Abstract

Background: Different antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) may have differing effects on central nervous system (CNS) function. We assessed CNS pharmacodynamic effects of switching integrase inhibitors in people-with-HIV (PWH).

Methods: PWH on tenofovir-DF/emtricitabine plus raltegravir 400 mg twice daily with suppressed plasma HIV RNA and without overt neuropsychiatric symptoms were randomly allocated on a 1:2 basis to remain on raltegravir or switch to dolutegravir 50 mg once daily for 120 days. Pharmacodynamic parameters assessed included cognitive function (z-score of 7 domains), patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs; PHQ-9 and Beck’s depression questionnaires), cerebral metabolite ratios measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (H1-MRS) and plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) HIV RNA. Pharmacokinetic parameters were also assessed in plasma and CSF. Changes and factors associated with changes in pharmacodynamics parameters were assessed.

Results:In 20 subjects (19 male, 14 white ethnicity, median age 43 years (IQR: 11.5) and CD4 + count 717 (SD: 298) cells/µL), over 120 days there were no statistically significant changes in cognitive function [mean z-score difference (95%CI) −0.004 (−0.38/0.37); p = 0.98], PROMs [PHQ-9 median score change: 0 in control arm, −0.5 switch arm (p = 0.57); Beck’s depression questionnaire: −1.5 control arm, −1.0 switch arm (p = 0.38)], nor cerebral metabolite ratios between study arms. CSF HIV RNA was <5 copies/mL at baseline and day 120 in all subjects. Geometric mean pre-dose CSF dolutegravir concentration was 7.6 ng/mL (95% CI: 5.2–11.1).

Conclusions:Switching integrase inhibitor in virologically suppressed PWH without overt neuropsychiatric symptoms resulted in no significant changes in an extensive panel of CNS pharmacodynamics parameters.

Introduction

Modern effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) suppresses plasma viremia and allows restoration of immune system function in persons with HIV (PWH). Consequently, in ART treated PWH, AIDS defining illnesses are now rare and life expectancy approaches that of the general population.Citation1 However, when compared to the general population, the prevalence of non-infectious co-morbidities are reported to be greater and quality of life is described to be poorer in PWH.Citation2

Central nervous system (CNS) disorders are one group of conditions which remain highly prevalent in otherwise effectively treated PWH. This includes neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety and cognitive impairment.Citation3,Citation4 Evidence suggests that different antiretroviral agents and combinations may have differing effects on cerebral function and neuropsychiatric symptomatology.Citation5–7 The non-nucleoside-reverse-transcriptase-inhibitor efavirenz has well documented neuropsychiatric side effectsCitation8 and in more recent years, a host of CNS side effects (such as sleep disorders, dizziness, depression or anxiety) have been reportedly associated with the use of the HIV-integrase strand-transfer-inhibitors.Citation9–13 These CNS side effects have been more frequently observed in certain populations, such as older patients, female individuals or in PWH with underlying depression or anxiety disorders.Citation14,Citation15

Our aim here was to assess the pharmacodynamic effects on the CNS of two different integrase-inhibitor containing ART regimens. To assess this, we employed a comprehensive battery including cognitive assessments, patient reported outcome measures (PROMs), measurement of CNS metabolites using in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) imaging and measurement of several cerebrospinal fluid parameters including HIV-1 RNA, soluble biomarkers and infectivity markers. Pharmacokinetic parameters were also assessed and included integrase-inhibitor drug exposure in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid.

Methods

Subject selection and study design

This prospective, randomized, single center, proof of concept study was conducted at St. Mary’s Hospital (Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK) from July 2015 to August 2016. PWH on ART comprising of raltegravir 400 mg twice daily plus tenofovir/emtricitabine 245/200 mg (Truvada™) with an undetectable plasma HIV-1 RNA for at least 3 months with no neurological or cognitive complaints were eligible. Exclusion criteria included previous exposure to dolutegravir, significant neurological disease, current history of major depression or psychosis, recent head injury (prior 3 months) and current alcohol abuse or drug dependence.

Individuals were randomized on a 1:2 basis to either remain on raltegravir (control arm) or to switch integrase inhibitor from raltegravir to dolutegravir 50 mg once daily (switch arm). At baseline and after 120 days, all subjects underwent assessment of cerebral function parameters.

Ethical considerations

Local human ethics committee approval was granted prior to recruiting participants by the National Research Ethics Service Committee London-Central, UK (REC number 14/LO/1864). All participants were required to sign an informed consent before undergoing any screening procedures. The study was registered on the European Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT number 2014-003710-84).

Cerebral function parameters

Cognitive testing and patient reported outcome measures

Cognitive testing and PROMs were undertaken at baseline, day 60 and day 120. Cognitive testing comprised of a computerized battery (CogState™ Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) which has been validated for cognitive testing in several disease areas including HIV.Citation16 The battery undertaken in this study took approximately 30 min to complete and comprised of 7 specific tests covering several cognitive domains (attention, psychomotor function, visual and working memory and associate learning). PROMs were Lawton’s instrumental activities of daily living scale,Citation17 Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)Citation18 and Beck’s depression questionnaires.Citation19

Neuroimaging

Cerebral proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) was performed on a Siemens MAGNETOMTM Verio 3 Tesla scanner (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) at baseline and day 120 with methods previously described in detail.Citation20

Post-processing of MRS were analyzed using the time-domain fitting algorithm Totally Automatic Robust Quantitation in NMR (TARQUIN™) (version 4.3.5).Citation21 Metabolites identified included N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), Choline (Cho), myo-inositol (mI), and creatine (Cr) with all metabolites expressed as ratios to Cr.

Cerebrospinal fluid parameters

Cerebrospinal fluid examinations were undertaken at baseline and day 120 prior to administration of ART. Analyses included ultrasensitive HIV-1 RNA, antiretroviral drug concentration (plasma concentration also measured), tryptophan/phenylalanine metabolites, neopterin, and infectivity assays.

Cerebrospinal fluid HIV-1 RNA was measured using a high sensitivity in-house assay with a detection limit of 5 RNA copies/mL.Citation22 Concentrations of raltegravir and dolutegravir were analyzed by high-performance-liquid-chromatography (HPLC) tandem mass spectrometry.Citation23 The lower limits of quantification (LLQ) in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid were, respectively, 5 and 1.95 ng/mL for raltegravir alongside 10 and 0.75 ng/mL for dolutegravir.

Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of tryptophan, kynurenine, phenylalanine, tyrosine and neopterin were measured using previously described methodologies.Citation24 The kynurenine/tryptophan and phenylalanine/tyrosine ratios were calculated as indexes of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO-1) and phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) activity, respectively.

Cerebrospinal fluid infectivity assays were undertaken using cell cultures as previously described in detail.Citation25

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). As a proof of concept study, no specific power calculations were undertaken.

Cognitive results were analyzed in accordance with CogState™ recommendations. Z-standardized scores for each participant in each cognitive task were estimated using task-specific means and standard deviations at baseline. Data are presented as global cognitive scores, calculated as a composite of all cognitive tasks. Where necessary, change of sign was undertaken in order for the scoring of all tasks to be unidirectional (the higher the score, the better the performance).

Means and standard deviation of cerebral metabolite ratios were calculated. Absolute changes in cerebral metabolite ratios between baseline and follow-up were evaluated using a paired sample t-test.

Geometric means (GM) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for cerebrospinal fluid and plasma concentrations of raltegravir and dolutegravir. The CIs were first determined using logarithms of the individual GM values and then the calculated values were expressed as linear values. A coefficient of variation (CV, [(standard deviation/mean) × 100]) was used to express inter-patient variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters.

Comparisons between the study arms for cerebral function parameters were undertaken using appropriate statistical methods which included paired and independent t-tests, chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests and Mann–Whitney U-test. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to investigate associations between changes in PROMs and cerebral metabolite ratios

For the tryptophan pathway metabolites, paired-samples t-tests were undertaken to assess changes in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid concentrations over the study period for each arm independently. Pearson r correlations were used to determine associations between cerebral parameters and global cognitive scores for all subjects at baseline. Mixed models were constructed to investigate the relationship between changes in metabolite concentrations in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid with the global cognitive score for subjects in the dolutegravir arm (switch arm) only. The models fixed effects were global cognitive score (dependent variable) with the biomarker concentrations the independent variable. The alpha value was set at 0.05 for each analysis performed and not corrected for multiplicity.

Results

Subject characteristics

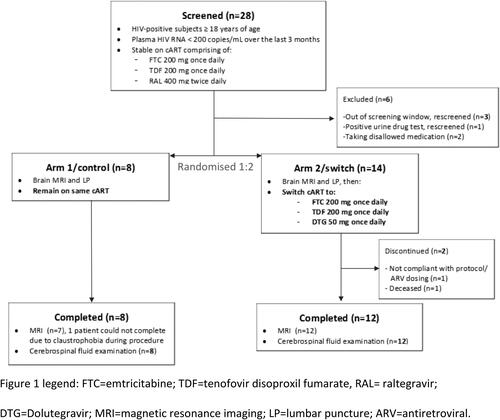

Of 28 participants screened, 22 were randomized and 20 completed study procedures (8 in the control arm and 12 in the switch arm, see ). Baseline characteristics are shown in . Study drugs were generally well-tolerated with all patients reporting over 95% adherence to therapy. No safety or laboratory concerns related to study drugs were observed. One patient in the switch arm died during the study follow-up due to complications arising from a previously undiagnosed metastatic malignancy. At day 120, plasma HIV-1 RNA was <20 copies/mL in all subjects.

Figure 1. Consort diagram of participant flow. ARV, antiretroviral; DTG, dolutegravir; FTC, emtricitabine; LP, lumbar puncture; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RAL, raltegravir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Table 1. Participant demographics and clinical characteristics.

Cognitive results and patient reported outcome measures

Baseline cognitive performance and changes over the study period as shown in . No statistically significant differences between the study groups were observed in changes in global cognitive score or in individual cognitive domains (all p-values >0.1). No differences in changes in depression questionnaires between the study arms were observed at day 120 from baseline (p = 0.57 for PHQ-9 and p = 0.38 for Beck’s, see ). The result of the Lawton’s instrumental activities of daily living scale questionnaire was 8 for all patients at all time-points.

Table 2. Changes in cognitive function and patient reported outcome measures by study arm at day 120.

Neuroimaging

Cerebral metabolite ratio results are shown in . No statistically significant changes in cerebral metabolite ratio were observed over the study period between the two study treatment groups and no significant associations were observed between the PROMs and changes in cerebral metabolite ratios (p > 0.2 for all associations).

Table 3. Changes in cerebral metabolites over 120 days and correlations with depression questionnaires.

Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma parameters

In all individuals, cerebrospinal fluid HIV-1 RNA was undetectable (<5 copies/mL) at both baseline and day 120. Cerebrospinal fluid GM concentrations of raltegravir for the control arm at baseline (n = 8), control arm at day 120 (n = 8) and switch arm at baseline (n = 12) were 16.2 ng/mL (95% CI: 9.4–27.9), 15.0 ng/mL (95% CI: 8.6–26.3) and 14.8 ng/mL (95% CI: 8.2–26.8), respectively. Cerebrospinal fluid GM concentrations of dolutegravir for the switch arm at day 120 (n = 12) was 7.6 ng/mL (95% CI: 5.2–11.1). See for full pharmacokinetic results.

Table 4. Pharmacokinetic parameters of integrase inhibitors in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid over the study period.

Concentrations of tryptophan, kynurenine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and neopterin, and the tryptophan/kynurenine and phenylalanine/tyrosine ratios, are shown in . In the switch arm, mean plasma concentration of tryptophan increased significantly from baseline to day 120 (mean increase, 4.84 µmol/L; p = 0.038; 95% CI, 0.32–9.37). No other statistically significant changes in concentrations of the other measured plasma biomarkers were observed in either arm. Statistically significant differences in plasma tryptophan (p = 0.011) and cerebrospinal fluid neopterin concentrations (p = 0.049) were observed between arms at day 120.

Table 5. Tryptophan metabolism parameters in plasma and CSF over study period.

All cerebrospinal fluid samples displayed dose–response curves allowing quantification of antiretroviral activity on infectivity assays. At a 1:4 dilution, all cerebrospinal fluid samples from both study arms presented near-maximal inhibition at both time points. Infectivity model half maximal inhibitory IMIC50 expressed as CNS Anti-Retroviral scores (−Log2IMIC50) of cerebrospinal fluid samples did not show statistically significant changes between baseline and day 120 for both study groups (p = 0.36 for control group and p = 0.27 for switch group).

Associations with tryptophan metabolites

No statistically significant associations were observed between plasma kynurenine or tyrosine pathway metabolites and global cognitive scores at baseline (all p values >0.1). Cerebrospinal fluid phenylalanine concentrations positively correlated with baseline global cognitive scores (r = 0.49, unadjusted p = 0.024), as did cerebrospinal fluid phenylalanine/tyrosine ratios (r = 0.57, unadjusted p = 0.007).

In the mixed model analysis of the switch arm (dolutegravir), plasma kynurenine/tryptophan ratio concentrations correlated with changes in global cognitive scores, such that for every 1 µmol/L increase observed in kynurenine/tryptophan ratio, a 0.019-point decrease was observed in the global cognitive scores (unadjusted p = 0.021), indicating poorer cognitive performance as the kynurenine/tryptophan ratio increases. No other statistically significant associations were observed for the other biomarkers tested in either plasma or cerebrospinal fluid.

Discussion

In this randomized, prospective, proof of concept study, comparing switching integrase inhibitor-based ART in PWH without overt neuropsychiatric symptoms, we observed no differences in cognitive function or other cerebral function parameters over a 120-day period. Strengths of our study include the randomized approach to the study design and the detailed cerebral function assessments which were included, namely cognitive function, PROMs, neuroimaging parameters and several cerebrospinal fluid parameters.

In large cohort studies, neuropsychiatric adverse events have been frequently observed in PWH on integrase inhibitors, with the presence of these neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with an increased risk of discontinuing ART therapies.Citation13 We specifically recruited PWH without overt neurological symptomatology. During the follow up period no neuropsychiatric adverse events evolved in our study. It is likely the population we have recruited were less prone to develop such neuropsychiatric side effects given we recruited individuals tolerating a raltegravir containing ART regimen without adverse events and who were willing to switch the integrase inhibitor component of their ART regimen.Citation26

In a retrospective cross-sectional study assessing tryptophan metabolism in individuals with acute HIV infection, increased kynurenine/tryptophan ratios are described to be associated with increased depressive symptoms.Citation27 Furthermore, in PWH with cognitive impairment higher phenylalanine/tyrosine ratios, representing an increased CNS PAH activity, were observed when compared to PWH without cognitive disorders.Citation27 In another retrospective cross-sectional study in virologically suppressed PWH, higher phenylalanine/tyrosine ratios were observed, but these were not associated with cognitive impairment.Citation24 Also, a trend towards lower plasma kynurenine/tryptophan ratios was associated with both cognitive impairment and depression.Citation24 In a further prospective study assessing PWH switching from efavirenz-based ART to dolutegravir-based ART, an increase in plasma kynurenine concentrations and improvements in CNS toxicity scores was reported.Citation28 In our study, we did not observe differences in either phenylalanine/tyrosine ratio in plasma or cerebrospinal fluid between study arms. However, plasma kynurenine/tryptophan ratios were found to be negatively correlated with lower global cognitive scores in the switch arm. These results should be interpreted with caution since this model was not adjusted for multiplicity and changes in the kynurenine/tryptophan ratio or global cognitive score were not observed separately in the individual study arms. In addition, this significant relationship was not present for the cerebrospinal fluid kynurenine/tryptophan ratio.

A difference in mean plasma tryptophan concentrations was observed between the study groups (p = 0.011) at day 120. This appears to be driven by an increase in plasma tryptophan in the switch arm (mean change 4.84 µmol/L; SD: 7.12) and a decrease in the control arm (mean change −4.6 µmol/L; SD: 6.61). Corresponding changes in kynurenine concentrations or the kynurenine/tryptophan ratio were not observed indicating that the observed changes are unlikely related to changes in IDO-1 enzyme activity as both changes in tryptophan and kynurenine concentrations would be expected. Given these differences are unlikely to be related to changes in IDO-1 enzyme activity it is possible the differences are not related to ART treatment effects in our study. Other possible explanations for the changes in plasma tryptophan concentration we have observed may be related to dietary intake which is known to affect plasma tryptophan concentration.Citation29,Citation30 We did not undertake dietary assessments in our study to assess any changes in dietary intake. Another limitation of the study is the lack of a negative HIV control group. This prevents from examining the associations of cerebral function parameters and tryptophan/phenylalanine metabolites.

We observed a difference in mean cerebrospinal fluid neopterin concentration between study arms at follow up (p = 0.049). This change in cerebrospinal fluid neopterin concentration was not associated with any other clinical parameters and therefore any clinical relevance of this observation is unclear. Neopterin was included as a marker of immune activation based on its correlation with IDO activity.Citation31

In a proof of concept study like this, the use of indicators of effect size could be very relevant to establish a hypothesis where non-statistically significant results are observed. This is the case for a trend of NAA/Cr ratio changes in the frontal gray matter favoring the switch arm (p = 0.07). However, this finding in isolation is particularly difficult to interpret since that difference involves an unexplained and unexpected worsening in NAA/Cr ratio in the control arm. See .

Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of dolutegravir [7.6 ng/mL (95% CI, 5.2–11.1] were in a similar range to those previously reported [13 ng/mL (range, 4–18 ng/mL)].Citation32 Other studies have described associations between dolutegravir cerebrospinal fluid concentration and neuropsychiatric adverse events.Citation33 Given our study comprised of PWH without overt neuropsychiatric adverse events, we do not have the ability to link the cerebrospinal fluid exposure of dolutegravir to such events. Other limitations of our study are the small sample size, the relative young age of the participants and the small number of female participants.Citation14

In summary, we observed no significant changes in clinical, cerebral imaging parameters or cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in this comprehensive assessment of cerebral pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters in virologically suppressed PWH without overt neuropsychiatric switching integrase inhibitor.

Acknowledgments

Some of the data presented in this manuscript were presented as a poster at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2019, March 3–7, 2019, Seattle, USA, poster presentation 443).

The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

We would like to thank the follow groups and individuals for their contributions (listed alphabetically):

Clinical Imaging Facility (CIF), Imperial College London

Albert Busza

Department of HIV Pharmacology, University of Liverpool, UK

David Back

Imperial College HIV Clinical Trials Unit, St. Mary’s Campus, London, UK

Ken Legg, Claire Petersen and Scott Mullaney

Section of Virology, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London

Steve Kaye, Myra McClure

Disclosure statement

MRK is an employee and shareholder of ViiV Healthcare Ltd. SK SDP are involved with The University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions web site www.hiv-druginteractions.org, which is sponsored by Abbott Laboratories, Gilead Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd, Pfizer, Tibotec Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline and Merck Sharp & Dohme. AW has received research grants, speaker honoraria and advisory fees from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck and Co and BMS. JU has received travel support and honoraria from Gilead Sciences. All other authors have none to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dore GJ, McDonald A, Li Y, et al. Marked improvement in survival following AIDS dementia complex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003;17:1539–1545.

- Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1243–1250.

- Nightingale S, Winston A, Letendre S, et al. Controversies in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(11):1139–1151.

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–1799.

- Winston A, Duncombe C, Li PC, et al. Does choice of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) alter changes in cerebral function testing after 48 weeks in treatment-naive, HIV-1-infected individuals commencing cART? A randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(6):920–929.

- Winston A, Arenas-Pinto A, Stohr W, et al. Neurocognitive function in HIV infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61949.

- Letendre S, Marquie-Beck J, Capparelli E, et al. Validation of the CNS penetration-effectiveness rank for quantifying antiretroviral penetration into the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(1):65–70.

- Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Di Giambenedetto S, et al. Efavirenz associated with cognitive disorders in otherwise asymptomatic HIV-infected patients. Neurology 2011;76(16):1403–1409.

- Menard A, Montagnac C, Solas C, et al. Neuropsychiatric adverse effects on dolutegravir: an emerging concern in Europe. AIDS. 2017;31(8):1201–1203.

- Borghetti A, Baldin G, Capetti A, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of dolutegravir and two nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in HIV-1-positive, virologically suppressed patients. AIDS. 2017;31(3):457–459.

- Bonfanti P, Madeddu G, Gulminetti R, et al. Discontinuation of treatment and adverse events in an Italian cohort of patients on dolutegravir. AIDS. 2017;31(3):455–457.

- Elzi L, Erb S, Furrer H, et al. Adverse events of raltegravir and dolutegravir. AIDS. 2017;31(13):1853–1858.

- Lepik KJ, Yip B, Ulloa AC, et al. Adverse drug reactions to integrase strand transfer inhibitors. AIDS. 2018;32(7):903–912.

- Hoffmann C, Welz T, Sabranski M, et al. Higher rates of neuropsychiatric adverse events leading to dolutegravir discontinuation in women and older patients. HIV Med. 2017;18(1):56–63.

- Llibre JM, Montoliu A, Miro JM, et al. Discontinuation of dolutegravir, elvitegravir/cobicistat and raltegravir because of toxicity in a prospective cohort. HIV Med. 2019;20(3):237–247.

- Overton ET, Kauwe JS, Paul R, et al. Performances on the CogState and standard neuropsychological batteries among HIV patients without dementia. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1902–1909.

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Patient Health Questionnaire Study Group. Validity and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study. Jama. 1999;282(18):1737–1744.

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571.

- Mora-Peris B, Bouliotis G, Ranjababu K, et al. Changes in cerebral function parameters with maraviroc-intensified antiretroviral therapy in treatment naive HIV-positive individuals. AIDS. 2018;32(8):1007–1015.

- Scott J, Underwood J, Garvey LJ, et al. A comparison of two post-processing analysis methods to quantify cerebral metabolites measured via proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in HIV disease. Br J Radiol. 2016;89(1060):20150979.

- Mora-Peris B, Watson V, Vera JH, et al. Rilpivirine exposure in plasma and sanctuary site compartments after switching from nevirapine-containing combined antiretroviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(6):1642–1647.

- Penchala SD, Fawcett S, Else L, et al. The development and application of a novel LC-MS/MS method for the measurement of Dolutegravir, Elvitegravir and Cobicistat in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2016;1027:174–180.

- Keegan MR, Chittiprol S, Letendre S, et al. Tryptophan metabolism and its relationship with depression and cognitive impairment among HIV-infected individuals. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2016;9:79–88.

- Mora-Peris B, Winston A, Garvey L, et al. HIV-1 CNS in vitro infectivity models based on clinical CSF samples. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(1):235–243.

- Yombi JC. Dolutegravir neuropsychiatric adverse events: specific drug effect or class effect. AIDS Rev. 2018;20(1):14–26.

- Grill M, Gisslen M, Cinque P, et al. Kynurenine-tryptophan and phenylalanine-tyrosine levels in cerebrospinal fluid in HIV infection. Paper presented at: 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, USA, March 2012.

- Keegan MR, Winston A, Higgs C, et al. Tryptophan metabolism and its relationship with central nervous system toxicity in people living with HIV switching from efavirenz to dolutegravir. J Neurovirol. 2019;25(1):85–90.

- Seyedsadjadi N, Berg J, Bilgin AA, et al. High protein intake is associated with low plasma NAD + levels in a healthy human cohort. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201968.

- Strasser B, Gostner JM, Fuchs D. Mood, food, and cognition: role of tryptophan and serotonin. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19(1):55–61.

- Dahl V, Peterson J, Fuchs D, et al. Low levels of HIV-1 RNA detected in the cerebrospinal fluid after up to 10 years of suppressive therapy are associated with local immune activation. AIDS. 2014;28(15):2251–2258.

- Letendre SL, Mills AM, Tashima KT, et al. ING116070: a study of the pharmacokinetics and antiviral activity of dolutegravir in cerebrospinal fluid in HIV-1-infected, antiretroviral therapy-naive subjects. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(7):1032–1037.

- Elliot ER, Wang X, Singh S, et al. Increased dolutegravir peak concentrations in people living with human immunodeficiency virus aged 60 and over, and analysis of sleep quality and cognition. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(1):87–95.