Abstract

Background: Older adults living with HIV (OALWH) are a growing population facing unique challenges to successful antiretroviral therapy.

Objective: To assess efficacy and safety profiles of antiretroviral regimens, including those containing dolutegravir, in OALWH.

Methods: Combined data from 6 phase III/IIIb trials in treatment-naive (ARIA, FLAMINGO, SINGLE, SPRING-2; N = 2634) and treatment-experienced (DAWNING, SAILING; N = 1339) participants receiving dolutegravir- or non–dolutegravir-based regimens were analyzed by age (<50, ≥50 to <65, and ≥65 years). Baseline data included comorbidities and numbers of concomitant medications. Week 48 efficacy outcomes included virologic response (HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL) and CD4+ cell count change from baseline. Safety outcomes included incidence of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, and AE-related withdrawals.

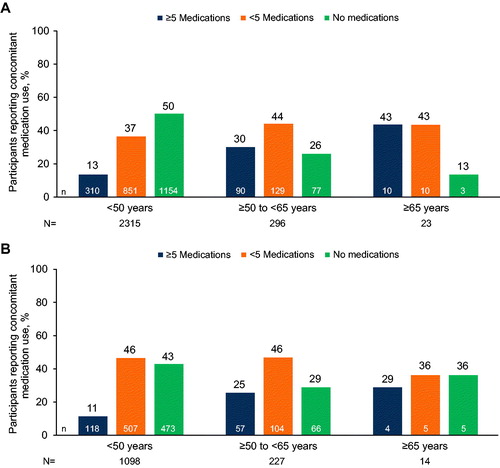

Results: Use of ≥5 concomitant medications was more frequently reported among treatment-naive and treatment-experienced participants aged ≥50 to <65 (30% [90/296] and 25% [57/227], respectively) and ≥65 years (43% [10/23] and 29% [4/14]) than among those aged <50 years (13% [310/2315] and 11% [118/1098]). Comorbidities were more prevalent in the older age groups. For dolutegravir-based regimens, Week 48 rates of virologic response and change in CD4+ cell count were similar across age groups (treatment naive, 80–87% and 234–251 cells/mm3; treatment experienced, 70–100% and 105–156 cells/mm3, respectively). There were no major differences in safety outcomes in each age group.

Conclusions: In these analyses of combined phase III/IIIb trial data, efficacy and safety of dolutegravir-based regimens were generally similar across age groups in treatment-naive or treatment-experienced participants. Polypharmacy and comorbidities were more common among OALWH than those aged <50 years.

Introduction

The lifespan of people living with HIV (PLWH) has increased as a consequence of better access to healthcare and availability of more effective treatment options. PLWH aged >50 years are considered older adults living with HIV (OALWH).Citation1 The availability and success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is a major driver of the growing population of OALWH.Citation2 Along with advances in ART, other factors that have contributed to this phenomenon are the decreasing incidence of HIV among younger adults and a higher prevalence of sexual risk behavior among people aged >50 years than was previously known.Citation3

There are approximately 3.6 million OALWH, and they make up ∼10% of the worldwide population of PLWH.Citation2 However, this number has been globally rising, with the percentage of OALWH in the United States increasing from 51% in 2018Citation4 to an expected level of 73% by 2030.Citation5 Similar but delayed trends have been observed in lower- to middle-income countries.Citation2

In addition to the management of HIV, OALWH face significant healthcare challenges such as disjointed medical care and an increased burden of comorbidities and, hence, multimorbidity. Comorbidities frequently include cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome, which may influence the choice of ART regimen because of potential impacts on adverse effects and drug clearance.Citation2,Citation6,Citation7 The polypharmacy associated with multimorbidity necessitates the consideration of potential drug–drug interactions as a further challenge.Citation2,Citation6,Citation7 Older adults also exhibit reduced CD4 responses with ART that may be associated with increased clinical progression and risk of further comorbidities.Citation2,Citation7 Therefore, understanding the efficacy and safety of ART regimens in OALWH is becoming increasingly important as this population grows. However, age-dependent outcomes remain inadequately explored in OALWH.

Dolutegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) approved in 2013, is indicated in combination with other antiretroviral agents for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced adults.Citation8 Here, we reviewed pooled data from 6 phase III/IIIb clinical trials that were conducted between 2010 and 2017 and included 2634 treatment-naive and 1339 treatment-experienced PLWH. Our objectives were to evaluate the representation of OALWH in clinical trials of dolutegravir-based regimens and to assess whether clinical efficacy and safety findings in OALWH are consistent with or divergent from findings in younger PLWH.

Materials and methods

Clinical trials

We analyzed data from 6 phase III/IIIb clinical trials that investigated the efficacy and safety of dolutegravir 50 mg once daily in adults: the ARIA, FLAMINGO, SINGLE, SPRING-2, DAWNING, and SAILING studies. The designs and methodologies for these trials have been described previously (see Supplemental Table 1 for details).Citation9–14 All the trials were non-inferiority studies and randomized participants 1:1 to receive either dolutegravir-based or comparator-based ART. Comparators were atazanavir/ritonavir in ARIA, darunavir/ritonavir in FLAMINGO, efavirenz in SINGLE, lopinavir/ritonavir in DAWNING, and raltegravir in SPRING-2 and SAILING. In the ARIA study, the fixed-dose combination tablet of dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine was used. In FLAMINGO, SINGLE, and SPRING-2, dolutegravir was administered as a single active preparation in combination with abacavir/lamivudine or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine. In DAWNING and SAILING, dolutegravir was administered with investigator-selected background therapy.

The treatment-naive analysis population included participants in ARIA (≤10 days of prior ART), FLAMINGO, SINGLE, and SPRING-2. The treatment-experienced analysis population included participants in DAWNING and SAILING. Participants in DAWNING had documented treatment failure with a first-line regimen of 1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor plus 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), were naive to protease inhibitors and INSTIs, and received an investigator-selected dual NRTI background regimen for second-line treatment (including at least 1 fully active NRTI based on genotypic resistance testing at screening). Participants in SAILING were treatment experienced but naive to integrase inhibitors, had resistance to ≥2 classes of antiretroviral drugs, and had background therapy with 1 to 2 fully active agents. For all 6 studies, all participants provided written informed consent before undergoing study procedures, and ethics committee approval was obtained at all participating centers in accordance with the principles of the 2008 Declaration of Helsinki.

Outcomes

All outcomes were analyzed separately for the treatment-naive population and the treatment-experienced population, each stratified into 3 subgroups based on age at baseline: <50, ≥50 to <65, and ≥65 years. Baseline clinical characteristics included US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classification of HIV infection, HIV-1 RNA level, CD4+ cell count, concomitant medication use, and common comorbidities. Following common convention, polypharmacy was defined as use of 5 or more concomitant medications.Citation15 Efficacy outcomes included the proportions of participants with plasma HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL (defined as virologic response using the US Food and Drug Administration Snapshot algorithm) at Week 48 and change from baseline in CD4+ cell count at Week 48. Safety outcomes included the incidence of adverse events (AEs) and withdrawals due to AEs. Descriptive statistics were used for all outcomes.

Due to low participant numbers in the ≥50 to <65 and ≥65 years age groups, unadjusted virologic response rates for age groups were estimated using a fixed-effects meta-analysis inverse-variance weighted combination of individual study estimates within 2 age groups (<50 and ≥50 years). Heterogeneity for treatment regimen-by-study interaction was assessed using Cochran’s Q test.

Results

Baseline

A total of 3973 participants from 6 clinical trials were included in these analyses, 2634 treatment-naive participants from ARIA, FLAMINGO, SINGLE, and SPRING-2 (including 319 [12%] OALWH) and 1339 treatment-experienced participants from DAWNING and SAILING (including 241 [18%] OALWH). Baseline disease characteristics were generally similar across age strata and between dolutegravir and non-dolutegravir groups ( and Supplemental Table 2). In both pooled data sets, most study participants were men (treatment naive, 69%; treatment experienced, 66%). Among treatment-naive participants, 70% were of white race and 23% were of African American or African heritage. Among treatment-experienced participants, 39% were of white race and 41% were of African American or African heritage.

Table 1. Pooled baseline HIV disease characteristics stratified by age group in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced participants.Table Footnotea

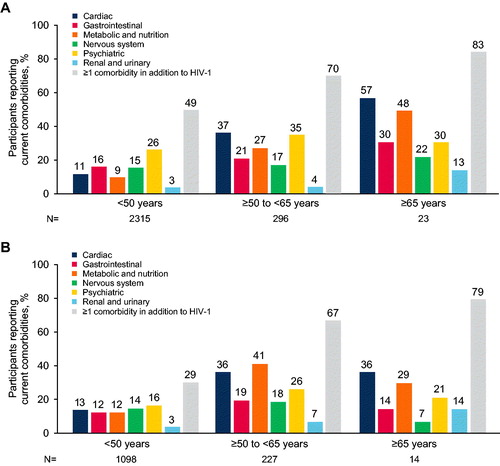

In both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced populations, the use of concomitant medications was reported more frequently among participants aged ≥50 to <65 years and ≥65 years than among those aged <50 years (, respectively). Additionally, multimorbidity (at least one comorbidity in addition to HIV) was reported for a greater proportion of both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced participants aged ≥50 to <65 years and ≥65 years than participants aged <50 years (). Similarly, the prevalence of common comorbidities was generally higher in participants aged ≥50 to <65 years and ≥65 years than those aged <50 years for both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced participants (, respectively). The largest differences between age groups were seen for cardiac and metabolic/nutrition disorders. For example, hypertension was reported for 101/296 (34%) treatment-naive and 72/227 (32%) treatment-experienced participants aged ≥50 to <65 years and 13/23 (57%) treatment-naive and 4/14 (29%) treatment-experienced participants aged ≥65 years compared with 187/2315 (8%) treatment-naive and 110/1098 (10%) treatment-experienced participants aged <50 years. Type 2 diabetes was reported for 31/296 (10%) treatment-naive and 26/227 (11%) treatment-experienced participants aged ≥50 to <65 years and 6/23 (26%) treatment-naive and 1/14 (7%) treatment-experienced participants aged ≥65 years compared with 33/2315 (1%) treatment-naive and 18/1098 (2%) treatment-experienced participants aged <50 years.

Efficacy

Treatment-naive participants

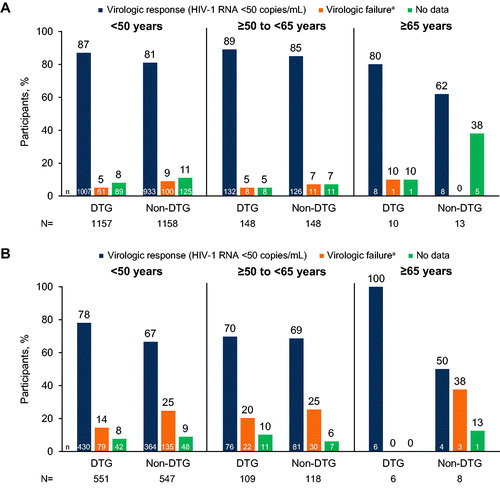

For dolutegravir-based regimens, rates of virologic response were similar across age groups (<50 years: 87% [1007/1157]; ≥50 to <65 years: 89% [132/148]; ≥65 years: 80% [8/10]; ). For non–dolutegravir-based regimens, the response rate in the ≥65 years group (62% [8/13]) was numerically lower than in the age <50 years (81% [933/1158]) and ≥50 to <65 years (85% [126/148]) groups; however, the number of participants aged ≥65 years was low. The efficacy meta-analysis (which combined the 2 older age groups) showed that virologic response rates were significantly higher in the dolutegravir group than in the non-dolutegravir group for study participants aged <50 years (treatment difference, 6.2%; 95% CI: 3.3, 9.1; P < 0.0001) but not for those aged ≥50 years (treatment difference, 5.1%; 95% CI: −2.4, 12.6; P = 0.1819; Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 3. Combined Snapshot virologic outcomes at Week 48 in (A) treatment-naive and (B) treatment-experienced participants in phase III/IIIb trials of dolutegravir-based regimens stratified by age. ART, antiretroviral therapy; DTG, dolutegravir. aVirologic failure includes HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies/mL, discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or other reason, or change in ART.

Mean (SD) change from baseline in CD4+ cell count was generally similar across all 3 age groups in the dolutegravir group (<50 years: 250.7 [180.4] cells/mm3; ≥50 to <65 years: 249.6 [183.9] cells/mm3; ≥65 years: 234.1 [120.1] cells/mm3). In the non-dolutegravir group, mean (SD) change from baseline in CD4+ cell count was similar in the <50 years (230.0 [176.6] cells/mm3) and ≥50 to <65 years groups (235.9 [168.6] cells/mm3) but comparatively lower in the ≥65 years group (112.6 [301.5] cells/mm3).

Treatment-experienced participants

In treatment-experienced participants, rates of virologic response were high across age groups for dolutegravir-based regimens (<50 years: 78% [430/551]; ≥50 to <65 years: 70% [76/109]; ≥65 years: 100% [6/6]; ). Response rates for non–dolutegravir-based regimens were numerically lower in the age ≥65 years group (50% [4/8]) than in the age <50 years (67% [364/547]) and ≥50 to <65 years (69% [81/118]) groups; however, the number of participants aged ≥65 years was low. In the efficacy meta-analysis, virologic response rates were significantly higher in the dolutegravir groups than in the non-dolutegravir groups for those aged <50 years (treatment difference, 11.4%; 95% CI: 6.2, 16.6; P < 0.0001) but were not significantly different for those aged ≥50 years (treatment difference, 7.1%; 95% CI: −4.0, 18.3; P = 0.2095; Supplemental Table 3).

Mean (SD) change from baseline to Week 48 in CD4+ cell count was comparable between dolutegravir and non-dolutegravir regimen groups and in both groups was lower in the older age groups than in the <50 years group (<50 years: 155.8 [152.7] and 149.6 [124.6] cells/mm3; ≥50 to <65 years: 119.0 [119.9] and 120.7 [120.3] cells/mm3; ≥65 years: 105.2 [50.8] and 159.3 [125.8] cells/mm3, respectively).

Safety

Treatment-naive participants

Overall, rates of AEs were similar across age groups and between dolutegravir and non-dolutegravir groups (). For all age groups, participants in the non-dolutegravir group experienced more adverse drug reactions and AEs leading to withdrawal by Week 48 than those in the dolutegravir group.

Table 2. Combined safety outcomes at week 48 in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced participants.a

Treatment-experienced participants

Generally, rates of AEs were similar across age groups and between dolutegravir and non-dolutegravir groups (). For those aged <50 years and ≥50 to <65 years, rates of adverse drug reactions and AEs leading to withdrawal were more frequent in the non-dolutegravir regimen group than in the dolutegravir group. For those aged ≥65 years, rates of adverse drug reactions and AEs leading to withdrawal were similar in both treatment groups and were also similar to those observed in the younger age groups.

Discussion

In these analyses of pooled data from 6 phase III/IIIb clinical trials assessing the efficacy and safety of dolutegravir-based ART in 3973 PLWH (560 aged ≥50 years), virologic response (defined as HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL) at Week 48 was achieved in the majority of participants regardless of age or prior use of ART. In both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced study participants, response rates to dolutegravir-based ART were similar across all 3 age groups assessed: <50, ≥50 to <65, and ≥65 years. Response rates to non–dolutegravir-based ART were numerically lower in the oldest age group; however, participant numbers in these groups were too low to draw any meaningful conclusions. In contrast, changes from baseline to Week 48 in CD4+ cell counts were somewhat impacted by age, with smaller increases in the older age groups than in the younger age group, particularly in the treatment-experienced analysis population. These results are in line with previous observations that OALWH generally have rates of virologic response similar to those in younger PLWH but may have a reduced immunologic response to ART.Citation2,Citation7

Although combination ART regimens should be offered to all PLWH, special considerations for treatment of OALWH should factor in the possibility of underlying comorbidities and potential for drug–drug interactions with a higher degree of polypharmacy.Citation1,Citation2 In these analyses, increased age was associated with higher overall rates of concomitant medication use and more frequent comorbidities at baseline regardless of prior ART exposure. Further, regardless of prior treatment experience, the greatest drivers of cardiovascular and metabolic/nutrition comorbidities in OALWH were hypertension and type 2 diabetes, respectively. These findings are corroborated in literature, as these conditions are more common in PLWH and become more prevalent with aging.Citation2,Citation16 Multimorbidity and polypharmacy are crucial concerns for OALWH,Citation6 whether they are ART naive or ART experienced. The current analyses examined these factors as baseline characteristics only. Future studies should further explore the impact of ongoing polypharmacy during ART (ie, the impact of potential drug-drug interactions) on rates of virologic response in OALWH and should examine the effects of ART on comorbidities over time and by age strata.

Studies have shown minimal pharmacokinetic differences in PLWH aged 20 to 60 years receiving ART; further research is needed in individuals aged >60 years to determine if OALWH metabolize ART differently than younger PLWH.Citation17 Overall, results from our combined analyses suggest that dolutegravir-based regimens are efficacious and well tolerated in PLWH aged <50, ≥50 to <65 years, and ≥65 years who are treatment naive or treatment experienced. Notably, the safety profile of dolutegravir was comparable across age groups in treatment-naive or treatment-experienced participants.

Despite the rising numbers of OALWH, data on the efficacy and safety of ART regimens in populations aged ≥50 years are limited, and OALWH have historically been underrepresented in clinical trials.Citation18,Citation19 The proportions of OALWH in the clinical trials included in these analyses (12% in the treatment-naive population and 18% in the treatment-experienced population) were also not reflective of global or regional proportions of OALWH. In 2018, 17% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States occurred in people aged >50 years and over 50% of PLWH were aged >50 years.Citation5,Citation18 Results from a modeling study using data from a Dutch cohort of PLWH predicted that, in 2030, the median age of PLWH in the United States will increase to 56.6 years and the proportion of OALWH will increase to 73%.Citation5,Citation18 Further, the age of PLWH has been increasing in high-income countries, and similar trends are now being observed in lower- to middle-income countries.Citation2 There is clearly a need for greater inclusivity and representation of OALWH in clinical trials of dolutegravir and other antiretroviral agents. The US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, and International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use have recognized this need for inclusion of older adult participants in drug development trials,Citation20–22 and additional analyses detailing virologic response to current antiretroviral agents in aging populations are warranted in specific geographic subpopulations (eg, North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa), racial groups, and female and transgender populations.

These retrospective analyses were subject to several limitations. Most importantly, the small numbers of participants in the ≥65 years age groups restrict the interpretation of any outcome differences seen in this group. Differences between the clinical trials included in the analyses in terms of inclusion criteria and non-dolutegravir comparators also complicate the interpretation of differences between treatment groups and age groups. Additionally, because weight change was not a predefined endpoint, these analyses did not examine change in participant weight from baseline to Week 48. Obesity increases in prevalence with age and is a contributing factor to both hypertension and diabetes, particularly in PLWH.Citation2 Cohort studies suggest that dolutegravir is not associated with significant weight gain in OALWH,Citation23 but this should be confirmed in clinical trials and future studies should further examine the interaction of weight changes and ART regimens in OALWH. Lastly, in most of the trials (except ARIA), the number of female participants was limited. Future studies should expand recruitment to include older female participants, as women undergo menopause and may experience its associated symptoms (eg, vasomotor changes or changes to cognitive function or bone health) as well as potential drug-drug interactions between hormone replacement therapy and ART.Citation24 Taken together, we recommend expanding recruitment of future HIV clinical trials with older age groups to address clinical aspects specific to OALWH.

Conclusion

Older adults with HIV face unique challenges such as disjointed medical care and higher rates of polypharmacy and comorbidities compared with individuals without HIV. As the population of OALWH is growing, efficacious and safe treatments for HIV are crucial. Data from these combined analyses of 6 phase III/IIIb clinical trials, including 3973 PLWH (560 aged ≥50 years), indicate that OALWH experience an increased incidence of polypharmacy and more frequent comorbidities relative to younger PLWH. Results from these pooled analyses suggest that a dolutegravir-based regimen may be an effective option for OALWH, with high rates of virologic suppression and no observed differences in safety between older and younger PLWH in both ART-naive and ART-experienced treatment groups. However, the numbers of OALWH in these pooled data sets are not sufficiently large to draw definitive conclusions regarding efficacy and tolerability of dolutegravir in this group, and studies in larger groups of OALWH are needed.

Disclosure of interest

F.S., M.P., J.S., M.v.d.K., B.W., J.v.W., and A.C. are employees of ViiV Healthcare and own stock in GlaxoSmithKline. N.B. has no conflicts to disclose. R.G. is an employee of and owns stock in GlaxoSmithKline.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (404.2 KB)Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided under the direction of the authors by Deirdre Rodeberg, PhD, and Jennifer Rossi, MA, ELS, MedThink SciCom, and was funded by ViiV Healthcare.

Data availability statement

Anonymized individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Burgess MJ, Zeuli JD, Kasten MJ. Management of HIV/AIDS in older patients-drug/drug interactions and adherence to antiretroviral therapy . HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2015;7:251–264.

- Wing EJ. HIV and aging. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;53:61–68.

- Nideröst S, Imhof C. Aging with HIV in the era of antiretroviral treatment: living conditions and the quality of life of people aged above 50 living with HIV/AIDS in Switzerland. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2016;2:233372141663630. 2333721416636300.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and Older Americans. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html. Accessed September 29, 2020.

- Smit M, Brinkman K, Geerlings S, ATHENA observational cohort, et al. Future challenges for clinical care of an ageing population infected with HIV: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(7):810–818.

- Althoff KN, Smit M, Reiss P, Justice AC. HIV and ageing: improving quantity and quality of life. Curr Opin HIV Aids. 2016;11(5):527–536.

- Guaraldi G, Pintassilgo I, Milic J, Mussini C. Managing antiretroviral therapy in the elderly HIV patient. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(12):1171–1181.

- Tivicay [package insert]. Triangle Park, NC: ViiV Healthcare: Research; 2020.

- Aboud M, Kaplan R, Lombaard J, et al. Dolutegravir versus ritonavir-boosted lopinavir both with dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapy in adults with HIV-1 infection in whom first-line therapy has failed (DAWNING): an open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3b trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(3):253–264.

- Orrell C, Hagins DP, Belonosova E, ARIA study team, et al. Fixed-dose combination dolutegravir, abacavir, and lamivudine versus ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in previously untreated women with HIV-1 infection (ARIA): week 48 results from a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3b study. Lancet Hiv. 2017;4(12):e536–e546.

- Clotet B, Feinberg J, van Lunzen J, et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus darunavir plus ritonavir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (FLAMINGO): 48 week results from the randomised open-label phase 3b study. Lancet 2014;383(9936):2222–2231.

- Raffi F, Rachlis A, Stellbrink H-J, et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus raltegravir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48 week results from the randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority SPRING-2 study. Lancet 2013;381(9868):735–743.

- Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1807–1818.

- Cahn P, Pozniak AL, Mingrone H, extended SAILING Study Team, et al. Dolutegravir versus raltegravir in antiretroviral-experienced, integrase-inhibitor-naive adults with HIV: week 48 results from the randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority SAILING study. Lancet. 2013;382(9893):700–708.

- Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):989–995.

- Hadigan C, Kattakuzhy S. Diabetes mellitus type 2 and abnormal glucose metabolism in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43(3):685–696.

- Schoen JC, Erlandson KM, Anderson PL. Clinical pharmacokinetics of antiretroviral drugs in older persons. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(5):573–588.

- Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(3):453–472.

- Johnston RE, Heitzeg MM. Sex, age, race and intervention type in clinical studies of HIV cure: a systematic review. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2015;31(1):85–97.

- Cerreta F, Eichler H-G, Rasi G. Drug policy for an aging population—the European Medicines Agency's geriatric medicines strategy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1972–1974.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Inclusion of older adults in cancer clinical trials: guidance for industry. Silver Spring, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/135804/download. Accessed December 2, 2020.

- European Medicines Agency. ICH topic E 7: studies in support of special populations: geriatrics. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline. London, UK: European Medicines Agency, 1994. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-e-7-studies-support-special-populations-geriatrics-step-5_en.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2020.

- Guaraldi G, Calza S, Milic J, et al. Dolutegravir is not associated with weight gain in antiretroviral therapy experienced geriatric patients living with HIV. AIDS. 2021;35(6):939–945.

- Andany N, Kennedy VL, Aden M, Loutfy M. Perspectives on menopause and women with HIV. Int J Womens Health. 2016;8:1–22.