Abstract

Background

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic and associated containment measures dramatically affected the health care systems including the screening of human immunodeficiency virus and the management people living with HIV around the world by making the access to preventive care services and specific medical monitoring more difficult.

Objective

Objective: To study the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the holistic care of people living with HIV in Liège (Belgium).

Methods

Methods: In this retrospective observational study conducted in Liège University Hospital, we compared the out-patient follow-up of HIV-infected individuals as well as the number of new HIV diagnoses between 2019 and 2020 and between the different waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Results

Results: In 2020, when compared to 2019, we observed a significant decrease in the number of new HIV diagnoses, especially during the first wave of the pandemic, and in the number of consultations undertaken by sexual health services, psychologists and specialists in infectious diseases at our HIV clinic. We also observed a decrease in the number of viral load assays and blood CD4 + T-cells count analyses performed, although we found less patients with HIV plasma viral load above 400 copies per mL in 2020. Finally, we noted a significant reduction in terms of screening of our HIV-infected patients for hepatitis C, syphilis, colorectal and anal cancers and hypercholesterolemia.

Conclusions

Conclusions: Our experience exhibits the deleterious impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the HIV care and the need to implement new strategies to guarantee its continuum.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Its most severe complication is respiratory distress which often requires intensive care admission and mechanical ventilation.Citation1 Since its first report from Wuhan (China) in December 2019, COVID-19 has spread rapidly around the world, affecting more than 177 million people and responsible for more than 3.8 million deaths.Citation2 This pandemic and associated containment measures dramatically affected the health care systems including the screening of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the management of the 38 million people living with HIV (PLWH) around the world, including 18000 in Belgium, by making the access to preventive care services and specific medical monitoring more difficult.Citation3,Citation4 This concern was first highlighted in China bringing the World Health Organization (WHO), the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the Global Network for PLWH to work together in order to ensure the continuity of HIV-related services.Citation5

The COVID-19 pandemic increases the vulnerability of many populations who are at high risk of HIV infection or antiretroviral therapy (ART) interruption, due to lack of or limited access to psychosocial services, HIV prevention services, as well as clinical care and treatments. In addition, the intersection of HIV and COVID-19 pandemics could expose PLWH even more vulnerable to mental health issues including notably anxiety, substance use and depression.Citation6 Indeed, PLWH have faced stigma for decades and live under the burden of a chronic infection that might now represent a higher risk of COVID-19 mortality.Citation7,Citation8

In a previous report on the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV care in the province of Liège (Belgium), we observed a dramatic decrease in HIV screening tests and diagnoses during the first wave of the pandemic,Citation9 which could impede our progress towards reaching UNAIDS’s 90-90-90. According to Sciensano (the Belgian scientific institute for public health), Belgium was particularly affected by the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic with an incidence of up to 3422 cases per 100.000 inhabitants and the province of Liège was even considered as the epicenter of the second wave in Europe.Citation10

In this report, we will examine how successive waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and associated lockdown measures have affected the HIV care continuum in order to propose solutions to maintain an effective HIV prevention and care.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of HIV-infected patients attending at Liège University Hospital (Belgium) during 2019 and 2020. The observation period for each year extended from January to December. The COVID-19 pandemic was in three times spans: from March to May (corresponding to the first wave of pandemic in 2020), from June to September (corresponding to the period between the waves in 2020) and from October to December (corresponding to the second wave in 2020).

Variables studied included the number of new HIV diagnoses, the number of out-patient follow-up visits to a specialist in infectious diseases performed through in-person assessment or via telemedicine, the number of psychology or sexology consultations, the number of patients who underwent screening for comorbidities (including dyslipidemia and rectoscopy/colonoscopy appointment) and coinfections (chlamydia infections and gonorrhea, syphilis, hepatitis B and C), the number of blood CD4 + T-cells absolute count analyses and HIV plasma viral load (VL) assays performed, the HIV plasma VL value as well as the delay between the diagnosis and the management.

To study the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV detectable plasma VL, we kept only the patients who had at least one available viral load per year and we excluded the patients with new HIV diagnosis in order to avoid bias linked to the persistence of positive VL following treatment initiation.

This study was approved by our institutional Ethics Commitee. Informed consent was not obtained from the patients since the Ethics Commitee also provided a consent waiver for our study.

Statistical analysis

For quantitative variables, the analyses are reported using means, standard deviations (SD), medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) (25th to 75th quartile). For qualitative variables, the results are described using frequency tables (numbers and percent). In order to evaluate the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on HIV care, variables were compared between 2020 and 2019 as well as between the different periods of the pandemic. Poisson regression was modeled to analyze the impact of the pandemic on the number of new HIV diagnoses. The impact of the pandemic situation on the follow-up (numbers of consults, blood CD4+ cells count and VL) was analyzed using student t-test and non-parametric signed rank test for paired observations. Differences were considered statistically significant if the p-value (p) was less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS Statistical Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R (version 3.6.1) packages were used for the figures.

Results

New HIV diagnoses and medical care delays

In total, 48 new HIV diagnoses were registered at our center in 2019, which is in line with what was observed during the previous years (). In contrast, we found a drastic significant decrease in 2020 with only 26 new diagnoses (p < 0.01). Likewise, the median number of new HIV diagnoses per month was 3 in 2019 compared to 2 in 2020 (p < 0.05). Starting from March, this decrease in HIV diagnoses was consistent during the whole rest of the year, irrespective of the successive waves (). Among the 6 diagnoses made during the first wave (from March to May of 2020), only one was made in April and one in May; the other ones were diagnosed in March when the pandemic was just beginning to emerge (). Nevertheless, we did not observe any additional delay between the diagnosis and the medical care initiation in 2020 when compared to 2019 ().

Table 1 New HIV diagnoses

Table 2 New HIV diagnoses per month in 2019 and 2020

Table 3 Delay between the diagnosis and the management

Follow up and visits at our HIV out‐patients clinic

1278 HIV-infected patients were followed in 2019 compared to 1292 patients in 2020. Among them, 1162 patients were followed during both years. There were 104 new patients followed in our HIV out -patients clinic in 2019 compared to 93 patients in 2020.

Among 1292 patients followed in 2020, there were 130 additional patients compared to the previous year including 93 new patients and 37 patients who were not followed in 2019 but resumed their follow-up in 2020.

Concerning patients "lost to follow-up" during 2020, there were 116 patients followed in 2019 who weren’t in 2020 for different reasons: 12 patients have died, 37 patients were transferred in an another center, 13 patients were not seen in a medical consultation in 2020 because they have an appointment in early 2021, 50 patients were considered "lost to follow-up" after failing to contact them and 4 patients for which we have no information.

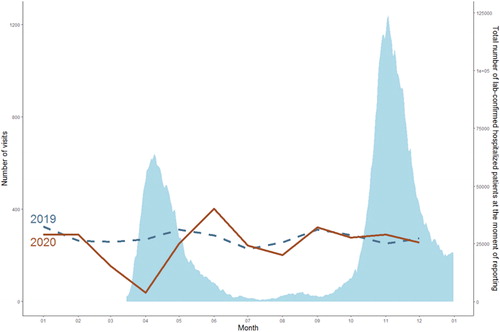

When focusing on the patients followed both in 2019 and 2020, we observed a significant decrease in term of visits at our out-patient HIV clinic in 2020 compared to 2019 (2548 versus 3088 medical visits respectively) corresponding to 3 medical visits per patient in 2019 and 2 in 2020 (p < 0.0001) (). This decrease was mainly concentrated during the first wave of the pandemic, with only 131 medical visits per month compared to 253 visits per month between the two waves and 203 per month during the second wave (p < 0.05). During the first wave, most of the medical consultations were cancelled by the hospital because of the implemented lockdown policies allowing only the continuation of consultations considered urgent. In contrast, there was no difference between the second wave, during which these policies were not applied, and the corresponding period in 2019 (). Thanks to the telemedicine program initiated at our hospital at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, a total of 163 consultations were performed through this new useful tool between April and December 2020 (, ).

Figure 1 Number of Covid-19 infected patients in hospital per day in 2020 in the Province of Liège and the total number of out-patient follow-up visits to a specialist in infectious diseases in Liege University Hospital. Number of confirmed Covid-19 infected patients in hospital per day in 2020 in the Province of Liège (Source: Sciensano)Citation11 and the total number of out-patient follow-up visits to a specialist in infectious diseases (including telemedicine) per month in 2019 (blue) and 2020 (red).

Table 4 Evolution of the total number of outpatient follow-up visits to a specialist in infectious diseases

In 2020, we also found a significant decrease in the number of consultations in psychology and sexology when compared to 2019. Indeed, 858 of these consultations were performed in 2019 versus only 480 in 2020, corresponding to a median of 73 and 52 consultations per month respectively (p < 0.001) (). Again, we found that this decrease involved mainly the first wave during which the number of consultations in psychology and sexology was significantly lower compared to the two other periods (median of 20 during the first wave, 61 between the waves and 32 during the second wave, p < 0.05) (). No psychology or sexology consultation was performed in April 2020.

Table 5 Psychology and sexology consultations

Blood CD4 + T-cells absolute count and HIV plasma viral load

Along with the reduction in terms of visits between 2019 and 2020, the number of routine VL assays and blood CD4 + T-cells count analyses followed a similar trend among patients followed both years (N = 1162). The median (IQR) of the number of CD4+ T-cells count and VL assays were 2 (2;3) in 2019 and 2 (1;3) in 2020 (p < 0.0001). When focusing on patients followed during both years (N = 1123), we found a significant lower proportion of patients with HIV plasma VL above 400 copies per mL (copies/mL) in 2020 (9% versus 5% patients; p < 0.001).

Co-infections and co-morbidities screening

In 2020, when compared to 2019, we found that significantly less patients followed at our HIV out‐patients clinic benefited from screening for coinfections associated with HIV including notably hepatitis C (p < 0.01) and syphilis (p < 0.01) (). There was also a significant and drastic reduction (p < 0.001) in terms of rectoscopy/colonoscopy for colorectal and anal cancer screening between 2019 and 2020 (51 and 21 exams performed respectively) as well as in terms of screening for hypercholesterolemia (). In contrast, there was a significant increase in the number of patients screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea (p < 0.0001) and for hepatitis B (p < 0.001) (), related to the implementation of a systematic screening program.

Table 6 Coinfections and comorbidities screening

Discussion

This retrospective study highlights the globally negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the medical care of PLWH in Liège (Belgium). Indeed, starting from March 2020, we observed a decrease in new HIV diagnoses, in the follow-up of PLWH (reflected by the number of consultations undertaken by sexual health services, psychologists and specialists in infectious diseases) as well as in several coinfections and comorbidities screening.

During the first wave of the pandemic in Belgium, only face-to-face consultations considered urgent were maintained and the hospital had to cancel the other ones in order to concentrate all the medical and paramedical forces for the battle against COVID-19. In contrast, during the second wave, all the consultations were maintained by the hospital with the aim to ensure a quality medical care for all the patients, SARS-CoV-2 infected or not. We showed that this change in strategy had a profound impact on the follow-up of PLWH with the number of consultations at our out-patient HIV clinic starting from June 2020 reaching similar levels than during the same period in 2019, and even higher in June and November ().Citation11 Very few patients cancelled the consultation themselves indicating that the patients’ hypothetical fear to get infected by SARS-COV-2 in our medical facilities did not or poorly interfere with their follow-up. Moreover, as in other centers, our team developed telehealth options to ensure virtual and distance-based medical care during the pandemic.Citation12–18 This new tool allowed to perform 163 teleconsultations between April and December 2020. Therefore, the conservation of face-to-face consultations with implementation of protective public health measures and the development of a telehealth system seem to represent effective complementary approaches to ensure the continuity of care for PLWH. Furthermore, given the patients overall positive opinion concerning telemedicine during the pandemicCitation19 and beyond,Citation20 this modality is likely to persist afterwards and become full participant of the HIV care. However, several concerns persist about this tool and will represent challenges to overcome before its implementation it as part of the standard care for PLWH. These issues notably include the quality of care that can be provided to patients that cannot be fully clinically examined and the resultant medicolegal risks, the limited accessibility to new technologies for some patients that may lead to health inequalities as well as the risk of disruption with the HIV prevention service that often relies on face-to-face interventions.Citation20,Citation21 These potentials obstacles must be assessed before optimal integration of telemedicine into the routine HIV care.Citation12,Citation22

Immediately after the beginning of the pandemic, we observed a drastic decrease in the number of new HIV diagnoses which remained unusually low until the end of the year. As already suggested in our previous report,Citation9 this decrease is most probably multifactorial. First, HIV screening was complicated by several public health containment measures including the closing of several screening centers and the reduction of public transport as well as by the excessive workload in infectious diseases and virology departments. In addition, first symptoms of HIV infection may have been misinterpreted for COVID-19 symptoms by clinicians but also by the patients, thus urging them to self-isolate and not seek for medical attention. The fear of a HIV diagnosis for people in an already stressful pandemic situation might also have discouraged some psychologically vulnerable patients to get tested. Finally, social distancing might have, at least for a time, decreased the spread of HIV in most-at-risk populations.Citation23,Citation24

Besides being a worldwide health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictive measures have also adversely impacted the mental health and the psychology consultation follow-up of many people, and more particularly PLWH.Citation25 Indeed, several studies reported that PLWH experienced more anxiety and other depression-related symptoms as well as substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic than non-infected patients.Citation6,Citation25–29 Long-term consequences of these worrying issues are still unknow but might be devastating and need to be further explored. Mental health status is an important factor to consider in the management of PLWH since it is a predictor of HIV related health outcomes, including adherence to antiretroviral therapy. The establishment of strategies to preserve the mental wellbeing of our patients is thus a crucial imperative.Citation30 In order to meet this need, it might be helpful to reconsider strategies used during the 2003 outbreak of SARS-CoV including notably the establishment of regional or national multidisciplinary mental health teams, the promotion of virtual visits and communications between patients and their entourage or the implementation of routine screening.Citation31

Early diagnosis and medical care initiation for viral hepatitis and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are considered to be key objectives by the WHO in the European region.Citation32 In a recent survey involving STIs testing sites from 34 European countries,Citation32 95% respondents reported having tested far less than the expected number of patients during the first wave and, although to a lesser degree, between the two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. In line with these results, we observed that less patients followed at our HIV out‐patients clinic benefited from screening for hepatitis C and syphilis in 2020 compared to 2019 but this decrease was smaller than reported in the previous studies. In contrast, screening for hepatitis B, chlamydia and gonorrhea did not decrease and was even more important in 2020. This is due to both by a regional campaign promoting the screening for these STIs set up in 2019 and the incorporation of these screening tests in our standard blood analyses for PLWH. Besides coinfections, we also showed that less PLWH benefited from other comorbidities screening including screening for colorectal and anal cancers as well as hypercholesterolemia. Delays in the medical care of such comorbidities might also have long-term adverse impact on our patients and a close follow-up will thus be needed.

Reassuringly, we observed a diminution of the proportion of patients with HIV plasma VL above 400 copies/ml. However, we also saw a reduction of routine VL assays and blood CD4+ T-cells count analyses making difficult the interpretation of these results. Patients with detectable viral load could have been under tested, leading to underestimation of viral failures. Our study emphasized that despite a significant reduction in term of visits at our out-patient HIV clinic in 2020 compared to 2019 (3 medical visits per patient in 2019 and 2 in 2020; p < 0.0001), there were no short-term impact on the HIV VL. Indeed, we found a significant lower proportion of patients with HIV plasma VL above 400 copies per mL in 2020 (9% versus 5% patients; p < 0.01). Although these data need to be interpreted with caution, these may suggest the possible safely extend scheduled follow-up intervals beyond the standard 3 or 4 months in patients with viral suppression and adoption of new ways of follow-up, including telemedicine. The extension of the follow-up interval should be balanced against possible negative impacts including the impacts on the early detection of virologic failure, screening of other sexually transmitted infections and comorbidities, the psychological support and the physician-patient relationship. These findings highlighted the need for a personalized care for each patient. The selection of patients most susceptible of benefiting from this approach is challenging and requires an individual-based selection.

The main strength of our study is that it was conducted in the epicenter of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe, thereby highlighting the consequences of the pandemic at its worst on the medical care of PLWH. Furthermore, the study period covered two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite these strengths, some limitations of our study should be acknowledged. The first limitation is the nature of our study, which is a monocentric retrospective study thereby allowing us only to study a restricted number of parameters on a limited number of patients. Second, the study focused mainly on the short-term consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV care while long-terms consequences are still unknown.

Conclusions

Our report exhibits the deleterious impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the screening, follow-up and medical care of PLWH in our institution. Although extension of our observations to other regions of the world need to be supported by other studies, these highlight the imperious need to implement new strategies in order to guarantee the continuum of HIV care whatever the circumstances. These strategies might include the establishment of an effective telehealth system as well as an automatized follow-up system for coinfections and comorbidities screening. In order to be fully effective, these measures should be part of a large-scale standardized strategy for the medical care of PLWH.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. M.E., M.M. and G.D. conceived the idea of the study. M.E. and N.L. drafted the manuscript. K.F. collected the data. N.M. performed statistical analyses. M.E., N.L., M.M. and G.D. participated in the scientific revision of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by our institutional Ethics Commitee. Informed consent was not obtained from the patients since the Ethics Commitee also provided a consent waiver for our study.

| List of abbreviations | ||

| ART | = | antiretroviral therapy |

| COVID-19 | = | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| HIV | = | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| IQR | = | interquartile ranges |

| VL | = | viral load |

| PLWH | = | people living with HIV |

| p | = | p-value |

| SARS-CoV-2 | = | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SD | = | standard deviations |

| STIS | = | sexually transmitted infections |

| UNAIDS | = | Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

Code availability

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS Statistical Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R (version 3.6.1) packages were used for the figures.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Majdouline El Moussaoui

Majdouline El Moussaoui is a resident medical doctor who works in the department of Infectious Diseases and General Internal Medicine at the University Hospital of Liège.

Nicolas Lambert

Nicolas Lambert is a resident medical doctor who works in the department of Neurology at the University Hospital of Liège.

Nathalie Maes

Nathalie Maes is a biostatistician who works at the University Hospital of Liège.

Karine Fombellida

Karine Fombellida is a computer scientist and an expert in data management who works at the University Hospital of Liège.

Dolores Vaira

Dolores Vaira is a biologist who works in the AIDS-Reference Laboratory at the University Hospital of Liège.

Michel Moutschen

Michel Moutschen is Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases and director of the GIGA’s Immunology and Infectious Diseases Research Unit at the University of Liège. He is also head of the department of infectious diseases, immunology and general internal medicine as well as head of the AIDS reference centre at the University Hospital of Liège.

Gilles Darcis

Gilles Darcis is a specialist in infectious diseases who works at the University Hospital of Liège and a post-doctoral researcher in the GIGA’s Immunology and Infectious Diseases Research Unit at the University of Liège.

References

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard 2021 [Internet]. https://covid19.who.int. Published 2021. Accessed June 18, 2021.

- World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS - 30 November 2020 [Internet]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids. Published 2020. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- For a Healthy Belgium. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections [Internet]. https://www.healthybelgium.be/en/health-status/communicable-diseases/hiv-and-other-sexually-transmitted-infections. 24 July 2020. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- Jiang H, Zhou Y, Tang W. Maintaining HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(5):e308–e309.

- Cooley SA, Nelson B, Doyle J, Rosenow A, Ances BM. Collateral damage: impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in people living with HIV. J Neurovirol. 2021;27(1):168–170.

- Bhaskaran K, Rentsch CT, MacKenna B, et al. HIV infection and COVID-19 death: a population-based cohort analysis of UK primary care data and linked national death registrations within the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(1):e24–e32.

- Mellor MM, Bast AC, Jones NR, et al. Risk of adverse coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes for people living with HIV. AIDS. 2021;35(4):F1–F10.

- Darcis G, Vaira D, Moutschen M. Impact of coronavirus pandemic and containment measures on HIV diagnosis. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e185.

- Sciensano. COVID-19-Bulletin épidémiologique du 3 novembre 2020 [Internet]. https://covid-19.sciensano.be/sites/default/files/Covid19/COVID-19_Daily%20report_20201103%20-%20FR.pdf. 3 November 2020. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- Sciensano. COVID-19-Bulletin épidémiologique du 1 janvier 2021 [Internet]. https://covid-19.sciensano.be/sites/default/files/Covid19/COVID-19_Daily%20report_20210101%20%20FR.pdf?fbclid=IwAR17I0pLrdFn1JFcg1EWivzGXOTEyJJtvnf9abYDw3pL-6MAx10rsw_R2LA. 1 January 2021. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- Budak JZ, Scott JD, Dhanireddy S, Wood BR. The impact of COVID-19 on HIV care provided via telemedicine-past, present, and future. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2021;22:1–7.

- Mayer KH, Levine K, Grasso C, Multani A, Gonzalez A, Biello K. Rapid migration to telemedicine in a Boston community health center is associated with maintenance of effective engagement in HIV care. Paper presented at: ID Week Conference Virtual; October 21–25, 2020. Abstract 541.

- Quiros-Roldan E, Magro P, Carriero C, et al. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the continuum of care in a cohort of people living with HIV followed in a single center of Northern Italy. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(1):59.

- Tshikung ON, Smit M, Marinosci A, et al. Caring for people living with HIV during the global coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. AIDS. 2021;35(3):355–358.

- Cooper TJ, Woodward BL, Alom S, Harky A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outcomes in HIV/AIDS patients: a systematic review. HIV Med. 2020;21(9):567–577.

- Armstrong WS, Agwu AL, Barrette EP, et al. Innovations in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care delivery during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: policies to strengthen the ending the epidemic initiative-a policy paper of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the HIV Medicine Association. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(1):9–14.

- Ridgway JP, Schmitt J, Friedman E, et al. HIV Care continuum and COVID-19 outcomes among people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic, Chicago, IL. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2770–2772.

- Rogers BG, Coats CS, Adams E, et al. Development of telemedicine infrastructure at an LGBTQ + clinic to support HIV prevention and care in response to COVID-19, Providence, RI. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2743–2747.

- Dandachi D, Dang BN, Lucari B, Teti M, Giordano TP. Exploring the attitude of patients with HIV about using telehealth for HIV care. AIDS Patient Care Stds. 2020;34(4):166–172.

- Wood BR, Young JD, Abdel-Massih RC, et al. Advancing digital health equity: a policy paper of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the HIV Medicine Association. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(6):913–919.

- Eberly LA, Khatana SAM, Nathan AS, et al. Telemedicine outpatient cardiovascular care during the COVID-19 pandemic: bridging or opening the digital divide? Circulation 2020;142(5):510–512.

- Hammoud MA, Maher L, Holt M, et al. Physical distancing due to COVID-19 disrupts sexual behaviors among gay and bisexual men in Australia: implications for trends in HIV and other sexually transmissible infections. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(3):309–315.

- Van Bilsen WPH, Zimmermann HML, Boyd A, et al. Sexual behavior and its determinants during COVID-19 restrictions among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(3):288–296.

- Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):228–229.

- Siewe Fodjo JN, Villela EFM, Van Hees S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the medical follow-up and psychosocial well-being of people living with HIV: a cross-sectional survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(3):257–262.

- Marbaniang I, Sangle S, Nimkar S, et al. The burden of anxiety among people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic in Pune, India. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1598.

- Sun S, Hou J, Chen Y, Lu Y, Brown L, Operario D. Challenges to HIV care and psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic among people living with HIV in China. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2764–2765.

- Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, Rai M, Baral SD. Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2024–2032.

- World Health Organization, regional office for Europe. World AIDS Day video message: delivering good mental health for people living with HIV [Internet]. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/statements/world-aids-day-video-message-delivering-good-mental-health-for-people-living-with-hiv. 1 December 2020. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- HIV Practice. Mental health during coronavirus (COVID-19) [Internet]. https://www.hivpractice.com/mental-health-during-coronavirus/. June 2020. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- Simões D, Stengaard AR, Combs L, Raben D. EuroTEST COVID-19 impact assessment consortium of partners. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on testing services for HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections in the WHO European Region, March to August 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(47):2001943.