Abstract

Introduction

Person-centered care (PCC) is considered a fundamental approach to address clients’ needs. There is a dearth of data on specific actions that HIV treatment providers identify as priorities to strengthen PCC.

Objective

This study team developed the Person-Centered Care Assessment Tool (PCC-AT), which measures PCC service delivery within HIV treatment settings. The PCC-AT, including subsequent group action planning, was implemented across 29 facilities in Zambia among 173 HIV treatment providers. Mixed-methods study objectives included: (1) identify types of PCC-strengthening activities prioritized based upon low and high PCC-AT scores; (2) identify common themes in PCC implementation challenges and action plan activities by low and high PCC-AT score; and (3) determine differences in priority actions by facility ART clinic volume or geographic type.

Methods

The study team conducted thematic analysis of action plan data and cross-tabulation queries to observe patterns across themes, PCC-AT scores, and key study variables.

Results

The qualitative analysis identified 39 themes across 29 action plans. A higher proportion of rural compared to urban facilities identified actions related to stigma and clients’ rights training; accessibility of educational materials and gender-based violence training. A higher proportion of urban and peri-urban compared to rural facilities identified actions related to community-led monitoring.

Discussion

Findings provide a basis to understand common PCC weaknesses and activities providers perceive as opportunities to strengthen experiences in care.

Conclusion

To effectively support clients across the care continuum, systematic assessment of PCC services, action planning, continuous quality improvement interventions and re-measurements may be an important approach.

Introduction

Person-centered care (PCC) is increasingly considered a fundamental approach to address the individual needs of clients to improve their access to and continuity of services [Citation1]. It is also widely considered to be a critical approach to help countries reach the UNAIDS 2030 targets [Citation2]. In Zambia the UNAIDS targets are within reach, with 89% of HIV-positive adults (aged 15+) aware of their status; 98% of adults diagnosed on antiretroviral therapy (ART); and 96% on ART virally suppressed [Citation3]. To ultimately reach and sustain progress, person-centered HIV treatment services that respond to the needs of individual clients offer an important opportunity [Citation2].

The International AIDS Society defines PCC as ‘…a multidisciplinary, integrated and long-term focused approach to care for people living with and affected by HIV that is responsive to their evolving needs, priorities and preferences’ [Citation4]. In line with this definition, a systematic review examining common elements of PCC identified implementation priorities including respect for the client and supporting their ‘physical, psychological, social and existential needs’, recruiting people within the client’s social ecology for support, as well as structuring services in a manner that enables long-term care continuation [Citation5].

Evidence suggests that activities commonly associated with PCC can lead to improved clinical outcomes. For example, integrating mental health services into HIV treatment programs has demonstrated increased client engagement in care and fewer experiences of HIV stigma [Citation6–8]. Peer-based outreach interventions have significantly increased identification of higher proportions of HIV positive key populations including men who have sex with men and female sex workers [Citation9]. Enabling client autonomy in selecting how they collect ART when compared to standard facility collection methods has demonstrated at least equal if not significantly improved outcomes related to adherence, retention and HIV viral suppression while helping to reduce gender disparities [Citation10–12]. Providing specialized services for adolescents has demonstrated improved treatment adherence [Citation13–15] and community and workplace‐based and male‐led peer support groups have also shown improvements across the HIV care continuum [Citation16].

PCC within the context of HIV treatment is an approach that is increasingly commonplace though, to date, there is a lack of clear guidance and tools including for its assessment and actions for improvement. To enable systematic implementation of high-quality PCC within HIV treatment services, implementation of a quality improvement (QI) approach that continually incorporates PCC assessment, feedback, action planning, improvement activities and re-measurement, in-line with the plan-do-study-act cycle, is a potentially important activity to ensure that PCC is implemented with fidelity [Citation17].

In Zambia, QI initiatives have been a bedrock of HIV treatment programs for over 15 years and have proven to be an effective approach to effect changes at specific pinpoints in the HIV care continuum in a variety of HIV treatment contexts and among a variety of populations [Citation18]. For example, to improve community-based HIV testing and rapid ART initiation among adolescents in Lusaka, QI activities helped to refine a package of interventions resulting in a 69% increase in rapid ART initiation [Citation19]. Also in Lusaka as part of a multi-level QI initiative focused on strengthening 3-month ART refill dispensation, participating facilities noted a 15% increase in three-month refill dispensation [Citation20]. A vast array of QI approaches and tools have been developed to assess service provision across the various components of the HIV treatment cascade (e.g. treatment initiation, viral load assessment). Many such tools have been broadly adopted and used across a variety of HIV treatment contexts [Citation20–22]. However, systematic assessment of PCC HIV treatment services that informs improvement action planning remains a critical gap.

Implementation of the PCC-AT for action planning

This study team previously conducted a systematic review resulting in the development of an HIV treatment PCC framework, including three domains and twelve sub-domains (Supplement 1) [Citation23]. The domains and subdomains formed the basis for the subsequent development of the Person-Centered Care Assessment Tool (PCC-AT) [Citation24]. This Excel-based tool measures health facility PCC service delivery within HIV treatment settings. PCC-AT implementation requires in-depth discussions amongst health facility staff to apply a benchmarking approach for the 56 performance expectations that feed into a score for each subdomain [Citation24]. Once scoring is complete, the PCC-AT process concludes with action planning with health facility staff which draws upon root cause analysis techniques to identify areas of weakness and priority setting to inform strengthening activities to address gaps. Detailed information on PCC-AT development has been published elsewhere [Citation25].

The PCC-AT was initially piloted at five health facilities in Ghana. To gather information on the tool’s feasibility, content validity, scoring consistency, and reliability, focus group discussions were held with 37 participating ART providers and key informant interviews were conducted with 20 ART clients selected from the same facilities. Results indicated that the PCC-AT is feasible to implement and that the domains and subdomains are in line with clients’ perspectives and experiences for PCC in HIV treatment services [Citation26].

To this study team’s knowledge, there is a lack of direct evidence available on associations between person-centered HIV treatment services and strengthened HIV clinical outcomes. Similarly, there is a lack of data available on the specific actions that HIV treatment providers’ identify as priorities to strengthen PCC services within the context of a comprehensive PCC assessment. To address these gaps, this study team implemented the PCC-AT across 30 health facilities in Zambia. Results that explore associations between PCC-AT scores and clinical outcomes have been submitted as a separate manuscript. This manuscript describes findings from action planning sessions that followed PCC-AT assessments with ART provider teams to understand their perspectives on activities that will strengthen PCC HIV treatment services across diverse Zambian HIV treatment facilities. The findings may be useful for other implementers who aim to build a broad understanding of the gaps that impede PCC within HIV treatment services and priority activities to strengthen PCC implementation.

Study objectives

The objectives of this study were to:

Identify the types of PCC strengthening activities that health facility staff identify as priorities, based upon low and high PCC-AT scores;

Identify common themes in PCC implementation challenges and activities that emerge from PCC-AT action plans by low and high PCC-AT score; and

Determine if there are differences in priority actions in facilities with high, medium and low numbers of patients on ART (TX_CURR); or by urban, peri-urban or rural status.

Methods

This study employed a mixed method, cross-sectional study design.

Site selection and study setting

The USAID DISCOVER-Health project supports the ministry of health (MOH) in Zambia to expand the reach of the health system to underserved areas and populations, through a direct service delivery and outreach model, at the lowest level of the health system (health post) to provide an integrated package of primary health services in Copperbelt and Central provinces. Project-supported sites (N = 66) in the two provinces were considered eligible for inclusion if the health facility: (1) provided direct HIV treatment services; and (2) expressed interest in scaling PCC to strengthen services. Project-supported health facilities co-managed with the Zambia correctional services were excluded from randomization (n = 9) due to differences in how services are delivered. The study’s sample frame used a proportionate stratification method to stratify all 57 eligible health facilities by rural, peri-urban and urban location. Using a random number generator in Excel, 30 health facilities were selected as data collection sites from the sampling frame and 29 of the facilities met the criteria with fidelity. Selected clinics had proportionate representation of urban, peri-urban and rural facilities to reflect the range of facility characteristics in the overall sample frame.

Participants

At each randomly selected health facility, anywhere between 3 and 13 health facility staff members were selected to participate in the PCC-AT on the day of data collection, depending on the availability of staff. Inclusion criteria for participants include at least one year of employment or volunteering at the study health facility and direct provision of or knowledge related to HIV treatment services (e.g. nurses, midwives, ART specialists and clinical officers; case managers, counselors, and community health workers; strategic information assistants and data officers). Though data managers do not provide direct client care, they have knowledge and experience of systems aspects that influence PCC. Participation of staff based on gender balance and experience was encouraged. Exclusion criteria for participation in the PCC-AT included any staff who had worked or volunteered at the study facility for less than one year, and any staff whose job description did not include direct HIV treatment service delivery or knowledge of how services are delivered.

Study procedure

Preparation

Prior to data collection, all data collectors underwent a two-day training led by the PCC-AT developers, consisting of a general introduction on the purpose and nature of the study, instruction on obtaining informed consent, interviewing and facilitation techniques, data storage, and practice implementing the PCC-AT.

PCC-AT implementation

Between September 1 and September 30, 2023, PCC-AT tool implementation at health facilities was conducted by full-time English-speaking project staff members who were divided into 5 data collection teams, each team composed of a data collector and a facilitator. The facilitator was responsible for introducing the study, collecting informed consent, and facilitating the PCC-AT process with the health facility team through a guided discussion. The discussions supported health facility staff to assess their own strengths and weaknesses with the aim to promote information sharing, a healthy internal dialogue, and consensus-building by including a range of staff who discussed institutional abilities, systems, procedures, and policies in various domains that influence PCC to arrive at a consensus answer for the 56 performance expectations across each of the twelve sub-domains.

Action planning

Once the scoring was complete, each PCC-AT pilot culminated in an action planning process. The facilitator: (1) facilitated discussions among health facility staff, supporting them to identify low scores on the PCC-AT; (2) led an examination of the responses to the performance expectations within low scoring sub-domains to identify why the facility had a low score; and (3) facilitated a discussion so that health facility staff identified potential solutions, identified the priority activities and a timeline for action. The remaining study team members took detailed notes that documented the discussion on an action planning template to capture the full universe of potential activities and rationale behind activity selection. PCC-AT implementation including action planning took place in the afternoons when patient flow was light, in a private room located within each health facility. See Supplement 2 for the Action Planning Template.

Qualitative analysis

The completed action plans were scanned and shared with the larger study team. Text from the action plans were uploaded to NVivo for in-depth analysis. A lead study team member led coding, drawing upon the PCC-AT subdomain performance expectations as the initial coding framework while further identifying any sub-codes under each sub-domain. A second study team member separately coded the action plans. Afterwards, the two study team members met to compare and resolve discrepancies in coding, including consultations with the wider study team. Coding of the action plans allowed for deconstruction and organization of the text, helping to uncover emergent themes, gaps and activities. Themes were ranked according to total unique facility counts in descending order to facilitate further analysis. Then, cross-tabulation queries were conducted to observe any relationships or trends between themes and sub-domain scores as well as themes and key study variables, including ART clinic volume and geographic type.

Quantitative analysis

The study team conducted descriptive analysis to observe and compare facility scores for each domain and subdomain, examining the minimum, maximum, and median scores.

Data security

Only the study team had access to the data. Participant confidentiality was protected throughout study procedures, including: (1) not including names of participants on data collection materials, (2) storing data in a secure place, (3) developing codes during qualitative data analysis so that any potential identifiers (e.g. staff positions) were not associated with data, and (4) maintaining strict adherence to the principles of voluntary participation, confidentiality, anonymity and protection of human subjects as guaranteed by the consent form.

Informed consent

Facilitators were trained in informed consent and confidentiality principles and protocols. All study participants were asked if they were interested in participating in the study. Study participants were presented with a study information sheet and a consent form in English which they were asked to sign if they agreed to participate in the study. The consent form explicitly stated that participation was voluntary. There was no monetary compensation for participation. Participants were reassured that refusal to participate would not have a bearing on their work assignments or payment in the future. Participants were also reassured that they could choose to stop at any point during the interview or discussion without penalty or bearing on their employment status. See Supplement 3 for the Informed Consent.

Ethical approval and protocol registration

The study was ethically approved by University of Zambia BioMedical Research Committee (UNZABREC) (reference number 4150-2023) and determined to be exempt from human subjects’ oversight from JSI’s IRB (IRB #23-36E).

Results

Description of study facilities

Thirty facilities carried out the PCC-AT; however, one facility was removed for analysis as it ultimately did not meet the inclusion criteria. provides a description of the number of facilities (n = 29) stratified by location, the facility setting (urban, peri-urban, and rural) and number of clients on treatment (TX_CURR).

Table 1. Comparison of facility characteristics, study sites versus sites not selected.

Participant description

Across the 29 study facilities, a total of 173 health facility staff participated in the study with sixty-two percent of study participants being female (). The mean years of experience was 6.3 (±4.0) years with the majority of participants (55%) having between 1 and 5 years of experience. Forty-eight percent of the study participants were Case Managers, Counselors, or Community Health Workers, followed by Nurses (30%) and ART Specialists or Clinical Officers (11%).

Table 2. Study participant characteristics.

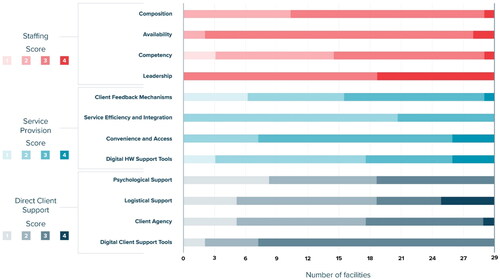

PCC-AT scores

The median score for staffing was 3 with staff competency having the largest range (1–4) and staff leadership having the smallest range (3–4). The median score for service provision was 2 with client feedback mechanism and digital health worker support tools having the largest ranges (1–4) and service efficiency and integration having the smallest range (2–3). The median score for direct client support was also 2 with logistical support and client agency having the largest range (1–4) and digital client support tools and psychosocial support having the smallest range (1–3). See .

Description of action plans

Challenges

Of the 29 facilities included in this analysis, all 29 (100%) identified specific challenges for at least one PCC-AT subdomain, with most facilities identifying challenges in multiple subdomains. At the domain level, most facilities identified challenges within service provision (n = 25), followed by direct client support (n = 22) and staffing (n = 15). Within service provision, most facilities identified challenges in the digital health worker support tools (n = 17) and client feedback mechanisms (n = 16) subdomains, then service efficiency and integration (n = 14) followed by convenience and access (n = 5). Within direct client support, most facilities identified challenges in the psychosocial support subdomain (n = 15), followed by client agency (n = 12), logistical support (n = 10) and digital client support tools (n = 7). Within staffing, the majority of facilities identified challenges in the competency subdomain (n = 12) and composition (n = 10), then availability (n = 6) and leadership (n = 3).

Priority actions for implementation

Of the 29 facilities, 27 (93%) named priority action items for implementation to address identified challenges in at least one subdomain. Most facilities identified priority action items in the service provision domain (n = 23), followed by direct client support (n = 19) and staffing (n = 15). Within service provision, most facilities identified priority actions in client feedback mechanisms (n = 14) and service efficiency and integration (n = 13), then digital health worker support tools (n = 11) and convenience and access (n = 4). Within direct client support, most facilities identified priority actions in psychosocial support (n = 13), followed by client agency (n = 11), logistical support (n = 8) and digital client support tools (n = 5). Within staffing, the majority of facilities identified priority actions in competency (n = 12) and composition (n = 9), then availability (n = 3) and leadership (n = 2). presents priority actions by subdomain, facility count and PCC-AT score

Table 3. Number of facilities with priority actions identified by subdomain and themes by subdomain score.

Common action themes and associated domains

The qualitative analysis identified 39 themes across the 29 action plans. The four most common themes emerged from approximately one-third of all health facility action plans. A higher proportion of rural facilities compared to the proportion of urban facilities identified actions related to stigma and clients’ rights training (44% vs 33%), as well as accessibility (translation to local languages that are culturally appropriate and using appropriate terminology), comprehensiveness and/or format of IEC materials (56% vs 7%) and GBV training (44% vs 13%). On the other hand, a higher proportion of urban and peri-urban facilities identified actions related to CLM compared to rural facilities (27% and 40% compared to 11%). While 44% and 40% of rural and peri-urban facilities identified actions related to lab infrastructure and staff and documentation of client feedback and actions (to address client feedback), no urban facilities identified these needs.

While 44% and 40% of low and medium volume facilities identified actions related to IEC materials, no high-volume facilities identified this need. Similarly, while 30% and 33% of low and medium volume facilities, respectively, identified actions related to lab and lab staff, no high-volume facilities identified this need. A higher proportion of high-volume facilities identified actions related to peer counselor assignments than medium or low volume facilities (40% versus 20% and 22%, respectively). presents themes ranked by number of unique facility counts and disaggregated by study setting and ART clinic volume.

Table 4. Top 10 action themes by facility geographic type and ART clinic volume.

Discussion

This paper describes findings from action plans associated with PCC-AT implementation. To our knowledge the PCC-AT is the first tool to standardize comprehensive assessment of PCC implementation within the context of HIV treatment settings. Analysis of improvement actions for PCC that respond to gaps identified through PCC-AT implementation is also novel. These findings provide a basis to understand common areas of weakness for PCC implementation across study facilities in Zambia and the potential activities that providers perceive as opportunities to strengthen experiences in care for people accessing ART.

Appropriate implementation of a QI approach

In examining PCC-AT scores, the study team noted that there were no strengthening actions identified by health facility staff for a high PCC-AT score (of 4). This indicates that in general, health facility staff participants understood the QI aspect of the activity and appropriately prioritized their attention to sub-domains where there were specific gaps in PCC identified. The study team also noted a relative balance in the number of facilities identifying challenges and the priority actions in each sub-domain indicating that facility staff were appropriately identifying QI opportunities when challenges were identified.

Decision-making authority

Participants undergoing the PCC-AT assessments included facility-based staff who have limited decision making authorities beyond patient care. Study team members observed that participants tended to identify actions that were within their locus of control though broader systems issues were also observed as challenges. To identify strengthening actions for systems issues, involvement of leadership and managers who did not participate in the PCC-AT and who are often working externally to the facility was required. For instance, under the logistical support subdomain, availability of client support for food and transport are common major gaps, however, beyond providing money from their own pockets, the majority of health facility staff conveyed that they do not feel empowered to advocate for these resources.

These findings align with the broader literature from the region indicating that a perceived lack of empowerment by ART providers is attributed to insufficiently inclusive communication between providers and program managers/supervisors, resulting in broad systems issues including lack of optimal client appointment procedures, long wait times for clients, supply chain issues including insufficient laboratory and clinical resources as well as resources to provide food, transport, lab vouchers and others that support clients’ broader needs to stay healthy and remain in care. These experiences limit providers ability to provide quality and comprehensive services to clients [Citation27,Citation28].

Through analysis of themes across identified challenges and priority actions, it becomes clear that PCC is both a systems and service issue. Given the lack of empowerment by health facility staff to address systems issues (above site), it is important to consider whether there is merit in integrating higher level program management and MOH authorities within the PCC-AT assessment process to enable a broader scope to address systems gaps. However, in doing so, therein lies a risk that facility-based teams may not feel as comfortable undergoing genuine reflection regarding the quality of PCC services if management figures are present. An alternative option is to develop PCC facility-based teams that undergo the PCC-AT and action planning process, while receiving support visits from program management/MOH authorities to check-in regarding systems issues that they may help to address and to cross-fertilize learnings across multiple facilities, which has commonly been done with broader QI initiatives [Citation29,Citation30].

Involvement of the community

Establishing linkages and partnerships with community-based organizations who can provide support for activities related to mental health and psychosocial support including home visiting and food assistance was also noted. Action plans identified the potential for CLM to provide important structure to client feedback mechanisms. The integration of people with lived experience within QI teams is an additional approach that may be considered in the future to enrich identification of gaps and improve actions moving forward. Mixed staff and client QI team composition has proven to be an effective intervention in other HIV treatment settings [Citation31].

Client feedback mechanisms

In-line with the CLM thematic findings, it is also important to note that client feedback mechanisms were a common activity discussed during action planning. The feedback mechanisms that were identified ranged along a spectrum from simply asking for client feedback, to examining feedback that clients are already providing, to making changes based upon client feedback, as well as to developing a robust external feedback system such as CLM. While some facilities may have had methods to gather client feedback, such as suggestion boxes – the mechanisms to regularly review the feedback and develop responsive activities, as well as to inform clients on the changes occurring in response to their feedback was largely lacking. Given the fundamental importance of client feedback to implement PCC with fidelity, this area should be a priority for PCC improvements within HIV treatment services. Our study team noted similar findings in Ghana where clients expressed hesitancy to provide feedback because they did not think their perspective would be considered, or they did not want to be considered a challenging client, or they did not want to add further burden on the staff. Without adequate client feedback mechanisms in place, it is challenging to know if PCC improvement activities are genuinely resulting in strengthened PCC experiences for clients. To overcome this important challenge, implementation of a minimum standard of care for PCC that systematically assesses, documents, and addresses clients preferences and concerns is critically important [Citation32].

Variances in improvement priorities

Analysis of themes revealed divergent priorities across facilities with varying patient loads (TX_CURR) and facility contexts (rural, peri-urban, urban). While we cannot positively state why themes varied, there were interesting trends to note. GBV training, laboratory analysis equipment, staff and facility accessibility, availability and accessibility of culturally-tailored IEC materials and peer support services or staff were identified more often as part of PCC strengthening activities within rural and peri-urban facilities, presumably due to less investments in infrastructure and resources, and perhaps lack of training on GBV, at these health facilities. In addition, facilities with low and medium patient loads more often identified GBV training, peer support services or staff, availability and accessibility of IEC materials, and laboratory analysis and accessibility as priority activities. High patient load facilities and facilities within urban areas more often identified digital tools and meetings with the higher-level (mother site) facilities or advisory committee as priority activities. The theme of CLM processes was identified nearly equally across geographic and TX_CURR categories.

Study limitations

While this study presents novel findings, it also presents some inherent limitations. The study facilities are limited to USAID DISCOVER-H supported sites in Zambia which may have more resources and staff trained in PCC activities than other facilities; the consensus and action plan discussions were facilitated by USAID DISCOVER-H project technical advisors; the gaps and identified actions may also vary from a more diverse selection of study facilities as USAID DISCOVER-H facilities are accustomed to standardized assessments associated with PEPFAR funding. Facilities not receiving PEPFAR funding and technical assistance may experience more challenges in undergoing a PCC-AT and action planning processes. While the PCC-AT underwent a content validity examination in Ghana with people on ART as part of the initial pilot, the PCC-AT process itself is limited to the perspectives and ideas of HIV treatment providers. However, to help address this challenge, a component of the PCC-AT includes assessing mechanisms to routinely receive feedback from clients on the quality of PCC delivered.

Conclusions

To effectively support clients across the care continuum, systematic and ongoing assessment of PCC services, action planning, improvement interventions and re-measurements may be an important approach to improve clinical outcomes for diverse clients. This study provides useful information on common gaps and priority actions identified by HIV treatment provider teams that are required to improve PCC within HIV treatment services. This study also elucidates the challenges in implementing PCC and the potential to better respond to the needs of people on ART. Implementation of the PCC-AT, including the ensuing action planning, aims to hold us as program implementers accountable to move beyond claiming that we support PCC, to actually assessing PCC and working with teams on the ground to continually strengthen the quality of PCC within HIV treatment services. Future research should examine the entire cycle of PCC action planning including follow-up assessments after implementation of PCC action plans to determine if the activities result in measurably improved person-centered HIV treatment services.

Informed consent

We confirm that all participants provided informed consent in order to participate in this research.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (99.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Eaton S, Roberts S, Turner B. Delivering person centred care in long term conditions. BMJ. 2015;350(350):h181.

- The Lancet HIV. UNAIDS strategy aligns HIV priorities with development goals. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(5):e245.

- UNAIDS. Zambia UNAIDS. 2015. [cited 2024 Apr 15]. http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/zambia.

- International AIDS Society. Person-centered care. [cited 2024 Apr 15]. https://www.iasociety.org/ias-programme/person-centred-care#:∼:text=Established%20by%20the%20IAS%20in%202021%2C%20the%20Person-Centred,and%20disseminating%20good%20practice%20models%20of%20person-centred%20care.

- Giusti A, Nkhoma K, Petrus R, et al. The empirical evidence underpinning the concept and practice of person-centred care for serious illness: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(12):e003330.

- Conteh NK, Latona A, Mahomed O. Mapping the effectiveness of integrating mental health in HIV programs: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):396.

- Chuah FLH, Haldane VE, Cervero-Liceras F, et al. Interventions and approaches to integrating HIV and mental health services: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(suppl_4):iv27–iv47.

- Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, et al. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS. 2019;33(9):1411–1420.

- Lillie TA, Persaud NE, DiCarlo MC, et al. Reaching the unreached: Performance of an enhanced peer outreach approach to identify new HIV cases among female sex workers and men who have sex with men in HIV programs in west and Central africa. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0213743.

- Duffy M, Sharer M, Davis N, et al. Differentiated antiretroviral therapy distribution models: Enablers and barriers to universal HIV treatment in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30(5):e132–e143.

- Lanzafame M, Vento S. Patient centered care and treatment in HIV infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2018;6:5–6.

- Barnabas RV, Szpiro AA, van Rooyen H, et al. Community-based antiretroviral therapy versus standard clinic-based services for HIV in South Africa and Uganda (DO ART): a randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(10):e1305–e1315.

- World Health Organization. Adolescent friendly health services for adolescents living with HIV: from theory to practice. Technical Brief. Vol WHO/CDS/HI. 2019. 2019. [cited 2024 Apr 15]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/adolescent-friendly-health-services-for-adolescents-living-with-hiv.

- Tapera T, Willis N, Madzeke K, et al. Effects of a peer-led intervention on HIV care continuum outcomes among contacts of children, adolescents, and young adults living with HIV in Zimbabwe. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(4):575–584.

- Ehrenkranz P, Grimsrud A, Holmes CB, et al. Expanding the vision for differentiated service delivery: a call for more inclusive and truly patient-centered care for people living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(2):147–152.

- Sharma M, Barnabas RV, Celum C. Community-based strategies to strengthen men’s engagement in the HIV care Cascade in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2017;14(4):e1002262.

- Santana MJ, Manalili K, Zelinsky S, et al. Improving the quality of person-centred healthcare from the patient perspective: development of person-centred quality indicators. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e037323.

- Heiby J. The use of modern quality improvement approaches to strengthen African health systems: a 5-year agenda. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(2):117–123.

- Dougherty G, Boccanera R, Boyd MA, et al. A quality improvement collaborative for adolescents living with HIV to improve immediate antiretroviral therapy initiation at 25 health facilities in Lusaka, Zambia. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2021;32(6):701–712.

- McCarthy EA, Subramaniam HL, Prust ML, et al. Quality improvement intervention to increase adherence to art prescription policy at HIV treatment clinics in Lusaka, Zambia: a cluster randomized trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175534.

- Ikeda DJ, Nyblade L, Srithanaviboonchai K, et al. A quality improvement approach to the reduction of HIV-related stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(3):e001587.

- World Health Organization. Standards for quality HIV care: a tool for quality assessment, improvement, and accreditation. World Health Organization; 2004. [cited 2024 Apr 15]. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43093/9241592559.pdf;sequence=1.

- Duffy M, Madevu-Matson C, Posner JE, et al. Systematic review: Development of a person-centered care framework within the context of HIV treatment settings in Sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2022;27(5):479–493.

- JSI. Person-Centered Care Assessment Tool. 2023. [cited 2024 Apr 15] https://www.jsi.com/resource/jsi-person-centered-care-assessment-tool/.

- Posner JE, Duffy M, Madevu-Matson C, et al. Assessing the person-centered care framework and assessment tool (PCC-AT) in HIV treatment settings in Ghana: a pilot study protocol. PLoS One. 2024;19(1):e0295818.

- Posner JE, Tagoe H, Casella A, et al. Staff perspectives on the feasibility of the person-centered care assessment tool (PCC-AT) in HIV treatment settings in Ghana: a mixed-methods study. HIV Res Clin Pract. 2024;25(1):2312319.

- Genberg B, Wachira J, Kafu C, et al. Health system factors constrain HIV care providers in delivering high-quality care: Perceptions from a qualitative study of providers in Western Kenya. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2019;18:2325958218823285.

- Julien A, Anthierens S, Van Rie A, et al. Health care providers’ challenges to high-quality HIV care and antiretroviral treatment retention in rural South Africa. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(4):722–735.

- Rabkin M, Achwoka D, Akoth S, et al. Improving utilization of HIV viral load test results using a quality improvement collaborative in Western Kenya. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2020;31(5):566–573.

- Dougherty G, Abena T, Abesselo JP, et al. Improving services for HIV-exposed infants in Zambia and Cameroon using a quality improvement collaborative approach. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021;9(2):399–411.

- Bluemer-Miroite S, Potter K, Blanton W, et al. “Nothing for us without us”: an evaluation of patient engagement in an HIV care improvement collaborative in the Caribbean. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2022;10(3):e2100390.

- Duffy M, Posner JE, Madevu-Matson C, et al. “The person cutting the path does not know his trail is crooked”. Drawing lessons learned from people accessing antiretroviral treatment services to propose a person-centered care (PCC) minimum practice standard. HIV Res Clin Pract. 2024;25(1):2305555.