Abstract

There is a need to better understand the experiences and perspectives of bilingual Latina teachers in U.S. schools. One way to gain a deeper understanding of bilingual Latina teachers is to examine their perspectives and experiences around being a well-educated person. A greater understanding of how teachers negotiate being well educated is important for considering tensions with conflicting values and worldviews around cultural constructs that shape role expectations, views of education, and social interactions. To build on existing studies and further theorize teacher identity-in-context, this qualitative study examines how bilingual Puerto Rican teachers conceptualize and enact notions of being a well-educated person. I utilized a combined interpretive framework (critical biculturalism, chicana/feminism, borderland theory) to analyze participants’ personal, professional, and community knowledge. Like a braid, I viewed these three categories as separate, yet interwoven strands of identity. By including these three strands, my aim was to better understand the experiences and perspectives of teachers around a focus area that potentially challenges dominant views of being well educated. Findings demonstrate how participants affirm bilingual-bicultural stances and cultivate respectful resistance amidst multiple roles and changing contexts. More specifically, participants negotiate entangled contradictions around being bien educada and being well educated in their roles as daughters, wives, mothers, and teachers. Implications and recommendations for research and practice are discussed.

There is a need to better understand the experiences and perspectives of bilingual Latina teachers in U.S. schools (Ochoa, Citation2007; Quiocho & Rios, 2000). Yet, Varghese and colleagues (Citation2005) remind us that “in order to understand teachers, we need to have a clearer sense of who they are: the professional, cultural, political, and individual identities which they claim or which are assigned to them” (p.22). One way to gain a deeper understanding of bilingual Latina teachers is to examine their perspectives and experiences around cultural constructs such as what it means to be a well-educated person (Galindo & Olguin, Citation1996; Galindo, Citation1996, 2007; Jackson, Citation2006; Ochoa, Citation2007; Prieto, Citation2013). To build on existing studies and further theorize teacher identity-in-context, my research examines how bilingual Puerto Rican teachers’ conceptualize and enact being a well-educated person. I demonstrate how participants take on a bilingual-bicultural stance where familial and cultural meanings merge and sustain each other in a critical and affirmative manner. However, I argue that cultural differences and traditional expectations around ser bien educada produce tensions which participants contend with amidst multiple roles and changing contexts.

Purpose and Aim

For the purposes of this paper, I elaborate on two thematic findings: a) affirming a bilingual-bicultural stance and b) cultivating respectful resistance. The first theme emphasizes how personal, professional and community identities merge to affirm bilingual-bicultural perspectives about being a well-educated person. The second theme reveals how personal, professional, and community identities come together in tenuous ways and reflect points of entanglement. For instance, the participants experience tensions and struggles about conflicting and changing expectations related to being respectful and challenging authority. Subsequently, they negotiate entangled contradictions around being bien educada and being well educated in their roles as daughters, wives, mothers, and teachers.

My aim is to provide the reader with a rich and nuanced understanding of how perspectives of being well educated are formed and how cultural values are conceptualized and lived by the bilingual Latina teachers in this study. A greater understanding of how teachers negotiate being well educated is important for considering tensions with conflicting values and worldviews around a cultural construct that shapes role expectations, views of education, and social interactions. It is also important to discern how teachers’ perspectives and experiences related to interactions with institutions of schooling that operate on different notions around these constructs, particularly in the context of subtractive bilingual education, high stakes testing and accountability educational policies (Hursh, Citation2013; Valenzuela, Citation1999).

Literature Review

A broader and critical understanding of what it means to be well educated is necessary to move beyond the gauge of monolingual English-speaking, Anglo-oriented cultural models. However, only a handful of studies account for bilingual Latina teachers’ perspectives and experiences related to familial and cultural constructions of being a well-educated person (Galindo & Olguín, Citation1996; Jackson, Citation2006; Prieto, Citation2013; Quiñones, Citation2012; Weisman & Hansen, Citation2008). Existing qualitative studies reveal that bilingual Chicana and Mexican American teachers deliberately and strategically reclaim cultural values and resources as a way to bridge the home, school, and community lives of their students (Galindo, Aragon & Underhill, Citation1996; Galindo & Olguin, Citation1996; Galindo, Citation1996, 2007; Jackson, Citation2006; Prieto, 2009; Quiocho & Ríos, 2000). These studies suggest that these teachers, informed by broader conceptions of education and schooling, seek to build warm, personal relationships with students and parents in the process of building academic content knowledge and skills.

For example, Galindo and Olguín (1996) speak directly to ideas about what it means to be well educated from the perspective of Rebecca, a bilingual Latina teacher of living in Colorado. In fact, Galindo and Olguín use Rebecca’s autobiography as an illustrative case study to define the phrase ser bien educaada as an expression of “a cultural norm and expectation that children should be socialized in moral education and behave in a manner that reflects well on the parents and family” (p.42). What is significant in Rebecca’s account is that she traces this value across four generations and she frames this cultural construct through “family stories of the efforts and sacrifices her great-grandparents and grandparents had taken to have their children educated” (p.43) in formal academic institutions.

In the following excerpt, Rebecca discusses factors that influence her conceptual understanding of ser bien educada and the role it played in her family history, educational attainment and professional aspirations (among other areas):

My parents, like their parents before them, saw themselves as responsible for raising us well. The words ser bien educado[a] were associated with the home environment and meant having a sense of history and belonging, a feeling of loyalty to and identification with family, respect for others, and our ability to direct our energies toward being inclusive and the avoidance of self-centeredness. El ser bien educado[a], a value that I saw mirrored in the families of my families and friends, served me well when I had to deal with prejudice in my early school years and, I believe, kept me closely identified with the Hispanic culture in my later educational years. It is what directed me toward bilingual education and drove me to maintain and improve my Spanish language abilities. (p. 45).

In the passage above, Rebecca recognized familial and cultural values as resources that influenced numerous aspects of her life and career. She also noted that ser bien educada also fostered cultural preservation, resistance and resiliency in their lives (Chávez, 2007).

In the next passage, Galindo and Olguín (1996) describe how Rebecca’s conceptual understanding informed her teaching practices and interaction with parents:

Rebecca reminds parents of the importance of these cultural values, which, in addition to book learning, make a person in this cultural context well rounded. She additionally discusses these values in relation to racism and relates them to not reducing oneself to the lack of respect displayed in incidents of racism (p.47).

In the latter passage Rebecca connected cultural notions about being bien educada to being well-rounded in an academic, social, and moral sense. She also discussed notions of being bien educada/o in relation to racism in the U.S. schooling context. To this extent, she revealed a level of sociopolitical consciousness and ideological clarity (Bartolomé & Balderrama, Citation2001) as a bilingual teacher living and working in Colorado.

In a more recent qualitative study, Linda Jackson (Citation2006) provides a rich analysis of an experienced Mexican American Bilingual Education (MABE) teacher named Luz who lives and works in Texas. Jackson describes how Luz is “working from within” (Urietta, 2009) a rather constraining field of public education with high accountability and subtractive schooling practices. Using a combined interpretive framework (Chicana feminist theory, cultural production theory and cultural studies), Jackson wonders how a Mexican American teacher’s identity is constructed and reconstructed through social interactions in a particular context. She was also interested in learning how an activist teacher addresses equity in education for linguistic- minority children.

In her findings, Jackson connects ser bien educada with Valenzuela’s (1999) discussion of the Mexican-oriented meaning of educación and describes this concept as a cultural resource that points to cultural values related to respect and responsibility. She states, “[i]t involves responsibility and respect as well as the children’s behavior as a reflection on the honor of the family in the community” (p.138). Luz’s family valued formal education as an integral part of her overall educación and she received consejos about the importance of getting an education (in the form of degrees and academic credentials). Moreover, Luz’s sense of responsibility to go to college and set an example for her siblings (as a way of uplifting the whole family) derived from a conceptual understanding of what it means to be bien educada.

Jackson relates cultural constructions of ser bien educada with culturally responsive views of education and authentic forms of caring (Valenzuela, Citation1999).

She noted how Luz had “nurturing and mentoring relations” (p. 144) with her students, families and their respective communities. However, Jackson (Citation2006) shows that Luz is concerned with school-community relationships because of cultural tensions and intergenerational conflict related to contested and competing discourses around the role of testing, language, culture, and purposes of education. Jackson’s inquiry of a teachers’ cumulative lived experience through life history narratives potentially reveals how bilingual teachers may be “constant border crossers of competing discourses that provide[d] a space for possibilities that are fraught with contradictions and tensions” (p. 145). To this extent, Jackson’s in-depth study is helpful for gaining a better understanding of how cultural constructions of ser bien educada and being well educated shape the everyday life of a Mexican American Bilingual Education teacher in Texas.

Although existing studies offer rich narrative descriptions of Chicana and Mexican American educators, it is important not to romanticize and/or essentialize their understanding of cultural constructs. Moreover, there is a need to study this focus area with teachers working in U.S. public schools who represent a broader spectrum of Latina/o communities (Elenes & Delgado Bernal, Citation2010; Ochoa, Citation2007; Montero-Seiburth, 2005). Latina/o teachers come from a whole host of backgrounds (i.e., Puerto Rican, Colombian, Dominican, Guatemalan, Cuban, etc.). Sociohistorical, political, and other contexts differ across these ethnic and heritage language identity groups. Therefore, with my research, I wanted to gain a better understanding of how bilingual Puerto Rican teachers living and working in the US mainland might conceptualize and enact being a well-educated person. What lessons might their experiences and perspectives have for our understanding of what it means to be well educated beyond the gauge of monolingual English-speaking, Anglo-oriented cultural models?

Research Context and Participants

The study took place in Lakeview, a mid-sized city in Western New York where Puerto Ricans historically represent a large and fast growing Latino population. The school site, Gordon Elementary School, is a large elementary school in the Lakeview City School District (PreK-6) with nearly 700 students. Nearly 100% of the students at Gordon Elementary School were eligible for free or reduced lunch and the student population was predominantly Hispanics/Latino (60%), followed by African American (38%), and White students (2%), respectively. The school had partnerships with several community organizations to support literacy, character education, extended learning opportunities, and mentoring programs. Additionally, a local health management organization provided on-site medical and mental health services.

As shown in Table 1, the six participating teachers vary in age, certifications, and years of teaching experience. They also differ in terms of where they were born, where they were raised, and where they went to school and college.

Table 1 Participant Demographics

However, all participants are women who self-identified as Puerto Rican and were raised in Spanish dominant households with parents who were born in Puerto Rico. Moreover, all of the teachers are first generation college students at the undergraduate and graduate level.

Theoretical Framework

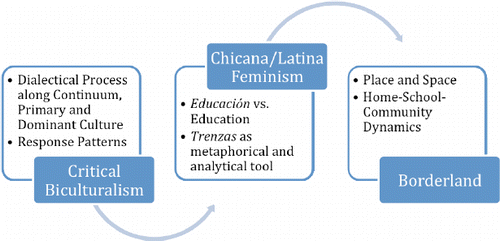

Critical Biculturalism

Given Puerto Rico’s sociopolitical context and legacies of colonialism, I utilize Darder’s (Citation1991/2012, Citation2011) critical biculturalism framework to explore the ways that participants negotiate their identities around cultural constructs that shape role expectations, views of education, and social interactions. Darder (Citation2011) defines critical biculturalism as “the process wherein individuals learn to function in two distinct sociocultural environments: their primary culture, and that of the dominant mainstream culture of the society in which they live” (p.20). In the context of this study, bilingualism represents the process by which participants mediate between dominant Anglo-centered discourses of educational institutions and their experiences as Puerto Rican bilingual education teachers in New York State. A critical biculturalism framework is a useful tool for examining to what extent participating teachers’ construction of meaning around ser bien educada and being well educated reveals a “a strong relationship between bicultural identity, critical social consciousness, and the development and expression of the bicultural voice” (Darder, Citation2011, p. 204). A critical bicultural framework is also helpful for considering how school and community conditions support, complicate, or hinder the development of a bicultural voice.

Chicana/Latina Feminism

Chicana/Latina Feminist theory also provides a useful lens to study how Puerto Rican teachers negotiate what it means to be a well-educated person. Collectively, this theoretical framework bridges Chicana/Latina feminist and cultural studies to education research—teaching, learning, and epistemology (Delgado Bernal, Burciaga, & Carmona, Citation2012; Elenes, et al. Citation2001; Saavedra & Perez, Citation2013; Villenas, Godinez, Delgado Bernal, & Elenes, Citation2006). This body of scholarship builds from the work of previous Chicana feminists who take a critical approach to Western feminism and mainstream (and insensitive) institutions that (re)produce sexism, classism and other oppressive conditions (Delgado Bernal, 1998).

I use Chicana/Latina feminism as a broad category that includes Border/Borderlands and Frontera scholarship (Anzaldúa, Citation1987; Citation1990; Elenes & Delgado Bernal, Citation2010). Borderland theory is helpful for exploring “the resiliency and complexity of Latino/a lives” (Villenas & Foley, Citation2002, p.204). A key strategy for incorporating this lens is to theorize place and space and consider “the interrelationship between educational institutions and outside forces such as the land, identity, and cultural practices” (Elenes & Delgado Bernal, Citation2010, p.74). This approach accounts for “a double move that critiques dominant cultural practices which subordinates Latinas/os” and simultaneously provides “a new language of possibility to counter the aforementioned dominant forms of thinking” (Elenes & Delgado Bernal, Citation2010, p.74). Doing so reveals an important theoretical move that Chicana Feminist and Borderland scholars advocate— the use of theory to deconstruct and reconstruct existing phenomena.

As shown in Figure 1, I utilized a combined interpretive framework grounded in critical biculturalism, Chicana/Latina feminism and Borderland theory to study bilingual Latina teachers’ perspectives and experiences around being a well-educated person. Overall, this triad approach places “cultural knowledge at the forefront of educational research to better understand the lessons of the homespace, our communities, and schools” (Elenes, González, Delgado-Bernal & Villenas, Citation2001, p. 595).

Research Design

The research design was inspired and informed by the Chicana/Latina feminist metaphorical concept of braids, or trenzas (see Quiñones, under review), and explores how multiple strands of identity shape teachers’ perspectives and experiences. Previous research exploring notions of ser bien educada with bilingual Latina teachers emphasized personal and professional domains, but did not inquire explicitly about community-related experiences and perspectives. To build on existing studies and further theorize teacher identity-in-context, I inquired about teachers’ personal, professional, and community knowledge in this focus area. Like a braid, I view these three categories as separate, yet interwoven strands of identity. By including these three strands, my aim was to better understand the experiences and perspectives of Puerto Rican teachers around a focus area that potentially challenges dominant views of being well educated.

Data Collection Process

For the data collection process, I collected data from multiple data sources between March and July of 2011. Data sources included a researcher journal, an initial teacher survey, one-on-one interviews and focus group interviews with participant reflections about preliminary findings. The primary data collection method was three in-depth interviews with each participant. These semi-structured interviews ranged from 30-60 minutes each and incorporated lived experiences around a shared concept or phenomena. I developed interview questions aimed at eliciting life stories that reflected participants’ multiple strands of identity (i.e. personal, professional and community) in relation to ser bien educada and being well educated. In the development of the semi-structured individual interview protocol, I drew from Seidman’s (Citation2006) approach that incorporates life history methods and narrative inquiry and focuses on lived experiences around a particular phenomena or concept. The first interview emphasized home, family and education history, the second interview highlighted details of experience, and the third interview elicited reflections on the meaning of lived experiences.

After conducting three interviews with each participant, I conducted two 90-minute focus groups (Stewart, Shamdasani, & Rook, Citation2007). My intention behind doing focus groups was twofold. First, I wanted participants to share their perspectives and experiences as social and cultural beings who work in the same school setting, but have different life histories. I was curious to see if there were any similarities and/or differences between their individual (one-on-one) interview responses and small group interview responses (and the nature of such comparisons). Second, I approached the focus group as an opportunity and space “for obtaining insights into group consensus or divergence on an issue or across accounts” of experiences and perspectives related to the research question(s). Third, I also wanted to share my “in-process interpretations garnered or developed from already-collected data” (Lankshear & Knobel, Citation2004, p.208). Since I view knowledge as socially constructed, the goal was not to ensure accuracy and validity, but rather to provide “a space for additional data, reflection and complexity” (Tracy, Citation2010, p. 848). Focus group interviews were audiotaped and transcribed for analysis and interpretation.

Data Analysis Process

Through a series of in-depth one-on-one interviews, followed by focus group interviews with participant reflections, I studied the lives of six teachers who shared stories about their upbringing, family values, schooling, and professional-occupational experiences. Moreover, they shared how their conceptual understanding of being well educated informed their role as teachers in an urban elementary school with a transitional bilingual education program.

The data analysis process included initial and focused coding, thematic and conceptual development, followed by a thematic analysis of the narrative profiles. Data analysis and interpretative procedures required relating categories and themes to relevant literature and considering ways of using pre-existing theory to build cumulative theory. As part of a first layer of interpretation, I followed Seidman’s (2006) recommendations and crafted life history narrative profiles of each participant using findings from the data analysis of multiple data sources. Similar to Godinez’s (2006) use of trenzas (braids) as an analytical tool, I asked questions of the data that were grounded in theory and wrote about the weaving of cultural knowledge, practices, and identities to describe how this particular group of teachers conceptualize and enact notions of being a well-educated person.

The narrative profiles of each participant that I crafted as part of the analysis process formed an integral part of classifying and cross checking the findings and interpretations. As part of thematic narrative analysis, I considered how the individual and collective teacher narratives relate to negotiation and meaning making around a cultural construct. In other words, I searched for patterns and correspondence between two or more categories within and across individuals and stories. I also looked for patterns, categories and themes among and across individuals within the narrative inquiry. I then clustered categories and themes as concepts in order to identify broader dimensions across them or dimensions within them. Finally, throughout this data analysis process, I used a researcher journal as a way to record how my preliminary and ongoing data analysis and interpretative processes compared and contrasted to prior research. The journal was helpful for processing my interpretive thinking about emerging themes and concepts.

Discussion of Thematic Findings

In what follows, I elaborate on two thematic findings: a) affirming a bilingual-bicultural stance and b) cultivating respectful resistance. The first theme emphasizes how personal, professional and community identities merge to affirm bilingual-bicultural stance. The second theme reveals how personal, professional, and community identities come together in tenuous ways and reflect points of entanglement.

Affirming Bilingual-Bicultural Stances

All of the participants in this study draw from familial experiences in how they conceptualized a person they considered to be bien educada and well educated. To illustrate this theme, I highlight one of the participants, Brenda, who is the oldest of five children raised in a single female-headed household. In the following passage from an individual interview, Brenda elaborates on her perspectives and experiences in this focus area. She draws from her home and family experiences, as well as from her community experiences, in her response:

To me, when I hear ser bien educado, I think of behaviors and your manners, and not necessarily your education. I think it comes with it, but, I’m thinking like in Puerto Rico when I heard ser educada or actua educado, era más como {it was more like} the way you behaved. It was like showing that you have manners, that you were proper, pedir la bendición {blessing}, use please and thank you. It was more like that than actually showing that you had a degree. Like I said, I think it education as book learning and formal schooling came with it, but I think the priority, or what came before having that education, was the way you act and show respect, definitely toward elders…

(Brenda, interview)

Brenda emphasizes a holistic and relational approach reflective of Latino values in her conceptual understanding (Eggers-Piérola, Citation2005). Moreover, Brenda, like all of the participants in the study, viewed being bien educada as foundational for being well educated (Montero-Sieburth, Citation2005; Reese, et al., Citation1995; Valdés, Citation1996; Zarate, Citation2007). Figure 2 represents this shared belief. The books (i.e., academics and formal schooling) are sustained via cultural knowledge and practices.

The idea of well-roundedness, which was emphasized by all participants, demonstrated that the primary cultural and dominant cultural perspectives are not necessarily at odds with one another. Instead, ser bien educada is the basis for which being well educated stands on, and is supported. In relation to the Chicana/Latina feminist concept of trenzas/braids, this additive understanding indicates something that cannot exist without each of its parts (Delgado Bernal, Citation2008; Montoya, Zuni Cruz, & Grant, Citation2008/2009).

Later during the interview Brenda, takes on a more contextualized bilingual-bicultural stance around what it means to be a well-educated person. In her own words, she states:

If someone tells me I am well educated, what comes to mind, for me…I see it both ways because I see, “You’re well educated” AND the cultural standpoint of being bien educada . Living here in the United States, I can definitely see it means you’ve gone to college, you’ve got a degree, some sort of degree, and maybe you’re a pretty well rounded person. You know a little bit about different subjects and different things. You may be a master in one area, but it’s not just your knowledge base and college degree or anything of that nature. What it also means is being a respectful person, having manners, and being a more well rounded person. Not just in what you know, but how you act, [and] how you treat others…But with ser bien educada, I don’t want to undermine that having an education, going to school, and doing well in school, that was also a part of it.

(Brenda, interview)

In the passage above we can note that on the one hand, Brenda associates the English expression “to be well educated,” with contextualized Anglo-oriented cultural values about formal schooling and degrees. On the other hand, she associates the Spanish expression with contextualized Latino-oriented cultural values about respect, manners, and behaviors. However, for Brenda, being bien educada included doing well in school, both when she lived in Puerto Rico and in New York State. In other words, Brenda reflects a hybrid view that is geographically fluid and representative of bilingualism-biculturalism as a dynamic and complex continuum.

When I asked Brenda to provide an example of a well-educated person, and to share some of the qualities and characteristics of this person, she spoke about her husband. In fact, Brenda paused for a bit when I asked her to think of a person who she considers to be well educated, and then she proceeded to talk about her husband. What is interesting to note in her response is how she takes on a bilingual-bicultural stance in relation to her role as a member of a prestigious, corporate-led national advisory board in education. Her thought process reveals critical thinking challenging normative assumptions about being well educated.

I would consider my husband well educated. I’m going to be honest, what first comes to mind when I think of well educated, I don’t think of my immediate family. Sometimes I think of these people who have these big old titles, and then I think back and think: What made them get there? Why are they well educated and why couldn’t you be? and your husband be? Why can’t your mom be? or whoever so…So, usually we think of all those people who I was with at the Advisory Board: “Oooh, these people are all well educated people.” But then, eventually, I think, “my husband is well educated!”

(Brenda, interview)

Brenda goes on to explain the qualities and characteristics that make her husband a well-educated person:

He is very knowledgeable in very different areas, and he’s also very good with technology and computers. Whenever I need help with something, not only with that, but he is very good with numbers and vocabulary and defining words and all of that, and so…And, in the cultural sense, then, also, because he is very respectful, he treats others kindly and with respect and, you know, he has very good manners, and so…as I think about it now, I think, well, “yeah, he is well educated!” from MY criteria, as what I see not only the cultural, Hispanic perspective of it, but also, from I think in the American perspective of it. He has a degree in computer science…He fits criteria for both.

(Brenda, interview)

In the passage above, Brenda begins to dichotomize or compartmentalize her primary (Spanish) and dominant (language) meanings of being a well-educated person. However, as she continued her thought process, Brenda combined her primary and dominant linguistic and cultural differences together as a form of resistance. She interrogated dominant/monolingual notions of being a well-educated person. In so doing, she (re)affirms a bicultural-bilingual understanding shaped by her personal, professional, and community experiences. To this extent, primary and dominant cultural and linguistic meanings merged and sustained each other in a critical, yet affirmative manner.

In addition to Brenda, an analysis of the other participants’ narratives around a person whom they consider to be well educated (and characteristics and qualities attributed to this person) reveal responses grounded in cultural negotiation, a socially conscious stance of affirming aspects of one’s own language and culture while working on equity in the dominant language and culture (Darder, Citation1991/2012). Subsequently, the participants note how cultural differences and expectations around being well educated also create tensions and challenges in their lives. All of the participants in this study negotiated entangled contradictions around being bien educada and well educated amidst multiple roles and changing contexts. In what follows, I elaborate on the second theme of cultivating respectful resistance, which speaks to having to negotiate entangled contradictions about conflicting and changing expectations related to being respectful and challenging authority.

Cultivating Respectful Resistance

Thus far, the findings demonstrate how participants conceptualize being well educated from critical bilingual-bicultural perspectives. However, cultural differences and expectations around ser bien educado and being well educated also created what I call nudos (knots), or points of entanglement that the participants contended with in multiple roles and changing contexts. These nudos reflect the growing awareness that primary cultural values and practices about being bien educada may serve to reinforce invisibility, silence, passivity, and complacency, particularly in relation to Latino students and their families within a stigmatized and racialized school and community setting. Subsequently, all participants shared stories that illustrated moments when personal, professional, and community experiences around notions of being well-educated came person together in tenuous ways, thereby producing sites of struggle, tension, and contradiction. In this second thematic finding, I expand on how participants negotiated entangled contradictions and engaged in practices intended to cultivate respectful resistance.

Although being polite, well mannered, and respectful were important qualities in relation to their personal, professional, and community identities, the participants questioned traditional cultural expectations around deference to authority. Thus, a common strand in the participants’ narratives was the idea of cultivating respectful resistance, or challenging deference to authority for the sake of advocacy and educational equity. This idea highlights how participants negotiated personal contradictions related to “ideas of control, power, and authority in their own lives” (Darder, Citation1991/2012, p.109).

A salient dimension of cultivating respectful resistance was recognizing tensions between respecting authority and challenging authority (including assumptions of what counts as authority, and the nature of authority). Darder (Citation1991/2012) reminds us that “the manner in which we conceptualize authority truly represents a necessary precondition for the manner in which we define ourselves, our work, and our very lives” (p.109). Along these lines, all participants talked about “ingrained” or “instilled” norms during their childhood and upbringing related to “knowing your place,” “doing as told,” or remaining silent and not talking back to authority figures (whether explicit or implicit). However, all of the participants resisted expectations and cultural values around absolute deference and obedience to authority, which is reinforced in the cultural concept of educación (Delgado Gaitan, Citation2004; Hill & Torres, Citation2010; Reese, Balzano, Gallimore & Goldberg, Citation1995). That is, being respectful, maintaining a proper demeanor/composure, and not demeaning a person’s authority was the ethical, responsible thing to do. Another element in this tension point between respecting authority and challenging authority had to do with decision-making, not only about what to say and how to say it but also about the right thing to do versus what needs to be done to make things right. In the following passage, Liana speaks to this idea:

…And I don’t think that you cannot NOT speak up. I think there is a way to do that. I think that when you do that in the correct way---If I was upset with my aunt, I wouldn’t yell at her, get in her face, and tell her she’s wrong. I would express to her how I feel, but not in a demeaning way, taking her authority away, she’s older. It’s rude. It’s disrespectful to do that to someone who is older and I think I take that wherever I go. It doesn’t even matter if I’m, if it’s a Hispanic person or not [a] Hispanic person, I just won’t… I think there is a thin line between what you are supposed to say and what you are not supposed to say and you can still express what you feel but there’s just a way of going about that, that make you still bien educada versus mal educada.

(Liana, interview)

Liana spoke at length about her mother as the strong and strict matriarch, the “be all and end all’ in the family whereas Helena described her father as the strong and strict patriarch in the family. Nevertheless, both Liana and Helena talked about being bien educada, but “almost to a fault” in their personal and professional life because cultural values came back to “bite them in the butt.” In contrast, Patricia drew from her father’s advice (who was a policeman in Lakeview) and talked at length about the importance of speaking up and being an advocate (for yourself and others), rather than remaining silent and “being like a doormat” (i.e. letting people step all over you). Although there were some differences between participants’ family/home-based experiences, a common thread was the idea of needing to “speak up” and “push back” on authority, but still doing so in a “respectful” manner.

For the participants in this study, speaking up, or pushing back to an adult (including an administrator or supervisor) in a respectful manner meant not yelling, shouting or cursing, but rather speaking back with an argument armed with supportive claims. To some extent, respectful resistance meant maintaining proper demeanor and composure during conflict, a difference of opinion or beliefs, or other stakes-driven and power-laden situations. This type of “talking back in a respectful manner” was part of advocating for yourself and others. Thus, the theme of cultivating respectful resistance reflects cultural negotiation (Darder, Citation1991/2012) because the participants acknowledged that aspects about ser bien educada can serve to reinforce invisibility, silence, passivity, complacency and marginalization, particularly in relation to emerging bilingual students and their families within a US context (García & Kleifgen, Citation2010). For instance, all of the participants emphasized how they encouraged the parents of the students to speak up and push back to school officials when and if necessary--in an effort to work toward educational equity. However, they also understand that some parents respected school officials (including teachers) as “the experts” (i.e. authority) and so they may not feel comfortable speaking up and pushing back (De Gaetano, Citation2007; Reese, Balzano; Gallimore, & Goldberg, Citation1995; Zarate, 2005).

Another important dimension of cultivating respectful resistance was recognizing and negotiating generational differences around cultural constructs. All participants conveyed stories about generational differences and ways that they contested and appropriated their understanding now as teachers, wives, and/or mothers. To illustrate this idea, I highlight Maribel, who had been a bilingual student at the same elementary school where the study took place. In fact, her father was a prominent Latino community advocate and leader who played a key role in establishing a bilingual program at this school site over thirty years ago.

Maribel traced a significant part of her current struggles as a teacher and mother to her grandmother and mother’s expectations to defer to authority and remain silent as a child. For this reason, she tried to cultivate respectful resistance with her own children:

Unfortunately, for many children, you’re seen, but not heard. But, I also think it depends on generations, too. Like at home, Tamara and my son are allowed to say what they have to say as long as they are being respectful. [For example], if you don’t agree with I’m saying, you’re not going to yell and shout, and all of that. When the emotions settle, you sit down and you say, “I don’t agree because…” You state your position. It may not change what I’m going to do, but you’re going to be heard. But I was never given that opportunity growing up. What my mother said went. That was it. End of story. There was no questioning. There was no saying anything. I couldn’t say, “why not?” “why” No! It was. That was it, and I think that has--It certainly has affected me as an adult. I think that there are times, even in my professional setting, where I feel like I need to take a stand, and sometimes I don’t. I don’t. I think sometimes it’s about choosing your battles. I do. I try to outweigh what the outcome is going to be, but, MANY times I think it’s because I wasn’t vocal as a child. I wasn’t allowed to question authority. So, when I’m here, I struggle with that. I still struggle with that.

(Maribel, interview)

In the passage above, Maribel admits that challenging authority continues to be a struggle for her as she works to express and develop of her own bicultural voice. Yet, in her efforts to cultivate respectful resistance in her children, Maribel engages in practices that allow her children to develop a voice rather than remain silent (in deference to authority).

By challenging expectations about silence and complete deference to authority, Maribel is producing and creating “new” constructions of what it means to be a well-educated person in a diasporic context (Rolón-Dow, Citation2010). In essence, Maribel seeks to mediate, reconcile, and integrate her lived experiences in an effort to retain primary cultural values around these cultural constructs in a critical manner that functions[ed] toward social transformation (Darder, Citation1991/2012, p.51-52). However, this was a site of struggle and an area of development for her as a daughter, mother, and teacher. In other words, Maribel negotiates entangled contradictions about being person who is bien educada and well-educated person as a bilingual Latina teacher.

Negotiating Entangled Contradictions During Testing Times

The nature of the bilingual program, combined with state, district, and school-mandated testing practices at the school was a source of entanglement and contradiction for the participants. During a focus group interview, Brenda and Liana reveal how their personal, professional, and community perspectives collide in light of language policies and testing practices. For example, Brenda acknowledged that even though she shared similar definitions of ser bien educado and well educated with other participants in the study, she felt it was important to recognize how testing practices and school policies served to reinforce narrow, dominant views of being well educated. In her own words, Brenda stated:

I think because we have a transitional model, and due to all the testing, and now our students have to take the ELA (English language arts) exam after one year in the district, or in the states for a year….in English. I think there is more of a push for us to prove our students to be well educated in the American, English sense, by knowing more English.

(Brenda, focus group)

In response to Brenda, Liana stated that all bilingual programs, to a certain degree, felt that pressure of having to teach more English because of data driven policies, but she also felt that this particular school’s testing practices were excessive:

Here in our building, specifically, we test A LOT! Like, EXTENSIVELY…we have been, for some reason, in the past 2-3 years, we pilot all these tests. We’re a data driven school, so…anything to collect data! …So I do agree with Brenda in that sense that here, in our school, per se, there is that push to be well educated because those tests are important to show progress, to show that they’re learning, to show that they’re growing.

(Liana, focus group)

Consequently, Liana suggested that although schooling practices were moving the school toward more narrow definitions of what it means to be well educated, she made an effort to incorporate both definitions in her approach to teaching and learning.

I think that I push my kids to be both. I think it’s very very important for them to not just be bien educado, but to be well educated as well and I think that it has to be a combination of both…so doing well on a test would be part of that. So, when you do well, when you do your homework. When you do work that is outstanding, that shows how well educated you are. And then when you add the whole acting right and doingthings and being polite, it just makes you a whole, well-rounded person.

(Liana, focus group)

Moreover, Liana went on to talk about “the battle” between testing language versus content:

I think that’s my inner conflict since I’ve been teaching here, is being able to say that our kids are not stupid! They do well academically, but we need to begin to see the distinction for our ELL students, as language versus content. We need to be very clear on what we’re testing. And when we’re testing what? And then if we are testing content that it be in a language that is understandable to them because if they can’t understand it, then we’re not really testing content, we’re testing language. And I think that here in this building, we ride that thin line so much and I think as teachers we fight that battle continuously…

(Liana, focus group)

In the passage below, Liana again tied the discussion of testing around ser bien educado/being well educated with narrow, dominant criteria for success in the school context:

But I know that here, the push is English, English, English. And it does have an effect on our kids. And on their growth academically, and that title “being well educated” kinda looms over them because they’re not seen as that…

(Liana, focus group)

Overall, both Brenda and Liana negotiated the demands of being a bilingual teacher within a transitional and subtractive bilingual program that formed part of a “data-driven” school with significant amounts of testing in English. This contextual reality represented nudos in their lives. Even though their own conceptualizations of ser bien educado/being well educated reflected additive bilingual-bicultural stances, the school’s subtractive transitional bilingual program, combined with over-testing in English, led to constraining and conflicting interactions and practices that they had to contend with on a daily basis.

To summarize, the participants in this study conceptualize and enact a bicultural-bilingual stance where the “Spanish” sense of being bien educada are foundational to an “English” sense of being well educated. However, the findings demonstrate how cultural differences and traditional expectations around ser bien educada produce layered tensions that teachers contend with. All participants tell stories revealing tensions and struggles about conflicting and changing expectations related to being respectful, questioning injustices and challenging authority. In their personal, professional, and community lives, the participants in this study negotiate entangled contradictions in an effort to move away from cultural practices that reinforced silence, passivity, and complacency. Again, I refer to participants’ tensions as nudos (i.e. knots), or points of entanglement. Nudos are significant because they speak to how participants sought to mediate, reconcile, and integrate their lived experiences in a critical manner that functioned toward social transformation (Darder, Citation1991/2012).

Implications and Recommendations for Research and Practice

This paper drew from a qualitative study using life history and narrative inquiry to examine the experiences and perspectives of six bilingual Puerto Rican teachers in relation to constructions of being a well-educated person. The findings in this study account for the intersection of formal education and academic knowledge with that of pedagogies of the home and everyday experience (Delgado Bernal, Citation2006). All of the participants in this study negotiated entangled contradictions around being bien educada and well educated amidst multiple roles and changing contexts. By emphasizing how participants negotiated entangled contradictions around these cultural constructs, I demonstrate the tensions and paradoxical relationships that exist amidst culturally and linguistically grounded experiences. To this extent, this study provides “meaning to cultural ways of knowing and linguistic expressions” reflective of differences in views of education and schooling (Villenas, Godinez, Delgado Bernal & Elenes, Citation2006, p 4).

This research supports the idea that “bicultural practices, values, and norms” around being well educated are “being learned and shared in varying sociocultural contexts” (Flores, Clark, & Sheets, Citation2011, p.4). Future studies can explore various sociocultural contexts in order to inform teacher preparation (see Zentella, Citation1997, Citation2005). Given demographic trends revealing that Latinas/os represent the largest and fastest growing ethnic group in the US (Flores, Clark, & Sheets, Citation2011; Irizarry, Citation2011; Irizarry & Donaldson, Citation2012), it is worthwhile for educational researchers and teacher educators to direct their attention to connections in Latina/o teacher knowledge that extend “beyond boundaries and borders” (Flores, Clark, & Sheets, Citation2011, p.3). However, it is important for teachers and schools not to reduce ser bien educada to merely respect, manners and comportment (see Prados Olmos & Marquez, 2001; Prins, Citation2011). In fact, my hope in exploring this focus area further was not to essentialize, or even further dichotomize cultural constructs. I also did not intend to operationalize these concepts or “package” them and “infuse” them into scripted teacher curriculum guides promoting “traditional values” or “Latino family friendly” character education programs in schools. Instead, my hope in exploring this line of inquiry was to serve as a catalyst for educators to reflect on how notions of being well educated permeate our personal, professional, and community experiences.

While not meant to be romanticized, the findings in this study do begin to provide insights about “the extraordinary force contained within the attitudes, knowledge, skills, and experiences present within two lived languages” (Sheets, Flores & Clark, Citation2011, p. 16). Thus, one conclusion that can be drawn from this study is that bilingual Puerto Rican teachers conceptualize and enact ser bien educada/o in very similar ways to that of Mexican American and Chicana/o bilingual education teachers in different US contexts (i.e. California, Texas, Colorado, New York). Both Latina/o subgroups anchor their conceptual understanding in family epistemology and home-based expectations and practices around respect, manners and comportment across settings and situations. Both Mexican American/Chicana and Puerto Rican bilingual teachers negotiate linguistic and cultural differences and hold broader views of what it means to be well educated.

This research surfaces opportunities and challenges for bilingual teacher educators and multiple education stakeholders to address, particularly for those involved in collective and participatory-based efforts to improve the educational experiences of Latino children, families, and communities. Similar to the bilingual teachers in Varghese et al.’s (Citation2005) work, the teachers in this study were “involved in a more challenging process wherein they actively sought and negotiated an identity as bilingual teachers and often developed conflicted and marginalized professional identities” (p. 29). Like students, bilingual Latina teachers shape—and are shaped by—their cultural values, as well as “by their constant struggles to survive within the myriad of cultural contradictions they face each day” (Darder, 2012, p. 64). Accordingly, the concept of nudos exemplifies how notions of being a well-educated person do indeed represent “a contested terrain” (Villenas, Citation2002) in the lives of Latina teachers.

This study was limited to the experiences and perspectives of female teachers and the analysis in this particular article did not dig deep into the role of gender. Future publications can explore the role of gender more explicitly and another study can inquire about the experiences and perspectives of male teachers in this focus area. Nevertheless, since previous research suggests that experiences and perspectives around being a well-educated person are shared between and among Latino cultures, it is a cultural resource that can be utilized as part of a community-oriented approach to teacher preparation (see Flores, Clark, & Sheets, Citation2011; Mercado & Brochin-Ceballos, Citation2011).

This line of inquiry can also be used as a tool for fostering critical consciousness around narrow views of being well educated (Rendón, Citation2009). Teacher educators and school leaders (including teachers) can play a key role for engaging families, students, teachers, and community members in dialogue and activities aimed at promoting a deeper, broader, and asset-based or resource rich views of what it means to be a well-educated person. My emphasis here has been that it is important to challenge dominant notions and take a critical approach that accounts for bilingual teachers’ experiences and perspectives. A critical approach is also one that continues not only to interrogate assumptions surrounding cultural constructions of being well educated, but also continues to examine these challenges and opportunities in relation to educational equity for our school communities.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sandra Quiñones

Sandra Quiñones is an Assistant Professor of Literacy Education in the Department of Instruction and Leadership in Education at Duquesne University.

References

- Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La frontera: The new mestiza. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

- Anzaldúa, G. (1990). Making face, making soul/haciendo caras: Creative and critical perspectives by feminists of color. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

- Auerbach, S. (2011). Learning from Latino families. Educational Leadership, 68(8), 16–21.

- Auerbach, S. (2007). From moral supporters to struggling advocates: Reconceptualizing parentroles in education through the experience of working-class families of color. Urban Education, 42(3), 250–283.

- Bartolomé, L.I., & Balterrama, M.V. (2001). The need for educators with political and ideological clarity: Providing our children with “The Best.” In M. Reyes & J. Halcón (Eds.), The best for our children: Critical perspectives on literacy for Latina/o students (pp. 48-64). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Chavez, C. (2007). Five generations of a Mexican American family in Los Angeles: The Fuentes story. Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Darder, A. (1991/2012). Culture and power in the classroom: Educational foundations for the schooling of bicultural students. New York, NY: Bergin and Garvey.

- Darder, A. (2011). A dissident voice: Essays on culture, pedagogy, and power. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- De Gaetano, Y. (2007). The role of culture in engaging Latino parents’ involvement in school. Urban Education, 42(2), 145–162.

- De la Vega, E. (2007). Mexicana/Latina mothers and schools: Changing the way we view parent involvement. In M. Montero-Sieburth & E. Meléndez (Eds.), Latinos in a Changing Society, (pp. 161–182). Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Delgado Bernal, D. (2006). Mujeres in college: Negotiating identities and challenging educational norms. In D. Delgado Bernal, C.A. Elenes, F.E. Godinez, & S. Villenas (Eds.), Chicana/Latina education in everyday life: Feminist perspectives on pedagogy and epistemology (pp. 113–132). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Delgado Bernal, D., Burciaga, R., & Flores Carmona, J. (2012). Chicana/Latina testimonios: Mapping the methodological, pedagogical, and political. Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(3), 363–372.

- Delgado Bernal, D., Elenes, C.A., Godinez, F.E., & Villenas, S. (Eds). (2006). Chicana/Latina education in everyday life: Feminista perspectives on pedagogy and epistemology. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Delgado Bernal, D. (2008). La trenza de identidades: Weaving together my personal, professional, and communal identities. In K.P. González & R. V. Padilla (Eds.), Doing the public good: Latina/o scholars engage civic participation (pp. 135–148). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Delgado-Gaitán, C. (2004). Involving Latino families in schools: Raising student achievement through home-school partnerships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Díaz, E. & Flores, B. (2001). Teacher as sociocultural, sociohistorical mediator: Teaching to the potential. In M. Reyes & J.J. Halcón (Eds.), The best for our children: Critical perspectives on literacy for Latino students. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Eggers-Piérola, C. (2005). Connections & commitments, Conexión y compromise: Reflecting Latino values in early childhood programs. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Elenes, C. A., González, F., Delgado Bernal, D., & Villenes, S. (2001). Introduction: Chicana/Mexicana feminist pedagogies: Consejos respeto, y educación. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 14(5), 595–602.

- Elenes, C. A., & Delgado Bernal, D. (2010). Latina/o education and the reciprocal relationship between theory and practice: Four theories informed by the experiential knowledge of marginalized communities. In E. G. Murrillo, S. A. Villenas, R. Trinidad Galván, J. Sánchez Muñoz, C. Martínez, & M. Machado-Casas (Eds.), Handbook of Latinos and education: Theory, research and practice (pp. 196–223). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Espino, M., Vega, I.I., Rendón, L.I., Ranero, J., & Muñiz, M.M. (2012). The process of reflexión in bridging testimonios across lived experience. Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(3), 444–459.

- Flores, G. M. (2011). Racialized tokens: Latina teachers negotiating, surviving and thriving in a White woman’s profession. Qualitative Sociology, 34, 313–335.

- Galindo, R. (1996). Reframing the past in the present: Chicana teacher role identity as a bridging identity. Education and Urban Society, 29(1), 85–102.

- Galindo, R., Aragon, M., & Underhill, R. (1996). The competence to act: Chicana teacher role identity in life and career narratives. The Urban Review, 28(4), 279–308.

- Galindo, R., & Olquín, M. (1996). Reclaiming bilingual educators’ cultural resources: An autobiographical approach. Urban Education, 31, 29–56.

- Galindo, R. (2007). Voices of identity in a Chicana teacher’s occupational narratives of the self. The Urban Review, 39, 251–280.

- García, O., & Kleifgen, J. (2010). Educating emergent bilinguals: Policies, programs, and practices for English language learners. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Godinez, F. E. (2006). Haciendo que hacer: Braiding cultural knowledge into educational practices and policies. In D. Delgado Bernal, C.A. Elenes, F.E. Godinez, & S. Villenas (Eds.), Chicana/Latina education in everyday life: Feminist perspectives on pedagogy and epistemology (pp. 25–38). Albany, NY: State University of New York.

- González, F. (1998). The formations of Mexicananess: Trenza de identidades multiples. Growing up Mexicana: Braids of multiple identities. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 81–102.

- González, F. E. (2001). Haciendo que hacer, Cultivating a Mestiza worldview and academic achievement: Braiding cultural knowledge into educational research, policy, practice. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 14, 641–656.

- Hidalgo, N.M. (1999). Toward a definition of a Latino family research paradigm. In L. Parker, D. Deyhle, S. Villenas (Eds.), Race is...Race isn't: Critical race theory and qualitative studies in education (pp. 101-124). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Hidalgo, N. M. (2005). Latino/a families’ epistemology. In P. Pedraza & M. Rivera (Eds.), Latino education: An agenda for community action research (pp. 375–402). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Hill, N. E. (2009). Culturally-based world views, family processes, and family-school interactions. In S. L. Christenson & A. Reschly (Eds.), The handbook on school- family partnerships for promoting student competence (pp. 101–127). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hill, N.E., & Torres, K. (2010). Negotiating the American dream: The paradox of aspirations and achievement among Latino students and engagement between their families and schools. Journal of Social Issues, 66(1), 95–112.

- Hursh, D. (2013). Raising the stakes: High stakes testing and the attack on public education in New York. Journal of Educational Policy, 28(5), 574–588.

- Irizarry, J.G. (2011). En la lucha: The struggles and triumphs of Latino/a preservice teachers. Teachers College Record, 113(12), 2804–2835.

- Irizarry, J.G. & Donaldson, M.L. (2012). Teach for América: The Latinization of U.S. schools and the critical shortage of Latina/o teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 49(1), 155–194.

- Jackson, L.G. (2006). Shaping a borderland professional identity: Funds of knowledge of a bilingual education teacher. Teacher Education and Practice, 19(2), 131–148.

- Jackson, L.G. (2009). Becoming an activist Chicana teacher: A story of identity in the making of a Mexican American bilingual educator in Texas. Unpublished dissertation. University of Texas at Austin.

- Jensen, B., & Sawyer, A., (eds.) (2013). Regarding educación. New York, NY: Teachers College.

- Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2004). A handbook for teacher research: From design to implementation. New York, NY: Open University Press.

- Mercado, C.I., & Brochin-Ceballos, C. (2011). Growing quality teachers: Community- oriented preparation. In B. B. Flores, R. H. Sheets, & Clark, E. R. (Eds.), Teacher preparation for bilingual student populations: Educar para transformar (pp. 217–229). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Montero-Sieburth, M. (2005). Explanatory models of Latino education during the reform movement of the 1980s. In P. Pedraza& M. Rivera (Eds.), Latino education: An agenda for community actions research (pp. 99–153). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Montoya, M. (1994). Mascaras, trenzas, y greñas: Un/masking the self while un/braiding Latina stories of legal discourse. Chicano-Latino Law Review, 15, 1–37.

- Montoya, M., Zuni Cruz, C., & Grant, G., (2008/2009). Narrative Braids: Performing Racial Literacy. American Indian Law Review, 33(1), 153–199.

- Monzó, L.D., & Rueda, R. (2003). Shaping education through diverse funds of knowledge: A look at one Latina para-educators' lived experiences, beliefs, and teaching practice. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 34(1), 72-95.

- Ochoa, G. (2007). Learning from Latino teachers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Olmedo, I. (2003). Accommodation and resistance: Latinas struggle for their children's education. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 34(4), 373-395.

- Prado-Olmos, P.L., & Marquez, J. (2001). Ethnographic studies of Éxito para Todos. In R. Slavin & M. Calderón (Eds.), Effective programs for Latino students (pp. 231–250). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Prieto, L. (2013). Maestras constructing mestiza consciousness through agency within bilingual education. Journal of Latino-Latin American Studies, 5(2), 167–180.

- Prins, E. (2011). On becoming an educated person: Salvadoran adult learners’ cultural model of educación/education. Teachers College Record, 113(7), 1477–1505.

- Quiñones Rosado, S. (2012). Educated entremundos: Understanding how Puerto Rican diaspora teachers conceptualize and enact ser bien educado and being well educated (Doctoral dissertation, University of Rochester). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database.

- Quiñones, S. (under review). (Re)Braiding to tell: Using trenzas as a metaphorical-analytical tool in qualitative research. Submitted to the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education.

- Reese, L., Balzano, S., Gallimore, R., & Goldberg, C. (1995). The concept of educación: Latino family values and American schooling. International Journal of Education Research, 23(1), 57–61.

- Rendón, L. (2009). Sentipensante (sensing/thinking) pedagogy: Education for wholeness, social justice and liberation. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Rolón-Dow, R. (2010). Taking a diasporic stance: Puerto Rican mothers educating children in a racially integrated neighborhood. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 4, 268-284.

- Saavedra, C.M., & Perez, M.S. (2013). Chicana/Latina feminism(s): Negotiating pedagogical borderlands. Journal of Latino-Latin American Studies, 5(3), 129–131.

- Seidman, I. (2006). Interview as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Sheets, R.H., Flores, B. B, & Clark, E.R. (2011). Educar para transformar: A bilingual education teacher preparation model. In B. Bustos Flores, R. Hernandez Sheets, & E. R. Clark, (Eds.), Teacher preparation for bilingual student populations: Educar para transformar (pp. 9–24). New York: Routledge.

- Stewart, D.W., Shamdasani, P.N., Rook, D.W. (2007). Focus groups: Theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851.

- Urrieta, L. Jr., (2009). Working from within: Chicana and Chicano activist educators in Whitestream schools. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press.

- Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U.S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

- Valdés, G. (1996). Con respeto: Bridging the distances between culturally diverse families and schools--An ethnographic portrait. New York: Teachers College.

- Varghese, M., Morgan, B., Johnston, B., Johnson, K.A. (2005). Theorizing language teacher identity: Three perspectives and beyond. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 4(1), 21-44.

- Varghese, M. M. (2006). Bilingual teachers-in-the-making in Urbantown. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 27, 211–224.

- Villenas, S., & Deyhle, D. (1999). Critical race theory and ethnographies challenging the stereotypes: Latino families, schooling, resilience and resistance. Curriculum Inquiry, 29(4), 413–445.

- Villenas, S. (2002). Reinventing educación in new Latino communities. In S. Wortham, E. Murillo, Jr., & E. Hamman (Eds.), Education in the New Latino Diaspora (pp. 215–240). Westport, CT: Ablex.

- Villenas, S., & Foley, D. (2002). Chicana/Latino critical ethnography of education: cultural productions from la frontera. In R. R. Valencia (Ed.), Chicano school failure and success: Past present, and future (pp. 198–226). New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Villenas, S., Godinez, F.E., Delgado Bernal, D.D., & Elenes, C.A., (2006). Chicanas/Latinas building bridges: An introduction. In D. Delgado Bernal, C. A. Elenes, F.E. Godinez, & S. Villenas (Eds.), Chicana/Latina education in everyday life: Feminista perspectives on pedagogy and epistemology (pp. 1–9). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Weisman, E. M. & Hansen, L. E. (2008). Student teaching in urban and suburban schools: Perspectives of Latino preservice teachers. Urban Education, 43(6), 653–670.

- Zarate, M.E. (2007). Understanding Latino parental involvement in education: Perceptions, expectations, and recommendations. Los Angeles: The Tomas Rivera Policy Institute.

- Zentella, A. C. (1997). Growing up bilingual: Puerto Rican children in New York. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Zentella, A.C. (2005). Building on strength: Language and literacy in Latino families and communities. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.