Abstract

Background: With an increase in life expectancy of people with HIV, there is a corresponding rise in comorbidities and consequent increases in comedications. Objective: This study compared comorbidity and polypharmacy among people with HIV and people without HIV stratified by age, sex, and race. Methods: This retrospective study utilised administrative claims data to identify adult people with HIV with antiretroviral therapy (ART) claims and HIV diagnosis codes from 01 January 2018 to 31 December 2018. Index date was the earliest ART claim or HIV diagnosis in the absence of ART claims. Inclusion required continuous enrolment for ≥12-month pre-index and ≥30-day post-index, along with ≥1 HIV diagnosis during baseline or follow-up. People with HIV were matched 1:2 with people without HIV on sociodemographic. Results were compared using z-tests with robust standard errors in an ordinary least squares regression or Rao-Scott tests. Results: Study sample comprised 20,256 people with HIV and 40,512 people without HIV. Mean age was 52.3 years, 80.0% males, 45.9% Caucasian, and 28.5% African American. Comorbidities were significantly higher in younger age people with HIV than people without HIV. Female had higher comorbidity across all comorbidities especially younger age people with HIV. Polypharmacy was also significantly greater for people with HIV versus people without HIV across all age categories, and higher in females. Across races, multimorbidity and polypharmacy were significantly greater for people with HIV versus people without HIV. Conclusions: Comorbidities and polypharmacy may increase the risk for adverse drug-drug interactions and individualised HIV management for people with HIV across all demographics is warranted.

Introduction

The past two to three decades were marked by substantial advances in the management of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), notably driven by better access to antiretroviral therapies (ARTs), which helped to improve clinical outcomes for people with HIV [Citation1]. One evident result has been increasing life expectancies among people with HIV, which have started to approximate that of the general population [Citation1–3]. Available evidence, however, suggests that people with HIV may also experience age-related health conditions more severely and earlier in their lives than people without HIV [Citation4,Citation5]. People with HIV appear more prone to conditions linked with ageing including cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and renal disease relative to people without HIV of similar age [Citation6].

Longer lifespans increase exposure of people with HIV to ARTs that allow more time for the development of comorbid conditions that may need additional pharmaceutical treatment. This raises the risk of adverse treatment effects, contraindications of drug use, and polypharmacy-related toxicities. Previous studies have indicated that ARTs are linked to elevated risk of comorbidities, including chronic kidney disease (CKD), CVD, and osteoporosis and fractures [Citation6–12]. For instance, abacavir (ABC)-based regimens may be associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) [Citation13,Citation14]. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) containing regimens have been implicated in increased risk of kidney toxicity and bone mineral density loss [Citation15–17]. However, Hill A. et al reported that TDF in a pharmacokinetic boosted ART appears to be more toxic, but no significant difference in toxicity in unboosted ART when compared to Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) [Citation18]. Studies have also shown that people with HIV have a higher risk of osteoporosis and bone fractures than people without HIV, regardless of treatment regimen [Citation7,Citation8,Citation12].

Furthermore, a prior analysis of the sample used in this study showed that people with HIV had significantly greater Charlson Comorbidity Index scores as well as multimorbidity burden [Citation19]. Among the comorbidities that were significantly different for people with HIV versus people without HIV were hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, CKD depression and substance abuse [Citation19]. In addition, non-ART prescription fills were greater in people with HIV relative to people without HIV, reflecting the greater polypharmacy burden among people with HIV [Citation19].

Still, comparative information related to comorbidities and comedications for people with HIV and people without HIV is especially deficient stratified by different age groups, sex, and race. A better understanding of the comorbidities and comedications in people with HIV is invaluable for the management of ART and non-HIV treatments and is critical for avoiding the use of agents that are contraindicated for specific comorbidities, whether it be because medications may precipitate or exacerbate comorbidities, or because of drug-drug interactions. The objective of this study was to describe and compare comorbid conditions and the comedication burden in people with HIV and people without HIV stratified by age, sex, and race.

Methods

Study design and data source

This is a retrospective case-control study that used medical and pharmacy claims, enrolment, and linked socioeconomic data from the Optum Research Database (ORD) for the period spanning 01 January 2013 through 31 January 2019. Enrolees with both medical and pharmacy coverage from commercial or Medicare Advantage with Part D (MAPD) plans were identified and allocated to the people with HIV cohort or a comparison group of people without HIV. The ORD, a proprietary repository of research data, is one of the largest and most complete in the United States and consists of medical and pharmacy claims information (including linked enrolment) from 1993 to present for more than 73 million lives. The ORD data in this study were statistically certified as de-identified for research purposes in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Human Research Regulations. No identifiable protected health information was extracted, so Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent procedures were not sought nor required.

Sample selection

People with HIV—inclusion/exclusion criteria

For the people with HIV cohort, the inclusion criteria required evidence of HIV/AIDS diagnosis codes and ART treatment, or if untreated, HIV/AIDS diagnosis codes, between 01 January 2018 and 31 December 2018 (identification period). The index date was defined as the date of the earliest ART claim or HIV/AIDS diagnosis in the absence of an ART claim. Continuous enrollment in the health plan with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 12-month baseline period pre-index, and at least 30-day after and including the index date as follow-up was also required. Adult people with HIV, ≥18 years old, as of the year of the index date were included. Enrolees with pharmacy claims for emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) only, without another agent were excluded. Enrolees with ART treatment on the index date and more than one code for PrEP or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) during the baseline or follow-up periods were also excluded.

People without HIV—inclusion/exclusion criteria

Initial inclusion in the people without HIV cohort required enrolment in a commercial or Medicare Advantage health plan with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 30 days between 01 January 2018 and 31 December 2018. Individuals in this initial people without HIV group were matched 2:1 to people with HIV on age, sex, race, geographic region, and insurance type. In addition, the index date for the matched people with HIV was the same as the index date for each corresponding people without HIV. Inclusion also required continuous health plan enrolment with medical and pharmacy benefits for 12-months prior to the index date (baseline period), and for at least 30 days after the index date (follow-up period). Enrolees with no medical claims with a diagnosis for HIV/AIDS, or no pharmacy claims for an ART, other than an NRTI, at any time during the baseline or follow-up were included. Enrolees were required to be ≥18 years of age as of the index date to be included.

Study measures

The characteristics recorded for both the people with HIV and people without HIV cohorts at baseline included age, sex, insurance type, US geographic region [Citation20], race, and ART class (for people with HIV cohort only) at index. A baseline Quan-Charlson comorbidity score was assessed using 12 condition categories, excluding HIV diagnoses [Citation21].

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) comorbid conditions [Citation22] and selected conditions identified by ≥1 indicator of inpatient admission or ≥2 ambulatory claims on separate dates based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Clinical Modifications (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) codes were also recorded. As described elsewhere [Citation19], the definition of comorbid condition was based on condition categories from the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or alternatively on a clinician’s review of relevant diagnosis codes. The full list of comorbid conditions is provided in Supplemental Table 1 [Citation23]. Multimorbidity, which was defined as the presence of ≥2 non-HIV comorbid medical conditions was determined from the number of comorbid medical conditions observed. Comedication and polypharmacy, which was defined as the presence of ≥5 non-antiretroviral (ARV) comedications, were assessed from the number of prescriptions fills by unique National Drug Code (NDC), excluding ART, during the 12-month baseline period, and expressed as a continuous variable and category (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5).

Statistical analyses

All analyses were stratified by age group, sex, and race. Study variables were analysed descriptively. Numbers and percentages were provided for dichotomous and polychotomous variables. Means, standard deviations (SDs), medians, and interquartile range (p25, and p75) were provided for continuous variables. Baseline demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, comorbidity burden, and comedication history were compared for people with HIV and matched people without HIV, using a z-test with robust standard errors in an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for continuous variables or a Rao-Scott test for categorical variables which account for the correlation between matched pairs. An a-priori α < 0.05 was set for statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Sample selection

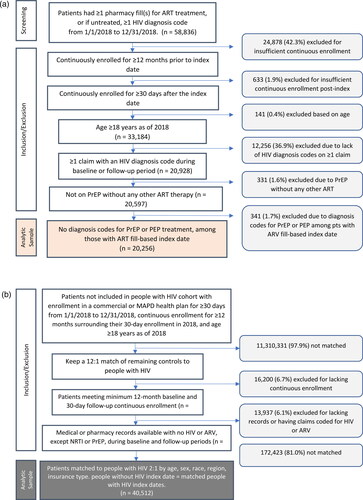

The initial sample of commercial and Medicare advantage enrolees with ≥1 pharmacy fills for ART or ≥1 HIV diagnosis code(s) during the identification period were 58,836 individuals. Upon applying pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria, the final analytic sample consisted of 20,256 people with HIV who were matched 1:2 to 40,512 people without HIV ().

Figure 1. (a) People with HIV cohort Identification and attrition. (b) Control cohort Identification and attrition. Abbreviations: ART: antiretroviral; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PEP: post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis; MAPD: Medicare advantage with part D; NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Study sample

Baseline characteristics by cohort

The mean (SD) age for the people with HIV cohort was 52.4 (13.4) years and 52.3 (15.0) years for people without HIV, p < .001. The 50–59 years age group had the largest (31.8%) and the 70+ group the smallest (10.0%) proportion of individuals relative to the other age categories in both cohorts. White/Caucasian (45.9%) were the largest proportion followed by Black/African American (28.5%) in the matched cohorts. Most enrolees were in the South, 59.1% in each cohort. The majority (about 95.0%) of both cohorts resided in urban areas. Approximately two-thirds (65.4%) were enrolled in commercial health plans and 34.6% in Medicare advantage plans. In the people with HIV cohort with an ARV on index date, 93.5% of patients were treated with NRTI, 62.6% with INSTI, 29.5% with NNRTI, 39.4% with a pharmacokinetic enhancer and 17.3% with PI ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants by cohort.

Baseline comorbidity scores and burden

The mean (SD) Charlson comorbidity score (excluding HIV) was significantly greater for the people with HIV cohort compared to the people without HIV group, 0.9 (1.6) vs 0.6 (1.3), p < .001. Comorbidity prevalence was significantly greater in the people with HIV than the people without HIV group for all conditions of interest with one notable exception, people without HIV had significantly greater T2DM burden relative to people with HIV, 15.8% vs. 13.9%, p < .001, respectively ().

Table 2. Baseline comorbidity burden for people with HIV versus people without HIV.

Comorbidity and comedication burden

Stratified by age

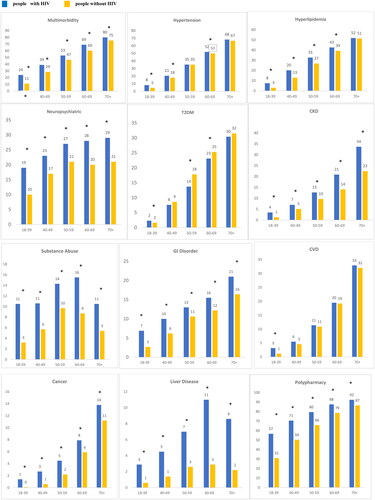

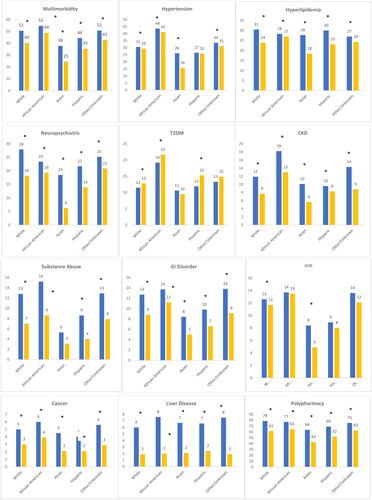

Multimorbidity was prevalent across all age categories, significantly greater in the people with HIV than people without HIV and was higher with increasing age: 18–39 (24.1% vs. 11.1%), 40–49 (38.9% vs. 28.6%), 50–59 (53.0% vs. 46.7%), 60–69 (69.0% vs. 60.2%) and ≥70 (80.0% vs. 75.4%) age groups, p < .001. Between cohort differences were notably larger in the younger age categories (18–39 [13.0%] and 40–49 [10.3%]) relative to older age categories, [50–59 (6.3%), 60–69 (8.8%) and ≥70 (4.6%)]. As shown in , the prevalence of comorbidities was significantly higher in people with HIV versus people without HIV across all age categories for neuropsychiatric conditions, CKD, liver disease and hypertension except in the 50–59 and 70+ age groups. For T2DM, however, the pattern was different, with higher prevalence in people without HIV compared to people with HIV in the 40–49 and ≥70 years age groups, while in younger age groups it was higher in people with HIV versus people without HIV. Further, relative to people without HIV, people with HIV had significantly higher prevalence of hyperlipidaemia in all age categories, except in the 70+ age group, of substance abuse, GI disorders, CVD, only in the 18–39 age group, and cancer.

Figure 2. Comorbidity and comedication burden stratified by age people with HIV people without HIV. *p<.05 for differences between people with HIV and people without HIV. All values presented are percentages. Multimorbidity defined as ≥2 non-HIV comorbid medical conditions. Polypharmacy defined as ≥ non-ART medications. Cancer: breast, liver, lung, leukaemia or lymphoma, colorectal, prostate, uterine, endometrial; CVD: acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, cardiac dysrhythmia, heart failure; GI: diarrhoea, nausea/vomiting, peptic ulcer disease, oesophageal reflux; liver disease: cirrhosis and other liver conditions, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH); neuropsychiatric: depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, bipolar/manic depression.

Polypharmacy was widespread and significantly greater for people with HIV compared to people without HIV across all age categories, with notably greater differences in the younger age groups ().

Stratified by sex

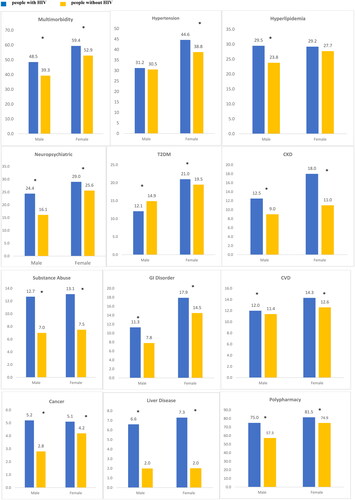

Multimorbidity was significantly greater in people with HIV versus people without HIV for both males (48.5% vs. 39.3%) and females (59.4% vs. 52.9%), respectively, p < .05. People with HIV, relative to people without HIV, had significantly larger proportions of neuropsychiatric conditions, males (24.4% vs. 16.1%) and females (29.0% vs. 25.6%) respectively, p < .05. Similarly, people with HIV of both sexes had significantly larger proportions of liver disease, cancer, CKD, and GI disease, compared to people without HIV individuals. Notably, a significantly lower proportion of male people with HIV compared to people without HIV had T2DM (12.1% vs. 14.9%), p < .05, while a significantly larger percentage of female people with HIV had T2DM (21.0 vs. 19.5), p < .05, compared with people without HIV individuals. Although not different for males, hypertension was significantly greater in females in the people with HIV cohort compared to people without HIV (44.6% vs. 38.8%, p < .05).

Polypharmacy was prevalent and significantly greater for males (75.0% vs. 57.3%) and females (81.5% vs. 74.9%) in the people with HIV vs. people without HIV cohorts, p < .05, respectively ().

Figure 3. Comorbidity and comedication burden stratified by sex. *p<.05 for differences between people with HIV vs. people without HIV. All values presented are percentages. Multimorbidity defined as ≥2 non-HIV comorbid medical conditions. Polypharmacy defined as ≥ non-ART medications. Cancer: breast, liver, lung, leukaemia or lymphoma, colorectal, prostate, uterine, endometrial; CVD: acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, cardiac dysrhythmia, heart failure; GI: diarrhoea, nausea/vomiting, peptic ulcer disease, oesophageal reflux; liver disease: cirrhosis and other liver conditions, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH); neuropsychiatric: depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, bipolar/manic depression

Stratified by age and sex

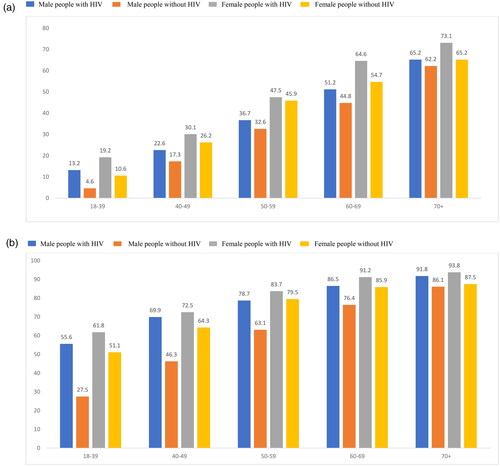

People with HIV had larger proportions of multiple comorbidities compared to people without HIV, p < .05, across sex and age categories, except among females in the 50–59 age group (). Notably, the differences in multiple comorbidity rates between people with HIV and people without HIV males were larger in the younger age categories, 18–39 (13.0%), 40–49 (11.5%), 50–59 (7.3%), 60–69 (8.8%) and 70+ (3.5%). The pattern was similar among female people with HIV and people without HIV individuals across the age categories, 18–39 (12.7%), 40–49 (6.1%), 50–59 (1.3%), 60–69 (8.8%) and 70+ (7.1%).

Figure 4. (a) Multimorbidity stratified by age and sex. p < .05 for all comparisons of people with HIV vs. people without HIV–except 50–59 years in females (p = NS). All values presented are percentages. Multimorbidity defined as ≥3 non-HIV comorbid medical conditions. (b) Polypharmacy stratified by age and sex. p < .05 for all comparisons of people with HIV vs. people without HIV. All values presented are percentages. Polypharmacy defined as ≥3 non-ART medications.

A similar pattern was observed for polypharmacy in the people with HIV and people without HIV cohorts stratified by age and sex (). People with HIV had significantly higher proportion of polypharmacy compared to people without HIV when assess by the intersections of sex and age groups: the differences between people with HIV and people without HIV were 18–39 (28.2%), 40–49 (23.5%), 50–59 (15.6%), 60–69 (10.1%) and 70+ (5.6%) for males, and for females, 18–39 (10.6%), 40–49 (8.2%), 50–59 (4.2%), 60–69 (5.4%) and 70+ (6.2%).

Stratified by race

Multimorbidity was significantly higher in the people with HIV compared with people without HIV cohorts across all races evaluated, White (50.6% vs. 40.3%), African American (54.7% vs. 48.8%), Asian (37.8% vs. 24.5%), Hispanic (44.4% vs. 35.4%) and other/unknown (50.7% vs. 42.8%), respectively, p < .05. People with HIV had significantly greater prevalence of multimorbidity and individual comorbidities relative to people without HIV across all races. However, notable non-significant difference was observed in T2DM and substance abuse in the Asian and Other/Unknown races, hypertension in Hispanics, and CVD in African Americans, Hispanics, and Other/Unknown.

Similarly, polypharmacy was significantly greater in the people with HIV versus people without HIV cohorts across all races, White (78.7 vs. 61.4%), African American (77.1% vs. 64.7%), Asian (63.6% vs. 42.6%), Hispanic (69.2% vs. 51.9%) and other/unknown (75.3% vs. 62.5%), respectively, p < .05 ().

Figure 5. Comorbidity and comedication burden stratified by race. *p<.05 for differences between people with HIV and people without HIV. All values presented are percentages. Cancer: breast, liver, lung, leukaemia or lymphoma, colorectal, prostate, uterine, endometrial: CVD: acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, cardiac dysrhythmia, heart failure: GI: diarrhoea, nausea/vomiting, peptic ulcer disease, oesophageal reflux; liver disease: cirrhosis and other liver conditions, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): neuropsychiatric: depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, bipolar/manic depression. Multimorbidity defined as ≥2 non-HIV comorbid medical conditions. Polypharmacy defined as ≥ non-ART medications.

Discussion

Advancement in the HIV treatment with highly effective ART have increased the life-expectancy of people with HIV approaching that of people without HIV. However, people with HIV may experience multiple comorbidities at their earlier age than people without HIV due to immune activation. This study described and compared the burden of comorbidities and comedications in people with HIV relative to people without HIV stratified by age, sex, and race.

In this study, there was a higher prevalence of comorbidities and polypharmacy in people with HIV compared to people without HIV, with relatively larger differences observed across cohorts in the younger age groups. Overall, females had greater comorbidity and comedication burdens. Females with HIV had higher comorbidity burden and polypharmacy than males with HIV and females without HIV. Asians appeared to have some of the largest differences between cohorts; however, the samples in that population were notably small. This finding addressed the lack of data and representation among the female population in HIV and ART. The findings in this study suggests the development of comorbidities among people with HIV at earlier age than people without HIV.

The most prevalent types of comorbidities in this study were CVD and renal conditions, with hypertension and hyperlipidaemia found in about one-third and one-quarter, respectively. Further, one-tenth of people with HIV and people without HIV had CKD. Similar findings were previously reported by Priest et al, which described ART treatment, comorbid conditions, and pill burden in patients with HIV based on claims data from 2007 to 2017 [Citation24]. The prevailing comorbidities and comedications were also similar. Moreover, similar patterns of common comorbidities were reported in a large sample of patients with HIV older than 65 in a study conducted from 2006 to 2009 [Citation25]. In a trend analysis that compared comorbidities in US patients with HIV, Gallant et al reported higher rates of common comorbidities for people with HIV compared with controls, with the highest rates observed among Medicare patients [Citation26]. Similar to the present study, control patients had higher rates of diabetes than those with HIV in the Gallant et al study [Citation26]. It is imperative that comorbidities in this particular population be given critical attention during patient management and patient care with ART as drug-diseases or drug-drug interaction can lead to unfavourable clinical outcomes.

Obesity and the risk of weight gain are a concern associated with treatment regimens that include INSTIs or TAF [Citation27–29]. Moreover, abacavir-based regimens may also be associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction [Citation13,Citation14]. ARV regimens containing TDF have been associated with increased risk of kidney toxicity and bone mineral density loss [Citation15–17], and the risk of TDF toxicities have been reported to be high particularly when used with pharmacokinetic boosters [Citation18]. The risk of kidney disease increases with advancing age and with TDF, and TDF/emtricitabine-containing regimens, and may be exacerbated by concomitant medications [Citation18,Citation27]. Hyperlipidaemia can also be exacerbated by certain ARTs, whereas medications used to treat hyperlipidaemia have potential drug-drug interactions with ARTs [Citation27,Citation30]. Hence, ART selection should be individualised or tailored and guided by presence or absence of comorbidities, adverse events or potential drug-drug interaction when given with other medications for multiple comorbidities.

Furthermore, consistent with prior studies, the most common neuropsychiatric conditions among the people with HIV were depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders, and these were at least 10% higher in prevalence than people without HIV [Citation31,Citation32]. In this study, neurocognitive disorders have been noted to be associated with older age in people with HIV, and worsened with treatment with efavirenz, which can cause acute psychosis, nightmares, irritability, difficulty concentrating and increased risk of suicide [Citation27]. On the other hand, GI disorders were more prevalent among the people with HIV than people without HIV, with the most common being oesophageal reflux.

Recent studies of treatments for comorbid conditions among elderly people with HIV have indicated potentially inappropriate disease management practices. These include under-prescribing of statin or other lipid-lowering agents despite higher CVD risk [Citation33] inadequate management of medications for neuropsychiatric [Citation32] neurological and psychiatric adverse events [Citation31] and under-recognition and treatment for metabolic complications associated with weight gain and diabetes [Citation28]. Yet previous studies have reported a high polypharmacy burden among people with HIV similar to the current study, associating polypharmacy or inappropriate prescribing to increased risk of adverse outcomes with particularly notable effects among older people with HIV [Citation34,Citation35]. Additional guidance is needed to manage individual risk factors and drug-drug interactions among people with HIV, especially older patients, and guide the choice of ART regimens that reduce the risk of precipitating or exacerbating comorbidities.

While the prevalence of polypharmacy was much higher in older patients compared to younger ones for both people with HIV and people without HIV, the differences in the prevalence was greater in the younger age categories for people with HIV compared to people without HIV. The younger population will likely experience the potential adverse effects of longer-term exposure to medications, and this cumulative impact must be minimised through evidence-based prescribing practices. Further analysis of comedication burden by age group, may be informative to the continuing discussion about optimising care for people with HIV.

Effective therapeutic advances and treatment management have transformed HIV from a terminal to a chronic condition, increasing not only life expectancy but also quality of life. Still, the most successful treatment outcomes would require the assessment of individual characteristics, especially patients’ comorbidities when considering ART treatment regimens [Citation24]. Rising longevity of people with HIV mandates treatment of HIV on a long-term basis with multi-disciplinary care supported with appropriate provider education programs.

Interpretation of these results must consider inherent challenges when data from administrative claims are repurposed for research. Claims data do not contain important data related to social determinants of health, limiting the ability of this work to provide insight into important areas of exploration related to this study population. Future work should address this important gap. Notably, the presence of a claim for a prescription fill does not guarantee the medications were taken or used as prescribed. Medications filled over the counter or received as samples from a provider or in a clinical trial may not be recorded in an individual’s insurance claims. Furthermore, the presence or absence of a diagnosis code on a medical claim is not necessarily proof of presence or absence of disease and may be particularly relevant to comorbidities. Misspecification of codes could result in misclassification of comorbid status. Identification of chronic conditions from medical claims may not capture all the conditions present, which is essential in individuals with multimorbidity. The 12-month window for identifying chronic conditions in this study, however, could help to mitigate misclassification bias. Clinical variables that may influence the choice of treatment, such as disease severity, medication side effects, clinical rationale, and personal preference are not generally available in claims databases. People without HIV who had no claims or prescriptions during the variable baseline or the one-month follow-up periods were excluded from the matching process, which could have introduced a misclassification bias, and possibly an underestimation of comorbidities, resulting in the exclusion of healthy individuals from the comparison cohort. Information on race was obtained from a linked data source and was not patient reported, however, it was imputed based on geographic information and patient names and is subject to error. Furthermore, the results of this study may not be generalisable to other populations, such as the uninsured or those covered by Medicaid, which may represent a sizeable proportion of people with HIV.

Conclusions

Comorbid conditions and polypharmacy burden were more prevalent in people with HIV than people without HIV, across age groups, sex, and race, however, differences were greater in the younger age groups. The differences between cohorts in comorbidity and polypharmacy were evident across all races. The study findings on age, sex, and race, highlight the need for an individualised approach to HIV management across all demographics, particularly in the use of ART, to avoid precipitating or exacerbating comorbidities and adverse events, and avoiding drug-drug interactions to improve patient outcomes. These results add to existing literature and underscore the importance of improving provider awareness of multimorbidity and polypharmacy in all people with HIV across age, sex, and race.

Consent form

This study used de-identified data in a manner compliant with the HIPAA. Institutional Review Board review and approval was neither required, nor sought.

Author contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript, and have given final approval of the version to be published. M.P., G.P., S.G., and J.M. were involved in the conception and design of the study and data interpretation. E.K.B. and K.M. were involved in the acquisition of data. M.P., G.P., and E.K.B. were involved in the data analysis. B.K.T. was involved in result review and interpretation, manuscript writing, and critical review of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Writing, editorial support, and formatting assistance was provided by Caroline Jennermann, MS, Bernard Tulsi, MS, and Gayle L. Allenback all employees of Optum, which was contracted and compensated by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA for these services.

Disclosure statement

G.P. and B.K.T. are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (MSD). S.G. was working under an internship with MSD in partnership with The University of Mississippi, MS, USA. M.P., E.K.B., and K.M. were employed with Optum Inc., which was paid to conduct the study under contract with MSD. M.P. is now employed by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation, Bethesda, MD, USA. P.K. reports grant/research support from GSK, MSD, and Gilead; stock ownership with Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, GSK, and Gilead; and service as consultant/advisory board member with AMGEN, GSK, MSD, and Gilead.

Data availability statement

Data used in this study cannot be publicly disclosed. Proprietary data in the Optum Research Database cannot be accessed without data security and privacy protocols in place, and a restrictive licence agreement to ensure oversight.

Additional information

Funding

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. 2021. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV; [accessed 2022 Jun 22]. Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/whats-new-guidelines

- Cahill S, Valadéz R. Growing older with HIV/AIDS: new public health challenges. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):e7–e15.

- Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) in EuroCoord, Lewden C, Bouteloup V, et al. All-cause mortality in treated HIV-infected adults with CD4 >/=500/mm3 compared with the general population: evidence from a large European observational cohort collaboration. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:433–445.

- Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1525–1533.

- Deeks SG, Phillips AN. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ. 2009;338(jan26 2):a3172–a3172.

- Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1120–1126.

- Brown TT, Hoy J, Borderi M, et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1242–1251.

- Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS. 2006;20(17):2165–2174.

- Guaraldi G, Prakash M, Moecklinghoff C, et al. Morbidity in older HIV-infected patients: impact of long-term antiretroviral use. AIDS Rev. 2014;16(2):75–89.

- Hemkens LG, Bucher HC. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1373–1381.

- Islam FM, Wu J, Jansson J, et al. Relative risk of renal disease among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):234.

- Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, et al. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large U.S. healthcare system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(9):3499–3504.

- Group DADS, Sabin CA, Worm SW, et al. Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study: a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet. 2008;371:1417–1426.

- Hsue PY, Scherzer R, Hunt PW, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness progression in HIV-infected adults occurs preferentially at the carotid bifurcation and is predicted by inflammation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1(2):1.

- Childs K, Welz T, Samarawickrama A, et al. Effects of vitamin D deficiency and combination antiretroviral therapy on bone in HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2012;26(3):253–262.

- Mills A, Crofoot G Jr, McDonald C, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in the first protease inhibitor-based single-tablet regimen for initial HIV-1 therapy: a randomized phase 2 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):439–445.

- Mocroft A, Kirk O, Reiss P, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate, chronic kidney disease and antiretroviral drug use in HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2010;24(11):1667–1678.

- Hill A, Hughes SL, Gotham D, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: is there a true difference in efficacy and safety? J Virus Erad. 2018;4:72–79.

- Paudel M, Prajapati G, Buysman EK, et al. Comorbidity and comedication burden among people living with HIV in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38:1443–1450.

- US Census. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/sahie/reference-maps/2017/us-regdiv.pdf. Accessed on 20 July 2022.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Classification Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp (discharges prior to 10/1/2015). Accessed on 21 June 2022.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW). Available from: https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories. Accessed on 21 June 2022.

- Priest JL, Burton T, Blauer-Peterson C, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment patterns among US patients with HIV. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(12):580–586.

- Friedman EE, Duffus WA. Chronic health conditions in Medicare beneficiaries 65 years old, and older with HIV infection. AIDS. 2016;30(16):2529–2536.

- Gallant J, Hsue PY, Shreay S, et al. Comorbidities among US patients with prevalent HIV infection-a trend analysis. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(12):1525–1533.

- Richterman A, Sax PE. Antiretroviral therapy in older people with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2020;15(2):118–125.

- Shah S, Hill A. Risks of metabolic syndrome and diabetes with integrase inhibitor-based therapy: republication. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2021;16(2):106–114.

- Venter WDF, Sokhela S, Simmons B, et al. Dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (ADVANCE): week 96 results from a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(10):e666–e676.

- Rao SG, Galaviz KI, Gay HC, et al. Factors associated with excess myocardial infarction risk in HIV-Infected adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(2):224–230.

- Mills AM, Antinori A, Clotet B, et al. Neurological and psychiatric tolerability of rilpivirine (TMC278) vs. efavirenz in treatment-naive, HIV-1-infected patients at 48 weeks. HIV Med. 2013;14:391–400.

- Nelson M, Stellbrink HJ, Podzamczer D, et al. A comparison of neuropsychiatric adverse events during 12 weeks of treatment with etravirine and efavirenz in a treatment-naive, HIV-1-infected population. AIDS. 2011;25(3):335–340.

- Emmons RP, Hastain NV, Miano TA, et al. Patients living with HIV are less likely to receive appropriate statin therapy for cardiovascular disease risk reduction. J Pharm Pract. 2021;35(4):568–572.

- Guaraldi G, Malagoli A, Calcagno A, et al. The increasing burden and complexity of multi-morbidity and polypharmacy in geriatric HIV patients: a cross sectional study of people aged 65 - 74 years and more than 75 years. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):99.

- Kong AM, Pozen A, Anastos K, et al. Non-HIV comorbid conditions and polypharmacy among people living with HIV age 65 or older compared with HIV-Negative individuals age 65 or older in the United States: a retrospective claims-based analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33:93–103.