Abstract

Impact is essential to research, policymaking and implementation. Yet impact is often misunderstood or poorly defined. For public policy scholars, concerns about impact exist largely on two planes. On one level scholars seek to understand the impacts of policy interventions. On a second level scholars aim for their public policy research to generate real-world impact. These two concerns – the “what” and the “how” of research – are often treated separately. In this article, we argue that it is worthwhile joining up these concerns about impact. This is possible, we suggest, through a combination of logic models and a novel rethink of the usual “pathway to research impact”. The article introduces two research co-design tools aimed at improving the likelihood of achieving research impact, while also improving understanding of those impacts: an integrated knowledge translation (IKT)-informed logic model and an implementation science (IS)-derived Pathway to Impact. We draw on a multi-year research co-creation project to develop the Infrastructure Engagement Excellence (IEE) Standards for Australia’s $250 billion infrastructure sector. This co-creation project illustrates the development of the logic model, Pathway to Impact and consequent research co-design process. Together, these tools can support policy scholars’ efforts to produce impactful research while also creating better understanding of policy and practice impacts, and how to achieve them. We conclude that genuine and robust research co-design requires researchers to commit not only to undertaking research with rigor, but also a willingness to dedicate thought and effort to the relationship between what research activities are carried out and how those processes can advance policy and practice outcomes and impact.

1. Introduction

Policy scholars and public servants recognize the need to bridge the research to policy gap. In recent years, policy scholars have attempted to devise pathways to research impact to inform policy and deliver societal benefits (Chubb and Reed Citation2018). Aligned work in other research disciplines, especially health, demonstrates that such pathways are commonly long (Morris, Wooding, and Grant Citation2011), frequently confusing, so disparate in method as to hinder comparability, and sometimes ineffectual (Morgan Jones and Grant Citation2013). We argue that this situation exists partly because key pieces of the research impact planning and assessment puzzle have been missing. Here, we offer researchers and policymakers those missing pieces in the form of a logic model and reimagined Pathway to Impact. We detail a research-derived process to facilitate consideration of desired impacts from the earliest co-design stages and present clear steps toward achieving those impacts through to implementation.

This Special Issue presents an important opportunity to consolidate current knowledge and bring ideas from diverse academic fields more centrally into the policy studies arena. This article contributes to that effort in three important ways. First, we problematize impact, noting that the very basis of the issue at hand is often poorly defined and missing important perspectives. Second, we address the lack of clear processes through which policy scholars and practitioners can work effectively together to co-design research better suited to informing decision-making and producing impact. Finally, through our focus on the Infrastructure Engagement Excellence (IEE) Standards (the Standards) as an illustrative example, we demonstrate how the combined use of research co-design, a Pathway to Impact, logic models, and empathic engagement of research end-users can support research adoption and impact. The usefulness of this holistic approach to research impact in a major policy area suggests promising applicability for a range of other leading policy concerns.

1.1 Problematizing impact

Impact is a troublesome concept. A neutral term, it is often interpreted in its most negative sense (Bice Citation2013) and is commonly conflated with outputs (Vanclay Citation2002). In its more sophisticated sense – and the one that we adopt – it is defined as the positive or negative consequences of a policy or intervention (Esteves, Franks, and Vanclay Citation2012). The act of defining of what constitutes “impact” often occurs in top-down ways (Esteves et al. Citation2017). Such processes regularly fail to acknowledge or accommodate the lived experiences of community members; the very people who ultimately shoulder the results of policy or practice decisions (Bice Citation2020). In other cases, impact is deployed after-the-fact, a postmortem description of what happened, detailing “the final level of the causal chain” (White Citation2010, 154). Impact is essential to research, policymaking and implementation, whatever its definition. Yet, it is also a term used uncritically, and it proves challenging to assess, especially in relation to social and community interests (Esteves, Franks, and Vanclay Citation2012).

For public policy scholars, concerns about impact exist on two planes. On one level, policy scholars seek better ways to understand the impacts of the policy issues they are researching. On the second, and more abstracted level, policy scholars want to ensure that the research they perform advances public policy and practice; that it is research for impact, informing decision-making to influence outcomes. These two concerns – the “what” and the “how” of research – are often treated separately. In this article, we argue that it is worthwhile joining up these concerns about impact. This is possible, we suggest, through a combination of logic models and a novel rethink of the usual pathway to research impact. These research co-design tools can facilitate policy scholars to produce impactful research while also creating better understanding of policy and practice impacts, and how to achieve them.

This two-birds-one-stone approach has recently been piloted in Australia’s infrastructure sector, offering a timely example of the interplay between impactful research, policy, and practice. Government selection, planning, and delivery of major infrastructure projects has all the hallmarks of policy interventions with major impacts. Costing hundreds of millions (and often billions) such projects are time- and resource-intensive, demand a multitude of expertise, are highly visible, often disruptive and frequently loud. Infrastructure delivery is, undoubtedly, one of the most conspicuous areas of policy implementation. Its impacts, bad and good, are manifest and material. Infrastructure also offers a helpful metaphor for understanding key concepts of “output”, “outcome” and “impact”. Take the delivery of a major road tunnel as an example. The completion of the tunnel is an output that achieves the outcome of greater road traffic capacity that has the impact of improving users’ wellbeing through reduced stress from gridlock. Fortunately, for a conversation like that being held in this Special Issue, these characteristics make infrastructure a policy area ripe for consideration of how we can better capture and assess impacts, and the frameworks that may assist us to do so.

In this article, we explore the origination of the IEE Standards (The Standards) as a recent, illustrative example to demonstrate the application and usefulness of logic models and Pathways to Impact for achieving research impact, especially where research is co-designed. The Standards are an evidence-based framework co-created with industry (incorporating government) to deliver a systematic understanding of the characteristics of community engagement to influence successful infrastructure project delivery. Generally, successful delivery is understood as the selection of infrastructure projects that: meet agreed societal needs; are planned with current and future users, community values, and the environment in mind; and that are delivered on-time and on-budget through processes that address communities’ concerns, reduce socio-environmental risks and harms, and achieve desirable community outcomes.

In introducing the logic model and Pathway to Impact we developed for the research project that generated the Standards, we respond to the Special Issue’s concerns about how we might better capture and assess impact. We offer a response to the questions of “What methods and frameworks are best placed to assist us with this?” and “What are our metrics beyond outputs, that include broader outcomes – in this case socio-environmental sustainability and optimal outcomes for communities accessing infrastructure?” Through addressing these important questions, we also look to the critical stages of policy/practice adoption and implementation which continue to prove challenging for policymakers and researchers alike. The article consequently contributes to a growing field of literature in integrated knowledge translation (IKT) (e.g. Kothari and Wathen Citation2017) and research impact (Greenhalgh et al. Citation2004). It also advances knowledge concerning the role of community engagement in major infrastructure delivery (Bice, Neely, and Einfeld Citation2019; Cowell and Devine-Wright Citation2018; EL-Gohary, Osman, and EL-Diraby Citation2006; Innes and Booher Citation2003a) by providing research-derived tools to assess the quality of that engagement and its influence on project outcomes.

In the sections that follow, we draw on scholarship in implementation science (IS), IKT, and research co-design (co-design) to explore how these fields offer practical means of envisioning, evaluating, and understanding the processes and outcomes necessary to achieve research impact. We demonstrate how this holistic co-design model can overcome traditional barriers to adoption and implementation of research-derived policies and tools. Importantly, the research co-design process and tools introduced here may also improve the likelihood and degree of research impact with policymakers and industry. The creation of the IEE Standards demonstrates what can be achieved when we seek a multiplanar and sophisticated understanding of impacts; when we produce more impactful research about impacts.

The article proceeds by briefly situating the creation of the IEE Standards within the frame of major infrastructure policy and delivery in Australia. We offer a concise introduction to community engagement, as a means of both explaining the focus of the Standards and also demonstrating the challenges that arise when attempting to assess its impacts. We then introduce the logic model and the Pathway to Impact that informed the co-creation of the IEE Standards and aimed to generate research-derived tools for policy and societal impact. The article concludes with a discussion of how the logic model and Pathway to Impact allowed the research team and industry co-researchers to address barriers and facilitators to research impact, while simultaneously creating a tool that assists practitioners to better identify and assess their own impact.

2 Policy problem: major investment, plenty of engagement, limited understanding of quality or impact

2.1 A brief introduction to Australia’s infrastructure sector

The AU$250 billion Australian infrastructure sector is thriving, even during a pandemic that has wrought economic damage still being calculated. In June 2020 Australia’s Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, announced the fast-tracking of $15 billion in national infrastructure projects as part of the Government’s COVID-19 stimulus package. Population growth – and now economic recovery – is driving Australia’s urgent requirements for new and upgraded infrastructure, including energy, water, transport, housing, and social needs. Responsibility to deliver these resources stretches across government and these diverse industries, also involving disciplines of architecture, construction, urban planning, engineering, and social welfare. The investments are massive, the stakeholders varied.

Not all projects, however, are acceptable to Australian communities. The public–private partnerships used to deliver a considerable portion of these projects, for instance, have come under scrutiny (Hodge, Greve, and Boardman Citation2017), raising accountability issues (Stafford and Stapleton Citation2017), and spurring socio-economic critique (Zwalf, Hodge, and Alam Citation2017). Recent examples from around Australia show that many communities are unhappy with the way certain projects have been proposed or delivered (DE Martinis and Moyan Citation2017). From the industry perspective, social opposition contributes to increased costs and barriers to infrastructure delivery, including substantial delays and cancelations (Bice, Neely, and Einfeld Citation2019; Harris, Hodges, and Schur Citation2003). This is not to mention the stresses and difficulties placed upon infrastructure project staff. From communities’ perspectives, there may be dissatisfaction with the ways in which they are being engaged in the planning and delivery of major projects, or simply with the projects themselves. Meanwhile, the combined stresses of the pandemic mean that many communities are feeling compounded pressures which may result in compassion fatigue (Montemurro Citation2020; Luo et al. Citation2020), reduced resilience, and diminished willingness to accommodate the disruptions inherent to infrastructure delivery.

2.1.1 Community engagement to manage infrastructure impacts

The variety of concerns above is commonly captured under the banner of community engagement, the practice at the core of the IEE Standards. A substantial literature base provides insights into the theory and practice of community engagement (e.g. Arnstein Citation1969; Day Citation1997; Fischer Citation2000; Innes and Booher Citation2003b). Policy scholarship is well represented, with researchers analyzing national and international efforts to integrate community engagement into policy planning or project delivery (e.g. Alford and Yates Citation2016; Cowell and Devine-Wright Citation2018; Nabatchi and Jo Citation2018).

For purposes of this article, community engagement refers to commitments and activities to involve community members in policy and project planning, delivery, or evaluation processes. This involvement may range from informing communities through direct communication in the forms of newsletters or websites, to fielding questions at town hall forums, from establishment of representative community consultative committees to deliberative democratic processes. Studies demonstrate that engagement on the more consultative end of the spectrum is consistently more successful (Gutmann and Thompson Citation2009). Such consultations are underpinned by values, philosophies, and approaches to inform or involve communities affected by initiatives, including infrastructure delivery (Bohman Citation2000). Across the board, community engagement studies demonstrate the importance of community empowerment to make influential decisions concerning project design and implementation processes (Cowell and Devine-Wright Citation2018).

Legislation or policy mandates also inform effective community engagement (Day Citation1997; Innes and Booher Citation2004). Many Australian states and territories require stakeholder engagement as part of the approvals process at various project-implementation stages. Very recently, several states have begun investigating ways to improve the engagements driven by these requirements. Although supported in policy, community engagement is not without its critics. Certain scholars question the effectiveness of engagement efforts (Abelson et al. Citation2003; Cowell and Devine-Wright Citation2018), the equal participation of vulnerable or Indigenous communities (Nish and Bice Citation2012), and the extent to which deliberative engagement is meaningful, influential, or in the worst cases, tokenistic (Dryzek Citation2002). This critical literature illustrates that policy and regulation to guide best practice community engagement and accountability remains wanting.

A parallel body of gray literature details concerns related to defining and implementing community engagement, especially as a professional practice. Despite a scholarly and practical focus on community engagement as a process, few studies or reports adopt empirical approaches to explore the experiences of “doing” community engagement. A clear understanding of the characteristics and quality measures of best practice community engagement is also lacking, despite the influence and importance of community engagement to major infrastructure project success, and to community outcomes. This circumstance limits policymakers’ and developers’ capacity to assess, model, plan for or evaluate the characteristics of community engagement to support optimal project outcomes, let alone promote social good (Cox et al. Citation2010).

Policymakers and community engagement practitioners lack reliable insights into the qualities that define the community engagement characteristics necessary to support optimal project outcomes. Social data on the impact of infrastructure delivery is also limited. Yet research demonstrates that poor engagement contributes to billions in lost investments and poor social outcomes (Bice, Neely, and Einfeld Citation2019). The connections between responsible industry behaviors and community wellbeing are widely recognized (Bice Citation2015b; Bice Citation2015a; Bice and Moffat Citation2014), as are connections between poor engagement, lost social license, and community opposition (Moffat and Zhang Citation2014). Despite all of this, policymakers and practitioners generally lack evidence-based guidance or standards for community engagement, specific to infrastructure project selection, planning, and delivery. This is where the IEE Standards come in.

3. Discussion: co-design of the IEE Standards

Our research to develop the IEE Standards built on three main components. First, it was informed by our broader understandings of community engagement, as defined through the literature. Second, we drew on our prior research into community engagement and social impacts of major projects. Finally, our industry partners for the project were convinced that high-quality community engagement is critical to successful infrastructure project delivery and were seeking better evidence to demonstrate the linkages between project outcomes and community engagement. We therefore began with a focus on how community engagement and social risk can influence major infrastructure policy and project outcomes.

In addressing these issues, we were also responding directly to a major knowledge gap identified by industry in a co-designed research agenda (Bice, Neely, and Einfeld Citation2019). In our efforts to contribute to filling these identified gaps, we found that producing research evidence in an area of infrastructure delivery unaccustomed to the use of research in decision-making (i.e. community engagement) presented a number of challenges but also opportunities. This work spurred our interests in how collaborative co-design of research – including the use of a logic model and the Pathway to Impact introduced here – can better bridge the research to policy/practice gap. In turn, this bridging can facilitate research to have more meaningful, and hopefully more immediate, impact.

3.1 Customer empathy mapping: understanding end-users’ needs

Early work on the Standards development was based on a vision developed through “customer empathy mapping” with industry representatives. Through this exercise, end-users told us that a novel, robust framework defining the key characteristics of engagement excellence could provide much-needed guidance to raise industry standards while simultaneously offering tools to assess and manage community engagement quality. From a research perspective, we were also very interested in how application of techniques from IS (Bauer et al. Citation2015), IKT (Kothari and Wathen Citation2017) (two disciplines more commonly influential in health sciences), and research co-design could support achievement of research implementation for policy and social impact (Greenhalgh et al. Citation2019). All of these aligned interests were driven by the belief that an improved understanding of the qualities and indicators that characterize community engagement excellence could enhance policymakers’ and project developers’ capacities to plan, monitor and evaluate their community engagement activities. It was argued that this, in turn, would support improved project performance and optimal community outcomes.

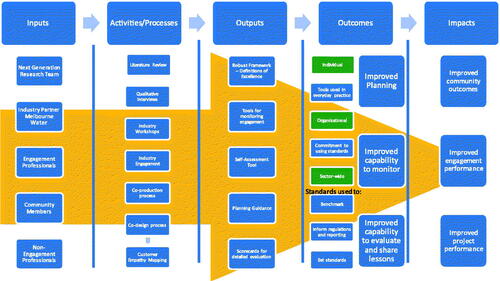

3.2 Logic model: creating a framework for thinking through research design to research impact

To advance these aims, our team required a coherent framework for “thinking through to impact” from project commencement. We produced a simplified logic model () to help understand how an engagement excellence framework with validated indicators would support improved outcomes for infrastructure projects and communities. Logic models are commonly used in knowledge mobilization (especially in health sciences) (Mills, Lawton, and Sheard Citation2019) and research evaluation (McLaughlin and Jordan Citation1999) but tend to take a more traditional approach to the transfer of research knowledge to end-users. These logic models, for instance, tend to begin where research ends (i.e. with dissemination) and then flow through to impact (Phipps et al. Citation2016). Our logic model focuses instead on the research process itself, with: outlining the resources that were required, the activities undertaken, the products and tools produced, and the resulting changes and benefits. For example, key inputs for this work largely focused on human resources including our research team, industry partners, and community members. Research activities ranged from the customer empathy mapping noted earlier to industry workshops and a more traditional literature review. These inputs and activities generated a range of outputs, such as the IEE Standards themselves, to support outcomes including the establishment of industry standards for community engagement. Desired impacts of this process included generating improved community outcomes, engagement, and project performance.

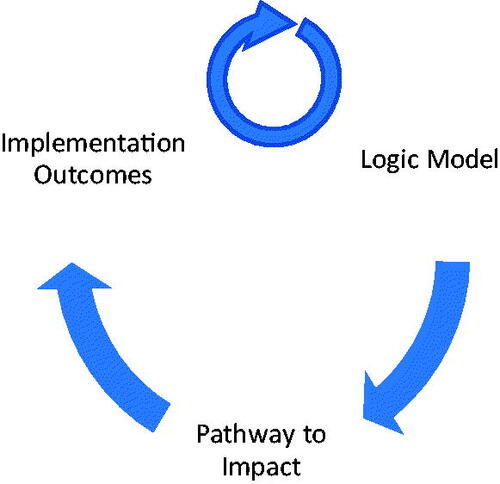

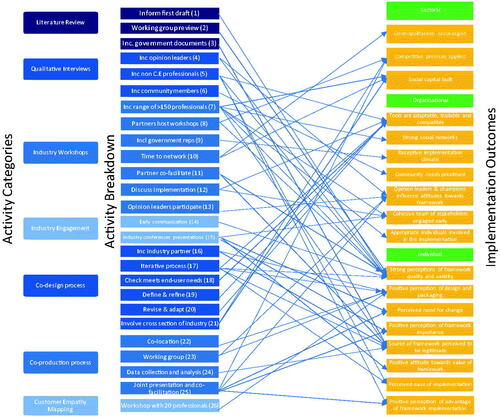

While the logic model visualizes this process as mostly step-wise (for ease of presentation), it is important to keep in mind that achieving impact is not necessarily a linear process; impact is not teleological. Rather, achieving impact is a dynamic and iterative process, with processes and desired outcomes requiring regular refinement. provides a simple visual illustration of the interactive nature of our logic model, Pathway to Impact and implementation outcomes (early, middle, and late-stage). This reinforcing feedback loop is a reminder that these processes are happening in an iterative way, both within the individual logic models, the pathway and research implementation and between one-another.

3.2.1 Benefits of using a logic model

The logic model allowed our research team to consider the impact of the IEE Standards holistically, despite certain limitations of its visual representation. First, the logic model forced us to consider and define desired outputs, outcomes and impacts, and to consider their interrelations. This process forced us to articulate the differences between outputs, outcomes, and impact, an important step perhaps often missed. For example, the logic model clarifies that “tools for monitoring engagement” are an output, seeing those “tools used in everyday practice” is an outcome and those tools’ contributions to “improved engagement performance” are an impact ().

The logic model also encouraged a multi-level consideration of the outcomes sought. It helped us to identify clearly that outcomes would be needed at sectoral, organizational, and individual levels in order to raise the standards of community engagement across the infrastructure industry (). Identifying the key outcomes that would need to be achieved at the sectoral level aimed to ensure that the framework would be relevant across the entire infrastructure industry, for planning, monitoring, and evaluation purposes. Outcomes identified at the sectoral level therefore included use of the framework for benchmarking, informing regulation and reporting, and setting standards across the industry (). Outcomes at an organizational level represented the clear results needed to support sector-level outcomes, namely “commitment to using the Standards”. Meanwhile, individual-level outcomes proved more practical, with a focus on seeing Standards-related tools “used in everyday practice” ().

In articulating the outcomes of the Standards, the logic model also highlighted the need for us to consider how these outcomes would be achieved. The logic model fulfilled a critical, foundational need in terms of answering our what questions. It helped us to be clear about what activities and resources were required to produce which outputs to lead to what outcomes and impacts. As such, the logic model contributes a helpful prototype for researchers and policymakers to think through the diverse engagements, commitments, and outcomes that will be necessary to pursue to improve the likelihood that research undertaken will have policy or societal impact. But it did not offer much help when it came to articulating how to move from “inputs” to “impacts”. This is where our Pathway to Impact became crucial.

3.3 Pathway to impact: moving from what to do toward how to achieve impact

The Pathway to Impact detailed in : Pathway to Impact step diagram, describes the building blocks that we suggest are required for a research-derived intervention to be implemented successfully. Our Pathway acknowledges the basic structure common among certain research funding councils, including the Australia Research Council (AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH COUNCIL Citation2020) and the UK Research Excellence Framework (Grant and Hinrichs Citation2015). These models, however, are more akin to the logic model presented above. They tend to be positioned as “results chains” (Tilley, Ball, and Cassidy Citation2018) that focus on the “whats” but offer little support in assisting researchers to think about the “hows”, including how, exactly, to reach the impacts listed in those models (Boswell and Smith Citation2017). Such Pathways have been controversial and drawn sharp criticism for their poor efforts to clearly define impact and for their limited advice to researchers on how to adopt strategic approaches (e.g. research impact assessment, evaluation, and causal-mapping) to generating research with impact (Watermeyer Citation2016). Research shows that Pathways in the vein of the UK REF offer guidance at such a generic level that in 2014 alone, researchers developed 3709 unique ways to reach research impact (Grant and Hinrichs Citation2015). On the one hand, such room for interpretation can support research creativity. On the other hand, it suggests that, at least in the case of the UK REF Pathway model, its utility was limited. In March 2020, the UK Government dropped its requirement for Pathways to Impact within certain major funding applications, citing a desire to reduce bureaucracy and arguing that, after a decade of impact reporting requirements, impact is now “a central consideration” embedded in judging research (EPSRC Citation2020).

The research to impact model we present in this article attempts to address the known short-comings of common Pathways to Impact. It is clear that such pathways are well-intentioned in their efforts to encourage researchers to think about their end-users and production of societal benefit. But they have also shown only limited success. We suggest that it is not the focus on a pathway to impact that is the problem, per se, but the types of questions and foci presented in those models. By shifting the questions and considerations typical of a pathways model into our logic model, and by then building a complementary but uniquely focused Pathway to Impact along with that logic model, we offer a novel approach to generating research impact.

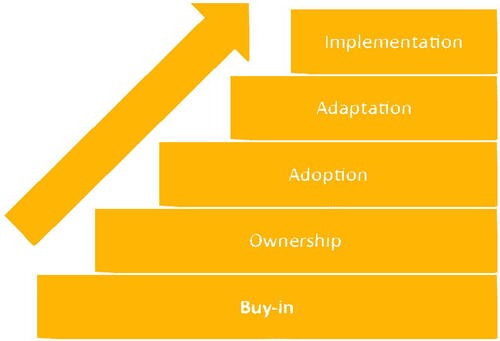

3.3.1 Building blocks for a Pathway to Impact

Our Pathway to Impact is neither flat nor linear. Instead, it involves an important series of building blocks that support progress toward the next step while providing a reinforcing foundation for progress. The pathway recognizes that throughout each research stage and ongoing knowledge translation, different and appropriate strategies and approaches are required. It therefore helps researchers to identify areas that they are likely able to influence, a key step toward achieving the research implementation that is usually closely linked to impacts.

3.3.2 From building buy-in through to implementation

Our Pathway to Impact begins with buy-in as the foundational building block (). While early buy-in to the IEE Standards was crucial, it was also vital that buy-in to the Standards and their associated tools is ongoing. Ownership, therefore, becomes our second building block. For our team, ownership meant that industry did not see the IEE Standards as an academic exercise but as one that was meaningful and applicable to them, while also offering the robustness of research. This meant ensuring that our industry partners actively contributed to and engaged in the creation of the Standards from the outset, genuinely shaping both the research results but also the process used to create them. The third building block is adoption. Here, the building blocks of buy-in and ownership support a situation in which organizations and individuals within them are willing to use the Standards and associated tools. Our fourth building block, adaptation, then seeks to ensure that tools produced are refined to be compatible with existing workflows and systems. For the IEE Standards, this involved a trial period where partners tested the tools and we iteratively refined the tools designed for Standards implementation. Adaptation work to refine the Standards themselves, and their indicators, is ongoing. Finally, our Pathway leads us to implementation. Implementation seeks to support wide-scale use and uptake by industry to achieve the outcomes and impacts set out in our logic model ( and .

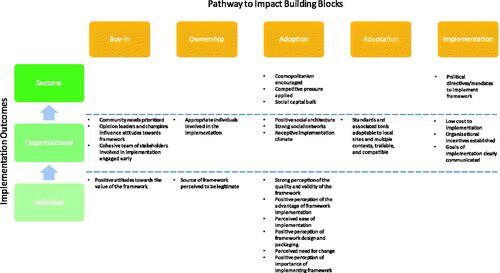

The Pathway to Impact also necessarily operates at sectoral, organizational, and individual levels (), similarly to the logic model. This multi-level functioning recognizes first, that outcomes are required at each of these levels and that, secondly, in order to progress along the pathway to impact, preliminary outcomes at each of these levels also need to be achieved. To understand what would facilitate implementation, two theories related to research design and implementation were used: the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al. Citation2009) and IKT theory (Graham, Mccutcheon, and Kothari Citation2019; Kothari, Mccutcheon, and Graham Citation2017; Kothari and Wathen Citation2017). These theories proved especially crucial in identifying the key outcomes that would be required for the Standards’ benefits to be realized, while providing a sturdy scholarly basis for the processes and models we developed. It is therefore helpful to provide a very brief overview of these theories before finalizing our explanation of the Pathway to Impact. A detailed explanation of the role of IKT and IS in guiding creation of this Pathway is available in Jones and Bice (2021).

3.3.3 Implementation science

IS is traditionally focused on implementing health interventions into routine practice (Bauer et al. Citation2015). IS seeks to understand the methods and strategies that support the systematic uptake of evidence-informed interventions into everyday practice (Eccles and Mittman Citation2006). In so doing, it offers empirically validated frameworks to guide processes for evidence uptake, in this case, the CFIR (Eccles and Mittman Citation2006; Damschroder et al. Citation2009). By increasing understanding of how behavioral, organizational, and other factors affect the uptake of treatments and practices, as well as how best to sustain the effectiveness of organizational and management interventions, greater empirical, and theoretical knowledge can be generated. This in turn supports impact being realized.

The CFIR provides a comprehensive set of constructs that influence implementation (Damschroder et al. Citation2009). This provided us with a helpful guide for what would need to be accomplished for the Standards and their associated tools to be implemented. For instance, the CFIR outlines characteristics of an intervention (in this case the IEE Standards and associated tools) demonstrated to be important for implementation success. This includes traits, such as the strength and quality of evidence on which an intervention is based, adaptability, trialability, design quality, and the implementation climate, among others. The CFIR also details research-derived “enablers” and “barriers” to research implementation.

3.3.4 Insights for practice: applying IS and IKT to research design

By interrogating the CFIR’s key characteristics and constructs, we were able to identify specific outcomes at the sector, organizational, and individual levels that would be necessary to achieve our ultimate aim of seeing the Standards implemented across the infrastructure sector. Importantly, we also identified where along our Pathway to Impact it would be important for these outcomes to be achieved (). For example, the establishment of “strong social networks” was important to generate as an outcome within the “Adoption” phase of our Pathway to Impact. It was these networks at the organizational level, combined with sectoral and individual level outcomes, such as “a strong perception of the quality and validity of the Standards”, that supported progress toward implementation (). Application of the CFIR to help define outcomes along our Pathway to Impact also made clear that we would need a research process that was highly engaged with our industry partners and participants, if we were to generate the buy-in and ownership necessary to move toward implementation. Importantly – and similarly to the logic model’s linear diagram – for the Pathway to be successful, it was important to consider how outcomes in the later portions of the pathway journey were influenced early on. This meant that we were consistently questioning whether and how early phase co-design and knowledge translation activities could influence the achievement of later-stage outcomes.

4. Getting to work: co-creation as a means to progress impact

Both the CFIR-informed Pathway to Impact and the IKT-informed logic model emphasized the need for industry involvement in the creation of the Standards. Importantly, early co-design work with industry, including the customer empathy mapping and an industry working group, identified opportunities and barriers for ultimate research implementation, making clear that the research process itself must directly involve industry to encourage ownership of research results and later adoption of research outputs.

A co-design method was therefore devised, informed by the implementation outcomes defined in our Pathway to Impact (). This co-design process with industry – which is the subject of other papers – provided a means for achieving the multi-level outcomes defined in our logic model and laid out across our Pathway to Impact. The models’ results made clear that deep participant involvement would be essential to overcoming certain of the identified barriers to implementation. We needed an innovative, collaborative research process that would meet the needs of industry, encourage swift industry adoption and also support long-term implementation. The resultant co-creation process involved multi-year, sector-wide research that worked directly with industry to understand their needs and perspectives to inform the Standards’ creation.

4.1. Lessons to inform practice: how the logic model and pathway to impact informed the research

Lessons to inform research for impact practice can also be derived from our application of the logic model and Pathway to Impact to our research method and execution. With the research co-design guided by IS theory and the co-production method informed by IKT, we developed the research method with implementation in mind. The method, led by the research team in close collaboration with a major industry partner, involved over 150 community engagement practitioners. The main components of the research method are noted in and summarized in .

Table 1. Research processes used to develop the IEE Standards.

We involved the main industry co-production partner at each step of the process, including reviewing methodology, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and dissemination. IKT scholarship informed processes and steps to optimize the collaboration. A further breakdown of each stage of the Standards development is outlined in , for interested readers. The detailed, numbered processes/activities in appear in the related: to demonstrate which activities and processes supported implementation outcomes being achieved. Arrows drawn between specific research activities and the multi-level outcomes drawn from our Pathway to Impact illustrate the connections between all research activities and implementation outcomes. It is important to note that this research is ongoing, so these connections represent the early phase of the Standards development. highlights the complexity of implementation, the different outcomes that our research team needed to work toward and the multiple activities and processes that needed to be incorporated into the design of the Standards. This helped us to visualize how our co-design approach supported achievement of our Pathway to Impact outcomes and provided a strong foundation for further research and future knowledge translation activities.

5. New directions and recommendations for improvement

5.1. Linking pieces of the puzzle: iterative design

With the above co-design activities and links to Pathway outcomes in mind, we returned to the logic model to update the key resources and stakeholders required to be involved in the development of the Standards and the processes necessary for success (). Now that the first phase of the Standards co-development is complete, future activities and outcomes will need to be revised and further knowledge translation strategies undertaken to progress the Standards’ adoption and implementation. Our approach to implementation has acknowledged that implementation is a dynamic process. We also understand it as a complex system, given the variety of organizations and stakeholders, the “messiness” of the issues at hand, the propensity for self-organization and the layering of interactions and effects (Boulton Citation2010; Cairney Citation2012).

5.2. Next steps

Our discussion here explains the early phases of our approach, including the creation of a logic model, a reimagining of the usual Pathway to Impact and the careful interlinkage between research co-design activities and desired outcomes and, ultimately, impacts. We expect that, over the coming years our research co-design framework will require continued reflection and assessment to update the logic model, Pathway, implementation outcomes, and processes and activities. Listening, learning and further collaboration with industry and government will be essential if our vision for the IEE standards is to be achieved.

5.3. Insights for researchers and policymakers

Our work here demonstrates the strengths and opportunities for genuine research co-design to advance policy and practice outcomes and impacts. It also shows that this work is neither simple nor easy. Genuine and robust research co-design requires that researchers commit not only to undertaking research to the very best of their abilities, but also that they are willing to dedicate thought and effort to the relationships between what research activities they carry out and how those processes influence real-world impact. Our work here suggests that a theoretically informed approach to “research to impact” or “knowledge to action” can generate the research and policy outcomes desired by both public policy scholars and industry. Importantly, at a time when the value of a pathway to impact is being questioned in certain places, our work also demonstrates that it is perhaps not the pathway itself that is the issue, but the way in which such pathways have traditionally been structured. A reimagining like that we offer here demonstrates the continued importance of Pathways to Impact while also offering researchers and policymakers a suite of research co-design tools that, when used together, can enhance the capacity of research to generate change.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the staff at Melbourne Water for their time and support to develop the IEE standards.We thank the Major Partners of the ANU Institute for Infrastructure in Society: Lendlease, the Queensland Government, Transurban and the Victorian Government for their active participation in and continued support for this work. We also wish to thank all industry participants who took part in the co-design process. Kirsty O’Connell (Industry Director for the Next Generation Engagement Program) provided significant support to recruit industry participants and facilitate their involvement throughout the research. We also thank Assistant Professor Kei Nishiyama (Doshisha University, Tokyo) for his research assistance during the development of the Standards.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abelson, J., P. G. Forest, J. Eyles, P. Smith, E. Martin, and F.-P. Gauvin. 2003. “Deliberations about Deliberative Methods: Issues in the Design and Evaluation of Public Participation Processes.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 57 (2): 239–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x.

- Alford, J., and S. Yates. 2016. “Co‐Production of Public Services in Australia: The Roles of Government Organisations and Co‐Producers.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 75 (2): 159–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12157.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Australian Research Council. 2020. Research Impact Principles and Framework [Online]. ARC. [accessed 27 November 2020]. https://www.arc.gov.au/policies-strategies/strategy/research-impact-principles-framework

- Bauer, M. S., L. Damschroder, H. Hagedorn, J. Smith, and A. M. Kilbourne. 2015. “An Introduction to Implementation Science for the Non-Specialist.” BMC Psychology 3: 32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9..

- Bice, S. 2013. “No More Sun Shades Please: Experiences of Corporate Social Responsibility in Remote Australian Mining Communities.” Rural Society Journal 22 (2): 138–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.2013.22.2.138.

- Bice, S. 2015a. “Bridging Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Impact Assessment.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 33 (2): 160–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2014.983710.

- Bice, S. 2015b. “Corporate Social Responsibility as Institution: A Social Mechanisms Framework.” Journal of Business Ethics, Early Online Release 1-18.

- Bice, S. 2020. “The Future of Impact Assessment: Problems, Solutions and Recommendations.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 38 (2): 104–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1672443.

- Bice, S., and K. Moffat. 2014. “Social Licence to Operate and Impact Assessment.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 32 (4): 257–263. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2014.950122.

- Bice, S., K. Neely, and C. Einfeld. 2019. “Next Generation Engagement: Setting a Research Agenda for Community Engagement in Australia's Infrastructure Sector.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 78: 290–310.

- Bohman, J. 2000. Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Boswell, C., and K. Smith. 2017. “Rethinking Policy ‘Impact’: Four Models of Research-Policy Relations.” Palgrave Communications 3 (1): 44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0042-z.

- Boulton, J. 2010. “Complexity Theory and Implications for Policy Development.” Emergence: Complexity and Organisation 12: 31–40.

- Cairney, P. 2012. “Complexity Theory in Political Science and Public Policy.” Political Studies Review 10 (3): 346–358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9302.2012.00270.x.

- Chubb, J., and M. S. Reed. 2018. “The Politics of Research Impact: Academic Perceptions of the Implications for Research Funding, Motivation and Quality.” British Politics 13 (3): 295–311. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-018-0077-9.

- Cowell, R., and P. Devine-Wright. 2018. “A ‘Delivery-Democracy Dilemma’? Mapping and Explaining Policy Change for Public Engagement with Energy Infrastructure.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 20 (4): 499–517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1443005.

- Cox, D., M. Frere, S. West, and J. Wiseman. 2010. “Developing and Using Local Community Wellbeing Indicators: Learning from the Experience of Community Indicators Victoria.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 45 (1): 71–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2010.tb00164.x.

- Damschroder, L. J., D. C. Aron, R. E. Keith, S. R. Kirsh, J. A. Alexander, and J. C. Lowery. 2009. “Fostering Implementation of Health Services Research Findings into Practice: A Consolidated Framework for Advancing Implementation Science.” Implementation Science, 4: 50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

- Day, D. 1997. “Citizen Participation in the Planning Process: An Essentially Contested Concept?” Journal of Planning Literature 11 (3): 421–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/088541229701100309.

- DE Martinis, M., and L. Moyan. 2017. “The East West Link PPP Project’s Failure to Launch: When One Crash‐through Approach is Not Enough.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 76 (3): 352–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12243.

- Dryzek, J. S. 2002. Deliberative Democracy and beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Eccles, M. P., and B. S. Mittman. 2006. “Welcome to Implementation Science.” Implementation Science 1 (1): 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

- EL-Gohary, N. M., H. Osman, and T. E. EL-Diraby. 2006. “Stakeholder Management for Public Private Partnerships.” International Journal of Project Management 24 (7): 595–604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2006.07.009.

- EPSRC. 2020. Change to Pathways to Impact.London: UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. Available: https://epsrc.ukri.org/funding/applicationprocess/changes-to-pathways-to-impact/. Accessed: 3 June 2021.

- Esteves, A. M., D. Franks, and F. Vanclay. 2012. “Social Impact Assessment: The State of the Art.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30 (1): 34–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2012.660356.

- Esteves, A. M., G. Factor, F. Vanclay, N. Götzmann, and S. Moreira. 2017. “Adapting Social Impact Assessment to Address a Project’s Human Rights Impacts and Risks.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 67: 73–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.07.001.

- Fischer, F. 2000. Citizens, Experts, and the Environment: The Politics of Local Knowledge. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Graham, I. D., C. Mccutcheon, and A. Kothari. 2019. “Exploring the Frontiers of Research co-Production: The Integrated Knowledge Translation Research Network Concept Papers.” Health Research Policy and Systems 17 (1): 88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0501-7.

- Grant, J., and S. Hinrichs. 2015. The Nature, Scale and Beneficiaries of Research Impact: An Initial Analysis of Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2014 Impact Case Studies. HEFCE-Higher Education Funding Council for England.

- Greenhalgh, T., L. Hinton, T. Finlay, A. Macfarlane, N. Fahy, B. Clyde, and A. Chant. 2019. “Frameworks for Supporting Patient and Public Involvement in Research: Systematic Review and co-design pilot.” Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy 22 (4): 785–801. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12888..

- Greenhalgh, T., G. Robert, F. Macfarlane, P. Bate, and O. Kyriakidou. 2004. “Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations.” The Milbank Quarterly 82 (4): 581–629. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x..

- Gutmann, A., and D. F. Thompson. 2009. Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Harris, Clive, Hodges, John., Schur, Michael. 2003. Infrastructure Projects : A Review of Canceled Private Projects. Viewpoint: Public Policy for the Private Sector. World Bank, Washington, DC. Available: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11329 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. Accessed: 3 June 2021.

- Hodge, G., C. Greve, and A. Boardman. 2017. “Public‐Private Partnerships: The Way They Were and What They Can Become.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 76 (3): 273–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12260.

- Innes, J. E., and D. E. Booher. 2004. “Reframing Public Participation: Strategies for the 21st Century.” Planning Theory & Practice 5 (4): 419–436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935042000293170.

- Innes, J. E., and D. E. Booher. 2003a. “Collaborative Policymaking: Governance through Dialogue.” Deliberative Policy Analysis: Understanding Governance in the Network Society, 33–59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Innes, J. E., and D. E. Booher. 2003b. “Collaborative Policymaking: Governance through Dialogue.” In: Deliberative Policy Analysis: Understanding Governance in the Network Society, edited by H. Wagenaar and M. A. Hajer, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, K. and Bice, S. (2021). “Improving Research Impact: Lessons from the Infrastructure Engagement Excellence Standards.” Evidence and Policy. Early Online Release. 1–29.

- Kothari, A., C. Mccutcheon, and I. D. Graham. 2017. “Defining Integrated Knowledge Translation and Moving Forward: A Response to Recent Commentaries.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 6 (5): 299–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.15..

- Kothari, A., and C. N. Wathen. 2017. “Integrated Knowledge Translation: Digging Deeper, Moving Forward.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 71 (6): 619–623. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-208490.

- Luo, M., L. Guo, M. Yu, W. Jiang, and H. Wang. 2020. “The Psychological and Mental Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) on Medical Staff and General public - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Psychiatry Research 291: 113190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190..

- Mclaughlin, J. A., and G. B. Jordan. 1999. “Logic Models: A Tool for Telling Your Programs Performance Story.” Evaluation and Program Planning 22 (1): 65–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(98)00042-1.

- Mills, T., R. Lawton, and L. Sheard. 2019. “Advancing Complexity Science in Healthcare Research: The Logic of Logic Models.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 19 (1), 55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0701-4.

- Moffat, K., and A. Zhang. 2014. “The Paths to Social Licence to Operate: An Integrative Model Explaining Community Acceptance of Mining.” Resources Policy 39: 61–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2013.11.003.

- Montemurro, N. 2020. “The Emotional Impact of COVID-19: From Medical Staff to Common People.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87: 23–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.032..

- Morgan Jones, M., Grant, J., & RAND, E. (2013). Making the grade: methodologies for assessing and evidencing research impact. In: Dean A, Wykes M, Stevens H (eds.), DESCRIBE: 7 Essays on Impact. Exeter: The University of Exeter.

- Morris, Z. S., S. Wooding, and J. Grant. 2011. “The Answer is 17 Years, What is the Question: Understanding Time Lags in Translational Research.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 104 (12): 510–520. doi:https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180..

- Nabatchi, T., and S. Jo. 2018. “The Future of Public Participation.” Conflict and Collaboration: For Better or Worse, Vol. 75. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nish, S., and S. Bice. 2012. “Participatory Planning and Monitoring in the Extractive Industries.” New Directions in Social Impact Assessment: Conceptual and Method, 59–77. Chelthenham: Edward Elgar.

- Phipps, D., J. Cummins, D. J. Pepler, W. Craig, and S. Cardinal. 2016. “The co-Produced Pathway to Impact Describes Knowledge Mobilization Processes.” Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship 9: 5.

- Stafford, A., and P. Stapleton. 2017. “Examining the Use of Corporate Governance Mechanisms in Public–Private Partnerships: Why Do They Not Deliver Public Accountability?” Australian Journal of Public Administration 76 (3): 378–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12237.

- Tilley, H., L. Ball, and C. Cassidy. 2018. Research Excellence Framework (REF) Impact Toolkit. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Vanclay, F. 2002. “Conceptualising Social Impacts.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 22 (3): 183–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-9255(01)00105-6.

- Watermeyer, R. 2016. “Impact in the REF: Issues and Obstacles.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (2): 199–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.915303.

- White, H. 2010. “A Contribution to Current Debates in Impact Evaluation.” Evaluation 16 (2): 153–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389010361562.

- Zwalf, S., G. Hodge, and Q. Alam. 2017. “Choose Your Own Adventure: Finding a Suitable Discount Rate for Evaluating Value for Money in Public–Private Partnership Proposals.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 76 (3): 301–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12242.

Appendix A

Details of implementation outcomes and processes/activities