Abstract

Mobile health (mHealth) interventions that are integrated in HIV clinical settings to facilitate ongoing patient-provider communication between primary care visits are garnering evidence for their potential in improving HIV outcomes. Rango is an mHealth intervention to support engagement in HIV care and treatment adherence. This study used a single-arm prospective design with baseline and 6-month assessments for pre-post comparisons, as well as a matched patient sample for between-group comparisons to test Rango’s preliminary efficacy in increasing viral suppression. The Rango sample (n = 406) was predominantly 50 years of age or older (63%; M = 50.67; SD = 10.97, 23–82), Black/African-American (44%) or Hispanic/Latinx (38%), and male (59%). At baseline, 18% reported missing at least one dose of ART in the prior three days and chart reviews of recent VL showed that nearly 82% of participants were virally suppressed. Overall 95% of the patients enrolled in Rango returned for a medical follow-up visit. Of the 65 unsuppressed patients at baseline who returned for a medical visit, 38 (59%) achieved viral suppression and only 5% of the suppressed group at baseline had an increase in viral load at 6 months despite being at risk for ART non-adherence. While viral suppression was similar between Rango participants and patients receiving treatment as usual over the same time period, it is unknown whether those patients were similarly at risk for non-adherence. Our findings support efforts to formally test this innovative approach in addressing ART non-adherence and viral suppression particularly to reach HIV treatment goals.

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence is the single most important factor influencing virologic suppression, and retention in care is closely linked to adherence, with both impacting morbidity and mortality.Citation1,Citation2 Marginalized populations are at higher risk for not being retained in care and subsequently not achieving sustained viral load (VL) suppression.Citation3 Lack of patient-provider trust, stigma, co-morbid psychiatric and substance use diagnoses, and competing financial priorities are some of the factors that have been found to impact retention in care and ART adherence and furthermore, they tend to disproportionately impact vulnerable groups including ethnic and racial minorities as well as gender non-conforming individuals.Citation1,Citation2 Subsequently, there is an urgent unmet need for comprehensive interventions that address a multitude of factors that both contribute to and propagate disparities observed in HIV care outcomes.

Novel interventions have been undertaken to reduce disparities and improve retention in care and adherence, particularly for individuals out of care or those at higher risk for dropping out of care and an unsuppressed VL.Citation4 Electronic health (eHealth) and mobile health (mHealth) interventions have been utilized to improve ART adherence, clinic visit attendance and overall engagement in care.Citation5–11 Different mHealth interventions have been developed, ranging from SMS texting and smartphone games to more inclusive support packages in the form of mobile apps with or without a virtual support network interface or social media platform.Citation12–26 While most eHealth and mHealth interventions have been tested in trials with small samples, at single sites and without comparative control groups,Citation27–29 the available data suggest that they are effective at improving adherence, VL suppression and engagement in care, are liked and accepted by patients, and found to be feasible to implement as part of rigorous randomized controlled trials.Citation5,Citation7,Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation27,Citation30,Citation31 However, there is limited data supporting that mHealth interventions are crucial at initiation of ART or at re-entry to care after prolonged absence, both times when patients are particularly at risk for non-adherence.Citation4,Citation14,Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation25,Citation32–34 Due to the complexity and heterogeneity of patients with HIV who remain virologically unsuppressed or at risk for becoming unsuppressed, empirical studies show support for multifaceted comprehensive mHealth interventions at improving adherence and virologic suppression by supporting patients between care visits.Citation35,Citation36

VillageCare developed the Rango program, an online platform designed to be accessible on smart phones, mobile devices and computers that combines a variety of technology-enabled features into one service to improve engagement in HIV care and treatment adherence. Rango was designed to address multi-level factors that influence engagement in care and ART adherence. A growing body of research underscores the challenges in addressing health disparities in HIV care and highlights the importance of a multi-level, socio-ecological framework to understand the synergistic impact of factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, health system, and structural levels on sustained retention in care and virologic suppression.Citation37 At the individual level, the Rango intervention was designed to provide HIV-related information and improve knowledge about HIV treatment, to motivate patients about engagement in care and medication adherence, and to enhance behavioral skills and self-efficacy for treatment adherence. The Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills (IMB) modelCitation38 was the theoretical basis guiding intervention content. The IMB model posits that in addition to having accurate and reliable information that is premised on the available evidence base, individuals also need the motivation and the skills and sense of efficacy in order to engage in behaviors that promote health.

Recognizing that factors beyond those at the individual level are also crucial in supporting patients,Citation37 Rango was designed to also address factors at the interpersonal and health system levels. At the interpersonal and community levels, the Rango intervention addressed peer support by establishing a sense of community, albeit a virtual one, with access to a Health Coach one-on-one or in-group sessions. At the health system level, it provided a tool to providers to maintain healthcare engagement among patients about wellness outside of their medical care visit. Rango’s online social network was set up to leverage peer-to-peer interactivity via discussion boards and virtual support groups, and online consultations with a Health Coach provided access to health-related information from clinicians and the scientific community.

This study reports a pilot study during Rango’s implementation at health centers serving persons with HIV (PWH) throughout New York City (NYC) from November 2015-December 2017. This study sought to examine Rango’s preliminary efficacy in increasing the number of patients who achieve viral suppression. Our primary hypothesis was that increased viral suppression would be achieved among patients enrolled in Rango at 6 months compared to baseline. Additionally, we hypothesized that the proportion of virally suppressed patients would be greater among Rango participants compared to a matched cohort of patients receiving standard HIV care at the same institution without having been enrolled in Rango.

Methods

Overview of study design

VillageCare developed Rango—named after the late Dr. Nicholas Rango who was the Director of Village Nursing Home and the first Director of NY State AIDS Institute—and enrolled 4,400 patients with HIV as part of a large implementation effort in NYC to make Rango available for adherence support between medical care appointments. Of these, 406 patients at the Institute for Advanced Medicine (IAM) at Mount Sinai in NYC were enrolled in a pilot study to test its preliminary efficacy in improving viral suppression. A single-arm prospective trial with baseline and 6-month assessments was utilized for pre-post within-group comparisons, as well as between-group comparisons to a matched sample of patients at the IAM who were not enrolled in the Rango program. The Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at VillageCare and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai approved participation in the Rango online program and the pilot study for the extraction of electronic health records of patients receiving care at IAM.

Recruitment

Participant recruitment involved enrolling patients without virologic suppression and those at risk for becoming unsuppressed in order to test Rango’s preliminary efficacy in improving VL suppression. Providers at five IAM clinics referred patients to VillageCare program staff who screened patients for eligibility for enrollment in Rango. Eligibility criteria included HIV infection on ART (treatment experienced), documented medication adherence difficulties during a primary care visit operationalized as either having a detectable viral load or self-reports of missed ART doses, NYC residence, and receipt of Medicaid and/or Medicare benefits. Primary care providers or clinic ancillary staff including care coordinators and social workers referred patients for enrollment.

Procedures

As part of the enrollment process, participants completed separate informed consent forms for their participation in the Rango online program and the Mount Sinai pilot study for the extraction of electronic health records in order to examine the intervention’s preliminary efficacy in improving viral suppression. Upon enrollment, participants signed up to access the Rango program, were trained in using Rango, and completed a baseline questionnaire including basic demographic information and questions on ART adherence, substance misuse, and comorbidities, as well as the Patient Activation Measure (PAM). For the next 6 months, participants were able to access Rango from home using a unique user ID and password on smartphones, tablets and computers and scheduled their primary care appointments as usual directly at the IAM clinic where they received care. Follow-up assessments were completed by phone 6 months after the baseline assessment, and these data were merged with clinical data from primary care visits, which were extracted by chart review. Per month of active utilization of the Rango program (i.e., having had at least one log on), participants received a $35 electronic gift card to major retailers for a total of up to $210 for the six months of Rango use. This compensation schedule was set up to offset any Internet connectivity costs participants would incur to access the Rango program online. No compensation was provided for the brief assessment at baseline and the 6-month follow-up.

Rango intervention

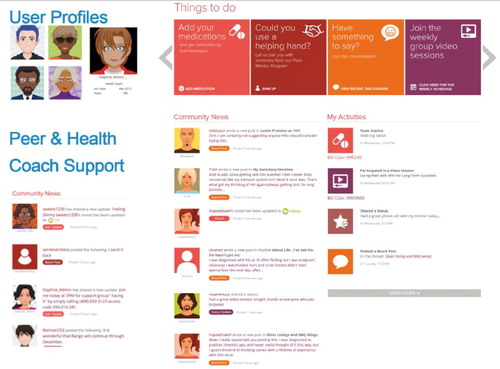

Rango, a virtual program promoting care engagement and medication adherence for people with HIV, was developed utilizing approaches based on NY State AIDS Institute’s treatment adherence initiatives with input from the health community and the latest guidelines on HIV treatment.Citation39–41 There were three primary components that made up the program. First, a dynamic social network interface was flexible to content adaptations with the goals to 1) address knowledge, motivation and skills to engage in HIV care; 2) create a sense of community through peer support to buffer the impact of stigma and promote norms on wellness; and 3) coordinate care and other support services, such as housing, that were facilitated by a bilingual (English and Spanish) social worker serving the role of a Health Coach. Second, individualized, tailored medication and appointment reminders were made via push notifications and text messaging. Third, access was provided to integrated services within the Rango platform for referrals to social services based on individual patient needs. Healthify, an app for managed-care plans and health care providers for referral services was integrated for its functionality to search for available social services and track patients' referral outcomes. Patients created user profiles and customized them while having the option to remain completely anonymous. Health Coach, moderator and administrative profiles were embedded in the social network, and were customizable to provide access to additional features and content monitoring. depicts some of Rango’s features to provide a snapshot of the look and feel of the program.

Measures

Participants responded to questions about age, gender identity, ethnicity and race, health coverage, housing, and Internet access. A question asked about the number of missed HIV medications in the prior 3 days and reasons for it. An additional question required participants to select any medical diagnoses and behavioral health conditions they have had in their lifetime. These questions were developed by the study team at the time of its design and have not been validated.

Patient Activation. Participants completed the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), a 13-item validated instrument licensed by Insignia Health in assessing health-related knowledge, motivation, skills, and behaviors among patients with chronic diseases.Citation42 Participants responded to the PAM items on a Likert scale from 1 (“Disagree Strongly”) to 4 (“Agree Strongly”), and responses were transformed to a total score ranging from 0 to 100. Scores were categorized into 4 levels, as is typically done for this scale, representing the following groups in terms levels of engagement in care: Level 1: disengaged and overwhelmed; Level 2: becoming aware but still struggling; Level 3: taking action; and Level 4: maintaining behaviors and pushing further.Citation42–44 The PAM has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of patient self-management across a wide range of chronic medical conditions and has been found to predict ER visits, hospital admissions and readmissions, medication adherence.Citation45–47

Electronic health records (EHRs) were extracted and merged with self-report data, including VL and CD4 count, comorbidities, mental health disorders, and alcohol and drug use. Given our primary objective to evaluate Rango’s preliminary efficacy in increasing the number of patients who achieve viral suppression, VL laboratory results were extracted for tests that were completed within 90 days of the baseline enrollment date and follow-up assessment. One participant did not have a record of a viral load test result within their baseline timeframe and therefore that case was not included in analyses involving VL, the primary outcome for this pilot study. Viral suppression was defined as <200 copies/mL given that HIV treatment guidelines utilize a confirmed viral load of 200 copies/mL as a threshold for virologic failure after consideration of viral load blips or assay variability.Citation48

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 24 using a significance level of p < 0.05. Descriptive statistics were obtained with proportions for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. To test our primary hypothesis that viral suppression would be significantly greater after access to Rango for 6 months compared to suppression at baseline, VL was dichotomized as suppressed (<200 copies/mL) and unsuppressed (≥200 copies/mL) and within group analysis was performed using McNemar’s testCitation49,Citation50 to examine pre-post change in reclassification in viral suppression from baseline to the 6 month follow-up period. The McNemar test is a non-parametric test with a Chi-square distribution that has three assumptions: 1) analysis involves one dichotomous dependent variable (i.e., viral suppression at 6 Months) and one dichotomous independent variable (i.e., viral suppression at baseline); 2) the two groups in the dichotomous dependent variable are mutually exclusive (i.e., a participant must be categorized as either suppressed or unsuppressed and cannot be both at 6 months); and 3) analysis involves a random sample. We tested the hypothesis that the proportion of unsuppressed patients at baseline who were reclassified at 6 months as suppressed is greater than the proportion of suppressed patients who were reclassified as unsuppressed at 6 months.

To test our second hypothesis that the proportion of virally suppressed patients would be greater among Rango participants compared to a matched cohort of patients receiving standard of care at the IAM, we used a repeated measurements analytic approach with Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) methodology employing an auto-regressive working correlation to account for within-subject correlation.Citation51–53 GEE is an extension of GLM for the analysis of longitudinal data that allows a working correlation matrix to be specified about the within-subject correlation of the dependent variable, which can have different distributions such as normal, binomial, and Poisson distributions.Citation51–54 Given that the Rango pilot study did not include a control group, EHRs were included in analyses of randomly selected IAM patients not enrolled in Rango and matched on participant characteristics. Matching on age group, race and ethnicity, gender, years since diagnosis, on ART, and viral suppression yielded a smaller sample size than the Rango sample and thus, fewer unsuppressed patients at baseline limiting statistical power to detect differences at 6 months. Therefore, to maximize statistical power, the treatment as usual sample of patients was matched on racial and ethnic group, on ART, and viral suppression and yielded data from 403 patients who had received HIV care at the IAM over the same time period as the Rango sample. Comparisons by sample on socio-demographic characteristics revealed no statistically significant differences between the Rango and the matched patient samples by race/ethnicity, age group or viral suppression; however, a larger percentage of women enrolled in Rango compared to the matched sample (40.5% vs. 32.5%, respectively; χ2 = 5.54, p = .019).

Results

presents sociodemographic characteristics for the Rango pilot study participants (n = 406). The Rango sample was predominantly 50 years of age or older (63%; M = 50.67; SD = 10.97, 23–82), Black/African-American (44%) or Hispanic/Latinx (38%), and male (59%). Participants reported their residence throughout the five boroughs of NYC with 12% being unstably housed. Most participants reported Internet access via their phone (77%) or home computer (11%). Between-group comparisons showed that compared to men, more women reported being 50 years of age or older (72% vs. 57%) and living with family (40% vs. 16%), but no statistically significant differences were found for comparisons by race/ethnicity or age groups.

Table 1 Participant characteristics (n = 406)

To further describe the sample of patients who received the Rango intervention, a substantial number of participants had a history of substance use and mental health diagnoses. Data showed that 32%, 24% and 42% of Rango participants had a history of alcohol, drug or tobacco use, respectively. Compared to older participants, a greater number of participants younger than 30 consumed alcohol (52% vs. 31%; χ2 = 4.43) and used drugs (44% vs. 23%; χ2 = 4.91). Fewer Hispanics had a tobacco (25% vs. 37%; χ2 = 5.90), alcohol (36% vs. 46%; χ2 = 3.99) or drug use (17% vs. 29%; χ2 = 6.81) diagnosis compared to the other ethnic and racial groups. Almost half of the Rango participants (48%) had a psychiatric diagnosis with the most frequently diagnosed being unipolar (29%) and bipolar (8%) mood disorders, as well as anxiety disorder (14%). No statistically significant differences were found in psychiatric diagnosis by ethnic or racial, gender and age groups, except that anxiety was diagnosed among a greater number of White participants compared to the other groups combined (29% vs. 13%; χ2 = 4.94).

At baseline, 18% of the Rango participants reported missing at least one dose of ART in the prior three days. No significant bivariate associations were found between missed medications and demographic characteristics. Reports of missed medications were not independently associated with alcohol, drug or tobacco use or having any mental health diagnosis. However, missed doses were associated with lower patient activation. While the majority of the sample scored high on the PAM with 43% taking action regarding their healthcare (level 3) and 29% maintaining their engagement in care (level 4), a greater number of participants who scored lower on the PAM (levels 1 and 2) reported a missed dose compared to those whose scores were categorized as levels 3 and 4 (27% vs. 15%; χ2 = 7.71). Adjusted odds ratios are presented in for missed doses for each PAM level in comparison to level 4 after adjusting for all of the other variables in the model. Chart reviews of recent VL at the time of enrollment in Rango (within 90 days of the baseline date) showed that nearly 82% of participants were virally suppressed at baseline. Adjusted odds ratios for viral suppression are presented in , and unsurprisingly, reports of missed medications were associated with an unsuppressed viral load. The odds of high viremia were 3.44 times higher among those reporting missing doses compared to those who did not (95% CI: 1.77–6.66). While alcohol and drugs use did not independently predict viral suppression, the odds of viral suppression were lower among those with a history of tobacco use ().

Table 2 Logistic regressions predicting missed medication and suppressed viral load

Most participants reported that they liked the Rango program and found it acceptable. Participants provided a grade rating indicating how much they liked the program; 92% and 94% gave Rango an A or B grade at the 3- and 6-month mark, respectively. Participants logged in (with 1/3 logging in 10 or more times) and used most of the features (medication notices, appointment notices, Q&A messages, articles visited, chats joined, posts made). Overall, the Rango participants were engaged in care; 95% (387 out of 406) of the Rango patients returned for a medical follow-up visit, including 65 (92%) of the 71 unsuppressed patients at baseline. A McNemar's test to examine pre-post change in VL reclassification showed a statistically significant difference in the proportion of unsuppressed participants who were suppressed after participation in Rango (χ2 = 7.27, p = .006; OR = 1.59, 95%CI: 1.17–2.15). Of the 65 unsuppressed patients at baseline who attended a follow-up medical appointment, 38 (59%) achieved viral suppression; however, despite being at risk for ART non-adherence (an eligibility criterion), only a small percentage of the suppressed group at baseline with a clinical follow-up appointment showed increases in VL at 6 months (17 of 321; 5%)

To further evaluate Rango’s preliminary efficacy in improving HIV outcomes, we conducted comparisons in viral suppression between the Rango participants and the matched patients not enrolled in Rango (n = 403) to examine changes over a similar timeframe to our follow-up period in Rango (baseline and 6 months). Viral suppression among patients receiving HIV care as usual increased by 5 percentage points from 82% at the first time point to 87% 6 months later similar to Rango participants from 83% at baseline to 88% at 6 months. Of the 71 patients in the matched sample with a baseline detectable viral load, 32 patients (45%) were suppressed at 6 months similar to the unsuppressed patients in the Rango cohort (38 of the 71, 54%) who achieved suppression at 6 months. GEE analysis to account for multiple observations showed that the odds of viral suppression was similar between Rango participants and patients receiving treatment as usual (OR = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.75–1.46, Wald χ2 = 0.08, p = .84) and increased overall in both samples at the 6-month observation (OR = 1.48; 95% CI: 1.21–1.80, Wald χ2 = 15.12, p < .001).

Discussion

This pilot study used a single-arm prospective design to test an mHealth intervention developed for PWH who reported difficulties with medication adherence or were identified as being at risk for non-adherence. Rango aimed to improve engagement in care and treatment adherence through text-based reminders for medical appointments and medication adherence. It also sought to facilitate social support by leveraging anonymous peer-to-peer interactivity via discussion boards and virtual support groups that were moderated by a Health Coach. Clinical data indicated that participants had significant reductions in viral load following access to the Rango intervention for 6 months. Among virally unsuppressed participants, our pilot study showed that over 92% showed for their follow-up medical appointment and of these, more than half achieved viral suppression. However, comparisons of viral load between Rango participants and a similar cohort of patients receiving standard treatment over the same time period at the IAM showed that viral suppression was similar to those with Rango access.

Despite promising results and enthusiasm about mHealth interventions in improving HIV outcomes and in their ability to be scaled widely across diverse care contexts, much of the evidence demonstrates support for medication adherence but only a few trials have shown improvements in virologic outcomes.Citation4,Citation14,Citation15,Citation23,Citation34,Citation55 While there are a few rigorous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have demonstrated efficacy of technology-based interventions in reducing viral load, there is a lack of integrated interventions within HIV primary care that have an impact on viral suppression.Citation15,Citation56 A recent clinic-based trial with nearly 2000 unsuppressed patients receiving care at six HIV primary clinics found no evidence that a combination of a computer-based intervention and face-to-face health coaching was superior to standard care in reducing viral load.Citation57 The authors attributed the lack of an effect beyond standard care services to the extensive resources and services (adherence counseling and care coordination to address mental health and substance misuse) that were part of usual care at the clinics in their trial and considered the possibility of proactively engaging providers in the computerized component of the intervention as a way to share patients’ responses to the intervention and improve support for treatment. In the context of primary care, technologies that can be used to improve communication among medical staff and their patients between primary care visits could help to address several barriers to care and facilitate tailored services to better address patient needs and engage them in care.Citation15,Citation56

While a growing body of research on mHealth interventions shows potential improvement in retention in HIV care, ART adherence and HIV outcomes,Citation19,Citation58–62 mHealth technologies have not been integrated in the provision of HIV primary care,Citation20,Citation25 at least relative to the roles case management, care coordination and patient navigation services have played, and few interventions have been developed for use by clinic staff in working with patients who are struggling to keep their medical appointments or to adhere to their treatment regimen. An exception is PositiveLinks, a smartphone app designed for use by outpatient clinics serving PWH, and a recent pilot study showed that retention in care and HIV outcomes significantly improved at the 6- and 12-month follow-up period.Citation15 The authors argued that a combination approach that is dynamic and socially interactive that prioritizes human connections rather than an impersonal computer-based or “stand-alone” intervention is what likely contributed to improvements in outcomes. Similar to the PositiveLinks intervention, Rango was designed to serve as an mHealth tool to clinicians serving patients in outpatient clinics and to be available to patients on an ongoing basis outside of their medical appointments. Our preliminary findings may be attributable to several intervention components. The Rango mHealth intervention incorporated access to up-to-date HIV and health information, ongoing self-monitoring of adherence to both medications and medical appointments, a social network interface to facilitate peer encouragement and support, and access to a Health Coach to provide care support and allow for consultations as patient needs arose.

The results of our study are preliminary, and there were several important limitations that need to be noted. This was a pilot trial without the rigor of a full scale randomized controlled trial with a control group and appropriately powered for statistical analysis that makes it possible to infer causation and that is necessary to meet CDC’s criteria for evidence-based interventions.Citation63 It is also important to note that 82% of the participants in the Rango pilot study were virally suppressed at baseline, mirroring the patient population in care at the IAM clinical settings. As such, while our ability to detect the intervention’s efficacy in reducing viral load was limited, it is remarkable that 95% maintained viral suppression at follow up given that many of the Rango participants had been identified by their providers as being at risk for non-adherence. The matched sample of patients receiving usual care were not identified as being at risk for non-adherence. Additionally, because the pilot study was conducted as part of a larger implementation effort in the NYC area whereby over 4,000 patients were enrolled in Rango, due to concerns about burden on patients and clinic staff, it was not possible to include a comprehensive behavioral assessment to evaluate possible intervention mechanisms on adherence supports and care engagement. Additionally, we were not powered statistically to conduct any subgroup comparisons, in terms of differences by ethnic or racial background, substance use, among other factors to assess whether some groups benefitted more from the intervention than other groups.

A major limitation of this study involved a lack of data on Rango’s use (e.g., time spent logged in, features accessed) and a lack of assessment of its usability beyond the six months. Analysis of changes in usage over the six months was also not possible; thereby, limiting any inference about its potential to facilitate sustained engagement in care, medication adherence or viral suppression. It was also not possible to carefully assess Rango usage and evaluate how usage of different components of the intervention might have a direct impact on HIV-related outcomes. Related to this point is the possibility that the compensation schedule to offset Internet connectivity costs per month of active utilization of the Rango program over the six months could have influenced participant motivation to use the Rango program and without the compensation, utilization could be lower among patients receiving HIV care more generally.

Despite these limitations, the results of this pilot study provide a basis for a prospective randomized controlled trial to rigorously test the Rango intervention in improving HIV treatment outcomes among patients who are unsuppressed or have problems with ART adherence. Given the flexibility of the platform in which the Rango mHealth intervention was developed, tailoring the intervention components to meet the specific needs of patients and integrating roles for clinical care staff to engage with patients between primary care appointments are key advantages for its adaptability to the unique HIV clinical care setting. Our findings support efforts to continue to test this innovative approach in addressing ART non-adherence and viral suppression particularly to reach HIV treatment goals, which remains a critical public health priority.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript and final approval of the submitted version. All authors contributed to the design of work (AV, EKL, JB, RR, MC, JAA) and/or acquisition of data (AV, JB, CEA, BAD, EF) and/or analysis of data (AV, EMKL, JB, BAD, EF, JAA).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants of this study for their time and effort. This study was funded by Grant 1C1CMS331353 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The research presented here was conducted by the awardee. Findings might or might not be consistent with or confirmed by the findings of the independent evaluation contractor.

Disclosure statement

JAA has received research grants and personal fees for scientific advisory boards from Gilead, Merck, Janssen and Viiv outside the submitted work. She receives research grants from Atea, Frontier Technology, Pfizer and Regeneron outside the submitted work. She has received personal fees for scientific advisory board from Theratech. EKL received consulting fees from GSK and was paid to serve on a medical advisory board for ViiV. MC was paid to serve as advisory board member for Gilead Sciences and for ViiV. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ana Ventuneac

Ana Ventuneac, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Division of Infectious Diseases, New York, NY, USA. Her research interests include the intersection of digital technologies, identity, social connectedness, and well being.

Emma Kaplan-Lewis

Emma Kaplan-Lewis, MD, is an Assistant Clinical Professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Division of Infectious Diseases, New York, NY, USA. She has clinical and research interests in HIV and has worked on evaluating cardiovascular disease prevalence and risk assessment among persons with HIV.

Jessamine Buck

Jessamine Buck, MA, is Assistant Vice President of Strategy and Innovation at VillageCare, New York, NY, USA. She serves in a strategic projects and planning capacity for VillageCare’s corporate strategy department. She has over 10 years of experience in managed care and community-based care, with a focus on patient engagement, patient experience and innovative care delivery models.

Randi Roy

Randi Roy, MBA, is Chief Strategy Officer at VillageCare, New York, NY, USA. She has served as a senior health care executive and has more than 25 years of experience as a change leader with expertise in strategic planning, business and program development and care delivery transformation.

Caitlin E. Aberg

Caitlin E. Aberg, BA, was a research assistant at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Division of Infectious Diseases, New York, NY, USA. Her research interests include behavioral interventions to improve HIV outcomes.

Bianca A. Duah

Bianca A. Duah, BA, was a research assistant at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Division of Infectious Diseases, New York, NY, USA. Her research interests include behavioral interventions to improve HIV outcomes. She is currently enrolled in medical school.

Emily Forcht

Emily Forcht, BS, was a research assistant at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Division of Infectious Diseases, New York, NY, USA. Her research interests include behavioral interventions to improve HIV outcomes. She is currently enrolled in a school psychology doctoral program.

Michelle Cespedes

Michelle Cespedes, MD, is an Associate Professor of Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Division of Infectious Diseases, New York, NY, USA. Her research areas of interest are complications and comorbidities of HIV, with an emphasis on HPV, HIV related women's health issues, and HIV prevention in high risk populations.

Judith A. Aberg

Judith A. Aberg, MD, is Dr. George Baehr Professor of Clinical Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Division of Infectious Diseases, New York, NY, USA and serves as Chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases for Mount Sinai Health System. She is a nationally renowned researcher in the field of HIV and AIDS and has been instrumental in developing national, state, and local guidelines for HIV prevention and the care of HIV-infected persons.

References

- Bain LE, Nkoke C, Noubiap JJN. UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020 are not realistic: comment on "Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades”. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(2):e000227.

- Levi J, Raymond A, Pozniak A, Vernazza P, Kohler P, Hill A. Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(2):e000010.

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, HPTN 052 Study Team, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):830–839.

- Kanters S, Park JJ, Chan K, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(1):e31–e40.

- Gare J, Kelly-Hanku A, Ryan CE, et al. Factors influencing antiretroviral adherence and virological outcomes in people living with HIV in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. PLoS One 2015;10(8):e0134918.

- Henny KD, Wilkes AL, McDonald CM, Denson DJ, Neumann MS. A rapid review of eHealth interventions addressing the continuum of HIV care (2007-2017). AIDS Behav. 2018;22(1):43–63.

- Jiamsakul A, Kerr SJ, Kiertiburanakul S, et al. Early suboptimal ART adherence was associated with missed clinical visits in HIV-infected patients in Asia. AIDS Care. 2018;30(12):1560–1566.

- Jones AS, Lillie-Blanton M, Stone VE, et al. Multi-dimensional risk factor patterns associated with non-use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(5):335–342.

- Meresse M, March L, Kouanfack C, Stratall ANRS 12110/ESTHER Study Group, et al. Patterns of adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV drug resistance over time in the S tratall ANRS 12110/ESTHER trial in C ameroon. HIV Med. 2014;15(8):478–487.

- Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Cole SR, et al. Beyond core indicators of retention in HIV care: missed clinic visits are independently associated with all-cause mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(10):1471–1479.

- Sheehan DM, Fennie KP, Mauck DE, Maddox LM, Lieb S, Trepka MJ. Retention in HIV care and viral suppression: individual-and neighborhood-level predictors of racial/ethnic differences, Florida, 2015. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2017;31(4):167–175.

- Christopoulos KA, Riley ED, Carrico AW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a text messaging intervention to promote virologic suppression and retention in care in an urban safety-net human immunodeficiency virus clinic: the Connect4Care trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(5):751–759.

- Demena BA, Artavia-Mora L, Ouedraogo D, Thiombiano BA, Wagner N. A systematic review of mobile phone interventions (SMS/IVR/Calls) to improve adherence and retention to antiretroviral treatment in low-and middle-income countries. AIDS Patient Care Stds. 2020;34(2):59–71.

- Devi BR, Syed-Abdul S, Kumar A, et al. mHealth: an updated systematic review with a focus on HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis long term management using mobile phones. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;122(2):257–265.

- Dillingham R, Ingersoll K, Flickinger TE, et al. PositiveLinks: a mobile health intervention for retention in HIV care and clinical outcomes with 12-month follow-up. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(6):241–250.

- Erguera XA, Johnson MO, Neilands TB, et al. WYZ: a pilot study protocol for designing and developing a mobile health application for engagement in HIV care and medication adherence in youth and young adults living with HIV. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e030473.

- Fan X, She R, Liu C, et al. Evaluation of smartphone APP-based case-management services among antiretroviral treatment-naïve HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a randomized controlled trial protocol . BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):85.

- Hirshfield S, Downing MJ, Chiasson MA, et al. Evaluation of sex positive! A video eHealth intervention for men living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(11):3103–3118.

- Horvath KJ, Alemu D, Danh T, Baker JV, Carrico AW. Creating effective mobile phone apps to optimize antiretroviral therapy adherence: perspectives from stimulant-using HIV-positive men who have sex with men. JMIR mHealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e48.

- Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, Rosser BS, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of an online peer-to-peer social support ART adherence intervention. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2031–2044.

- Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838–1845.

- Muessig KE, LeGrand S, Horvath KJ, Bauermeister JA, Hightow-Weidman LB. Recent mobile health interventions to support medication adherence among HIV-positive MSM. Curr Opin HIV Aids. 2017;12(5):432–441.

- Muessig KE, Nekkanti M, Bauermeister J, Bull S, Hightow-Weidman LB. A systematic review of recent smartphone, Internet and Web 2.0 interventions to address the HIV continuum of care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(1):173–190.

- Mulawa MI, LeGrand S, Hightow-Weidman LB. eHealth to enhance treatment adherence among youth living with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(4):336–349.

- Navarra A-MD, Gwadz MV, Whittemore R, et al. Health technology-enabled interventions for adherence support and retention in care among US HIV-infected adolescents and young adults: an integrative review. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(11):3154–3171.

- Whiteley L, Brown LK, Mena L, Craker L, Arnold T. Enhancing health among youth living with HIV using an iPhone game. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup4):21–33.

- Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Korthuis PT, Gebo KA, Network HR, HIV Research Network. Establishment, retention, and loss to follow-up in outpatient HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(3):249–259.

- Quintana Y, Martorell EAG, Fahy D, Safran C. A systematic review on promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients using mobile phone technology. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(2):450–466.

- Rebeiro PF, Abraham AG, Horberg MA, et al. Sex, race, and HIV risk disparities in discontinuity of HIV care after antiretroviral therapy initiation in the United States and Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(3):129–144.

- Corless IB, Hoyt AJ, Tyer-Viola L, et al. 90-90-90-Plus: Maintaining adherence to antiretroviral therapies. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(5):227–236.

- Puig J, Echeverría P, Lluch T, et al. A specific mobile health application for older HIV-infected patients: usability and patient's satisfaction [published online ahead of print, July 13, 2020]. Telemed e-Health 2020. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0098

- Catalani C, Philbrick W, Fraser H, Mechael P, Israelski DM. mHealth for HIV treatment & prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Open AIDS J. 2013;7:17–41.

- Hamine S, Gerth-Guyette E, Faulx D, Green BB, Ginsburg AS. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(2):e52.

- Mayer JE, Fontelo P. Meta-analysis on the effect of text message reminders for HIV-related compliance. AIDS Care. 2017;29(4):409–417.

- Canan CE, Waselewski ME, Waldman ALD, et al. Long term impact of PositiveLinks: clinic-deployed mobile technology to improve engagement with HIV care. PloS One. 2020;15(1):e0226870.

- Flickinger TE, Ingersoll K, Swoger S, Grabowski M, Dillingham R. Secure messaging through PositiveLinks: examination of electronic communication in a clinic-affiliated smartphone app for patients living with HIV. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(3):359–364.

- Mugavero MJ, Norton WE, Saag MS. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl_2):S238–S246.

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):462–473.

- Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, Emmanuel P, Zingman BS, Horberg MA, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(1):1–10.

- Günthard HF, Aberg JA, Eron JJ, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2014 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA 2014;312(4):410–425.

- NYSDOH AIDS Institute. The HIV Clinical Guidelines Program – adult HIV and related guidelines. https://www.hivguidelines.org/. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026.

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M. Do Increases in Patient Activation Result in Improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1443–1463.

- Marshall R, Beach MC, Saha S, et al. Patient activation and improved outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(5):668–674.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207–214.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J, Sacks R, Overton V, Parrotta CD. Adding a measure of patient self-management capability to risk assessment can improve prediction of high costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(3):489–494.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J, Shi Y, Mittler J, Scanlon D. Taking the long view: how well do patient activation scores predict outcomes four years later? Med Care Res Rev. 2015;72(3):324–337.

- US DHHS. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Washington, DC: DHHS; 2016.

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. 2002. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2002:267–313.

- McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika 1947;12(2):153–157.

- Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73(1):13–22.

- Lipsitz SR, Laird NM, Harrington DP. Generalized estimating equations for correlated binary data: using the odds ratio as a measure of association. Biometrika 1991;78(1):153–160.

- Zeger SL, Liang K-Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986;42(1):121–130.

- Ballinger GA. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organ Res Methods. 2004;7(2):127–150.

- Anglada-Martinez H, Riu-Viladoms G, Martin-Conde M, Rovira-Illamola M, Sotoca-Momblona JM, Codina-Jane C. Does mHealth increase adherence to medication? Results of a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(1):9–32.

- Dillingham R. Design and impact of positive links: a mobile platform to support people living with HIV in Virginia. Paper presented at: International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence, International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (IAPAC), Miami, FL; 2017.

- Marks G, O’Daniels C, Grossman C, et al. Evaluation of a computer-based and counseling support intervention to improve HIV patients' viral loads. AIDS Care. 2018;30(12):1605–1613.

- Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):Art. No. CD009756.

- Ingersoll K, Dillingham R, Reynolds G, et al. Development of a personalized bidirectional text messaging tool for HIV adherence assessment and intervention among substance abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46(1):66–73.

- Kempf M-C, Huang C-H, Savage R, Safren SA. Technology-delivered mental health interventions for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA): a review of recent advances. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(4):472–480.

- Rana AI, van den Berg JJ, Lamy E, Beckwith CG. Using a mobile health intervention to support HIV treatment adherence and retention among patients at risk for disengaging with care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30(4):178–184.

- Rosen RK, Ranney ML, Boyer EW. Formative research for mhealth HIV adherence: the iHAART app. Paper presented at: 2015 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), 2015.

- CDC. Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention. Retrieved December 2015;2(2016).