ABSTRACT

The national has not withered away in the era of globalisation, and national cinemas still persist in various ways, even in the smallest nations. Using data collected for the MeCETES project, this article (the first of two looking at these issues) examines the evidence of popular national cinemas in contemporary Europe (2005–2015). It looks at admissions data for domestic productions, nation by nation, demonstrating that most European countries enjoy a small number of considerable national successes each year. In 2011, for instance, the French production, Intouchables, topped France’s admissions chart (and also did extraordinarily well across Europe). National productions also outranked all other films, including multi-million-dollar Hollywood blockbusters, in Italy, the Netherlands, the UK, Poland and the Czech Republic. The majority of these national successes were small-scale films, with themes, characters or subject-matter that resonated in the country of production. Few of them were co-productions and few travelled successfully across borders. National audiences showed a remarkable commitment to such films, demonstrating that popular national cinema is still a meaningful presence across Europe. The second article (Part Two) will look at some of the strategies deployed to create attractive and repeatable consumer products, the most common being genre. It will then re-visit the concept of national cinema, asking what role it plays in the era of globalisation.

The national has clearly by no means withered away in the era of globalisation. Just as the national and nationalism have been re-asserted politically around the world, national cinemas still persist in various ways, even in the smallest nations. Those cinemas are often nurtured politically and enjoy some economic and cultural success in their domestic – national – markets. This is not to deny that much of contemporary film production and consumption is transnational, but it is to recognise national cinema still has a place in the era of globalisation. This article follows in the footsteps of Dyer and Vincendeau’s (Citation1992a) pioneering collection, Popular European Cinema, and the effort to map what they call ‘indigenous popular film’ (1). As they note, ‘the popular cinema of any given European country is not always acknowledged even in the general national histories of film in that country’ (Dyer and Vincendeau Citation1992b, 1). That too often remains the case, even in accounts of contemporary cinema.

As a counterbalance to that tradition of film criticism, this article addresses the extraordinary resilience of popular national cinemas in twenty-first century Europe. As Dyer and Vincendeau (Citation1992b, 1) point out, one reason for the critical neglect of a whole range of cinematic output is that ‘highly popular European films seldom travel well beyond their national boundaries’. It is precisely this brand of cinema with which I am concerned here – not what we might call popular European cinema, which I would define as European films that do travel successfully in export markets, but what we should therefore call popular national cinemas within contemporary Europe.

In this article, I present the empirical evidence that demonstrates the continuing importance of national fare to national audiences in Europe, in the period 2005–2015. I also describe the range of domestic productions that have been hailed by audiences in their country of production. In the second part of this article (also published in this issue), I will look at some of the strategies deployed to create attractive and repeatable national popular films, the most common being genre. I will also draw some broader conclusions about national and transnational cinema in the age of globalisation.

The MeCETES project

Even within the EU, with its ideal of a single European audio-visual market, it is clear that national cinemas still prevail; thus, there are still clearly drawn national boundaries, linguistic boundaries and the boundaries drawn up by distributors of varying sizes. Brexit has simply exacerbated that situation. Like it or not, we don’t live in a post-national world, and the nation, national branding and national cinema remain central to public, official and scholarly discourse. In addressing this situation, this article draws on research undertaken for the MeCETES project, ‘Mediating Cultural Encounters Through European Screens’ (2013–16). This project set out to explore the extent to which audiences across Europe encountered other Europeans through watching films and television drama made in countries other than those in which they lived, during the period 2005–2015. The main conclusion in terms of cinema was that European films did not actually circulate very widely outside their main country of production, and that most audiences did not actually watch many non-national European films (that is, European films released outside their main country of production). The flip side of this conclusion is the substantial evidence of remarkably resilient national cinemas across Europe, with national audiences showing a strong attachment to nationally-produced films whose stories are set in those nations.Footnote1

This evidence is brought together in the MeCETES database created by Huw D Jones, which comprises information about the more than 21,000 films released theatrically in Europe in the period 2005–2015. The data is drawn from a variety of sources, including the European Audio-Visual Observatory’s LUMIERE PRO database and the Internet Movie Database (IMDb). It includes details of budgets, domestic and European distribution, European admissions as a whole and by country, and the number of European countries in which a film is distributed. ‘Europe’, for the purposes of this analysis, is defined as the EU28 (the 28 nations that constituted the EU between 2013 and Brexit in 2020) and the European Free Trade Association nations (Iceland, Switzerland, Norway and Liechtenstein). All films in the database, including co-productions, are assigned to the country with the majority stake in the production process. Domestic successes are defined as the films with the highest admissions in a particular territory, and which were majority-produced in that territory. The best travelled films are defined as the films with the most cinema admissions in European countries other than the main country of production. at the end of this article summarises key data from the database about every film mentioned in this article.

Table 1. Top 20 European productions in terms of admissions in their domestic markets, 2005–2015

The database deals primarily with theatrical admissions, and not with viewing data relating to films on television, DVD, Blu-Ray or online (VOD etc). It therefore provides only a partial picture of European film distribution in this period. The focus of this article is therefore not on how developments in the non-theatrical circulation of films have affected the European film business, access to films and the audience experience. This is obviously a shifting landscape, especially given the impact of the Covid pandemic. I note, however, that, as with theatrical distribution, different types of films benefit in different ways from non-theatrical circulation, and the overall picture about which films command attention and which don’t probably hasn’t changed substantially.

The European film market

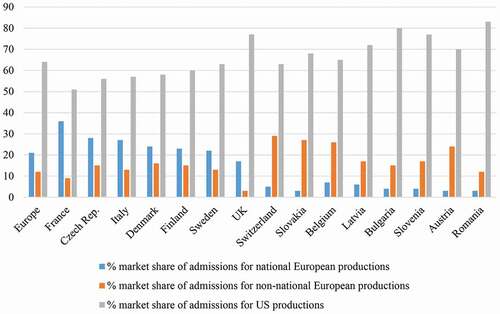

Some 14,000 films were produced in Europe between 2005 and 2015, but less than half were theatrically released in more than one European country. The (mean) average number of admissions (tickets sold) for those films that did travel to at least one European export market was 185,000, a tiny number, especially when we consider that the population of Europe is estimated to have grown from 730 m in 2005 to 740 m in 2015.Footnote2 In the same period, only 219 films (roughly 20 per year) sold more than 1 m cinema tickets in Europe outside their country of origin – the benchmark we adopted in the MeCETES project for a ‘successful European film export’. That is, less than 1% of European films circulated successfully outside their producing nation. The vast majority of cinema admissions in Europe are of course for American films, as indicates, and more than 1,000 US films achieved admissions of more than 1 m in Europe in 2005–2015, compared to the 219 non-national European films.

Figure 1. Market share of admissions for national productions compared with non-national European and US productions in selected territories

However, in most European countries, what the data also show is that there are in most years some home-grown, popular successes that hardly travel outside the producing nation. Indeed, one-fifth of the European market goes to national films. To put it another way, 21% of the total admissions for European films were for national European films (i.e. European films released within their main country of production), while only 12% of the total European box office was for non-national European films (i.e. European films released outside their main country of production). France recorded an even higher market share for national productions in the period 2005–15: a remarkable 37%. The other side of that statistic is that the market share in France for non-national European films was significantly lower than average, at 9%, as was the market share for American films, at 51%. What this indicates is the relative strength of the domestic production business and a greater audience commitment to national fare in France, but similar circumstances prevail across Europe, even in much weaker national film economies.

Thus, Italy (27%), Denmark (24%), Finland (23%) and Sweden (22%) also recorded above average admissions to domestic productions. The UK also enjoyed relatively high admissions for domestic productions, at 17%, but that figure includes big-budget, high-profile, inward investment UK/USA productions. (According to the criteria adopted here, such productions could still count as ‘national films’.) On the other side, pre-Brexit UK was positively Europhobic in recording only 3% of admissions to non-UK European productions, one of the lowest percentages across Europe. These six Western European countries (Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Sweden and the UK) all have relatively strong and/or well-supported domestic production industries, which partly explains why the proportion of ticket sales for national films was relatively high in these countries. There is also one Eastern European country with similar figures, the Czech Republic, where domestic productions enjoyed a 28% market share, with non-national European productions at 15%.

Compare these relatively high admissions to domestic productions in countries with relatively strong production sectors with the situation in smaller or less robust producing countries. In this instance, we find a relatively high market share for non-national European films in countries such as Switzerland (29%), Slovakia (27%), Belgium (26%) and Austria (24%). That is to say, audiences in these countries went to the cinema to watch a relatively high number of European films made outside the countries in which they live. These figures are all well above the average 12% of admissions across Europe for non-national European films. It is worth noting that all four of these countries have historic ties and/or a shared language with a larger neighbour (Switzerland with Germany, France and Italy; Slovakia with the Czech Republic; Belgium with France and the Netherlands; and Austria with Germany). The flip side of this is that Switzerland, Slovakia, Belgium and Austria also failed to secure more than a 7% share of the domestic market for nationally-produced films. This was also the case with several other Eastern European countries, including Latvia, Bulgaria, Slovenia and Romania.

If the overall market share for domestic productions in many European countries was pitifully low during the period under investigation, the domestic box-office achievements of individual national films across Europe could still make a considerable mark in the domestic market. In 2011, for instance, the French production, Intouchables, topped the admissions chart in France (and also did extraordinarily well across Europe as a whole). But national productions also outranked all other films, including multi-million-dollar Hollywood blockbusters, in Italy (where Che bella giornata secured more admissions than any other film that year), the Netherlands (Gooische vrouwen), Poland (Listy do M., Och, Karol 2 and 1920 Bitwa Warszawska) and the Czech Republic (Muži v naději 2D). The film with the most domestic admissions in the UK in 2011 was also officially a majority British film, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, although the Harry Potter franchise benefited from substantial inward investment from Warner Bros. In 2014, national productions again outranked all other films in the Czech Republic (Tri bratri), the Netherlands (Gooische Vrouwen II), Poland (Bogowie), Denmark (Fasandraeberne), Germany (Honig im Kopf), Finland (Mielensapahoittaja) and France (Qu’est-ce qu’on a fait au Bon Dieu?, Supercondriaque and Lucy).

Details of all films mentioned in this article are provided in , at the end of the article. Films are referred to by their original title in the article; provides English titles, where available, along with the date of release in the relevant domestic market; the countries involved in the production; domestic and other European admissions; box-office rank in the home market; budget; director; and genre.

Most of these domestic successes are the sort of small-scale genre films which are unable to compete on a regular and sustained basis with Hollywood blockbusters or with Hollywood-style and often Hollywood-backed European productions. Even so, a small number of such films each year commands huge national loyalty, and often secures far more significant box-office than more cosmopolitan art-house films, which may be better known in other countries and on the festival circuit. Nor is the market for national films shrinking. As Jones notes, ‘Over the last decade, national films have increased their market share by 7 percentage points’, with ‘the greatest gains in admissions for national films’ being ‘in countries (e.g. Italy, Poland, Netherlands, Finland) which have pursued a strategy of making popular comedies, family films and historical dramas primarily aimed at domestic audiences’ (Jones CitationForthcoming). Few of these nationally-popular genre films are known outside their own countries, however, because they rarely travel beyond the domestic market for which they are made. This is the case even in small producing nations with equally small domestic markets, where it might be thought it was economically impossible to sustain such a film culture. Thus most European countries were able to produce the occasional national box-office success, but few managed to establish anything in the way of successful foreign distribution for those home-grown hits.

What this analysis confirms is that there is a strand of the European film production sector geared to making relatively modest and unpretentious films primarily for domestic consumption, some of it with relatively sustainable levels of success. Europe is far from a level playing field in terms of the film industry, however. In terms of the size of the local production sector and the size of the local market for films (and indeed the size of the population), there are five Western European countries that stand out: the UK, France, Germany, Spain and Italy. As Jones (CitationForthcoming) observes,

The market for national films tends to be highest in countries which have a strong domestic film industry that can meet the demand for films which reflect national culture and identity. These are typically the large [western] European countries … or smaller but wealthy countries in western Europe (e.g. Denmark, Sweden, Finland), though there are some exceptions (e.g. Poland and the Czech Republic).

But the big five European countries, with the exception of the UK, are still not big players in the global market: that is to say, their productions are not routinely part of the global mainstream. The film industry in Europe, and the production business in particular, is highly fragmented, with numerous small companies operating primarily from a national base. The market likewise is highly fragmented, despite the efforts of the EU to create a single European audio-visual market. There is clearly much more to be said about the European film business in general and national circumstances in particular, in terms of ownership and control of the key companies, production infrastructure and finance opportunities, and film policy, film funding and tax credits. While that is not the focus of this article, see the accounts in Bondebjerg, Redvall, and Higson (Citation2015), Doyle et al. (Citation2015), Hammett-Jamart, Mitric, and Redvall (Citation2018), Harrod, Liz, and Timoshkina (Citation2014), Jones (CitationForthcoming), Jones and Higson (Citation2020), Liz (Citation2016), Meir (Citation2019), Poort et al. (Citation2019) and Townsend (Citation2021).

National productions for national markets

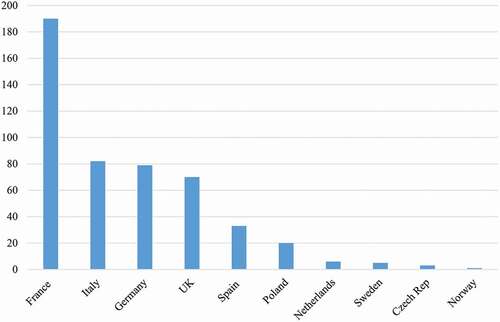

It is salutary to examine the lists of the ten most successful films of any provenance in all European countries in the period 2005–15 (disregarding those countries where the data is unreliableFootnote3). There are in total 230 films across the various national top ten admissions charts. Of those 230 films, 53 were national productions that fared well in their domestic markets. That is, around a quarter of the films were national productions evidently highly appreciated by their respective national audiences. Clearly, then, most European countries enjoy something in the way of a national cinema, defined in terms of the audiences in a particular country watching films produced in that country. The largest producing countries inevitably had the strongest national cinemas in these terms. Thus all of the 53 films across Europe (not the same 53 noted above) that achieved more than 4 m admissions in their home market had one of the big five Western European countries as the lead producer. Those big five countries also had a good number of domestically produced films securing more than 1 m admissions each at home (see ), with France notching up an extraordinary 190 such films, many more than any other country. This was followed by Italy, with 82 domestically produced films achieving more than 1 m admissions in the home market, Germany (77), the UK (70) and Spain (33). The only other country that secured 1 m admissions for an appreciable number of domestically produced films between 2005 and 2015 was Poland (20).

These figures are clearly heavily reliant on the size of the population in each European country (see ), and more specifically the size of the cinema-going public. Very few of the most successful domestic productions in the smaller or less developed markets secured more than 1 m admissions per film in those markets. Indeed, the only such successes were in the Netherlands (6), Sweden (5), the Czech Republic (3) and Norway (1). The absence of so many other European countries from this list is due partly to the size of the population of those countries, partly to the level of development of the theatrical market and partly to the weakness of the production sector. Thus the most successful Danish film in the domestic market between 2005 and 2015 was Fasandræberne, with admissions of just 769,092, against a national population of just 5.6 m (in 2015); the most successful Austrian production, Echte Wiener – Die Sackbauer-Saga, had domestic admissions of 372,239, against a population of 8.5 m; the most successful Latvian production, Rigas Sargi, had domestic admissions of 205,247, against a population of 2 m.

Table 2. Strength of production sector by country

In terms of the distribution of these successful national productions to European export markets, it is the same countries that dominate (Higson Citation2018; Jones Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2020). The export of UK productions to the rest of Europe was substantial, and included both American-backed blockbusters, most notably the Harry Potter and James Bond films (Casino Royale, Quantum of Solace, Skyfall and Spectre), and a range of more modestly budgeted middlebrow dramas and comedy dramas. France, followed by Germany, Spain and Sweden, also did reasonably well in this respect, while the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ireland, Italy and Norway all managed some success in the European export market. But almost half of the 53 films that secured more than 4 m domestic admissions failed to secure more than 1 m non-national European admissions. And only 15 of the 53 national productions that appeared in the top ten most successful films in those markets between 2005 and 2015 travelled well, securing more than 1 m non-national admissions. In other words, popular national success in no way guarantees success in the European export market. Admittedly, five of those films that did travel well actually notched up more than 20 m admissions. However, four of those were huge inward investment films led by the UK (two James Bond and two Harry Potter films), with the exception being the surprise French hit, Intouchables. But at the other end of the scale, five of the 53 most successful national productions did not travel at all, another seventeen sold less than 80,000 tickets outside their domestic market, and another sixteen sold less than 1 m tickets outside their domestic market.

To put it another way, 72% of the films that were most successful in their own national markets failed to meet the criteria for a successful intra-European export. On the one hand, that is a depressing statistic that reveals the fragility of the European production sector; on the other hand, it can be viewed much more positively, since it once again demonstrates the importance of national fare to national audiences, even in the age of globalisation.

National box-office successes in the big 5 Western European countries

By looking at the annual top ten most successful films of any provenance in each national market in the period 2005–2015, it is possible to develop a more detailed understanding of the performance of domestic productions nation by nation. In this context, the UK, Poland, France and Italy can each in their own way be considered special cases. The UK is a special case because the most popular domestically-produced films there (the Harry Potter and James Bond franchises) were also hugely popular across the rest of Europe and indeed the rest of the world. On the one hand, this may be seen in a positive light: British productions, British stories, British characters and British talent have the capacity to become pan-European and indeed global successes, rather than simply national successes. On the other hand, these franchises depended heavily on US studio investment and were addressed to the global market. As a result, more modest British films with smaller budgets, addressing more localised concerns, find it much harder to become national successes or to achieve box-office takings that can justify their budgets. Thus it is not easy to find the British equivalents of the home-grown, popular successes of France, Italy or the Czech Republic. And if there were plenty of British members of the cast and crew of the Potter and Bond films, some of the most prominent creative roles were taken by international filmmakers.

The UK production sector can still be regarded as strong, however, in that it was responsible for 1,521 productions, the second highest across Europe behind France, and huge amounts of money were invested in the various UK/US co-productions, and especially the Potter and Bond franchises. But for all its export success, where it had strengths in almost all markets, the UK production sector did not have a particularly strong hold in its own domestic market. Thus, only 18 of the available 110 places in the annual UK top tens were held by UK-led productions, and half of those were the Potter and Bond inward-investment films. That was fewer domestic productions in the annual top tens than in ten other European countries. Even with the consistently strong box-office for the inward-investment blockbusters, the share of the UK domestic market secured by domestic productions was still only 17%, below the European average. It is also worth recalling that only 3% of admissions were to non-national European productions, one of the lowest percentages across Europe: the theatrical audience for other European films in the UK is thus comparatively minimal. All of which demonstrates the hold Hollywood has on the UK market.

The only UK films appearing in the consolidated list of top ten admissions for films of any provenance across the whole period 2005–15 were the Potter and Bond films, with the next most successful UK productions, The King’s Speech and The Inbetweeners Movie, not appearing until numbers 27 and 28 in the list. The King’s Speech is typical of the middlebrow British drama that, by the standards of other European national cinemas, fares extremely well both at the domestic box-office and in non-national European markets. Middlebrow versions of cinema have received increasing attention in recent years (Faulkner Citation2016), with the category being fruitfully applied by various scholars to aspects of contemporary European cinema (Higson Citation2015; Bergfelder Citation2015; Liz Citation2016; Jones Citation2018). Five other British films that might be viewed as middlebrow also secured more than 4 m domestic admissions and 4 m non-national admissions, remarkable achievements by the standards of most other European national cinemas (Slumdog Millionaire, Mr Bean’s Holiday, Paddington, Wallace & Gromit in The Curse of the Were-Rabbit and Les Misérables).

The Inbetweeners Movie, and its sequel, The Inbetweeners Movie 2, are in a rather different category. They were both substantial domestic hits, with the first film achieving 7 m admissions in the UK market, making it the second most successful film in terms of tickets sold in the UK in 2011. The sequel achieved 5 m admissions, making it the fourth most successful film in 2014. But they fared much less well in European export markets, failing to sell more than 800,000 tickets outside the UK, with the first one being distributed to only 13 other European markets, far fewer than most other successful UK-led productions; the sequel, meanwhile, was picked up for only two other markets. To that extent, the Inbetweeners films were much more like domestic successes in many other European markets, being comedies that did not translate well to other national cultures, examples of what Jeancolas (Citation1992) calls inexportable cinema.

It is also much more difficult for a low-budget art-house film from the UK to stand out in the crowded UK market place and achieve the relative success of, say, Amour in France, Das Leben der Anderen in Germany or 4 luni, 3 saptamani si 2 zile in Romania. The British films that receive the most critical acclaim, according to their Metacritic scores or the number of awards they achieve, tend to be the more middlebrow productions, budgeted around $15 m. Again, this can be interpreted in different ways: on the one hand, higher quality but less mainstream British films can command bigger budgets than those in other producing territories; on the other hand, because they have higher budgets, they need to be more accessible and reach wider audiences than some of the more challenging material from other European producers. Mr Turner, The Queen, Slumdog Millionaire and The King’s Speech are typical in this respect. They are all critically acclaimed co-productions with budgets between $13 m and $18 m, and they are all relatively accessible dramas with quality production values. But while they feature character-driven rather than plot-driven narratives, they are not particularly challenging in terms of the ways in which they tell their stories or the themes with which they deal.

Moving to France and Italy, these are special cases in terms of national box-office performance because of the relatively widespread and consistent success of their domestic productions in their own national markets. If we look at the twenty most successful European films in terms of ticket sales in their domestic markets between 2005 and 2015, there were five French films in the list, including the only two European films that secured more than 20 m admissions in their domestic market: Intouchables, with 21.5 m national admissions, and Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis, with 20.5 m. These are higher domestic admissions for home-grown products then even the Potter and Bond films secured in the UK, even though the French films were made on budgets a fraction of the size of those Hollywood-backed UK franchises.

French national productions are generally heavily reliant on the French market for their success. Thus 77% of the ticket sales for Bienvenue … were in the domestic market; the equivalent figure for Rien à declarer was 80%, and for Les Bronzés 3: amis pour la vie 91%. Among the 20 most successful European films where domestic admissions accounted for a high proportion of overall European admissions were several other domestic (national) successes (see below). Thus the Italian production, Sole a catinelle, attracted 99% of its admissions in the Italian domestic market; Ocho apellidos vascos attracted 99% of its ticket sales in the Spanish domestic market; Fack ju Göhte, and its sequel, Fack ju Göhte 2, recorded 88% and 89% respectively in terms of ticket sales in the German market; and the aforementioned Inbetweeners Movie sold 87% of its European tickets in the UK. All of these films were comedies, and their performance is in stark contrast to that of the non-comedy UK domestic successes. The James Bond films, for instance, had a much lower average of 34% of domestic admissions among their total European admissions; the Harry Potter films had an even lower average, at 26%; and even The King’s Speech was only at 38%. As has so often been the case historically, it remains very difficult to sell locally specific comedies in the export market (Jeancolas Citation1992; Higson Citation1995, 163–164).

Table 3. Details of all films referred to in the article

As already noted, France has perhaps the strongest domestic production sector across Europe in that it was responsible for 2,610 films between 2005 and 2015 (see ). This is more than a thousand more than any other European country, despite having a similar sized population to UK and Italy, and a smaller population than Germany. It also means that the proportion of films per head of population is also relatively high. 30 of the 2,610 majority French productions appeared in the annual domestic top tens, including the most successful film in France in four separate years. French productions also secured first, second, fourth, fifth and sixth places in terms of overall admissions in the consolidated French top ten for the period. The only other productions to appear in the annual top tens were US or UK-led productions. That is to say, no other continental European productions figured in this list. French productions also enjoyed a reasonably significant European export market, especially in Belgium, Switzerland, Germany and the UK, all geographically and to some extent culturally proximate countries, followed by Austria, Hungary, Italy, Poland and Portugal, roughly in that order.

The five domestically most successful French films were all comedy dramas, most were modestly budgeted at less than $20 m, and all secured remarkably high domestic ticket sales: Intouchables (21 m), Bienvenue … (20 m), Qu’est-ce qu’on a fait au Bon Dieu (12 m), Les Bronzés 3 … (10 m), Rien à declarer (8 m). A rather different type of film, Lucy, a $40 m action thriller shot in the English language, with an American star, secured more than 5 m domestic admissions, and more than 10 m admissions in European export markets. These sales figures made it the second most successful French film in terms of non-national admissions in the period under discussion, behind the remarkable achievement of Intouchables. These two types of production, the modestly-budgeted comedy designed primarily for the domestic market, and the big-budget English-language production designed as much for the export market, were typical of European productions of the period. The latter type of production was however only affordable to one of the big five Western European nations.

Italy too had a relatively strong domestic production sector, in that it was responsible for 1,460 films across the 11-year period from 2005 to 2011. Those films had a strong hold on the domestic market, with 37 appearing in the annual top tens, including five number ones, and four in the consolidated Italian top ten. Thus Sole a catinelle was the most successful film of any provenance in terms of theatrical admissions in Italy in this period, with Che bella giornata at third, Benvenuti al Sud at fourth, and Benvenuti al Nord at sixth.

In several respects, Italian film production in this period is more localised than in the other four big European film nations. They secured some 50 m admissions between them in the domestic market, but none of these films made any impact in the export market, except in Switzerland, with its small Italian-speaking community. In addition to the films already listed, the ten most successful Italian films also included Natale a Rio and four of director Neri Parenti’s other cinepanettoni – films made for the Christmas market. Sole a catinelle and Che bella giornata were both directed by Gennaro Nunziante and starred Checco Zalone, who emerged from regional television and played a regional stereotype. Finally, Benvenuti al Sud and Benvuti al Nord were Italian remakes of the highly successful French comedy, Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis, all of them again playing on regional stereotypes. These films were generally quite modestly budgeted (see for details).

The final two members of the Western European big five, Germany and Spain, also had relatively strong domestic production sectors, with Germany responsible for 1,418 films and Spain 1,300. There were 18 German films in the annual top tens for the German market, and 3 in the consolidated German top ten for the period. The only non-US/UK import in the consolidated top ten was the French production, Intouchables, the second most popular film of any provenance across the period. In terms of types of successful films, the situation in Germany was similar to that in France. Thus the four domestically most successful German films were all relatively low-budget, German-language comedies, Fack ju Göhte, its sequel Fack ju Göhte 2, Honig im Kopf and Keinohrhasen. Only one of the four secured more than 1 m admissions in exports markets, although they all performed well in Germany’s main export markets, Austria and Switzerland, both geographically proximate countries with German-speaking communities. The fifth most successful German film in the domestic market, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, was rather different. A $64 m period crime drama, shot in the English language and starring Dustin Hoffman, neither its setting nor its characters were German, although there was still a strong national connection, in that the film was an adaptation of a very successful (and much translated) German novel. Like the French film, Lucy, then, this was again a big-budget English-language production rather than a home-grown comedy drama.

Moving to Spain, there were only 16 domestic productions in the annual national top tens, out of the more than 200 films on those lists, plus two French productions, Intouchables and Lucy. All the other places were taken by US or UK-led productions. The 16 Spanish films included three entries in the hugely successful, cartoon-like Torrente comedy-thriller franchise; the equally successful comedy, Ocho apellidos vascos, and its sequel Ocho apellidos catalanes; El orfanato, unusual for a national popular success for being a ghost thriller with no comic elements; and another instance of a big-budget, English-language production, the $40 m Lo imposible, with British stars and a non-Spanish setting. The latter four films also appeared in the consolidated domestic top ten for Spain for the period, though only the big-budget Lo imposible had a significant impact in the export market. Within the Spanish market, Ocho apellidos vascos was the second most successful film ever with Spanish audiences, behind only Avatar. Volver, probably the best-known Spanish-language production in the rest of Europe, was only the eighth most successful film in Spain in 2006, which only secured it 95th place overall in terms of admissions at Spanish cinemas for the period 2005–15. Spain’s main export markets were the rest of the big five Western European countries and the geographically and culturally proximate Portugal.

Budget sizes for small or less developed producing nations are somewhat different to their equivalents in the big five European nations. 15 of the productions led by the big five Western European nations cost more than $100 m, of which all but two were UK-led; another 28 cost between $50 m and $100 m, of which half were UK-led; and another 135 cost more than $20 m, of which 50 were UK-led. Only four of the productions made in the Nordic countries, the Netherlands and Belgium cost more than £20 m, and most cost less than $10 m. Of the Central and Eastern European countries examined here, just one film, led by Hungary, had a budget greater than $12 m, with just three Polish-led and one Romanian-led productions with budgets above $5 m. With a handful of exceptions, then, the production budgets for films led by and made in these countries were equivalent to a low budget film in one of the big five nations.

Few countries, large or small, exploited co-production opportunities for the creation of nationally successful films. In France and Germany, the more modestly budgeted comedies were all solely domestic productions, while the larger budget films, such as the German-led Perfume and the French-led Astérix aux jeux olympiques, tended to be co-productions. All of the most successful home-produced films in Italy and Spain, on the other hand, were solely domestic productions. The most prolific co-producers of domestic successes were Denmark, Norway and Sweden, evidence of relatively successful Scandinavian co-operation; and Hungary and Romania. The country that stands out in this respect is the UK, with eighteen of the twenty most successful UK-led films in the UK market being co-productions, and all of the top ten inward-investment productions backed by American studios. The two exceptions were the two Inbetweener comedies, which of course hardly travelled outside the UK market: both were solely domestic productions.

One might argue that one of the reasons why so many of European productions failed to travel outside their domestic markets was because of the failure to attract co-production partners at the development stage. That is to say, carefully developed transnational production arrangements might have created the circumstances for successful transnational circulation of the films. On the other hand, one might observe that these films were conceived and made as national productions, with nationally-specific themes, settings, stories and characters. They did not need to travel abroad to achieve the goal of appealing to and telling stories for domestic audiences. To that extent, co-production partners would have been a distraction to what were, for all intents and purposes, self-consciously localised cultural initiatives.

National box-office successes in the rest of Europe

Among the smaller Western European countries and the various Central and Eastern European countries, four had relatively strong production sectors in the period 2005–15. Thus Poland, the Czech Republic, Denmark and Finland each had more than 35 national productions in the annual domestic top tens for the period. Poland is another special case in that it was the only country outside the big five Western European countries that had 20 or more domestically produced films securing more than 1 m admissions in the home market. The domestic production sector was strong enough to deliver 345 films, 32 of which appeared in the annual Polish top tens, four of them at number one for the year, and five in the consolidated Polish top ten for the period. Those five all secured more than 2 m domestic admissions. Of those films, Listy do M., its sequel, Listy do M. 2, and Lejdis were comedy dramas, while Katyń and Bogowie were historical dramas. The Polish export market was minimal, however, although some films were exported with reasonable success to the Polish diaspora in the UK.

The Czech Republic produced 442 films in the period, and in six separate years the most popular film in the domestic market was a Czech production. Six Czech films also appeared in the consolidated top ten for the period, with the three most successful, Vratné lahve, Ženy v pokušení and Pelísky (a 2007 re-release of a 1999 production), all securing more than 1 m admissions in the domestic market. Only Avatar has sold more tickets in the Czech market. All three of these successes were comedy dramas, as were the other three Czech films in the consolidated top ten, Líbáš jako Bůh, Muži v naději 2D and Obsluhoval jsem anglického krále. The main Czech export market was Slovakia, formerly a part of Czechoslovakia.

Denmark produced 335 films between 2005 and 2015, including three that were the most successful films in the domestic market in their year of release. The consolidated Danish top ten for the period included two domestic productions and two Swedish productions, while Norway was its main export market. Of Finland’s 281 domestic productions, 41 appeared in the annual top tens, including two number ones, and three in the consolidated Finnish top ten for the period. Its export market was very small, however, with most exports going to Norway and Estonia.

The Netherlands, Norway and Sweden all produced more than 300 films, with between 18 and 26 films in the annual top tens for their respective domestic markets. Again, intra-Scandinavian film trade proved reasonably strong, in terms of both co-production and distribution arrangements. Transnational cooperation was thus more developed and more effective within Scandinavia. Austria, Belgium, Hungary, Portugal and Switzerland each produced more than 200 films – with Switzerland notching up a very surprising 646. But none of these countries had more than ten films in their annual domestic top tens across the 2005–15 period. Belgium’s exports to the geographically proximate Netherlands and France were the only significant examples of foreign film trade enjoyed by any of these countries. Even Iceland, with its population of just 0.35 m, had 2 domestic films in its consolidated top ten for the period, and although no Greek films appeared in the consolidated top ten, three appeared in the top 30.

Finally, seven more Central and Eastern European countries recorded a very modest average of just over 100 domestic productions each across the period 2005–2015, and very little in the way of exports This was the case in Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. The production of films in Eastern Europe was clearly much more circumscribed than in Western Europe, with less developed national infrastructures and creative economies, more modest funding and production values, and local stars and cultural traditions that are much less familiar to both mainstream and niche Western European audiences. But even these relatively very weak producing countries enjoyed some national hits, and boosted their capability by engaging in the occasional co-production. Thus in Bulgaria, Mission London was the most successful film in domestic cinemas in 2010, while Love.net was the second most successful film in 2012, with two other Bulgarian films appearing in the top ten for that year. The Estonian historical film, 1944, appeared in the consolidated top ten for Estonia for the period. Latvia had two domestic productions in its annual top tens, Rigas Sargi and Sapnu komanda 1935, both of them again historical films, with Rigas Sargi proving to be the second most popular film of any provenance in Latvia for the period. Romania had one domestic production in its annual top tens, the critically acclaimed 4 luni …, which subsequently became a European art-house presence, with more than 1 m admissions in non-national European markets. Slovakia’s annual top tens included three Slovakian and twelve Czech productions, including the Slovak-led co-production, Bathory, which was the most popular film of any provenance in Slovakia in the period 2005–15. Slovenia’s annual top tens included five domestic productions, two of which were the most successful films of their year, Petelinji Zajtrk in 2007, and Gremo Mi Po Svoje in 2011. No Croatian films appeared in its consolidated top ten, but two appeared in the top 20.

Conclusion: the resilience of popular national cinema in Europe

The wealth of admissions data presented here demonstrates that, even in an era dominated by global media corporations, popular national cultural productions still have a place. National audiences across Europe continue to engage with modestly budgeted genre films with locally recognizable stars. Those films feature themes, characters or subject-matter that resonate with audiences in their domestic market. Every year, most national cinemas in Europe will produce at least one film that makes its mark with national audiences, even though they are competing with big-budget Hollywood films and other English-language films made in Europe. Despite the huge difference in scale and production values, a small number of national films will regularly feature in national top tens in terms of numbers of tickets sold. Audiences and critics outside those domestic markets will rarely be aware of such films, because so few of them will travel. They are simply not made for the export market.

In Part Two of this article (in this issue I will examine the genre conventions frequently adopted to create such popular national successes, and especially comedies and national historical dramas). I will also reflect on the implications of such developments for debates about globalization, and the concepts of national and transnational cinema.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Huw D Jones for his extensive help with the research for this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrew Higson

Andrew Higson is Greg Dyke Professor of Film and Television at the University of York. He has published widely on British cinema history and on ideas of national, transnational and European cinema. His books include Waving the Flag: Constructing a National Cinema in Britain (Oxford University Press, 1995), English Heritage, English Cinema: The Costume Drama Since 1980 (Oxford University Press, 2003), and Film England: Culturally English Filmmaking Since the 1990s (I.B. Tauris, 2011). He has edited three surveys of British cinema history, Dissolving Views: Key Writings on British Cinema (Cassell, 1996/Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), British Cinema, Past and Present (with Justine Ashby; Routledge, 2000), and Young and Innocent? The Cinema in Britain, 1896–1930 (University of Exeter Press, 2002). He has also co-edited two books on European cinema: ‘Film Europe’ and ‘Film America’: Cinema, Commerce and Cultural Exchange, 1920–1939 (with Richard Maltby; University of Exeter Press, 1999), and European Cinema and Television: Cultural Policy and Everyday Life (with Ib Bondebjerg and Eva Novrup Redvall; Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). The latter book is one of many publications arising from the HERA-funded research project he led from 2013–2016, Mediating Cultural Encounters Through Europeans Screens (www.mecetes.co.uk). He is currently Director of the Screen Industries Growth Network (screen-network.org.uk).

Notes

1. For other analyses of statistical data about national production and box-office share in European and other film industries, see Crane (Citation2014), Bergfelder (Citation2015) and Alaveras, Gomez-Herrera, and Martens (Citation2018).

2. http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/europe-population/ (accessed 1.3.19), drawing on United Nations data.

3. These countries are Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

References

- Alaveras, G., E. Gomez-Herrera, and B. Martens. 2018. “Cross-border Circulation of Films and Cultural Diversity in the EU.” Journal of Cultural Economics 42 (4): 645–676. Advance online publication. doihttps://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9322-8.

- Bergfelder, T. 2015. “Popular European Cinema in the 2000s: Cinephilia, Genre and Heritage.” In The Europeanness of European Cinema: Identity, Meaning, Globalization, edited by M. Harrod, M. Liz, and A. Timoshkina, 33–58. London: IB Tauris.

- Bondebjerg, I., E. N. Redvall, and A. Higson, eds. 2015. European Cinema and Television: Cultural Policy and Everyday Life. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Crane, D. 2014. “Cultural Globalization and the Dominance of the American Film Industry: Cultural Policies, National Film Industries, and Transnational Film.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 20 (4): 365–382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2013.832233.

- Doyle, G., P. Schlesinger, R. Boyle, and L. W. Kelly. 2015. The Rise and Fall of the UK Film Council. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Dyer, R., and G. Vincendeau, eds. 1992a. Popular European Cinema. London: Routledge.

- Dyer, R., and G. Vincendeau. 1992b. “Introduction.” In Popular European Cinema, edited by R. Dyer and G. Vincendeau, 1–14. London: Routledge.

- Faulkner, S., ed. 2016. Middlebrow Cinema. London: Routledge.

- Hammett-Jamart, J., P. Mitric, and E. N. Redvall, eds. 2018. European Film and Television Co-production: Policy and Practice. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harrod, M., M. Liz, and A. Timoshkina, eds. 2014. The Europeanness of European Cinema: Identity, Meaning, Globalization. London: Bloomsbury.

- Higson, A. 1995. Waving the Flag: Constructing a National Cinema in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Higson, A. 2018. “The Circulation of European Films within Europe.” Comunicazioni sociali 3: 306–323.

- Higson, A. 2015. “British Cinema, Europe and the Global Reach for Audiences.” In European Cinema and Television: Cultural Policy and Everyday Life, edited by E. N. Redvall, I. Bondebjerg, and A. Higson, 127–150. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jeancolas, J.-P. 1992. “The Inexportable: The Case of French Cinema and Radio in the 1950s.” In Popular European Cinema, edited by R. Dyer and G. Vincendeau, 141–148. London: Routledge.

- Jones, H. D. 2014. “The Circulation of European Films.” MeCETES, April 11. http://mecetes.co.uk/circulation-european-films/

- Jones, H. D. 2016. “What Makes European Films Travel.” Paper presented at the European Screens Conference, University of York, September 5. https://www.academia.edu/32847055/What_Makes_European_Films_Travel

- Jones, H. D., and A. Higson. 2020. “Bond Rebooted: The Transnational Appeal of the Daniel Craig Bond Films.” In Beyond 007: James Bond Reconsidered, edited by J. Verheul, 103–122. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press/Chicago University Press.

- Jones, H. D. 2018. “Crossing Borders: The Circulation and Reception of Non-National European Films in Italy.” Comunicazioni Sociali 3: 324–340.

- Jones, H. D. Forthcoming. Transnational European Cinema: The Cross-Border Production, Circulation and Reception of European Film. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jones, H. D. 2020. “Crossing Borders: Investigating the International Appeal of European Films.” In European Cinema in the Twenty-First-Century: Discourses, Directions and Genres, edited by I. Lewis and L. Canning, 187–206. Houndmills: Palgrave.

- Liz, M. 2016. Euro-Visions: Europe in Contemporary Cinema. London: Bloomsbury.

- Meir, C. 2019. Mass Producing European Cinema: Studiocanal and Its Works. London: Bloomsbury.

- Poort, J., P. B. Hugenholtz, P. Lindhout, and G. Van Til. 2019. “Research for CULT Committee - Film Financing and the Digital Single Market: Its Future, the Role of Territoriality and New Models of Financing.” European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies. doi:https://doi.org/10.2861/327156.

- Townsend, N. 2021. Working Title Films: A Creative and Commercial History. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.