Abstract

Over the last decade, a growing body of research has explored the potential of applying design approaches within policymaking, resulting in the emergence of a novel practice, termed ‘design for policy’. While largely successful, questions remain regarding the specifics of the design for policy process. In this, key points of contention relate to the way government-citizen deliberation and collaboration is framed (i.e., who gets to participate in design for policy initiatives and how), as well as the of the role of design within the process (i.e., is it a means of problem-solving or problem-framing). Responding to these challenges by examining the potential of a specific design approach—Participatory Design (PD)—in design for policy, the present article turns to the Scottish policymaking context. Here, we present a case study of a project titled Social Studios, which explored how PD might enable communities to better approach Participation Requests (PRs)–a mechanism within the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act (2015) that allows groups to engage with public authorities on local issues relating to infrastructure and services. From an initial overview of the context of the study, we describe its methods, process and, finally, its outcome—a bespoke ‘PR Toolbox’. The article then closes with a series of reflections on the broader potential of PD in the context of design for policy.

1. Introduction

The last decade has seen the emergence of design for policy; a novel practice which aims to integrate the creative approaches of design within traditional policymaking, thus allowing for a more creative, open, and agile policymaking process (Whicher and Swiatek Citation2022; Bason Citation2016). Contributing to this discourse and aiming to extend the design for policy evidence base, this article examines the potential of applying a particular design approach—Participatory Design (PD)—in the context of design for policy.

PD has a rich history of social and political intervention, which aligns well with a design for policy context. However, as yet, the approach has not received significant attention here (Dixon Citation2020; Dixon, McHattie, and Broadley Citation2022). Seeking to address this, we present a case study of a PD-based design for policy project titled ‘Social Studios’, which was undertaken in Scotland. As we outline below, the current Scottish policymaking context affords a number of promising opportunities for creative experimentation that, in turn, enable such work. Through the presentation of the Social Studios case study, we demonstrate PD’s viability as a design for policy strategy, as well as trace a series of reflections on its wider potential within this domain.

The article begins by briefly outlining the present design for policy context and, alongside this, the development and structure of PD as a design approach. Here, a brief argument is made as to the potential of PD in the context of design for policy, focusing on its democratic underpinnings. As a means of exploring this, we then present the Social Studios case study. From an initial overview of the Scottish context of the study, we describe its methods, process and outcome—a toolbox. Then, as a means of closing, we provide our reflections on the potential of PD in design for policy.

2. Policy problem: design’s role in policymaking and the potential of participatory design

The emergence of design for policy responds to a perceived need to better integrate citizen involvement within policymaking processes (Burkett, Citation2012, 5; Blomkamp, Citation2018, 738; Vesnić-Alujević et al., Citation2019, 7). On this account, design supports creative modes of deliberation and collaboration between governments and citizens, which, in turn, may progress public sector reform and innovation (Bason Citation2016). While the approach is not yet fully defined, a growing body of literature has begun to scope its potential value. Here, it is said to allow for the surfacing of citizens’ lived experiences and aspirations (Christiansen and Bunt, Citation2014; Siodmok, Citation2014); the capturing of dialogue and insight as a resource upon which to redefine ways of living (Manzini Citation2015); the navigation of complex public services and systems (Halse et al., Citation2010); and the prototyping of prospective policy initiatives (Kimbell and Bailey, Citation2017).

While the latter contributions suggest a great deal of promise, questions remain regarding the way in which government-citizen deliberation and collaboration is framed, as well as how the role of design is understood. For example, Bailey (Citation2017) critiques the top-down (i.e., government-led) orientation of recent design for policy initiatives; while Junginger (Citation2014) notes that traditional policymaking can demote design to a mode of problem-solving. Next to these issues, the public sector has also been found to exhibit a general resistance to both creative experimentation and power-sharing (Bradwell and Marr Citation2008). Further, such tensions are exacerbated by research outcomes that claim to deliver standardized policymaking methods and tools for governments (Christiansen and Bunt, 2014; Kimbell and Vesnić-Alujević Citation2020). This raises questions surrounding design’s contribution to investigating the inherently political issues at stake in the process of planning for the future.

There is no obvious solution to the above challenges. Nonetheless, it is arguable that the specifics of the design approach applied may go some way toward addressing many of the concerns highlighted. For example, rather than pursuing a government-led strategy, one might seek out a citizen-led approach; rather than mere problem solving one might seek out an approach which allows for ‘problem-framing’. In this vein, the present paper examines the potential of a PD-based approach to design for policy. As was noted in the opening, PD has not yet received much attention in design for policy but nonetheless—due to its strong democratic roots—has been identified as worthy of special consideration within this context (Dixon Citation2020; Dixon, McHattie, and Broadley Citation2022).

3. Participatory design

In its most essential form, PD sees designers work directly with stakeholders to explore contextual challenges and collectively prototype (i.e., create and test) possible responses iteratively (Telier et al. Citation2011). Stakeholders are here participant co-creators, who actively contribute to the process of designing appropriate solutions (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008, 12).

The movement has a rich heritage, first emerging in the context of a series of trade union-led research projects undertaken in Scandinavia in the 1960s and 1970s. This work was, above all, motivated by a desire to address power imbalances and regain human accountability in light of technological advancements in workplace settings (Bjerknes, Ehn, and Kyng Citation1987). As a result, a commitment to democratic decision-making became a defining characteristic of the movement (Telier et al. Citation2011, 153).

In recent years, PD project work has expanded in all manner of social contexts, including distributed urban communities (DiSalvo, Clement, and Pipek Citation2012). In this, it can be seen to share much with other general co-creation approaches and standard applications of co-design which seek to enable shared transformative inquiries (Steen Citation2011). Distinguishing it from the latter however is its ongoing democratic and, indeed, political commitment. This can be seen to take form through a challenging of existing power structures, as well as a questioning of the ways in which communities are defined and supported (or not) in their efforts to achieve particular ends (Bannon et al. Citation2018).

It is our view that the potential of PD in the context of design for policy relates primarily to this requirement that focus be directed toward communities’ needs and, next to this, its commitment to support efforts to formulate an appropriate response, recognizing and challenging power imbalance where necessary. In order to consider this further we now turn to our case, Social Studios. Here, we will first move to frame its specific policy context, wherein challenges relating to community participation in local governance in Scotland were identified and problematized.

4. The social studios context: Scotland, the community empowerment act and participation requests

Since the establishment of the devolved Scottish parliament in 1999, Scotland has embarked on a rich programme of creative political experimentation. Within this, some have claimed that a particular, ‘Scottish style’ of policymaking has emerged, focused on consensus-seeking through consultation (Cairney Citation2017; Cairney and St Denny Citation2020). While it has been argued that this style is largely comparable to that of the UK’s in general (Cairney Citation2021), it has nonetheless given rise to a series of noteworthy ‘democratic innovations’. There has, for example, been a trialing of ‘mini-publics’, i.e., small-scale, randomized assemblies of citizens who are systematically consulted on key issues (Escobar and Elstub Citation2017). Equally, the Scottish civil service has explored the potential of embedding service design approaches in policymaking regarding the ‘definition, design and delivery of public services’. This too has been contextualized as a distinct ‘Scottish’ approach (The Scottish Government Citation2019).

A further significant initiative can be found in the flagship Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 (CEA), which aims to support community participation in planning, public service delivery, and development processes (The Scottish Government Citation2015, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Though the CEA is not unique in an international context, it can be distinguished in relation to the degree to which it advances the possibility of community participation in the political process (Elliot Citation2014).

A primary example of this is to be found in Participation Requests (PRs), a point of focus for the case that follows. In simple terms, PRs function as a mechanism within the CEA which allow organized communities—here referred to as ‘community participation bodies’ (CPB)—to actively ‘enter into dialogue with public authorities about local issues/services on their terms’. In doing so, a CPB is requesting that an ‘outcome improvement process’ (OIP) be launched with a relevant ‘public service authority’ (PSA) in order that a specific, pre-identified challenge be addressed (The Scottish Government Citation2017b: 8).

Though aspects of the CEA and its PR mechanism have been welcomed, some key issues have emerged. In relation to PRs in particular, early research has identified a number of concerns relating to processes of implementation. These include the need to increase access for a broader range of communities and less formally-organized groups; the need to improve transparency and understanding in PR guidance to combat skepticism and ambiguity; and the need to build people’s confidence and capabilities in order that they may play an active role in their communities (Paterson Citation2018; Plotnikova and Bennett Citation2018; Hill O’Connor and Steiner Citation2018).

Evaluations of PRs also underline a tendency for standardized community engagement approaches to reproduce the participation of high-capacity communities over those who are marginalized (McMillan, Steiner, and Hill O’Connor Citation2020). Recognizing an upsurge of collaborative processes and institutions developing democratic innovations within formal policymaking contexts, Bennett et al. (Citation2022, 2-3) suggest PRs can be understood to function as a form of governance-driven democratization (Warren Citation2009, 3), a legal tool characterized by a prescriptive centralized process. This can be seen to limit public engagement in PRs to established, experienced community groups and perpetuate a model of participation capable of being skewed and misappropriated by local public service officials. As a corrective, the group proposes that such democratic innovations be ‘co-produced between (various) institutions and communities’ in order to ‘temper dominant bureaucratic logics’ (Bennett et al. Citation2022, 3).

This is a fair proposition. Indeed, tracing the CEA’s origins in the Scottish Community Empowerment Action Plan (The Scottish Government Citation2009), we note an advocacy for the ‘process of community empowerment’ to evoke communities’ imaginative potential, such that they might be enabled to ‘come up with creative and successful solutions to local challenges’ (The Scottish Government Citation2009, 6). However, the eventual CEA, and specifically its presentation of PRs, does not posit creativity as a route toward or a quality of empowerment. This latter realization led to the initial framing of Social Studios, which positioned a PD-based creative approach as a means of addressing equality and empowerment in the context of PRs, thus developing an exemplar of PD in a design for policy space.

5. Social studios

Social Studios was conducted within a Research Incentive Grant funded by the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland between March 2020 and March 2022. The project aimed to examine how PD can support people, communities, and PSAs in the preparation, submission, and implementation of PRs. Here, as an outcome, it was proposed that a potential PR Toolbox might be developed to support future PRs. As an additional aim, Social Studios also sought to examine the potential of PD in a design for policy context.

Due to Covid-19 restrictions, the research proceeded via a distributed virtual approach. This involved a series of semi-structured scoping interviews carried out with key stakeholders from community development, academia, and The Scottish Government working in the emerging field of PRs. These interviews were followed by a series of seven Social Studios—interactive workshops applying a range of PD methods, which made use of both digital and analogue strategies to elicit, capture, and reimagine PR experiences and interactions. Supported by the Scottish Community Development Center (SCDC) as an intermediary organization, recruitment for the workshops sought to engage a range of communities with experience of submitting PRs and PSAs who are involved in supporting these at a local level.

Twelve community representatives who had previously submitted a PR responded to the call for participation.

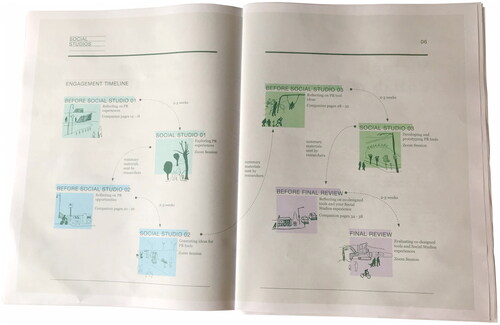

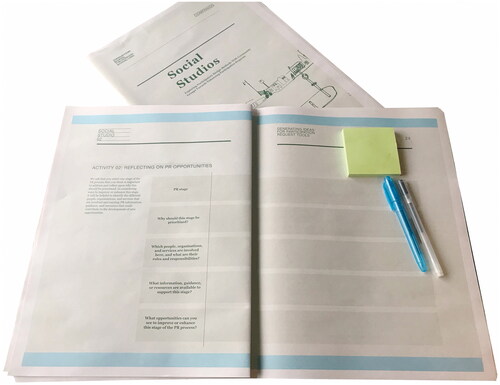

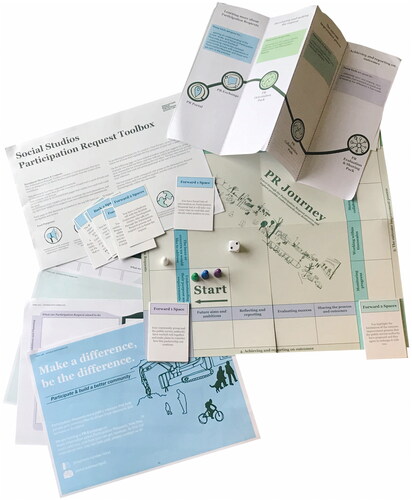

A qualitative and iterative participatory action research methodology was developed to support dialogue, action, and reflection with partners and participants, drawing from their experiential learning and expertise to develop new knowledge (Howard and Somerville Citation2014). Recognizing distinctions between participation that is live, synchronous, and discursive, and that which is cumulative, asynchronous, and reflective, the methodological approach developed bespoke PD methods to support remote dialogue (Broadley Citation2021; Broadley and Smith Citation2018). Support materials included a Social Studios Companion Workbook and Kit ( and ), which offered material resources to aid both understanding of the technical background to PRs and support the creative process. Participants also had access to the online whiteboard tool Miro. Combined, these digital and analogue methods sought to capture experiences, insights, and aspirations through mapping exercises, interactive probes, and generative making activities.

Figure 1. Social studios companion: setting out the distributed engagement approach. 2021. Cara Broadley and Sean Fegan.

Figure 2. Social studios companion: methods and materials to support asynchronous reflection. 2021. Cara Broadley and Sean Fegan.

The core of the research was structured around the following three phases, which were each punctuated by formative and iterative stages of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006).

Phase 01: Contextual Immersion – This phase centered on the virtual interviews, which explored the challenges and opportunities surrounding PRs and allowed for the articulation of a set of criteria to define effective PR tools (May – October 2020).

Phase 02: Social Studios—This phase centered on the development and delivery of a series of virtual workshops. Alongside exploring PR challenges and opportunities, workshops focused on co-designing, iterating, and evaluating PR tools (October 2020–June 2021).

Phase 03: Analysis, Evaluation, and Dissemination—This phase centered on the virtual evaluation of PR tools with key stakeholders. The team also worked to define the core research insights and reflections concerning the potential of PD within the context of policymaking (July 2021–March 2022).

Recognizing and underscoring their deep and immediate creative involvement, participants in Phase 02 are identified as ‘co-designers’, i.e., individuals who are jointly contributing to the unfolding of the inquiry (Steen Citation2011).

From the above overview, we will now turn to consider the key interview and workshop insights, which emerged in relation to PRs.

6. Discussion: the insights of social studios’ interviews and workshops

The interviews and Social Studios workshops of Phases 01 and 02 explored both the challenges and opportunities associated with PRs. The challenges were broad ranging. As a key general challenge, participants highlighted a range of concerns relating to equality of access. Here, many noted that PRs are often deemed a ‘formal and closed process’ with fixed rules and regulations. In this, they also questioned the application of an official legislative method to further empower ‘well-heeled’ community groups with existing ‘networks, knowledge, and language at their disposal’ (Interview Participant 02). Such an insight correlates with the recognition that, as a legislative measure, PRs are markedly more accessible to constitutionally organized groups, with most having been submitted by community councils (Interview Participant 03).

Such critiques of the barriers to access and inclusion within PRs are unpacked by Bennett et al. (Citation2022). Their characterization of the mechanism as a foundational model of associative democracy in which ‘those invited to participate are community representatives or intermediaries from established community groups and associations’ (2021, 7) affirms PRs’ capacity to limit support to less formally-organized communities and people who do not self-identify with a defined group. This, in turn, increases the participation of the most active and vocal community members, perpetuating existing inequalities.

As another challenge, the relationship between the CEA and PRs was a core feature of all interviews. In discussing this issue, stakeholders questioned PRs’ efficacy as a singular (i.e., one-off) opportunity for action, along with their sustainability to strengthen ongoing collaborations. Tensions were also expressed regarding ‘the letter of the Act’ manifest in the formal legislation underpinning PRs, and the ways in which this can obstruct ‘the spirit of the Act’ to promote participation, the devolution of power to communities, and the realization of relational forms of governance (Interview Participant 02).

Skepticism regarding the intention of the general PR system also arose in the workshops, where participants offered critiques of state-led empowerment initiatives and policies that push responsibility onto people and communities without sufficient support or resources (Skerratt and Steiner Citation2013; Tabbner Citation2018). Such concerns are mirrored in the literature. For example, Bennett et al. (Citation2022) note that while the core principle of PRs is to locate the agency of community groups to engage on their own terms, the legislation is constructed upon a unidirectional system of engagement, in which PSAs decide whether a PR is accepted or not, define the duration and scope of the OIP, and produce a formal PR report (2021, 12). Equally, as Dean (Citation2017, 13) points out, public participation in policy can be seen to position people and communities as readily available repositories of information, rather than citizens with genuine needs and concerns of their own.

Linking to this set of concerns, the overarching role and accountability of PSAs in the process was also explored. Here, the co-designers highlighted the need for enhanced forms of training to equip PSAs with the practical skills required to work with communities equitably, as well as to understand the value of participation. They also highlighted the need for community groups to have the opportunity to align their experiences, assets, and aims to proposed outcomes within their PR and to have a role in shaping and driving the OIP.

A lack of clear definition around the concept of a PR ‘outcome’ was also highlighted as a challenge. In both the interviews and the workshops, concerns were raised that despite PRs’ intentions to support people and communities to collaborate with PSAs, varying interpretations of outcomes have resulted in misaligned ambitions and aims on both sides. While PR guidance posits outcomes as ‘the difference that has been made as a result of a service, an activity, or a policy decision’ (The Scottish Community Development Centre Citation2022b, 6), some PRs have been deemed ‘easy to refuse’ (Interview Participant 01) as rather than emphasizing affect and impact, their outcomes have been bound to material contextual changes, such as the repair and maintenance of public spaces.

Beyond these challenges, a number of opportunities were identified. As a surprising result, some participants identified a potentially defensive role for PRs. Here, co-designers 07 and 09 shared experiences of framing their PRs to prevent PSAs’ proposed changes to local community spaces and hubs. Evoking tensions between development and resilience, and communities’ capacities to be responsive, adaptive, and creative in the face of change (Cavaye and Ross, Citation2019), these discussions reinforced a core purpose of PRs to prevent radical transformation taking place without the involvement of the community. However, tempering this, it was also recognized that such PRs can be seen by PSAs to be troublesome and disruptive and, consequently, progress can be stalled amidst the bureaucracy of the process.

The most prominent and compelling opportunity identified by participants related to the potential to position PRs as a means of truly equitable decision-making, as is notionally promised by the CEA itself. Here, participants collectively outlined a hybrid future form of democracy wherein newly formed publics, comprising both community representatives and individual citizens, would be enabled to come together to co-design PR outcomes directly with PSAs (Bennett et al. Citation2022, 18). On this framing, rather than being solely aligned to communities’ right to participate, PRs would be seen to open up pathways toward meeting two critical requirements regarding public participation in policymaking: the requirement to deliver outcomes that respond to peoples’ needs, preferences and values; and the requirement to draw from a more diverse pool of expertise and assets to design those outcomes (Dean Citation2017, 12).

With the above challenges and opportunities, we now turn to framing Social Studios’ outcome.

7. Defining social studios’ outcome

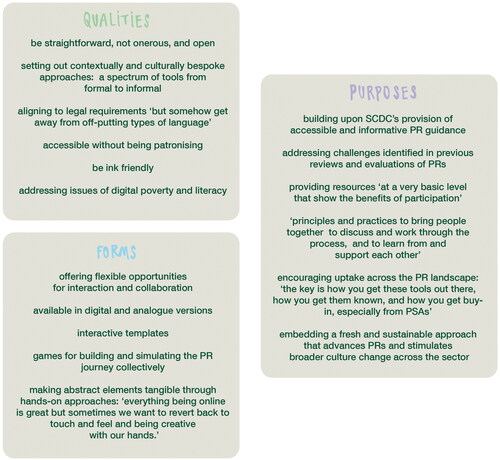

In addition to exploring PR challenges and opportunities, both the interview participants and Social Studio co-designers were prompted in relation to the proposed research outcome, and were encouraged to reflect upon the ways in which a suite of PR tools might be deemed successful (i.e. to identify potential ‘measures’ of success). Both sets of responses were synthesized to form a set of criteria, which guided the co-design, iteration, and evaluation of the eventual PR Toolbox.

As illustrated in the criteria (), the Social Studios participants and co-designers emphasized three overarching areas of concern in relation to the PR Toolbox. These areas of concerns were termed qualities, purposes, and forms. Qualities account for the need to balance the requirements and preferences of a broad spectrum of prospective PR users. Purposes focused on the need to provide multiple flexible routes to engagement by building in accessible and inclusive principles in their design, dissemination, and application. In relation to form, the materiality of the tools was seen to provide an opportunity to enhance the creative capacity of both CPBs and PSAs, as well as to embed community voices directly within individual PRs. It was proposed that this latter aspect might support more effective collaboration between CPBs and PSAs in the longer term.

Figure 3. PR tool evaluation framework: criteria for co-designing effective PR Tools. 2021. Cara Broadley, Harriet Simms, and Social Studios Participants and Co-designers.

In addition to aligning to and strengthening PR evaluations, recommendations, and resources, the purposes of the PR Toolbox were also framed as a set of sustainable principles and practices by which work within and beyond the research project could be guided. These were defined as follows:

to reinforce mutual learning around the benefits of participation;

to support people to come together to engage in equitable decision-making;

and to stimulate broader dialogue and debate surrounding democratic innovation and policymaking contexts in Scotland.

Combined, the above criteria, principles, and practices allowed for the iterative shaping of the PR Toolbox.

8. Developing and consolidating the participation request toolbox

Evoking the challenges and opportunities that are experienced in the PR process as it is currently enacted, the interviews and Social Studios workshops directly informed the co-design of the PR Toolbox. Focusing in on the design aspect in the workshops in Phase 02, the participants used frameworks from within the Companion booklet provided by the researchers (see above) to define opportunities—instances, stages, events, or milestones—in which PRs could be subverted or reframed. This led each group to conceptualize seven broad PR tool ideas as a set of design briefs, which were then developed asynchronously with the support of the research team. Each brief is set out in , through the colored columns. Here, the opportunities (on the top two rows) guide the mapping of design considerations down through the rows.

Figure 4. PR Opportunities, ideas, and design briefs. Each colored vertical column denotes a specific brief, with each opportunity identified being conceptualized as a tool or set of tools with the PR Toolbox. 2021. Cara Broadley, Harriet Simms, and Social Studios Co-designers.

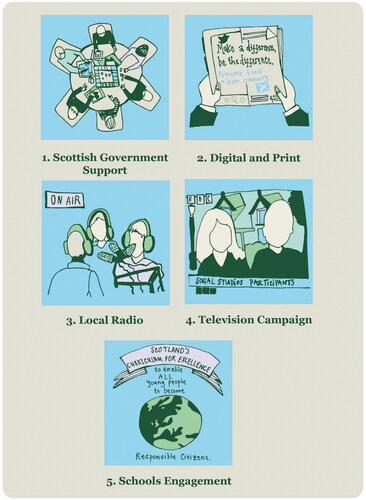

The first complete iteration of the PR Toolbox contained a series of fifteen tools, as well as a proposal to develop a national campaign () to raise public awareness of PRs. Crucially, the campaign would also showcase and signpost the tools that have been co-designed through Social Studios.

Available as online resources (Social Studios Citation2022), the individual tools are downable, allowing for both printing as paper-based templates and digital adaption. Following the recommendations put forward by Glasgow Caledonian University (McMillan, Steiner, and Hill O’Connor Citation2020) and The Scottish Government (Citation2021) in their reviews of PRs, the tools collectively provide a series of actions and approaches to address equality, enhance collaboration, and activate outcomes in the PR process.

In recognizing the varying levels of capacity, time, and external support provided to community groups and striving to create a diverse collection of tools that can be applied flexibly by a broad range of people and organizations, each tool is accompanied by an introduction that outlines its intention, who could use it, what it would help them to achieve, and a recommended timeframe. Tool introductions also include suggestions and prompts for their use and links to other complementary tools.

In Phase 03’s Final Review session the co-designers critiqued the PR Toolbox prototypes () to help shape a reworking of the tools. Responding to the criteria identified for evaluation (), this included reflections on its comprehensive appeal to a potentially broad range of PR users, as well as amends to the text to aid overall accessibility. Such concerns highlight issues raised in previous evaluations of PRs concerning the barriers presented by both poor accessibility and the use of overly complex language in support materials (Paterson Citation2018, 5; McMillan, Steiner, and Hill O’Connor Citation2020, 32).

Figure 6. Social studios toolbox: tool prototypes. 2021. Cara Broadley, Sean Fegan, and Social Studios Co-designers.

A significant and often contentious area of discussion focused on the PR Toolbox’s graphic tone, use of metaphor, and interactive nature. Here, some co-designers consciously sought to diverge from established public sector design norms in order to open PRs up to broader audiences. Conversely, hoping to connote legitimacy, others advocated a professional and managerial look and feel. One area where these disagreements played out was in relation to the inclusion of the PR Journey Tool and its conceptual framing as a board game. The divergent group of co-designers felt strongly about the potential for a game to reorient PR users to a discursive, reflective, and creative space. The others were initially opposed to the gamification of serious decision-making and could not envisage PSAs engaging with it. In the Final Review session however, the PR Journey tool was identified as an outcome which would support communities to simulate, anticipate, and prototype the PR process together, alongside equipping them with strategies to navigate challenges. Such discussions invoke Brandt’s seminal propositions of exploratory design games as frameworks for organizing participation, in which the familiarity and materiality of the artifacts ‘contributes to leveling of stakeholders with different views leading to a more constructive dialogue’ (Brandt Citation2006, 64).

Another area of dissensus in the final review concerned co-designers who were intent on extending the use of PRs through a set of Learning and Sharing tools and those who were skeptical of promoting opportunities for decision-making that are largely ineffective. The latter group held the view that PR reform must work from the inside out to address the failings surrounding power imbalances and limited accountability.

Such concerns underpinned debate around whether the core of the PR problem lies in an overarching lack of public awareness of PRs and their attendant processes; or, if PRs’ fundamental shortcoming resides within the process itself, with the inherent power imbalances between communities and PSAs leading to disconnected aims, outcomes, and measures of success. Whilst aligning to Bennett et al.’s assertion that ‘“getting a seat at the table” might be limited to those capable, with skills and know-how to take advantage of what is frequently perceived as complex legislation’ (2021, 18), the co-designers’ collective rationale in framing the PR Toolbox was that ameliorating issues of external and internal inclusion is a symbiotic endeavor. Thus, with its material resources to promote deliberation and power-sharing, the tools seek to address both the front and back end of PRs in tandem.

In its eventual iterated form, the PR Toolbox can be seen as a spectrum of resources that span the full arc of the PR process. It is firstly intended that the Toolbox will support a group of users’ movement from awareness and access; to understanding the legislation; to developing and submitting the request; to the collaborative development and realization of outcomes; to reflection, evaluation, and resolution. Additionally, through use and further iteration in the longer-term, it is also intended that the Toolbox can contribute to advancing the PR process itself—widening access and, in this, allowing for a reimagining of community participation in policymaking more generally. To enable this, in future work drawing in both SCDC and The Scottish Government, we aim to build on what has been achieved here, extending and expanding the meaning and value of PRs and their potential.

Having discussed Social Studios and its PR Toolbox outcome, we move to close by offering a series of reflections on the role of PD therein.

9. Reflections on the role of participatory design in social studios: New directions and recommendations for improvement

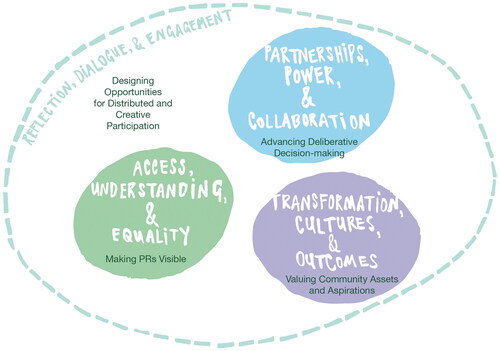

As was noted above, alongside developing the PR Toolbox, Social Studios also aimed to examine the potential of PD in a design for policy context. As a mode of practice and research that seeks to foster creativity, PD principles and practices had a significant impact in shaping the approach taken in the Social Studios’ workshops and in the tenets underpinning the PR Toolbox as a co-designed artifact. The application and affordances of PD throughout both the research process and the development of its outcomes corresponds with the approach’s notional capacity to support decision-making through materiality, mutual learning, and the mobilization of community assets. As highlighted in , Social Studios has led to a series of four reflections and recommendations to strengthen engagement, equality, collaboration, and outcomes in PRs and, as such, design for policy more broadly.

Figure 7. Social studios recommendations: participatory design principles and practices to enhance engagement, equality, collaboration, and outcomes in PRs. 2022. Cara Broadley and Harriet Simms.

9.1. Reflection 1: Participatory design can enable distributed and creative participation

The research recommends that PD principles and practices concerning the use of interactive artifacts be embedded into PRs and broader forms of public engagement, participation, and co-production. These can strengthen the scope and quality of participation by supporting reflection on issues and experiences, focusing dialogue on challenges and opportunities, and enabling diverse people and communities to generate ideas together. PD allows researchers to employ creative and generative methods including collaging, sketching, 3D modeling tasks, prototypes, and design games as ways of telling, making, and enacting to envisage the future (Brandt, Binder, and Sanders Citation2012). The methods developed through Social Studios to support engagement, participation, and collaboration emerged in response to both the underpinning tenets of PD, the research’s objectives to support community representatives in relation to PR, and the circumstances imposed by Covid-19 lockdown restrictions. Whilst Social Studios’ initial intention was to engage with a community group and embark upon a focused inquiry to unpack the intricacies and nuances of their PR experience, lockdown restrictions necessitated that the interactive, situated, and creative elements of material artifacts within the approach be reframed. While enfolding this level of flexibility into PD required significantly more preparation and coordination than in-person sessions, this was deemed essential in developing engagements that responded to the circumstances, capabilities, and preferences of individuals and providing opportunities for enhanced inclusion and impact through their co-design of the PR Toolbox.

9.2. Reflection 2: Participatory design can render PRs visible and so enhance equality of access

The research recommends that visual and participatory tools are used to enhance the communication and promotion of PRs both locally and nationally within Scotland. These can contribute to enhancing access to PR information, improving the understanding of PR procedures and benefits, and addressing equality to enable a broader range of community groups to become involved in PRs. An underpinning feature of Social Studios’ PR Toolbox is that it presents and provides information in a visual format and in turn, invites its users to participate in a series of interactive activities to support their own PR enquiries and needs. Building on principles of asset-based approaches (Garven, McLean, and Pattoni Citation2016) and their parallels with PD’s emphasis on ethical and equitable community participation (Broadley Citation2021; Harrington, Erete, and Piper Citation2019; Costanza-Chock Citation2018), these tools acknowledge the role of formally organized, high-capacity CPBs in increasing access and understanding around PRs, building on their skills, networks, connections, and expertise as central assets, and applying these to enrich capacity-building within local communities from the ground up.

9.3. Reflection 3: Participatory design can advance deliberative decision-making for improved power relations and collaboration

The research recommends that tools for stimulating deliberative decision-making are employed in the OIP and the reporting of PR outcomes. These can inform effective partnership working, recalibrate power relations, and support productive collaboration within and between CPBs and PSAs. Developing participants’ concerns that PRs are viewed primarily as pragmatic opportunities to improve outcomes rather than spaces for relational engagement, the PR tools aim to reinforce the value of deliberation in establishing how distinct perspectives and ambitions can align and cross-pollinate through collaborative processes. Further, the template-based format of the tools aim to materially mediate and facilitate dialogue and deliberation in the OIP, whilst documenting the merging of perspectives and aspirations of the CPB and the PSA—a position that echoes Andersen and Mosleh (Citation2021) discussions of the social dynamics of collaboration and the role of PD artifacts in surfacing tensions and controversies as core features of participation.

It is proposed that such an approach can lead to outcomes that are more effective in balancing diverse needs and preferences, as well as resulting in additional benefits and impacts such as increased feelings and indicators of community empowerment; renewed accountability over action and outcomes on the part of PSAs; trust and reciprocity amongst individuals and groups; and new mindsets, practices, and partnerships to strengthen future initiatives. Beyond these benefits/impacts, it is proposed that the tools may also act as a record of actions undertaken, thus enhancing ownership and accountability within the PR.

9.4. Reflection 4: Participatory design can foreground the value of community assets and aspirations and align these with meaningful outcomes

The research recommends that tools to harness the assets, experiences, and aspirations of people and communities are used across PRs. These can support the transformation of services in local areas, reframe and sustain cultures of participation within PSAs, and inform outcomes of different scales and natures. Across the co-design of the Social Studios PR Toolbox participants emphasized the need to actively address power imbalances and notions of inequality and inequity regarding the practice of participation and the challenges and barriers faced by communities both when finding effective routes into decision-making and when striving to influence and inform outcomes. In response, the PR Toolbox’s interactive format and positioning of CPBs as drivers of action recognizes the innate capability of communities to define pertinent local issues to be addressed, bring forward their own experiences to frame these in context and, further, apply their unique skills and abilities to shape effective outcomes.

This notion correlates to propositions made by Peters, Loke, and Ahmadpour (Citation2021) that analogue tools offer a distinct means of enhancing collaboration ‘because externalizing and organizing insights and concepts within a group is still more fluid, flexible, and tangible’ (Citation2021, 414) than applying their digital counterparts.

While the tools themselves can be critiqued as merely sheets of paper that set out a series of prompts, their value lies in their potential to legitimize deliberation, putting forward a shift in mindset based on their emphasis on engagement through materiality, mutual responsibility, and learning in PRs. Alongside this, additional value is also derived through the mobilization of skills, strengths, and assets from the participating community group, PSA, and surrounding context, which the tools can enable. In this regard, approaches that upskill people, communities, and organizations to advance creative and inclusive policy initiatives can be cited as transferable design research outcomes (Christiansen and Bunt 2014). While Kimbell and Vesnić-Alujević maintain that ‘the expertise, methods, tools and know-how associated with futures and design are not reducible to a “toolkit” for government’ (Kimbell and Vesnić-Alujević Citation2020, 103), they are however capable of impact and transformation in local, regional, and national contexts.

In making this latter claim it is important to acknowledge the need for further piloting and developmental iteration of the PR Toolbox with a broader range of people and communities across Scotland and explore its transferability to enrich PRs as a multi-level participatory and deliberative innovation (Bua and Escobar Citation2018). As a means of considering the form this might take, we will now move to conclude.

10. Conclusion

This article presented findings from the Social Studios research project. This project aimed to examine how PD can support people, communities, and PSAs in the preparation, submission, and implementation of PRs. From this, it also sought to examine the potential of PD in a design for policy context. Alongside outlining the process of developing and defining the PR Toolbox outcome, the article has put forward a series of four reflections and recommendations to strengthen engagement, equality, collaboration, and outcomes in PRs. Positioned in relation to a design for policy context, these stand as principles by which a more politically attuned, equitable approach to design for policy might be engendered.

A number of limitations must be acknowledged here. Firstly, while this research initially aimed to involve PSAs in the Social Studios, all the co-design took place exclusively with CPBs. Secondly and linking to this, in engaging with CPBs who have already undertaken a PR, the research did not directlyinterrogate the barriers experienced by people and communities who have been in some way unable to access the PR process. This is a significant limitation in that many of the challenges identified concern inequalities and inequities and the extent to which marginalized people and communities and less formally organized groups are excluded from PRs. In order to address these limitations, future work must endeavor to draw in PSAs and people/communities who have not been able to access the PR process. Both will undoubtedly have valuable insights to offer for general enhancement of the Toolbox and its attendant processes. It is also acknowledged that while Social Studios sought to establish mutual understanding with research participants, capture in-depth qualitative accounts of the PR experience, and apply these as a basis for co-design, the participant sample in this phase of the research was considerably small. As such, a wider reach must also be sought in future work, thus enhancing the general transferability of any proposals/reflections which arise therein.

Our reflections on the value of PD in a design for policy context pertain in particular to the potential role of tools in a PR process, which of course was a predetermined focus for the project. To extend understanding further, future research might explore how PD approaches could support an open-ended forum for reflection, dialogue, and engagement beyond the PR space. Such work would not only present another opportunity to examine the potential of PD in a design for policy context in Scotland but, importantly, would also contribute to the continued advancement of the design of design for policy itself.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants and co-designers for their contributions to the PR Toolbox; Harriet Simms, Ralph MacKenzie, and Sean Fegan for graphic and web design; and SCDC and The Community Empowerment Team at The Scottish Government for their ongoing support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersen, P. V. K, and W. S. Mosleh. 2021. “Conflicts in Codesign: engaging with Tangible Artefacts in Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration.” CoDesign 17 (4): 473–492. doi:10.1080/15710882.2020.1740279.

- Bailey, J. 2017. Beyond usefulness: Exploring the implications of design in policymaking. Nordes, Oslo.

- Bannon, L., J. Bardzell, and S. Bødker. 2018. “Introduction: Reimagining Participatory Design—Emerging Voices.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 25 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1145/3177794.

- Bason, C. ed., 2016. Design for policy. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bennett, H., O. Escobar, C. Hill O’Connor, E. Plotnikova, and A. Steiner. 2022. “Participation Requests: A Democratic Innovation to Unlock the Door of Public Services?” Administration & Society 54 (4): 605–628. doi:10.1177/00953997211037597.

- Bjerknes, G., P. Ehn, and M. Kyng, eds. 1987. Computers and Democracy—A Scandinavian Challenge. Aldershot: Avebury.

- Blomkamp, E. 2018. “The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy 1.” In Routledge Handbook of Policy Design, edited by M. Hewitt, 59–73. London: Routledge.

- Bradwell, P., and S. Marr. 2008. “Making the Most of Collaboration an International Survey of Public Service co-Design: DEMOS Report 23.” London: DEMOS, Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC) Public Sector Research Centre.

- Brandt, E. 2006. “Designing Exploratory Design Games: A Framework for Participation in Participatory Design?.” In Proceedings of the Ninth Conference on Participatory Design: Expanding Boundaries in Design, 57–66. Trento: PDC.

- Brandt, E., T. Binder, and E. B. N. Sanders. 2012. “Tools and Techniques: ways to Engage Telling, Making and Enacting.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, edited by J. Simonsen and T. Robertson, 145–181. Oxford: Routledge.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Broadley, C. 2021. “Advancing Asset-Based Practice: Engagement, Ownership, and Outcomes in Participatory Design.” The Design Journal 24 (2): 253–275. doi:10.1080/14606925.2020.1857050.

- Broadley, C., and P. Smith. 2018. “Co-Design at a Distance: Context, Participation, and Ownership in Geographically Distributed Design Processes.” The Design Journal 21 (3): 395–415. doi:10.1080/14606925.2018.1445799.

- Bua, A., and O. Escobar. 2018. “Participatory-Deliberative Processes and Public Policy Agendas: lessons for Policy and Practice.” Policy Design and Practice 1 (2): 126–140. doi:10.1080/25741292.2018.1469242.

- Burkett, I. 2012. An Introduction to Co-Design. Sydney: Knode.

- Cavaye, J., and H. Ross. 2019. “Community Resilience and Community Development: What Mutual Opportunities Arise from Interactions between the Two Concepts?” Community Development 50 (2): 181–200. doi:10.1080/15575330.2019.1572634.

- Cairney, P. 2017. “Evidence-Based Best Practice is More Political than It Looks: A Case Study of the “Scottish Approach.” Evidence and Policy 13 (3): 499–515. doi:10.1332/174426416X14609261565901.

- Cairney, P. 2021. “Would Scotland’s Policymaking and Political Structures Change with Independence?” In Scotland’s New Choice: Independence after Brexit, edited by E. Hepburn, M. Keating and N. McEwen, 127–133. Edinburgh: Centre on Constitutional Change.

- Cairney, P., and E. St Denny. 2020. Why Isn’t Government Policy More Preventive? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Christiansen, J., and L. Bunt. 2014. “Innovating Public Policy: Allowing for Social Complexity and Uncertainty in the Design of Public Outcomes.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason, 41–56. Farnham: Gower.

- Costanza-Chock, S. 2018. “Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice.” In Proceedings of the Design Research Society, 529–540. London: The Design Research Society.

- Dean, R. 2017. “Beyond Radicalism and Resignation: The Competing Logics for Public Participation in Policy Decisions.” Policy & Politics 45 (2): 213–230. doi:10.1332/030557316X14531466517034.

- DiSalvo, C., A. Clement, and V. Pipek. 2012. “Communities: Participatory Design for, with and by Communities.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, edited by J. Simonsen, and T. Robertson, 182–209. Oxford: Routledge.

- Dixon, B. 2020. “From Making Things Public to the Design of Creative Democracy: Dewey’s Democratic Vision and Participatory Design.” CoDesign 16 (2): 97–110. doi:10.1080/15710882.2018.1555260.

- Dixon, B., L. S. McHattie, and C. Broadley. 2022. “The Imagination and Public Participation: A Deweyan Perspective on the Potential of Design Innovation and Participatory Design in Policy-Making.” CoDesign 18 (1): 151–163. doi:10.1080/15710882.2021.1979588.

- Elliot, A. 2014. Advice Paper 14-08 Community Empowerment and Capacity Building. Royal Society of Edinburgh: Edinburgh.

- Escobar, O., and S. Elstub. 2017. ‘Deliberative Innovations: Using ‘Mini-publics’ to Improve Participation and Deliberation at the Scottish Parliament’. Submission to the Scottish Commission on Parliamentary Reform (2016-2017). Accessed 24 January 2022. https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/261639/FBD86CBE-0ADA-4094-A701-C95EF94AF2EA.pdf

- Garven, F., J. McLean, and L. Pattoni. 2016. Asset-Based Approaches: Their Rise, Role and Reality. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press Ltd.

- Halse, J., Brandt, E., Clarke, B., and Binder, T., eds. 2010. Rehearsing the Future. Copenhagen: The Danish Design School Press.

- Harrington, C., S. Erete, and A. M. Piper. 2019. “Deconstructing Community-Based Collaborative Design: Towards More Equitable Participatory Design Engagements.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3 (CSCW): 1–25. doi:10.1145/3359318.

- Hill O’Connor, C., and A. Steiner. 2018. Review of Participation Requests Annual Reports: Summary by Glasgow Caledonian University, Accessed 24 January 2022. https://www.gcu.ac.uk/yunuscentre/research/communitycitizenshipandparticipation/evaluationofcommunityempowermentscotlandact/

- Howard, Z., and M. M. Somerville. 2014. “A Comparative Study of Two Design Charrettes: implications for Codesign and Participatory Action Research.” CoDesign 10 (1): 46–62. doi:10.1080/15710882.2014.881883.

- Junginger, S. 2014. “Participatory Government–a Design Perspective.” Paper presented at 19th DMI: Academic Design Management Conference Design Management in an Era of Disruption, 2–4 September 2014, London, UK.

- Kimbell, L., and L. Vesnić-Alujević. 2020. “After the Toolkit: anticipatory Logics and the Future of Government.” Policy Design and Practice 3 (2): 95–108. doi:10.1080/25741292.2020.1763545.

- Kimbell, L., and J. Bailey. 2017. “Prototyping and the New Spirit of Policy-Making.” CoDesign 13 (3): 214–226. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1355003.

- Manzini, E. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. London: MIT press.

- McMillan, C., A. Steiner, and C. Hill O’Connor. 2020. Participation Requests: Evaluation of Part 3 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. Accessed 24 January 2022. https://www.gcu.ac.uk/yunuscentre/research/communitycitizenshipandparticipation/evaluationofcommunityempowermentscotlandact/

- Paterson, A. 2018. One Piece of the Puzzle: A Summary of Learning from SCDC’s Work around Participation Requests. Edinburgh: Scottish Community Development Centre. Accessed 24 January 2022. https://www.scdc.org.uk/what/communityempowerment-scotland-act/participation-requests

- Peters, D., L. Loke, and N. Ahmadpour. 2021. “Toolkits, Cards and Games–a Review of Analogue Tools for Collaborative Ideation.” CoDesign 17 (4): 410–434. doi:10.1080/15710882.2020.1715444.

- Plotnikova, E., and H. Bennett. 2018. Exploring perceived opportunities and challenges of Participation Requests in Scotland. Edinburgh: What Works Scotland. Accessed 24 January 2022. https://whatworksscotland.ac.uk/publications/exploringperceived-opportunities-and-challenges-of-participationrequests-in-scotland/

- Sanders, E. B. N., and J. P. Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/15710880701875068.

- Siodmok, A. 2014. “Tools for Insight: Design Research for Policymaking.” In Design for Policy, edited by C. Bason, 191–100. Farnham: Gower.

- Skerratt, S., and A. Steiner. 2013. “Working with Communitiesof-Place: complexities of Empowerment.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 28 (3): 320–338. doi:10.1177/0269094212474241.

- Social Studios 2022. Social Studios. Accessed 17 June 2022. https://www.socialstudios.org.uk

- Steen, M. 2011. “Tensions in Human-Centred Design.” CoDesign 7 (1): 45–60. doi:10.1080/15710882.2011.563314.

- Tabbner, C. 2018. “Scottish Community Empowerment: Reconfigured Localism or an Opportunity for Change?” Concept 9 (1): 1–11.

- Telier, A., T. Binder, G. De Michelis, P. Ehn, G. Jacucci, P. Linde, and I. Wagner. 2011. () Design Things. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- The Scottish Community Development Centre 2022a. Participation Request Summary Guidance. Accessed 24 January 2022. https://www.scdc.org.uk/news/article/participation-request-summaryguidance

- The Scottish Community Development Centre (SCDC) 2022b. Participation Request Resources. Accessed 24 January 2022. https://www.scdc.org.uk/participation-request-resource

- The Scottish Government 2009. Scottish Community Empowerment Action Plan—Celebrating Success: Inspiring Change. Accessed 24 January 2022. https://dtascommunityownership.org.uk/sites/default/files/Community%20Empowerment%20Action%20Plan.pdf

- The Scottish Government 2015. The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act. Edinburgh: The Scottish Parliament.

- The Scottish Government 2017a. Community Empowerment Act—Easy Read Guidance. Accessed 25 January 2022. https://www.gov.scot/publications/community-empowerment-act-easy-readguidance/

- The Scottish Government 2017b. Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act: Participation Request Guidance. Accessed 24 January 2022. https://www.gov.scot/publications/communityempowerment-participation-request-guidance/

- The Scottish Government 2019. The Scottish Approach to Service Design (SAtSD). Accessed 24 March 2022. https://www.gov.scot/publications/the-scottish-approach-to-service-design/

- The Scottish Government 2021. Community Empowerment: Taking Stock of Participation Requests and Asset Transfers Four Years On. Accessed 24 January 2022. https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/Committees/Report/LGC/2021/2/26/1335d35f-ca3a-4a50-8d86-b4481ea2ba57#bca47a59-9fe5-4fd4-8d1c-2b1eb3771b23.dita

- Vesnic Alujević, L., E. Stoermer, J. Rudkin, F. Scapolo, and L. Kimbell. 2019. The Future of Government 2030+, EUR 29664 EN. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Warren, M. 2009. “Governance-Driven Democratization.” Critical Policy Studies 3 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1080/19460170903158040.

- Whicher, Anna, and Piotr Swiatek. 2022. “Evolution of Policy Labs and Use of Design for Policy in UK Government.” Policy Design and Practice 4:252–270. doi:10.1080/25741292.2022.2141488.