ABSTRACT

Background: School health curricula should help students choose health goals related to the Dietary Guidelines (DG) recommendations addressing obesity. We aimed to identify characteristics associated with choice of DG recommendation items.

Methods: In 12 HealthCorps affiliated high schools, students completed a 19-item web-based questionnaire that provided a personalized health-behavior feedback report to guide setting SMART (Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, Realistic, Time-bound) goals. We examined if gender, weight-status, and personalized feedback report messages were related to student-selected SMART Goals.

Results: The most frequent SMART Goals focused on breakfast (22.4%), physical activity (21.1%), and sugary beverages (20.4%). Students were more likely to choose a SMART goal related to breakfast, sugary beverages, fruit/vegetable intake or physical activity if their feedback report suggested that health behavior was problematic (p < 0.0001). Males were more likely than females to set sugary beverage goals (p < 0.05). Females tended to be more likely than males to set breakfast goals (p = 0.051). Students, who had obesity, were more likely than normal weight students to set physical activity goals (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: SMART goals choice was associated with gender and weight status. SMART goal planning with a web-based questionnaire and personalized feedback report appears to help students develop goals related to the Dietary Guidelines recommendations.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02277496.

Introduction

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports indicate that 20.6% of 12–19 year-olds have obesity (CDC Citation2017). As adolescent obesity increases the risk of developing chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, intervention to decrease the prevalence of adolescent obesity is critical (Sahoo et al. Citation2015; Pandita et al. Citation2016). As such, The Dietary Guidelines (DGs) for Americans, reissued every five years, provide the foundation for implementing obesity-related policy and educational interventions in schools across the United States (US) (USDA HHS Citation2010).

Adolescents spend a large proportion of their waking hours in a school setting; however, there is inconsistent evidence as to the effectiveness of school-based health interventions (Brown and Summerbell Citation2009). The fact that they report engaging in obesogenic behaviors frequently during the school day (e.g. consuming sugary drinks or junk food, skipping breakfast) and the apparent clustering of obesogenic behaviors in school environments (Fleary Citation2016), suggests that school health classes may provide an opportunity to administer health interventions to promote healthy behaviors and thus warrant continued research to find effective methods.

Goal setting is becoming increasingly popular in both health (Pearson Citation2012) and education (Rowe et al. Citation2016). Locke and Latham postulated that effective goals are those that select a specific intent, have clear action plans, and are challenging (Locke and Latham Citation2002). This premise set the framework for the frequently used SMART acronym (Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, Realistic, Time-bound). A systematic review by Pearson et al identified 18 studies that used SMART Goals to promote obesity-related behavior change and their review suggests that goal setting can be an effective mechanism in health interventions (Pearson Citation2012). Therefore, as noted by Cullen and Pearson et al, the specific goal setting methodology is important in predicting goal achievement. (Cullen et al. Citation2001; Pearson Citation2012)

Evidence suggests that developing a SMART Goal via shared decision-making between participant and coach can be highly effective in weight management and nutrition programs (Pearson Citation2012). However, tools and curricula supporting personalized SMART goals related to weight management are lacking in high school curricula. To this end, we developed and implemented our HealthyMe curriculum, which consists of four modules and uses a web-based health behavior questionnaire to generate a personalized DGs feedback report. We then aimed to identify characteristics associated with student choice of SMART goals related to the DGs items.

Materials and methods

Setting

HealthCorps is a nonprofit organization that partners with low-resourced high schools throughout the US to provide health and wellness programming (HealthCorps Citation2017). Each participating school is assigned a HealthCorps coordinator who administers classroom-based and school-wide wellness activities and lessons. The classroom-based curriculum is developed in partnership with curriculum and health experts and is aligned with the US Health Education Standards (CDC Citation2016).

Depending on the school’s schedule, HealthCorps coordinators teach classroom-based lessons 2–4 times each month during regularly scheduled class periods such as health class, advisory, or physical education. Classes are typically taught in a classroom or computer lab setting and the classroom teacher is present while the HealthCorps coordinator teaches.

A total of 21 high schools across 8 states in the US administered the HealthCorps program during the 2016–2017 school year. HealthCorps selected schools based on the following criteria: 1) having a student population with low household income (50% or more of students eligible for free or reduced-price school meals), 2) willing to implement HealthCorps programming (memorandum of understanding signed by the school principal and HealthCorps) and 3) able to secure funding from governmental or private agency sponsors. Administrative agreement to provide data for the HealthyMe Modules evaluation was obtained from 12 of the schools in 6 states. Administrators from 9 schools declined participation, indicating lack of time limited their ability to obtain the administrative or Institutional Review Board approval needed for their school to provide evaluation data. No formal evaluation was performed with regard to the characteristics of schools that did and did not participate in the present study. However, because HealthCorps aims to provide programming in low-resourced schools, it is anticipated the student populations were similar in terms of their socio-demographic characteristics.

Participants

A total of 1,219 students were invited to participate in the study, of which 1,156 provided authorization (97%). We excluded 31 students who did not provide gender data, resulting in 1,125 for the present analysis. For obesity outcome analyses, an additional 109 students were excluded due to missing or biologically implausible BMI values.

Protection of human subjects

The Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all study procedures. Additionally, where applicable, local school district IRB approvals were obtained. Because the intervention is part of HealthCorps’ standard classroom-based curriculum, all students enrolled in a HealthCorps class were exposed to the intervention activities but data were only collected from students who provided informed consent. Consent to collect and analyze the data was obtained by the HealthCorps coordinator through both a parent/guardian informed consent and a student assent. In one school, active parental consent was required by local district policies, but in the remaining 11 schools, parent/guardian consent was obtained via passive/opt-out Informed Consent Form (all parent/guardian consent forms were available in English and Spanish). Written assent was obtained from all participating students (available in English only).

HealthyMe curriculum and evaluation procedures

The HealthyMe curriculum is designed to help students develop personalized behavior goals related the DGs for addressing adolescent obesity. It consists of four modules as a subset of the full 29 module HealthCorps Curriculum. In most cases each module is taught during one 45-minute class period. Modules 1–3 are taught consecutively, Module 4 is taught at the end of the semester. The entire intervention lasts approximately 12 weeks. For the purposes of this paper, our evaluation entailed analysis of the associations between student questionnaire responses (Module 2) and SMART Goal categories selected (Module 3). Subsequent papers will address evaluation of other curriculum components. Details regarding the development of the HealthyMe modules have been extensively reported by Lounsbury et al. (CitationForthcoming). The HealthyMe evaluation is a component of a school wellness study, which is registered at the ClinicalTrials.gov registry with trial number NCT02277496. Modules can all be accessed at www.ck12.org (CK-12 Citation2017).

In Module 1 (Dietary Guidelines Recommendations) the HealthCorps Coordinator engages students in a variety of activities to help them learn about the DGs recommendations. In Module 2 (HealthyMe Snapshot), students complete the web-based 19-item health behavior questionnaire. The survey is used to generate a personalized feedback report. In Module 3 (SMART Goals), the coordinator guides students through a lesson about SMART goals. Students then set personal health-related goals that they want to work toward achieving throughout the semester. Throughout the remaining weeks in the semester, HealthCorps Coordinators incorporate SMART Goal activities, intended to maintain student engagement and motivation, into their lessons. Finally, at the end of the semester in Module 4 (HealthyMe Reflection), the HealthCorps coordinator guides students through an exercise reflecting upon their SMART goal experience, helping them to extend, or set a new SMART goal if desired. As this is the conclusion of the semester, no further follow-up is conducted after Module 4.

The SMART goal activities in Module 3 focus on determining a specific behavior to target and develop actionable tactics that will help one achieve the behavior target. The transtheoretical model suggests that to most effectively enact behavior change, one must develop a goal that best fits the stage of behavioral change readiness in which the student resides (e.g. pre-contemplative, contemplative, etc.) (Prochaska and Velicer Citation1997). Students, in order to self-reflect on their personal readiness to make change, developed a list of facilitators (such as access to healthy school breakfast) and barriers (such as an after-school job that prevents one from joining a sports team) to accomplishing the goal. This process helped them to select a goal most fitting to their personal readiness. The measurable and time-bound components of the SMART goal gave students the self-accountability that Pearson et al discuss as a key component to successful goal setting (Pearson Citation2012). During the SMART Goal module students were encouraged to consider feedback from their report, but were given freedom to choose a goal that most resonates with their personal priorities as well as their readiness to make change. A worksheet was used to assist students in creating, and outlining a plan to accomplish goals that met each of the SMART criteria.

Training and monitoring of curriculum implementation

Training

HealthCorps coordinators participated in 20 training sessions, which addressed implementation of the four HealthyMe modules as components of the overall HealthCorps curriculum. Training included in-person sessions (5-day initial and 4-day mid-year) as well as virtual sessions (videos, online working groups, and live web-based trainings). The coordinators received instruction on how to deliver the modules, developed overall teaching and motivational skills, and participated in applied practice by administering mock programming activities. All curriculum components were available to the coordinators through the CK-12 curriculum management website (CK-12 Citation2017).

Evaluation of intervention fidelity

The research team used classroom observations and feedback surveys to evaluate the fidelity of implementing the HealthyMe modules. HealthCorps supervisors observed and evaluated intervention implementation using a 3-point rating scale (strong, room for improvement, needs support) to indicate how well the Coordinator addressed learning objectives, engaged students, encouraged active participation, and managed classroom challenges. A semi-structured instrument was used to identify strengths and weaknesses. Additionally, school-staff feedback was collected through interviews and survey. These included qualitative assessment of overall satisfaction elaborating on specific strengths and weaknesses and a quantitative 4-point scale measuring school administration satisfaction with program delivery. Deviations and concerns were addressed using skills training and mentoring.

Study measures and data collection

HealthyMe snapshot questionnaire

The 19-item HealthyMe Snapshot questionnaire is completed online by all students participating in the classroom-based HealthCorps program. The questionnaire assesses demographics (5 items), self-reported height/weight (2 items), mental health (2 items), and DGs recommendation domains related to adolescent obesity [fruit/vegetable (2 items), sugary beverages (2 items), physical activity (2 items), breakfast (1 item), sedentary behavior (1 item), junk/fast food (2 items)]. The initial questions were derived from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) questionnaire to assess BMI and the six domains related to adolescent obesity from the 2010–2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (CDC Citation2017).

Using a participatory action research (PAR) approach, the questionnaire was modified based on student input to better engage adolescents (Olshansky et al. Citation2005). Our modifications included using less formal language to make it more relatable to the adolescent age group. Notably, wording was simplified and questions requiring students to recall exact quantities/frequencies were avoided and were replaced with questions asking about “typical” or “usual” behavior. Frequency questions measured how often particular foods and/or beverages were consumed (such as sugary beverages and fast food) as well as how often students participated in particular activities (such as physical exercise and screen time as proxy for sedentary behavior). Two additional questions were derived from the Patient Health Quesitonnaire-2 (PHQ2) to measure a seventh domain: mental health. (Spitzer Citation1999).

HealthyMe snapshot feedback report

In order to offer students the opportunity to reflect on their current health behaviors, and in-effect improve their likelihood of initiating behavior change, a HealthyMe Snapshot feedback report was generated for each student. The feedback report was automatically generated from their multiple-choice responses to the HealthyMe Snapshot questionnaire using an algorithm derived from the six DGs domains (USDA HHS Citation2010). The algorithm used a 3-point Likert scoring system (1 = not meeting DGs recommendation, 2 = partially meeting DGs recommendation, and 3 = meeting DGs recommendation) to create the feedback report. Students received feedback for each of the DGs recommendations categories which include: 1) increase consumption of fruits/vegetables to 2 ½ cups per day, 2) increase frequency of breakfast, 3) be physically active at least 1 hour each day, 4) decrease consumption of sugary beverages, 5) decrease consumption of fast food/junk food, and 6) reduce sedentary behavior to <2 hours per day.

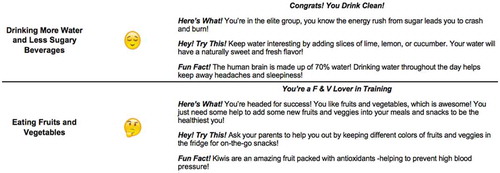

Students not achieving a particular DGs recommendation received suggestions for developing a goal related to contemplating behavioral changes e.g. “consider the pros and cons of reducing screen time”. Students meeting or partially meeting a DGs recommendation were encouraged to maintain, or to improve it with positive reinforcement and motivational messaging (Lounsbury et al. CitationForthcoming). Emoji illustrations (achieving the DGs recommendation- Relieved Face, partially achieving the DG recommendation- Thinking Face, achieving none or little of the DG recommendation- Anguished Face) were included in the feedback report to provide a visual cue in addition to written feedback (Unicode Citation2017). Sample feedback report messaging can be found in .

Self-reported height and weight

Self-reported height and weight items were used to calculate sex-age-adjusted BMI percentiles based upon the 2000 CDC growth curves (Kuczmarski et al. Citation2002; Cole et al. Citation2005). Obesity status was categorized using the sex-age-adjusted BMI as follows: <85th percentile categorized as normal weight, ≥85th – 95th percentile categorized as overweight, and ≥95th percentile categorized as having obesity (Barlow Citation2007).

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized using mean and standard deviation. Chi-square tests were used to test associations of SMART goal category variables with DG scores, weight status, and gender. We note that testing association of the following goal categories was not performed due to small sample sizes of students who chose the particular category: sedentary behavior, mental health, and other. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of participating students

The characteristics are summarized in . Mean BMI was similar between male and female; however a significantly larger proportion of males (21.5%) had obesity compared to females (14.9%) (p = 0.007).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics by gender1 n = 1,125 students.

SMART Goal category selection

summarizes SMART Goal categories selected by the students by gender. Overall, breakfast (22.4%), physical activity (21%), and sugary beverages (20.4%) were the most frequently selected goals. Least frequently selected goals across all students were sedentary behavior (4.3%) and mental health (2.8%). Male students were more likely than females to select goals related to sugary beverage consumption (23.2% vs.18.3%, p = 0.046). Females tended to be more likely than males to set goals related to breakfast consumption (24.9% vs. 19.1%, p = 0.051). summarizes SMART Goal categories by weight status. Students who had obesity chose goals related to physical activity more often than normal weight students (27.2% vs. 20.3%, p = 0.047). Normal weight students tended to choose breakfast-related goals more frequently than students who had obesity (23.1% vs. 17.2%, p = 0.09).

Table 2. Selected dietary guideline SMART Goals by gender, n = 1,125 students.

Table 3. Selected dietary guideline SMART Goals by weight category, n = 1,016 students.

Health behavior feedback report

illustrates the SMART Goal domain selected by students categorized by whether or not they are meeting DGs recommendations in that domain. As an example, of 474 students not achieving the Breakfast DGs recommendation, 178 (37.6%) selected a breakfast-related SMART goal. We found that students whose feedback indicated they were not achieving or only partially achieving the recommendations related to breakfast, sugary drinks, fruits/vegetables, and physical activity were more likely to choose goals related to that domain than students who received feedback that they were achieving the recommendation (p < 0.0001) as shown in .

Table 4. Feedback report as a predictor of Smart Goal domain selected.

Discussion

The most frequently chosen SMART goals were related to DGs recommendations that focused on eating breakfast, increasing physical activity and decreasing intake of sugary beverages. It is notable that selecting a SMART goal related to breakfast, sugary beverages, physical activity, or fruit/vegetable intake was associated with receiving “negative” feedback related to the corresponding DGs behavior. Male students were more likely than the females to set sugary beverage goals while female students were more likely than males to set breakfast goals. Students who had obesity were more likely than normal weight students to set physical activity goals.

The four HealthyMe modules support adolescents in tailoring their experience by helping them to set SMART Goals based upon a personalized health-behavior feedback report (Newnham-Kanas et al. Citation2008; van Zandvoort et al. Citation2009). This approach to personalizing the intervention experience by setting individual SMART goals may be an effective way to help students promote behavior change and ultimately improve outcomes in obesity-targeted health interventions by recognizing behaviors requiring improvement. Cullen defines “Recognition of problem” to be the first step in goal setting, noting that becoming aware of a negative health behavior can illicit intention to make change (Cullen et al. Citation2001). Because our students tended to select goals related to a behavior in which they were not meeting recommendations, goal setting using a personalized feedback report does appear to help students tailor their school-based wellness intervention experience.

Our finding male students were more likely to set sugary beverage goals may not be surprising. The CDC has reported that male adolescents consume significantly more sugary beverages than female adolescents (Zabinski et al. Citation2003, Ogden Citation2011). Possibly, the males in this study were more aware of their need to reduce intake, or have more opportunity to improve due to the high consumption already taking place. Females, in contrast, were more likely to set goals related to breakfast consumption than males. Students who had obesity were more likely to choose a physical activity goal than normal weight students. This finding was surprising. In a recent study, Zubinski found adolescents who are overweight report significantly more barriers to participating in physical activity than their normal weight counterparts (Zabinski et al. Citation2003). Despite these barriers, it seems that students in our study still felt motivated to set goals related to physical activity. It is notable, contrary to our intuition that selection of physical activity goals would differ between genders, males and females set goals in this category at a similar rate. This finding may be attributed to increasing efforts to include females in athletics, as well as extracurricular programs such as Girls on the Run. More research, including participatory action methods or focus groups, might be needed to better understand this encouraging finding.

Students chose SMART goals to reduce sedentary behavior infrequently. This finding appears to be counter-intuitive, especially as the related category of physical activity was a popular choice. Feedback from students and HealthCorps coordinators suggested that students struggled to develop an actionable plan to not be sedentary. Students instead found it easier to plan physical activity goals where they selected a particular way to become active each day. This co-occurrence was also noted in Fleary’s study that one must use caution against assuming that increasing physical activity will automatically decrease sedentary behavior (Fleary Citation2016). This topic is worthy of further investigation as currently there is a fair amount of messaging to adolescents about reducing sedentary behavior, specifically screen time. Nonetheless, our research, as well as Fleary, suggests that setting and implementing goals to do this may be difficult for adolescents.

Another less frequently selected goal category was mental health. Feedback suggested that the students were interested in working toward mental health related goals such as coping better with anger or stress. But many students found it challenging to set goals that met the SMART criteria especially in terms of “Specific” and “Measureable”. Unlike what one does or does not eat, coping skills apply to frequently unexpected and unplanned scenarios. Students struggled to set goals for these unexpected scenarios that met the SMART criteria. As mental health is an important public health concern, more research should be conducted to better determine how adolescents may work toward this category of goal.

Personalized feedback report predicting goal category

Our results suggest that receiving feedback indicating a particular behavior needs improving may encourage students to select that behavior in goal setting. The transtheoretical model postulates that behavior modification requires decisional balance, self-efficacy, and “consciousness raising” (Prochaska and Velicer Citation1997; Palmeira et al. Citation2007). In the case of our SMART Goal modules, students were provided the opportunity to match their experiences to both the process at which they would like to engage (selecting specific activities) as well as the stage at which they are ready to commit (selecting frequency, or timeframe of the activities). Goal setting theory and the transtheoretical model both suggest that this type of specific goal development will improve the likelihood of successful behavior change (Locke and Latham Citation2002; Pearson Citation2012).

While the relationship between personalized feedback and the selected goal domain was generally evident, it was not found to be the case in all domains. Of particular interest is the case of sedentary behavior which, in addition to lacking significant association with the feedback report, was one of the least selected goals. It is possible that goals with stronger associations to social norms may be more difficult to change, and thus a less desirable choice. In the case of sedentary behavior (often perceived as screen-time) social media, video games, and media-viewing apps, not to mention computer-based homework, may be so pervasive in adolescent life that students feel they are unable to limit this activity. This is troubling, however, as evidence strongly suggests screen-time predicts poor health, including obesity, in adolescents (Rosen et al. Citation2014).

Another area that requires further research is how the specific language in the messages affected student decisions. While the messages were carefully constructed and tested, it is possible that some messages were interpreted as more or less motivating than was originally intended. The research team will use the results from this study, as well as additional mixed-methods analyses, to further refine the messaging.

Strengths

A key strength of this evaluation was that it was conducted in a real-world school setting. School environments are complex and challenging: absenteeism, behavioral concerns, competing priorities, access to technology are just a few of the obstacles our team faced when implementing the HealthyMe modules. While challenging, it also allowed us to learn about the technical logistics of the curriculum first-hand.

Another strength of the evaluation was the real-time mechanism of feedback between the research and curriculum implementation teams. The partner organizations were close collaborators with pre-agreed procedures for communication and feedback. This allowed the team to not only implement the curriculum effectively, but also to notify the research team expeditiously when problems arose.

Limitations

As is the case in school-based settings, controlling the research parameters was a challenge. Day-to-day schedule changes, access to computers and student absences made it challenging to administer the program and collect data. While this real-world implementation does bolster our ability to conduct process evaluation, logistics made it difficult to follow the strict research protocols required to conduct outcome evaluation.

The present research relied on self-reported behavioral and weight data which could be affected by socially desirable responses. Data collection did not include any pre-post behavioral assessment using questions that were independent of data used for feedback and goal setting. Our evaluation did not address whether students were able to achieve the SMART goal they selected or whether any weight change was associated with completing the HealthyMe modules. Both pre- post behavioral assessments and SMART goal achievement evaluations will be included in upcoming evaluation protocols.

Some of the goal categories were selected by only a small sub-set of students making it difficult to draw conclusions. In addition, because 9 of the 21 schools chose to not provide evaluation data, we were unable to draw conclusions across the entire HealthCorps population. Lastly, it is unknown whether the findings can be generalized to schools that are not affiliated with HealthCorps.

Implications

While this analysis did not evaluate the modules outside of the embedded HealthCorps classroom-based wellness programming, they should be considered as a possible component for a variety of wellness related interventions. Using SMART goals to help students to personalize any wellness intervention experience, whether it is school or clinic-based, could be a great opportunity to increase engagement and improve outcomes. The public can access the HealthyMe Survey and Snapshot tool at www.healthymejourney.com.

Conclusion

Setting SMART goals based upon computer generated feedback reports may be an effective way to tailor obesity related health interventions in high schools. Students in this study, with help from their personalized feedback report, frequently selected goals based upon a health behavior category in which they were not meeting recommendations. This co-acquisition of goal selection, paired with follow-up support, can be an effective method to promote health behavior change. To examine this proposition, the next steps will be to measure to what extent the students enrolled in a HealthCorps classroom-based program were able to achieve their SMART goals and improve health behavior outcomes accordingly.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.4 KB)Acknowledgments

This study is registered as a clinical trial at the ClinicalTrials.gov registry with trial number NCT02277496, and was supported in part by NIH grants R01DK097096 and P30DK111022.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barlow SE. 2007. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 120(Suppl 4):S164–S192.

- Brown T, Summerbell C. 2009. Systematic review of school-based interventions that focus on changing dietary intake and physical activity levels to prevent childhood obesity: an update to the obesity guidance produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obes Rev. 10(1):110–141.

- CDC. 2016. National health education standards. [ updated 2016 Aug 18]. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/standards/index.htm.

- CDC. 2017. Trends in the Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States 2015–2016. Oct.

- CK-12. 2017. [accessed 2018 Dec 1]. https://www.ck12.org/tebook/HealthCorps-You-Skills-For-A-Healthy-You/

- Cole TJ, Faith MS, Pietrobelli A, Heo M. 2005. What is the best measure of adiposity change in growing children: BMI, BMI %, BMI z-score or BMI centile? Eur J Clin Nutr. 59:419.

- Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Smith SP. 2001. Using goal setting as a strategy for dietary behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc. 101(5):562–566.

- Fleary SA. 2016. Combined patterns of risk for problem and obesogenic behaviors in adolescents: a latent class analysis approach. J Sch Health. 87(3):182-193.

- Girls on the Run. [accessed 2018 Dec 1]. https://www.girlsontherun.org.

- HealthCorps. 2017. [accessed 2018 Dec 1]. https://www.healthcorps.org/.

- Kuczmarski RJ. 2002. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 246:1–190.

- Locke EA, Latham GP. 2002. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol. 57(9):705–717.

- Lounsbury DW, Fredericks L, Gonzalez C, Martin SN, Lim J, Nimmer K, Heo M, Levine R, Bouchard B, Wylie-Rosett J. Forthcoming. Using systems thinking to promote skill-based wellness programming in diverse high school settings. Innovations in Collaborative Modeling. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

- Newnham-Kanas C, Irwin JD, Morrow D. 2008. Life coaching as an intervention for individuals with obesity. Int J Evidence Based Coaching Mentoring. 6:1–12.

- Ogden CL, Kit BK, Carroll MD, Park S. 2011. Consumption of sugar drinks in the United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. (71):1–8.

- Olshansky E, Sacco D, Braxter B, Dodge P, Hughes E, Ondeck M, Stubbs ML, Upvall MJ. 2005. Participatory action research to understand and reduce health disparities. Nurs Outlook. 53(3):121–126.

- Palmeira AL, Teixeira PJ, Branco TL, Martins SS, Minderico CS, Barata JT, Serpa SO, Sardinha LB. 2007. Predicting short-term weight loss using four leading health behavior change theories. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 4(1):14.

- Pandita A, Sharma D, Pandita D, Pawar S, Tariq M, Kaul A. 2016. Childhood obesity: prevention is better than cure. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 9:83–89. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S90783

- Pearson ES. 2012. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns. 87(1):32–42.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. 1997. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 12(1):38–48.

- Rosen LD, Lim AF, Felt J, Carrier LM, Cheever NA, Lara-Ruiz JM, Mendoza J, Rokkum J. 2014. Media and technology use predicts ill-being among children, preteens and teenagers independent of the negative health impacts of exercise and eating habits. Comput Human Behav. 35:364–375. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.036

- Rowe DA, Mazzotti VL, Ingram A, Lee S. 2016. Effects of goal-setting instruction on academic engagement for students at risk. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 40(1):25–35.

- Sahoo K, Sahoo B, Choudhury AK, Sofi NY, Kumar R, Bhadoria AS. 2015. Childhood obesity: causes and consequences. J Family Med Prim Care. 4(2):187–192. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.154628.

- Spitzer RL. 1999. Patient health questionnaire: PHQ. New York (NY): New York State Psychiatric Institute.

- Unicode. 2017. Unicode emoji charts 5.0. [ updated 2017 Dec 4]. http://www.unicode.org/emoji/charts-5.0/index.html.

- USDA HHS. 2010. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010.

- van Zandvoort M, Irwin JD, Morrow D. 2009. The impact of co-active life coaching on female university studetns with obesity. Int J Evidence Based Coaching Mentoring. 7:104–118.

- Zabinski MF, Saelens BE, Stein RI, Hayden‐Wade HA, Wilfley DE. 2003. Overweight children’s barriers to and support for physical activity. Obes Res. 11:238–246. doi:10.1038/oby.2003.37