Abstract

The Connection to Care (C2C) project, a transdisciplinary work-in-progress, employs community-engaged participatory research and design methods at the nexus of policy adaptation and product innovations. C2C aims to advance practices that identify and leverage the critical junctures at which people with substance use disorder (SUD) seek lifesaving services and treatment, utilizing stakeholder input in all stages of design and development. Beginning in the Fall of 2018, members of our research team engaged with those at the forefront of the addiction crisis, including first responders, harm reduction and peer specialists, treatment providers, and individuals in recovery and in active substance use in a community greatly impacted by SUD. Through this engagement, the concept for programs and products representing a connection to care emerged, including the design of a backpack to meet the needs of individuals with SUD and those experiencing homelessness. From 2020 to 2022, more than 1,200 backpacks with lifesaving and self-care supplies have been distributed in local communities, as one component of the overall C2C initiative. The backpack is a recognized symbol of the program and has served as an impetus for further program and policy explorations, including as a lens to better understand the role of ongoing stigma. Though addiction science has evolved significantly in the wake of the opioid epidemic, artifacts of policies and practices that criminalize and stigmatize SUD remain as key challenges. This paper explains the steps that C2C has taken to address these challenges, and to empower a community that cares.

1. Introduction

There has been a radical change in design from experts designing for people, to people designing for themselves (Norman and Spencer Citation2019). An innovation designer has the responsibility to make a positive impact on the world not only through products (tangible and intangible) but also the design of policy. The charge is also to bring social awareness and action to issues ranging from local health challenges, poverty, education, gender equity and other complex domains. Design innovation has become a strategic tool to tackle major societal challenges, in order to improve the quality of life (Design Council Citation2017).

Human-Centered Design (HCD) and Community-based Participatory Research and Design (CBPR&D), widely recognized design approaches, are people-centered approaches to address real-world problems through integrated and innovative product, policy, and program designs (Chen et al. Citation2020). CBPR&D is utilized widely to develop social innovations, and is a research approach that integrates information sharing and social action/impact to improve health and reduce health inequities (Wallerstein and Duran Citation2006). IDEO, one of the most prestigious global design firm companies in the world, exemplifies this evolution, operating from the premise that community design is grounded in equity, inclusion, and deep collaboration. IDEO’s HCD process for problem-solving consists of three distinct phases: the inspiration phase, the ideation phase, and the implementation phase (Brown and Wyatt Citation2010; IDEO Citation2015). The principles of human-centered design are effective and productive tools intertwined with CBPR partnerships to reflect the values of various stakeholders and the impact that policy applications have on each stakeholder in the local environment.

Substance use disorder is an example of a social challenge that impacts communities worldwide and is subject to locally applied policy adaptations. SUD remains a complex and intractable problem, cutting across many domains of health, criminal justice, housing, workforce and economic policies. It has many, often multiplying negative impacts on society, communities, interpersonal relationships, and individuals struggling with SUD. Likewise, finding solutions to SUD and investing in a recovery ecosystem creates positive impacts across these dimensions, generating positive return on investment of public resources (Pettersen et al. Citation2019; Ashford et al. Citation2020). However, policy and program solutions that have significant positive impact in some contexts and communities do not always neatly translate to new contexts and communities (Stone Citation2012).

In this article, two overarching themes are explored: (1) the intersection of tangible product design and CBPR&D as a mechanism for policy translation; and (2) the challenges that arise in the application and translation of social policy innovations. The context and case study for this examination is the implementation of the Connection to Care (C2C) pilot project, a multifaceted innovation to address the dramatic rise in overdoses and other health-related consequences of SUD in the Roanoke Valley of Virginia (USA).

2. Context of the case study

Over the past two decades the proliferation of opioids, initially prescription opioids and quickly evolving to illicit heroin and synthetic versions, has spawned an overdose and addiction crisis (Feldscher Citation2022). More recently, communities have increased focus on the polysubstance use and overdose crisis, where deadly synthetic opioids are being found in many substances, depressants and stimulants alike, further complicating approaches to harm reduction, treatment and recovery (Peppin, Raffa, and Schatman Citation2020). In February of 2022, the American Medical Association (AMA) published an issue brief stating that the United States’ substance use and “drug overdose epidemic continues to change and become worse,” calling for policymakers to take action to “increase access to evidence-based care for substance use disorders (SUD), pain and harm reduction measures” (AMA Citation2022, 1). Without coordinated, locally responsive innovations in policy and program design, it is likely that the current trend of more than 100,000 overdose deaths per year in the United States (CDC Citation2021) will continue or even worsen.

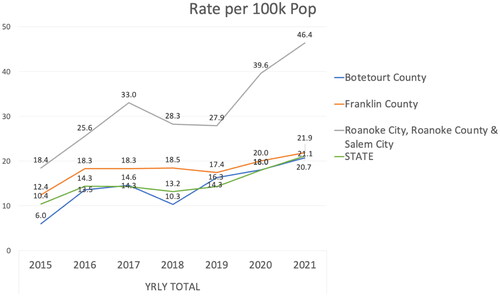

This case study examines the impact and promise of design innovations in the Roanoke Valley region of Southwest Virginia. The region includes five independent local governmentsFootnote1 with a total population of more than 315,000 in both urban and rural areas spanning nearly 1,900 square miles. Representative of the national addiction crisis, the Roanoke Valley region has experienced above national average rates of drug overdose and incidence of negative health impacts of substance use. In 2020 and 2021, the region experienced a dramatic increase in all drug related overdoses compared with the previous years and the Virginia state average ().

In 2020 alone, an average of four Virginia residents died from an opioid overdose daily, resulting in a 17% increase in overdose deaths since 2019 (VDH Citation2021). Studies have shown that the risk of fatal overdose is significantly greater among low-income individuals (Altekruse et al. Citation2020). For example, people who are unemployed are at greater risk of dying of an opioid overdose compared to the employed (Han et al. Citation2017). summarizes key socio-economic factors related to SUDFootnote2 for the Roanoke Valley metropolitan statistical area (MSA) and compared to Virginia overall.

Table 1. Opioid and health related indicators for the Roanoke Valley MSA and Virginia.

During this time of national and local crisis, the Connection to Care (C2C) project concept materialized through engagement with a community-based initiative, the Roanoke Valley Collective Response to the Opioid and Addiction Crisis (RVCR). The RVCR is organized into five workgroups targeting specific socio-ecological aspects of the addiction crisis, from crisis response to recovery supports (Jalali et al. 2020). The Crisis Response and Connection to Care (CRCC) workgroup is the RVCR workgroup charged with developing strategies to curtail overdose and develop pathways to treatment and recovery for those with addiction (RVCR Blueprint Citation2020).

In the Fall of 2018, a group of Virginia Tech (VT) researchers began working with the RVCR to support ongoing needs assessment and strategy development.Footnote3 Through this engagement from 2018 to 2019, the framework for the C2C project emerged.Footnote4 The CRCC workgroup includes significant cross-sector representation including harm reduction programs (Des Jarlais 2017), emergency medical services (EMS), law enforcement, public health, and health care providers, including hospital emergency department providers. The role of VT researchers was to capture the input of these community members on possible strategic responses, to support information needs through data collection on overdose and other SUD incidence rates, and to research emerging and evidenced-based practices.

Through months of engagement and information exchange, the concept of a tangible item or items that could be introduced at key junctures to those at highest risk of overdose and with the greatest need to be connected to services was developed. In particular, EMS and ED stakeholders reflected that they were constantly responding to individuals experiencing drug overdose and other health crises, and once the immediate need was addressed through overdose reversalFootnote5 or meeting other urgent medical needs, such as infection and cardiovascular distress, the patient would exit care often against the advice of the health care provider. These providers expressed the desire to have something to give to these individuals that they would hold onto that would provide a link to resources when the individual was ready to receive harm reduction or treatment services. From this engagement, the idea of the C2C backpack and linking mechanisms emerged.

The VT researchers representing the disciplines of public health and public policy and governance approached colleagues from the industrial design (ID) program with the emerging concept. Collaborating with ID faculty and students on this community inspired design, it was decided by the interdisciplinary team that closer engagement and input from the target population was needed.Footnote6 As a key community partner, a harm reduction coalition facilitated engagement with peer recovery specialists and those in active substance use who advised on the backpack design and the items to be included. This consultation resulted in a design with safety for the individual and their belongings as a priority, as well as providing a built-in compartment for naloxone and instructions for use.

In early Spring of 2019, the backpack prototype was presented by the ID students to a full meeting of the RVCR with ∼70–80 community members in attendance. This thoughtful and tangible representation of a connection to care for some of the most vulnerable and stigmatized in the communities resulted in palpable excitement among the community members, creating momentum to advance from inspiration to ideation, planning and implementation.

3. CBPR design process and methods

As discussed above, CBPR&D has become an impactful core of design and creativity, especially when it is related to health and social impacts (Martinez et al. Citation2020). In this study, the research team leveraged the local communities’ creativity and knowledge to tackle opioid epidemic challenges. Constituencies, such as public health experts, people with SUD, individuals in recovery, healthcare providers, law enforcement, and family members are the stakeholders that are best aware of the social influences and affordances that impede and support change. In collaboration with these community members, the research team applied mixed methods data collection (a range of qualitative techniques), which is commonly utilized in CBPR&D. They also used observation, in-depth interviews, and think-aloud in an agile/repetitive process that provided a range of opportunities for effective interaction and exploration with groups of stakeholders (Israel et al. Citation2012). Data collected during the design process was continuously used in needs assessment and design evaluation, which helped to determine how the C2C backpack design could be further developed to better meet community needs.

In designing the overall innovation, the research team through the CBPR&D process explored various linking touchpoints for connecting individuals most at risk of overdose and other related substance use harms to harm reduction and treatment services. As a central tool in the innovation, the VT team designed and prototyped a custom backpack with a built-in sleeping bag and secure pockets as a central connection mechanism and symbol of compassion for a most often stigmatized population. The design team consisted of six industrial design students: Blythe Row, Anna DiNardo, Connor Howerton, Cristina Dunning, and Wesley Rogers. In this process, they conducted multiple sessions with various stakeholders, such as harm reduction programs, first responders, health care providers, individuals in recovery and individuals in active substance use during the CBPR&D process outlined in . They also used thematic analysis to analyze the qualitative data collected, which provided action items, used in concept development.

Addressing the issue of stigmatization of SUD is one of the main findings that the VT team came across during ongoing engagement with the CRCC and C2C stakeholders. Another finding was that harm reduction and treatment service programs providing services to people with SUDs seek to destigmatize the general public’s view of people who use drugs. Also, these stakeholders consistently reflect that sustained funding is a challenge because it is subject to donations, time-limited grants, and fluctuating state policy and economic factors. Many friends and family of people with SUD who may take care of their loved ones with SUD mentioned that they are aware of the risks of physical and mental well-being but still are willing to invest in taking action to reduce the greater opioid epidemic. Also, while some recognize opioid overdose symptoms and are trained in administering naloxone, others have not been made aware or trained to respond when needed. In addition, they mentioned that drug use was the main source of instability in their family and among friends ().

Harm reduction advocates engaged with the C2C project cited that most overdoses are reversed by people who also use drugs, and this is supported in the literature (Wheeler et al. Citation2015). Creating a policy and program solution that facilitates use of naloxone for all community members can reduce the death rate of people with SUD. This vulnerable population group also experiences high rates of housing insecurity, and as a result, there is more probability for theft in their day-to-day living environment. Considering these two factors, the design solutions needed to address the immediate needs of someone without reliable housing and related supports who may also need to administer an opioid reversal drug.

The design team leveraged these insights to support the specific needs of these populations and the linking touchpoints. The findings were also categorized into three main criteria: level of housing insecurity, potential for overdose prevention and need for human service connections (). There is also significant evidence of the correlating relationship between past and ongoing trauma, mental health disorders, substance use and housing insecurity (McNaughton Citation2008; Khoury et al. Citation2010; Dawson-Rose et al. Citation2020), However, policies and programs designed to address these issues too often focus on each one separately, limiting more holistic solutions.

For persons in active substance use (PASU) and those early in treatment and recovery who are in varied living conditions and degrees of stability, there is a need to meet and support individuals in the current status of their life and connect them with their community and resources to initiate and scale stability. The C2C project seeks to make these connections to improve individuals’ stability and sense of connectedness through cross sector and interagency partnerships that have a shared understanding of enabling and limiting policy. Collaborative partnerships among human service agencies are highly reliant on communication and feedback loops to ensure coordination and to maximize application of scarce resources (Park, Wilding, and Chung Citation2014).

As a tool and symbol of this connectedness, the backpack, and referral information contained within it, serves as a first step toward improved stability. Since many PASU carry their personal belongings and necessary supplies, the backpack design ideally serves as a portable living resource, and accommodates security concerns of people with SUD through compartmentalized storage where supplies and belongings can be kept securely. The volumetric footprint of these products needs to be carefully considered in the backpack design.

3.1. Backpack design and specifics (TRI-PACK)

Integration of HCD and CBPR&D frameworks informed the design of the C2C backpack named TRI-PACK. The phase one design of the TRI-PACK is intended to hold 48 h worth of clothing, food, water, hygiene supplies, referral cards to local harm reduction and treatment services, and a complete opioid overdose reversal kit.

The tri-fold backpack is designed to open up like a suitcase so that the user doesn’t have to dump everything out to get what they need. The central compartment holds a sleeping bag and inflatable pillow, which can be spread out across the central panel so that the rest of the bag can wrap around the individual, decreasing the opportunity for theft for those who are homeless and housing insecure ().

The original overdose kit contained three doses of intramuscular injection naloxone, and three sterile syringes, individually sealed in tear open pouches to protect them from the elements. The kit included visual instructions to make it clear how to use it for people with SUD, their caretakers or any other citizen, even non-English speakers who might come across a situation requiring their immediate assistance. The kit was designed to be affordable and easy to assemble by local harm reduction groups. It fits neatly in its own easily accessible pocket within the C2C backpack ().

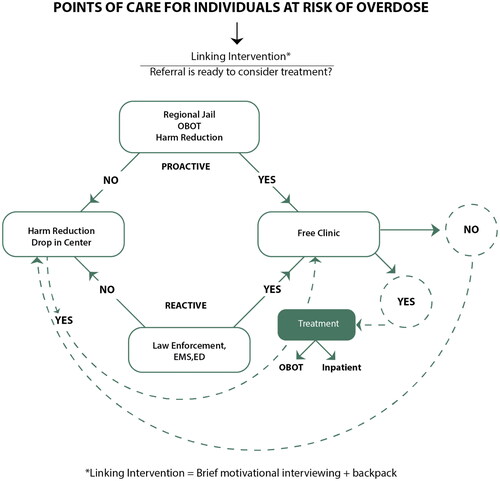

The C2C backpack is strategically designed to be distributed through various support agencies and partners in the Roanoke Valley region. As part of the linking innovation, the backpack is provided proactively and reactively. As a proactive innovation, the backpack is provided to those at risk of overdose, for example those leaving incarceration with a known SUD, or those leaving treatment in early stages of recovery and at risk of relapse. As a reactive linking innovation, the backpack is provided to those most at risk due to active use, in the process of accessing harm reduction services or in response to overdose or other SUD related health crises ().

This first full prototype was evaluated by stakeholders including healthcare providers, EMS, law enforcement and harm reduction advocates, such as peer recovery specialists. These stakeholders did not raise any specific concerns about the design until the prototype and the user experience was completed. In the sections below, some of the pushback and necessary modifications that were made regarding the design and distribution of the backpacks are explored.

3.2. C2C Project implementation

While the tangible symbol and useful function of the backpack inspired ensuing logistical planning, the CRCC workgroup, including the [University Name] public health and policy team, recognized that the backpack’s intended use as a connecting instrument would only have impact if the care component met the individual’s needs and their readiness to seek services. Therefore, community partnerships were designed to provide a continuum of reactive and proactive services. In October of 2019 the Virginia Tech team became aware of a grant opportunity managed by the University of Baltimore’s Center for Drug Policy and Prevention, Combating Overdose Through Community-level Innovation (COCLI). In partnership with community partners, Virginia Tech applied and received the grant to implement the C2C pilot project components.Footnote7

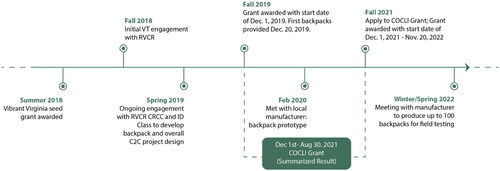

The COCLI grant funded: (1) the purchase of backpacks and materials provided in the backpacks; (2) peer recovery specialist services in two partner agencies; (3) Virginia Tech project team support for implementation, ongoing engagement with community partners, policy navigation and dissemination, data collection and evaluation, and ongoing development of the backpack prototype design. Within the first six months of the grant, the research team developed a brief assessment that was completed upon distribution of the full backpack, and a longer intake assessment completed by harm reduction service providers and clinical service providers when PASU agreed to case management services. These assessments have been extremely valuable to better understand the dynamics and needs of the target population. The grant period was originally for one year, however with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the grant was extended to August 30, 2021. In the Fall of 2021, the research team applied for another round of funding and has been awarded another grant for the December 1, 2021 to November 30, 2022 timeframe ().

With the new grant award, the C2C team continues distribution of the off-the-shelf backpacks, ongoing and evolving partnership development for reactive and proactive referrals, facilitation to expand housing resources for PASU needing more stable living conditions and for those in early stages of treatment and recovery. Funding will also allow for the manufacture and field testing of 50–100 of the innovatively-designed TRI-PACKS with both PASU and lay consumers to further assess the usability and marketability of the backpack. Ongoing engagement with community stakeholders has been central to early project implementation and ongoing assessment of the pilot program effectiveness. Through this engagement, innovations have been adapted when needed to achieve the goals of reducing harm and connecting individuals to treatment services.

3.3. Lessons learned and adaptations to the program design

As noted, the full-size backpack was designed for those at high risk of overdose and who are homeless or housing insecure and was initially stocked with injectable naloxone, hygiene kits, clothing and sleeping supplies, mobile power banks, water bottles, and referral information to services. At the onset, community distribution partners were to include law enforcement, EMS, harm reduction and treatment providers and EDs, who would distribute injectable naloxone as provided by a community harm reduction agency with a physician’s standing order for distribution.

Upon implementation, this plan faced several barriers. The first complication was that, though first responders were among those who suggested a backpack as a connection to services, when more broadly introduced to front line officers and EMS providers, there was a perception that provision of the backpacks to PASU constituted a reward for harmful behavior, and often illegal actions (Dineen 2016; Smiley-McDonald et al. 2022). A second challenge was the interpretation that the provision of syringes with the overdose kit constituted supplying drug paraphernalia, though the syringes were of a gauge intended for intramuscular use, rather than intravenous injection. While syringe exchange in Virginia was legally authorized in July 2017 by state certified comprehensive harm reduction programs, the law required approval by local law enforcement. Law enforcement agencies throughout the state have been slow to approve, with only five such programs statewide in March of 2022. The harm reduction provider supporting backpack production and distribution was not approved for syringe exchange at the time. A final barrier realized during the early implementation phase was concern and confusion among a number of community partners regarding the training and recordkeeping requirements for the provision of naloxone. While there were policy efforts at the state level to broaden access, these changes were not effectively communicated to local agencies.

These barriers manifested in February and March of 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic became a dueling and compounding crisis to the SUD crisis. Nonetheless, the stakeholder team continued to meet at least monthly by moving to virtual meetings. The backpacks and referral connections were shifted to other providers that frequently interact with individuals at risk of overdose including jails, homeless shelters, residential treatment providers serving low-income individuals and drop-in centers. The backpack and intake assessments have further enabled adaptation as needed.

To address the dual concern of use of the intramuscular form of naloxone and the requirements for training and record keeping, the stakeholder group enlisted the guidance of a supervisory pharmacist working for a large regional health system, a representative of the regional health department, and the regional behavioral health agency. Collectively, this group reviewed state law pertaining to naloxone training and distribution, specifically seeking to leverage the state’s program known as REVIVE!, the opioid overdose and naloxone education program for Virginia, operated by the state behavioral health agency (VDBHDS Citation2022). As COVID-19 began to limit in-person training opportunities, the agency worked quickly to advance virtual training opportunities.

On March 19, 2020, the state health commissioner issued a revised statewide standing order, which enabled an expanded group of agencies and professionals to provide REVIVE! training and distributing Narcan, the nasal spray formulation of naloxone. Leveraging these policy changes, the C2C project shifted to providing the backpacks stocked with supplies to community partners and facilitated the applications and processes necessary for the community partners to provide REVIVE! training and to access no cost Narcan provided by the state health department.

Additional COVID-19 challenges included delays in advancing manufacture of the original backpack design, loss of engagement with first responders, and spikes in overdose that have been correlated with the pandemic nationally (Baumgartner and Radley Citation2021). The project team collaborated with a local nonprofit manufacturer who employs individuals in recovery from SUD and those with mental, intellectual and physical disabilities to determine the scalability of the design. Since the first version of the C2C backpack was designed by hand without considering the design limitations and opportunities related to manufacturing processes, some minor changes in patterns, materials and the order of sewings were applied by the local manufacturer. It is expected that these changes would be specific to each manufacturer, their facilities and production equipment and the number of bags requested. As the researchers were preparing to produce a sample of the backpacks for field testing, the manufacturer had to close down operations due to COVID-19.

Some community partners requested a smaller backpack containing a few basic items, such as Narcan, face masks, hand sanitizer and referral information, for people who were housing secure but in need of resources, which led to creating the design of the “lite” backpack. The lite backpacks were also easier to store for certain partners, including EDs with limited storage capacity, and by harm reduction programs whose consumers often return for case management and supplies. The lite backpacks were also very instrumental in providing referral information, face masks and Narcan during the C2C facilitated walkup REVIVE! events. The lite backpacks are simple, low-cost drawstring packs, with referral information printed directly on the back of the pack (). This adaptation helped the project team to understand that a backpack innovation could have broader implications in helping housing secure individuals and meeting the needs of community partners.

4. Discussion

The C2C pilot project provides many opportunities and lessons for designing innovations to address complex social problems that require action in local communities. The combination of tangible product, policy and practice design provides for a multifaceted examination of human connection and impact, particularly in the area of health and human services (Beckett et al. Citation2018).

4.1. Tangible design as a linking and sustaining innovation

This case study illustrates how design and policy innovations at the nexus of public health practice, education and research can address the SUD crisis, a global issue. Calls for implementation research to study SUD treatment and other innovations include frameworks to “design implementation strategies, effectively adapted to the broad context” that include “design and testing of predictive models to assess likelihood of effective implementation and prospects for sustainability while taking into account salient contextual factors” (Damschroder and Hagedorn Citation2011, 194). While not a treatment innovation, the backpack designed through the project facilitated access to SUD treatment and could be considered an adaptable component of an evidence-based innovation in this context.

Design is best achieved when integrating broad expertise; to maximize social and cultural impact as a designer, it is important to not only consider the lifecycle of a product, but also an appropriate business model (Bocken et al. Citation2016). In identifying a target market and commercial production model for the C2C backpack, social impact investing, cross-subsidization, and charitable giving models are considered. Product-cost cross-subsidization is the strategy of pricing a product above its market value to subsidize the loss of pricing another product below its market value (Price Citation2022). Cross-subsidization models can make products and services more accessible for low-income, base-of-the-pyramid (BoP) customers (Jahani and West Citation2015). In some cases, it can also lead to inefficient production as a competitive market may not be able to sustain the initial charitable investment over the long run.

New or high-demand items may fetch a higher-than-average market price to partly subsidize the same backpack to be sold for below-average market price to vulnerable populations. A variation of this is to sell a “deluxe version” of the backpack, with extra, non-essential features, to the more affluent consumer in order to subsidize the production and donation of a “basic essentials” backpack to the target population. Other potential pricing schemes to support the production of the C2C backpack include a buy one, donate one model, where the customer pays a retail price that covers the cost of a second backpack for donation to the target population. The “one-for-one” philosophy has been growing since Toms Shoes popularized it starting in 2008 (Frenkel Citation2012). In another pricing model, the backpack could be sold at a sliding scale price based on the customer’s ability or willingness to pay, with a set minimum price in place to recoup some or all of the production costs. Other opportunities to finance production of the backpack include grants, fundraising and crowdsourcing, organizational and customer memberships, and business co-operatives. Partnering with high profile corporate partners in the outdoor textile and equipment industry could attract financial backing and increase public awareness of the product.

In each of these pricing models, consumer education about the multipurpose function of the backpack and the social value of the backpack purchase will likely attract customers who believe in the cause and may increase their willingness to pay for the product. In addition, the customer must trust that their contributions are being directed to the cause. This trust can be cultivated by showcasing backpack recipient stories, creating an online website where the customer can learn more, and having transparent mechanisms in place for the customer to see the impacts of their specific donation, such as having a backpack registry or a featured local organization each month that will receive donated backpacks to distribute to the target population.

There is also, however, potential for a social impact product to be undercut by competitors who can more cheaply sell the new, high-demand, or deluxe items. It can lead to a race to the bottom to source items as cheaply as possible in order to make the largest profit margin for the charitable cause, which could have labor rights and environmental resource implications. Mission drift can also occur as the enterprise scales up (Brest and Born Citation2013). Remaining true to the mission and integrating opportunities for input from the target population as well as customers, setting up mechanisms for convenient product repair, using sustainable materials, such as hemp, closing the loop through material recycling and reuse, and ensuring fair labor conditions to produce the bags will signal a comprehensive commitment to social impact.

4.2. Implications for design and policy research and praxis

The C2C project innovations of improving linkages to harm reduction, treatment and recovery services served to uncover and better understand perceptions and different points of view related to the causes of and solutions to addiction and substance use harms. Many stakeholders involved in harm reduction and treatment services value meeting the individual with addiction where they are in their readiness for treatment, advocating that harm reduction to keep individuals alive and as healthy as possible is part of the continuum of care (SAMHSA Citation2022). However, first responders and ED providers who witness a revolving door of crisis among the same group of individuals may desire to push the individual from where they are into treatment. For instance, during early engagement with the RVCR, some law enforcement representatives suggested a policy that would force civil commitment to residential treatment for individuals with addiction. Those at the nexus of policy and practice design have the opportunity to bridge these differences without forcing constituents to reside on one side of the bank or the other.

4.2.1. Bridging ideological differences

Implementing policy and programs across ideological differences is often a noted complexity of governance in a distributed federalist system, where policies that become authorized and normalized in one locality may not be legal or valued in another (Cerna Citation2013). At one point of early engagement with the RVCR, a harm reduction advocate suggested an emerging program known as Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD), where police officers are given discretionary authority to direct those committing minor crimes to community-based services, rather than arrest and incarceration (LEAD Bureau Citation2022). As observed by a C2C project team member, the response of a criminal justice representative was, “well, this is not Seattle, Washington!” implying that while a practice and policy may be promising in one locality, local stakeholders need to be well-informed of its pros and cons and ready to adopt it in the local context. An effective engagement practice is to bring peer professionals who have successfully adopted in innovative practice in one locality, to engage with their peers in the community considering implementation. However, it is important to consider whether the same policy, resource and cultural contexts are relatable as well (Sallis et al. Citation2006).

4.2.2. Balancing control and flexibility in innovation

Another challenge in establishing a community-centered and evidence-based study for new innovations is the difficulty of conducting longer-term, quasi-experimental and semi-controlled studies with the target population, including individuals who are hesitant to enroll and remain in studies due to fear of criminal charges for active substance use, or unstable living conditions leading to attrition (Scott Citation2004). The formative work done to date by the research and design team included an iterative/agile process to define and redefine the criteria with which to evaluate preliminary impacts of the program innovations, including the backpack and referral cards, as well as the peer recovery specialists embedded in the community. By partnering with community organizations in direct contact with the target population, the research team is now exploring how this formative work in building trust and program recognition can lead to more formal, longitudinal studies in the future (Zhang et al. Citation2014).

As a pilot program, the C2C project has been intentionally nimble in applying and adjusting linking innovations as needed in response to stakeholder and community needs. In addition to the primary adjustments made during the early implementation phase and reflected on previously, other modifications including additional product design, enabling partner discretion, and expanding Naloxone distribution and access. With the grant extension, the research team was also able to support a study of recovery housing needs and launch two additional pilot initiatives. As discussed in Section 3.3 adaptations of the lite backpack and flexibility of partners to determine whether and how to include Narcan or naloxone, provided responsiveness to community needs, and the partners ability to best meet individual needs. These nuances manifested through ongoing conversation with community partners and led to iterative product development and distribution strategies to address each of these concerns, reflecting convergent and divergent design process principles (Design Council Citation2022).

4.2.3. Rewards in policy and program design

For some stakeholders, the backpacks were perceived as “rewards” for the criminalized behavior of drug use, illuminating the need for further policy regarding professional engagement and cross agency education of healthcare and community service providers on effective strategies to engage people with SUD treatment. Lack of trust of authority figures and healthcare providers due to negative past experiences can impede individuals in active use from seeking help (Havnes and Skogheim Citation2020). Related to rewards as a linking mechanism, recent evidence suggests that contingency management, which encourages individuals with small monetary sums to stay engaged in treatment innovations, increases individuals’ participation in group therapy and treatment, particularly for cocaine and/or amphetamine stimulant addictions (Davis et al. Citation2016; De Crescenzo et al. Citation2018; Goodnough 2020). Stimulant addictions are not currently widely treated with medication-assisted treatment (MAT) using the same FDA-approved medications for opioid addictions, and thus pose a significant treatment and recovery challenge. Fairley et al. (Citation2021) note that “clinicians should aim to provide whatever MAT is feasible in their setting and to supplement it with CM [contingency management]. Following the model of the Affordable Care Act, policy makers can support these efforts by establishing these treatments as permanent, adequately remunerated benefits in public insurance programs (e.g. Medicaid and Medicare) and by enforcing parity regulations that require its coverage in private insurance programs. Expanding CM would also be facilitated by exempting the small rewards it provides to patients from anti-kickback provisions in state and federal law” (774).

Following the same principles as contingency management, when individuals receive a backpack stocked with useful supplies from a harm reduction organization, the local jail during their release from incarceration, or from a medical provider in the ER upon discharge, it may improve the individuals’ experience interacting with these community stakeholders and mitigate potential for new trauma. In the case of the harm reduction organization, the goal is that the backpack recipient will have a positive perception of the visit and so will want to return to seek out additional harm reduction supplies, support, and to eventually request a referral to a treatment provider.

4.2.4. Launching new initiatives

Throughout the pilot project timeframe, C2C project stakeholders have consistently identified housing as a significant barrier to achieving the stability necessary for individuals to reduce substance use and be successful in treatment and recovery. The COCLI grant no-cost extension allowed the C2C research team to partner with the RVCR to conduct an assessment of the recovery housing needs in the Roanoke Valley region and to develop preliminary strategies to address housing needs. The study is currently being used to support implementation of the proposed strategies by a special workgroup of the RVCR.

The backpack and referral cards served as tangible symbols of a multi-stakeholder partnership and linking mechanism focused on increasing access to harm reduction resources, peer recovery specialists, and treatment options for individuals with SUDs. The ongoing cross sector engagement and exploration of gaps in services among stakeholders has resulted in several additional pilot programs, including a Reentry to Recovery forensic discharge planning program between the regional jail and local treatment providers, as well as a Responders for Recovery pilot program between a local EMS agency and a community health clinic that connects peer recovery specialists to individuals involved in a SUD-related emergency response (White et al. 2020).

These pilots aim to close gaps in the continuum of care where individuals who are at high risk of relapse or overdose, such as upon release from incarceration or following a previous overdose incident, are more directly connected to resources and make personal contact with treatment providers and peer recovery specialists. Initial evaluation of the pilots as well as findings from the literature suggest these innovations should be formally integrated into correctional facilities and EMS protocols and codified in state and federal policy to build systemic capacity (Champagne-Langabeer et al. Citation2020; SAMHSA Citation2017).

5. Conclusion and next steps

The intentional C2C design as formative and adaptive in nature has led to expansion of innovations and additional pilot projects. These expansions are reflective of the C2C research team and stakeholders’ improved understanding that to improve the connection between people with SUD and the community, the team needs to consider range and complexity of factors impacting this population’s vulnerabilities, such as homelessness, lack of resources, incarceration, history of trauma and stigma, and educational and vocational challenges that limit individual potential and external relationships (Miller-Archie et al. Citation2019). While much attention is focused on individual risks, the team also needs to understand the opioid crisis in a broader societal context. In each step of development, there is room for modifications based on the various variables related to the unique needs of each community.

The research team is investigating other design strategies for increasing access to Narcan, such as installing vending machines in highly-trafficked areas used by the target population and/or their friends and family members. One impediment to doing so remains state-level policy regarding how distribution of the medication is tracked for each individual who receives it, which is both a confidentiality and data management challenge. Evaluating the efficacy of the vending machine concept, such as tracking the amount of Narcan distributed and more critically, extrapolating the number of overdoses reversed as a result (Langham et al. Citation2018), can inform standard policy regarding the placement and implementation of the vending machines as a design innovation.

We intend to seek additional funding to support innovations initiated during the pilot program; the goal is to gain more empirical knowledge of the touchpoints that lead to successful access to services, and ultimately, treatment and recovery. While it is increasingly understood that long-term wellness is best accomplished through a recovery ecosystem that addresses the multiple levels of the continuum of care, and the context of that continuum in the local community and the, getting there requires thoughtful and collective design of programs, policy and products that support individual and community well-being.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Akshay Sharma for his support at the beginning of this collaboration, as well as the Virginia Harm Reduction Coalition, HOPE Initiative of the Bradley Free Clinic, and Council of Community Services’ Drop-In Center North for providing invaluable user level input into the backpack design.

We would also like to show our gratitude to the Industrial Design Student Team: Blythe Row, Anna DiNardo, Connor Howerton, Cristina Dunning, and Wesley Rogers for their dedication during the design phase and also their generosity in allowing the use of their design to move forward with this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Botetourt, Craig, Franklin, and Roanoke Counties, and Roanoke and Salem Cities.

2 Substance Use Disorder (SUD) includes Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). In this article, the terms SUD and addiction are used interchangeably.

3 This work was supported in part by a Virginia Tech Vibrant Virginia seed grant program. Author Mary Beth Dunkenberger was the principal investigator on the grant, which provided research and technical assistance from July 2018 to June 2019.

4 In the Fall of 2018, the RVCR workgroup was known as the “Overdose Reversal” workgroup. Following further assessment and strategy development and in advance of publishing the RVCR Blueprint for Action, the name was changed to Crisis Response and Connection to Care in early 2020, following the late 2019 funding of the C2C pilot.

5 Naloxone is a medicine that rapidly reverses an opioid overdose; working as an opioid antagonist, it attaches to opioid receptors and reverses and blocks the effects of other opioids (NIH 2022).

6 Elham Morshedzadeh, along with Akshay Sharma, advised and supervised the ID students involved in engaging with the target population and designing the backpack prototype.

7 Author Mary Beth Dunkenberger served as the principal investigator on the grant program, and authors Elham Morshedzadeh, Lara Nagle, Laura York, and Kimberly Horn served as co-investigators.

References

- Altekruse, S. F., C. M. Cosgrove, W. C. Altekruse, R. A. Jenkins, and C. Blanco. 2020. “Socioeconomic Risk Factors for Fatal Opioid Overdoses in the United States: Findings from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities Study (MDAC).” PLOS One 15 (1): e0227966. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227966.

- American Medical Association. 2022. “Issue Brief: Nation’s Drug-Related Overdose and Death Epidemic Continues to Worsen.” Accessed March 19, 2022. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwja64W_tNX2AhXWpXIEHeJjBW0QFnoECAIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ama-assn.org%2Fsystem%2Ffiles%2Fissue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0DQKN_6oeBkFNl3gPjywUb

- Ashford, R. D., A. M. Brown, R. Ryding, and B. Curtis. 2020. “Building Recovery Ready Communities: The Recovery Ready Ecosystem Model and Community Framework.” Addiction Research & Theory 28 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/16066359.2019.1571191.

- Baumgartner, J., and D. Radley. 2021. “The Spike in Drug Overdose Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Policy Options to Move Forward.” The Commonwealth Fund. Accessed March 20, 2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2021/spike-drug-overdose-deaths-during-covid-19-pandemic-and-policy-options-move-forward

- Beckett, K., M. Farr, A. Kothari, L. Wye, and A. Le May. 2018. “Embracing Complexity and Uncertainty to Create Impact: exploring the Processes and Transformative Potential of co-Produced Research through Development of a Social Impact Model.” Health Research Policy and Systems 16 (1): 118. doi:10.1186/s12961-018-0375-0.

- Bocken, N. M., I. De Pauw, C. Bakker, and B. Van Der Grinten. 2016. “Product Design and Business Model Strategies for a Circular Economy.” Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering 33 (5): 308–320. doi:10.1080/21681015.2016.1172124.

- Brest, P., and K. Born. 2013. “Unpacking the Impact in Impact Investing.” Stanford Social Innovation Review, August 14. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/unpacking_the_impact_in_impact_investing

- Brown, T., and J. Wyatt. 2010. “Design Thinking for Social Innovation.” Development Outreach 12 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1596/1020-797X_12_1_29.

- CDC. 2021. “Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Top 100,000 Annually.” U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed March 19, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm

- Cerna, L. 2013. The Nature of Policy Change and Implementation: A Review of Different Theoretical Approaches. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Report, 492–502.

- Champagne-Langabeer, T., C. Bakos-Block, A. Yatsco, and J. R. Langabeer. 2020. “Emergency Medical Services Targeting Opioid User Disorder: An Exploration of Current out-of-Hospital Post-Overdose Innovations.” Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open 1 (6): 1230–1239. doi:10.1002/emp2.12208.

- Chen, E., C. Leos, S. D. Kowitt, and K. E. Moracco. 2020. “Enhancing Community-Based Participatory Research through Human-Centered Design Strategies.” Health Promotion Practice 21 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1177/1524839919850557.

- Conlan, T. 2006. “From Cooperative to Opportunistic Federalism: Reflections on the Half‐Century Anniversary of the Commission on Intergovernmental Relations.” Public Administration Review 66 (5): 663–676. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00631.x.

- Damschroder, L. J., and H. J. Hagedorn. 2011. “A Guiding Framework and Approach for Implementation Research in Substance Use Disorders Treatment.” Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 25 (2): 194–205. doi:10.1037/a0022284.

- Davis, D. R., A. N. Kurti, J. M. Skelly, R. Redner, T. J. White, and S. T. Higgins. 2016. “A Review of the Literature on Contingency Management in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders, 2009–2014.” Preventive Medicine 92: 36–46. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.008.

- Dawson-Rose, C., D. Shehadeh, J. Hao, J. Barnard, L. L. Khoddam-Khorasani, A. Leonard, K. Clark, et al. 2020. “Trauma, Substance Use, and Mental Health Symptoms in Transitional Age Youth Experiencing Homelessness.” Public Health Nursing 37 (3): 363–370. doi:10.1111/phn.12727.

- De Crescenzo, F., M. Ciabattini, G. L. D'Alò, R. De Giorgi, C. Del Giovane, C. Cassar, L. Janiri, N. Clark, M. J. Ostacher, and A. Cipriani. 2018. “Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Psychosocial Innovations for Individuals with Cocaine and Amphetamine Addiction: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis.” PLOS Medicine 15 (12): e1002715. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002715.

- Des Jarlais, D. C. 2017. “Harm Reduction in the USA: The Research Perspective and an Archive to David Purchase.” Harm Reduction Journal 14 (1): 51. doi:10.1186/s12954-017-0178-6.

- Design Council. 2017. “1617 Annual Report and Accounts.” https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/Design%20Council%201617%20Annual%20Report%20and%20Accounts%20MASTER%2020170808%20SIGNATURES%20%28002%29_0.pdf

- Design Council. 2022. “What Is the Framework for Innovation? Design Council’s Evolved Double Diamond.” https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/what-framework-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond

- Dineen, K. K. 2016. “Addressing Prescription Opioid Abuse Concerns in Context: synchronizing Policy Solutions to Multiple Complex Public Health Problems.” Law and Psychology Review 40: 1+.

- Fairley, Michael, Keith Humphreys, Vilija R. Joyce, Mark Bounthavong, Jodie Trafton, Ann Combs, Elizabeth M. Oliva, et al. 2021. “Cost-Effectiveness of Treatments for Opioid Use Disorder.” JAMA Psychiatry 78 (7): 767–777. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0247.

- Feldscher, K. 2022. “What Led to the Opioid Crisis—And How to Fix It.” Harvard School of Public Health. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/features/what-led-to-the-opioid-crisis-and-how-to-fix-it/

- Frenkel, K. A. 2012. “Clothing That Fights Homelessness Also Fights The One-For-One Model.” Fast Company, August 31. https://www.fastcompany.com/1680415/clothing-that-fights-homelessness-also-fights-the-one-for-one-model

- Goodnough, A. (2020). This Addiction Treatment Works. Why Is It So Underused? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/27/health/meth-addiction-treatment.html

- Han, B., W. M. Compton, C. Blanco, E. Crane, J. Lee, and C. M. Jones. 2017. “Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.” Annals of Internal Medicine 167 (5): 293–301. doi:10.7326/M17-0865.

- Havnes, I. A., and T. S. Skogheim. 2020. “Alienation and Lack of Trust: Barriers to Seeking Substance Use Disorder Treatment among Men Who Struggle to Cease Anabolic-Androgenic Steroid Use.” Journal of Extreme Anthropology 3 (2): 94–115. doi:10.1177/00914509211058989.

- IDEO. 2015. “Community.” Ideo.com. https://www.ideo.com/jobs/community

- Israel B. A., E. Eng, A. J. Schulz, and E. A. Parker, eds. 2012. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass.

- Jahani, M., and E. West. 2015. “Investing in Cross-Subsidy for Greater Impact.” Stanford Social Innovation Review, May 27. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/investing_in_cross_subsidy_for_greater_impact

- Jalali, M. S., M. Botticelli, R. C. Hwang, H. K. Koh, and R. K. McHugh. 2020. “The Opioid Crisis: A Contextual, Social-Ecological Framework.” Health Research Policy and Systems 18 (1): 87. doi:10.1186/s12961-020-00596-8.

- Khoury, L., Y. L. Tang, B. Bradley, J. F. Cubells, and K. J. Ressler. 2010. “Substance Use, Childhood Traumatic Experience, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in an Urban Civilian Population.” Depression and Anxiety 27 (12): 1077–1086. doi:10.1002/da.20751.

- Langham, S., A. Wright, J. Kenworthy, R. Grieve, and W. Dunlop. 2018. “Cost-Effectiveness of Take-Home Naloxone for the Prevention of Overdose Fatalities among Heroin Users in the United Kingdom.” Value in Health 21 (4): 407–415. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.07.014.

- LEAD Bureau. 2022. “How Does LEAD Work?” LEAD National Support Bureau. https://www.leadbureau.org/about-lead

- Martinez, L. S., B. D. Rapkin, A. Young, B. Freisthler, L. Glasgow, T. Hunt, P. J. Salsberry, et al. 2020. “Community Engagement to Implement Evidence-Based Practices in the HEALing Communities Study.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 217: 108326. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108326.

- McNaughton, C. C. 2008. “Transitions through Homelessness, Substance Use, and the Effect of Material Marginalization and Psychological Trauma.” Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 15 (2): 177–188. doi:10.1080/09687630701377587.

- Miller-Archie, S. A., S. C. Walters, T. P. Singh, and S. Lim. 2019. “Impact of Supportive Housing on Substance Use–Related Health Care Utilization among Homeless Persons Who Are Active Substance Users.” Annals of Epidemiology 32: 1–6.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.002.

- NIH (National Institutes of Health) 2022. What is Naloxone? National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/naloxone

- Norman, D., and E. Spencer. 2019. “Community-Based, Human-Centered Design.” Jnd.Org. https://jnd.org/community-based-human-centered-design/

- Park, C., M. Wilding, and C. Chung. 2014. “The Importance of Feedback: Policy Transfer, Translation and the Role of Communication.” Policy Studies 35 (4): 397–412. doi:10.1080/01442872.2013.875155.

- Peppin, J. F., R. B. Raffa, and M. E. Schatman. 2020. “The Polysubstance Overdose-Death Crisis.” Journal of Pain Research 13: 3405–3408. doi:10.2147/JPR.S295715.

- Pettersen, H., A. Landheim, I. Skeie, S. Biong, M. Brodahl, J. Oute, and L. Davidson. 2019. “How Social Relationships Influence Substance Use Disorder Recovery: A Collaborative Narrative Study.” Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment 13: 1178221819833379. doi:10.1177/1178221819833379.

- Price, K. R. 2022. “What Is Product-Cost Cross-Subsidization?” Chron. Houston Chronicle. https://smallbusiness.chron.com/productcost-crosssubsidization-81079.html

- RVCR Blueprint. 2020. https://www.rvcollectiveresponse.org/resources

- Sallis, J. F., R. B. Cervero, W. Ascher, K. A. Henderson, M. K. Kraft, and J. Kerr. 2006. “An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communities.” Annual Review of Public Health 27: 297–322. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100.

- SAMHSA. 2017. “Guidelines for Successful Transition of People with Mental or Substance Use Disorders from Jail and Prison: Implementation Guide.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma16-4998.pdf

- SAMHSA. 2022. “Harm Reduction.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/harm-reduction

- Scott, C. K. 2004. “A Replicable Model for Achieving over 90% Follow-up Rates in Longitudinal Studies of Substance Abusers.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 74 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.007.

- Smiley-McDonald, H. M., P. R. Attaway, N. J. Richardson, P. J. Davidson, and A. H. Kral. 2022. “Perspectives from Law Enforcement Officers Who Respond to Overdose Calls for Service and Administer Naloxone.” Health & Justice 10 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/s40352-022-00172-y.

- Stone, D. 2012. “Transfer and Translation of Policy.” Policy Studies 33 (6): 483–499. doi:10.1080/01442872.2012.695933.

- VDBHDS (Virginia Department of Behavioral Health & Developmental Services) 2022. “REVIVE! Opioid Overdose and Naloxone Education (OONE) Program for the Commonwealth of Virginia.” https://dbhds.virginia.gov/behavioral-health/substance-abuse-services/revive/

- Virginia Department of Health. 2021. “Opioid Data.” December 15. https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/opioid-data/

- Wallerstein, N. B., and B. Duran. 2006. “Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities.” Health Promotion Practice 7 (3): 312–323. doi:10.1177/1524839906289376.

- Wheeler, E., T. S. Jones, M. K. Gilbert, and P. J. Davidson. 2015. “Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons—United States, 2014.” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64 (23): 631–635. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm

- White, M. D., D. Perrone, S. Watts, and A. Malm. 2021. “Moving beyond Narcan: A Police, Social Service, and Researcher Collaborative Response to the Opioid Crisis.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 46 (4): 626–643. doi:10.1007/s12103-021-09625-w.

- Zhang, Q., I. Deniaud, C. Baron, and E. Caillaud. 2014. “Managing Uncertainty in Innovative Design: Balancing Control and Flexibility.” In IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems, 313–319. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer.