Abstract

2020 threw into stark relief the fact that the impact of policy interventions in Indigenous affairs over the last decade and a half has been scandalously minimal. Explanations for this focus on technocratic themes such as implementation, leadership failure or lack of resources. The problem, however, is not a technical one, there is something wrong with the policy design related to Indigenous Australians. Policy design involves questions of not just what we know, but how we know, and how this knowledge is mobilized in and through policymaking. Policy impact Indigenous contexts is low precisely because contemporary policymaking excludes the knowledge and insights of Indigenous people. This makes important knowledge inaccessible to state and non-state actors, and fatally weakens policymaking. This paper appropriates the concept of metis to interrogate the root of policy failure in processes of epistemological exclusion and suppression that underpin modern statecraft is of critical importance to improving the impact of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise. The chief contention is that improved impact in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise hinges on centering Aboriginal metis at the epistemic, discursive, and conceptual core of the enterprise.

1. Introduction

Looking back, not many of us mourned the passing of 2020 – Indigenous people least of all. It was a year characterized by the cultural impact of the bushfires over the 2019–2020 Summer, the erosion of community generated by the global Covid-19 pandemic, and the continuing scourge of black deaths at the hands of law enforcement, given fresh emphasis by the Black Lives Matter protests. Quite apart from these, 2020 will go down in history as the year in which the persistent, unreconstructed, at times combative white superiority underlying our national identity, the hollowness of many non-Indigenous alliances, and the failure of the last decade and a half of Indigenous affairs policy all came home to roost. 2020 threw into stark relief the fact that the impact of policy interventions in Indigenous affairs over the last decade and a half has been scandalously minimal. Traditional explanations for this tend to orbit a suite of technocratic themes such as implementation, leadership failure or lack of resources. Eleven years into the Closing the Gap era, the idea that we have the policy right, but the implementation wrong (Commonwealth Citation2009) seems to be breathtakingly implausible to say the least. This assessment was wrong then, and it is wrong now. Our problem is not a technical one, there is something wrong with the design of policy in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise. This paper seeks to address this lack drawing on James Scott’s (Scott Citation1996, Citation1998) use of the Classical Greek concept of metis, to probe the epistemological underpinnings of the contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise.

2. Positioning this analysis

Before proceeding however, it will be useful to set out the standpoint from which this analysis proceeds. I come to this topic from three separate but interrelated perspectives. First as an Aboriginal person, a member of the Dunghutti and Biripi nations of the mid-north coast of New South Wales in Australia. As a result my analysis is informed by an Aboriginal perspective that recognizes policymaking as a profoundly cultural endeavor and is concerned with understanding the holistic nature of social interaction, and how this plays out in policymaking and other aspects of statecraft. As an Aboriginal person I give precedence to the social as the basis of knowledge and analysis that embraces the ambiguity, liminality, relationality and discontinuity found in the “spaces in between” objects as the objects themselves (O'Brien Citation2018). Second as a senior bureaucrat with a long career in Indigenous public policy at state and national levels ranging across the health and education policy domains. This means that while theoretically informed this research, and indeed this paper has an unashamedly applied focus. I am interested in us doing better in this area of public policy. The target audience is policymakers, and my objective is to stimulate deeper engagement with the knowledge and perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the work of policymaking and a concern to explore and embrace the art of policymaking at the “cultural interface” (Nakata Citation2007). Third as a former teacher and doctoral scholar with an interest in transformative understandings of policymaking in respect of Indigenous people. I am interested in knowledge that has a transformational and emancipatory impact. This article is part of a corpus of work including my doctoral research orientated around this aspiration asking how a better understanding of Aboriginal culture can serve as a vector for transformation of the policymaking enterprise thereby delivering better outcomes for Aboriginal people.

3. A question of design

There is an unbreakable link between policy impact and policy design (Howlett and Mukherjee Citation2018; Schneider and Ingram Citation1997). Poor design produces poor policies, which in turn deliver poor outcomes. Despite this, the issue of policy design has been severely neglected in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise in favor of more the traditional technocratic themes alluded to above (Commonwealth Citation2009, Pusey Citation1991).

The idea of “policy design” reflects the seminal work of Schneider and Ingram (Citation1997) who argued that policies reflect deeper and more fundamental designs and that policy analysis needs to go much further than simply operational and practical matters but also take into account symbolic and interpretive elements. For them, policy design is multifaceted and encompasses more than either policy formulation or selection of policy instruments. Policy design refers to the “blueprints, architecture, discourses, and aesthetics…” (Schneider and Ingram Citation1997, 2) that structure and direct policymaking. It directs our attention to the ideas, structures, networks and institutional venues through which policymaking takes place.Footnote1 Importantly, analysis of policy design points to the discourses that frame policymaker understanding of policy problems (Bacchi, Citation2009), policy goals, target populations, and the kind of policy interventions required.

In relation to policy failure in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise the real power of a policy design perspective is that it generates critical questions about the blueprints and mental models operating in this space. It challenges us to interrogate the policy goals that have been set, and to ask searching questions about what we know, how we know it, and why. It drives us to toward a less atomistic analysis that comprehends policymaking as an integrated, systemic, and profoundly paradigmatic endeavor and ultimately drives us to ask questions about the epistemological ground from which we make policy in respect of Aboriginal people.

4. Knowledge and policy design

‘Policy design, much like policymaking generally, is fundamentally a knowledge-based endeavor involving questions of not just what we know, but also how we know what we know, and how this knowledge is mobilized in and through policymaking. According to Schneider and Ingram, “policy designs are produced through a dynamic historical process involving the social constructions of knowledge and identities of target populations power relationships, and institutions” (1997, 5). The critical point here is that the knowledge involved in policymaking is a socially constructed phenomenonFootnote2 emerging from interaction within social networks (Charon Citation1995; Hall Citation1972; Oliver Citation2012; Ritchie Citation2021; Kuhn and Hacking Citation2012). These constructions both enable and limit human insight, shaping the knowledge we bring to policymaking (Schneider and Ingram, Citation1993) and which, through radically recursive processes, become hard-wired into policy designs themselves as a priori epistemic commitments that present as both neutral and universal. It is here, in the enabling/limiting action of knowledge, that the foundations of low policy impact in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise can be found. As Schneider and Ingram put it:

Possibilities for fundamental change are thwarted by near-hegemonic constructions of reality that discourage human agency and by the capacity of political institutions to respond to, co-opt, or thwart oppositional movements without actually making fundamental structural changes. (1997, 9)

If policy failure stems from policy design, and policy design is inevitably about the knowledge we deploy, it is imperative that we come to grips with the question of knowledge and its role in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise. James Scott’s magisterial Seeing Like a State (Citation1998) provides a compelling analytical framework for this, particularly his use of the ancient Greek concept of metis to highlight a category of knowledge and practice excluded in modernist statecraft, including policymaking, the exclusion of which he argues guarantees the failure of state interventions.

5. James Scott and the problem of knowledge

The first thing to appreciate about the modern state is that most of its officials are, of necessity, usually at least one step— and often several steps—removed from direct contact with citizens. They observe and assess the life of their society by a series of simplifications and shorthand fictions that are always some distance from the full reality these abstractions are meant to capture. (Scott Citation1996, 55)

The role of knowledge in state interventions occupies center-stage in Scott’s analysis of policy failure. He posits the source of this failure in the state exclusion of local/particular forms of knowledge and practice, in favor of the high modernist epistemology that emerged in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. At the core of his critique of modernist statecraft is a radical cultural dissonance (Ritchie Citation2021) manifest in a contest between these different ways of knowing and doing – “modernist” knowledge, universal and imperious; and the local and particular knowledges that orientate and organize social networks and the lives of the members of those networks. This epistemic imposition/suppression dynamic is the primary phenomenon that Scott problematizes in his analysis of statecraft. This matters in policymaking because what, and more importantly how, policymakers think shapes what they do in policy terms (Campbell Citation2002; Finlayson Citation2006), and ultimately this underwrites the success, or failure of state schemes.

The dominant knowledge orientation of modernist policymaking springs from the European Enlightenment, with its putative universality and cultural neutrality. The problem is of course that the Enlightenment was a highly racialised movement born out of a particular socio-cultural context (Schrom Citation2016; Heikes Citation2015; Eze Citation1997). Emerging, as it did from the “universe of discourse” (Boole Citation1951) of 18th century Europe, where racial and gender chauvinisms sat at the core of conceptions of civilization (Heikes Citation2015), the deeply racialised nature of this episteme should be unsurprising. Because these fundamental chauvinisms are in the DNA of modernist policymaking via the hegemonic influence of Enlightenment thinking, especially in settler-colonial states, understanding the nature of this epistemology, and the processes of epistemological exclusion and suppression that underpin modern statecraft, is of critical importance to improving the impact of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise.

Modern statecraft, including policymaking, demands legibilityFootnote3, so its epistemic orientation is toward reducing complexity and creating certainty. Consequently the planned or designed social orders that are produced are inevitably reductionist (Scott Citation1998). In this quest for legibility and control, policymakers deploy epistemic maps of the manageable order which they seek to bring about through policymaking. These maps constitute a view from above: distilled, abstracted, and intentionally constructed so as to “summarise precisely those aspects of a complex social world that are of immediate interest to the mapmaker and to ignore the rest” (Scott Citation1998, 87).

To some extent this is necessary, but Scott’s point is that these foundational schemas never fully capture the complex realities of life “on the ground”. Instead, they frame policymaking by focusing attention only on those things that interest state actors. As with any frame, some things are brought into sharp focus, others recede into the background, while still others are excluded from view altogether. Applied to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise this imposition/exclusion dynamic offers novel insights into understanding and remedying the chronic failure that characterizes this area of public policy. The key is understanding the kind of knowledge that is excluded and the impact of this exclusion in policymaking terms. Scott uses the concept of metis to identify displaced knowledge and practice. Understanding the nature of metic knowledge and bringing it to bear on the design of policy in the Indigenous affairs space is critical to the transformation of Indigenous policymaking in Australia.

6. Metis - the missing piece of the puzzle

Defined variously as “practical knowledge” (Hickman Citation2016; Brown Citation1952; Metta Citation2015) or “intelligent ability” (Detienne and Vernant Citation1978) metis refers to the “fund of valuable knowledge embedded in local practices” (Scott Citation1998, 6) that supports functioning social orders. It is knowledge embedded in local experience and belonging. According to Scott, it is precisely this form of knowledge that the state excludes in its efforts to transform social orders and improve human lives. This exclusion is particularly acute in settler-colonial states, such as Australia, where the elimination of the ‘native’ is the central imperative (Wolfe Citation2006; Scott Citation1998). There is a central epistemological element to this elimination in the setting aside of the metic knowledge located in the social networks that constitute Indigenous communities. It is this imperative of elimination and the imposition of an imported modernist rationality that underwrites the negligible impact of large-scale state schemes such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise. As Scott puts it:

This perspective on social order is less an analytical insight than a sociological truism. It does offer, however, a valuable point of departure for understanding why authoritarian high-modernist schemes are potentially so destructive. What they ignore – and often suppress – are precisely the practical skills that underwrite any complex activity. (Scott Citation1998, 311)

At this point it is important to stress that metis does not refer to a particular or defined or universalized canon of knowledge. In fact, it is the opposite. Metis is as much a way of knowing, and a kind of knowing, than a codified body of knowledge to be mastered. While metis has content, this is as varied and as diverse as the peoples and the contexts where it is found, and its manifestations are multi-vocal and diverse.

The argument advanced in this paper is that policy-making in relation to Indigenous people must embrace Indigenous peoples’ metic knowledge rather than continuing the settler colonial practice of elimination, exclusion, and suppression of the Indigenous in all its dimensions (Wolfe Citation2006). The primary concern therefore is to direct policymakers to this form of knowledge as fundamental to effective policymaking. It is to point to the fact that Indigenous knowledges are there, not in the form of an authorized or codified canon which knowledge in the modernist sense purports to be, but nonetheless available as something that policymaking practice simply must engage with. In addition this paper advocates a radical transformation of Australian policy-making based on the deep knowledge, “cunning intelligence” (Detienne and Vernant Citation1978), and practical wisdom of all the communities and the people (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) concerning whom, and in whose interests, policy-making is carried out (Askew et al.).

7. The contours of practical knowledge – understanding metis

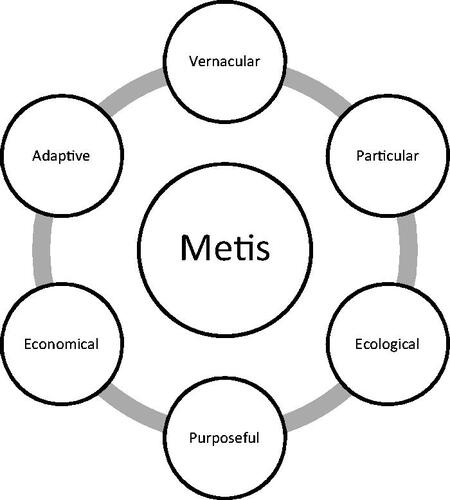

If the exclusion of metic knowledge from Indigenous policymaking underwrites chronic low impact and policy failure, and the transformation of policymaking practice requires its inclusion, then it is imperative that we find ways to bring this knowledge into the core of our professional practice. To do this we must understand the qualities that distinguish this kind of knowledge (Semali and Kincheloe Citation1999). We must understand what Scott calls the “contours of practical knowledge” if we are to create a larger epistemic frame within which the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise is prosecuted. Scott identified six distinguishing qualities of metis. Figure summarizes these ().

Figure 1. Qualities of Metis (Scott Citation1998).

7.1. Vernacular

Metis is knowledge that is distinctly ordinary, everyday, and unashamedly of the peopleFootnote4. It exists within networks of social relationships (Hickman Citation2016) and is “embedded in local experience” (Scott Citation1998, 311) in contrast to the Enlightenment idea of knowledge emerging as something which exists “out there” and whose discovery and possession is the province of the expert and the elite. Metis is democratized knowledge that belongs to the people in general and is quintessentially organic. It is knowledge that arises within particular networks of social relationships, as opposed to knowledge that is imposed from the outside (Roediger Citation2007). This is genuinely insider knowledge and as Hickman (Citation2016, 3) points out “one must actively be there to know and understand”. It is radically localFootnote5 with no pretension to existence or applicability outside of the experience and relationality of local communities.

7.2. Particular

Because metis does not exist as an independent phenomenon separate to or outside of sociality it is knowledge acquired in belonging.Footnote6 This kind of knowledge is only accessible through membership of, and participation in, the networks of relationships that constitute the community. Consequently, it is inevitably particular and not general. It is the difference between generic knowledge, for example, about forests as a general category and specific knowledge - “this forest” in particular (Scott Citation1998, 318 emphasis in original). Because it exists in socially, spatially, and temporally unique settings metis is a knowledge that is radically and irretrievably particular (Semali and Kincheloe Citation1999).

7.3. Ecological

While metis is a knowledge that belongs to particular peoples, it equally belongs particular places as well. This means that as a form of knowledge, metis is profoundly contextual and ecological: “keyed to conform to the features of the local ecosystem” (Scott Citation1998, 312). In this sense metis is a grounded knowledge and practice (Scott Citation1998, 328). Extending this thought, metis is genuinely empirical knowledge in that it derives from “an exceptionally close and astute observation of the environment” (1998, 320, 324). A word of caution is required here however. Modernist state epistemology privileges large amounts, often quite literally quantities, of dataFootnote7 to describe the context or the situation and in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise, our enthrallment to quantification seems boundless. We are very good at collecting data (Walter and Andersen Citation2013; Walter Citation2018; Hacking Citation1990). Metis however is more than merely knowledge about, it is knowledge that is from context, and it is knowledge in context. In contrast to modernist knowledge which exists independent of time or space, the origin of metis is in the radical intersection of both, with operating parameters, and its interests that are entirely parochial. Inevitably, this produces a principal concern with practical concerns of living life.

7.4. Purposeful

The ground of metis is the lived experience of particular people in particular contexts (Hickman Citation2016). Consequently its focus is on practical solutions to everyday challenges: when to plant crops for greatest effect (Scott Citation1998, 311); how to confront and defeat enemies (Scott Citation1998, 313); how to safely bring a ship to port (Scott Citation1998, 316–317); how to respond to emergencies and disasters (Scott Citation1998, 314); or indeed, the range of far more prosaic activities that constitute everyday life (Scott Citation1998, 313). As Scott puts it the “the litmus test for metis is practical success” (Citation1998, 323). The fundamental question here is whether knowledge and/or practice achieves a desired result or not. Such a pragmatic focus inevitably gives rise to important questions about values and assessments of what really matters for people, and how policymaking should respond to this knowledge. In the experience of many Indigenous people, however, these questions are not ones that policymakers in their efforts to makes things better readily embrace.Footnote8

7.5. Adaptive

The link to place and context is important to understanding the adaptive nature of metis. Given it is radically contextual, keyed to the features of its locale, and because contexts change, the knowledge that the context produces will change and adapt. It is here that the adaptive and responsive nature of metis comes to the fore. Because it is not readily susceptible to the kind of codification or domestication prized by homogenizing states, metis operates as practical wisdom or skill, often expressed as “rules of thumb” that can be applied as the situation required (Scott Citation1998). This fundamentally adaptability and responsiveness is emphasized by the range ancient applications of the concept that link it to apt responses to “a constantly changing natural and human environment” (Scott Citation1998, 313). Because metis is problem-solving, knowledge tied to context and every situation is different, metis is inevitably responsive and adaptable. It is also necessarily attentive to ready communication of essential knowledge in often precarious or volatile situations.

7.5. Economical

Because the core concern of metis is responding to shifting contexts and delivering practical outcomes rather than contributing to the “general conventions of scientific discourse”(Scott Citation1998, 323) it inclines toward parsimony rather than elaboration and discursiveness (Scott Citation1998). Metis says what it needs to say to achieve its purpose and no more. Scott’s comparison of Native American insights about the best time to plant crops with Quetelet’s elaborate mathematical calculations to determine the time when lilacs would bloom in Belgium illustrates this characteristic ().

Table 1. Metis and "Scientific" Knowledge compared - from Scott (Citation1998).

What is clear from this comparison is that metis is “as economical and accurate as it needs to be, no more and no less, for addressing the problem at hand”(Scott Citation1998, 313). It is an applied knowledge, driven by the imperative of necessity, and focused on achieving a result rather than knowledge for its own sake.

8. Metis as indigenous knowledge

That Australian First Nations scholars have a deep engagement with questions relating to the kind of epistemicide, to use Santos’s (DE Sousa Santos Citation1998) evocative term, that is at the heart of the settler-colonial project is undeniable and their analyses map closely to the contours of metis presented above.Footnote9 For example, Goenpul scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson (Citation2017) argues that Indigenous knowledges are grounded in the importance of relationality, demonstrating how the social-embeddedness of knowledge is not just true of metis generally, but also of Indigenous cultures specifically. She posits that “there are rules that are enmeshed in social relations and bloodline to country, determined by ancestors and creator beings that guide who can be a knower and of what knowledges” (2017, 72). Torres Strait Islander academic Martin Nakata’s (Citation2007) seminal work on anthropology and Indigenous knowledges, describes the contested epistemological and institutional space inhabited by Indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. Reflecting on the experience of Indigenous people within colonial systems, specifically universities,Footnote10 he points out that Indigenous “epistemological [bases] of knowledge construction” operate not only to shape how we understand ourselves as Indigenous people, even within the context of colonial institutional depiction, but also how we respond critically to that characterization and the social and epistemological positioning that it attempts. In this way Indigenous agency and knowledge become vectors for resistance, critique, and transformation “in the interests of better practice” (Nakata Citation2007, 222).

In the field of education, Rigney (Citation2020) shows the importance of allowing Indigenous children access to their local and prior knowledges. He argues that westernized and colonialized education systems are systematically failing Indigenous students by applying broad stroke/mono-lingual/mono-cultural understandings of teaching, education and students. This replicates the very epistemic imperialism that Scott argues undermines state action, in this case education. However, instead of denying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students access to these metic knowledge systems, culturally responsive pedagogies – that is, pedagogies which recognize Indigenous knowledges in their variety of forms – help to further inform and produce greater outcomes for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander students. Munanjahli and South Sea Islander academic Chelsea Bond and her collaborators underscore the very real harm that results from the failure to systematically examine the knowledge and experience of Indigenous people in relation to access to and delivery of health care (Jennings, Bond, and Hill Citation2018), health promotion (Askew et al. Citation2020), and the broader policy narratives in Indigenous affairs (Bond and Singh Citation2020).

9. Conclusion

The central thrust of this article is that modernist state interventions, such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise, fail because they pay no attention to the knowledge, perspectives, and practices embodied in and created by Indigenous people. It is worth reiterating here that the concept of metis describes a dialect of knowledge and practice, not a defined and reified body of epistemic content. Metis is as diverse as the contexts in which humans live and operate. The proposition being advanced through deploying this concept is that there is a fundamental flaw in modernist statecraft, including policymaking. This flaw is the suppression of metic knowledge – particular ways of knowing and the knowledge that these generate. The key to its relevance in an Australian context is to recognize the epistemic tyranny inherent in the modernist Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise and to center the vital knowledges it excludes.

The late Patrick Wolfe defined the practice of settler colonialism as “a structure not an event” (Wolfe Citation1999, Citation2006). In other words, it is institutionalized. This paper has argued that this eliminative logic continues in the setting aside of metis – Indigenous knowledge – in Australian policymaking. Such suppression makes important insights and knowledge inaccessible to state and non-state actors, and in doing so fatally weakens policymaking and perpetuates the persistent colonial relationship between the Australian state and First Nations peoples (Scott Citation1985, Citation1990, Citation1998). It follows that improved impact in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise hinges on bringing the metic knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to bear in policymaking. The approach advanced here offers more accurate and helpful insights into chronic policy failure in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait policy enterprise. In addition, it provides pointers to a solution to the current malaise in Indigenous policymaking in centering Aboriginal metis at the epistemic, discursive, and conceptual core of the enterprise. This is the very essence of decolonialsing the policy enterprise (Santos Citation2007). The 2020 agreement between Australian governments and a coalition of Indigenous peak bodies representing the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services sector is a necessary first step.Footnote11 I say “first step” because placing indigenous people at the table in the way the agreement outlines can only ever be a starting point.

Bringing the expertise and knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working at the frontline to the effort to close the gap is a fine thing, although there is a risk that it still only brings our knowledge and expertise to a policy agenda pre-defined by largely non-Indigenous others. Lasting policy impact stems from policymaking that has an Indigenous social vision – the good life – at its core, and from the deliberate application of metic knowledge to understanding the dimensions of that vision and formulating a path toward achieving it. It will require something of all those who work in public policy. There is no ready reference or map for this journey. It is one where, to quote the Spanish poet Antonio Machado, “the road is made by walking”. Indeed, it is a serious challenge but if we are to be condemned by future generations for anything, it will be for the sheer lack of courage, vision and imagination that stops us from starting out in the first place.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 This idea is akin to Foucault’s concept of dispositif that I have argued elsewhere provides a powerful analytical perspective on the operational dynamics of the policy enterprise. See (Ritchie Citation2021)

2 This social constructionist approach to knowledge stands in stark contrast, and challenge, to hegemonic epistemological positions of contemporary policymaking where knowledge is positioned outside questions of meaning and independent of human thought as something to be discovered, articulated, and applied to solve problems.

3 Scott defines legibility as “the state's attempt to make a society legible, to arrange the population in ways that simplified the classic state functions of taxation, conscription, and prevention of rebellion. Having begun to think in these terms, I began to see legibility as a central problem in statecraft” (Scott Citation1998:2)

4 In some sense this idea is tautological. Knowledge requires knowers and to posit that some knowledge is of the people while other knowledge is not, is nonsensical. But for analytical purposes this distinction is employed to highlight the difference between metis and what Scott calls “epistemological” knowledge.

5 Some care is required in understanding metis as local. While there is undoubtedly some degree of territoriality in the idea of metis, there is equally the idea of particularity. As much as metis is local knowledge, i.e. pertaining to certain locations, it is also particular knowledge that belongs to specific groups of people who may in live in dispersed and multiple locations while retaining an identity and sense of belonging that transcends these localities. For example, 85% of Torres Strait Islanders live on mainland Australia however still retain a strong sense of Islander identity and access to the metic knowledge that forms part of this identity (Nakata Citation2007). This is a critical counter to the hegemonic localism at work in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise that I argue distorts popular and professional understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and identities and ultimately corrupts our policymaking efforts.

6 Perhaps one of the best examples of this kind of knowledge is what we have come to describe in the public sector as “judgement”. Anyone who has been involved in recruitment exercises that involve assessing candidates for senior roles in the APS will be aware of the importance attached to the “showing judgement”. Judges represents a form of public sectors know-how (metis) that is not something that can be taught – there are not APSC courses one can do in judgement. This is a knowledge and practice that is acquired in the doing and in the belonging and can only be acquired in situ.

7 Primarily quantitative data at that.

8 Often these policymakers, for the most part outsiders, proceed on their own terms and from their own cultural positions. Perhaps this is symptomatic of the political nature of modernist policymaking, but it is also an effect of the epistemic conflict that this paper is seeking to highlight. In any event, the dominant epistemic regimes within which the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy enterprise is carried out means that officials are singularly ill-equipped for the kind of policymaking that is theorised in the co-design rhetoric, which Indigenous people demand, and which is the sine qua non for better policy in the future.

9 This survey is necessarily brief and selective. Its purpose is to connect the concept of metis elaborated by Scott and deployed in this analysis to the rich work of Australian Indigenous scholars in a range of policy domains. The literature is diverse and growing and readers are urged to engage with it in a systematic and considered way.

10 I would argue that his position applies equally to any colonial institution including, most importantly, in the context of this article, the public sector.

References

- Askew, D. A., K. Brady, B. Mukandi, D. Singh, T. Sinha, M. Brough, and C. J. Bond. 2020. “Closing the Gap between Rhetoric and Practice in Strengths‐Based Approaches to Indigenous Public Health: A Qualitative Study.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 44 (2): 102–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12953.

- Bond, C. J., and D. Singh. 2020. “More than a Refresh Required for Closing the Gap of Indigenous Health Inequality.” Medical Journal of Australia 212 (5): 198–199.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50498.

- Boole, G. 1951. An Investigation of the Laws of Thought. New York, NY: Dover Publications.

- Brown, N. O. 1952. “The Birth of Athena.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 83: 130–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/283379.

- Bacchi, C. L. 2009. Analysing policy : what's the problem represented to be?, Frenchs Forest, N.S.W., Pearson.

- Campbell, J. L. 2002. “Ideas, Politics, and Public Policy.” Annual Review of Sociology 28 (1): 21–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141111.

- Charon, J. M. 1995. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Commonwealth 2009. “Strategic Review of Indigenous Expenditure: A Report to the Australian Government.” In Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

- DE Sousa Santos, B. 1998. “The Fall of the Angelus Novus: Beyond the Modern Game of Roots and Options.” Current Sociology 46 (2): 81–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392198046002007.

- Detienne, M., and J. P. Vernant. 1978. Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society. Hassocks: Harvester Press [etc.].

- Eze, E. C. 1997. Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Finlayson, A. 2006. “ The Problem?': Political Theory, Rhetoric and Problem-Setting.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 9 (4): 541–557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230600942034.

- Hacking, I. 1990. The Taming of Chance. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, P. M. 1972. “A Symbolic Interactionist Analysis of Politics.” Sociological Inquiry 42 (3-4): 35–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1972.tb00229.x.

- Heikes, D. K. 2015. “Race and the Copernican Turn.” The Journal of Mind and Behavior 36: 139.

- Hickman, S. 2016. Mêtis: Cunning Intelligence in Greek Thought. Southern Nights [Online]. Available from: https://socialecologies.wordpress.com/2016/02/23/metis-cunning-intelligence-in-greek-thought/

- Howlett, M., and I. Mukherjee. 2018. Routledge Handbook of Policy Design. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jennings, W., C. Bond, and P. S. Hill. 2018. “The Power of Talk and Power in Talk: A Systematic Review of Indigenous Narratives of Culturally Safe Healthcare Communication.” Australian Journal of Primary Health 24 (2): 109–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1071/PY17082.

- Kuhn, T. S., and I. Hacking. 2012. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Metta, M. 2015. “Embodying Mêtis: The Braiding of Cunning and Bodily Intelligence in Feminist Storymaking.” Outskirts 32: 1–21.

- Moreton-Robinson, A. 2017. “Relationality: A Key Presupposition of an Indigenous Social Research Paradigm.” In: Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies, edited by Andersen, C. & O’brien, J. M., Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- Nakata, M. N. 2007. Disciplining the Savages: savaging the Disciplines, Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- O'Brien, L. 2018. An Aboriginal Perspective. Adelaide: pers comm.

- Oliver, C. 2012. “The Relationship between Symbolic Interactionism and Interpretive Description.” Qualitative Health Research 22 (3): 409–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311421177.

- Pusey, M. 1991. Economic Rationalism in Canberra: A Nation-Building State Changes Its Mind. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Rigney, L. I. 2020. “Aboriginal Child as Knowledge Producer.” In Routledge Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies, edited by Hokowhitu, B., Moreton-Robinson, A., Thuhiwai-Smith, L., Andersen, C. & Larkin, S. Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- Ritchie, C. 2021. “Understanding the Policymaking Enterprise: Foucault among the Bureaucrats.” In Learning Policy, Doing Policy: how Do Theories about Policymaking Influence Practice? edited by Mercer, T., Ayres, R., Head, B., & Wanna, J. Canberra: ANU PRESS.

- Roediger, D. R. 2007. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. London: Verso.

- Santos, B. D. S. 2007. Another Knowledge is Possible: Beyond Northern Epistemologies. London: Verso.

- Schneider, A. L., and H. M. Ingram. 1997. Policy Design for Democracy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- Schrom, P. A. 2016. “The Enlightenment and the Origins of Racism.” Dissertation/Thesis, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Scott, J. C. 1985. Weapons of the Weak: everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Scott, J. C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Schneider, A.L. & INGRAM, H. M. 1993. Social Construction of Target Populations: Implications for Politics and Policy. The American Political Science Review, 87, 334–347.

- Scott, J. C. 1996. “State Simplifications: Nature, Space, and People.” Nomos 38: 42.

- Scott, J. C. 1998. Seeing like a State: how Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Semali, L. M., and J. L. Kincheloe. 1999. What is Indigenous Knowledge?: Voices from the Academy. Routledge, New York NY.

- Walter, M. 2018. The Voice of Indigenous Data: Beyond the Markers of Disadvantage. Griffith University, Brisbane.

- Walter, M., and C. Andersen. 2013. Indigenous Statistics: A Quantitative Research Methodology. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Wolfe, P. 1999. Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. London; New York: Cassell.

- Wolfe, P. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.