ABSTRACT

This study was conducted in Lake Hawassa catchment, Ethiopia where policy programs are aiming to restore degraded lands with participation of local stakeholders. We assessed the system in relation to natural resource management and degradation using the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) conceptual framework and conducted a stakeholder analysis to understand stakeholder interest, influence and interactions amongst the different categories of stakeholders. Data were collected using key informant interviews, field observation and a literature review. Results indicate that the degradation of natural resources in the catchment is attributed to several interlinked socio-economic and biophysical factors. Identified stakeholders include government and non-governmental organizations, local administrative bodies, civil society, the private sector and farmers. Most of the stakeholders have a role in landscape restoration, have similar interests and strategic options, and are flexible and innovative. Moderate to pronounced trust exists among identified stakeholders and could provide an opportunity to achieve better coordination and collective action amongst the different stakeholders. However, considerable differences between stakeholders in power, power resources and influence were detected due to differences in access to information, communication and negotiation skills, practical relevance, and social relations. The costs for empowerment measures could be low, as many of the stakeholders have access to and control of resources and high level of basic competencies. Our findings could guide practitioners and policy makers on whom and how to engage when planning and implementing natural resources management and landscape restoration interventions at catchment level.

EDITED BY:

Introduction

Stakeholder analysis can be defined as a methodology for gaining an understanding of a system, and for assessing the impact of changes to that system, by means of identifying the key stakeholders and assessing their respective interests (Reed et al. Citation2009). Stakeholder analysis has considerable value in assisting researchers and practitioners working across different disciplines to take account of potentially conflicting objectives of efficiency, equity, and sustainability (Richards et al. Citation2004; Talley et al. Citation2016; Sterling et al. Citation2017). Nuga et al. (Citation2009) and Grimble and Chan (Citation1995) showed that stakeholder analysis helps to distinguish between conflicts (i.e. competition and potential disagreement between two or more stakeholder) and trade-offs (i.e. conflicting objective within a single stakeholder).

Different disciplines use stakeholder analysis for different purposes (Reed et al. Citation2009). For example, policy analysts use stakeholder analyses to understand how information, institutions, decisions, and power shape policy agendas for interest groups in social networks (Brugha and Varvasovsky, Citation2000; Mulyaningrum et al. Citation2013). In political science, stakeholder analysis is used as a mechanism for effective engagement of stakeholders, ensuring transparency, understanding the policy context, and identifying future policy options (De Bussy and Kelly Citation2010). The application of stakeholder analysis in natural resource management (NRM) has largely stemmed from concern that many projects have not met their stated objectives because of non-co-operation or even opposition from key stakeholders, who believed they would be adversely affected by change (Grimble Citation1998; Pain Citation2004; Prell et al. Citation2009; Talley et al. Citation2016).

In NRM, stakeholder analysis has focussed on identifying and characterizing stakeholders, grouping the stakeholders based on their influence and interest, mapping the relationships between stakeholders, and understanding their potential for developing alliances (Nuga et al. Citation2009). Stakeholder analysis in NRM projects has often focussed on inclusivity, being used to empower marginal groups, such as women, those without access to well-established social networks, the under-privileged, or the socially disadvantaged, and those who are not easily accessible (Johnson et al. Citation2004). Such focus of stakeholder analysis in NRM could arise from the need to minimize the dominance of powerful and well-connected stakeholders in decision-making over marginalised groups; a problem that is especially acute where there is increasing resource scarcity and where unsustainable use of common property resources are a concern (Global Water Partnership Citation2017).

Stakeholder analysis recognizes the different interest groups involved in the utilization and conservation of natural resources and provides tools that help to identify and resolve trade-offs and conflicts of interest (Barrow et al. Citation2002; Richards et al. Citation2004; Prell et al. Citation2009). It also helps to capture the dynamic nature of stakeholder needs, priorities, and interests throughout the duration of the project and beyond. According to Freeman (Citation1984) and Groenendijk (Citation2003), stakeholders include all actors or groups who affect and/or are affected by policies, decisions, and actions of a project.

In the context of NRM in Ethiopia, the key stakeholder groups vary from formal or informal groups of male or female farmers to government bodies or non-governmental organisations (NGOs), international agencies and multinational companies (Belay and Woldeamlak Citation2013; Vogler et al. Citation2017). Linkages between various stakeholders involved in NRM in Ethiopia usually demonstrate a top-down approach, more focused on command and control systems than being participatory (Zeleke et al. Citation2006). This could arise from the government ambition of achieving quick solutions rather than sustainability, quantity rather than quality, area coverage rather than impacts (Zeleke et al. Citation2006).

However, experience and lessons from previous studies (e.g. Chan and Singh Citation2000; Lamelas Citation2000; Otuokon Citation2000; Blomquist Citation2009) indicate that natural resource use and management displays complexity (i.e. involve a wide range of issues and actors that are constantly changing); uniqueness (i.e. each situation is unique and requires an understanding of local conditions and realities); and requires participation (i.e. the various stakeholders must be part of the decision making and management processes).

In contrast to the complex conditions related to the use and management of natural resources in the Lake Hawassa catchment, the study area, practitioners follow a top-down approach when planning and implementing NRM interventions. However, halting the degradation of natural resources and the associated impacts, as well as sustaining the benefits of NRM efforts require a) understanding and management of the complex relationships between humans and the resources they depend upon, b) tailoring of responses to specific needs and conditions, and c) participatory approaches to be followed. Against this background, this study employs the procedures or steps of stakeholder analysis provided by Reed et al. (Citation2009) to a) understand the system related to land degradation and NRM in the Lake Hawassa catchment, b) identify stakeholders involved in NRM, and c) understand stakeholders’ interests, priorities and power as well as interactions amongst stakeholders. The overall objective of the study was to enhance the understanding of how to improve the effectiveness of landscape restoration initiatives and the implications for future restoration activities and mechanisms for addressing constraints of stakeholder engagement. To achieve the specific and overall objectives, the study aimed at addressing the following research questions a) how are the livelihoods of the local communities influenced by land degradation and associated loss of ecosystem services? b) do the stakeholders involved in managing natural resources diverge in their mission, interest and strategic options? c) how do power and power resources influence the contribution of a stakeholder to managing natural resources? d) how can trust building amongst stakeholders be improved? and (e) are empowerment measures needed to better manage natural resources in the Hawassa catchment?

Materials and method

Study area

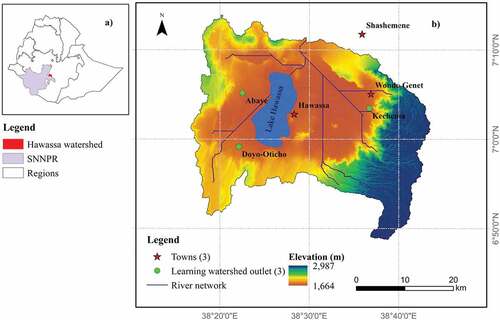

The present study was conducted in the Lake Hawassa catchment located at 6◦45ʹ to 7◦15ʹ North and 38◦15ʹ to 38◦45ʹ East latitude and longitude, respectively (Belete et al. Citation2017). Lake Hawassa is a closed freshwater lake located within the Ethiopian Rift Valley (). The catchment crosses the Southern Nation, Nationality Peoples Region (SNPPR) and the Oromia region. It has an area of approximately 1,250 km2 of which the waterbody is about 7%. Elevation in the catchment varies between 1,660 and 2,980 m above mean sea level. The average slope of the catchment estimated from a 30 m resolution Digital Elevation Model is 12%. The mean annual rainfall (for the years 1981 to 2010) is 969.6 mm (Ademe et al. Citation2020), and the mean maximum and minimum air temperatures are 30°C and 17°C, respectively (Zenebe Citation2014).

Mixed crop-livestock farming, and agroforestry systems are the dominant livelihood systems in the catchment (Zenebe Citation2014). Maize (Zea mays) is the dominant staple crop in the area followed by Enset (Ensete ventricosum) and tef (Eragrostis tef). Cattle, sheep and goats, and equines are the main livestock reared in the area.

Like other parts of the Ethiopia highlands, the Lake Hawassa catchment has experienced severe land degradation (Zenebe Citation2014; Tiki et al. Citation2015). Both anthropogenic and natural direct drivers such as deforestation, uncontrolled grazing, inappropriate agricultural practices, and climate change are causing land degradation (Zenebe Citation2014; Tiki et al. Citation2015). This has led to reduced water availability, siltation of water bodies and food insecurity (MoWR Citation2009; Elias et al. Citation2019). In response to the problem of land degradation, the Ethiopian government launched in 2010 a community-based watershed development program that aimed to double agricultural productivity through improving the management of natural resources and agricultural lands. Following the launch of the program, the regional bureaus of agriculture, district agricultural offices, and other local administrative bodies mobilized farmers to help with the construction of soil and water conservation measures in the catchment.

However, participation of local communities in community-based watershed development has been inconsistent across stages of implementation and exhibited top-down approaches (Tadesse et al. Citation2018). Government authorities and NGOs use their authority to decide how local communities should participate in the interventions. They often prefer consultation, a somewhat passive form of participation (Biggs Citation1989) which involves seeking public opinion on the interventions they have already designed. In most cases, community participation was limited to contributing labor, skill, farm implements, construction materials, seeds, and seedlings. This form of engagement is problematic in that it does not consider the complex and dynamic nature of NRM, the importance of understanding local conditions and realities and the participation of various stakeholders in decision making and management processes.

Study design

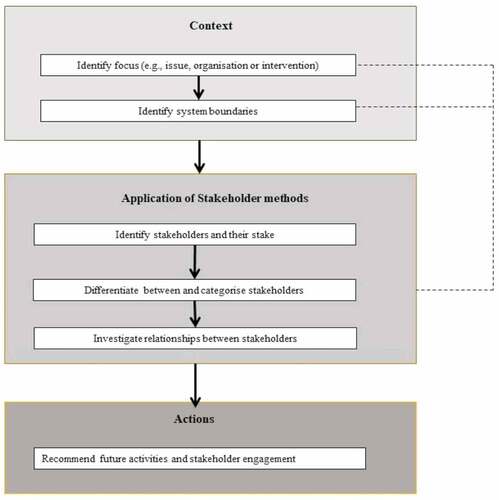

We followed the three basic stages of conducting stakeholder analysis as discussed by Reed et al. (Citation2009) (). In the first stage of the analysis, we set issues (i.e. landscape degradation and restoration) and delineated the system boundaries using hydrological criteria (i.e. based on the location of the main and sub-outlets of Lake Hawassa catchment). The second stage of the analysis focused on identifying key stakeholder groups relevant to the implementation of landscape restoration measures. The selection criteria were based on considering all those groups who, in some way, will be affected by the implementation of catchment restoration measures. This included those who have interests, claims or rights (ethical or legal) to the benefits of the restoration efforts, or to some measure are likely to bear its costs or adverse impacts. Also, this stage focused on investigating stakeholder characteristics and circumstances, interest, influence, power and power resources, and forms of interaction between different groups of stakeholders, including conflict, co-operation, and dependency. The final stage focused on drawing and synthesizing lessons and suggesting future activities and mechanisms for addressing constraints of stakeholder engagement.

Figure 2. Stages used in conducting stakeholder analyses (adapted from Reed et al. Citation2009)

Data collection

The data collection process employed key informant interviews, literature review and participatory transect walks and observations (). Data were collected from June to December 2019. We conducted 26 key informant interviews with people who are familiar with the issue (i.e. land degradation and the restoration of degraded landscapes in the catchment). The key informant interviews were conducted using informal and semi-structured questionnaires (see supplementary material – 1). The key issues covered during discussions, and linked objectives and research questions are summarized in . The key informants represented a range of governmental organizations, NGOs, the private sector and civil society, expertise from diverse fields and local communities. The respondents were anonymous, and the information provided was reported as an opinion of the organisation/institute.

Table 1. Methods of data collection, issues discussed, searched, and observed as well as linked objectives and research questions

We also consulted the literature (both published and unpublished) (). Relevant literature was collected from June to December 2019 using computerized searches of online databases including science direct, Scopus, and CAB abstracts.Footnote1 More than 30 peer-reviewed papers published in the past two decades were reviewed using the guideline suggested to search, collect and organize literature (Hart Citation2001). The terms used to search for literature separately and in combination include ‘stakeholder analysis’, ‘natural resources’, ‘community engagement’, ‘stakeholders power and power resources’, ‘participation’, ‘trust building’ ‘stakeholders’ interest in NRM’, ‘stakeholders’ influence’, and ‘interactions among stakeholders’. The initial screening resulted in more than 60 articles focused on stakeholder analysis for NRM in Ethiopia and elsewhere in the world. Further screening of the articles was conducted using the criteria peer-reviewed articles published from 2000 to 2019 to reduce the number from 60 to 30. The reviewed literature employed diverse methodologies including quantitative and qualitative approaches to undertake stakeholder analysis for NRM. We organized and analysed the information in the reviewed literature based on the main thematic areas including items such as challenges of land degradation, drivers of land degradation, landscape restoration, decision-making processes, stakeholders’ interest, priorities, influence, and power and power resources.

Further, we conducted participatory transect walks and observations to triangulate results from key informant interviews and literature, and to better understand the issues in the catchment (). A group of experts from district-level agricultural offices and members of the community watershed team participated during transect walks and field observations. We conducted the transect walks and observations in three watersheds in the study area following pre-determined routes starting from the upstream areas. During the walks, we took notes of all vital information gathered () as well as photographs to document the state of the environment.

Data analysis

We used the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) conceptual framework to understand the drivers of land degradation in the Hawassa catchment and linkages amongst the diverse drivers (Díaz et al. Citation2015). We used this framework because it enables substantial understanding to be acquired of both the ecological and the social systems involved. This in turn, supports decisions on when and how to intervene to reverse land degradation through landscape restoration.

Qualitative data gathered through key informant interviews and participatory transect walks were analysed using content analysis (Hsieh and Sannon Citation2005; Bernard Citation2006; Elo and Kyngas Citation2008). For qualitative analyses, the authors developed a coding scheme based on the main thematic areas including items such as challenges of land degradation, drivers of land degradation, landscape restoration, decision-making processes, stakeholders’ interest, priorities, influence, and power and power resources. Then, deductive coding was employed using codes such as land degradation severity, types of drivers, impacts (both biophysical and socio-economic), participation level, stakeholders’ interactions, factors affecting stakeholders influence and trust building. During the coding process, more codes were added when new issues emerged from the textual data. In addition, codes were merged, removed, or modified to avoid repetition and resolve disagreements between codes.Footnote2

We conducted stakeholder analysis using tools outlined by Zimmermann and Claudia (Citation2007), based on three dimensions of power related to compulsion – actors’ access to natural and anthropogenic (e.g. knowledge) resources; exclusion – actors’ ability to shape institutional structures; and influence – actors’ ability to shape the goals, aspirations, values and knowledge systems (Lukes Citation1974). Accordingly, we conducted stakeholder mapping, and analysed the stakeholders’ power and power resources, interests and scope for action, influence and involvement, trust, and exclusion and empowerment.

Stakeholder mapping was done to visualise the stakeholders relevant to NRM, and thereby characterise the relationships between stakeholders and the respective networks. The mapping of the stakeholders involved the identification of stakeholders, graphic representation of identified stakeholders (i.e. representation of relationships between the stakeholders in diagrammatic form), and the description of stakeholder profiles as outlined by Zimmermann and Claudia (Citation2007), i.e. describing the stakeholders in terms of agenda (i.e. mandate or mission), arena (field of action and/or scope of influence) and alliance (relationships with other stakeholders) and strategic options. The description of the strategic options of the identified stakeholders was done using ten criteria presented in Zimmermann and Claudia (Citation2007). These were development vision, operational effectiveness, flexibility and innovation, contractual fidelity, communication, relationships, management, trust, conflicts, and capitalising on experience.

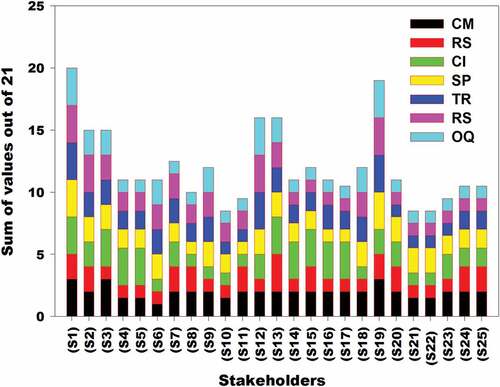

We analysed power and power resources to visualize the differences among stakeholders in terms of power and influence and identify options for action to change power relations. Based on Zimmermann and Claudia (Citation2007), our analysis focused on two aspects a) the stakeholders’ legitimate power, which is based on seven key types of authorities (setting objectives, norms and quality control (OQ), allocating or denying resources (RS), defining roles, tasks and responsibilities (TR), structuring the participation in decision-making processes (SP), controlling access to information and knowledge (CI), allocating rewards, recognition and sanctions (RS), and channelling messages to superiors and external bodies (CM)) and b) power resources (such as power derived from information (IN), communication and negotiation (CN), specialist knowledge and expertise (KE), practical relevance (PR), creativity (CR) and social relations (SR)).

We analysed the stakeholders’ interest and scope of action following the tools presented in Zimmermann and Claudia (Citation2007) to describe their interests in relation to land degradation and restoration and identify behavioural constraints and stakeholder scope for action. This analysis aimed at assessing whether the interest of the stakeholders and the assertion of stakeholder interests were likely to impact the use and management of natural resources.

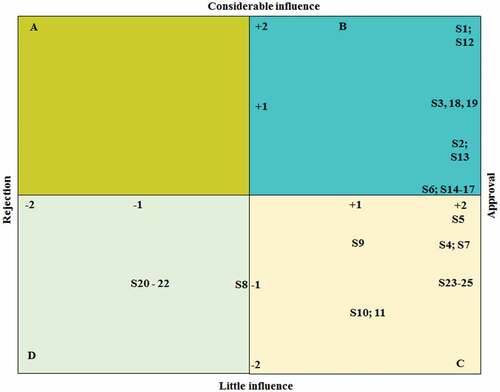

We assessed the stakeholder influence and involvement towards the use and management of natural resources. The key questions answered through this analysis concerned (a) stakeholder attitude to the use and management of natural resources (i.e. how stakeholders see land degradation and the efforts of restoring degraded landscapes and whether they have a predominantly negative attitude towards it or are predominantly in favour of the ongoing interventions), (b) stakeholder influence on achieving all project activities under consideration in the catchment (i.e. whether they are key stakeholders or just passive players).

We analysed trust building to investigate the degree of trust that exists between stakeholders, discussing options for strengthening the cooperation network and analysing specific stakeholder relationships. We analysed exclusion and empowerment to identify disadvantaged and marginalised stakeholders and discussed empowerment strategies. This analysis employed two indicators (Zimmermann and Claudia Citation2007), (a) access to and control of resources and (b) basic competencies of the stakeholder.

The definition of some of the words, terms or phrases used in data collection and analysis are summarized in .

Table 2. Definition of some of the words used in data collection and analysis (adapted from Zimmermann and Claudia Citation2007; Matti Citation2009)

Results and discussion

Context: drivers of land degradation and decision-making environment

All the key informants interviewed perceived that pressure on natural resources in the Hawassa catchment is increasing. They mentioned several direct anthropogenic drivers, such as land use and land cover changes, deforestation, overgrazing, unsustainable management of natural resources, and poor waste disposal facilities. Also, the key informants indicated several local and national level indirect drivers of land degradation. These include increased demand for fuelwood, population growth, limited livelihood options for diversification, inadequate knowledge and capacity, lack of policy enforcement, intense resource competition among public and private sectors and local communities, lack of principles and guidelines to manage natural resources, youth unemployment, and lack of coordination between the different technical sectors while implementing public investments.

Results obtained from the majority (95%) of key informants and field observations indicated that these drivers of land degradation are complex and interrelated. For example, increased demand for fuelwood and local community dependence on forest resources for livelihoods aggravate deforestation. The growing demand for fuelwood and agricultural land is attributed to population growth, which in turn is driven by several factors including a) failure to implement family planning programs, b) local communities need to have large families to support the predominantly subsistence agriculture, c) lack of awareness creation programs on the relationships between population growth and NRM, and d) limited livelihood options and diversification that can reduce pressure on the natural resource base. Overgrazing is mainly linked to shortage of alternative sources of livestock feed, higher numbers of livestock and lack of appropriate management plans. Inadequate livelihood diversification in the catchment and low productivity of the agricultural system also lead to sand mining (mainly for selling sand), which consequently leads to soil erosion and gully formation (). The failure to properly manage the natural resource base is attributed to the limitation in the information (knowledge) base related to NRM, lack of adequate implementation capacity and lack of dissemination of the available best practices. The low agricultural productivity is also attributed to knowledge and capacity gaps, loss of soil fertility, shortage of agricultural inputs, unsustainable agricultural practices and poor linkage between extension and research systems.

Figure 3. Gully erosion in the catchment dissecting agricultural lands and villages (Photo credit: Wolde Mekuria and Amare Haileslassie)

The majority (90%) of the key informants further explained that decisions on the use and management of natural resources is usually made by the Bureau of Agriculture. Local communities are usually consulted assuming that they agree on the plan. Other government institutions, such as the research and university systems, are involved in generating knowledge on best practices and impact of restoration measures, and in demonstrating and scaling up selected best practices. These institutions influence practitioners and decision makers through provision of advice based on research outputs. Non-governmental organizations usually provide technical and financial support during planning, implementation and monitoring and evaluation of NRM interventions. Discussions with key stakeholders revealed that the decision-making environment in the catchment is rated as medium, and that the poor research-extension linkage, political commitments of development agents and other practitioners, and the lack of capacity, livelihood diversification mechanisms and alternative energy options are the key areas that need attentions to restore the system.

These findings agree with the suggestion in the IPBES conceptual framework that land degradation is a consequence of both direct and indirect drivers (Díaz et al. Citation2015). Nelson et al. (Citation2006) also demonstrated that indirect drivers of change are drivers that cause alteration of the rate at which direct drivers cause land degradation, and impact ecosystem services and nature’s contributions to people. The IPBES framework also argue that there is a strong link between people and nature and that the decisions made by society, whether influenced by leaders in the public or private sector, and the influence of those decisions on human behaviour has major consequences for nature and nature’s contributions to people. According to Nelson et al. (Citation2006), the consequences are usually severe for vulnerable communities, particularly rural populations, and the poor in the Lake Hawassa catchment, who depend directly on nature for essentials, such as food, timber and water.

Other studies (e.g. Eshete Citation2009; Zenebe Citation2014; Giweta and Worku Citation2018; Elias et al. Citation2019) have demonstrated similar findings in that land degradation in the sub-catchments of Hawassa catchment is caused by several factors and are affecting the environment and livelihoods of local communities. For example, a study by Elias et al. (Citation2019) indicated that ecosystem services and biodiversity are under pressure from increased population growth, unsustainable developmental activities, unplanned urbanization, agricultural expansion, climate change, and the associated changes in land use and land cover. A study by Zenebe (Citation2014) showed that the factor most threatening degradation in the Hawassa catchment is gully erosion due to vegetation removal from the sub-catchments, which causes a high risk of flooding in the downstream areas. Similarly, Eshete (Citation2009) showed that nearly 8% of the catchment experiences very severe, 15% severe and 35% moderate rates of soil erosion. These studies suggest the need to reverse degradation in the catchment by adopting sustainable land management practices. They stress the importance of considering the needs and interests of relevant institutions, strengthening their capacity, conducting awareness creation and problem-solving research, finding alternative livelihood options for local communities, and involving all relevant stakeholders when planning and implementing sustainable land management practices in the catchment.

Stakeholders and their involvement in natural resource management

We identified several categories of stakeholders including government organizations and NGOs, local administrative bodies, civil society, the private sector and local communities or farmers (). Of the 25 identified stakeholders, eight are identified as key stakeholders, one as primary stakeholder, and 16 as secondary stakeholders (). The majority (85%) of key informants and the review of documents revealed that both government organizations and NGOs identified as key, primary, and secondary stakeholders had similar mission/mandate related to the management of the environment (). Our findings showed that the key forms of the involvement of stakeholders in NRM included provision of technical and financial support and capacity building, sharing of experiences and expertise, mobilization of local communities and provision of labour as well as generating evidence on best practices ().

Table 3. Agenda and forms of stakeholder’s involvement in natural resources management

These forms of involvement of different stakeholders, including government organizations and NGOs, communities, and local administrative bodies, is crucial to sustaining the implementation of NRM interventions in the catchment. For example, sharing of experiences and expertise, capacity building and active involvement of local administrative bodies support (a) better implementation of landscape restoration initiatives, (b) raising of the knowledge of local communities and practitioners on benefits and trade-offs of restoration initiatives, and (c) better protection of landscape restoration initiatives. Other studies (e.g. Warner Citation2006; Jembere Citation2009; Benecke Citation2011) also indicated that gaining political support at various levels, the existence of multi-stakeholder platforms and strengthening interactions between different stakeholders are crucial for the success of natural resources management. Bloomfield et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that building stakeholders’ capacities (tailored training, awareness workshops and experience-sharing activities) is crucial to support stakeholders to address the complex nature of landscape restoration.

Classification of stakeholders

Core functions

We observed considerable differences between the stakeholders in their core functions in terms of legitimacy, resources, and connections (). Of the identified stakeholders, only one stakeholder (S13) had all the three important core functions that distinguished it as outstanding, two stakeholders (S14 and S16) had at least two important core functions that distinguished them as very important and 22 stakeholders had at least one important core function that distinguished them as important (). Most (88%) of the stakeholders had strong legitimacy, 20% were ranked as strong in relation to control over essential resources (e.g. knowledge, expertise and capabilities) and only 8% of the stakeholders were perceived as strong in terms of connections. Most of the stakeholders were perceived as having a rank of weak to medium in relation to control over resources (80%) and connections (92%). It was also noted that four stakeholders (i.e. Agriculture and Natural Resource offices, Environment and Forest Protection offices, Local Communities, and Local Administrative bodies at different levels) had veto power with close relationships with government organizations and NGOs in terms of information exchange, frequency of contact, compatibility of interests, coordination, and mutual trust.

Figure 4. Graphic representation of the core functions of identified stakeholders. The full names of the stakeholders are presented in

The strong legitimacy of many of the stakeholders and a considerable number of stakeholders with veto power indicate that they have strong agency to change the course of events or influence the decisions of others (Betsill et al. Citation2020). This could facilitate their access to political support and the mobilization of local communities when planning and implementing NRM interventions. In this line, Ribot (Citation2003) suggested that the presence of local governments with strong legitimacy enhances participation of stakeholders and promotes more equitable and efficient forms of local management and development. Such stakeholders can re-shape local institutions that manage natural resources, promising to increase participation in ways that will profoundly affect who manages, uses, and benefits from these resources. However, most of the stakeholders were not strong in terms of control over resources and connections. This indicates that financial and material support as well as capacity building and training are crucial to successful implementation of NRM interventions. Also, stakeholder weakness in inter-relationships could affect coordinated actions and co-production of knowledge related to shared resources (e.g. Sayles et al. Citation2019).

Scope of influence and strategic options

The perceived scope of influence and/or field of action of stakeholders varies considerably. In general, the scope of influence of governmental organizations was ranked as the highest, while those of NGOs, civil society and the private sector ranked from second to fourth, respectively. The strong influence of governmental organizations in managing natural resources could be attributed to the role of government organization in the formulation of policies, strategies and guidelines and mobilizing landless youth and women, and engaging them in landscape restoration activities through their structural presence from national to village level. Also, academic and research institutes were keen to influence the use and management of natural resources through generating evidence on best practices and building the capacity of practitioners. The perceived influence of NGOs was ranked as second and they could have considerable influence through their capacity building activities, technical and financial support. The perceived influence of civil society and the private sector ranked as third and fourth, respectively. The minimal influence of these organization on the use and management of natural resources could be attributed to their limited political powers and networks. Joshi and Kumar (Citation2007) indicated that NGOs can play a major role in management and restoration of ecosystems through public participation processes. They further added that the interaction of NGOs with government organizations help to create awareness among communities on environmental issues. This in turn empowers communities with knowledge, which can support development of new initiatives and collective action in support of landscape restoration.

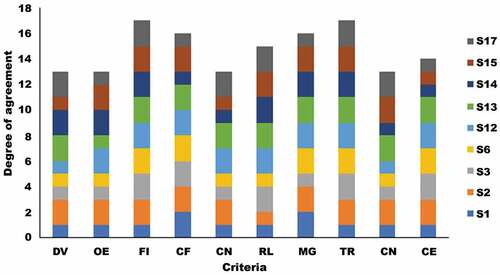

Many key informants and the review of literature indicated that the selected primary and secondary stakeholders that had moderate to considerable influence did not diverge in their strategic options (). For example, of the nine stakeholders, four of them strongly agreed (i.e. +2) that their organization implements development interventions based on democratic principles and the balancing of interests, while the remaining five displayed moderate agreement (i.e. +1) with the statement (). The majority (66–88%) of the selected stakeholders strongly agreed that their organizations were flexible and innovative, kept to agreements and fulfilled the relevant requirements. They also strongly agreed that they had good relationships with other stakeholders, possessed transparent strategies and guidelines, and informed others proactively (). This indicates that there is a high potential of collaboration among stakeholders when planning and implementing NRM interventions and restoration measures. Todeva (Citation2005) elaborated that having stakeholders with similar strategic options supports the achievement of organizational objectives better through collaboration than through competition. This in turn helps the range of stakeholders involved in the management of natural resources to develop a better understanding of the issues and challenges related to achieving conservation goals (Unit Citation2000).

Figure 5. Strategic options of selected key and secondary stakeholders. DV refers to development vision, OE – operational effectiveness, FI – flexibility and innovation, CF- contractual fidelity, CN-communication, RL – relationships, MG – management, TR – trust, CN – conflicts, and CE – capitalising on experience. The degree of agreement of each stakeholder with the statements (or strategic options) varied between – and ++. The sum of the ratings of the 9 selected stakeholders could range from −18 to 18. S1 refers to Agriculture and natural resource offices at different levels, S2 – Environment and Forest Protection offices at different levels, S3 – South Agricultural Research Institute, S6 – Rift Valley Basin development office, S12 – Hawassa city forest, environment and climate change regulation office, S13 – German International Cooperation (GIZ), S14 – SOS Sahel, S15 – People in Need, and S17 – Population, Health and Environment (PHE) – Ethiopia consortium

Power and power resources

Our analysis of the perceived legitimate power based on seven key types of authority supported the assertion that the agricultural and natural resource offices and local administrative bodies possess higher legitimate power compared to other stakeholders (). This could be attributed to that their power is derived from information, communication and negotiation, practical relevance, and social relations (). The German International Cooperation Agency (GIZ) showed higher legitimate power compared to NGOs and some governmental organizations. This could be explained by the nature of the organization (i.e. focussed on supporting the implementation of government plans through providing technical and financial support), which gives the organization power derived from policy and institutional linkages, information and communication and negotiation. GIZ also has power derived from practical relevance. However, most of the NGOs, national academic and research institutes, identified as potential stakeholders had moderate legitimate power (i.e. a value of between 10 and 15, out of a total of 21; ). This could be attributed to weak control of the flow of information and influence over information content, and their low communication and negotiating power. The private sector and civil society had weak legitimate power, as these organizations lacked most power resources ().

Figure 6. The perceived stakeholders’ legitimate power based on seven types of authority

Most of the power resources acquired by some of the key and secondary stakeholders such as agriculture and natural resource offices at different levels (i.e. from national to village levels), environment and forest protection offices, the Hawassa City Forest, Environment and Climate Change Regulation Office, the regional research systems, local administrative bodies and GIZ, could be utilized without major additional inputs, but it requires empowerment of a coordinating agent to which other stakeholders delegate authority to harness and communicate information (Kiser Citation1999). Understanding the power and power resources of the stakeholders, including access to natural resources, knowledge and social networks, may lead to insights on how the stakeholders can be strategic in their actions to democratize and equalize asymmetrical power relations (Raik et al. Citation2008). Barnaud and Van Paassen (Citation2013) argued that giving attention to power asymmetries is crucial to regulate or balance the influence of powerful stakeholders on the outcomes of the participatory process for marginalized stakeholders.

Van Assche et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated that adaptation to changing internal and external environments becomes more efficient, and better matched to the actual changes, when stakeholders are equipped with the necessary power and power resources that support the planning and implementation of NRM interventions. Moreover, knowledge is more likely to influence practice when it emerges from a dialogue and co-production between different stakeholders (e.g. Clark and Harley Citation2020). A study in Ethiopia (Mohammed and Inoue Citation2013) argue that empowering marginalized stakeholders in the decision-making processes related to the management and protection of natural resources helps realize benefits from landscape restoration initiatives such as equitably distributed benefits from the forest and participation by local people in decisions that affect them. Similarly, Berbés-Blázquez et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that understanding power relations amongst stakeholders guide environmental decision-making that can deliver ecological sustainability and socially fair outcomes.

Stakeholder interests

The analysis suggested that the interests of governmental organizations, NGOs and civil society were similar, and that these stakeholders were keen to support the implementation of NRM interventions in the Hawassa catchment as a way of rehabilitating degraded landscapes. Such positive assertion of stakeholder interests and similarities would have a positive effect on the use and management of natural resources and the restoration of degraded landscapes. These stakeholders stressed that building the capacities of practitioners working at grassroots’ level (i.e. district and Kebele levels) is crucial to sustaining NRM efforts and their benefits.

Some of the stakeholders, particularly NGOs indicated that landscape management efforts need to be linked with job creation and diversification of livelihoods to increase the short-term economic benefits of NRM measures and to support local communities to adopt the measures. Our findings agreed with the suggestions from Mekuria et al. (Citation2020) that in poor communities, the incentive to extract short-term economic returns from land and natural resources often outweigh perceived benefits from investing in long-term environmental restoration, and related economic and ecosystem returns. Thus, investment in land and natural resource restoration requires a balance between short-term economic returns and longer-term sustainability and environmental goals. Individuals, households and communities are more likely to accept or invest in activities that enable land rehabilitation over a long period of time, if there are immediate economic incentives.

Influence and interest

The analysis suggested that the participation of the private sector is passive, and it offers few suggestions when it comes to the management of natural resources in the catchment (). Most of the secondary stakeholders displayed moderate to strong interest in managing natural resources and improving ecosystem services. However, these stakeholders had little to minimum influence on progress towards the implementation of NRM interventions (). About 50% of the identified stakeholders fell under compartment ‘B’ and displayed strong interest in the management of natural resources. However, these stakeholders were different in their degree of influence (). Two of these stakeholders (i.e. Agriculture and Natural Resource offices and Hawassa city Forest, Environment and Climate Change regulation office) were key stakeholders with power of veto, and no interventions could be implemented in the study area without the explicit consent of these stakeholder. Five of the stakeholders () were influential, indicating that they were able to support and speed up or block the process of planning and implementing NRM interventions at several points. The remaining five stakeholders that showed strong interest were influential in some areas (), indicating that the stakeholders had influence regarding certain issues, but NRM interventions could still be implemented against their will.

Figure 7. Analysis of stakeholders’ interest and influence. Scale for interest: +2 strong approval, active participation; +1 moderate approval; participation variable; 0 indifferent, waits and observes further developments; −1 moderate rejection; passive participation; −2 strong rejection. Scale for influence: +2 very influential; +1 influential; 0 influential in some areas; −1 little influence: −2 minimal or no influence on progress towards the implementation of the planned project activities

Although there are differences among identified stakeholders in influence and interest, it is crucial to involve governmental organizations, NGOs, local communities and local administrative bodies in all information and decision-making processes. Particularly, involving key and primary stakeholders (see ) at all levels of interventions is important. Also, using and building their experience could support the achievement of the objectives of implementing NRM measures at a landscape or catchment scale, and improve ecosystem services and livelihoods of local communities. It is important to regularly inform stakeholders about the planned activities related to NRM and their achievements to national research and university systems as well as civil society. This assumes that they may, in certain circumstances, play an important role in alliance with other stakeholders. Further, the private sectors should be consulted to ensure that their experiences are integrated into the process and that they are invited to engage.

Ketema et al. (Citation2017) indicated that effective stakeholder engagement in a complex resource system having multiple stakeholders with diverse interests, as is the case in the study area, is fundamental to ensure the successful implementation of NRM interventions. It is also noted that global environmental change has triggered the emergence of new actors and the need to understand to what extent non-state actors, such as environmental organisations, expert networks and the private sector, are complementing or even substituting the functions of the central government and its bureaucracy. Solutions to the challenges of environmental and global change are seen to be co-produced by a host of non-state actors (Dellas et al. Citation2011). Similarly, Curșeu and Schruijer (Citation2017) argued that inclusive decision-making is key to sustainability of NRM interventions.

Building trust and relationships between stakeholders

shows the result of the analysis of trust among stakeholders. Our results suggest that stakeholders 6, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 23, 24, and 25 showed considerable trust in the other stakeholders (scored average values of > 4). The remaining stakeholders displayed a moderate trust in others (average values between 3.5 and 4). Our findings indicate that the private sector was strongly mistrusted compared to other stakeholders (). Although most of the NGOs showed pronounced trust in others, they were only moderately trusted by others (). In summary, our results indicate that project activities related to the use and management of natural resources could be implemented with low transaction cost, as the level of trust among the different stakeholders ranged from moderate to pronounced. In this line, Hamm (Citation2017) indicated that trustworthiness and motivation have important roles to play in driving cooperation intention and behavior. Gray et al. (Citation2012) also argue that trust can enable the public and agencies to engage in cooperative behaviors toward shared goals and address shared problems. As trust among stakeholder develop, they begin to advocate, within their home organizations, for collaborative goals, which in turn reduce the transaction cost incurred to bring stakeholder together (Coleman and Stern Citation2018).

Table 4. The level of trust among the different stakeholders

Further analysis of trust building from the perspective of stakeholders that showed a pronounced trust in the other stakeholders, indicate that the pronounced trust of these organization in others is mainly attributed to (a) important, positive and useful experience of cooperation, (b) intentions and goals that are made explicit and clear, (c) regular meetings and intensive communication, (d) agreements negotiated openly and adhered to, (e) fair distribution of benefits and gains, (f) representatives known to each other, nurturing the relationship, and (g) presentation of relationships to the outside. Coleman and Stern (Citation2018) demonstrated that the development of fair and transparent procedures governing the collaborative group of stakeholders, structured interaction designed to build consensus, and planned informal interactions that reveal shared values among collaborative participants is crucial for building trust and achieving collaborative goals.

The lack of communication between the private sector and other stakeholders could explain the observed low trust of the private sector. Platforms for communication among the private sector, governmental organizations, and NGOs, making goals and intentions clear could alleviate this problem and support the building of strong trust. Also, NGOs should exert more effort in making their goals and intentions clear, and in achieving fair distribution of benefits and gains to achieve trust from other stakeholders. In this line, MacKeracher et al. (Citation2018) argue that trust demonstrates a heterogeneous nature across stakeholder groups. Therefore, targeted strategies are needed to build trust, improve communication, and promote stewardship in large, complex natural resource systems. Multi-stakeholder learning dialogues and platforms could play an important role in incorporating multiple voices, plural meanings, as well as elements of dissent in conversations (Calton and Payne Citation2003). Multi-stakeholder platforms bringing together different types of stakeholders in the Lake Hawassa catchment have already been established and could thus play an important future role in building of trust.

Our results suggest that the relationships between government organizations and NGOs, and the private sector are weak or mostly informal or unclear. In most cases, the relationships between government organizations and NGOs symbolise alliances and cooperation that are organized contractually or institutionally. Our findings show that the alliance or relationships with other stakeholders in terms of institutionally regulated dependency, ongoing information exchange, coordinated action and co-production with common resources ranged from weak to medium. This could be attributed to the lack of coordination and information exchange while planning and implementing NRM interventions. This could affect the successful implementation of NRM measures in the catchment and lead to inefficient use of limited resources. According to Ariti et al. (Citation2018), the poor cooperation and networking among NGOs and between NGOs and governmental organizations could arise from relying on their own objectives and avoiding collusions with the state.

Exclusion and empowerment

illustrates perceived access to and control of resources and competencies. Government bureaus such as Health and Culture and Tourism Bureaus as well as civil society have good basic competencies but nonetheless have little access to resources that can be used for landscape restoration and are largely excluded from relevant decision-making processes. Due to their basic competencies, it is likely that sooner or later they will raise their voice and register their demands. These stakeholders need to be actively supported to be able to participate in negotiation processes about natural resources use and management and to represent their own interests. The analysis indicated that the majority (68%) of the stakeholders comprised governmental organizations, NGOs, local communities and administrative bodies (), had both access to and control of resources, as well as a high level of basic competencies. It is not necessary to use empowerment measures for this group. We also observed that the private sectors had access to and some degree of control over resources, but only had a few basic competencies. This indicates that empowerment measures should be concentrated first and foremost on the actors’ capacity to organise themselves towards the planning and implementation of NRM measures through for example multi-stakeholder platforms.

Table 5. Perceived access to and control of resources and competencies

Implications for future planning and implementation of restoration initiatives in the catchment

Landscape degradation in the lake Hawassa catchment is mainly attributed to complex and interlinked direct and indirect drivers. Therefore, halting land degradation in the catchment requires focusing on the underlying causes rather than on the effects, symptoms, and impacts. For instance, reclaiming a gulley is not the ultimate solution for addressing landscape degradation, but efforts must be directed towards improving unsustainable land-use practices that reduce land cover and infiltration thereby contributing to gully formation. We found that government authorities and NGOs use their authority to decide how local communities should participate in landscape management initiatives. Such a top-down approach affects the sustainability of restoration initiatives because local stakeholders lack incentives to participate. They also lead to inadequate understanding of the complex relationships between people and the natural resources they depend on, and inability to tailor restoration responses to specific needs and conditions.

The results obtained through the analysis of the three core functions of stakeholder participation demonstrated that empowerment measures should be concentrated first and foremost on the actors’ capacity to organize themselves towards the planning and implementation of landscape restoration measures through, for example, creating and supporting effective and functioning multi-stakeholder platforms for dialogue and co-production of knowledge. In this regard, existing multi-stakeholder forums in Hawassa can be used to bring stakeholders together and discuss issues related to land degradation and landscape restoration.

Having influential stakeholders with similar strategic options and the existence of good relationships suggest that collaboration among stakeholders when implementing landscape restoration measures can be achieved with low transaction costs (i.e. in terms of time and effort invested). Because most of the primary and secondary stakeholders are influential and equipped with the necessary power resources (e.g. information and expertise), they can easily adapt to internal and external changes and can effectively implement landscape restoration measures under a changing environment.

The study revealed that diverse stakeholders involved in landscape restoration activities in the lake Hawassa catchment have different levels of influence. There are some stakeholders with power of veto, others are just influential whilst some less so. Despite differences in their level of influence, it is crucial to aim for inclusivity ensuring that governmental organizations, NGOs, local communities, local administrative bodies and the private sector are all given opportunities to play an active role in decision-making processes related to landscape restoration and management. Effective stakeholder engagement in complex resource systems, as is the case in the Lake Hawassa catchment, is thus needed to ensure successful implementation of landscape restoration measures. Inclusive decision-making is key to sustainability of landscape restoration initiatives.

The study demonstrated the applicability of the method by Reed et al. (Citation2009) for specific areas, such as the Hawassa catchment. We suggest giving more emphasis to local drivers of change when analysing the context and setting issues at the catchment and landscape scale. When analysing the relationships between different stakeholders, a deeper understanding of agency and how agents acquire authority is required. It is also vital to understand ongoing multi-stakeholder dialogue processes, the role of networks and co-production of knowledge. The final step in the method of identifying action should be embedded in an understanding of the broader governance system affecting catchment and landscape management, linked to a range of governance attributes, including but not limited to participation. Jiménez et al. (Citation2020) also identified attributes such as multilevel, inclusiveness, transparency, impartiality, and rule of law as crucial.

Recommendations for future research for development activities

A stakeholder analysis targeting Lake Hawassa catchment in the central rift valley of Ethiopia was conducted to understand how to enhance the success of ongoing landscape restoration initiatives. Through systematic analysis, a deeper understanding of stakeholder interests, influence, and power relations was gained. We suggest that future research for development initiatives related to landscape restoration should focus on:

Finding ways of integrating landscape restoration measures/initiatives with livelihood diversification, following a systems approach when evaluating landscape restoration measures and investigating options for addressing the underlying causes of land degradation.

Exploring ways of ensuring active involvement of all stakeholders at all levels of landscape restoration, building on convergence in their strategic interests as well as experience to sustainably restore degraded landscapes.

Exploring ways of empowering stakeholders with limited power and influence, strengthening their capacity to organise themselves towards the planning and implementation of NRM.

Investigating the challenges and opportunities of multi-stakeholder platforms and assess ways of incorporating multiple interests and agency in dialogues on landscape restoration to build trust in planning and implementation of restoration measures.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (476.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful to government and non-governmental organizations, civil society and the private sector for their cooperation and facilitation of the research work. We are also very grateful to the local communities in the study area and the Community Watershed Team (CWT) for their support during the field work. We thank Prof. Jo Smith for editing the manuscript and Dr. Abeyou Wale for supporting in producing high resolution figures. The work was undertaken as part of the Ethiopian Land and Water Governance Program implemented by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. CAB Abstracts, also called CAB or CABI, is the database created by what was the Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau (now called the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International). International in scope, it covers agriculture broadly, from agronomy to veterinary medicine, with citations to journal articles, monographs, conferences, books and annual reports, from 100+ countries.

2. Qualitative coding often involves coders assigning different labels to the same instance, leading to ambiguity. Such an instance of ambiguity is referred to as disagreement in coding (Zade et al. Citation2018).

References

- Ademe F, Kibret K, Beyene S, Getnet M, Mitike G. 2020. Rainfall analysis for the rainfed farming in the great rift valley basins of Ethiopia. J Water Climate Change. 11(3):812–828. doi:10.2166/wcc.2019.242.

- Ariti AT, Van Vliet J, Verburg PH. 2018. What restrains Ethiopian NGOs to participate in the development of policies for natural resource management? Environ Sci Policy. 89:292–299. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.08.008.

- Barnaud C, Van Paassen A. 2013. Equity, power games, and legitimacy: dilemmas of participatory natural resource management. Ecol Soc. 18(2):21. doi:10.5751/ES-05459-180221.

- Barrow E, Jeanette C, Isla G, Kamugisha-Ruhombe J, Yemeserach T. 2002. Analysis of stakeholder power and responsibilities in community involvement in forestry management in Eastern and Southern Africa. Nairobi (Kenya): IUCN Eastern Africa Regional Office P.O.; 154 pp.

- Belay M, Woldeamlak B. 2013. Stakeholder linkages for sustainable land management in Dangila woreda, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Environ Stud Manage. 6(3):253–262.

- Belete MD, Diekkrüger B, Roehring J. 2017. Linkage between water level dynamics and climate variability: the case of Lake Hawassa hydrology and ENSO phenomena. Climate. 5(1):21. doi:10.3390/cli5010021.

- Benecke E. 2011. Networking for climate change: agency in the context of renewable energy governance in India. Int Environ Agreements. 11:63–83. doi:10.1007/s10784-011-9148-8.

- Berbés-Blázquez M, González JA, Pascual U. 2016. Towards an ecosystem services approach that addresses social power relations. Curren Opin Environ Sustain. 19:134–143. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2016.02.003.

- Bernard R. 2006. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 4th Ed ed. USA: AltaMira Press; p. 463–522.

- Betsill MM, Benney TM, Gerlak AK. 2020. Agency in Earth system governance. Cambridge University Press, UK. doi:10.1017/9781108688277.

- Biggs SD. 1989. Resource‐poor farmer participation in research: a synthesis of experiences from nine national agricultural research systems. The Hague (The Netherlands): International Service for National Agricultural Research.

- Blomquist W. 2009. Multi-level governance and natural resource management: the challenges of complexity, diversity, and uncertainty. In: Beckmann V, Padmanabhan M, editors. Institutions and sustainability. Dordrecht: Springer; p. 109–126.

- Bloomfield G, Meli P, Brancalion PHS, Terris. Guariguata MR, Gare E. 2019. Strategic insights for capacity development on forest landscape restoration: implications for addressing global commitments. Trop Conservat Sci. 12:1–11. doi:10.1177/1940082919887589.

- Brugha R, Varvasovszky Z. 2000. Stakeholder analysis: a review. Health Policy Plan. 15(3):239–346. doi:10.1093/heapol/15.3.239.

- Calton JM, Payne SL. 2003. Coping with paradox: multistakeholder learning dialogue as a pluralist sensemaking process for addressing messy problems. Bus Soc. 42(1):7–42. doi:10.1177/0007650302250505.

- Chan A, Singh C. 2000. Case study of the integrated coastal fisheries management project: a pilot project for the Gulf of Paria, Trinidad. CANARI Technical Report No. 280:11.

- Clark WC, Harley AG. 2020. Sustainability science: towards a synthesis. Ann Rev Environ Res. 54:14.1–14.56.

- Coleman K, Stern MJ. 2018. Boundary spanners as trust ambassadors in collaborative natural resource management. J Environ Plann Manage. 61(2):291–308. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1303462.

- Curșeu PL, Schruijer SG. 2017. Stakeholder diversity and the comprehensiveness of sustainability decisions: the role of collaboration and conflict. Curren Opin Environ Sustain. 28:114–120. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.09.007.

- De Bussy NM, Kelly L. 2010. Stakeholders, politics and power. Towards an understanding of stakeholder identification and salience in government. J Commun Manage. 14(4):289–305. doi:10.1108/13632541011090419.

- Dellas E, Pattberg P, Betsill M. 2011. Agency in earth system governance: refining a research agenda. Int Environ Agree. 11(1):85–98. doi:10.1007/s10784-011-9147-9.

- Díaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Bartuska A, Adhikari JR, Arico S, Báldi A. 2015. The IPBES conceptual framework—connecting nature and people. Curren Opin Environ Sustain. 14:1–16. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002.

- Elias E, Seifu W, Tesfaye B, Girmay W, Tejada Moral M. 2019. Impact of land use/cover changes on lake ecosystem of Ethiopia central rift valley. Cog Food Agri. 5(1):1595876. doi:10.1080/23311932.2019.1595876.

- Elo S, Kyngas H. 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 62(1):107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- Eshete T. 2009. Spatial analysis of erosion and land degradation leading to environmental stress: the case of Lake Hawassa Catchment [Doctoral dissertation]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Addis Ababa University.

- Freeman RE. 1984. Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. New York: Basic Books.

- Giweta M, Worku Y. 2018. “Reversing the degradation of Ethiopian wetlands”: is it unachievable phrase or a call to effective action? Int J Environ Sci Natural Res. 14(5):136–146.

- Global Water Partnership. 2017. Stakeholder analysis; [accessed 2020 May 27]. https://www.gwp.org/en/learn/iwrm-toolbox/Management-Instruments/Modelling_and_decision_making/Stakeholder_analysis/.

- Gray S, Shwom R, Jordan R. 2012. Understanding factors that influence stakeholder trust of natural resource science and institutions. Environ Manage. 49(3):663–674. doi:10.1007/s00267-011-9800-7.

- Grimble R. 1998. Stakeholder methodologies in natural resource management. Socioeconomic Methodologies. Best Practice Guidelines. Chatham (UK): Natural Resources Institute.

- Grimble R, Chan MK. May 1995. Stakeholder analysis for natural resource management in developing countries: some practical guidelines for making management more participatory and effective. In Natural Resources Forum. Vol. 19, No. 2. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing Ltd; p. 113–124.

- Groenendijk EMC. 2003. Planning and management tools. Enschede (The Netherlands): ITC, Special lecture notes series. ITC.

- Hamm JA. 2017. Trust, trustworthiness, and motivation in the natural resource management context. Soc Nat Resour. 30(8):919–933. doi:10.1080/08941920.2016.1273419.

- Hart C. 2001. Doing a literature search:a comprehensive guide for the social sciences. London: Sage.

- Hsieh HF, Sannon SE. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 15:1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Jembere K. 2009. Implementing IWRM in a catchment: lessons from Ethiopia. Waterlines. 28(1):63–78. doi:10.3362/1756-3488.2009.006.

- Jiménez J, Saikia P, Giné R, Avello P, Leten J, Liss Lymer B, Schneider K, Ward R. 2020. Unpacking water governance: a framework for practitioners. Water. 12:827. doi:10.3390/w12030827.

- Johnson N, Lilja N, Ashby JA, Garcia JA. 2004 Aug. The practice of participatory research and gender analysis in natural resource management. In: Natural Resources Forum. Vol. 28, No. 3. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing Ltd. p. 189–200.

- Joshi H, Kumar A. 2007. Role of non-governmental organizations in restoration and management of freshwater ecosystems. Proceedings of Taal, 1880-1884; The 12th World Lake Conference, India.

- Ketema DM, Chisholm N, Enright P. 2017. Examining the characteristics of stakeholders in Lake Tana sub-basin resource use, management and governance. In: Stave K, Goshu G, Aynalem S, editors. In social and ecological system dynamics. Cham: Springer; p. 313–346.

- Kiser E. 1999. Comparing varieties of agency theory in economics, political science and sociology: an illustration from state policy implementation. Soc Theory. 17:146–170. doi:10.1111/0735-2751.00073.

- Lamelas P. 2000. Integrating stakeholders in participatory natural resource management: ecotourism project of El Limon Waterfall, Dominican Republic. CANARI Technical Report No. 283:7.

- Lukes S. 1974. Power: a radical view. Basingstoke (UK): Macmillan.

- MacKeracher T, Diedrich A, Gurney GG, Marshall N. 2018. Who trusts whom in the Great Barrier Reef? Exploring trust and communication in natural resource management. Environ Sci Policy. 88:24–31. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.06.010.

- Matti S. 2009. Exploring public policy legitimacy: a study of belief-system correspondence in Swedish environmental policy [Doctoral dissertation]. Lulea (Sweden): Lulea University Press.

- Mekuria W, Gebregziabher G, Lefore N. 2020. Exclosures for landscape restoration in Ethiopia: business model scenarios and suitability. Colombo (Sri Lanka): International Water Management Institute (IWMI); 62p. IWMI Research Report 175. https://doi.org/10.5337/2020.201.

- Mohammed AJ, Inoue M. 2013. Exploring decentralized forest management in Ethiopia using actor-power-accountability framework: case study in West Shoa zone. Environ, Develop Sustain. 15(3):807–825. doi:10.1007/s10668-012-9407-z.

- MoWR [Ministry of Water Resources]. 2009. Rift Valley lakes basin integrated resources development master plan study project. Phase 3: draft report J. Lake Hawassa Sub-Basin integrated watershed management feasibility study. Hal Crow Group Limit Gen Integrat Rural Develop Consultants. 1:3 & 4.

- Mulyaningrum M, Kartodihardjo H, Jaya INS, Nugroho B. 2013. Stakeholders analysis of policy-making process: the case of timber legality policy on private forest. J Manage Hutan Tropika. 19(2):156–162.

- Nelson GC, Bennett E, Berhe AA, Cassman K, DeFries R, Dietz T, Marco D, Dobson A, Janetos A, Levy M. 2006. Anthropogenic drivers of ecosystem change: an overview. Ecol Soc. 11:2. doi:10.5751/ES-01826-110229.

- Nuga BO, Akinbola GE, Nuga OO. 2009. Stakeholder analysis: a conceptual framework for sustainable watershed development in the Ikwuano watershed in south east Nigeria. Global Approach Exten Pract(GAEP). 5(2):2009.

- Otuokon S. 2000. Case study of the negril environmental protection Plan, Jamaica. CANARI Technical Report No. 284:8.

- Pain R. 2004. Social geography: participatory research. Prog Hum Geogr. 28:652–663. doi:10.1191/0309132504ph511pr.

- Prell C, Hubacek K, Reed M. 2009. Stakeholder analysis and social network analysis in natural resource management. Soc Nat Resour. 22(6):501–518. doi:10.1080/08941920802199202.

- Raik DB, Wilson AL, Decker DJ. 2008. Power in natural resources management: an application of theory. Soc Nat Resour. 21(8):729–739. doi:10.1080/08941920801905195.

- Reed MS, Graves A, Dandy N, Posthumus H, Hubacek K, Morris J, Stringer LC, Quinn CH, Stringer LC. 2009. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J Environ Manage. 90(5):1933–1949. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.01.001.

- Ribot JC. 2003. Democratic decentralization of natural resources. In: Van De Walle N, Ball N, Ramachandran V, editors. Beyond structural adjustment. New York: The Institutional Context of African Development. Palgrave Macmillan; p. 159–182.

- Richards C, Carter C, Sherlock K. 2004. Practical approaches to participation SERG policy brief no. 1. Aberdeen (Scotland): Macauley Land Use Research Institute.

- Sayles JS, Garcia MM, Hamilton M, Alexander SM, Baggio JA, Fischer AP, Ingold K, Meredith GR, Pittman J. 2019. Social-ecological network analysis for sustainability science: a systematic review and innovative research agenda for the future. Environ Res Lett. 14(9):093003. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab2619.

- Sterling EJ, Betley E, Sigouin A, Gomez A, Toomey A, Cullman G, Malone C, Pekor A, Arengo F, Blair M, et al. 2017. Assessing the evidence for stakeholder engagement in biodiversity conservation. Biol Conserv. 209:159–171. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.02.008.

- Tadesse S, Woldetsadik M, Senbeta F. 2018. Attitudes of forest users towards participatory forest management: the case of Gebradima Forest, Southwestern Ethiopia. Small-scale For. 17(3):293–308. doi:10.1007/s11842-017-9388-8.

- Talley JL, Schneider J, Lindquist E. 2016. A simplified approach to stakeholder engagement in natural resource management: the five-feature framework. Ecol Soc. 21(4):38. doi:10.5751/ES-08830-210438.

- Tiki L, Tadesse M, Yimer F. 2015. Effects of integrating different soil and water conservation measures into hillside area closure on selected soil properties in Hawassa Zuria District, Ethiopia. J Soil Sci Environ Manage. 6(10):268–274.

- Todeva E. 2005. Strategic alliances and models of collaboration. Manage Dec 43(1):123–148.

- Unit WECS. 2000. Stakeholder Collaboration: Building Bridges for Conservation.

- Van Assche K, Beunen R, Duineveld M, Gruezmacher M. 2017. Power/knowledge and natural resource management: foucaultian foundations in the analysis of adaptive governance. J Environ Policy Plann. 19(3):308–322. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2017.1338560.

- Vogler D, Macey S, Sigouin A. 2017. Stakeholder analysis in environmental and conservation planning. Lessons Conservat. 7:5–16.

- Warner JF. 2006. More sustainable participation? Multi-stakeholder platforms for integrated catchment management. Int J Water Resour Dev. 22(1):15–35. doi:10.1080/07900620500404992.

- Zade H, Drouhard M, Chinh B, Gan L, Aragon C. 2018 Apr. Conceptualizing disagreement in qualitative coding. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. USA; p. 1–11.

- Zeleke G, Kassie M, Pender J, Yesuf M. 2006. Stakeholder analysis for sustainable land management (SLM) in Ethiopia: assessment of opportunities, strategic constraints, information needs, and knowledge gaps. 2nd draft. Environmental Economics Policy Forum for Ethiopia (EEPFE). Addis Ababa. p. 96.

- Zenebe MG. 2014. Watershed degradation and the growing risk of erosion in Hawassa-Zuria District, Southern Ethiopia. J Flood Risk Manage. 7(2):118–127. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12033.

- Zimmermann A, Claudia M. 2007. Multi-stakeholder management. Tools for stakeholder analysis: 10 building blocks for designing participatory systems of cooperation. Eschborn (Germany): GTZ.