ABSTRACT

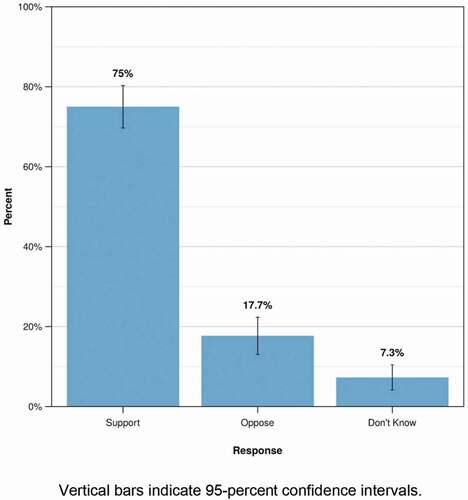

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) poses a challenge to decades of Japanese nuclear policy. While Japan has relied on the US nuclear umbrella since the aftermath of World War II, numerous pro-disarmament groups – including the Hibakusha – are calling for Tokyo to join the Treaty. We contribute to these discussions with commentary on a new national survey we conducted in Japan (N = 1,333). Our results indicate that baseline support for the Prime Minister signing and the Diet ratifying the TPNW stands at approximately 75% of the Japanese public. Only 17.7% of the population is opposed, and 7.3% is undecided. Moreover, this support is cross-cutting, with a wide majority of every demographic group in the country favoring nuclear disarmament. Most strikingly, an embedded survey experiment demonstrates that the Japanese government cannot shift public opinion to oppose the Ban through the use of policy arguments or social pressure. Such broad support for the TPNW indicates that the Japanese government will not be able to hide from the Treaty and must take action to restore its credibility as a leader on nuclear disarmament.

Introduction

In the summer of 2017, a majority of United Nations member states joined together to ban the world’s most powerful weapon. These states built on the momentum of the international movement highlighting the humanitarian impacts of nuclear arms and created the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) (Potter Citation2017; Gibbons Citation2018; Ritchie and Egeland Citation2018). The agreement prohibits states from engaging in all nuclear weapon-related activities, including their possession, helping others build them, and threatening their use. Tellingly, none of the 122 states that voted to adopt the Treaty are nuclear-armed or protected by extended nuclear deterrence.Footnote1 The TPNW thus represents a strong statement of the world’s “nuclear have-nots” against the “nuclear haves.” This dynamic highlights Japan’s longstanding dilemma of seeking to be a leader in the field of nuclear disarmament while relying on the US nuclear umbrella. A majority of Japanese citizens support their country adopting the TPNW, but the United States pressured Tokyo to neither participate in the negotiations nor join the Treaty (Japan Times Citation2017). The administration of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe's rejection of the Ban therefore reflected the position of its American ally that the Treaty will not eliminate a single nuclear weapon and has no means of effective verification (Gibbons Citation2018, Citation2019).

For TPNW supporters, the Treaty is part of a broader strategy aimed at creating a global norm against nuclear weapon possession. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), which was awarded the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize for its role in establishing the TPNW, has long indicated that its mission is to create a groundswell of support against nuclear arms (ICAN Citation2020). ICAN executive director Beatrice Fihn has stated that influencing the way the public views nuclear weapons is integral to this goal (Kurosawa Citation2018; Mekata Citation2018). This position makes it particularly important to evaluate the discrepancies between Japanese government positions and public preferences on the Ban.

The TPNW exacerbates the already delicate nuclear policy balance faced by Tokyo. On one hand, Japan has been an active leader within the global disarmament movement, impelled by the horrors of nuclear use against Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Kurosaki Citation2019). On the other hand, Japan has for decades relied on the US nuclear umbrella and pledges of extended deterrent protection for its national security – a matter of urgency given the continued development of the North Korean nuclear program (Abe Citation2018). Japan’s unique position requires its government to perform what the noted journalist Ota (Citation2018, 94) refers to as a “Nuclear Kabuki Play” through which leaders must simultaneously appeal to their US nuclear patron while supporting domestic pro-disarmament factions. Yet, the Abe administration’s public rejection of the TPNW – against the wishes of many in Japan, including the Hibakusha – means this difficult act is even harder to maintain for the next Japanese government. The TPNW has put disarmament in the spotlight and offers a specific policy request for Japanese disarmament proponents to rally behind. However, as one former official recalled, it was difficult for the Japanese to consider participation with “persistent interference from the United States” (Yoshida Citation2018, 481). Japan’s quandary was exemplified by the government’s decision to attend the opening of the TPNW negotiations, only to publicly denounce the effort and promptly leave (Thakur Citation2018).

Decades of polling dating to the beginning of the atomic age confirm that the Japanese public indeed has a “nuclear allergy” (Tanaka Citation1970; Baron Citation2020) and its government’s position is at odds with the desires of the population. This trend has continued despite increased North Korean nuclear activities and threats against the Japanese homeland. Survey data from Yoimuri Shimbun showed that 80% of the Japanese public supported maintaining former Prime Minister Eisaku Satō’s three non-nuclear principles even in the aftermath of North Korea’s first nuclear explosive test in 2006 (Mochizuki Citation2007). More recently, a 2017 survey indicated that approximately 69% of Japanese would want Japan to remain non-nuclear even if Pyongyang did not denuclearize (Genron NPO and East Asia Institute Citation2017). The public’s strong disapproval of domestic proliferation is especially notable considering Japan’s advanced nuclear energy program and achievement of “nuclear latency” (Fuhrmann and Tkach Citation2015; Mehta and Whitlark Citation2017; Herzog Citation2020). A 2018 nationally representative crisis simulation experiment further revealed that a staggering 85% of the Japanese population would not support US use of nuclear weapons against North Korea, even if that country launched a nuclear strike on Japan (Allison, Herzog, and Ko Citation2019). However, some analysts (e.g. Tomonaga Citation2018) have speculated that national opinion in Japan may be divided over the issue of the TPNW – particularly on a generational basis.

To better contextualize Japanese public attitudes on the emerging nuclear non-possession norm, this commentary reports on new survey data. We describe results from a national Japanese-language survey experiment (N = 1,333) we conducted asking respondents about their support or opposition to the TPNW. At their baseline, the results show that 75% of the Japanese public wants the Prime Minister to sign and the Diet to ratify the Treaty, with only 17.7% opposed and 7.3% undecided. Additionally, no demographic group – whether by age, gender, region of the country, income, or political party identification – opposes the Ban. Perhaps most strikingly, we found that no government critique of the Treaty on security, institutional, or normative grounds can convince the population to oppose the TPNW. Likewise, social pressure is ineffective at attenuating strong pro-disarmament sentiments among the public. Accordingly, we conclude with policy implications for the future of the TPNW, a Treaty that sharply challenges the legitimacy of the Japanese government’s commitment to a nuclear-weapon-free world.

Surveying the Japanese Public

We worked with the global survey research firm Dynata, formerly named Survey Sampling International, to poll a sample of the Japanese public (N = 1,333) about the TPNW from August 9–12, 2019. Our national survey was designed to reflect the demographics of the Japanese population based on age, gender, and prefectural quotas – variables known to correlate with other key population characteristics like political ideology and income. This survey sampling methodology enabled us to make inferences about the views of the Japanese public more generally, as well as among specific demographic groups.

After consenting to participate in the anonymized, Japanese-language Internet survey, respondents provided demographic information before being polled about nuclear disarmament. All subjects were first presented with a paragraph explaining the TPNW, summarizing its key objectives, and noting the number of nations that participated in its negotiation. Respondents were then randomly split into five groups. The first group (N = 260) was immediately asked if they believed Japan should join the Treaty. This enabled us to determine the baseline public opinion on the TPNW. The remaining groups were each randomly assigned to read one of four arguments against the Ban effort before being asked for their opinions about joining the Treaty.

By providing strong criticisms of the TPNW, but along different argumentative lines, these prompts tested the strength of the public’s broader commitment to nuclear disarmament. They also evaluated public receptivity to various rationales to oppose the Treaty. Comparing responses from the four “treatment” groups to those in the baseline group allowed us to assess the relative efficacy of efforts by the Abe administration and other pro-deterrence advocates to sway public attitudes against the Ban. Our work thus builds on a growing body of political science literature using survey experiments to assess public opinion on critical nuclear issues (e.g. Press, Sagan, and Valentino Citation2013; Sagan and Valentino Citation2017; Aronow, Baron, and Pinson Citation2019; Haworth, Sagan, and Valentino Citation2019; Ko Citation2019; Baron and Herzog Citation2020; Rathbun and Stein Citation2020; Sukin Citation2020; Koch and Wells CitationForthcoming).

The four experimental manipulations each tested a different theoretical mechanism for influencing Japanese public opinion about the TPNW. Three of the treatment groups read vignettes reflecting real-world Japanese government arguments encouraging opposition to the Ban on security (e.g. Kono Citation2017), institutional (e.g. Kishida Citation2017), and normative grounds (e.g. Motegi Citation2020). Respondents assigned to the security argument (N = 266) read about how the Treaty might undermine the US nuclear umbrella that protects Japan. The institution argument respondents (N = 271) read that the TPNW was a weak international institution that lacked an effective disarmament verification protocol. The norms argument respondents (N = 279) read a warning that the Ban might compromise the longstanding nuclear norms enshrined in the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) (see e.g. Rublee Citation2009; Budjeryn Citation2015). Finally, the remaining respondents read a fourth perspective which draws on the scholarship of Kertzer and Zeitzoff (Citation2017) by testing if social pressures can affect an individual’s attitudes on foreign policy. This social pressure argument informed respondents that 74% of “those who answered other survey questions like you do not support the Ban Treaty.”Footnote2 Because the social pressure argument employed mild deception, all respondents received a debriefing after the survey informing them of the fictitious nature of treatments.

Taken together, our survey experiment highlighted a number of avenues for learning about Japanese public opinion on the TPNW. It provided a means of assessing baseline public attitudes in Japan among the population as a whole, as well as among important demographic groups. And through its experimental manipulations, it offered insights into whether policy arguments that were made by the Abe administration and social pressures could shift public opinion to be less favorable toward ongoing efforts to ban nuclear weapons.

Japanese Public Views

presents the results of the baseline group in response to the question: “Do you think Japan should join the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty?”Footnote3 We observe high levels of public support for the TPNW: 75% of respondents want Japan to join the Treaty, 17.7% are opposed, and 7.3% remain undecided. This result is consistent with the above historical polling demonstrating that the Japanese public has a pronounced “nuclear allergy” and desires a continued commitment to the three non-nuclear principles. For instance, a recent poll by the NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute (Citation2019) found that 65.9% of respondents supported Japan participating in the TPNW. The small proportion of undecided respondents is also a useful finding for those studying Japanese public opinion on nuclear topics. While surveys on policy preferences conducted in Japan often yield large proportions of “don’t know” or “undecided” responses (Flanagan et al. Citation1991), the relatively low rate of undecided respondents we identified may indicate the high issue salience of the TPNW in Japan.

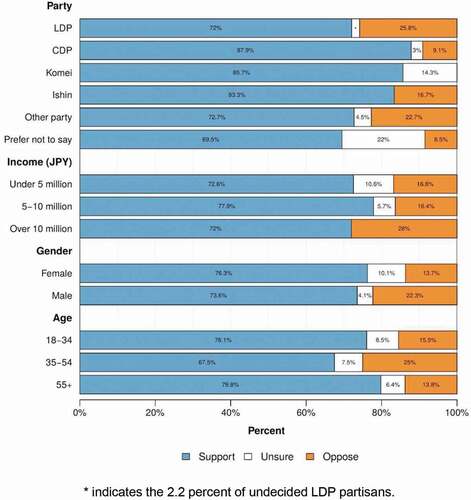

Next, displays how baseline respondents in various demographic groups answered the dependent variable question about Japan joining the TPNW. Our central finding is that support for the Treaty is cross-cutting, with every demographic supporting Tokyo’s membership by a wide majority margin. No group displayed lower than 65% favorability toward the Ban.

Moreover, few systematic differences are apparent across demographic groups. In contrast to Tomonaga’s (Citation2018) expectations, we do not observe differential patterns of support across age groups. Support was also similar for both men (73.6%) and women (76.3%), though more men (22.3%) opposed the Treaty and more women (10.1%) reported uncertainty in their responses. Additionally, little difference was apparent across income brackets. It may appear that wealthier respondents with annual household incomes of over ¥10 million were more certain in their responses. However, the baseline group only included 25 such individuals, so this observation should not be overinterpreted.

While responses were largely indistinguishable among demographic groups, political party identification provided a notable contrast. We found that a significantly larger proportion of Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) supporters approve of the TPNW (87.9%), relative to Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) partisans (72%). This is unsurprising, given the anti-nuclear position of the CDP. On average, Komei (85.7%) and Ishin (83.3%) partisans were also more supportive of the TPNW than LDP partisans.

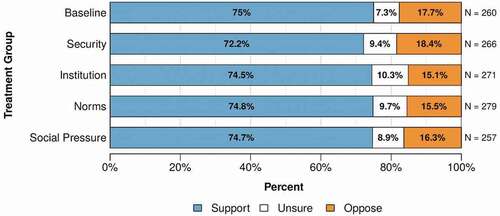

Finally, presents the distributions of responses in each of our four experimental manipulations relative to the baseline Japanese public opinion. It is evident that respondents’ attitudes did not shift in response to any of the randomly assigned arguments against the TPNW. Among all groups, the proportion of supportive respondents remained between 72–75%, with between 15–18.5% opposed. Furthermore, none of the differences in responses compared to the baseline are statistically significant. The lack of any observed effects of the arguments we tested highlights the robustness of Japanese public attitudes opposing nuclear weapons and supporting disarmament. Public opinion remained immobile, even in response to a variety of strong, realistic arguments against the TPNW.

This finding is all the more remarkable when taken in contrast to results from a parallel survey experiment conducted in the United States (Herzog, Baron, and Gibbons CitationForthcoming). Unlike the Japanese public, American attitudes toward the Ban shifted substantially in response to each persuasive argument. In the case of the institution and security arguments, support dropped by nearly 20 percentage points relative to the baseline. Interestingly, this contrast dovetails with the results of another study testing the effects of persuasive messaging about nuclear weapons and nuclear energy with parallel survey experiments in Japan and the United States (Baron Citation2020). Members of the Japanese public showed considerable resistance to persuasion in that study as well, while Americans could be persuaded to shift their opinions regarding each technology.

Policy Implications

Our polling and survey experimental results indicate that, as expected, the Japanese population strongly favors the TPNW. More importantly, the population does not appear to be swayed by typical security, institutional, and normative-based arguments made by governments against the Treaty. Efforts to apply social pressure also do not appear to be a successful strategy for countering the Ban movement in Japan. These findings make it abundantly clear that the Treaty will continue to challenge Japanese leaders into the future. In other words, Japanese leaders cannot hide from the TPNW.

In most states protected by extended nuclear deterrence, there is little public debate about nuclear weapons. This is simply not the case in Japan. Every August, the nation’s attention is drawn to memorializing the victims of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings; at this time, local officials, Hibakusha, and members of the public will almost certainly continue to call for their government to support the TPNW. Outside of these commemorations, the public will be prompted to consider nuclear disarmament at a series of junctures: when each new state ratifies the TPNW, when the Treaty reaches 50 ratifications and enters into force, when the States Parties meet, and when each NPT Preparatory Committee and Review Conference meeting takes place. The Treaty will provide a persistent reminder of the divide between what a significant segment of the population wants and what their government is actually doing in terms of disarmament. Over time, the Japanese government’s stated commitment to nuclear disarmament may ring hollow, and our research suggests that pro-deterrence officials have little power to shift public opinion against the TPNW. Future leaders might therefore decide that a reassessment of Japan’s position is necessary, either on the basis of principled politics or a desire to reap domestic political gains.

For the moment, the Abe administration’s consistent rejection of the Ban has cast a shadow of doubt over Japan’s desired role as a bridge-builder between nuclear-armed states and non-nuclear states (see e.g. Tomonaga Citation2018). The Japanese population is calling for a concrete policy action of joining the TPNW, and our data highlight the widespread nature of public support for this proposition. Consequently, the successor to the Abe administration will likely need to undertake serious additional efforts to restore its domestic credibility on nuclear disarmament if it seeks to avoid the TPNW. Such measures could include efforts to mediate between the nuclear-armed states in order to move forward efforts to reduce global nuclear weapons, or perhaps Japan could invest heavily in becoming a world leader in a specific area such as nuclear security or verification. Other concessions to public opinion would also send powerful signals to domestic interest groups. For example, perhaps the government might consider sending a Japanese diplomatic delegation to the first meeting of the States Parties after entry-into-force of the TPNW.

Meanwhile, ICAN, Japanese supporters of the Treaty, and States Parties should be heartened by the remarkable depth of the population’s commitment to nuclear disarmament. This is notable since support for the TPNW remains so robust at a time when Japan is concerned about North Korea’s aggressive nuclear and missile program. Japan appears to be a country whose population would be highly receptive toward the ICAN strategy of galvanizing public opinion against pro-deterrence leadership. It makes sense that this is the case for Japan given its unique history as the target and victim of the atomic bombings. Highlighting the Hibakusha has been a critical element in the success of the humanitarian impacts movement to discredit nuclear weapons as a legitimate means of providing security. It is important for supporters of a world free of nuclear weapons to continue to pass down their stories not only in Japanese society, but also to spread them globally.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for various comments and support from Peter M. Aronow, Maki Eida, Yuki Hayasaka, Tyler Jost, Martin B. Malin, Benoît Pelopidas, Frances Rosenbluth, Hibiki Yamaguchi, and Fumihiko Yoshida.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials and related research data for this article may be accessed from Yale University’s Institution for Social and Policy Studies [ISPS Data Archive ID D155]: https://isps.yale.edu/research/data/D155.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jonathon Baron

Jonathon Baron is a recent PhD graduate in political science from Yale University. A survey research specialist, his work focuses on public opinion regarding nuclear energy and nuclear weapons in Japan and the United States. He completed this research as a US–Asia Grand Strategy Fellow at the University of Southern California’s Korean Studies Institute. Jonathon was previously a fellow of the Yale Project on Japan’s Politics and Diplomacy. He also holds an MA and MPhil from Yale, and a BA from the University of Chicago, all in political science. His research is published or forthcoming in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Energy Research & Social Science, the Journal of Politics, the Nonproliferation Review, Political Analysis, and The National Interest.

Rebecca Davis Gibbons

Rebecca Davis Gibbons is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Southern Maine and a postdoctoral research fellow with the International Security Program/Project on Managing the Atom of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Her research focuses on the nuclear nonproliferation regime, arms control, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, and global order. She holds a PhD in government and an MA in international security from Georgetown University, and a BA in psychological and brain sciences from Dartmouth College. After college, she taught elementary school within the Bikini community on Kili Island in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Her academic writing is published or forthcoming in Comparative Strategy, the Journal of Global Security Studies, the Journal of Politics, the Journal of Strategic Studies, the Nonproliferation Review, Parameters, and The Washington Quarterly. Her public affairs commentary has been featured in Arms Control Today, The Hill, US News & World Report, War on the Rocks, and the Washington Post/Monkey Cage.

Stephen Herzog

Stephen Herzog is a PhD candidate in political science at Yale University and a Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow with the International Security Program/Project on Managing the Atom of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. His research focuses on nuclear arms control, deterrence, and proliferation. Stephen was previously a fellow of the Yale Project on Japan’s Politics and Diplomacy and a Worldwide Support for Development–Handa Fellow with the Pacific Forum, Center for Strategic and International Studies. Before returning to academia, Stephen worked as an arms control and nonproliferation specialist for the US Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration and the Federation of American Scientists. He holds an MA and MPhil in political science from Yale, an MA in security studies from Georgetown University, and BA in international relations from Knox College. His academic writing is published or forthcoming in Energy Research & Social Science, International Security, the Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, the Journal of Politics, and the Nonproliferation Review. His public affairs commentary has been featured in Arms Control Today, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the Financial Times, The Hill, The National Interest, War on the Rocks, and the Washington Post/Monkey Cage.

Notes

1 Among the beneficiaries of nuclear protection, only the Netherlands participated in the TPNW negotiations.

2 The prompt read: 下のグラフは、この調査を既に受けた人の回を示しています。他の質問に対しあなたと同様の回答をした人は、核兵器禁止条約を支持しません。

3 The question read: あなたは日本が核兵器禁止条約に加入するべきだと思いますか?

References

- Abe, N. 2018. “No First Use: How to Overcome Japan’s Great Divide.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1 (1): 137–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2018.1456042.

- Allison, D. M., S. Herzog, and J. Ko. 2019. “Under the Umbrella: Nuclear Crises, Extended Deterrence, and Public Opinion.” Paper presented at the 2019 International Studies Association Annual Convention. Toronto.

- Aronow, P. M., J. Baron, and L. Pinson. 2019. “A Note on Dropping Experimental Subjects Who Fail a Manipulation Check.” Political Analysis 27 (4): 572–589. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.5.

- Baron, J. 2020. “Mass Attitudes and the Relationship Between Nuclear Technologies.” PhD dissertation, Yale University.

- Baron, J., and S. Herzog. 2020. “Public Opinion on Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapons: The Attitudinal Nexus in the United States.” Energy Research & Social Science 68 (101567): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101567.

- Budjeryn, M. 2015. “The Power of the NPT: International Norms and Ukraine’s Nuclear Disarmament.” Nonproliferation Review 22 (2): 203–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2015.1119968.

- Flanagan, S. C., S. Kohei, I. Miyake, B. M. Richardson, and J. Watanuki. 1991. The Japanese Voter. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Fuhrmann, M., and B. Tkach. 2015. “Almost Nuclear: Introducing the Nuclear Latency Dataset.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 32 (4): 443–461. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894214559672.

- Genron NPO, and East Asia Institute. 2017. “The 5th Japan–South Korea Joint Public Opinion Poll (2017): Analysis Report on Comparative Data.” Accessed 19 April 2020. http://www.genron-npo.net/en/archives/170721_en.pdf

- Gibbons, R. D. 2018. “The Humanitarian Turn in Nuclear Disarmament and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.” Nonproliferation Review 25 (1–2): 11–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2018.1486960.

- Gibbons, R. D. 2019. “Addressing the Nuclear Ban Treaty.” Washington Quarterly 42 (1): 27–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1590080.

- Haworth, A. R., S. D. Sagan, and B. A. Valentino. 2019. “What Do Americans Really Think about Conflict with Nuclear North Korea? The Answer is Both Reassuring and Disturbing.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 75 (4): 179–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2019.1629576.

- Herzog, S. 2020. “The Nuclear Fuel Cycle and the Proliferation ‘Danger Zone’.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 3 (1): 60–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2020.1766164.

- Herzog, S., J. Baron, and R. D. Gibbons. Forthcoming. “Anti-Normative Messaging, Group Cues, and the Nuclear Ban Treaty.” Journal of Politics.

- International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. 2020. “The Campaign.” Accessed 20 April 2020. https://www.icanw.org/the_campaign

- Japan Times. 2017. “Trump Administration Opposes Japan’s Participation in U.N. Talks on Banning Nukes.” March 16. Accessed 22 April 2020. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/03/16/national/politics-diplomacy/trump-administration-opposes-japans-participation-u-n-talks-banning-nukes/#.XqDbHchKg2w

- Kertzer, J. D., and T. Zeitzoff. 2017. “A Bottom-up Theory of Public Opinion about Foreign Policy.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (3): 543–558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12314.

- Kishida, F. 2017. Statement of Japan at the First Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2020 NPT Review Conference. Vienna, Austria. May 2. Accessed 22 April 2020. https://www.vie-mission.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_en/FM_Kishida_NPT_Statememt_en.html

- Ko, J. 2019. “Alliance and Public Preference for Nuclear Forbearance.” Foreign Policy Analysis 15 (4): 509–529. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/ory014.

- Koch, L. L., and M. S. Wells. Forthcoming. “Still Taboo? Citizens’ Attitudes toward the Use of Nuclear Weapons.” Journal of Global Security Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogaa024.

- Kono, T. 2017. Press release on the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). December 10. Accessed 22 April 2020. https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press4e_001837.html

- Kurosaki, A. 2019. “Japan’s Nuclear Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Diplomacy During the Cold War: The Myth and Reality of a Nuclear Bombed Country.” In Joining the Non-Proliferation Treaty: Deterrence, Non-Proliferation and the American Alliance, edited by J. Baylis and Y. Iwama, 131–150. London: Routledge.

- Kurosawa, M. 2018. “Stigmatizing and Delegitimizing Nuclear Weapons.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1 (1): 32–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2017.1419453.

- Mehta, R. N., and R. E. Whitlark. 2017. “The Benefits and Burdens of Nuclear Latency.” International Studies Quarterly 61 (3): 517–528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx028.

- Mekata, M. 2018. “How Transnational Civil Society Realized the Ban Treaty: An Interview with Beatrice Fihn.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1 (1): 79–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2018.1441583.

- Mochizuki, M. M. 2007. “Japan Tests the Nuclear Taboo.” Nonproliferation Review 14 (2): 303–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700701379393.

- Motegi, T. 2020. Press release on the 50th anniversary of the entry into force of the NPT. May 5. accessed 22 April 2020. https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press1e_000145.html

- NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute (NHK 放送文化研究所). 2019. “December 2019 Political Awareness Monthly Survey (2019 年 12月政治意識月齢調査).” NHK Public Awareness Monthly Survey (政治意識月齢調査). Accessed 21 April 2020. https://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/yoron/political/pdf/y201912.pdf

- Ota, M. 2018. “Conceptual Twist of Japanese Nuclear Policy: Its Ambivalence and Coherence under the US Umbrella.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1 (1): 193–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2018.1459286.

- Potter, W. C. 2017. “Disarmament Diplomacy and the Nuclear Ban Treaty.” Survival 59 (4): 75–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2017.1349786.

- Press, D. G., S. D. Sagan, and B. A. Valentino. 2013. “Atomic Aversion: Experimental Evidence on Taboos, Traditions, and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons.” American Political Science Review 107 (1): 188–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000597.

- Rathbun, B. C., and R. Stein. 2020. “Greater Goods: Morality and Attitudes toward the Use of Nuclear Weapons.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (5): 787–816. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002719879994.

- Ritchie, N., and K. Egeland. 2018. “The Diplomacy of Resistance: Power, Hegemony and Nuclear Disarmament.” Global Change, Peace & Security 30 (2): 121–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2018.1467393.

- Rublee, M. R. 2009. Nonproliferation Norms: Why States Choose Nuclear Restraint. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Sagan, S. D., and B. A. Valentino. 2017. “Revisiting Hiroshima in Iran: What Americans Really Think about Using Nuclear Weapons and Killing Noncombatants.” International Security 42 (1): 41–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00284.

- Sukin, L. 2020. “Credible Nuclear Security Commitments Can Backfire: Explaining Domestic Support for Nuclear Weapons Acquisition in South Korea.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (6): 1011–1042. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002719888689.

- Tanaka, Y. 1970. “Japanese Attitudes Toward Nuclear Arms.” Public Opinion Quarterly 34 (1): 26–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/267770.

- Thakur, R. 2018. “Japan and the Nuclear Weapons Prohibition Treaty: The Wrong Side of History, Geography, Legality, Morality, and Humanity.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1 (1): 11–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2018.1407579.

- Tomonaga, M. 2018. “Can Japan be a Bridge-Builder between Deterrence-Dependent States and Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty Proponents?” Medicine, Conflict and Survival 34 (4): 289–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2019.1565099.

- Yoshida, F. 2018. “From the Reality of a Nuclear Umbrella to a World without Nuclear Weapons: An Interview with Katsuya Okada.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1 (2): 474–485. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2018.1516113.