Abstract

With climbing percentages of linguistic diversity within the United States population, teachers must be prepared to work with English language learners in school and community settings. In this paper, we utilized a multiple-case study design to describe and explore the learning of four undergraduate teacher candidates enrolled in a university course on the assessment of English language learners. Working to fulfill the course and clinical requirements for the English as a Second Language endorsement, candidates engaged in fieldwork and conducted authentic language assessments to glean the unique sociocultural and linguistic backgrounds, abilities, and needs of students to inform subsequent instruction. Findings indicated that candidates benefited from diverse school and community field placements that matched their programs of study and cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Additionally, findings demonstrated the affordances of community sites where candidates had authentic and low-stakes opportunities to engage in professional practice, juxtaposed with high-stakes classroom settings where cooperating teachers often limited candidate involvement due to the focus on standardized testing. We close with implications and recommendations for field-based teacher preparation for English language learners.

Across the United States (U.S.), students in pre-Kindergarten-through-twelfth-grade (PK-12) classrooms speak hundreds of native languages other than English (Shin & Kominski, Citation2010), making schools more linguistically diverse today than ever before (Gándara & Hopkins, Citation2010). Approximately half of the 11 million students who speak a language other than English at home, students labeled as English language learners (ELLs) do not speak English well enough to be considered proficient (U.S. Department of Education, 2010). The ELL population in U.S. public schools continues to grow, climbing from 3.5 million to 5.3 million in the past decade (National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, 2012). Nevertheless, the educational institution has not kept up with the trend, as the disparities in academic achievement between ELLs and their mainstream peers continue to grow (Gándara & Hopkins, Citation2010). Central to closing this ELL achievement gap (Fry, Citation2008) is the well-prepared and effective classroom teacher – the greatest in-school factor impacting all students’ achievement (Cochran-Smith & Fries, Citation2005; Darling-Hammond, Citation2000), but particularly pertinent for the vulnerable and significant population of ELLs (Gándara & Maxwell-Jolly, Citation2006).

As the nation’s population continues to diversify linguistically (Shin & Kominski, Citation2010), teacher education programs must determine appropriate and effective ways to prepare candidates for ELLs (Gándara & Maxwell-Jolly, Citation2006). In the past decade, various professional texts on teacher preparation for ELLs (Flores, Sheets, & Clark, Citation2011; Lucas, Citation2011; Téllez & Waxman, Citation2006; Valdés, Bunch, Snow, Lee, & Matos, 2005) have provided recommendations to support university faculty and teacher educators in the plight to keep up with the changing linguistic diversity in classrooms and schools. Overwhelmingly, extant literature emphasizes university-based teacher preparation that aims to amass core knowledge centering on big ideas about language, including language variations and linguistic demands of various disciplines (Valdés et al., Citation2005), second language acquisition theory and principles (Lucas, Villegas, & Freedson-González, Citation2008), linguistics (Ann & Peng, Citation2005), and linguistic diversity (Nevarez-LaToree, Sanford-DeShields, Sounday, Leonard, & Woyshner, Citation2008). Making recommendations for pre-service teacher education housed at the university, scholars advise courses that center on language and linguistics specifically (Ann & Peng, Citation2005; Valdés et al., Citation2005), as well as integration of language themes woven throughout curricular strands of teacher education programs (Lucas et al., Citation2008; Valdés et al., Citation2005). Whereas application in field-based settings may be implied, the ELL teacher preparation literature primarily focuses on core knowledge for teaching.

Research supporting clinically-based teacher education has predominantly focused on fieldwork to prepare candidates for cultural diversity. By way of practice-based approaches to learning through structured experiences in and with schools and communities with diverse populations (Ball & Cohen, Citation1999; Murrell, Citation2000; Zeichner, Citation2006), candidates develop personally and professionally and build understanding of and dedication to culturally diverse settings (McDonald et al., Citation2011; Zeichner, Citation2006). Past studies of field-based teacher preparation has demonstrated that candidates: (a) engage with social justice issues (Murrell, Citation2000), (b) deconstruct stereotypes and assumptions about low-income and diverse communities (McDonald et al., Citation2011; Onore & Gildin, Citation2010), (c) recognize the resources in homes and communities (Burant & Kirby, Citation2002; McDonald et al, Citation2011), and (d) learn about the value of informal, community-based learning experiences (Onore & Gildin, Citation2010). To arrive at these understandings, two necessities emerge in preparing teachers in school and community settings, including the need to provide authentic experiences with teaching and learning aligned with the diverse communities where they will teach (Murrell, Citation2000) and cultivating practice in low-risk settings before entering high-stakes classroom settings (Ball & Cohen, Citation1999). Cultural diversity takes center stage in the field-based teacher preparation literature, and language is a key component of one’s culture (Lucas et al., Citation2008).

This paper merges these two central fields of research – ELL teacher preparation and field-based teacher education – to fill a gap in the literature by exploring teacher learning related to ELLs that is embedded in experiences with linguistically diverse children and adults in schools and communities. Different from past studies that bridge the two fields (Bollin, Citation2007; Mercado & Brochin-Ceballos, Citation2011), we expand beyond Spanish-speaking ELL children to represent the cultural, linguistic, and age diversity in our urban Midwestern region. Building on recommendations of both scholars (García, Arias, Harris-Murri, & Serna, Citation2010) and organizations (American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education, AACTE, Citation2010; National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education, NCATE, 2010), we recognize the central role of clinical experiences with ELLs to develop teacher candidates’ understandings about language described in the ELL teacher preparation literature (Ann & Peng, Citation2005; Lucas et al., Citation2008; Nevarez-LaToree et al., Citation2008; Valdés et al., Citation2005). In this study, we investigate the impact of moving off the university campus to build candidates’ knowledge and skills through fieldwork with ELLs in schools and community organizations.

To provide high-quality instruction for all students, candidates must have opportunities to practice teaching in diverse settings that encourage them to connect with and understand the diversity and experiences of students, both within and outside of school (Banks et al., Citation2007; Ladson-Billings, Citation2000). These opportunities are essential for candidates seeking certification or endorsements to teach ELLs (García et al., Citation2010; McDonald et al., Citation2011). Therefore, a central component of any culturally and linguistically responsive teacher education program (Lucas et al., Citation2008) should be clinical experiences to apprentice candidates into teaching in diverse settings and valuing students’ unique backgrounds and funds of knowledge (Moll & Gonzalez, Citation1997). Field-based experiences have the potential to provide candidates with authentic opportunities to develop practice, beyond activities such as lesson planning and peer teaching that typically occur in the university setting (Grossman, Hammerness, & McDonald, Citation2009b); however, for this development to occur, teacher educators must (a) select sites that offer opportunities to practice course content in a meaningful way, and (b) integrate field work with university coursework to be interdependent (Cochran-Smith, Davis, & Fries, Citation2004; Goodwin, Citation1997; Hollins & Torres-Guzman, Citation2005).

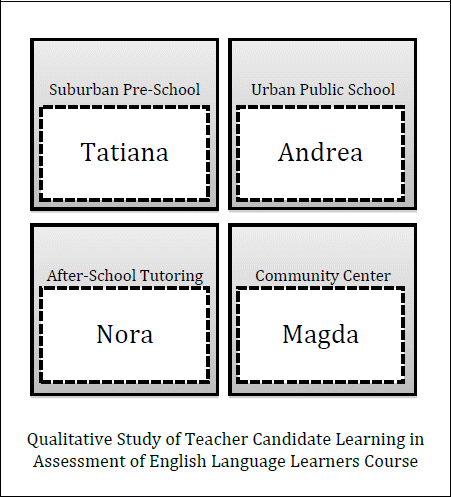

In this paper, we explore teacher candidates’ learning about ELLs through clinical experiences in an undergraduate course entitled Assessment of English Language Learners. After framing the study in sociocultural theory and the conceptual framework for teaching practice (Grossman et al., Citation2009a), we outline the multiple-case study design (Yin, Citation2009) utilized to explore the clinical experiences of teacher candidates in four distinct field sites: a bilingual public school classroom, a suburban pre-school classroom, an after-school tutoring program at a charter school, and English classes for adult immigrants at an urban community organization. Presented as descriptive and explanatory case findings, we investigate how these sites shaped the experiences of the teacher candidates and how each site provided unique affordances. Finally, we close with discussion and implications for field-based teacher preparation for ELLs in schools and communities.

Preparation for Professional Practice with English Language Learners

The sociocultural paradigm (Rogoff, Citation2003) frames the construction of knowledge as social and cultural in nature, in which learning is understood as a change in participation on multiple planes of social and cultural activity. Rather than supposing a passive individual controlled by the surrounding world or an active individual who takes charge of cognitive development, we frame our work to recognize learning as the collaboration between an active individual and active social environment (Berk & Winsler, Citation1995). Additionally, sociocultural theory takes into account the biological and social nature of learning that allows for the use of higher-level thinking with more-advanced peers, which facilitates the development of an individual (Vygotsky, Citation1978). As cultural processes both define and are defined by individuals, an individual’s development and learning “must be understood in, and cannot be separated from, its social and cultural-historical context” (Rogoff, Citation2003, p. 50). Applied to the study of professional preparation, we perceive teacher candidates as actively involved in their own learning, simultaneously impacting and impacted by social interaction with others and the specific settings where learning occurs (Grossman et al., Citation2009a).

We specifically utilize the conceptual framework for teaching practice (Grossman et al., Citation2009a), which operationalizes theories related to sociocultural (Rogoff, Citation2003; Vygotsky, Citation1978) and experiential teacher learning (Dewey, Citation1965; Ericsson, Citation2002) to guide preparation for professional practice. Within this framework, three interrelated concepts emerge to support understanding and investigation of teacher preparation: (a) representations of practice, (b) decompositions of practice, and (c) approximations of practice. Representations of practice allow novices to passively survey and understand professional practice, such as observing teachers or reading vignettes about classroom events (Grossman et al., Citation2009a). Decompositions of practice refer to the breaking down of actions of educators to discuss and make meaning of the smaller elements that make up the complexities of the professional practice as a whole (Grossman et al., Citation2009a). In this way, candidates observe and discuss the pertinent practice of professionals engaged in teaching and learning.

While representations and decompositions of teaching are essential to the learning process, candidates must also engage in approximations of practice, which entail practice of a particular aspect of teaching (Grossman et al., Citation2009a). Approximations of practice vary greatly in their degree of authenticity. Authenticity refers to how closely the setting approximates the context in which candidates will do the work of teaching upon graduation. Less authentic approximations of practice highlight fewer facets of a practice, require narrow participation by the teacher candidate, and offer greater opportunity for rehearsal. Authentic approximations offer more complete representations of practice, fuller participation by the teacher candidate, and fewer “stops and starts” (Grossman et al., Citation2009a, p. 2079). While an activity such as peer teaching with coaching, in which the teacher educator frequently pauses the lesson to offer feedback, may lie at the less authentic end of a continuum of authenticity, an activity such as teaching a lesson in the PK-12 setting lies at the more authentic end. Although less authentic approximations within the university classroom are appropriate early in a teacher preparation program, candidates must engage in more authentic approximations as they progress through the program.

In this study, we utilize this three-facet conceptual scheme of preparation for professional practice, specifically focused on the authenticity and affordances provided by approximations of practice (Grossman et al., Citation2009a), to respond to the following three research questions: (a) How did the various field sites shape each teacher candidate’s experience? (b) What are the benefits of utilizing various field sites (e.g., public schools, community organizations) to support teacher candidates’ learning related to ELLs?, and (c) To what extent did the degree of authenticity and autonomy vary across the field sites? In the next section, we share the holistic multiple-case study design and qualitative methods of data collection and analysis to support the investigation of field-based professional preparation of teachers for practice with ELLs.

Methods

Context

Situated in the urban hub of the Midwest, we conducted this study with teacher candidates enrolled in English as a Second Language (ESL) endorsement coursework in the School of Education at a private university. The third largest metropolitan area in the U.S., the city of Chicago and the many suburbs in northeastern Illinois are home to approximately 2.5 million residents who speak a non-English language in the home (Ruiz & Koch, Citation2011; Shin & Kominski, Citation2010). Reflecting the culturally and linguistically diverse population, students labeled as ELLs bring approximately 136 different language backgrounds to Chicago urban and suburban classrooms (Ruiz & Koch, Citation2011). Aiming to prepare future teachers for diverse classrooms and communities, candidates enrolled in the five teacher preparation strands had the option to add the ESL endorsement, requiring six additional university courses and 100 clinical hours with ELLs.

[Insert Tables 1 & 2 around here.]

Situated in the Assessment of ELLs course at the end of the ESL endorsement sequence, candidates entered with knowledge and skills related to linguistics, second language acquisition, language policies and programs, and culturally responsive teaching; most candidates enrolled simultaneously in ELL methods offered during the same semester. The course consisted of both university-based instruction and clinical experiences, completing 15 hours of field-work toward the larger 100 hours required for the endorsement. Aiming to explicitly connect the university and field components, the authors designed the core assignments, the ELL assessment portfolio and case study, to be centered on the field-based work with ELLs. In the assessment portfolio, candidates worked one-on-one with an ELL student to design, conduct, and analyze authentic assessments of students’ (a) funds of knowledge, (b) oral language development, (c) writing language development, and (d) reading language development (Moll & Gonzalez, 1997; Tinajero & Hurley, Citation2001). For each assessment, candidates maintained private Google websites which included: (a) assessment description, (b) assessment rationale, (c) data collection methods and analysis, and (d) reflection. Candidates then composed a case study paper to thickly describe the students’ assets, abilities, and needs to suggest instructional methods and accommodations based on findings.

Design

Seeking to understand teacher learning in field-based settings, we conducted a larger qualitative study (Erickson, Citation1986) with the 24 consenting candidates enrolled in the authors’ two course sections in the spring semester of 2012. To better understand the data from the larger study, we opted to utilize a multiple-case study design (Yin, Citation2009) to explore the experiences and learning of individual candidates.

[Insert Figure 1 around here.]

Using purposive sampling (Merriam, Citation1998), we selected four participants based on field-site setting, academic degree program, and completion of all data sets. First, to have a sample that allowed investigation of the research questions in various settings of school- and community-based fieldwork, we selected teacher candidates from four field-sites: (a) bilingual public school, (b) suburban pre-school, (c) urban after-school tutoring program at a charter school, and (d) urban community center. We had strategically placed candidates at field sites before the semester began, based on their program of study. These sites represented both purposive sampling and a sample of convenience because we fostered relationships with volunteer coordinators at the sites. Second, we purposively selected candidates to represent of the four program strands reflected in the course: (a) early childhood special education, (b) bilingual education, (c) elementary education, and (d) secondary education. Finally, to ensure ample data related to each research question, we narrowed options by including candidates who had completed the data sets described below.

[Insert Table 3 around here.]

Data Collection

Requiring multiple sources of evidence to study cases and triangulate findings, we collected three types of data to explore our research questions: surveys, artifacts and documentation, and participant observation (Yin, Citation2009).

Surveys. We utilized a standard tool to survey all candidates before and after the school-and community-based fieldwork. Before the start of fieldwork, candidates completed an initial survey which asked about their cultural, linguistic, and professional background and probed for their existing conceptualizations of working with ELLs. Following completion of fieldwork, we asked similar questions in an exit survey, but also asked for reflection on course and fieldwork experiences. These open-ended questions permitted us to map candidate learning to the field site as well as to determine how the various field sites shaped candidates’ conceptualizations of working with ELLs.

Artifacts and documentation. We collected artifacts and documentation from candidates’ work with ELLs through two assignments: (a) assessment portfolios and (b) case study papers. Compiled in the electronic format of a private Google website, portfolios contained artifacts from authentic language assessments, including explanations, reflections, and supplemental materials such as transcriptions, pictures, texts, rubrics, and tools. As the culminating assessment, case study papers served as the documentation data source, in which candidates suggested instructional methods to build on students’ funds of knowledge and target specific areas of language need. These data, matched to the survey data, created a more complete picture of teacher candidate learning as related to each field site.

Participant observation. Whereas the primary data collection through surveys, artifacts, and documentation supported our understanding of individual teacher candidates’ learning in field-based experiences at schools and community organizations, we also wanted to capture candidates’ collaborative learning with one another in course sessions. As a part of this larger qualitative study of teacher candidates in the Assessment of ELLs course, we each collected anecdotal data and reflections on course discussions and teacher candidate learning. We each maintained our observational notes and reflections on our own and used the data as a secondary source to support our understanding of how the candidates’ experiences at school sites impacted the dialog at the university.

Data Analysis

Within the multiple-case study design, we approached the data with the general strategy of case descriptions and the analytic technique of explanation building (Yin, Citation2009). We began with case descriptions, individually conducting and collaboratively triangulating our iterative analyses (Erickson, Citation1986) of the multiple sources of data to deeply understand and thickly describe the case of each teacher candidate. After analyzing each individual case, we then utilized thematic analysis (Erickson, Citation1986) to identify, code, and explain the holistic set of data to respond to the research questions. To engage in this explanatory approach to pattern building across multiple cases (Yin, Citation2009), we each individually wrote assertions based on the thematic analyses, and after testing the assertions with multiple reads of the data, we met and shared themes, assertions, and explanations. We reached consensus through discussion of any varying points of understanding (Maxwell, Citation1996) and through re-examination of data sources.

Trustworthiness

Seeking to maximize the trustworthiness of the larger qualitative study and the multiple-case study of four candidates, we consistently engaged in triangulation of data, evaluation, and theory (Yin, Citation2009). First, we specifically sought multiple sources of data to triangulate findings across surveys, artifacts, documents, and observations. Second, we utilized investigator triangulation by comparing and discussing our individual analyses. Third, we consistently returned to our theoretical and conceptual frameworks to ensure theory triangulation, approaching the data set with the specific perspectives of sociocultural learning (Rogoff, Citation2003) and preparation for professional practice (Grossman et al., Citation2009a). In addition to the three-faceted scheme of triangulation between authors, we also utilized graduate assistants to support our maintenance of an evidentiary database (Yin, Citation2009) and confirm findings from outsider perspectives, specifically due to our dual roles as researchers and instructors.

Findings

Case Descriptions of Teacher Candidates

In this first sub-section of the findings, we share case descriptions (Yin, Citation2009) of four teacher candidates to respond to the first research question: How did the various field sites shape each teacher candidate’s experience? For each case, we draw from (a) initial survey data to provide background information and details on cultural, linguistic, and professional backgrounds, (b) artifacts and documentation to describe experiences in the field site, and (c) exit survey data to explore perceptions and reflections on the field-based work with ELLs.

Tatiana: Young language learners at a suburban pre-school. Tatiana grew up speaking Romanian and learned English as a second language when she started school in the U.S. As a junior in the Early Childhood Special Education program, her program advisor placed Tatiana for 10 weeks of student teaching at Growing Stars, a pre-school in a wealthy northern suburb of Chicago. With the majority of the four-year-old students in her classroom speaking English as their native language, Tatiana selected Sean as her case study student – one of two ELLs in the inclusive pre-school classroom. Tatiana reported that Sean’s family, including parents, grandparents, and an older sister, came to the Chicago suburbs from India and spoke primarily Gujarati in the home.

Tatiana was simultaneously completing an additional 35 clinical hours within this pre-school for another course, and therefore had substantial time to learn from her cooperating teacher. Her portfolio and case study reflected this extended opportunity for practice, demonstrating seamless integration across assessments. In her portfolio of Sean, Tatiana utilized findings from early assessments to inform the design of those later in the semester. She frequently applied her arsenal of knowledge on child development and early childhood education, such as seeking out early-childhood-specific rubrics for various language assessments, to be able to aptly analyze the data and capture the first and second language development of her four-year old student.

In reflecting on her experiences working with Sean and other students in the inclusive pre-school setting, Tatiana recognized the importance of social and emotional facets when assessing the language proficiency of young children, as she gained a more accurate and holistic picture of Sean’s language when engaged in authentic, comfortable, and motivating tasks and assessments. Additionally, Tatiana perceived the assessment portfolio and case study with an ELL student in an extended field-based placement as central to her understanding of English language development, referencing how she observed Sean’s linguistic abilities transfer across the four domains of language and impact both social and academic language use in informal and formal classroom settings.

Andrea: Bilingual Latinos at an urban public school. An English native speaker and lifetime resident of the Midwest U.S., Andrea learned Spanish as a second language through high school and university language courses, paired with travels to Mexico for service work and Chile for study abroad. A junior majoring in Bilingual/Bicultural Education and minoring in Reading, Andrea completed her clinical hours at Washington, a K-8 urban public school with approximately 84% Latino and 22% ELLs in transitional bilingual, maintenance bilingual, and sheltered instruction classrooms. For her case study, she worked with Maria, an eight-year-old third grader, the daughter of Mexican immigrants and a native Spanish speaker who preferred to think and speak in her native language both at home and school.

Placed in a context that matched her bilingual concentration, Andrea utilized her prior knowledge to evaluate language use in the classroom. She prefaced the portfolio by explicitly sharing that the class was taught almost entirely in English and students displayed a wide range of Spanish language and literacy abilities, despite the label of being a maintenance bilingual classroom. Through Andrea’s individualized work with Maria, she communicated in Spanish in the initial stages of building rapport and getting to know her background, interests, and funds of knowledge. Nevertheless, perhaps due to the overwhelming use of English in the classroom, Andrea utilized English-medium assessments of the four domains of language, rather than using her own bilingualism to assess Maria’s oral language, reading, and writing in Spanish. Drawing from knowledge and skills gleaned in courses from her reading minor, the literacy assessments included analyses of miscues, including transfer errors between Spanish and English.

Andrea reflected on her experiences at Washington and perceptions of the field-based work with Maria. She expressed the value of authentic assessments to measure language proficiency and guide effective instruction for ELLs, specifically recognizing the interconnectedness of the four domains of language. Perhaps because it was the only assessment conducted in her native language, Andrea found that the funds of knowledge assessment provided the most valuable information to get to know Maria as a learner, as well as to build linguistic assessments tailored to her funds of knowledge and English language proficiency. Because of her placement at a public school with many initiatives and demands related to standardized testing, Andrea also expressed that she experienced constraints in finding one-on-one assessment and instruction time, as her cooperating teacher asked that she not work with Maria individually. In this way, she engaged frequently in informal observations during whole-class time and applied her findings to maximize the authenticity and language support provided during the one-on-one time with Maria.

Nora: Linguistically diverse students at an after-school tutoring program. Nora grew up in the suburbs of Chicago and attended public schools with a mostly homogenous English speaking population. She was monolingual and, as one of few sophomores in the class, reported little experience working with ELLs on the survey at the start of the semester. Because she was studying to be an elementary teacher with an ESL endorsement, we placed Nora at Gateway Charter School, an urban charter school with free after-school tutoring for refugee and immigrant students from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Her responsibilities included tutoring three students on a weekly basis, one of whom she selected as her case study student. This student, Sunita, was a nine-year-old, native Nepalese speaking ELL student in fourth grade who had recently immigrated to Chicago with her family from Nepal just eight months prior.

The assessment portfolio and case study artifacts highlighted Nora’s learning through her field-based experiences with Sunita. Working with a beginning ELL, Nora found that the one-on-one time allowed her to find creative methods to access the ideas, stories, and expression that Sunita could not always get across in her productive oral language. Without collaboration with the classroom teacher to glean specific abilities and needs related to English language proficiency, Nora described the need to be flexible in her approach to the authentic assessments of language, often needed to gauge Sunita’s understanding and change her questions and prompts accordingly. These authentic language experiences led this monolingual teacher candidate to learn about strategies used by ELLs, such as the circumlocution that Sunita used to describe a turtle as the “big green animal with spots.”

Reflecting on the field-based experience at Gateway, Nora described the value of working with a small-group of students in the flexible after-school tutoring setting, which reassured her that she could succeed as a future teacher. Assigned a tutoring role with three students, Nora gradually became accustomed to the school environment and felt a sense of freedom to implement methods and assessments learned in class at her own pace. Nevertheless, whereas the lack of a prescribed curriculum or textbook supported her freedom in implementing assessments and corresponding instruction, Nora perceived the absence of a cooperating teacher as detrimental to discerning Sunita’s language and academic proficiencies and needs as determined by standardized tests and general classroom practice; however, scheduling was straightforward within this program, which permitted Nora to visit the after-school program once a week throughout the semester. As a result, she applied her knowledge and skills immediately after deconstructing the practice during class, which she found beneficial considering the substantial time that it took to design, implement, and analyze authentic language assessments.

Magda: Adult learners at an immigrant community center. Magda’s parents immigrated to Chicago from Iraq before she was born. Although she grew up speaking only Assyrian with her parents, she was bilingual after acquiring English at an early age. Magda was a junior working toward certification as a secondary History teacher with an ESL endorsement. For the clinical component of the course, we placed Magda at the City Center Organization (CCO), a community center that offered many free services, including multi-leveled ESL classes, to a diverse adult immigrant community. Thrilled that Magda spoke Assyrian, the coordinator immediately assigned Magda to one-on-one tutoring with Zahra, an Iraqi refugee who, despite repeated attempts at learning English, was not progressing in her English language development.

Magda’s assessment portfolio and case study paper explored her various experiences working with Zahra, an older woman with various health ailments who had moved to Chicago four years prior to escape the war and violence in Iraq. First conducting the funds of knowledge assessment in their common language of Assyrian, Magda was able to glean ample information and vivid stories about Zahra’s life and experiences learning English in the U.S, leading to her realization of social and emotional challenges faced by refugees and adult ELLs. Whereas Magda only planned to use Assyrian for the informal dialog, she was surprised to find the efficacy of native language scaffolds in the authentic language tasks, particularly the vocabulary support in the oral language and reading assessments. Through the field-based work that supported the holistic picture of Zahra’s abilities, including her multilingual proficiencies in Assyrian and Arabic, Magda was troubled that CCO enforced English-only and insisted that Zahra repeat Level 1 ESL class numerous times.

In reflecting on her experiences at CCO, Magda shared her increased level of confidence not previously experienced as a teacher candidate. CCO employees viewed Magda as an expert because not only did she speak Assyrian, but she was also a university student pursuing an ESL endorsement. As an organization maintained almost entirely by volunteers, most without degrees in education or ESL, they relied on outdated, photocopied curriculum to guide English language teaching and learning. With guidance from the volunteer coordinator eager to learn from teacher candidates, specifically expressing the desire to view and utilize results of the proficiency assessments for program articulation, Magda embraced a leadership role. Through the field-based experience, she became deeply invested in the organization beyond the scope of the course, as well as in the progress of her case study student, and continued to volunteer at CCO teaching adult ESL classes.

Trends and Comparisons across Field Sites

The case studies of four teacher candidates revealed how the various field sites impacted their learning about assessment and instruction with ELLs. In this second sub-section of the findings, we utilize explanation building (Yin, Citation2009) to respond to the second research question: What are the benefits of utilizing various field sites to support teacher candidates’ learning related to ELLs? We present one representative case to support each assertion, drawing upon that candidate’s survey responses, artifacts, and documentation as multiple sources of evidence.

The use of four field sites for the clinical experiences confirmed the critical importance of matching teacher candidates with an appropriate clinical setting and case study student. Because teacher candidates had the option to add the ESL endorsement on to any academic major (i.e., early childhood special education, bilingual, elementary, secondary), we had candidates from various areas of concentration in our course sections, as well as a variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Directly connected to our aim of developing the knowledge and skills of all teacher candidates within their area of expertise, we discovered that learning about ELLs occurred when (a) field experiences for this course matched their eventual teaching certification, such as Tatiana at a pre-school and Andrea at a bilingual school, and (b) the candidates selected a case study student to whom they could provide primary language support, such as Andrea’s selection of a Spanish-speaking child and Magda’s partnership with an Assyrian-speaking adult.

[Insert Table 4 around here.]

Matching candidates with settings. To illustrate this finding of matching field site with areas of expertise, we explore the case of Tatiana, an early childhood candidate seeking her ESL endorsement, who was placed in a suburban pre-school. With candidates spanning expertise in PK-12, we utilized texts and related resources (Gottlieb, Citation2006; O’Malley & Pierce, Citation1996) that explored second language acquisition and development across age groups. While engaging in the design of authentic assessments and rubrics for her case study of a Gujarati-speaking pre-school student, Tatiana drew from both the ESL-specific assessment literature and early childhood resources to accurately collect and analyze data. She utilized five rubrics (i.e., English language acquisition, emergent speaking, pre-school literacy, emergent writing, and writing name) from the pre-school curriculum at the school, in addition to ELL-specific rubrics from the course text (O’Malley & Pierce, Citation1996) and Pre-Kindergarten and Kindergarten English language proficiency rubrics. For example, on the reading assessment sub-page of her Google site, she reflected:

It was hard to use the ESL rubric to gain a good understanding of where he is in terms of ESL progression because he is still at the pre-reader stage because of his age and developmental level. Using the school’s curriculum helped me make more informed analysis about where his reading level is appropriate to his age.

Tatiana went on to explore these findings in her case study paper at the end of the semester, specifically stating how she used both ESL and pre-school rubrics to better understand her student’s literacy abilities and inform her instructional suggestions related to reading.

Just as she utilized her prior knowledge of child development to inform her individualized work with one ELL, the ELL-specific approach from the course better informed her knowledge and skills as an early childhood educator. In addition to utilizing multiple resources to analyze data, she learned the importance of drawing from multiple sources when collecting data on young ELLs. In her summative survey, she shared:

[This course] has given me the experience of conducting assessments on an actual student, which helped me realize how important it is for the assessments to be authentic, comfortable, and motivating for the student in order to more accurately show their abilities. Although in some assessments, the student produced shorter phrases and one-word answers, I know through informal observations that this student produced longer phrases.

Completing her field work within a site carefully matched to her career aspirations enabled Tatiana to engage in approximations of practice, thereby applying knowledge constructed from the university setting.

Matching candidates with students. Partnering with various field sites permitted candidates to utilize their own cultural and linguistic resources to inform the assessment and instruction of selected ELLs. Conducting her clinical work at an immigrant organization in a diverse Chicago neighborhood, Magda worked one-on-one with an Iraqi refugee with whom she shared the Assyrian language. We found that Magda utilized shared linguistic repertoires with her case study student, Zahra, using Assyrian to scaffold directions during assessments when the adult ESL student did not understand the expectations in English. Because of the linguistic connection with the student, Magda saw the direct impact that she had on the adult ESL student’s language learning. In her summative survey, Magda reflected on the experience at the community organization:

Working with students that had trouble with English and being able to provide students, like Zahra, with help they never had before was great. My Assyrian was put to good use! I think you should place everyone at CCO… I gained the most experience working with students … that need the most help in learning the language.

Seeing how Zahra’s English language learning responded to her linguistic scaffolding with Assyrian, Magda made specific instructional recommendations for native language use in her final case study paper, stating the need for “support in her first language” and “individualized attention with a fellow Assyrian speaker to really begin to grasp language and become literate.” In addition to the Assyrian language link, Magda benefited from the autonomy to engage in language teaching and learning afforded by the community organization, which we discuss in the next sub-section.

In sum, as demonstrated through the cases of Tatiana and Magda, utilizing a variety of field sites permitted teacher candidates to synthesize and apply both past and present learning. Tatiana synthesized her knowledge of early childhood development with her knowledge of working with ELLs for her assessment portfolio and case study of Sean. Magda utilized shared linguistic backgrounds and repertoires with Zahra to build rapport and support language learning. Across all cases, learning from the course merged with candidates’ prior knowledge from other education courses and experiences with language and bilingualism. When candidates’ field sites matched prior knowledge and experiences, they built on existing knowledge to make meaning of concepts specifically related to ELL teaching and learning, such as funds of knowledge (Moll & Gonzalez, 1997), affective filter, and comprehensible input (Krashen, Citation1987).

Degrees of Authenticity and Autonomy

In the third sub-section of the findings, we respond to the third research question: To what extent did the degree of authenticity and autonomy vary across the field sites? To answer this research question, we draw primarily from the representative cases of Andrea and Nora, while also referring back to those of Tatiana and Magda. These cases provide evidence that the degree to which each teacher candidate was able to approximate the practices learned within the university setting varied according to the field sites.

Traditional school settings more closely familiarized candidates with their future roles and responsibilities as teachers. For example, Tatiana and Andrea observed how classroom teachers followed curriculum, set learning objectives, and participated in the culture of testing within the school. Unlike Nora and Magda, they worked closely with cooperating teachers who served as sources of expertise and provided necessary supports and information to candidates. In this way, candidates placed in public school classrooms had experiences that, in many ways, were more authentic than the experiences of candidates placed in community organizations or after-school programs. We first draw upon the case of Andrea to illustrate our meaning.

Spending time within the urban public school of Washington Elementary, Andrea consistently engaged with students, observed teacher and parent interactions, and became familiar with daily school procedures. In artifacts and documentation, her field work in an authentic school environment provided firsthand experiences with ELLs in today’s classrooms. Andrea recognized the centrality of standardized test preparation and drew upon those test questions to design her assessments. For example, when designing the writing assessment, her cooperating teacher helped her to select a writing prompt based on an informational text that she planned to use for test preparation. Additionally, Andrea aligned assessments with what students were doing related to the Common Core Standards; however, Andrea’s descriptions of student behavior illustrated that she was mostly observing these practices. She observed avoidance techniques used Maria, illustrated by her description of reading time when she chose a book “five levels higher than her reading level,” “staring at the same page for a long time,” and strategically got up to throw things away or drink from the water fountain. Overall, Andrea noted having little autonomy, describing the reluctance of her cooperating teacher to allow her to work individually with Maria. The teacher was worried that Maria might miss an important lesson that would impact her performance on mandated standardized tests. As a result, when not conducting assessments for the portfolio, Andrea’s role was mostly that of an observer who sat in the back of the classroom.

The experiences of Nora, placed in the after-school program at Gateway Charter School, stood in contrast to that of Andrea. In some ways, her field-based experiences were not as authentic as those of Andrea. She worked with a group of three students, assisting with homework and designing lessons that she felt targeted the students’ language abilities and needs. Nora did not have the opportunity to collaborate with a certified teacher, consult curriculum guides, or learn about teacher and parent interactions. When describing her first days at Gateway, Nora reported, “Because I visit Sunita during the afterschool program, I had no idea what her language proficiency was.” Nora felt that this isolated context hindered her ability to appropriately administer language assessments. She reflected, “If it was in a classroom setting I think it could have been much more relevant and more accurate. I would have been able to relate it to what Sunita was learning and she might have felt more comfortable completing it during the school day.”

Nevertheless, while Nora may not have been exposed to authentic classroom activities and routines like Andrea, her work at Gateway was far along the continuum of autonomy. Her level of involvement more closely approximated that of a school teacher. Whereas Andrea spent substantial amounts of time engaged in observation, Nora was given teaching responsibilities from her first day in the after-school program. She quickly had to discern how to organize instruction, create appropriate assessments, and manage discipline problems. Nora described, “I loved Gateway Charter School, and I really liked the students I worked with. They were all open to learning and succeeding and it gave me reassurance that I could succeed as a future teacher.” The independence that this setting afforded increased Nora’s confidence that she could succeed as a teacher.

In sum, the varying degrees of authenticity and autonomy reported by Andrea and Nora were not unique to them, but also generalized to the group of candidates as a whole. In addition to the difficulty in securing public school field placements, the case of Andrea revealed that those candidates who gain access often have lower levels of autonomy than those placed in settings not restricted by testing. Across the four cases presented here, Nora and Magda, as well as the other candidates placed at CCO and Gateway, had the freedom to simultaneously try the assessments and methods learned in the university setting within field sites. They designed assessments and lessons, often sharing results and products with leaders at organizations. Conversely, candidates placed at public schools gained other valuable information about school-based policies and procedures, but had less autonomy to practice the instructional and assessment methods. Candidates benefited from the varying affordances of field sites and brought new, practical knowledge back to the university classroom. As each candidate shared her experiences through stories, vignettes, and artifacts, all candidates collaboratively constructed knowledge around the teaching and learning of ELLs.

Discussion

As classrooms and schools across the U.S. become more diverse, effective pre-service teacher preparation must include field-work with ELLs that is both strategic and purposeful to the development of linguitsically responsive knowledge and skills (García et al., Citation2010; Lucas et al., Citation2008). In this study, we explored how utilizing a variety of school- and community-based field sites impacted teacher candidates’ learning and experiences about ELLs in a culturally and linguistically diverse urban setting. Overall, through the focused exploration of four representative cases across diverse field placements, we found that teacher candidates developed knowledge and skills specific to ELLs through strategic matching of field site to candidates’ areas of concentration and of case study students to candidates’ cultural and linguistic background. Additionally, we discovered that school and community sites provided distinct affordances with varying degrees of authenticity and autonomy as candidates engaged in approximations of practice (Grossman et al., Citation2009a). In this section, we close with discussion of and conculsions on findings related to the three research questions, followed by implications and recommendations for practice.

Findings from the first research question (i.e., How did the various field sites shape each teacher candidate’s experience?) revealed the rich diversity in participants’ experiences across programs, field placements, and case study students. In this study, candidates engaged in preparation for professional practice through the design, implementation, and analysis of authentic language assessment (O’Malley & Pierce, Citation1996), as well as the application of learning to make instructional recommendations through data-based decision making (Solano-Flores & Soltero-González, Citation2011). The combination of field sites, including a suburban pre-school, urban public school, after-school tutoring program, and immigrant community organization, enriched the individual and overall experiences of candidates enrolled in the ELL-focused course. Mediated by the authentic language assessments, the variance of clinical placements supported work with and exploration of the rich diversity of children and adults often usurped into the homogenous label of ELL (Gándara & Hopkins, Citation2010; Heineke, Coleman, Ferrell, & Kersemeier, Citation2012; Wrigley, Citation2000). As candidates collaborated both with case study students and one another, they learned about working with speakers of multiple languages (e.g., Gujarati, Nepali, Assyrian) and ELL students ranging from pre-school to adulthood.

Building on the cases of individual candidates, findings from the second research question (i.e., What are the benefits of utilizing various field sites to support teacher candidates’ learning related to ELLs?) pointed to specific facets in the strategic placement of candidates in field sites. With placements across a variety of field sites, we found that candidates: (a) engaged in meaningful and authentic approximations of practice (Grossman et al., Citation2009a) in educational contexts that typically matched their specific areas of concentration (e.g., early childhood, bilingual) and (b) embraced the freedom to work with multiple ELLs and select one particular ELL to assess, often based on linguistic background (e.g., Andrea’s Spanish, Magda’s Assyrian). With candidates developing as teaching professionals, they utilized opportunities to approximate practice in settings aligned to their areas of expertise and future placements as classroom teachers (Ball & Cohen, Citation1999; Grossman et al., Citation2009a; Murrell, Citation2000); therefore, whereas community fieldwork with immigrant adults was valuable for Magda as a future secondary teacher, the pre-school setting proved pertinent for Tatiana to fine-tune the support of second language learning with young children.

Findings from the first and second research questions established new and important considerations for field-based teacher preparation. Building on other scholars’ recognition of the importance of opportunities to practice components of teaching in safe spaces (Ball & Forzani, Citation2009; Ball, Sleep, Boerst, & Bass, Citation2009; Grossman & McDonald, Citation2008), our study extended beyond general teaching to include the unique and important lens on language and ELLs (García et al., Citation2010; Lucas et al., Citation2008; Valdés et al., Citation2005). Past studies have demonstrated the value of field experiences to prepare teachers for ELLs (Bollin, Citation2007; Mercado & Brochin-Ceballos, Citation2011), focusing on (a) the general value for all candidates and (b) clinical work with Spanish-speaking ELLs. In this way, our findings are significant in demonstrating particular factors that impact teacher learning. Whereas the general integration of fieldwork has been demonsrated to be valuable for preparing teachers for ELLs (Bollin, Citation2007; Mercado & Brochin-Ceballos, Citation2011), the specific attention to matching candidates with culturally, linguistically, and developmentally diverse placements and students further enhances candidates’ professional development and expertise in language, linguistics, and ELL assessment (Lucas et al., Citation2008; Valdés et al., Citation2005; Solano-Flores & Soltero-González, Citation2011).

Results from the third and final research question (i.e., To what extent did the degree of authenticity and autonomy vary across the field sites?) demonstrated the affordances of particular field sites for candidates to approximate practice by synthesizing and applying pertinent knowledge, skills, and dispositions for the teaching profession that cannot be developed in the university classrooms alone (Grossman et al., Citation2009a; Zeichner, Citation2006). Nevertheless, as demonstrated by the case of Andrea, candidates in public schools may not have the autonomy to engage in approximations of practice in the classroom with ELLs. With many public school districts adopting evaluation models in which teacher merit is determined by students’ standardized test scores (Finnigan & Gross, Citation2007; Onosko, Citation2011), teachers like those at Washington Elementary may demonstrate reluctance to relinquish control of classroom teaching and dedicate ample time to candidates both inside and outside of the classroom. In this way, community field sites can offer lower stakes spaces for candidates to begin to practice teaching (Buchanan, Baldwin, & Rudisill, Citation2012; Burant & Kirby, Citation2002; Lee, Eckrich, Lackey, & Showalter, Citation2010; McDonald et al., Citation2011; Troyan, Davin, & Donato, Citation2013). As our findings demonstrated, specifically in the settings of Gateway’s after-school tutoring and CCO’s adult ESL classes, community organizations are alternatives that offer, among other characteristics, a less threatening space to approximate practice with ELLs, insofar as the funding is often grant-based and is not dependent upon test scores.

Significant for teacher educators considering field-based approaches to teacher preparation for ELLs, findings from the third research question contribute new insight into the use of community settings for linguistically responsive teacher education (Lucas et al., Citation2008). Extant literature has demonstrated the efficacy of community field placements to support teacher candidates’ learning about cultural diversity (Murrell, Citation2000; Sleeter, Citation2008), as well as social justice and advocacy (Baldwin, Buchanan, & Rudisill, Citation2007; Sleeter, Torres, & Laughlin, Citation2004; Wade, Citation2000). Nevertheless, community-based field sites are rarely considered as locales to prepare teacher candidates to work with ELLs, as research has focused primarily on school-based clinical placements to prepare teachers for the large number of Spanish-speaking ELLs (Bollin, Citation2007; Mercado & Brochin-Ceballos, Citation2011). Specifically demonstrated by the experiences and perceptions of Nora and Magda, non-traditional educational settings provide autonomy to approximate practice specific to language practice and expose candidates to heterogeneous ELLs, including children and adults, immigrants and refugees, with diverse social, emotional, developmental, cultural, linguistic, and academic backgrounds and needs (Heineke et al., Citation2012; Wrigley, Citation2000).

Recommendations for practice center on the purposeful integration of field-based experiences to prepare teacher candidates for the growing diversity of ELLs in U.S. classrooms and schools (AACTE, 2010; García et al., Citation2010; NCATE, 2010). We urge teacher educators to explicitly and purposively connect fieldwork in schools and communities with the content of university-based course sessions (García et al., Citation2010; Zeichner, Citation2006), moving away from clinical experiences conceptualized as separate and disconnected from course content (Cochran-Smith, Davis, & Fries, Citation2004; Goodwin, Citation1997; Hollins & Torres-Guzman, Citation2005). To create these connected and meaningful learning experiences, we recommend the inclusion of community-based organizations for fieldwork (Baldwin et al., Citation2007), as candidates can engage in extensive and authentic teaching practices with widely diverse children and adult ELLs. Whether at schools or community organizations, we promote the development of collaborative partnerships to design and manage fieldwork in cooperation with teachers and leaders (McDonald et al., Citation2011; Murrell, Citation2000), including candidate placement and supervision. We then encourage teacher educators to strategically place candidates in field sites based on programs of study, future teaching assignments, and cultural and linguistic backgrounds; in this way, candidates can build on personal and professional background knowledge to hone in on ELL-specific knowledge, skills and dispositions (Lucas et al., Citation2008). By bringing in rich knowledge, skills, and experiences from various school and community settings, candidates can collaborate and learn from one another, recognizing the broad array of assets, abilities, and needs of the growing number of culturally and linguistically diverse ELLs in U.S. classrooms and schools.

References

- American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education (2010). 21 st century knowledge and skills in educator preparation . Author: Washington, DC.

- Ann, J., & Peng, L. (2005). The relevance of linguistic analysis to the role of teachers as decision makers. In K. E. Denham & A. C. Lobeck (Eds.), Language in the schools: Integrating linguistic knowledge into K-12 teaching (pp. 71–86). London: Routledge.

- Baldwin, S. C., Buchanan, A. M., & Rudisill, M. E. (2007). What teacher candidates learned about diversity, social justice, and themselves from service-learning experiences. Journal of Teacher Education, 58, 315–327.

- Ball, D. L., & Cohen, D. K. (1999). Toward a practice-based theory of professional education: Teaching as the learning profession. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60, 497–511.

- Ball, D. L., Sleep, L., Boerst, T. A., & Bass, H. (2009). Combining the development of practice and the practice of development in teacher education. The Elementary School Journal, 109, 458–474.

- Banks, J. A., Au, K. H., Ball, A. F., Bell, P., Gordon, E. W., Gutiérrez, K. D., Heath, S. B., Lee, C. D., Lee, Y., Mahiri, J., Nasir, N. S., Valdés, G., & Zhou, M. (2007). Learning in and out of school in diverse environments: Life-long, life-wide, life-deep. Seattle: University of Washington Center for Multicultural Education.

- Barry, N. H., & Lechner, J. V. (1995). Preservice teachers’ attitudes about and awareness of multicultural teaching and learning. Teaching & Teacher Education, 11(2), 149–161.

- Berk, L. E., & Winsler, A. (1995). Scaffolding children’s learning: Vygotsky and early childhood education. Washington DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Bollin, G. G. (2007). Preparing teachers for Hispanic immigrant children: A service learning approach. Journal of Latinos and Education, 6, 177–189.

- Boyle-Baise, M., & Kilbane, J. (2000). What really happens ? A look inside service-learning for multicultural teacher education. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 7, 54–64.

- Buchanan, A., Baldwin, S. C., & Rudisill, M. E. (2012). Service learning as scholarship in teacher education. Educational Researcher, 31, 30–36.

- Burant, T. J., & Kirby, D. (2002). Beyond classroom-based early field experiences: Understanding an “educative practicum“ in an urban school and community. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(5), 561–575.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Fries, M. (2005). The AERA panel on research and teacher education: Context and goals. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 37–68). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Cochran-Smith, M., Davis, D., & Fries, K. (2004). Multicultural teacher education: Research, practice, and policy. In J. Banks & C. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 931–975). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(1), Retrieved March 9, 2010, from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v2018n2011/

- Dewey, J. (1965). The relation of theory to practice in education. In M. Borrowman (Ed.), Teacher education in America: A documentary history (pp. 140-171). New York: Teachers Collect Press. (Original work published in 1904)

- Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In M. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 119-161). New York: MacMillan.

- Ericsson, K. A. (2002). Attaining excellence through deliberate practice: Insights from the study of expert performance. In M. Ferrari (Ed.), The pursuit of excellence in education (pp. 21-55). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Finnigan, K., & Gross, B. (2007). Do accountability policy sanctions influence teacher motivation? Lessons from Chicago’s low-performing schools. American Educational Research Journal, 44, 594–629.

- Flores, B. B., Sheets, R. H., & Clark, E. R. (Eds.) (2011). Teacher preparation for bilingual student populations: Educar para transformar. New York: Routledge.

- Fry, R. (2008). The role of schools in the English language learner achievement gap. Washington, DC: Pew Research Hispanic Center. Retrieved October 1, 2012, from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/06/26/the-role-of-schools-in-the-english-language-learner-achievement-gap/

- Gándara, P., & Hopkins, M. (2010). The changing linguistic landscape of the United States. In P. Gándara & M. Hopkins (Eds.), Forbidden language: English learners and restrictive language policies (pp. 7–19). New York: Teachers College.

- García, E., Arias, B. M., Harris-Murri, N. J. & Serna, C. (2010). Developing responsive teachers: A challenge for a demographic reality. Journal of Teacher Education, 61, 132–142.

- Gándara, P., & Maxwell-Jolly, J. (2006). Critical issues in developing the teacher corps for English learners. In K. Téllez & H.C. Waxman (Eds.), Preparing quality educators for English language learners: Research, policies, and practices (pp. 99–120). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- González, V. (2005). Cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic factors influencing monolingual and bilingual children’s cognitive development. NABE Review of Research & Practice, 3, 67–104.

- Goodwin, A. L. (1997). Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Multicultural Teacher Education: Past Lessons, New Direction. In I. E. King, E. R. Hollins, & W.C. Hayman (Eds.), Preparing Teachers for Cultural Diversity (pp. 5-22). New York: Teachers College Press. Gottlieb, 2006

- Gottlieb, M. (2006). Assessing English language learners: Bridges from language proficiency to academic achievement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., & Williamson, P. (2009a). Teaching practice: A cross-professional perspective. Teachers College Record, 111, 2055–2100.

- Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2009b). Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 273–289.

- Grossman, P., & McDonald, M. (2008). Back to the future: Directions for research in teaching and teacher education. American Educational Research Journal, 45, 184–205.

- Heineke, A. J., *Coleman, E., *Ferrell, E., & *Kersemeier, C. (2012) Opening doors for bilingual students: Recommendations for building linguistically responsive schools. Improving Schools, 15, 130-147.

- Hollins, E., & Torres-Guzman, M. E. (2005). Research on preparing teachers for diverse populations. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 477–544). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Krashen, S.D. (1987). Principles and practices in second language acquisition. New York: Prentice-Hall.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The Dreamkeepers: Successful teaching for African-American students. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 17–18.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2000). Fighting for our lives: Preparing teachers to teach African American students. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 206–214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003008

- Lee, R. E., Eckrich, L. L. T., Lackey, C., & Showalter, B. D. (2010). Pre-service teacher pathways to urban teaching: A partnership model for nurturing community-based urban teacher preparation. Teacher Education Quarterly, 37(3), 101–122.

- Lucas, T. (Ed.) (2011). Teacher preparation for linguistically diverse classrooms: A resource for teacher educators. New York: Routledge.

- Lucas, T., Villegas, A. M., & Freedson-González, M. (2008). Linguistically responsive teacher education: Preparing classroom teachers to teach English language learners. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 361–373.

- Maxwell, J. A. (1996). Qualitative research design: An iterative approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- McDonald, M., Tyson, K., Brayko, K., Bowman, M., Delport, J., & Shimomura, F. (2011). Innovation and impact in teacher education: Community-based organizations as field placements for preservice teachers. Teachers College Record, 113(8), 1668–1700.

- McIntyre, D.J., Byrd, D. M., & Foxx, S. M. (1996). Field and laboratory experiences. In J. Sikula (Ed.) Handbook of Research on Teacher Education (2nd ed.) (pp. 171-193). New York: Simon Schuster Macmillan.

- Mercado, C. I., Brochin-Ceballos, C. (2011). Growing quality teachers: Community-oriented preparation. In B. B. Flores, R. H. Sheets, & E. R. Clark. (Eds.). Teacher preparation for bilingual student populations: Educar para transformer (pp. 217–229). New York: Routledge.

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Moll, L. C., & González, N. (1997). Teachers as social scientists: Learning about culture from household research. In P. Hall (Ed.), Race, ethnicity and multiculturalism: Vol. 1. Missouri Symposium on and Educational Policy (pp. 89-114). New York: Garland.

- Murrell, P. C. (2000). Community teachers: A conceptual framework for preparing exemplary urban teachers. The Journal of Negro Education, 69 (4), 338–348.

- National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. (2010). Transforming teacher education through clinical practice: A national strategy to prepare effective teachers. Report of the Blue Ribbon Panel on Clinical Preparation and Partnerships for Improved Student Learning. Author: Washington, DC.

- National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. (2010). The growing number of English learner students 1998/99 – 2008/09. Washington, DC: Author

- Nevarez-LaToree, A. A., Sanford-DeShields, J. S., Soundy, C., Leonard, J., & Woyshner, C. (2008). Faculty perspectives on integrating linguistic diversity issues into an urban teacher education program. In M. E. Brisk (Ed.), Language, culture, and community in teacher education (pp. 267–312). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- O’Malley, J. M., & Pierce, L. V. (1996). Authentic assessment for English Language Learners: Practical approaches for teachers. New York: Addison-Wesley.

- Onore, C., & Gildin, B. (2010). Preparing urban teachers as public professionals through a university-community partnership. Teacher Education Quarterly, 37(3), 27–44.

- Onosko, J. (2011). Race to the Top leaves children and future citizens behind: The devastating effects of centralization, standardization, and high stakes accountability. Democracy & Education, 19(2), 1–11.

- Reed, D. F. (1998). Speaking from experience: Anglo-American teachers in African American schools. Clearing House, 71, 224–231.

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ruiz, J. H., & Koch, C. A. (2011). Bilingual education programs and English language learners in Illinois. Springfield, IL: Illinois State Board of Education.

- Schmidt, P. (1999). Focus on research: Know thyself and understand others. Language Arts, 76, 332–340.

- Shin, H. B., & Kominski, R. A. (2010). Language use in the United States: 2007 (American community survey reports, ACS-12). Washington, DC., U.S. Census Bureau.

- Sleeter, C. E. (2008). Preparing White teachers for diverse students. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemster, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions in changing contexts (3rd ed., pp. 559–582). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sleeter, B. C., Torres, M. N., & Laughlin, P. (2004). Scaffolding conscientization through inquiry in teacher education. Teacher Education Quarterly, 31, 81–96.

- Solano-Flores, G., Soltero-González, L. (2011). Meaningful assessment in linguistically diverse classrooms. In B. B. Flores, R. H. Sheets, & E. R. Clark. (Eds.). Teacher preparation for bilingual student populations: Educar para transformer (pp. 146–163). New York: Routledge.

- Téllez, K., & Waxman, H. C. (Eds.). (2006). Preparing quality educators for English language learners: Research, policies, and practices. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Tinajero, J. V. and Hurley, S. R. (2001). Assessing progress in second-language acquisition. In S. R. Hurley and J. V. Tinajero (Eds.), Literacy Assessment of Second Language Learners (pp. 27–42). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Troyan, F. J., Davin, K. J., & Donato, R. (2013). Exploring a practice-based approach to foreign language teacher preparation: A work in progress. Canadian Modern Language Review, 69(2), 154–180. doi: https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.1523

- Ukpokodu, O. N. (2003). Teaching multicultural education from a critical perspective: Challenges and dilemmas. Multicultural Perspectives, 5(4), 17–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327892MCP0504_4

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2010). The condition of education 2010 (NCES 2010–028)

- Valdés, G., Bunch, G., Snow, C., & Lee, C. (2005). Enhancing the development of students’ language. In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 126–168). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wade, R. C. (2000). Service-learning for multicultural teaching competency: Insights from the literature for teacher educators. Equity & Excellence in Education, 33, 21–29.

- Wrigley, P. (2000). The challenge of educating English language learners in rural areas. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No, ED 469 542)

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. London: Sage.

- Zeichner, K. (2006). Studying teacher education programs. In R. Serlin & C. Conrad (Eds.), Handbook for research in education (pp. 80–94). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Zeichner, K. (1996). Designing educative practicum experiences for prospective teachers. In K. Zeichner, S. Melnick, & M. L. Gomez (Eds.), Currents of reform in preservice teacher education (pp. 215–234). New York: Teachers College Press.

Appendix A

Table 1 Language Diversity: Top 10 Non-English Languages Used in the Chicago Area (Shin & Kominski, Citation2010)

Table 2 Language Diversity: Top 10 Native Languages of English Learners in Illinois Schools (Ruiz & Koch, Citation2011)

Table 3 Teacher Candidate Cases

Table 4 Candidate Placement and Student Selection

Figure 1. Multiple-Case Study Design. (Yin, Citation2009)