Abstract

Background: Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States (US) remains below target, despite reported high efficacy in prevention of HIV infection and being considered as a strategy for ending new HIV transmissions. Here, we sought to investigate drivers for PrEP use and barriers to increased uptake using real-world data. Methods: Data were drawn from the Adelphi PrEP Disease Specific Programme™, a cross-sectional survey of PrEP users and PrEP non-users at risk for HIV and their physicians in the US between August 2021 and March 2022. Physicians reported demographic data, clinical characteristics, and motivations for prescribing PrEP. PrEP users and non-users reported reasons for or against PrEP use, respectively. Bivariate analyses were performed to compare characteris tics of users and non-users. Results: In total, 61 physicians reported data on 480 PrEP users and 121 non-users. Mean ± standard deviation of age of users and non-users was 35.3 ± 10.8 and 32.5 ± 10.8 years, respectively. Majority were male and men who have sex with men. Overall, 90.0% of users were taking PrEP daily and reported fear of contracting HIV (79.0%) and having at-risk behaviors as the main drivers of PrEP usage. About half of non-users (49.0%) were reported by physicians as choosing not to start PrEP due to not wanting long-term medication. PrEP stigma was a concern for both users (50.0%) and non-users (65.0%). More than half felt that remembering to take PrEP (57.0%) and the required level of monitoring (63.0%) were burdensome. Conclusions: Almost half of people at risk for HIV were not taking PrEP due to not wanting long-term daily medication and about half of current PrEP users were not completely adherent. The most common reason for suboptimal adherence was forgetting to take medication. This study highlighted drivers for PrEP uptake from physician, PrEP user, and non-user perspectives as well as the attributes needed in PrEP products to aid increased PrEP uptake.

Introduction

Despite advances in prevention methods, incident HIV infections continue, with over 36,000 new infections in the US in 2021 alone [Citation1]. Particular groups at risk of contracting HIV, including gay, bisexual, and other men who reported male-to-male sexual contact, as well as persons who inject drugs, accounted for the majority of these new infections [Citation1].

One of the key prevention strategies of new HIV infections is the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), antiretroviral medication aimed at preventing HIV infection upon exposure. PrEP may be taken as a daily or regular regimen, or on-demand in periods of increased exposure to risk [Citation2], and may be prescribed by any licensed practitioner in the US. Currently, two oral PrEP drugs are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, which was approved in 2012 [Citation3], and emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, approved in 2019 in men and transgender women at-risk of HIV [Citation4]. Updated CDC guidelines for PrEP now also recommend PrEP use for at-risk cisgendered women [Citation5]. Both have shown high efficacy in preventing HIV infection in both clinical trials and a real-world effectiveness study [Citation6–8]. In addition, a long-acting injectable formulation of cabotegravir gained FDA approval in 2021 for PrEP [Citation9]. Despite the proven efficacy of PrEP, only 24.7% of those who had an indication for PrEP use received a prescription in 2020 [Citation10].

A range of possible barriers to higher uptake of PrEP have been suggested, including lack of awareness and stigma, as well as access and financial restrictions [Citation11]. Furthermore, the effectiveness of PrEP in HIV prevention is dependent on the appropriate usage and optimal adherence among PrEP users [Citation12]. According to a previous systematic literature review study, adherence to PrEP among users is highly variable and commonly identified factors for non-adherence include unacceptable dosing regimens, side effects, low decision-making power, low HIV risk perception, and stigma [Citation13].

In 2019, the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) announced a new strategy for ending new HIV transmissions, with increased PrEP usage as a central component [Citation14], highlighting the need to understand the drivers of PrEP use and reasons for low uptake and poor adherence. However, studies that examine the drivers and barriers of PrEP uptake using real-world data that capture the perspectives of both providers and users are currently scarce. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to 1) identify demographic, clinical, and lifestyle characteristics of PrEP users and non-users at higher risk of acquiring HIV, 2) describe PrEP prescription patterns, adherence level and burden, 3) describe physician- and user/non-user-reported reasons for PrEP use or non-use, and 4) quantify drivers of PrEP use from both the user and physician perspectives.

Methods

Study design and data source

The study analysed real-world data derived from the Adelphi Real World PrEP Disease Specific Programme (DSP)™, a cross-sectional survey with elements of retrospective data collection from physicians and their consulting current PrEP users and non-users at risk for HIV in the US, between August 2021 and March 2022.

The DSP methodology has been previously described, validated and demonstrated to be representative and consistent over time in a variety of conditions [Citation15–17]. The DSP is based on a pseudo-random sample of physicians and their consulting PrEP users and non-users. Briefly, following completion of a screener survey, physicians were requested to complete patient record forms for the first eligible individuals consulting with them. Physicians were requested to return data for eight PrEP users and two consulting individuals who were in the specific HIV risk categories defined (see below), but did not receive PrEP. Each record form captured data regarding demographic, clinical and lifestyle characteristics, PrEP use history, as well as physicians’ reasons for prescribing or not prescribing PrEP, and satisfaction with PrEP in users.

Each PrEP user or non-user for whom the physician filled in a patient record form was invited to complete a voluntary self-completion form, covering relationship and partner details, reasons for taking or not taking PrEP, side effect profile of PrEP drugs, medication burden, and adherence to PrEP.

Participants

In order to be eligible for taking part in the study, physicians were required to be practicing as a primary care physician or infectious disease specialist, consult with at least three patients per month who receive PrEP medication and manage at least ten patients who either inject drugs, had a recent bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) or have a history of inconsistent or no condom use with sexual partner(s).

PrEP users were included if they were prescribed emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide for the purpose of PrEP at the time of survey. PrEP non-users at risk for HIV were defined as being a sexually active person and having at least one of the following attributes: having an HIV-positive partner; being recently diagnosed with bacterial STI; a history of inconsistent or no condom use with sexual partner(s); being a current injection drug user; or having previously been prescribed non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis. Exclusion criteria were having a confirmed diagnosis of HIV, being under the age of 16 or taking part in a clinical trial for PrEP.

Study measures

Baseline demographic variables reported by physicians included age, race/ethnicity, sex assigned at birth and current gender identity, body mass index (BMI), sexual orientation (physician selected orientation from a pre-defined list as homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual or pansexual, or other), sexual risk behaviors, history of drug abuse, employment status, education status, and health insurance status.

Clinical data abstracted by physicians from records included diagnosed medical conditions, STI history, mental health status, history of substance abuse, and PrEP side effects. Physicians also completed surveys on their motivations for prescribing or not prescribing PrEP for any given patient in the study, level of satisfaction with PrEP and the burden of taking PrEP. PrEP users reported their reasons for wishing to be prescribed PrEP, details regarding adherence to PrEP, and motivation for using PrEP. Non-users at risk for HIV provided data regarding their motivation for not using PrEP.

Patient-reported outcomes measures

The Adelphi Adherence Questionnaire (ADAQ©) is an 11-item non-disease specific, patient-reported outcome questionnaire designed to measure medication adherence. Items feature five ordinal response options regarding the extent of medication non-adherence (i.e. never, rarely, sometimes, often, and stopped taking medication completely), with higher scores indicating poorer adherence. One of these items, item 2 also includes a sixth response option: ‘I have not been advised to take my medication(s) at a certain time’. The overall ADAQ score is calculated from the unweighted average of the 11 items of the ADAQ, where 0 = complete non-adherence and 4 = complete adherence [Citation18].

The Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) assesses patient treatment adherence and prescription refilling adherence in a 12-item non-disease specific measure, each scored on a four-point Likert scale, leading to overall adherence scores of 12 (not adherent) to 44 (completely adherent) [Citation19].

Statistical analysis

Data were shown as proportion and percentage of the total cohort or as mean and standard deviation. Missing data were not imputed; therefore, the base size may vary and is reported separately for each variable.

PrEP users and non-users were compared using t-tests for normally distributed numeric variables and ordinal categorical data were analysed using Mann–Whitney tests. Dichotomous categorical data were analysed using Fisher’s exact tests and unordered categorical data were analysed using Chi-squared tests. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In order to quantify the relative contributions of individual factors to the likelihood of prescribing PrEP, an elastic net logistic regression was performed. Only individuals for whom both physician and user/non-user-reported data were included in the logistic regression. A 10-fold cross-validation was used to determine the mixing parameter alpha and the penalty parameter lambda. Associated variables were selected from the model, and the size and directionality of variable effects on the likelihood of receiving PrEP prescriptions were determined. All analysis was performed using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 61 physicians participated in the study, which led to enrollment of 480 current PrEP users and 121 PrEP non-users, for whom data were provided. Characteristics of contributing physicians are shown in Supplementary Table 1, and demographic characteristics of PrEP users and non-users are reported in . Overall, the mean (SD) age of participants was 34.7 ± 10.8, 85.0% were assigned male at birth and 73.0% were homosexual.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the study population, PrEP users and non-users at risk for HIV.

Current PrEP users were likely to be older (p = 0.012) and male at birth (p = 0.025) and homosexual (p = 0.003) than non-users. Employment status and education level were not significantly different between those on PrEP and non-users. Overall, most participants had commercial insurance, but this was significantly more common in those taking PrEP (p = 0.001). Non-users included significantly more Medicaid-insured (p = 0.001).

Clinical characteristics

shows physician-reported clinical and lifestyle characteristics, comparing PrEP users and non-users. Overall, the majority of participants had diagnosed medical conditions, of which anxiety and hypertension were most commonly reported, without significant differences between users and non-users.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of the overall study population, PrEP users and non-users at-risk for HIV.

PrEP users were less likely to have had an STI than non-users (p < 0.0001) in general at the time of survey. Non-users were more frequently reported to have infections with gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis (p < 0.001, p = 0.019, and p = 0.016, respectively) at the time of survey. Overall, PrEP users were more likely to have received vaccinations, including COVID-19 and seasonal influenza vaccinations than non-users. Most participants were reported to have no or mild mental health problems, which was not significantly different between groups.

Lifestyle characteristics

The majority of both groups had no history of substance use, with no significant differences. Overall, the majority of participants had never used injection drugs, but it was significantly different between PrEP users and non-users (p = 0.026), with a relatively higher proportion of PrEP users reported as never used injection drugs.

Overall, participants were most commonly reported to not be in a relationship (35.0%) or to be in a monogamous relationship (29.9%), with no significant differences between groups. In the majority of cases, individuals reported their partners were also using PrEP (56.5%), with no significant differences between PrEP users and non-users.

The type of sexual partners was not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.055), with a greater frequency of PrEP users reported as having more than one regular sexual partner while the non-users were reported as having a higher frequency of both regular and casual sexual partners ().

Table 3. Lifestyle characteristics in the overall study population, PrEP users and non-users at-risk for HIV.

The sexual identity and the HIV status of the participant’s sexual partners were also different between groups. PrEP users were less frequently reported as having a partner who is a man who has sex with men (MSM; p = 0.012), but more likely reported as having a partner who is HIV-negative and taking PrEP (p < 0.001). The status of casual sexual partners was not significantly different between groups; the most commonly reported type of partner for both groups was MSM.

Current PrEP usage

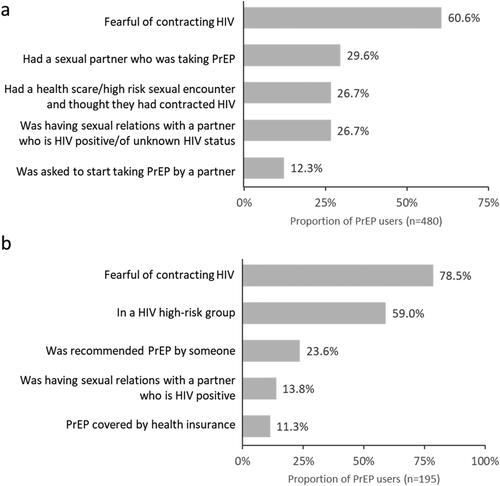

The most common physician-reported reason for prescribing PrEP was the PrEP users’ fear of acquiring HIV (). The most commonly reported reason mentioned by participants for taking PrEP was also being fearful of acquiring HIV (), followed by self-reported perception of being at high-risk for acquiring HIV.

Figure 1. Five most commonly stated reasons for taking PrEP, as reported by a) physicians and b) PrEP-users. Multiple responses could be selected; therefore, values add up to more than 100%.

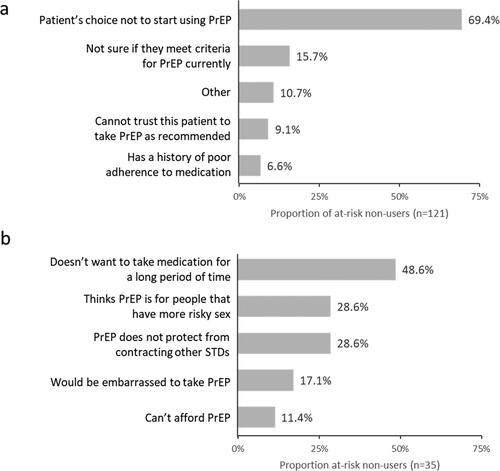

Physicians reported that the majority of cases where PrEP was not prescribed were due to the non-user’s choice (). The most common reasons for not taking PrEP reported by the non-users () were not being willing to take medication for a long period of time, a perception that PrEP is for people whose sexual behavior put them at a greater risk of acquiring HIV, and the fact that PrEP does not protect the user against acquiring other STIs.

Figure 2. Five most commonly stated reasons for not taking PrEP, as reported by a) physicians and b) non-users at risk for HIV. Multiple responses could be selected; therefore, values add up to more than 100%.

shows physician-reported reasons for PrEP usage and current regimen used. The majority of current PrEP users were taking PrEP on a daily basis (90.0%), followed by on-demand or event driven use (5.0%), four pills per week (4.0%), and holiday PrEP (1.0%). About one-third (32.5%) of current PrEP users were reported to experience side effects from PrEP usage.

Table 4. Physician-reported current PrEP regimen and reasons for PrEP usage.

The most common physician-reported factors for continued use of PrEP were having a regular or casual HIV-positive sexual partner, having multiple male sexual partners, having regular unprotected receptive anal sex, a history of inconsistent or no condom use, and having a partner whose HIV status is unknown.

The most frequently physician-reported reason for daily administration was the ease for the user to remember taking their medication, whereas the most commonly reported reasons not prescribing PrEP daily was PrEP users’ ease and a dislike of taking daily medication.

Factors driving PrEP prescription

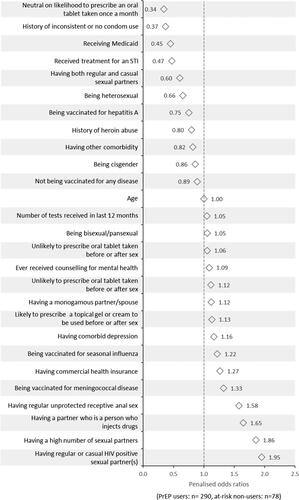

The penalised odds ratios resulting from the regression analysis on factors contributing to PrEP prescription are shown in for the covariates considered important by the model. The physician being likely to prescribe a once-a-month oral tablet, and potential users having a history of inconsistent condom use were amongst the factors negatively associated with PrEP prescription. The person having regular or causal HIV positive sexual partners, and a high number of sexual partners showed a positive association with PrEP prescription. People who had partners who injected drugs and regular unprotected receptive anal sex were also positively associated with PrEP prescription.

PrEP burden and adherence

The majority of physicians considered side effects not at all burdensome for PrEP users (). Remembering to take PrEP was reported to be slightly bothersome for 42.5% and moderately to extremely burdensome for 14.3% of users, respectively. The level of monitoring was viewed to be slightly bothersome in 42.3% of cases and moderately to extremely bothersome in 20.4%.

Table 5. Burden of taking PrEP and adherence to treatment.

Physicians stated the majority of PrEP users to be either completely (58.7%) or mostly (32.2%) adherent to their PrEP regimen. The number of occasions of non-adherence within the two months prior to survey was relatively low. Users had a single day of non-adherence a mean of 1.0 ± 2.2 times in the previous month, 0.4 ± 0.8 occasions of two to three days of non-adherence, and few occasions of longer periods of non-adherence. This was reflected in users’ favorable scores in two measures of adherence, with users scoring 0.45 ± 0.52 on the ADAQ scale and 15.7 ± 4.2 on the ARMS scale for adherence. In the majority of cases, users reported not taking their medication due to forgetting to take the pills and not having the medication with them.

Discussion

Despite being highly effective in preventing new HIV infections, PrEP uptake remains significantly below target. In this study, current PrEP users were more likely to be cisgender male and be homosexual than non-users, with relatively few cisgender females or heterosexual PrEP users in the cohort. A previous report has shown that PrEP awareness and uptake amongst cisgendered women in the US remains low, with half of women at risk for HIV reporting to be aware of PrEP and 13.7% intending to use PrEP [Citation20–22]. This is despite the fact CDC guidelines for PrEP use being updated in 2021 to include recommending PrEP use for cisgendered women at risk for HIV [Citation5]. Similarly, PrEP awareness and uptake among heterosexual men is very low at 7% and <1% of men at risk for HIV, respectively [Citation23]. Uptake among cisgender female and heterosexual men is further limited by these groups perceiving themselves to be at lower risk of acquiring HIV than MSM. In a large cohort of people undergoing HIV testing, cisgendered women were considerably less likely to view themselves as being at-risk for HIV, and the perceived lack of risk was the most common reason for not using PrEP [Citation24].

Furthermore, there may also be a physician bias in their decision to choose individuals with whom to discuss or offer PrEP, and whom to prescribe PrEP, which has been the subject of several recent studies in the US. Physicians rated men who have sex with women as being at lower risk of acquiring HIV than MSM or persons using injection drugs [Citation25]. Race or ethnicity and partner type of a consulting individual may also influence physician perception of their risk [Citation26].

Despite these potential biases, and prescription data from health insurance database studies suggesting proportionally lower rates of PrEP uptake amongst Black/African American populations [Citation27], in our cohort there was no significant difference observed in PrEP users and non-users by race or ethnicity. It may be the case that our study sample are more health-aware than a random sample of the general population due to being recruited at the point of consulting with a healthcare professional.

Contrary to published data [Citation28,Citation29], our study showed PrEP users had significantly lower proportion of reported STIs. Although the PrEP users in our cohort were more likely to have a single monogamous partner, many users also had casual sexual partners, making this unlikely to be a factor in determining the lower rate of STIs. However, the PrEP users in our study may be more risk aware than PrEP non-users, given they were more likely to be vaccinated for a range of diseases and less likely to have previous or current substance use issues. Unexpectedly, inconsistent condom use was also found to be negatively associated with the likelihood of being prescribed PrEP in our cohort; perhaps, this indicates that PrEP users may have high levels of risk awareness. However, a study using a larger sample size is warranted to further explain this specific finding.

The main drivers for taking PrEP were fear of acquiring HIV, user-perceived high-risk sexual encounters, the user having a sexual partner who was taking PrEP and being requested by a partner to take PrEP. This was reflected in the significantly higher proportion of PrEP users in our cohort who had a regular sexual partner who was also a PrEP user.

Reasons for not taking PrEP also included lack of perceived risk. PrEP non-users in this cohort showed significant risk markers, including high levels of STI, and having a high proportion of sexual relationships with groups at increased risk, such as those with an unknown HIV or PrEP status or MSM. This indicates that PrEP non-users likely underestimating their risk of acquiring HIV. This suggests increasing self-perceived risk awareness in groups at-risk for HIV through campaigning and education may also boost PrEP uptake. Wider uptake of less burdensome modes of PrEP administration, such as long-acting formulations, may also make PrEP use more attractive to current non-users.

Although cost implications were not the most common reasons for using or not using PrEP, insurance coverage was a reason for use for 11.3% of PrEP users and being unable to afford PrEP was a reason for non-use in 11.4% of the non-users. Notably, cost was a significant driver in choosing a dosing regimen, with 31.8% of users who did not use PrEP daily citing cost concerns as a reason. This is in line with earlier work suggesting cost may be a barrier to wider PrEP uptake [Citation30], and may particularly hinder adoption in minority groups who are at greater risk of contracting HIV [Citation31]. More cost-effective PrEP options may, therefore, further increase uptake.

Several motivations for not prescribing or taking PrEP may also suggest the need for novel formulations which can decrease the burden of taking PrEP. The most common reason for non-users to refuse PrEP was not wanting to take medication for a long time, and the two commonly cited reasons for physicians not to prescribe were being unable to trust the user to take PrEP as recommended and previous history of poor medication adherence. Additionally, the most common reason for having a daily PrEP regimen was the ease for the user to remember to take their medication, and a common reason for not using daily PrEP was not wanting to take medication every day.

Long-acting PrEP formulations that address these concerns may improve PrEP uptake and adherence, and adoption has been recommended by the World Health Organization [Citation32]. Long-acting injectable cabotegravir have been shown to be highly effective at preventing HIV infections [Citation33], and in use since its FDA approval in 2021 [Citation9]. When given the choice, although many MSM would prefer long-acting injectable formulations [Citation34], uptake may be still limited due to lack of user’s or physician’s awareness [Citation35,Citation36], cost [Citation37] and perceived lack of long-term safety data [Citation35]. Other issues including risk of resistance have also been noted [Citation37], highlighting the need for continued development of additional long-acting formulations.

The majority of PrEP users in our cohort were rated by their physicians to be completely or mostly adherent, with few occasions of non-adherence and correspondingly favorable scores on two patient-reported outcome measures of adherence. The most common reasons for suboptimal adherence to PrEP were forgetting to take medication, or the user not having their medication with them. This, combined with the fact that the majority of users found having to remember to take their medication burdensome to some extent, may further reiterate the need for long-acting regimen to maximise adherence.

This study comes with some limitations. The study population may not be representative of the wider population of PrEP users and non-users, as the DSP data only includes those who were consulting with their physician at the time of the survey. Participants who consult more frequently may have a higher likelihood of being included and may have different risks than those who were not included. The DSP is based on a pseudo-random sample of physicians and their consulting PrEP users and non-users. While minimal inclusion criteria governed the selection of participating physicians, participation may be influenced by willingness to complete the survey. To minimise selection bias, physicians were asked to provide data for a consecutive series of both eligible PrEP users and non-users. Although definitions of populations that were at-risk were provided to physicians, eligibility was ultimately based on the judgement of the physician. This may mean that patient which may have met guideline-based criteria for being at-risk, but were not perceived to by their physician, may have been excluded from the study. However, it is representative of the physician’s real-world classification of their consulting population. Recall bias, a common limitation of surveys, may have affected responses of physicians. However, physicians did have the ability to refer to their clinical records while completing the survey, thus minimising the possibility of recall bias. Furthermore, data were collected at the time of appointment to reduce the likelihood of recall bias where the opinion of the physician was required.

A response bias where PrEP users and non-users answer in a manner that is perceived to be more favorable may also have skewed outcomes in our survey.

Conclusion

Taken together, this study highlights several possible means to increase PrEP use. Increased education and awareness, particularly in currently underserved populations, such as cisgendered women and heterosexual men, as well as increasing physician awareness of guidelines and risk status of consulting individuals, may increase uptake. Furthermore, there is a clear need to increase the development of less burdensome, long-acting regimens, in addition to injectables, for those who may find a daily dosage schedule burdensome and whose physicians have doubts about their adherence levels. Expanding the dosing options available to potential PrEP users may lead to increased uptake, and subsequently to a reduction in HIV transmission.

Human subjects’ protection

Ethical approval was obtained from Pearl Institutional Review Board (21-ADRW-109). Data collection was non-interventional and adhered with international ethical standards with no risk to human participants. The survey was performed in full accordance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) 1996 [Citation38] and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Author contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript, and have given final approval of the version to be published. AM, FH, TH, and PS were involved in the design, analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript development of the study. YW was involved in the study conception, design development, data interpretation, and critical review of the manuscript. BKT was involved in the data interpretation, manuscript development, and critical review of the manuscript.

Statements and declarations

Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the Adelphi Real World PrEP Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP). The analysis described here used data from the Adelphi Real World PrEP DSP. The DSP is a wholly owned Adelphi Real World product. Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, Rahway, NJ, USA is one of multiple subscribers to the DSP. Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, did not have any influence in the survey through either contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection. Publication of survey results was not contingent on the subscriber’s approval or censorship of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

All data, i.e. methodology, materials, data, and data analysis, that support the findings of this survey are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. All requests for access should be addressed directly to Fritha Hennessy at [email protected].

Results in part were presented at the 2023 IDWeek Conference, 10–15 October 2023, Boston, US.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.8 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Niels Haan of Adelphi Real World on behalf of Adelphi Real World, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines [Citation39].

Disclosure statement

AM, FH, TH, and PS are employees of Adelphi Real World. BKT is employee and YW is employee and shareholder of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2017–2021. HIV surveillance supplemental report, 28. Atlanta (GA): 2023.

- Molina J-M, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2237–2246.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586–589.

- The Lancet H. New PrEP formulation approved…but only for some. Lancet HIV 2019;6(11):e723.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States – 2021 update clinical practice guideline. 2021. [accessed 01 August 2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

- McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60.

- Sagaon-Teyssier L, Suzan-Monti M, Demoulin B, et al. Uptake of PrEP and condom and sexual risk behavior among MSM during the ANRS IPERGAY trial. AIDS Care. 2016;281(1):48–55.

- Mayer KH, Molina JM, Thompson MA, et al. Emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide vs emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (DISCOVER): primary results from a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):239–254.

- Landovitz RJ, Donnell D, Clement ME, et al. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):595–608.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2021. HIV surveillance supplemental report, 28. Atlanta (GA): 2023.

- Mayer KH, Agwu A, Malebranche D. Barriers to the wider use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: a narrative review. Adv Ther. 2020;37(5):1778–1811.

- Murchu EO, Marshall L, Teljeur C, et al. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical effectiveness, safety, adherence and risk compensation in all populations. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5):e048478.

- Sidebottom D, Ekström AM, Strömdahl S. A systematic review of adherence to oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV – how can we improve uptake and adherence? BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):581.

- Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, et al. Ending the HIV epidemic. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845.

- Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, et al. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-specific programmes - a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–3072.

- Babineaux SM, Curtis B, Holbrook T, et al. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the disease specific programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e010352.

- Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:371–380.

- Bentley S, Morgan L, Exall E, et al. Qualitative interviews to support development and cognitive debriefing of the Adelphi Adherence Questionnaire (ADAQ©): a patient-reported measure of medication adherence developed for use in a range of diseases, treatment modalities, and countries. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:2579–2592.

- Kripalani S, Risser J, Gatti ME, et al. Development and evaluation of the adherence to refills and medications scale (ARMS) among low-Literacy patients with chronic disease. Value Health. 2009;12(1):118–123.

- Nogueira NF, Luisi N, Salazar AS, et al. PrEP awareness and use among reproductive age women in Miami, Florida. PLoS One. 2023;18(6):e0286071.

- Raifman JR, Schwartz SR, Sosnowy CD, et al. Brief report: Pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness and use among cisgender women at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;80(1):36–39.

- Scott RK, Hull SJ, Huang JC, et al. Factors associated with intention to initiate pre-exposure prophylaxis in cisgender women at high behavioral risk for HIV in Washington, DC. Arch Sex Behav. 2022;51(5):2613–2624. Jul

- Jones JT, Smith DK, Wiener J, et al. Assessment of PrEP awareness, PrEP discussion with a provider, and PrEP use by transmission risk group with an emphasis on the Southern United States. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(9):2985–2991.

- Kwakwa HA, Bessias S, Sturgis D, et al. Attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in a United States urban clinic population. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1443–1450.

- Calabrese SK, Kalwicz DA, Modrakovic D, et al. An experimental study of the effects of patient race, sexual orientation, and injection drug use on providers’ PrEP-Related clinical judgments. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(5):1393–1421.

- Bunting SR, Feinstein BA, Calabrese SK, et al. Assumptions about patients seeking PrEP: exploring the effects of patient and sexual partner race and gender identity and the moderating role of implicit racism. PLoS One. 2022;17(7):e0270861.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Core indicators for monitoring the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative (preliminary data): National HIV Surveillance System data reported through; and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) data reported through December 2022–2023. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023

- Kojima N, Davey DJ, Klausner JD. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection and new sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2016;30(14):2251–2252.

- Ayerdi Aguirrebengoa O, Vera García M, Arias Ramírez D, et al. Low use of condom and high STI incidence among men who have sex with men in PrEP programs. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0245925.

- Srikanth K, Killelea A, Strumpf A, et al. Associated costs are a barrier to HIV preexposure prophylaxis access in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(6):834–838.

- McManus KA, Fuller B, Killelea A, et al. Geographic variation in qualified health plan coverage and prior authorization requirements for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2342781.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommends long-acting cabotegravir for HIV prevention. 2022. [accessed 01 August 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-07-2022-who-recommends-long-acting-cabotegravir-for-hiv-prevention

- Fonner VA, Ridgeway K, van der Straten A, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-acting injectable cabotegravir as preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition. AIDS. 2023;37(6):957–966.

- Cole SW, Glick JL, Campoamor NB, et al. Willingness and preferences for long-acting injectable PrEP among US men who have sex with men: a discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open. 2024;14(4):e083837.

- Rogers BG, Chan PA, Sutten-Coats C, et al. Perspectives on long-acting formulations of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men who are non-adherent to daily oral PrEP in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1643.

- Kaptchuk RP, Thomas AM, Dhir AM, et al. Need for informed providers: exploring LA-PrEP access in focus groups with PrEP-indicated communities in Baltimore, MD. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):1258.

- Xiridou M, Hoornenborg E. Long-acting PrEP: new opportunities with some drawbacks. Lancet HIV. 2023;10(4):e213–e5.

- Health Information Technology (HITECH). Health Information Technology Act. 2009. [accessed 30 November, 2022]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf

- DeTora LM, Toroser D, Sykes A, et al. Good publication practice (GPP) guidelines for Company-Sponsored biomedical research: 2022 update. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(9):1298–1304. Sep