Abstract

Background:The aim of this study was to evaluate the frequency, spectrum, in-hospital mortality rate, and factors associated with death in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) presenting with neurological diseases from a middle-income country, as well as estimate its one-year global death rate.

Methods:This prospective observational cohort study was conducted at a Brazilian tertiary health center between January and July 2017. HIV-infected patients above 18 years of age who were admitted due to neurological complaints were consecutively included. A standardized neurological examination and patient and/or medical assistant interviews were performed weekly until the patient’s discharge or death. The diagnostic and therapeutic management of the included cases followed institutional routines.

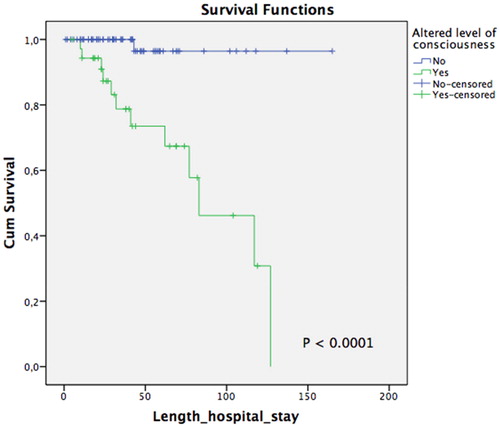

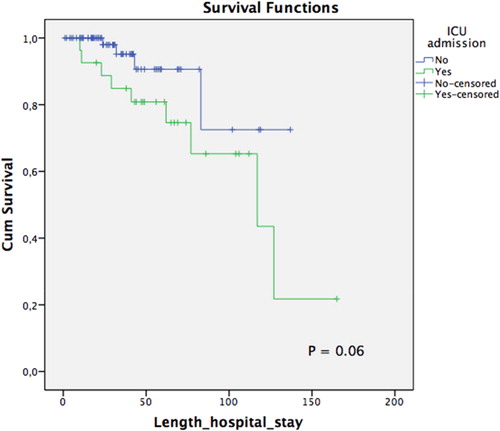

Results:A total of 105 (13.2%) patients were included among the 791 hospitalized PLWHA. The median age was 42.8 [34-51] years, and 61% were men. The median CD4+ lymphocyte cell count was 70 (27-160) cells/mm3, and 90% of patients were experienced in combined antiretroviral therapy. The main diseases were cerebral toxoplasmosis (36%), cryptococcal meningitis (14%), and tuberculous meningitis (8%). Cytomegalovirus causing encephalitis, polyradiculopathy, and/or retinitis was the third most frequent pathogen (12%). Moreover, concomitant neurological infections occurred in 14% of the patients, and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome-related diseases occurred in 6% of them. In-hospital mortality rate was 12%, and multivariate analysis showed that altered level of consciousness (P = 0.04; OR: 22.7, CI 95%: 2.6-195.1) and intensive care unit (ICU) admission (P = 0.014; OR: 6.2, CI 95%: 1.4-26.7) were associated with death. The one-year global mortality rate was 31%.

Conclusion:In this study, opportunistic neurological diseases were predominant. Cytomegalovirus was a frequent etiological agent, and neurological concomitant diseases were common. ICU admission and altered levels of consciousness were associated with death. Although in-hospital mortality was relatively low, the one-year global death rate was higher.

Background

Neurological diseases are commonly diagnosed at the beginning of the HIV-1 epidemic.Citation1 Central nervous system disorders, in particular, occur in approximately 40% of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA),Citation2 wherein opportunistic diseases and primary HIV-1 syndromes become frequent.Citation2,Citation3

Studies have shown that neurological complications account for 5% to 15% of hospitalizations in PLWHA,Citation4 presenting a high global mortality.Citation5–7 Moreover, the spectrum of HIV-related neurological diseases varies according to the following factors: availability of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART), host immune status, epidemiological scenario and/or use of prophylaxis regimens. For example, meningoencephalitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans and Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the major cause of neurological opportunistic diseases in some cities in Africa and Asia, respectively, whereas cerebral toxoplasmosis is the main disease in some cities in Latin America.Citation5,Citation8–11

In relation to the aforementioned factors, people diagnosed with neurological diseases due to HIV usually have a poor prognosis, especially in most low- and middle-income countries,Citation2,Citation11,Citation12 wherein diagnostic tools and therapeutic armamentarium are usually restricted.

Although neuroepidemiology and mortality rates during hospital admissions decreased after cART and prophylaxis regimens,Citation7,Citation13 detailed studies on the post-cART period are scarce in low- and middle-income countries.Citation6 Particularly, in Brazil, the main primary prophylaxis regimens are based on sulphamethoxazole-trimethroprim and azithromycin to avoid diseases caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii, Toxoplasma gondii, and Mycobacterium avium complex, and isoniazid to treat latent tuberculosis infection. Considering that epidemiological patterns vary regionally and information is scarce in places where opportunistic diseases continue to be a challenge, more studies on this topic are needed.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to evaluate the frequency, causes, mortality rate, and factors associated with death in PLWHA presenting with neurological diseases in a referral center in São Paulo, Brazil.

Methods

Settings

This was an observational prospective cohort conducted at the Instituto de Infectologia Emilio Ribas, the main tertiary referral hospital for PLWHA in São Paulo State, Brazil, between January 1, 2017 and July 31, 2017.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: patients who were (I) admitted to hospital wards or intensive care units (ICUs), (II) confirmed to have an HIV infection, (III) above 18 years of age, (iv) presented with neurological symptoms, and (v) had signed the written consent form. The inclusion process occurred consecutively to avoid recruitment bias. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were as follows: patients who were (I) pregnant and (II) presented with neurological manifestations, which were exclusively secondary to prior disease and defined as part of a sequelae.

Variables

Sex, age, CD4+ lymphocyte cell counts and viral loads, HIV medical history (opportunistic diseases and cART use), main and associated neurological symptoms, neurological examination findings, length of hospital stay, hospitalization and one year after discharge outcomes, and brain computer tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were recorded. Neurological diseases and etiological diagnoses during hospitalization were also documented.

Definitions and outcomes

HIV infection diagnosis followed the Brazilian Ministry of Health guidelines. Regular cART was considered, if the patient reported daily use of medications within the last seven days prior to hospital admission.

Neurological diagnosis according to clinical presentation and etiology was classified as either confirmed or probable based on clinical, radiological, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings (including basic characteristics, cultures, antigen test, and molecular techniques), and histopathological information (Supplementary Material).

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) was defined in patients with the following features: (I) worsening infection or inflammatory disease symptoms; (II) symptoms not explained by newly acquired infection or disease, or the usual course of a previously acquired disease; and (III) a decrease in plasma HIV RNA level by >1log10 copies/ml.Citation14 Moreover, IRIS was classified as either unmasking or paradoxical. Unmasking IRIS was defined as a flare-up of an undiagnosed infection, whereas paradoxical IRIS was defined as worsening of a known previous infection under treatment.

Hospitalization outcomes were evaluated and classified as follows: (I) discharge with treatment success according to clinical, laboratory, and neurological imaging; or (II) death. Additionally, one year after discharge outcomes were also evaluated and classified as either survival or death.

Procedures

Researchers in this study were all infectious disease specialists and were trained by a team of neurologists to minimize neurological examination heterogeneity. Between 24 and 48 hours after hospital admission, patients were included in the study. Standardized forms were then used to record demographic, clinical, laboratory, and radiological details. Following inclusion, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), cultures, and serology/antigen results from blood and CSF were analyzed, and CT, MRI, and single-photon emission computed tomography were also available for patient diagnosis if needed. Infectious disease specialists, according to routine institutional protocols, were responsible for the diagnosis and treatment decisions, and specialists in neuroradiology, neurology, and neurosurgery were also present if needed.

Previous and post-discharge CD4+ lymphocyte cell counts, HIV viral loads, and cART treatment regimens were obtained from the following national surveillance systems: “Sistema de Controle de Exames Laboratoriais da Rede Nacional de Contagem de Linfócitos CD4+/CD8+ e Carga Viral do HIV (SISCEL)” and “Sistema de Controle Logístico de Medicamentos (SICLOM).”

From admission, our research team performed a weekly follow-up (monitoring medical records and/or standardized neurological examination; interviewing patients and/or medical assistants) until patient death or discharge during the hospital stay. Furthermore, the one-year global death rate was estimated using information from our outpatient clinic, emergency room data, and national surveillance systems (i.e., SISCEL and SICLOM). Patients lost to follow-up were classified as dead in the one-year survival analysis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median values and interquartile range (IQR) and were analyzed using the t-test or Mann Whitney test. On the other hand, categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and proportions, and they were analyzed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. In addition, prognostic factors were analyzed according to Kaplan-Meyer, Mantel-Cox log-rank, and proportional Cox proportional-hazards models. All univariate model variables meeting a cut-off of P ≤ 0.1 were included in the multivariable model. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and SPSS (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

General characteristics

During the study period, a total of 1,032 patients were admitted at our institution. Of these, 791 were admitted due to HIV/AIDS, and 120 (15%) were eligible for our study. However, 15 patients were transferred to other centers before the end of treatment at our institution and/or refused to participate in our study. Thus, 105 (13.2%) patients were included and followed up until discharge or in-hospital death.

Sixty-five of the 105 (61%) patients were male, and 95 of them (90%) underwent cART. Median (IQR) age and CD4+ lymphocyte cell count were 42.8 years (34–51) and 70 cells/mm3 (27–160), respectively. The median (IQR) length of stay was 36 days (range: 20–58 days). The main baseline characteristics of the included patients are detailed in .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of people living with HIV/AIDS admitted due to neurological disorders at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas, São Paulo, Brazil.

Neurological manifestations and syndromes

The main neurological complaints of the participants were headache (31%, n = 32), hemiparesis (18%, n = 19), mental confusion (16%, n = 17), and seizures (11.5%, n = 12). A total of 84 patients presented with more than one neurological complaint (80%), and the median (IQR) neurological complaints per patient was noted to be 3.3.Citation2–4

Diagnosis of disease and etiologies

All patients included were classified according to disease and etiology. The spectrum of neurological diseases is listed in . The main neurological diseases were cerebral toxoplasmosis (36%, n = 44), cryptococcal meningoencephalitis (14.8%, n = 18), and tuberculous meningoencephalitis (8.2%, n = 10). Other diseases included neurosyphilis (7.4%, n = 9), Cytomegalovirus (CMV) encephalitis (4.1%, n = 5), CMV polyradiculopathy (4.1%, n = 5), progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL), and CMV retinitis (3.3%, n = 4).

Table 2. Neurological diseases diagnosed during hospitalization from patients living with HIV/AIDS admitted due to neurological disorders at Emilio Ribas Institute of Infectious Disease.

The main etiological agents were Toxoplasma gondii (36%, n = 44), Cryptococcus neoformans (14.8%, n = 18), CMV (11.5%, n = 14), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (9%; n = 11). The spectrum of the etiological diagnoses is shown in .

Table 3. Etiological diagnosis from patients living with HIV/AIDS admitted due to neurological complaints at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas, São Paulo, Brazil.

Regarding the presence of concomitant neurological diagnoses, more than one neurological disease was diagnosed in 15% (n = 16) patients, wherein concomitant neurological infections were found in 14% (n = 15) of the patients. The identification of a second neurological diagnosis after admission was found in 87% (n = 13) of them, while undergoing treatment for the first disease. Additionally, neurological co-infections associated with cerebral toxoplasmosis occurred in 20% (n = 9) of the patients, and CMV accounted for 55% (n = 5) of the second disease. Furthermore, the mortality rates in patients with or without concomitant neurological disease were 20% (n = 3) and 11% (n = 10), respectively (P = 0.3).

On admission, IRIS was observed in 5.7% (n = 6) of patients. Specifically, paradoxical IRIS occurred in 2 patients due to cryptococcal meningitis and PML, whereas unmasked IRIS occurred in 4 patients due to cryptococcal meningitis (n = 2), CMV retinitis, and neurosyphilis.

In-hospital outcomes and prognosis factors

In-hospital death rate was noted to be 12% (n = 13), with the main cause of death being pulmonary sepsis (66%) (health-care-associated pneumonia). Descriptive analyses between the death and survival groups are further shown in . In univariate analysis, prognostic factors related to death included a CD4-T lymphocyte count <50 cells/mm3 (P = 0.016; OR: 4.6, CI 95%: 1.3-16), altered level of consciousness (P < 0.001; OR: 34, CI 95%: 4 to 275), and ICU admission (P < 0.001; OR: 9.2, CI 95%: 2.5-33.4) (). Moreover, multivariate analysis demonstrated statistical significance in altered level of consciousness (P = 0.04; OR: 22.7, CI 95%: 2.6-195.1) and ICU admission (P = 0.014; OR: 6.2, CI 95%: 1.4–26.7) (). However, in survival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier curve, only altered level of consciousness remained a significant variable associated with earlier death (log rank test, P < 0.0001) ( and ).

Figure 1. Survival analysis in relation to altered level of consciousness in patients living with HIV/AIDS admitted for neurological complaints at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas between January and August 2017.

Figure 2. Survival analysis in relation to ICU admission in patients living with HIV/AIDS admitted for neurological complaints at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas between January and August 2017.

Table 4. Descriptive analysis of prognostic factors associated with death in people living with HIV/AIDS admitted due to neurological diseases at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas, São Paulo, Brazil.

Table 5. Univariate analysis of prognostic factors associated with death in people living with HIV/AIDS admitted due to neurological diseases at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas, São Paulo, Brazil.

Table 6. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors associated with death in people living with HIV/AIDS admitted due to neurological diseases at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas, São Paulo, Brazil.

Outcomes after one year

In addition to the 13 in-hospital deaths, 9 patients were lost to follow-up in the early post-discharge period. Thus, only 83 patients (79%) were followed up for one year. Among these patients, 13% (n = 11) died during hospital readmission. Overall, the one-year global mortality rate was estimated to be 31% (n = 33; in-hospital, n = 13; after discharge, n = 20).

Discussion

This was a prospective observational cohort of PLWHA admitted due to neurological complaints in a referral center of São Paulo, Brazil. The included patients had at least one neurological diagnosis, and all of them received in-hospital treatment. Additionally, in-hospital and one-year postoperative mortality rates were 12% and 31%, respectively. Furthermore, ICU admission and altered levels of consciousness were associated with in-hospital mortality on multivariate analysis, but only altered levels of consciousness were related to in-hospital deaths in survival analysis.

The prevalence of neurological conditions in PLWHA varies according to immune status, cART usage, and geography. Previous studies from low- and middle-income countries, usually those with restricted access to cART (i.e., Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia), have reported cryptococcal meningitis as a major neurological cause of hospitalization in PLWHA,Citation5,Citation10,Citation12 possibly due to the high prevalence of C. neoforman in these regions.Citation15–17 In contrast, high-income regions did not report this distribution. Prior to the cART era, studies from Western Europe and the United States reported cerebral toxoplasmosis, PCNSL, and PML as the main diagnoses in PLWHA.Citation18 However, with the implementation of cART, studies have shown an impressive reduction in the incidences of these neurological opportunistic diseases.Citation19,Citation20 Similarly, universal and free access to cART in Brazil has resulted in a dramatic reduction in opportunistic infections.Citation21 Despite this, the impact of cART in Brazil seemed to be more attenuated than that of high-income countries, at least in part, probably due to the presence of high rates of infections in the general population (i.e., toxoplasmosis or tuberculosis) or due to increased environmental exposure (i.e., cryptococcosis) and consequently more cases in PLWHA.Citation22,Citation23 Moreover, opportunistic neurological diseases in immigrants may constitute a relevant proportion of patients in high-income countries.Citation24 Our results were consistent to the findings of cohort and neuropathological studies from Latin America, demonstrating cerebral toxoplasmosis and cryptococcal meningitis as the main neurological diseases in PLWHA.Citation25,Citation26 Following the Brazilian HIV/AIDS guidelines, primary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (e.g., CD4+ lymphocyte cell count <200 cell/mm3), cerebral toxoplasmosis (e.g., CD4+ lymphocyte cell count <100 cell/mm3), and disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease (e.g., CD4+ lymphocyte cell count <50 cell/mm3) should have been prescribed to the majority of our patients. However, even though sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim and/or azithromycin were prescribed to half of the patients in this cohort, 96% of them were considered to be irregularly used at hospital admission. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder has been reported as a frequent problem in a previous study carried out at our institution, which evaluated outpatients.Citation27 HIV-associated dementia was a rare cause of hospitalization in the preset study, but formal neuropsychological assessment was not routinely performed as part of our protocol.

Although information on concomitant neurological diseases are scarce in the literature, these conditions were early noticed following the onset of the AIDS epidemic.Citation28,Citation29 It was found that concurrent neurological diagnosis epidemiology varied according to the study design and setting, but most neuropathological post-mortem studies have observed concomitant disorders in between 5% and 20% of patients.Citation27,Citation30–32 In addition, it is difficult to compare pathological pre- and post-cART studies regarding concomitant disorders, since there is large heterogeneity in the diagnostic methods applied, mainly with regard to viral infection diagnosis. For example, pre-cART studies, which did not use in situ hybridization, were found in 7% to 10% of CMV infection cases,Citation30,Citation31 whereas post-cART studies using molecular techniques found rates as high as 20% of CMV infection cases.Citation32 This suggests that the proportion of some diseases may change as a function of diagnostic tool availability. In the late cART era, concomitant neurological infections have been evaluated in a few clinical studies. Particularly, two studies, including multiplex PCR, found 16% to 26% of concomitant neurological infections in symptomatic patients.Citation6,Citation33 Additionally, when using broader inclusion criteria for multiplex PCR in CSF samples from PLWHA, pathogens without clear clinical significance might be found, such as Epstein-Barr virus.Citation34 The significant proportion of concomitant neurological diseases observed in the present study was consistent with these studies, which was probably due to the intensive diagnosis routine and the availability of a reasonable infrastructure, suggesting that the prevalence of concomitant neurological infections was likely influenced by previous pathogen exposure. Thus, in geographic regions with higher exposure to T. gondii, M. tuberculosis, and C. neoformans, such as in Latin America, it is more probable to find a higher coinfection prevalence as compared to other epidemiological settings.

Most available studies have reported that PLWHA presenting with neurological diseases were associated with a high mortality. In fact, global mortality is frequently estimated to be above 25% to 30% regardless of region, even in the post-cART period.Citation6,Citation11,Citation25,Citation33 In our study, the in-hospital death rate (12%) was similar to other data from low- and middle-income tertiary centers, demonstrating a >80% survival rate.Citation5,Citation35 Despite the low in-hospital mortality rate, however, we observed a high (31%) one-year global mortality rate. Currently, PLWHA with opportunistic diseases represents a subgroup of patients with late HIV diagnosis or with barriers to regular prophylaxis, cART, and adequate outpatient follow-up. In particular, some of these patients remain in vulnerable conditions (i.e., socio-economic problems, addiction, mental disorders) following their first hospitalization and discharge to home. As a result, most of them would continue to be immunosuppressed, explaining, at least in part, the high late mortality rate in this population.

Prognosis factors in PLWHA admitted to hospital due to neurological disorders vary according to region and period. Older age, prior AIDS diagnosis, and PML have been associated with shorter survival in Europe.Citation13 On the other hand, altered levels of consciousness, treatment according to each etiological agent, and concomitant neurological pathogens were related to a poor prognosis in Asia.Citation33 Similarly, a previous study in Brazil reported a poor prognosis in patients with concomitant neurological diseases.Citation36 In our current study, our results identified ICU admission and altered levels of consciousness as factors associated with in-hospital mortality in the multivariate analysis; however, concomitant neurological diseases were not associated with this outcome, despite having double the mortality of patients with a single neurological disease. The timely diagnosis and treatment of a subset of patients with concomitant neurological diseases can, at least in part, explain these findings. Furthermore, the lack of association between concomitant neurological diseases and death can be the result of the relatively low number of patients included in the present study. Interestingly, in-hospital death was only related to altered levels of consciousness in the survival analysis, which is an important finding since mild abnormalities in the Glasgow Coma Scale are commonly underestimated in clinical practice. Therefore, patients with altered levels of consciousness should receive a multidisciplinary assessment in order to prevent bronchoaspiration and hospital-acquired pneumonia, which are the conditions most associated with death in this cohort.

This study had certain limitations. First, only 105 patients were included, and larger cohorts may reflect more accurate results. However, the study’s prospective design and strict clinical evaluation affirms the confidence of our results. Second, this study was conducted in a single tertiary healthcare center in a middle-income country, and thus the results must be carefully evaluated before being extrapolated to other contexts. Nevertheless, patient management for all participants followed the clinical practice of the institution in “real-world conditions”. Finally, the frequency and functional impact of neurological morbidities and sequelae were not considered in the design of this study. Future research is needed to assess this impact in the late cART era in Latin America.

Conclusion

Classical opportunistic neurological diseases remain an important concern in the neuroepidemiology of PLWHA. CMV is a common etiological agent and concomitant neurological infections are frequent. ICU admission and altered levels of consciousness were associated with in-hospital death on multivariate analysis. The in-hospital mortality rate was found to be relatively low; however, the one-year global mortality rate was higher. These real-world results indicate that most PLWHA with neurological diseases presented good in-hospital outcomes in a referral center from a middle-income country. However, there is a need to reduce the late mortality rate here reported. For this, it is key to implementation and optimize individual and public health strategies, aiming at continuous care and adherence to cART in this particularly vulnerable group of patients.

Abbreviations

| cART | = | combined antiretroviral therapy |

| CMV | = | cytomegalovirus |

| CSF | = | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | = | computed tomography |

| ICU | = | intensive care unit |

| IRIS | = | Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome |

| MRI | = | magnetic resonance imaging |

| PCR | = | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PLWHA | = | people living with HIV and AIDS |

| SISCEL | = | Sistema de Controle de Exames Laboratoriais da Rede Nacional de Contagem de Linfócitos CD4+/CD8+ e Carga Viral do HIV |

| SICLOM | = | Sistema de Controle Logístico de Medicamentos. |

| SPECT | = | single photon emission computed tomography |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- . CDC. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 30, no. 25, July 3, 1981 [Internet]. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/1265

- Levy RM, Bredesen DE, Rosenblum ML. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(4):475–495.

- Jordan BD, Navia BA, Petito C, Cho ES, Price RW. Neurological syndromes complicating AIDS. Front RadiatTherOncol. 1985;19:82–87.

- Ford N, Shubber Z, Meintjes G, et al. Causes of hospital admission among people living with HIV worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(10):e438-444–e444.

- Dai L, Mahajan SD, Guo C, et al. Spectrum of central nervous system disorders in hospitalized HIV/AIDS patients (2009-2011) at a major HIV/AIDS referral center in Beijing, China. J Neurol Sci. 2014;342(1–2):88–92.

- Siddiqi OK, Ghebremichael M, Dang X, et al. Molecular diagnosis of central nervous system opportunistic infections in HIV-infected Zambian adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(12):1771–1777.

- Matinella A, Lanzafame M, Bonometti MA, et al. Neurological complications of HIV infection in pre-HAART and HAART era: a retrospective study. J Neurol. 2015;262(5):1317–1327.

- Sharma SR, Hussain M, Habung H. Neurological manifestations of HIV-AIDS at a tertiary care institute in North Eastern India. Neurol India 2017;65(1):64–68.

- Asselman V, Thienemann F, Pepper DJ, et al. Central nervous system disorders after starting antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2010;24(18):2871–2876.

- Rajasingham R, Rhein J, Klammer K, et al. Epidemiology of meningitis in an HIV-infected Ugandan cohort. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(2):274–279.

- Ramírez-Crescencio MA, Velásquez-Pérez L, Ramírez-Crescencio MA, Velásquez-Pérez L. Epidemiology and trend of neurological diseases associated to HIV/AIDS. Experience of Mexican patients 1995-2009. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(8):1322–1325.

- Trachtenberg JD, Kambugu AD, McKellar M, et al. The medical management of central nervous system infections in Uganda and the potential impact of an algorithm-based approach to improve outcomes. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11(6):524–530.

- Garvey L, Winston A, Walsh J, UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (CHIC) Study Steering Committee, et al. HIV-associated central nervous system diseases in the recent combination antiretroviral therapy era. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(3):527–534.

- Robertson J, Meier M, Wall J, Ying J, Fichtenbaum CJ. Immune Reconstitution Syndrome in HIV: Validating a case definition and identifying clinical predictors in persons initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(11):1639–1646.

- Magambo KA, Kalluvya SE, Kapoor SW, et al. Utility of urine and serum lateral flow assays to determine the prevalence and predictors of cryptococcalantigenemia in HIV-positive outpatients beginning antiretroviral therapy in Mwanza. Tanzania. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):19040.

- Letang E, Müller MC, Ntamatungiro AJ, et al. Cryptococcal antigenemia in immunocompromised human immunodeficiency virus patients in rural Tanzania: A preventable cause of early mortality. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2(2):ofv046.

- Micol R, Lortholary O, Sar B, et al. Prevalence, determinants of positivity, and clinical utility of cryptococcalantigenemia in Cambodian HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(5):555–559.

- Antinori A, Ammassari A, De Luca A, et al. Diagnosis of AIDS-related focal brain lesions: a decision-making analysis based on clinical and neuroradiologic characteristics combined with polymerase chain reaction assays in CSF. Neurology 1997;48(3):687–694.

- d'Arminio Monforte A, Cinque P, Mocroft A, EuroSIDA Study Group, et al. Changing incidence of central nervous system diseases in the EuroSIDA Cohort. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):320–328.

- Sacktor N, Lyles RH, Skolasky R, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, et al. HIV-associated neurologic disease incidence changes: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, 1990-1998. Neurology 2001;56(2):257–260.

- Coelho L, Cardoso SW, Amancio RT, et al. Trends in AIDS-defining opportunistic illnesses incidence over 25 years in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98666.

- Wang ZD, Wang SC, Liu HH, et al. Prevalence and burden of Toxoplasma gondii infection in HIV-infected people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(4):e177–188–e188. [Internet].

- Vidal JE. HIV-related cerebral toxoplasmosis revisited: current concepts and controversies of an old disease. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2019;18:1–20.

- Husstedt IW, Braicks O, Reichelt D, Oelker-Grueneberg U, Evers S. Treatment of immigrants and residents suffering from neuro-AIDS on a neurological intensive care unit: epidemiology and predictors of outcome. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113(4):391–395.

- Oliveira JF, Greco DB, Oliveira GC, Christo PP, Guimarães MD, Oliveira RC. Neurological disease in HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment: a Brazilian experience. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39(2):146–151.

- Silva AC, Rodrigues BS, Micheletti AM, et al. Neuropathology of AIDS: An autopsy review of 284 cases from Brazil comparing the findings pre- and post-HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy) and pre- and postmortem correlation. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:186850.

- Gascón MRP, Vidal JE, Mazzaro YM, et al. Neuropsychological assessment of 412 HIV-infected individuals in Saõ Paulo. Brazil. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(1):1–8.

- Tucker T, Dix RD, Katzen C, Davis RL, Schmidley JW. Cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus ascending myelitis in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1985;18(1):74–79.

- Laskin OL, Stahl-Bayliss CM, Morgello S. Concomitant herpes simplex virus type 1 and cytomegalovirus ventriculoencephalitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1987;44(8):843–847.

- Lang W, Miklossy J, Deruaz JP, et al. Neuropathology of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS): a report of 135 consecutive autopsy cases from Switzerland. Acta Neuropathol. 1989;77(4):379–390.

- Chimelli L, Rosemberg S, Hahn MD, Lopes MB, Netto MB. Pathology of the central nervous system in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV): a report of 252 autopsy cases from Brazil. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1992;18(5):478–488.

- Jellinger KA, Setinek U, Drlicek M, Böhm G, Steurer A, Lintner F. Neuropathology and general autopsy findings in AIDS during the last 15 years. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100(2):213–220.

- Yang R, Zhang H, Xiong Y, et al. Molecular diagnosis of central nervous system opportunistic infections and mortality in HIV-infected adults in Central China. AIDS Res Ther. 2017;14:24.

- Rhein J, Bahr NC, Hemmert AC, ASTRO-CM Team, et al. Diagnostic performance of a multiplex PCR assay for meningitis in an HIV-infected population in Uganda. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;84(3):268–273.

- Jowi JO, Mativo PM, Musoke SS. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of hospitalised patients with neurological manifestations of HIV/AIDS at the Nairobi hospital. East Afr Med J. 2007;84(2):67–76.

- Vidal JE, Penalva de Oliveira AC, Pellegrino D, et al. Complicacões neurológicas em pacientes infectados pelo HIV e fatores associados a óbito na era cART: estudo observacional prospectivo no Instituto de Infectologia EmilioRibas. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15(Suppl 1):23.