ABSTRACT

Geography alone will continue to ensure that, as long as the United States and Russia place nuclear deterrence at the centre of their security strategies, both offensive and defensive systems will be deployed in the Arctic. As changing climate conditions also bring more immediate regional security concerns to the fore, and even as east-west relations deteriorate, the Arctic still continues to develop as an international “security community” in which there are reliable expectations that states will continue to settle disputes by peaceful means and in accordance with international law. In keeping with, and seeking to reinforce, those expectations, the denuclearization of the Arctic has been an enduring aspiration of indigenous communities and of the people of Arctic states more broadly, even though the challenges are daunting, given that two members of that community command well over 90% of global nuclear arsenals. The vision of an Arctic nuclear-weapon-free zone nevertheless persists, and with that vision comes an imperative to promote the progressive denuclearization of the Arctic, even if not initially as a formalized nuclear-weapon-free zone, within the context of a broad security cooperation agenda.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Geography alone will ensure that, as long as the United States and Russia continue to place nuclear deterrence at the centre of their security strategies, deployments of both offensive and counter-offensive nuclear-weapons systems will continue to include the Arctic. At the same time, while the Arctic remains a nuclear-weapons arena, while accelerating climate change brings new and urgent human security and public safety challenges to the region, and while east-west relations continue to founder, this regional geopolitical community continues to be remarkably stable and to foster reliable expectations that states within it will settle their regional disputes by peaceful means and in accordance with international law. In the interests of preserving that stability, nurturing those expectations, and promoting global nuclear disarmament, denuclearization of the Arctic has been an enduring aspiration among its peoples. That the challenges facing a denuclearization agenda are daunting is certainly clear – after all, two members of the Arctic community command more than 90% of the globe’s nuclear arsenals – yet, the vision of an Arctic nuclear-weapon-free zone persists.

The following explores the aspirations, challenges, and prospects for this compelling vision, and does so in five sections. Section one reviews the presence of nuclear weapons in today’s Arctic. Section two considers proposals for a nuclear-weapon-free Arctic, and the third section focuses on the daunting and particular challenges of Arctic denuclearization. Section four briefly elaborates the theme of an emergent security community in the Arctic, and section five considers forward-looking steps toward the progressive denuclearization of the region in the context of the global commitment to pursue a world without nuclear weapons.

That forward-looking agenda is not focused on a formalized nuclear-weapon-free zone in the Arctic while the rest of the world remains in the grip of nuclear arsenals threatening global destruction, and while the United States and Russia remain enthralled by “modernization” that fosters nuclear use, including first-use, postures. Instead, the following explores actions and policies conducive to strategic stability, the de-escalation of threats, and the promotion of regional cooperation in ways designed to reduce global tensions and promote arms control well beyond the Arctic. Measures to reduce nuclear risks and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in the national security policies of the United States and Russia include a proposal to establish in the Arctic an attack-submarine-exclusion zone. The existing non-militarization of the surface of the central international Arctic Ocean begs for that status to be preserved and formalized through a Treaty. Both stability and denuclearization in the Arctic require a reliable international forum or multilateral institution through which regional states can address common regional security concerns and prevent conflicts external to the region from infecting regional affairs. And in the context of ongoing global diplomatic efforts toward nuclear disarmament, each non-nuclear-weapon state in the Arctic has the opportunity to entrench and formalize its own nuclear-weapon-free status and to cooperate in the formation of a de facto nuclear-weapon-free zone in at least those currently non-nuclear parts of the region.

Nuclear Weapons in Today’s Arctic

As long as the United States and Russia maintain major nuclear arsenals, geography will ensure that at least some of those forces and counterforces will continue to be deployed in the Arctic. Russia’s main sea-based nuclear-weapons arsenal is based in the Arctic on the Kola peninsula, and its nuclear-armed submarine patrols are currently largely confined to the Barents Sea bastion (even though Russia continues to seek reliable access to the Atlantic Ocean for its Arctic-based naval forces). While the United States does not base nuclear weapons in the Arctic and does not currently conduct Arctic patrols with nuclear-armed submarines, it does face the basic reality that any intercontinental missile headed to the American heartland from east Asia, the Middle East, or Russia would traverse some part of the Arctic – hence, the concentration of its strategic ballistic missile interception efforts in the North.

Neither Russian nor American strategic assets in the Arctic are in the service of strictly regional Arctic interests or focused on shaping conditions there. Arctic nuclear weapons and missile defence installations have global, not the Arctic, missions, which means they are unlikely to be removed or substantially reduced without there being some major changes in the global security dynamics that drive strategic missions. Other nuclear-weapon states with sea-based nuclear weapons – notably, China, France, India, and the United Kingdom – have at least a theoretical capacity to deploy submarines equipped with strategic range ballistic missiles (SSBNs) in the Arctic, but they have few geographic or strategic incentives to do so. Some see China as a potential exception. When its nascent nuclear-armed submarine force begins to patrol beyond its home waters, it could theoretically seek to bring its sea-launched ballistic missiles within range of the contiguous United States – in fact, a recent Pentagon report expresses concern about China potentially deploying nuclear deterrent forces in the Arctic (Stewart and Ali Citation2019) – but China is much more likely to seek the anonymity of the open Pacific over the treacherous and American patrolled waters of the Arctic for its sea-based deterrent.

When disarmament progresses to the point that the major nuclear powers give up on their insistence on a triad (air, land, and sea) of launch systems, sea-based systems will not be the first to go. In fact, they are likely to be retained the longest, largely because they are the least vulnerable to pre-emptive attack. Accordingly, both the United States and Russia are concentrating on modernizing sea-based nuclear arsenals, and Russia will certainly continue to see an advantage in its Arctic submarine-based nuclear deployments.

Those sea-launched strategic nuclear weapons represent the main element of the global nuclear arsenal that is based in the Arctic. Russia could also be storing some of its non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Arctic. Given that its non-strategic nuclear weapons are prominently assigned to the Navy, it is likely that some are in storage on the Kola Peninsula as well (Kristensen and Korda Citation2019, 73–84). Russia has also been using the Arctic (for example, Novaya Zemlya in 2017) as a test site for its vaunted “Skyfall” nuclear-powered cruise missile – a weapon, still largely experimental and speculative, that would essentially have an unlimited range.Footnote1 Neither the United States nor Russia bases strategic nuclear bombers or land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles in the Arctic.

The Russian SSBN fleet, in addition to being “modernized,” is patrolling more often, and, inevitably, American attack submarines are paying increasing attention. Russia now operates up to 12 submarines whose sole mission is to carry intercontinental nuclear-armed ballistic missiles (the SSBNs). At least seven of the Russian SSBN subs are assumed to be deployed with the Northern fleet and thus based on the Arctic’s Kola Peninsula. The overall fleet includes three new “Borei” ballistic missile subs, each of which can carry 16 Bulava sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and each of these can be armed with up to six nuclear warheads. The Russian SSBN fleet also includes six Delta VI subs, each with a capacity for 16 missiles carrying up to four warheads. The remaining three boats in the current SSBN fleet are Delta III subs with a capacity for up to 16 missiles (up to three warheads each). All are equipped with torpedoes, none of which is nuclear-armed. Russia currently has up to about 720 sea-launched warheads available for deployment (Kristensen and Korda Citation2019) – although not all are deployed at any one time, and just over half are home-based in the Arctic.

The Russian SSBN modernization program is intended to increase the Borei fleet to eight submarines by the mid-2020s, replacing the Delta VI and III subs, thus reducing the overall SSBN force. Hans Kristensen and Robert S. Norris (Citation2016) of the authoritative Nuclear Notebook note that the future Russian SSBN fleet of exclusively Borei subs will be capable of carrying more warheads than does the current fleet, thus potentially heightening the target value of each SSBN. More warheads on fewer subs are a destabilizing development inasmuch as the pre-emptive disabling of these second-strike deterrent forces may be viewed as more feasible, and hence more tempting. Largely for that reason, it is anticipated that the Kremlin will eventually order another four of the Borei subs, for a fleet of 12, to be roughly equally divided between the Pacific and the Arctic (and bringing the Russian fleet to parity with a future-modernized American fleet).

The United States now has 14 nuclear ballistic missile submarines (Kristensen and Norris Citation2018a), none deployed in the Arctic – that is, they would be capable of operating in the Arctic, but there would be no strategic point to doing so. Each US SSBN can carry 24 intercontinental-range ballistic missiles (the Trident II D5), but these have been modified to comply with the New START Treaty, and thus they currently carry up to 20 missiles each. Normally, two of these boats are in the overhaul and not considered operational – so the usual count is 12 operational American SSBNs, carrying up to 240 missiles (even though not all 12 are always on patrol, and those on patrol do not necessarily carry a full complement of missiles). Each missile is capable of being armed with eight nuclear warheads, but the average payload is said to be four to five warheads, leading to the current Nuclear Notebook count of 1090 warheads on 12 deployed SSBNs. Each sub also has tubes for launching torpedoes. Of the eight to 10 subs at sea at any given time, four or five are thought to be on “hard alert,” with the rest capable of being brought to alert status within hours or days.

US nuclear “modernization” of the SSBN fleet includes the upgrading of current missiles with new guidance systems to enhance targeting. The more consequential “modernization” has the Pentagon planning to replace the existing subs with 12 new versions, which the Congressional Budget Office estimates will cost (including development and purchase) in excess of $128 billion in today’s dollars (Arms Control Association Citation2018b), or about $10 billion each, and that does not include maintenance and operating costs or the cost of their nuclear weapons. Though these programs are still well into the future, even the Navy is worried that things are getting out of hand and that the SSBNs will rob it of the funds it says it needs to pay for all the other ships it has planned. So, the Navy has come up with a novel solution: create a special and separate “National Sea-Based Deterrence Fund” so that the Navy’s regular budget will not have to cover the SSBNs (Mehta Citation2016).

It is worth noting that China, with global strategic interests that include the Arctic, is also acquiring a significant fleet of six nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (Patrick. Citation2018). According to Kristensen and Norris (Citation2018c), each of these is designed to carry up to 12 intercontinental ballistic missiles with one nuclear warhead each. The missiles are thought to have a range of 7,000 to 7,400 km, which means that from patrols in waters near China, the missiles could reach Alaska and Hawaii, but not the contiguous United States. It is not clear whether the Chinese have to date sent their SSBNs on any patrols with nuclear weapons on board. The current Jin-class SSBN is said to be “very noisy,” and analysts assume that China will go on to develop a next-generation SSBN (Kristensen and Norris Citation2018c). At some point, China will acquire the capability to patrol in the Arctic – which is not to say it will – which would put its missiles well within the range of the American heartland.

Attack submarines that trail the nuclear-armed subs, including in the Arctic, do not currently carry nuclear weapons. American and Russian attack submarines are capable of carrying tactical range cruise missiles with nuclear or conventional warheads, but ever since the US/Soviet 1991 Presidential Nuclear Initiatives,Footnote2 they have not carried such weapons. They carry conventional weapons designed to attack other submarines, including SSBNs, as well as surface ships.

Russia currently operates 49 attack submarines (IISS Citation2018), 26 of which are nuclear-powered of various classes, equipped with torpedoes and anti-ship and anti-submarine missiles, and can be fitted with land attack cruise missiles. The rest are diesel-electric attack submarines (SSNs) with similar armaments. The diesel-electric subs are regarded as among the world’s quietist. The United States currently operates 54 nuclear-powered attack submarines (US Navy Citation2019; Nuclear Threat Initiative Citation2017): 39 Los Angeles Class, three Seawolf, and 12 Virginia. All are armed with heavyweight torpedoes, and most also have tactical range land attack cruise missiles. About 60% of American attack submarines operate in the Pacific and 40% in the Atlantic.

American attack submarines do make regular forays into the Arctic. For example, in 2013, an American Seawolf variant of attack submarine travelled from Washington State on the American west coast to Norway via the Arctic Ocean (Axe Citation2016); and in 2015, a Seawolf spent two months submerged under the Arctic ice (Starr Citation2015). A March 2018 Pentagon report, Commander’s Intent for the United States Submarine Force and Supporting Organizations, describes “the main role” of US attack submarines as being to “hold the adversary’s strategic assets at risk from the undersea,” notably including SSBNs on patrol (Commander, Submarine Forces Citation2018) – and those strategic anti-submarine warfare (ASW) patrols include the Arctic.

Every two years the US Navy conducts an Ice Exercise (ICEX) in the Arctic as part of the US Navy Submarine Arctic Warfare program sponsored by the Chief of Naval Operations, Undersea Warfare Division. This biennial Arctic submarine exercise goes back to the 1940s. In addition to these staged exercises, US attack submarines regularly patrol under the Arctic ice, sometimes surfacing near the North Pole (Wezeman Citation2016), all of these formal exercises and routine patrols being the primary means by which the attack submarine fleet develops Arctic operational experience.

In the 2016 ICEX exercise, a five-week event designed specifically to assess the operational readiness of the submarine force, as well as support research for the Navy’s Arctic Submarine Laboratory (Commander, Submarine Forces Public Affairs Citation2016), two Los Angeles-class attack submarines participated in the Arctic operations. The United Kingdom also let it be known in 2016 that it was also resuming Arctic patrols (Harris Citation2016). In 2018, ICEX involved two attack subs (Connecticut and Hartford) and the under-ice firing of Mk-48 torpedoes that carried sensors to gather data on their performance in Arctic conditions. The British Navy sent its HMS Trenchant attack submarine (Faram Citation2018). The three submarines conducted joint operations in the Beaufort Sea from March 7–21, and then rendezvoused and surfaced at the North Pole on 27 March 2018. Collectively, the three subs carried out 20 through-ice surfacings (Callaghan et al. Citation2018).

The Hartford’s Commander characterized the point of the training: to keep from “falling behind” Russian submarine development. And the squadron commander told reporters that “in every case [the Russians] are trying to get faster and better at what they do and integrating technology into their platforms. It’s really sent them on a ramp to where if we don’t continue to do the same, we’ll find ourselves in a place of falling behind” (Sciutto and Cohen Citation2018).

Thinking about a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Arctic

The vision of a nuclear-weapon-free Arctic obviously must contend with the reality of substantial nuclear weapons-related operations there; to this point, nuclear-weapon-free zones (NWFZs) have for the most part been created where nuclear weapons are already absent. In the Arctic, they are a major presence, but that has not stopped significant support for an Arctic without nuclear weapons. Indigenous peoples have proposed and endorsed an Arctic NWFZ (in 1977, 1983, and 1998), as have a variety of civil society groups from outside the region, and about a decade ago there was considerable systematic attention paid to the issue. In 2007 and 2010, the Canadian National group of the Nobel Peace Prize-laureate organization Pugwash issued papers calling for an Arctic nuclear-weapon-free zone (Canadian Pugwash Group Citation2007; Wallace and Staples Citation2010); then in March 2012 the Danish national Pugwash group held a meeting to consider the commitment in a Danish government policy paper that, “in dialogue with Denmark’s partners, the government will pursue the policy of making the Arctic a nuclear weapon free zone” (Avery Citation2013).

A 2010 survey, conducted for the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation of Canada, contacted more than 9,000 residents in eight Arctic states, confirming substantial popular support right across the region for an Arctic NWFZ. The respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with this statement: “The Arctic should be a nuclear weapons free zone just like Antarctica is, and the United States and Russia should remove their nuclear weapons from the Arctic.” The results showed strong agreement in all six non-nuclear-weapon states (NNWS) in the Arctic (ranging from 74 to 83%), and mixed but still significant support in Russia and the US (56 and 47%, respectively) (EKOS Research Associates Inc Citation2011).Footnote3

In 2009, the opening recommendation of an Arctic NWFZ Conference in Denmark (Vestergaard Citation2010) called for the development of modalities for establishing “a nuclear weapon free and demilitarised Arctic region.” Whether those objectives – an NWFZ and demilitarization more broadly – are best pursued in that order, simultaneously, or in reverse order is an important tactical question, but conference participants saw the two pursuits as indelibly linked and critical for the development of a cooperative security environment in the Arctic.

The following does not make the case for such a zone, that having been done effectively by several of the writers and conferences noted above (Axworthy Citation2012; Buckley Citation2013; Vestergaard Citation2010; Prawitz Citation2011; Wallace and Staples Citation2010). The focus here is instead on exploring recent NWFZ proposals, and the challenges they face, with a view to identifying ways in which measures to demilitarize and denuclearize this key geostrategic zone can contribute effectively to the pursuit of global zero, a world without nuclear weapons.

NWFZs are a means of reducing the geographical sway of nuclear weapons and are thus an important and respected mechanism for advancing the goal of disarmament, prohibiting nuclear weapons within those zones, and eliminating the nuclear options of nuclear-weapon states toward states within those zones. Expanding NWFZs is a strategy promoted in the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (Citation1974), Article VII, and states have in fact pursued that strategy with remarkable success. There are now essentially nine such zones or jurisdictions. Five are formal NWFZs: Latin America and Caribbean (Tlatelolco-1967); South Pacific (Rarotonga-1985); South East Asia (Bangkok-1995); Africa (Pelindaba-1996); and Central Asia (Semipalatinsk-2006). Another four zones ban nuclear weapons by treaties or declarations: Mongolia declared its nuclear-weapon-free status in 1992; the 1959 Antarctic Treaty prohibits any military operations there; the 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies prohibits placing nuclear weapons in orbit around Earth, installing or testing these weapons on the Moon and other celestial bodies as well as stationing these weapons in outer space in any other manner; and the 1971 Sea-Bed Treaty prohibits emplacement of nuclear weapons on an ocean floor or in the subsoil (Arms Control Association Citation2017). Nuclear weapons are thus banned from space, the entire global seabed, the Antarctic, 99% of the southern hemisphere land area and almost 60% of the global land mass – including some 114 statesFootnote4 (about 60%) that are home to 1.9 billion people.

Article VII of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) provides for “the right of any group of states to conclude regional treaties in order to assure the total absence of nuclear weapons in their respective territories” – so that is the basic condition, no nuclear weapons on the territories of states in the zone. To attain formal status, an NWFZ requires recognition of such by the UN General Assembly, and within such zones, the prohibition on possession is generally reinforced by prohibitions on deployment and use and is supported by a means to verify compliance. Prohibitions can include research, development, testing, acquisition, manufacture, possession, deployment, stockpiling, use, and/or control of nuclear weapons. Most of these, by the way, are included in the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (which will enter into force for the parties to the treaty once 50 states have ratified it). Some 186 non-nuclear weapon states (NNWS), whether or not they are in an NWFZ, are bound by these same prohibitions by virtue of being parties to the NPT.

While the NPT does not specify the long list of prohibitions included in NWFZs, its provisions are broad and have been taken, in practice and by decisions at NPT Review Conferences, to essentially include the full range of prohibitions. There is a critical exception, in practice if not in law. Notably, five NNWS members of NATO host US tactical nuclear weapons on their soil and all five remain NNWS parties to the NPT, in apparent good standing. Article II of the NPT, however, prohibits NNWS from receiving nuclear weapons by “transfer from any transferor whatsoever” or from manufacturing “or otherwise acquiring” nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices (with research and development understood as part of the process of “otherwise acquiring” nuclear weapons). Accordingly, NPT review conferences regularly feature demands that NNWS in NATO remove US nuclear weapons from their territories.

States within NWFZs generally seek assurances from nuclear-weapon states that they will not be attacked, targeted, or threatened by nuclear weapons. Protocols to the treaties are typically (though not in all cases) signed by the five nuclear-weapon states in the NPT (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, United States) respecting the NWFZs and providing the countries in a zone with such negative security assurances. Article III of the NPT mandates safeguards whose purpose is to prevent diversions of nuclear energy from peaceful uses to nuclear weapons. Additional provisions can include a prohibition on conventional attacks against nuclear facilities and on testing, the latter to be accomplished by having all states within the zone ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (Axworthy Citation2012) – a Treaty that has yet to enter into force due to the failure of certain nuclear-capable states to ratify it (including the United States and China, which have signed but not ratified; and North Korea, India, and Pakistan, which have neither signed nor ratified). Some NWFZs, for example, the Rarotonga zone, include a prohibition on dumping nuclear waste – a serious issue within Russian Arctic waters, given the Cold War dumping, for example, of radioactive waste in the Kara Sea in the area of the Novaya Zemlya archipelago (Digges Citation2018).

The Challenges of Arctic Denuclearization

The basic characteristics and objectives of NWFZs are well established. The extent to which an Arctic NWFZ could meet those clear standards, and the relative priority that should be given to the pursuit of an Arctic NWFZ, is, of course, widely debated. The idea has obvious merit inasmuch as it contributes to the pursuit of global zero – a world without nuclear weapons – but legitimate questions arise regarding the extent to which a focus on the Arctic, a region that hosts a significant portion of the arsenal of one of the major nuclear-weapon states, advances or detracts from the progressive pursuit of a world without nuclear weapons. But before returning to such questions, it is important to review the challenges that confront the effort to establish the Arctic as an NWFZ.

Defining an Arctic Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone

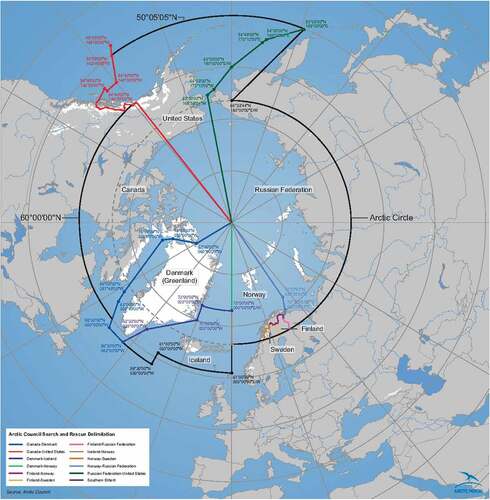

Proposals to establish a nuclear-weapon-free zone throughout the Arctic vary, but the first is the idea that an NWFZ could encompass only parts of the national territories of its members. Some propose a zone confined to all land, sea, and air territory, national and international, above the Arctic Circle, but not including the territories of those same states south of the Arctic Circle. Others propose that the zone includes the entire national territories of all the Arctic NNWS, but only the Arctic territories of NWS Russia and the United States. Another option would be to have the Arctic NWFZ boundaries follow those adopted by the Arctic Council for the Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement (Buckley Citation2013) (see Appendix).

Each of these proposals would affect the major nuclear-weapons facilities of the Kola Peninsula. On the rather obvious assumption that Russia would not be inclined to denuclearize those facilities outside of broader global disarmament initiatives, an Arctic NWFZ would have to include special exemptions – for example, carving the Kola Peninsula out of the zone, while allowing the transit (some variation of innocent passage as opposed to patrols) of Russian SSBNs through parts of the zone on their way to and from their home bases (Prawitz Citation2011). Such exemptions or exceptions would, of course, make it a highly discriminatory agreement – different rules for different states. A significant implication would be the prohibition of Russian SSBN patrols in the Barents Sea.

The geography of the zone, which in all the proposals includes the international Arctic Ocean, also raises the question of whether Arctic states have the capacity or jurisdiction to decide on their own that nuclear weapons should be prohibited from the Arctic Ocean. They clearly do not have such a mandate, but that objective could still be achieved without necessarily requiring a global treaty. NNWS are obviously already oriented and legally bound not to deploy nuclear weapons anywhere, including the Arctic Ocean. Thus, nuclear-weapon states on their own could agree to a collective commitment not to deploy any of their nuclear weapons anywhere within the international waters of the Arctic.

For non-nuclear-weapon states in the Arctic, the essential provisions associated with NWFZs are already in place. The six Arctic NNWS (of the eight Arctic Council member states) – Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Finland – are prohibited by virtue of the NPT from researching, developing, testing, acquiring, manufacturing, possessing, stockpiling, deploying, using, and/or controlling nuclear weapons, in the Arctic or anywhere else.

Nuclear-Weapon States in an NWFZ?

Arctic NWFZ proposals are the first to consider the participation of states with nuclear weapons in a nuclear-weapon-free zone. Complicated exemptions for the United States and Russia on the basic point of an NWFZ – namely, that member states do not possess nuclear weapons – would obviously push the envelope, but Prof. Jan Prawitz (Citation2011) of the Swedish Institute of International Affairs points out that there is an Arctic precedent for special demilitarization provisions applying to only part of a state. Norway’s Spitsbergen is demilitarized, even though the rest of Norway is not, implying that parts of the United States and Russia could be denuclearized, even though the rest of those countries would not be.

Were Russia to remove all its SSBNs from the Arctic in support of an Arctic NWFZ, something that is, to understate the point, not imminent, and redeploy them in the Pacific, that would not be a welcome development for Japan or China – nor the United States, for that matter. Tom Axworthy (Citation2012), a Senior Fellow with the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, emphasizes the point: “the goal,” he says, “is not to create a ‘zone of peace’ free from nuclear weapons in the Arctic and then have a build-up of nuclear weapons right on its border. That would defeat what the zone is trying to achieve.” He refers to what Prawitz (Citation2010) calls the need for “thinning out” of nuclear weapons in the territories just outside the zone as well. In other words, any reduction or removal of nuclear weapons from the Arctic would best be part of a move to reduce weapons globally, rather than just being a decision to redeploy them elsewhere, possibly in more vulnerable and/or provocative locations than the Arctic.

Negative Security Assurances (NSAS)

A prominent feature of nuclear-weapon-free-zone agreements are pledges by nuclear-weapon states that they will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against NWFZ member states. These pledges accord with general negative security assurances – pledges not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear-weapon state that is in compliance with its obligations under the NPT (formalized by all NPT nuclear-weapon states through UN Security Council Resolution 984 of 1995).

These assurances are routinely qualified to allow the threat of nuclear use against non-nuclear-weapon states under special circumstances such as an attack by a non-nuclear-weapon state in cooperation with a nuclear-weapon state. The Pentagon’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review reaffirms these negative security assurances, with the qualification that nuclear-weapons use against non-nuclear-weapon states would be available in response to “significant non-nuclear strategic attacks” on the United States or its allies or partners (Arms Control Association Citation2018a).

But in the case of an NWFZ that included nuclear-weapon states, negative security assurances would have little practical meaning. In the case of the Arctic, not only are there nuclear weapons present, as are the forces of two nuclear-weapon states, but four Arctic states are members of an alliance that explicitly defines itself as a nuclear alliance. The United States and Russia are not about to provide mutual negative security assurances, and Russia is not about to give such assurances to states within NATO. Theoretically, an Arctic NWFZ could include an undertaking to exclude the geographic Arctic within the zone from the target lists of nuclear-weapon states (those within and those not in the zone), but that would be unlikely to extend to entire states and their territories beyond the Arctic. Any arrangement along such lines would obviously bend the traditional meaning of NSAs, but an NWFZ that includes NWS would itself be a major departure from the traditional NWFZ.

There is a precedent for states under an alliance nuclear umbrella to be accepted into NWFZs – notably, Australia within the Rarotonga Treaty zone and states of the Central Asia Zone. Australia is in alliance with an NWS under ANZUS, and three Central Asian NWFZ states (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) are similarly allied to an NWS (Russia) under the Collective Security Treaty Organization. Nevertheless, in May 2014, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, China, and Russia signed the zone’s NSA protocol (Nuclear Threat Initiative Citation2019).

Freedom of the Seas

NWFZs are clearly defined by geography, but international waters adjacent to but not under the legal jurisdiction of NWFZ member states are not automatically covered, and even the 12-mile territorial waters sovereignty of NWFZ states is subject to “innocent passage” – meaning the right of vessels of other states to transit through waters in these zones directly and openly, provided there is no prejudice to the security of the state whose waters are being transited (Article 87 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea [UNCLOS] guaranteeing freedom of the high seas) (Prawitz Citation2010).

Prawitz (Citation2010) points out that “among existing Nuclear Weapon Free Zones, the Antarctic Treaty and the Rarotonga Treaty (South Pacific) include specific provisions that treaty obligations will not infringe upon freedom of the seas within the zone perimeter. The Tlatelolco Treaty defines the zonal area as including substantial parts of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, but nuclear weapon states parties to the security assurances guarantee protocol have made statements of interpretation to the effect that they will not be restricted as regards freedom of the seas in those areas.” The Canadian Pugwash proposal as elaborated by Prof. Buckley (Citation2013) counsels flexibility: “At least in early stages of an NWFZ, it is possible the United Nations’ right of innocent passage could apply to Russia and/or American submarines that may transit the Arctic, but commit not to patrol there.”

Thakur (Citation1998, 19) in his volume on nuclear-weapon-free zones notes that, while NWFZs “should have clearly defined and recognized boundaries,” various options exist. While all states have the right under UNCLOS to enter and use international waterways, Thakur points out that “a group of states can agree among themselves to impose restrictions on their own activities, but not on that of others – although they can invite other states to sign relevant protocols containing similar restrictions.”

Prof. Hamel-Green (Citation2010) notes that:

while nuclear weapon states may seek to insist on their full rights under [UNC]LOS, there is nothing to prevent their agreeing, through binding protocols, to respect specific maritime zones as denuclearized areas and waive their normal rights under the LOS. The nuclear weapon states frequently unilaterally declare ‘exclusion zones’ in open waters for the purpose of missile testing and continue to observe the ban on nuclear weapons in the open waters of the Antarctic Treaty. The possibility of denuclearization is enhanced by the reciprocal undertakings of the US and Russia not to deploy tactical nuclear weapons on ships … .

Verification

The international community already has an impressive array of verification mechanisms in place through the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for confirming NNWS compliance with their obligations under the NPT. But there remain questions regarding the extent to which zone-specific verification mechanisms need to be constructed. For example, do individual states declaring their own territories to be nuclear-weapon-free (as part of an NWFZ) need to mount their own national verification capacity to detect submerged submarines within their waters? And if the Arctic Ocean were to be declared nuclear-weapon-free, by virtue of NWS commitments not to deploy there, what would be the verification requirements and where would responsibility for them be lodged?

Verification is obviously essential to building basic confidence that an NWFZ is in fact what it claims to be, but the focus of verification should clearly be on those areas not covered by other verification and monitoring arrangements, notably those with the IAEA. Since all states that would be in an Arctic NWFZ are members of the NPT, the basic verification mechanisms for detecting diversion from peaceful uses are already in place. Other collective verification efforts, such as confirming the non-presence of nuclear-weapon submarines within or transiting through the zone, might be undertaken cooperatively through a dedicated regional agency. Thakur points to strong precedents for zone-based mechanisms to monitor compliance. A minimum requirement is full-scope safeguards under the IAEA, but existing NWFZs have augmented this with dedicated organizations or secretariats that include responsibilities for verifying compliance. The Tlatelolco secretariat has the authority to call special meetings in the event of emerging concerns but has delegated to the IAEA its powers to conduct special inspections of suspicious activities. The Pelindaba Treaty establishes a 12-member commission to oversee compliance, which can request IAEA inspections that include representatives from the commission. The Bangkok NWFZ empowers the zone’s executive committee to convene a special meeting of members in the event of a breach of its protocols by a nuclear-weapon state. The treaties also variously include provisions for referring issues to regional bodies, to the UN General Assembly, the UN Security Council, or the International Court of Justice (Thakur Citation1998, 16–17).

The Legal Framework

Jan Prawitz (Citation2011) has set out a clear legal framework for an Arctic NWFZ. He proposes an umbrella treaty to which several protocols would be added. The umbrella agreement would “specify the objectives and general purposes of the zone regime, its geographical scope and core parties,” as well as basic verification provisions and “complaints procedures, entry into force requirements, duration and withdrawal.”

A protocol signed by the six NNWS members of the zone would specify their obligations under the Treaty. A second protocol signed by the two NWS members “would specify their obligations as agreed between them and endorsed by the six core NNWSs.” The assumption here seems quite properly to be that, given the unusual circumstances of having nuclear-weapon states within a nuclear-weapon-free zone, it would be necessary for the two states to come to bilateral agreements on arrangements for managing their Arctic operations and facilities in the context of their overall strategic postures. Provisions for Russian nuclear forces on the Kola Peninsula, for BMD installations in Alaska and Greenland, and for anti-submarine deployments/operations would be among the issues to be resolved.

A separate protocol would commit all five NWS recognized as such in the NPT, and perhaps also the three other states with confirmed nuclear arsenals but not technically bound by the NPT (India, Israel, Pakistan), to provide negative security assurances – a commitment not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against any targets within the zone – as well as a commitment not to launch such weapons from anywhere in the zone. All states with nuclear weapons would include in the protocol a commitment not to deploy or operate nuclear-weapons systems anywhere within the zone, including, of course, the international spaces within the zone.

An Arctic Security Community

The most basic characteristic of a security zone that has matured into a cooperative security community – that is, a genuine community of independent states within a defined region – is that there exists a reliable expectation that the states within that regional community will not resort to war to prosecute their disputes. Put another way, such a “pluralistic security community … [is] a transnational region comprised of sovereign states whose people maintain dependable expectations of peaceful change.”Footnote5 And, in fact, that is already a widely affirmed expectation, even if not a guarantee, for the Arctic region. The Ilulissat Declaration (Arctic Ocean Conference Citation2008), reaffirmed in 2018, is a commitment by Arctic states to settle disputes by peaceful means in accordance with international law in general and the Law of the Sea in particular.

Despite today’s obvious NATO–Russia tensions, the Arctic, where NATO states and Russia are both a prominent presence, remains a region of relative geopolitical calm, with all sides still credibly denying the presence of active military threats and insisting that regional conflicts will be resolved through cooperation and international law. It is a welcome and genuine regional reality that seems deeply incongruous with the concentration in the Arctic of submarines bearing nuclear-armed intercontinental-range ballistic missiles, but for now at least, the absence of state-to-state and Arctic-specific military threats is not a case of wishful thinking. It is the considered judgement of both the Kremlin and the current US Government. While Russian Arctic security policies emphasize the refurbishment of its northern military and a growing role for it in protecting national interests in the region, those policies are also replete with commitments to maintaining stability and military cooperation toward that end (Devyatkin Citation2018).Footnote6 American authorities also continue to affirm the absence of Arctic-specific military threats. The US Government Accountability Office (Citation2018), having reviewed the Pentagon’s assessment of the Arctic threat level, concluded with the Pentagon that the threat “remains low” and that the US Department of Defense has the capabilities that are required to carry out the current Arctic Strategy (those capabilities are limited and commensurate with the low threat levels). That strategy, established in 2016, is to pursue “two overarching objectives: to (1) ensure security, support safety, and promote defense cooperation and (2) prepare to respond to a wide range of challenges and contingencies to maintain stability in the region.” Those two objectives are made realistic, says the GAO (2018), by the “low level of military threat in the Arctic” and by “the stated commitment of the Arctic nations to work within a common framework of diplomatic engagement.”

Cooperation

Arctic cooperation is well established. Geography, harsh conditions, and shared interests have made political, economic, and military cooperation a staple of the international Arctic. As Finnish Member of Parliament Katri Kulmuni put it, “if we want to save the Arctic, we need the Arctic countries to cooperate” (Wilson Center Citation2017). Canadian academic Heather Exner-Pirot (Citation2016) reminds us of the plethora of organizations and international agreements that already contribute to Arctic Governance. Sub-regional government-to-government cooperation occurs through groupings like the Barents Euro-Arctic Council and the West Nordic Council. Indigenous communities come together through organizations like the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) and the Saami Council. International agreements like the Law of the Sea and the International Maritime Organization and, more recently, the Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean, are especially important to Arctic Governance. Arctic public safety and security agreements include the 2011 Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic and the 2013 Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic. The Arctic Coast Guard Forum was established in 2015, with all eight Arctic Council states part of the arrangement.

Arctic states have a high expectation that regional conflicts and disputes will be mediated by means other than military confrontation. But the Arctic does not as clearly reflect another crucially important characteristic of a security community: “the absence of a competitive military build-up or arms race involving [its] members” (Acharya Citation2009, 18–21). There is no denying that states in the region are virtually all building up, or declaring a strong intention to build, their conventional military capacities within the region, but it is still not definitively clear whether this “remilitarization” is becoming a “competitive military build-up” that undermines the growing expectation that change will be peaceful, or whether it actually facilitates increased security and public safety cooperation. Much of current military expansion is aimed at building domestic and cross-border support to civil authorities in search and rescue, emergency response, monitoring regional activity, and in ensuring compliance with national and international regulations. While nuclear weapons in the Arctic are clearly not the focus of a regional arms race – global numbers have after all been declining – it is nevertheless hard to deny competitive elements in the deployments of nuclear weapons and related systems in the Arctic.

All five Arctic Ocean states (Canada, Greenland/Denmark, Norway, Russia, United States) nevertheless now see cooperation and the stability it can bring as being in their interests, but in the absence of any overarching institutional or established security architecture or framework with the mandate and capacity to consolidate and entrench an overall climate of cooperation, this inclination has a fragile foundation.

Whether the progressive denuclearization of the Arctic is more likely to be a product of, or a primary means toward, a world without nuclear weapons, will continue to be debated, but in the meantime the Arctic still affords important opportunities for initiatives that could help shape an international climate of security cooperation that in turn will be more conducive to reducing the role of nuclear weapons in the security policies and planning of Arctic nuclear-armed states.

Limiting Attack Submarine Operations

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists notes that Russia is moving to concentrate its sea-based warheads on fewer missiles – in other words, more MIRVed (multiple, independently targeted, re-entry vehicles) submarine-based missiles (Kristensen and Norris Citation2014). That is a destabilizing configuration inasmuch as it makes strategic missile submarines higher value first-strike targets. One persuasive means of precluding first-strike options and planning would be through mutual US/Russian agreements to forgo sending attack submarines (SSNs) into each other’s SSBN operational bastions.

Russia’s SSNs are not really in a position to routinely track and target American ballistic missile-carrying submarines on widely dispersed patrols in the open waters of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Russian SSBNs, on the other hand, are largely confined to strategic bastions and thus are more vulnerable to aggressive anti-submarine activity – suggesting that stability would be enhanced if the United States were to formally commit to keeping its attack submarines out of Russia’s primary areas of SSBN operation. Three familiar but key measures would go a long way toward substantially reducing sea-based risks in general and would certainly apply to the Arctic in particular: that the United States and Russia both reduce the launch readiness of their submarine-based ballistic missiles, that they both refrain from deploying their SSBNs close to each other’s territories, and that they agree not to track and thus threaten each other’s SSBNs with attack submarines in agreed exclusion areas for attack submarines.

One feature of the 1987 Murmansk Initiative of then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev was a proposal to preclude Western anti-submarine warfare operations against the Soviets in the home waters of the Soviet Northern and Baltic fleets (Åtland Citation2008). Well before the Gorbachev idea of ASW-free zones had been floated, Canadian analyst Purver (Citation1983) argued that although the feasibility of putting limits on ASW activities was declining (1983 was, after all, the early Reagan era), the wisdom and desirability of such measures was increasing. As land-based missiles in fixed locations became more vulnerable to pre-emptive attack, the deployment of sea-based strategic nuclear missiles would, within the deterrence paradigm, be a stabilizing presence as survivable second-strike or retaliatory forces. That, in turn, meant that, if the rationale for SSBNs was their relative invulnerability, it would be counterproductive to try to render them vulnerable through ASW efforts.

Hence, analysts like Purver urged the pursuit of measures to limit destabilizing strategic ASW as a serious arms control and risk-reduction objective. Proposals involved agreements to curtail the tracking of SSBNs and the establishment of SSBN sanctuaries or ASW-free zones. Such zones were proposed for the Gulf of Alaska, the Sea of Okhotsk, and the Barents Sea, and as Purver pointed out, these zones were all within what were essentially coastal defence areas and thus capable of being patrolled and protected by their respective defence forces, including tactical ASW forces. There were also proposals for negotiated limits on ASW vehicles, the idea being that if attack subs were kept to no more than two or three times an adversary’s SSBNs, it would be impossible to track all SSBNs simultaneously. For the same reasons, there were also proposals to confine seabed detection devices to areas near national waters and coasts.

A report by Diakov and Hippel (Citation2009, 15–16) proposed again that Russia agrees to confine its northern SSBN fleet to the Arctic and that the United States agrees to keep its attack submarines out of the Russian side of the Arctic. Promoting the Arctic as an area from which attack submarines are excluded or in which their operations are substantially curtailed is not explicitly an Arctic denuclearization measure, but as a realistic risk-reduction measure, it would serve as an important confidence-building development, which would, in turn, be supportive of nuclear disarmament broadly.

It is important to acknowledge the unfortunate reality that the current trend points in the opposite direction, but the pleas for nuclear sanity persist, even in the face of US and Russian determination to build up their respective anti-submarine warfare and ballistic missile defence capacities, while also moving to more accurate offensive ballistic missiles. In early November 2018, a US official told a submarine symposium that “the handcuffs are off now” – by which he meant that under a new Administration the Navy is now free to pursue more intensified levels of strategic ASW. He referred to the United States as being back “in a great power competition now,” in which no adversary will “get a free ticket” (Eckstein Citation2018). A particular initiative involves the development of more lethal torpedoes with which to threaten SSBNs.

The logic of their own deterrence requirements should drive the United States and Russia to welcome strategic ASW-free zones – that is, zones in which their own ballistic missile-carrying submarines would be free of threats of pre-emptive attacks from anti-submarine warfare subs (aided by ASW aircraft). And, given the prominent presence of Russian SSBN forces in the eastern Arctic, the Arctic is a logical location for at least a Russian ASW-free zone.

Preserving the Non-Militarized Surface of the Central Arctic Ocean

Historically, climate and geography have reliably combined to ensure the non-militarization of the surface of the central Arctic Ocean, but that salutary service will not be available much longer. Climate change and growing accessibility mean that preserving the status quo will depend on the international community agreeing to accomplish politically what climate and geography can no longer deliver (Griffiths Citation1979, 61). The idea of prolonging indefinitely the non-militarization of the surface waters of the high Arctic has the great advantage of simply preserving what already exists. Just as the Seabed Treaty preserved the status quo in preventing the deployment of nuclear weapons on the seabed, and just as NWFZs to date have largely preserved the status quo by prohibiting nuclear weapons in places from which they were already absent,Footnote7 demilitarizing the surface of the Arctic Ocean preserves what is already a fortuitous reality. Formal demilitarization in the Arctic has at least one precedent. In 1920, the Svalbard Treaty demilitarized that archipelago, and all Arctic states have ratified the treaty (Byers Citation2013, 256–7). The European Parliament has called for a protected area around the North Pole (Nunatsiaq News Citation2014), evidence of further political support for preserving the demilitarized state of the Arctic Ocean ice and surface waters.

If states agreed to forgo military operations on the surface of the central Arctic Ocean, that would complement the non-militarized seabed, and leave only the demilitarization of the sub-surface of the central Arctic Ocean. This latter demilitarization clearly awaits further progress in global reductions in nuclear weapons and the reinvention of strategic relations in the high North and beyond.

Building Support for Progressive Denuclearization

Popular support for an Arctic NWFZ may not be top of mind in the context of the many daunting challenges facing the region, but it remains thoroughly embedded in most Arctic states. Civil society groups are key to sustaining that support by virtue of having, over the years, presented credible proposals for the region’s progressive denuclearization. Indigenous peoples of the region have been an essential part of the process. The 1977 ICC resolution on “peaceful and safe uses of the Arctic Circumpolar Zone” called for demilitarization; a commitment to “peaceful and environmentally safe purposes” for the Arctic; a prohibition on military bases and fortifications; a ban on testing and the disposition of chemical, biological, or nuclear materials in the Arctic; and “a moratorium … on emplacement of nuclear weapons.” A 1983 ICC resolution on “a Nuclear-Free Zone in the Arctic” repeated the call for the Arctic to be used only for “peaceful and environmentally safe” purposes and called for a prohibition on “testing of nuclear devices in the arctic or subarctic,” as well as a ban on nuclear dump-sites. A 1998 ICC resolution on the “clean-up of military sites” called on the governments of the United States, Russia, Canada, and Denmark to clean up military sites and called “upon the governments of the Arctic countries and the world to designate the Arctic a military-free zone to make sure that reckless and harmful activities are never repeated in the Inuit homeland” (Inuit Circumpolar Conference Citation1983).

Continued leadership from communities in the North will be essential for advancing the agenda of a peaceful, environmentally sustainable and nuclear-free Arctic, and for emphasizing that the most urgent and immediately relevant security imperatives in the Arctic are not fostered by strategic competition or even military preparedness. Instead, they have to do with the sustainable well-being of the people of that region in a time of profound economic and environmental change and social dislocation. Of course, one essential ingredient of the pursuit of human security is regional stability. Peace and stability within and between the states of the region are part of the foundation of local well-being, and while the Arctic has been and still is a zone of cooperation, maintaining that requires close attention to issues like a timely and effective responsiveness to emergencies, as well as the capacity to ensure compliance with environmental, fishing, and other common standards, regulations, and local laws.

In the context of emphasizing measures with positive long-term security impacts and benefits – namely, pursuing deepened cooperation in support of public safety, exploring meaningful restrictions on the operations of attack submarines in the Arctic, preserving the demilitarization that already characterizes the ice and surface waters of the central Arctic Ocean, and promoting shared domain awareness in the region – it is appropriate to continue to debate, define, and declaim the goal of a nuclear-weapon-free Arctic. But, rather than proposing an Arctic NWFZ that would try to accommodate the particular circumstance of the still provocatively armed United States and Russia – accommodations that would necessarily be at odds with the most basic characteristics of such zones (the absolute non-possession of nuclear weapons by all states in the zone) – it may be more credible and effective to pursue the progressive denuclearization of the Arctic without trying to invent a hybrid NWFZ status.

It thus makes sense to first challenge the region’s non-nuclear-weapon states to promote and formalize the de facto denuclearization of their jurisdictions. That effort could adhere to the prevailing NWFZ model, namely, politically and legally reinforcing the denuclearized status quo of non-nuclear-weapon states parties to the NPT. Explorations toward a Canada/Nordic NWFZFootnote8 would present opportunities to sort out negative security assurance arrangements in a zone that includes NATO members – that is, states without weapons on their territories but, in the case of Canada and Norway, still committed to a nuclear alliance. A Nordic NWFZ has been discussed for some time, with learnings available from the 1984–85 study by a bi-partisan commission and the 1987–1991 exploration by a Nordic Senior Officials Group (Hugo Citation2010).

Canadian academic and Arctic expert Byers (Citation2013, 160) makes the useful point that sub-state entities like NunavutFootnote9 or Greenland also have a role to play and could simply declare themselves to be nuclear-weapon-free, the way some cities have, in anticipation of a future time when an Arctic NWFZ becomes a serious item on the international security agenda.

The pursuit of progressive denuclearization must take place in an Arctic that hosts an extraordinary confluence of geostrategic pressures. The challenges of the region’s environmental fragility and changing climate intersect with the human-rights imperatives of its indigenous people. Territorial claims drive the evolutionary application of the Law of the Sea. Traditional strategic rivals are now prodded by pragmatism and mutual self-interest to cooperate in the Arctic. At the same time, increased marine transport and newly accessible frontiers generate new pressures to increase military presence and capacity. And, of course, a concentration of nuclear weapons still hangs in Damoclean warning over the top of the world.

Former UN Under-Secretary-General for Disarmament Affairs Jayantha Dhanapala (Citation2013) has observed that, just as the Arctic is believed to have once formed a land bridge for the earliest human migration from Asia to the Americas, today it promises to build new and paradigm-shifting bridges across geostrategic divides and between continents. The potential for bringing nations and peoples together for peace and development is boundless, but so too is the potential for conflict.

The resurgent military activity is real. The years immediately following the Cold War saw a sharp decline followed by a lull in military/strategic attention to the Arctic, but now the region hosts increased nuclear submarine and bomber patrols, ballistic missile defence installations, and the build-up of conventional military capacity. Indigenous populations are taking wary note; strategic relations between the old Cold War rivals that now must share the Arctic cannot escape being jolted by far-off events; and some contemplate (while others fear) a growing security role for NATO in the Arctic. Russia is certainly expanding its military infrastructure in the region, with observers dividedFootnote10 on whether the objective is primarily improved management and emergency response capacity related especially to the northern sea route, or whether Moscow once again views the Arctic primarily through the lens of geopolitical competition.

The presence of nuclear arsenals and countermeasures in the region adds a dramatic element of both danger and urgency to shaping the future Arctic, and the idea of converting the Arctic into a zone without nuclear weapons has been a feature of both Cold War and post-Cold War hopes for solidifying the Arctic as a region of cooperation rather than conflict. However, logical and compelling cooperation and denuclearization clearly are, the route to an Arctic nuclear-weapon-free zone will not be easy or quick; such a goal is unlikely to be achieved separately from major progress in the larger global pursuit of nuclear disarmament. The prospects are that Russia’s Arctic nuclear arsenal will continue to parallel nuclear-weapons trends globally. As overall numbers decline, so will the number of warheads in the Arctic – and if the New START Treaty is not extended beyond its February 2021 expiry, the trend could reverse, and the Arctic would not be unaffected.

In the meantime, challenges like ballistic missile defence and NATO’s superiority in conventional forces and persistent press eastward mean that even if New Start is extended, “prospects for launching in the near future the next round of bilateral talks on future nuclear cuts are dim.” That is the judgement of Russian Academic Vladimir Rybachenkov (Citation2012), who not surprisingly concludes that the chances for movement toward an Arctic NWFZ “remain substantially reduced.” He notes, perhaps warns, that Russian consideration of an Arctic NWFZ is inextricably linked to the global dynamics of nuclear disarmament.

In summary, the Arctic de-nuclearization agenda is clear: reduce nuclear risks and the role of nuclear weapons in the security policies of the United States and Russia by agreeing to make the Arctic an attack submarine exclusion zone; preserve the existing non-militarization of the surface of the Arctic Ocean through a formal treaty; create an Arctic institution with the mandate to pursue an ongoing security dialogue among Arctic states; devote priority diplomatic energy to fostering global strategic relations that will be conducive to further reductions in nuclear arsenals, including in the Arctic; and encourage NNWS in the Arctic to formalize and entrench their de facto status as a zone free of nuclear weapons.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ernie Regehr

Ernie Regehr is Senior Fellow in Arctic Security and Canadian Defence Policy at The Simons Foundation of Vancouver, and Research Fellow at the Centre for Peace Advancement, Conrad Grebel University College, the University of Waterloo. He is co-founder and former Executive Director of Project Ploughshares and his publications on peace and security issues include books, monographs, journal articles, policy papers, parliamentary briefs, and op-eds. His most recent book is Disarming Conflict: Why Peace Cannot Be Won on the Battlefield (Between the Lines, Toronto, and Zed Books, London, 2015). He is an Officer of the Order of Canada.

Notes

1 A February test took place at a more southerly test site at Kapustin Yar. See Mizokami (Citation2019).

2 In separate unilateral statements in September and October 1991, Presidents George H.W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev undertook to stop deploying tactical nuclear weapons on surface ships and attack/all-purpose submarines.

3 The results were: Northern Canada, 76%; Southern Canada, 78; Denmark, 74; Finland, 77; Iceland, 75; Norway, 82; Russia, 56; Sweden, 83; United States, 47.

4 Tlatelolco, 33 countries; Rarotonga, 13; Pelindaba, 52 (38 signed and ratified and 16 signed but not yet ratified); Bankok, 10; Central Asia, 5; Mongolia, 1.

5 These definitions are taken from Acharya (Citation2009, 18–21). Acharya’s definition is, of course, an elaboration of Karl Deutch’s foundational discussion of “security communities.”

6 See the Arctic Institute’s four-part series on “Russia’s Arctic Strategy” at https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/russias-arctic-strategy-aimed-conflict-cooperation-part-one. Part II focuses on the military and security.

7 This is only largely the case because the Pelindaba Treaty, in fact, helped to confirm the denuclearization that took place in Africa when South Africa divested itself of nuclear weapons, and in other regions, like Tlatelolco, when states with nuclear-weapons programmes agreed to halt them and the NWFZ solidified that posture into the future.

8 Thomas Axworthy explored such a zone in an address to Canadian Pugwash, 26 October 2012: “Revisiting the Hiroshima Declaration: Can a Nordic-Canadian Nuclear-weapon-free Zone Propel the Arctic to Become a Permanent Zone of Peace?”.

9 A region, or territory, in the Canadian Arctic.

10 A good example being testimony found in the recent report of the Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development (Citation2019).

References

- Acharya, A. 2009. Constructing a Security Community in South East Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Arctic Ocean Conference. 2008. “The Ilulissat Declaration.” Arctic Report. https://www.arctic-report.net/en/product/859

- Åtland, K. 2008. “Mikhail Gorbachev, the Murmansk Initiative, and the Desecuritization of Interstate Relations in the Arctic.” Cooperation and Conflict 43: 289–311. doi:10.1177/0010836708092838.

- Arms Control Association. 2017. “Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones (NWFZ) at a Glance” July. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/nwfz

- Arms Control Association. 2018a. “U.S. Negative Security Assurances at a Glance.” March. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/negsec

- Arms Control Association. 2018b. “U.S. Nuclear Modernization Programs.” August. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/USNuclearModernization

- Avery, J. S. 2013. “Towards an Arctic Nuclear Weapon Free Zone.” Christiansborg Palace, April 3. www.arnehansen.net/130403reportclosedMeeting.pdf

- Axe, D. 2016. “The ‘Secret’ Submarines the U.S. Navy Doesn’t Want to Talk about (and Russia Fears)0.” The National Interest. November 19. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/the-secret-submarines-the-us-navy-doesnt-want-talk-about-18463

- Axworthy, T. S. 2012. "A Proposal for an Arctic Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone." InterAction Council.. https://www.interactioncouncil.org/publications/proposal-arctic-nuclear-weapon-free-zone

- Buckley, J. A. 2013. “An Arctic Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone: Circumpolar Non-Nuclear Weapons States Must Originate Negotiations.” Michigan State International Law Review 22 (1). https://digitalcommons.law.msu.edu/ilr/vol22/iss1/5

- Byers, M. 2013. International Law and the Arctic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Callaghan, C., T. Goda, J. Hardy, and L. Estrada. 2018. ICEX ’18: Advancing Cooperation and Capabilities in the Arctic. Washington, DC: Undersea Warfare, US Navy.

- Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development. 2019. “Nation-Building at Home, Vigilance Beyond: Preparing for the Coming Decades in the Arctic.” 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, April. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/FAAE/Reports/RP10411277/faaerp24/faaerp24-e.pdf

- Canadian Pugwash Group. 2007. “Statement on an Arctic Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone.” August 24. https://pugwash.org/2007/08/24/statement-on-an-arctic-nuclear-weapon-free-zone

- Commander, Submarine Forces. 2018. Commander’s Intent for the United States Submarine Force and Supporting Organizations. March. Washington, DC: US Navy. https://www.public.navy.mil/subfor/hq/Documents/Commanders%20Intent%20March%202018.pdf

- Commander, Submarine Forces Public Affairs. 2016. “Navy Submarines Arrive in Arctic for ICEX 2016.” Military.com, March 15. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2016/03/15/navy-submarines-arrive-in-arctic-for-icex-2016.html

- Devyatkin, P. 2018. Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Military and Security (Part II). February 13. Washington, DC: Arctic Institute. https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/russias-arctic-military-and-security-part-two

- Dhanapala, J. 2013. “The Arctic as a Bridge.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, February 4. https://thebulletin.org/2013/02/the-arctic-as-a-bridge

- Diakov, A., and F. V. Hippel. 2009. Challenges and Opportunities for Russia–U.S. Nuclear Arms Control. New York/Washington: Century Foundation.

- Digges, C. 2018. “Russia Updates Maps of Radioactive Debris Sunk in Arctic.” The Maritime Executive, October 15. https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/russia-updates-maps-of-radioactive-debris-sunk-in-arctic

- Eckstein, M. November 14, 2018. “Navy Wants to Use Virginia Payload Modules to Deploy New Missiles, UUVs.” USNI News. https://news.usni.org/2018/11/14/navy-looking-use-virginia-payload-module-deploy-new-missiles-uuvs

- EKOS Research Associates Inc. 2011. “Rethinking the Top of the World: Arctic Security Public Opinion Survey.” http://www.ekospolitics.com/articles/2011-01-25ArcticSecurityReport.pdf

- Exner-Pirot, H. 2016. “Why Governance of the North Needs to Go beyond the Arctic Council.” OpenCanada, October 14. https://www.opencanada.org/features/why-governance-north-needs-go-beyond-arctic-council

- Faram, M. D. 2018. “ICEX Gives Navy, Coast Guard Divers Time under the Ice.” NavyTimes, March 20. https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2018/03/20/icex-gives-navy-coast-guard-divers-time-under-the-ice

- Griffiths, F. 1979. “A Northern Foreign Policy.” 7 Wellesley Papers. Canadian Institute of International Affairs.

- Hamel-Green, M. 2010. “Existing Regional Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones: Precedents that Could Inform the Development of an Arctic Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone” In Conference on an Arctic Nuclear Weapon Free Zone, edited by C. Vestergaard. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

- Harris, N. 2016. “British Submarines Set to Resume Arctic Patrols.” News Punch, April 11. https://newspunch.com/british-submarines-set-to-resume-arctic-patrols

- Hugo, T. G. 2010. "An Arctic Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone: A Norwegian Perspective." In Conference on an Arctic Nuclear Weapon Free Zone, edited by C. Vestergaard. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

- IISS (International Institute of Strategic Studies). 2018. The Military Balance 2018. London: Routledge.

- Inuit Circumpolar Conference. 1983. “ICC Resolution on a Nuclear Weapon Free Zone.” http://www.arcticnwfz.ca/documents/I%20N%20U%20I%20T%20CIRCUMPOLAR%20RES%20ON%20nwfz%201983.pdf

- Kristensen, H. M., and M. Korda. 2019. “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2019.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 75 (2): 73–84. doi:10.1080/00963402.2019.1580891.

- Kristensen, H. M., and R. S. Norris. 2014. “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2014.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 70 (2). https://thebulletin.org/2014/03/russian-nuclear-forces-2014

- Kristensen, H. M., and R. S. Norris. 2016. “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2016.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 72 (3): 125–134. doi:10.1080/00963402.2016.1170359.

- Kristensen, H. M., and R. S. Norris. 2018a. “United States Nuclear Forces, 2018.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 74 (2): 120–131. doi:10.1080/00963402.2018.1438219.

- Kristensen, H. M., and R. S. Norris. 2018b. “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2018.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May 4. https://thebulletin.org/2018/05/russian-nuclear–forces–2018

- Kristensen, H. M., and R. S. Norris. 2018c. “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2018.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, June 28. https://thebulletin.org/2018/06/chinese-nuclear-forces-2018

- Mehta, A. 2016. “Is the Pentagon’s Budget about to Be Nuked?” Defense News, February 5. http://www.defensenews.com

- Mizokami, K. 2019. “Russia Conducts a New Test of its Nuclear-Powered Cruise Missile.” Popular Mechanics, February 6. https://www.popularmechanics.com

- Nuclear Threat Initiative. 2017. “United States Submarine Capabilities.” November 22. https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/united-states-submarine-capabilities

- Nuclear Threat Initiative. 2019. “Central Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free-Zone (CANWFZ).” https://www.nti.org/learn/treaties-and-regimes/central-asia-nuclear-weapon-free-zone-canwz

- Nunatsiaq News. 2014. “European Parliament Calls for Sanctuary around North Pole Area.” March 13. http://www.nunatsiaqonline.ca/stories/article/65674european_parliament_calls_for_protection_of_high_arctic

- Patrick., T. 2018. “China Has More Nuclear Subs Than the West Believed,” DefenseOne, November 20. https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2018/11/china-has-more-nuclear-subs-west-believed/152984

- Prawitz, J. 2010. "A Nuclear Weapon Free Arctic: Arms Control On the Rocks." In Conference on an Arctic Nuclear Weapon Free Zone, edited by C. Vestergaard. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

- Prawitz, J. 2011. “The Arctic: Top of the World to Be Nuclear-Weapon-Free.” Disarmament Forum (2): 27–38. UNIDIR.

- Purver, R. 1983. “The Control of Strategic Anti-Submarine Warfare.” International Journal 38 (3): 409–431. doi:10.1177/2F002070208303800303.

- Rybachenkov, V. 2012. An Arctic Nuclear Weapons Free Zone – A View from Russia. Moscow, Russia: Center for Arms Control, Energy, and Environmental Studies. https://www.armscontrol.ru/pubs/Arctic%20Nuclear%20Weapons%20Free%20Zone.pdf

- Sciutto, J., and Z. Cohen. 2018. “Inside the Nuclear Sub Challenging Russia in the Arctic.” CNN. March 14. https://www.cnn.com/2018/03/14/politics/uss-hartford-nuclear-submarine-arctic/index.html

- Starr, B. “US Submarine Returns from Arctic Mission.” CNN. August 31, 2015. https://www.cnn.com/2015/08/31/politics/uss-seawolf-submarine-navy-arctic/index.html

- Stewart, P., and I. Ali. 2019. “Pentagon Warns on Risk of Chinese Submarines in Arctic.” Reuters, May 3. http://news.trust.org/item/20190502212503-a6q9n

- Thakur, R. 1998. “Stepping Stones to a Nuclear-Weapon-Free World.” In Nuclear Weapons-Free Zones, edited by R. Thakur, 3–32. London: Macmillan and St. Martin’s Press.

- “Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.” 1974. Opened for Signature July 1, 1968. Treaty Series: Treaties and International Agreements Registered of Filed and Recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations 729 (10485): 161–299. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20729/v729.pdf

- US Government Accountability Office. 2018. “Arctic Planning: Navy Report to Congress Aligns with Current Assessments of Arctic Threat Levels and Capabilities Required to Execute DOD’s Strategy.” Report GAO-19-42, November 8. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-19-42

- US Navy. 2019. “The Submarine.” Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.navy.mil/navydata/ships/subs/subs.asp

- Vestergaard, C., ed. 2010. Conference on an Arctic Nuclear Weapon Free Zone. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

- Wallace, M., and S. Staples. March, 2010. Ridding the Arctic of Nuclear Weapons: A Task Long Overdue. Ottawa: Canadian Pugwash Group, Toronto, and Rideau Institute. https://assembly.nu.ca/library/Edocs/2010/001500-e.pdf

- Wezeman, S. T. 2016. “Military Capabilities in the Arctic: A New Cold War in the High North?” SIPRI Background Paper. October. https://www.sipri.org/publications/2016/sipri-background-papers/military-capabilities-arctic

- Wilson Center. 2017. “The Arctic: In the Face of Change, an Ocean of Cooperation,” September 28. https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2017/09/arctic-face-change-ocean-cooperation

Appendix 1

Arctic Search and Rescue Delimitation Map, Arctic Portal Library