?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The evaluation of cultural ecosystem services based on the exploration of social values (SV) is a powerful tool to describe visitors’ perceptions of a natural landscape. A natural setting in the southwest of Mexico City lacks effective management due to insufficient understanding of visitors’ behavior and their interactions with natural resources. We profiled two visitor groups, rock climbers and non-rock climbers, assessed the SV they ascribed to a popular natural recreational park, and explored associations between SV and particular landscape features. Data collection was based on field observations, questionnaires, and a photograph-based approach. Cross tabulations, chi-square tests, and basic map algebra were used to process data. Results showed statistical differences between the two visitor groups concerning park use, but not in the perception of SV. The main SV people ascribe to the park are natural, recreational, and productive values, although results differ depending on the location of the park. Landscape features such as forest cover, remoteness, elevation, and rock formations are strongly interlinked to specific SV. This study can contribute towards an understanding of differentiated park use and perceptions of cultural ecosystem services by visitor groups. This can be integrated into management plans for recreational parks in Mexico.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

Cultural ecosystem services (CES), such as sense of place, cultural heritage, recreation, ecotourism, educational, aesthetic, and religious aspects of life, are social and spiritual benefits obtained from natural or modified surroundings that contribute essentially to human wellbeing (MEA Citation2005). While CES are regarded as part of the general ecosystem services (ES) typology, they distinguish themselves from other services because they heavily embrace the human environment co-production approach involved in their creation (Fischer and Eastwood Citation2016). CES are social constructs intrinsically linked to people’s held values (Dickinson and Hobbs Citation2017). They are hardly replicable because they are formed by the individual and the value they assign to a specific place (Scholte et al. Citation2015; Fischer and Eastwood Citation2016). This applies to CES in green urban areas as well, which, despite having been modified by humans, offer benefits that contribute to the inhabitants’ physical and mental health (Langemeyer et al. Citation2015; Dickinson and Hobbs Citation2017).

Various utilitarian approaches, usually measuring ES in monetary units, have been used to economically quantify the benefits people obtain from nature. CES can be valued through non-market methods such as contingent valuation, choice experiments, deliberative valuation, hedonic pricing, or travel cost methods (Costanza et al. Citation2017; Cheng et al. Citation2019). However, for many non-use values such as spiritual, aesthetic, inspirational uses and sense of place, some of these methods are regarded as insufficient because they cannot capture completely the spectrum of values for which people perceive the meaning of nature (Milcu et al. Citation2013; Langemeyer et al. Citation2015). Methods for assessing non-use values include observation approaches, document research, expert-based approaches, in-depth interviews, focus groups, questionnaires, photo evaluation methods, and mapping methods (Schmidt et al. Citation2017). Nowadays, these methods are frequently combined with geographical information systems (GIS) tools to provide location-based research possibilities to link people’s held values and the assigned value of green spaces and landscapes (Hashimoto et al. Citation2015; Nahuelhual et al. Citation2017; Ridding et al. Citation2018).

One way to explore CES within urban green spaces is to combine GIS tools and the explicit consideration of social values (SV) (Sherrouse et al. Citation2011). SV are the aggregation of individual valuations, which reflect preferences and choices, and can be understood as a value for society in terms of its contribution to welfare and wellbeing (Kenter et al. Citation2015). They are the non-market values perceived by ecosystem stakeholders that promote good social relations (Sherrouse et al. Citation2017) or the perceived qualities carried by natural environments (Van Riper et al. Citation2012). To operationalize this concept, Brown and Reed (Citation2000) developed a SV typology table, listing and briefly defining various SV. It is seen as an effective form of participatory and integrated valuation that has been used in multiple international studies (i.e. Sherrouse et al. Citation2011; Van Riper et al. Citation2012; Rall et al. Citation2017).

Studies on CES have been performed primarily in developed countries, although several have also been undertaken in developing countries and economies (Christie et al. Citation2012). In Mexico, Perez-Verdin et al. (Citation2016) identified 17 studies on economic valuation, specifically on CES. However, the evaluation of CES through SV using qualitative research and GIS is a novel approach in Mexico. We applied this approach in a natural setting in the southwest of Mexico City to help bridge the gap between outdoor recreation and ES or land-use planning in this region (Pérez-Campuzano et al. Citation2016). Integrating place-specific perceptions of SV can help address the challenges associated with understanding multiple and sometimes competing values and goals for land management (Raymond and Brown Citation2006). Our study area is a natural park that provides important CES to the capital city, but it lacks effective management through the local community due to the absence of stakeholders in the decision-making process (Almeida-Leñero et al. Citation2007) and to an insufficient understanding of visitors and their interactions with the park’s resources Jujnovsky et al. (Citation2013). A novel aspect of our research is the consideration of rock climbers because the park offers exceptional settings for rock climbing.

Rock climbing belongs to the family of recreation-based CES (Kulczycki Citation2014). Climbers interact with the rock and the surrounding area through experiences of adventure, short-term isolation, and personal freedom, which ultimately influences their perceptions of social values (Rossiter Citation2007; Zhang and McDowell Citation2020). Non-climbers interact with the surrounding rock climbing settings as well but perceive other cultural benefits such as aesthetics, education, spirituality, and, in many cases, cultural heritage (Felsch Citation2009; Nydal Citation2018). We included in our research these two visitor groups since these groups’ perceptions of SV can improve management decisions (Ives and Kendal Citation2014). The variety of perceived meanings, degrees of experience and use values forms a rationale for better understanding the social value of rock climbing sites in recreational areas (Scarpa and Thiene Citation2005).

Drawing on a case study in Mexico City and Los Dinamos Recreational Park, the objectives of the research are: 1) to construct a visitor profile, distinguishing between rock climbers and non-rock climbers and to compare how they interact with a natural park; 2) to describe through a place-based approach the SV they attribute to a natural park, and; 3) to explore connections between perceived SV and particular landscape features to gain a deeper understanding of the CES. To explore these objectives, we used on-field observations, questionnaires, and spatially-referenced photographs.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study area

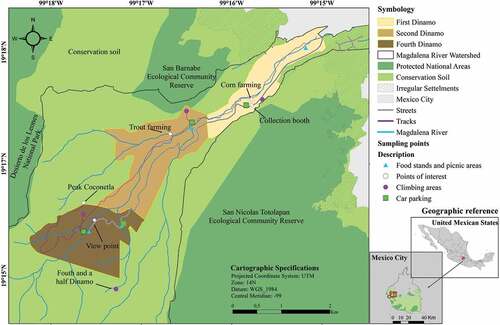

The Magdalena River Watershed (MRW) is found southwest of Mexico City. About 58% of Mexico City´s territory is considered conservation soil, 9.3% of which belongs to certain conservation area categories, while 4% comprises the MRW (Almeida-Leñero et al. Citation2007; Galeana Pizaña et al. Citation2009). MRW covers an area of about 30 km2, with elevations between 2,400 and 3,800 meters above sea level (Jujnovsky et al. Citation2010). The climate is sub-humid in the lower part (2,400–2,800 m), semi-cold, sub-humid in mid-elevations (2,800–3,600 m), and semi-cold in the highest part (above 3,600 m) (Montes et al. Citation2013). As altitude increases, so does annual precipitation, from 900 to 1,300 mm (Jujnovsky et al. Citation2010). The annual temperature ranges between 9°C to 15°C (Montes et al. Citation2013). The watershed has a vegetation cover of 60%, comprising oak, fir, and pine trees for each of the three altitude zones, respectively (Almeida-Leñero et al. Citation2007). The Magdalena River is 21.6 km long and emerges on the mountain Cerro de Las Cruces where it flows 13 km through the forests of La Cañada until it reaches the peri-urban areas, where it continues through underground pipes (Montes et al. Citation2013). This watershed is unique because of its natural riparian ecosystem and forest areas, which contribute to regulating and supporting ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, groundwater recharge, flood control and biodiversity, among others (Galeana Pizaña et al. Citation2009; Jujnovsky et al. Citation2010). It is also a famous eco-touristic and recreational center because of its scenic beauty and cultural heritage (Almeida-Leñero et al. Citation2007).

Within the MRW, we delimited our study area to the parts that are mainly used for recreational purposes and named it Los Dinamos Recreational Park (LDRP). We opted for our own nomenclature because different names have been given to this area, all of which occupy roughly the same territory (Jujnovsky et al. Citation2013). The area has had administrative issues, including an undefined legal status (whether it is a natural protected area), and uncontrolled tourism (Almeida-Leñero et al. Citation2007). The recreational attractions are mainly located along the only paved road that provides visitors with unrestricted access in and out of the valley.

For the delimitation of LDRP (), we considered the following socio-geographic characteristics: 1) limits of the MRW, 2) hypsometry, 3) irregular human settlements, and 4) manually collected GPS points (WGS 84) that represent the limits of the areas used for recreational activities. The data and layers of points 1 to 3 were taken from the Geographic Atlas of Soil Conservation of Mexico City (Citation2012). We estimated an area of 538 ha for LDRP, which represents 18% of the MRW, and is managed exclusively by the Magdalena Atlitic agrarian community. Then, we identified three sub-polygons according to the landscape characteristics such as steep, altitude, climate, and vegetation cover. We named the sub-polygons after their socio-cultural background: First, Second, and Fourth Dinamo. There are smaller and lesser-known spots called Third Dinamo (a small private tourism project within the Second Dinamo) and another climbing site called Fourth and a Half (a small remote spot). However, we focused on the areas easily identifiable for public use and accessible via the only paved road.

2.2. On-site observation and sampling method

In preparation for data collection, we conducted on-site observations from late 2017 to the beginning of 2018. We identified the strategic points to conduct the survey, observed and gathered geo-referenced information on recreational activities and productive settings and took geo-referenced photographs. After finishing this process, we designed, piloted and finalized the questionnaire.

According to Martínez-Cruz and Sainz-Santamaría (Citation2017) about 145,000 people visit LDRP annually. Following Rea and Parker (Citation2014), we estimated the sample size (n) for the area as:

where MEp is the margin of error in terms of proportions set at 0.1 (10%). We chose a lower confidence interval because of limited financial resources. Za is the Z score for various levels of confidence (α), set at 1.96, and p is the sample proportion set at 0.5. This 50% proportion refers to the two visitor groups we mainly observed in this park: rock climbers and non-rock climbers. Therefore, n was equal to 95, but we rounded it up to 100. The number of questionnaires was weighted based on the sample size per group. Visitors were randomly selected close to the main attraction sites, including at rock-climbing spots. If someone refused to answer the questionnaire, we randomly selected another person to get his/her perceptions. Individuals had to be 18 years or older, willing to participate, and, at the time of the face-to-face interviews, located in one of the predefined polygons. The survey period comprised nine months (February – October 2018). We considered the rainy season (June – October) and the dry season (November – May). Based on our previous observations, our one-day visits were carried out on weekends, as this is when the park has the most visitors.

2.3. Design of the questionnaire and data analysis

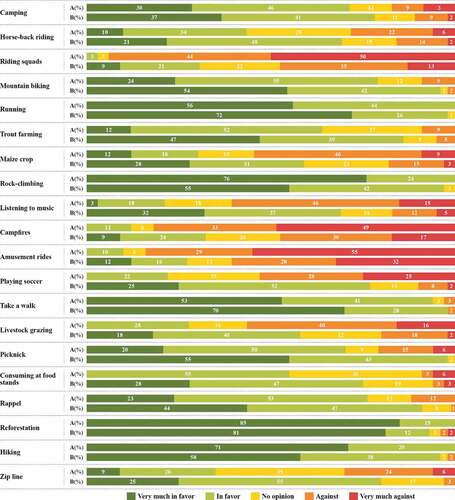

The questionnaire was divided into three sections with a total of 22 items. In the first section, we addressed five questions about visitors’ use, primary purpose of the visit, knowledge of land ownership, and their opinion on LDRP. We used qualitative polytomous variables, where respondents were asked to select one answer. Only one question, addressing whether or not visitors agree with the activities practiced in the park, was based on a Likert-type scale.

In the second section, we presented three tasks to address the perception of different SV through 1) identifying SV, 2) allocating a hypothetical budget among SV, and 3) implementing a photograph-based evaluation. At the beginning of the first task, we aimed to familiarize the respondents with the eight predefined SV, which we selected following the approach of Brown and Reed (Citation2000) and their SV typology by considering the characteristics and existing literature on our research area (). We named the SV and wrote a statement relative to the SV, based on which respondents were asked to identify the three most important SV they associated with the LDRP. We opted for a multiple response format because of the variety of landscape values and individual preferences (Brown and Brabyn Citation2012; Ives and Kendal Citation2014).

Table 1. Social value definitions (adapted from Brown and Reed Citation2000) used in the survey

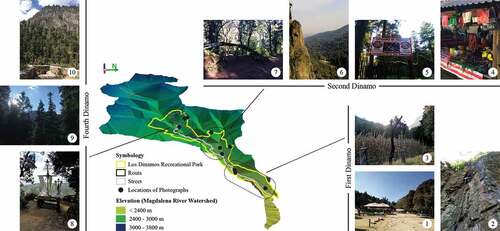

Next, we presented six hypothetical environmental projects, each enhancing one SV, in which visitors had to allocate 100 Mexican Pesos to demonstrate their willingness to donate to projects of their interest. This stated preference question is particularly suitable for ascertaining subtle benefits of the environment such as CES and ES in developing countries (Kenter et al. Citation2011). In our case, we addressed hypothetical environmental projects that aim to enhance educational, spiritual, aesthetics, cultural-historic, recreational, or natural values. For only this exercise, we excluded the productive value because it does not entirely fit the ecosystem service definition. However, productive values were part of the overall uses of LDRP. We also merged the natural and future values for easier understanding. In the third task, we handed the visitors ten photographs () previously taken in every polygon of the park so that they ascribe SV to them. The rationale of this approach is because personal theoretical constructs are not always easily expressed through verbal means (Sherren et al. Citation2010), especially in Mexico, where education levels range from illiterate to university level. The number of photographs was chosen consciously to encourage participation and avoid fatigue (Tew et al. Citation2019). The places where photographs were taken had to meet two criteria: a) a balanced distribution of photographs between the three polygons, which should reflect the natural landscape, recreational and productive activities, and b) cultural aspects.

Figure 2. Geo-referenced photographs within the sub-polygons. The Magdalena River Watershed is rotated 90° to the left (east) to highlight visually the steepness of the valley and display the photographs from right (lowest elevation point) to left (highest elevation point)

In the final section, we collected socio-demographic data using a combination of binary and qualitative polytomous variables. Respondents named, asking respondents to indicate their place of birth, current residence, and postal code. Responses were validated and processed using frequency tables, cross-tabulation, and chi-square tests to explore differences between the two groups. Data analysis in the second section carried out additional multiple response analyses. All tests were conducted in SPSS®.

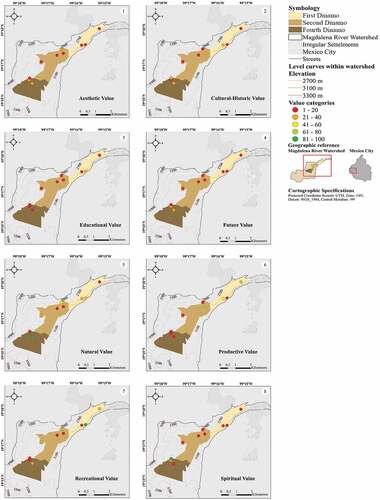

Visitors´ responses and their assigned SV to the photographs were analyzed with ArcGIS 10.1® to create maps that visualized the link between landscape features and the perceived SV. To do so, we counted the number of SV in each photograph and imported the SV scores into ArcGIS to generate eight maps of LDRP, representing each SV on a separate map. Since the responses ranged between 0 and 100, we classified them using the following scale: 0–20, 21–40, 41–60, 61–80, and 81–100. The higher the class category, the more visitors assigned SV to that place. Afterwards, we combined the SV with other landscape features to explore possible correlations. We used additional information, such as distance from the urban area, altitude, slope, and forest cover from the Geographic Atlas of Soil Conservation of Mexico City (Citation2012), as well as visibility of steep rocky walls (through on-site observation) to characterize the landscape features.

3. Results

3.1. Profile and park use of visitor groups

Chi-square test for independence shows that there are some differences and similarities in the socio-demographic characteristics between the visitors who engage in rock climbing in LDRP and those who visit the park for other recreational purposes. Approximately 79% of visitors within both groups were residents of Mexico City. The remaining visitors (21%) in the non-rock climbing group came exclusively from other Mexican states, whereas in the rock climbing group, 9% came from other states and 12% from foreign countries. There was a notable difference in marital status and children, but there are no statistical differences between rock climbers and non-rock climbers in terms of age, income, and education. In terms of employment, while those in both groups reported being in some form of gainful employment, there is a statistically significant difference between the visitor groups in respect to their professional group, for example, professors were exclusive to the rock climbing group, while job-seekers, tradespeople, and students could only be found among non-climbers. Interestingly, the gender ratio is nearly the same in groups, with 39% female non-rock climbers and 38% female rock climbers ().

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of visitors. NA represents number of rock climbers (A), and NB number of non-rock climbers (B). Within both groups, origin, gender, marital status, and having children were extrapolated to 100%, whereas age group, educational level, occupation, and income group present the most frequent answer. A Chi-square test of independence with an alpha level of .05 was used

Chi-square tests reveal that visitation patterns were statistically different between the two visitor groups in all items but in one (). There is no significant difference concerning group size, with both groups visiting the park mostly in parties of 3 to 5 people.

Table 3. Cross-tabulations of visitor characteristics. An alpha level of .05 was used for all statistical tests

All visitors, regardless of their group classification, have a great interest in the future of LDRP. Approximately, 60% believe that society should definitely assist in the decision-making of the park management, while the rest believe that there should at least be the possibility to participate in the decision-making process. While the LDRP is communal, publically-owned land, not everybody was aware of this. Many rock climbers (28%) responded that LDRP is communal land and not, as might be expected a natural protected area. Non-climbers tended to be more unaware of this (10%).

compares the opinion of the two visitor groups on all activities observed in LDRP during the observation period. Rock climbers are very much in favor of reforestation, rock climbing, and hiking. Recreationalists, on the other hand, agree with the need to promote reforestation, yet are more likely to visit the park for running or walking. While rock climbing and hiking are rather practiced in more remote places and in upper polygons, running and walking can be observed in the more open and publicly shared spaces in the lower parts of the park. Interestingly, rock climbers are very much against mechanical or motorized recreational activities such as riding squads or amusement rides that are frequent, particularly in the First Dinamo, as well as campfires.

3.2. Social values visitors ascribe to the Los Dinamos Recreational Park

The first of three tasks addressing SV perception in LDRP, which is a priority setting, shows no statistically significant difference between the two visitor groups (χ2 (df = 7) = 8.257, p = .310). The three most important SV ascribed for both groups are natural (22%), recreational (20%) and future (18%) values.

The results of the second task (in which respondents allocated money to a hypothetical project which enhances SV) showed no statistical difference between rock climbers and non-rock climbers (χ2 (df = 5) = 3.991, p = .551). Natural value (33%) is a priority for both visitor groups, whereas 19% of all money was allocated to educational value, 15% to recreational, and the rest was distributed among spiritual, cultural-historic, and aesthetic values.

While the LDRP as a whole has been ascribed predominantly with natural and future value, we found some differences in the perception of SV depending on the scale of the natural park. shows the results of the third SV perception task, where the respondents were asked to associate the SV to certain places of the park using photographs. The most significant results are: 1) only three out of ten photographs show statistically perceived differences between the two visitor groups (all of them are located in the Second Dinamo), 2), visitors perceive in every photograph multiple SV, although one is always prominent, 3) the productive value, which had not been important to the visitors in the general perception of the park in task I and II, was widely recognized in the photograph evaluation (, photograph 1, 3, 4 & 5).

Table 4. Social values ascribed to photographs were counted and calculated through a chi-square test with an alpha level of .05

3.3. Relationship between landscape characteristics and social values

Our results from the photograph-based analyses show that the SV are assigned according to the geographical location of LDRP sections (). A slight increase of SV is seen from the First to the Second Dinamo, but a stronger appreciation is evident in the Fourth Dinamo, which is furthest from the urban areas. Furthermore, we realized that the higher and further the polygons were from the urban area, based on the location points of the interviews, the more visitors assigned a natural value. More than half of visitors (52%) interviewed in the upper polygon (Forth Dinamo) selected the natural value as their highest priority. This was 37% for the Second Dinamo choice and 25% for the First Dinamo choice. We found similar results in the exercise where visitors allocated MEX 100 pesos among the three areas. The results showed that, in the Forth Dinamo polygon, respondents allocated 38% of the money for conservation. This was 5% higher than in the Second Dinamo polygon and 11% higher than in the First Dinamo.

Table 5. Relation between landscape characteristics and social values (Source: 1Google Earth Pro 2019, 2GDF (Citation2012), and 3self-generated data)

Displaying the diversified perception of SV of specific places in LDRP, results show that the Fourth Dinamo has been ascribed predominantly with natural and spiritual value (Fig. 4.5 & 4.8). The upper part of the park shows the interrelatedness of the spiritual values and the natural beauty of the landscape. The CES benefits that people gain from this interrelatedness is spirituality. Thereby, the interaction between religious practices and scenic, mystic places in the mountainous areas of the park have transformed the natural landscape into a cultural landscape filled with a complex cultural meaning. We also found that the upper polygons are the most interesting for the visitors in aesthetic terms. The two pictures with rocky landscapes, which have been assigned with aesthetic, recreational values, are located in the Second Dinamo (photograph 6) and the Fourth Dinamo (photograph 10). A third photograph assigned with aesthetic value is also located in the Fourth Dinamo (photograph 9), which is a medium-long shot showing dense forest and sightseeing points.

The Second Dinamo section has been ascribed mainly with natural, recreational, and productive values (Fig. 4.5, 4.7 & 4.6, respectively). This polygon has 83% of forest cover, and the recreational areas are all close to the main river. The productive value of this area is appreciated due to the traditional food stands and local trout farming areas. Interestingly, the traditional Mexican food stands (, photograph 4) are also related to cultural-historic value.

The First Dinamo is characterized by recreational, productive, and cultural-historic value (Fig. 4.7, 4.6 & 4.2, respectively). The latest is related to food consumption and corn cultivation. This polygon suffers from high soil erosion, encroachment by irregular settlements (), and loss of forest cover (). Likewise, the visitors’ attention is not on the natural aspects of the park but rather on the socially and culturally constructed aspects.

4. Discussion

4.1. Visitor groups need specialized and differentiated attention

We described the case of visitor groups in LDRP and showed the differences between rock climbers and non-rock climbers. Rock climbers spend more hours per visit in the park, are mostly accompanied by friends, and visit the park more than ten times a year. The primary purpose of their visits is sport recreation, specifically rock climbing, and therefore, they look out mainly for rock climbing settings. The differentiated use of places and performance of activities has implications for ecological impact, crowding, user experience, and user group conflicts (Whittaker et al. Citation2011). Knowledge about leisure activities, settings, and how they relate to the environment is important for adequate management of any natural park (Zhang et al. Citation2019). Whittaker et al. (Citation2011) suggest that effective management of parks needs to measure the spatial-temporal distribution of visitor use. Documenting different perceptions can potentially prevent social conflicts (Nahuelhual et al. Citation2017). Our results provide answers to these management questions: Firstly, shows the main infrastructure in LDRP and distribution of highly frequented places, which are the parking lots and food stands close to the only access road into the valley as well as the climbing spots, which are not yet recognized as such in Mexico, although climbing is an increasingly popular sport and tourist activity worldwide (Tahir and Caber Citation2016). Secondly, highlights the activities which visitor groups are in favor of or not, thus providing insights into possible recreational conflicts and also indicating a certain awareness of nature-friendly outdoor activities. Lastly, displays the different park use patterns between the visitor groups, where rock climbers frequent the park more often and stay longer on average.

4.2. Social values in the context of the Los Dinamos Recreational Park

We expected that SV perceptions would be statistically different between the two visitor groups due to the rock-climbing experience that shapes climbers´ perception (Kulczycki Citation2014). Perceptions were, however, rather similar across both groups. The natural value, which is the most assigned SV in LDRP, is the perceived interpretation of nature as a place to enjoy and connect held and intrinsic values. We assume that it is because of the unique riparian ecosystem, the dense forest cover, and the panoramic views over the mountain landscape. It is widely recognized that, due to growing urbanization, the demand for enjoyable environments is rising, especially because mountain-based landscapes are very attractive and appreciated by visitors (Schirpke et al. Citation2016). In the case of LDRP, the enjoyment of this natural aspect of the park is also closely connected to spiritual values in the upper part of the park. Our field observations showed that religious ceremonies at the peak of La Coconetla (, photograph 8), take place throughout the year. In the Second Dinamo, we witnessed such ceremonies being performed at a giant cross on a rock. The spiritual values of ecosystems are as important as other services for many local communities (Cooper et al. Citation2016; Ngulani and Shackleton Citation2019).

Almeida-Leñero and García Juárez (Citation2009) concluded that recreation and aesthetics are the most outstanding values in Los Dinamos. Our study underlines their findings by showing that visitors recognize the recreational value throughout the park. There are a great number of recreation opportunities (), which provides cultural ecosystem benefits, such as fitness and tranquility or escape from daily routines. Specific sports activities, such as rock climbing and mountain biking, have been assigned with a high recreational value (, photographs 2, 6 & 7). Aesthetic value, in contrast, was less appreciated. The photographs 6, 9, and 10 had the highest aesthetic values assigned. All three of them were long shots, two showing rock structures (Second and Fourth Dinamo), and the other photograph shows the dense forests in the Fourth Dinamo. However, this does not necessarily suggest a contradiction between our results and other studies (e.g. Almeida-Leñero and García Juárez Citation2009). They, along with Schirpke et al. (Citation2016), Bieling et al. (Citation2014), and Beza (Citation2010), somehow coincide that mountain landscapes are usually perceived as highly aesthetic. We thoroughly reviewed Almeida-Leñero’s work and could not find an explanation of the kind of instruments they used to arrive at this statement. Nevertheless, we feel that our results are solid and genuinely reflect the participants’ perceptions of their visit.

We observed economically productive activities in the park, such as trout farming and corn cultivation. The respondents assigned here a productive value to these two activities, as well as to the traditional food stands all over the park (). Interestingly, corn cultivation and traditional food stands (, photograph 3 & 4, respectively) were not just assigned with a productive value but were also related to cultural-historic values. Visitors also ascribed cultural-historic value to religious practices (photograph 8), and an open site with a view to the uprising rock walls and forest (photograph 10), respectively (). Almeida-Leñero et al. (Citation2007) observed cultural heritage, which can be linked to our findings of cultural-historic values.

Evaluating future value aims to understand if visitors are willing to preserve the landscape they are enjoying for future generations. Our results show a substantial interest in protecting the forest with its positive values and benefits for human wellbeing in this region. Most visitors frequent the LDRP several times a year to practice outdoor recreation and enjoy the natural surroundings. The positive and manifold SV they assign to the park should motivate community engagement and multifunctional land management (Plieninger et al. Citation2015). At this point, it is important to remember that LDRP is the largest and most diverse climbing area in Mexico City, and even though many visitors do not engage in rock-climbing activities, they would like the area to be preserved for future use. Literature calls these bequest values or those non-use values that people perceive as important for maintaining ecosystems for future generations (Oleson et al. Citation2015). Visitors ascribed high natural, future values because they may assume that this ecosystem is irreplaceable, despite the presence of other substitutes.

4.3. The connection between social values and landscape features

The three most significant landscape features we considered in this case study were the forest cover, the remoteness, and the visible, steep rocky walls. Landscape features are fundamental components of the interrelation between the visitors and their natural surroundings where intangible values – or, as we call them in this work – CES, express themselves (Bieling et al. Citation2014; Zhang et al. Citation2019). The specific expression of CES in LDRP shows higher natural and spiritual values the denser the forest cover is, as is the case with the Fourth Dinamo. This does not necessarily mean that there is a direct correlation with remoteness, (although in our case, it is remote) but that this landscape feature brings to light natural and recreational values. The remoteness in our case is related to the exposure of steep, rocky walls that provide solitude and favor recreational activities such as dispersed mountain biking and rock climbing, as in the case of the Second Dinamo. The narrow, steep geomorphological conditions of the MRW revealed also aesthetic values, particularly in the upper Second and Fourth Dinamo. These two upper polygons were more intensely valued () and there is a more diversified perception of SV (). Rall et al. (Citation2017) question whether polygon-oriented mapping can elicit immaterial SV; in the case of LDRP, our results indicate that it can.

Figure 4. Perception of social values in the three sub-polygons based on a photograph-based analysis. Each map shows one social value and location of ten photographs

Based on these results, we agree with Bieling and Plieninger (Citation2012) that an association between CES and landscape features exists, and it is important to continue exploring this relationship. We also agree that there is still not a clear methodological answer on how to do so. Bieling et al. (Citation2014) chose short interviews as their instrument of measurement. While we opted for questionnaires, our communality is an explicit inclusion of landscape features. GIS tools are useful for visualizing quantitative data in certain landscapes, as it has been shown in Nahuelhual et al. (Citation2017), Sherrouse et al. (Citation2011), Van Riper et al. (Citation2012), Zhang et al. (Citation2019) among others.

4.4. Limitations

A limitation of this cross-sectional and place-based study is its time-consuming procedure. However, the advantages outweigh the costs because selection bias during the survey was controlled by random sampling, as well as applying it on-site at different points, times of the day, and different weather conditions to reach a wider range of visitors. Face-to-face interviews allowed us to implement more complex tasks in exploring the SV. However, since interviewers experienced a certain degree of fatigue, only a limited number of surveys could be conducted during each visit. This issue, along with limited financial resources, undoubtedly influenced the decision to apply a 95% confidence level and a margin of error up to 10%. Continuous monitoring of public preferences, motivations, and perceptions using panel or longitudinal studies should be conducted to support landscape conservation.

A second limitation is that we focused exclusively on visitors of LDRP and ignored people who live outside the park but receive similar benefits (i.e. landscape scenery) or the local community who work in the park management. Including all interested parties who interact with LDRP should be the subject of collaborative or transdisciplinary future research to design better park management policies.

5. Conclusions

The two types of visitors to LDRP can be considered important stakeholder groups for the park’s management. Our results show that these groups need to be addressed separately because they use the park differently and conduct recreational activities in different places. Our results can function as a starting point to develop the first management plan for climbing areas in Mexico and to adopt a more holistic approach to natural landscape management. In addition, analyzing or describing CES due to SV needs a precise description of their method and instruments. Our study supports the use of geo-referenced photographs as an effective method for mapping SV. Therefore, understanding which landscape features can be associated with which values are positively perceived by the visitors.

We conclude that there are no statistical differences in the perception of SV between visitor groups, as they agree that natural, recreational and productive values are the most important ones in LDRP. We also observed that CES manifests itself differently in our case due to geomorphology, forest cover, and proximity to the urban area, thus revealing a positive relationship between SV perception and forest cover, remoteness, and rock formations. The discussed perception of visitors on a local level is a building block in constructing an entire picture of the natural landscape of LDRP. Our results can be used to promote nature-friendly recreational activities and enhance restoration and conservation projects in the areas of the park, where the impact through infrastructure of intensive recreational activities (i.e. riding squads or horses) is of growing concern.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (342.7 KB)Acknowledgments

The first author had a research fellowship from CONACYT. We thank all respondents for their cooperation, as well as Ángel Teran, Aurelio Bernal, and Isaac Pineda for their support in the Geomatics Lab (CIIEMAD-IPN). We also thank Max Huber for his help with the graphics. We express our appreciation to the editor-in-chief and the four anonymous reviewers who evaluated this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almeida-Leñero L, García Juárez S. 2009. Hacia una propuesta de educación ambiental en la comunidad de la Magdalena Atlitic, Distrito Federal. In: Castillo A, González Gaudiano E, editors. Educación ambiental y manejo de ecosistemas en México. Mexico: INE, Semarnat, and UNAM; p. 203–223.

- Almeida-Leñero L, Nava M, Ramos A, Espinosa M, De Ordoñez MJ, Jujnovsky J. 2007. Servicios ecosistémicos en la cuenca del río Magdalena, Distrito Federal, México. Gaceta Ecol. 84–85:53–64.

- Beza BB. 2010. The aesthetic value of a mountain landscape: a study of the Mt. Everest Trek. Landsc Urban Plan. 97(4):306–317. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.07.003.

- Bieling C, Plieninger T. 2012. Recording manifestations of cultural ecosystem services in the landscape. Landscape Res. 38(5):649–667. doi:10.1080/01426397.2012.691469.

- Bieling C, Plieninger T, Pirker H, Vogl CR. 2014. Linkages between landscapes and human well-being: an empirical exploration with short interviews. Ecol Econ. 105:19–30. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.05.013.

- Brown G, Brabyn L. 2012. An analysis of the relationships between multiple values and physical landscapes at a regional scale using public participation GIS and landscape character classification. Landsc Urban Plan. 107(3):317–331. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.06.007.

- Brown G, Reed P. 2000. Validation of a forest values typology for use in national forest planning. For Sci. 46(2):240–247.

- Cheng X, Van Damme S, Li L, Uyttenhove P. 2019. Evaluation of cultural ecosystem services: a review of methods. Ecosyst Ser. 37:100925. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100925.

- Christie M, Fazey I, Cooper R, Hyde T, Kenter JO. 2012. An evaluation of monetary and non-monetary techniques for assessing the importance of biodiversity and ecosystem services to people in countries with developing economies. Ecol Econ. 83:67–78. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.012.

- Cooper N, Brady E, Steen H, Bryce R. 2016. Aesthetic and spiritual values of ecosystems: recognising the ontological and axiological plurality of cultural ecosystem ‘services’. Ecosyst Ser. 21:218–229. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.07.014.

- Costanza R, de Groot R, Braat L, Kubiszewski I, Fioramonti L, Sutton P, Farber S, Grasso M. 2017. Twenty years of ecosystem services: how far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst Ser. 28:1–16. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.09.008.

- Dickinson D, Hobbs R. 2017. Cultural ecosystems services: characteristics, challenges and lessons for urban space research. Ecosyst Ser. 25:179–194. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.04.014.

- Felsch P. 2009. Mountains of sublimity, mountains of fatigue: towards a history of speechlessness in the alps. Sci Context. 22(3):341–364. doi:10.1017/S0269889709990044.

- Fischer A, Eastwood A. 2016. Coproduction of ecosystem services as human–nature interactions—An analytical framework. Land Use Policy. 52:41–50. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.004.

- Galeana Pizaña JM, Corona Romero N, Ordóñez Díaz JA. 2009. Análisis dimensional de la cobertura vegetal – uso de suelo en la cuenca del Río Magdalena. Cienc for Méx. 34(105):135–156.

- GDF, Gobierno del Distrito Federal. 2012. Atlas geográfico del suelo de conservación del Distrito Federal. México (D.F): Secretaria del Medio Ambiente, Procuraduría Ambiental y del Ordenamiento Territorial del Distrito Federal.

- Hashimoto S, Nakamura S, Saito O, Kohsaka R, Kamiyama C, Tomiyoshi M, Kishioka T. 2015. Mapping and characterizing ecosystem services of social–ecological production landscapes: case study of Noto, Japan. Sustain Sci. 10(2):257–273. doi:10.1007/s11625-014-0285-1.

- Ives CD, Kendal D. 2014. The role of social values in the management of ecological systems. J Environ Manage. 144:67–72. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.05.013.

- Jujnovsky J, Almeida-Leñero L, Bojorge-García M, Monges YL, Cantoral-Uriza E, Mazari-Hiriart M. 2010. Hydrologic ecosystem services: water quality and quantity in the Magdalena River, Mexico City. Hidrobiológica. 20(2):113–126.

- Jujnovsky J, Galván L, Mazari-Hiriart M. 2013. Zonas Protectoras Forestales: el caso de los bosques de la Cañada de Contreras, Distrito Federal. Invest Ambiental. 5(2):65–75.

- Kenter JO, Hyde T, Christie M, Fazey I. 2011. The importance of deliberation in valuing ecosystem services in developing countries—evidence from the Solomon Islands. Global Environ Change. 21(2):505–521. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.001.

- Kenter JO, O’Brien L, Hockley N, Ravenscroft N, Frazey I, Irvine KN, … Williams S. 2015. What are shared and social values of ecosystems? Ecol Econ. 111:86–99. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.01.006.

- Kulczycki C. 2014. Place meanings and rock climbing in outdoor settings. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 7–8(7):8–15. doi:10.1016/j.jort.2014.09.005.

- Langemeyer J, Baró F, Roebeling P, Gómez-Baggethun E. 2015. Contrasting values of cultural ecosystem services in urban areas: the case of park Montjuïc in Barcelona. Ecosyst Ser. 12:178–186. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.11.016.

- Martínez-Cruz AL, Sainz-Santamaría J. 2017. El valor de dos espacios recreativos periurbanos en la Ciudad de México. trimestre econ. 84(336):805–846. doi:10.20430/ete.v84i336.607.

- MEA. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. millennium ecosystem assessment. Washington (DC): World Resources Institute. Island Press.

- Milcu AI, Hanspach J, Abson D, Fischer J. 2013. Cultural ecosystem services: a literature review and prospects for future research. Ecol Soc. 18(3). doi:10.5751/ES-05790-180344.

- Montes RT, Navarro I, Domínguez R, Jiménez B. 2013. Modificación de la capacidad de autodepuración del río Magdalena ante del cambio climático. Tecnol Cienc Agua. 4(5):71–83.

- Nahuelhual L, Vergara X, Kusch A, Campos G, Droguett D. 2017. Mapping ecosystem services for marine spatial planning: recreation opportunities in Sub-Antarctic Chile. Mar Policy. 81:211–218. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.038.

- Ngulani T, Shackleton CM. 2019. Use of public urban green spaces for spiritual services in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Urban For Urban Greening. 38:97–104. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2018.11.009.

- Nydal AK. 2018. A difficult line: the aesthetics of mountain climbing 1871-present. In: Kakalis C, Goetsch E, editor. Mountains, mobilities and movement. London: Palgrave Macmillan; p. 155–170. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-58635-3_8.

- Oleson KL, Barnes M, Brander LM, Oliver TA, van Beek I, Zafindrasilivonona B, Van Beukering P. 2015. Cultural bequest values for ecosystem service flows among indigenous fishers: a discrete choice experiment validated with mixed methods. Ecol Econ. 114:104–116. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.02.028.

- Pérez-Campuzano E, Avila-Foucat VS, Perevochtchikova M. 2016. Environmental policies in the peri-urban area of Mexico City: the perceived effects of three environmental programs. Cities. 50:129–136. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.08.013.

- Perez-Verdin G, Sanjurjo-Rivera E, Galicia L, Hernandez-Diaz JC, Hernandez-Trejo V, Marquez-Linares MA. 2016. Economic valuation of ecosystem services in Mexico: current status and trends. Ecosyst Ser. 21:6–19. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.07.003.

- Plieninger T, Bieling C, Fagerholm N, Byg A, Hartel T, Hurley P, … Huntsinger L. 2015. The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 14:28–33. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.02.006.

- Rall E, Bieling C, Zytynska S, Haase D. 2017. Exploring city-wide patterns of cultural ecosystem service perceptions and use. Ecol Indic. 77(2017):80–95. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.02.001.

- Raymond C, Brown G. 2006. A method for assessing protected area allocations using a typology of landscape values. J Environ Plann Manage. 49(6):797–812. doi:10.1080/09640560600945331.

- Rea LM, Parker RA. 2014. Designing and conducting survey research. A comprehensive guide. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ridding LE, Redhead JW, Oliver TH, Schmucki R, McGinlay J, Graves AR, … Bullock JM. 2018. The importance of landscape characteristics for the delivery of cultural ecosystem services. J Environ Manage. 206:1145–1154. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.11.066.

- Rossiter P. 2007. Rock climbing: on humans, nature, and other nonhumans. Space Cult. 10(2):292–305. doi:10.1177/1206331206298546.

- Scarpa R, Thiene M. 2005. Destination choice models for rock climbing in the Northeastern Alps: a latent-class approach based on intensity of preferences. Land Econ. 81(3):426–444. doi:10.3368/le.81.3.426.

- Schirpke U, Timmermann F, Tappeiner U, Tasser E. 2016. Cultural ecosystem services of mountain regions: modelling the aesthetic value. Ecol Indic. 69:78–90. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.04.001.

- Schmidt K, Walz A, Martín-López B, Sachse R. 2017. Testing socio-cultural valuation methods of ecosystem services to explain land use preferences. Ecosyst Ser. 26:270–288. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.07.001.

- Scholte SK, van Teeffelen A, Verburg P. 2015. Integrating socio-cultural perspectives into ecosystem service valuation: a review of concepts and methods. Ecol Econ. 114:67–78. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.03.007.

- Sherren K, Fischer J, Price R. 2010. Using photography to elicit grazier values and management practices relating to tree survival and recruitment. Land Use Policy. 27(4):1056–1067. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.02.002.

- Sherrouse BC, Clement JM, Semmens DJ. 2011. A GIS application for assessing, mapping, and quantifying the social values of ecosystem services. Appl Geogr. 31(2):748–760. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.08.002.

- Sherrouse BC, Semmens DJ, Ancona ZH, Brunner NM. 2017. Analyzing land-use change scenarios for trade-offs among cultural ecosystem services in the Southern Rocky Mountains. Ecosyst Ser. 26:431–444. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.02.003.

- Tahir A, Caber M. 2016. Destination attribute effects on rock climbing tourist satisfaction: an asymmetric impact-performance analysis. Tour Geogr. 18(3):280–296. doi:10.1080/14616688.2016.1172663.

- Tew ER, Simmons BI, Sutherland WJ. 2019. Quantifying cultural ecosystem services: disentangling the effects of management from landscape features. People Nat. 1(1):70–86. doi:10.1002/pan3.14.

- Van Riper CJ, Kyle GT, Sutton SG, Barnes M, Sherrouse BC. 2012. Mapping outdoor recreationists´ perceived social values for ecosystem services at Hinchinbrook Island Park, Australia. Appl Geogr. 35(1–2):164–173. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.008.

- Whittaker D, Shelby B, Manning R, Cole D, Haas G. 2011. Capacity reconsidered: finding consensus and clarifying differences. J Park Recreat Admi. 29(1):1–20.

- Zhang W, Yu Y, Wu X, Pereira P, Lucas Borja ME. 2019. Integrating preferences and social values for ecosystem services in local ecological management: a framework applied in Xiaojiang Basin Yunnan province, China. Land Use Policy. 91:104339. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104339.

- Zhang Y, McDowell ML. 2020. Climbing Dumbarton Rock: an exploration of climbers’ experiences on sport and heritage from the perspective of existential authenticity. Leisure/Loisir. 44(4):547–567. doi:10.1080/14927713.2020.1815565.