Abstract

The appetite for design in local government saw a rise in the late 2000s with the global financial crisis and the resulting economic austerity that required local government services to innovate. This appetite has been exacerbated by the awakening to the global climate emergency and inclusion of action plans to reduce carbon emissions at a local scale; and of course, the global health crisis caused by Covid-19. Local governments are responsible for responding to these unprecedented challenges ensuring continued and equitable access to public services for residents. Yet, design for local public policy is a nascent field of practice. This paper presents an approach to design for local policy characterized by “world-building preferable futures through Critical Service Design” which proposes a novel approach to participatory place-based local policymaking. This design-led methodology has been developed through theory and practice, informed by critical reflection on the successes and shortcomings of collaborative design practice research with public servants in England and developed iteratively at Service Futures Lab, as part of the postgraduate service design curriculum at London College of Communication. The paper aims to contribute to a growing a body of academic literature on design for local governance, supporting collaboration between design education and local government and the development of dedicated training programmes on design for policy.

1. Introduction

The last two decades have seen a growing use of design in public sector organizations for communicating, implementing, informing, and envisioning future policies, products, and services (Junginger Citation2014). The recognition that traditional problem-solving approaches fail to deal with highly complex challenges has led to an interest for new approaches to local governance; yet the application of design to public policy is an emergent field (Bason Citation2017; Kimbell et al. Citation2022; Mortati, Schmidt, and Mullagh Citation2022). Whilst scholars call for radical innovation in public sector, two decades of ongoing crises have left local governments to face highly complex challenges with ever diminishing resources. As a response, many local governments have pursued efficiency: cost cutting to deliver “more for less” (Bartlett Citation2009). Thorpe and Rhodes argue that favoring efficiency, local governments have lost “the space to learn through failure without critical injury to the system” lacking the “ability to experiment, innovate and effectuate” (Citation2018, 62). Malpass and Salinas (Citation2020) reviewed the innovative capacity of design research undertaken in the public service context in the UK, identifying challenges of capacity and capability of public sector organizations to embrace design-led innovation. Moreover, the underdevelopment of dedicated training programmes on design for policy in higher education, documented in the British context by Whicher (Citation2020), results on a shortage of designers with the necessary understanding of government systems to apply design methodologies to improve policymaking (Kimbell and Bailey Citation2017).

2. Context of the research

In this paper I present a design-led methodology for policy innovation at local level. It is a response to my role as a design practice researcher in local government contexts and educator, seeking to create opportunities for experimentation, exploring how design research, education and knowledge exchange might contribute to public and social innovation. The research is informed by my design practice research which is co-produced with civil servants in local governments in England. It presents a collaborative design-led methodology to inform local policy that has been developed through extensive experimentation with international, national and local public administrations in the context of Service Futures Lab and the postgraduate course on service design at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London (Salinas Citation2018, Citation2021, Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Thorpe et al. Citation2016). In these projects, I am conducting design for local policy as a design practice researcher (Frayling Citation1993; Koskinen et al. Citation2013), actively engaging with local government officers, organizations and residents.

This paper serves a two-fold aim. On the one hand, contributing to a growing body of academic literature on design for local governance by exploring how (Critical Service) Design might innovate local policy making. On the other, seeking to increase local government capacity and capability for innovation by supporting the development of design professionals who are qualified and drawn to public service. To that end, I present an approach to design for local policy characterized by “world-building preferable futures through Critical Service Design” which proposes a novel approach to participatory place-based local policymaking.

The second section frames some of the limitations of linear and problem-based public policy cycles to incorporate design insights. The third section introduces “world-building preferable futures through Critical Service Design” from a theoretical point of view. The fourth section outlines the design-led methodology with the practice of Climate Studio (Salinas, Lang, and Swift Citation2022). The fifth section explores new directions and limitations afforded by this novel practice. I conclude by reflecting on the relevance of the methodology to enhance local policymaking in highly complex scenarios.

2. Limitations of designing for local policy

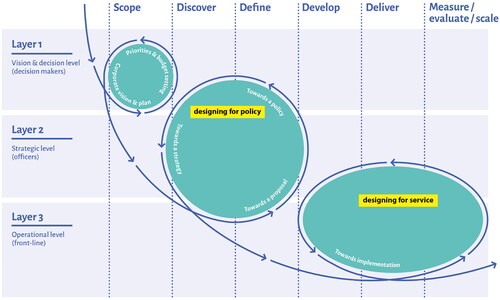

Public policy cycle is traditionally conceptualized as a linear two stage process: firstly, concerned with identifying a policy problem and formulating a policy; secondly, with policy implementation. Design research seeks to articulate public policy design as an integrated and iterative cycle (Junginger Citation2014). In an “anatomy of collaboration between local government and design education,” Thorpe et al. (Citation2017) propose a framework that offers a visual overview of local policy making, outlining local government organizational structure and processes over a typical design process. This visualization was developed to enable collaboration between local government and design education, and it is effective in supporting a shared understanding for public officers and designers, facilitating a conversation to identify where and how design might contribute to local governance:

In the vision and decision level (tier 1) the elected Council (decision-makers) issues a corporate vision, informed by political agendas and data-based evidence, which informs a corporate plan that provides guidance on what and how the vision must be delivered, which in turn demands a strategy for doing so. The strategic level (tier 2) is concerned with (officers) establishing the strategy for designing local government’s policy and services. The operational level (tier 3) is concerned with development and delivery of a proposal (developed in tier 2), typically in the form of services to residents. (Thorpe et al. Citation2017, S4736)

The process depicted in represents a local policy cycle with a linear process going from problem to solution with loops that indicate an interrelation between stages. Mapping my collaborative design practice with local government against this cycle revealed -not surprisingly- that my “design for service” practice was mostly located as bridging strategy and service delivery. The divide between designing for policy and designing for services became palpable when the insights gained through designing for services called for a redefinition of the policy problem that the local government could not provide. In other words, I was experiencing the restrictions of linear problem-solving approaches that limit the use of design to reactive thinking, constituting an obstacle to re-framing public policy “problems” into “opportunities” (Junginger Citation2014; Bason Citation2017). As Bason puts it, “what if the tendency to frame public policy in terms of ‘problem’s is in itself problematic?,” calling for “a shift from a decision-making stance to a future-making stance” (Bason Citation2017, 31). How might design incorporate a future-making stance into local government, when there is so little scope to experiment, innovate and effectuate?

Figure 1. Local policy making cycle, based on Thorpe et al. (Citation2017). Text highlighted in yellow added by the author.

3. Designing preferable futures for local policy

Designers engage with future thinking and the exploration of potential future estates, either in processes that resolve into graphics, products, services, experiences and systems to solve a present need; or that engage explicitly with critical explorations of futures (Evans Citation2010; Pollastri Citation2017). Dune and Raby divide design into two broad categories, Affirmative Design and Critical Design, which are summarized in the a/b manifesto. Affirmative Design is traditional design practice that reinforces the status quo; while Critical Design confronts and critiques traditional design practice, through designs that embody alternative social, cultural, technical or economic values (Dunne and Raby Citation2001, Citation2009). Affirmative Design is problem solving and functional, we can find it in the most common applications of graphic design, industrial design, interaction design, environmental design (Buchanan Citation2001) or service design. Service Design is a human-centred, creative, collaborative, iterative and systematic process applied to the development of services, creating interactions within complex systems in order to co-create value for relevant stakeholders (Sangiorgi and Prendiville Citation2017; Malpass and Salinas Citation2020). Services are complex things. Kimbell and Blomberg (Citation2017) propose three lenses to unpack the practice of designing for services: One emphasizes the design of artifacts, known as touchpoints, as the material point of contact with a service. Another, as designing for exchanges through which actors co-create value together. And a third emphasizes the messy socio-material configurations shaping services.

On the other hand, Critical Design is here employed as an umbrella term for practices that use design as a vehicle to reflect on futures as personal and lived experience. Critical Design is used to explore possible future worlds through the use of artifacts, as a tool to generate debate around issues within contemporary design, culture, science, technology and society; to better understand the present and what possible futures might be desirable. The role of artifacts in Critical Design is to make alternative future world visible and tangible (Auger Citation2013; Dunne and Raby Citation2013; Malpass Citation2016, Citation2017; Pollastri Citation2017). Worlds are built through a variety of different artifacts, which become fictional objects that exist in the unreality of fictional worlds and are “entry points” into these alternative worlds. Making these fictional artifacts is an act of world-building (Coulton et al. Citation2017).

3.1. Critical service design

I refer to Critical Service Design (CSD) as the design of fictional services, whereby fictional services are a means of exploring alternative futures. Making these fictional services is an act of world-building. When we experience fictional services we intuitively understand how the service lives and interacts with the socio-material configurations of a complex fictional world (Kimbell and Blomberg (Citation2017). CSD is concerned with the design of fictional services that are not intended to solve present-day problems, not at all interested in predicting the future, but on exploring alternative –and potentially preferable– future worlds. In the context of local governance, CSD engages in envisioning novel public policies and services that might support the attainment of preferable future worlds. This critical position places an emphasis on preferable futures, defined by that which enables the conditions of ecological sustainability (Fry Citation2009), human-centred as opposed to technotopian futures (Gidley Citation2017) and desired-based as opposed to the conventional problem-based approaches that dominate design (Leitão Citation2020). CSD in the context of Public Sector Organizations is “oriented toward improving the mechanisms of governance and increasing participation in processes of governance” (DiSalvo Citation2021, 2), making “explicit the assumptions and preferences underlaying designed visions of the future” (Mazé Citation2019, np).

3.2. World-building preferable futures through Critical Service Design

World-building preferable futures through Critical Service Design follows a three-stage iterative process that comprises: reframing local government objectives, world-building, and back-casting and reporting:

3.2.1. Reframing and local government objectives

The first step is to identify strategic priorities proposed by local government. The criteria have been to select priorities that are in early stages of development and assigned to public officers who are keen on involving residents and organizations in co-defining preferable outcomes. The second step consists of building an Evidence Safari (Policy Lab Citation2016): a visual database of relevant data evidence, which is compiled as a collection of visual cards that contain nuggets of evidence such as extracts from scientific studies, policies, services, and everyday life practices; extracted from diverse sources such as policy and grey literature, newspapers, pop culture, annotations from direct observation and briefings from experts. A framework of analysis is suggested, exploring political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental factors across geographies—South, North, West and East–, scale –local, national, and international– and time –past, present and future through trends. The Evidence Safari is both an accessible way of communicating relevant research insights and a source of inspiration, looking at concrete examples of how the world was, is or could be. Finally, a brainstorming technique that supports divergent thinking consisting of asking What if Questions is employed, aiming at reframing policy problems and explore hard-to-imagine possibilities (Dorst Citation2011). It is through formulating What if Questions that participants start expressing their desires and exploring what might be preferable.

3.2.2. World-building preferable futures

Creative facilitation techniques (Tassoul Citation2009) are employed by designers to engage local residents and public servants in rapid and iterative prototyping where making is a form of knowing and creative enquiry (Koskinen et al. Citation2013). Participants engage in rapid prototyping of fictional services, which are co-created iteratively (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008). Creative facilitation and co-design methods guide participants through the process of world-building. When participants interact with the touchpoints of a fictional service, they are experiencing the fictional service as a whole, entering the complex alternative world in which that service lives. In assembly, participants then present their fictional services and discuss whether they belong to preferable world, asking everyone: “how does this service contribute to make a better future?,” “for whom is it a better future?”. In doing so, participants explore competing worldviews, for what is preferable is bound up with each participant ideological narratives and worldviews (Inayatullah Citation2013).

3.2.3. Back-casting and reporting

In assembly, participants advocate for their preferable futures and collectively explore “how this desirable future can be attained” through engaging in a backcasting exercise (Robinson Citation1990, 822). All participants, including residents, organizations and local government, suggest present-day choices that would lead to reach that point, each of them answering “what can I do know to attain this future?” and “what support do I need from others?”. Finally, a report with the key insights is produced to be considered by policy makers.

4. Climate studio

In this section I outline a case study of Critical Service Design, world-building preferable food futures with local residents and organizations: Climate Studio (Salinas, Lang, and Swift Citation2022)

Climate Studio (CS) is a collaboration between University of the Arts London and local community organizations across London to support place-based climate action. CS was set up across three clusters in the North, East and South of London from March to July 2022. The South Cluster was led by Service Futures Lab at London College of Communication in collaboration with Southwark Council and four local organizationsFootnote1. The cluster’s design team was constituted by two academic leads, three design researchers and 30 postgraduate service design students. The 30 postgraduate design students worked on the project as part of their Design Futures module. Students formed 5 working teams and collectively dedicated an estimate of over 2000 h to the project. Student employed an online visual collaboration platform and weekly catchups to enable across-team collaboration and worked in close collaboration with the design research team and local organizations. Over a period of 14 weeks the cluster delivered 10 2-h design-led workshops in four local venues, engaging over 100 young residents to envision preferable food systems through Critical Service Design, and informed the borough’s Climate Emergency Action Plan ( Southwark Council, Citation2022).

The London Borough of Southwark Council is located South London, England. In 2018, Southwark Council (SC) declared a climate emergency and set up the objective of making the borough carbon neutral by 2030 (Climate Emergency Citation2022). Aware of the high complexity of the challenge, SC is keen on exploring novel and collaborative approaches to local policy making. As CS was being set up, the council’s Climate Emergency Department was supporting the development of a Sustainable Food Action Plan contemplating policy objectives such as increasing local good growing, improving education and learning about sustainable food, increasing sustainable consumption patterns or improving access to healthy, affordable and culturally appropriate food in the borough. The project’s direction was set up to inform the development of the Sustainable Food Action Plan.

As a starting point, the design team familiarized themselves with the council’s Climate Action Plan and previous Food Action Plans. The team then progressed to develop an Evidence Safari that related to each policy problem, enriched by the multiculturality of the group while focused on South London (). Thought provoking questions sought to reframe policy problems, and these were collected in a What if Questions bank that grew iteratively as the project progressed ().

Figure 2. Evidence Safari card from a national newspaper. It argues for the importance of urban green spaces as a resource for locally sourced produce with wider health benefits.

Table 1. A sample from the What if Questions bank.

This preliminary research prepares designers to engage participants in co-creation workshops. Workshops were tailored to the participant group and thematic to the policy objective to be explored, e.g. a workshop with young artists engaged in co-creating a space for community activism (Climate Home Citation2022) focused on exploring opportunities to improving education and learning about sustainable food, while providing a training opportunity on co-design. showcases a participant at a co-creation workshop, at which illimited broadband was banned, community coming together to share resources was amplified, and a new (critical) public service created: “Gardening Duty.” Inspired by the UK’s Jury service, “Gardening Duty” made collective caring for green spaces mandatory while affording accreditation to duty gardeners. Later, in assembly, all participants explored the alternative world brought about by participants’ fictional services. A selection of proposals was iterated in the design studio and at later workshops () as a means of collaboratively exploring preferable futures. A selection of fictional services that tackled SC’s policy objectives was presented at a final event to local residents, organizations and government officers, with facilitation from design students. Each fictional service was supported by a selection from the Evidence Safari and What If Questions. Attendees were asked to engage in a backcasting activity by answering “what can I do know to attain this future?” and “what support do I need from others?” (), proposing several achievable present-day actions to tackle food related challenges. A final analysis of the world built and discussions held was produced by the design team for SC’s consideration into the Climate Emergency Action Plan (Southwark Council, Citation2022).

5. New directions

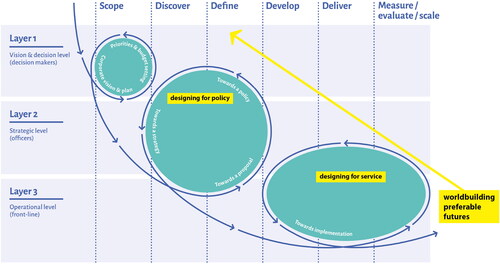

By mirroring a policy cycle in a parallel future framework, Critical Service Design has opened an opportunity to do local policy differently. World-building preferable futures through Critical Service Design has brought the local forward through situated civic engagement with local actors. Through making, CSD has afforded inclusive civic engagement, drawing into local resources and the distributed expertise of local actors to inform the formulation of complex policy issues. Insights gained from the experience of engaging with fictional services has brought a future-making stance to policy making, where policy problems and solutions are formed together in an interactive dialogue, challenging the linearity of traditional policy making processes ().

Figure 5. Local policy making cycle that situates “world-building preferable futures through Critical Service Design” as a parallel activity with the ability to feedback to policy making. Based on Thorpe et al. (Citation2017).

Critical Service Design is appealing to local government as it brings additional capacity and capability from the design team. It also provides local government with a safe space for experimentation, with no necessary interference to local government business-as-usual processes or becoming overly reliant on the collaboration with an external party, in this case the design school. Operating in a parallel future framework gives local government a flexible scope to incorporate insights into the local policy making cycle. CSD is also appealing to design education, as participants engaging in world-building have developed future acumen and literacy, increasing their ability to problematize future scenarios and experiment new ways to deal with them (Malpass and Salinas Citation2020, 47). Moreover, design postgraduate students have been initiated in design for local governance (Salinas Citation2022b) and many continue their career into design in or for Public Sector Organizations.

There is opportunity for further research into the co-production of public services and policies. While the proposed design-led methodology successfully incorporates inclusive civic engagement earlier in the policy cycle, there is an opportunity to enable the conditions of co-production of public services and policies (Salinas et al. Citation2018). World-building preferable futures seeks to give participants ownerships of their future. Further iterations may seek a greater involvement from local organizations and government throughout and especially in the backcasting activity. Backcasting is a provoking exercise, for the attainment of what is agreed to be desirable often challenges local government siloed structures and articulations of value. The activity was originally conceived as a point in which local actors, including representatives from across local government, would be given the opportunity to participate actively in further prototyping of public policies and services.

6. Conclusion

Critical Service Design has been defined as the design of fictional services, whereby the making of fictional services is a means of world-building and exploring alternative, potentially preferable futures.

I have started by reflecting on three challenges faced by local government, related to the limitations of traditional problem-solving approaches to deal with highly complex challenges, exacerbated by the difficulty to adopt innovative design-led approached due to local government’s diminished ability to experiment, innovate and effectuate, and the underdevelopment of training programmes on design for policy in higher education. In response to these challenges, I have proposed a novel approach that features a future-making stance to local policy making, moving away from linear approaches that lead to artificially tame highly complex challenges. I have proposed a critically engaged approach to design for public policy and services through the practice of Critical Service Design. CSD places an emphasis on preferable futures, those which are sustainable, human-centred and desired-based. The methodology has been exemplified with an example from my practice: Climate Studio (Salinas, Lang, and Swift Citation2022). Novel directions, limitations and further research have been discussed, acknowledging the difficulty to secure a greater engagement from local government actors and the benefits of collaboration between local government and design education.

World-building preferable futures through Critical Service Design is a novel approach to design for local policy that affords anticipatory and collaborative innovation, better equipping local government to tackle highly complex challenges. Core to the approach are design-led methods to civic engagement to engage local residents and organizations in local governance. It is through the making of fictional services that participants engage in building preferable worlds, expressing their desires and drawing on their situated knowledge. For local government, this presents an opportunity to learn from the realization of potentially preferable futures, enacting policies through playful experimentation, gaining valuable insights on expected and unexpected consequences of fictional services, identifying present-day actions that might lead to preferable futures.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to my colleagues Marion Lagedamont, Tom Taylor and Digby Usher for their key role in delivering Design Futures and Climate Studio, as well as to all participants of (Global) Design Futures and Climate Studio. I would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that helped improve the quality of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 PNK Garden, Bizzie Bodies at Dockland Settlement Centre, Global Generation at the Paper Garden and Sounds Like Chaos at The Albany.

References

- Auger, J. 2013. “Speculative Design: Crafting the Speculation.” Digital Creativity 24 (1): 11–35. doi:10.1080/14626268.2013.767276

- Bartlett, J. 2009. Getting More for Less. Efficiency in the Public Sector. London: DEMOS.

- Bason, C. 2017. Leading Public Design: Discovering Human-Centred Governance. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Buchanan, R. 2001. “Design Research and the New Learning.” Design Issues 17 (4): 3–23. doi:10.1162/07479360152681056

- Climate Emergency. 2022. “Southwark Council.” https://www.southwark.gov.uk/environment/climate-emergency

- Climate Home. 2022. The Albany. https://www.thealbany.org.uk/get-involved/climate-home/

- Coulton, P., J. Lindley, M. Sturdee, and M. Stead. 2017. “Design Fiction as World Building.” In Proceedings of Research Through Design Conference 2017. Edinburgh

- DiSalvo, C. 2012, Adversarial design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Dorst, K. 2011. “The Core of ‘Design Thinking’ and Its Application.” Design Studies 32 (6): 521–532. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006

- Dunne, A, and F. Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Dunne, A, and F. Raby. 2001. “Design Noir.” https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/design-noir-9781350070653/

- Dunne, A, and F. Raby. 2009. “A/B Manifesto.” http://dunneandraby.co.uk/content/projects/476/0

- Evans, M. 2010. “Design Futures: An Investigation into the Role of Futures Thinking in Design.” PhD thesis, Lancaster University.

- Frayling, C. 1993. “Research in Art and Design.” Royal College of Art Research Papers 1 (1). 1-9. https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/384/3/frayling_research_in_art_and_design_1993.pdf

- Fry, T. 2009. Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics, and New Practice. English ed. Oxford, UK: Berg.

- Gidley, J. M. 2017. The Future: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Inayatullah, S. 2013. “Futures Studies: Theories and Methods.” In There’s a Future: Visions for a Better World, 30. Madrid: BBVA.

- Junginger, S. 2014. “Towards Policymaking as Designing: Policymaking Beyond Problem- Solving and Decision-Making.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing Ltd.

- Kimbell, L, and J. Bailey. 2017. “Prototyping and the New Spirit of Policy-Making.” CoDesign 13 (3): 214–226. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1355003

- Kimbell, L, and J. Blomberg. 2017. “The Object of Service Design.” In Designing for Service Key Issues and New Directions, 14, D. Sangiorgi and A. Prendiville. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. doi:10.5040/9781474250160.ch-006

- Kimbell, L., L. Richardson, R. Mazé, and C. Durose. 2022. “Design for Public Policy: Embracing Uncertainty and Hybridity in Mapping Future Research.” Design Research Society 2022. Bilbao, Spain: DRS doi:10.21606/drs.2022.303

- Koskinen, I., J. Zimmerman, T. Binder, J. Redstrom, and S. Wensveen. 2013. “Design Research through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and Showroom.” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 56 (3): 262–263. doi:10.1109/TPC.2013.2274109

- Leitão, R. M. 2020. “Pluriversal Design and Desire-Based Design: Desire as the Impulse for Human Flourishing.” In Pivot 2020: Designing a World of Many Centers. DRS Pluriversal Design SIG Conference 2020. London, UK: DRS Pluriversal Design SIG. doi:10.21606/pluriversal.2020.011.

- Malpass, M. 2016. “Critical Design Practice: Theoretical Perspectives and Methods of Engagement.” The Design Journal 19 (3): 473–489. doi:10.1080/14606925.2016.1161943

- Malpass, M. 2017. Critical Design in Context: History, Theory, and Practices. London: Bloomsbury. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/critical-design-in-context-9781472575180/

- Malpass, M, and L. Salinas. 2020. AHRC Design Fellows Challenges of the Future: Public Services. Swindon, UK: AHRC

- Mazé, R. 2019. “Politics of Designing Visions of the Future.” Journal of Futures Studies 23 (3): 23–38. doi:10.6531/JFS.201903_23(3).0003

- Mortati, M., S. Schmidt, and L. Mullagh. 2022. “Design for Policy and Governance: New Technologies, New Methodologies.” Design Research Society 2022. Bilbao, Spain: DRS. doi:10.21606/drs.2022.1066

- Policy Lab. 2016. “Exploring the Evidence.” Kirby. https://openpolicy.blog.gov.uk/2016/03/07/exploring-the-evidence/

- Pollastri, S. 2017. “Visual Conversations on Urban Futures. Understanding Participatory Processes and Artefacts.” PhD thesis, Lancaster University.

- Robinson, J. B. 1990. “Futures Under Glass: A Recipe for People Who Hate to Predict.” Futures 22 (8): 820–842. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(90)90018-D

- Salinas, L. 2018. “The Future of Government 2030+.” In Design Research for Change, edited by P. A. Rodgers, 115. Lancaster, UK: Lancaster University:

- Salinas, L. 2021. “Sustainable Futures for Southwark.” https://www.arts.ac.uk/about-ual/press-office/stories/sustainable-futures-for-southwark-helping-londons-borough-to-achieve-carbon-neutrality-by-2030

- Salinas, L. 2022a. “What Design Research Does….” In What Design Research Does…, edited by P. A. Rodgers and L. Wareing. Glasgow, UK: University of Strathclyde

- Salinas, L. 2022b. “Practice Research in Social Design & Design for Sustainability.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mL0X7Aw_rM

- Salinas, L., A. Lang, and C. Swift. 2022. Climate Studio. London: University of the Arts London.

- Salinas, L., A. Thorpe, A. Prendiville, and S. Rhodes. 2018. “Civic Engagement as Participation in Designing for Services.” ServDes2018. Milan, Italy: Politecnico di Milano.

- Sanders, E. B.-N., and P. J. Stappers. 2008. “Co-creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/15710880701875068

- Sangiorgi, D., and A. Prendiville, eds. 2017. Designing for Service: Key Issues and New Directions. London: Bloomsbury.

- Council, Southwark. 2022. Exhibition Showcases Young People’s Vision for Food of the Future. London: Southwark Council. https://www.southwark.gov.uk/news/2022/jun/exhibition-showcases-young-people-s-vision-for-food-of-the-future

- Tassoul, M. 2009. Creative Facilitation. Delft: VSSD.

- Thorpe, A., A. Prendiville, S. Rhodes, and L. Salinas. 2016. “Public Collaboration Lab.” In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference: Short Papers, Interactive Exhibitions, Workshops-Volume 2. Aarhus, Denmark: PDR. doi:10.1145/2948076.2948121

- Thorpe, A., A. Prendiville, L. Salinas, and S. Rhodes. 2017. “Anatomy of Local Government/Design Education Collaboration.” The Design Journal 20 (sup1): S4734–S4737. doi:10.1080/14606925.2017.1352975

- Thorpe, A., and S. Rhodes. 2018. “The Public Collaboration Lab—Infrastructuring Redundancy With Communities-in-Place.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 4 (1): 60–74. doi:10.1016/j.sheji.2018.02.008

- Whicher, A. 2020. AHRC Design Fellows Challenges of the Future: Public Policy. Swansea, UK: AHRC