Abstract

Algae are living organisms with high nutritional benefits. As such, algae are considered a solution to malnutrition and starvation. Individuals in the Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) region have limited food resources and face problems linked to malnutrition. Therefore, the introduction of a new food to their diet, such as algae, would be beneficial. However, these populations have conservative food habits and might not accept such anew food. Therefore, here we assessed consumer acceptance of natural and processed algae (seaweeds and Spirulina) in the Kingdom of Bahrain using a Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) approach. TAM is normally used to study the acceptance of technology, including commercial, industrial and nutritional industries. Here, we investigate the Bahraini community’s likelihood of accepting algal food as an alternative food source. In addition, factors impacting the acceptance of algal food as an alternative food were examined. Valid questionnaires (300) were collected to empirically test the research model using the partial least square (PLS) path modelling approach. We found that the following proposed hypotheses were supported, except for the relationship between perceived healthiness of food and behavioural intention. This study revealed that sensory aspects, perceive healthiness of food, and knowledge experience/familiarity have a significant positive direct relationship to perceived risk and uncertainty while having an indirect relationship with behavioural intention to consume the algal product. Subjective norm, perceived risk and uncertainty, food neo-phobia, and consumer decision to eat algal food products were found to directly influence consumers’ algal food behavioural intention, which, in turn, affects the consumers’ decisions about whether to consume algal food products. Our data suggest that the people in the Kingdom of Bahrain are willing to consume algae and, thus, that the Bahraini market is ready to receive algal food products.

1. Introduction

1.1. Algae as an alternative food

Algae are a diverse group of organisms found in multiple environments, especially seawaters and ponds. Algae use sunlight to photosynthesize. Algae can be classed as either macroalgae (seaweeds, large in size, over 150 feet long) or microalgae (that cannot be seen by the naked eye). Many species of macro- and microalgae are used for food, food additives, animal feed, fertilizers and biochemicals (Henrikson, Citation2009; Thomas, Citation2002). Algae are considered a main food and medicine source for Asian people. The nutritional benefits of algae make them a possible solution to malnutrition and starvation. In many centuries seaweeds are used as a traditional food. This custom has been spread by people from China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea as they migrated around the world so that today there are many countries in which seaweed is consumed (FAO, Citation2003). Most seaweeds are rich in protein, polysaccharides, minerals, antioxidants and significant amount of lipid and vitamins (Stévant, Rebours, & Chapman, Citation2017). They can be a source of essential fatty acids that reduce the risk of heart disease (Khotimchenko & Kulikova Citation2000; Maehre, Malde, Eilertsen, & Elvevoll, Citation2014; Sa´nchez-Machado et al., Citation2004). Because of its health benefits and nutritive value, consuming algae is recommended as a means of enriching the diet and preventing diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease, as well as iodine deficiency (Cordain, Eaton, Miller, Mann, & Hill, Citation2002). Therefore, certain countries, especially those with malnutrition problems or that do not already depend on algae in their diet, are urged to adopt algae as food. Therefore, in 1992, the USDA suggested that seaweeds (considered a well-balanced, healthy sea-vegetable) should be allocated to the bottom area of the food pyramid (together with typical vegetables and fruit) (USDA, Citation1992).

1.2. Algae as a potential source of superfood in the Middle East

Recently, edible seaweed products have become popular in the food industry in several countries (especially Japan) because of their interesting medicinal properties (Kılınç et al., Citation2013). In the Middle East, there has been a trend to enrich the diet using algae. For example, in Jordan, children at public schools are fed Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis). Spirulina is a microalga composed of nutrients like protein, mineral salts (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, zinc, copper, iron, chromium, manganese, sodium, potassium, and selenium); enzymes; antioxidants; vitamins (beta carotene, vitamin A, vitamins B1, B2, B6, B12, C and E) essential amino acids; and rare essential lipids such as gamma linolenic acid (Gutiérrez-Salmeán, Fabila-Castillo, & Chamorro-Cevallos, Citation2015; Ismail & Hong, Citation2002; Kent, Welladsen, Mangott, & Li, Citation2015; Matondo, Takaisi, Nkuadiolandu, Lukusa, & Aloni, Citation2016). A study in Lebanon identified microalgae species that have the potential for use as a superfood or as cheap renewable energy (Makki, Citation2014). Moreover, in the Middle East and other poor countries, the Intergovernmental Institution for the use of Microalgae Spirulina Against Malnutrition (IIMSAM) supports children and adults suffering from malnutrition and other disorders resulting from undernourishment (IIMSAM, Citation2008).

In the GCC region, seaweeds have been used as fish bait by threading algae along the hook. Old fishermen were occasionally consuming the seaweeds during bait preparation. However, it is not well known that people in this region use algae as a source of food. Seaweeds are used for purposes other than feeding people. For example, seaweeds are used as decoration and for adding nutritional value to chicken feed (El-Deek et al., Citation2011). Previously, UAE grew Spirulina in the new islands for decoration. More recently, the government in UAE have developed a strategy to become the leader in the cultivation of Spirulina against malnutrition, establishing a Spirulina farm, which is the first of its kind in the Middle East (UAEinteract, posted on 26/7/2009). In Saudi Arabia, the use of algae as a food source is under research. For example, the extracts of three algal samples from Chlorophyta (Ulva lactuca), Phaeophyta (Sargassumcrassifolia) and Rhodophyta (Digeneasimplex) were chemically analysed. These three algal extracts had different antioxidant activities, as well as different profiles of sugars, uronic acids, amino acids and small amounts of betaines (Al-Amoudi, Citation2009). Another Saudi Arabian study investigated the use of brown algae in chicken feed. The use of algae resulted in an increase in chicken body weight, egg production and egg quality. Furthermore, there was an increase in the immunity of the birds, as well as in their antioxidant and selenium content. The findings of these Saudi Arabian studies might encourage the people in the Gulf region to use these algae as a superfood (Al-Harthi & Al-Deek, Citation2011), especially in light of the concern about meeting basic food needs in the GCC region.

Novel food products are being developed at an increasing rate. Unfortunately, how people react to these products is understudied (Tenbült, de Vries, Dreezens, & Martijn, Citation2008). Although novel food products are continually introduced into the markets, their failure rate has been estimated as 60% (Costa & Jongen, Citation2006; Grunert & Valli, Citation2001) with few products surviving in the long term. Consumer acceptance is a major factor in the success of a novel food product. Thus, consumer perception of food should be studied in order to identify critical factors that lead to their acceptance or rejection.

The people of the Arabian Gulf suffer from a malnutrition problem due to an unhealthy nutrition pattern (Musaiger, Hassan, & Obeid, Citation2011); therefore, enhancing the diet of people in this region is important. Owing to their nutritional value, we propose that algae should be introduced to the region as a high nutritional source of food. However, it is difficult to change the food habits of these peoples and to introduce new foods. Here, we develop a framework for consumer acceptance of algal products in the Kingdom of Bahrain using a Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) approach. In addition, factors impacting the acceptance or rejection of algal food as an alternative food are studied. Those factors investigated here include socio-demographic determinants, cognitive and attitudinal determinants (knowledge and experience/familiarity), health consideration, the perception of risk and uncertainty, sensory appeal, subjective norm and food neo-phobia (Prescott, Young, O’Neill, & Yau, Citation2002; Ronteltap, Trijp, Renses, & Frewer, Citation2007; Verbeke, Citation2005; Vidigal et al., Citation2015).

1.3. Research contribution

There is not much known about consumer perception of algal food products in the Middle East particularly in the Kingdom of Bahrain. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first in the Middle East to investigate customer acceptance towards using algae as a food source. Due to the social, economic situation, people in the Middle East face a serious problem in nutrition-related diseases, such as growth retardation among young children and micronutrient deficiencies due to inadequate consumption of nutrients; in addition to those diseases which are associated with altering life style such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, osteoporosis, diabetes and obesity (Musaiger et al., Citation2011). The Arab communities need to be introduced to novel food with a high nutritional value such as algae. Moreover, algae are needed for sustainable development and food security as projects of algal cultivation in the region. For this purpose, the perception of eating algae in the region is necessary to be studied.

2. Research model and hypotheses

The main objective of this study is to investigate those factors that influence the acceptance of algae (Seaweeds/Spirulina) as an alternative food by the community of the Kingdom of Bahrain. The literature exhibited many factors that might affect the decision to accept and consume algae as an alternative food in any country (Prescott et al., Citation2002; Ronteltap et al., Citation2007; Verbeke, Citation2005).

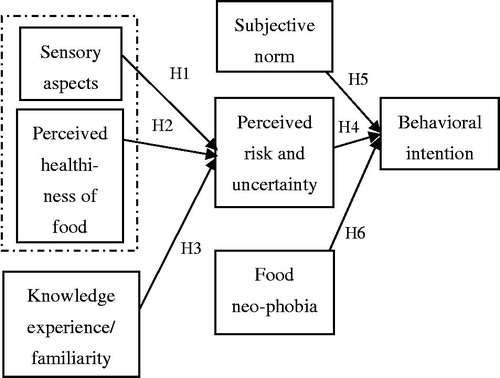

In the current study, four factors have been selected that might direct effect on behavioural intention to accept algal as a food: (1) socio-demographic factors (education, gender, body weight, diseases); (2) subjective norm; (3) perceived risk and certainty; and (4) food neo-phobia. Moreover, factors such as innovative features sensory appeal, perceived healthiness of the food and knowledge experience/familiarity have been selected as potentially an indirect effect on behavioural intention to accept consuming algae. The behavioural intention, however, is proposed as having a direct effect on the customers’ decisions about accepting and consuming algae (Seaweeds/Spirulina). As discussed earlier, concerning consumer acceptance of food technologies in previous work, different elements affecting the consumer acceptance which will be integrated into the conceptual framework (model) were assessed. The research model is depicted in .

Figure 1. Conceptual framework determinants of attitude towards using algae as alternative food source.

2.1.1. Sensory aspect

Sensory factors including appearance, colour, texture, taste and smell are important for the evaluation of food products, affecting perception and food acceptance (Grunert, Bredahl, & Scholderer, Citation2003; Ng’ong’ola-Manani, Mwangwela, Schüller, Østlie, & Wicklund, Citation2014). Sensory quality is necessary for the success of a product (Grunert, Citation2005). Consumers’ intention to buy genetically modified cheese was improved by its sensory qualities (Lahteenmaki et al., Citation2002). Moreover, the appearance of food increases purchasing attitude. Another study by Radder and Roux (Citation2005) that assessed the quality of food according to South African customers found that more than half of the respondents considered colour and smell as key indicators for determining the quality of meat, followed by texture. South African costumers identified flavour, tenderness and juiciness as the main indicators of the taste of red meat. Thus, sensory aspects related to food can affect the levels of uncertainty about a food product. Generally, people with lower uncertainty avoidance have a tendency to be more tolerant of risk (Jacqueline & Julie, Citation2002). Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

H1: Sensory appeal has a positive impact on perceived risk and uncertainty.

2.1.2. Perceived healthiness of food

Health is important for mankind; some consumers choose food products that they believe will help to maintain their health and meet their nutritional needs (Pollard, Kirk, & Cade, Citation2002). High nutritional value and low-calorie content are the main concerns for many customers when choosing food. Algae often have high contents of polyunsaturated fatty acids, which play a critical role in human metabolism (Koller, Salernob, & Braunegg, Citation2015). Moreover, algae are used to cure diseases such as goitre, intestinal afflictions, cancer, cervix dilation, Alzheimer’s, constipation, urinary tract infections, diarrhoea, breast infections, tuberculosis, headaches, scabies, cardiovascular disease and fungal infections, as well as for cholesterol reduction, bleeding control, vermifuge, breaking of fevers and as a wound dressing (Levine, Citation2016; Olasehinde, Olaniran, & Okoh, Citation2017). Owing to their health benefits, algae can be easily accepted as a food product. Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

H2: Perceived healthiness of algae (food) has a positive impact on perceived risk and uncertainty.

2.1.3. Knowledge and experience/familiarity

In general, there is a complex relationship between knowledge, expertise and risk. Consumer preferences for continuous innovations increase when they have related knowledge (Ronteltap et al., Citation2007). Uncertainty exists when details of situations are ambiguous or unpredictable; when information is unavailable or inconsistent; and when people feel insecure about their own knowledge or the state of knowledge in general (Ronteltap et al., Citation2007). In genetically modified food (GMF), knowledge and expertise were always found to be determinants of risk perceptions and attitude towards accepting it. Consumers’ risk perception of a broad range of hazards is increased by expertise (Bouyer, Bagdassarian, Chaabanne, & Mullet, Citation2001), whereas attitude is positively affected by available knowledge about gene technology and GMF (Siegrist, Citation1998; Verdurme & Viaene, Citation2001). In a study related to irradiated beef perception, knowledge about food safety appears to reinforce consumer intention to purchase irradiated beef (Rimal, McWatters, Hashim, & Fletcher, Citation2004). The role of knowledge in the acceptance of novel technologies was supported by another study, which stated that a lack of experience, knowledge and know-how could negatively affect the attitude towards accepting food (Radder & Roux Citation2005). On the other hand, the familiarity of new food will enhance its acceptance. This statement is supported by the spread of the use of algae as a food source in California and Hawaii, because of the large size of their Japanese communities (FAO, Citation2003). These communities spread the use of seaweeds through supermarkets and restaurants so that the taste of algae became familiar to the public. As a consequence, some companies have begun cultivating seaweeds onshore and in tanks, specifically for human consumption. The markets available to these companies are growing in California and Hawaii, and some companies are now exporting to Japan. Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

H3: Knowledge and experience have a positive impact on perceived risk and uncertainty.

2.1.4. Perceived risk and uncertainty

The emerging technologies in the food industry possess many risk characteristics, thus having a perceived threat to costumers’ health. These technologies include genetic modification, food enhanced by nanotechnology, additives, preservatives and packaging technology. To utilize the food product, the consumer should be convinced that his/her life is safe and will not be affected adversely by eating a novel food.

The most critical factor influencing selecting and using a product is the potential risk associated with the product, as the consumers are concerned about the harm and unknown health risks caused by the new technologies (Cardello, Citation2003; Cardello, Schutz, & Lesher, Citation2007). The quality of food is invisible and uncertain, so it is difficult to be estimated by the consumers (Cardello, Citation2003). Others consumers are open to innovation and trust the new food technologies and their ability to offer new benefits (Bruhn, Citation2007). Those believers in the new food technologies accept novel food processing technologies easily (Bord & O’Connor, Citation1990). Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

H4: Perceived risk and uncertainty has a positive impact on behavioural intention.

2.1.5. Subjective norm

The subjective norm is defined as the perceived social influences to like or dislike a particular behaviour. The role played by subjective norms in purchasing behaviour was confirmed by Pande and Soodan (Citation2015). Consumers are influenced to consume new food by trusted people, leaders’ opinions, and relevant prestigious organizations (Bruhn, Citation2007). However, perceived behavioural control and social norm have received less attention or no attention in the literature on consumer acceptance of food technology and innovations. On the contrary, Choo, Chung, and Pysarchik (Citation2004) stated that subjective norm was vital to consumers attitude towards new food technologies. Thus, subjective norm towards consuming algae might affect the behavioural intention. Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

H5: Subjective norm has a positive impact on behavioural intention.

2.1.6. Food neo-phobia

Food neo-phobia is normally related to the reluctance to eat new foods in which the consumer rejects consuming the unfamiliar food (Loewen & Pliner, Citation2000). Particular attitudinal, personality and lifestyle characteristics might also impact consumers’ attitudes towards acceptance or rejection of new technology. The presentation of a new food product probably initiates a fear response within the individual (Barcellos et al., Citation2010). Pliner and Hobden (Citation1992) developed the Food Neo-phobia Scale to assess individuals, willingness to try novel foods. The Food Neo-phobia Scale can identify those individuals who reveal a strong aversion to unfamiliar foods, who are referred to as neo-phobics. A lower acceptance of foods among consumers with a high level of food neo-phobia was reported (Labrecque, Doyon, Bellavance, & Kolodinsky, Citation2006). Other researchers found considerable differences in consumer's acceptance of unfamiliar food (beverages and fruits) between the low and high level of food neo-phobics (El Dine and Olabi, Citation2009; Sabbe, Verbeke, Deliza, Matta, & Van Damme, Citation2009). Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

H6: Food neo-phobia has a positive impact on behavioural intention.

3. Research methodology

To achieve the objectives of the current research, both experimental and survey approaches were used. An experiment was conducted to examine the behaviour of 30 people from University of Bahrain (UOB, students, and staff) in an algal taste test. This experiment is a pilot study to test the preliminary behaviours of UOB staff and students towards eating seaweeds. The outcome of the observations was reflected in the survey and in a second follow-up experiment. Participants were asked to taste seven types of algae (different types of pure natural seaweeds, crispy seaweeds, spicy seaweeds, biscuits supplemented with seaweeds and Spirulina), orange juice with seaweeds, and mango juice with seaweeds. The type of seaweeds was Nori (Porphyra sp.), red dulse (Palmaria sp.), Wakame (Undaria pinnatifida) and Hijiki (Hijikia fusiformis). Another experiment was done in Bahrain Garden Show (BIGS-2012), where almost 1000 individuals from different sectors and social ranks (including ministers, parliament members, Shurat Council members and the public) of the Kingdom of Bahrain were asked to taste algae. Different types of natural and processed seaweeds, Spirulina, different types of cheese with an Arabic taste but supplemented with seaweeds, and bread baked with a mixture of dried seaweeds were shown in the pavilion. The visitors were first introduced to general information about algae and their remarkable benefits, thereby encouraging them to taste algal food. A reasonable acceptance for algae consumption was noticed, especially after clearing the misconceptions around algae. Many of the participants returned to the pavilion to re-taste the different types/mixtures of algae and food supplemented with seaweeds. Due to the success of the two experiments, it was decided to measure the acceptance of people in the Kingdom of Bahrain of including algae in their diet. For this, a questionnaire was developed to measure the factors that determine acceptance of seaweeds consumption. Five-hundred questionnaires were distributed among the different segments of the Bahraini community. Of these, 300 were returned; a response rate of 60%, which is considered as a high response rate and is acceptable in such studies.

University of Bahrain students participated in the first part of the current study. The involvement of those students was due to the belief in the critical role imposed by higher education in the Arabian Gulf in measuring the scientific awareness among students. As examples for measuring the awareness among GCC University students, Universities in the United Arab Emirates (UAEU) and Kingdom of Bahrain (UOB) measured the student’ awareness of biotechnology and global warming. An overall weak performance of UAEU students’ understanding towards biotechnology was recorded (AbuQamar et al., Citation2015). This performance indicated the importance of enhancing students’ technology awareness via education. The positive role of educational, academic curriculum in scientific awareness was further confirmed in another study at UOB (Freije et al., Citation2017).

4. Data analysis and results

4.1. Experiments

The following section presents the results of an experiment involving 30 UOB participants, of which 20 were Bahrainis (). The demographic results of the responders show that the participants were students (n = 14), administrative (n = 10), academics (n = 5) or other (n = 1) (). Fourteen of the participants were 16–20 years old, 6 participants were 20–40 years old and 10 participants were 40–60 years old (). The majority of the participants were males (n = 18).

Table 1. Socio-demographic profiling of the participants.

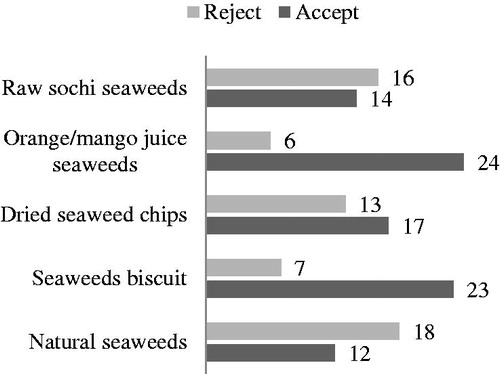

The results revealed that most of the participants accepted to taste the seaweeds in one or more of the exhibited algal types (naturally dried and processed) with different tastes. Thus, around 80% of the participants accepted to taste the orange/mango juice with seaweeds and seaweeds biscuit (24 and 23, respectively). However, more than 50% of the participants did not like the taste of the pure (natural) and the raw Sochi seaweeds because of their fishy taste (). It was also found that the appearance and the way the seaweeds were served affect the willingness of the individual to taste it. Moreover, the presence of a friend who likes to consume Seaweeds/Spirulina often encouraged the others to taste the algae.

4.2. Survey and research instrument

The following section presents the results of the second research method – the survey. The demographic results of the responders show that 56% of the participants were 16–20 years old; most were from secondary school levels (78.2%), as shown in . The majority of the participants were male (80%). The high acceptance rate of consuming algal products among the young suggests that improving the diet in GCC region using algae would be possible.

Table 2. Socio-demographic profiling of the participants.

The instrument used here was developed based on several studies addressing the perception of new technologies using TAM models. As such, scales for measuring sensory appeal and Perceived healthiness were developed by adapting items from the measurements of Radder and Roux (Citation2005); Ng’ong’ola-Manani et al. (Citation2014), Koller et al. (Citation2015), Levine (Citation2016) and Olasehinde et al. (Citation2017). The scales of perceived risk and subjective norm were developed by adapting items from Choo et al. (Citation2004), Bruhn (Citation2007), Cardello et al. (Citation2007) and Pande and Soodan (Citation2015). Food neo-phobia and knowledge and experience were developed by adapting items from Loewen and Pliner (Citation2000), Labrecque et al. (Citation2006), El Dine and Olabi (Citation2009) and Barcellos et al. (Citation2010). The instruments were divided into two main sections, demographic and research variables. The demographic information of the participants includes Gender, age, weight, the level of education and health status. The second section of the questionnaire includes research variables such as sensory appeals, perceive healthiness of food, knowledge and experience/familiarity, subjective norm, perceived risk and uncertainty, food neo-phobia and behavioural intention to consume the algal product. Five Likert-type scales were used in the questionnaire, which ranges from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

The results presented in show that most of the participants felt that their weight is ideal (54%), while around 30% believe that they are overweight. Moreover, most of the participants are diabetic (81%) or have high blood pressure (11%), while relatively few suffered from high cholesterol or osteoporosis (1.2%).

Table 3. Socio-demographics of the participants.

and show the participants’ awareness and attitude towards the algae and seaweeds food. We found that 90% of the participants were aware of seaweeds. Moreover, 71% of them knew that seaweeds products were sold in the market and 85% saw their parents/friend using at least one kind of seaweed as food. However, almost 46% of the participants did not know that lots of algae can be eaten and 54% of them accepted to consume algae for the purpose of losing weight. Most importantly, 73% of the participants prefer to consume sea food.

Table 4. Behaviour regarding eating algal products.

4.3. Hypotheses testing

The statistical objective of PLS is to show high path coefficient and significant t-statistics. Therefore, the causal relationships in the research model were tested by applying a bootstrapping produce, standard error and t-statistics. This permits the measurement of the statistical significance of the path coefficients.

We found that sensory appeal (β = 0.348, t = 5.767), perceived healthiness (β = 0.312, t = 4.903) and knowledge and experience (β = 0.303, t = 4.408) have an indirect effect on the behavioural intention of the individual to consume algae via received risk and uncertainty (). Three of them show either weak or insignificant direct impact on the behavioural intention (β = 0.196, t = 2.582, β = 0.026, t = 0.267, β = 0.098, t = 1.582). Thus, sensory appeal, perceived healthiness and knowledge, and experience are major factors in enhancing the perception of the risk and uncertainty of the algae food, explaining 34% of the variances on the perception of risk and uncertainty. We found that perceived risk and uncertainty (β = 0.414, t = 4.459), subjective norms (β = 0.255, t = 2.806) and food neo-phobia β = 0.369, t = 5.946) have a high and direct effect on the intention of individuals to consume algae or algal product, explaining 46% of the variances on the behavioural intentions, as shown in .

Table 5. Hypothesis testing (path analysis).

Table 6. Explanation of variances.

4.4. Assessment of model measurement

To test the research model, a PLS path analysis was performed using SmartPLS-3. The goodness-of-fit indexes (GFI) of latent variables are shown in and , indicating that the model has good fitness. Most of the AVE values are greater than 0.5, and all values of composite reliability are greater than 0.7, while all of the Cronbach’s Alpha values are greater than 0.7.

Table 7. AVE, composite reliability, and Cronbach’s Alpha.

Table 8. Factor loading of the model constructs.

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the consumer acceptance towards using algae as a food source in the Middle East. To assess the acceptance of eating algae, 30 individuals from UOB were given different types of algal food products(different types of pure dry Seaweeds, crispy Seaweeds, spicy Seaweeds, biscuits supplemented with Seaweeds and Spirulina), orange and mango juices mixed separately with Seaweeds. The majority of participants accepted eating biscuits baked with Seaweeds, Seaweeds chips and drinking orange/mango juice supplemented with seaweeds. A high acceptance of using algae as food was shown for the juices, probably due to the diluted fishy taste of algae. On the other hand, there was significant reluctance to taste the dry pure Seaweeds (including the sushi seaweeds). Encouraged by our initial findings, we repeated the experiment on a larger scale atBIGS-2012, where a large number of people with a different background visit the UOB pavilion.

The visitors to the UOB pavilion in BIGS-2012 were of various positions and ages. In this pavilion, the author tried to prepare an Arabian food mixed with algae (i.e. different types of cheeses and bread baked with Seaweeds) plus other natural dried Seaweeds and Spirulina. The visitors reacted pleasantly and accepted consuming Arabian food supplemented with algae in addition to the naturally dried algae (seaweeds) and Spirulina, especially when they knew about their medical benefits. The visitors were happy to taste the algae and encouraged their friends and relatives to visit the UOB pavilion. Some of the visitors visited the pavilion several times on different days to re-taste the algal food products.

For the data collection, hard and online copies of questionnaires were used. In addition to the online questionnaire, paper questionnaires were distributed to the visitors to the UOB pavilion in BIGS-2012 to measure their willingness to consume algae. An online questionnaire was selected for its cost advantage, greater geographical coverage and reduction of bias caused by the interviewer. Therefore, this study included the visitors to BIGS-2012, the individuals that participated in Experiment 2, and others from the Kingdom of Bahrain that participated online. The questionnaire was designed in two sections: deographics and research variables. In the demographics section, there was a total of five variables: gender, age, weight, the level of education and health status ( and ). The second section of the questionnaire includes research variables such as sensory appeals, perceive healthiness of food, knowledge and experience/familiarity, subjective norm, perceived risk and uncertainty, food neo-phobia and behavioural intention to consume the algal product. Five Likert-type scales were used in the questionnaire, which ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The sample size of this study was 300 individuals. According to Rezaei (Citation2015), the minimum requirement of a sample size to test the model using PLS-SEM is 100–150 participants. Delice (Citation2010) stated that larger sample size is needed to confer higher accuracy. Thus, the sample size of this study is in the acceptable range.

Socio-demographic variables normally shape food consumption (Moreira et al., Citation2010). The demographic results of the responders show that 56% of the participants were 16–20 years old. This age group easily accepts any change, including consuming unfamiliar food. The high acceptance rate of consuming algal products in the young ensures that improving the diet in the GCC region could be possible by introducing algae into their diet. Regarding the role of algae in losing weight, despite the ideal weight shown by more than half of the participants (54%), they accept that consuming algae has benefits, including aiding weight loss (Langea, Hausera, Nakamurab, & Kanayab, Citation2015).

In this study, sensory appeal (appearance, colour, texture, taste and smell) has been found to have a positive impact on perceived risk and uncertainty (hypothesis 1) which, in turn, affects behavioural intention, thus leading to the decision to consume algal products. This hypothesis was supported by several studies that confirm the role of sensory aspects of perception in food acceptance and, ultimately, the success of a product (Grunert, Citation2005; Grunert et al., Citation2003). In contrary, another study found that the consumer perceptions of food quality do not mainly depend on the sensory characteristics of the product but depend significantly on other factors such as cultural, social, cognitive and attitudinal factors related to the product and consumer (Cardello, Citation2003).

The effect of perceived healthiness of food on perceived risk and uncertainty was found to be significant in this research (hypothesis 2). This finding was consistent with other studies (Cardello, Citation2003; Poínhos et al., Citation2014; Ronteltap et al., Citation2007; Verdurme & Viaene, Citation2001) that have indicated a positive link between perceived healthiness, perceived risk, and uncertainty and behaviour. In addition, food safety concerns have increased considerably over the past decade with consumers becoming more aware of the possible health hazards associated with novel technologies in the food industry, such as the presence of preservative (nitrite) in meat, the use of nanoparticles in food, genetically engineered food and the use of radiation to sterilize food (Ajzen, Citation2005; Bord and O’Connor, Citation1990; Makatouni, Citation2001). Another study has confirmed that the health concerns of the consumer related to food hazards are significant determinants of acceptance (Miles & Frewer, Citation2001). When consumers knew about the negative health effect, which is associated with the use of nitrite in meat processing, they would likely select healthier meat products (Ajzen, Citation2005; Hung, de Kok, & Verbeke, Citation2016; Wilcock, Pun, Khanona, & Aung, Citation2004). Health consideration, natural content and weight control are important factors affecting the acceptance of seaweed consumption as a nutritive food (Prescott et al., Citation2002). Moreover, the perception of risk and uncertainty of novel food technologies will affect the behaviour of the consumer in selecting the food product (Ronteltap et al., Citation2007). Consumers who are able to control their own health status through their behaviours might be more encouraged to adopt consumer products with significant health benefits (Poínhos et al., Citation2014). Consequently, consumer perceptions of risk and uncertainty associated with food innovations play a critical role inedible algal product acceptance.

Here we show that knowledge and experience/familiarity has a positive impact on perceived risk and uncertainty (hypothesis 3). This means that consumers will be more aware of the risks of consuming algae when they are familiar with algae, know their benefits and have detailed, clear information, thus leading to an increase in the perception. The consumer’s perception of food depends on available knowledge. The type of information needed could be packaging, nutritional value, the product’s name, brands, labels, context and the situation in which the food is to be consumed. Food products have a remarkable effect on product preference, perceived sensory quality, acceptance, intended purchase and consumption (Cardello, Citation2003). Risk and uncertainty are critical factors affecting acceptance of food innovations, which leads to perceptions of risk and uncertainty (Cardello, Citation2003). The role of knowledge on perceived risk and uncertainty is supported by the findings of another study which proved that both experts and consumers expressed concerns about the potential risks associated with using nanotechnology to produce food and food products. Regarding the production of food via nanotechnology, experts perceived a greater risk than normal individuals as they are totally aware of the risks caused by food manipulated by nanotechnology. This demonstrates that the knowledge about any new technology will greatly affect the willingness to accept it.

The role of familiarity of consuming algae shown in this study is significant. A high percentage of the participants (85%) accepted consuming algae due to the presence of a friend or one member of their families consuming algae. Thus, the presence of a family member or a friend consuming algae enhances the acceptance of using algae as food. The high acceptance of consuming algae was likely due to the popularity of eating fish in this region (we found that 73% of the participants consume fish). Familiarity with a food is highly positively correlated with the behavioural intention. For example, Asian people that migrated to America and Europe introduced seaweeds to those regions. The presence of Asians who consume algae and the availability of seaweeds in America and Europe inspire confidence in citizens of those regions, resulting in an increase in acceptance of consuming seaweeds. Thus, other populations have adopted algae in their food due to familiarity. Moreover, more than half of the participants were young (54%), which means that they are accepting of change, especially when it is associated with diet. Although 46%of the participants showed primary ignorance about what is meant by algae, this ignorance did not hinder their acceptance to use algae as a food source. Therefore, there are factors other than the knowledge that will affect the acceptance of food.

We found that sensory appeal (β = 0.348, t = 5.767), perceived healthiness (β = 0.312, t = 4.903) and knowledge and experience (β = 0.303, t = 4.408) have an indirect effect on the behavioural intention of the individual to consume algae via received risk and uncertainty (). Therefore, sensory appeal, perceived healthiness, knowledge and experience are the main factors enhancing the individual perception of the risk and uncertainty of consuming algal food products. On the other hand, those factors show either weak or insignificant direct impact on the behavioural intention (β = 0.196, t = 2.582, β = 0.026, t = 0.267, β = 0.098, t = 1.582). Thus, sensory appeal, perceived healthiness and knowledge and experience/familiarities are the principal factors for enhancing the individual perception of the risk and uncertainty of algal food, although they explain just 34% of the observed variances. This means that there are other factors affecting the perceived risk and uncertainty that were not addressed here (e.g. nutritional value, quality, locality and price) and that should be investigated in future studies.

The results revealed that perceived risk and uncertainty (β = 0.414, t = 4.459), subjective norms (β = 0.255, t = 2.806) and food neo-phobia (β = 0.369, t = 5.946) have a high and direct effect on the intention of individuals to consume algae or algal products. However, these explain just 46% of the variances on the behavioural intentions (). Perceived risk and uncertainty were shown to have a positive impact on behavioural intention (hypothesis 4), which is measured by choice, purchase, and consumption (Cardello, Schuts, & Lesher, Citation2000). Expectations of liking/disliking a food can be affected by a variety of appropriate factors that are independent of the food itself. Those factors are societal, contextual, cultural, psychological and economical (Lambros et al., Citation2014; Higgs & Thomas, Citation2016). These factors should be studied further.

Subjective norm has been found to have a significant positive relationship with intention to consume algae product (Hypothesis 5). This effect of the subjective norm was supported by the study of Hasbullah et al. (Citation2016) who detected a positive relationship between subjective norm and intention to buy online. Moreover, it is supported by Theory Reasoned Action (TRA), which confirms a significantly positive relationship between subjective norm and behaviour (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). In other words, the friends or family of individuals apply pressure, which increases the person’s purchase intention. Subjective norm was considered as a strong determinant of intention (Karaiskos, Tzavellas, Balta, & Paparrigopoulos, Citation2010).

Consumer fears and risk perceptions have received considerable attention in the studies related to consumer acceptance of novel food (Miles & Frewer, Citation2001; Cardello, Citation2003). The current study found that food neo-phobia has a positive impact on behavioural intention (Hypothesis 6). Some individuals will reject eating unfamiliar food due to food neo-phobia. Earlier studies have confirmed distinct food neo-phobia effects (Pliner & Hobden, Citation1992; Tuorila, Meiselman, Bell, Cardello, & Johnson, Citation1994). This fear response may be due to sensory appeal, presentation, risk or food unfamiliarity. Expert opinions might reduce food neo-phobia as it increases potential acceptability by consumers (Giles, Kuznesof, Clark, Hubbard, & Frewer, Citation2015).

By adopting a TAM model, this study has highlighted a major gap in our knowledge of consumer perceptions, attitudes, beliefs and expectations in the community of Bahrain, which is similar to other GCC regions. As expected, seaweed will gain greater acceptance in regions such as the Middle East, where they have more common food habits in addition to the spread of Asian foods due to the large Asian communities in the region. Our data will provide policy makers, marine specialists and the food industry with evidence of the consumer acceptance of algal food products. Moreover, the result will provide evidence that will assist the main stakeholders making fine-tuning of policies, in addition to the estimation of consumers reaction in future towards algal food products.

6. Conclusions

This study revealed that the community of Bahrain is aware of the medical and nutritional importance of using algae as a source of food. Moreover, sensory appeal, perceived healthiness and knowledge/experience have a direct effect on the behavioural intention. There are other factors that should now be studied. In addition, perceived risk and uncertainty, subjective norm and food neo-phobia have a high and direct effect on the intention of the individual to consume algae. The results of this study will encourage the people in the Arabian Gulf to consider algae as an alternative food source. This influence will extend to the Middle East. In addition, our data will encourage the researchers in the field of nutrition to study the edible algae in the Arabian Gulf seas in terms of their nutritional importance. The people in the Kingdom of Bahrain are ready to enhance their diet with algae. Knowing that the people are accepting to use algae as a source of food will enhance the algal food business in the area.

7. Implications

This study provides suggestions for policy makers and marine specialists who are associated with food sector. In addition, the study can be helpful for the food industry to identify their target consumers by showing the effect of demographic factors, food neo-phobia, health, perceived risk and uncertainty, and knowledge/familiarity with algal food product market. Consumer’s acceptance of emerging technologies and their applications is a critical determinant of successful commercialization, and the strategy of the marketers should be altered accordingly. This study shows that health is a critical factor of acceptance. Therefore, retailers should concentrate on this factor when marketing to attract potential consumers. Moreover, the cultivation of algae for the purpose of producing food, medicines and cosmetics in the GCC should be considered in the market strategy.

Acknowledgements

It is my pleasure to acknowledge Dr. Jaflah Al-Ammari for her generous help without which the completion of the current study would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- AbuQamar, S., Alshannag, Q., Sartawi, A., & Iratni, R. (2015). Educational awareness of biotechnology issues among undergraduate students at the United Arab Emirates University. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 43(4), 283–293. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20863.

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

- Al-Amoudi, O. A. (2009). Chemical composition and antioxidant activities of Jeddah corniche algae, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 16, 23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2009.07.004.

- Al-Harthi, M. A., & Al-Deek, A. (2011). The effects of preparing methods and enzyme supplementation on the of brown marine algae (Sargassum dentifebium) meal in the diet of laying hens. Italian Journal of Animal Science, 10, e48. doi: 10.4081/ijas.2011.e48.

- Barcellos, M. D., Ku¨gler, J. O., Grunert, K. G., Van Wezemael, L., Pérez-Cueto, F. J. A., Ueland, Ø., & Verbeke, W. (2010). European consumers' acceptance of beef processing technologies: A focus group Study. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies, 11, 721–732. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2010.05.003.

- Bord, R. J. & O’Connor, R. E. (1990). Risk communication, knowledge, and attitudes: Explaining reactions to a technology perceived as risky. Risk Analysis, 10, 499–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1990.tb00535.x.

- Bouyer, M., Bagdassarian, S., Chaabanne, S., & Mullet, E. (2001). Personality correlates of risk perception. Risk Analysis, 21 (3), 457–465. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.213125.

- Bruhn, C. (2007). Enhancing consumer acceptance of new processing technologies. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies, 8, 555–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2007.04.006.

- Cardello, A. V. (2003). Consumer concerns and expectations about novel food processing technologies: Effects on product linking. Appetite, 40, 217–233. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00008-4.

- Cardello, A. V., Schuts, H. S., & Lesher, L. (2000). Predictors of food acceptance, consumption and satisfaction in specific eating situations. Food Quality and Preference, 11, 201–216. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(99)00055-5.

- Cardello, A. V., Schutz, H. J., & Lesher, L. L. (2007). Consumer perceptions of foods processed by innovative and emerging technologies: A conjoint analytic study. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies, 8, 73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2006.07.002.

- Choo, H., Chung, J., & Pysarchik, D. T. (2004). Antecedents to new food product purchasing behavior among innovator groups in India. European Journal of Marketing, 38 (5/6), 608–625. doi: 10.1108/03090560410529240.

- Cordain, L., Eaton, S. B., Miller, J. B., Mann, N. & Hill, K. (2002). The paradoxical nature of hunter-gatherer diets: Meat-based, yet non-atherogenic. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 56, S42–S52. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601353.

- Costa, A. I. A. & Jongen, W. M. F. (2006). New insights into consumer-led food product development. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 17(8), 457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2006.02.003.

- Delice, A. (2010). The sampling issues in quantitative research [Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Bilimleri]. Educational Sciences: Theory& Practice, 10 (4), 1969–2018.

- El Dine, A. N. & Olabi, A. (2009). Effect of reference foods in repeated acceptability tests: Eating familiar and novel foods using 2 acceptability scales. Journal of Food Science, 74(2), S97–S106. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.01034.x.

- El-Deek, A. A., Al-Harthi, M. A., Abdalla, A. A. & Elbanoby, M. M. (2011). The use of brown algae meal in finisher broiler diets. Egyptian Poultary Science, 31 (IV), 767–781.

- FAO. (2003). A guide to the seaweed industry. Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department.

- Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Freije, A. M., Hussain, T., & Salman, E. A. (2017). Global warming awareness among the University of Bahrain science students. Journal of the Association of Arab Universities of Basic and Applied Sciences, 22, 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaubas.2016.02.002.

- Giles, E. L., Kuznesof, S., Clark, B., Hubbard, C., & Frewer, L. J. (2015). Consumer acceptance of and willingness to pay for food nanotechnology: A systematic review. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, 17 (467), 1–26. doi: 10.1007/s11051-015-3270-4.

- Grunert, K. G. (2005). Consumer behaviour with regard to food innovations: Quality perception and decision-making. In W. M. F. Jongen and M. T. G. Meulenberg (Eds.), Innovation in agri-food system. Washington, The Netherlands: Washington University press.

- Grunert, K. G., Bredahl, L., & Scholderer, J. (2003). Four questions on European consumers’ attitudes toward the use of genetic modification in food production. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies, 4, 435–445. doi: 10.1016/S1466-8564(03)00035-3.

- Grunert, K. G. & Valli, C. (2001). Designer-made meat and dairy products: Consumer-led product development. Livestock Production Science, 72, 83–98. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(01)00269-X.

- Gutiérrez-Salmeán, G., Fabila-Castillo, L., & Chamorro-Cevallos, G. (2015). Nutritional and toxicological aspects of Spirulina (Arthrospira). Nutricion Hospitalaria, 32, 34–40. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.32.1.9001.

- Hasbullah N. A., Osmanb, A. H, Abdullah, S., Salahuddind, S. N., Ramlee N. F., & Soha, M. H. (2016). The relationship of attitude, subjective norm and website usability on consumer intention to purchase online: An evidence of Malaysian youth. Procedia Economics and Finance, 35, 493–502. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(16)00061-7.

- Henrikson, R. (2009). Earth food Spirulina: The complete guide to a powerful new food that can help rebuild our health and restore our environment. San Rafael: Ronore Enterprises, Inc.

- Higgs, S. & Thomas, J. (2016). Social influences on eating. Current Opinion in Behavioural Sciences, 9, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.10.005.

- Hung, Y., de Kok, T. M., & Verbeke, W. (2016). Consumer attitude and purchase intention towards processed meat products with natural compounds and a reduced level of nitrite. Meat Science, 121, 119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.06.002.

- IIMSAM (Intergovernmental Institution for the Use of Micro-Algae Spirulina Against Malnutrition). 2008. IIMSAM works. With concrete deeds. A year in review support IIMSAM support life. New York: IIMSAM.

- Ismail, A. & Hong, T. S. (2002). Antioxidant activity of selected commercial seaweeds. Malaysian Journal of Nutrition, 8(2), 167–177.

- Jacqueline, J. K. & Julie, A. L. (2002). The influence of culture on consumer impulsive buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2 (2), 163–176. doi: 10.1207/S15327663JCP1202_08.

- Karaiskos, D., Tzavellas, E., Balta, G., & Paparrigopoulos, T. (2010). Social network addiction: A new clinical disorder? European Psychiatry, 25, 855. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(10)70846-4.

- Kent, M., Welladsen, H. M., Mangott, A., & Li, Y. (2015). Nutritional evaluation of Australian microalgae as potential human health supplements. PLoS One, 10, 1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118985.

- Khotimchenko, S. V. & Kulikova, I. V. (2000). Lipids of different parts of the lamina of Laminaria japonica Aresch. Botanica Marina, 43, 87–91. doi: 10.1515/BOT.2000.008

- Kılınç, B., Cirik, S., Turan, G., Tekogul, H., & Koru, E. (2013). Seaweeds for food and industrial applications: Food industry. Croatia: InTech.

- Koller, M., Salernob, A., & Braunegg, G. (2015). Value-added Products from Algal Biomass. In A. Perosa, G. Bordignon, G. Ravagnan, & S. Zinoviev (Eds.), Algae as a potential source of food and energy in developing countries sustainability, technology and selected case studies (Vol. 2, pp. 19–40). Edizioni Ca'Foscari: Scienza e società.

- Labrecque, J., Doyon, M., Bellavance, F., & Kolodinsky, J. (2006). Acceptance of functional foods: A comparison of French, American, and French Canadian consumers. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 54 (11), 647–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7976.2006.00071.x.

- Lahteenmaki, L., Grunert, K. G., Astrom, A., Ueland, O., Arvola, A., & Bech-Larsen, T. (2002). Acceptability of genetically modified cheese presented as real product alternative. Food Quality and Preference, 13, 523–534. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(01)00077-5.

- Lambros, T., Karasavvoglou, A., Tsourgiannis, C. A., Florou, G., Theodosiou, T., & Valsamidis, S. (2014). Factors affecting consumers in Greece to buy during the economic crisis period food produced domestically in Greece. The Economies of Balkan and Eastern Europe Countries in the Changed World (EBEEC 2013). Procedia Economics and Finance, 9, 439–455. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00046-X.

- Langea, K. W., Hausera, J., Nakamurab, Y., & Kanayab, S. (2015). Dietary seaweeds and obesity. Food Science and Human Wellness, 4 (3), 87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2015.08.001.

- Levine, L. (2016). Algae: A way of life and health. In J. Fleurence & I. Levine (Eds.), Seaweed in health and disease prevention (pp. 1–5). New York: Academic Press, Elsevier.

- Loewen, R. & Pliner, P. (2000). The Food Situations Questionnaire: A measure of children’s willingness to try novel foods in stimulating and non-stimulating situations. Appetite. 35, 239–250. doi: 10.1006/appe.2000.0353.

- Maehre, H. K., Malde, M. K., Eilertsen, K. E., & Elvevoll, E. O. (2014). Characterization of protein, lipid and mineral contents in common Norwegian seaweeds and evaluation of their potential as food and feed. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 94(15), 3281–3290. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6681.

- Makatouni, A. (2001). What motivates consumers to buy organic food in the UK? British Food Journal, 104 (3–5), 345–352. doi: 10.1108/00070700210425769.

- Makki, M. (2014). Lebanon algae species: Promising source of protein, fuel. Nature. doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2014.245.

- Matondo, F. K., Takaisi, K., Nkuadiolandu, A. B., Lukusa, A. K., & Aloni, M. N. (2016). Spirulina supplements improved the nutritional status of undernourished children quickly and significantly: Experience from Kisantu, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2016, 1296414. doi: 10.1155/2016/1296414.

- Miles, S. & Frewer, L. J. (2001). Investigating specific concerns about different food hazards. Food Quality and Preference, 12, 47–61. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(00)00029-X.

- Moreira, P., Santos, S., Padrão, P., Cordeiro, T., Bessa, M., Valente, H., …., Moreira, A. (2010). Food patterns according to sociodemographics, physical activity, sleeping and obesity in Portuguese children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7, 1121–1138. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7031121.

- Musaiger, A., Hassan A. S. & Obeid, O. (2011). The Paradox of nutrition-related diseases in the Arab countries: The need for action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(9), 3637–3671. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8093637.

- Ng’ong’ola-Manani, T. A., Mwangwela, A. M., Schüller, R. B., Østlie, H. M., & Wicklund, T. (2014). Sensory evaluation and consumer acceptance of naturally and lactic acid bacteria-fermented pastes of soybeans and soybean–maize blends. Food Science and Nutrition, 2 (2), 114–131. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.82.

- Olasehinde, T. A., Olaniran, A. O., & Okoh, A. I., 2017. Therapeutic potentials of microalgae in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules, 22 (480), 1–8. doi: 10.3390/molecules22030480.

- Pande, A. C. & Soodan, V. (2015). Role of consumer attitudes, beliefs and subjective norms as predictors of purchase behaviour: A study on personal care purchases. The Business and Management Review, 5 (4), 284–291.

- Pliner, P. & Hobden, K. (1992). Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Apetite, 19(2), 105–120. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90014-W.

- Poínhos, R., van der Lans, I. A., Rankin, A., Fischer, A. R. H., Bunting, B., Kuznesof, S., …, Frewer, L. J. (2014). Psychological determinants of consumer acceptance of personalised nutrition in 9 European countries. PLoS One, 9 (10), e110614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110614.

- Pollard, J., Kirk, S. F., & Cade, J. E. (2002). Factors affecting food choice in relation to fruit and vegetable intake: A review. Nutrition Research Reviews, 15 (2), 373–387. doi: 10.1079/NRR200244.

- Prescott, J., Young, O., O’Neill, L., Yauc, N. J. N., & Stevensd, R., 2002. Motives for food choice: A comparison of consumers from Japan, Taiwan, Malaysia and New Zealand Steven. Food Quality and Preference, 13, 489–495. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(02)00010-1.

- Radder, L. & Roux, R. L. (2005). Factors affecting food choice in relation to venison: A south African example. Meat Science, 71, 538–589. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.05.003.

- Rezaei, S. (2015). Segmenting consumer decision-making styles (CDMS) toward marketing practice: A partial least squares (PLS) path modeling approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 22, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.09.001.

- Rimal, A. P., McWatters, K. H., Hashim, I. B., & Fletcher, S. M., 2004. Intended vs. actual purchase behavior for irradiated beef: A simulated supermarket setup experiment. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 10 (4), 1–15. doi: 10.1300/J038v10n04_01.

- Ronteltap, A., Trijp, J. C. M, Renses, R. J., & Frewer, L. J. (2007). Consumer acceptance of technology-based food innovations: Lessons for the future of nutrigenomics. Appetite, 49, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.02.002

- Sa´nchez-Machado, D. I., Lo´pez-Cervantes, J., Lo´pez-Herna´ndez, J., & Paseiro-Losada, P. (2004). Fatty acids, total lipid, protein and ash contents of processed edible seaweeds. Food Chemistry, 85, 439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.08.001.

- Sabbe, S., Verbeke, W., Deliza, R., Matta, V., & Van Damme, P. (2009). Effect of a health claim and personal characteristics on consumer acceptance of fruit juices with different concentrations of açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) Appetite, 53(1):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.014.

- Siegrist, M. (1998). Belief in gene technology: The influence of environmental attitudes and gender. Personality and Individual Differences, 24 (6), 861–866. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00021-X.

- Stévant, P., Rebours, C., & Chapman, A. (2017). Seaweed aquaculture in Norway: Recent industrial developments and future perspectives. Aquaculture International, 25(4), 1373–1390. doi: 10.1007/s10499-017-0120-7.

- Tenbült, P., de Vries, N. K., Dreezens, E., & Martijn, C. (2008). Intuitive and explicit reactions towards “new” food technologies: Attitude strength and familiarity. British Food Journal, 110 (6), 622–635. doi: 10.1108/00070700810877924.

- Thomas, D. N. (2002). Seaweeds. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Tuorila, H., Meiselman, H. L., Bell, R., Cardello, A. V., & Johnson, W. 1994. Role of sensory and cognitive information in the enhancement of certainty and liking for novel and familiar foods. Appetite, 23, 231–246. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1056 .

- USDA, Department of Agriculture. (1992). Human nutrition information service. Washington, DC: USDA.

- Verbeke, W. (2005). Consumer acceptance of functional foods: Socio-demographic, cognitive and attitudinal determinants. Food Quality Preference, 16, 45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2004.01.001.

- Verdurme, A. & Viaene, J. (2001). Consumer attitudes towards gm food: Literature review and recommendations for effective communication. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness and Marketing, 13 (2/3), 77–98. doi: 10.1300/J047v13n02_05.

- Vidigal, M. C. T. R., Minim, V. P. R., Simiqueli, A. A., Souza, P. H. P., Balbino, D. F., & Minim, L. A. (2015). Food technology neophobia and consumer attitudes toward foods produced by new and conventional technologies: A case study in Brazil. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 60 (2), 832–840. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.10.058.

- Wilcock, A., Pun, M., Khanona, J., & Aung, M. (2004). Consumer attitudes, knowledge and behaviour: A review of food safety issues. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 15, 56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2003.08.004.