ABSTRACT

The purpose of this integrative review of research is to contribute to knowledge about the relation between teaching physical education (PE) and discourses of body weight. The review consists of summarising and synthesising features focusing on how discourses on the relation between teaching PE and body weight in scientific literature in different ways shape the idea of the role of PE. The results of the review reveal that the purposes, content, and forms for teaching PE constitute three discourses of teaching PE in relation to body weight: (i) a risk discourse, (ii) a critical obesity discourse, and (iii) a pluralistic discourse. From these discourses, five different roles of PE are identified; (i) Solving obesity and inactivity, (ii) Including overweight pupils, (iii) Rejecting an obesity epidemic, (iv) Supporting and understanding overweight pupils, and (v) Transforming PE in relation to a plurality of perspectives on body weight. As a consequence, we urge practitioners to take a reflective distance towards the purpose, content, and the pedagogies they are employing in relation to discourses on body weight in order to make informed decisions regarding PE curricula.

Introduction

Obesity is often presented as one of the greatest contemporary threats to global public health, and an alarming discourse about the ‘obesity epidemic’ or ‘obesity crisis’, permeates health research and public debate (e.g. Demetriou, Gillison, & McKenzie, Citation2017; McKenzie & Lounsbery, Citation2014; Wolfenden, Ezzati, Larijani, & Dietz, 2019). The World Health Organisation further positions obesity and being overweight as one of the more severe risk factors for a number of diseases. The prevalence of obesity in children is considered a major health threat with strong concerns that it will cause serious health problems throughout life (Lee & Yoon, Citation2018). Hence, there are convincing suggestions for interventions in school and in after school programs (Demetriou et al., Citation2017; Kahan & McKenzie, Citation2015; Nerud & Steiner, Citation2019). On the other hand, this crisis discourse problematises people's bodies and projects ‘slim and slender’ as the way to be healthy. The slim, fit, and active body has become normalised while other kinds of bodies are framed as aberrant or deviant (Gard & Wright, Citation2001; Pluim & Gard, 2016; Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; Rich, De Pian, & Francombe-Webb, Citation2015). Evans, Rich, Davies, and Allwood (Citation2008, p. 13) go so far as to suggest that the obesity discourse now serves as a ‘framework of thought, talk and action concerning the body in which ‘weight’ is privileged not only as a primary determinant but as a manifest index of wellbeing surpassing all antecedent and contingent dimensions of health’.

A number of scholars have further proposed that schools, and specifically the school subject physical education (PE), has an important role to play in the curriculum in mitigating the ‘obesity epidemic’ (e.g. Kahan & McKenzie, Citation2015; McKenzie & Lounsbery, Citation2014; Pate, O'Neill, & McIver, Citation2011). Educational resources, programs and special teaching strategies have been developed in many countries in attempts to encourage children and young people to certain physical practices that either prevent or reduce the risk of overweightness and obesity (Cale, Harris, & Chen, Citation2014; Pluim & Gard, 2016). However, it has also been argued that the strong emphasis on body size and weight in the curriculum that follows from an obesity focus also excludes other ways of doing PE and that these obesity discourses are refracted through the cultural context and national curricula of PE in each particular country (e.g. Barker, Quennerstedt, Johansson, & Korp, Citation2020; Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; Webb & Quennerstedt, Citation2010).

According to Tinning (Citation2015), physical educators in many countries have in a sense joined the ‘war on obesity’ and the eradication of fat bodies has become the primary goal. At the same time, the uncritical acceptance of obesity discourses in PE runs counter to the ambition to promote health and wellbeing among all children and young people (Evans et al., Citation2008). Stigmatisation and discrimination on the basis of weight is prevalent within schools, and research suggests that oppressive ‘fat-phobic’ discourses are rife within PE (e.g. Lynagh, Cliff, & Morgan, Citation2015; Pausé, Citation2019; Sykes & McPhail, Citation2008). Young people are suffering from all kinds of body anxieties (Walseth & Tidslevold, Citation2020) and research further suggests that physical educators are the most important factor for making PE experiences positive for all (Doolittle, Rukavina, Li, Manson, & Beale, Citation2016). At the same time, other studies suggest that teachers who should be helping young people are actually contributing to body anxieties (e.g. Evans et al., Citation2008). There is consequently an urgent need to consider the work of physical educators in relation to discourses on obesity and thus the health and wellbeing of children in school. An important contribution to this discussion is a review and synthesis of current research offering potential ways forward. The overall purpose of our integrative review is accordingly to contribute to knowledge about the relation between teaching PE and discourses of body weight. Our specific aim is to identify how discourses on the relation between teaching PE and body weight in scientific literature in different ways shape the idea of the role of PE.

Method

In this study, an integrative review of research was performed to specifically explore the relation between teaching PE and discourses of body weight (Andrews & Harlen, Citation2006; Cornelius-White, Citation2007; Greenhalgh et al., Citation2005; Marston & King, Citation2006). An integrative review is a broad review method with the potential to examine different aspects of research on a particular topic (Whittemore, Citation2005). Integrative reviews can consist of quantitative and qualitative empirical papers, conceptual papers, practitioner-based papers, policy documents as well as theoretical literature. They include summarising as well as synthesising features involving, as Quennerstedt (Citation2011) argues:

… produc[ing] knowledge that reaches beyond the sum of its parts […]. Individual studies are thus combined and integrated to a whole, bringing themes and concepts together to make new concepts and theoretical insights possible. (p. 663)

The searches in the review were initially performed in January and February 2019 in the full-text databases ERIC, EBSCO and Sociological abstracts. Additional searches were made in February 2020 in order to complement our initial searches. These specific databases were selected since our ambition was to focus on educational and pedagogical literature. The search strategy combined search terms relevant to the specific aim of our investigation and involved academic journal articles as defined by each database published between 1999 and 2020, which provides a 21-year reviewing period. The time frame was chosen because we wanted a contemporary picture of the field. In our initial searches, the first papers addressing this issue appeared in 2001 and most papers in the final sample appeared after 2010 ().

Table 1. Search terms and number of articles.

We are aware of the limitations of this study, occasioned by the sole use of keywords in the English language. There is consequently no comprehensive claim for the review, and the results of the study reflect the relation in countries publishing research in English.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) published between 1999 and 2020; (ii) published in an academic journal as defined by each database; (iii) focuses on PE in school as a pedagogical practice; (iv) involves the teaching of PE or PE practice including teachers as well as pupils’ voices. Regarding this last criterion, articles focusing on specific obesity prevention programs, physical activity interventions, energy balance, physical activity or food habits, measurement of physical activity levels, BMI or overweight, and studies outside of school or in universities were excluded. We also excluded studies on parents or young people’s experiences, perceptions or perspectives on overweight that were not related to education, or studies on overweight young people in general (outside of school contexts). A first reading of the online abstracts of all articles in the searches using the inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in 36 articles. Further, by means of so-called snowballing, the reference lists of included articles were examined for additional articles within our inclusion criteria since search criteria rarely reveal all relevant literature (Streeton, Cooke, & Campbell, Citation2004). The final sample consists of 45 articles (see Appendix A).

Of the 45 articles in the sample, 19 were from USA, eight from Australia, seven from UK, six from New Zealand/Aotearoa, two from Canada, one each from Spain and Sweden, and one comparative study from Canada/Scotland. The foci of the articles were; theoretical or practitioner-based arguments about obesity and PE (n = 15), empirical studies on; pupils (n = 10), PE teachers (n = 9), PETE-students (n = 4), young women (n = 2), policy (n = 2), plus one on early childhood education, an auto ethnography, and the presentation of a theoretical model.

The analysis was made in two distinct steps. In the first step, we engaged in what Culler (1992) calls understanding. This involves clarifying what the texts say about the relation between teaching PE and discourses of body weight. Culler argues that this is an analytical strategy where the researcher asks questions that the texts ‘insists on’. Our analytical question in the first step has been: how does the text construct the relation between teaching PE and discourses on body weight in terms of purpose, content and form (why, what and how)? This builds on Quennerstedt and Larsson’s (2015) claim of the importance of:

… what, how and why, in terms of what and how teachers teach, what and how students learn and why this content or teaching is taught or learned. (Quennerstedt & Larsson, Citation2015, p. 567)

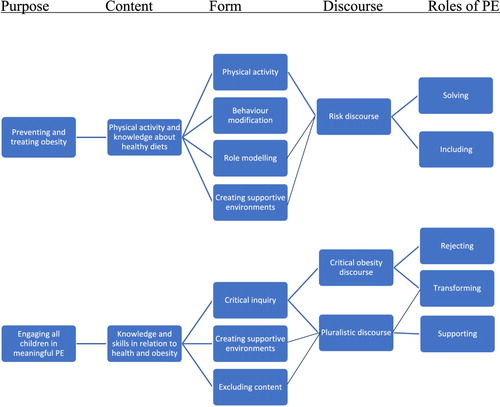

Here, themes that describe the relation are identified through distinguishing distinctly different logics regarding purpose and as a consequence content and form. This approach to analysis is supported by Quennerstedt’s (2019) contention that ‘the question of why gives education [what and how] its direction’ (p. 617). These themes are presented in . Taking the results of the first step as a starting point, the second step of the analysis – the synthesis (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2005; Quennerstedt, Citation2011), or what Culler (1992) calls overstanding – consists of a reading where we compare the themes in step one with other possible ways to explore the literature. This step involves asking questions about what is taken for granted in the text in order to reformulate the relation using discourse analytical strategies (Wetherell, Taylor, & Yates, Citation2001). In an institutional practice like PE, certain specific actions structure a field of possible actions, and these actions form patterns and regularities. By applying discourse analytical strategies, a better understanding of patterns in an institutional practice can be acquired. In this step, two analytical questions are used to identify patterns: (i) What discourses do teaching PE build on in relation to body weight? (ii) What is the role of PE in relation to the identified discourses?

Figure 1. Purposes, content and form of teaching PE in relation to discourses of body weight and roles of PE.

The synthesis is thus a shift between understanding and overstanding in terms of what the themes do in relation to PE practice and what is taken for granted regarding the role of PE in relation to body weight. In this way, we can bring research together and say something new about what happens in the nexus between discourses on body weight and the teaching practices in PE.

Results

In the first step of the analysis two major purposes (the question of why) were identified; two corresponding aspects of content (the question of what) were identified; and six forms for teaching PE (the question of how) were identified (see ).

In the second step, our synthesis revealed that the purposes, content, and forms for teaching PE in different ways constitute three discourses of teaching PE in relation to body weight through the patterns of actions and practices described: (i) a risk discourse, (ii) a critical obesity discourse, and (iii) a pluralistic discourse. From these discourses five different roles of PE are identified; (i) Solving obesity and inactivity, (ii) Including overweight pupils, (iii) Rejecting an obesity epidemic, (iv) Supporting and understanding overweight pupils, and (v) Transforming PE in relation to a plurality of perspectives on body weight (see ). It is the results of this second phase of analysis that we concentrate on below. Importantly, the different roles of PE are sometimes overlapping and identified within one and the same article. Further, references are provided throughout the results as examples rather than in an exhaustive mannerFootnote1 (for all articles used see Appendix A).

What discourses does teaching PE build on in relation to body weight?

A risk discourse

The risk discourse regarding the relation between teaching PE and body weight is clearly embedded within wider discourses on risk and obesity in society (e.g. Kahan & McKenzie, Citation2015; McKenzie & Lounsbery, Citation2014; Pate et al., Citation2011). Within the risk discourse, the purpose of teaching becomes preventing and treating obesity. PE is almost exclusively about increasing physical activity during PE lessons. Teaching should thereby help overweight students to reduce sedentary behaviours in general and in the long term, create physically active adults (Gard & Wright, Citation2001; Prusak et al., Citation2011; Stewart & Webster, Citation2018; Tingstrom, Citation2015; Varea & Underwood, Citation2016; Wrynn, Citation2011). From this perspective, PE is put forward as a public health tool (Gard & Wright, 2011; Prusak et al., Citation2011) and PE teachers are frequently positioned as the frontline in the ‘battle’ against childhood obesity (Tingstrom, Citation2015; Wrynn, Citation2011).

Within the risk discourse, content becomes physical activity and knowledge about healthy diets (Gray et al., Citation2018). This content primarily concerns doing physical activity here and now. However, the content sometimes involves offering life-long activities and hence leading students in a ‘right’ direction (Greenleaf & Weiller, Citation2005; Varea & Underwood, Citation2016). Content within the risk discourse can also concern nutrition and weight control knowledge (Butz, Citation2018; Petherick, Citation2013), and knowledge about fitness and fitness tests (Petherick, Citation2013).

Regarding the form for teaching PE, the risk discourse mainly involves providing opportunity for physical activity at a certain intensity level i.e. moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA). Behaviour modification and thus changing students’ attitudes and behaviours is another prominent feature of the risk discourse related to physical activity (Gard, Citation2011; Pringle & Pringle, Citation2012). This is done through coaching students towards correct behaviours (Prusak et al., Citation2011; Varea & Underwood, Citation2016), using outsourced physical activity programs, self-surveillance, or through introducing weight management strategies (Petrie & Clarkin-Phillips, Citation2018; Varea & Underwood, Citation2016).

The discourse also involves creating supportive environments as well as role modelling. Creating supportive environments involves encouraging effort and reducing obstacles to participation (Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016) including choices, working with ability groups, and avoiding activities that emphasise weight (Li & Rukavina, Citation2012). Role modelling is about teachers setting a good healthy example, where teachers should for example, be physically active, fit and not eat junk food (Cliff & Wright, Citation2010; Martinez-López et al., 2017).

A critical obesity discourse

The critical obesity discourse frames the purpose of PE as encouraging all children to engage in meaningful PE and physical activity. Within the discourse, PE is about critiquing hegemonic obesity discourses in society and avoiding stigmatising practices.

In terms of content, the discourse points to the social skills and critical knowledge pupils need to navigate and critique wider discourses of overweight and obesity (Doolittle et al., Citation2016; Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; Pringle & Pringle, Citation2012). The form of teaching relates to offering opportunities for critical inquiry into discourses of body weight through challenging, negotiating or deconstructing obesity discourses in PE practice (Pringle & Pringle, Citation2012). Teaching is about helping students to adopt a critical attitude and counteracting ‘obesogenic’ practices in PE and in school (Cale & Harris, Citation2013). Measuring and weighing students in PE is framed as an explicit manifestation of fat-phobia (Sykes & McPhail, Citation2008) and it is argued that all practices where size or weight is foregrounded should be avoided. Pringle and Pringle (Citation2012) further argue that PE teachers should practice critical thinking in their classes instead of telling students ‘how, when and why to move’ (p. 153). Critical pedagogies have been highlighted as a way to challenge discourses where ‘young people are prompted to interrogate arguments and evidence around overweight and the exercise = slenderness = health triplex’ (Kirk, Citation2006, p. 130).

A pluralistic discourse

The purpose of the pluralistic discourse is to engage all children fully in meaningful PE in order to ensure that they can engage fully and safely in relation to a plurality of perspectives on body weight. In this discourse, care is central. Obesity discourses are acknowledged in statements like: ‘all children including overweight children’ (Cale & Harris, Citation2013), and by emphasising that, promoting the health and wellbeing of all children is important in PE, not only preventative efforts for overweight children.

Regarding content, activities promoting inclusion, participation, engagement and positive experiences for all students are promoted (Cale & Harris, Citation2013; Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016). At the same time, some authors suggest that certain content in relation to certain sports should be omitted by the teachers since content like team games, competitions, and fitness comparisons exclude overweight children from participation in PE. Much content is in this sense presented as potentially harmful (Sykes & McPhail, Citation2008).

Within the discourse, different ways of creating supportive environments for overweight students are further highlighted. Teaching strategies related to caring for overweight students’ wellbeing and adapting activities are frequently proposed (Li et al., Citation2017; Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016; Tingstrom, Citation2015). Different strategies of inclusion are used to reduce obstacles to participation, ensure a positive class climate, and provide a safe and positive experience (Cliff & Wright, Citation2010; Doolittle et al., Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2017; Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016; Rukavina et al., Citation2015; Stewart & Webster, Citation2018).

In creating supportive environments, some teachers try to celebrate overweight students’ strengths and skills (Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016) while others try to treat overweight students in the same way as others thus avoid labelling (Li et al., Citation2012; Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016). Other supportive teaching strategies include providing pupils’ choice of activities and individual differentiation. With respect to differentiation, a frequent claim is that a one size fits all PE approach does not work inclusively because overweight students have individual differences.

Another aspect of how to teach is, as in the critical obesity discourse, offering opportunities for critical inquiry through challenging and negotiating obesity discourses in PE practice (Pringle & Pringle, Citation2012). Teaching in relation to body weight becomes about offering opportunities for exploring issues of body weight and, as in the critical discourse, measuring and weighing students is seen as something to avoid, or at least, critique (Cale & Harris, Citation2013; Sykes & McPhail, Citation2008).

What is the role of PE in relation to discourses on body weight?

We have presented three discourses and the purpose, content and form of PE lessons that emerge within these discourses. Now we turn our attention to the comprehensive role of PE as a school subject that arises as a consequence from these discourses (see ).

Solving

A central role for PE framed by the risk discourse concerns ‘solving’ issues in society related to obesity. Here, a strong deficit-oriented risk discourse that builds on an energy in/energy out rationale intersects with the idea of PE. Childhood obesity and high levels of inactivity are positioned as one of the main health problems in society (Martínez-López et al., Citation2017) and young people are positioned as problematic (Petrie & Clarkin-Phillips, Citation2018):

The high rates of overweight and obesity have become a major public health concern … [and] … school physical education (PE) programs can play an important role in influencing the PA levels of students and should be seen as a valuable resource in the fight against overweight and obesity (Stewart & Webster, Citation2018, p. 30–31).

It is acknowledged that people may have different causes for being overweight but there is only really one combination of actions that can reduce obesity – eat less, and exercise more ‘so you don’t get fat’ (Lee & Macdonald, Citation2010, p. 208). By targeting inactivity on a societal or individual level, the problem of obesity can be solved.

From this perspective, schools are seen as ideal settings to address eating habits, weight control and physical activity promotion (Li & Rukavina, Citation2012; Martínez-López et al., Citation2017). Expert knowledge is derived from the field of biomedicine to combat the negative effects of obesity. The role of PE should as a consequence be to increase pupils’ physical activity at a moderate to vigorous level which will allow them to expend energy, and coach pupils in the ‘right’ direction (Gard & Wright, Citation2001; Varea & Underwood, Citation2016):

Physical education has two main mechanisms for getting overweight students to ‘go healthy’ and make the choice to be more active. The first mechanism is for K-12 educators to use their lesson time effectively to promote more moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). The second mechanism is to make the physical education experience sufficiently motivating for overweight students to choose to be active outside of lesson time. (Wallhead, Citation2007, p. 26)

It is taken for granted that PE participation done correctly makes students lose weight (Fitzpatrick, Citation2011) and the quality of PE lies in heart rate elevation and calorie expenditure (Gard, Citation2011). The focus of PE thus shifts to burning calories (Clark, Citation2018; Wiltshire et al., Citation2017) and the teaching of physical activity according to Powell and Fitzpatrick (Citation2015) becomes a weight management strategy. Solutions also involve developing motor competence, which should lead to more physical activity, which in turn is likely to lead to health-related fitness not seldom measured as BMI (Wrynn, Citation2011).

PE teachers in some studies agree that poor eating habits, sedentary lifestyles and excess calorie consumption to a large extent contribute to overweight (Greenleaf & Weiller, Citation2005), and weight, as the issue to be solved, is often constructed as a responsibility of the individual or a result of the immediate context (i.e. either personal or familial). From this follows that individual actions alone can lead to health benefits (Welsh & Wright, 2011). That overweight students are a problem to be addressed in PE is taken for granted (Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016), and body weight is therefore something that PE should focus on as a way of getting pupils to understand their responsibilities (Gard & Wright, Citation2001; Varea & Underwood, Citation2016; Welsh & Wright, 2011). Teachers are as a consequence:

… urged to get students more active during school time, to encourage students to avoid the so-called ‘bad’ foods, to check student lunch boxes and educate students so that they are aware of the health risks of obesity. (Pringle & Pringle, Citation2012, p. 150–51)

There is accordingly an expectation on teachers to make young people physically active, making them responsible for their activity and thus playing a role in solving obesity and inactivity.

Including

Within the risk discourse, there is also a more educational and action-oriented view of the role of PE. This view frames the purpose of PE as preventing obesity but criticises fat-phobic practices, which lead to teasing and exclusion. This line of research suggests that being obese has negative consequences such as heart disease, type II diabetes and joint problems, taking epidemiological and medical research at face value. It also acknowledges, however, that fat pupils experience stigmatisation and exclusion in PE practice. The role of PE here takes a clear critical position towards fat-phobia that is occurring ‘at every corner of the gym’ (Li & Rukavina, Citation2012, p. 312; see also Li & Rukavina, Citation2012; Lynagh et al., Citation2015; Trout & Graber, Citation2009). It is argued that PE does a poor job of including overweight students (Rukavina et al., Citation2015) where teachers show implicit anti-fat attitudes and adhere to an ideology of blame i.e. that individuals are responsible for their weight and its negative consequences (Grenleaf & Weiller, 2005).

This line of research argues that PE must abandon a one size fits all approach (Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016), and instead look at inclusive or adapted practices with an emphasis on life-long activities and supportive environments:

Teachers need to understand that overweight students have unique characteristics that make participation in a stereotypical ‘one size fits all’ physical education program challenging (Li & Rukavina, Citation2012, p. 575)

Here, it is suggested that physical educators in the role of including should provide differentiated instruction, give choice to pupils, encourage effort, focus on learning, maintain an inclusive environment, and avoid spot-lighting (Rukavina et al., Citation2015). Individualisation to fit overweight students’ needs is highlighted as essential (Rukavina et al., Citation2015). Even if obesity is emphasised as an urgent problem, the development of strategies to include overweight and obese students is superior to activity here and now (Li et al., Citation2017). Instead, the focus is on positive experiences and making physical activity enjoyable. It is accordingly about including individuals. At the same time, teachers expect ‘normal’ weight students to perform better (Tingstrom, Citation2015), and that overweight students ‘who were unmotivated, non-compliant, reluctant to try, or showed their dislike of PE’ (Li et al., Citation2012, p. 131) were of most concern for teachers. Physical educators accordingly also have a professional responsibility to educate pupils about being physically active, eating well and maintaining a healthy weight.

Rejecting

The role of rejecting is about denying the idea of what has been called an obesity epidemic in the first place and there is a strong critique of the consequences of healthism, obesity discourses, fat-phobic norms, and dominant body ideals in society and the media (Gard, Citation2011; Gard & Wright, Citation2001; Gray et al., Citation2018; Rich et al., Citation2015). The role of PE is thus to reject obesity as something to be addressed within PE.

The social construction of the obesity epidemic is considered as a moral panic which is itself harmful (Pringle & Pringle, Citation2012) since anti-fat attitudes become prevalent and overweight people are stigmatised and discriminated against (Cale & Harris, Citation2013; Grenleaf & Weiller, 2005; Tingstrom, Citation2015). A role of PE becomes critiquing the risk discourse which ‘ … perpetuate[s] current and growing biases and prejudicial beliefs concerning the overweight and obese, namely that they are weak willed, gluttonous, lazy, ugly, awkward, bad, stupid and worthless’ (Cale & Harris, Citation2013, p. 441). The argument is thus that obesity is claimed to be a problem rather than being a problem (Wrynn, Citation2011), and research suggests that in general, the obesity discourse is a normalising discourse that marginalises and excludes. It is also a moralising discourse that results in guilt, shame and embarrassment and leads to heightened self-surveillance and monitoring:

If we focus on the practice of weighing and measuring as just one example, not only is this likely to be embarrassing and humiliating for many young people, but it is not necessary to measure an obese child, or indeed any individual for that matter, to tell them something that they already know and, more importantly, no child needs to be measured to be helped to enjoy being physically active (Cale & Harris, Citation2013, p. 441).

Part of the argument is that body weight becomes a responsibility for all even if it potentially is a problem for a few (Gard & Wright, Citation2001), and this ‘rejecting’ role takes a strong oppositional position towards a purpose of PE being preventing and treating obesity. Research points at studies revealing that an implicit anti-fat bias is institutionalised in PE practice (Cliff & Wright, Citation2010; Lynagh et al., Citation2015) and the practice of measuring and weighing students in PE in the name of health is considered an explicit manifestation of fat-phobia (Sykes & McPhail, Citation2008). It is argued that teaching about how to avoid being fat prevails (Cliff & Wright, Citation2010; Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; Rukavina & Doolittle, Citation2016) and that a fat-phobic attitude is constantly negotiated by overweight students in PE (Sykes & McPhail, Citation2008):

Team games were a particularly tormenting part of physical education for several people we interviewed. For these fat students, team games seem like nothing more than ‘school-sanctioned bullying’. (Sykes & McPhail, Citation2008, p. 78)

Instead this research argues that physical educators should completely refrain from harmful practices like focusing on losing weight, weighing children, inspecting lunch boxes, issuing health report cards, fitness testing, or fat clubs for overweight kids in the name of an alleged ‘obesity epidemic’ (Gard & Wright, Citation2001; Sykes & McPhail, Citation2008).

Supporting

In the supporting role of PE, body weight is recognised as an issue for many people in their daily lives. In this case, however, weight and in particular overweight is not exclusively considered as a medical risk as in the risk discourse but as a social construction with real consequences (Wrynn, Citation2011). The supporting role is embedded within a pluralistic discourse where multiple truths about body weight as health issues are put forward. There is no certainty about the consequences of obesity and different shapes and sizes can accordingly be desirable as ideal or healthy bodies (Gray et al., Citation2018). Supporting PE takes a starting point in trying to understand the different experiences of overweight people in different social and cultural contexts. Fat-friendly and fat-positive pedagogies are proposed with the ambition to advocate physical activity and movement as enjoyable and ‘good for you’, as the following example from the USA shows:

… standards-based PE will benefit students who are overweight or obese in that it creates a safe, inclusive learning environment that helps to support confidence and motivation in PA participation […] These strategies will promote positive interactions between students who are overweight or obese with their peers, thus targeting perceived interpersonal and environmental barriers. (Stewart & Webster, Citation2018, p. 31)

The role of supporting suggests that trying to solve obesity problems by reducing the weight of pupils has clear negative consequences such as depression, low self-esteem, poor body image, maladaptive eating disorders, and exercise avoidance. Instead, the first priority of professional practice is to ‘do no harm’, and physical educators break that rule when they try to reduce the weight of their pupils. Research suggests that overweight students experience negative prejudice often related to social comparison, and weight-related teasing is reported in PE settings (e.g. Cale & Harris, Citation2013; Li & Rukavina, Citation2012). These experiences disengage overweight pupils from movement (Li & Rukavina, Citation2012). The role presented is thus to stop trying to reduce the weight of pupils and instead try to support young people as they try to navigate the plethora of issues surrounding weight:

We contend that ‘every child of every size matters’ and can benefit from regular engagement in physical education and physical activity and furthermore that, as a profession, we have a responsibility to provide all young people, of all sizes, with meaningful, relevant and positive physical education and physical activity experiences. (Cale & Harris, Citation2013, p. 433)

These various experiences are taken as a starting point for how to support pupils in PE, and the question of movement and physical activity is shifted from here and now to enjoying movement in a life-long perspective. However, in contrast to the including role, obesity is not taken at face value and the content of PE is not taken for granted as necessarily being about physical activity, sport and prevention of sedentary behaviours.

Transforming

The role of transforming is both related to a pluralistic discourse and a critical obesity discourse. Within a critical obesity discourse, the role of PE is to develop knowledge in order to be able to unpack the surveillance, disciplining and regulation that occur as a consequence of the obesity epidemic. In a sense, it is about transforming peoples’ views and freeing them from the obesity discourse through critical inquiry. A few papers are further identified in a pluralistic discourse where the pedagogical consequences of different discourses are embraced and where multiple truths about both health and the value of different body shapes and body sizes are considered (e.g. Cale & Harris, Citation2013; Landi, Citation2018; Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; Rich et al., Citation2015):

Instead of reproducing obesity discourses through fitness lessons, teachers might use the children’s understandings of fitness and fatness as a ‘springboard’ to begin conversations about the relationship between fitness and fatness. Instead of asking students to reproduce supposed ‘correct’ answers about fitness, teachers might instead challenge students ‘to explore, critique, and reconstruct normative discourses and practices around the body’ (Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015, p. 481).

Different social factors like social class and gender are highlighted as crucial and the responsibility for body weight is shifted away from the individual towards social circumstances. In contrast to the including role where inclusion was about individuals, it is here about the inclusion of perspectives. It is recognised that competing discourses on overweight create pedagogical tensions. The role of PE is to problematise the function of different discourses in relation to body weight and thus transforming what PE is about. It is about educating all pupils, asking all to inquire into weight as an issue in society. Pupils should accordingly be educated towards negotiating and critically deconstructing issues of body weight and body form, and ‘ … ‘educational’ benefits could be gained through a guided process of critical evaluation of the competing obesity discourses’ (Pringle & Pringle, Citation2012, p. 154). From this perspective, teachers are expected to traverse dominant health discourses in terms of what it means to be healthy, and building education on multiple truths of what a healthy body is (Welsh & Wright, 2011). Here critical pedagogies, social justice education and queer inclusive PE are suggested as ways forward for alternative body pedagogies where teachers can challenge pupils to critically reflect on taken for granted notions of body weight in the context of PE. This involves challenging taken for granted assumptions about ourselves and others as well as offering opportunities to change oppressive, unfair and unsustainable PE practices in school and in society (e.g. Cale & Harris, Citation2013; Kirk, Citation2006; Landi, Citation2018; Powell & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015).

Discussion

The overall purpose of this integrative review of research has been to contribute to knowledge about the relation between teaching PE and discourses of body weight, and how discourses on the relation in different ways shape the idea of the role of PE. We have accordingly tried to combine the results and arguments in the included articles beyond the sum of each paper in order to make new insights possible. In the following discussion, we will consider the consequences of our synthesis in terms of (i) the role of PE, (ii) the teaching of PE, and (iii) indications into how we can move beyond the current tensions between discourses of body weight in PE through a focus on its different roles. We argue that it is about finding the middle ground where PE teachers can go beyond taking sides in a polarised debate and instead look towards how PE can be more socially just for all students.

What is the role of PE in relation to body weight?

This integrative review of research reveals that there are distinct differences in how research constructs the relation between teaching PE and discourses on body weight in terms of purpose, content and form (why, what and how). As we have shown, these purposes, contents, and forms have different consequences for how the role of PE is accentuated. If an obesity epidemic is taken for granted within a risk discourse, then the role of PE is either being part of solving problems related to inactivity, sedentary behaviour and being overweight, or negotiating the negative impact of an obesity discourse by trying to include overweight pupils in PE practice. If on the other hand obesity is taken as something rather claimed to be a problem, then the roles of PE are about rejecting the issue all together or critically inquiring into the damaging effects of the obesity discourse. In a sense, one extreme aims to free pupils from the obesity discourse – in other words, free them from their social milieus, while the other is trying to emancipate some pupils from their bodies – in other words, from the biological. These two positions are often juxtaposed in the debate (see Tinning, Citation2015) and the first is frequently advocated within a US context while the other often is from scholars in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and UK. Rich et al. (Citation2015) talk about an ‘impasse’ (p. 2), which might be the case if these two strands of literature ever met one another. They seldom reference each other and rarely build on each other’s insights. A third position in this polarised academic conversation is however within what we identified as a pluralistic discourse where multiple truths and perspectives about body weight are embraced and even welcomed. Being overweight is here regarded as a construction but with real consequences within people’s everyday experiences. Issues of weight and form are seen as a mixture of socio-cultural context, genetics and individual lifestyles. This plurality and complexity is not seldom bracketed in the two polarised arguments above, and therefore the roles of PE of including, supporting and transforming often become hidden, roles that when looking at what PE teachers do in their everyday work has a lot in common.

Teaching PE in relation to body weight

So how can these different roles for PE become useful for PE teachers? As we see it, the identified roles of PE in relation to discourses of body weight pinpoint various purposes, content and processes – the why(s), what(s) and how(s) of PE – as more reasonable than others. The different roles also have consequences for what pupils should learn in PE and what they should know through participating in PE.

The role of solving means providing as much physical activity engagement as possible during PE lessons and students are expected to develop knowledge and abilities promoting increased levels of physical activity. The role of including is about teaching PE according to its traditions and policy documents while at the same time making sure that overweight and obese students are included as much as possible in order to counteract any barriers to physical activity participation. The role of rejecting means to teach so that body weight and body form does not become an issue at all for PE and thus creating educational situations where weight is not on the agenda. Supporting is further a role for PE that is about taking a point of departure in understanding the different experiences of pupils with different body weight. It is about ‘doing no harm’ and thus supporting pupils towards meaningful PE participation. Finally, the role of transforming is about changing both the content of PE to ensure meaningful participation for all students as well as transforming the educational situation where, as Quennerstedt (Citation2019) argues:

… teaching embraces the responsibility of bringing something to the educational situations that the students have not asked for […]. In this sense, there is a potential to discuss and design transformative and genuinely pluralistic physical education practices (p. 620).

It is accordingly not mainly about including or transforming the young people themselves but instead including various perspectives to open up different ways of being in the world.

Moving beyond current tensions?

That research and researchers hold different positions and that as a consequence, there are different arguments about the role of PE in school is quite reasonable. However, when research holds incommensurable positions, practitioners, in this case PE teachers, potentially have to take sides between the positions of PE as a public health tool versus PE as being educative (Quennerstedt, Citation2019). Even so, our review reveals that the roles of including, rejecting, supporting and transforming are quite compatible, as long as the purpose of PE is about the engagement of all children in meaningful PE and not about preventing or treating obesity. In a sense, this means dissolving rather than solving the dichotomous positions and thus moving beyond an impossible debate for the teacher. The pluralistic discourse in this way constitutes a middle ground between an apparent polarised field of tension in research. Within the pluralistic discourse where the transforming and supporting roles are already located in research, inclusion becomes the ambition to include all children in a diversity of practices. It is often with the overall aim of promoting health and wellbeing, but not taking for granted that children’s body weight is the problem. Rejecting becomes a rejection of obesity as the problem for PE without rejecting the day-to-day experiences of people defined or stigmatised by the obesity discourse as overweight and instead critically inquiring into the consequences of the obesity discourse.

Consequently, we would urge teachers to take a reflective distance towards the purpose, content and the pedagogies they employ in relation to discourses on body weight in order to make informed decisions regarding the role of PE as well as on the consequences for their teaching. Here we agree with Quennerstedt (Citation2019) who has argued that teaching always has to start with deciding on the purpose of education – the question of why – and then ‘viewing PE practice as open-ended in terms of different possibilities, different ways of being or diverse opportunities to be for example healthy, however, these are construed’ (Quennerstedt, Citation2019, p. 620).

In line with Quennerstedt and our own conclusions above, Cale and Harris (Citation2013) provide an explicit example in our review of this kind of pluralistic position with clear practical consequences and advice. They are distinctly straddling and moving beyond the two sometimes incommensurable positions and suggesting a tenable position beyond. They achieve this position by: acknowledging crisis production; providing statistics with the proviso that there is crisis production happening; acknowledging the limitations of all kinds of research; acknowledging ‘fat-phobia’ and stigmatisation on the basis of weight within PE practice, acknowledging health problems that can come from being ‘overweight’; noting that different factors contribute to people’s weights; and then concluding with some recommendations. So instead of taking sides as a teacher, it becomes a question of moving beyond an either-or argument and instead looking at how PE can be more socially just for all students with a diversity of bodies and body forms and thus trying to make PE more educative and socially just for all students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mikael Quennerstedt

Mikael Quennerstedt is professor in Physical Education and Health at Örebro University, Sweden. He has worked as a physical education teacher in Swedish compulsory school, and as a physical education teacher educator. His work focuses on teaching and learning in physical education from a Swedish didaktik research tradition, as well as health education from a salutogenic perspective.

Dean Barker

Dean Barker is associate professor at the School of Health Sciences, Örebro University, Sweden. His research focuses on aspects of learning in physical education and the articulations of theory and practice.

Anna Johansson

Anna Johansson holds a PhD in Sociology and is Senior Lecturer at University West, Sweden. Her principal areas of research are gender studies, resistance studies and critical fat studies. She returns to a number of central concepts, the most important being power and resistance and how it operates through categorisations such as gender, race, sexuality, class, identity and body. Recent publications include “Fat, Black and Unapologetic: Body Positive Activism Beyond White, Neoliberal Rights Discourse” (2020).

Peter Korp

Peter Korp is Associate Professor in Sociology at the Department of Food and Nutrition, and Sport Science, University of Gothenburg. Peters research has predominantly been in the areas of sociology of health and health promotion. He has done discourse analysis, theoretical pieces, but also intervention and collaborative studies. He's specifically interested in social inequalities and power in society.

Notes

1 The references provided do not necessarily support a certain way to teach. They can also represent a critique towards that particular way.

References

- Andrews, R., & Harlen, W. (2006). Issues in synthesizing research in education. Educational Research, 48(3), 287–299.

- Barker, D., Quennerstedt, M., Johansson, A., & Korp, P. (2020). Physical education teachers and competing obesity discourses: An examination of emerging professional identities. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 1–10.

- Cale, L., & Harris, J. (2013). ‘Every child (of every size) matters’ in physical education! physical education's role in childhood obesity. Sport, Education and Society, 18(4), 433–452.

- Cale, L., Harris, J., & Chen, M. H. (2014). Monitoring health, activity and fitness in physical education: Its current and future state of health. Sport, Education and Society, 19(4), 376–397.

- Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143.

- Culler, J. (1992). In defence of overinterpretation. In S. Collini (Ed.), Interpretation and overinterpretation (pp. 109–123). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Demetriou, Y., Gillison, F., & McKenzie, T. L. (2017). After-school physical activity interventions on child and adolescent physical activity and health: A review of reviews. Advances in Physical Education, 7(2), 191–215.

- Doolittle, S. A., Rukavina, P. B., Li, W., Manson, M., & Beale, A. (2016). Middle school physical education teachers’ perspectives on overweight students. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(2), 127–137.

- Evans, J., Rich, E., Davies, B., & Allwood, R. (2008). Education, disordered eating and obesity discourse: Fat fabrications. London: Routledge.

- Gard, M., & Wright, J. (2001). Managing uncertainty: Obesity discourses and physical education in a risk society. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 20(6), 535–549.

- Greenhalgh, T., Robert, B., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., Kyriakidou, O., & Peacock, R. (2005). Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A metanarrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 417–430.

- Kahan, D., & McKenzie, T. L. (2015). The potential and reality of physical education in controlling overweight and obesity. American Journal of Public Health, 105(4), 653–659.

- Lee, E. Y., & Yoon, K. H. (2018). Epidemic obesity in children and adolescents: Risk factors and prevention. Frontiers of Medicine, 12(6), 658–666.

- Lynagh, M., Cliff, K., & Morgan, P. J. (2015). Attitudes and beliefs of nonspecialist and specialist trainee health and physical education teachers toward obese children: Evidence for “anti-fat” bias. Journal of School Health, 85(9), 595–603.

- Marston, C., & King, E. (2006). Factors that shape young people's sexual behaviour: A systematic review. The Lancet, 368(9547), 1581–1586.

- McKenzie, T. L., & Lounsbery, M. A. (2014). The pill not taken: Revisiting physical education teacher effectiveness in a public health context. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(3), 287–292.

- Nerud, K., & Steiner, M. (2019). Training staff of afterschool arograms on healthy eating and physical activity: Opportunity to reduce childhood obesity. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 5(4), 230–232.

- Pate, R. R., O'Neill, J. R., & McIver, K. L. (2011). Physical activity and health: Does physical education matter? Quest, 63(1), 19–35.

- Pausé, C. (2019). (Can we) get together? Fat kids and physical education. Health Education Journal, 78(6), 662–669.

- Pluim, C., & Gard, M. (2016). Parents as pawns in fitnessgram’s war on obesity. In S. Dagkas & L. Burrows (eds.), Families, young people, physical activity and health (pp. 71–83). London: Routledge.

- Powell, D., & Fitzpatrick, K. (2015). ‘Getting fit basically just means, like, nonfat’: Children's lessons in fitness and fatness. Sport, Education and Society, 20(4), 463–484.

- Quennerstedt, A. (2011). The construction of children's rights in education–a research synthesis. The International Journal of Children's Rights, 19(4), 661–678.

- Quennerstedt, M. (2019). Physical education and the art of teaching: Transformative learning and teaching in physical education and sports pedagogy. Sport, Education and Society, 24(6), 611–623.

- Quennerstedt, M., & Larsson, H. (2015). Learning movement cultures in physical education practice. Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 565–572.

- Rich, E., De Pian, L., & Francombe-Webb, J. (2015). Physical cultures of stigmatisation: Health policy & social class. Sociological Research Online, 20(2), 1–14.

- Streeton, R., Cooke, M., & Campbell, J. (2004). Researching the researchers: Using a snowballing technique. Nurse Researcher, 12(1), 35–46.

- Sykes, H., & McPhail, D. (2008). Unbearable lessons: Contesting fat phobia in physical education. Sociology of Sport Journal, 25, 66–96.

- Tinning, R. (2015). ‘I don't read fiction’: Academic discourse and the relationship between health and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 20(6), 710–721.

- Walseth, K., & Tidslevold, T. (2020). Young women’s constructions of valued bodies: Healthy, athletic, beautiful and dieting bodies. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 55(6), 703–725.

- Webb, L., & Quennerstedt, M. (2010). Risky bodies: Health surveillance and teachers’ embodiment of health. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(7), 785–802.

- Wetherell, M., Taylor, S., & Yates, S. J. (2001). Discourse theory and practice. London: SAGE.

- Whittemore, R. (2005). Combining evidence in nursing research: Methods and implications. Nursing Research, 54(1), 56–62.

- Wolfenden, L., Ezzati, M., Larijani, B., & Dietz, W. (2019). The challenge for global health systems in preventing and managing obesity. Obesity Reviews, 20, 185–193.

Appendix A – Articles used in the review

- Bott, T. S., & Mitchell, M. (2015). Battling obesity with quality elementary physical education: From exposure to competence. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 86(6), 24-28.

- Butz, J. V. (2018). Applications for Constructivist Teaching in Physical Education. Strategies, 31(4), 12-18.

- Burrows, L., & McCormack, J. (2012). Teachers' talk about health, self and the student ‘body’. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 33(5), 729-744.

- Cale, L., & Harris, J. (2013). ‘Every child (of every size) matters’ in physical education! Physical education's role in childhood obesity. Sport, Education and Society, 18(4), 433-452.

- Clark, S. L. (2018). Fitness, fatness and healthism discourse: girls constructing ‘healthy’ identities in school. Gender and Education, 30(4), 477-493.

- Cliff, K., & Wright, J. (2010). Confusing and contradictory: Considering obesity discourse and eating disorders as they shape body pedagogies in HPE. Sport, Education and Society, 15(2), 221-233.

- Doolittle, S. A., Rukavina, P. B., Li, W., Manson, M., & Beale, A. (2016). Middle school physical education teachers’ perspectives on overweight students. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(2), 127-137.

- Evans, J., Rich, E., & Davies, B. (2004). The emperor’s new clothes: Fat, thin, and overweight. The social fabrication of risk and ill health. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 23(4), 372-391.

- Fitzpatrick, K. (2011). Obesity, Health and Physical Education: a Bourdieuean perspective. Policy Futures in Education, 9, 353-366.

- Gard, M. (2008). Producing little decision makers and goal setters in the age of the obesity crisis. Quest, 60(4), 488-502.

- Gard, M. (2011). A meditation in which consideration is given to the past and future engagement of social science generally and critical physical education and sports scholarship in particular with various scientific debates, including the so-called ‘obesity epidemic’ and contemporary manifestations of biological determinism. Sport, Education and Society, 16(3), 399-412.

- Gard, M., & Wright, J. (2001). Managing uncertainty: Obesity discourses and physical education in a risk society. Studies in philosophy and education, 20(6), 535-549.

- Garrett, R., & Wrench, A. (2012). ‘Society has taught us to judge’: Cultures of the body in teacher education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2), 111-126.

- Goodyear, V. A., Kerner, C., & Quennerstedt, M. (2019). Young people’s uses of wearable healthy lifestyle technologies; surveillance, self-surveillance and resistance. Sport, Education and Society, 24(3), 212-225.

- Gray, S., MacIsaac, S., & Harvey, W. J. (2018). A comparative study of Canadian and Scottish students’ perspectives on health, the body and the physical education curriculum: the challenge of ‘doing’critical. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 9(1), 22-42.

- Greenleaf, C., & Weiller, K. (2005). Perceptions of youth obesity among physical educators. Social Psychology of Education, 8(4), 407-423.

- Kirk, D. (2006). The ‘obesity crisis’ and school physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 11(2), 121-133.

- Landi, D. (2018). Toward a queer inclusive physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(1), 1-15.

- Lee, J., & Macdonald, D. (2010). ‘Are they just checking our obesity or what?’ The healthism discourse and rural young women. Sport, Education and Society, 15(2), 203-219.

- Li, H., Li, W., Zhao, Q., & Li, M. (2017). Including overweight and obese students in physical education: an urgent need and effective teaching strategies. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 88(5), 33-38.

- Li, W., & Rukavina, P. (2012). The nature, occurring contexts, and psychological implications of weight-related teasing in urban physical education programs. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 83(2), 308-317.

- Li, W., & Rukavina, P. (2012). Including overweight or obese students in physical education: A social ecological constraint model. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 83(4), 570-578.

- Li, W., Rukavina, P., & Wright, P. (2012). Coping against weight-related teasing among adolescents perceived to be overweight or obese in urban physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 31(2), 182-199.

- Lynagh, M., Cliff, K., & Morgan, P. J. (2015). Attitudes and Beliefs of Nonspecialist and Specialist Trainee Health and Physical Education Teachers Toward Obese Children: Evidence for “Anti-Fat” Bias. Journal of School Health, 85(9), 595-603.

- Martínez-López, E. J., Zamora-Aguilera, N., Grao-Cruces, A., & De la Torre-Cruz, M. J. (2017). The association between Spanish physical education teachers’ self-efficacy expectations and their attitudes toward overweight and obese students. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 36(2), 220-231.

- Pausé, C. (2019). (Can we) get together? Fat kids and physical education. Health Education Journal, 78(6), 662-669.

- Petherick, L. (2013). Producing the young biocitizen: secondary school students' negotiation of learning in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 18(6), 711-730.

- Petrie, K., & Clarkin-Phillips, J. (2018). ‘Physical education’ in early childhood education: Implications for primary school curricula. European Physical Education Review, 24(4), 503-519.

- Powell, D., & Fitzpatrick, K. (2015). ‘Getting fit basically just means, like, nonfat’: children's lessons in fitness and fatness. Sport, Education and Society, 20(4), 463-484.

- Pringle, R., & Pringle, D. (2012). Competing obesity discourses and critical challenges for health and physical educators. Sport, education and society, 17(2), 143-161.

- Prusak, K., Graser, S. V., Pennington, T., Zanandrea, M., Wilkinson, C., & Hager, R. (2011). A critical look at physical education and what must be done to address obesity issues. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 82(4), 39-46.

- Quennerstedt, M. (2008). Exploring the relation between physical activity and health—a salutogenic approach to physical education. Sport, education and society, 13(3), 267-283.

- Rich, E., De Pian, L., & Francombe-Webb, J. (2015). Physical cultures of stigmatisation: Health policy & social class. Sociological Research Online, 20(2), 1-14.

- Rukavina, P. B., & Doolittle, S. A. (2016). Fostering inclusion and positive physical education experiences for overweight and obese students. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 87(4), 36-45.

- Rukavina, P. B., Doolittle, S., Li, W., Manson, M., & Beale, A. (2015). Middle school teachers’ strategies for including overweight students in skill and fitness instruction. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 34(1), 93-118.

- Rukavina, P., Doolittle, S., Li, W., Beale-Tawfeeq, A., & Manson, M. (2019). Teachers' Perspectives on Creating an Inclusive Climate in Middle School Physical Education for Overweight Students. Journal of School Health, 89(6), 476-484.

- Stewart, G. L., & Webster, C. A. (2018). The Role of Physical Educators in Addressing the Needs of Students Who Are Overweight and Obese. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 89(1), 30-34.

- Sykes, H. & McPhail, D. (2008). Unbearable Lessons: Contesting Fat Phobia in Physical Education. Sociology of Sport Journal, 25, 66-96.

- Tingstrom, C. A. (2015). Addressing the needs of overweight students in elementary physical education: creating an environment of care and success. Strategies, 28(1), 8-12.

- Trout, J., & Graber, K. C. (2009). Perceptions of overweight students concerning their experiences in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 28(3), 272-292.

- Wallhead, T. (2007). Teaching K-12 students to combat obesity. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 78(8), 26-28.

- Varea, V., & Underwood, M. (2016). ‘You are just an idiot for not doing any physical activity right now’ Pre-service Health and Physical Education teachers’ constructions of fatness. European Physical Education Review, 22(4), 465-478.

- Welch, R., & Wright, J. (2011). Tracing discourses of health and the body: Exploring pre-service primary teachers' constructions of ‘healthy’ bodies. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 199-210.

- Wiltshire, G., Lee, J., & Evans, J. (2017). ‘You don’t want to stand out as the bigger one’: exploring how PE and school sport participation is influenced by pupils and their peers. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(5), 548-561.

- Wrynn, A. M. (2011). Beyond the standard measures: Physical education's impact on the dialogue about obesity in the 20th century. Quest, 63(2), 161-178.