ABSTRACT

This paper motivates and sketches a set of nuclear-use cases involving conflict on the Korean peninsula. The cases reflect a wide range of ways that nuclear weapons might be brandished or used in a Korean crisis. We identify possible cases by using two different lenses: a “logical” or taxonomic lens and a decisionmaking lens that asks how an actual national leader might decide to use nuclear weapons first. We then select cases from the space of possibilities to reflect that range usefully. The use cases consider mistakes, unintended escalation, coercive threats, limited nuclear use to reinforce threats, defensive operations, and offensive operations. They also consider the potential role of fear, desperation, responsibility, grandiosity, indomitability, and other human emotions. Some use cases are far more plausible than others at present, but estimating likelihoods is a dubious activity. The real challenge is to avoid circumstances where the use cases would become more likely.

Introduction

In this paper we develop a number of hypothetical nuclear-use cases (what are often called scenarios) in a Korean conflict for application in a larger project. Our intent is to provide insights about how and why nuclear war could occur and, thus, about circumstances to be avoided.

Reasons For Use Cases

Generic Purposes

Use cases provide concreteness for discussion, debate, and evaluation. They serve many purposes as illustrated in .

Table 1. Some reasons for use cases

Thinking About The Unthinkable

A paper identifying use cases should engage in what Herman Kahn called “thinking about the unthinkable” (Kahn Citation1962). It should avoid the temptation to ignore a use case because it seems unlikely or because its discussion is controversial. The empirical record of assessing the likelihood of bad events is poor, even by experts (Tetlock Citation2017). Readers who are more optimistic about being able to estimate likelihoods should recall that, as late as 2010, there was no sense within American expert circles that Russia would soon be a significant military threat again for NATO – that is, that it would seize Crimea, occupy part of Ukraine, and pose a danger to the Baltic states. Also, readers might ask how plausible it seemed in the mid-1990s that the United States and some NATO allies would invade the sovereign state of Iraq in 2003, arguably in violation of the UN charter (Murphy Citation2004). Also, how likely did it seem in 2011 that Syria would use chemical weapons in its civil war, despite US warnings about red lines?

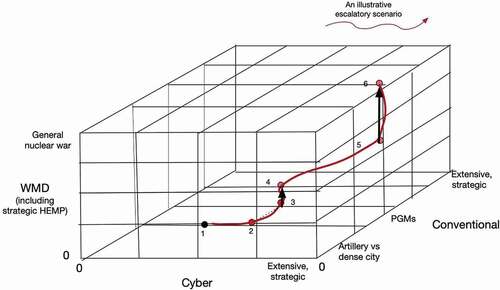

Thinking about the unthinkable has become more challenging as high-end war has expanded to include massive long-range precision fires; cyberwar, anti-satellite weapons; high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) bursts; and mass-destruction attacks by chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons. An escalation “lattice” may be a better metaphor than ladder and we should recognize that antagonists will see levels of conflict differently (Davis Citation2017).

Opportunities abound for misperceptions and misjudgments in crisis and conflict. Although high-level wargames during the Cold War with players akin to civilian national leaders (“elite wargames”) showed extreme reluctance to use nuclear weapons (Pauley Citation2018), the boundaries among conflict levels have blurred. In some wargames today, highly competitive players (not necessarily proxies for policymakers) will escalate in ways that seem to them limited but that appear otherwise to the adversary.

This complexity is illustrated in , which reduces the n-dimensional escalation space to a three-dimensional cube. For the illustrative case, war begins conventionally (item 1). A major cyberattack against the United States (item 2) leads to more extensive and strategic US use of precision weapons (item 3), which leads the adversary to limited chemical, biological, or nuclear use (item 4). That leads to more comprehensive use of precision weapons and limited nuclear use (item 5) and, finally, general nuclear war (item 6). The possibilities are even more numerous than with Herman Kahn’s 44-rung escalation ladder.

In contemplating Korea-related escalation possibilities, we have drawn on a recent report (Bennett et al. Citation2021, 39–58), which in turn drew on the literature about North Korean military capabilities and operations plans, and on testimony by and interviews with high-level escapees from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). We also drew on earlier work about instability on the Korean peninsula (Davis et al. Citation2016).

Approach In Identifying Use Cases

We looked for use cases in two ways: (1) asking about types of first use by thinking logically and perhaps taxonomically and (2) asking how a human decision maker might be thinking when actually deciding to use nuclear weapons first. Viewing issues through these two lenses would lead to different results, albeit with overlap.

Types of First Use

identifies three types of first use: peacetime mistakes, previously unintended escalation in conflict (matters getting out of control), and intentional first use.

Mistakes

The potential for peacetime mistakes in managing nuclear weapons or interpreting warning data has long been a concern because so many errors have in fact occurred. Some of these matters were discussed decades ago (Blair Citation1985; Sagan Citation1993). A harrowing account based on declassified documents covers the 3 June 1980 event in which the US warning system led to a middle-of-the night call to the President’s National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski. A second call corroborated the attack. Just as Brzezinski was about to call President Carter – determined that the United States must retaliate – a third call declared a false alarm (Gates Citation1996, 114). Had random events been slightly different, general nuclear war might well have begun.

Serious errors in Soviet early warning systems have also occurred, as with the Petrov incident in 1983 (Hoffman Citation1999). President Yeltsin was briefed during a 1995 false-alarm episode in which a Norwegian scientific rocket was reported as attacking the Soviet Union. His “nuclear football” was activated before it was recognized that this was a false alarm (Union of Concerned Scientists Citation2015).

Mistakes have also included operational blunders, such as when the US Air Force inadvertently flew nuclear weapons across the country. The mistakes caused Secretary of Defense Robert Gates to fire top Air Force leaders (Shanker Citation2008) and to create a special task force co-chaired by ex-Defense Secretaries to review nuclear management (Schlesinger et al. Citation2008a, Citation2008b).

A variant of the “mistakes” category involves misperceptions more than technical glitches. An example was the 1983 “War Scare” during NATO’s Abel Archer exercise. President Andropov was already obsessed with the possibility of a US nuclear attack. The exercise, which included NATO preparing for nuclear release as part of defeating a Warsaw Pact attack, was then viewed with alarm by some Soviets – a degree of alarm unrecognized by the United States, later dismissed as false propaganda (Central Intelligence Agency Citation1984), and still later described as authentic and worrisome (PFIAB Citation1990). The PFIAB report discusses possible reasons for Moscow’s alarm. For example, leaders saw themselves as much more vulnerable to a first strike that Western analysts assumed, relations with the United States were bad, there were health and old-age problems among leadership, and certain “live” aspects of the NATO exercise went beyond usual command-and-control exercising (PFIAB Citation1990, 38 ff). Secretary of Defense Robert Gates concluded in his memoirs that:

I don’t think the Soviets were crying wolf. They may not have believed a NATO attack was imminent in November 1983, but they did seem to believe that the situation was very dangerous. And U.S. intelligence [SNIE 11–9-84 and SNIE 11–10– 84] had failed to grasp the true extent of their anxiety. (Gates Citation1996, 273)

Fritz Ermarth, the author of the earlier 1984 assessment, held with the view that the war scare had been exaggerated (Ermarth Citation2003). That now seems to be the case, especially when folding in information from Russian sources (Miles Citation2020), but it is easy to imagine how one or a few additional events and misperceptions might have triggered disaster.

Unintended Escalation

When Plans Don’t Work Out as Intended

The second major branch of refers to unintended escalation, the result of things getting out of hand. An important element here is that when forces are put on high alert, mistakes can occur or actions may be taken that were not intended by earlier planning. Officers in the field suffering severe losses may be inclined to use whatever mechanisms they possess to avert immediate disaster. Such possibilities increase as weapons are deployed and authority is delegated. They increase further when military forces are prepared to respond quickly to enemy escalation.

A famous example almost occurred in the Cuban Missile Crisis. Despite conventional Cold War wisdom being that Soviet leadership maintained tight control on nuclear weapons via the KGB, Soviet leadership had in fact pre-delegated nuclear authority to the commander in Cuba because of a well-deserved Soviet fear of US invasion. Also, submarine commanders had nuclear torpedoes with launch authority, although with the requirement for agreement among key officers. None of this was recognized by American decisionmakers as they discussed options and operational procedures. The US Navy dropped small depth charges to force the surfacing of submarines. One of the submarines had lost communications with Moscow and its crew was exhausted and stressed. According to a Soviet officer’s later account, the boat’s top officers disagreed about whether to launch a nuclear torpedo. The submarine’s commander at one point said “We’re gonna blast them now! We will die, but we will sink them all – we will not become the shame of the fleet”. Fortunately, unanimity among top officers was necessary and views of the senior officer, the flotilla Commander, prevailed. The submarine surfaced without further incident (Burr and Blanton Citation2002). Matters could easily have played out differently.

As mentioned above, the Soviet ground commander also had nuclear weapons and pre-delegated authority (later remanded) to use some of them in defense (Fursenko and Timothy Citation1997, 242–43)Footnote1 Had the United States invaded Cuba – as some advisors urged – nuclear weapons might have been used without at-the-time approval by central Soviet authorities.

Unintended escalation might also occur in conflict situations due to failures of command and control, misperception, errors by misbehavior of lower-level officers, or accidents in the field.

A new problem related to unintended escalation is the advent of artificial intelligence (AI). The use of AI is inevitable but is also ominous when combined with the belief that extremely fast decisions are necessary. Defenses against missiles may indeed depend on actions within minutes and defenses against cyberattacks may indeed depend on actions taken within milliseconds. The demand for speed may introduce a bias toward escalation (Wong et al. Citation2020).

Intentional First Use of Nuclear Weapons

Continuing in , let us turn now to the possibility of planned first use. In some ways, deliberate use of nuclear weapons is more plausible now than it has been since early in the Cold War (Bracken Citation2012; National Research Council Citation2014).

Coercion

Coercive Threats to Use Nuclear Weapons. As merely one example, the DPRK might as a provocation seize a small portion of the Republic of Korea’s (ROK’s) territory, brandish their nuclear weapons, and threaten to use them if the ROK or United States made a military response (Bennett et al. Citation2021, 43). Or, on a more grandiose scale, the DPRK might threaten to attack the ROK unless the ROK ended its alliance with the United States, demanded that the United States pull out its forces, and declared its new friendly relationship with the North. This is implausible today, but such a threat will become less implausible as the DPRK extends and improves its intercontinental delivery capabilities against the United States, as well as its nuclear capabilities generallyFootnote2 Bluntly, the quality of the US nuclear extended deterrent is doubtful. Moreover, it depends on the President at a given time and political context. This point was foreseen well before the DPRK developed its ICBM capability (Davis et al. Citation2016). Subsequently, then candidate Donald Trump made clear that he was uncomfortable with the nuclear-umbrella idea (Sanger and Haberman Citation2016).

Ironically, such coercion could be even more plausible after a “good” period gone sour – one in which the United States and ROK had foregone joint exercises and US forces had been drawn down as part of normalizing the peninsula. In such circumstances – depending on details of the process and its history – the perceived credibility of the US nuclear extended deterrent might be especially low.

As an aside, it would hardly be surprising if the ROK chose to develop its own nuclear deterrent, whether or not the United States continued to oppose such a development. Further, it is conceivable that a future President – Democratic or Republican – would even agree to such a development, overtly or covertly. Richard Nixon reportedly acquiesced to Israel’s nuclear program in 1969 so long as it was not publicly acknowledged (Cohen and Burr Citation2006). That has apparently remained US policy (Entous Citation2018).

Historical Examples of Coercion by Nuclear Threat. The literature includes numerous historical examples of how the United States allegedly used nuclear threats to deter or coerce (Norris and Kristensen Citation2006). In 1946 the United States demanded that the Soviet Union withdraw its forces from Iran, which it did. President Truman claimed to have threatened Stalin with nuclear weapons (Time Citation1980), although whether he actually did so is doubtful (Samii Citation1987). Dwight Eisenhower’s comments about nuclear weapons during the 1952 campaign may have helped influence the Chinese to end the Korean war. Certainly, as of 1953, military plans existed to use nuclear weapons if war resumed on the Peninsula (Gwertzman Citation1984).

Actual Use As Part of Coercion

Continuing in , we can envision circumstances in which first nuclear use would occur as a way to show determination after mere threats had been ignored.

As mentioned above, perhaps at some point the DPRK would feel emboldened to try coercing the ROK and the United States to make major concessions regarding territory, sovereign waters, US-ROK exercises, US forces in the ROK, the DPRK’s status in world affairs, or other matters. If so, what might such circumstances be? Military power matters and the DPRK is increasing the number and diversity of its nuclear capabilities rapidly (Gentile et al. Citation2019; Bennett et al. Citation2021). Human considerations also matter as discussed in Section 3.

An even more against-the-grain speculation is that, perhaps after unsuccessful coercion but in a context that made backing down impossible politically, the DPRK might invade the ROK, attempting to achieve quick and decisive victory well before the United States could mobilize and deploy forces for effective warfighting on the Korean Peninsula. Reportedly, DPRK Chairman Kim Jong Un became convinced in 2012 that conventional victory would be impossible, causing him to approve development of a fast-moving plan that would use nuclear weapons for “asymmetric attacks” (Jeong and Ser Citation2015; Bennett et al. Citation2021, 50). Some of this is corroborated by high-level escapee Yong-Ho Thae, now an elected representative to the South Korean National AssemblyFootnote3 It is unclear what might trigger such a reckless attack, but it is significant that the DPRK has such a military plan. Another possibility is that, in the event of an internal crisis threatening Kim’s control, the DPRK might initiate war as a diversion and a call for unity. Yong-Ho Thae has said that the primary fear in the DPRK government is no longer a threat from the United States and ROK, because of the DPRK’s nuclear deterrent, but rather the threat of collapse from within – due to pressures from the millennium generation of citizens who know a great deal about the ROK, the United States and the world via the Internet. In his view, they are interested in materialism, not ideology, and see much to like elsewhereFootnote4 To be sure, other authors claim that the Kim regimes have had internal matters well under control (Byman and Lind Citation2010; Kim and Choi Citation2021) and that no internal collapse is plausible. Kim and Choi even refer to the collapse scenario as a fallacy or even a mythology. And yet Kim Jong-un has himself said that ROK pop culture is “a ‘vicious cancer’ corrupting young North Koreans’ ‘attire, hairstyles, speeches, behaviors’”. His state media has warned that if left unchecked, it would make the DPRK “crumble like a damp wall” (Choi Citation2021).Footnote5

Operational Defense

Perhaps a more likely intentional first use of nuclear weapons would be defensive once war had begun for some reason. In the 1950s, the United States drew up plans for nuclear attack of China in the event of war defending the Taiwanese Islands Quemoy and Matsu. President Eisenhower approved only mounting a conventional defense, but the nuclear plans might well have come into play if China had not backed off.

In a war, it is conceivable that a losing side would initiate nuclear use either to counter advances of the opponent due to its use of long-range precision fires (the United States) or chemical or biological weapons (DPRK). Both sides might contemplate nuclear use in response to a debilitating (or merely dramatic) military success by the adversary.

An important case here is when one nation invades another with the expectation of quick victory, the defender defends bravely but is about to collapse, and the defender then escalates in the hope of re-establishing deterrence. It had not “intended” to do so, but had planned for the possibility. Such thinking was explicit in NATO doctrine during the Cold War.

Russia has developed an analogous concept referred to in the West as escalate-to-de- escalate (Roberts Citation2015; Davis et al. Citation2019, 26–25 (by Edward Geist)). NATO interprets this concept as meaning that if Russia attempted to seize one of the Baltic states, and if NATO’s response were sufficiently effective so that Russia began to lose, Russia might use nuclear weapons to raise the stakes so as to salvage its ill-gotten gains. Russia disputes that interpretation, emphasizing that its resort to nuclear weapons would be defensive, and undertaken only when the very existence of the Russian state was in jeopardy (Putin Citation2015).

As a different way to appreciate how matters could get out of hand, we might consider the 1983 Proud Prophet war game. In 1983 the Reagan administration was seeking to be tougher in its dealings with the Soviet Union, responding to what was seen as Soviet preparations to fight and win a nuclear war. Going into the exercise, which involved a Warsaw Pact invasion of Europe, senior leaders apparently anticipated tough moves by NATO (including very limited nuclear use) leading to termination with Soviet aggression having been stopped. However, in the words of an observer, Paul Bracken:

The game went nuclear big time, not because Secretary Weinberger and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs were crazy but because they faithfully implemented the prevailing U.S. strategy (Bracken Citation2012, 93).

The plan included limited nuclear use as NATO’s defenses crumbled, which use the Soviets (or rather the exercise’s Red Team) did not perceive as NATO intended. The Soviets responded massively, which led to general nuclear war and a half-billion deaths. We might draw some conclusion from this and other data points.

Sobering Lessons

The content of war plans matters, even though – in theory – political leaders may override them if doing so is realistically feasible, and if enough time exists to enforce such a decisionFootnote6

National leaders and local commanders feel the responsibility to allow their military forces to defend themselves. This may include using nuclear weaponsFootnote7

Despite having long been downplayed in US and NATO circles, battlefield nuclear weapons can in some cases be effective militarily, albeit with consequences in terms of fallout (Fursenko and Timothy Citation1997, 242–43)Footnote8 See also comments of Lt. General Odom (US Army, retired) when discussing the 1964 Warsaw Pact war plan (Odom Citation2000) in a retrospective.

With this background, it is significant that – as mentioned above – the DPRK reportedly has a war plan for a seven-day strategy that includes significant first use of nuclear weapons for decisive military effect (Jeong and Ser Citation2015), presumably with the belief that the United States lacks the stomach for high-casualty war.Footnote9 Existence of such plans does not imply anything about national intentions, confidence in the plan’s success, or the likelihood of execution. It does, however, indicate what must be considered plausible events in warFootnote10 If situations deteriorate and leaders turn to their military for next actions, those will likely involve existing plansFootnote11

Yet another kind of unintended escalation might come about after one state used mere conventional weapons (for example, some combination of long-range precision fires, cyberattack, and counter-satellite attacks) in a way that “forced” the adversary to use nuclear weapons because of having no good alternative. A variant might be if an adversary, such as the DPRK, felt “compelled” to employ chemical or biological weapons on US or ROK forces because it lacked the ability to cope with US conventional weapons and perceived that the United States had no appropriate response to such useFootnote12 The United States might then feel “compelled” to use nuclear weapons to retaliate or to show resolve, preclude DPRK victory, or both.

Invasion

For completeness we should mention the possibility of a straightforward DPRK invasion to unify the peninsula. That, however, seems implausible in the foreseeable future given the weaknesses of the DPRK military and other factors. Although instructions from Kim Jong Il to his son emphasize unification as the ultimate goal of the family (Bennett et al. Citation2021, 3; Jeong Citation2013), the instructions do not suggest urgency, and in fact proscribe achieving unification via war with the ROK. Still, this is the scenario that DPRK military planning appears to be based on (Jeong and Ser Citation2015).

Preemption And Preventive War

Certainly plausible is what would be seen as a preemptive nuclear attack in anticipation of a devastating attack or invasion by the adversary. The DPRK has raised this possibility numerous times over the years and, from a purely logical perspective, it is not inconceivable that the United States and ROK would use nuclear weapons in a first strike intended to preemptively head off war about to be initiated by the DPRK. Many see this as absurd because of more general US military capabilities that would seem to make nuclear use unnecessary, but suppose that a decapitation attack was considered essential and that success was seen to require nuclear weapons because of uncertainties about the location of DPRK leadership or the ability to kill the leadership in those locations with conventional weaponsFootnote13 Or, more prosaically, nuclear weapons might be recommended simply because they would improve confidence in actually destroying the targets intended. Even if such an attack currently appears implausible to US and South Korean readers, it may not seem so to North Korean readers. Consider yet another possibility, that US forces are not yet available in the region for effective operations dependent on precision conventional fires, that a DPRK attack is imminent, and that it is perceived as likely to succeed. Or, imagine that war has already begun with a successful surprise attack on a US aircraft carrier that kills hundreds or thousands of sailors, destroys some command-and-control facilities, and/or neutralizes the Guam air base. Is it truly evident that no US President would respond with nuclear weapons?

Terminal Missile Defense

As a last item in , consider intentional nuclear first use as part of missile defense. Conventional wisdom in the West holds that nuclear-tipped defenses would be counterproductive and ineffective, but judgments can change. As recently as 2002, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld asked that the potential value of nuclear-tipped interceptor be reviewed (Graham Citation2002). If the goal were to maximize US strategic defense against an actual nuclear attack by the DPRK, recognizing that even one or a few leakers could do catastrophic damage, the alleged virtues of terminal defense with nuclear-tipped interceptors might well be rediscovered because doubts remain about defense effectiveness and because even the best systems leak. Such doubts will increase markedly if the DPRK develops penetration aids, multi-warhead missiles, and/or EMP weapons (Pry Citation2021). Such developments could occur much faster than conventional wisdom suggestsFootnote14 Finally – although minimal information exists on the matter (Harris Citation2020) – the possibility exists of the DPRK deploying ICBMs with biological weapons that would be released as bomblets early in flight, making defense extremely difficult. The feasibility of that has been credibly asserted with supporting designs that address both the release mechanism and shielding from heat during reentry (Garwin Citation1999; Rumsfeld Citation1998; Sessler et al. Citation2000, 49 ff). The Soviets had a large bioweapons program with warheads for ICBMs (Alibek and Handelman Citation1999; Leitenberg and Zilinskas Citation2012). It is also of interest that Kim Jong Il’s final instructions to his son referred to development of biochemical weapons. According to a newspaper account of this DPRK document provided by a North Korean escapee (Jeong Citation2013), one admonition was:

Keep in mind that the way to maintain peace on the Korean Peninsula is to endlessly develop nuclear, long-range missiles and biochemical weapons and possess a sufficient number of them. Don’t ever be caught off guard.

It is seldom possible, of course, to fully authenticate such accounts of DPRK documents. Still, these other developments might occur much faster than commonly expected.

In the meantime, Russia maintains nuclear-tipped ballistic-missile defense of MoscowFootnote15

Human Factors In Decisions to Employ Nuclear Weapons

As a second lens through which to identify possible nuclear-use cases, let us now consider the human decision to employ nuclear weapons first in a conflict. The human considerations have been given relatively short shrift over the decades (National Research Council Citation2014)Footnote16 We touch upon some here in the overlapping categories of (1) fear; (2) fatalism or grandiosity; and (3) mental and physical health.

Fear And Desperation

As famously discussed by Robert Jervis (Jervis Citation1976) and others, it is common for adversaries to fear each other and not comprehend how their own actions cause fears in their counterparts. This can lead to a security dilemma. During the Cold War, Soviet officials feared attack by NATO, despite that seeming irrational to NATO. The United States feared a surprise first strike by the Soviets, even though that seemed irrational to the Soviets, who believed that any preemptive strike on their part would be to head off an imminent US strike, and would come after a lengthy build-up of tensions, not as a bolt from the blue.

Although the DPRK has often been the aggressor in provoking crisis (CSIS Citation2019), it has also had reason to fear attack by the United States.Footnote17 This was the case at points in the 1970s and 1990s, and even more so after the Axis of Evil speech by President George W. Bush (Bush Citation2002), followed by a book co-authored by his speechwriter elaborating on the United States having a window of opportunity for dealing with rogue states (Frum and Perle Citation2004).

Fatalism, Grandiosity, and Related Factors

Other ways in which a decisionmaker might direct use of nuclear weapons could be through some combination of fatalism, grandiosity, a sense of indomitability, or revenge. People are obviously not always rational – despite the nominal assumptions of some economists, decision theorists, and textbooks. Some historical examples may be instructive.

Grandiosity

Some accounts describe Hitler as having talked about dying in a dramatic cataclysm that brought down others. Hitler related himself to Jesus and the Messiah and, in discussing dying in battle, said that his death would be inspirational:

We shall not capitulate … no, never. We may be destroyed, but if we are, we shall drag a world with us … a world in flames … we should drag half the world into destruction with us and leave no one to triumph over Germany. There will not be another 1918.Footnote18

As for Korea, a well-known story in the DPRK describes Kim Il Sung praising his son Kim Jong Il for answering a question about what to do if the United States attacked and the DPRK lost the war. Kim Jong Il reportedly said:

I will be sure to destroy the Earth! What good is the Earth without North Korea? (STET Citation2009)

How we should interpret this story is unclear, but the DPRK government encourages that the story be told, perhaps because of its deterrent value (Bennett et al. Citation2021, 44). Even if merely a form of propaganda, the sentiment expressed is peculiar and notable.

Fatalism And Revenge

As a very different example of how “non rational” considerations may sometimes come into play, we might consider the case of Israel. The actual status of Israel’s nuclear capability, if any, remains classified, but its nuclear program has been called a public secret because so much information is now available in declassified documents indicating that “by 1975 the United States was convinced that Israel had nuclear weapons” (Aftergood and Kristensen Citation2007).

Israel reportedly has its Samson Option – a plan to attack its enemies with nuclear weapons if Israel is being overrun (Hersh Citation1991). The name alludes to the Biblical account of Samson bringing down a Philistine temple upon himself and Philistine captors. Although recognizing deterrence as the primary motivation for Israel’s nuclear program, Hersh quotes one former Israeli official with firsthand knowledge of the program. The person was expressing the view that the United States could not be counted on and had backed down during the Suez Crisis in the face of the Soviet nuclear threat. He went on to tell Hersh:

We got the message. We can still remember the smell of Auschwitz and Treblinka. Next time we’ll take all of you with us.

If war were to mean ultimate doom, a “rational” response might be surrender, but people have often behaved otherwise over the millennia, as famously recorded in the Melian Dialogue of ancient Greece (Thucydides and Moses Citation1976).

Indomitability

However realistic or unrealistic one believes such apocalyptic endings to be, we are all familiar with the real-world relevance of the Chicken Game in which two 1950s teenage males approach each other with hot rods on a road at high speeds, neither willing to give way because to do so would be to show less courage and to be labeled subsequently as a chickenFootnote19 The ultimate demonstration of indomitability, suggested by Thomas Schelling, is when one protagonist tears off his steering wheel so as show that he cannot veer away (it is unclear how, in the real world, one visibly tears off a steering wheel, but that is a mere detail)Footnote20

The relevance may be seen by imagining that the nuclear-armed DPRK attempts coercion by demanding that the ROK surrender and promise fealty. Suppose that the DPRK threatens to annihilate San Francisco if the United States joins the ROK in military resistance. If a hubris-dominated DPRK leader perceives the ROK and President as rational but weak, he might truly expect capitulation – if not initially, then after an initial round that vaporized one or more cities in the ROK and the United StatesFootnote21 We suspect that such a DPRK leader would prove wrong: it might be more likely for a President to “stand tall” and unleash a massive attack despite the consequences.

Responsibility And Desperation

One important effect of emotions can be a preeminent focus on discharging responsibility under desperate circumstances. This was discussed late in the Cold War in a monograph asking how, really, nuclear war might begin – as distinct from it beginning as the result of some power calculation. Two speculative possibilities were (Davis Citation1989)

Use-or-Lose, Coupled with Responsibility. During a superpower crisis, an SSBN commander has lost communications with the homeland, is under trail by a hunter- killer submarine, and feels a deep patriotic responsibility to launch his missiles (before being sunk)Footnote22

Desperation. In an extremely tense superpower crisis, a nation’s leader is told by military authorities that – despite past assertions and conventional wisdom – it may not be possible to ride out a first strike and retaliate: “Sir, despite what you’ve heard, our command and control would probably fail and we would be paralyzed. Since general nuclear war is inevitable and the adversary is preparing a first strike, the only chance for national survival (however small) is to conduct a first strike. Perhaps, with luck, the attack will disconnect and paralyze the adversary’s command and control system.”

Mental And Physical Health

Much is known today about how mental health, substance abuse, and other leader- specific matters arose in Cold War crises, as when President Nixon was badly intoxicated at key points in the 1973 Arab-Israeli crisis and when President Yuri Andropov had an almost paranoid fear of a US first strike in the early 1980s (Burr Citation2016).

Even earlier, in WWII, Hitler was a heavy user of strong drugs such as oxycodone (a painkiller) and cocaine. These allowed him to overcome pain, ignore bad news from the front, and project grandiose and rigid optimism. Hitler felt that the drugs allowed him to “be himself” – i.e. to project commanding presence, certainty, and indomitabilityFootnote23

A Factor Tree For A Nuclear Decision Incorporating Human Factors

One qualitative mechanism for reflecting actor-specific considerations is to construct qualitative cognitive models that highlight factors that might loom large in leaders’ thinking as they contemplate actions such as nuclear first-use. The method dates back to work on Saddam Hussein prior to and during the 1990–1991 Persian Gulf war (Davis and Arquilla Citation1991; NRC Citation1996).

Factor trees can be important elements of cognitive models. They show the factors affecting a decision or development as an approximate tree with factors arrayed in layers of detail. First introduced in modeling for counterterrorism, they have been used in a number of contexts where social-science theory should come into play (Davis and O’Mahony Citation2017). is an example suggesting circumstances under which a national leader might decide on first use of nuclear weapons. In such figures, if some nodes are connected by “ands”, it means that all factors must typically be present to a significant degree; if nodes are connected by “ors” (or by nothing), they may substitute for or complement each other. Ordinarily, if one node points to another, it means that more of the former tends to increase the latter (or decrease it, if the sign is negative).

Figure 3. DPRK deciding to use nuclear weapons.

Prominent in and related depictions are concepts such as fear, desperation, visceral competitiveness, indomitability, and fatalism, as well as misperceptions exacerbated by such well-studied psychological phenomena as cognitive biases (Kahneman Citation2011). Many of these have been discussed in connection with international affairs by Robert Jervis (Jervis Citation1976, Citation2017).

To better understand the intent of , recall that the intent is to find possible flows of reasoning that support nuclear use. It is not a prescription for how decisionmakers should think, nor a depiction of a cold, objective calculation using cost-benefit analysisFootnote24 Nor is it our best guess about how Kim Jong Un would reason. Rather, it is an attempt to depict the kind of human reasoning that could lead to nuclear use. What would possess someone to actually initiate nuclear war? Better understanding this should help in identifying actions to make that reasoning less likely, as illustrated in a recent study about possible Chinese aggression against Taiwan (Davis et al. Citation2021).

With this background, describes the four top-level factors for decision as motivation (for the nuclear option in question), legitimacy, prospects for success, and acceptability of other benefits and risks. This is deliberately different from a breakdown in terms of pros and cons, or a breakdown in terms of how to calculate net utility. Again, is a cognitive model, an attempt to depict something more like the reasoning that might go on in a real decisionmaker’s head (a stream of reasoning that we want to avoid). In this depiction, we should read the figure left to right: given reasons (motivations) for use of nuclear weapons – is such use legitimate? Are prospects for success for good? And, if so, would the costs be tolerable? Readers will recognize that all of us sometimes reason in a similar manner, starting with the desire to do something. This can lead to a bias toward action.

Working through the figure, let us look first at motivation. This might be a notion of getting positive benefit, as in causing the adversary’s capitulation The motivation might, however, be of a more negative nature: fear of imminent loss or failure to accomplish a sacred mission. Yet another contributor to motivation might be desire for revenge: perhaps the war is already lost, but the leader feels the need to take the adversary down with him (perhaps in a moment of glory). Moving rightward, an important factor is likely to be the perceived absence of good alternatives. Note the “ors”, which mean that any of these motivating factors might be sufficient for a given decisionmaker at a given time.

Given motivation for nuclear use, a leader might worry about whether nuclear use would be legitimate. Again, the contributing factors in are connected by “ors”, meaning that the nuclear option might be justified with any one of a number of rationalizations, the most obvious being a sense of necessityFootnote25 In the case of the DPRK, the leader might feel a solemn obligation to fulfill the Kim-family dream of unifying the peninsula. He or she might also see decisive nuclear use as likely to unify people in the ultimate battle. As for international legitimacy, if considered at all, the issue might be whether – however critical other nations might be initially – they would come to accept the outcome.

However motivated the leader might be, an important factor would be perceived prospects for success. In sufficiently dire circumstances, the perception might include wishful thinking about the ability to achieve victory quickly because of weakness in the US or ROK leadership or other factors. Or it might be relatively sober, accounting for relative military strengths, the difficulty in actually achieving victory, and so on. Which factors would dominate would depend on personalities and details.

The final factor in the cognitive model is whether the price to be paid for nuclear use is acceptable. In principle, as in a cost-benefit calculation or standard deterrence theory, this factor might rule out the nuclear option. Cognitively, however, real decisionmakers might have a bias toward action and a tendency to underestimate the true costs. In particular, there might be a tendency to assume or hope that the nuclear war would be containable (for example, with quick capitulation of the United States and ROK), in which case negative consequences such as casualties would be distinctly limited.

We should mention one other crucial feature of : the node values need not be best estimates. To the contrary, in some circumstances (such as impending doom) the decision may be more in the nature of grasping-at-straws, as when there is at least a chance that success will occur and costs will be tolerable.

In summary, can help us identify reasoning patterns with limited rationality leading to nuclear use. Nations should want to avoid the circumstances in which such thought patterns might be generated.

Illustrative Use Cases

Drawing on the discussion of the previous two sections, we can now consider a range of plausible nuclear-use cases, interpreting “plausible” broadly to anticipate circumstances and leaders different from those that obtain today. An infinite variety is possible but we can attempt to illustrate the range.

does so for cases of DPRK first-use. It draws distinctions relating to context, whether emotions are strongly in play, and types of nuclear use. Instead of specifying particular numbers, types, or targets for nuclear weapons, the last several columns anticipate that the use cases should necessarily be parametric. Even in the same context and with the same generic objective, the leader directing first use of nuclear weapons could make very different choices.

Table 2. Summary of Illustrative DPRK First-Use Cases

Some particular issues to consider when defining variations of use cases are

Would an attacker spare a particular city or area to make the adversary’s surrender more plausible and avoid destroying high-value facilities that it might otherwise gain?

Would an attacker constrain weapon use to minimize damage from radiation and fire? That might make the adversary’s surrender more plausible and increase the benefits of victory.

Would an attacker destroy the adversary’s strategic command and control system or, to the contrary, assure its continued viability so as better to communicate and so as to assure the adversary’s ability to draw down its forces if it succumbs?

How, if at all, would high-altitude electromagnetic pulse shots (HEMP) be used?Footnote26 What effects would be expected by its user and what effects might actually occur?

has some speculative instances of American first use of nuclear weapons. These are consistent with discussion in earlier sections that postulate instances in which – despite many years of claims that nuclear weapons are useful only for responding to the adversary’s nuclear use – the US President might conceivably find first use necessary.

Table 3. Illustrative Use Cases with US Initiation (Highly Speculative)

Conclusions

We have identified and motivated a range of use cases for thinking about how nuclear war might start in a Korea context, drawing on both logical/taxonomic reasoning and a kind of cognitive modeling sensitive to emotions and other human foibles. The cases identified are not equally plausible, but estimating likelihoods is a foolish game to play with a poor empirical record. It is more useful, in our view, to see the identified use cases as ways for things to go very badly so that ways can be found to prevent the corresponding circumstances from arising. Humility is appropriate because of the complexity of real-world command and control and weapon systems, which cannot be realistically tested.

Appendix A: Illustrating Planning Tensions in Nuclear Planning

During the Cold War, nuclear planners often encountered strongly felt and widespread

beliefs.

Convenient but Unjustified Beliefs

Any nuclear war will escalate to general nuclear war, so it is unnecessary to consider limited nuclear war.

Deterring or otherwise avoiding nuclear war is the only objective; planning for instances in which deterrence fails may encourage thinking about nuclear warfighting, which should be discouraged (see item 1).

All relevant national leaders will understand the unacceptable consequences of nuclear war: catastrophic massive losses of life and destruction of societies.

Heated arguments arose when developing official formal objectives, as one of us (Davis) remembers well. Everyone could agree on deterrence as an objective, but what about an objective in the form “In the event that deterrence fails, … ”? Any such objective was bitterly controversial. Whether to include if-deterrence-fails objectives had to be resolved by top policymakers, such as Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski.

The inadequacy of these common beliefs weighed heavily on defense Secretaries Laird, Richardson, Rumsfeld, and Brown – a mix of three Republicans and one Democrat. After years of study, the conclusion by 1980 was that US nuclear forces should be able to deter not just Soviet leaders who read and agreed with American textbooks on deterrence, but also possible leaders who might even believe that it remained possible to fight and win a nuclear war.

The result was the Countervailing Strategy, which included plans for ICBM

modernization, a new type of nuclear weapon (air-launched cruise missiles), and a targeting doctrine that envisaged destruction of the Soviet Communist Party’s organs of power, even if that meant attacking leaders in underground shelters, so as to prevent recovery. The intent was to convince even the most hawkish of Soviet military leaders that the Soviet Union could not “win” a nuclear war even on its own military-technical terms (Brown Citation2012; Slocombe Citation1981).

The strategy was not well received by the academic community and is barely mentioned in some textbooks about nuclear strategy. In others, it is described as bellicose and destabilizing. It was interpreted by some as about “how to fight a nuclear war” (Burr Citation2012). That accusation was enough to generate a rebuttal from Harold Brown (Brown Citation2012), one paragraph of which stands out for its enduring relevance.

First, I remain highly skeptical that escalation of a limited nuclear exchange can be controlled, or that it can be stopped short of an all-out, massive exchange. Second, even given this belief, I am convinced that we must do everything we can to make such escalation control possible, that opting out of this effort and resigning ourselves to the inevitability of such escalation is a serious abdication of the awe- some responsibilities nuclear weapons, and the unbelievable damage their uncontrolled use would create, thrust upon us.

If Brown reached this conclusion about the need to think about limited nuclear war when dealing with the Soviet Union, then surely a similar conclusion about the need to plan for the event that deterrence fails is even more imperative for a world in which limited nuclear war is more plausible than is a US-Soviet conflict. As the DPRK increases the size and scope of its nuclear arsenal, the need to do so will only increase.

*This paper is prepared for Reducing the Risk of Nuclear Weapons Use in Northeast Asia (NU-NEA), a project co-sponsored by Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University (RECNA), Asia Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament (APLN) and Nautilus Institute with collaboration of Panel on Peace and Security of Northeast Asia (PSNA). Additional funding is provided by the MacArthur Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The research described in this paper was supported by The Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul K. Davis

Paul K. Davis is a professor of policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School and a retired adjunct Senior Principal Researcher at RAND. He received a B.S. in chemistry from the University of Michigan and a Ph.D. in chemical physics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He worked in strategic warning technology and systems analysis before joining the US government to work on strategic force planning and arms control. As a Senior Executive, he then headed analysis of global military strategy and related defense programs in the Office of Program Analysis and Evaluation. He then joined the RAND Corporation, where his research has dealt with strategic planning under deep uncertainty; deterrence theory; modeling; information fusion; and causal social science for policy applications. He has served on numerous national panels and journal editorial boards. He developed and conducted a prescient nuclear-crisis war game in Seoul in 2016. His most recent major work (co-edited) is Social Behavioral Modeling for Complex Systems (2019), Wiley & Sons.

Bruce W. Bennett

Bruce W. Bennett is a professor in the Pardee RAND Graduate School and a retired adjunct International/Defense Researcher at The RAND Corporation. He is an expert in Northeast Asian security issues, having visited the region about 120 times and written much about Korean security. His research addresses issues such as DPRK military threats (especially WMD), negotiating DPRK nuclear dismantlement, future ROK military force requirements, Korean unification, the Korean military balance, and potential Chinese military intervention in North Korea. He has facilitated a large number of seminars/war games to address these issues. His latest report is Countering the Risks of North Korean Nuclear Weapons. Dr. Bennett received a Ph.D. in policy analysis from the Pardee RAND Graduate School and a B.S. in economics from the California Institute of Technology.

Notes

1 Scholars still debate about the extent of the predelegation, if any, whether it was formally communicated, and whether it matters given that there were no physical controls from Moscow. Details continue to emerge (Plokhy Citation2021).

2 Projections of North Korean nuclear capabilities vary (Bennett et al. Citation2021, 36–39; Hecker Citation2021). The differences don’t matter here because even the lower estimates (Hecker Citation2021) anticipate the DPRK having scores of nuclear weapons (75 by 2026) – enough to use some weapons tactically and operationally, while holding in reserve enough weapons for attack of cities in the United States, South Korea, and Japan.

3 Jong-Ho Thae was the DPRK’s deputy ambassador to the UK when he defected in 2016. In a presentation, Thae acknowledged Kim Jong Un’s conclusion about the need to use nuclear weapons and to focus efforts of nuclear and missile development (Thae Citation2020). He also noted that the DPRK still has a policy of unifying the peninsula by force.

4 This is discussed at about 6:50 minutes into a presentation (Thae Citation2020). See also an interview conducted by Laignee Barron (Barron Citation2019).

5 A White House meeting on 25 August 1958 included the decision (Halperin Citation1966, 113)

“In the event a major attack seriously endangers the Offshore Islands, prepare to assist the GRC [Taiwan] including attacks on coastal air bases. It is probable that initially only conventional weapons will be authorized, but prepare to use atomic weapons to extend deeper into Communist territory if necessary.”

6 Many changes are not feasible quickly. Among the depressing items in declassified Cold-War materials is that, as of 2003, the US President did not have city-withhold options and the option to reject launch-on-warning procedures (Burr Citation2016). See also discussion by Franklin Miller in a memoir by General Lee Butler (Butler Citation2016, 189–456). It would be unwise to assume that the DPRK or the US/ROK alliance has easily-controlled limited military options other than, perhaps, something purely demonstrative, such as blowing up an Island or demonstrating an air burst.

7 In planning related to Cuba in 1962, we know from Soviet sources that the Soviet thinking was “any recourse to military power in Cuba would likely entail the use of nuclear weapons” (Freedman and Michaels Citation2019, 215). This was so despite Khrushchev having no intention of war (Freedman and Michaels Citation2019, 241).

8 Fursenko and Naftali estimate that General Rommel could have destroyed all five beachheads of the Normandy invasion with perhaps ten nuclear weapons such as those available to the Soviet commander in Cuba during the 1962 crisis (Fursenko and Timothy Citation1997, 242–243).

9 Some escapee testimony indicates that DPRK leadership believes that the United States is no longer prepared to carry out a conflict with high levels of attrition and as a result would withdraw from such a conflict after suffering 20,000 casualties or so, rather than continue a disastrous war (Bennett et al. Citation2021, xii). To be sure, such escapee accounts are usually second or third hand, or reflect documents that cannot be authenticated, rather than direct evidence from the actual North Korean leaders.

10 This ambiguity about what the existence of plans means has historical precedents. Warsaw Pact operations plans called for broad and immediate first use of nuclear weapons (Parallel History Project (PHP) Citation2000). Major disagreements existed within NATO about what the Warsaw Pact would actually do. Were the plans real and were those who expected restraint practicing wishful thinking, or was the intelligence wrong because – in the event – wiser minds would prevail (Nuclear Planning Group Citation1974)? Some would argue that the Proud Prophet exercise was misleading, ending as it did only because the Red Team was overly influenced by Soviet doctrine.

11 Arguments about whether to lay plans for limited nuclear war go back to the Cold War as discussed in Appendix A.

12 Some senior ROK officers believe that the United States should be explicit about intent to respond to chemical use with nuclear use. Otherwise, they see no deterrent to the DPRK’s chemical use.

13 To cite a US National Academy report, “Many of the more important strategic hard and deeply buried targets are beyond the reach of conventional explosive penetrating weapons and can be held at risk of destruction only with nuclear weapons” (NRC Citation2005, 1).

14 A recent Department of Homeland Security (DHS) report makes assertions unusual in an official document “The West consistently and unwittingly cooperates with North Korea by underestimating the advancement, sophistication, and strategic implications of North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile programs. Thus, under the nose of the U.S. Intelligence Community, North Korea surprised the world by demonstrating ICBMs that could target any city in the United States and a hydrogen bomb in the summer of 2017. Reportedly, in 2017 US Intelligence Community analysts also revised sharply upward their estimated number of North Korean nuclear weapons from about 20 to 60 and also concluded North Korea can miniaturize warheads for missile delivery – facts some Western analysts are still unwilling to face” (Pry Citation2021, 5).

15 Some observers have suggested prohibiting nuclear interceptors (Lewis Citation2012).

16 See Appendix E of National Research Council (Citation2014) for actor-specific characterization factors. The primary author was Jerrold Post, who founded the profiling group of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (Post Citation2008; Post and Doucette Citation2019).

17 See Park (Citation2014) for a comparison of North and South Korean perspectives when thinking about unification.

18 This is cited in Davis et al. (Citation2016, 19, fn 27), referring to a 1943 profile of Hitler developed for the Office of Strategic Services (Langer Citation1943).

19 Bertrand Russell gave a mordantly humorous depiction in 1959 (Russell Citation2001, xviii).

20 Colin Camerer applies game theory to national politics (Akpan Citation2019), illustrating how bizarre political behaviors can be rooted in a kind of logic.

21 We refer to a generic “DPRK leader” because Kim Jong Un appears quite rational and – despite theatrical rhetoric in exchanges with President Donald Trump – does not appear to suffer from grandiose hubris. It was noteworthy that, upon testing to ICBM range and thereby demonstrating the ability to attack the United States, Kim immediately launched his version of a charm offensive and put a hold on further overt testing. It appeared that he was willing to recognize success and try to move on to political and economic priorities (Hecker, Carlin, and Serbin Citation2018), signs of very sensible behavior. For related discussion, see Spetalnick, Brunnstrom, and Walcott (Citation2019).

22 The 1995 movie Crimson Tide (starring Gene Hackman and Denzel Washington), had an analogous premise. Further, as mentioned earlier, something similar happened in the Cuban Missile Crisis when the US Navy dropped depth charges to force a Soviet submarine to surface without knowing that it had nuclear torpedoes. (Burr and Blanton Citation2002).

23 Much of this comes from a German novelist’s account (Ohler and Whiteside Citation2018), based on papers of Hitler’s personal physician. Some reviews dispute the account (Evans Citation2016).

24 Textbooks often argue that deterrence is achieved when the adversary perceives that the expected gains are not worth the expected costs. That discussion misses important elements of limited rationality (National Research Council Citation2014, 35–38).

25 President Harry Truman justified the A-bomb attacks on Japan as necessary to avoid losing perhaps a half-million additional Americans in a bloody invasion (Stimson Citation1946) with Japanese fighting to the end, as in Iwo Jima. Revisionist historians have been critical about these explanations (Bernstein Citation2015) and note additional strategic reasons played a role, notably keeping the Soviet Union out of the war.

26 HEMP options are controversial. A DHS report reviews evidence from the alarmist perspective. It asserts that North Korea already has EMP weapons and that Kim Jong Un talks about them (Pry Citation2021). A journalistic article discusses the disagreements (Barrett Citation2017), quoting scientists skeptical about HEMP effects. A technical report concludes that HEMP could cause serious disruption but not nationwide long-lasting blackouts (Horton Citation2019). A critical response to that followed (Stuckenberg et al. Citation2019). Our view is that the effects might in fact prove grievous because US infrastructure was not designed to be adequately robust and spare parts are often not available for many months. Further, even temporary effects might be seen as devastating, a trigger for escalation. Thus, we reject arguments dismissing the significance of HEMP, even though it would be very risky for an attacker to count on it having the effects estimated.

References

- Akpan, N. 2019. “How the Shutdown Might End, according to Game Theory.” PBS News Hour, January 17, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/how-the-shutdown-might-end-according-to-game-theory

- Alibek, K., and S. Handelman. 1999. Biohazard. Random House.

- Barrett, B. 2017. “North Korea’s Plenty Scary without an Overhyped EMP Threat.” Wired, November 1, 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/north-korea-emp-threat/

- Barron, L. 2019. “‘Materialism Will One Day Bring Change’. Why a Senior Defector Believes North Korea’s Days are Numbered’ [An Interview with Thae Yong-ho].” Time, September 18.

- Bennett, B. W., Kang Choi, Myong-Hyun Go, Bruce E. Bechtol, Jiyoung Park, Bruce Klingner, and Du-Hyeogn Cha. 2021. Countering the Risks of North Korean Nuclear Weapons. Santa Monica Calif: RAND Corp. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA1015-1.html

- Bernstein, B. J. 2015. “Reconsidering Truman’s Claim of ‘Half a Million American Lives’ Saved by the Atomic Bomb: The Construction and Deconstruction of a Myth.” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, September 15.

- Blair, B. 1985. Strategic Command and Control: Redefining the Nuclear Threat. Washington, D.C: Brookings.

- Bracken, P. 2012. The Second Nuclear Age: Strategy, Danger, and the New Power Politics. New York: Times Books.

- Brown, H. 2012. “Rebuttal: A Countervailing View: No We Did Not Think We Could Win A Nuclear War.” Foreign Policy, September 24.

- Burr, W. 2012. “How to Fight a Nuclear War.” Foreign Policy, September 14.

- Burr, W. edited by. 2016. “Briefing Book #575: Reagan’s Nuclear War Briefing Declassified.” December 22, 2016. https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/nuclear-vault/2016-12-22/reagans-nuclear-war-briefing-declassified

- Burr, W., and T. S. Blanton. edited by. 2002. “The Submarines of October: U.S. And Soviet Naval Encounters during the Cuban Missile Crisis.” National Security Archive Project, George Washington University. October 31, 2002. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB75/

- Bush, G. W. 2002. “State of the Union Address.” White House, January 29, 2002. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2002/01/20020129-11.html

- Butler, G. L. 2016. “Uncommon Cause: A Life at Odds with Convention.” In Volume II: The Transformative Years. Outskirts Press.

- Byman, D., and J. Lind. 2010. “Keeping Kim: How North Korea’s Regime Stays in Power.” In Quarterly Journal. International Security, Policy Brief.

- Central Intelligence Agency. 1984. Special National Intelligence Estimate: SNIE 11-10-84/JX: Implications of Recent Soviet Military-Political Activities. Office of the Historian, US Department of State.

- Choi, S.-H. 2021. “Kim Jong-Un Calls K-Pop a ‘Vicious Cancer’ in the New Culture War,” New York Times, June 10, 2021.

- Cohen, A., and W. Burr. 2006. “Israel Crosses the Threshold.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 62 (3): 22–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.2968/062003008. May 2006.

- CSIS. 2019. Database: North Korean Provocations. Washington, D.C: Center for Strategic & International Studies.

- Davis, P. K. 1989. Studying First-Strike Stability with Knowledge-Based Models of Human Decision Making, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R3689.html

- Davis, P. K. 2017. Illustrating a Model-Game-model Paradigm for Using Human Wargames in Analysis, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR1179.html

- Davis, P. K., and J. Arquilla. 1991. Deterring or Coercing Opponents in Crisis: Lessons from the War with Saddam Hussein. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R4111.html

- Davis, P. K. and P. Bracken. 2022. ”Artificial intelligence for Wargaming and Modeling,” Journal of Defense Modeling & Simulation. https://doi.org/10.1177/15485129211073126

- Davis, P. K., J. Kim, Y. Park, and P. A. Wilson. 2016. “Deterrence and Stability for the Korean Peninsula.” Korean Journal of Defense Analyses 28 (1): 1–23.

- Davis, P. K., and A. O’Mahony. 2017. “Representing Qualitative Social Science in Computational Models under Uncertainty: National Security Examples.” Journal of Defense Modeling and Simulation 14 (1): 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1548512916681085.

- Davis, P. K., A. O’Mahony, C. Curriden, and J. Lamb. 2021. Influencing Adversary States: Quelling Perfect Storms, Santa Monica Calif.: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA161-1.html

- Davis, P. K., Paul K., J. Michael Gilmore, David R. Frelinger, Edward Geist, Christopher K. Gilmore, Jenny Oberholtzer, and Danielle C. Tarraf 2019. Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, Santa Monica Calif.: RAND Corp. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2781.html

- Entous, A. 2018. “How Trump and Three Other U.S. Presidents Protected Israel’s Worst-Kept Secret: Its Nuclear Arsenal.” The New Yorker, June 2018.

- Ermarth, F. W. 2003. “Observations on the ‘War Scare’ of 1983 from an Intelligence Perch.” In Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw Pact (PHP): Stasi Intelligence on NATO edited by B. Schaefer and C. Nuenlist.

- Evans, R. J. 2016. “Review of “Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany by Norman Ohler”.” The Guardian, November 16, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/nov/16/blitzed-drugs-in-nazi-germany-by-norman-ohler-review

- Freedman, L., and J. Michaels. 2019. The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy: New, Updated and Completely Revised (4th Ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Frum, D., and R. Perle. 2004. An End to Evil: How to Win the War on Terror. Ballantine Books.

- Fursenko, A. A., and J. N. Timothy. 1997. One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964. New York: Norton.

- Garwin, R. L. 1999. “Technical Aspects of Ballistic Missile Defense,” in Proceedings of APS Forum on Physics and Society, unpaged.

- Gates, R. 1996. From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider’s Story. New York: Simon & Shuster.

- Gentile, G., Yvonne K. Crane, Dan Madden, Timothy M. Bonds, Bruce W. Bennett, Michael J. Mazarr, and Andrew Scobell. 2019. Four Problems on the Korean Peninsula: North Korea’s Expanding Nuclear Capabilities Drive a Complex Set of Problems. Santa Monica Calif: RAND Corp. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL271.html

- Graham, B. 2002. “Nuclear-Tipped Interceptors Studied,” Washington Post, April 11, 2002.

- Gwertzman, B. 1984. “U.S. Papers Tell of ‘53 Policy to Use A-Bomb in Korea,” New York Times, June 8, 1984, Section A, 8.

- Halperin, M. H. 1966. The 1958 Taiwan Strats Crisis: A Documented History [Declassified]. Santa Monica Calif: RAND Corp. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_memoranda/RM4900.html

- Harris, E. 2020. North Korea and Biological Weapons: Assessing the Evidence. Washington, D.C: 38 North, Stimson Center.

- Hecker, S. S. 2021. ““Estimating North Korea’s Nuclear Stockpiles: An Interview with Siegfried Hecker”, 18 North.” Stimson Center, April 30, 2021. https://www.38north.org/2021/04/estimating-north-koreas-nuclear-stockpiles-an-interview-with-siegfried-hecker/

- Hecker, S. S., R. L. Carlin, and E. A. Serbin. 2018. A Comprehensive History of North Korea’s Nuclear Program: 2018 Update. Stanford, Calif: Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation.

- Hersh, S. M. 1991. The Samson Option: Israel’s Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy. New York: Random House.

- Hoffman, David E. 2009. The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy. London: Knopf Doubleday.

- Horton, R. 2019. High-Altitude Electromagnetic Pulse and the Bulk Power System Potential Impacts and Mitigation Strategies. Palo Alto, Calif: Electric Power Reacrch Institute.

- Jeong, Y.-S. 2013. “Kim Jong-Il’s Final Orders: Build More Weapons,” Korea JoongAng Daily (in association with New York Times), January 29, 2013. https://www.38north.org/2021/04/estimating-north-koreas-nuclear-stockpiles-an-interview-with-siegfried-hecker/

- Jeong, Y.-S., and M.-J. Ser. 2015. “Kim Jong-Un Ordered a Plan for a 7-Day Asymmetric War.” Korea JoongAng Daily, January 7, 2015. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2015/01/07/politics/Kim-Jongun-ordered-a-plan-for-a-7day-asymmetric-warofficials/2999392.html

- Jervis, R. 1976. Perception and Misperception in International Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jervis, R. 2017. How Statesmen Think: The Psychology of International Politics. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

- Kahn, H. 1962. Thinking about the Unthinkable. New York: Horizon Press.

- Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Kim, S. K., and E.-J. Choi. 2021. “The Fallacy of North Korean Collapse.” 38 North, February 1, 2021. https://www.38north.org/2021/02/the-fallacy-of-north-korean-collapse/

- Langer, W. C. 1943. A Psychological Analysis of Adolph Hitler: His Life and Legend [Part of the Nizkor Project]. Office of Strategic Services (Predecessor of CIA).

- Leitenberg, M., and R. A. Zilinskas. 2012. The Soviet Biological Weapons Program: A History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lewis, Jeffrey. 2012. “Banning Nuclear-Armed ABMs.” October 18 , https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/205820/banning-nuclear-armed-abms/

- Miles, S. 2020. “The War Scare that Wasn’t: Able Archer 83 and the Myths of the Second Cold War.” Journal of Cold War Studies 22 (3): 86–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00952.

- Murphy, S. D. 2004. “Assessing the Legality of Invading Iraq.” Georgetown Law Journal 92 (4).

- National Research Council. 2005. Effects of Nuclear Earth-Penetrator and Other Weapons. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

- National Research Council. 2014. U.S. Air Force Strategic Deterrence Analytic Capabilities: An Assessment of Methods, Tools, and Approaches for the 21st Century Security Environment. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press.

- Norris, R. S., and H. M. Kristensen. 2006. “U.S. Nuclear Threats: Then and Now.” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists 62 (5): 69–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.2968/062005016. September 2006.

- NRC. 1996. Post-Cold War Conflict Deterrence. Washington, D.C: National Research Council and Navy Studies Board.

- Nuclear Planning Group. 1974. Warsaw Pact Politco-Military Strategy and Military Doctrine for the Tactical Use of Nuclear Weapons, NPG/Study/45 [previously NATO Secret]. Brussels: NATO.

- Odom, W. E. 2000. “Comment on the 1964 Warsaw Pact War Plan.” In Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw Pact, 29–32. Washington, D.C./Zurich: PHP Publications Series.

- Ohler, N., and D. Whiteside. translator. 2018. Blitzed: Drugs in the Third Reich. MH Books.

- Parallel History Project (PHP). 2000. “Taking Lyon on the Ninth Day? the 1964 Warsaw Pact Plan for a Nuclear War in Europe and Related Documents”.

- Park, Y. H. 2014. “South and North Korea’s Views on the Unification of the Korean Peninsula and Inter-Korean Relations,” in Proceedings of 2nd KRIS-Brookings Joint Conference on “Security and Diplomatic Cooperation between ROK and US for the Unification of the Korean Peninsula, unspecified.

- Pauley, R. 2018. “Would U.S. Leaders Push the Button? Wargames and Sources of Nuclear Restraint”. International Security 43 (2): 151–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00333.

- PFIAB. 1990. “The Soviet “War Scare”.” President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb533-The-Able-Archer-War-Scare-Declassified-PFIAB-Report-Released/2012-0238-MR.pdf

- Plokhy, S. 2021. Nuclear Folly. W.W. Norton.

- Post, J. M., ed. 2008. The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press.

- Post, J. M., and S. R. Doucette. 2019. Dangerous Charisma: The Political Psychology of Donald Trump and His Followers. New York: Pegasus.

- Pry, P. V. 2021. North Korean: EMP Threat. Washington, D.C: Department of Homeland Security.

- Putin, V. 2015. ““The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation”, Embassy of the Russian Federation to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.” June 29, 2015. https://rusemb.org.uk/press/2029

- Roberts, B. 2015. The Case for U.S. Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century. Redwood City, Calif: Stanford University Press.

- Rumsfeld, D. and Commission. 1998. ““Executive Summary”, Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States.” https://irp.fas.org/threat/bm-threat.htm

- Russell, B. 2001. Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare. New York: Routledge.

- Sagan, S. D. 1993. The Limits of Safety: Organizations, Accidents, and Nuclear Weapons. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Samii, K. A. 1987. “Truman against Stalin in Iran: A Tale of Three Messages.” Middle Eastern Studies 23 (1): 95–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00263208708700691.

- Sanger, D. E., and M. Haberman. 2016. “In Donald Trump’s Worldview, America Comes First, and Everybody Else Pays,” New York Times, March 25, 2016, A1.

- Schlesinger, J., Michael P. Carns, I. I. Crouch, Jacques S. Gansler, Edmund P. Giambastiani Jr, John J. Hamre, Franklin C. Miller, Christopher A. Williams, and James A. Blackwell Jr. 2008a. Secretary of Defense Task Force on DoD Nuclear Management, Phase I: The Air Force’s Nuclear Mission. Washington D.C: US Department of Defense.

- Schlesinger, J.,Michael P. Carns, I. I. Crouch, Jacques S. Gansler, Edmund P. Giambastiani Jr, John J. Hamre, Franklin C. Miller, Christopher A. Williams, and James A. Blackwell Jr., et al. 2008b. Secretary of Defense Task Force on DoD Nuclear Management, Phase II. Washington D.C: US Department of Defense.

- Sessler, A. M., John M. Cornwall, Bob Dietz, Steve Fetter, Sherman Frankel, Richard L. Garwin, Kurt Gottfried., et al. 2000. Countermeasures: A Technical Evaluation of the Operational Effectiveness of the Planned US National Missile Defense System. Union of Concerned Scientists and MIT Security Studies Program.

- Shanker, T. 2008. “U.S. Air Force Chiefs Face Firing after Nuclear Inquiry,” New York Times, June 5, 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/05/world/americas/05iht-pent.4.13507706.html

- Slocombe, W. B. 1981. “The Countervailing Strategy.” International Security 5 (4): 18–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2538711.

- Spetalnick, M., D. Brunnstrom, and J. Walcott. 2019. “Understanding Kim: Inside the U.S. Effort to Profile the Secretive North Korean Leader.” Reuters, March 7, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-northkorea-usa-trump-kim-insight/understanding-kim-inside-the-u-s-effort-to-profile-the-secretive-north-korean-leader-idUSKBN1HX0GK

- STET. 2009. “The Secret History of Kim Jong Il.” In Foreign Policy. October 2009.

- Aftergood, Steven, and Hans M. Kristensen. 2007. “Nuclear Weapons”, Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/nuke/guide/israel/nuke/

- Stimson, H. 1946. “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb,” Harper’s Magazine, February. https://www.atomicheritage.org/key-documents/stimson-bomb

- Stuckenberg, D., J. Woolsey, D. DeMaio, and B. E. Donna. 2019. “Electromagnetic Defense Task Force (EDTF) 2.) 2019 Report.” In LeMay Paper No. Vol. 4. Maxwell AFB, Ala: Air University Press.

- Tetlock, P. E. 2017. Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? New Edition) ed. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

- Thae, Y. H. 2020. “The Korean Peninsula Issues,” in Proceedings of ICAS Winter Symposium, December 17, 2020.

- Thucydides, R. W., and I. Moses. 1976. “Finley (Introduction and Notes).” In History of the Peloponnesian War. Penguin.

- Time. 1980. “Nation: Good Old Days,” Time Magazine, Monday, January 28, 1980. https://www.atomicheritage.org/key-documents/stimson-bomb

- Union of Concerned Scientists. 2015. “Close Calls with Nuclear Weapons.” January 15, 2015. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/close-calls-nuclear-weapons

- Wong, Y. H.,John M. Yurchak, Robert W. Button, Aaron Frank, Burgess Laird, Osonde A. Osoba, Randall Steeb, Benjamin N. Harris, and Sebastian J. Bae. 2020. Deterrence in the Age of Thinking Machines. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corp. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2797.html