ABSTRACT

Digital technology is growing in popularity in the enacted teaching and learning process. However, there is ongoing debate regarding the evidence of its impact on teaching and learning in physical education. With increasing use in education, digitally competent teachers are essential to the success of its integration. The primary aim of this study was to explore perceived teacher competency levels in applying digital technology to the physical education classroom. Teachers perceived significantly low competency levels in relation to digital technology in physical education. This was a result of both personal and school hindrances which teachers identified as impeding the integration of digital technology in their physical education classes. Drawing on a holistic view of the dichotomy of pedagogy and technology, we suggest that this relationship is more complex than the one stated in most digital competence frameworks, therefore a narrow understanding of teacher digital competency in physical education.

Introduction

Multiple reports and research have highlighted how the use of digital technology is growing in popularity in the enacted teaching and learning process (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2020; European Commission, Citation2020). However, the evidence of its impact on teaching and learning has received mixed reviews (Davis et al., Citation2013; Henderson et al., Citation2017; Rabah, Citation2015; Säljö, Citation2010). With increasing use in education, teachers who possess digital competence are essential to the success of its integration (Instefjord & Munthe, Citation2017). It is acknowledged in the research how digital technology works best in supporting student achievement when the technology is ‘in the hands of the teacher’ (Denoël et al., Citation2018, p. 46; Thacker et al., Citation2021) – making teacher competency in digital technology a critical factor in student success.

Some research indicates that the use of digital technology in a classroom environment has provided numerous benefits for teaching and learning, for example, an encouraging influence on student motivation and engagement in classwork due to the enactment of digital technology in the teaching and learning process (Bhoje, Citation2015; Lin et al., Citation2017; Østerlie, Citation2018). Further, others discuss how digital technology can improve student collaboration with their peers (Eyyam & Yaratan, Citation2014; Keser et al., Citation2011). Tangkui and Keong (Citation2020) observed how technology facilitated the development of higher order thinking skills, whilst Barron and colleagues (Citation2001) stated digital technology encouraged critical thinking, enhanced communication skills. and provided opportunities for students to explore, learn and motivate oneself.

In physical education, however, the systematic review of Sargent and Calderón (Citation2021) showed that most of the technology-enhanced interventions are not using digital technology in transformative ways (allowing for the enactment of learning tasks inconceivable without the use of technology), but ‘just’ as a direct tool substitute of the teacher, with no functional change. Two of the reasons that can potentially explain those findings that require more research are: (i) teacher digital competency; (ii) and a misunderstanding of the dichotomy pedagogy-technology mainly based on technological or pedagogical determinism (Fawns, Citation2021). Accordingly, and drawing on a more holistic framework that considers the relationships between pedagogy and technology as ‘entangled’ (Fawns, Citation2021), in this paper we explore teacher competency in applying digital technology into the physical education classroom. A sub-aim to this is to identify the effect digital technology has on motivation levels in post-primary school students during physical education class. The paper begins by introducing literature about digital technology before delving into the methodology of the study.

Digital competence frameworks and entangled pedagogy

Existing digital competence frameworks are built based on an amalgamation of technological and pedagogical determinism, where technology and teachers are considered drivers of change (Fawns, Citation2021), and their digital skills are defined by their agency in choosing and using methods and tools to use technology in the classroom (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2015; Redecker, Citation2017). These frameworks suggest digital technology competencies for teachers to accomplish. There is, however, little research suggesting teachers reach these competencies. An exploration of teacher digital competencies allows us to understand what it is to be a ‘digitally competent’ educator, or in other words, ways in which a teacher can effectively incorporate technology in their learning environment. For example, ‘assessment’ competency provides an understanding as to how technology is being used as part of student assessment while the competency of ‘digital resources’ allows educators to recognise the various types of technology selected in educational settings along with how these technologies are managed by educators in their classroom. It is important to understand that digital technology can be broadly defined as electronic devices, systems, tools and resources which generate, store or process data (Department of Education, Citation2018). In Ireland, the ‘Digital Strategy for Schools’ is a government action plan for integrating Information and Communications Technology (ICT) into teaching, learning and assessment (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2015). The framework provides some clarity for educators on the concept of embedding digital technology in a school environment which is based around four key themes to assist educators in implementing education digital technology appropriately in the classroom (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2015):

– Theme 1, Teaching, Learning and Assessment using ICT, describes the use of ICT in teaching and learning, assessment using ICT, inclusion and safety when using ICT;

– Theme 2, Teachers Professional Learning, is directed at supporting teachers in learning how to use ICT and specifying teacher professional knowledge;

– Theme 3, Leadership, Research and Policy, describes leadership needed to integrate ICT across the Irish educational system, using policies and research;

– Theme 4, ICT Infrastructure, describes access to digital technologies, internet, technological maintenance and purchasing of such digital resources.

From a European perspective, in 2017, the Framework for Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu) was published describing digital competencies specific to the profession of teaching (Redecker, Citation2017). The framework, in a similar vein to the Irish framework, lays its theoretical foundations on technological and pedagogical determinism and aims to illustrate various competencies educators should acquire for themselves, their students and their colleagues to become competent in using digital technology in the classroom. The framework entails 22 competencies categorised into 6 areas:

– Area 1, Professional Engagement, explains appropriate use of digital technology for communication, collaboration, reflection and professional development; (e.g. organisational communication, professional collaboration, reflective practice and digital CPD)

– Area 2, Digital Resources, describes the selection, creation and sharing of educational digital resources; (e.g. selecting, creating & modifying, managing, protecting, sharing)

– Area 3, Teaching and Learning, depicts managing, designing and planning the use of digital technology resources in the classroom; (e.g. teaching, guidance, collaborative learning, self-regulated learning)

– Area 4, Assessment, is directed at using digital technology and strategies to assess students’ learning; (e.g. assessment strategies, analysing evidence, feedback & planning)

– Area 5, Empowering Learners, advocates for using technology to enhance inclusion, creating experiences which meet students’ needs and actively engaging learners using educational digital technology; (e.g. accessibility & inclusion, differentiation & personalisation, actively engaging learners)

– Area 6, Facilitating Learners’ Digital Competence, describes allowing learners to responsibly use digital technology for problem-solving, to be creative, to communicate, to learn and to develop literacy skills; (e.g. information & media literacy, communication, content creation, responsible use, problem-solving)

Entangled pedagogy on the contrary, offers a more holistic framework than ‘pedagogy first’ approaches (Glover et al., Citation2016; Sankey, Citation2020), where there is a mutual shaping among technology and pedagogy based on the purpose, context and methods (Fawns, Citation2021). It is similar to the one proposed by Mishra and Koehler (Citation2006) which combines an interplay of content, pedagogy and technology rather than treating these bodies as separate entities. In the entangled pedagogy, technology is not seen as neutral, but as multiple, contextual and relational, and agency is not only relying on teachers, but as something that has to be negotiated between the teachers, technology, students, policy infrastructure, etc. Therefore, the outcomes are not predictable and are subject to complex relations. Under this framework, uncertainty, imperfection and openness have to be embraced, and skills and knowledge are distributed and configurated based on orchestration of different variables and practices (Fawns, Citation2021).

Digital technology for teaching and learning in physical education

Digital Technology in school has become an influencing strategy for teachers to use in support of their pedagogical practices (Casey et al., Citation2016) and student learning (Casey & Jones, Citation2011). It is important to note however, that using technology with no intent on facilitating learning will not enrich the educational experience (Bodsworth & Goodyear, Citation2017). Indeed, the main findings on technology-based interventions, including online and blended, in physical education, found that the use of technology was mainly focused to enhance health or motivational variables, but not curriculum learning outcomes (Killian et al., Citation2019; Sargent & Calderón, Citation2021). As Sargent and Casey (Citation2019) reported, some types of digital technology used in physical education classes include iPads, Exergaming (Meckbach et al., Citation2013), Wii Fit Plus (Almqvist et al., Citation2016), apps and social media (Casey et al., Citation2017), video projectors and heart rate monitors (Thomas & Stratton, Citation2006). Student motivation is a key characteristic in the implementation of digital technology. Findings from Ferriz-Valero et al. (Citation2022) showed that the flipped learning approach was beneficial to develop student autonomous motivation, especially in boys, and to improve student’s health-related fitness knowledge (Østerlie & Mehus, Citation2020). An increase in the long-term engagement of girls was also observed when the focus was not on the physical domain of learning, but in more social and affective domains (Goodyear et al., Citation2014). Similar studies also reported positive findings after the use of video analysis tools to facilitate peer-to-peer and inclusive learning experiences (Pyle & Essingler, Citation2015; Thacker et al., Citation2021).

Said that and despite the dominant techno-deterministic and techno-positivism discourses, some research highlights teacher’s resistance to change when the possibilities (and potentialities) of integrating digital technology into their practice. Rather, these teachers would rather teach the subject using traditional teaching methods (Kretschmann, Citation2015).

While there are many benefits in using and adopting digital technology into the classroom, it is important to acknowledge the drawbacks. Time is one of the biggest influencers as to why teachers would not use digital technology in the classroom (Palao et al., Citation2015). Further to this, teachers not being competent in using or teaching through digital technology emerged as an obstacle for educators using technology – a drawback for both teacher and pupil learning (Bodsworth & Goodyear, Citation2017). Clarke and Zagarell (Citation2012) identified a lack of teacher knowledge and training as a big reason for teachers not implementing technology into their classroom. Research indicates the many internal and external barriers to enacting digital technology in the classroom (Wachira & Keengwe, Citation2011). Internal barriers included time it takes to develop a lesson, lack of competency and computer anxiety. External barriers reported were inadequate access to technology and lack of support in technology integration. The issue of classroom management and distraction is a key focus when introducing and implementing digital technology with students. McCoy (Citation2016) investigated digital distractions in the classroom finding digital technology not only caused distractions for learners but students’ motivation to engage in a distractive behaviour increased when digital technology was incorporated into the lesson.

Before moving on to the methodology, we remind the reader of the objectives of this paper. This paper aims to explore teacher competency in applying digital technology into their physical education class and identify if students’ motivation levels change as a result of integrating digital technology into physical education class. Three research questions were examined:

What is Irish physical educators’ perception of competency levels in using digital technology?

What factors are preventing physical educators from becoming digitally competent in their classroom?

What are teachers’ and students’ perspectives of the use of digital technology on student motivation?

Methodology

A qualitative approach was adopted for this paper as it is based on the values, beliefs, thoughts and social context of a particular population (Bryman, Citation2012). Qualitative research allows for more of an in-depth response from participants towards questioning students’ motivation (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2013) – particularly from a student perspective as it is difficult to get a deep response from students by using a questionnaire/survey. Ethical approval was obtained by the first authors’ university. Participants were purposively sampled (Bryman, Citation2012) and a total of 4 teachers and 12 students participated in the research study. The teachers participated in individual semi-structured interviews during school times. Students were randomly selected by their teacher to partake in focus group interviews. These students were 5th Year (typically aged 16–17 years old) students which were intentionally chosen as these students would have had greater and more extended experience in Physical Education compared to Junior Cycle students (i.e. first three years of post-primary schooling). Pseudonyms are given to participants when reporting data.

Data collection

For the teachers, data were collected through semi-structured interviews which allowed for structured interview questions with the freedom to follow and explore certain answers (Bryman, Citation2012). For the students, a focus group semi-structured interview was used to collect the data. A focus group allows for a facilitated discussion whereby participants can build on each other’s thoughts and ideas – gaining in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences (Leung & Savithiri, Citation2009). The semi-structured interview questions were designed in relation to the European Framework for Digital Competence of Educators (Redecker, Citation2017). Questions were characterised by six categories regarding the framework: (i) Professional Engagement (e.g. describe what you like most about teaching with technology); (ii) Digital Resources (e.g. how have you managed the use of digital technology in your PE class for teaching and learning?); (iii) Teaching and Learning (e.g. how comfortable would you be in creating and delivering distance learning lesson plans using digital technology?); (iv) Assessment (e.g. how have you used technology as part of student assessment?); (v) Empowering Learners (e.g. how do you believe digital technology affects student engagement in the learning process of your class?); and (vi) Facilitating Learners Digital Competence (e.g. to what extent were students being responsible when using digital technology during your PE class?). To emphasise, the interviews followed a semi-structured format which allowed for a structured interview schedule but the flexibility to delve into certain answers depending on the participants’ responses.

Data analysis

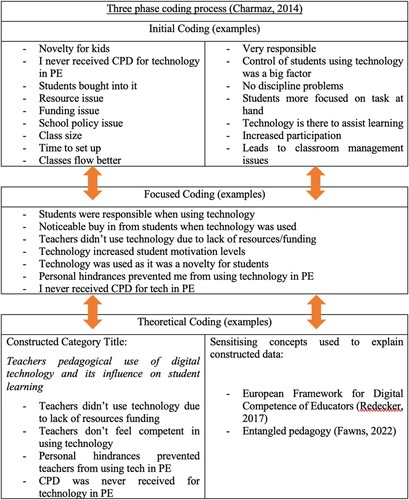

Transcripts of each interview and focus group were generated and carefully read to ensure accuracy. Data analysis was conducted through a three-phase coding process based on Charmaz’s (Citation2014) approach to data analysis. These phases included initial coding, focused coding and theoretical coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). During the initial coding phase, coding was completed in a line-by-line and incident-by-incident approach. The codes corresponded to words used by the participants to reduce possibility for author interpretation (Scanlon et al., Citation2020). During the second coding phase, categories and subcategories were constructed. This phase allowed for the construction of common codes to be selected and reviewed through a comparative fashion (Weed, Citation2009). During the final coding phase, theoretical links and relationships were created between the underlying theoretical framework and the categories assembled (Charmaz, Citation2014). offers an insight into each phase of coding performed for the research article. The bilateral arrows indicate how coding is a dualistic process occurring between each coding phase – showing each phase is not an entity on its own (Thornberg & Charmaz, Citation2012).

Figure 1. Examples of codes during the three phased coding process (Adopted by Scanlon et al., 2020).

As a result of the coding process, three categories were constructed: (i) teachers’ pedagogical use of digital technology and its influence on student learning; (ii) the use of digital technology’s influence on student motivation; and (iii) students’ engagement levels when using digital technology.

Findings and discussion

The qualitative data in this article was used to explore digital competency levels of physical education teachers and the influence digital technology has on student motivation in the learning process. In each of these categories, views and opinions from the teachers’ and students’ perspective will be explored and discussed; the amalgamation of findings and discussion allowed for a more in-depth understanding and exploration, aligned with the more holistic and entangled version of the relationships between pedagogy and technology (Fawns, Citation2021).

Internal and external factors enabling and constraining teachers’ use (and understanding) of digital technology

The first research aim was to explore teachers’ competence in using digital technology in their physical education class. There was a range of digital technologies used within physical education lessons by the teachers which included projectors, heart rate monitors, iPads, Microsoft Connect, Google Classroom, YouTube, Wii Sport and Xbox Connect. Although these were all used within physical education classes, digital technology was only used sporadically throughout the year during their classes. The definition of digital technology was earlier defined as electronic devices, systems, tools and resources which generate, store or process data (Department of Education, Citation2018). While this definition of digital technology covers an array of platforms, the teachers conceptualised digital technology as a video which students would observe as part of a learning experience. The study discovered the management strategies in which digital technology was implemented by the teachers in their physical education class. Teachers mainly used only one piece of technology (Thomas) where students would have all been watching the same video at the same time (Darragh). The teachers viewed the use of digital technology for an instrumental purpose, i.e. used a means to do ‘something’. One teacher alluded to how he used digital technology as a means for reflections for the Classroom Based Assessment (CBA): we moved to an online reflection sheet for their CBA (Darragh). Another commented on how he used it to support his teaching, giving an example of how digital technology was drawn on for student collaboration through pair work: they [students] were working in pairs so it was peer learning (Peter). Referring to the functionalist purposes, Darragh discusses how digital technology was used for the purpose of recording group performances: We used to record gymnastic performances on school iPads so that they would be able to see themselves doing the movement (Darragh). Similarly, digital technology was mentioned for the use of watching videos: I put on a clip for them on YouTube and they followed that and really enjoyed that (Sarah).

There were several reasons to what prevented the teachers from implementing digital technology on a more regular basis, and in a less instrumental and more holistic way (Fawns, Citation2021). All teachers, except one, had experience in using some form of digital technology in their physical education class. In saying this, the consensus was that they did not feel competent in using digital technology – believing it was a personal hindrance to the integration of a digital platform into their physical education class. Teachers perceived competency levels were dependent on the level of technology incorporated into the class. As a result of the lack of competency perceived by physical education teachers, digital technology was dismissed or not implemented to support student learning in their physical education classes. Studies done with pre-service teachers showed how important it is to have a positive attitude to favour more effective uses of digital technology in the classroom (Tondeur et al., Citation2021), and that was not always the case in our sample of teachers. Other personal hindrances which teachers stated were time management issues (it is just time consuming. That is probably the biggest problem with them (Thomas)), a preference for physical activity time (I would rather see them just play away and active instead of stopping their games to bring them in to watch a video clip or something (Sarah)), and trust in students:

Now, you would have to put your trust in the students and normally they are very good, but it would be hard to take that risk as well if something did occur from someone having a phone and not doing what they were meant to be doing with the phone. That would be a risk, inside in class. (Sarah)

There was a common thread throughout the interviews on the effect the school context and the constraints within that had on teachers’ implementation of digital technology. Resources and funding proved to be the most constraining factors as the teachers explained how they did not use technology regularly due to lack of funding and/or resources for such equipment in physical education within their school: the money isn’t there to fund them unfortunately (Thomas). This constraint was reiterated several times by the teachers which Peter articulates: excuses are diminishing in relation to implementing digital technology as a teacher, but money and management are two things that will not go away. In relation to resources, access to digital technology was either limited or not available: We don’t have resources to implement lessons with technology (Thomas).

It is noteworthy that none of the teachers interviewed received Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for digital technology in a physical education context. Any opportunities to engage in CPD were not physical education specific: It wouldn’t have been PE [physical education] specific, no. It would have been just a general ‘here’s how to use projectors, here’s how to connect all that stuff’. We haven’t done it specifically for PE ever (Darragh). CPD webinars were available, but these were seen as basic and for ‘entry-level’ teachers who are unfamiliar with technology: I’ve been to two webinars and I find that they are very, very basic, for teachers who have been out for a while, entry-level technology. I would like to see more advanced webinars if that would be possible (Peter). The lack of CPD came as a challenge to teachers when trying to implement technology into the physical education class. This lack of teacher investment, despite digital technology playing a major part in the curriculum, resulted in a largely pessimistic response regarding the effect digital technology had on student learning from a teacher’s perspective. For digital technology to contribute to student learning, the teachers felt the learning experience needs to be scaffolded to use technology as a learning aid, otherwise the allure to do the opposite of what they [students] are told is too great (Darragh). Yet the lack of professional development the teachers received in constructing this type of learning experience constrains this potential.

The teachers’ responses align with Wachira and Keengwe’s (Citation2011) categorisation of ‘external’ and ‘internal’ barriers in implementing digital technology. In this category, we can see the personal barriers (internal) and school context and CPD (or lack of) as barriers (external). Similar to Wachira and Keengwe’s (Citation2011) work, the teachers identified a lack of resources as an external barrier in integrating digital technology into the classroom. In line with other research (Orlando, Citation2014; Palao et al., Citation2015; Wachira & Keengwe, Citation2011), lack of funding and time provided to be significant barriers for the teachers in successfully integrating digital technology into their physical education classes. Lack of competency was highlighted by teachers as an obstacle for integrating such an approach in the classroom (Bodsworth & Goodyear, Citation2017; Wachira & Keengwe, Citation2011). Due to this incompetency, the teachers opted for a more traditional approach to teaching the subject (Kretschmann, Citation2015). It is personal hindrances such as these which are affecting teacher competency levels in relation to the DigiCompEdu framework. As the literature suggests, teachers need to be supported through professional development (Almusawi et al., Citation2021) so that the digital skills highlighted within the DigiCompEdu can be achieved by the students.

The students believed that digital technology enhanced their ability to learn and improve their understanding – congruent with Casey and Jones’s (Citation2011) finding. One student stated: ‘for understanding I prefer using [digital] technology’ (Focus Group 1). Another student commented: ‘I feel like the videos provided by [digital] technology really help me to improve my form (Focus Group 1) while students agreed that digital technology brought a wider range of activities done in PE’ (Focus Group 2). Technology was also discussed to be a resource to assist learning but not a substitute of teaching: ‘I feel it [digital technology] is there to assist the learning, not to take over’ (Peter). This is very much comparable to Sankey’s (Citation2020), and Fullan’s (Citation2013) research in ensuring teachers put pedagogy before technology in an educational environment. Although, caution should be considered given the limitations of that understanding of the mentioned dichotomy (Fawns, Citation2021; Tsui & Tavares, Citation2021).

The lack of CPD which teachers spoke of is congruent with Clarke and Zagarell’s (Citation2012) study which found a lack of teacher knowledge and training was an influence for teachers not incorporating digital technology into their classes. This finding is significant in relation to the DigiCompEdu framework which highlights ‘Digital CPD’ as a key topic in Area 1 – Professional Engagement – developing competency in using digital technology. Opportunities for professional engagement in developing physical education teachers’ digital competency must be more readily available if the platform is to have any success in supporting student learning – CPD would be an ideal setting in which digital competence could be improved.

The influence of digital technology on student motivation

From a teacher’s point of view, digital technology was perceived to have a positive impact on student motivation. It was observed that students maintained a higher level of motivation throughout class due to the implementation of technology: They are motivated to use the technology … I find the technology helps keep them motivated … there’s no actual work to motivate them … they are more motivated [when using digital technology] (Peter). Digital technology also motivated students who did not particularly enjoy physical education: It also motivated some students who mightn’t like PE [physical education] as much as others (Thomas). One teacher also discussed how he never had any problems with student discipline once technology was brought into their physical education class as the students became more engaged, more motivated [when digital technology is introduced], they are more interested (Peter). As expected, this was dependent on each individual teachers’ context and student body as one teacher believed digital technology led to students becoming very easily distracted (Darragh). This was in the situation whereby students were using their own phones or left on their own guidance when using digital technology during physical education class.

There was a mixed response from students when it came to the effects on motivation received from using digital technology. Some students enjoyed using technology in their physical education class whilst others were not as enthusiastic. Some felt that digital technologies improved motivation, engagement and concentration in the physical education class. Others believed their [motivation] decreased [and would] prefer PE [physical education] classes without technology (Focus Group 2). Each group agreed that they enjoyed trying digital technology in physical education class: It was good craic to try it out, like, I’m happy we tried it out (Focus Group 2). A significant reason for an increase in student motivation was as a result of the novelty digital technology provided: The technology is a new experience. We haven’t really used it before, so it was nice to be introduced to something new (Focus Group 1). Interestingly, there was a belief that digital technology cannot replace a teachers’ feedback or motivational comments: A person can show more emotion than a screen. If there was a teacher, it would be a bit more motivational because they have emotion in their voice or their tone (Focus Group 1). The lack of a human element to digital technology proved to be something the students disliked about the use of digital technology in the teaching and learning process, emphasising how digital technology should not replace the teaching:

I feel like having a person there shouting at you, getting you to get your work done, it’s more motivating than having an online video … if you have someone beside you pushing you on, especially a friend or even like a coach, just constantly getting you going, I feel that is way more motivating than having a video. (Focus Group 2)

Similar to previous research, when digital technology was incorporated into the physical education classes, student’s motivation increased (Casey & Jones, Citation2011; Pyle & Essingler, Citation2015; Calderón et al., Citation2019). However, that was only the case, when the technology integration was purposeful and have a clear outcome within the pedagogical approach, and not when the technology was only used as a substitute for the teacher with no functional improvement (Sargent & Calderón, Citation2021) as it was mostly the case in this study. Teachers believed students’ motivation not only increased but maintained at a high level due to the inclusion of digital technology. This may have arisen as a result of the ‘novelty’ factor which was alluded to by the students as they acknowledged how digital technology had only been introduced to them in physical education and they did not receive a full physical education unit of learning which incorporated digital technology throughout (González-Cutre & Sicilia, Citation2019). Students’ and teachers’ desire to be more active rather than spending time on using digital technology is similar to Kretschmann’s (Citation2015) research which highlighted how teachers preferred traditional teaching approach to teaching and learning i.e. one without the use of digital technology. This further raises questions of using (or not) digital technology as a means to support pedagogical approaches, but going beyond instrumental conceptions of both, pedagogy, and technology (Tsui & Tavares, Citation2021) and involving students in the design of the digital technology-based learning activities (Fawns, Citation2021).

Students’ engagement levels when using digital technology

Students reported high levels of engagement when digital technology was utilised. Teachers also revealed how digital technology can support them in making the physical education classes run ‘much much better’ and increased the student ‘buy-in’ to the class. An increase in student engagement was also seen when using digital technology was used as part of student assessment. Peter alludes to this when discussing his experience of the students becoming more interested and involved in the learning experience due to the inclusion of digital technology: I find once you bring technology, it makes it a more interesting class, straight away you see them sit up straighter … as I said they are motivated to use the technology, so I find that there’s massive buy in. While comments on engagement were positive, it was also acknowledged how, in some cases, the inclusion of digital technology resulted in ‘classroom management issues’ in terms of distractions and responsibility levels, as evidenced by Henderson et al. (Citation2017) with university students. There was a consensus amongst the teachers that the introduction and integration of digital technology into the classroom depended on classroom management structures which needed to be established before its introduction.

Interestingly, some of the teachers (and students) believed the ‘allure’ of videos (a form of identified digital technology) is evaporating due to the regularity of videos used by teachers in their everyday practice. Darragh stated that unless the video is worthwhile, there is no benefit of showing it to students at all. The students’ responses confirmed this as they discussed when digital technology was introduced for the first time, it had positively affected student engagement levels but over time it began to cause distractions, made the students feel ‘bored’, and did not support students’ concentration levels:

It’s more easily to get distracted by technology as … said before, social media, you are constantly checking Snapchat or Instagram, whereas when you’re outside, the phone is away, technology is away, you are really just working on yourself or you’re working with your teammates or classmates. (Focus Group 2)

Similar to Casey and Jones’s (Citation2011) findings, student engagement increased through the use of digital technology; although through the lenses of a non-deterministic approach, there is no one single cause impacting their increased engagement but an amalgamation of entangled relations (e.g. teachers, students, methods, technology infrastructure, etc.). It is also too complex to assume that all students benefited, or not, by the use of digital technology. While some students acknowledged their increased engagement levels initially, some students believed their engagement diminished over time as they became bored of using digital technology in PE, while others felt their engagement levels stayed at a higher level throughout. While students’ own personal biographies need to be considered, their engagement also depends on ‘how’ digital technology is incorporated within physical education class (Casey et al., Citation2017).

While teachers did not believe they were competent in incorporating digital technology into their physical education class, they did comment on the need to provide a ‘structure’ that can influence the appropriate use of digital technology in teaching and learning process. The result of digital technology causing some distractions indicates that there may need to be more of an emphasis put on a structure towards digital technology in physical education class for both teacher and student. Allowing students, and teachers, to realise that the use of digital technology can enhance their learning for educational purposes is crucial for the success of its integration (Fawns, Citation2021; Tsui & Tavares, Citation2021), but it is equally important, that they understand that the use of technology could generate some distraction, and cyberbullying issues (Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2021) and not always enhance or transform teaching and learning (Sargent & Calderón, Citation2021).

Conclusion and practical considerations

This paper aimed to explore teacher competency in applying digital technology into their physical education class and identify if students’ motivation levels change as a result of integrating digital technology into physical education class. In doing so, we have revealed the complexities physical education teachers face in the integration of digital technology in the teaching and learning process. Personal (and student) biographies and contextual school barriers were identified as having a discouraging influence on the integration of digital technology in the enactment of teaching and learning. However, expectations for teachers in supporting students developing digital literacy is irrelevant if the teachers are not competent themselves (Howard et al., Citation2019). The teachers in this paper found it difficult to effectively integrate digital technologies given they do not feel competent themselves in such integration and/or do not have the resources in place to do so. Given the lack of competence and resources, teachers in this study chose not to integrate (or limit their use of) digital technology into their classes on a continual basis. Instead, they opted for the traditional approach to teaching the subject.

The meaning of ‘digital competency’ and frameworks alike tend to focus on digital know-how, technical proficiency and information literacy. Our findings suggest that technology-enhanced learning experiences in physical education will be more effective when teachers receive appropriate and adequate professional development – preferably on an ongoing basis. When designing learning experiences, educators should consider the interplay of technology, pedagogy and content – much like the ‘entangled pedagogy’ model. From an entangled view, education is enacted collectively by multiple teachers, students, administrators, CPD providers, policymakers, etc. These different stakeholders are not always moving in the same direction, and they enable and constrain what the others can do. Understanding this requires zooming out to look at the holistic picture and understanding the use of digital technology for teaching and learning as distributed across these different stakeholders in interaction with the particular technologies, methods, values, purposes and contexts that are in play. Instructional alignment and backward design might facilitate this process (MacPhail et al., Citation2021). While in this study, digital technology was found to increase student’s motivation levels, it is important for educators to remember that the dichotomy digital technology and pedagogy is more complex than the one stated in most digital competence frameworks, that is why we support the idea of embracing uncertainty, imperfection and honesty (Fawns, Citation2021), when integrating technology and pedagogy in physical education.

We leave the reader with some practical recommendations. First, teachers must understand it is crucial to marry technology, pedagogy, content, context, infrastructure, student voice, etc., when in the planning phase of a lesson. Secondly, we must create an option for progressive webinars which advance in levels as teachers familiarise themselves with the content and the described complex and entangled relationships. Having various levels would allow teachers to progress further beyond an entry-level standard and understand the complexities of integrating digital technologies for teaching and learning. Finally, when designing digital frameworks, there should be a focus on balancing the teaching/learning aspects with effective and appropriate technology integration, and a more holistic understanding of the pedagogy-technology dichotomy. The recently launched ‘Digital Strategy for Schools to 2027’ from the Department of Education in Ireland, though still framed based on pedagogical and technological determinism, seems to be a step in the right direction. While this research was conducted in Ireland, these practical considerations can be adopted and adapted to teachers’ different international context(s).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jason Wallace

Jason Wallace is a Teaching Assistant in the Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences at the University of Limerick. Jason’s research interests include physical education, digital technology and pedagogy.

Dylan Scanlon

Dylan Scanlon is a teacher educator at Deakin University, Australia. Dylan’s research interests include (physical education) teacher education practices, assessment, policy, social justice and figurational sociology.

Antonio Calderón

Antonio Calderón is a (physical education) teacher educator at the University of Limerick (Ireland). His research interest revolves around (digital) pedagogies for teaching and learning in teacher education. He is interested in exploring the reality for teacher educators, school teachers and pre-service teachers in the enacting or learning process.

References

- Almqvist, J., Meckbach, J., Ohman, M., & Quennerstedt, M. (2016). How Wii teach physical education and health. Sage Journals, 1(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016682995

- Almusawi, H. A., Durugbo, C. M., & Bugawa, A. M. (2021). Innovation in physical education: Teachers’ perspectives on readiness for wearable technology integration. Computers & Education, 167, 1–19.

- Barron, A., Orwig, G., Ivers, K., & Lilavois, N. (2001). Technologies for education: A practical guide (4th ed.). Libraries Unlimited.

- Bhoje, G. (2015). The importance of motivation in an educational environment. Laxmi Book Publications.

- Bodsworth, H., & Goodyear, V. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to using digital technologies in the Cooperative Learning model in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(6), 563–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1294672

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. Oxford University.

- Calderón, A., Meroño, L., & MacPhail, A. (2019). A student-centred digital technology approach: The relationship between intrinsic motivation, learning climate and academic achievement of physical education pre-service teachers. European Physical Education Review, 26(1), 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336x19850852

- Casey, A., Goodyear, V., & Armour, K. (2016). Rethinking the relationship between pedagogy, technology and learning in health and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 22(2), 288–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1226792

- Casey, A., Goodyear, V., & Armour, K. (2017). Digital technologies and learning in physical education. Routledge.

- Casey, A., & Jones, B. (2011). Using digital technology to enhance student engagement in physical education.Asia-Pacific Journal of Health Sport and Physical Education, 2(2), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2011.9730351

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

- Clarke, G., & Zagarell, J. (2012). Technology in the classroom: Teachers and technology: A technological divide. Childhood Education, 88(2), 136–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2012.662140

- Davis, N., Eickelmann, B., & Zaka, P. (2013). Restructuring of educational systems in the digital age from a co-evolutionary perspective. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(5), 438–450.

- Denoël, E., Dorn, E., Goodman, A., Hiltunen, J., Krawitz, M., & Mourshed, M. (2018). Drivers of student performance: Insights from Europe. McKinsey & Company.

- Department of Education. (2018). Digital learning planning guidelines. Department of Education.

- Department of Education and Skills. (2015). Digital strategy for school 2015–-2020: Enhancing teaching, learning and assessment. Department of Education and Skills.

- Department of Education and Skills. (2020). Digital learning 2020: Reporting on practice in early learning and care, primary and post-primary contexts. Department of Education and Skills.

- European Commission. (2020). Digital education action plan 2021–2027. European Commission.

- Eyyam, R., & Yaratan, H. (2014). Impact of use of technology in mathematics lessons on student achievement and attitudes. Social Behavior and Personality, 42, 31–42. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.0.S31

- Fawns, T. (2021). An entangled pedagogy: Views of the relationship between technology and pedagogy. Retrieved April 10,2022 from https://open.ed.ac.uk/an-entangled-pedagogy-views-of-the-relationship-between-technology-and-pedagogy/. CC BY SA, Tim Fawns, University of Edinburgh.

- Ferriz-Valero, A., Østerlie, O., Penichet-Tomas, A., & Baena-Morales, S. (2022). The effects of flipped learning on learning and motivation of upper secondary school physical education students. Frontiers in Education, 7, 832778. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.832778

- Fullan, M. (2013). Stratosphere: Integrating technology, pedagogy, and change knowledge. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 62(4), 429–432.

- Glover, I., Hepplestone, S., Parkin, H., Rodger, H., & Irwin, B. (2016). Pedagogy first: Realising technology enhanced learning by focusing on teaching practice. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(5), 993–1002. https://doi.org/10.338910.1111/bjet.12425

- González-Cutre, D., & Sicilia, Á. (2019). The importance of novelty satisfaction for multiple positive outcomes in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 25(3), 859–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18783980

- Goodyear, V., Casey, A., & Kirk, D. (2014). Hiding behind the camera: Social learning within the cooperative learning model to engage girls in physical education. Sport, Education & Society, 19(6), 712–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.707124

- Henderson, M., Selwyn, N., & Aston, R. (2017). What works and why? Student perceptions of ‘useful’ digital technology in university teaching and learning. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1567–1579. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1007946

- Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., Ma, J., & Yang, J. (2019). Seeing the wood for the trees: Insights into the complexity of developing pre-service teachers’ digital competencies for future teaching. ASCILITE, 441–446.

- Instefjord, E. I., & Munthe, E. (2017). Educating digitally competent teachers: A study of integration of professional digital competence in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 37–45.

- Keser, H., Uzunboylu, H., & Ozdamli, F. (2011). The trends in technology supported collaborative learning studies in 21st century. World Journal on Educational Technology, 3(2), 103–119.

- Killian, C., Kinder, C., & Woods, A. (2019). Online and blended instruction in K–12 physical education: A scoping review. Kinesiology Review, 8(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2019-0003

- Kretschmann, R. (2015). Physical education teachers’ subjective theories about integrating information and communication technology (ICT) into physical education. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 14(1), 68–96.

- Krumsvik, R. J. (2014). Teacher educators’ digital competence. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.726273

- Leung, F., & Savithiri, R. (2009). Spotlight on focus groups. The College of Family Physicians of Canada, 55(2), 218–219.

- Lin, M., Chen, H., & Lie, K. (2017). A study of the effects of digital learning on learning motivation and learning outcome. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 13(7), 3553–3564. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00744a

- MacPhail, A., Tannehill, D., Leirhaug, P., & Borghouts, L. (2021). Promoting instructional alignment in physical education teacher education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1958177

- McCoy, B. (2016). Digital distractions in the classroom phase II: Student classroom use of digital devices for non-class related purposes. Faculty Publications, College of Journalism & Mass Communications, 90, 1–43.

- McDonagh, A., Camilleri, P., Engen, B. K., & McGarr, O. (2021). Introducing the PEAT model to frame professional digital competence in teacher education. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 5(4), 5–17.

- Meckbach, J., Gibbs, B., Almqvist, J., Ohman, M., & Quennerstedt, M. (2013). Exergames as a teaching tool in physical education? Sport Science Review, 22(5–6), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.2478/ssr-2013-0018

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

- Orlando, J. (2014). Veteran teachers and technology: Change fatigue and knowledge insecurity influence practice. Teachers and Teaching, 20(4), 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.881644

- Østerlie, O., (2018). Can flipped learning enhance adolescents’ motivation in physical education? An intervention study. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, 2(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.23865/jased.v2.916

- Østerlie, O., & Mehus, I. (2020). The impact of flipped learning on cognitive knowledge learning and intrinsic motivation in Norwegian secondary physical education. Education Sciences, 10(4), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040110

- Palao, J., Hastie, P., Cruz, P., & Ortega, E. (2015). The impact of video technology on student performance in physical education. Technology Pedagogy and Education, 24(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2013.813404

- Pyle, B., & Essingler, K. (2015). Utilizing technology in physical education: Addressing the obstacles of integration. Education Technology, 80(2), 35–42.

- Rabah, J. (2015). Benefits and challenges of information and communication technologies (ICT) integration in Québec English schools. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 14(2), 24–31.

- Redecker, C. (2017). European framework for the digital competence of educators: DigCompEdu. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Säljö, R. (2010). Digital tools and challenges to institutional traditions of learning: Technologies, social. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 26(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00341.x

- Sankey, M. (2020). Putting the pedagogic horse in front of the technology cart. Journal of Distance Education in China, 5, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.13541/j.cnki.chinade.2020.05.006

- Sargent, J., & Calderón, A. (2021). Technology-enhanced learning physical education? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2021-0136

- Sargent, J., & Casey, A. (2019). Exploring pedagogies of digital technology in physical education through appreciative inquiry. In J. Koekoek & I. Hilvoorde (Eds.), Digital technology in physical education: Global perspectives (pp. 1–27). Routledge.

- Scanlon, D., MacPhail, A., & Calderón, A. (2020). Conceptualising examinable physical education in the Irish context: Leaving certificate physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 25(7), 788–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1664451

- Selwyn, N., & Aagaard, J. (2021). Banning mobile phones from classrooms – an opportunity to advance understandings of technology addiction, distraction and cyberbullying. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1), 8–19.

- Sparkes, A., & Smith, B. (2013). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health - from process to product. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203852187.

- Tangkui, M., & Keong, T. (2020). Enhancing pupils’ higher order thinking skills through the lens of activity theory: Is digital game-based learning effective? International Journal of Advanced Research in Education and Society, 2(4), 1–20.

- Thacker, A., Ho, J., Khawaja, A., & Katz, L. (2021). Peer-to-peer learning: The impact of order of performance on learning fundamental movement skills through video analysis with middle school children.. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2021-0021

- Thomas, A., & Stratton, G. (2006). What we are really doing with ICT in physical education: A national audit of equipment, use, teacher attitudes, support, and training. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(4), 617–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2006.00520.x

- Thornberg, R., & Charmaz, K. (2012). Grounded theory. In S. D. Lapan, M. T. Quartaroli, & F. J. Riemer (Eds.), Qualitative research: An introduction to methods and designs (pp. 41–68). John Wiley and Sons.

- Tondeur, J., Howard, S., & Yang, J. (2021). One-size does not fit all: Towards an adaptive model to develop preservice teachers’ digital competencies. Computers in Human Behavior, 116, 106659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106659

- Tsui, A., & Tavares, N. (2021). The technology cart and the pedagogy horse in online teaching. English Teaching & Learning, 45, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-020-00073-z

- Wachira, P., & Keengwe, J. (2011). Technology integration barriers: Urban school mathematics teachers perspectives. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 20(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-010-9230-y

- Weed, M. (2009). Research quality considerations for grounded theory research in sport and psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10, 502–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.02.007