive and creative communication tools likewise elicit active participation from stakeholders and can lower hierarchies among participants (Kimbell Citation2015). Since citizens and other stakeholders are involved, it fosters political support for selected policy actions that are outputs of the co-design process and builds citizens’ trust to the government at the organizational and system levels (Evans and Terrey Citation2016).

While present cases of co-design activities indicate that it affects policy capacity mostly at the individual and organizational levels, with a long way to go to create impacts at the systemic level (Lewis, McGann, and Blomkamp Citation2020; Deserti, Rizzo, and Smallman Citation2020), co-design has manifested strengths in ways that traditional processes have fallen short, thereby giving more opportunities for enhancing policy capacity. A summary of how co-design can develop policy capacity is presented in .

Table 1. Co-design in Developing Policy Capacity.

3. Enhancing local public transport policy capacity through co-design in a Philippine local government unit

3.1. Study area: Pasig city

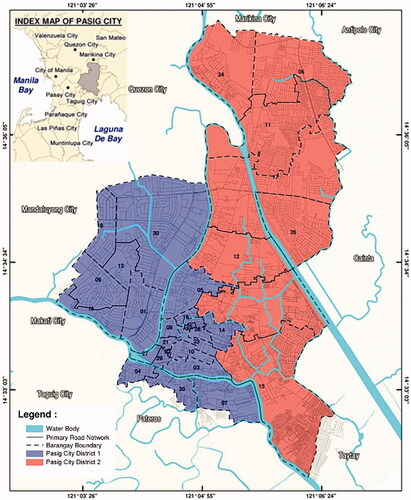

Pasig City, the study area for this paper, lays approximately 12 kilometers east of Manila, sprawled along the banks of Marikina and Pasig Rivers on the southeastern end of Pasig River, bounded by Quezon City and Marikina City on the North, Mandaluyong City on the West, Makati City, Pateros and Taguig on the South, Cainta and Taytay (Province of Rizal) on the East (). The total population of the city based on the 2015 census is 755,300 with a population growth rate of 2.31% making it the 4th largest city in Metro Manila (PSA Citation2016). Its economy was spurred by the development of the Ortigas Center Business District (CBD) which has attracted business investments and people seeking employment. While the City has been continuously urbanizing, the efficiency of its public transport is found to remain at low levels according to the Pasig City CBD Land Use and Transport Study, Comprehensive Transportation and Traffic Plan (TTPI & UP PLANADES Citation2011). Air pollution is furthermore a concern as the Pasig City air monitoring station of the Environmental Management Bureau ranked 4th with the highest level of total suspended particles (TSP) among its 10 stations in Metro Manila (PSA Citation2016).

Figure 1. Pasig city administrative map. Source: Pasig City Comprehensive Land and Water Use Plan 2015–2023 (Pasig Government Citation2015).

Pasig City is the interest of this study since its local government introduced several transport developments in response to the abovementioned challenges. It created the City Transportation Development and Management Office (CTDMO) which is uncommon in many LGUs in the country. The CTDMO has responsibilities such as the collection of transport data, analysis of public transport supply and demand, and evaluation of public transport routes within and those traversing the city, which are essential and aligned with the Omnibus Franchising Guidelines.

Moreover, with the desire of the city government to lessen car use and traffic, and improve air quality, the City Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) launched in 2016 the Pasig Bus Service (PBS). It first began to service CBD commuters and has expanded in 2017 to provide morning and evening services for Pasig City Hall employees, along with an additional four (4) new routes. Although it began earlier than the issuance of the Omnibus Franchising Guidelines, the PBS already characterizes reforms mandated in the latter, particularly an environmentally sustainable bus fleet and drivers earning at fixed income instead of daily wages based on number of passengers. Moreover, because commuter bus transport services in the Philippines are mainly operated by the private sector, the PBS presents a unique case because it is local government-provided, financed, and managed.

The Pasig CTDMO established in 2017 by virtue of Ordinance No. 25, s. 2017, was borne out of the efforts of CENRO to introduce environment-friendly transportation such as Bike Sharing services, and the PBS. The office came from the Transport Planning Division (TDP) of the existing Traffic and Parking Management Office (TPMO). As the TDP was empowered to be the CTDMO under the direct supervision and control of the City Mayor, it is now tasked to undertake the transport planning and management of the city government. The CTDMO is an office mainly hinged on research and gathering of relevant data in order to make relevant plans and provide policy assistance to the City Council.

Several analytical, operational, and political policy capacities are laid out in the mandated functions of the CTDMO under Ordinance No. 25, s. 2017. However, from the passage of the said Ordinance in 2017 several of these responsibilities remain to be written in paper. In relation to analytical policy capacity, the agency still has to conduct transport surveys, hence the lack of a transport database system. It also has yet to establish an Intelligent Transport System (ITS) with the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office Central Command Center (DRRMO-C3) to monitor public transport and likewise source real-time data.

Its operational policy capacity is moreover constrained with limited coordination to other offices such as the TPMO, CENRO, DRRMO, City Planning and Development Office (CPDO), and Office of the Building Official (OBO) especially with data collection. It is also because of this that there have been challenges in implementing Ordinance No. 26, s. 2017 wherein the OBO issues building permits to developers even without passing through the CTDMO for the payment of Transportation Development Fees. Furthermore, comparing its mandated and existing organization structure, most of the personnel of the agency are involved in running the PBS – drivers, dispatchers, bus operations officer, bus boys; even though these positions are not specified in its Ordinance. Meanwhile, required personnel such as transport analysts, transport officers, and researchers have yet to be completely filled-up. Notably, despite its limitations, it has a proactive leadership allowing the agency to perform well in its role to formulate programs that encourage non-motorized mobility and the use of public transport through the PBS, Pasig River Ferry, and Bike Share Program.

In terms of political policy capacity, the CTDMO has partnerships with various non-government organizations especially in pursuing sustainable transport. It is also active in social media, promoting awareness of its transport programs and policies, and allowing the public to provide feedback. Whenever necessary, it sends representatives in the sessions of the City Council to articulate its plans, discuss transport issues, and provide technical support in policymaking.

Meanwhile, in providing the PBS, the CTDMO also has challenges on analytical, operational, and political capacities. It still has to accomplish an evaluation of the PBS required by the LTFRB before approving new routes and charging fares. Hence, the CTDMO is unable to implement Ordinance No. 27, s. 2017 that complements the PBS by allowing the city government to charge Environmentally Sustainable Transport (EST) Fees for public transport modes that it provides for operations maintenance. Since 2016 the PBS operates for free, with the city government shouldering its operation and maintenance costs. Furthermore, despite a bulk of the work and personnel of the CTDMO involved in the PBS, ridership and performance feedback surveys with passengers have not yet been conducted as mandated in the said Ordinance to maintain a high level of service.

3.2. Methodology

A design thinking workshop was undertaken in Pasig City with a challenge to create an information exchange platform for the PBS that could gather relevant transport data, allow the CTDMO to carry out its other responsibilities, and strengthen citizen engagement. It was comprised of different stakeholders, specifically, the Bus Operations Officer, Transport Planning Officer, driver, conductress, and regular passengers of the PBS invited by the CTDMO. It was facilitated by the three researchers who were from the academe along with two information technology (IT) specialists. Although usually held in days or weeks (Google, n.d.; Millan Citation2019), the workshop was limited to only one whole day, given the constraints in the schedules of the participants.

The activity consisted of six (6) stages based on the process and methods by Millan (Citation2019) and the Google Design Sprint (Citationn.d.). Each stage was guided by the facilitators who gave the instructions, set the time limits for each activity, encouraged participants to elaborate more on their outputs, and summarized and clarified ideas with the participants. The first stage, “Understand,” involved sub-activities aimed to build empathy among the stakeholders and take into consideration each other’s needs and concerns. This included “Journey Mapping” where participants had ten minutes to write down in metacards the decision points or activities they undergo on each stage or aspect of the PBS (in the stops, on board, upon alighting, during planning, monitoring, and others). The outputs where then summarized and categorized by the facilitators in preparation for the next sub-activity, “Experience Mapping.” This also involved ten minutes of the participants to recall experiences per stage or activity in the journey map, after which there was a structured timed discussion where each had three minutes to share their experiences. In the last sub-activity, participants reflected on identified needs and concerns, and positively reframed them into a “How Might We” or “Paano Kaya Natin” statements where they also had ten minutes to list and three minutes to explain their ideas. During the group sharing period, facilitators asked participants to expound on their answers and categorized similar outputs. Thereafter, participants had three votes each to select the HMW/PKN statements that they think should be prioritized.

Based on the outputs of the previous activities, in the second stage, “Define,” an open discussion was guided by the facilitators for participants to identify goals for the PBS, and the metrics to be used that would gauge the success of measures to attain these. The third stage, “Diverge,” involved “Crazy 8 s” or the sketching of eight (8) ideas that would answer the prioritized HMW/PKN statements. The facilitators ensured that the time limit of one minute per idea was followed and likewise facilitated the 5-minute discussion per participant. This was followed by participants voting on their top three desired sketches in the fourth stage, “Decide.” The fifth stage, “Prototype,” then involved an open discussion guided by facilitators where the highly voted ideas of the participants were incorporated through an information exchange platform laying out the actors of the PBS and the information flows per actor. Prototyping was then made by information technology (IT) specialists based on results of the previous stages to ensure the responsiveness of the platform to the participants’ identified needs and recommendations. Lastly, in the sixth stage, the prototype mobile application and CTDMO dashboard were presented by the IT specialists, and then critiqued by the participants. summarizes the Pasig Design Thinking Workshop process employed in this study.

In order to identify how co-design can contribute to policy capacity, thematic analysis was done on video recordings of the workshop. This is a systematic approach to analyzing qualitative data involving the identification of themes or meaningful patterns (Lapadat Citation2012) which is appropriate in distinguishing the different policy capacities referred to during the workshop discussions. This was done using MAXQDA, a qualitative data analysis software, and consisted of three processes: (1) open coding, (2) axial and selective coding, and (3) analyzing code frequencies. In open coding, data segments, which can be verbal or visual discussions from the workshop, were assigned with labels, referred to as codes, which in turn are words or phrases that summarize or capture the salient evocative attribute or essence of the data segments. This was followed by axial coding or grouping the codes based on their similar characteristics, and then by selective coding which further categorizes codes based on their main ideas which in this case were analytical, operational, or political capacities. Codes then were analyzed by their frequency or number of times they were recognized and in what category. (Saldana Citation2013; MAXQDA Citation2020; Millan Citation2019; Johnson and Christensen Citation2014). The thematic analysis was supported by a focused group discussion among workshop facilitators and the IT specialists to share their thoughts and experiences during the workshop. Positive aspects and issues encountered during the different stages of the workshop were identified which provided additional insights to the possibilities and constraints of co-design on policy capacity, and recommendations on how the process can be further improved.

Table 2. Pasig design thinking workshop process.

3.3. Findings

3.3.1. Policy capacity themes from the Pasig design thinking workshop

Results of the analysis were summarized into tables showing the different aspects and opportunities to enhance policy capacities and the corresponding codes in which these were manifested in the Pasig Design Thinking Workshop. First on analytical policy capacity, outputs by the participants across the different stages of the workshop showed the analytical functions and processes they undertake considering their different roles and interests in public transport. For commuters, this includes identifying available transport options, distance to stops, bus schedule, cost, occupancy, and safety; for drivers, conductresses, and dispatcher – knowing bus assignments, schedules, and intervals; for the CTDMO operations and planning officers – determining connected and appropriate stops, origin and destination of commuters, walkability of stops and roads, travel time, and passenger feedback. These can be later used to design an information exchange platform to collect, store, analyze, and retrieve the data needed by each stakeholder to support their analytical activities, especially that of the CTDMO in making evidence-based decision making.

The mapping activities further enabled the surfacing of several transport issues both in the PBS and the broader public transport system. Comparing the PBS to other public transport modes, the participants were particularly concerned with safety, timeliness, and affordability, expressing issues on the latter such as long queues, multiple transfers, and drivers improperly loading and unloading, violating pedestrian lanes, and not driving smoothly. Often raised by the participants is the heavy traffic in the city which is experienced whether taking the PBS or other public transport modes. Meanwhile, front liners from the CTDMO (drivers, dispatchers, conductresses) also aired concerns on violating passengers, in particular, those persistent at loading and unloading in improper stops, rude, littering, and not being able to arrive at the scheduled time at the stops, hence being left by the PBS. The raising of these concerns also reveals the priority factors and indicators that should be considered by the CTDMO in assessing and ensuring the quality of public transportation in the city. As the agency has yet to conduct public transport surveys, the outputs of the workshop can meanwhile serve as the basis on which public transport policies and interventions to prioritize. summarizes the analytical policy capacity aspects and the specific discussions during the workshop.

Table 3. Analytical policy capacity themes from the Pasig Design Thinking Workshop.

For operational policy capacity, emerging themes from the workshop include the assessment of current operational functions, capacities, and processes; human and technical resources; and operational capacity issues that affect policy implementation and monitoring (). These were mainly discussed at the organizational level of the CTDMO. Among those highlighted were the personnel management processes of the agency, raising concerns on unexpected changes in driver and conductress schedules brought about by absent or late employees. These demonstrates difficulties in the implementation of schedules and imposing sanctions to erring employees. Nonetheless, PBS drivers were generally considered by commuters to be more compliance to traffic rules and regulations compared to other public transport drivers. Participants also shared a situation wherein an erring PBS driver was reprimanded and imposed a penalty by a traffic enforcer which shows how implementation mechanisms and personnel are functioning.

Table 4. Operational policy capacity themes from the Pasig Design Thinking Workshop.

The technical capacities and resources of the agency were likewise discussed. One of these is the concern of manually recording trip data wherein the conductresses take note of the number of passengers boarding and alighting, and round trips taken which takes time to process and analyze. Monitoring of gas consumption is also limited to drivers taking photos of gas levels before and after their trips which may sometimes be unreliable due to cases of unexplainable gas consumption. The discussions across the various stages of the workshop highlighted the need for better monitoring mechanisms such as having real-time information, GPS, and online access to camera buses which can be considered by the CTDMO to improve their operational policy capacity.

Meanwhile, on political policy capacity, the design thinking workshop provided a space for stakeholder involvement as commuters joined with CTDMO front liners, and planning and operations officers in assessing the PBS. To attempt the leveling of hierarchies among participants and ensure that each one’s ideas and key concerns were raised, Phases 1 and 3 on Understand and Diverge had an allotted five to ten minutes for each participant to list their thoughts with the facilitators encouraging them to write as many as possible. There was then three to five minutes for each one to present and discuss their outputs with the group, thereby empowering them to speak up.

This also raises empathy which was especially evident as participants shared the analytical and operational policy capacity roles and concerns of one another. Commuters were able to express their daily struggles with public transportation such as overcrowding in jeepneys including the PBS, long queues, having to change from one mode of transport to another, rough driving. On the side of the CTDMO, a major issue faced by the drivers and conductresses are passengers who insist to be dropped at improper stops since this is what they are used to when riding public transport such as jeepneys and buses. CTDMO personnel clarified that they would like to shift from the culture of boarding and alighting anywhere along the street into a public transport that is systematic, predictable, and reliable. This was agreed upon by the commuter participants, however for the wider community, the CTDMO still has a long way to go. Notably, it was also mentioned that there are close relationships among regular passengers and the PBS drivers, conductresses, and dispatcher where they send SMS updates on bus schedule changes which the CTDMO can hinge on to gain political support for their initiatives and policies. summarizes discussions relating to political policy capacity during the workshop.

Table 5. Political policy capacity themes from the Pasig Design Thinking Workshop.

Features supporting the different policy capacities were proposed by participants in the Crazy 8 s and in the prototyped transport information exchange platform. For the analytical policy capacity of the CTDMO, this included identifying the origin and destination of commuters, determining connectivity of different transport modes, monitoring violations, and gaining passenger feedback for driving behavior, violations, and other public transport concerns. In terms of operational policy capacity, participants identified the actors of the PBS and the information flows per actor, allowing the CTDMO to assess their organizational condition, especially the interaction among their personnel, the commuters, and other departments in the local government. It also included having features on prompt relaying of bus schedule and changes to commuters, accident reporting, reliable monitoring of gas consumption, and real-time monitoring of location, trip duration, and roundtrips completed, among others. Aside from gaining passenger feedback, political policy capacity included being able to relay policies to the public and coordinate better with the Pasig City Central Command Center for emergency response and access to road surveillance cameras.

3.3.2. Limitations and learnings during the workshop

The conduct of the Pasig Design Thinking workshop was likewise faced by limitations and challenges which can be learned upon to guide future co-design activities. These included the subjective selection of participants, time constraints, and the processes in which some stages were conducted. First is that invitation of the participants was coursed through the CTDMO as they have contact with their personnel and the commuters. This resulted to having commuter-participants in which the front-line personnel are in close contact with. Representative commuters were also not as diverse as intended to include vulnerable sectors such as senior citizens, persons with disabilities, or parents often traveling with younger children. Although participant-commuters gave both negative and positive feedbacks on the PBS, there would have been more varied insights if other kinds of commuters were included.

Second, while co-design workshops can span for days (Google, n.d.; Millan Citation2019), the Pasig Design Thinking Workshop was held in only one day, considering the limited time of participants. A longer duration of the activity would have provided a more thorough discussion of each item across the different stages. Being external to the CTDMO, more time was also taken by facilitators to understand their internal processes and issues. As can be seen in , the facilitators had the highest frequency of speaking during the discussions as they inquired and sought to expand the topics raised by the participants. While this ensured that their understanding was in line with that of the participants, it also competed with the time for participants to speak up.

Table 6. Frequency of involvement of participants in Phases 1 to 3 of the Design Thinking Workshop.

Third, there were limitations on how the co-design process was structured by the facilitators. As can be observed in , majority of the involvement of the participants are during the activities in Phases 1 and 3 on Understand and Diverge which allotted time for participants to write and share their thoughts. Phase 2 on Define, in contrast, was an open discussion and not much interaction was recorded among the participants. Although not recorded in video, this was also observed by facilitators in Phase 5 on Prototyping which had more inputs of the CTDMO personnel. The facilitators note that there would have been better participation if a process similar to Phases 1 and 3 were done. Moreover, in Phases 1 and 4, while consensus was sought, specifically at the end of mapping and ideation activities where participants had to vote on which issues and solutions to prioritize, there might have been peer influences as they went at the same time to mark their votes. A better option would have been to place votes secretly.

There was also confusion in Phase 2 as instead of defining metrics and goals for the HMWs, participants mostly wrote down solutions. To adjust on these outputs and make the process more plausible, facilitators instead considered the voted HMWs as goals for the succeeding stage. Finally, for the Validate stage, although a prototype application and dashboard for the information exchange platform was created by the IT developers, this was only projected to the participants. Facilitators recommend that the protype be tested one by one to provide a better experience for the participants and ensure more comprehensive feedback.

3.4. Operationalizing the results of the co-design workshop

Results of the discussions in the design thinking workshop, especially the information exchange platform that was prototyped served to guide the development of a platform consisting of a dashboard placed in the CTDMO and a mobile application for the public. With the identified need in the workshop to gather information on transport demand and the origin and destination of passengers to make responsive public transport routes, and monitor the PBS to allow the CTDMO and public to know the real-time location, and estimated times of arrival of the buses, Internet of Things (IoT) devices were deployed in the PBS buses, consisting of GPS and cameras, and having the information transmitted to cloud-based data storage accessible via the co-designed mobile application and dashboard.

From these, various data were able to be gathered, slowly building up the information database of the CTDMO to strengthen their analytical policy capacity. These include vehicle speed and location which revealed and recorded areas with different levels of traffic at given times and days, helping the CTDMO to identify problematic areas and formulate interventions. The platform has also been valuable in the operational policy capacity of the agency, especially the individual capacity of the Bus Operations Officer, in monitoring the operations of the PBS, and thereby detecting drivers that do not follow the designated route and cut trips. Meanwhile, development of the mobile application which is currently on-going is designed to allow the public to access data on the PBS, provide feedback, and report issues, which would then contribute essential data for analysis, and promote political policy capacity at the system level.

4. Conclusions and recommendations

Findings from thematic analysis of the discussions from different stages of the workshop show the opportunities in which co-design can support the analytical, operational, and policy capacities of a local government agency. It provided a venue for identifying and assessing the different functions, processes, and challenges falling under each capacity and proposing recommendations coming from the participants.

For analytical policy capacity, several transport issues were raised and shared by stakeholders who experience them, thereby giving a clear and comprehensive view of problems. These outputs of the discussions along with the technical components of the information exchange platform designed by participants would guide the CTDMO in making evidence-based decision-making. Meanwhile, discussions on operational policy capacity revolved around the human and technical resources of the CTDMO and how these can be improved to provide a reliable and responsive service to the public. Being a participatory activity, the workshop also reinforced political policy capacity by bringing together different stakeholders, allowing representatives from commuters, and CTDMO management and front-line personnel to share their different experiences and foster empathy.

Recommendations borne from the limitations of the concluded workshop include selecting diverse public stakeholders, especially for commuters. Invitation of participants for co-design workshops, especially relating to governance and policy, are better to be publicly announced with relevant criteria and processes for selection. There should also be careful consideration on the duration of the workshop, balancing having deeper discussion with the time allowable by participants. Having activities that require each participant to provide inputs should also be sustained across the different stages, in contrast to having open discussions such as in the case of Phases 2, 5, and 6 of the Pasig Design Thinking Workshop on defining metrics and goals, and in designing and validating the protype. Addressing these limitations, co-design can be instrumental in assessing and enhancing policy capacities of local governments especially in public transport policymaking, implementation, and monitoring.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the administrative and logistical support of the Pasig CTDMO in the conduct of the design thinking workshop.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alimondo, L. 2019. PUV route plans in LGUs pressed. Retrieved from Sunstar News: https://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/1822744/Baguio/Local-News/PUV-route-plans-in-LGUs-pressed

- Baquero, E., and G. Magdadaro. 2019. Lapu-Lapu Mayor rejects 100 modern e-jeepneys. Retrieved from Sunstar News: https://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/1814799/Cebu/Local-News/Lapu-Lapu-Mayor-rejects-100-modern-e-jeepneys

- Barter, P., J. Kenworthy, and F. Laube. 2003. “Lessons from Asia on Sustainable Urban Transport.” In Making Urban Transport Sustainable, edited by Low, N., & Gleeson B., 252–270. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Blomkamp, E. 2018. “The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 77 (4): 729–743. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12310.

- Brown, T. 2008. Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, pp. 84–92.

- Ciasullo, M. V., R. Palumbo, and O. Troisi. 2017. “Reading Public Service Co-Production through the Lenses of Requisite Variety.” International Journal of Business and Management 12 (2): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v12n2p1.

- Department of Interior and Local Government & Department of Transportation. 2017. Joint Memorandum Circular No. 001, s. 2017: Guidelines on the Preparation and Issuance of Local ordinances, Order, Rules and Regulations Concerning the Local Public Transport Route Plan (LPTRP). Mabalacat: DILG & DoTr.

- Department of Transportation. 2017. Department Order no. 2017-011 Department Order no. 2017-011: Omnibus Guidelines on the Planning and Identification of Public Road Transportation Services and Franchise Issuance. Mabalacat: Department of Transportation.

- Deserti, A., F. Rizzo, and M. Smallman. 2020. “Experimenting with Co-Design in STI Policy Making.” Policy Design and Practice 3 (2): 135–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1764692.

- Design Policy Lab. 2018. The Design Policy Lab Group. Retrieved June 24, 2020, from Design Policy Lab: http://www.designpolicy.eu/about/

- Di Francesco, M. 2000. “An Evaluation Crucible: Evaluating Policy Advice in Australian Central Agencies.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 59 (1): 36–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.00138.

- Domingo, S., R. Briones. and D. Gundaya. 2015. Diagnostic Report on the Bus Transport Sector. Makati: Philippine Institute for Development Studies.

- Evans, M., and N. Terrey. 2016. “Co-Design with Ctizens and Stakeholders.” In Evidence-Based Policy Making in the Social Sciences, Stoker, G., & Evans M., 243–262. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. Retrieved from University of Canberra Institute for Governance and Policy & Policy Analysis.

- GMA News. 2013. Building a design democracy: How you can help design a better Philippines. Retrieved from https://www.gmanetwork.com/: https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/cbb/content/327183/building-a-design-democracy-how-you-can-help-design-a-better-philippines/story/

- Google. n.d. Design Sprint Methodology. Retrieved March 3, 2020, from Design Sprint Kit: https://designsprintkit.withgoogle.com/methodology/overview

- Hartley, K., and J. Zhang. 2018. “Measuring Policy Capacity through Government Indices.” In Policy Capacity and Governance: Assessing Governmental Competencies and Capabilities in Theory and Practice, edited by Wu, X., Ramesh, M., & Howlett M., 67–97. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Howlett, M., and A. M. Wellstead. 2011. “Policy Analysts in the Bureaucracy Revisited: The Nature of Professional Policy Work in Contemporary Government.” Politics & Policy 49 (4): 613–633.

- Hsu, A. 2018. “Measuring Policy Analytical Capacity for the Environment: A Case for Engaging New Actors.” In Policy Capacity and Governance: Assessing Governmental Competencies and Capabilities in Theory and Practice, Wu, X., & Howlett M., 99–121. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hudson, B., D. Hunter, and S. Peckham. 2019. “Policy Failure and the Policy-Implemetation Gap: Can Policy Support Programs Help?” Policy Design and Practice 2 (1): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2018.1540378.

- Ieda, H. (Ed.). 2010. Sustainable Urban Transport in an Asian Context. Tokyo: Center for Sustainable Urban Regeneration, The University of Tokyo.

- Johnson, R. B., and L. Christensen. 2014. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Kimbell, L. 2015. Applying Design Approaches to Policy Making: Discovering Policy Lab. Brighton: University of Brighton.

- Kimbell, L., and J. Bailey. 2017. “Prototyping and the New Spirit of Policy-Making.” International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 13 (3):214–226.

- Koo, Y., and H. Ahn. 2018. “Analysis on the Utilization of Co-Design Practices for Developing Consumer-Oriented Public Service and Policy Focusing on the Comparison with Western Countries and South Korea.” Politecnico di Milano, 1 (1): 282–297.

- Lapadat, J. C. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research, edited by Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E., 926–927. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Lewis, J., M. McGann, and E. Blomkamp. 2020. “When Design Meets Power: Design Thinking, Public Sector Innovation and the Politics of Policymaking.” Policy & Politics 48 (1): 111–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/030557319X15579230420081.

- Mateo-Babiano, I. 2016. “Indigeneity of Transport in Developing Cities.” International Planning Studies 21 (2): 132–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2015.1114453.

- MAXQDA. 2020. MAXQDA 2020 Manual. Retrieved from MAXQDA: The Art of Data Analysis: https://www.maxqda.com/help-mx20/welcome.

- Millan, S. B. 2019. Design Thinking and Collaborative Governance for Public Service Innovation: An Application in Civic Tecnology. Quezon City: National College of Public Administration and Governance.

- Mintrom, M., and J. Luetjens. 2016. “Design Thinking in Policymaking Processes: Opportunities and Challenges.” Australian Journal of Public Administration, 75 (3): 1–12.

- Mitchell, V., T. Ross, A. May, R. Sims, and C. Parker. 2016. “Empirical Investigation of the Impact of Using co-Design Methods When Generating Proposals for Sustainable Travel Solutions.” CoDesign 12 (4): 205–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1091894.

- Pasig Government. 2015. Pasig City Comprehensive Land and Water Use Plan 2015-2023. Pasig: Pasig Government.

- Pettersson, F., S. Westerdahl, and J. Hansson. 2018. “Learning through Collaboration in the Swedish Public Transport Sector? Co-Production through Guidelines and Living Labs.” Research in Transportation Economics 69: 394–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2018.07.010.

- Philippine Congress. 1991. Republic Act No. 7160: An Act Providing for a Local Government Code of 1991. Quezon City: Philippine Congress.

- Polidano, C. 2000. “Measuring Public Sector Capacity.” World Development 28 (5): 805–822. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00158-8.

- PSA. 2016. 2016 Philippine Statistical Yearbook. Quezon City: Philippine Statistics Authority.

- Rahman, N. A., and Y. A. Abdullah. 2016. Theorizing the Concept of Urban Public Transportation Institutional Framework in Malaysia (Vol. 66). MATEC Web of Conferences. doi:https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/20166600043.

- Rappler. 2016. Innovating business with design thinking. Retrieved from Rappler: https://www.rappler.com/

- Romero, S., D. Guillen, L. Cordova. and G. Gatarin. 2014. Land-Based Transport Governance in the Philippines: Focus on Metro Manila. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University.

- Saldana, J. 2013. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Reserchers (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications, Ltd.

- Sohail, M., D. Maunder, and S. Cavill. 2006. “Effective Regulation for Sustainable Public Transport in Developing Countries.” Transport Policy 13 (3): 177–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2005.11.004.

- Sridhar, K. S., R. Gadgil. and C. Dhingra. 2019. Paving the Way for Better Governance in Urban Transport: The Transport Governance Initiative. Singapore: Springer.

- Stahl, M. 1981. “Toward a Policy-Making Paradigm of Public Administration.” The American Review of Public Administration 15 (1): 7–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/027507408101500103.

- Tandemic 2018. Design Thinking in the Philippines: Four great initiatives. Retrieved from https://medium.com/: https://medium.com/@tandemic/design-thinking-in-the-philippines-four-great-initiatives-20cfc3461a7f

- Thissen, W. A., and P. G. Twaalfhoven. 2001. “Towards a Conceptual Structure for Evaluating Policy Analytic Activities.” European Journal of Operational Research 129 (3): 627–649. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(99)00470-1.

- TTPI & UP PLANADES. 2011. Pasig City Central Business District Land Use and Transport Study, Comprehensive Transportation and Traffic Plan. Pasig City: Transport and Traffic Planners, Inc. & UP Planning and Development Research Foundation, Inc.

- UK Design Council. 2020. UK Cabinet Office Launches New Policy Design Lab. Retrieved June 24, 2020, from UK Design Council: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/uk-cabinet-office-launches-new-policy-design-lab

- United Nations 2016. The World's Cities in 2016. Retrieved from United Nations: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2016_data_booklet.pdf

- Wijaya, S. E., and M. Imran. 2019. Moving the Masses: Bus-Rapid Transmit (BRT) Policies in Low Income Asian Cities. Singapore: Springer.

- Wu, X., M. Ramesh, and M. Howlett. 2015. “Policy Capacity: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Policy Competences and Capabilities.” Policy and Society 34 (3-4): 165–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001.

- Wu, X., M. Ramesh. and M. Howlett. 2018. “Policy Capacity: Conceptual Framework and Essential Components.” In Policy Capacity and Governance: Assessing Governmental Competencies and Capabilities in Theory and Practice, edited by X. Wu, M. Ramesh, & M. Howlett, 1–27. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.