Abstract

Impact—what does it mean and how do we know what “counts”? We all want to do work that has an impact, and this is true of all sectors, whether that be government, public, private, not-for-profit, university, education, or community stakeholders. However, understandings of what it means in practice, what it takes to achieve, and how it can be tracked and calculated remain largely unclear and contested. While the rhetoric of “impact” and the “impact agenda” has become popular in the last decade or so, our practice and research appear to be lagging. In this introductory paper to the special issue on Impact into practice: Demonstrating applied public administration and policy improvement we outline how systems thinking approach can aid understanding of research and education impact on government practice. A systems approach reveals where reliance exists, where responsibility falls, and where new and deepened relationships are needed. While more needs to be done by all parties to acknowledge the collective nature of impact and the necessary reliance on one another, we argue that redistribution of responsibility is needed, including the government’s significant role. Without collective recognition of reliance, responsibility, and relationships in the system of impact, our respective endeavors can only be expected to go so far. By thinking about impact as a system, we can end the “blame game” between university and government sectors, and encourage action within and across sectors, in the pursuit of better outcomes for citizens and society.

1. Our journey so far with impact

Whether it be in policy and public administration research, education, or policymaking itself, the perennial and elusive quest that preoccupies modern sensibilities is the quest for impact. How do we know if what we are doing is actually making a positive difference in society? The impact agenda has moved well-beyond outputs and outcomes to now establishing and discussing shifts in behavior, changes to communities, and returns on investment. The impact paradigm is taking over our measurement, benchmarking, and evaluation systems (see Smit and Hessels Citation2021). And why wouldn’t it? It is hard to argue against the admirable desire to monitor the deployment or expenditure of valuable resources to improve the lives and well-being of societies. But there are, of course, a myriad of outcomes, such as changes in academia (see Smith et al. Citation2020; Watermeyer Citation2016; Samuel and Derrick Citation2015), gendered implications (see Chubb and Derrick Citation2020) and the potential for perverse impact-known as “grimpact” (Derrick et al. Citation2018). What we have noticed is that the topic of impact, as with all fads and fashions, demands attention be paid to definitions, competing objectives, measurement challenges, opportunities, and consequences.

At the outset, we want to note how this body of work and the special issue came about. It emerged from a lived experience of navigating the fields of research, policy, and education to improve public management theory and practice to achieve better outcomes for citizens. The special issue editors all work at the intersection of these fields and have experienced increased calls to demonstrate impact into practice. To try and make sense and help navigate the many complexities of impact for those working with and for government, this special issue focuses on the impact agenda that is continuing to sweep many countries and jurisdictions around the globe. In policy and public administration fields, the impact is often used as a tool to assess and evaluate resource allocation, increasingly occurring amidst scarcity, uncertainty, and compressed timeframes. As one of the articles in this special issue defines it, the impact is: “…a means of understanding consequences of a policy or intervention” (see Esteves et al. Citation2012 ) or post-hoc “the final level of the causal chain.” Meanwhile, the impacts of COVID-19 have decimated the higher education sectors in many countries, further pressurizing schools of policy or public administration to better demonstrate the impact of education and scholarship into government practice.

A workshop was held in Canberra in December 2019, co-hosted by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG), the Public Service Research Group (PSRG) at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Canberra, the Australian National University (ANU) Crawford School, and the Analysis & Policy Observatory (APO). The workshop identified impact in policy and public administration fields as pertinent across research, teaching, and practice, yet debates are siloed and fragmented across these spheres. The workshop was held with invited participants from across government, university, education providers, and the not-for-profit sectors. The purpose was to bring together sectors who often appear to have different understandings and incentives for what impact means and what it takes to generate it with those who appear to talk across, rather than necessarily to, one another when it comes to impact identification and assessment. Thanks to Policy Design and Practice, this special issue serves as a way to progress our collective thinking and action in an informed but accessible way.

In this introductory article, we map the impetus for impact—both intellectual and practical—based on our learnings from the workshop and work since. We argue two important points. First, that societal impact is a relational phenomenon embedded in a broader and more intricate, complex, and dynamic system, rather than the final stages in a singular, detached causal chain. As such, all parties to any impact relationship must take responsibility for success or failure and all parties have cause to celebrate when things go well. Second, that higher education providers forget the story of education impact at their peril. While research has been the “main game” of the impact agenda to date, there is an imperative to track education impact. To ignore this contribution risks universities severely undercutting their role in policy and public administration.

2. Why a focus on education and research?

We acknowledge that there are many different ways to think about what impact is and means, and what contributes to it. In this special issue, we have tried to narrow our focus to the impact of research and education on public sector practice. This is a deliberate choice, primarily because the two areas are sometimes perceived as disconnected or that the world of education does not have the same impact potential as scholarly research. From our perspective, however, university research and education are both keys to public sector impact. To ignore one over another imperils the academic endeavor to promote effective policy and public administration practice.

The total dollar value of the higher education sector in global terms is significant. Fortune Business (Citation2020) indicates that the global market size of higher education is USD 1090.87 billion in 2019 and is projected to grow to USD 2367.51 billion by 2027. The increasing proliferation of online teaching approaches is propelling growth. Marinoni et al.’s (Citation2020) study of the impact of COVID-19 on the global higher education sector indicated that the effects were equal, if not worse, for the education component of higher education institutions compared with research. A total transformation of education is happening as a result of the pandemic. While this offers opportunities as well as setbacks, it is important to acknowledge the key role that education holds for economic development and national wealth. While universities have focused their stories of impact on knowledge creation brought by research, mainly in response to regulatory requirements from governments, this story ignores the vital role that teaching and learning play for not only knowledge dissemination but also knowledge creation.

Education not only demands the communication and grasp of content, but it also entails a rewarding process of continuous interaction and exploration of research, a process that can spur new knowledge creation itself (see e.g. Rosowsky Citation2020). Furthermore, the knowledge dissemination endeavor is an applied phenomenon—one that can shift and change public administration and policy practice in its own right. Action learning-applied projects in the virtual or physical classroom, the take-up of ideas, and their application into workplaces and policy challenges are all examples where the education side of the higher education sector ledger can make a massive difference to policy and public administration practice. Higher education institutions train and educate the direct architects of policy and public administration—the politicians, the public servants, the think tank operatives, and so on. But they also, very importantly, train the citizenry itself in terms of both civics, as contributors to co-production and co-design agents, and as general agents in the world contributing to all aspects of society (see Domingues-Gόmez, Pinto, and González-Gόmez Citation2021).

Higher education institutions assist the labor market, but also contribute to social change, civic cohesion and reflection, regional and community development, and knowledge innovation. When viewed in this light, the contribution of education to the impact agenda is remarkably influential. Tracking its contribution is harder to establish not least because of the general lack of energy devoted to collecting data pertinent to the causal relation between knowledge dissemination and value creation activities. Education and training are often taken for granted, and neglected in favor of ideas creation and commercial and social innovations. Similar to how the social glue and unpaid contributions of communities are leveraged by government and assumed to be a free and readily available resource for the functioning of society, so too are the deeper and wider contributions of education to the social, economic, and political well-being of society. The impact agenda throws into relief the fact that education and training could arguably be undervalued similarly to the global unpaid economy with respect to its contributions. For sure, it is a story that higher education institutions ought to tell. For us, the impact agenda does not just rest on research but on the integrated endeavors of both research and education.

Here, we define public sector impact widely, as pertaining to the way that it works and what influences it has and can have on individuals and the functioning and well-being of society. Our focus is on understanding why the value of policy research and education for public sector practice appears to be under-recognized, how it can be better understood, and what methods and practices can be used to better document and generate the impact of each. In this special issue introductory paper we begin by sketching the history of the divide, before outlining why a system thinking approach is needed to better understand the role and responsibilities of different stakeholders required for successful public sector impact pathways.

2.1. A history of pulling apart

The fields of public administration and policy have always been concerned with impact in terms of the practical implications of policy and administration on society. Close interconnections between practitioners and scholars propelled this focus in both fields from their inception. Institutional demands and process linkages, however, have diverged over time. Scholars were, and arguably still are, largely incentivized to be preoccupied with publishing in top-tier journals. Simultaneously, practitioners have become skeptical of the relevance of scholarship and training and have questioned its value for money amidst pressing resource constraints and increased scarcity. A decoupling of those engaged in knowledge production and communication from those responsible for implementing and enacting knowledge into action started to occur post-WWII but has become more pronounced since the 1990s (see Threlfall and Althaus Citation2021).

Efforts over the past few decades have attempted to boost the academic side of the ledger, to swing scholarship, education, and training toward public administration and policy practice. Yet the underpinning institutional incentives of the university sector and the academy remain buttressed on producing research recognized for its publication in highly ranked journals and achieving prestigious university ratings. We see this with the attention, emphasis, and prestige given to annual university rankings by renowned benchmarking outlets (e.g. rankings by QS Rankings 2021, Times Higher Education 2020). Many government actors remain unsophisticated in their understandings of research endeavors and the potential they have to elicit practical contributions, especially within time-compressed policymaking environments. Meanwhile, the impact of policy and public administration education and training does not appear to feature strongly, if at all, in the calculus of either academy or government impact, despite investment in schools of government and a plethora of training programs.

Our purpose here based on our experience in practice is to try to bring together these sectors and advocate for systems thinking approach that enables better understandings of what it takes, and where responsibility lies, for generating impact into public sector practice.

3. Why “public sector impact”

Drawing on the work of Mark Moore, “public sector impact” can be seen as an umbrella term for multiple forms of outcomes and conceptions of the impact that were raised at the 2019 workshop, such as “policy impact,” “programme impact,” “research impact,” “leadership impact,” and “education and training impact,” among others, that generate public value in their own right at a particular point in time, but also feed into what it takes to create broader public value over the longer term. Foregrounding public value in our understanding of public sector impact helps to orient the focus of impact on citizens (see Moore Citation1995, Citation2013, Citation2017). At its simplest, public value refers to the value created by the government through services, laws, regulations, and other actions, beyond purely monetary (see Katsonis Citation2019). As a technical idea, Moore (Citation2013) developed the “strategic triangle” for public managers to use to better understand and measure what “value” is added by any given policy, programme, or agency.

This anchor of public value helps bring into focus how understandings of “impact” are different for the public sector compared to the private sector by drawing attention to the different outcomes and impacts (good, bad, or otherwise) that citizens and society at large experience. At the outset, we wish to caution against a focus on developing ways that seek only to capture the “good”; rather we wish to work toward more robust processes for capturing impact, irrespective of whether the outcome is perceived to be good, bad, or otherwise. This comes from a belief that a lot can be learned from failure as well as from success. A focus on public sector impact is distinctive because of the nature of the work and responsibility that is held by those who work within and alongside the public sector. Seen in this light, public value is more extensive and focused on how it is consumed collectively and in the interests of the common good, as opposed to private value, which is primarily driven by self-interest and consumed individually (see ANZSOG Citation2017).

4. Why a system thinking approach is needed

The growing consensus in the literature indicates that the systems thinking approach has a lot to offer the impact agenda, just as it does across higher education (Furst-Bowe Citation2011) and other areas, such as health promotion (see Haynes et al. 2020; Zurcher, Jensen, and Mansfield Citation2018). This is primarily because thinking about impact as a system helps illuminate the different stakeholders involved. General systems theory originated in the 1940s in the field of biology as an alternative to the dominant form of reductionist inquiry and way of thinking, which was criticized for its inability to address wholes, interdependence, and complexity (Montuori 2011). It provided a new way of thinking that allows for the study of interconnections among systems and accounts for the nature of “open systems” which interact with their environments (Montuori 2011). Others have written about systems thinking in the field of public administration and how it forces a “reconsideration of individualized incentives and support for collective action solutions and partnerships” (see Gardner et al. Citation2019, 4; Senge 1991).

By focusing on connections, systems thinking reframes how problems are understood and addressed, and how people and resources are engaged in such processes (Gardner et al. Citation2019, 5). While there are different approaches to systems thinking and it remains a rather loose collection of analytical perspectives, there are consistent themes in connection, shared responsibility, and the importance of context (Gardner et al. Citation2019, 5). By exploring the connections between elements, and giving the connections equal status to elements, systems thinking focuses on understanding the inter-relationships, interactions, and system boundaries that give rise to, and at the same time constrain or enable, possibilities for action and change (see Abercrombie, Harries, and Wharton Citation2015; Johnston, Matteson, and Finegood Citation2014 in Gardner et al. Citation2019, 5).

This is a helpful approach in practice for better understanding how impact occurs and where responsibility lies. The impact is more than simply outputs and outcomes, rather it is a whole system of connections and relationships that make up an “impact pathway.” At present, as details, most understandings of education and research impact assume a one-way pathway entailing a linear chain of sequential events leading to impact.

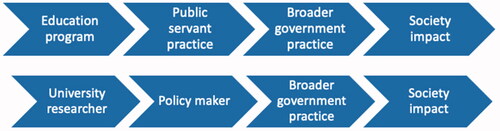

In practice, this type of linear and sequential thinking has largely informed perceptions of where responsibility (and fault) lies for impact. We argue that this type of thinking is too simplistic and that such perceptions have contributed to a divide and arguably a “blame game” (see e.g. Hood Citation2010) between different stakeholders, with the government repeatedly asserting that education and research input misses the mark when it comes to practical applicability. In practice, the onus has fallen primarily on the academy to demonstrate and prove why their work is of value and a worthy endeavor (Mitchell Citation2019; Peseta, Barrie, and McLean Citation2017), along with the sole responsibility to develop connections and build relationships with policymakers and public servants, rather than the reverse. We argue that a more equitable distribution of responsibility is needed, shifting from a system where educators and researchers bear the brunt of the responsibility to one where there is a more proportionate distribution of responsibility across all stakeholders attuned to their sphere of influence and control. For instance, using as an example, rather than the bulk of responsibility falling on the “education program” or “university researcher,” responsibility also lies with public servants and policymakers, and those in government more broadly, for supporting and enabling impact into practice. This comes from the recognition that educators and researchers can only do so much within their sphere of influence, and have only so much control within the structures and incentive systems they have to work within and that responsibility must be taken and accountability measures developed to ensure that other stakeholders are equally playing their part. Research can only do so much if it is not used or applied. Education and training can only go so far until it is allowed to be put into action.

Put simply, we recommend understanding impact as a system to help identify who the different stakeholders are in any type of impact pathway and where responsibility lies given the different spheres of influence and control of each. Understanding impact as a system requires all parties involved to move beyond anyone stakeholder’s sphere of influence and responsibility, toward recognizing the necessary reliance on others in the system that bears responsibility for facilitating and enabling education and research impact into practice. Seen in this light, individual policymakers, government agencies, and alike are not passive stakeholders, rather they are active parties in the system, and as such their responsibility and sphere of influence and control for enabling (or blocking) impact into practice needs to be recognized. Relationships are fundamental to how this can occur in practice, and we now turn to them in more detail.

5. Why relationships are key

Relationships are key to impact (see Cairney and Oliver Citation2020). In the systems thinking approach to impact, as details, rather than a one-way linear approach, stakeholders overlap and are reliant on one another to generate and enable impact. This is represented in the figure by the circular black lines that are interwoven between all three stakeholders in this example. Along these lines are triangles that signify impact enablers, such as key people or events in any given impact pathway. It is these lines of relationships and enablers that are key to ensuring and maximizing impact, which has huge implications for the extent to which public value can be achieved.

How to cultivate and maintain relationships is central and demands more nuanced attention.

Approaches that acknowledge the shared enterprise of theory building and improving practice, such as co-design and collaboration have long been advocated for (see Threlfall and Althaus Citation2021, 43; Sullivan Citation2019; Sullivan et al. Citation2013; Sullivan and Skelcher Citation2002). Doing so requires both formal and informal collaborative links and relationships that necessitate negotiation and compromise, particularly if those relationships are to be sustainable over time (Sullivan Citation2019, 320). Regarding engagement, Sullivan (Citation2019) has warned against interventions that proceed with an assumption that all parties have a shared sense of purpose; they are likely to fail to achieve their goals. Instead, clear communication between policymakers and academic contributors is essential, especially in interventions led by policymakers (Sullivan Citation2019, 320). The next question becomes how to help ensure that this type of communication occurs. For this to happen, it is important to have “navigators” and “boundary workers”—people on both sides of the so-called policy/academic divide who can traverse the boundaries between policy and academia and “act as interpreters and wayfinders” (Sullivan Citation2019, 321).

In practice, a system thinking approach to impact helps identify where reliance exists, where responsibility lies, and why relationships are key. As we know from the public administration and management literature, collaboration produces many different types of actions and outcomes with the attention needed at the micro-level, beyond “techno-bureaucratic performances” that are privileged in public policy and public management (Dickinson and Sullivan Citation2014, 172). What is needed in practice is fairer recognition and distribution of responsibility for supporting and ensuring impact into practice. Using the example of , while responsibility and criticism have largely been pointed at the university part of the system, much more is needed from the government to play their significant part. While universities can do their utmost to meet various “engagement” targets and develop research translation strategies, if the government does not take a more active role in valuing and making sure that pathways and processes for impact exist and are encouraged, then any pathway, irrespective of its development strength and intentions, can only be expected to achieve so much. If governments use impact as a punitive tool, wielded to punish the academy for irrelevance, wastefulness, or non-performance, they do so at the peril of ignoring their own role in generating and achieving impact for society as a whole. While universities focus on rankings and scholars seem intent on trying to define and demonstrate their impact on the policymaking endeavor, it is not clear whether governments know what they want in terms of impact or how much of an incentive instrument they want the impact to be. Questions remain about the purpose of tracking impact and whether it is possible to move toward satisfying multiple impacts aims simultaneously. While questions abound, what everyone agrees from our focus on impact is its relational aspect. That is, the impact is—at the very least—a two-way dance between the academy and government.

6. Special issue focus on bringing together—reliance, responsibility, and relationships

Bringing the academy and government closer together, recognizing they form key parts of the impact system with associated roles and responsibilities, will enable better understandings of what it takes to generate impact into practice. Each of the papers in this special issue reveals different aspects of reliance, responsibility, and relationships required for impact.

A range of authors is featured, with topics and cases from across the Pacific, the United Kingdom, Australia, and North America. Mainstream and Indigenous perspectives are offered. Papers range across the policymaking literature as well as into the research-practice dichotomy, along with some discussion about the contribution of education as part of the policymaking endeavor. The papers share an interest in impact defined as the influence of research and education on policy and public management practice. The emergent insights embrace reliance, responsibility, and relationships in different ways.

Carson and Given set the scene, describing a rich landscape of how to conceive of impact in policy and public administration. They describe the impact as a nested, multidimensional puzzle and outline what yet is to be pieced together with respect to our understanding and sense-making of the challenges posed by this puzzle and the pieces within it. They develop a series of sense-making questions designed to prompt further discussion and clarity as a way to help bring relevant sectors together by recognizing their interdependence and how each forms crucial parts of what it takes to generate impact into practice.

Hopkins et al. focus on engagement between research and policymaking, giving practical advice and detailing seven challenges to strong and healthy linkages, alongside recommendations to help overcome them. Based on an analysis of 346 organizations, they describe at least three ways in which engagement is framed: (i) linear; (ii) relational; and (iii) systems, each of which involves diverse assumptions and causal pathways. Among the seven challenges they detail, responsibility and relationships are particularly important in understanding the purpose of engagement, who it is for, the likelihood of success given complex policymaking systems, and “how far” researchers should realistically be expected to go to achieve it. They find that that in general, there is a relative overinvestment in the “push” activity, such as training and skills activities for helping researchers take their work forward, rather than addressing policy agendas and clearer relational practices for what collaboration, co-design, and co-production mean in practice (Hopkins et al. Citation2021, 15).

Barbara et al. build off the challenges posed by Hopkins et al. by rejecting the assumptions of a group of “heroic” individual academics transforming the impact agenda. They demonstrate how institutions and organizations matter and suggest that organizational structure is an impact mechanism that drives incentives just as much as journal impact factors drive publication aspirations. Barbara et al. present a case study and stress impact as a collective endeavor, one where the structure and function of research units and accessibility must be considered as an important driver of benefit. Their analysis highlights how the organizational structure of research production and dissemination needs to be considered as part of the impact system as an important element to what it takes to generate impact into practice.

Fotheringham, Gorter, and Badenhorst suggest that impact is more than being policy-relevant; it includes developing policy through deep and long-term engagement between policy and research communities. Using the example of the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), they describe a “Policy Development Research Model” that integrates “the traditionally separate processes of evidence building and policy development” into one set of coherent practices. Fundamental to the success of the research model is the longstanding relationship as a trusted advisor and a strong engagement with policy advisors, among other aspects, all of which enable a deep two-way knowledge transfer and ultimately enhances policy impact.

Meanwhile, Jones and Bice argue the case for joining up the “what” and “how” of impact, proposing a logic model pathway that embraces consideration of impact across policy design, implementation, and preemptive evaluation stages. Scholars, they argue, are concerned not only with how their research advances practice, but also that it is impactful in its own right. The impact extends the usual logic model beyond inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes to also include these two forces of impact themselves. They do this using a case study of a major infrastructure project and the example of a major road tunnel. They state: “The completion of the tunnel is an output that achieves the outcome of greater road traffic capacity that has the impact of improving users” well-being through reduced stress from gridlock” (Jones and Bice Citation2021, 3 emphasis in original). Linking back to our argument for systems thinking approach to impact, Jones and Bice highlight how the impact of research spans the entire policymaking chain, including the academic goal to promote practical action as well as theory development. Picking up on aspects of relationality, their approach foregrounds the relationship with the community for policy impact that includes “empathy mapping.” They argue that for “genuine and robust research” co-design, researchers need to commit not only to researching with rigor but also must have a willingness to dedicate thought and effort to “the how” of impact—that is, the relationship between what research activities are carried out and how those processes can simultaneously advance policy and practice impact.

Ritchie then offers a set of arguments that propose a complete overturning of the paradigm of knowledge, policy design, and impact. Linking back to our systems thinking approach to impact, Ritchie’s analysis promotes reflection on “impact” as a white western endeavor. Using Indigenous affairs as an example of enduring impact failure, Ritchie shows how important the starting premises are with respect to knowledge and design that flow through to positive outcomes, or lack thereof. Whereas the other papers highlight areas to perfect the techniques or understandings of impact in the mainstream conception of policymaking and academia, Ritchie proposes that this mainstream system is flawed for certain parts and members of the community. Understanding the knowledge and relationships of the peoples and places which policy seeks to influence is absolutely critical to the policy process, yet too often it is assumed a universal solution will be applicable, achievable, and desirable. Instead, Ritchie argues for the application of the particular, the local, the metis.

Orr takes another route on Indigenous affairs and impact. Using a legal ruling from Oklahoma and its implications for state jurisdiction and Native American Indian sovereignty, he illustrates how diverse perspectives of impact are brought into focus far beyond the usual scholar-practitioner dichotomy to include a divergence within and amongst traditionally entwined researchers, tribal officials, and activists. Linking back to systems thinking approach to impact, the Oklahoma case showcases the contested nature of relationships and developments in any given impact pathway. For example, what is powerful in Orr’s analysis is how allies who are traditionally bound by common ideological goals can diverge dramatically with respect to how to enact and give effect to the impact of policy decisions. For some, every single policy is an impact battleground. For others, battles are fought within the context of a longer-term war. Impact is not only contestable but fraught with levels of complexity that push the boundaries of Jones and Bice’s impact pathways into multidimensional and intergenerational realms. Although related to Ritchie’s quest to take into account and pay respect to the knowledge and insights of the local, Orr brings us back to the interface between multiple actors with respect to impact and its calculation within the current paradigm.

Collectively, the papers in this special issue point to the importance of relationships in developing and sustaining impact across both education and academic-government engagement. As with all relationships, we are not blind to the contestation and potential ruptures that can and do occur. They involve ongoing push and pull, the need for continuous and clear communication, and a sense of shared connection regardless of whether the initial relationship was entered into willingly or not. If we treat impact as a purely transactional process, its potential will be constrained. A system and relational approach brings assumptions to the surface, throws incentives into relief, and stresses the multi-dimensional ways in which impact can be assessed and improved.

The papers in this special issue show a need to better understand the impact as a system, with different configurations of what works for whom, how it works, why it works, and what the benefits are. Better and more nuanced understandings of what works in practice are not only needed for those directly “invested,” but also need to be considered across multiple dimensions to better understand the wider public value these endeavors generate for the greater functioning of governments and outcomes for its citizens over time. The ultimate point behind impact is to draw attention to improvements for the communities and societies that governments and universities serve.

We bring a political lens to impact discussions by focusing on power and inherent tensions and opportunities afforded by relationships within a broader system. There remains much to do in this area. We support an inclusive approach and are bringing deliberate racial attention into the conversations by including Indigenous perspectives. But others are right to point out gendered ideas of impact (see e.g. Bacchi and Eveline Citation2010) and to raise the need for embracing the perspectives of all into the impact agenda, including not only the perspectives of people but also those of place (see e.g. Barrett, Watene, and McNicholas Citation2020). Mariana Mazzucato’s (Citation2017) work on value reminds us that a diverse range of perspectives over history can be attributed to the definition of value: it has variously been conceptualized as referring to value creation, value extraction, and value fabrication. In the same way, the story of impact is susceptible to significant change, depending on how it is being defined and by whom. Impact—just like value—can morph and slide into very distinct and different concepts, depending on the eye of the beholder and the wielder of the scribe or sword-holder who is defining impact in the first place.

We hope this special issue goes some way in spurring conversations and actions that are needed on all sides to ensure a collective and concerted impact system, one that with better recognition of reliance, responsibility, and relationships can be advanced to create greater public value—and better recognition of it—for the betterment of society, now and into the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Abercrombie, R., E. Harries, and R. Wharton. 2015. Systems Change: A Guide To What It Is and How To Do It. Lankelly Chase, New Philanthropy Capital (NP C) https://lankellychase.org.uk/resources/publications/systemschange-a-guide-to-what-it-is-and-how-to-do-it/

- ANZSOG. 2017. What is Public Value? Public Admin Explainer. Melbourne: ANZSOG. Accessed 13 May 2021. https://www.anzsog.edu.au/resource-library/research/what-is-public-value

- Bacchi, C., and Eveline, J., eds. 2010. Mainstreaming Politics: Gendering Practices and Feminist Theory. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press.

- Barrett, M., K. Watene, and P. McNicholas. 2020. “Legal Personality in Aotearoa New Zealand: An Example of Integrated Thinking on Sustainable Development.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 33 (7): 1705–1730. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2019-3819.

- Cairney, P., and K. Oliver. 2020. “How Should Academics Engage in Policymaking to Achieve Impact?” Political Studies Review 18 (2): 217–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918807714.

- Chubb, J., and G. Derrick. 2020. “The Impact a-Gender: Gendered Orientations towards Research Impact and Its Evaluation.” Palgrave Communications 6 (72): 1–11.

- Derrick, G. E., R. Faria, P. Benneworth, D. B. Pedersen, and G. Sivertsen. 2018. “Towards Characterising Negative Impact: Introducing Grimpact.” Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on science and technology indicators: science, technology and innovation indicators in transition (Vol. 2018-09-11, pp. 1199–1213). Leiden University, CWTS. Accessed 6 August 2021. http://hdl.handle.net/1887/65230

- Dickinson, H., and H. Sullivan. 2014. “Towards a General Theory of Collaborative Performance: The Importance of Efficacy and Agency.” Public Administration 92 (1): 161–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12048.

- Domingues-Gόmez, J. A., H. Pinto, and T. González-Gόmez. 2021. “The Social Role of the University Today: From Institutional Prestige to Ethical Positioning.” In Universities and Entrepreneurship: Meeting the Educational and Social Challenges (Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research, Vol. 11), P. Jones, N. Apostolopoulos, A. Kakouris, C. Moon, V. Ratten, and A. Walmsley, 167–182. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Esteves, A. M., D. Franks, and F. Vanclay. 2012. “Social Impact Assessment: The State of the Art.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30 (1): 34–42. 660356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2012.

- Fortune Business. 2020. “Higher Education Market Size, Trends, Research Analysis, 2027.” Accessed 31 May 2021. https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/higher-education-market-104503

- Furst-Bowe, J. 2011. “Systems Thinking: Critical to Quality Improvement in Higher Education.” Quality Approaches in Higher Education 2 (2): 1–4.

- Gardner, K., S. Olney, L. Craven, and D. Blackman. 2019. How Can Systems Thinking Enhance Stewardship of Public Services? Discussion Paper, Public Service Research Group, UNSW Canberra.

- Haynes, A., L. Rychetnik, D. Finegood, M. Irving, L. Freebairn, and P. Hawe. 2020. “Applying Systems Thinking to Knowledge Mobilisation in Public Health.” Health Research Policy and Systems 18 (1): 119–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00600-1.

- Hood, C. 2010. The Blame Game: Spin, Bureaucracy, and Self Preservation in Government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hopkins, A., K. Oliver, A. Boaz, S. Guillot-Wright, and P. Cairney. 2021. “Are Research-Policy Engagement Activities Informed by Policy Theory and Evidence? 7 Challenges to the UK Impact Agenda.” Policy Design and Practice : 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1921373.

- Jones, K., and S. Bice. 2021. “Research for Impact: three Keys for Research Implementation.” Policy Design and Practice : 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1936761.

- Johnston, L., C. Matteson, and D. Finegood. 2014. “Systems Science and Obesity Policy: A Novel Framework for Analyzing and Rethinking Population-Level Planning.” American Journal of Public Health 104 (7): 1270–1278. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301884.

- Katsonis, M. 2019. “How Do we Measure Public Value?” The Bridge, ANZSOG. Accessed 30 March 2021. https://www.anzsog.edu.au/resource-library/research/how-do-we-measure-public-value

- Marinoni, G., H. V. Land, and T. Jensen. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on higher education around the world. International Association of Universities. Accessed March 30th 2021, available from https://www.iauaiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_and_he_survey_report_final_may_2020.pdf

- Mazzucato, M. 2017. The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Mitchell, V. 2019. “A Proposed Framework and Tool for Non-Economic Research Impact Measurement.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (4): 819–832. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1590319.

- Montuori, A. 2011. “Systems Approach.” In Encyclopaedia of Creativity. 2nd ed., edited by Mark A. Runcso and Steven R. Pritzker, Elsevier, 414–421.

- Moore, M. 1995. Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: Harvard University Press.

- Moore, M. 2013. Recognising Public Value. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Moore, M. 2017. Public value: A quick overview of a complex idea. Presentation to Department of the Prime Minister & Cabinet, New Zealand. Accessed 30 March 2021. https://dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2017-07/public%20value%20-%20mark%20moore%20presentation.pdf

- Peseta, T., S. C. Barrie, and J. McLean. 2017. “Academic Life in the Measured University: pleasures, Paradoxes and Politics.” Higher Education Research & Development 36 (3): 453–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1293909.

- QS University Rankings. 2021. The World’s Top 100 Universities, April 9. Accessed 30 March 2021. https://www.topuniversities.com/student-info/choosing-university/worlds-top-100-universities

- Rosowsky, D. 2020. The Teaching and Research Balancing Act: Are Universities Teetering? Forbes, June 11.

- Samuel, G., and G. Derrick. 2015. “Societal Impact Evaluation: Exploring Evaluator Perceptions of the Characterization of Impact under the REF2014.” Research Evaluation 24 (3): 229–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv007.

- Senge, P. 1991. “The Fifth Discipline, the Art and Practice of the Learning Organization.” Review Canadian Public Administration 34 (4): 682–684.

- Smit, J., and L. Hessels. 2021. “The Production of Scientific and Societal Value in Research Evaluation: A Review of Societal Impact Assessment Methods.” Research Evaluation 1–13.

- Smith, K., J. Bandola-Gill, N. Meer, E. Stewart, and R. Watermeyer. 2020. The Impact Agenda: Controversies, Consequences and Challenges. Policy Press.

- Sullivan, H. 2019. “Building a Knowledge-Sharing System: Innovation, Replication, Co-production and trust–A Response.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 79: 319–321.

- Sullivan, H., and C. Skelcher. 2002. Working across Boundaries: Collaboration in Public Services. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sullivan, H., P. Williams, M. Marchington, and L. Knight. 2013. “Collaborative Futures: Discursive Realignments in Austere Times.” Public Money & Management 33 (2): 123–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2013.763424.

- Threlfall, D., and C. Althaus. 2021. “A Quixotic Quest? Making Theory Speak to Practice.” In Learning Policy, Doing Policy: Interactions between Public Policy Theory, Practice and Teaching, edited by T. Mercer, R. Ayres, B. Head, and J. Wanna, 29–48. ANU Press: Canberra, ACT, Australia.

- Times Higher Education Rankings. 2020. The top 50 universities by reputation, November 3. Accessed 30 March 2021. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/best-universities/top-50-universities-reputation

- Watermeyer, R. 2016. “Impact in the REF: issues and Obstacles.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (2): 199–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.915303.

- Zurcher, K. A., J. Jensen, and A. Mansfield. 2018. “Using a Systems Approach to Achieve Impact and Sustain Results.” Health Promotion Practice 19 (1_suppl): 15S–23S. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839918784299.