ABSTRACT

The overall aim of this paper is to introduce a new way of analysing and understanding the framing and potential of Physical Education and Health (PEH) practice. Focusing on subject-specific literacy, which is defined as an abstract and generalising language, containing words and concepts typical for a specific subject [Nestlog, B. E. (2019). Ämnesspråk – en fråga om innehåll, röster och strukturer i ämnestexter [subject-specific literacy – a question about content, voices and structures in subject specific texts]. HumaNetten Nr, 42, 9–30], we, in this paper, particularly stress and reiterate the need for a verbalised subject-specific literacy of PEH [Larsson, H., & Nyberg, G. (2017). ‘It doesn’t matter how they move really, as long as they move.’ Physical education teachers on developing their students’ movement capabilities. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(2), 137–149; Wright, J. (2000). Bodies, meanings and movement: A comparison of the language of a physical education lesson and a feldenkrais movement class. Sport, Education and Society, 5(1), 35–49]. Since the subject-specific literacy of a subject constitutes a framework for the subject regarding content, pedagogy and assessment, we argue that linguistic analysis is crucial when it comes to better our understanding of PEH practice. Drawing on a linguistic analysis framework, the four most common textbooks used in Swedish PEH practice are analysed. The analysis of the PEH textbooks involves: defining the characteristics of the core concepts, identifying the semantic relations between the concepts, creating hierarchical systems of concepts and exploring what appears as the core content of the PEH subject. The results highlight how explicit ways of talking about all areas of the PEH curriculum are missing [Wright, 2000]. In particular, the results show that concepts primarily relating to ‘sports’ dominate in comparison to ‘health’, and that health content is permeated by a biomedical perspective, which is mirrored in the subject-specific literacy related to it. In addition, the concepts related to sports are specific, often physically palpable and denote dynamic activities, such as interval training, reps [repetitions], sets, HRmax, and static strength, whereas concepts related to health are instead abstract and static.

Introduction

In this paper, we argue that the issue of language is crucial in a school subject such as Physical Education and Health (PEH). Language is needed to convey and discuss pedagogical approaches in PEH as well as in PEH research. However, language is also needed to assist teachers in their professional work, so that they can reflect on, develop and consciously communicate the aims of their teaching practice (cf. Wright, Citation1997, Citation2000) through words and teaching actions. This paper puts emphasis on the need of language and the presence of core concepts and ‘subject-specific literacy’ in PEH. Subject-specific literacy is to be understood here as core concepts forming the language of the PEH practice (cf. Clarke, Citation1992).Footnote1

Research has pinpointed several issues of concern in PEH, like marginalising aspects of gender (Redelius, Fagrell, & Larsson, Citation2009; van Amsterdam, Knoppers, Claringbould, & Jongmans, Citation2012), the promotion of masculinity ideals (Campbell, Gray, Kelly, & MacIsaac, Citation2018; Gerdin & Larsson, Citation2018; van Doodewaard & Knoppers, Citation2018) and the fact that sports are dominant in PEH (e.g. Campbell et al., Citation2018; Walseth, Aartun, & Engelsrud, Citation2017). Some researchers (e.g. Clarke, Citation1992; Larsson & Karlefors, Citation2015; Larsson & Redelius, Citation2008; Nyberg & Larsson, Citation2014; Schenker, Citation2019) highlight the role of language in PEH, however not from a linguistic perspective. It is our belief that a lack of a (strong) subject-specific literacy of PEH seemingly affects the content of the teachers’ practices in class, which, in turn, affects their ability to assess the students’ accomplishments transparently (for instance, see Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010; Svennberg, Meckbach, & Redelius, Citation2014; Wiker, Citation2017). In the end, subject-specific literacy is crucial in strengthening or inhibiting teaching discourses. Even if more studies are needed to more specifically shed light on how subject-specific literacy relates to discourses in PEH, we argue from a cross-disciplinary perspective that examinations of the subject-specific literacy may provide a piece of the puzzle to understand some of the ongoing problematic issues in PEH.

The overall aim of this study is to introduce a new and fruitful way to analyse and understand the framing and potential of PEH practice. Focusing on subject-specific literacy, we stress the need of a verbalised subject-specific literacy of PEH, not least while a wealth of previous research highlights such a need (for instance, see Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010; Larsson & Nyberg, Citation2017; Svennberg et al., Citation2014; Wright, Citation2000). By extension, the results can be drawn on in discussions about PEH as a school subject as well as about which implications the subject-specific literacy have on students who are educated and assessed in the subject. An additional purpose of the larger project, which this study is part of, is to investigate the implications of a potentially dominating subject-specific literacy when it comes to issues of inclusion and exclusion (cf. Schenker, Citation2019).

Well aware of many exceptions in PEH teaching practice, research continues to demonstrate how the PEH subject is dominated by a competitive sport logic and traditional masculine values (Campbell et al., Citation2018; Svendsen & Svendsen, Citation2016), where the students primarily become ‘physically educated'. Since we have not come across previous research that describes the specific aspects of subject-specific literacy in PEH in depth, this paper can be seen as an initial contribution and a first attempt to describe this specific type of literacy.

Background and clarification of key concepts

Being literate means that an individual can interact and communicate, and it is often defined as activities based on written language, i.e. producing different types of texts (Clarke, Citation1992; Nestlog, Citation2019). In a PEH context, as in any school subject context, this includes the proper use of core words and concepts that the subject is constituted of: the subject-specific literacy. As the academisation of the teaching profession increases, the requirement of explicit and transparent subject-specific literacy increases (Hipkiss, Citation2014; Nestlog, Citation2019; Ribeck, Citation2015). The subject-specific literacy sets the framework for the subject-specific knowledge, and, furthermore, is a tool that assists (PEH) teachers in communicating the content of the subject. Generally, subject-specific literacy includes, for instance, the expressing, interpreting, and understanding of concepts, facts, and crucial ideas in written and spoken texts. Subject-specific literacy is described as an abstract and generalising language, containing words and concepts typical for a specific subject (Nestlog, Citation2019).

Our study provides a new and linguistic perspective on the subject-specific literacy, and, consequently, the subject-specific knowledge of PEH, which has previously been discussed from other perspectives by, for instance, Ekberg (Citation2016, Citation2020), Lynch and Soukup (Citation2016), and Robinson, Randall, and Barrett (Citation2018), Wallian and Chang (Citation2007) and Penney, Brooker, Hay, and Gillespie (Citation2009). For example, Clarke (Citation1992), Penney et al. (Citation2009), and Ekberg (Citation2016, Citation2020) have focused on curricula and syllabi, and the analyses performed can be classified as discourse oriented, where Bernstein’s theories are applied to interpret the results. In addition, a semi-constructivist approach was adopted by Wallian and Chang (Citation2007). Common for these studies, is a ‘top-bottom' perspective, which starts at the discourse level. In contrast, our purely semantic study is ‘bottom-up', where we start with a strictly linguistic study of concepts and then discuss the PEH discourse against this background.

In the Swedish school curriculum for PEH (‘idrott och hälsa’), the teaching of ‘health’ and ‘physical education’ is integrated. The teachers are expected to teach PEH simultaneously. Through the teaching practices in PEH, students should develop their knowledge of how the body works and of health-promoting factors. As such, the school subject PEH has a dual purpose. In this paper, we use ‘sports’ as the translation of idrott, even though the concept idrott is broader than the international concept of sports (Peterson & Schenker, Citation2018). The Swedish word idrott means nearly the same as sports, a concept that is also part of the Swedish vocabulary. There is no answer clarifying how to distinguish them from one another. Usually, in international PEH research literature, published by Swedish researchers, idrott is translated as ‘physical education’.

Moreover, the concept hälsa (‘health’) can contain different dimensions, such as social, psychological, and physical health (cf. Quennerstedt, Citation2008). Even if there is an explicit health concern in PEH, the subject seems to reproduce current health discourses uncritically (McCuaig & Tinning, Citation2010; Schenker, Citation2018; Tinning & Glasby, Citation2002; Webb, Quennerstedt, & Öhman, Citation2008; also, cf. Lynch & Soukup, Citation2016). Svendsen (Citation2014), who studied teaching materials, curricula, informational texts and debates about education developed for health education in the Danish Primary School, concluded that the assumption that physical activity per se promotes health, the more the better, is well represented in the material. From this perspective, physical activity is essential to prevent future health risks. ‘Health’ in PEH is not an easy task for teachers to handle, others have also problematised the health discourse in Health education (cf. Evans, Citation2003; Gard & Wright, Citation2001; Parkinson & Burrows, Citation2019; Webb & Quennerstedt, Citation2010; Wright, Burrows, & Rich, Citation2012). In Sweden, a political agenda focusing on public health underpins the school subject PEH. There is an explicit focus on ‘Health and lifestyle’ and ‘Outdoor life and activities’. Health can be connected to equality, and that is according to WHO something that needs to permeate all societal activities (WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Citation2008). A public health agenda aims to strengthen the wellbeing of a population or a specific group of people, e.g. by education. However, despite this public health agenda, several Swedish evaluations show that PEH is dominated by a focus on ball games and physical training (The Swedish Schools Inspectorate, Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2018).

A subject-specific language of PEH – a professional language

The mutual relation between thought and language can be regarded as well-known (Chomsky, Citation2005; Linell, Citation2009). With a subject-specific literacy, researchers, teachers, evaluators and students would get the tools to talk about, discuss, and explore the school subject as part of the public health agenda and thereby to a greater extent be able to enrich PEH with other perspectives than merely skill acquisition, a performance approach and a competitive sports approach (c.f. Wright, Citation2000). The abstract and generalising language that constitutes subject-specific literacy contains words and concepts typical for a specific subject. Examples of such core content, which is also described as part of the curriculum of the subject (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011), are words and concepts that the students can use to express their own ‘experiences and outcomes of different physical activities and forms of training'. In a professional setting, the subject-specific language of PEH needs to be transparent and assistive in communicating expectations on students’ learning in the school subject. For instance, after having examined how ‘ability’ is conceptualised, configured and produced in movement assessment tools produced in six different countries, Tidén, Redelius, and Lundvall (Citation2017) conclude that the concept ‘movement ability’ is far from neutral and that the tools benefit those who have experience of traditional sports and are physically mature. In line with this, assessment in PEH tends to focus on dimensions such as motor skills, fitness and team games (Borghouts, Slingerland, & Haerens, Citation2017; Dalen et al., Citation2017; cf. Penney et al., Citation2009).

Nevertheless, the proficiencies of and within the school subject PEH are difficult to identify and describe. For instance, research has shown that students experience that they do not receive enough information from their teachers regarding what is expected from them (Redelius, Quennerstedt, & Öhman, Citation2015), which is also problematised by Redelius and Hay (Citation2009, Citation2012). In line with this, Kroon et al. (Citation2016) stresses that the Swedish curricula and syllabus of PEH from 2011 are difficult to interpret, not least the concepts, key values, and words expressing progression. Swedish researchers show that PEH teachers take into account the students’ motivation, self-confidence, and their skills related to leadership and athletic abilities in the assessment (Svennberg, Meckbach, & Redelius, Citation2018). Even if this stance is not supported by the Swedish curriculum, measurable accomplishments, often in the shape of athletic results, have been shown to be required if the students are to obtain the highest grades in PEH (Redelius et al., Citation2009). The teachers sometimes also refer to internalised grading. This means that teachers verbally have difficulties explaining what the students ought to learn, which puts the transparency of the grading process at risk (Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010; Svennberg et al., Citation2014). Assessed cumulatively, the research pinpoints a lack of transparency regarding the teaching practice of PEH. Our cross-disciplinary and descriptive study can be seen as a first step towards a visualisation of the existing language of PEH and how this language is expressed in common Swedish PEH textbooks, aiming at introducing a new way to analyse and understand the framing and potential of PEH practice and contributing to an understanding of some of the problematic issues that PEH faces.

Methodology and theoretical framework

To study the language and the use of concepts in PEH, a linguistic analysis of common textbooks used in Swedish PEH teaching practice was conducted (cf. the different types of curriculum studies performed by, for instance, Ekberg, Citation2016, Citation2020; Wallian & Chang, Citation2007; Penney et al., Citation2009). The aim of such analysis was threefold: to define characteristics of the key concepts used in PEH, to identify the semantic relations between these concepts, and to create hierarchical systems of concepts. The linguistic analysis of these PEH textbooks has the potential to reveal what is described as the core content of the school subject. Note that our study is a first step in a linguistic analysis of the subject-specific literacy of Swedish PEH, which, is to be followed up by interviews on which concepts PEH teachers as well as PEH students consider constitute the subject-specific literacy of the subject.

The overall theoretical framework used for the analysis in this study is a semantic analysis of words, groups of words, and concepts (for instance, see Saeed, Citation2016; Zimmermann & Sternefeld Citation2013). In a semantic analysis, the lexicon of a specific subject matter or technical area is studied. The crucial and central words within this area or these areas are arranged in lexical networks, for instance, butterfly, crawl, breaststroke, and backstroke belong to the same lexical network, subcategorised to the individual sport swimming (cf. Saeed, Citation2016). The result from an in-depth study of words would provide a concretion of how the subject-specific literacy of PEH is manifested.

Semantic analyses focus on meaning. The analytical tools used in this study are retrieved from lexical semantics. The purpose of lexical semantics in this study is to illustrate how the meanings of different words are interrelated. In a lexical semantic analysis, the terms ‘concept’ and ‘reference’ are crucial. A concept is defined as a complex mental representation, whereas the reference of a word is the collection concept in which every referent of the word is included (Saeed, Citation2016; Zimmermann & Sternefeld Citation2013), such as a simple word (swimming), a compound (breast stroke), or a phrase (active warming-up). The inherent property of a word, which enables the word – the concept – to limit specific classes of referents, is its intension (Saeed, Citation2016): athletics must contain certain properties that make the word possible to use regarding athletics specifically, but not regarding, for instance, swimming. The word sports includes athletics and swimming – and several other activities – hence, it cannot have the exact same meaning as athletics. This is one crucial starting point in a semantic analysis.

Beyond the intension of a concept, its extension (Saeed, Citation2016; Zimmermann & Sternefeld Citation2013) is relevant. The extension of a concept is represented by the referents included in the specific concept. A word with a wide intension has a narrow extension and the other way around: sports has a narrower intension and a wider extension than athletics, which, correspondingly, has a wider intension and a narrower extension than sports. Furthermore, athletics has a more specified content of meaning, in the sense that it contains more components of meaning than sports. As such, it can be used to refer to a smaller range of referents in reality (in the world, there are many more sports men and sports women than athletes). If there is a difference in the intension of content of two words, there is a difference in their general and specific meaning. This is another crucial starting point in a semantic analysis.

When the concepts are analysed with respect to their intention and extension, they can be arranged in a semantic network (Zimmermann & Sternefeld Citation2013, p. 20) with respect to hyponymy, which is a relation of inclusion. Hyponymy expresses a relation connected to meaning, by means of which one can establish a hierarchy of words that belong to the same hierarchy of concepts (Zimmermann & Sternefeld Citation2013, p. 20; Saeed, Citation2016, p. 65f). Hyponyms are subordinated concepts and hyperonyms are superordinate concepts, i.e. sports is a hyperonym to athletics; in a semantic hierarchy, concepts that are poorer with respect to content but wider with respect to extension, such as sports, are superordinate – hyperonyms – to concepts that are richer with respect to content but poorer with respect to extension, such as athletics, which is a hyponym to sports. Hence, the latter concepts are subordinated – hyponyms. A concept can be a hyperonym to one concept and at the same time a hyponym to another in a semantic hierarchy.

A system of concepts can be one-dimensional or multi-dimensional (Nuopponen & Pilke, Citation2016, p. 35), depending on the criteria used on the first level of division. In a one-dimensional system, the first principle of division is only one, whereas in a multi-dimensional system, several and various principles are assembled. For instance, in a multi-dimensional system focusing on the concept physical activity, there could be (at least) two first principles of division, namely type and form. The concepts relating to type are physical exercise and competitive sports, and concepts relating to form are spontaneous physical exercise and organised physical exercise. These concepts are parallel, i.e. are situated on the same level in the hierarchy of concepts (Nuopponen & Pilke, Citation2016, p. 34). Multi-dimensional systems of concepts are characterised by the fact that the hyponym concepts that relate to the different principles of division are to some extent compatible with each other.

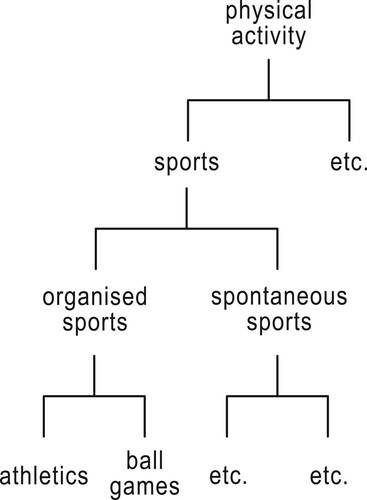

Concepts always constitute one part of a bigger picture, which means that it is impossible to analyse and define a concept without also considering the context in which the concepts appear (Nuopponen & Pilke, Citation2016, p. 17f). For instance, regarding organised sports, it is reasonable to construct a semantic hierarchy where organised sports is a hyponym to sports, which, in turn, is a hyponym to physical activity. Furthermore, organised sports is a hyperonym to, for instance, athletics and ball games. Consequently, the semantic hierarchy of organised sports can be illustrated as in .

The aim of such a constructed semantic hierarchy would not be to present a complete hierarchy, with all potential sub-categories, but instead to subsume the concepts in focus in a hierarchy, in order to see whether they have any natural hyperonyms and/or hyponyms.

In our study, it is reasonable to assume that hyperonyms and/or hyponyms of a concept are sometimes more or less explicitly expressed in the context. For instance, regarding physical activity, it is stated that this is a super-ordinated concept for types of physical body movement, at work or leisure. It is exemplified with, for instance, sports, games and athletics. Consequently, organised sports and other types of sports are hyponyms to this concept in a semantic hierarchy. Furthermore, if physical activity is assumed to be a super-ordinated concept, it cannot be a hyponym to any other concept in the present semantic field.

Several studies concerning different aspects of conceptual systems and hierarchies, as well as the translation of specific terms and concepts from one language to another, have already been conducted (e.g. Kageura, Citation2002; Pilke, Citation2006). However, studies that focus on analysing and arranging concepts in hierarchies, with the specific purpose of comparing the hierarchical level of concepts belonging to different semantic networks, have to the best of our knowledge not been done in previous research.

Our choice to view sports and health as two ‘parts' of PEH might be regarded as an orthodox perspective of how the school subject is constituted. This choice, however, is motivated by a number of factors. Firstly, the subject-specific literacy when it comes to sports is claimed to be strong and suitable to measure sport and training related content (cf. Svendsen & Svendsen, Citation2016), whereas a corresponding way to discuss other areas and the full scope of the PEH curriculum is missing (cf. Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010; Schenker, Citation2018; Svennberg et al., Citation2014; Wright, Citation2000). Hitherto, however, there are no linguistic studies to support or question such a claim. If the aim is to try to verify or falsify this implicitly formulated hypothesis, our point of departure must include a division between sports, on the one hand, and health, on the other. Secondly, a strictly linguistic study of concepts of this type must use the context in order to make the starting point as objective as possible. In our case, the concepts appear and are applied in different sections and chapters in the textbooks, where the content provides explicit clues as to which ‘part' of the subject the concepts belong. This information is a foundation for a semantic analysis: the concepts are not interpreted by us, but they are posited in different contexts in the textbooks, which explicitly consider different aspects – parts – of PE. For instance, when a chapter explicitly focuses on how to optimise training in order to improve performance in different areas – as is the situation in Träningslära – optimera träningen, ‘Training theory – how to optimise training' – the context relates to sports and not to health; there is no health perspective taken into account here. The fact that some concepts appear several times, in different contexts, presumably challenges the division of the subject (which we will further discuss later in the paper) but still, in the textbooks, the concepts appear in their contexts, which is the crucial starting point for a linguistic analysis.

Data and analysis

In our study, we have analysed four Swedish textbooks in PEH (listed as references). According to Swedish publishing companies, these are the most sold textbooks in PEH. The four textbooks contain between ten and twelve chapters, with an obvious overlap of content and a very similar overall structure as well as disposition with respect to, for instance, percentage of pages covering the different areas of the subject’s content and the order between the chapters. In sum, the textbooks display an overall conformity. As is expected, the textbooks cover the core content of the school subject, as it is stated in the national curriculum; in this respect, the textbooks can be considered interchangeable.

In the textbooks, we have analysed concepts that to some extent are highlighted and marked as crucial, for instance with headlines, line-ups with tasks, questions on certain concepts, and definitions of concepts that usually sum up the different chapters and boxes labelled ‘Crucial concepts’ (filled with concepts such as reps, sets and interval training). Regarding concepts that are related to a subject-specific literacy, it is worth noting that only on three occasions the word begrepp (‘concept’) is used, and, additionally the word fackuttryck (‘technical term’) once. One of the uses of begrepp (‘concept’) is found in relation to fysisk aktivitet (‘physical activity’), which is claimed to include the concepts motion (‘physical exercise’), organiserad idrott (‘organised sports’), and spontanidrott (‘spontaneous sport-like activities’). The other uses of begrepp (‘concept’) as well as the use of fackterm (‘technical term’) relate to weight training and pinpoints the concepts reps [repetitioner] (‘repetitions’), set (‘sets’) and fria vikter (‘free weights’).Footnote2

Although we are aware that not all PEH teachers use textbooks, we still regard textbooks as documents which can display different crucial concepts of the subject PEH. Säljö (Citation2014, p. 221) argues that the stronger requirements put on students’ cognitive and communicative skills are due to textbooks and Hipkiss (Citation2014) claims that, at least regarding school subjects like PEH, Music, Art, and Home and Consumer studies, it is in the textbooks that the students get in contact with a subject-specific literacy. In relation to this, Karlsson and Strand (Citation2012, p. 114) claim that textbooks are central and integrated in school, a context that is based on texts and the written language. Hence, the analysis of textbooks is motivated because they, to a varying degree, contain texts, lists of concepts and tasks aimed at defining different concepts. Consequently, it seems reasonable to assume that these concepts could be regarded as parts of a subject-specific literacy of PEH. In addition, it is reasonable to assume that the subject-specific literacy of the school subject PEH, as it is manifested in the textbooks, matches the crucial concepts and core content in the curriculum for, in this study, the Swedish PEH subject (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011).

Results and analysis

As previously pointed out, PEH is a complex subject, and the complexity is further underlined by the fact that the core content, according to the Swedish PEH curriculum, consists of three areas, namely movement, health and lifestyle, and outdoor life and activities. Accordingly, there are different options regarding how to divide the core concepts, i.e. the concepts constituting parts of the subject-specific literacy, into different groups. The Swedish school subject includes both the words idrott (‘sports’) and hälsa (‘health’). The fact that the subject’s name is PEH, together with the fact that this study takes a purely linguistic point of departure, makes us consider a division of the core concepts into concepts primarily relating to sports, to health, or to both categories motivated. Another argument is the fact that health has been included in the subject only for a relatively short period (see e.g. Lundvall & Meckbach, Citation2003), which, in turn, makes it relevant to examine if this is reflected in the core concepts in the textbooks. Furthermore, researchers have pointed out that there is a national as well as an international language for discussing idrott (‘sports’), above all in international contexts. On the other hand, without having performed any linguistic-based studies, others claim that there are differences in the subject-specific literacy that relates to the different parts (see e.g. Redelius et al., Citation2009; Schenker, Citation2018). From a linguistic point of view, the distribution of the concepts over the sports-part and the health-part is interesting and motivated per se, since both concepts can be claimed to be weak, vague, and not precisely defined (regarding semantic vagueness and weakness, see e.g. Holm, Citation2018).

In the subsequent three sections, we present the results of our analysis of the subject-specific literacy in PEH, drawing on the textbooks most used in the school subject. The section is divided into three subsections. In the first subsection, the results of the analysis are presented as semantic networks, providing a quantitative overview of the subject-specific literacy of PEH. In the second subsection, the results are discussed based on semantic hierarchies, providing a qualitative overview of the subject-specific literacy of PEH. The third subsection, finally, summarises the results.

A quantitative overview of the subject-specific literacy in PEH: semantic networks

In order to present an overview of the subject-specific literacy in PEH, the crucial concepts in the textbooks were manually identified via text analyses: all concepts that in some way are highlighted in the textbooks were compiled in one file. Crucial concepts are, for instance, words of content such as training, the multilayer principle, and health, but not formal words such as because and above or common words such as run, present or games. Since the aim was not to compare the different textbooks, but rather to create a set of concepts that constitute the common subject-specific literacy of PEH, there was no need for analysing the four files separately. By using the computer program LIX,Footnote3 the identified concepts were presented as a frequency dictionary, based on their frequency in the empirical material. In order to create a frequency dictionary, concepts consisting of more than one word were formed into one by means of dashes, for instance, dynamic strength was re-written as [dynamic strength], in order to constitute a single unit (a phrase).

The frequency dictionary, based on central concepts in the four textbooks, consists of 420 concepts, varying from five occurrences to one occurrence. illustrates that there are two concepts that appear on five occasions, two other concepts that appear on four occasions, three concepts on three occasions, and onwards. The fact that 330 concepts occur only on one occasion is a result per se, and indicates a vague subject-specific literacy.

Table 1. A frequency dictionary for concepts in the subject-specific literacy in PEH.

The number of concepts with 3–5 occurrences in the textbooks are 37 (2 + 2+33), whereas 53 concepts have two occurrences. Since the aim of this section is to give a brief, descriptive overview of the concepts used in the empiric material, in the next step, the 37 concepts with 3–5 occurrences were divided into three groups. The analysis showed that the identified concepts are related to sports, to health or to both sports and health, hence the concepts could be part of either the sports area or the health area, or they could in some cases overlap. Examples of concepts that relate to both sports and health are energy balance, carbohydrates, mental training, (physical) condition, strength, and coordination. As previously pointed out, the fact that these concepts relate to sports as well as health is obvious from the context in the textbooks, where they appear in at least two separate chapters and sections, which, in turn, have different content and provide information about different aspects of PEH.

The result of the number of concepts with 3–5 occurrences in the textbooks is presented in : 59% of the 37 concepts relate to sports, 22% to health, and 19% to both parts.

Table 2. Concepts that occur 3–5 times in the material, related to the different parts of the subject.

When the 53 concepts with two occurrences each are divided into the corresponding categories, the result is as shown in : 43% of the concepts relate to sports, 13% to health, and 43% to both parts.

Table 3. Concepts that occur two times in the material, related to the different parts of the subject.

From , concepts relating to sports are greater in occurrence than concepts relating to health. Based on the results, one can claim that the subject-specific literacy in the school subject PEH related to sports is more visible and has more space than the corresponding subject-specific literacy relating to health. Subject-specific literacy related to health is not absent or missing, but it is less prominent.

A qualitative overview of the subject-specific literacy in PEH: semantic hierarchies

The results so far show that the subject-specific literacy relating to sports is more visible and extensive. This, however, does not say anything about the subject-specific literacy relating to the two parts being strong, vague, or unprecise. In order to study the specificity of the concepts, it seems reasonable to analyse the 22 concepts with three or more occurrences relating to sports from as well as the 16 concepts relating to health (with two and three or more occurrences, and ). If only concepts with three or more occurrences relating to health were analysed, the number of concepts relating to each part would not be equal. The fact that concepts with two occurrences need to be considered, however, stresses the result in the study so far: concepts relating to health are more diversified. The 22 concepts relating to sports are listed in the left column in , and the 16 relating to health in the right column. Concepts that relate to the same theme or semantic sub-category are grouped together.

Table 4. The concepts chosen for the semantic analysis.

Firstly, the concepts relating to health are easily divided into different sub-categories in a way that has no equivalent in the concepts relating to sports. The sub-categories can be categorised as in .

Table 5. Concepts relating to hälsa ‘health’ in sub-categories.

If the nine concepts listed in were not considered, only seven concepts would constitute the subject-specific literacy of health: health, physical activity, physical exercise, negative stress, positive stress, ergonomics, and CPR, heart and lung rescue. Furthermore, one could argue that HLR belongs to the concepts related to ill health. The distribution of concepts over different sub-categories indicates that concepts relating to health are a bit ‘sprawling' with respect to content.

Secondly, almost all concepts relating to sports are, on the contrary, connected; except for type of muscle fibre, seemingly all concepts are part of the same semantic network and constitute parts of the same semantic hierarchy. For instance, the concept physical activity is a hyperonym to sports, which, is a hyperonym to competitive sports and physical exercise. The concept competitive sports, in turn, is a hyperonym to elite sports. Hence, competitive sports, physical exercise and first and foremost elite sports appear very low in the semantic hierarchy, which means that their intension is wide and their extension is narrow. Consequently, their meaning is strongly specified and specific. Since all concepts here are hyponyms, the concepts are characterised by specificity.

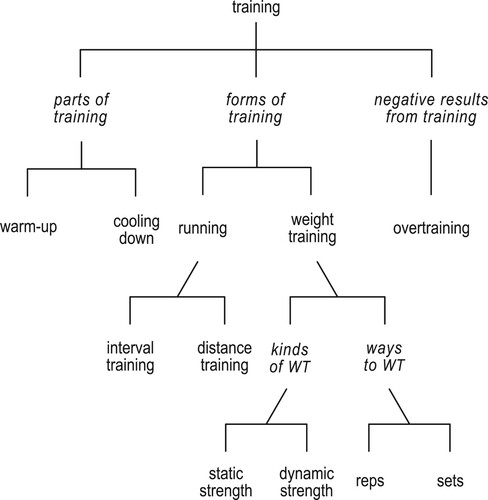

Furthermore, physical training could be linked to the semantic hierarchy suggested above via sports, if the hierarchy is organised multi-dimensionally. As previously presented, the multi-dimensional system is the result of various principles of division for the first division of the concept sports, where training would be considered a crucial part of sports, whereas competitive sports and leisure sports would be crucial forms of sports and overtraining a negative result of sports. In the multi-dimensional system, all concepts are specified even further, and, additionally, more concepts can be linked together. In the multi-dimensional semantic hierarchy, several concepts, that are hyponyms to training, can be arranged as in .

Drawing on the multi-dimensionality of the semantic hierarchy, the concept ability to perform also becomes part of the hierarchical system, as a hyperonym to oxygen consumption, which, in turn, is a hyperonym to oxygen debt’ and asphyxia, at a parallel level in the hierarchy.

Summary of the results

The results of the study show that there is a difference in two aspects between the concepts relating to sports and the ones relating to health. Firstly, considerably more concepts relate unambiguously to sports; hence, there is a quantitative difference between the two parts of the subject regarding the subject-specific literacy. This result is prominent in the textbooks. In addition, the concepts that relate to health clearly represent different and various areas, such as health in relation to ill health/illness or outdoor life. Furthermore, the concepts relating to health can seemingly be part of a subject-specific literacy of other school subjects, for instance, biology, geography, and social sciences. The situation is not the same regarding concepts relating to sports; an exception is the concept type of muscle fibres, which obviously can be found in biology as well. The results state that there are no strong connections between the different concepts included in the semantic network.

Secondly, there is a difference in intension and extension between the concepts relating to the two parts of the subject; hence, there is a qualitative difference between the parts of the subject regarding the subject-specific literacy. To some extent generalised, concepts relating to sports display a wider intension and a narrower extension. As a result, they have a more specific content of meaning, contain more components of meaning and are to a greater extent hyponyms, which is obvious from their position further down in a semantic hierarchy. Translated into the semantic scale, this means that there are more concepts with a specific meaning connected to sports, whereas the concepts connected to health have a more general meaning. Correspondingly, concepts related to health are to a greater extent hyperonyms, have a less specified content of meaning and contain less components of meaning. The greater specificity of the concepts relating to sports is visible since the concepts relating to sports are graphically longer. The length of a word corresponds to its specificity (Björnsson, Citation1968): graphically longer phrases and compounds like active warming-up, strength with respect to endurance, and oxygen consumption are more specified than the shorter ergonomics, rhythm, and negative stress.

In addition, the difference in specificity is obvious also with respect to the concepts that relate both to sports and to health, i.e. where the context of the textbook and the sections where they appear places them in both categories: for instance, energy balance, carbohydrates, mental training, and strength are hyperonyms in both cases. When the concepts relate to sports, they constitute the top of a semantic network, with specified hyponyms below (for instance, strength is a hyperonym to dynamic strength and static strength). On the other hand, when the same concepts relate to health, there are no sub-categories nor any concepts lower down in any semantic hierarchy. The context in which the concepts appear concerns, on one hand, consumption in relation to performance (energy balance and carbohydrates), a competitive mindset (mental training) and weight training in order to build specific muscles (strength), and, on the other, a healthy general food consumption (energy balance and carbohydrates), relaxation (mental training) and ergonomics (strength).

Furthermore, the concepts relating to idrott (‘sports’) denote dynamic activities, i.e. acts and activities that people do and perform. This can be exemplified with the prominent use of concepts relating to competitive sports, where training methods, physical strength, and physical endurance are easily translated into something that can be performed. These concepts are ‘physical' and relate to activities, which stresses their concreteness, compared to the concepts relating to hälsa (‘health’), which are more abstract.

Discussion

As previously pointed out, the core concepts in the four textbooks were categorised as relating to sports, to health, or to both ‘parts', based on the context in which they appeared. The division was motivated by the fact that the subject-specific literacy relating to sports is claimed to be strong, whereas there is no corresponding literacy for discussions of all areas of the PEH curriculum (cf. Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010; Schenker, Citation2018; Svendsen & Svendsen, Citation2016; Svennberg et al., Citation2014; Wright, Citation2000); this claim is however not verified in any linguistic studies. Another motivation was the fact a strictly linguistic study of concepts must take into account the context in which they appear in order to make the starting point as objective as possible.

In comparison to ‘health’, the results show that concepts relating to ‘sports’ dominate and these concepts, with one exception, are related to one another. They are also part of an understanding in which the bodies are understood as objects and where the movements are an instrumental outcome of practice. To a great extent, this study confirms some of the previous critical research on problematic issues in PEH: there is a strong subject-specific literacy when it comes to sports, which indicates a language suitable for a measurable sport and training related content in PEH (cf. Svendsen & Svendsen, Citation2016). The pattern indicates that the concepts relating to sports are easier for a teacher to teach and, correspondingly, easier for a student to understand. In addition, there is another crucial difference between the two parts: sports is a phenomenon per se and exists outside our proper selves, whereas health can be a subjective element closely connected to our own lives and identities (Quennerstedt, Citation2008; Schenker, Citation2018).

Thus, the subject-specific literacy relating to sports is more accepted and connected to the globally accepted sports language that, for instance, enables national and international sports competitions. This language has its origin in natural sciences; athletes share the same overall language in the specific context of competition. Additionally, tools for testing are common in the material, and since research indicates that they are not ‘neutral', combined with a dominant natural sciences perspective, students who have no experience of traditional sports and are not physically mature will most likely be marginalised in such teaching practices (cf. Tidén et al., Citation2017). The same goes for those not adhering to traditional masculinity (cf. Campbell et al., Citation2018; Gerdin & Larsson, Citation2018; Redelius et al., Citation2009; van Amsterdam et al., Citation2012).

The current health discourses are also reproduced uncritically in the textbooks. When the topic is health, the subjects identified in this study are usually considered delicate, and from the start difficult to ‘objectify'. However, health is especially described in relation to human illness, indicating a biomedical health discourse (see ). In turn, this means that there is a focus on risk-behaviours (cf. Evans, Citation2003; Gard & Wright, Citation2001; Parkinson & Burrows, Citation2019; Webb & Quennerstedt, Citation2010; Wright et al., Citation2012). In fact, the pathogenic risk-perspective (Quennerstedt, Citation2008) is the only health perspective that is consistent in the results. The subject-specific literacy, when it comes to health, leaves the assessment of the students’ skills and performances uncertain and subjective on the one hand, and gives rise to a great variation of the content of the subject, on the other.

Moreover, the relation between sports and health can be problematised further. It is reasonable to claim that concepts such as interval training, HR max, oxygen consumption, and type of muscle fibre, which according to the context of the textbooks relate to sports, do not unambiguously mirror ‘pure' sports but stem from physiology and related natural sciences disciplines. The concepts are certainly used in sports, but, outside the textbooks, they are also used within biomedical perspectives of health; in the textbooks, as pointed out, they appear only in relation to the sports parts. Presumably, these concepts remain common in PEH practice because they work well in sports as well as in the biomedical health field. From this point of view, what is missing in PEH is not a health perspective more generally, with an associated subject-specific literacy. Rather, what is missing are alternatives to the biomedical perspective – with an associated subject-specific literacy – which can offer teachers and students concepts to be used in discussions of experiences of, for instance, physical activities and prevailing norms and values from different perspectives.

As Nestlog (Citation2019, p. 22) argues, the subject-specific literacy of a subject must be explicit in class for the students to be able to develop broad and deep knowledge of the subject and become members of the practice of the subject. As a consequence, with a weak subject-specific literacy the core words and concepts that constitute the content of the subject are not introduced, which, in turn, results in a focus on different contents of the subject in different classes. A situation where the subject-specific literacy is strong when it concerns competitive sports would seemingly be advantageous for students who take part in sports activities and competitions outside school. This would exclude students who are physically active to a lesser extent or not at all. Consequently, a weak subject-specific literacy with respect to health – with the exception of the biomedical discourse – and outdoor education results in a range of different and various interpretations, where the content of the subject and the degree of inclusion becomes a matter for the individual teacher. When there exists an accepted subject-specific literacy, for instance, the language of the global and international competitive, elite sports, the understanding of the culture and the expectations of this specific culture is more easily achieved.

The results of our study can explain why students are not satisfied with the information regarding what is expected from them (Redelius & Hay, Citation2009, Citation2012; Redelius et al., Citation2015). Because of PEH’s weak health-specific literacy, we argue in line with Nestlog (Citation2019) that there is a risk that the same health-related content is not examined in all classes, rendering an objective assessment impossible. Ribeck (Citation2015) stresses the connection between an objective assessment of a student’s skill in a subject and a strictly defined subject-specific literacy of a subject; if there is no subject-specific literacy, there is no common agenda stating which subject-specific content that is to be taught. In this respect, Ribeck’s (Citation2015) reasoning is in line with Nestlog’s (Citation2019). Consequently, the content of PEH, just like any other school subject, needs to be verbalised in order to establish a common ground for discussions in class (Lundin & Schenker, Citation2018a, Citation2018b), as well as for assessment.

Conclusion

To improve equality and equity in schools, the Swedish government has put a special focus on linguistic and communicative qualities. These processes affect PEH in a direction where the PEH’s subject-specific literacy has to be strengthened; our study has emphasised a need for a subject-specific language. The study has shown that although there exists a subject-specific language in PEH textbooks to some extent, the prevailing language does not match the current PEH curriculum; in the textbooks, a focus on concepts belonging to the natural sciences dominates, which works well within sports and the biomedical health field, but not within a general health perspective. For all students, including newly immigrated students, as well as students grown up in Sweden, it is crucial that the subject-specific literacy includes and even stresses concepts related to health, which, by extension, is also related to the school subject PEH and the public health agenda. From this perspective, every child and youth should have the same right to an equivalent education and receive the necessary support to enable them to participate and achieve the goals of education (Schenker, Citation2019).

Wright (Citation2000) problematises the one-sided traditional physical education approach, where bodies are understood as objects and movements are an instrumental outcome of practice, and argues that the power of scientism and the commitment to a performance approach focused on skill acquisition marginalises other forms of movement and activities, which then limits our way of thinking of PEH. Our study indicates that scientism and commitment to a performance approach focused on skill acquisition is still prominent, at least in the textbooks, which favours students who already have these skills. In our ongoing work, we would like to learn more about the constitution of dominating language in PEH; may it assist in improving equality and equity in schools, or is the tradition in PEH still one-sided (cf. Wright, Citation2000)?

In this paper, we have introduced a method to study the subject-specific literacy within PEH. Our analysis has revealed hierarchies of concepts in the school subject and displays which content that is prioritised by the linguistic expressions. This, in turn, contributes to the explanation of the ways the school subject is expressed in teaching and assessment practice. Uncritical use of the textbooks will, by references to areas such as competitive sports, training methods, physical strength, physical endurance and ways of testing capacity, reproduce problematic traditions that may promote some students and marginalise others (cf. Evans & Davies, Citation2008; Rossi, Tinning, McCuaig, Sirna, & Hunter, Citation2009; van Amsterdam et al., Citation2012).

Our results may to some extent explain why teachers tend to select the traditional content in their classes and make their assessment based on skills and abilities that are not part of the core content or the criteria for assessment in the subject. From a teacher's perspective, the subject-specific literacy that relates to sports may assist in the teaching process and in the assessment of the students’ knowledge in PEH. However, the weak subject-specific literacy that is related to other parts of the school subject may support internalised assessment criteria and a non-transparent grading process. Difficulties to interpret the PEH curriculum may promote sports content because of the strong subject-specific literacy that relates to these parts; presumably, a similar situation is at hand for the biomedical health field. In the current situation, the combination of sports and health in a school subject, may be based on the premises of sports and conducted at the expense of a health-promotive approach. To assist in the negotiation of the discourse, a subject-specific literacy related to a health-promotive perspective that is more pronounced than one of sports, needs to be further investigated and developed (cf. Quennerstedt, Citation2008; Schenker, Citation2018).

Textbooks

Idrott och hälsa 7–9 (Gardestrand Bengtsson & Gardestrand; Liber 2016).

Idrott och hälsa. Fakta (Andersson & Tedin; Gleerups 2009),

Idrott och hälsa (Johansson; Liber 2012),

Idrott och hälsa 1&2 (Paulsson & Svalner; Roos & Tegnér 2014).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katarina Lundin

Katarina Lundin is an Associate Professor in Scandinavian Linguistics, Centre for Languages and Literature, Lund University, and Guest Researcher at the Department of Sport Science, Linnaeus University, Sweden. Her research is focused on language use in sport contexts inside and outside school, on the one hand, and grammar and applied linguistics, on the other. In addition, she is involved with Swedish teacher education at Lund University and HPE teacher education at Linnaeus University.

Katarina Schenker

Katarina Schenker is an Associate Professor at the Department of Sport Science, Linnaeus University, Sweden. Her research concerns school Health and Physical Education (HPE), HPE teacher education and also the Swedish Sports Movement. Her interests are mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion in relation to democracy, equity and social justice. She studies ontological and epistemological-related decisions in the schooling context. Currently, she is on the board of the Swedish Research Council for Sport Science.

Notes

1 Note that subject-specific literacy is not related to the concept ‘physical literacy’, as depicted by Whitehead (Citation2010). The concept ‘physical literacy’ is beyond our scope of interest.

2 It should be noted, though, that the fourth textbook, Idrott & hälsa 1&2 (Paulsson & Svedner) is complemented by an exercise book with the specific aim of highlighting crucial facts and concepts. The exercise book is however not included in the study, since neither of the other textbooks includes a complementary book and since the fourth textbook per se contains a similar number of pages as the others.

3 LIX, short for Läsbarhetsindex, ’readability’, is used to get an idea of whether a Swedish text is easy or difficult to read. The index is based on the average words per meaning and the proportion of long words (words containing more than 6 letters), in percent. LIX was developed by Björnsson (Citation1968).

References

- Annerstedt, C., & Larsson, S. (2010). ‘I have my own picture of what the demands are … ’: Grading in Swedish PEH—problems of validity, comparability and fairness. European Physical Education Review, 16(2), 97–115.

- Björnsson, C.-H. (1968). Läsbarhet [readability]. Stockholm: Liber förlag.

- Borghouts, L. B., Slingerland, M., & Haerens, L. (2017). Assessment quality and practices in secondary PE in the Netherlands. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(5), 473–489.

- Campbell, D., Gray, S., Kelly, J., & MacIsaac, S. (2018). Inclusive and exclusive masculinities in physical education: A Scottish case study. Sport, Education and Society, 23(3), 216–228.

- Chomsky, N. (2005). The minimalist program. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Clarke, G. (1992). Learning the language: Discourse analysis in physical education. In A. C. Sparks (Ed.), Research in Physical Education and Sport. Exploring alternative visions. London: RoutledgeFalmer, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Dalen, T., Ingvaldsen, R. P., Roaas, T. V., Pedersen, A. V., Steen, I., & Aune, T. K. (2017). The impact of physical growth and relative age effect on assessment in physical education. European Journal of Sport Science, 17(4), 482–487.

- Ekberg, J.-E. (2016). What knowledge appears as valid in the subject of physical education and health? A study of the subject on three levels in year 9 in Sweden. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(3), 249–267.

- Ekberg, J.-E. (2020). Knowledge in the school subject of physical education: A Bernsteinian perspective. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1823954

- Evans, J. (2003). Physical education and health: A polemic or ‘let them eat cake!’. European Physical Education Review, 9(1), 87–101.

- Evans, J., & Davies, B. (2008). The poverty of theory: Class configurations in the discourse of Physical Education and Health (PEH) this paper was presented as the 2005 scholar paper for the British educational research association Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy special interest group. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 13(2), 199–213.

- Gard, M., & Wright, J. (2001). Managing uncertainty: Obesity discourses and physical education in a risk society. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 20(6), 535–549.

- Gerdin, G., & Larsson, H. (2018). The productive effect of power:(dis) pleasurable bodies materialising in and through the discursive practices of boys’ physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(1), 66–83.

- Hipkiss, A. M. (2014). Klassrummets semiotiska resurser: en språkdidaktisk studie av skolämnena hem- och konsumentkunskap, kemi och biologi [Semiotic resources in the classroom: a linguistic and didactic study of the school subjects domestic science, chemistry, and biology]. Diss. Umeå: Umeå.

- Holm, L. (2018). Semantiska grundbegrepp [semantics]. Lunds universitet: Språk- och litteraturcentrum.

- Kageura, K. (2002). The dynamics of terminology: A descriptive theory of term formation and terminological growth. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Karlsson, S., & Strand, H. (2012). Text i verksamhet: Mot en samlad förståelse [text in context: Towards an overall understanding]. språk och stil. Tidskrift för svensk språkforskning. Tema Text, 22(1), 110–134.

- Kroon, J., et al. (2016). Vad är “kroppslig förmåga”? Om behovet av ett yrkesspråk i idrott och hälsa. Hur är det i praktiken? [what is “physical ability”? On the need for a professional language in PEH]. In H. Larsson (Ed.), Red (pp. 117–128). Stockholm: Institutionen för idrotts- och hälsovetenskap.

- Larsson, H., & Karlefors, I. (2015). Physical education cultures in Sweden: Fitness, sports, dancing … learning? Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 573–587.

- Larsson, H., & Nyberg, G. (2017). ‘It doesn't matter how they move really, as long as they move.’ Physical education teachers on developing their students’ movement capabilities. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(2), 137–149.

- Larsson, H., & Redelius, K. (2008). Swedish physical education research questioned—current situation and future directions. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 13(4), 381–398.

- Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind and World dialogically: Interactional and contextual theories of human sense-making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Lundin, K., & Schenker, K. (2018a). Att fördjupa ämnes- och språkkunskaperna (ämnesspecifik text: Idrott och hälsa) [Towards a deeper subject-specific knowledge and competence in Swedish: The case of Health and Physical education]. In Skolverket (Ed.), Modulen Språk-och kunskapsutvecklande ämnesundervisning för nyanlända elever den första tiden. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Lundin, K., & Schenker, K. (2018b). Skrivutveckling i alla ämnen (ämnesspecifik text: Idrott och hälsa) [developing a written language in ever school subject: The case of Health and Physical education]. In Skolverket (Ed.), Modulen Språk-och kunskapsutvecklande ämnesundervisning för nyanlända elever den första tiden. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Lundvall, S., & Meckbach, J. (2003). “Det var en gang ett par sockiplast”: om kroppsövningsämnet i skolan. [On physical exercise in school]. In S. Selander (Ed.), Kobran, nallen och majjen: Tradition och förnyelse i svensk skola och skolforskning (pp. 155–170). Stockholm: Myndigheten för skolutveckling.

- Lynch, T., & Soukup, G. J. (2016). “Physical education”, “health and physical education”, “physical literacy” and “health literacy”: global nomenclature confusion. Cogent Education, 3(1), 2–22.

- McCuaig, L., & Tinning, R. (2010). HPE and the moral governance of p/leisurable bodies. Sport, Education and Society, 15(1), 39–61.

- Nestlog, B. E. (2019). Ämnesspråk – en fråga om innehåll, röster och strukturer i ämnestexter [subject-specific literacy – a question about content, voices and structures in subject specific texts]. HumaNetten Nr, 42, 9–30.

- Nuopponen, A., & Pilke, N. (2016). Ordning och reda. Terminologilära i teori och praktik [order and structure. Terminology in theory and practice]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Nyberg, G., & Larsson, H. (2014). Exploring ‘what’to learn in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 19(2), 123–135.

- Parkinson, S., & Burrows, A. (2019). Physical educator and/or health promoter? Constructing ‘healthiness’ and embodying a ‘healthy role model’in secondary school physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 25(4), 1–13.

- Penney, D., Brooker, R., Hay, P., & Gillespie, L. (2009). Curriculum, pedagogy and assessment: Three message systems of schooling and dimensions of quality physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 14(4), 421–442.

- Peterson, T., & Schenker, K. (2018). Sports and social entrepreneurship in Sweden. Eds: Peterson, T & K schenker. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pilke, N. (2006). Terminological equivalence in parallel texts. Modern approaches to Terminological theories and applications. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Quennerstedt, M. (2008). Exploring the relation between physical activity and health—a salutogenic approach to physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 13(3), 267–283.

- Redelius, K., Fagrell, B., & Larsson, H. (2009). Symbolic capital in physical education and health: To be, to do or to know? That is the gendered question. Sport, Education and Society, 14(2), 245–260.

- Redelius, K., & Hay, P. (2009). Defining, acquiring and transacting cultural capital through assessment in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 15(3), 275–294.

- Redelius, K., & Hay, P. J. (2012). Student views on criterion-referenced assessment and grading in Swedish physical education. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 17(2), 211–225.

- Redelius, K., Quennerstedt, M., & Öhman, M. (2015). Communicating aims and learning goals in physical education: Part of a subject for learning? Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 641–655.

- Ribeck, J. (2015). Steg för steg. Naturvetenskapligt ämnesspråk som räknas [Step by step. Subject-specific literacy in Natural Science] [Dissertation]. Data linguistica 28. Språkbanken, Göteborgs universitet.

- Robinson, D. B., Randall, L., & Barrett, J. (2018). Physical literacy (Mis)understandings: What do leadin physical education teachers know about physical literacy? Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37, 288–298.

- Rossi, T., Tinning, R., McCuaig, L., Sirna, K., & Hunter, L. (2009). With the best of intentions: A critical discourse analysis of physical education curriculum materials. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 28(1), 75–89.

- Saeed, J. I. (2016). Semantics. Fourth edition. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Säljö, R. (2014). Lärande i praktiken. Ett sociokulturellt perspektiv [learning in practice. A socio-cultural perspective]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Schenker, K. (2018). Health(y) education in Health and Physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 23(3), 229–243.

- Schenker, K. (2019). Teaching physical activity – a matter of health and equality? Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(1), 53–68.

- Svendsen, A. M. (2014). Get moving! A comparison of ideas about body, health and physical activity in materials produced for health education in the Danish Primary school. Sport, Education and Society, 19(8), 1014–1033.

- Svendsen, A. M., & Svendsen, J. T. (2016). Teacher or coach? How logics from the field of sports contribute to the construction of knowledge in physical education teacher education pedagogical discourse through educational texts. Sport, Education and Society, 21(5), 796–810.

- Svennberg, L., Meckbach, J., & Redelius, K. (2014). Exploring PE teachers’‘gut feelings’ An attempt to verbalise and discuss teachers’ internalised grading criteria. European Physical Education Review, 20(2), 199–214.

- Svennberg, L., Meckbach, J., & Redelius, K. (2018). Swedish PE teachers struggle with assessment in a criterion-referenced grading system. Sport, Education and Society, 23(4), 381–393.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2011). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare (revised 2018). Stockholm: Swedish National Agency of Education.

- The Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2010). Mycket idrott och lite hälsa [more sports than health]. Stockholm: The Swedish Schools Inspectorate.

- The Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2012). Idrott och hälsa I grundskolan. Med lärandet i rörelse [physical education and health in compulsory school] (skolinspektionens rapport 2012:5). Stockholm: The Swedish Schools Inspectorate.

- The Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2018). Kvalitetsgranskning av ämnet idrott och hälsa i årskurs 7–9 [quality assessment of the school subject physical education and health, grade 7-9]. Stockholm: The Swedish Schools Inspectorate.

- Tidén, A., Redelius, K., & Lundvall, S. (2017). The social construction of ability in movement assessment tools. Sport, Education and Society, 22(6), 697–709.

- Tinning, R., & Glasby, T. (2002). Pedagogical work and the'cult of the body': Considering the role of HPE in the context of the'new public health’. Sport, Education and Society, 7(2), 109–119.

- van Amsterdam, N., Knoppers, A., Claringbould, I., & Jongmans, M. (2012). ‘It's just the way it is … ’or not? How physical education teachers categorise and normalise differences. Gender and Education, 24(7), 783–798.

- van Doodewaard, C., & Knoppers, A. (2018). Perceived differences and preferred norms: Dutch physical educators constructing gendered ethnicity. Gender and Education, 30(2), 187–204.

- Wallian, N., & Chang, C.-W. (2007). Language, thinking and action: Towards a semio-constructivist approach in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 12(3), 289–311.

- Walseth, K., Aartun, I., & Engelsrud, G. (2017). Girls’ bodily activities in physical education how current fitness and sport discourses influence girls’ identity construction. Sport, Education and Society, 22(4), 442–459.

- Webb, L., & Quennerstedt, M. (2010). Risky bodies: Health surveillance and teachers’ embodiment of health. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(7), 785–802.

- Webb, L., Quennerstedt, M., & Öhman, M. (2008). Healthy bodies: Construction of the body and health in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 13(4), 353–372.

- Whitehead, M. (2010). Physical literacy: Throughout the lifecourse. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, & World Health Organization. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health final report. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Wiker, M. (2017). “Det är live liksom” elevers perspektiv på villkor och utmaningar i idrott och hälsa. [conditions and challenges in PEH: A students’ perspective]. Karlstad: Karlstad universitet.

- Wright, J. (1997). The construction of gendered contexts in single sex and co-educational physical education lessons. Sport, Education and Society, 2(1), 55–72.

- Wright, J. (2000). Bodies, meanings and movement: A comparison of the language of a physical education lesson and a feldenkrais movement class. Sport, Education and Society, 5(1), 35–49.

- Wright, J., Burrows, L., & Rich, E. (2012). Health imperatives in primary schools across three countries: Intersections of class, culture and subjectivity. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 33(5), 673–691.

- Zimmermann, T. E., & Sternefeld, W. (2013). Introduction to semantics. An essential guide to the composition of meaning. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.