ABSTRACT

Although researchers have postulated different modes of governance, the degree of empirical support for different governance modes in ecosystem service literature remains unclear. Understanding the contexts under which governance modes have been researched and applied in practice could help decision-makers choose appropriate strategies to the provision of ecosystem services. We conducted a literature review to explore the development of empirical research on ecosystem services governance and to illustrate research frontiers and gaps in this research. We reviewed 157 empirical papers on the governance of ecosystem services published between 2006 and 2019. Our results show that the number of papers about the governance of ecosystem services has increased and that researchers have mainly used qualitative and mixed methods. No governance mode has dominated the research field. Rather, different governance modes have been studied in combination, possibly reflecting the fact that multiple and overlapping governance arrangements often affect the provision of ecosystem services. The geographical distribution of ecosystem services governance research is diverse, but misses perspectives from certain regions, such as Southeast Asia. This means that while decision-makers in well-studied areas like Western Europe can use a pool on studied arrangements, in other areas decision-makers may find limited literature to inform their decisions to maintain and strengthen ecosystem services.

EDITED BY:

Introduction

A major assumption of early ecosystem services (ES) research was that once researchers could show how people obtain benefits from nature, humanity would act upon this knowledge (Costanza et al. Citation1997; de Groot et al. Citation2002; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Citation2005). Even today, this assumption is still one of the major motivations underpinning ES research (Droste et al. Citation2018). Despite a rapid increase in scientific publications about ES (Seppelt et al. Citation2011; Costanza et al. Citation2017), in general, the quality and status of ES and of the environment continues to decline (IPBES Citation2018; Legagneux et al. Citation2018). The ES concept has not been adopted as quickly and broadly by decision-makers as some researchers might have hoped, prompting reflection on how to turn the promise of ES research into practice, in order to improve the quality and status of the environment (Guerry et al. Citation2015). To operationalise the ES concept, the ES research community is increasingly striving to understand the role of governance in the supply of and access to ES (Jax et al. Citation2018; Potschin-Young et al. Citation2018).

Over the past decade, governance has gained more attention in ES research (e.g. Rival and Muradian Citation2013; Gómez-Baggethun and Muradian Citation2015; Loft et al. Citation2015; Sattler et al. Citation2018). This is illustrated by the uptake and integration of ‘governance’ in ES conceptual frameworks highlighting the relevance of governance for ES provision and ultimately for human well-being (Sattler et al. Citation2018). Political processes such as the activities of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), as well as national assessments and studies, have further highlighted the need to understand the role of governance for ES. The topic has found more attention over the last years, but compared to modelling or mapping ES, research on ES governance is less represented in ES research (Droste et al. Citation2018; Lautenbach et al. Citation2019).

For this reason, the research objective of this review paper is to explore the development of empirical research on ES governance between 2006 and 2019 and to illustrate research frontiers and gaps in the research of ES governance. We focus on empirical research since learning from real examples in real places can inform policy- and decision-making about the possibilities and challenges of different governance approaches.

Governance of ecosystem services

Governance is a process of interaction in which public and private actors solve societal challenges (Kooiman Citation2003; Swyngedouw Citation2005). The interactions between actors can be cross-sectoral, participatory, voluntary or obligatory and can involve mainly non-governmental or private actors without a governmental or state administration guiding the interaction. All actors are influenced by and behave according to institutions, which ‘are the conventions, norms and formally sanctioned rules of a society’ (Vatn Citation2005, p. 83) and that might be specific to their actor group.

In the broader field of environmental governance, governance of social-ecological systems has been studied with a focus on human-nature interactions (Binder et al. Citation2013; Young Citation2013; Folke et al. Citation2016). The governance of social-ecological systems takes place in a complex network of formal and informal institutions in which actors have often different interests and lobby for them at different scales (e.g. spatial, social, political) (Meadowcroft Citation2002; Cash et al. Citation2006; Ekroos et al. Citation2017). Environmental governance is often multi-level and polycentric because ‘many actors in different institutional settings contribute to policy development and implementation’ (Pahl-Wostl Citation2009). For example, in Europe, farmers affect landscapes locally and make their decisions based on agriculture subsidies of the European Union and on informal institutions like local traditions. Renewable energy producers, on the other hand, affect landscapes at a bigger extent incentivized by national legislation (Winkler and Hauck Citation2019).

ES governance is part of the wider field of environmental governance. Social-ecological systems have been central to environmental governance research, yet the ES research has shifted the understanding of the social-ecological relations by adding a narrative about how nature contributes to human well-being (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Citation2005; Díaz et al. Citation2018). This means that ES governance research is less concerned with the governance of a stock (i.e. the environment), but rather of a capacity to (co-)produce a flow (i.e. ecosystem service) that provides a benefit to humans. As such, ES governance can be seen as governing a dynamic process with a clear anthropocentric focus which are the two aspects specific that differentiate it from other environmental governance concepts. This does not mean that there are no overlaps and lessons-learnt that can be used. Nevertheless, governing a dynamic process might mean that also the governance has to be more dynamic if the item to be governed is in constant flux. The strong anthropocentric focus makes ES governance prone to fall for dominant, loud voices in Western societies promoting instrumental values and monetarization of nature (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021). However, a lot of research on ES and their governance has shown the importance of multiple values including relational values (Chan et al. Citation2016, Citation2018; Jacobs et al. Citation2016).

One popular conceptual framework in ES research is the ‘ecosystem services cascade’, which presents a circular flow depiction between the ecological system (ecosystem structure and functions) and the social system (benefits and values) connected by ES (Haines-Young and Potschin Citation2010; Potschin-Young et al. Citation2018). A feedback loop – called ‘pressures’ in the original version of the cascade – links back from the social to the ecological system. Based on the increased acknowledgement of the importance of governance, more recent adaptations of the ES cascade have replaced ‘pressures’ with ‘governance’ (Primmer et al. Citation2015; Partelow and Winkler Citation2016). The conceptual framework of IPBES has further developed the idea of a circular flow of social and ecological elements, but put ‘institutions and governance’ at the center of its framework, thereby highlighting the critical role of governance for ES and biodiversity (Díaz et al. Citation2015).

Research on governance has developed within ES research since the publication of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Citation2005), which recognizes the complexity of interactions between social and ecological systems and the need for decision-makers to act. ES governance describes the interactions of human systems with ES (Loft et al. Citation2015; Sattler et al. Citation2018; Potschin-Young et al. Citation2018). With the emergence of research on ES governance, many terms used in the general governance literature (e.g. multi-level, cross-sectoral, decentralized governance) have been introduced to the ES literature (Rival and Muradian Citation2013; Loft et al. Citation2015; Sattler et al. Citation2018).

Primmer et al. (Citation2015) integrate the conceptualization of governance with the ES cascade for empirical applications. In their adapted ES cascade, governance not only links the social and the ecological systems, but also connects the different stages of the cascade through four modes of governance: 1) scientific-technical; 2) (adaptive) collaborative; 3) governing strategic behavior; and 4) hierarchical (see ). These four modes of governance influence the ecological and the social systems and should be considered for the design of ES governance. In addition, these governance modes are interconnected, with hierarchical governance influencing the other three modes of governance.

Table 1. Four governance modes that guide the analysis. Examples in the end of each description are based on the literature review of this paper

Methods

Data collection

We conducted a literature review to explore the development of research on ES governance and to identify research frontiers and gaps. We conducted our literature search in Scopus using a search string with the words ‘ecosystem service*’ and ‘governance’ in titles, abstracts and keywords of publications. We limited our search to the years 2006 to 2019. We chose 2006 as the starting year because the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment was published the year before (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Citation2005), starting the growth of ES governance research (Costanza et al. Citation2017). As a second literature search, we used only the term ‘ecosystem service*’ to calculate the proportion of ES literature that references governance compared to the rest of the ES literature.

Our first search string returned 1,079 publications (Appendix B). We then limited our selection to publications that had on average at least one citation per year since their publication as a criterion for relevance in the scientific discourse, which reduced the number of publications to 934. Next, we used the abstracts of the publications to identify publications that focused on ecosystem services rather than those that simply mentioned the term to motivate discussion about other social-ecological research concepts, biodiversity, or pure methodological approaches. We classified 262 publications as ES-focused. Next, we categorized these ES-focused publications into different publication types: empirical, theoretical/conceptual, mixed, and review. Mixed research had at least a partial empirical focus, along with either theoretical/conceptual developments or review content. With our focus on empirical literature, the selection criteria yielded 157 publications (Appendix B) that focused on ES and governance and that had an empirical or mixed research approach.

Data analysis

We calculated the growth of the governance publications focused on ES identified through our main search and compared it with the growth rate of ES publications in general found through our second search. Next, we analyzed the proportion of ES focused publications among the four publication types (empirical, theoretical/ conceptual, mixed, review) in order to see if we could identify a development in the field.

For each of the 157 empirical or mixed governance publications with a focus on ES, we classified the mode(s) of ES governance that the publication applied, based on the four governance modes introduced by Primmer et al. (Citation2015). As an author team, we used the more detailed definitions that we present in as criteria to assign the publications to one or more of the four ES governance modes. Publications were split between the authors to assign ES governance modes, but when modes could be interpreted in different ways, we discussed the publications together to make a balanced judgment. We also categorized the methods that the publication used into qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods. In addition, we extracted the geographical location of the studies and their extent according to political units.

We used descriptive statistics to identify the overall growth in the number of publications, the types of publications, and the governance modes. We categorized the spatial extent of each of the empirical cases in the papers along five political units: local (villages, municipalities, and cities), regional (counties, states, national parks, ecoregions), country, supranational (multiple countries), or global. To assess whether certain governance modes were more commonly studied at one scale than another, we ran a chi-square contingency test. For this statistical analysis, we grouped the scales ‘supranational’ and ‘global’ together since each of these scales only has a few studies for each governance type. We interpret the statistical significance of these results with caution since three out of the twelve categories had expected values less than five.

Last, we quantitatively analyzed the content of the abstracts of the 157 reviewed publications in order to identify patterns in language. However, since results were not significant (i.e. no changes in language usage over time) we do not discuss these methods and results further in the body of the paper, but we have included the results in the appendix (Appendix A).

Results

In this section, we first give an overview of the ES governance literature before we focus on the empirical studies on the governance of ES.

Ecosystem services governance literature

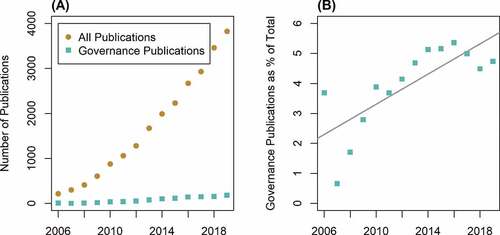

Publications about ES governance have increased from 8 publications in 2006 to 181 publications in 2019 (, Appendix B). Between 2006 and 2019, the annual number of publications about ES in general has increased from 217 (2006) to 3,823 (2019). The percent of ES publications including the term ‘governance’ has increased from 3.7% (2006) to around 5% between 2014 and 2019. However, most literature found using the two search terms ‘ecosystem service’ and ‘governance’ does not actually combine these two research realms but belongs to the wider field of social-ecological research including climate and biodiversity research connected to human systems. For example, many researchers have applied Ostrom’s diagnostic social-ecological framework to analyse governance of social-ecological aspects, and only make minor reference to ecosystem services to broadly frame their paper. This shows that research combining ES with governance has so far been a minor (but increasing) part in the wider ES research, but also that specific ES concerns for governance have been less studied. Assuming that the ES concept reveals specific questions in the wider social-ecological research field and thus, findings from other social-ecological governance research cannot answer these specific questions, this indicates that there might be a lack of specific attention on questions of ES governance in the wider environmental and social-ecological systems governance research.

Figure 1. (a) The number of publications on ES (brown dots) and of publications including the terms ‘governance’ and ‘ecosystem services’ in their abstract (blue square). (b) The percentage of all ES publications that include governance has increased over time (P = 0.001). The gray line shows a best fit line from a linear regression

The 157 publications focusing on ES and governance have been published in over 80 different journals, with the three most common being Ecosystem Services (n = 53), Ecological Economics (n = 18), and Ecology and Society (n = 16) (Appendix B).

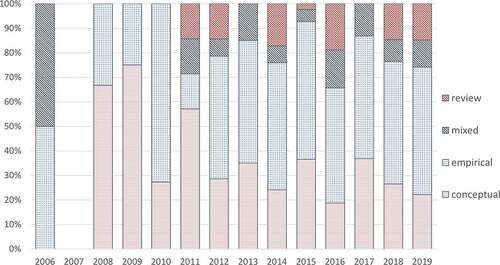

There was no major trend on the type of publication (i.e. empirical, theoretical, mixed, or review) over the years, although we found an emphasis on empirical papers or papers with an empirical part (). Half of the publications were empirical studies (50.0%, n = 131), and 26 publications combined conceptual and empirical work (9.9%). We identified 80 conceptual publications (30.5%) and 25 reviews (9.5%). The percentage of conceptual papers decreased between 2006 and 2019 (). The percentage of empirical studies varied from year to year – excluding the first few years with very limited publications in general, empirical studies normally made up for around half of the annual publications. The percentage of ‘mixed’ papers combining conceptual and empirical work varied between 4.9% and 50.0%. Since 2011, more review articles have been published indicating that governance of ES has been established enough as a research topic that it is considered worthy and rich enough for reviews. The high share of empirical or mixed paper allows the speculation that there are some lessons learnt in the literature on how to govern ecosystem services.

Empirical publications on governance and ecosystem services

Location and extent of empirical studies

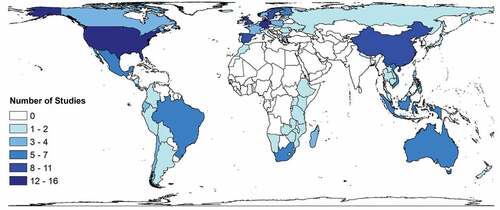

Empirical studies have been conducted throughout the world, with publications from six continents in our reviewed literature (). Nevertheless, most empirical studies have been concentrated in a few countries: China, Brazil, Australia, the United States of America, and Western European countries such as the United Kingdom and Sweden. Africa, South-East Asia, Central Asia and Eastern Europe had fewer studies compared to other world regions. The research gap of ES governance in these regions might stem from a lack of ES terminology in policy and governance documents of these countries or from a dearth of research funding and human capital. Yet, we identified a few studies in Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Kaye-Zwiebel and King (Citation2014), who illustrated the importance of including pastoralists’ perspectives into management, and Strauch et al. (Citation2016), who examined the influence of natural resource management for the provision of ecosystem services. For both of the exemplified publications, the main authors are affiliated with research bodies in the Global North. Concerning empirical studies in South-East Asia and in some parts of Latin America, researchers have focused heavily on governance issues in payments for ecosystem services programs, such as in Vietnam (Suhardiman et al. Citation2013) and Colombia (Rodríguez-de-Francisco et al. Citation2019). Our comparison indicates that the empirical ES governance studies on the African, Asian and Latin American continents were more likely to focus on strategic behavior governance approaches, whereby studies in Western European countries more often analyzed hierarchical or adaptive-collaborative governance approaches. We also found a series of publications that compared multiple countries (especially in the European Union) or had a global perspective. These studies focused mainly on hierarchical governance (e.g. Carmen et al. Citation2018) and on scientific-technical governance (e.g. Pasgaard et al. Citation2017).

Figure 3. World map showing the distribution of empirical ES governance studies. The colour intensity illustrates the number of studies within a given country. There were 17 studies at the supranational or global scale that are not shown on the map

Of the 157 empirical papers, we found that most publications (57.3%, n = 90) presented cases on a regional level, which we defined as the level between the local/municipal and national levels, which were the second and third most studied levels, respectively (). These studies focused on ES governance in a variety of ecosystems like forests, agricultural land, mountains, and coastal areas (including mangroves, coral reefs). Publications focusing on a local/municipal level did not only focus on the natural or semi-natural ecosystems, but also on urban areas mainly located in Western Europe and North America (e.g. Ernstson et al. Citation2010; Young and McPherson Citation2013; Kabisch Citation2015). Only a few of the publications that we reviewed focused on supranational levels (e.g. the European Union) or the global level (e.g. IPBES).

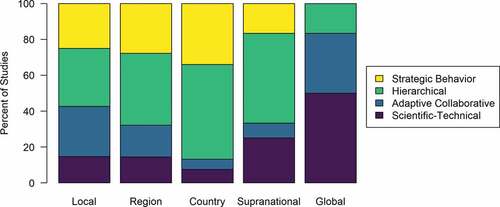

Figure 4. The frequency of each of the four modes of governance in studies by scale, grouped according to authors’ own spatial categories: local (n = 68) – villages, cities and municipalities; region (n = 90) – counties, states, national parks, ecoregions; country (n = 53) – political unit; supranational (n = 12) – multiple countries, e.g. European Union, South America; global (n = 6) – global perspective, no spatial focus

Methods of empirical studies

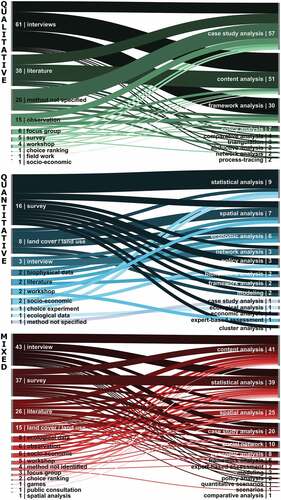

More than half (60.5%, n = 95) of the reviewed empirical papers relied on qualitative methods to collect and analyze data (). Interviews, literature such as policies, rules and regulations, and observations were the main data collection methods. These publications relied mainly on case studies, content analysis, and framework applications as methods for their data analysis. However, use of comparative case studies was rather limited (Ruckelshaus et al. Citation2015; Carmen et al. Citation2018). To our surprise, we found that a sixth of the qualitative publications (16.6%, n = 26) did not identify how the data used in the publication were collected, which makes it difficult to evaluate the quality of the arguments presented. In addition, 35 publications (22.3%) presented their data in a narrative of the case study and did not apply any analysis tools or frameworks. This form of reasoning does not explain why certain aspects are mentioned while others are not.

Figure 5. Links between data collection methods (left-hand side) and data analysis methods (right-hand side) of qualitative (top, n = 95), quantitative (middle, n = 23), and mix-methods publications (bottom, n = 39) in our review. Note that numbers represent the number of links between data collection and data analysis methods, not the number of papers (e.g. in the same paper, ‘interviews’, a data collection method, can be linked to both ‘scenarios’ and ‘content analysis’, which are data analysis methods)

Just 23 publications (14.6%) relied only on quantitative methods. In these quantitative studies, researchers often accessed data from existing databases, which is why we combined data collection methods and data type (e.g. ecological data) in this analysis. Quantitative publications in our review used mostly land use/land cover (LULC) data and surveys as data as sources for their mainly spatial (Schirpke et al. Citation2017), statistical (Mascarenhas et al. Citation2014) or economic (Börner et al. Citation2010) analysis. Only in one quantitative publication, it was unclear to us how the data were collected and how the authors arrived at their results (Appendix B).

About a quarter of the publications (24.8%, n = 39) used a mixed-methods approach (i.e. combined qualitative and quantitative methods to collect and/ or analyze data). The main data collection methods in these publications were interviews, surveys, and literature (e.g. policies, rules, regulations). Mixed-methods publications analyzed data mostly using statistics, content analysis, and framework applications. In order to bring together quantitative and qualitative methods the publications often used multiple data collection and/or data analysis approaches. For example, in their study of PES schemes in the Philippines, Thompson et al. (Citation2017) combined other literature, interviews, socio-economic data, and choice experiments to analyse the data quantitatively with statistical analysis and qualitatively with a content analysis.

Modes of ES governance

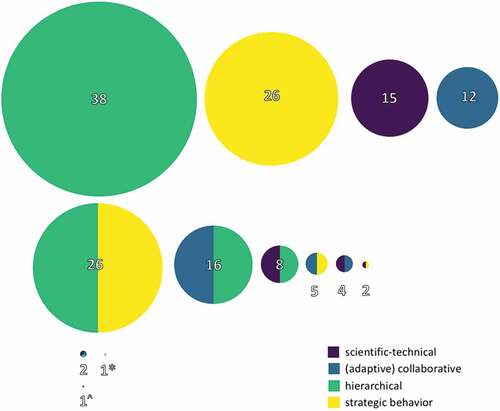

Most publications (58.0%, n = 91) dealt with only a single mode of governance and almost two fifths of the publications (38.9%, n = 51) dealt with two modes of governance (). The most studied mode of governance was hierarchical (59.2%, n = 93), followed by strategic behavior (39.5%, n = 62). When studying two governance modes in one paper, the combination of the hierarchical and strategic behaviour governance modes and of the hierarchical and (adaptive) collaborative governance modes are the most common. This indicates that legal regulations build the frame for the governance mechanisms in place. Only Sarkki et al. (Citation2017) evaluated all four modes of governance by synthesizing 11 case studies and 75 governance proposals across eight European countries.

Figure 6. Occurrence of different governance modes in the reviewed publications (n = 157). The size of the circles illustrates how often the (combination of) governance modes occurred in the reviewed sample, which is also given by the number. 1* represents the one publication combining the three governance modes adaptive, hierarchical and strategic behavior. 1^ represents the one publication combining all four governance modes

From 2006 to 2019, the percentage of papers that examined each of the different governance modes fluctuated annually, but there was no clear directional change towards an increase or decrease in any of governance modes over time, except for (adaptive) collaborative governance, for which the percentage of publications has decreased over time (Appendix B). Until 2010, no publication included scientific-technical governance. Since 2010, all four governance modes appear almost every year with hierarchical governance almost always the strongest and strategic behavioural governance with a stable share of around a quarter.

Our study indicates that ES governance literature has emphasised on hierarchical governance. Most of the literature on hierarchical governance has been concerned with multi-level governance as the interaction between individual governance levels (Gómez-Baggethun et al. Citation2013; Albert et al. Citation2017). A substantive body of literature exists on PES as a governance mechanism combining hierarchical governance in the form of laws initiating strategic behavioural governance through for example market incentives (Leimona et al. Citation2015; To and Dressler Citation2019). Publications on (adaptive) collaborative governance have decreased over time. Some of the literature included governance forms that were challenging to group into the four governance types such as stewardship (Connolly et al. Citation2013) and global governance, such as studies on IPBES (Löfmarck and Lidskog Citation2017).

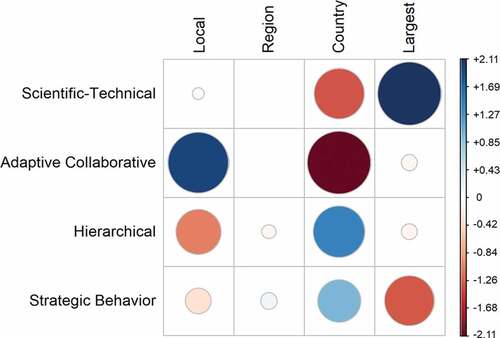

On the smaller levels, scientific-technical governance found least attention, while we identified that the others governance modes were more studied on smaller levels. Adaptive-collaborative governance was well-studied on the local and regional level. Lennox and Gowdy (Citation2014) showed how community-based agricultural management in highland Peru can help to maintain ES in the face of future sustainability challenges. We also found that publications on the global level focus on adaptive-collaborative governance. This is connected with global ES assessments such as the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and the activities of IPBES (Carpenter et al. Citation2006; Beck et al. Citation2014). Hierarchical governance is most studied at the country level which is the level mostly responsible for law making, e.g. Stepniewska et al. (Citation2018) study the capability of the Polish legal system to integrate an ecosystem service approach. The local, regional and country level have most publications on strategic behavior governance.

The data suggest trends across spatial scales in frequency at which governance modes are studied (; chi-squared test, p = 0.016), but we interpret these results with caution due to small sample sizes and low expected values at the supranational-global scale. At the country scale, we found a higher share of studies than expected on hierarchical governance and fewer studies than expected on adaptive-collaborative governance, which might be related to the fact that countries have the power to pass laws which is the archetype of hierarchical governance. At local scales, we found the opposite trend – more studies on adaptive-collaborative governance and fewer studies on hierarchical governance than expected.

Figure 7. Residuals from a chi-square contingency test, where dark blue colours indicate more papers published than expected for a particular governance type at that spatial scale, and dark red colours indicate fewer papers published than expected. The ‘Largest’ scale indicates that supranational and global scales were combined for the analysis, but results in this column should be interpreted with caution since a few expected values were less than five

Discussion

Governance of ES research – multitude of concepts, methods and geographical contexts

The share of governance focused publications in the sea of ES publications has increased from 3.7% to around 5.0% in the studied time period from 2006 to 2019. However, most publications do not focus on ES and governance, but rather use a social-ecological systems perspective. Thus, the literature focusing especially on the governance of ecosystem services rather than on general governance of social-ecological research is limited. Yet, our findings suggest that research on ES governance emerged and started to establish itself in the wider ES research field between 2006 and 2019. As such, our findings are in line with the much larger quantitative review by Droste et al. (Citation2018) who studied the development of research topics in ES research and found that most of their ca. 14,000 reviewed ES publications originate from the natural sciences and aspects such as governance are less covered. One could argue that the increase of ES research is partly due to international science-policy endeavors such as the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), and nowadays IPBES. Despite the fact that major science-policy processes took place during the study period, governance is still not a major topic in ES research.

In our review, the framework suggested by Primmer et al. (Citation2015) served as an analytical tool to reveal what kind of governance modes are emphasized in ES governance research. Our findings support Primmer et al. (Citation2015)’s proposition that hierarchical governance informs the other three governance modes because it is commonly studied together with them. Yet, we recorded overlaps between the governance modes, as several of the empirical studies fit into more than one category – not only between hierarchical governance and the other three modes. Other reviews have reported similar findings (Adhikari and Baral Citation2018). Additionally, our analysis could have benefited other categories, such as separating adaptive and collaborative governance or adding global governance (which we classified in the end as hierarchical governance). However, in our analysis, the four conceptual modes of ecosystem governance as suggested by Primmer et al. (Citation2015) were useful to structure the analysis and to communicate between researchers from various social-scientific backgrounds and traditions. Nevertheless, using different conceptual tools to analyze the governance modes, such as payment schemes, participatory decision-making, and the implementation of laws and regulations can further illustrate the application of the ES governance concept for decision-making and management.

In our review, we found that most ES governance publications were either empirical or partly empirical and about a third were conceptual. This suggests that the field is establishing, and a wider synthesis of the individual case studies has not happened specifically for the specificities of governance of ecosystem services. Publications such as Primmer et al. (Citation2015) aim to conceptualize the specificities of ES governance. Frequently, authors borrow concepts and theories from related fields, such as institutional and ecological economics (Börner et al. Citation2010; Li et al. Citation2016). ES governance is unique form of environmental governance as it focuses not only on the stocks of (natural) resources but also on the flows of services, and therefore highlights the human interdependency with nature. The ES concept has been criticized for its utilitarian understanding of the relationship of nature and society (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021). As such, we recommend studies that elaborate and further study which aspects of ES governance are overlapping with existing governance literature on social-ecological systems and the environment and which aspects such as governance of a dynamic flow and the anthropogenetic focus are specific to the governance of ES and need their own frameworks or models or at least considerations.

Our research indicates that the geographical distribution of ES governance research is reasonably diverse, but still misses perspectives from certain regions in the world. Western Europe, North America, China, Brazil, and Australia are well represented. There was a modest number of studies on Southeast Asia and Central America which mainly focused on PES schemes. However, there were few studies from sub-Saharan African, the Arab Peninsula, and Central Asia, indicating that there we are lacking information and knowledge about the diversity of governance possibilities and challenges for ecosystem services in major parts of the world. While few studies mentioned the knowledge and arrangements in indigenous communities which are often conflicting with main governmental actions (Bebbington Citation2013; Greenhalgh and Hart Citation2015; Nahuelhual et al. Citation2018), no study focused on indigenous or traditional governance. Like this, we can only speculate about the transferability of indigenous and traditional governance of other social-ecological research to the governance of ecosystem services and might lose knowledge and wisdom maintaining or regaining a healthy relationship between humans and nature. This has implications for any science-policy interactions outside Western worldview dominated and intensively studied areas.

Additionally, our findings show that a majority of the publications used qualitative and mixed methods. This is in line with a previous review by Sattler et al. (Citation2018) on methods in ES governance literature. We found that almost a quarter of the reviewed publications did not specify how and from where data were collected. Hanna et al. (Citation2018) also had problems in their review of quantitative indicators of ES to find complete information on the methodological approaches of the reviewed publications. In addition, a remarkable share of publications fails to give precise definitions for governance terms that they use. This lack of coherence was present in both quantitative and qualitative studies. In an interdisciplinary research field such as ES, clearly communicating methodological approaches is critical to allow everybody in the field to follow, understand, and reproduce empirical findings. This implies that both data collection and data analysis methods should be clearly and thoroughly presented in scientific publications. In this sense, future empirical research on ES governance should clearly specify the origin of data and the methods in order to allow other researchers to reproduce and validate published findings.

Limitations

Our study represents a quantitative review of the current English, peer-reviewed scientific articles which brings certain limitations. Deciding to look only at literature published in English excludes research conducted in other languages which also might go hand-in-hand with different governance systems and rationales. Also, our decision to exclude grey literature and non-peer-reviewed scientific articles may have similarly affected our findings. These aspects will have also limited the regional representation of the reviewed studies (cf. ) where we see hardly any study on the African continent, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia.

We limited our search for literature using the search term ‘governance’ and did not include additional terms such as ‘management’, ‘decision-making’, ‘institution’, or ‘government’. This decision has limited our review to literature that self-identifies as governance literature by using the term governance in its title, abstract and/or keywords. We might have excluded literature that deals with specific aspects of ES governance (e.g. management decisions). For example, the decline in publications about adaptive collaborative governance over time might have been a consequence of the search terms that we used. In addition, we have not scrutinized certain concepts within the current ES governance literature, such as power or agency (Keune et al. Citation2013) or different knowledge types including traditional and local knowledge.

The weakness of using an existing conceptual framework is that categories are given and defined. In order to not lose the quantifiable notions of our dataset, we decided to not alter, change or add to the four governance modes. However, this means that some modes would benefit from refinement or sub-categories. We acknowledge that other governance research communities exist, such as the governance of social-ecological systems is working with Ostrom’s diagnostic social-ecological systems framework (Ostrom Citation2009), and might not use the term ‘ecosystem services’ in their work (Partelow Citation2018). However, both research communities might benefit from each other because expertise in both fields is complementary (Vogt et al. Citation2015; Partelow and Winkler Citation2016; Rissman and Gillon Citation2017). Other related literature is the one on policy mix analysis (Barton et al. Citation2013, Citation2017) that uses neither ecosystem services nor governance as a term and is still related.

Conclusion

Our study shows that empirical research on governance of ES is diverse in content, focus and methodological approaches. Yet, ES governance research can contribute to a stronger argument on the need for nature conservation and sustainable development (Hauck et al. Citation2013; Primmer et al. Citation2015; Albrecht and Ratamäki Citation2016). ES research could contribute to transformative sustainability processes by stating normative goals (e.g. maintaining ES for the sake of biodiversity conservation) and to explore its full potential to facilitate transdisciplinary processes (Abson et al. Citation2014).

Additionally, using the reviewed ES governance research, decision-makers can tap into a pool of knowledge and experiences both in science and practice on how to use and integrate the different governance modes. In addition, documenting and learning from ‘bright spots’ could help to effectively link scientific research to practitioners and decision-makers (Bennett et al. Citation2016; Cinner et al. Citation2016; Cvitanovic and Hobday Citation2018). Bright spots would be situations in which the governance of ES achieved an improvement of the quality and status of ES and the environment. By systematically identifying and documenting positive examples, barriers and how to overcome them (Laurans et al. Citation2013; Lautenbach et al. Citation2019), researchers could pinpoint key principles for the governance of ES that would help guide decision-makers and practitioners in their interventions.

Lastly, the wider ES research field has so far paid less attention to the governance of human activities and their impact on the environment and on ES (Seppelt et al. Citation2011; Abson et al. Citation2014; Chaudhary et al. Citation2015). Increasing acknowledgment of the complexity of governance systems and their impacts on the other parts of the ES cascade could help to augment research both specifically on governance of ES and on the interconnection between ecological and social systems. In addition, ES governance research will contribute to the understanding that the pure provision of scientific knowledge about the status of ES will not be enough to reverse the trend of the deteriorating status of ecosystems. Other knowledge types such as normative, traditional, and transformative knowledge will be necessary to understand how humans govern ES in order to achieve sustained and positive change (Brandt et al. Citation2013; Von Wehrden et al. Citation2017).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abson DJ, von Wehrden H, Baumgärtner S, Fischer J, Hanspach J, Härdtle W, Heinrichs H, Klein AM, Lang DJ, Martens P, et al. 2014. Ecosystem services as a boundary object for sustainability. Ecol Econ. 103:29–37. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.012.

- Adhikari S, Baral H. 2018. Governing forest ecosystem services for sustainable environmental governance: a review. Environments. 5(5):53. doi:10.3390/environments5050053.

- Albert C, von Haaren C, Othengrafen F, Krätzig S, Saathoff W. 2017. Scaling policy conflicts in ecosystem services governance: a framework for spatial analysis. J Environ Policy Plann. 19(5):574–592. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1075194.

- Albrecht E, Ratamäki O. 2016. Effective arguments for ecosystem services in biodiversity conservation – a case study on finnish peatland conservation. Ecosyst Serv. 22:41–50. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.09.003.

- Barton DN, Benavides K, Chacon-Cascante A, Le Coq J-F, Quiros MM, Porras I, Primmer E, Ring I. 2017. Payments for ecosystem services as a policy mix: demonstrating the institutional analysis and development framework on conservation policy instruments: discuss payments for ecosystem services as a policy mix. Environ Policy Governance. 27(5):404–421. doi:10.1002/eet.1769.

- Barton DN, Blumentrath S, Rusch G. 2013. Policyscape—A spatially explicit evaluation of voluntary conservation in a policy mix for biodiversity conservation in Norway. Soc Nat Resour. 26(10):1185–1201. doi:10.1080/08941920.2013.799727.

- Barton DN, Kelemen E, Dick J, Martin-Lopez B, Gómez-Baggethun E, Jacobs S, Hendriks CMA, Termansen M, García- Llorente M, Primmer E, et al. 2018. (dis) integrated valuation – assessing the information gaps in ecosystem service appraisals for governance support. Ecosyst Serv. 29:529–541. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.10.021.

- Bebbington DH. 2013. Extraction, inequality and indigenous peoples: insights from Bolivia. Environ Sci Policy. 33:438–446. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.07.027.

- Beck S, Borie M, Chilvers J, Esguerra A, Heubach K, Hulme M, Lidskog R, Lövbrand E, Marquard E, Miller C, et al. 2014. Towards a reflexive turn in the governance of global environmental expertise. The cases of the IPCC and the IPBES. GAIA - Ecol Perspect Sci Soc. 23(2):80–87. doi:10.14512/gaia.23.2.4.

- Bennett EM, Solan M, Biggs R, Mcphearson T, Norström AV, Olsson P, Pereira L, Peterson GD, Raudsepp-hearne C, Biermann F, et al. 2016. Bright spots : seeds of a good Anthropocene. Front Ecol Environ. 14(8):441–448. doi:10.1002/fee.1309.

- Binder CR, Hinkel J, Bots PWG, Pahl-Wostl C. 2013. Comparison of frameworks for analyzing social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc. 18:4. doi:10.5751/ES-05551-180426.

- Borgström S, Elmqvist T, Angelstam P, Alfsen-Norodom C. 2006. Scale mismatches in management of urban landscapes. Ecol Soc. 11(2):16. doi:10.5751/ES-01819-110216.

- Börner J, Wunder S, Wertz-Kanounnikoff S, Tito MR, Pereira L, Nascimento N. 2010. Direct conservation payments in the Brazilian Amazon: scope and equity implications. Ecol Econ. 69(6):1272–1282. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.003.

- Brandt P, Ernst A, Gralla F, Luederitz C, Lang DJ, Newig J, Reinert F, Abson DJ, von Wehrden H. 2013. A review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science. Ecol Econ. 92:1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.04.008.

- Burkhard B, de Groot R, Costanza R, Seppelt R, Jørgensen SE, Potschin M. 2012. Solutions for sustaining natural capital and ecosystem services. Ecol Indic. 21:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.03.008.

- Carmen E, Watt A, Carvalho L, Dick J, Fazey I, Garcia-Blanco G, Grizzetti B, Hauck J, Izakovicova Z, Kopperoinen L, et al. 2018. Knowledge needs for the operationalisation of the concept of ecosystem services. Ecosyst Serv. 29:441–451. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.10.012.

- Carpenter SR, Bennett EM, Peterson GD. 2006. Scenarios for ecosystem services: an overview. Ecol Soc. 11(1):art29. doi:10.5751/ES-01610-110129.

- Cash DW, Adger WN, Berkes F, Garden P, Lebel L, Olsson P, Pritchard L, Young OR. 2006. Scale and cross-scale dynamics: governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecol Soc. 11(2):8. doi:10.5751/ES-01759-110208.

- Chan KM, Gould RK, Pascual U. 2018. Relational values: what are they, and what’s the fuss about? Current Opin Environ Sustain. 35:A1–A7. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.11.003.

- Chan KMA, Balvanera P, Benessaiah K, Chapman M, Díaz S, Gómez-Baggethun E, Gould R, Hannahs N, Jax K, Klain S, et al. 2016. Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 113(6):1462–1465. doi:10.1073/pnas.1525002113.

- Chapin FS, Sommerkorn M, Robards MD, Hillmer-Pegram K. 2015. Ecosystem stewardship: a resilience framework for arctic conservation. Global Environ Change. 34:207–217. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.07.003.

- Chaudhary S, McGregor A, Houston D, Chettri N. 2015. The evolution of ecosystem services: a time series and discourse-centered analysis. Environ Sci Policy. 54:25–34. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.04.025.

- Cinner JE, Huchery C, MacNeil MA, Graham NAJ, McClanahan TR, Maina J, Maire E, Kittinger JN, Hicks CC, Mora C, et al. 2016. Bright spots among the world’s coral reefs. Nature. 535(7612):416–419. doi:10.1038/nature18607.

- Connolly JJ, Svendsen ES, Fisher DR, Campbell LK. 2013. Organizing urban ecosystem services through environmental stewardship governance in New York City. Landsc Urban Plan. 109(1):76–84. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.07.001.

- Cork SJ, Peterson GD, Bennett EM, Petschel-Held G, Zurek M. 2006. Synthesis of the storylines. Ecol Soc. 12(2):11. doi:10.5751/ES-01798-110211.

- Costanza R, D’Arge R, de Groot RS, Farber SC, Grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, O’Neill RV, Paruelo J, et al. 1997. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature. 387(6630):253–260. doi:10.1038/387253a0.

- Costanza R, de Groot R, Braat L, Kubiszewski I, Fioramonti L, Sutton P, Farber S, Grasso M. 2017. Twenty years of ecosystem services: how far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst Serv. 28:1–16. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.09.008.

- Cvitanovic C, Hobday AJ. 2018. Building optimism at the environmental science-policy-practice interface through the study of bright spots. Nat Commun. 9(1):3466. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05977-w.

- de Groot RS, Wilson M, Boumans RMJ. 2002. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol Econ. 41(3):393–408. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7.

- Díaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Larigauderie A, Adhikari JR, Arico S, Báldi A, et al. 2015. The IPBES conceptual framework — connecting nature and people. Current Opin Environ Sustain. 14:1–16. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002.

- Díaz S, Pascual U, Stenseke M, Martín-López B, Watson RT, Molnár Z, Hill R, Chan KMA, Baste IA, Brauman KA, et al. 2018. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science. 359(6373):270–272. doi:10.1126/science.aap8826.

- Droste N, D’Amato D, Goddard JJ. 2018. Where communities intermingle, diversity grows – the evolution of topics in ecosystem service research. PLoS ONE. 13(9):7–8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204749.

- Ekroos J, Leventon J, Fischer J, Newig J, Smith HG. 2017. Embedding evidence on conservation interventions within a context of multilevel governance. Conserv Lett. 10(1):139–145. doi:10.1111/conl.12225.

- Ernstson H, Barthel S, Andersson E, Borgström S. 2010. Scale-crossing brokers and network governance of urban ecosystem services: the case of stockholm. Ecol Soc. 15(4):18. doi:10.5751/ES-03692-150428.

- Folke C, Biggs R, Norström AV, Reyers B, Rockström J. 2016. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol Soc. 21(3):art41. doi:10.5751/ES-08748-210341.

- Gómez-Baggethun E, Kelemen E, Martín-López B, Palomo I, Montes C. 2013. Scale Misfit in ecosystem service governance as a source of environmental conflict. Soc Nat Resour. 26(10):1202–1216. doi:10.1080/08941920.2013.820817.

- Gómez-Baggethun E, Muradian R. 2015. In markets we trust? Setting the boundaries of market-based instruments in ecosystem services governance. Ecol Econ. 117:217–224. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.03.016.

- Greenhalgh S, Hart G. June 2015. Mainstreaming ecosystem services into policy and decision-making: lessons from New Zealand’s journey. Int J Biodivers Sci, Ecosyst Serv Manage 11(3):1–11. doi:10.1080/21513732.2015.1042523.

- Guerry AD, Polasky S, Lubchenco J, Chaplin-Kramer R, Daily GC, Griffin R, Ruckelshaus M, Bateman IJ, Duraiappah A, Elmqvist T, et al. 2015. Natural capital and ecosystem services informing decisions: from promise to practice. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 112(24):7348–7355. doi:10.1073/pnas.1503751112.

- Haines-Young R, Potschin M. 2010. The links between biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being. In: Raffaelli DG, Frid CLJ, editors. Ecosystem ecology: a new synthesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; p. 110–139.

- Hanna DEL, Tomscha SA, Ouellet Dallaire C, Bennett EM. 2018. A review of riverine ecosystem service quantification: research gaps and recommendations. J Appl Ecol. 55(3):1299–1311. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13045.

- Hauck J, Görg C, Varjopuro R, Ratamäki O, Jax K. 2013. Benefits and limitations of the ecosystem services concept in environmental policy and decision making: some stakeholder perspectives. Environ Sci Policy. 25:13–21. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.08.001.

- Huth N, Possingham HP. 2011. Basic ecological theory can inform habitat restoration for woodland birds. J Appl Ecol. 48(2):293–300. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01936.x.

- IPBES. 2018. Summary for policymakers of the regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Europe and Central Asia of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn (Germany). M. Fischer, M. Rounsevell, A. Torre-Marin Rando, A. Mader, A. Church, M. Elbakidze, V. Elias, T. Hahn, P. A. Harrison, J. Hauck, B. Martin-Lopez, I. Ring, C. Sandström, I. Sousa Pinto, P. Visconti, N. E. Zimmermann, and M. Christie, editors. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat; p. 48. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3237428.

- Jacobs S, Dendoncker N, Martín-López B, Barton DN, Gomez-Baggethun E, Boeraeve F, McGrath FL, Vierikko K, Geneletti D, Sevecke KJ, et al. 2016. A new valuation school: integrating diverse values of nature in resource and land use decisions. Ecosyst Serv. 22:213–220. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.11.007.

- Jax K, Furman E, Saarikoski H, Barton DN, Delbaere B, Dick J, Duke G, Görg C, Gómez-Baggethun E, Harrison PA, et al. 2018. Handling a messy world: lessons learned when trying to make the ecosystem services concept operational. Ecosyst Serv. 29:415–427. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.08.001.

- Kabisch N. 2015. Ecosystem service implementation and governance challenges in urban green space planning—The case of Berlin, Germany. Land Use Policy. 42:557–567. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.09.005.

- Kaye-Zwiebel E, King E. 2014. Kenyan pastoralist societies in transition: varying perceptions of the value of ecosystem services. Ecol Soc. 19(3):art17. doi:10.5751/ES-06753-190317.

- Keune H, Bauler T, Wittmer H. 2013. Ecosystem services governance: managing complexity? In: Jacobs S, Dendoncker N, Keune H, editors. Ecosystem services: global issues, local practices. Amsterdam (Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York, Oxford, Paris, San Diego, San Fransico, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo): Elsevier; p. 135–155.

- Kooiman J. 2003. Governing as governance. London: SAGE.

- Laurans Y, Rankovic A, Billé R, Pirard R, Mermet L. 2013. Use of ecosystem services economic valuation for decision making: questioning a literature blindspot. J Environ Manage. 119:208–219. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.01.008.

- Lautenbach S, Mupepele A-C, Dormann CF, Lee H, Schmidt S, Scholte SSK, Seppelt R, van Teeffelen AJA, Verhagen W, Volk M. 2019. Blind spots in ecosystem services research and challenges for implementation. Reg Environ Change. 19(8):2151–2172. doi:10.1007/s10113-018-1457-9.

- Legagneux P, Casajus N, Cazelles K, Chevallier C, Chevrinais M, Guéry L, Jacquet C, Jaffré M, Naud M-J, Noisette F, et al. 2018. Our house is burning: discrepancy in climate change vs. biodiversity coverage in the media as compared to scientific literature. Front Ecol Evol. 5. doi:10.3389/fevo.2017.00175.

- Leimona B, van Noordwijk M, de Groot R, Leemans R. 2015. Fairly efficient, efficiently fair: lessons from designing and testing payment schemes for ecosystem services in Asia. Ecosyst Serv. 12:16–28. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.12.012.

- Lennox E, Gowdy J. 2014. Ecosystem governance in a highland village in Peru: facing the challenges of globalization and climate change. Ecosyst Serv. 10:155–163. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.007.

- Li R, van den Brink M, Woltjer J. 2016. Rules for the governance of coastal and marine ecosystem services: an evaluative framework based on the IAD framework. Land Use Policy. 59:298–309. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.09.008.

- Löfmarck E, Lidskog R. 2017. Bumping against the boundary: IPBES and the knowledge divide. Environ Sci Policy. 69:22–28. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2016.12.008.

- Loft L, Mann C, Hansjürgens B. 2015. Challenges in ecosystem services governance: multi-levels, multi-actors, multi-rationalities. Ecosyst Serv. 16:150–157. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.11.002.

- Mascarenhas A, Ramos TB, Haase D, Santos R. 2014. Integration of ecosystem services in spatial planning: a survey on regional planners’ views. Landsc Ecol. 29(8):1287–1300. doi:10.1007/s10980-014-0012-4.

- Meadowcroft J. 2002. Politics and scale: some implications for environmental governance. Landsc Urban Plan. 61(2–4):169–179. doi:10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00111-1.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: general synthesis. Washington DC: Island Press and World Resources Institute.

- Muradian R, Gómez-Baggethun E. 2021. Beyond ecosystem services and nature’s contributions: is it time to leave utilitarian environmentalism behind? Ecol Econ. 185:107038. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107038.

- Nahuelhual L, Saavedra G, Henríquez F, Benra F, Vergara X, Perugache C, Hasen F. 2018. Opportunities and limits to ecosystem services governance in developing countries and indigenous territories: the case of water supply in Southern Chile. Environ Sci Policy. 86:11–18. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.04.012.

- Newig J, Fritsch O. 2009. Environmental governance: participatory, multi-level - and effective? Environ Policy Governance. 19(3):197–214. doi:10.1002/eet.509.

- Olsson P, Folke C, Hughes TP. 2008. Navigating the transition to ecosystem-based management of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105(28):9489–9494. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706905105.

- Olsson P, Gunderson LH, Carpenter SR, Ryan P, Lebel L, Folke C, Holling CS. 2006. Shooting the rapids : navigating transitions to A. Ecol Soc. 11(1):18. doi:10.5751/ES-01595-110118.

- Ostrom E. 2009. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Sci (New York, NY). 325(5939):419–422. doi:10.1126/science.1172133.

- Paavola J, Hubacek K. 2013. Ecosystem services, governance, and stakeholder participation: an introduction. Ecol Soc. 18(4):art42. doi:10.5751/ES-06019-180442.

- Pahl-Wostl C. 2009. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environ Change. 19(3):354–365. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001.

- Paloniemi R, Vilja V. 2009. Changing ecological and cultural states and preferences of nature conservation policy: the case of nature values trade in South-Western Finland. J Rural Stud. 25(1):87–97. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.06.004.

- Partelow S. 2018. A review of the social-ecological systems framework: applications, methods, modifications, and challenges. Ecol Soc. 23(4):art36. doi:10.5751/ES-10594-230436.

- Partelow S, Winkler KJ. 2016. Interlinking ecosystem services and Ostrom’s framework through orientation in sustainability research. Ecol Soc. 21(3):art27. doi:10.5751/ES-08524-210327.

- Pasgaard M, Van Hecken G, Ehammer A, Strange N. 2017. Unfolding scientific expertise and security in the changing governance of ecosystem services. Geoforum. 84:354–367. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.02.001.

- Potschin-Young M, Haines-Young R, Görg C, Heink U, Jax K, Schleyer C. 2018. Understanding the role of conceptual frameworks: reading the ecosystem service cascade. Ecosyst Serv. 29:428–440. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.05.015.

- Primmer E. 2011. Analysis of institutional adaptation: integration of biodiversity conservation into forestry. J Clean Prod. 19(16):1822–1832. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.04.001.

- Primmer E, Jokinen P, Blicharska M, Barton DN, Bugter R, Potschin M. 2015. Governance of ecosystem services: a framework for empirical analysis. Ecosyst Serv. 16:158–166. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.05.002.

- Ring I, Barton DN. 2015. Economic instruments in policy mixes for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem governance. In: Martinez-Alier J, editor. Handbook of ecological economics. Glos, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; p. 413–449.

- Rissman AR, Gillon S. 2017. Where are ecology and biodiversity in social-ecological systems research? A review of research methods and applied recommendations. Conserv Lett. 10(1):86–93. doi:10.1111/conl.12250.

- Rival L. 2010. Ecuador’s Yasuní-ITT Initiative: the old and new values of petroleum. Ecol Econ. 70(2):358–365. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.09.007.

- Rival L, Muradian R. 2013. Introduction: governing the provision of ecosystem services. In: Muradian R, Rival L, editors. Governing the provision of ecosystem services. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands (Dordrecht); p. 1–17.

- Rodríguez-de-Francisco JC, Duarte-Abadía B, Boelens R. 2019. Payment for ecosystem services and the water-energy-food nexus: securing resource flows for the affluent? Water. 11(6):1143. doi:10.3390/w11061143.

- Ruckelshaus M, McKenzie E, Tallis H, Guerry A, Daily G, Kareiva P, Polasky S, Ricketts T, Bhagabati N, Wood SA, et al. 2015. Notes from the field: lessons learned from using ecosystem service approaches to inform real-world decisions. Ecol Econ. 115:11–21. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.07.009.

- Saarikoski H, AAkerman M, Primmer E. 2012. The challenge of governance in regional forest planning: an analysis of participatory forest program processes in Finland. Soc Nat Resour. 25(7):667–682. doi:10.1080/08941920.2011.630061.

- Sandström C. 2009. Institutional dimensions of comanagement: participation, power, and process. Soc Nat Resour. 22(3):230–244. doi:10.1080/08941920802183354.

- Sarkki S, Jokinen M, Nijnik M, Zahvoyska L, Abraham E, Alados C, Bellamy C, Bratanova-Dontcheva S, Grunewald K, Kollar J, et al. 2017. Social equity in governance of ecosystem services: synthesis from European treeline areas. Clim Res. 73(1–2):31–44. doi:10.3354/cr01441.

- Sattler C, Loft L, Mann C, Meyer C. 2018. Methods in ecosystem services governance analysis: an introduction. Ecosyst Serv. 34:(November):155–168. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.11.007.

- Schirpke U, Marino D, Marucci A, Palmieri M, Scolozzi R. 2017. Operationalising ecosystem services for effective management of protected areas: experiences and challenges. Ecosyst Serv. 28:105–114. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.10.009.

- Seppelt R, Dormann CF, Eppink FV, Lautenbach S, Schmidt S. 2011. A quantitative review of ecosystem service studies: approaches, shortcomings and the road ahead. J Appl Ecol. 48(3):630–636. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01952.x.

- Stępniewska M, Zwierzchowska I, Mizgajski A. 2018. Capability of the Polish legal system to introduce the ecosystem services approach into environmental management. Ecosyst Serv. 29:271–281. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.02.025.

- Strauch AM, Rurai MT, Almedom AM. 2016. Influence of forest management systems on natural resource use and provision of ecosystem services in Tanzania. J Environ Manage. 180:35–44. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.05.004.

- Suhardiman D, Wichelns D, Lestrelin G, Thai Hoanh C, Hoanh CT. 2013. Payments for ecosystem services in Vietnam: market-based incentives or state control of resources? Ecosyst Serv. 5:94–101. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.06.001.

- Sutherland WJ, Pullin AS, Dolman PM, Knight TM. 2004. The need for evidence-based conservation. Trends Ecol Evol. 19(6):305–308. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.018.

- Swyngedouw E. 2005. Governance Innovation and the citizen: the janus face of governance-beyond-the-state. Urban Stud. 42(11):1991–2006. doi:10.1080/00420980500279869.

- Thompson BS, Primavera JH, Friess DA. 2017. Governance and implementation challenges for mangrove forest Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES): empirical evidence from the Philippines. Ecosyst Serv. 23:146–155. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.12.007.

- To P, Dressler W. 2019. Rethinking ‘Success’: the politics of payment for forest ecosystem services in Vietnam. Land Use Policy. 81:582–593. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.010.

- Van Hecken G, Bastiaensen J. 2010. Payments for ecosystem services in Nicaragua: do market-based approaches work? Dev Change. 41(3):421–444. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01644.x.

- Vatn A. 2005. Institutions and the environment. Cheltenham (UK; Northampton, MA, USA): Edward Elgar.

- Vogt JM, Epstein GB, Mincey SK, Fischer BC, McCord P. 2015. Putting the “E” in SES: unpacking the ecology in the Ostrom social-ecological system framework. Ecol Soc. 20(1):art55. doi:10.5751/ES-07239-200155.

- von Wehrden H, Luederitz C, Leventon J, Russell S. 2017. Methodological challenges in sustainability science: a call for method plurality, procedural rigor and longitudinal research. Challenges Sustain. 5:1. doi:10.12924/cis2017.05010035.

- Winkler KJ, Hauck J. 2019. Landscape stewardship for a German UNESCO biosphere reserve: a network approach to establishing stewardship governance. Ecol Soc. 24(3):art12. doi:10.5751/ES-10982-240312.

- Young OR. 2013. On environmental governance: sustainability, efficiency, and equity. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Young RF, McPherson EG. 2013. Governing metropolitan green infrastructure in the United States. Landsc Urban Plan. 109(1):67–75. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.09.004.