Abstract

Effective management of immune-related adverse events in patients receiving immunotherapy for cancer is problematic. In this report, we present the case of a 58-year-old man with advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma who responded well to a combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab. However, after two courses of treatment, he developed fulminant hepatitis and died. An autopsy confirmed that the primary lesion in the left kidney was more than 99% necrotic with only six small residual tumor lesions. These lesions were infiltrated by large numbers of CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes. However, a metastatic lesion in the right kidney harbored few lymphocytes. Furthermore, the tumor cells in the metastatic lesion and one of the residual lesions showed decreased expression of HLA class I molecules, which are a prerequisite for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated immunotherapy in tumor cells. In this patient, more than 80% of hepatocytes were destroyed and the parenchyma was infiltrated with CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes. The patient had polyuria, which was attributed to neurohypophysitis caused by the infiltration of CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes. We believe that this is an instructive case for immuno-oncologists.

1. Introduction

Immunotherapy is now a common treatment approach for cancer, along with surgery and chemoradiotherapy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), in particular, have been shown to be effective for many types of malignancy, including renal cell carcinoma (RCC). It is not unusual for patients with advanced unresectable tumors to achieve complete responses on an ICI. However, the immune-related adverse events (irAEs) associated with ICIs cannot be ignored. Although combination therapy with anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 agents is more effective than ICI as monotherapy, irAEs occur in up to 90% of patients on this combination therapy [Citation1,Citation2]. Nevertheless, irAEs are fatal in less than 1% of cases [Citation3].

In this report, we describe a patient with clear cell RCC who had a significant histologic response to a combination of ipilimumab plus nivolumab but developed fatal fulminant hepatitis. An autopsy confirmed almost complete response of the primary lesion and infiltration of CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes in the liver and neurohypophysis.

2. Case report

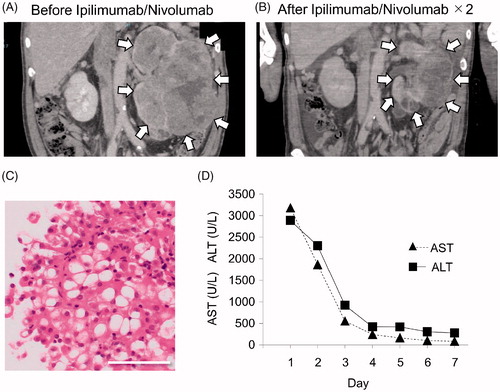

A 58-year-old man with a history of ischemic heart disease and diabetes mellitus visited a local hospital with a complaint of visible blood in the urine. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a 17.2 × 12.7 × 13.3-cm3 lesion suggestive of malignancy in the left kidney (). There was also a 1.3 × 1.5 × 1.6-cm3 S4 lesion, two small (4-mm and 8-mm) lesions in the liver, and a 3-mm mass in the left lung (not shown). Renal tumor metastasis was suspected. Tumor emboli were observed in the inferior vena cava. Histologic analysis revealed nest-like proliferation of tumor cells with rounded nuclei and clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm (). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the tumor was positive for pan-cytokeratin, vimentin, CD10, and PAX8, indicating clear cell type RCC. The tumor was evaluated as cT3bN1M1 in accordance with the TNM classification of Malignant Tumors 8th edition (Union for International Cancer Control, Geneva, Switzerland). The patient had a Karnofsky performance status of greater than 80%. His hemoglobin level was 6.9 g/dL with neutrophil and platelet counts of 6080/μL and 550,000/μL, respectively. Circulating levels of albumin-adjusted calcium, lactate dehydrogenase, and C-reactive protein were 10.5 mg/dL, 741 U/L and 7.49 mg/dL, respectively, indicating poor risk according to both the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center/Motzer criteria and the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium risk score for RCC. The patient received two courses of ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 240 mg. Laboratory tests performed 8 days after the first doses of these agents did not show any marked change from the pre-treatment values.

Figure 1. Clinical data and pathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen. (A) Computed tomography (CT) scan obtained at the first visit showing a lesion in the left kidney (arrows). (B) CT scan acquired after the second course of nivolumab showing that the lesion has become smaller (arrows). (C) Tumor cells with rounded nuclei and clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm are proliferating with nest-like structures. Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Bar: 50 μm. (D) Graphs showing aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels from the time of admission (day 1) to day 7.

However, 20 days after the final doses of ipilimumab and nivolumab, the patient was admitted to our hospital complaining of marked generalized body pain and weakness. The patient had no relevant past medical history or family history of allergy or autoimmune disease. CT images showed that the lung and liver metastasis had disappeared. The patient showed a partial response to chemotherapy based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors guidelines, at which time the tumor measured 12.4 × 7.2 × 10.5 cm3 (). Laboratory results on admission are shown in . There was severe liver failure, which was diagnosed as a grade 4 irAE. Blood aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase concentrations over time are shown in . There was no evidence of hepatitis-related viral infection, including hepatitis B or C virus. Due to the significantly decreased prothrombin time (less than 40%) and profound coma indicated by Glasgow Coma Scale score (eye-opening, 1; verbal response, T; motor response, 1), the patient was diagnosed as having fulminant hepatitis.

Table 1. Laboratory test results on admission.

In addition to liver failure, the patient also developed uropoietic dysregulation during hospitalization. On the day after admission, the plasma antidiuretic hormone (ADH) level was 4.1 pg/mL (normal value, <2.8 pg/mL without the restriction of fluid intake). Three days after admission, there was a sudden increase in urine output to 5 L/day, suggesting diabetes insipidus. At this time, the ADH level was 2.6 pg/mL, which was within the reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging showed no significant findings in the pituitary gland (not shown).

Systemic prednisolone 120 mg and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg were instituted to suppress the overactive immune response. The patient was also admitted to the intensive care unit, where plasma exchange and peritoneal dialysis were performed. The patient was not a candidate for liver transplantation because of his rapidly deteriorating condition and died within 8 days of admission.

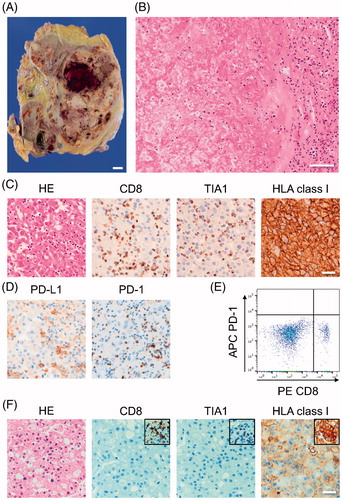

We performed an autopsy with the permission of the patient’s family. Macroscopically, we found a multinodular and heterogenous grayish-whitish mass (640 g) with sporadic areas of hemorrhage in the left kidney (). The entire mass was prepared as a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimen, and examined histologically. Interestingly, the left kidney was composed of at least 99% of necrotic tissue (). We found only six small viable RCC lesions (, Supplemental Figure 1). All the lesions were less than 5 mm in diameter and harbored numerous CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes (, Supplemental Figure 1). Infiltration of a very small number of FOXP3-positive cells was also observed (Supplemental Figure 2(A)). Although the residual tumor cells in the five lesions expressed HLA class I molecules, there was one lesion in which there was no expression of HLA class I molecules (, Supplemental Figure 1). Although we could detect PD-1 expression in the FFPE specimen on immunohistochemistry (, right panel), PD-1 was not detected by flow cytometric analysis of lymphocytes isolated from tissue in the left kidney before fixation with formalin (). While the infiltrated inflammatory cells expressed PD-L1, the tumor cells did not (; left panel).

Figure 2. Gross and microscopic morphology of the residual tumor. (A) Cut surface of the left kidney after fixation with formalin. The left kidney contains a mixture of yellow and grayish white multinodular material and occasional hemorrhage. It was not possible to distinguish viable from non-viable cancer tissue macroscopically. Bar: 10 mm. (B) Representative histopathologic image of the left kidney, which consisted of more than 99% necrotic tissue. Hematoxylin and eosin staining. (C) Representative histopathologic image of the residual tumor. HLA class I molecules were detected with 0.5 μg/mL of EMR8-5, a mouse anti-HLA A, B, and Cw monoclonal antibody. (D) Representative image of PD-1 (clone: EH33) staining and PD-L1 (clone: E1L3N) staining of the residual tumor. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of mononuclear cells extracted from the non-fixed left kidney (PE-CD8; clone: SK1, APC-PD-1; clone: EH12.2H7). (F) Representative histologic image of metastatic lesion in the right kidney. Inset: internal positive staining.

A metastatic lesion measuring ∼1.2 cm was found in the right kidney. This lesion was infiltrated by a smaller number of lymphocytes expressing CD8 or TIA-1 () and showed decreased expression of HLA class I molecules (). A detailed examination revealed no lesion suggestive of metastasis in either lung.

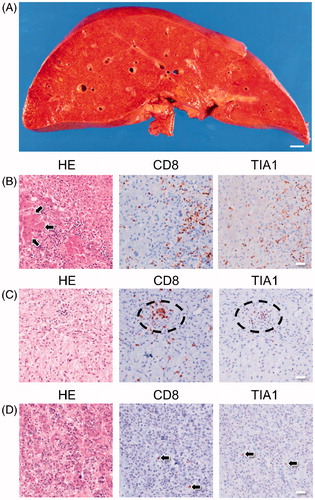

The liver was elastic and soft and weighed 965 g (reference weight 1000–1200 g; ). Histologically, approximately 80% of the liver tissue was destroyed, with infiltration of numerous CD8-positive and TIA-1-positive cells () and a small number of FOXP3-positive cells (Supplemental Figure 2(B)). This finding was identical to that in the primary lesion. Severe hemorrhage was also observed in the liver tissue. There were no hepatocellular rosettes and there was no evidence of emperipolesis or infiltration of CD20-positive or CD138-positive cells, which are the findings characteristic of autoimmune hepatitis. We found a 5 × 5-mm2 scar-like lesion with infiltration of foam cells, indicating a burned-out metastatic tumor.

Figure 3. Gross and microscopic morphology of the liver and histology of the pituitary gland. (A) Cut surface of the liver before fixation in formalin. The liver was diffusely elastic and soft and a yellowish-red color. Bar: 10 mm. (B) Representative image of liver histology shows that most of the hepatocytes are destroyed and harbor numerous CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes. Arrows indicate residual hepatocytes. (C) Representative image of histology of the neurohypophysis showing infiltration of CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes and appearance of an abscess-like lesion (circle). (D) Representative image of histology of the adenohypophysis showing infiltration by a few CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes (arrows).

The neurohypophysis of the pituitary gland harbored high numbers of CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive cells and had the appearance of a microabscess-like lesion (). In contrast, the adenohypophysis was infiltrated by a smaller number of CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive cells (). There was no significant inflammation in other organs, including the brain, both lungs, the heart, and the portion of the right kidney not involved with the tumor. We diagnosed liver failure caused by ICI-induced fulminant hepatitis as the cause of death.

3. Discussion

In this case, an RCC measuring more than 10 cm showed an almost complete histologic response to only two courses of ipilimumab combined with nivolumab. Although we found six small residual lesions (<5 mm), more than 99% of the tumor had disappeared. PD-1-positive cells were detected with immunostaining of the lesion in the left kidney but not by flow cytometry. This finding indirectly indicates the binding of nivolumab to PD-1 at the site of the lesion [Citation4,Citation5]. We performed immunohistochemistry on these lesions to investigate how the remaining primary or metastatic tumor cells escaped anti-tumor immunity. Our hypothesis was that the tumor cells resisted infiltration by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) or lost the HLA class I molecules needed for immune escape. Interestingly, the tumor tissue at the primary site contained numerous CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes with occasional dying cells. Therefore, these small lesions may have been under attack by the anti-tumor immune system. However, the metastatic lesion in the right kidney harbored a far smaller number of CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive lymphocytes. This metastatic lesion may have had an altered chemotactic mechanism. Furthermore, the expression of HLA class I molecules, which is a prerequisite for CTL-mediated cancer immunity, was decreased in the metastatic lesion and the single residual tumor lesion in the left kidney. Highly antigenic tumor cells, which show an excellent response to ICI, are thought to be exposed to strong immune-mediated selection pressure. Therefore, clones that downregulate HLA class I molecules in tumor tissue would escape the immune attack and become the predominant proliferating cells. We have previously referred to this putative phenomenon as ‘adaptive immune escape’ [Citation6]. Loss of HLA class I expression would cause tumor recurrence in patients who have received CTL-based cancer immunotherapy. Further molecular biological research is required to identify the genetic mutations or epigenetic alterations involved in this phenomenon.

With the expanding indications for ICI therapy, there are increasing reports of irAEs. A combination of a CTLA-4 blocker and a PD-1 inhibitor achieves excellent results in certain types of malignancy, including melanoma and RCC but causes grade 3–4 irAEs in more than 50% of cases [Citation1,Citation7]. While grade 3–4 hepatic irAEs have been reported to occur in 8–14% of patients who receive anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 combination therapy, there have been few cases of fatal fulminant hepatitis [Citation8]. We hypothesize that activation of immunity, which had a dramatic clinical effect, can also result in lethal hepatitis. A recent publication reported that the incidence of skin-related and gastrointestinal-related irAEs, but not hepatic irAEs, correlated with the clinical response in solid tumors treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab [Citation9].

We also found neurohypophysitis with infiltration of a high number of CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive cells in this patient at autopsy. Although we did not perform a detailed clinical examination to make a diagnosis of diabetes insipidus, the polyuria noted in our patient in the 3 days after admission was assumed to be due to CTL-mediated destructive neurohypophysitis resulting in central diabetes insipidus. Blood ADH level on the first day after admission was higher than normal, which is consistent with tissue destruction caused by inflammation. Thus far, there has been only one report of ICI (PD-L1 blocker)-induced diabetes insipidus [Citation10]. CTLA-4 blockade often causes adenohypophysitis but not neurohypophysitis [Citation11,Citation12]. This is the first case of histologically proven ICI-induced neurohypophysitis.

The following four mechanisms have been proposed to account for irAEs: overactivation of cellular immunity, increasing humoral immunity, excessive production of inflammatory cytokines, and enhanced complement-mediated inflammation [Citation13]. The ‘overactivation of cellular immunity’ pattern mediated by CD8-positive/TIA-1-positive cells was the likely mechanism in our patient. However, we could not identify the exact causative factor or a specific signaling pathway in this case. Other than in the primary tumor tissue, severe inflammation was found only in the liver and neurohypophysis. Of interest is the type of antigen targeted by CTL. Three types of irAE-related antigens are analogous to tumor antigens; these are neoantigens, endogenous antigens, and viral antigens.

Neoantigens are generated as a result of gene mutation during the evolution of malignancy. Many antigenic neoantigens can be candidates for activated immunity because RCC carries abundant frameshift mutations. Importantly, a recent study identified colonizing clones with somatic mutations in non-neoplastic human tissue, potentially resulting in antigenic neoantigens [Citation14]. Alternatively, because of nonspecific activation of systemic immunity by ICIs, CTLs that are specific for certain endogenous proteins in the liver and posterior pituitary gland might have been accidentally activated in our patients. Although there was no evidence that viral infection-induced chronic hepatitis, in this case, we cannot rule out the possibility of latent viral infection showing no or limited pathogenicity in the steady-state, given that subclinical infection with a viral antigen could be targeted by CTLs [Citation15]. Unfortunately, we do not have a screening method for prediction of irAEs, although the clinical effect of ICIs can be roughly estimated by CD8-positive infiltration, expression of PD-L1, and measuring the mutation burden in tumor cells. A biomarker for estimation of immune activation status and identification of clinical or adverse effects is urgently required.

In conclusion, we encountered a patient in whom combined ICI therapy was significantly cytotoxic to both a primary RCC lesion and liver tissue, resulting in fatal irAE. Nevertheless, a metastatic lesion in the right kidney appeared to escape from cancer immunity. Together with the identification of therapeutic targets and elucidation of the mechanism of immune escape, further investigations of the mechanism of irAEs are crucially important for the development of not only more effective but also safer cancer immunotherapy. In addition to basic and large-scale clinical studies, the accumulation of more cases that have been examined in detail should lead to the development of reliable cancer immunotherapy.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download TIFF Image (3.2 MB)Supplemental Material

Download TIFF Image (16.9 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michitoshi Kimura, Dr. Mami Yamaguchi, Dr. Hiroko Asanuma, Mr. Fuminori Daimon, Ms. Tomomi Kido, and Ms. Tomoko Takenami for their technical assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2006–2017.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):23–34.

- De Velasco G, Je Y, Bosse D, et al. Comprehensive meta-analysis of key immune-related adverse events from CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5(4):312–318.

- Osa A, Uenami T, Koyama S, et al. Clinical implications of monitoring nivolumab immunokinetics in non-small cell lung cancer patients. JCI Insight. 2018;3(19):e59125.

- Kamphorst AO, Pillai RN, Yang S, et al. Proliferation of PD-1+ CD8 T cells in peripheral blood after PD-1-targeted therapy in lung cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(19):4993–4998.

- Kubo T, Hirohashi Y, Matsuo K, et al. Mismatch repair protein deficiency is a risk factor for aberrant expression of HLA class I molecules: a putative adaptive immune escape phenomenon. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(3):1289–1295.

- Hodi FS, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma: 2-year overall survival outcomes in a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(11):1558–1568.

- Tian Y, Abu-Sbeih H, Wang Y. Immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced hepatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;995:159–164.

- Xing P, Zhang F, Wang G, et al. Incidence rates of immune-related adverse events and their correlation with response in advanced solid tumours treated with NIVO or NIVO + IPI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):341.

- Zhao C, Tella SH, Del Rivero J, et al. Anti-PD-L1 treatment induced central diabetes insipidus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(2):365–369.

- Iwama S, De Remigis A, Callahan MK, et al. Pituitary expression of CTLA-4 mediates hypophysitis secondary to administration of CTLA-4 blocking antibody. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(230):230ra45.

- Brilli L, Danielli R, Ciuoli C, et al. Prevalence of hypophysitis in a cohort of patients with metastatic melanoma and prostate cancer treated with ipilimumab. Endocrine. 2017;58(3):535–541.

- Postow MA, Hellmann MD. Adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1165.

- Martincorena I, Fowler JC, Wabik A, et al. Somatic mutant clones colonize the human esophagus with age. Science. 2018;362(6417):911–917.

- Johnson DB, McDonnell WJ, Gonzalez-Ericsson PI, et al. A case report of clonal EBV-like memory CD4+ T cell activation in fatal checkpoint inhibitor-induced encephalitis. Nat Med. 2019;25(8):1243–1250.