Abstract

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global workforce, including higher-education professionals, experienced substantial changes in their working conditions. Responding to the crisis, universities swiftly adapted their operational modes, thus inevitably impacting the work–life balance (WLB) of their staff. This study examines the WLB factors and their outcomes for higher-education staff, among both teaching and non-teaching staff, in Hong Kong and Thailand, during the initial stages of the pandemic through the lens of the job demands and resources model (JD-R model). The results of 1800 questionnaires completed by respondents from government-funded universities in both locations revealed a significant difference in the WLB between the two cases, with the Hong Kong respondents reporting lower levels of WLB compared with their Thai counterparts. The Hong Kong teaching staff exhibited a higher utilization of family-friendly policies (FFPs), whereas the non-teaching staff reported significantly lower levels of both policy utilization and overall WLB. The results also revealed significant differences in terms of how work, family, and personal-resource and demand factors were correlated to the WLB outcomes. This study advocates for tailored adjustments in university policies, basing the policies on the specific staff category and emphasizing the need for targeted support. In the Hong Kong context, attention should be directed toward enhancing WLB and FFP utilization among non-teaching staff. In contrast, in Thailand, a focus on refining the policies to better support the WLB of teaching staff is recommended.

1. Introduction

Work–life balance (WLB) has become an important issue in the fields of organizational management, human resource management, and public policy. The concept has been broadly defined as the degree to which a person is equally engaged in and satisfied with both the role of work and the role of family in his or her life (Greenhaus, Collins, and Shaw Citation2003). Balancing one’s professional and personal life increases one’s life and work satisfaction while it decreases negative physiological conditions and increases one’s potential to achieve organizational goals (e.g. Johari, Yean Tan, and Tjik Zulkarnain Citation2018; Tamunomiebi and Oyibo Citation2020). However, research shows that work–life imbalance might lead to detrimental outcomes, including family dissatisfaction, poor work performance, and may have negative effects on the individual’s psychological and physical health (Chen et al. Citation2022; Padmanabhan and Srinivasan Citation2016). Thus, WLB can refer to the minimization of conflict or interference between one’s responsibilities at work and those in family/personal roles, and to the facilitation of a positive equilibrium between work life and family/personal life.

A university is a unique organizational setting in which employment status and career advancement are relatively competitive and depend largely on individual performance. In addition, the university world’s ranking system has forced universities around the world to compete (Kehm and Stensaker Citation2019; Li Citation2021). This system requires teaching staff to improve the quality of their teaching and publishing, and non-teaching staff are required to have good university management skills in order to compete. This situation, therefore, can affect the WLB of the entire university staff.

Several WLB studies were conducted in higher-education settings prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly academic staff group. Thorough research had focused on universities in Europe (Krilić, Istenič, and Hočevar Citation2018), the United Kingdom (Fontinha, Van Laar, and Easton Citation2018), the United States (Azevedo et al. Citation2020; Denson, Szelényi, and Bresonis Citation2018), Africa (Jackson and Fransman Citation2018), and Asia (Abd Rahman et al. Citation2017; Badri and Panatik Citation2020). Whereas actual teaching is the primary role of teaching positions in higher education, non-teaching staff work in managerial and service-oriented areas of university administration (Avenali, Daraio, and Wolszczak-Derlacz Citation2023). However, there have been very few comparative studies on WLB that target both teaching and non-teaching staff. Those research works are, for example, the study in the United Kingdom (Johnson, Willis, and Evans Citation2019) and Australia (Winefield, Boyd, and Winefield Citation2014).

To the best of our knowledge, relatively few comparative studies on WLB had been conducted across multiple countries prior to the pandemic, and even fewer during the pandemic. Furthermore, only a few studies have examined WLB for both teaching and non-teaching staff in the higher-education sector, particularly in Asia. Even though both groups work in higher-education institutions, their roles and responsibilities are distinct, and thus they may have experienced different impacts from the pandemic.

This study, therefore, examines the WLB and factors that are associated with it, together with its outcomes among university staff in two cases in Asia: The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (henceforth, Hong Kong), and Thailand. The performance of universities in Hong Kong and Thailand in the world university rankings is remarkably different, which may affect the WLB of their staff as they often reflect the resources and support systems available at these institutions. According to the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2024 (Times Higher Education Citation2024), most public universities in Hong Kong were generally ranked within the top 100 universities worldwide, whereas the rankings of the Thai public universities ranged from 601 to 1500. Besides the differences in their performance, they differ markedly in their cultural orientations, societal norms, and economic structures, which are likely to influence how WLB is perceived and managed. Thailand, with its deep cultural emphasis on familial obligations, social harmony, and relaxed working norms, intersects significantly with cultural norms and expectations regarding WLB. On the other hand, Hong Kong is characterized by its high-pressure work environment, influenced by Chinese culture’s hard-working norms, which may lead to different stressors and coping mechanisms among higher education staff. Comparing these two distinct contexts can illustrate how different cultural and institutional factors influence the WLB of university staff. This comparison not only enriches our understanding of WLB as a multidimensional concept but also assists policymakers and educational leaders in both regions in designing more effective policies tailored to their unique socio-economic contexts.

2. Work–life balance policies in higher education in Hong Kong and Thailand

Work–life balance policies within higher education, often referred to as family-friendly policies (FFPs), encompass initiatives such as flexible work arrangements and family-friendly hours. These policies are strategically designed to enhance staff effectiveness and satisfaction while mitigating the risks inherent in academic work (Saltmarsh and Randell-Moon Citation2015). Their overarching goal is to establish a supportive and adaptable work environment that empowers employees to harmonize their professional obligations with family responsibilities

In Hong Kong, all employees, including university staff, are protected by the Employment Ordinance. The Ordinance sets out regulations regarding flexible work arrangements, living support, and leave entitlements to protect workers’ rights and ensure a family-friendly work environment (Labour Department Citation2024). The Labour Department has encouraged employers to adopt more FFPs to support the WLB of employees (Chou and Cheung Citation2013). Notably, each government-funded university in Hong Kong operates autonomously, governed by its own Ordinance and Governing Council. Consequently, universities have the discretion to offer FFPs tailored to their specific contexts (University Grant Committee Citation2024). While variations exist, common FFPs include flexible work arrangements – such as five-day work weeks, adaptable working hours, and telecommuting – alongside living support provisions encompassing medical coverage, child care services, and lactation facilities within the workplace. Additionally, leave entitlements, including marriage, parental, and filial leave, cater to employees’ diverse needs. Sabbatical and academic leaves are specific for academic staff to support scholarly pursuits.

In line with global trends, Hong Kong’s University Grants Committee (UGC)-funded public universities exhibit proximity to neoliberalism – an ideology emphasizing socioeconomic gains through individual performance and productivity (Gill Citation2014). The UGC’s quality audits, driven by competitive criteria, assess university and staff performance (Singh Citation2020). This emphasis on output and accountability translates into specific requirements for contract renewal; teaching staff must meet performance-based thresholds. Consequently, the Hong Kong higher education sector is marked by extensive workloads, prolonged working hours, heightened performance expectations set by management, and contract instability. These challenges may hinder the effectiveness of WLB initiatives for university staff.

In Thailand, Rules of the Office of the Prime Minister on Leaves of Civil Servants, B.E.2555 outlines various types of leave entitlements for civil servants, including those working in public universities. These regulations ensure that employees have access to necessary leaves for both family and personal reasons. Overview of the types of leaves mentioned is: (1) family-related leaves: maternity leave; paternity leave; leave to follow spouse (which is granted to employees whose spouses are on governmental missions abroad). (2) Personal-related leaves: sick leave; personal leave; vacation leave; ordination or Hajj leave. Academic staff have some specific leaves such as sabbatical leave for academic research or study; short training leaves for professional development, subject to university policy. These leave policies reflect a commitment to supporting the WLB and personal development of civil servants, including those in the academic sector. As some government-funded universities in Thailand are autonomous organizations, each university may have additional policies that further define or extend these leave options for their staff. Besides, welfare policies can vary in respective public universities, but some common benefits include: social security schemes, health care insurance for both staff members and their families, provident funds, and, in some cases, tuition fee support for the children of university staff.

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted the introduction of additional policies and measures to mitigate its impact (Güner, Hasanoğlu, and Aktaş Citation2020). Among these measures, working from home (WFH) emerged as a crucial strategy. It allowed both teaching and non-teaching staff to fulfill their responsibilities remotely. The higher-education sector experienced significant impacts during the pandemic. Classes transitioned to an online mode, forcing teaching staff to adapt to the new pedagogy, which may have required preparing online teaching materials, online assessments, planning for interaction in online classes, and attending more online teaching-related training (Almazova et al. Citation2020; Leal Filho et al. Citation2024). Non-teaching staff participated in providing more support activities and university management while staying away from the office, such as administrative student and teaching staff support, emergency management, and planning for normality (Agasisti and Soncin Citation2021). Although WFH helps people to work anywhere at any time, it also yields negative impacts on the separation of work and life, and thus it can affect workers’ WLB.

3. Theoretical framework and hypotheses

To examine the WLB and its outcomes of the university staff in the two cases during the pandemic, this study employed the job demands and resources model (JD-R model) as a fundamental theoretical framework. The model was developed more than two decades ago, when the publication by Demerouti et al. (Citation2001) based their original model on job demands and resources. That model was then expanded to make it more applicable to crisis situations, which included the demands and resources of both the individual and the family (Bakker, Demerouti, and Sanz-Vergel Citation2023; Demerouti and Bakker Citation2023). As evidenced by Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2007) and Schaufeli (Citation2017), the JD-R theory serves as a predictive framework for crucial workplace outcomes, encompassing employee engagement, organizational performance, and the risk of burnout.

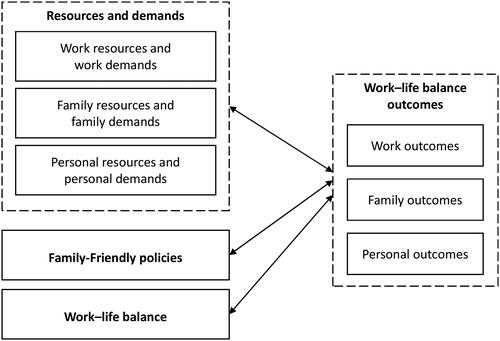

Although the JD-R model offers an appropriate framework for studying WLB, some scholars have argued that the JD-R model is lacking in personal demands/resources (Schaufeli and Taris Citation2014; Xanthopoulou et al. Citation2007). This study, therefore, advanced the model by adding new elements – family demands, family resources, personal demands, and personal resources – in order to recognize the balance in work–life relations. Apart from advancing the JD-R model, this study also considered the effects of FFPs on WLB because FFPs can affect the WLB and the performance of university staff. As a result, this study applied the expanded model to explore a more extensive range of elements related to WLB. The proposed framework elaborates on the pillars of JD-R theory and includes the expanded components of work demands and work resources, family demands and family resources, personal demands and personal resources, and FFPs. The theoretical framework of this study is presented in .

Each key element of the theoretical framework is explained as follows which the definitions of each variable are used to construct the questionnaire for this study.

3.1. Work demands and work resources

Work demands are defined as “the efforts needed (physical and/or psychological) to perform the task given in paid employment excellently” (Jayasingam, Lee, and Mohd Zain Citation2023), whereas work resources include autonomy, decision control, and family-supportive supervisor behavior (Wayne et al. Citation2020).

3.2. Family demands and family resources

According to Boyar et al. (Citation2008), the key variables used to measure family demands are hours spent caregiving, number of children, number of dependents, and being married. Wayne et al. (Citation2020) defined family resources to include both support from family, and family responsibilities, and they can vary in autonomy, skill variety, and task significance.

3.3. Personal demands and personal resources

Personal demands, in this study, encompassed personal health concerns, socialization, personal development, and personal activities/hobbies (Damon Citation2020; Donati and Watts Citation2005). Xanthopoulou et al. (Citation2007) proposed three types of personal resources: self-efficacy, organizational-based self-esteem, and optimism.

3.4. Family-friendly policies

According to Albrecht (Citation2003) and Callan (Citation2007), FFPs refer to organizational strategies that are intended to respond to the concerns of employees with family responsibilities, which include, but are not limited to, welfare that covers family members, leave arrangements, flexible working arrangements, and workplace facilities.

3.5. Work–life balance outcomes

The aforementioned factors are related to the outcomes of WLB. According to Sirgy and Lee (Citation2018), the consequences of WLB or WLB outcomes involve work and nonwork life. Hence, in the present study, three categories represent WLB outcomes that an employee can perceive: work, family, and personal outcomes.

Work outcomes refer to job satisfaction derived from motivation and work performance. Job satisfaction is an emotional response of the employees to their job. This response is the work outcomes led by the WLB. A high WLB employee could be highly satisfied and an excellent performer (French et al. Citation2020). Likewise, a study by Jung, Hwang, and Yoon (Citation2023) found that a good WLB of employees can enhance their job satisfaction and performance, similar to the findings of Aruldoss et al. (Citation2022).

Family outcomes encompass one’s family support system, which increases one’s quality of life, and one’s healthy family relationships. WLB is conducive to marital and family stability, family cohesion, and family happiness (Rao and Indla Citation2010). In addition, Chan et al. (Citation2016) found that WLB has a positive influence on family outcomes. Also, family outcomes, such as family satisfaction can be predicted by WLB (Joseph and Sebastian Citation2019).

Personal outcomes are personal goals in terms of achieving career advancement (Denson, Szelényi, and Bresonis Citation2018). The literature review revealed that most previous studies mainly focused on work outcomes but were very limited in their focus on personal outcomes. Only a few studies have been conducted on WLB outcomes that focus on personal outcomes. For example, Haar et al. (Citation2014) found that balancing employees’ work and life roles could lead to good physical and mental health. Recent study conducted by Leal Filho et al. (Citation2024) shows that faculty members in European universities experienced significant disruptions in their personal domains during the pandemic, marked by increased stress and complexities related to reconciling professional responsibilities with personal obligations. The struggle to reconcile professional and private life has been cited as one of the most harmful consequences of lockdown measures.

This study tested the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: There are significant differences between all staff, teaching staff, and non-teaching staff in the higher-education sector in Hong Kong and their counterparts in Thailand, in terms of resource and demand factors (work resources and demands, family resources and demands, personal resources and demands), family-friendly policies, and work–life balance, and WLB outcomes.

Hypothesis 2: There are significant differences between Hong Kong’s and Thailand’s all staff, teaching staff, and non-teaching staff in the higher-education sector, in terms of the correlations between their resource and demand factors, family-friendly policies, and work–life balance, when comparing WLB outcomes.

4. Methodology

4.1. Case selection

This comparative study employed a quantitative approach by examining the WLB and its outcomes of staff in the higher-education sectors in Hong Kong and in Thailand during the pandemic. Despite Hong Kong and Thailand both having collectivist cultures, the working culture in Thailand is more flexible than the Chinese work-driven lifestyle (Chan and Sheridan Citation2020; Rojanaporn, Niyomsin, and Bangpan Citation2022). University staff in Hong Kong are pushed to work hard due to the influence of neoliberal ideology. As a result, they tend to perform better in World University Rankings compared to their Thai counterparts. However, this intense work culture may impact the staff’s WLB. It should be noted that the researchers have affiliations with institutions in Hong Kong and in Thailand, which provided good access to information. This study is one of the few comparative studies that have compared WLB across higher-education institutions in Asia.

4.2. Sample

Samples of the study were obtained from eight government-funded universities in both cases, resulting in a total of 16 universities. In Thailand, eight universities were selected, with two chosen from each of the four regions. Data were collected from both teaching and non-teaching staff. In this study, teaching staff included professors, lecturers, and other teaching staff, and by non-teaching staff referred to administrative and research staff. Before collecting the data, we obtained ethical approval from the researchers’ institutions, both in Hong Kong and in Thailand. The contact information of the research team and the aims and objectives of this study were provided to the participants, to ensure their consent to participate. All personal information has been kept confidential, privacy has been maintained, and there was no potential risk involved. The respondents were free to withdraw from participation in this study at any time if they felt uncomfortable responding to the questionnaire. All respondents’ personal data were kept confidential.

4.3. Data collection

The data were collected using a questionnaire adapted from Cheung, Wu, and Wong (Citation2013), Hill et al. (Citation2001), Mukhtar (Citation2012), Toderi and Balducci (Citation2015), and Xanthopoulou et al. (Citation2007), and developed based on the theoretical framework. The study administered a questionnaire that comprised 69 questions which covered the following elements: personal information, work resources and work demands, family resources and family demands, personal resources and personal demands, FFPs, WLB, work outcomes, family outcomes, and personal outcomes. A sample of the questionnaire statements is given in Appendix.

The majority of the questions were answered using Likert-scale items, with answers ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”. The remaining items were questions asking for personal information. The same set of questionnaires was administered in both territories; English supplemented with Chinese was used in the Hong Kong questionnaire, and English supplemented with Thai was used in the Thai questionnaire.

Because the study was conducted during the pandemic and most of the university staff were WFH, the data collection in Hong Kong was carried out by a telephone survey between July and November 2020. The population included all of the staff working in eight UGC-funded universities and three vocational colleges in Hong Kong, and individuals were selected by simple random sampling. Their phone numbers were published by the universities’ official websites. In Thailand, an online questionnaire was distributed to university staff via email and social media (LINE and Facebook), as there were no telephone number data available for Thailand universities. The survey in Thailand was conducted between August and December 2020. The total number of respondents in this study was 1800 and comprised 1400 university staff in Hong Kong and 400 university staff in Thailand. The difference in sample size between the two locations was a result of the different survey methods used – the telephone survey was more proactive and therefore received far more responses than the online survey distributed via email and social media did.

4.4. Data analysis

Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test was employed to test Hypothesis 1: whether there were significant differences between university staff in Hong Kong and those in Thailand in terms of resources and demands, FFPs, WLB, and WLB outcome factors. Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test is a classic nonparametric alternative to the two-sample t-test for comparing two independent samples (Westfall and Henning Citation2013). To test Hypothesis 2, Fisher’s z-transformation was utilized to test the significance of the differences between Spearman’s correlation coefficients for the Hong Kong university staff and those for the staff in Thailand, in regard to resource and demand factors, FFPs, WLB, and WLB outcomes. Fisher’s z-transformation aims to stabilize the variance of the sampling distribution of correlation coefficients (Zimmerman, Zumbo, and Williams Citation2003). Spearman’s correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of association between two ranked variables (Schober, Boer, and Schwarte Citation2018).

5. Findings

5.1. Characteristics of the respondents

presents the characteristics of the respondents in the two groups: teaching staff and non-teaching staff. The respondents in both groups had similar characteristics in terms of gender, age, level of education, mode of employment, and position. Whereas most of the Hong Kong participants were married, the majority of the Thai participants were not. Employment status represented another primary difference between the two groups: the Hong Kong staff worked mostly on a contract basis, whereas the Thai university respondents were in tenured/permanent positions. Employment status clearly affected career longevity in both cases – whereas the majority of respondents in both groups exhibited an average work duration of one to five years, nearly half of the Thai respondents had worked for their university for more than 10 years, compared with a mere 25% of the Hong Kong respondents having worked for the same duration. The average numbers of working hours between the two cases were similar, at 40–50 hours per week. Although the maximum number of working hours in both groups was 48, more than 20% of both groups worked more than 50 hours per week. In terms of family variables, the two groups shared some similarities in terms of family structure, often with two household members earning income. In both cases, more than 70% of the respondents had no children under the age of 12 living in the family, nor did they have domestic helpers. Although the majority of families in both groups had no elderly members, 30% of the Thai respondents had two or more elderly people in the family.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of respondents.

5.2. Resource and demand factors and WLB outcome factors

To test Hypothesis 1, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test was employed. As is shown in , the scales for the two groups were internally consistent. Respondents among the university staff – both teaching and non-teaching – in Hong Kong had significantly lower levels of work resources and work demands, family resources and family demands, WLB, work outcomes, family outcomes, and personal outcomes than those in Thailand did. However, there were no statistical differences in their personal resources, personal demands, and FFP variables.

Considering the university teaching staff groups, the Hong Kong respondents had significantly lower levels of family resources, family demands, work outcomes, and family outcomes, but higher levels of FFPs, compared with their Thai counterparts.

Table 2. Statistics for resource and demand factors and WLB outcome factors.

Regarding the non-teaching staff, the results show that, compared with respondents in Thailand, respondents in Hong Kong had significantly lower levels in almost all variables, except for the personal resources and personal demands variables, which were not statistically different.

Hypothesis 2 was tested using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient analysis. The correlations between resource and demand factors and WLB outcome factors are presented in . In both of the locations, the work resources and work demands variable had relatively high positive correlations with the work outcomes (Hong Kong 0.632, Thailand 0.716). Likewise, and in both locations, the family resources and family demands variable had moderate positive correlations with the family outcomes (Hong Kong 0.475, Thailand 0.579). The personal resources and personal demands variable had a moderate positive correlation with the personal outcomes in the Hong Kong case (0.455), whereas in the Thailand case, we found a high positive correlation (0.645). The FFPs aspect was found to have moderate positive correlations with the work outcomes and the personal outcomes in Hong Kong (0.441 and 0.408, respectively), whereas FFPs had a relatively high positive correlation with the personal outcomes in Thailand (0.603). The WLB variable was found to have a moderate positive correlation with the work outcomes and the personal outcomes in Hong Kong (0.531 and 0.439, respectively), whereas it was found to have a relatively high positive correlation with these two outcomes in Thailand (0.675 and 0.670, respectively).

Table 3. Spearman’s correlation coefficients regarding resource and demand factors and WLB outcome factors.

Relying on Fisher’s z-transformation, as is shown in , we tested the significance of the differences between Spearman’s correlation coefficients for the two samples. In most cases, the correlations for the Hong Kong sample were significantly lower than those for the Thailand sample, with the exceptions of the correlation between FFPs and family outcomes and the correlation between family resources and demands and personal outcomes.

Table 4. Comparison of the correlations between resource and demand factors and WLB outcome factors for Hong Kong and Thailand university staff (fisher z-transformation).

Of the correlations found for the teaching staff group, the correlations between the resources and demands factors and personal outcomes for the Hong Kong sample were significantly lower than those for the Thailand sample in almost all factors, with the exceptions of the family resources and family demands, which were higher, as shown in and . However, most of the correlations between work outcomes and family outcomes were not significantly different between the two groups, with the exception that the Hong Kong sample’s correlation between WLB and work outcomes was lower than that found in the Thailand sample.

For the non-teaching staff, the Hong Kong sample had lower correlations between various factors than the Thailand sample did: FFPs, WLB, and work outcomes; work resources and demands, family resources and family demands, personal resources and demands, and family outcomes; personal resources and demands; and personal resources and demands, FFPs, and personal outcomes.

Overall, then, regardless of whether the respondents were university teaching staff or non-teaching staff, the associations between resource and demand factors and WLB outcome factors were weaker in the Hong Kong group than in the Thailand group, which indicates that resources and demands may have a larger effect on corresponding outcomes in Thai universities.

6. Discussion

This study compared the WLB and factors relating to it, together with analyzing the correlations with the WLB outcomes among teaching and non-teaching staff in the higher-education sector in Hong Kong and Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic. This comparative study distinguished between three groups: the university staff as a whole in the higher-education sector, the teaching staff, and the non-teaching staff, in Hong Kong and in Thailand. The objective was to gain insights into the factors relating to the WLB of each respective group in each location, and thus to inform the customization of policies intended to enhance the WLB for each specific category.

6.1. Staff in the higher-education sector

Overall, the results show that the Hong Kong respondents had significantly lower work and family resources and demands and a lower level of WLB than did those in Thailand. Regarding work resources and demands, employment status played an important role in distinguishing between the two territories; the respondents from Hong Kong were mainly employed on a contract basis, whereas those in Thailand were mainly in tenured/permanent positions. Therefore, employment status was found to be related to work resources and demands and WLB. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies, which confirmed that low work resources and demands contribute to a low quality of work and life (Mudrak et al. Citation2018). Due to their contracts, staff in the higher-education sector in Hong Kong have irregular working hours, high expectations and strong competition, and a trend of internationalization; thus, contract workers have to labor actively to accomplish their goals and secure their jobs at the same time (Annink, den Dulk, and Steijn Citation2016). However, when a permanent contract is guaranteed, workers are able to experience income security and greatly benefit from work resources (Krumbiegel, Maertens, and Wollni Citation2018).

Moreover, this study’s results revealed that the university staff in Hong Kong worked longer hours than those in Thailand did – nearly 80% of the respondents in Hong Kong spent at least 40 hours or more per week working, whereas approximately 77% of the respondents in Thailand spent between 30 and 50 hours working per week. On this subject, our study was also consistent with research by the Federation of Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, which had found that Hong Kong employees worked an average of 44 hours per week (The Standard Citation2022), and with research by the Swiss Bank UBS, which indicated that Hong Kong workers had the most prolonged working hours in the world (April International Citation2023). Working from home may encourage employees in Hong Kong to work longer hours compared to being in the office due to the culture of hard work and the lack of clear separation between work and personal life. Many studies (e.g. Chen et al. Citation2022; Fontinha, Easton, and Van Laar Citation2019) have revealed that overtime work hours are associated with an increase in work–family imbalance because time spent on work interferes with family life. Indeed, those findings also align with our result concerning the longer working hours affecting the lower level of WLB in Hong Kong. Overall, the staff in the higher-education sector in Hong Kong experienced lower levels in all of the WLB outcomes – the work, family, and personal aspects. Our results regarding Hong Kong staff in the higher-education sector indicated that they had a lower level of demands and resources and a low level of WLB; thus, the WLB outcomes in Hong Kong were lower than those in Thailand.

In terms of family resources and demands, the family’s characteristics can have an impact. Particularly during the pandemic, the staff in the higher-education sectors in both Hong Kong and Thailand were forced to embrace the work-from-home arrangements, along with other sectors. This study found that most of the respondents in both cases did not have domestic helpers; however, respondents in Thailand had relatively more immediate family members living with them, resulting in more family resources, than was the case with the respondents in Hong Kong. Significantly, while WFH during the pandemic, people in Thailand tended to have more immediate family members available who could help with caregiving for children or older people, and with other household responsibilities. In contrast, those in Hong Kong most often lived in nuclear families, in which the parents may have needed to take care of their children, their household responsibilities, their chores, and their work duties by themselves, while also WFH during the pandemic. This would undoubtedly have made it challenging for the Hong Kong workforce to attain a high level of WLB (Vyas and Butakhieo Citation2020). Therefore, this study’s findings illustrate that the extended family system in Thailand enriches family resources and enables university staff to experience better WLB. In this regard, too, this study is congruent with previous research, which found that support from family can generate positive effects and enhance workers’ contentment with their WLB (Landolfi et al. Citation2021; Wayne et al. Citation2020).

Regarding FFPs, this study found that FFPs had only moderate positive correlations with family outcomes in both locations, which may imply that the universities’ FFPs, in both cases, largely do not yet help the staff achieve the desired family outcomes. One reason that the utilization of FFPs is low is the staffs’ “fear of being labeled” if they utilize any available FFPs, and the influence of organizational culture and supervisor and peer support (Vyas, Cheung, and Chou Citation2024; Vyas, Lee, and Chou Citation2017).

As more than half of the study’s respondents were women, which is a limitation of the study, the result tended to reflect the needs of female staff. In Asian contexts such as those of Hong Kong and Thailand, families, societies, and governments expect women, more than men, to perform nurturing duties or engage in unpaid care work for their family members. According to Chandra (Citation2012), in Asian countries, WLB is seen as an issue for women more than for men, while in Western countries it is often seen as an issue common to both men and women. Owing to these cultural and gender factors, using FFPs to improve WLB would need to be specific for female staff.

In the case of Thailand, the majority of the Thai respondents have never married; thus, their family and personal resources and demands are different from those who are married and those who have children. Consequently, universities in Thailand should focus more on providing policies that support the needs of unmarried staff. Moreover, more than 70% of the respondents had no children under the age of 12 living in the family, and 30% of the respondents had two or more elderly people in the family. The data reflect the characteristics of an aging society in Thailand, wherein the elderly are the dependents in the family, not young children. Therefore, FFPs that support an aging society should be encouraged in Thai universities.

Theoretically, FFPs are addressed in labor laws to support employees in achieving WLB. However, in practice, there is a wide range of limitations – for instance, more support from employers and supervisors, more governmental legislative intervention, and more leave policies in organizations are needed (Kaewthaworn Citation2019; Vyas, Lee, and Chou Citation2017). Therefore, the current situation makes it challenging to practice FFPs, and that was especially the situation during the early stages of the pandemic when employees were forced to work from home and their work interfered with their work–life boundaries (Iwu et al. Citation2022).

6.2. Teaching staff

In terms of the teaching staff in particular, the study’s results revealed that the Hong Kong respondents had significantly less secured employment status than the Thai counterparts owing to the tenure track system. Together with lower family resources and demands, the Hong Kong teaching staff experienced challenging WLB. Regardless of whether they were employed on a tenure or non-tenure basis, the staff members in both cases similarly worked within the competitive university ranking system. Their promotion and contract renewal indicators were based primarily on their research output and publications to meet the requirements for international competitiveness in global university rankings (Chou Citation2021; Li Citation2021). This turned the academic staff into paper producers (Chou Citation2021) and ultimately affected the WLB of them. It was evident in a study by Fontinha, Van Laar, and Easton (Citation2018) that academics who work in lower-ranked universities have less stress at work and less pressure from the need for publications, compared with their counterparts working in higher-ranked universities. Because most universities in Hong Kong rank higher than those in Thailand (e.g. Times Higher Education and QS World University Rankings), results from this study show that the Hong Kong respondents had a lower WLB than those in Thailand. This could have resulted from greater pressure to publish in the Hong Kong universities, which in turn led to long working hours, lower levels of WLB, and poorer family and personal outcomes.

As mentioned earlier, the characteristics of the family and the long work hours could have had an impact on WLB outcomes. Thus, the Hong Kong respondents may have perceived less support from their families, since most of the respondents lived alone or in a nuclear family – situations that tend to cause lower work and family outcomes. However, the teaching staff in Hong Kong in this study had a significantly higher level of FFPs than those in Thailand, which implies that the Hong Kong universities have provided FFPs that match the teaching staff members’ needs, and that the utilization of FFPs is the norm in Hong Kong.

Although universities in Thailand have similar FFPs, such as parental leave and flexible work arrangements, the utilization of FFPs are lower there. One of the reasons is that Thai teaching staff have a larger teaching load: the minimum number of working hours is 35 hours per week (on a five-day basis), and some universities require teaching staff to teach at least 25 hours per week. In addition to this, some universities have extra courses which do not count toward the regular teaching workload, and which are held in the evenings and weekends, and thus require teaching staff to work extra hours. Teaching responsibilities are difficult to assign to others and thus prevent teaching staff from utilizing FFPs, such as taking leave. A sabbatical leave policy has been introduced in most universities in Thailand to support the teaching staff in enhancing their research knowledge and skills; however, teaching responsibilities might not encourage workers to apply for such leave as their teaching load will be assigned to other staff. As was discussed above, the main reason for the low uptake of such a policy could be the fear of being labeled self-centered. Online teaching during the pandemic enhanced flexibility of work for teaching staff and can help encouraging the use of FFPs as teaching can be done online anywhere at any time. Thus, the Thai universities should consider reducing teaching load for teaching staff, allow online teaching in certain circumstances, and promote the use of FFPs to become the norm in organizations.

6.3. Non-teaching staff

In the context of non-teaching staff, the Hong Kong respondents had significantly lower levels of work and family resources and demands, FFPs, WLB, and WLB than their counterparts in Thailand did. As was mentioned previously, the FFPs in Hong Kong could be a privilege afforded to professions with higher educational levels (Vyas, Lee, and Chou Citation2017), but leaving non-teaching staff excluded from some policies because of their educational level or work position. In line with the Indeed Editorial Team’s study (Indeed Editorial Team Citation2023), individuals in a nonprofessional career with little training or education are likely to be concerned about job security, job conditions, and work relationships, and such concerns in turn create stressors and a work–life imbalance (Johnson, Willis, and Evans Citation2019). Lack of job security can put more stress on the Hong Kong non-teaching respondents than the Thais as the majority of respondents in Hong Kong are employed on a contract basis, whereas the majority of respondents from Thailand have permanent employment status. These concerns might have been accelerated, especially during the pandemic (Rajabimajd, Alimoradi, and Griffiths Citation2021).

The nature of the administrative work of non-teaching staff requires fixed-working hours, meaning their jobs have less flexibility than the teaching staff’s. Moreover, given that the Hong Kong respondents have fewer family resources than those in Thailand, more pressure is put on the Hong Kong non-teaching staff to manage family and personal demands. Besides this, non-teaching staff in Hong Kong experienced lower benefits from the FFPs than did the Thai non-teaching staff. In terms of the Thai non-teaching staff, higher levels of family resources and FFPs may help them to achieve better WLB. A study by Phetpankan and Thabhiranrak (Citation2018) found that non-teaching staff at one university in Thailand had a good quality of working life, and had acquired appropriate compensation, and accordingly had a good workplace environment and a favorable WLB. Therefore, the Hong Kong universities should be focused on providing job security, facilitating flexible working hours, encouraging the WFH practice, and providing a wider range of FFPs for non-teaching administrative staff such as medical assistance for family members of staff, longer periods of leave for family and personal reasons.

7. Policy recommendations

Based on the findings discussed above, some policies should be designed specifically to enhance the WLB among university staff in both cases, not only in time of the pandemic but also in non-pandemic situation. In Hong Kong, the results show that all respondents had low work and family resources and demands and perceived their WLB to be low across all aspects of their work, family, and personal outcomes. The Hong Kong teaching staff also perceived themselves as having less support from their families than those in Thailand did, while the non-teaching staff in Hong Kong experienced lower benefits from the FFPs than did the Thai non-teaching staff. Thus, two policy recommendations are proposed for Hong Kong.

First, to address the issue of low work resources and demands, Hong Kong universities should support additional tenured positions, with the intention of increasing job security, so that the staff can feel a sense of belonging and be more engaged with their work (Krumbiegel, Maertens, and Wollni Citation2018). Supporting systems such as mentoring or supervision for career advancement should be emphasized for teaching staff. Regarding non-teaching staff, long term contacts and flexible working hours can enhance the work resource and therefore enhance WLB and WLB outcomes. Long work hours in most Hong Kong workplaces, including higher-education institutions, do not necessarily equate to productive hours and should not be encouraged. In particular, both contract and temporary staff should have a maximum number of work hours stipulated. Furthermore, because their jobs are not permanent, they are likely to choose to work excessive hours or are made to do so to secure their position. Flexible work arrangements for all, including teaching, administrative, and research staff, should be encouraged, in an effort to allow the entire staff more autonomy and encourage job commitment (Aik Citation2022). Flexible job arrangements will allow the workers to spend more time with their families (Peek, Im-em, and Tangthanaseth Citation2016) and can thus result in better family outcomes.

Second, to increase family resources, because the majority of Hong Kong’s families are characterized as nuclear, family support policies should be addressed, particularly for the non-teaching group. For example, increasing the number and flexibility of family leave policies are essential steps. It is also vital that university staff perceive the effectiveness of FFPs and that universities encourage them to enjoy the policies’ benefits (Vyas, Lee, and Chou Citation2017). Even though the teaching staff in Hong Kong seemed to utilize the FFPs, the FFPs they took advantage of were usually those mandated by the government, such as the five-day work week, the teaching staff seldom utilized other policies because they feared being stigmatized. In that light, the university administration should proactively encourage and train supervisors to support their supervisees in freely making use of the available policies.

In the context of Thailand, two key policy recommendations are suggested. First, considering Thailand has an aging society wherein elderly people are more likely to be the dependents in the family rather than young children, Thai universities should adjust their FFPs to be more focused on supporting the elderly in the family, such as providing medical care that covers family members, and providing leave when family members become sick or die. The utilization of FFPs should also be made easier by simplifying the bureaucratic process, as the current system requires staff to navigate many levels of authorization. Reducing teaching workload for teaching staff and introducing flexible work arrangements, such as hybrid working, online classrooms, online meetings, or online consultations, will allow staff to work virtually outside the university and increase their personal time (Eaton and Heckscher Citation2021), and permit them to spend time with their families (Peek, Im-em, and Tangthanaseth Citation2016).

Second, because the results suggest that the Thailand respondents acquired sufficient family support from their extended families, the FFPs in Thailand should focus on enriching family aspects. This could include engaging family members in organization activities, and extending welfare to family members to demonstrate the organization’s support of the family. Considering the results showed that the majority of the Thai respondents are single, personal preoccupations of single people should be considered, such as personal health concerns, financial security, socialization, personal development, and personal activities/hobbies. According to Jain (Citation2022), personal demand factors influence one’s perception of WLB. Thus, Thai universities can improve the WLB of their staff by focusing on personal resources and demands.

8. Conclusions

This study compared data from university staff in higher-education institutions in Hong Kong and in Thailand, investigating WLB factors and outcomes among teaching and non-teaching staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study’s primary focus was on exploring the relationships between work and life spheres among higher-education staff in both regions, and that was guided by two primary hypotheses.

In general, the study’s respondents from Hong Kong exhibited significantly lower levels of work and family resources and demands their counterparts in Thailand had, and that resulted in them having an overall lower level of WLB. This discrepancy may be attributed to variations in employment statuses, family characteristics, and prolonged working hours. However, when specifically examined the teaching staff, the Hong Kong respondents demonstrated lower work and family outcomes, but notably higher utilization of FFPs than their Thai counterparts did. In contrast, the comparative analysis of non-teaching staff indicated that Hong Kong respondents exhibited considerably lower levels of WLB and FFP utilization, and of overall WLB outcomes, than their counterparts in Thailand did – implying that the current FFPs in Hong Kong may not effectively support higher education staff in balancing their work and life domains.

In addition, when comparing correlations among the variables, the study revealed that the correlations between the work resources and work demands variable and work outcomes, and correlations between the family resources and family demands variable and family outcomes, were similar in both the Hong Kong and Thailand cases. Hong Kong was found to have positive moderate correlations between the personal resources and demands variable and personal outcomes, as well as between FFPs and work and personal outcomes, while relatively high positive correlations were found in the Thailand case. However, FFPs had moderate positive correlations with family outcomes in both cases.

The findings of this study contribute to informing both policy design and practices to improve the WLB of staff in the higher-education sector in Asia. The key recommendation is to tailor policies according to the diverse needs of the various types of staff. Despite the unconventional circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic during the study, the insights garnered remain valuable for policymakers in higher education. The findings demonstrate the importance of prioritizing WLB initiatives, not only to enhance the overall quality of life for staff, but also to improve work performance within the sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abd Rahman, Nor Sa’adah, Salmiah Mohamad Amin, Normahaza Mahadi, and Fadillah Ismail. 2017. “The Relationship between Work–Family Balance and Affective Organizational Commitment among Academic Staff of Malaysian Research Universities.” Advanced Science Letters 23 (1): 482–485. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2017.7229.

- Agasisti, Tommaso, and Mara Soncin. 2021. “Higher Education in Troubled Times: On the Impact of Covid-19 in Italy.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (1): 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1859689.

- Aik, Nelson Teh Song. 2022. “Assessing the Impact of Friendly Family Practice in Reducing Employee Turnover in Malaysian Private Higher Educational Institutions.” Business Ethics and Leadership 6 (4): 10–22. https://doi.org/10.21272/bel.6(4).10-22.2022.

- Albrecht, Gloria H. 2003. “How Friendly Are Family Friendly Policies?” Business Ethics Quarterly 13 (2): 177–192. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq200313213.

- Almazova, Nadezhda, Elena Krylova, Anna Rubtsova, and Maria Odinokaya. 2020. “Challenges and Opportunities for Russian Higher Education amid COVID-19: Teachers’ Perspective.” Education Sciences 10 (12): 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120368.

- Annink, Anne, Laura den Dulk, and Bram Steijn. 2016. “Work–Family Conflict among Employees and the Self-Employed across Europe.” Social Indicators Research 126 (2): 571–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0899-4.

- April International. 2023. “Long Working Hours in Hong Kong: What is the Impact on Your Health?” Accessed March 12, 2023. https://www.april-international.com/en/long-term-international-health-insurance/guide/long-working-hours-hong-kong-what-impact-your-health.

- Aruldoss, Alex, Kellyann Berube Kowalski, Miranda Lakshmi Travis, and Satyanarayana Parayitam. 2022. “The Relationship between Work–Life Balance and Job Satisfaction: Moderating Role of Training and Development and Work Environment.” Journal of Advances in Management Research 19 (2): 240–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-01-2021-0002.

- Avenali, Alessandro, Cinzia Daraio, and Joanna Wolszczak-Derlacz. 2023. “Determinants of the Incidence of Non-Academic Staff in European and US HEIs.” Higher Education 85 (1): 55–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00819-7.

- Azevedo, Lauren, Wanzhu Shi, Pamela S. Medina, and Matt T. Bagwell. 2020. “Examining Junior Faculty Work–Life Balance in Public Affairs Programs in the United States.” Journal of Public Affairs Education 26 (4): 416–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2020.1788372.

- Badri, Siti Khadijah Zainal, and Siti Aisyah Panatik. 2020. “The Roles of Job Autonomy and Self-Efficacy to Improve Academics’ Work–Life Balance.” Asian Academy of Management Journal 25 (2): 85–108. https://doi.org/10.21315/aamj2020.25.2.4.

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. “The Job Demands–Resources Model: State of the Art.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 22 (3): 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115.

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, and Ana Sanz-Vergel. 2023. “Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 10 (1): 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933.

- Boyar, Scott L., Carl P. Maertz, Donald C. Mosley, and Jon C. Carr. 2008. “The Impact of Work/Family Demand on Work–Family Conflict.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 23 (3): 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810861356.

- Callan, Samantha. 2007. “Implications of Family-Friendly Policies for Organizational Culture: Findings from Two Case Studies.” Work, Employment and Society 21 (4): 673–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017007082876.

- Chan, Heng Choon, and Lorraine Sheridan. 2020. “Is This Stalking? Perceptions of Stalking Behavior among Young Male and Female Adults in Hong Kong and Mainland China.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 35 (19–20): 3710–3734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517711180.

- Chan, Xi Wen., Thomas Kalliath, Paula Brough, Oi-Ling Siu, Michael P. O’Driscoll, and Carolyn Timms. 2016. “Work–Family Enrichment and Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Work–Life Balance.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27 (15): 1755–1776. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1075574.

- Chandra, V. 2012. “Work–Life Balance: Eastern and Western Perspectives.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 23 (5): 1040–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.651339.

- Chen, Qiqi, Mengtong Chen, Camilla Kin Ming Lo, Ko Ling Chan, and Patrick Ip. 2022. “Stress in Balancing Work and Family among Working Parents in Hong Kong.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (9): 5589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095589.

- Cheung, Millissa FY, Wei-Ping Wu, and Mei-Ling Wong. 2013. “Supervisor–subordinate Kankei, Job Satisfaction and Work Outcomes in Japanese Firms.” International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 13 (3): 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595813501477.

- Chou, Chuing Prudence. 2021. “The SSCI Syndrome in Taiwan’s Academia.” In Measuring Up in Higher Education: How University Rankings and League Tables Are Re-Shaping Knowledge Production in the Global Era, edited by Anthony Welch and Jun Li, 153–173. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Chou, Kee Lee, and Kelvin Chi Kin Cheung. 2013. “Family-Friendly Policies in the Workplace and Their Effect on Work–Life Conflicts in Hong Kong.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 24 (20): 3872–3885. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.781529.

- Damon, William. 2020. “Socialization and Individuation.” In Childhood Socialization, edited by G. Handel, 3–10. London: Routledge.

- Demerouti, Evangelia, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2023. “Job Demands–Resources Theory in Times of Crises: New Propositions.” Organizational Psychology Review 13 (3): 209–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/20413866221135022.

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. “The Job Demands–Resources Model of Burnout.” Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (3): 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499.

- Denson, Nida, Katalin Szelényi, and Kate Bresonis. 2018. “Correlates of Work–Life Balance for Faculty across Racial/Ethnic Groups.” Research in Higher Education 59 (2): 226–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9464-0.

- Donati, Mark, and Mary Watts. 2005. “Personal Development in Counsellor Training: Towards a Clarification of Inter-Related Concepts.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 33 (4): 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880500327553.

- Eaton, Adrienne, and Charles Heckscher. 2021. “COVID’s Impacts on the Field of Labour and Employment Relations.” Journal of Management Studies 58 (1): 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12645.

- Fontinha, Rita, Darren Van Laar, and Simon Easton. 2018. “Quality of Working Life of Academics and Researchers in the UK: The Roles of Contract Type, Tenure and University Ranking.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (4): 786–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1203890.

- Fontinha, Rita, Simon Easton, and Darren Van Laar. 2019. “Overtime and Quality of Working Life in Academics and Nonacademics: The Role of Perceived Work–Life Balance.” International Journal of Stress Management 26 (2): 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000067.

- French, Kimberly A., Tammy D. Allen, Michelle Hughes Miller, Eun Sook Kim, and Grisselle Centeno. 2020. “Faculty Time Allocation in Relation to Work–Family Balance, Job Satisfaction, Commitment, and Turnover Intentions.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 120: 103443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103443.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2014. “Academics, Cultural Workers and Critical Labour Studies.” Journal of Cultural Economy 7 (1): 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2013.861763.

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey, Karen M. Collins, and Jason D. Shaw. 2003. “The Relation between Work–Family Balance and Quality of Life.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 63 (3): 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00042-8.

- Güner, Hatice Rahmet, İmran Hasanoğlu, and Firdevs Aktaş. 2020. “COVID-19: Prevention and Control Measures in Community.” Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences 50 (SI-1): 571–577. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-2004-146.

- Haar, Jarrod M., Marcello Russo, Albert Suñe, and Ariane Ollier-Malaterre. 2014. “Outcomes of Work–Life Balance on Job Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction and Mental Health: A Study across Seven Cultures.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 85 (3): 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.010.

- Hill, E. Jeffrey, Alan J. Hawkins, Maria Ferris, and Michelle Weitzman. 2001. “Finding an Extra Day a Week: The Positive Influence of Perceived Job Flexibility on Work and Family Life Balance.” Family Relations 50 (1): 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00049.x

- Indeed Editorial Team. 2023. “Nonprofessional vs. Professional Jobs: What’s the Difference?” Accessed April, 2023. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/finding-a-job/nonprofessional-vs-professional-jobs#:∼:text=Because%20professional%20jobs%20generally%20require,experience%20level%20and%20their%20career.

- Iwu, Chux Gervase, Obianuju E. Okeke-Uzodike, Emem Anwana, Charmaine Helena Iwu, and Emmanuel Ekale Esambe. 2022. “Experiences of Academics Working from Home during COVID-19: A Qualitative View from Selected South African Universities.” Challenges 13 (1): 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13010016.

- Jackson, Leon T. B., and Edwina I. Fransman. 2018. “Flexi Work, Financial Well-Being, Work–Life Balance and Their Effects on Subjective Experiences of Productivity and Job Satisfaction of Females in an Institution of Higher Learning.” South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 21 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v21i1.1487.

- Jain, Bandana Kumari. 2022. “Work–Life Balance of Bank Employees during the Pandemic: An Exploratory Analysis.” Tribhuvan University Journal 37 (2): 31–47. https://doi.org/10.3126/tuj.v37i02.51631.

- Jayasingam, Sharmila, Su Teng Lee, and Khairuddin Naim Mohd Zain. 2023. “Demystifying the Life Domain in Work–Life Balance: A Malaysian Perspective.” Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.) 42 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01403-5.

- Johari, Johanim, Fee Yean Tan, and Zati Iwani Tjik Zulkarnain. 2018. “Autonomy, Workload, Work–Life Balance and Job Performance among Teachers.” International Journal of Educational Management 32 (1): 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-10-2016-0226.

- Johnson, Sheena J., Sara M. Willis, and Jack Evans. 2019. “An Examination of Stressors, Strain, and Resilience in Academic and Non-Academic U.K. University Job Roles.” International Journal of Stress Management 26 (2): 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000096.

- Joseph, Joshin, and Deepu Jose Sebastian. 2019. “Work–Life Balance vs Work–Family Balance-an Evaluation of Scope.” Amity Global HRM Review 9: 54–65. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.36194.38084.

- Jung, Hyo-Sun, Yu-Hyun Hwang, and Hye-Hyun Yoon. 2023. “Impact of Hotel Employees’ Psychological Well-Being on Job Satisfaction and Pro-Social Service Behavior: Moderating Effect of Work–Life Balance.” Sustainability 15 (15): 11687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511687.

- Kaewthaworn, Apisara. 2019. The Influence of Family-Friendly Policies on Employee Engagement: A Case Study of the Hotel Industry in Hatyai District, Songkhla Province and Kathu District, Phuket Province. Hat Yai, Thailand: Prince of Songkla University.

- Kehm, Barbara M., and Bjørn Stensaker. 2019. “Introduction.” In University Rankings, Diversity, and the New Landscape of Higher Education, edited by Jane Knight, i–xix. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Krilić, Sanja Cukut, Majda Černič Istenič, and Duška Knežević Hočevar. 2018. “Work–Life Balance among Early Career Researchers in Six European Countries.” Gender and Precarious Research Careers 145: 145–177. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315201245-6.

- Krumbiegel, Katharina, Miet Maertens, and Meike Wollni. 2018. “The Role of Fairtrade Certification for Wages and Job Satisfaction of Plantation Workers.” World Development 102: 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.09.020.

- Labour Department. 2024. “Employment Ordinance.” Accessed May 25, 2024. https://www.labour.gov.hk/eng/legislat/content.htm.

- Landolfi, Alfonso, Massimiliano Barattucci, Assunta De Rosa, and Alessandro Lo Presti. 2021. “The Association of Job and Family Resources and Demands with Life Satisfaction through Work–Family Balance: A Longitudinal Study among Italian Schoolteachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Behavioral Sciences 11 (10): 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11100136.

- Leal Filho, Walter, Tony Wall, Amanda Lange Salvia, Claudio Ruy Vasconcelos, Ismaila Rimi Abubakar, Aprajita Minhas, Mark Mifsud, et al. 2024. “The Impacts of the COVID-19 Lockdowns on the Work of Academic Staff at Higher Education Institutions: An International Assessment.” Environment, Development and Sustainability https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-04484-x.

- Li, Jun. 2021. “The Global Ranking Regime and the Redefined Mission of Higher Education in the Post-Covid Era: An Introduction.” In Measuring up in Higher Education: How University Rankings and League Tables Are Re-Shaping Knowledge Production in the Global Era, edited by Anthony Welch and Jun Li, 3–18. Singapore: Springer.

- Mudrak, Jiri, Katerina Zabrodska, Petr Kveton, Martin Jelinek, Marek Blatny, Iva Solcova, and Katerina Machovcova. 2018. “Occupational Well-Being among University Faculty: A Job Demands-Resources Model.” Research in Higher Education 59 (3): 325–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9467-x.

- Mukhtar, Farah. 2012. Work Life Balance and Job Satisfaction Among Faculty at Iowa State University. Iowa, United States: Iowa State University.

- Padmanabhan, Munwari, and Sampath Kumar Srinivasan. 2016. “Work–Life Balance and Work–Life Conflict on Career Advancement of Women Professionals in Information and Communication Technology Sector, Bengaluru, India.” International Journal of Research – GRANTHAALAYAH 4 (6): 119–130. https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v4.i6.2016.2645.

- Peek, Caspar, Wassana Im-Em, and Rattanaporn Tangthanaseth. 2016. The State of Thailand’s Population: 2015 Features of Thai Families in the Era of Low Fertility and Longevity. The United Nations Population Fund Thailand and the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. https://thailand.unfpa.org/en/publications/state-thailand%E2%80%99s-population-report-2015

- Phetpankan, Nichakarn, and Thanasuwit Thabhiranrak. 2018. “The Effect of Quality of Working Life on Employee Loyalty: A Case of Academic Supporting Staff of Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University, Thailand.” Paper Presented at the 17th Global Business Research Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 5–6 April 2018.

- Rajabimajd, Nilofar, Zainab Alimoradi, and Mark D. Griffiths. 2021. “Impact of COVID-19-Related Fear and Anxiety on Job Attributes: A Systematic Review.” Asian Journal of Social Health and Behavior 4 (2): 51–55. https://doi.org/10.4103/shb.shb_24_21.

- Rao, T. S. Sathyanarayana, and Vishal Indla. 2010. “Work, Family or Personal Life: Why Not All Three?” Indian Journal of Psychiatry 52 (4): 295–297. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.74301.

- Rojanaporn, Thapanan, Snitnuth Niyomsin, and Phuwanat Bangpan. 2022. “Employee Preference for Flexible Work Arrangements: A Case Study of a Business Service Unit in a Multinational Company in Thailand.” Journal of Business Administration and Social Sciences Ramkhamhaeng University 5 (1): 73–85.

- Saltmarsh, Sue, and Holly Randell-Moon. 2015. “Managing the Risky Humanity of Academic Workers: Risk and Reciprocity in University Work–Life Balance Policies.” Policy Futures in Education 13 (5): 662–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210315579552.

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B. 2017. “Applying the Job Demands–Resources Model.” Organizational Dynamics 46 (2): 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.008.

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Toon W. Taris. 2014. “A Critical Review of the Job Demands–Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health.” In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach, edited by Georg F. Bauer and Oliver Hämmig, 43–68. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Schober, Patrick, Christa Boer, and Lothar A. Schwarte. 2018. “Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation.” Anesthesia and Analgesia 126 (5): 1763–1768. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000002864.

- Singh, Rita Gill. 2020. An Exploratory Qualitative Study on the Experiences of Work and Life Outside Work of Women Academic and Teaching Staff in Higher Education in Hong Kong. Leicester, UK: University of Leicester. https://doi.org/10.25392/leicester.data.12661547.v1

- Sirgy, M. Joseph, and Dong-Jin Lee. 2018. “Work–Life Balance: An Integrative Review.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 13 (1): 229–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9509-8.

- Tamunomiebi, Miebaka Dagogo, and Constance Oyibo. 2020. “Work–Life Balance and Employee Performance: A Literature Review.” European Journal of Business and Management Research 5 (2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejbmr.2020.5.2.196.

- The Standard. 2022. “35pc HK Employees are on the Job An Average of 50 Hours Per Week, Study Shows.” Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.thestandard.com.hk/breaking-news/section/4/189611/35pc-HK-employees-are-on-the-job-an-average-of-50-hours-per-week,-study-shows.

- Times Higher Education. 2024. “Best Universities in Hong Kong 2024.” Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/best-universities/best-universities-hong-kong.

- Toderi, Stefano, and Cristian Balducci. 2015. “HSE Management Standards Indicator Tool and Positive Work-related Outcomes.” International Journal of Workplace Health Management 8 (2):92–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-11-2013-0044.

- University Grant Committee. 2024. “What is the Relationship of UGC with Its Funded Universities?” Accessed May 21, 2024. https://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/ugc/faq/q105.html.

- Vyas, Lina, and Nantapong Butakhieo. 2020. “The Impact of Working from Home during COVID-19 on Work and Life Domains: An Exploratory Study on Hong Kong.” Policy Design and Practice 4 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1863560.

- Vyas, Lina, Francis Cheung, and Kee Lee Chou. 2024. “Identifying the Unmet Needs in Family-Friendly Policy: Surveying Formal and Informal Support on Work–Life Conflict in Hong Kong.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 19 (1): 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10230-8.

- Vyas, Lina, Siu Yau Lee, and Kee-Lee Chou. 2017. “Utilization of Family-Friendly Policies in Hong Kong.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 28 (20): 2893–2915. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1138498.

- Wayne, Julie H., Russell Matthews, Wayne Crawford, and Wendy J. Casper. 2020. “Predictors and Processes of Satisfaction with Work–Family Balance: Examining the Role of Personal, Work, and Family Resources and Conflict and Enrichment.” Human Resource Management 59 (1): 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21971.

- Westfall, Peter H., and Kevin S. S. Henning. 2013. Understanding Advanced Statistical Methods. Vol. 543. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Winefield, Helen R., Carolyn Boyd, and Anthony H. Winefield. 2014. “Work–Family Conflict and Well-Being in University Employees.” The Journal of Psychology 148 (6): 683–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2013.822343.

- Xanthopoulou, Despoina, Arnold B. Bakker, Evangelia Demerouti, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2007. “The Role of Personal Resources in the Job Demands-Resources Model.” International Journal of Stress Management 14 (2): 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121.

- Zimmerman, Donald W., Bruno D. Zumbo, and Richard H. Williams. 2003. “Bias in Estimation and Hypothesis Testing of Correlation.” Psicológica 24 (1): 134–158.

Appendix

The questionnaire statements

Please rate your agreement with the following statements on a scale of 1–5, where: 1 = “strongly disagree”, 2 = “disagree”, 3 = “neutral”, 4 = “agree”, and 5 = “strongly agree”.