Abstract

Whilst design politics is an increasingly topical focus in the design field, in practice, design for policy has been normatively presented as a people-centric approach to public policymaking devoid of political or ideological agendas. Up to now, design for policy has exclusively been conceived as embedded within governmental structures, thus adopting a technocratic, internal, and top-down approach to, and understanding of, public policymaking. We argue that most often, this understanding and practice of design for policy establishes and mediates public problems from the standpoint of the government body addressing those problems. In this paper, we take a new and distinct point of departure to design for policy in which design is implicated in the practice of policymaking from below through processes of collective action. Design for Policy from Below moves from an intra-governmental lens to a negotiated exchange between social actors and government. In turn, this informs strategic collective action required to gain political support and leverage efforts to pressure power structures to acknowledge and adopt policy frames and options. To this end, we examine the conflictual power dynamics and negotiation-based approaches to influencing government policymaking processes and model the messy interplay between government-led policymaking and the activities of social innovators aiming at changing policy outcomes. Finally, we synthesize these insights into a conceptual model offering a novel viewpoint on how we can more critically understand the politics at play in design theory and practice engaged with policymaking.

1. Introduction

Design for policy has been normatively presented as a clear-cut citizen-centred and processual approach to effectively oil the wheels of government, thereby improving public policymaking outcomes, devoid of political or ideological agendas (Kimbell and Bailey Citation2017; Lewis, McGann, and Blomkamp Citation2020).

Simultaneously, design politics has gained traction in design research, leading to critiques of the value-free claims of design approaches in policymaking (Vaz and Ferreira Citation2021). Further, critical and participatory design practices consider design’s potential and capacity as a tool for social change, imbricating design in explicitly political contexts of collective action, grassroots organizing, and social movements relevant to policy change. Whilst not solely consultative, the predominant understanding and practice of design for policy establishes and mediates public problems from the standpoint of the government body addressing those problems, with no evidence of how it can boost bottom-up processes (Giraldo Nohra, Pereno, and Barbero Citation2020). This has meant supporting top-down policymaking where design operates for and within government bodies. The complex position this puts designers in as operators “between” society and government has been discussed by the ways in which design for policy might, for instance, facilitate market logics in government (Kimbell and Bailey Citation2017; Julier Citation2017).

This begs the question, how can design for policy be understood from a meso-level, negotiated perspective, articulating the practices of grassroots action? Whilst we acknowledge this is but one perspective on the political in this realm, it is a step toward a more critical take on the field and practice of design for policy. In this paper, we will broadly refer to the social actors (e.g. activists, social movements, community organizers) engaging in grassroots policymaking as “social innovators” (SI).

We address this question based on the review of literature on policymaking models and community organizing and past engagement with a major community organizing entity in the UK, a Brazilian private think-tank with a focus on the public sector, and nineteen innovation intermediaries in five Southern African countries.

We propose a distinct take on the nature and engagement of design for policy, placing it as acting at the confluence where negotiated positions and practices play out, where those same design tools (e.g. personas, blueprints) and expertise are deployed to impact public policymaking through grassroots action. In the policy realm, framing is the ability to define a public issue compellingly to gain public support for government action. We argue design can support the strategic framing of public issues affecting their likelihood of gaining support and engaging different people in forming public problems and policy options in a dialogic dynamic between government and grassroots actors—aspects vastly overlooked in the design for policy literature.

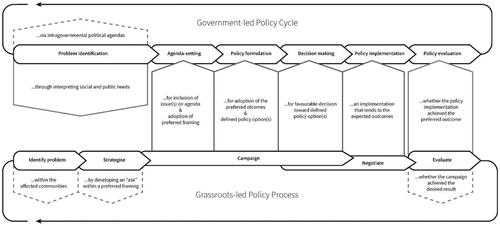

We initially examine how design for policy has been primarily conceptualized as a government-led and top-down practice, further presenting a model that interfaces the stages of the public policymaking process with the activities carried out during grassroots-led campaigns. Lastly, we conceptualize sense-making and meaning-making as two distinctive design features occurring at different stages of the government and grassroots-led policy processes.

2. Design for policymaking

Policy design is seeing a renewed momentum (Peters, Citation2018), emerging as a leading-edge issue with the advent of design thinking (Howlett Citation2014) while being increasingly applied to multiple public policy contexts (Kimbell and Vesnić-Alujević Citation2020). While Mintrom and Thomas (Citation2018) note that in policy studies design has always been an integral part of policy development, design thinking, design methods, creativity, and participation are increasingly being applied today to policymaking, service, and decision-making processes and practices (van Buuren et al. Citation2020). A recent UK Arts and Humanities Research Council report defines design for policy as a “creative, user-centred approach to problem-solving engaging users, stakeholders and delivery teams at multiple stages of the policy process” (Whicher Citation2020, 4). For over a decade, organizations such as the EU and the UN have endorsed the application of design in public policymaking, combining human and user-centred focus, empathic, co-creative, and iterative processes, and experimental testing and prototyping approaches for validation (Allio Citation2014).

Yet, critical voices raise concerns that designers may be instrumental in government unloading its responsibilities onto citizens (e.g. Julier (Citation2011)). Moreover, Schneider et al. (Citation2013) notes the cognitive biases and the potential damage through deliberately deceptive and unfounded factors influencing design element choices in the interplay of policy, political, and personal goals; elements which are seldom acknowledged in the design for policy literature. On the other hand, design for policy embeds participatory approaches, and the history of PD is grounded in democratic action (Telier Citation2011; Huybrechts, Benesch, and Geib Citation2017). As Dixon, McHattie, and Broadley (Citation2021) note, however, the key question is, how political should participation be?

Moreover, experimentation, a core practice of design for policy, involves convening diverse stakeholders (e.g. citizens, officials, academics) to generate novel solutions (Smith Citation2009). Often this multi-stakeholder engagement happens within “labs.” While appearing to represent novel forms of democracy (Asenbaum and Hanusch Citation2021), these can also represent technocratic tendencies for elite control and defuturing practices (Fry Citation2008). As Asenbaum and Hanusch (Citation2021) note, solutionism drives future-making in a particular way, aiming at concrete, well-defined results, and expected change within pre-defined settings. Similarly, testing and prototyping can reinforce local agency but also existing elite power structures (Kimbell and Bailey Citation2017). These embedded rationalistic discourses effectively ignore dimensions of unexpected change, placing the use of design for policy within a normative positioning. This does not adequately account for or enable diverse and often divergent public positions, collaborative partnerships or cooperation, co-production and co-governance between citizens, public authorities and stakeholders (Elstub and Escobar Citation2019).

That said, Reiter-Palmon and Robinson (Citation2009) propose creative individuals generally present high problem construction capabilities, valuable in developing public policies tackling complex societal issues, e.g. through the practices of framing. In recent work on framing as a creative process, Van der Bijl-Brouwer (Citation2019) focuses on complex policy-making processes, and more recently, Lee (Citation2020) on when frames cannot achieve desired outcomes. In addition, Kolko (Citation2010) notes how purposeful reframing shifts the mainstream frame allowing a new perspective. Nevertheless, whilst Dorst (Citation2011) noted that dealing with complex problems has advanced practices within the design disciplines, such as frame creation, through which a problematic situation can be tackled from an original standpoint, others have explained how these concepts of complexity and framing have masked the political at work in design framing (Rein and Schön Citation2013; Van der Bijl-Brouwer Citation2019; Lee Citation2020; Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria Citation2022).

To this end, recently, design scholars have rearticulated frames as social phenomena (Agid, Citation2012; Keshavarz and Maze Citation2013; Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria Citation2022), taking positions on issues bound by discourses and subjectivities within a context, and intimately related to ideology. This emphasizes how claims to knowledge, belief systems and values involve various standpoints (Benford and Snow Citation2000; Chong and Druckman Citation2007). Thus, how we understand and present an issue affects the likelihood of it gaining support. In social movement studies and political theory, frames are formed through “group-based social interactions” (Benford and Snow Citation2000), public debate, political action, and dialogic social processes as part of democratic politics (Aklin & Urpelainen, Citation2013). When values, beliefs, goals, and ideology are congruent and complementary, frame alignment becomes possible—in turn, misalignment implies failure (Benford and Snow Citation2000). Taking design frames as material practices that are inherently political (Prendeville and Syperek Citation2021; Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria Citation2022) allows for problematizing reductive understandings of frame failure. Chong and Druckman (Citation2013) argue alternative frames influence issues’ structuring and evaluation. Minor changes, or altered wordings, have large effects, putting into doubt legitimate representation through frames (e.g. Black Lives Matter). Still, this overlooks how the political economy of corporate media, for example, can control public opinion through monopolistic practices (e.g. climate denial messaging) (Dunlap and McCright Citation2011). Following Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria (Citation2022), frames and counter-frames involve contextual and historically contingent socio-material processes and practices. Counter-frames are responses to established frames and contest existing understandings of society expressed through common public discourses and political debates.

As Le Dantec (Citation2016) notes, frames can reinforce entrenched structures, giving voice to specific publics. Thus, designing publics has been a prominent concern within the field of PD (Le Dantec Citation2016; Lindström and Ståhl Citation2020; Marres Citation2016; Björgvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren Citation2012; Dixon Citation2020). Yet, while this literature, such as through the work of Björgvinsson and colleagues (Björgvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren Citation2012) engages deeply with power dynamics, there is a lack of consideration of these issues, their effects and outcomes, within the design for policy literature thus far.

3. Interfacing government and grassroots-led policy approaches

Our understanding of the integration of design in policymaking is shaped by the touchpoints between the policy process and grassroots activities. Whilst we based our depiction of the policymaking process on the literature, the grassroots stance draws on, amongst others, the seminal work of Saul Alinsky (e.g. Obama’s grassroots campaigning, Extinction Rebellion). Direct engagement with various SI through interviews, workshops, and community organizing training, also informed this paper.

Within this methodological approach, we are mindful the conceptualization we arrive at is informed by groups, some of whom are major institutionalized actors and others who are close to government, albeit still involved in lobbying and mobilizing for change in off-street contexts.

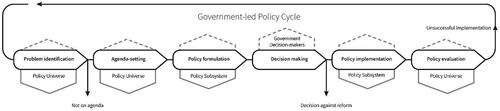

3.1. The government-led policymaking process

The design for policy literature has been heavily influenced by Howlett and colleagues’ (Howlett, Ramesh, and Perl Citation2009) policy cycle. This models a staged process to identify actors and their actions, process bottlenecks, and analytical tools (Howlett and Giest Citation2013). Despite its criticisms, the policy cycle has been extensively used in design for policy scholarship (Junginger Citation2017; Vaz and Prendeville Citation2019; Villa Alvarez, Auricchio, and Mortati Citation2022) ().

Figure 1. The government-led policy cycle, adapted from Howlett, Ramesh, and Perl (Citation2009), Dye (Citation2013), and Grindle and Thomas (Citation1991).

Howlett, Ramesh, and Perl (Citation2009) suggest a bi-dimensional process (technical and political) of applied problem-solving, where constrained social actors attempt to tie policy goals with policy means. This bridges the epistemic gap between policymaking and design, understanding the latter as problem-solving—a popular design thinking conceptualization (Kimbell Citation2011). However, whereas the technical dimension is seen as a rational quest for the optimal relationship amongst goals and tools, the political implies stakeholders may disagree on what is a suitable solution, or even what constitutes a public problem (Howlett, Ramesh, and Perl Citation2009).

Other models, such as Dye’s (Citation2013), see problem identification as a distinct stage preceding agenda-setting. Dye argues policy problems are identified through the demand for government action from, e.g. public opinion, mass media, interest and pressure groups, and citizen initiatives. During agenda-setting, political and power elites, the mass media, and other stakeholders focus their attention on specific problems to determine which will be addressed. Similarly, in Kingdon’s (Citation1984) streams model, policy issues are recognized and taken on board when a solution becomes available within a timely political climate. A window of opportunity opens when the three streams of problem (“what is going on?”), policy (“what can we do about it?”), and politics (“what can we get support for?”) converge (Colebatch Citation2005). However, Barbehön, Münch, and Lamping (Citation2015) note collective sense-making is not central to Kingdon’s approach, also largely absent in the design for policy literature.

Still, critical policy studies suggest policymaking is a discursive struggle around framing of problems and societal understanding and shared meanings motivating policy responses around issues (Fischer and Gottweis Citation2012), questioning the assumption that policy problems exist in a pre-given “neutral” reality (Barbehön, Münch, and Lamping Citation2015). Howard (Citation2005) criticizes the policy cycle as ignoring value-laden political processes, while Barbehön, Münch, and Lamping (Citation2015) suggest problem definitions are discursive processes shaping the political world, with agenda-setting attributing responsibilities to specific political actors or institutions within larger policy-making processes.

The decision-making stage defines the politically preferred course of action (or its absence) (Howlett, Ramesh, and Perl Citation2009). While Howlett, Ramesh, and Perl (Citation2009) note the limited number of actors with authority to take binding public decisions, excluded actors are likely to want to engage with, influence or even coerce those in power to adopt or avoid certain choices. Political negotiation outweighs rational debates, and neutrality or competence as an unavoidable and inherent process characteristic (Howlett and Giest Citation2013). Schneider et al. (Citation2013) warns against mistaking this stage as a “benign process of efficient decision-making, [since] cognitive biases may operate at the expense of policy that would serve democratic ends” (217), speaking again to the importance of frames.

In other representations, such as Grindle and Thomas (Citation1991) phase model, critical choices relate to how a proposed reform gets on the agenda, how a decision is made, and how the new policy is (successfully or unsuccessfully) implemented. However, van Buuren and Gerrits (Citation2008) highlight policy processes evolve in non-linear ways, resulting in strings of subsequent policy decisions, as the result of three co-evolving tracks of fact-finding, framing, and will-forming (Teisman and van Buuren Citation2013). Their tracks model emphasizes the role of normative and subjective perceptions (frames) of the actors involved at this stage of the policy-making process.

In summary, we observe three interrelated shortcomings in the current conception of design for policy. Firstly, the design for policy scholarship seldom engages with this broader literature schematizing the policy process beyond the work of Howlett’s model. Secondly, it has been limited to deploying design expertise and capabilities from within the government as an “organizational resource” (Kimbell Citation2011) when a public problem has entered the policy agenda. Thirdly, the discussion about the meaning construction of public problems and the corollary notion of problem reframing—so present within the design literature (Dorst and Cross Citation2001; Dorst Citation2015)—largely relates to policy problems as identified and framed from an internal government perspective. In this paper, we break from that standpoint on the basis that design can be implicated in the making of policies over and above this intra-governmental position.

3.2. Modeling a policy from below process

Engagement in policy from below can involve, among others, activism, community organizing, and advocacy, and we aim here to understand their commonalities. Jenkins (Citation1987, 297) defines policy advocacy as “any attempt to influence the decisions of an institutional elite on behalf of a collective interest” in what Reid (Citation2000) describes as “Government-centred advocacy,” the goal being to adopt a desired policy change (Reisman, Gienapp, and Stachowiak Citation2007).

Policy advocacy involves a wide range of activities, from “public education and influencing public opinion; research for interpreting problems and suggesting preferred solutions; constituent action and public mobilizations; agenda setting and policy design; lobbying; policy implementation, monitoring, and feedback; and election-related activity” (Reid Citation2000, 1). Generally, however, it involves “negotiating and mediating a dialogue through which influential networks, opinion leaders, and ultimately, decision-makers take ownership of the ideas, evidence, and proposals being advocated and, if successful, subsequently act upon them in the desired way” (Young and Quinn Citation2012, 26). Whilst Saul Alinksy’s model has been hugely influential in recent decades (Miller Citation2010), no one source is able to give a full account of all the types of activities SI can apply to impact the policy process (Reid Citation2000), with different groups pursuing different strategies depending on their ideological positions and political goals. For instance, Alinsky’s model has been critiqued for its depoliticizing focus on pragmatic single issues that institutionalize social change (Bretherton Citation2012). Yet, Turrall (Citation2007) stipulates that affecting policy change requires a belief that change is technically and politically feasible, and access to policymakers and stakeholders with direct impact on policymaking, together with suitable mechanisms, knowledge and will for effecting change. Moreover, for the success of a campaign, access to key stakeholders and timing are seen as crucial to maximize the opportunity for policy reform (Turrall Citation2007). Still, new policies on newly regulated aspects of social life may also be a focal concern. This is prescient given a bourgeoning interest in the confluence of design for policy and legal design, the leveraging of design within the expansion of a “legal state,” which is not unequivocally desirable (Renton Citation2022). Such an acknowledgement reveals the innate politics in the invocation of any design for policy approach, as design can be used in the case to reduce the legal state inasmuch as it can be leveraged in institutionalized legal design practice.

This speaks to the notion of concurrent streams presented by Kingdon (Citation1984), where “problem,” “policy,” and “politics” need to converge in an opportunity window. Similarly, advocates know that since different audiences may react differently, communication of policy messages must be precisely targeted to achieve desired impact (Turrall Citation2007). This implicitly acknowledges the discursive nature of public policymaking, and speaks to Stone’s (Citation1989) claim that to gain support, political actors deliberately portray problem definition as image-making linked to cause, blame, and responsibility—the conditions, difficulties, or issues thus do not have inherent properties to enable decision-making. Therefore, it is the ability—to wit, occupying a locus of power—to promote a persuasive narrative that allows influencing the policy debate (Hajer Citation1995), noting the intentional framing of public problems can have distinct impacts for advocates and various publics alike.

Advocates also promote policy change on behalf of a collective interest. To certain groups, this is undesirable, as advocates retain the power to decide which perspectives will be legitimized and which will not. In other words, advocates seek local “informants,” not equal “participants” (Schutz and Sandy Citation2011, 36). Bolton (Citation2017) describes community organizing in a series of discrete steps of identifying what communities care about (“what makes people angry”); building relational power based on common self-interest; breaking the big problems of the community down into specific issues, or “issue cutting;” and lastly, developing and executing specific actions to force decision-makers to address those issues.

Whilst some organizers identify a three-stage cycle of research, action, and evaluation in each campaign (Bolton Citation2017), the literature is not categorical about a generalized policy from below process. Many campaigners start by researching the main problems affecting the community, followed by internal and external actions. The former refers to activities through which communities prioritize different problems, determine the specific issues to focus on, and define the tactics to implement. The latter implies the outward-looking activities aiming at getting government actors to acknowledge the community and recognize their issue/s whilst establishing a relationship where negotiation can take place, eventually leading to some form of agreement (Bolton Citation2017). Finally, organizers evaluate the resulting policy and their campaign outcomes, focusing on the lessons learned for future action.

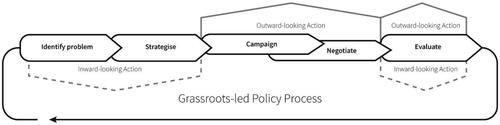

From our analysis, we propose a policy from below process that portrays the main stages SI might follow in attempts to produce policy change. In , we have synthesized core activities of policy advocacy and community organizing into five phases from the experience of organizations consulted and observed for this study and the literature. This partially mirrors the policy cycle but from a grassroots perspective.

This five-stage process begins with identifying a problem that requires government intervention. Secondly, it focuses on strategising, where SI design actions to pressure power structures. Thirdly, the various actions previously devised start taking place. This would typically occur and evolve until the campaign’s “ask” has been acknowledged and the specific public problem added to the government’s policy agenda. Next, the negotiations between the SI and government actors aim at ensuring (1) the proposed framing for the policy issue is accepted; (2) the proposed solution is accepted; (3) the resulting policy is implemented in a way that ameliorates the original problem. Lastly, the campaign is evaluated. Still, whilst this is presented as a clean-cut process, campaigns may be redirected, collapse for political or other reasons (e.g. absence of leadership figures sympathetic to issues), subside as campaigners lose momentum, or indeed may be squashed by effective or more powerful opponents. Often, campaigns take decades to achieve their goals, which is out of sync with a given government’s circumscribed timeline and agenda.

From this perspective, SI engaging in design for policy from below introduce design expertise to identify and make sense of the public problems affecting communities and diverse social groups, construct political positionings, visualize preferred futures for their communities, and formulate specific asks to governments while ideating potential solutions to achieve their envisioned futures. In the next section, we consider the interplay and touchpoints between this policy from below perspective with the government-led process.

4. A framework for “design for policy from below”

Previously, we considered various sequential representations of the public policymaking and grassroots engagement processes. Such frameworks are necessarily reductive and cloak how discrete “stages” in practice interweave or collapse in ongoing complex social interactions. Still, they can be helpful heuristics for gaining an analytical understanding of policymaking (Dye Citation2013) and more so to offer pragmatic frameworks for advocates.

In the design literature, the policymaking process has typically been conveyed as a succession of decisions to progress a public issue from entering the agenda to developing a measure that addresses it. For SI aiming to influence the policy process, the key is to have an impact on that series of decisions usually under the control of political elites. This implies influencing the decision to include an issue on the government’s agenda and to act upon it, together with having the ability and will to address it and monitor and evaluate its implementation and results.

The framework presented in allows for the analysis of the two cycles in parallel, evidencing the correlation between their stages and the touchpoints at which SI should exert pressure to achieve policy change.

The touchpoints presented in correspond to specific activities carried out by SI. In particular, the outward-looking activities relate to those conducted in campaigning for the adoption of a specific frame and a policy option that addresses it, the negotiation process to impact the decision-making over a policy option, and the particularities of its implementation. Public policy is a government prerogative (Dye Citation2013); thus, the actions of SI should focus on gaining the government’s attention and persuading it to adopt specific courses of action. Following Grindle and Thomas (Citation1991) phase model, bottom-up activities should target specific critical points at the agenda-setting, decision-making, and implementation stages to guarantee their success. Naturally, the outcomes of these can be positive for the SI’s objectives or, respectively, not to include the issue on the agenda, opposed or different to the proposed policy reform, or the unsuccessful implementation of the policy (see ). In each case, SI can aim at increasing their campaigning and negotiation efforts or re-strategise, which, depending on the case, might imply developing a new campaign, new policy option, or new issue framing altogether. This speaks back to Teisman and van Buuren (Citation2013) notion of co-evolving tracks of fact-finding, framing, and will-forming, which may take several iterations before succeeding.

Likewise, looking through Kingdon’s (Citation1984) streams model lens, SI should develop campaigns that foster the conditions to achieve a convergence of the “problem,” “policy,” and “politics” streams to create and exploit an opportunity window. Design for policy from below plays a role in this process by contributing to the purposeful framing of issues that can leverage the SI’s chances of introducing the public problem to the policy agenda whilst developing policy solutions to tackle it. Thus, addressing two of the three streams Kingdon refers to, with the third one—politics—being an intrinsic part of the campaigning objectives via the generation of a favorable socio-political environment.

During the evaluation, both the government and the SI assess their results. Whilst both sides evaluate the new policy in terms of how it addresses the public problem, the SI also review their campaign regarding how successfully it produced the desired change.

Whilst it is recognized that public policymaking is essentially a design task (Johnson and Cook Citation2014; Peters, Citation2018), this is not necessarily the case with policy advocacy, community organizing, or other forms of social mobilization. We argue, however, that many of the activities described in the policy from below process are fundamentally design activities. Moreover, in interfacing these processes, we identify two main phases that, although occurring recursively and out of phase in each cycle, are clearly linked to the practice of design—namely, sense-making and meaning-making.

4.1. Sense-making

Understood as the ability to make sense of an ambiguous situation so we can act in it, from a bottom-up perspective, we refer to sense-making as the process through which SI interpret the situation and context of their communities to identify one or more problems affecting them that would require governmental attention. In this context, sense-making occurs during the early phases of problem identification, with different organizations conducting these activities in diverse ways according to their ethos. For some community organizers, this means carrying out a “listening campaign” (Bolton Citation2017) to discover what people care about through first-hand engagement. This is in line with Mintrom and Thomas (Citation2018), who note deep knowledge of the contexts and the experiences of the people affected are crucial inputs for the development of public policies and services. According to Sandberg and Tsoukas (Citation2015) drawing on Weick (Citation1979), sense-making is a social, retrospective, grounded on identity, narrative, and enactive process crucial for social mobilization since it is only when their causes converge that a group of individuals becomes organized.

Likewise, sense-making is another core design activity where information is interpreted and meaning assigned, individually and collectively (Cross Citation2001; Allio Citation2014) in processes mediated by culture, experience, prevailing narratives, and knowledge systems (Prendeville and Koria Citation2022). In addition, Kolko (Citation2010) sees design synthesis as an abductive sense-making process of manipulating, organizing, and filtering data to produce information and knowledge. Moreover, the process of design synthesis—used by designers to create new products, services, and systems—can essentially be described through the sense-making and framing phenomena (Kolko, Citation2010). Therefore, the sense-making process through which SI identify problems is an organizing effort as well as an early stage in the design process, helping mobilize people and offering an initial frame to develop a campaign ask.

Conversely, in the top-down design for policy approach, sense-making largely takes place at the policy formulation stage, where policy designers engage in practices of reframing “as a method of shifting semantic perspective in order to see things in a new way” (Kolko, Citation2010, 23) to develop innovative policy options based on the opportunities arising (e.g. potential political leverage, political pet projects). Yet, we argue, these new frames are circumscribed by the organizational narrative and the political mandate of the government bodies developing the policy. Furthermore, from a top-down perspective, design for policy introduces design as a mode of inquiry aiming to uncover the root causes of societal issues whilst designing alternatives to improve the conditions of the people affected by those problems (Vaz Citation2021). In doing so, it adopts a micro-level perspective (i.e. it is concerned with individual responses to specific policies and public problems). A similar point has been recognized by Mortati (Citation2019), who asserts design scholars have mostly been interested in a micro-level analysis (primarily around design skills and tools for policy implementation), whilst policy scholars are typically concerned with macro-level analysis. Although distinct from Mortati’s, our model looks at the meso-level by focusing not on the individual but on larger grassroots collectives as they interact and negotiate with government structures. In doing so, and by rejecting the technocratic value-free stance on design for policy, we subscribe to a discursive and social understanding of the policy process.

4.2. Meaning-making

Whereas sense-making is about making sense of the external world, meaning-making is about the process of producing new interpretations of the world. Meaning is ascribed through the construction of narratives (Ejsing‐Duun and Skovbjerg Citation2019), especially the micro-narratives, or small stories, created by people to reflect their everyday experiences. These are useful in understanding and exploring social patterns of cognition and perceptions of what is considered public truth. This framing process (partly explicit and deliberate and partly implicit and unconscious) is dynamic until a particular identified frame gains currency with political actors. This implies the need for the purposeful design of frames for public problems (from a grassroots perspective, often counter-frames that oppose the status-quo and hegemonic view on a particular issue) to be introduced first in the public discussion and subsequently in the government agenda. Amongst other elements, these materialize through campaign manifestos, slogans, and communication strategies—instrumental in designing publics. This speaks to the notion of design as a practice of cognitive and semiotic interfacing, enabling the reconstruction of intended meanings by receivers (Kazmierczak Citation2003). Moreover, as part of the meaning-making phase, SI design policy alternatives addressing identified problems through preferred scenarios of likely outcomes, as well as campaign strategies to spearhead their ask.

Notably, the frames created will condition policy alternatives. Likewise, these alternatives can be well-delimited or loosely defined, broadly indicating the policy intent. In addition, within the universe of possible policies responding to a public problem, both the government and the SI will find subsets of mutually acceptable policies. When the overlap between the government and SI’s acceptable policies is significant there is ample space for negotiation. Moreover, within the acceptable policies for each, government and SI will find options that suit their issue framings. Alternatively, each side might be able to find policy options falling outside their framing but still acceptable. Conversely, when either side is campaigning for a well-defined policy or their framings are significantly at odd, the chances of a negotiated agreement reduce. This highlights the importance of strategic issue framing as a central meaning-making activity.

To date, the design literature has been chiefly concerned with sense-making and meaning-making as cognitive processes through which designers make sense of a problematic situation to produce innovative solutions, and less so with the produced frames as design objects. Moreover, sense-making and meaning-making are seldom addressed in the design for policy literature, though these, we argue, are fundamental to understanding the political dimension of integrating design in public policymaking.

In sum, our proposed framework offers a lens through which examining the negotiation-based dynamics and political plays influencing government policymaking processes, as well as a conceptualization of the interactions grassroots activists could strategise around when aiming to affect policy outcomes.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have developed an understanding of how design for policy can be integrated into grassroots practices in support of collective action. In doing this, we proposed a design for policy from below approach that moves from an intra-governmental lens to a negotiated exchange between social actors and government. This implies simultaneously understanding policy as a site of equilibrium in the power struggle of diverse groups and as the result of political activity. Central to this model, is the notion of framing, which in this approach takes on the role of design for policy at informing the strategic collective action of social innovators to increase political support for their asks whilst leveraging public actions to pressure power structures in acknowledging and adopting specific policy frames and means. Social innovators engage in identifying problems, strategising, campaigning for change, negotiating with government authorities and other relevant stakeholders, while also evaluating results. We acknowledge such frameworks may be reductive and cloak the realities of political context and skill at work in the making of any policy change, but we also find that campaigners and activists need and actively seek out pragmatic frameworks that can be used to coordinate activities and practices.

In this sense, our proposed model makes visible the touchpoints between the government-led and grassroots efforts to effect policy change, highlighting the negotiated and often dissensual nature of the public policymaking process. Likewise, it is based on the idea that in a functioning liberal democracy, it is not a matter of either/or between government and grassroots-led policymaking but rather a negotiation-based dynamic where the framing of public problems takes central stage.

Although the presented model has been discussed with a large community organizing group in the UK, further research is needed for its empirical validation. Lastly, as part of this positioning paper, we recognize the need for developing specific research that informs and strengthen the practice of design for policy from below to better equip grassroots movements engaging in these activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to warmly thank their research partners from the UK, Brazil, Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zambia for their in-kind support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agid, S. 2012. “Worldmaking: Working Through Theory/Practice in Design.” Design and Culture 4 (1): 27–54.

- Aklin, M., and J. Urpelainen. 2013. “Political Competition, Path Dependence, and the Strategy of Sustainable Energy Transitions.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (3): 643–658.

- Allio, L. 2014. Design Thinking for Public Service Excellence. Singapore: UNDP Global Centre for Public Service Excellence.

- Asenbaum, H., and F. Hanusch. 2021. (“De) Futuring Democracy: Labs, Playgrounds, and Ateliers as Democratic Innovations.” Futures 134: 102836. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2021.102836.

- Barbehön, M., S. Münch, and W. Lamping. 2015. “Problem Definition and Agenda-Setting in Critical Perspective.” In Handbook of Critical Policy Studies, edited by F. Fischer, D. Torgerson, A. Durnová, and M. Orsini, 241–258. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Benford, R. D., and D. A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 611–639. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611.

- Björgvinsson, E., P. Ehn, and P.-A. Hillgren. 2012. “Agonistic Participatory Design: Working With Marginalised Social Movements.” CoDesign 8 (2–3): 127–144. doi:10.1080/15710882.2012.672577.

- Bolton, M. 2017. How to Resist: Turn Protest to Power. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Bretherton, L. 2012. “The Political Populism of Saul Alinsky and Broad Based Organizing.” The Good Society 21 (2): 261–278. doi:10.5325/goodsociety.21.2.0261.

- Chong, D., and J. N. Druckman. 2007. “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 103–126. [Database] doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054.

- Chong, D., and J. N. Druckman. 2013. “Counterframing effects.” The Journal of Politics 75 (1): 1–16.

- Colebatch, H. K. 2005. “Policy Analysis, Policy Practice and Political Science.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 64 (3): 14–23. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8500.2005.00448.x.

- Cross, N. 2001. “Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline Versus Design Science.” Design Issues 17 (3): 49–55. doi:10.1162/074793601750357196.

- Dixon, B. S. 2020. Dewey and Design. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Dixon, B., L. S. McHattie, and C. Broadley. 2021. “The Imagination and Public Participation: A Deweyan Perspective on the Potential of Design Innovation and Participatory Design in Policy-Making.” CoDesign, 1–13.

- Dorst, K. 2011. “The Core of ‘Design Thinking’and Its Application.” Design Studies 32 (6): 521–532. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006.

- Dorst, K. 2015. Frame Innovation: Create New Thinking by Design. London: MIT press.

- Dorst, K., and N. Cross. 2001. “Creativity in the Design Process: Co-Evolution of Problem–Solution.” Design Studies 22 (5): 425–437. doi:10.1016/S0142-694X(01)00009-6.

- Dunlap, R. E., and A. M. McCright. 2011. “Organized Climate Change Denial.” In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society, edited by J. S. Dryzek, R. B. Norgaard, and B. Schlosberg, 144–160. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Dye, T. R. 2013. Understanding Public Policy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Ejsing‐Duun, S., and H. M. Skovbjerg. 2019. “Design as a Mode of Inquiry in Design Pedagogy and Design Thinking.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 38 (2): 445–460. doi:10.1111/jade.12214.

- Elstub, S., and O. Escobar. 2019. Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fischer, F., and H. Gottweis. 2012. The Argumentative Turn Revisited: Public Policy as Communicative Practice. London: Duke University Press.

- Fry, T. 2008. “The Gap in the Ability to Sustain.” Design Philosophy Papers 6 (1): 101–110. doi:10.2752/144871308X13968666267275.

- Giraldo Nohra, C., A. Pereno, and S. Barbero. 2020. Systemic Design for Policy-Making: Towards the Next Circular Regions. Sustainability 12: 4494.

- Grindle, M. S., and J. W. Thomas. 1991. Public Choices and Policy Change: The Political Economy of Reform in Developing Countries. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hajer, M. A. 1995. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Howard, C. 2005. “The Policy Cycle: A Model of Post‐Machiavellian Policy Making?” Australian Journal of Public Administration 64 (3): 3–13.

- Howlett, M. 2014. “From the ‘Old’ to the ‘New’ Policy Design: Design Thinking Beyond Markets and Collaborative Governance.” Policy Sciences 47 (3): 187–207. doi:10.1007/s11077-014-9199-0.

- Howlett, M., and S. Giest. 2013. “The Policy-Making Process.” In Routledge Handbook of Public Policy, edited by E. Araral, S. Fritzen, M. Howlett, M. Ramesh, and X. Wu, 17–28. New York: Routledge.

- Howlett, M., M. Ramesh, and A. Perl. 2009. Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Huybrechts, L., H. Benesch, and J. Geib. 2017. “Co-design and the Public Realm.” CoDesign 13 (3): 145–147. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1355042.

- Jenkins, C. J. 1987. “Nonprofit Organizations and Policy Advocacy.” In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, edited by W. W. Powell, 297. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Johnson, J., and M. Cook. 2014. “Policy Design: A New Area of Design Research and Practice.” In Complex Systems in Design and Management, edited by M. Aiguier, F. Boulanger, D. Krob, and C. Marchal, 51–62. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Julier, G. 2011. Political Economies of Design Activism and the Public Sector. Helsinki: Aalto University.

- Julier, G. 2017. Economies of Design. London: SAGE Publications.

- Junginger, S. 2017. Transforming Public Services by Design. Oxon: Routledge.

- Kazmierczak, E. T. 2003. “Design as Meaning Making: From Making Things to the Design of Thinking.” Design Issues 19 (2): 45–59. doi:10.1162/074793603765201406.

- Keshavarz, M., and R. Maze. 2013. “Design and Dissensus: Framing and Staging Participation in Design Research.” Design Philosophy Papers 11 (1): 7–29. doi:10.2752/089279313X13968799815994.

- Kimbell, L. 2011. “Rethinking Design Thinking: Part I.” Design and Culture 3 (3): 285–306. doi:10.2752/175470811X13071166525216.

- Kimbell, L., and J. Bailey. 2017. “Prototyping and the New Spirit of Policy-Making.” CoDesign 13 (3): 214–226. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1355003.

- Kimbell, L., and L. Vesnić-Alujević. 2020. “After the Toolkit: Anticipatory Logics and the Future of Government.” Policy Design and Practice 3 (2): 95–108. doi:10.1080/25741292.2020.1763545.

- Kingdon, J. W. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston: Longman Pub Group.

- Kolko, J. 2010. “Abductive Thinking and Sensemaking: The Drivers of Design Synthesis.” Design Issues 26 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1162/desi.2010.26.1.15.

- Kolko, J. 2010. “Sensemaking and Framing: A Theoretical Reflection on Perspective in Design Synthesis.” In Design and Complexity - DRS International Conference 2010. Montreal, Canada: DRS Digital Library.

- Le Dantec, C. A. 2016. Designing Publics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lee, J.-J. 2020. “Frame Failures and Reframing Dialogues in the Public Sector Design Projects.” International Journal of Design 14 (1): 81–94.

- Lewis, J. M., M. McGann, and E. Blomkamp. 2020. “When Design Meets Power: Design Thinking, Public Sector Innovation and the Politics of Policymaking.” Policy & Politics 48 (1): 111–130. doi:10.1332/030557319X15579230420081.

- Lindström, K., and Å. Ståhl. 2020. “Politics of Inviting: Co-articulations of Issues in Designerly Public Engagement.” In Design Anthropological Futures, edited by R. C. Smith, K. T. Vangkilde, M. G. Kjaersgaard, T. Otto, J. Halse, and T. Binder, 183–197. London: Routledge.

- Marres, N. 2016. Material Participation: Technology, the Environment and Everyday Publics. Basingstoke, UK: Springer.

- Miller, M. 2010. “Alinsky for the Left: The Politics of Community Organizing.” Dissent 57 (1): 43–49.

- Mintrom, M., and M. Thomas. 2018. “Improving Commissioning Through Design Thinking.” Policy Design and Practice 1 (4): 310–322. doi:10.1080/25741292.2018.1551756.

- Mortati, M. 2019. “The Nexus between Design and Policy: Strong, Weak, and Non-Design Spaces in Policy Formulation.” The Design Journal 22 (6): 775–792. doi:10.1080/14606925.2019.1651599.

- Peters, B. G. 2018. Policy Problems and Policy Design. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Peters, B. G. 2018. “The Challenge of Policy Coordination.” Policy Design and Practice 1 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/25741292.2018.1437946.

- Prendeville, S., and M. Koria. 2022. “Design Discourses of Transformation.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 8 (1): 65–92.

- Prendeville, S., and P. Syperek. 2021. “Counter-Framing Design: Politics of the ‘New Normal’.” In Nordes 2021: Matters of Scale, 104–113. Kolding: Design School Kolding.

- Prendeville, S., P. Syperek, and L. Santamaria. 2022. “On the Politics of Design Framing Practices.” Design Issues 38 (3): 71–84. doi:10.1162/desi_a_00692.

- Reid, E. J. 2000. “Understanding the Word “Advocacy”: Context and Use.” Structuring the Inquiry into Advocacy 1(1–7).

- Rein, M., and D. Schön. 2013. “Reframing Policy Discourse.” In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning, edited by F. Fischer and J. Forester, 145–166. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Reisman, J., A. Gienapp, and S. Stachowiak. 2007. A Guide to Measuring Advocacy and Policy. Baltimore, MD: Organisational Research Services.

- Reiter-Palmon, R., and E. J. Robinson. 2009. “Problem Identification and Construction: What Do We Know, What Is the Future?” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 3 (1): 43–47. doi:10.1037/a0014629.

- Renton, D. 2022. Against the Law: Why Justice Requires Fewer Laws and a Smaller State. London: Repeater.

- Sandberg, J., and H. Tsoukas. 2015. “Making Sense of the Sensemaking Perspective: Its Constituents, Limitations, and Opportunities for Further Development.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 36 (S1): S6–S32. doi:10.1002/job.1937.

- Schneider, A., 2013. “Policy Design and Transfer.” In Routledge Handbook of Public Policy, edited by E. Araral, S. Fritzen, M. Howlett, M. Ramesh, and X. Wu, 217–228. New York: Routledge.

- Schutz, A., and M. Sandy. 2011. Collective Action for Social Change: An Introduction to Community Organizing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Smith, G. 2009. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Stone, D. A. 1989. “Causal Stories and the Formation of Policy Agendas.” Political Science Quarterly 104 (2): 281–300. doi:10.2307/2151585.

- Teisman, G. R., and A. van Buuren. 2013. “Models for Research into Decision-Making Processes: On Phases, Streams, Rounds and Tracks of Decision-Making.” In Routledge Handbook of Public Policy, edited by E. Araral, S. Fritzen, M. Howlett, M. Ramesh, and X. Wu, 299–319. New York: Routledge.

- Telier, A. 2011. Design Things. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Turrall, S. 2007. Effective Policy Advocacy. London: UK Department for International Development.

- van Buuren, A., and L. Gerrits. 2008. “Decisions as Dynamic Equilibriums in Erratic Policy Processes: Positive and Negative Feedback as Drivers of Non-Linear Policy Dynamics.” Public Management Review 10 (3): 381–399. doi:10.1080/14719030802003038.

- van Buuren, Arwin, Jenny M. Lewis, B. Guy Peters, and William Voorberg. 2020. “Improving Public Policy and Administration: Exploring the Potential of Design.” Policy & Politics 48 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1332/030557319X15579230420063.

- Van der Bijl-Brouwer, M. 2019. “Problem Framing Expertise in Public and Social Innovation.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 5 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1016/j.sheji.2019.01.003.

- Vaz, F. 2021. Policy Innovation by Design: Understanding the Role of Design in the Development of Innovative Public Policies. London: Loughborough University.

- Vaz, Federico, and Maria Ferreira. 2021. “Assessing Design Approaches’ Political Role in the Public Sector.” Journal of Design Research 19 (4/5/6): 197–212. doi:10.1504/JDR.2021.124213.

- Vaz, F., and S. Prendeville. 2019. “Design as an Agent for Public Policy Innovation.” Conference Proceedings of the Academy for Design Innovation Management 2 (1): 143–156. doi:10.33114/adim.2019.06.231.

- Villa Alvarez, D. P., V. Auricchio, and M. Mortati. 2022. “Mapping Design Activities and Methods of Public Sector Innovation Units Through the Policy Cycle Model.” Policy Sciences 55 (1): 89–136. doi:10.1007/s11077-022-09448-4.

- Weick, K. E. 1979. The Social Psychology of Organizing. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Whicher, A. 2020. AHRC Design Fellows Challenges of the Future: Public Policy. London: Arts and Humanities Research Council.

- Young, E., and L. Quinn. 2012. Making Research Evidence Matter. Budapest: Open Society Foundations.