Abstract

We describe herein a case of severe relapsed pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) concomitantly with severe pouchitis treated by tacrolimus. A 25-year-old woman had undergone proctocolectomy with construction of ileo-anal pouch surgery for refractory ulcerative colitis (UC). She first developed PG with refractory pouchitis, and infliximab (IFX) was administered to induce remission due to resistance to glucocorticoid therapy. After achieving remission, IFX was stopped. Five years later, severe skin ulcers concomitantly with severe pouchitis recurred and treatment with 30 mg oral prednisolone (PSL) combined with topical tacrolimus showed partial improvement. When PSL was tapered to 15 mg, the skin ulcers and diarrhea aggravated. Endoscopy revealed multiple ulcers in the ileal pouch. Treatment with oral tacrolimus was initiated for severe pouchitis and refractory PG. Forty days later, all skin ulcers became scars and multiple ulcers in the ileal pouch were also improved. Our case suggests that oral tacrolimus treatment could be a valuable treatment option for UC patients with refractory PG and pouchitis.

1. Introduction

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) was first reported by Brunsting et al. [Citation1] in 1930. PG is an idiopathic, ulcerative, chronic inflammatory skin disease. Perry reported a case series of PG complicating ulcerative colitis (UC) in 1957 [Citation2]. Since then, the relationship between PG and other autoimmune diseases, such as Crohn’s disease, aortitis syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis, has been described [Citation3]. The etiology of PG remains uncertain, but proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-8 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, are suspected to play an important role in its development [Citation4]. PG is recognized as an extra-intestinal manifestation (EIM) of UC [Citation5]. Systemic steroids, cyclosporine and anti-TNFα agents are recommended in the treatment of moderate to severe PG. However, some cases fail to respond or develop relapse. About 20% of patients with UC develop PG, and the severity of PG often mirrors that of UC. Here we report a case of severe PG complicated by pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal canal anastomosis (IPAA) for UC treated successfully with oral tacrolimus.

2. Case report

A 25-year-old Japanese woman was referred to our hospital with a diagnosis of UC. Despite medical treatment with 5 aminosalicylic acid (5ASA), high dose prednisolone (PSL) and L-CAP, disease activity remained high and she developed deep vein thrombosis of the left femoral vein. The treatment of azathiopurine was discontinud because of nausea and severe leukopenia in a short time. The gene analysis of the patient revealed nucleoside diphosphate-linked moiety X-type motif 15 (NUDT15) T/T genotype, suggesting that thiopurines would be unusable in the future. She subsequently underwent proctocolectomy with IPAA. Six months later, she developed cutaneous ulcers on her left foot, left wrist and right hand. From clinical findings and her skin biopsy, she was diagnosed as PG. The skin lesions responded to infliximab (IFX). After 3 months of IFX infusion, the skin wounds became scars and IFX was stopped. She also had continuous diarrhea and had been treated with 5ASA, loperamide hydrochloride. Five years later, she had suffered 4 weeks of increased loose, watery stool frequency in spite of treatment with metronidazole. Moreover, she relapsed with refractory PG and was admitted to our hospital for treatment.

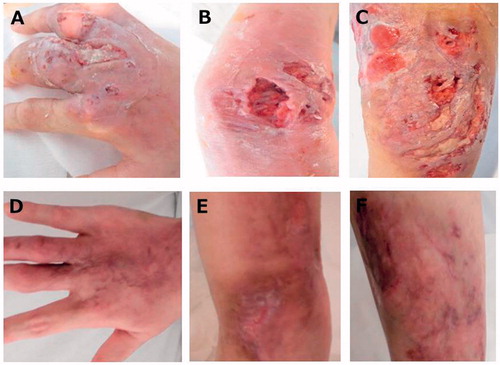

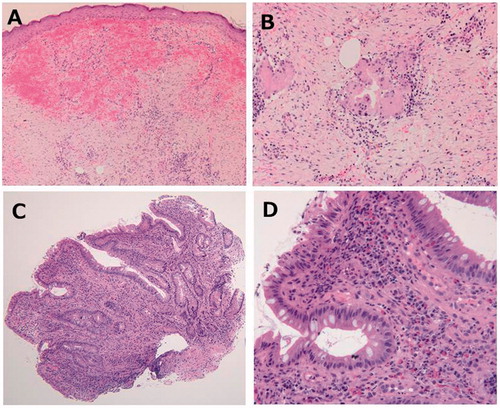

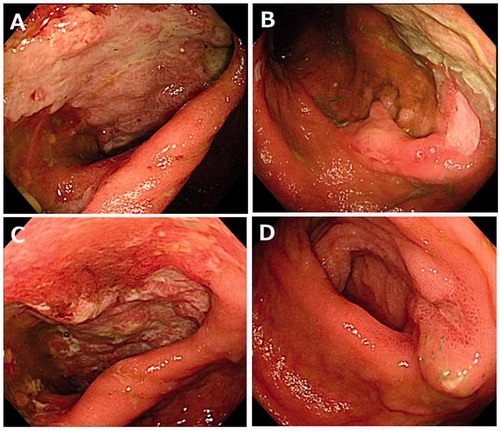

A review of systems was positive for diarrhea (soft formed stool 4 times a day) and negative for fever, weight loss and abdominal pain. Her performance status was 3, due to pain from the cutaneous ulcers. Physical examination showed cutaneous ulcers and slight anemia of her conjunctiva. She had destructive ulcers of the right chest, right hand, left wrist and left lower leg (). The ulcers had necrotic tissue at the center and reddish flat protrusion surrounding them. Laboratory data showed anemia (red blood cell count, 490 × 104/µL; hemoglobin, 9.0 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume,), inflammation (white blood cell count, 8760/µL; neutrophil percentage, 68.4%; C-reactive protein, 15.0 mg/dL) and hypoproteinemia (total protein, 6.6 g/dL; albumin, 2.3 g/dL) (). Skin biopsy results were compatible with PG, showing inflammatory cell infiltrates, primarily consisting of neutrophils, and fibrosis within the dermis (). There were no findings of vasculitis. Pathogenic bacteria were not detected by culture from the tissue or pus from the ulcer floor. Treatment with 30 mg oral PSL was initiated. On the 10th day, the ulcers remained unepithelialized and treatment with topical tacrolimus was started. More than 50% of the ulcer floor was epithelialized on day 23, and PSL was tapered. On day 30, PSL was reduced to 15 mg. The cutaneous ulcers recurred and the severity of diarrhea increased to 8 times a day. Fecal culture showed no evidence of pathogens of entelitis. Endoscopy showed multiple active ulcers at the ileal pouch (). Ileal biopsy showed inflammatory cell infiltration, villous atrophy and cryptitis (). No specific microbes were detected from culture of stool, including clostridium difficile. Both the serological test of cytomegalo virus (CMV) and immunohistochemical analysis of CMV were negative. She was diagnosed as pouchitis and pouchitis disease activity index (PDAI) was 12 (clinical score: 5; endoscopic inflammation: 4; acute histologic inflammation: 3) [Citation6]. Considering the fragility of her vein for continuous intravenous drip of IFX, the difficulty of frequent visit, and her skin ulcers on both of her hands which would cause difficulty for her injecting adalimumab (ADA) by herself, oral tacrolimus was started in order to treat both the pouchitis and PG. Trough concentration of tacrolimus was maintained at 5–10 ng/mL. Diarrhea and cutaneous ulcers dramatically improved () and endoscopic examination on day 78 showed significant improvement of the ileal pouch ulcers (). PDAI was improved from 12 to 4. She was discharged on day 81. Her performance status improved to 1, without any pain or contracture.

Figure 1. Gross appearance of the skin ulcers: the dorsum of the right hand (A), left wrist (B) and left lower leg (C) on admission. The dorsum of the right hand (D), left wrist (E) and left lower leg (F) demonstrating complete regression after treatment with 10 mg oral PSL and oral tacrolimus on day 78 after admission.

Figure 2. Histopathological findings of skin and ileal pouch. (A) Skin biopsies showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis without epidermal changes. (B) There were hemorrhage and chronic inflammation with giant cells and fibrosis in the epidermis, but there were no findings of vasculitis, such as vessel wall neutrophilic infiltration. (C) Histological findings of pouch mucosa showed total villous atrophy. (D) Moderate inflammatory cell infiltration and cryptitis.

Figure 3. Endoscopic findings showed active ulcerations of the pouch and anastomotic site on the 34th day after admission (A, B). After treatment with oral tacrolimus, the endoscopic findings dramatically improved on day 78 after admission (C, D).

Table 1. Primary laboratory data on initial visit.

3. Discussion

PG often complicates inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other autoimmune diseases. PG is known to be one of the EIMs of UC. Factors predictive of PG in UC include female sex, young age of onset of UC and having other EIMs. In addition, episodes of preoperative EIMs correlate with an increased incidence of postoperative EIMs [Citation7]. Our patient shows several of these features, including young age of onset, female sex and preoperative EIMs.

EIMs of UC, including PG, often parallel the activity of colonic inflammation, and some EIMs are cured by proctocolectomy. However, some of post-operated UC patients are refractory to medical treatments. A previous report showed that 38% of patients with refractory pouchitis after IPAA had EIMs [Citation8]. This report showed that 9 of 24 patients with refractory pouchitis had suffered EIMs, and 2 of 9 patients had PG. In our patient, PG with severe acute pouchitis developed after proctocolectomy and PG relapsed accompanied with severe pouchitis, suggesting that pouchitis was a systemic inflammatory response of UC.

The etiology of PG and pouchitis remain uncertain, but several reports suggest that EIMs, such as PG and pouchitis, are not due to localized inflammation, but are related to the systemic immune dysfunction associated with UC [Citation9–11]. Our patient underwent IPAA, which preserved the anal transitional zone mucosa. This small amount of preserved rectal mucosa might have led to the onset of PG with pouchitis.

Regarding medical therapy, treatment with topical tacrolimus is reported to be effective for mild cases of PG [Citation5]. Systemic treatments with steroid are required for severe cases, and immune suppressants such as cyclosporine and anti-TNFα agents are needed for severe cases refractory to steroid treatment [Citation11–13]. However, there are few reports about the efficacy of oral treatment with tacrolimus for severe PG [Citation13,Citation14]. In the present case, severe PG was observed, and treatment with oral PSL and topical tacrolimus was not sufficient. Severe pouchitis was also observed when PG relapsed. Because the ulcers and inflammation of skin were extensive and it was too hard to keep a route for scheduled transvenous administration, we selected the oral agent at first. Treatment with oral tacrolimus dramatically improved both PG and pouchitis. Several reports suggest that Th-17 cells, a T-helper cell subset producing IL-17, play an important role in the pathophysiology of PG [Citation15,Citation16]. Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressive agent that suppresses the immunological reaction of T cell [Citation17]. Therefore, it can be expected to suppress autoimmune disorders associated with Th-17 activity, thus ameliorating both PG and pouchitis.

In the present case, after three times of initial induction therapy of IFX, the skin lesions were immediately relieved. It is also unclear whether the maintenance therapy for EIMs including PG after colectomy is necessary or not. Then IFX therapy stopped. However, severe PG concomitantly with refractory pouchitis relapsed 5 years after stopping IFX. Our case indicated some cases would need maintenance therapy for EIMs after colectomy. Oral intake of tacrolimus was effective in our case for remission induction. Some reports showed the long-term efficacy of tacrolimus for UC patients [Citation18]. However, the efficacy of long-term use of tacrolimus for EIMs and refractory pouchitis have not established in IBD patients. If side effects such as renal dysfunction appeared or PG relapsed instead of continuous therapy, switching to ADA or IFX should be considered. In conclusion, we report a patient with severe PG complicated by severe pouchitis following IPAA for UC. Based on our findings, oral tacrolimus may be an effective treatment option to reduce remission in PG accompanied by pouchitis. The efficacy of tacrolimus for the treatment other EIMs, its ability to retain remission, and its safety should be verified in future studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ahmadi S, Powell FC. Pyoderma gangrenosum: uncommon presentations. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:612–620.

- Perry HO, Brunsting LA. Pyoderma gangrenosum; a clinical study of nineteen cases. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:380–386.

- Brooklyn T, Dunnill G, Probert C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. BMJ. 2006;333:181–184.

- Bister V, Mäkitalo L, Jeskanen L, et al. Expression of MMP-9, MMP-10 and TNF-alpha and lack of epithelial MMP-1 and MMP-26 characterize pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:889–898.

- Marzano AV, et al. Autoinflammatory skin disorders in inflammatory bowel diseases, pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome: a comprehensive review and disease classification criteria. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:202–210.

- Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:409–415.

- Ampuero J, Rojas-Feria M, Castro-Fernández M, et al. Predictive factors for erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:291–295.

- Subramani K, Harpaz N, Bilotta J, et al. Refractory pouchitis: does it reflect underlying Crohn’s disease? Gut. 1993;34:1539–1542.

- Abdelrazeq AS, Lund JN, Leveson SH, et al. Pouchitis-associated pyoderma gangrenosum following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1057–1058.

- Yanaru-Fujisawa R, Matsumoto T, Nakamura S, et al. Granulocyte apheresis for pouchitis with arthritis and pyoderma gangrenosum after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: a case report. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:780–781.

- Molnar T, Farkas K, Nagy F, et al. Successful use of infliximab for treating fistulizing pouchitis with severe extraintestinal manifestation: a case report. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1752–1753.

- Baumgart DC, Wiedenmann B, Dignass AU, et al. Successful therapy of refractory pyoderma gangrenosum and periorbital phlegmona with tacrolimus (FK506) in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:421–424.

- Arivarasan K, Bhardwaj V, Sud S, et al. Biologics for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum in ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. 2016;14:365–368.

- Jolles S, Niclasse S, Benson E, et al. Combination oral and topical tacrolimus in therapy-resistant pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:564–551.

- Mancini GJ, Floyd L, Solla JA, et al. Parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a case report and literature review. Am Surg. 2002;68:824–826.

- Brooklyn TN, Williams AM, Dunnill MGS, et al. T-cell receptor repertoire in pyoderma gangrenosum: evidence for clonal expansions and trafficking. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:960–966.

- Sigal NH, Dumont FJ. Cyclosporin A, FK-506, and rapamycin: pharmacologic probes of lymphocyte signal transduction. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:519–560.

- Minami N, Yoshino T, Matsuura M, et al. Tacrolimus or infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis: short-term and long-term data from a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015;2:e000021.