Abstract

Over the past 35 years, language immersion programs have been steadily increasing in number throughout the U.S. The popularity of these diverse, linguistically complex educational programs has led to a rather extensive body of research on language immersion and dual language contexts. Research, however, has thus far focused primarily on the quantification of language use (the amount of target language versus first language use) in different settings and with different interlocutors. Very few studies have probed the interesting and significant sociolinguistic question of what students ‘do’ with languages in the classroom. The present study fills this research gap by investigating the communicative functions of student language use in full and partial Spanish immersion classrooms among kindergarten, first and second graders. Twelve hours of recorded spontaneous classroom speech were analyzed for communicative functions. The results show that contrary to the existing research, students in this classroom use Spanish for a wide variety of communicative functions. These findings suggest that previous depictions of the diglossic classroom speech community may be influenced by the concept of figured worlds (Holland et. al., Citation1998), whereby our imagined typical immersion classroom differs from the actual reality of student language use.

Introduction

Language immersion classrooms are characterized by the teaching of content (such as history, math, and literature) in two different target languages and have been steadily increasing in number throughout the U.S. for the past 35 years (Lenker & Rhoades, Citation2007). While specific features vary across programs, such as the students, context, and the division and amount of language instruction, these programs are most often differentiated by the one-way or two-way distinction. In one-way programs, all students are second language (L2) learners or foreign language learners of the target language; research has thus far focused mainly one one-way immersion (for a review, see Mackey, Citation2007 and Swain et. al., Citation2002). Two-way immersion programs, on the other hand, are characterized by a student population which includes both L2 learners of the target language and native or heritage speakers, who have learned the language of instruction as a home language. A second signification distinction is that of full immersion and partial immersion (or dual language) programs. In full immersion, the target language is the language of the instruction for the entire day. In dual language programs, content is taught in one language (Spanish) half of the day and another language (English) for the second part of the day. The language program under examination in the present study is a transitional program, meaning that at this school pre-K and kindergarten classes are full immersion while first through fifth grades are partial immersion, with half of the instruction in English and half in Spanish. The terms ‘full immersion’ and ‘partial immersion’ are used in this study in part due to the fact that students actually switch classrooms and teachers for the part of the day when they have English instruction. The popularity of language immersion along with its unique diverse, linguistic complexity has led to a rather extensive body of research over the years. The present study adds to the growing body of research on two-way immersion programs (for a review of the literature, see Howard & Sugarman, Citation2007).

Most early research on language immersion programs was informal, observational or anecdotal in nature (such as Blanco-Iglesias & Broner, Citation1993; Broner, Citation1991; Heitzman, Citation1993). When scholars acknowledged this tendency and the fact that it resulted in an “insufficient empirical basis on which to draw firm conclusions about the discourse characteristics of immersion classrooms and, therefore, about the impact of classroom interaction styles on language learning” (Genesee, Citation1991, p. 190), it set a strong research agenda for systematic research on actual language use in the immersion classroom.

Early informal observational and anecdotal research suggested that students used less of the target language throughout the years and especially in the upper grades (Blanco-Iglesias & Broner, Citation1993; Broner, Citation1991; Heitzman, Citation1993). Tarone & Swain (1992) responded to these reports with a sociolinguistic explanation that as a speech community, the immersion classroom naturally becomes increasingly diglossic over time, meaning that the students increasingly use certain language varieties (in this case, the majority language or target language) for distinct purposes, interlocutors, and settings. Tarone & Swain (Citation1995) base this claim on two sources of evidence: first, a 26 month long longitudinal study of an English as a second language (ESL) student in Australia, beginning when he was five years old (Liu, Citation1991, Citation1994), and secondly, an interview with an immersion program graduate (Swain, Citation1993). In the first case, it is important to note that the situation is distinct from that of a typical immersion language program. Nevertheless, in lieu of similar available research from immersion classrooms, Tarone & Swain (Citation1995) compare student-teacher and student-peer interactions for an ESL student ‘Bob’. They note that Bob uses a much more limited range of functions, mostly responsive, in conversation with the teacher, compared to conversations with peers which are overall more assertive and initiating including a much wider range of functions: commands, arguing, insulting and criticizing. In the second case, the graduate of an immersion program remarks on her lack of access to a target language vernacular, or informal language, for performing certain linguistic functions such as for saying, in the interviewee’s words, “Come on guys, let’s get some burgers” (Swain, Citation1993, p. 6). The researchers, in turn, speculate that the reason students use more of the majority language instead of the target language as they advance in their grade levels is their lack of access to the target language vernacular. This theory reveals a persistent concern related to the range of communicative functions of student language use in immersion classrooms and calls for further research along this line. While scholars have responded to the call for systematic research on language use in the immersion classroom, it has primarily led to the quantification of target language versus the majority language use by students, often separated and analyzed according to interlocutor (teacher versus peer) or setting (teacher-led versus small group). Research on the range of functions of student language use within the immersion classroom, on the other hand, has been vastly understudied.

The present study aims to fill this gap in the research through an ethnographic case study which forms a part of a large-scale, ongoing investigation on language use by students in a Spanish immersion program. The current paper focuses on the functions of language use by 30 Spanish immersion students from kindergarten, first and second grade classrooms, including 24 L2 learners of Spanish and 6 heritage language learners. The investigation itself included over 24 hours of participant observation in the classrooms, and the core dataset for this analysis includes 12 hours of spontaneous classroom speech which has been transcribed and coded. This study addresses the insufficient existing data on the actual purposes and functions of student language use in the immersion classroom, beyond the quantification of which language is used in certain settings and role relationships. The present study, thus, answers the important question: What do Spanish immersion students do with words? Insights into immersion students’ functional use of the target language and majority language within the classroom holds important implications for understanding language learning in this unique educational setting.

Literature Review

Language Use in the Immersion Classroom

Concern for systematic research on actual language use in the immersion classroom prompted much investigation over the past several decades. Up until this point, however, it has remained widely dominated by studies which quantify the amount of the target language and majority language spoken in the classroom. Beyond the mere quantification of language choice, scholars have sought to explore the influence of related factors including the individual’s language background (heritage speaker of target language v. L2 learner of target language), interlocutor role (teacher v. peer), interlocutor language background (L1 speaker of target language v. L2 speaker of target language) and classroom setting (small group v. large group instruction). A summary of the findings shows many similarities in addition to some notable discrepancies. While most studies demonstrate a general student preference for speaking the majority language (Potowski, 2004, 2007), some studies show that the student’s language background had an effect on language use (e.g., Ballinger & Lyster, Citation2011). Additionally, most research demonstrates a tendency for students to speak more of the target language with the teacher than with peers (Potowski, 2004). Speaking with heritage language speaker peers was alternatively found to enhance target language use (e.g., Panfil, Citation1995; Ballinger & Lyster, Citation2011) or demonstrate no effect (Potowski, 2004, 2007). This inconsistency reveals a need for more research into language immersion programs, given the fact that so many qualitative variables are at play. (See Ballinger & Lyster, Citation2011 for a detailed literature review of research in one-way and two-way immersion classrooms.)

Notably, studies focusing on the amount of each language used with whom in different contexts only reveal so much. For instance, it does not tell us what the students are saying or what they are in essence ‘doing’ with the words they use in the respective languages. It is for this reason that the present study on the communicative function of language use stands to make a considerable contribution to current understandings of language learning in the immersion classroom.

Functions of Language Use in the Immersion Classroom

While research on the functions of language use in the immersion classroom is sparse, there are a notable few. To my knowledge, only three articles have explored the functions of student language use in the immersion classroom, setting aside those which involve the functions of teacher talk (Kim & Elder, Citation2005; Legarreta, Citation1997). First, Broner & Tarone (Citation2001) present a unique analysis of a specific language function in the immersion classroom, dealing with two distinct types of language play. Their study makes an important contribution to the role of language play in language learning and the process of second language acquisition. However, it differs from a more general analysis of the broad range of functions for language use presented in the present study. Second, Dornyei & Layton (Citation2014) present a socio-cultural study of student language use which reveals that while students imitate teachers and translators’ language use in large group settings, small group settings include diverse multilingual discourses. The researchers particularly report that small group work demonstrated creative dialogues about language and identity. Last, Spezzini (Citation2010) investigates student patterns of language use among 34 12th graders from an English immersion school in Paraguay. The findings suggest a drop in the use of the L2 during structured activities in immersion classrooms as students progress to upper grades. Interestingly, Spezzini (Citation2010) did look at more specific functions of language use. For instance, she found that students reported using Spanish for emotions at a rate of 78% especially for strong emotions. For thinking and dreaming, the use of Spanish dropped to 60%. Thinking may have included academic purposes. For recreational reading a mixture of Spanish/English was reported at a rate of 27%, only Spanish was reported at a rate of 21% and for doing math only 17%. Significantly, all these findings are based on student self-reports which can give a certain type of knowledge only.

Of particular import the present study is research focusing on students whose L2 is Spanish, since this describes 80% of the students in this study’s corpus. In a sociocultural analysis of a one-way Spanish immersion classroom, Fortune (Citation2001) found that the students spoke Spanish 1/3 of the time, with more Spanish correlating with the proximity of the teacher, writing and math problem-solving and interlocutor. Broner & Tedick (Citation2011) found similar patterns of Spanish correlating with teacher proximity. They also found that Spanish use was more likely during instructional time, for on-task talk, and depending on task type and activity structure. These results confirm in part the language immersion classroom as diglossic but a qualitative analysis of classroom conversation and ‘languaging’ (Swain, Citation2000) depict language choice as highly complex.

Communicative Function

Although linguistics originally encompassed aspects of language use and language structure, the field was strongly impacted by Noam Chomsky’s (1965) abstract notion of linguistic ‘competence’ as idealized language inside the mind, which should be regarded more important than and entirely separately from ‘performance’. This resulted in a split in the field of linguistics which yielded a product tradition which focuses on language structure, and an action tradition which emphasizes language use (Clark, 1992). While the field continues to be dominated by primarily cognitive/mentalistic approaches, more recently scholars have called for social/contextual orientations (Firth & Wagner, Citation1997; Liddicoat, Citation1997). Integral to this change was Hymes’ (1972) coining of ‘communicative competence’ as an alternative to Chomsky’s ‘competence’. In addition to grammatical knowledge of a language, communicative competence emphasized the importance of the rules for appropriate use, or “communicative form and function in integral relation to each other” (Hymes, Citation1994, p. 12). Hymes went even further as to outline the ‘ethnography of speaking’ (1974), a methodology concerned with “situations and uses, the patterns and functions, of speaking as an activity in its own right” (p.16). Under the ‘ethnography of speaking’, a key concept set forth by Hymes is that of a ‘speech community’ which naturally includes a variety of speech styles and registers suitable for different contexts. Another important notion is that of ‘communicative function’ (Hymes, Citation1974) is a unit of analysis which recognizes the purposeful nature of linguistic interactions and focuses on patterns within the speech community. Instead of isolating one abstract linguistic code for study, Hymes (Citation1974) advocates investigating all varieties found within a speech community according to: 1) speech events, 2) constituent factors, such as sender, receiver, topic, setting, and 3) functions of speech events, in which the focus is the difference between/among communities. Hymes (Citation1974) outlines 7 broad types of function as follows: expressive, directive, poetic, contact, metalinguistic, referential, and contextual. For Hymes (Citation1974), the primary objective of the ethnographer is to determine which functions are being “encoded” and “decoded”, in other words, which functions are intended and perceived by participants (p.34). Around the same time, Austin’s (Citation1962) “How to Do Things with Words” was published based on a series of lectures and introducing the concept of “speech acts”. Searle (Citation1969) brought “speech act theory” into the realm of linguistics, further dividing Austin’s (1962) illocutionary act into 5 categories: representatives/assertives, directives, commissives, and declarations. Although the lists of “communicative functions” and “speech acts” are similar, “there are differences in perspective and scope which separate the fields of ethnography of communication and speech act theory” (Saville-Troike, Citation2003, p.13). The present study aligns most closely with Hymes’ ‘ethnography of communication’, but both fields have undeniably influenced the present analysis.

Methods

Setting and Participants

The present study took place in a two-way Spanish immersion program in Tucson, Arizona which offered Spanish, French and German immersion classes for children from preschool (age 3) through 5th grade at the time of the study. This school is an independent school requiring tuition, and although scholarships are available and utilized by a few students, the students are mostly mid-high socioeconomic status. At the school, the preschool and kindergarten classes are full immersion classes, and those students receive instruction in the chosen target language with the same instructor the entire day, excluding lunch, recess, and extra-curricular activities. This program is a transitional immersion program, since students transition from a full immersion to a partial immersion program. From first through fifth grade, the students switch to a partial immersion program where they Spanish is the language of instruction for half the day and students then switch classrooms and teachers for the second part of the day which is in English. In the Spanish immersion program, the instructors for the kindergarten, first and second grades were Peruvian. The study included 30 students from the kindergarten (4 female, 4 male), first grade (7 female, 4 male) and second grade (5 female, 6 male) classes. Of the 30 students in the study, 24 (12 female, 12 male) were L2 learners of Spanish and six (4 female, 2 male) were heritage speakers of Spanish students. The heritage speakers of Spanish were diverse, including two students who were born in Mexico, three who had a mother who was born in Columbia, and one who was born in Ecuador. In the kindergarten class, one heritage Spanish speaker was born in Mexico and one girl who was born in the United States and grew up in a bilingual home. The first grade class included only one heritage Spanish speaker, a female who was born to a Columbian mother in the United States and grew up in a bilingual home. In the second grade class, the three heritage Spanish speakers included one girl who was born to a Columbian mother in the U.S. and grew up in a bilingual home, one girl born in Ecuador, and a boy who was born in Mexico. It is important to note that the three children who grew up in bilingual homes were exposed to both English and Spanish at an early age and do not constitute English language learners, although the two boys from Mexico and the girl from Ecuador could be classified as English language learners with primarily English-speaking parents and experiences in Spanish-speaking countries.

Data Collection

For this study, I was involved in participant observation for 24 hours of student classroom time, both observing and assisting the instructor when possible. The corpus of data for the present analysis is 12 hours of transcribed audio-recorded data from the kindergarten, first and second grade classrooms. Several small microphones were placed at different ‘centers’ stationed around the rooms in order to record student speech. These recording were later combined and transcribed into a single transcription. Each recording and transcript represents an entire day of Spanish language instruction for the class. Notably, the kindergarten students were in their Spanish classroom for six hours while the first and second graders were in their classrooms for three hours each due to the aforementioned nature of the half day in English class and half day in Spanish class for the other grades.

Data Analysis

The unit of analysis employed was a turn of speech (Ellis, 1994; Levinson, 1983), defined as any time an interlocutor stopped talking or was interrupted by another interlocutor’s turn. Each individual code-switch was then coded based on 1) language background of the speaker, 2) language of turn (Spanish, English or Both), 3) grade level, 4) initiative v. responsive turn, and 5) communicative function. Bilingual turns were coded as ‘both’ for several reasons. First of all, there is substantial debate over what constitutes a code-switch; for instance, whether it may be a single-word switch or multi-word switch. Secondly, the present analysis focuses on the communicative function of turns of speech by language use. (See Christoffersen, 2014 for a detailed analysis of the discursive functions and grammatical patterns of code-switching by students in this setting.)

In performing the analysis of communicative function, the categories were influenced by the ‘ethnography of speaking’ (Hymes, Citation1974) and speech act theory (Searle, Citation1969); however, the resulting categories were created by the researcher based on major themes that emerged from the data. The categories of communicative function used in the present data analysis include: playing, positioning (blaming, arguing), evaluating/complaining, commanding/reprimanding, thanking/apologizing, joking, requesting, requesting information, and assertions (storytelling, answers, declarative statements). It is important to note that while function may coincide with a certain turn of talk, it often does not. Thus, in the coding of this data, many turns were coded with multiple functions. In other instances when no clear connection could be made to the outlined examples of communicative functions, no communicative function was coded for that turn of talk. Below is a series of examples of communicative function from the present study’s corpus according to the nine categories.

Playing

BETO: I am the police dog. [in a role play activity]

Positioning

JESSICA: Señora, Matthew está hablando en inglés.

Evaluating/Complaining CARLA: Yo tenía este seat. [when researcher sat down, having taken her seat]

Commanding/Reprimanding

JESSICA: Matthew, ¡no jugar!

Thanking/Apologizing

TARA: I didn’t mean to do that.

Joking

SEÑORA: ¿Qué color es el uniforme?

TARA: ¡Uniformio! [Says smiling]

Requesting

BRIANNA: After can I be it? [Asking to change roles in a role play game]

Requesting Information

BEN: Señora, ¿una placa es a badge?

Assertions

VICTOR: En norteamérica todos los policías son negros.

Results

The results of the present study are organized into three major sections: 1) a quantification of the general patterns of Spanish/English use, 2) an analysis of the communicative functions of language use, and 3) a qualitative analysis of communicative functions of language use. The first section provides an overall depiction of the classroom setting and patterns of language use broadly described, also allowing a point of comparison to the considerable body of research on the quantification of target language versus majority language use in the immersion classroom. The second section explores the communicative functions of student language use in the Spanish immersion classroom which adds a significant and widely understudied perspective. The third and final section describes in more detail the findings of communicative function of language use in the immersion classroom including specific examples from the present corpus and a possible explanation for the discrepancy with previous research.

Overall Patterns of Spanish/English Language Use in the Immersion Classroom

An investigation into the overall patterns of Spanish/English student language use in the Spanish immersion classroom provides an important general picture of the setting. It also affords a point of comparison to the large body of research which has already been conducted throughout the past couple decades quantifying L1 and L2 use in the immersion classroom. The overall patterns of Spanish/English use will be described by grade level and language background.

Overall language use by grade level. Research throughout the years has shown a tendency for students use less of the target language as they advance through grade levels (Blanco-Iglesias & Broner, Citation1993; Broner, Citation1991; Heitzman, Citation1993). As depicted in Table 1, the frequent use of Spanish in first and second grades (73.2%) may seem to confirm the findings of Blanco-Iglesias & Broner (Citation1993), who noted a peak in the use of Spanish during structured activities during second grade. It does not, however, follow their reported trend for a subsequent drop in Spanish language use in second grade (80.0%). Additionally, the high percentage of Spanish turns in all grades (34.4%, 73.2%, 80.0%, respectively) seems to question whether the classroom as a speech community becomes increasingly diglossic (Lee, Hill-Bonnet & Gillispie, Citation2008; Tarone & Swain, Citation1995) with a decreased use of the target language.

Table 1. Language use per turn across grade level.

Overall language use by language background. Since the immersion classroom under investigation includes both heritage speakers of Spanish and L2 learners of Spanish, it is appropriate as well to compare Spanish/English language use by language background. As might be expected, heritage speakers of Spanish speak more Spanish (75.0%), but Spanish also comprises a majority of the turns of talk by L2 learners of Spanish (44.1%), resulting in a sum of 51.6% of classroom conversational turns in the target language (Table 2). This suggests that while language background does influence language use, all students use more Spanish than English and turns including both English and Spanish. Also, there are more L2 learners of Spanish in the class than heritage speakers of Spanish, it is fitting that L2 learners would have more total conversational turns in the dataset (75.5%).

Table 2. Language use per student turn across language background.

Communicative Functions of Language Use in the Immersion Classroom

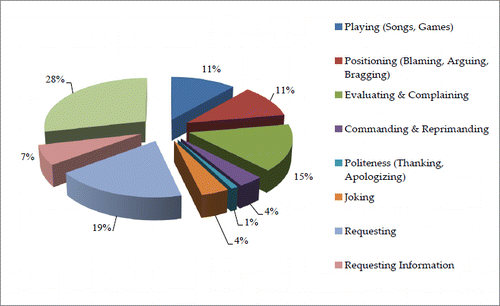

The major point of contribution of the present paper is the exploration of the communicative functions of student language use in the classroom. The categories of communicative functions which emerged from the data and were influenced by the ‘ethnography of speaking’ (Hymes, Citation1974) and ‘speech act theory’ (Searle, Citation1969) include: playing (games, songs), positioning (blaming, arguing, bragging), evaluating & complaining, commanding & reprimanding, politeness (thanking, apologizing), joking, requesting, and requesting information. The following section of results will be separating into analyses of communicative functions in the Spanish immersion classroom by language use, grade level, and finally an overall picture of the communicative functions used by students in the target language, in this case, Spanish.

Communicative Functions by Language. At first glance the results in the following table (Table 3) may seem rather predictable, given the fact that the most common communicative function for Spanish turns is assertions (37.8%), comprised mainly of answers to questions and requests (17.0%) mostly for asking permission from the teacher. The English turns seem to tell a similar story as the most common communicative function for English, playing (95.6%), does not seem surprising.

Table 3. Communicative function per student turn by language.

The interesting point here is that students continue to use Spanish, the target language, for a wide variety of functions (), contrary to what others have speculated (Tarone & Swain, Citation1995). For instance, Table 3 demonstrates that students use Spanish for evaluating/complaining (13.4%) and positioning (8.1%) for their third and fourth most common communicative functions of Spanish turns. This may be due to the fact Tarone & Swain’s (Citation1995) hypothesis was based on an ESL student in a classroom in a very different context (Liu, Citation1991, Citation1994) or that the reported findings from their immersion student graduate differed from reality (Swain, 1991). On the other hand, it may be related to the high degree of variability in contextual and social factors across immersion programs. It is certain that more research is needed in order to further explore this question.

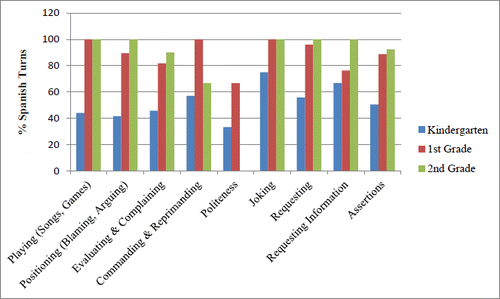

Communicative function by grade. Since several scholars have suggested that immersion classrooms may become increasingly diglossic as students advance through grade levels, it is also appropriate to analyze communicative function by grade level. The following chart () depicts the total Spanish turns by grade level, showing the breakdown by communicative function. Interestingly, the findings show no drop or dramatic change in communicative function for the Spanish language across grade levels. Instead, it shows that students in all grade levels use Spanish for a wide variety of communicative functions. A few exceptions include the fact that the dataset did not find any tokens of Spanish politeness for second graders; however, the students did not exhibit politeness in the dataset in English either. Secondly, the first graders seem to demonstrate a great preference for using Spanish for commanding and reprimanding. Since this is a cross-sectional study and not a longitudinal study, findings should be considered with caution, given the likelihood that differences in individuals and classes affect the results.

Qualitative Analysis of Communicative Function in the Immersion Classroom

Request, complaints, and evaluations. As depicted above (Table 3, , ), requests, complaints and evaluations are all among the top initiated L2 interactions in the Spanish immersion classroom. Common requests throughout the dataset included materials, food, water, and change in activities. Complaints were usually made about other students, while evaluations were opinionated comments on a wide range of topics.

This last example of an evaluation is particularly interesting, because the girls were whispering among themselves at their desk at a moment who they should have been listening to a poetry presentation. This demonstrates how students in this classroom speech community construct their own spaces for using the target language for a wide variety of functions.

Commands, arguments, and insults. Furthermore, students command, argue and insult in their L2 with their classmates.

None of these target language utterances contain informal target language forms, but instead students are modifying academic language in order for it to serve an informal function. For instance, here “bebé” can take on a new meaning, and students have learned that “mira” can be both instructional, as in the command example, and emphatic, as in the argument example.

Informal teacher/student interactions in L2. Additionally, quite frequently these informal initiative interactions occur between teacher and student.

The teacher involvement in student initiated L2 interactions is a significant indication of the reason why students may use the target language for a wide variety of functions in this school. Additionally, the following depiction of Spanish immersion kindergarten instructor’s teaching philosophy sheds light on the situation.

Kindergarten Instructor: [Quiero] que [los niños] sientan que yo soy parte de ellos, que yo juego con ellos, que yo los quiero. Entonces no que me vean a mi como una figura muy arriba y yo abajo, no. Yo soy parte de ellos. Y yo creo que esta es la diferencia en que ellos se sientan ansiosos para aprender, de venir a la escuela, de querer aprender.

I want [the children] to feel that I am a part of them, that I play with them, that I love them. So, not that they see me like a figure who is very high and I below, no. I am a part of them. And I believe that this is the difference that makes them feel anxious to learn, to come to school, to want to learn.

An egalitarian philosophy of teaching where neither is “very high” or “below” may be a reason for the students’ use of the target language for a wide variety of contexts and functions. Future studies on the impact of school philosophies would be useful to clarify the impact of school and individual instructor philosophies of education on the communicative functions of student target language use.

Unimagined functions and forms in the immersion classroom. According to popular critiques of immersion schools (Tarone & Swain, Citation1995), students in such programs exercise a limited range of functions in the target language. Expected functions of student target language use may commonly include requesting (such as permission), requesting information (asking questions), and assertions (answering questions). However, these noticeably comprise only 54% of the total communicative functions of Spanish turns from the present dataset. So, the remaining 46% of communicative functions in Spanish are unanticipated uses of the target language within the Spanish immersion context. This contrast may be due to the notion of figured worlds presented by Holland et. al. (Citation1998). The figured worlds construct would argue that these alternative communicative functions of the target language use do not fit with our imagined or figured world of a typical classroom. We do not at first envision arguments, jokes and complaints as a part of the classroom.

Positioning [Argument about a missing pencil box]

ERIC: Ella tiene el pencilbox. Hide it aqui. Mira.

She has the pencilbox. Hide it here. Look.

SARA: Pero no es en aqui. ¡Mira!

But it is not here. Look!

Evaluating [Side conversation about Littlest Pet Shop toys]

NATALIE: Me gusta este.

I like this.

LYDIA: Esta como aliens.

This like aliens.

NATALIE: Yo creo es cuddlebugs.

I think it is cuddlebugs.

These examples depict how students use Spanish and Spanish/English to discuss or argue over common occurrences during the school day, yet these forms of discourse are often not acknowledged within the immersion classroom. Instead of acknowledging certain functions of language use within the classroom, all forms and functions of language must be recognized in classroom research in order to give a comprehensive overview of language use in the immersion classroom.

Conclusion

The present study has contributed to the growing body of research on two-way immersion programs, especially with its unique endeavor to discover what students “do” with words through an investigation of communicative function. First, the paper presented an analysis of overall patterns of language use in the kindergarten through second grade Spanish immersion classrooms. An analysis by grade level differed from other research in showing a steady increase in the amount of Spanish conversational turns from kindergarten through second grade. Additionally, all grade levels demonstrated a high percentage of Spanish use, which brings into question whether there is a drop in L2 use as students progress through grade levels in all immersion programs, as has been previously reported (Broner, Citation1993). Furthermore, the present study found that while heritage speakers of Spanish use more Spanish in the classroom, L2 learners of Spanish use more Spanish than English.

The investigation of communicative functions of language use in the immersion classroom elicited the greatest contribution, since until this point there has not been a similar study on overall communicative functions of language use by students in language immersion programs. The top two communicative functions of Spanish turns in the classroom were rather unsurprising: assertions (37.8%), commonly answers to questions, and requests (17.0%), usually students asking permission. Similarly, the top communicative function for English turns was playing (95%), which is an expected choice for students in a society where English is the majority language. Interestingly, though, students did use the target language, Spanish, for a wide variety of functions including evaluating/complaining (13.4%) and positioning (8.1%), or blaming and arguing. There was no significant change in communicative functions for Spanish across grade levels, which provides a different perspective from previous claims that the immersion classroom becomes increasingly diglossic over time (Tarone & Swain, Citation1995). However, it is significant to note that the findings may well be impacted by the impact of gender, race, ethnic community involvement, parent’s English proficiency, and income among other factors (Lutz, Citation2006). Further research is needed to examine communicative functions of language use as correlated with these significant social factors, and it is important to note that the differences in patterns of language use can be expected in different classrooms. Furthermore, as Achugar (Citation2008) notes a stronger linguistic marketplace for Spanish in a Southwest Texas border town, this elite bilingual program may attribute significantly to the social capitol ascribed to Spanish and its use across various communicative functions.

Lastly, a qualitative analysis of communicative function in the classroom reveals that students use the L2 or target language for a wider variety of functions than may be expected. The difference between the expectation and the observed findings from this systematic investigations may be explained by the notion of “figured or imagined worlds” (Holland et. al., Citation1998). The “figured worlds” construct would suggest that some communicative functions, such as arguments, jokes or complaints, do not fit with our imagined or figured world of a typical classroom. Therefore, previous mostly anecdotal and observational research may not have acknowledged the entirety of student language use and hence the breadth of students’ communicative competence. Moreover, an interview with a Spanish immersion teacher demonstrated the instructor’s egalitarian perspective on the teacher/student relationship with no one in the classroom “very high” or “very low”; the teacher stated “I am part of them.” This demonstrates the influence of individual teacher philosophies on student language use in the immersion classroom, revealing the importance of a large body of studies from a diverse group of immersion programs in order to gain a better understanding of language learning in this educational setting.

Pedagogical Implications

While the findings of this study are of great import, there is another significant aspect of the current research endeavor. This project carries with it the hopes to shift our perspective on immersion student language use. While use of the target language is vital for language learning, we should also seek to realize that we need not focus solely on the amount of target language use by the type of target language use. As Hymes (Citation1974) argued decades ago, we should seek to emphasize student development of “communicative competence” in which they gain not only grammatical knowledge of the target language but also the ability to employ that language appropriately for a variety of functions and settings. For example, teachers could develop writing tasks that are not only formal essays but emails, chat messages, text messages and posts on social media. The class could also use Spanish audio and video clips from movies and cartoons using vernacular or slang and discuss these different types of speech and their use.

Furthermore, if we are to consider the language immersion classroom as a speech community, we need to recognize learners as actively constructing rules for appropriate use of their languages. Teachers could conduct action research in their classrooms, listening to ‘what students do with words’, the functions of language use and the languages used for those purposes. These insights gained from specific classroom speech communities would allow teachers to determine the needs of their students.

References

- Achugar, M. (2008). Counter-hegemonic language practices and ideologies: Creating a new space and value for Spanish in Southwest Texas. Spanish in Context, 5 (1). 1–19.

- Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ballinger, C. & R. Lyster. (2011). Student and teacher oral language use in a two-way Spanish/English immersion school. Language Teaching Research 15 (3), 289–306.

- Blanco-Iglesias, S., & Broner, J. (1993). Questions, thoughts and reflections on the issues that pertain to immersion programs and bilingual education in the U.S. and in the Twin Cities, MN. Unpublished manuscript, University of Minnesota.

- Broner, J. (1991). Report on observations on the use of Spanish at an immersion school. Unpublished manuscript, University of Minnesota.

- Broner, M. & E. Tarone. (2001). Is it fun?: Language play in a fifth-grade immersion classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 85 (3), 363–379.

- Broner, M. & Tedick, D. (2011). Talking in the fifth grade classroom: Language use in an early, total Spanish immersion program. In D. Tedick, D. Christian, & T. Fortune (Eds.), Bilingual Education and Bilingualism: Practices, Policies, Possibilities (pp. 166–186). Bristol, GBR: Channel View Publications.

- Dornyei, L. & A. Layton. (2014). “¿Cómo se dice?” children’s multilingual discourses (or interacting, representing and being) in a first-grade Spanish immersion classroom. Linguistics and Education, 25, 24–39.

- Firth, A. & J. Wagner. (1997). On Discourse, Communication, and (Some) Fundamental Concepts in SLA Research. The Modern Language Journal, 81 (3): 285–300.

- Fortune, T. (2001). Understanding immersion students: Oral language use as a mediator of social interaction in the classroom. PhD thesis. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

- Genesee, F. (1991). Second language learning in school settings: Lessons from immersion. In A. Reynolds (Ed.), Bilingualism, Multiculturalism, and Language Learning: The McGill Conference in Honor of Wallace E. Lambert. Cambridge, MA: Newbury House.

- Heitzman, S. (1993). Language use in full immersion classrooms: Public and private speech. Unpublished undergraduate summa thesis, University of Minnesota.

- Holland, D., Lachicotte, W., Skinner, D. and Cain, C. (1998) Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Howard, E. R., & Sugarman, J. (2007). Realizing the vision of two-way immersion: Fostering effective programs and classrooms. Washington, DC/McHenry, IL: Center for Applied Linguistics/Delta Systems, Co.

- Hymes, D. (1974). Ways of speaking. In Bauman & Sherzer (Eds.) Explorations in the Ethnography of Speaking (pp. 433–451). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hymes, D. (1994) Towards ethnographies of communication. In J. Maybin (Ed.), Language and literacy in social practice (pp. 11–22). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Kim, S. & C. Elder. (2005). Language choices and pedagogic functions in the foreign language classroom: A cross-linguistic functional analysis of teacher talk. Language Teaching Research 9 (4). 355–380.

- Lee, J., L. Hill-Bonnet, & J. Gillispie. (2008). Learning in two languages: interactional spaces for becoming bilingual speakers. The International Journal of Bilingual Education & Bilingualism, 11 (1). 75–94.

- Legarreta, D. (1997). Language choice in bilingual classrooms. TESOL Quarterly 11 (1), 9–16.

- Lenker, A. & N. Rhodes. (2007). Foreign language immersion programs: Features and trends over 35 years. CAL Digest, Feb.

- Liddicoat, A. (1997). Interaction, social structure, and second language use: a response to Firth and Wagner. The Modern Language Journal, 81 (3). 313–317.

- Liu, G. (1991). Interaction and second language acquisition: A case study of a Chinese child's acquisition of English as a Second Language. Unpublished doctoral dis-sertation, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia.

- Liu, G. (1994). Interaction and SLA: A case study. Unpublished manuscript, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia.

- Lutz, A. (2006). Spanish-speaking among English-speaking Latino youth: The role of individual and social characteristics. Social Forces, 84 (3). 1418–1432.

- Panfil, K. (1995). Learning from one another: A collaborative study of a two-way bilingual program by insiders with multiple perspectives. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA.

- Mackey, A. (2007). Conversational interaction in second language acquisition: A series of empirical studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Saville-Troike, M. (2003). Ethnography of communication: an introduction. (3rd ed.) Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Spezzini, S. (2010). English immersion in Paraguay: Individual and sociocultural dimensions of language learning and use. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7 (5), 412–431.

- Swain, M. (1993). Interview with Suzannah. Unpublished manuscript. OISE, Toronto, February 3, 1993.

- Swain, M., Brooks, L. & Tocalli-Beller, A. (2002). Peer-peer dialogue as a means of second language learning. Annual Review of Applied Lingusitics, 22, 171–185.

- Swain, M. (2000). French immersion research in Canada: Recent contributions to SLA and applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20. 199–212.

- Tarone, E., & M. Swain. (1995). A sociolinguistic perspective on second language use in immersion classrooms. The Modern Language Journal, 79 (2), 166–178.