Abstract

In contrast to its Assessment Reports, less is known about the social science processes through which the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produces methodologies for greenhouse gas emissions reporting. This limited attention is problematic, as these greenhouse gas inventories are critical components for identifying, justifying, and adjudicating national-level mitigation commitments. We begin to fill this gap by descriptively assessing, drawing on data triangulation that incorporates ecological and political analysis, the historical process for developing emissions guidelines. Our systematic descriptive efforts highlight processes and structures through which inventories might become disconnected from the latest peer-reviewed environmental science. To illustrate this disconnect, we describe the IPCC guideline process, outlining themes that may contribute to discrepancies, such as diverging logics and timeframes, discursive power, procedural lock-in, resource constraints, organizational interests, and complexity. The themes reflect challenges to greenhouse gas inventories themselves, as well as broader challenges to integrating climate change science and policy.

This article provides an illustrative analysis of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s greenhouse gas inventory guideline process

There is evidence for substantive discrepancies between empirical literature and these guidelines

Particularly for forest soil organic carbon reporting, inventory guidelines are influenced by a multitude of political and scientific actors

Explanations for these discrepancies merit further inquiry, and include institutional lock-in, political influence, discursive power, resource constraints, and world views

Highlights

1. Introduction

Reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is crucial to minimizing the harms of climate change on people and communities (Seto et al. Citation2016; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Citation2015a). The ways we measure and report GHGs—as well as the scientific institutions developing the methods to do so—play an important role in environmental policymaking. While the natural sciences have given these issues extensive attention (Pulles Citation2017, Citation2018), the social and policy sciences—in contrast to their efforts in studying, and participating in, IPCC climate change assessment reports—have placed significantly less attention on studying GHG reporting methodology processes. Yet, GHG inventories (GHGIs) are critical for identifying and adjudicating national-level mitigation efforts, including commitments under the United Nations Paris Agreement. As a result, less is known about the institutional, policy, and political influences on the development of GHGI guidelines, hampering the type of interdisciplinary collaborations required for understanding, and helping improve, the science-policy interface.

This article begins to fill this gap in three ways: describing historical and contemporary protocols through which GHGI guidelines have been developed; identifying key themes that emerge, in particular the tendency for guidelines to differ from the best-available peer reviewed science; and generating key explanatory hypotheses with which to guide future research. To accomplish these tasks, we focus specifically on the procedures and protocols governing how the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) develops and updates their guidelines for GHGI reporting (“IPCC guidelines”), with a focus on forest soil organic carbon, since it is a sector where discrepancies between empirical data and IPCC guidelines are particularly pronounced, with policy implications. Our study addresses the following questions: how were the IPCC guidelines developed? What may have caused discrepancies between the guidelines and empirical research on forest soil organic carbon reporting? This research requires attention to both the formal rules and operating procedures, but also the unwritten norms that shape micro- and macro-level protocols. This descriptive analysis sets a foundation for explanatory and prescriptive analysis. To facilitate the latter, we identify potential themes to guide future research, centering gaps between the best available peer-reviewed ecological science and the scientific knowledge upon which current guidelines are based. Hence, we aim to both describe IPCC GHGI guideline processes and, in so doing, highlight challenges facing interdisciplinary researchers and practitioners to produce accurate and effective GHGIs that are in line with robust evidence.

We study guidelines that have been developed, and refined, to measure forest soil organic carbon, given that a complete assessment is beyond the scope of a single article. We find that in the case of forest soil organic carbon, IPCC guidelines are not aligned with the best available science. Specifically, there is a disconnect between inventory guidelines and more recent peer-reviewed literature. For example, the most accessible class of guidelines—known as “Tier 1”—refers to measures and responses of forest soil organic carbon stocks that differ from more recent research (Liao et al. Citation2010). Instead, they draw on assumed management impacts, and carbon values using biome and soil classes that have not been updated since they were first produced in 2006 (National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme Citation2006; Jamsranjav Citation2017; IPCC Citation2019). To illustrate just one example of how the guidelines can impact policy (more in Section 2.5), for boreal wetland soils, forest soil organic carbon stocks can be estimated anywhere between 14.6 and 277.4 tonnes of carbon per hectare (National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme Citation2006). Because Tier 1 approaches are often used by countries to report GHGIs, ensuring that they are up to date is important for effective climate mitigation. To date, every country relies on Tier 1 guidelines for at least one component of their inventories (Research interviews). Understanding the differences between the IPCC guidelines and scientific knowledge requires interdisciplinary collaborations, as we must first map the differences between peer-reviewed scientific research and guidelines; understand the policy and institutional protocols that may have enabled this research-guideline gap; and suggest future research and strategies for better, and swiftly, linking ecological knowledge into IPCC guidelines.

Undertaking an interdisciplinary policy study of GHGIs, we advance the findings that climate science policy research has contributed to questions of evidence-based policy, including literature examining IPCC assessment processes (Silke Beck and Mahony Citation2018; Livingston and Rummukainen Citation2020; Skodvin Citation2000), as well as accounting in the land use sector (Gupta et al. Citation2012; Turnhout et al. Citation2017). This existing literature highlights some of the challenges to incorporating complex ecological research for policymaking, providing assessments of both disconnects between science and policy (Dilling and Lemos Citation2011; Turnhout et al. Citation2020), as well as recommendations moving forward (Adler and Haas Citation1992; Biermann et al. Citation2012; Maas et al. Citation2021; Yona, Cashore, and Schmitz Citation2019). Hence, we draw on, contribute to, and expand, this literature’s insights through specific attention to the processes through which GHGI guidelines are produced, and implications for the politics and policies of country-level climate commitments.

Our study is also situated within the context of prior literature on GHG metrics and the institutional forces driving them, recognizing that accounting metrics may, depending on their design, have “the capacity to shape society itself” (Lovell et al. Citation2010). Climate mitigation is grounded in “the ability to systematically quantify carbon emissions” (Whitington Citation2016), and the IPCC has historically set those metrics through the GHGI guidelines it produces. While other GHG accounting approaches exist outside of international negotiations, such as those reflecting the priorities of business interests (World Business Council for Sustainable Development and World Resources Institute Citation2004), the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) relies on the IPCC approach to assess countries’ progress toward their emissions reductions pledges (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Citation2015a; Yona et al. Citation2020). But these metrics may pose problems when their values and responses are not aligned with the latest peer-reviewed science. Indeed, the implications of GHGI metrics differing from actual GHG emissions are evident: studies have found discrepancies between measured GHG emissions and those reported in GHGIs in the Canadian bitumen sector (Liggio et al. Citation2019), in the United States natural gas sector (Rutherford et al. Citation2021), and in corporate reporting (Klaaßen and Stoll Citation2021), all of which are industries that substantially contribute to global GHG emissions. GHGI metrics, and the path dependencies they trigger, can lead to an unintended “GHG accounting gap” that may be consequential to global climate action.

2. Background

2.1. Existing intergovernmental science-policy interfaces

An extensive body of science-policy research has studied how intergovernmental bodies are able to draw on and use science to achieve their goals. Environmental assessment, the process of examining science and its usability (or misuse) for environmental policy (Mach and Field Citation2017; Hallegatte and Mach Citation2016), is central to this interface. Much of science-policy scholarship has focused on IPCC’s Working Groups, which are charged with producing regularly scheduled assessments and special reports on the science of climate change (Shaw and Robinson Citation2004; Livingston and Rummukainen Citation2020; Hulme and Mahony Citation2010). Other literature studies the ways in which the IPCC interacts with UNFCCC processes (Devès et al. Citation2017; Kornek et al. Citation2020). Similarly, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has sought to synthesize biodiversity science for policy, incorporating indigenous knowledge and the social sciences as well as the natural sciences (Díaz-Reviriego, Turnhout, and Beck Citation2019). There have been numerous other instances of such science-policy linkages, from efforts of the World Bank and OECD to provide economic advice for climate policy (Meckling and Allan Citation2020); to assessments of ozone layer depletion, acid rain, and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (Oppenheimer et al. Citation2019); to integrated science assessments within the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (O’Reilly Citation2017); to more regional efforts to co-produce usable knowledge for decision-makers (Norström et al. Citation2020). Key findings from this scholarship illustrate how to strengthen the relationship between science and policy, assessing the impacts of politics on the scientific process as well.

Much of this literature is grounded in the science of actionable knowledge, “an area of inquiry that aims to understand and catalyze transitions in scientific knowledge making and use” (Arnott, Mach, and Wong-Parodi Citation2020). Actionable knowledge, also sometimes referred to as convergence science, aims to produce—often in collaboration with civil society, local communities, and/or decision-makers—knowledge that is usable for policy and society (Mach et al. Citation2020; Norström et al. Citation2020; Dewulf et al. Citation2020). SOAK research is rooted in understandings of decision-making, and how science might inform those processes (Dewulf et al. Citation2020; Wong-Parodi et al. Citation2020). Usable science that can support decision making—in this case, for climate action through GHGIs—is about “both how science is produced (the push side) and how it is needed (the pull side) in different decision contexts” (Dilling and Lemos Citation2011). Actionable knowledge also takes into account social justice, and recognizes that knowledge is in and of itself a form of power. In the case of GHGI and carbon accounting, “there is power in holding authority over how carbon is defined and managed” (Gifford Citation2020).Whereas studies of these actionable knowledge interfaces have been rich and extensive, such studies of GHGIs in particular have been absent. With some notable exceptions (Pulles Citation2018; Gifford Citation2020), broader social science literature has paid limited attention to the processes through which GHGIs are developed.

2.2. Current international policy mechanisms and GHGI methodologies

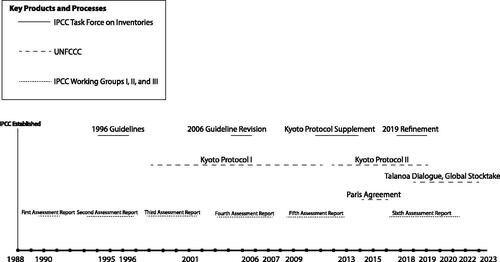

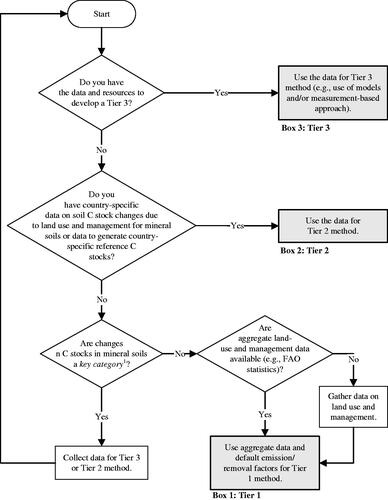

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) coordinates international climate change negotiations (“Background on the UNFCCC: The International Response to Climate Change” Citationn.d.), which rely on accurate reporting to inform emissions reductions commitments (Yona et al. Citation2020). Under the Paris Agreement—the first universal global accord on climate change—each signatory country agreed to national-level GHG emissions reductions (Jacquet and Jamieson Citation2016; Bodansky Citation2016; Falkner Citation2016). The Paris Agreement is the first time that GHGIs have been mandated for every UNFCCC member country (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Citation2015b). Previous agreements, such as the Kyoto Protocol, had binding agreements, though for a subset of countries only. Prior to the Paris Agreement, countries reported emissions, but under different frameworks, and most on a voluntary basis through National Communications. The Paris Agreement marks the first time that countries will be under the same reporting requirement, with more rigor as part of Article 13 of the Agreement, which includes a Transparency Framework (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Citation2015a). The UNFCCC invited the IPCC to provide scientific information about climate change from which international deliberations could draw (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change 2015b). The IPCC synthesizes climate science for policymakers (Hulme and Mahony Citation2010), presenting “‘policy relevant’ but not ‘policy-prescriptive’ assessments of the science of climate change” (Shaw and Robinson Citation2004). The less studied, but equally critical IPCC role is the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Programme (NGGIP). Within the NGGIP, the Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (TFI) produces methodologies for GHG reporting. These methods are the primary metrics by which countries’ GHG emissions are measured. The IPCC 2006 methodologies present inventory compilers with a decision tree by which they determine the appropriate tier approach (). Among GHGIs, the land sector is a key category for higher Tiers to be used, when possible, though doing so depends on the inventory compiler’s access to primary data. To assess progress on emissions reductions goals, countries submit National Inventory Reports using IPCC guidelines to the UNFCCC Secretariat, a process that the UNFCCC’s Subsidiary Body on Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) implements.

Figure 1. “Generic decision tree for identification of appropriate tier to estimate changes in carbon stoc ks in mineral soils by land use category,” reproduced directly from the IPCC (IPCC 2006, pg. 2.32). In Tier 1, inventory compilers find the appropriate default reference soil organic carbon stock based on their soil and climate type (see ). Note: 1. See Volume 1 Chapter 4, "Methodological Choice and Identification of Key Categories" (noting Section 4.1.2 on limited resources), for discussion of key categories and use of decision trees.

2.3. 2019 Refinement

Following the Paris Agreement as well as an informal invitation from the UNFCCC secretariat, the IPCC updated its guidelines in a process known as the “2019 Refinement”. Not intended to be a full revision nor update, the 2019 Refinement supplements a 2006 version with methodologies either receiving “no update, new guidance, or refinement” (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Citation2016). The 2019 Refinement was the first major change made to the IPCC guidelines since 2006. However, by nature of being a “refinement” and not an update or revision, the 2019 Refinement isn’t a new set of guidelines, but rather a subset of updated guidelines. Some GHGI methodologies were therefore not reviewed at all. As an important consequence, inventory compilers will have to refer to both the 2019 Refinement and a previous, complete set of guidelines—either the 1996 or 2006 versions—to produce inventories.

2.4. Forest soil organic carbon

Forest carbon helps illustrate how IPCC guidelines are applied in practice, as well as any inventorying challenges that may result. Forest carbon is important ecologically, as forests represent important ecosystems for both biodiversity and climate change (Goodale et al. Citation2002; Schlesinger and Andrews Citation2000; Schmitz et al. Citation2014). Forest carbon accounting became part of multilateral efforts as a result of the Kyoto Protocol (Schulze, Wirth, and Heimann Citation2000), and it is likely its use for carbon sequestration and climate mitigation will grow (Cook-Patton et al. Citation2020). Although forest carbon is important for climate policy, knowledge gaps remain, particularly related to carbon storage in different forest types.

For many reasons, forest soil organic carbon (FSOC) provides an illustrative approach through which to examine GHG reporting guidelines. Soil carbon is an important carbon sink, with the potential soil organic carbon pool being “triple that of the atmosphere” (Vermeulen et al. Citation2019). An important sector for climate change mitigation and carbon sequestration (Bossio et al. Citation2020; Rumpel et al. Citation2018), FSOC was added later to the IPCC guidelines, in the 2006 revision (National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme Citation2006). FSOC guideline development illustrates IPCC Tier 1 approaches. No plans were announced to update Tier 1 FSOC reporting (Section 4.2.2; ), per the Work Outline developed for the 2019 Refinement by the IPCC Plenary in 2016. In contrast, Tier 2 approaches were renewed (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Citation2016; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Citation2016). Finally, forest carbon accounting broadly has also been the subject of past interdisciplinary and social science research, particularly related to Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) programs (Gupta et al. Citation2012; Turnhout et al. Citation2017; den Besten, Arts, and Verkooijen Citation2014). For these reasons, examining the IPCC guidelines as informed by FSOC methodologies is likely to uncover opportunities to improve GHGIs.

2.5. Gaps between peer-reviewed scientific literature and inventory guidelines

Our review suggests that IPCC guidelines may not always reflect the latest and relevant scientific information required to project, and measure, GHG emissions reduction commitments (Couwenberg Citation2011; Liao et al. Citation2010; Villarino et al. Citation2014), an issue which has been identified for decades (Salt and Moran Citation1997). We acknowledge that part of the IPCC assessment process—which is applied to the IPCC guidelines—might deliberately ignore newer information as authors review data, so as not to over-emphasize newer findings whichh may be less well-tested. However, some discrepancies between this most recent scientific information might have important policy consequences. Such a scenario is especially prominent in FSOC Tier 1 methodologies (), because in the Tier 1 approach, carbon stocks are calculated differently from best practices outlined in peer-reviewed literature. For example, they use outdated biome classifications based on Whittaker (Citation1975) and do not include other variables that may substantially influence FSOC stocks, such as forest conversion or vegetation type (Liao et al. Citation2010). Moreover, according to the current Tier 1 reference table, estimated values have an error margin of +/− 90%. These mismatches between science and GHGI policy motivated our study. FSOC illustrates that more attention is needed to understand gaps in Tier 1 GHGI guidelines, especially since it is likely that Tier 1 methods will be primarily used by many countries reporting GHGIs as part of their Paris Agreement compliance (Yona et al. Citation2020). Since the land sector is also an area of emerging scientific knowledge, carrying with it more possibility for inventory compilers to misreport emissions—sometimes intentionally for their own benefit—it is also a GHG sector of particular importance, and where accurate scientific information is essential to effective policymaking.

3. Methods

3.1. Research approach

We apply a descriptive qualitative analysis (Creswell Citation2013; Rubin and Rubin Citation2005) often used in socio-environmental research, to explore the disconnects between IPCC guidelines and available peer-reviewed scientific literature, such as in the case of FSOC. We describe historical changes in how the guidelines incorporate scientific knowledge to facilitate further studies around key explanations for these disconnects. By developing careful research on the formal and informal practices of GHGI guidelines, in addition to themes and hypotheses, our study lays the descriptive and explanatory groundwork (Babbie Citation2001) for more integrated future research.

3.2. Semi-structured interviews

We use semi-structured interviews to better understand hidden processes and to develop inductively generated hypotheses that might explain observed patterns (Bernstein and Cashore Citation2012; Cashore and Howlett Citation2007; Levin et al. Citation2012; O’Neill et al. Citation2013; Vanhala Citation2017). We selected interviewees through stratified purposeful sampling (Creswell Citation2013), identifying and contacting individuals within specific groups to draw upon a range of experiences and expertise. We identified interviewees through their involvement with the IPCC guidelines and/or national- and subnational-level FSOC reporting. Interview data were coded with Nvivo 10 software. Semi-structured interview questions and a list of our interviewees can be found in Supplementary Materials. We conducted informational background

We analyzed interview data by first describing the processes through which the IPCC guidelines are developed, as well as the actors involved, which is currently absent from peer-reviewed literature. Second, we examined interviews as a whole to highlight any patterns or common themes relating to GHGI development. We used our collective interview data to understand key IPCC actors and develop a timeline of the IPCC TFI and unfolding key events (see ). We then highlighted patterns or repeated themes mentioned by multiple interviewees as we analyzed our data. These themes emerged from our data as a whole. An inductively developed theory or set of explanations for the potential themes we observed then became evident (George and Bennett Citation2005).

3.3. Observation and other interactions

Our methods included participant observation at public IPCC events and the UNFCCC COP23 conference, held in Bonn, Germany 6–17 November 2017. These observations served as additional data that we incorporated into our analysis, though interviews were our primary data source.

4. Results

4.1. Actors involved in development and revision of IPCC guidelines

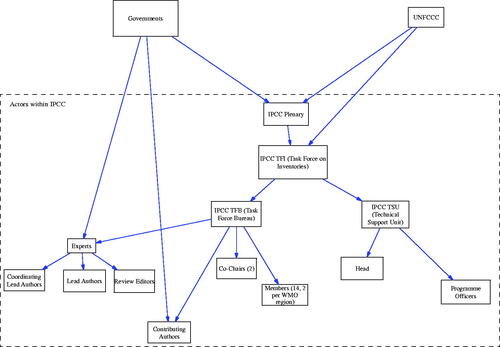

highlights the actors involved in IPCC guideline production, which the IPCC Plenary both triggers and finalizes. The TFI has two main administrative bodies: the Task Force Bureau (TFB), comprised of two Co-Chairs and fourteen Members, two for each World Meteorological Organization (WMO) region. The other body, the Technical Support Unit (TSU), is comprised of one Head and multiple Programme Officers. Authors of guideline documents are nominated by governments and selected by the TFB (Section 5.2.1). These authors include two Coordinating Lead Authors (CLAs) and many Lead Authors (LAs) and Review Editors (REs). Review Editors are responsible for compiling and responding to every comment received in the review process. Additionally, self-nominated Expert Reviewers (ERs) participate once drafts are completed. Combined, these actors influence the guidelines to varying degrees.

Figure 2. Different actors involved in producing IPCC guidelines. Arrows indicate potential influence of one actor over another, in the direction that the arrow is pointing. Authors responsible for writing guideline documents are nominated first by governments, then selected by the IPCC TFB, whose members are elected by the IPCC Plenary, which is comprised of government members. This is not a comprehensive organizational structure of the IPCC broadly, nor of efforts outside GHGIs; rather, it describes the actors involved in inventory guidelines.

4.2. Emerging themes in the development of IPCC guidelines

4.2.1. Process for IPCC guideline author selection

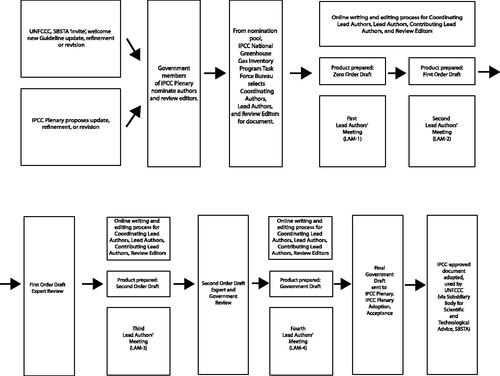

Nominated authors, as with every IPCC product, collectively write the GHGI guidelines. To be considered as a potential author (either Coordinating Lead Author (CLA), Lead Author (LA), or Review Editor (RE) positions), experts must be nominated by IPCC Plenary government members (). While governments must nominate these potential coauthors, experts often nominate themselves, voluntarily putting their names forward to government agencies. The TFI TFB can also nominate their own authors, though interviewees stated it was rare (n = 2, consensus among IPCC officials asked in Primary Interviews). The TFI TFB then selects experts from the nominee pool, considering demographics, region, and research discipline. For the 2019 Refinement, 190 Coordinating Lead Authors, Lead Authors, and Review Editors were selected by TFB from nearly 400 nominees. Most nominees who were not selected were offered Contributing Author (CA) positions. While authors are expected to provide expertise, they do not conduct original research (). Inherent to such a selection process is the potential for bias or political influence, since authors must be nominated by governments, or have a governmental connection to self-nominate.

Figure 3. Illustration of the IPCC NGGIP writing process. From the beginning through the end of the process, there is room for government influence, from the nomination of authors, to draft comments, to the approval of the final draft. The process typically takes about two years from beginning through to completion. In the case of the 2019 Refinement, the First Lead Authors’ Meeting (LAM-1) took place in 2017; the final draft was approved in 2019.

4.2.2. IPCC guideline writing process

The IPCC guidelines have evolved over time. They were first developed with International Energy Agency support, then hosted by the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies. Per interviews (n = 5 among both Primary and Follow-Up Interviews), initial guidelines concentrated on energy and transportation emissions, expanding to agriculture, forestry, and land use, largely as a result of this transition and in response to the Kyoto Protocol. The guidelines were designed through expert synthesis rather than systematic review of existing literature (“IPCC - Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories” Citation2017). Inconsistencies may result through this authorship: one IPCC author stated, referring to values used in IPCC guideline methodologies, “Some [reference stocks] just come because someone said, ‘Oh, this one paper said they're about 25, so let's just do that,’ and it becomes 25.” While this particular example by no means suggests that the expert synthesis process is generally developed in such an ad-hoc way, it nonetheless illustrates some of the challenges and knowledge gaps with which expert authors are sometimes required to grapple during the synthesis writing process. It also illustrates why authors are asked to provide expert judgment and assessment: in interviews, IPCC officials said expert synthesis was the most feasible means of synthesizing GHG emissions data (n = 7; consensus among IPCC interviewees asked in Primary Interviews) . GHGI guidelines developed through an expert synthesis process may differ from those developed through systematic review of peer-reviewed science.

The 2019 Refinement was developed using standard IPCC procedure, following the process developed for Assessment Reports, though outcomes of both efforts differ. While Assessment Reports are meant to provide policymakers with scientific information to make evidenced-based climate policy decisions, IPCC GHGI guidelines are, according to an IPCC official, “products being used by inventory compilers.” The guidelines are actively used by individuals and government agencies, informing regional, national, and multilateral mitigation efforts. Compared to Assessment Reports, which are updated on a relatively regular basis, the IPCC guidelines are irregularly updated (). As such, the GHGI guidelines are different from Assessment Reports in consequential ways, both in how they are used as well as how they are updated.

4.2.3. Development of IPCC guidelines tiered approach

The IPCC GHGI tiered approach, described here, was first developed to encourage countries with varying data availability to engage in mitigation. Three tiers are designed to cope with different levels of data availability. Tier 1 assumes no available primary data; Tier 2 assumes some national data; Tier 3 assumes extensive and robust primary data. Tier 1 methods provide default values that countries can use and apply depending on their regional context. For FSOC, Tier 1 methods provide default reference values for carbon stocks based on soil and climate type under native vegetation (). Furthermore, every country likely uses Tier 1 methodologies to some extent for at least one component of their National Inventory Reports, despite some countries’ extensive data. Such was the case for Canada, a country with relatively advanced primary data: for some sectors, compilers rely on Tier 1 methods to report emissions. As such, the tiers are meant to provide flexibility for GHGIs.

Table 1. Default reference FSOC stocks for mineral soils, reproduced directly from IPCC Tier 1 methodologies (IPCC Citation2006, pg. 2.31).

Table 2. Summary of Interviews.

Interviewees shared knowledge that illustrated benefits and drawbacks of the tiered approach. Some interviewees argued that, while Tier 3 methods seemed at times inaccessible to countries with limited research capacity to develop extensive primary data, they provided a level of resolution that promoted climate change mitigation (n = 3 among Primary Interviews). One interviewee, a provincial official whose sector relies entirely on Tier 1 methods, offered that Tier 3 allowed government officials to see progress made on emissions goals in “real time,” whereas the rough estimates of Tier 1 methods often didn’t demonstrate observable reductions in GHG emissions. Other interviewees advocated for the flexibility afforded by Tier 1 methods, saying that they allowed for a greater number of countries with limited data to compile inventories (n = 7 among Primary and Follow-Up Interviews). A government scientist and IPCC author argued that, while imprecise, Tier 1 approaches serve an important purpose: “Let’s say we want you to get on a bicycle from A to B. Well, first we build a bicycle. Then we add a motor. You don’t start with a Ferrari […] It’s more important for people to understand how the system works before specificity is applied.” Finally, another government scientist and IPCC coauthor stated that the IPCC envisioned countries using the Tier 3 approach when designing the guidelines, treating Tier 3 as the goal, that the Tier 1 approach “provide[s a] framework in order for everybody to be at a ground basis […] but we are not setting a roof.” The tiered approach is designed to navigate the nuances of data availability; however, it still allows for even well-resourced countries to use Tier 1 approaches, which might lead to inconsistent accounting, because countries may be motivated to apply the Tier that most favorably reports their emissions.

Moreover, the process to write and update guidelines is complex and challenging. One senior government scientist stated in interviews that even the guideline documents themselves are hard to understand, to the point that even foresters and government officials would not be able to parse them out. While official IPCC documents—and interviewees (n = 7, including 3 IPCC interviewees)—assert that inventory guidelines are accessible to all countries, regardless of the amount of primary data to which they have access, in interviews (n = 2, among Primary Interviews), senior IPCC leadership suggested the guidelines were developed in part with Annex I countries in mind as inventory compilers, as a result of the Kyoto Protocol. In interviews (n = 3, among Primary Interviews), senior officials indicated the IPCC did not feel as though a full revision of the guidelines was politically feasible—stating concerns that the UNFCCC would not approve the Refinement (see Section 4.2.4) if it was a full revision—in 2019, regardless of whether it would be recommended based upon scientific literature. Updating the guidelines would thus be politically challenging due to the UNFCCC adoption process, which might explain why they have not been fully revised since 2006.

4.2.4. Role of the UNFCCC and governments in the IPCC guidelines

Governments, particularly the UNFCCC and its Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), play a role in IPCC guidelines. Guideline development is in many ways triggered by the UNFCCC, and the process is influenced by government involvement before, during, and after writing is completed. For example, SBSTA “invites” an IPCC report, and can “welcome” it when it is finalized. Interviewees asserted that the IPCC is independent of the UNFCCC (n = 6, among Primary Interviews), and that these were invitations to complete work, not demands. Yet the “invitation” typically triggers the IPCC Plenary to produce a new guideline document (n = 2). As one senior IPCC official stated, the “IPCC is independent from the UNFCCC and can initiate work on its own. But in reality, in the case of the TFI, we start work in response to UNFCCC requests.” As such, political influence is a built-in feature of GHGI reporting.

Moreover, not all official IPCC TFI documents are necessarily considered as official UNFCCC guidelines; SBSTA must adopt the final IPCC document for it to be used by UNFCCC Parties. This structure within the UNFCCC could reinforce government influence, since the IPCC TFI explicitly states a desire to create documents that will be used by UNFCCC Parties as one of its two objectives (“IPCC - Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.” n.d.b. Accessed 11 May 2018. https://www.ipccnggip.iges.or.jp/org/aboutnggip.html. Many interviewees (n = 6, among Primary and Background Interviews) referred to the IPCC as an institution that is “policy relevant, not policy prescriptive.” However, the direct and indirect influence of policy on process—through funding, the nomination process, and final approval, among others—creates an environment in which IPCC work may be subject to political preference. One IPCC author and researcher stated that “political game-playing” takes place in the Second Order Draft of guideline documents, and that the final draft—the Government Draft—of each document is open to only government comments so that government members “feel that their concerns have been adequately addressed,” interview statements that reflect the “complex layering of compromises” found in other distinct, but related, research on the IPCC Working Group process (De Pryck Citation2021). While such political influence might be expected for a policy-facing document such as GHGI guidelines, the government approval process might lead to IPCC guidelines that may differ from peer-reviewed research, because governments are likely to be resistant to GHGI methodologies that may increase their nationally reported GHG emissions.

4.3. Emerging themes for inventory compilers

4.3.1. Complexity and knowledge gaps

Multiple interviewees indicated that the IPCC GHGI guidelines were not readily understandable (n = 8). Some reported difficulty understanding FSOC inventorying, with one researcher referring to them as “impenetrably complicated”. Many interviewees (n = 15) stated that forest carbon reporting is more challenging to understand compared to oil and gas emissions. Knowledge gaps also impact decision-making. An NGO campaigner also stated that it is hard to campaign for forest management policies with current variability of climate change impacts on forest carbon. The campaigner also expressed concern that the obscurity of FSOC may make it easier to greenwash, a strategy researchers have found in other land use policies (Gifford Citation2020; Johnson Citation2009; Rifai, West, and Putz Citation2015). A senior provincial government official echoed knowledge gap challenges, saying, “you don’t know what you don’t know” when making policy. Constraining information flows would inevitably impact GHGIs, as with any complex science-policy issue (Meadows Citation2010; Vermeulen et al. Citation2019). A senior governmental scientist said, “policy runs ahead of information needs,” a challenge other governmental scientists echoed. Complexity and knowledge gaps may influence GHGI guideline accessibility and implementation.

4.3.2. Limited resources

Unsurprisingly, provincial and federal officials and researchers, as well as NGO campaigners, highlighted a lack of resources (financial, as well as in gathering data, though the two are linked) to develop GHGIs. Many argued funding and research would allow them to systematically update FSOC approaches, but expressed low confidence in resources being allocated for this purpose. A senior government official mentioned a “paucity of field-based information” as a challenge in measuring FSOC; yet, their country is a global leader in FSOC reporting methods, highlighting the capacity limitations and resources required to accurately account for FSOC, which often requires substantial primary data. That being said, the IPCC cannot produce its own research when developing guidelines. As one senior IPCC official stated, “It’s for the research community to fill in the gap, not us. We can just point it out.” Moreover, soil carbon is briefly mentioned as “low” priority in the Land sector within the 2019 Refinement (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Citation2015). While resource challenges are common and not unique to GHGIs, they impact effective inventorying.

4.3.3. Inventory discrepancies

GHGIs may impact policy decisions, particularly if there is a lack of coordination and standardization across different levels of government (n = 4, among Primary Interviews). When asked if forestry operations would change if inventory methods were altered, a provincial official stated their government may cease harvesting first-generation forest on traditional indigenous territory. In another example, a federal agency calculated Canada’s National Inventory Reports (NIRs), even though data would be often provided by provincial agencies, who then used the NIRs to develop provincial inventory reports. One interviewee attributed this division of tasks between data collection and inventory compilation as a means of reducing duplication of effort. Some added that inventories were calculated nationally to avoid differences in emissions values between provincial and national compilations, even though the primary data used would be the same in both cases (n = 5). Interviewees attributed this potential difference in inventory reports between regional and national scales to the different methodologies that could be used to calculate inventories, with one saying, “We don't want to duplicate effort, that’s not efficient. And also, if you have two systems, there’s a risk of both systems producing different estimates and then you have to explain them.” These statements underscore the political underpinnings around inventorying, and how more accurate GHGIs might impact climate policies.

5. Discussion

5.1. Emerging themes

There are multiple processes at play that may be influencing GHGI methodologies. The following themes have emerged, drawing on existing literature (). They provide a framework through which IPCC guidelines may be better understood and studied in future research. Ultimately, the findings reflect that GHGIs are inherently political and subject to political interference that may impede climate progress, echoing similar findings in forest and land use accounting scholarship (Gupta et al. Citation2012; Turnhout et al. Citation2017), as well as broader climate policy (Carton et al. Citation2020; Skodvin Citation2000). The themes illustrated in are not only features of GHGI, but rather reflections of many science-policy and intergovernmental organizations. These themes interact to contribute to the challenges of GHGIs.

Table 3. Emerging themes driving the science and policy of greenhouse gas inventories, with norms and causal mechanisms.

5.1.1. Diverging logics and timeframes

Epistemic communities, “networks of knowledge-based communities with an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge” (P. Haas Citation2011), collectively contribute to GHGI inventory knowledge. These communities might create IPCC guidelines that have different outcomes than initially intended. Most interviewees (n = 19, among Background, Primary, and Follow-Up Interviews) noted that scientists and policymakers involved in climate action—and by extension, GHGIs ( and )—have different priorities and timeframes. Whereas policymakers desire rapidly available, simplified information to make timely policy decisions, scientists and the scientific method espouse a time-intensive, rigorous peer review process (Oppenheimer et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, the resulting guidelines may reflect these diverging logics: for example, tiered approaches may have been implemented to satisfy the demands and needs of the policy and UNFCCC processes. However, the tiered approach that is currently in place may not meet the needs of some countries compiling rigorous inventories as part of the Paris Agreement, since they are not able to consistently produce Tier 3-level data. Combined, both the actors involved as well as the guideline writing process itself may lead to politically meaningful discrepancies between the guidelines and the most up to date science.

5.1.2. Discursive power

Discursive power and rules govern the science-policy interface (Arts and Buizer Citation2009; Wesselink et al. Citation2013; Ney Citation2014). Discursive power can shape perceptions of GHGIs in the land use sector. Interviews suggested that expert authors make writing and methodology decisions based on what they believe will be palatable to government officials, a sentiment shared by all four senior officials interviewed. IPCC authors and/or officials develop their own assumptions of what the UNFCCC is likely to accept as an official document, and these assumptions dictate the boundaries for IPCC work. One official explained the decision to produce a Refinement, and not a Revision or Update—a process that would require inventory compilers to refer to multiple sets of methodologies, rather than one set of guidelines—was adopted by Plenary based on what they believed to be the “political mood” of the UNFCCC. The official explained there was concern that the UNFCCC SBSTA would not adopt an IPCC document unless it would be politically desirable; and that therefore the IPCC directs its work to what scientists and members believe is such (i.e. what interviewees call “policy relevant”). This same power might explain the reasoning that was also provided to explain relatively sporadic IPCC guideline updates, in comparison to Assessment Reports (). The same IPCC official said they did not think new reporting guidelines were what government members wanted. Assuming discursive power, one hypothesis could be that such modes of thought within the IPCC influence the synthesis of scientific information for governments. Discursive power, therefore, may lead to agenda-setting that constrains GHGI methodologies.

5.1.3. Procedural lock-in

Structural and procedural lock-in may also explain the IPCC guideline process. Path dependence and lock-in relate to the difficulty in changing a system once certain processes within it are entrenched (Levin et al. Citation2012). It is typically associated with negative environmental problems, although the concept can be applied positively to reinforce environmental solutions (Seto et al. Citation2016; Yona, Cashore, and Schmitz Citation2019). Within GHGIs, lock-in may be taking place with regards to the process of writing and refining GHGI guidelines. The guideline writing process might be better suited for a systematic review approach rather than an expert synthesis approach (Yona et al. Citation2020), but lock-in with regards to the GHGI structure and UNFCCC policies might make changes difficult to implement. Moreover, the IPCC also has an impact in agenda-setting for climate mitigation pathways (S. Beck and Oomen Citation2021); it similarly plays an important role in agenda-setting for GHGIs. Moving forward, assessing opportunities to address lock-in (Unruh Citation2002) for GHGIs may be beneficial.

5.1.4. Resource constraints

Resource constraints could potentially explain the challenges facing IPCC guidelines. Temporal and financial constraints can all influence the need to choose expert synthesis processes and tiered approaches, as the IPCC is limited in funding and support. Moreover, countries may lack the research and funding capacity to carry out Tier 3 methodologies. Many interviewees named resource constraints (n = 22) in describing challenges for evidence-based climate policy: there appears to be high demand for climate and carbon data, combined with few means to achieve it. One interviewee, the head of a major federal agency, stated that while there is an impetus to make data for GHGIs more accessible, it is “low on the totem pole” of government priorities. This interviewee mentioned policymakers were “less interested in precision or methodologies, [while] scientists want and need rigor, peer review, [and] model validation.” Combined with the perceived “paucity” of available field-based information, they argued that developing accurate soil organic carbon inventories was a challenging effort. These constraints are, evidently, not unique to GHGI methodologies (Dilling and Lemos Citation2011). Yet, considering the importance of accurate GHGIs for Paris Agreement compliance, we argue GHGIs could be prioritized in the future among other climate policies.

5.1.5. Organizational interests

Organizational, industry, and vested interests might influence discrepancies between scientific data and inventory guidelines. Governments may pre-select eligible candidates to be Lead Authors and Review Editors (). This same government-populated Plenary reviews drafts and approves documents in Plenary. As such, the IPCC Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories’ process relies on external organizational input to direct their work, and the political influence from these actors may have an impact on the types of methodologies that are then proposed. Similarly, on a country level, industries may influence inventorying processes. Some inventory compilers and government officials indicated strong connections between the forest accounting sector and the forestry industry, which could potentially influence inventory methodology decisions. There is already a documented history of forestry industry influence on forest policy (Bernstein and Cashore Citation2012; Steel, Pierce, and Lovrich Citation1996), as there has been of fossil fuel industry influence on climate change policy (Oreskes and Conway Citation2010). Of course, such industries and special interests could also stand to benefit from favorable GHG emissions reporting, similar to corporate GHG reporting practices, where “carbon accounting [that] is an uneven technical and political process that makes multiple forms of carbon legible on financial markets but does little to physically address atmospheric carbon concentrations” (Gifford Citation2020). These organizational interests might influence certain GHGI methodologies.

5.2. Implications for FSOC reporting

The challenges of GHG inventorying are further magnified for FSOC, a sector where more scientific uncertainties exist (Van Noordwijk Citation2015). Whereas the energy sector is considered a relatively closed system, forest and ecosystem carbon is understood as a dynamic system, and a potential carbon sink rather than source (Pulles Citation2018). Since there are also more gaps in scientific knowledge of FSOC (Tian et al. Citation2016) than there are in the energy sector, there is opportunity for discursive power to influence the methodologies governing forest ecosystems.

Carbon sources and sinks resulting from complex ecosystem interactions, as well as differing management practices, make it harder to report FSOC stocks with confidence. Many interviewees (n = 15) noted that forest stocks and GHG emissions in particular were harder to evaluate than oil because of emerging scientific data and persisting knowledge gaps. Balancing such complexity challenges will be important to FSOC reporting moving forward, likely benefitting from more research, which will also provide a contribution to existing literature on forest management and environmental governance. An emphasis on empowerment and integration of various knowledge stakeholders (Maas et al. Citation2021) might also improve the GHGI inventorying process in land and FSOC sectors.

5.3. Political implications

Our analysis presents political implications, as would be likely any research at the intersection of science and society (Arnott, Mach, and Wong-Parodi Citation2020; Rest and Halpern Citation2007; Morgan Citation2017). While there are clear technical and ecological aspects to GHG inventorying, there are also political motivations to present inventories that are favorable to the GHGI-compiling entity (Whitington Citation2016). Though past literature examining whether governments may “misreporting greenhouse gas emissions for their benefit” found that some discrepancies between GHGI guidelines are inconsequential, constituting “de minimis” uncertainties (Swart et al. Citation2007) that make current guidelines “good enough” (Pulles Citation2017), the statement from a provincial forestry department official that the agency would not be clear-cutting temperate rainforest on traditional indigenous land suggests that such misreporting may indeed be taking place. Furthermore, there are justice implications in some instances of inaccurate GHGIs, echoing prior research on the environmental injustice of certain forestry and land use practices (Farris Citation2009; Marion Suiseeya Citation2017). Finally, an IPCC staff member’s comment that the 2019 Refinement received an order of magnitude fewer comments than the contemporaneous Special Report on 1.5 Degrees suggests that GHGI methodologies are not as closely studied or scrutinized. Indeed, while “[a]ccounting can sometimes make ‘things’ appear uncontroversial and a-political or even non-political, […] technical debates about accounting rules, principles and standards involve intense power struggles” (Lovell et al. Citation2010); we argue that the same is true of GHGIs. Addressing these challenges requires technical work on problem-focused metrics, and political science research on the power dynamics that might have caused this shift in the first place (Newell and Paterson Citation2009), along with corresponding institutional reforms (Cashore and Bernstein Citation2021). Ultimately, we suggest including technical GHGI methodologies as part of further research efforts examining global climate politics, in particular as part of research on the UNFCCC process.

Greenhouse gas inventory methodologies may appear as technical documents, but they are embedded in policy processes that may be subject to political influence. Previous scholarship examining forest carbon (though not country GHGIs explicitly) argues that “carbon accounting is often seen as purely technical and apolitical. […] Carbon accounting produces one way of knowing carbon—as a quantified commodity—but different accounting methods produce varying results, a reality that sparked the growth of multiple professional verification and certification organizations” (Gifford Citation2020). Arguably, “impenetrably complicated” GHGI guidelines could make this subset of climate science more vulnerable to outside influence.

5.4. Research limitations and implications for policy

Our research builds on existing literature on the IPCC and the science-policy interface, contributing a specific analysis of the IPCC’s GHGI guidelines. While this paper aims to first add to peer-reviewed literature by describing and explaining the IPCC guideline process, its scope was also necessarily constrained to focus on FSOC in particular. While the hypotheses generated in this paper may very well apply to other sectors of GHG emissions, these would need to be further tested and assessed. Moreover, it is possible that making the necessary changes to incorporate the most up-to-date research with GHGI guidelines at the UNFCCC level may be difficult to implement politically, as countries are already facing gaps to adapt, build capacities, and change institutional arrangements to develop GHGIs. While we do not argue that making changes to improve GHGIs will be easy nor simple, we do highlight that, as with most science-policy efforts, strengthening the relationship between the best available information will contribute to effective, informed decision-making.

6. Conclusion

Greenhouse gas emissions inventorying is critical to Paris Agreement commitments and enforcement, as well as the Talanoa Dialogue and Global Stocktake (Yona et al. Citation2020). The IPCC has been leading inventory guideline development (National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme Citation2006), an important role: accurate, stringent, rigorous guidelines for GHG inventorying, accounting, and reporting can ensure that the Paris Agreement is effective. It could help contribute to countries’ compliance with their Nationally Determined Contributions for GHG emissions reductions. We identify key hypotheses with which to guide urgently needed social science research into the science-guidelines gap: diverging logics and timeframes, discursive power, lock-in, resource constraints, organizational power, uncertainty, and complexity may influence the rigor and accuracy of GHGI guidelines. Together, these findings highlight the ways in which the challenges and structure of the IPCC guideline development process may lead to a divergence from the best available evidence, with policy implications.

While this research project focused on the IPCC guidelines with a particular lens on FSOC, further research may assess the extent to which similar dynamics exist in broader land-use GHG reporting, and in GHG reporting in other sectors, such as energy sources (in particular unconventional energy sources such as fracking). Further research may also test the hypotheses outlined in this research paper. Increasing GHGI knowledge development, in turn, is critical for developing strategies that better incorporate peer-reviewed literature into GHGI guidelines. To be sure, the IPCC provides a critical resource to governments and policymakers for climate change action (Carraro et al. Citation2015; Robinson and Shaw Citation2004). GHGIs are, indeed, essential to the success of the Paris Agreement. Efforts to improve GHGIs will therefore help ensure that climate policies that are presented and implemented are grounded in sound scientific data about carbon emissions and sinks and, by so doing, will be expected to lead to effective and durable climate action.

Ethical approval

This research project was granted Exemption Status by the Yale University Institutional Review Board, IRB Protocol ID 2000020397. Follow-up interviews, conducted in September and October 2018, were granted exemption status by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board, IRB Protocol ID 47751. Interview data was kept securely in accordance with the plans outlined in these IRB applications. As part of our protocol, and in recognition of the potentially sensitive nature of our interviewees’ responses, we are not publishing our raw interview data and are not publicly identifying our interviewees.

Author contributions

L.Y., B.W.C., and M.A.B. conceived and designed the research. L.Y. conducted the research and analyzed the data. L.Y. wrote the paper. B.W.C. and M.A.B. provided comments and editing.

Data accessibility statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Oswald Schmitz for helping guide this research, and Julia Marton-Lefèvre for facilitating interviews. LY thanks interviewees for their time, and Katharine Mach for guidance and manuscript feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abson, David J., Joern Fischer, Julia Leventon, Jens Newig, Thomas Schomerus, Ulli Vilsmaier, Henrik von Wehrden, et al. 2017. “Leverage Points for Sustainability Transformation.” Ambio 46 (1): 30–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

- Adler, Emanuel, and Peter M. Haas. 1992. “Conclusion: Epistemic Communities, World Order, and the Creation of a Reflective Research Program.” International Organization 46 (1): 367–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300001533.

- Almeida, Lia de Azevedo, and Ricardo Corrêa Gomes. 2020. “MAIP: Model to Identify Actors’ Influence and Its Effects on the Complex Environmental Policy Decision-Making Process.” Environmental Science & Policy 112 (October): 69–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.04.016.

- Arnott, James C., Katharine J. Mach, and Gabrielle Wong-Parodi. 2020. “Editorial Overview: The Science of Actionable Knowledge.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 42 (February): A1–A5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.03.007.

- Arts, Bas, and Marleen Buizer. 2009. “Forests, Discourses, Institutions: A Discursive-Institutional Analysis of Global Forest Governance.” Forest Policy and Economics, Discourse and Expertise in Forest and Environmental Governance 11 (5–6): 340–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2008.10.004.

- Babbie, Earl. 2001. The Practice of Social Research, Ninth Edition. 9th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth Thomson Learning.

- “Background on the UNFCCC: The International Response to Climate Change.” n.d. Accessed 8 May 2017. http://unfccc.int/essential_background/items/6031.php.

- Beck, S., and Jeroen Oomen. 2021. “Imagining the Corridor of Climate Mitigation – What is at Stake in IPCC’s Politics of Anticipation?” Environmental Science & Policy 123 (September): 169–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.05.011.

- Beck, Silke, and Martin Mahony. 2018. “The IPCC and the New Map of Science and Politics.” WIREs Climate Change 9 (6): e547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.547.

- Bernstein, Steven, and Benjamin Cashore. 2012. “Complex Global Governance and Domestic Policies: Four Pathways of Influence.” International Affairs 88 (3): 585–604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01090.x.

- Besten, Jan Willem den., Bas Arts, and Patrick Verkooijen. 2014. “The Evolution of REDD Plus: An Analysis of Discursive-Institutional Dynamics.” Environmental Science & Policy 35 (Journal Article): 40–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.03.009.

- Biermann, F., K. Abbott, S. Andresen, K. Backstrand, S. Bernstein, M. M. Betsill, H. Bulkeley, et al. 2012. “ Science and government. Navigating the Anthropocene: Improving Earth System Governance.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 335 (6074): 1306–1307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1217255.

- Bodansky, Daniel. 2016. “The Paris Climate Change Agreement: A New Hope?” American Journal of International Law 110 (2): 288–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.5305/amerjintelaw.110.2.0288.

- Bossio, D. A., S. C. Cook-Patton, P. W. Ellis, J. Fargione, J. Sanderman, P. Smith, S. Wood, et al. 2020. “The Role of Soil Carbon in Natural Climate Solutions.” Nature Sustainability 3 (5): 391–398. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0491-z.

- Carraro, Carlo, Ottmar Edenhofer, Christian Flachsland, Charles Kolstad, Robert Stavins, and Robert Stowe. 2015. “ CLIMATE CHANGE. The IPCC at a crossroads: Opportunities for Reform.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 350 (6256): 34–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4419.

- Carton, Wim, Adeniyi Asiyanbi, Silke Beck, Holly J. Buck, and Jens F. Lund. 2020. “Negative Emissions and the Long History of Carbon Removal.” WIREs Climate Change 11 (6): e671. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.671.

- Cashore, Benjamin, and Steven Bernstein. 2021. “Bringing the Environment Back In: Overcoming the Tragedy of the Diffusion of the Commons Metaphor.” In Perspectives on Politics. Cambridge University Press: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics

- Cashore, Benjamin, and Michael Howlett. 2007. “Punctuating Which Equilibrium? Understanding Thermostatic Policy Dynamics in Pacific Northwest Forestry.” American Journal of Political Science 51 (3): 532–551. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00266.x.

- Cook-Patton, Susan C., Sara M. Leavitt, David Gibbs, Nancy L. Harris, Kristine Lister, Kristina J. Anderson-Teixeira, Russell D. Briggs, et al. 2020. “Mapping Carbon Accumulation Potential from Global Natural Forest Regrowth.” Nature 585 (7826): 545–550. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2686-x.

- Couwenberg, J. 2011. “Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Managed Peat Soils: Is the IPCC Reporting Guidance Realistic?” Mires and Peat 8. Article 02, 1–10.

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- De Pryck, Kari. 2021. “Intergovernmental Expert Consensus in the Making: The Case of the Summary for Policy Makers of the IPCC 2014 Synthesis Report.” Global Environmental Politics 21 (1): 108–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00574.

- Devès, Maud H., Michel Lang, Paul-Henri Bourrelier, and François Valérian. 2017. “Why the IPCC Should Evolve in Response to the UNFCCC Bottom-Up Strategy Adopted in Paris? An Opinion from the French Association for Disaster Risk Reduction.” Environmental Science & Policy 78 (December): 142–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.10.001.

- Dewulf, Art, Nicole Klenk, Carina Wyborn, and Maria Carmen Lemos. 2020. “Usable Environmental Knowledge from the Perspective of Decision-Making: The Logics of Consequentiality, Appropriateness, and Meaningfulness.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 42 (February): 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.10.003.

- Díaz-Reviriego, I., E. Turnhout, and S. Beck. 2019. “Participation and Inclusiveness in the Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” Nature Sustainability 2 (6): 457–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0290-6.

- Dilling, Lisa, and Maria Carmen Lemos. 2011. “Creating Usable Science: Opportunities and Constraints for Climate Knowledge Use and Their Implications for Science Policy.” Global Environmental Change 21 (2): 680–689. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.11.006.

- Falkner, Robert. 2016. “The Paris Agreement and the New Logic of International Climate Politics.” International Affairs 92 (5): 1107–1125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12708.

- Farris, Melissa. 2009. “The Sound of Falling Trees: Integrating Environmental Justice Principles into the Climate Change Framework for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) Note.” Fordham Environmental Law Review 20 (3): 515–550.

- George, Alexander L., and Andrew Bennett. 2005. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. BCSIA Studies in International Security. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gifford, Lauren. 2020. “You Can’t Value What You Can’t Measure’: A Critical Look at Forest Carbon Accounting.” Climatic Change 161 (2): 291–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02653-1.

- Goodale, Christine, Michael Apps, Richard Birdsey, Christopher Field, Linda Heath, Richard Houghton, Jennifer Jenkins, et al. 2002. “Forest Carbon Sinks in the Northern Hemisphere.” Ecological Applications 12 (3): 891–899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2002)012[0891:FCSITN]2.0.CO;2.

- Gupta, Aarti, Eva Lövbrand, Esther Turnhout, and Marjanneke J. Vijge. 2012. “In Pursuit of Carbon Accountability: The Politics of REDD + Measuring, Reporting and Verification Systems.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 4 (6): 726–731. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2012.10.004.

- Haas, Peter. 2011. “Epistemic Communities.” In International Encyclopedia of Political Science, edited by Bertrand Badie, Dirk Berg-Schlosser, and Leonardo Morlino. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Haas, Peter M. 1992. “Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination.” International Organization 46 (1): 1–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300001442.

- Hallegatte, Stéphane, and Katharine J. Mach. 2016. “Make Climate-Change Assessments More Relevant.” Nature News 534 (7609): 613–615. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/534613a.

- Howlett, Michael, and Benjamin Cashore. 2009. “The Dependent Variable Problem in the Study of Policy Change: Understanding Policy Change as a Methodological Problem.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 11 (1): 33–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980802648144.

- Hulme, Mike, and Martin Mahony. 2010. “Climate Change: What Do We Know About the IPCC?” Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 34 (5): 705–718. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133310373719.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2015. “IPCC Expert Meeting for Technical Assessment of IPCC Inventory Guidelines (AFOLU Sector) Co-Chairs Summary.”

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2016. “Decisions Adopted by the Panel at the 43rd Session of the IPCC.”

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories 2016. “Report of IPCC Scoping Meeting for a Methodology Report(s) to Refine the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.” Belarus.

- “IPCC - Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.” n.d.a. Accessed 27 November 2016. http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/vol4.html.

- “IPCC - Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.” n.d.b. Accessed 11 May 2018. https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/org/aboutnggip.html.

- IPCC. 2019. IPCC 2019, 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Edited by E. Calvo Buendia, K. Tanabe, A. Kranjc, J. Baasansuren, M. Fukuda, S. Ngarize, A. Osako, Y. Pyrozhenko, P. Shermanau, and S. Federici. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

- Jacquet, Jennifer, and Dale Jamieson. 2016. “Soft but Significant Power in the Paris Agreement.” Nature Climate Change 6 (7): 643–646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3006.

- Jamsranjav, Baasansuren. 2017. “2019 Refinement to the 2006 IP CC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.” Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Task Force on Inventories Side Event presented at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change 23rd Conference of the Parties, Bonn, Germany, November 7. http://www.ipccnggip.iges.or.jp/presentation/1711_3_2019Refinement.pdf.

- Johnson, Eric. 2009. “Goodbye to Carbon Neutral: Getting Biomass Footprints Right.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 29 (3): 165–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2008.11.002.

- Kelemen, Eszter, György Pataki, Zoi Konstantinou, Liisa Varumo, Riikka Paloniemi, Tânia R. Pereira, Isabel Sousa-Pinto, Marie Vandewalle, and Juliette Young. 2021. “Networks at the Science-Policy-Interface: Challenges, Opportunities and the Viability of the ‘Network-of-Networks’ Approach.” Environmental Science & Policy 123 (September): 91–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.05.008.

- Klaaßen, Lena, and Christian Stoll. 2021. “Harmonizing Corporate Carbon Footprints.” Nature Communications 12 (1): 6149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26349-x.

- Kornek, Ulrike, Christian Flachsland, Chris Kardish, Sebastian Levi, and Ottmar Edenhofer. 2020. “What is Important for Achieving 2 °C? UNFCCC and IPCC Expert Perceptions on Obstacles and Response Options for Climate Change Mitigation.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (2): 024005. doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab6394.

- Levin, Kelly, Benjamin Cashore, Steven Bernstein, and Graeme Auld. 2012. “Overcoming the Tragedy of Super Wicked Problems: Constraining Our Future Selves to Ameliorate Global Climate Change.” Policy Sciences 45 (2): 123–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0.

- Liao, Chengzhang, Yiqi Luo, Changming Fang, and Bo Li. 2010. “Ecosystem Carbon Stock Influenced by Plantation Practice: Implications for Planting Forests as a Measure of Climate Change Mitigation.” PLOS One 5 (5): e10867. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010867.

- Liggio, John, Shao-Meng Li, Ralf M. Staebler, Katherine Hayden, Andrea Darlington, Richard L. Mittermeier, Jason O’Brien, et al. 2019. “Measured Canadian Oil Sands CO2 Emissions Are Higher than Estimates Made Using Internationally Recommended Methods.” Nature Communications 10 (1): 1863. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09714-9.

- Livingston, Jasmine E., and Markku Rummukainen. 2020. “Taking Science by Surprise: The Knowledge Politics of the IPCC Special Report on 1.5 Degrees.” Environmental Science & Policy 112 (October): 10–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.05.020.

- Lovell, Heather, Thereza Sales de Aguiar, Jan Bebbington, and Carlos Larrinaga. 2010. “Accounting for Carbon.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2291460. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2291460.

- Maas, Timo Y., Jasper Montana, Sandra van der Hel, Martin Kowarsch, Willemijn Tuinstra, Machteld Schoolenberg, Martin Mahony, et al. 2021. “Effectively Empowering: A Different Look at Bolstering the Effectiveness of Global Environmental Assessments.” Environmental Science & Policy 123 (September): 210–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.05.024.

- Mach, Katharine J., and Christopher B. Field. 2017. “Toward the Next Generation of Assessment.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 42 (1): 569–597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-061007.

- Mach, Katharine J., Maria Carmen Lemos, Alison M. Meadow, Carina Wyborn, Nicole Klenk, James C. Arnott, Nicole M. Ardoin, et al. 2020. “Actionable Knowledge and the Art of Engagement.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, Advancing the science of actionable knowledge for sustainability 42 (February): 30–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.002.

- Marion Suiseeya, KimberlyR. 2017. “Contesting Justice in Global Forest Governance: The Promises and Pitfalls of REDD+.” Conservation and Society 15 (2): 189. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/cs.cs_15_104.

- Meadows, Donella. 2010. “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System.” The Solutions Journal 1 (1): 41–49.

- Meckling, Jonas, and Bentley B. Allan. 2020. “The Evolution of Ideas in Global Climate Policy.” Nature Climate Change 10 (5): 434–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0739-7.

- Morgan, M. Granger. 2017. Theory and Practice in Policy Analysis: Including Applications in Science and Technology. Cambridge, UK; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme 2006. “2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.”Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, Eggleston H.S., Buendia L., Miwa K., Ngara T. and Tanabe K. (eds). Published: IGES, Japan.

- Newell, Peter, and Matthew Paterson. 2009. “The Politics of the Carbon Economy.” In The Politics of Climate Change: A Survey, edited by Maxwell Boykoff, 80–99. London: Routledge.

- Ney, Tara. 2014. “A Discursive Analysis of Restorative Justice in British Columbia.” Restorative Justice 2 (2): 165–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.5235/20504721.2.2.165.

- Norström, Albert V., Christopher Cvitanovic, Marie F. Löf, Simon West, Carina Wyborn, Patricia Balvanera, Angela T. Bednarek, et al. 2020. “Principles for Knowledge Co-Production in Sustainability Research.” Nature Sustainability 3 (3): 182–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2.

- O’Neill, Kate, Erika Weinthal, Kimberly R. Marion Suiseeya, Steven Bernstein, Avery Cohn, Michael W. Stone, and Benjamin Cashore. 2013. “Methods and Global Environmental Governance.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 38 (1): 441–471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-072811-114530.

- Oppenheimer, Michael, Naomi Oreskes, Dale Jamieson, Keynyn Brysse, O’Reilly Jessica, Matthew Shindell, and Milena Wazeck. 2019. Discerning Experts: The Practices of Scientific Assessment for Environmental Policy. 1st ed. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

- O’Reilly, Jessica. 2017. The Technocratic Antarctic: An Ethnography of Scientific Expertise and Environmental Governance. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. 2010. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming/Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

- Pulles, Tinus. 2017. “Did the UNFCCC Review Process Improve the National GHG Inventory Submissions?” Carbon Management 8 (1): 19–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2016.1271256.

- Pulles, Tinus. 2018. “Twenty-Five Years of Emission Inventorying.” Carbon Management 9 (1): 1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2018.1426970.

- Rest, Kathleen M., and Michael H. Halpern. 2007. “Politics and the Erosion of Federal Scientific Capacity: Restoring Scientific Integrity to Public Health Science.” American Journal of Public Health 97 (11): 1939–1944. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.118455.

- Rifai, Sami W., Thales A. P. West, and Francis E. Putz. 2015. “Carbon Cowboys’ Could Inflate REDD + Payments through Positive Measurement Bias.” Carbon Management 6 (3–4): 151–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2015.1097008.

- Robinson, John, and A. Shaw. 2004. “Imbued Meaning: Science-Policy Interactions in the IPCC.” In: Frank Biermann, Sabine Campe, Klaus Jacob, eds. 2004. Proceedings of the 2002 Berlin Conference on the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change “Knowledge for the Sustainability Transition. The Challenge for Social Science”, Global Governance Project: Amsterdam, Berlin, Potsdam and Oldenburg. pp. 143-153. (15) (PDF) Imbued Meaning: Science-Policy Interactions in the IPCC. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235961183_Imbued_Meaning_Science-Policy_Interactions_in_the_IPCC [accessed Dec 23 2021].

- Rubin, Herbert J., and Irene Rubin. 2005. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Rumpel, Cornelia, Farshad Amiraslani, Lydie-Stella Koutika, Pete Smith, David Whitehead, and Eva Wollenberg. 2018. “Put More Carbon in Soils to Meet Paris Climate Pledges.” Nature 564 (7734): 32–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07587-4.

- Rutherford, Jeffrey S., Evan D. Sherwin, Arvind P. Ravikumar, Garvin A. Heath, Jacob Englander, Daniel Cooley, David Lyon, Mark Omara, Quinn Langfitt, and Adam R. Brandt. 2021. “Closing the Methane Gap in US Oil and Natural Gas Production Emissions Inventories.” Nature Communications 12 (1): 4715. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25017-4.

- Salt, Julian E., and Andrea Moran. 1997. “International Greenhouse Gas Inventory Systems: A Comparison between CORINAIR and IPCC Methodologies in the EU.” Global Environmental Change 7 (4): 317–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(97)00015-0.

- Schlesinger, William H., and Jeffrey A. Andrews. 2000. “Soil Respiration and the Global Carbon Cycle.” Biogeochemistry 48 (1): 7–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006247623877.

- Schmitz, Oswald J., Peter A. Raymond, James A. Estes, Werner A. Kurz, Gordon W. Holtgrieve, Mark E. Ritchie, Daniel E. Schindler, et al. 2014. “Animating the Carbon Cycle.” Ecosystems 17 (2): 344–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-013-9715-7.

- Schulze, Ernst-Detlef, Christian Wirth, and Martin Heimann. 2000. “Managing Forests after Kyoto.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 289 (5487): 2058–2059. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5487.2058.

- Seto, Karen C., Steven J. Davis, Ronald B. Mitchell, Eleanor C. Stokes, Gregory Unruh, and Diana Ürge-Vorsatz. 2016. “Carbon Lock-In: Types, Causes, and Policy Implications.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 41 (1): 425–452. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085934.

- Shaw, Alison, and John Robinson. 2004. “Relevant But Not Prescriptive: Science Policy Models Within the IPCC.” Philosophy Today 48 (9999): 84–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.5840/philtoday200448Supplement9.

- Skodvin, Tora. 2000. “Structure and Agent in the Scientific Diplomacy of Climate Change.” In Structure and Agent in the Scientific Diplomacy of Climate Change: An Empirical Case Study of Science-Policy Interaction in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by Tora Skodvin, 225–233. Advances in Global Change Research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-48168-5_9.

- Steel, Brent S., John C. Pierce, and Nicholas P. Lovrich. 1996. “Resources and Strategies of Interest Groups and Industry Representatives Involved in Federal Forest Policy.” The Social Science Journal 33 (4): 401–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0362-3319(96)90014-2.