ABSTRACT

The habitats of Nepal’s endangered red pandas provide ecosystem goods and services to surrounding human communities. Here, to help reduce pressure on the panda, we quantified the current use of the most important ecosystem goods and services obtained in and around a protected area in western Nepal, trends over the last 20 years, and factors driving those trends. Our results show that more ecosystem goods and services were sourced by communities living outside the protected area than inside except for fodder and bedding for animals, recreational activities and ecotourism. Incomes inside the protected area were higher than outside. Of the seven main services investigated (i) use of medicinal plants had increased but their availability had declined; (ii) bamboo use remained steady but less was available; (iii) there were no perceived trends in firewood use or availability; (iv) there was less transhumant pastoralism to upland pastures but pasture availability had declined; (v) less fodder and bedding for animals was collected inside the park than outside, but the availability was unchanged; (vi) use of sacred religious sites had declined inside but not outside the park; (vii) the reverse was true for recreational tourism. Direct drivers of change in ecosystem service provision included changes in weather patterns and fluctuations in the market for goods; indirect drivers were institutional governance and regulation, population growth, literacy, poverty, and infrastructure development. Policies that ensure sustainable use of ecosystem goods and services from panda habitats could improve local livelihoods, reduce natural resource degradation and help conserve the panda.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

Nearly 13% of the human population lives in montane environments (Romeo et al. Citation2015) and many mountain people rely directly or indirectly on mountain resources (Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. Citation2011; Maselli Citation2012). Mountain ecosystems also support a quarter of global terrestrial biological diversity and encompass almost half of the world’s biodiversity hotspots (Sharma et al. Citation2019). However, while mountain ecosystems face increasing levels of environmental degradation through human interference (Price Citation2015) and climate change (Palomo Citation2017; Peters et al. Citation2019), continued provision of the ecosystem goods and services on which many mountain peoples and biodiversity rely are often given low priority in conservation decision-making processes and policies (Acharya et al. Citation2019) because of the high costs of their conservation (de Groot et al. Citation2010; Rasul et al. Citation2011). This study aims to understand the processes influencing the provision of ecosystem goods and services from western Nepal at the heart of the Himalayan biodiversity hotspot, which is among the 20 most important hotspots in the world (MoFSC Citation2014a). The results and policy recommendations derived from the study are likely to be relevant to other mountain ecosystems globally.

The mountains cover about three-quarters of Nepal (Thapa Citation1996) and many of the species occurring in these mountains are threatened (Måren et al. Citation2015). Among them is the red panda (Ailurus fulgens), a threatened and declining species with an elevational range of 2500 and 4800 m asl confined to 24,000 km2 across 24 districts in Nepal (Glatston et al. Citation2015; Bista et al. Citation2016). The species, which relies heavily on bamboo as a food source (Sharma et al. Citation2014a; Panthi et al. Citation2015), also occurs in India, China, Myanmar and Bhutan. The red panda’s habitat in Nepal is also integral to the livelihoods of the many poor and socio-economically marginalised local communities whose inhabitants rely heavily on the forests for numerous ecosystem goods and services (Chaudhary et al. Citation2009), particularly bamboo, medicinal plants, firewood, fodder and bedding for animals, and, recently, tourism (Bhatta et al. Citation2020). Over-use or misuse of the ecosystem goods and services can lead to loss of both red panda populations and of the goods and services needed by the region’s human inhabitants.

To date, most research on red pandas has focused on the needs of the species, with human use of the habitat largely viewed as a threat to be ameliorated (DNPWC & DFSC Citation2018; Glatston and Gebauer Citation2022). While a community-based approach has been adopted in Nepal since 2017, it has focused on research, monitoring and antipoaching; education and outreach; habitat management; and sustainable livelihood programmes (Sherpa et al. Citation2022). A complementary approach to conserving the red panda could be through understanding the ways mountain forest habitats support the well-being and economies of the mountain communities. A key element of this approach is quantifying the ecosystem goods derived from the panda’s habitat, and the extent to which utilization of ecosystem services impinge on red panda survival. Such knowledge is highly relevant to understanding the nature, scale and drivers of the threats to red pandas and to the policy that might be developed for threat alleviation. However, most studies of ecosystem service provision in Nepal are from the mid-hills and lowlands of the country (Lamsal et al. Citation2018).

The aims of this study are therefore to quantify the ecosystem goods and services obtained from the habitats of the red panda, understand how the use and availability of these goods and services is changing and explore the drivers of those changes. Strengthened knowledge of the use of ecosystem goods and services in the panda’s habitat will help the development of appropriate policy for both the conservation of mountain ecosystems and the sustainability of the livelihoods of the people live there. To place the work within the context of existing conservation practice in Nepal, the study was undertaken in two areas with contrasting tenure, one designated as National Park, the other as community forest and leasehold forest. In both tenures, local communities continue to practice traditional livelihoods but under differing levels of legal constraint.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

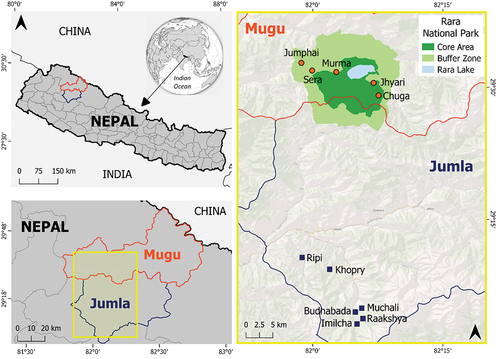

The study was carried out in all five locations in and around the Rara National Park (RNP), Mugu District. A further six locations outside the RNP were purposively selected in the adjacent Jumla District because they were in similar terrain to those within the park and also close to red panda habitat. All study locations were in Karnali province – the largest (24,453 km2), most geographically isolated and least developed of the seven federal provinces of Nepal (). The study area is mountainous (1,200–6,600 m asl.; DDC Citation2013, Citation2016), cool (−0.1°C to 13.0°C) relatively dry (average annual rainfall 830 mm), sparsely populated (164,000 people), with little agricultural development (agriculture 9%; bare 31%, forests 28%, shrub/grassland 23%; Shrestha et al. Citation2019). Five of the villages were in the Buffer Zone adjacent to RNP surrounded by land managed by the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and local buffer zone management committees. For these communities, RNP could no longer be a place of residence or a site to practice agriculture and legally could ostensibly only be used for harvesting resources for private use under permit (GoN Citation1979), although the rules are not necessarily enforced closely (Bhattarai et al. Citation2017). The other six villages, 30–45 km to the south, were adjacent to community forest and leasehold forest managed by the district office of the Department of Forests and Soil Conservation which was also habitat for red pandas (Bhatta et al. Citation2014). Villagers had the right under a permit to graze stock and harvest resources commercially from this land (Nepal Citation2019). In both areas, livelihoods have traditionally been based on agriculture, animal farming including transhumance to high altitude pastures, the collection of medicinal herbs and other non-timber forest products, handicrafts, and seasonal outmigration for employment (Bhatta et al. Citation2020). More recently, communities in RNP have benefited from tourism. Core to these livelihoods have been the ecosystem goods and services obtained from mountain forests, with which villagers have retained strong cultural ties. However, some of these livelihood activities, such as the collection of bamboo as fodder for sheep and mountain goats and the harvesting of medicinal plants, can threaten red pandas, either directly (hunting, predation by sheep guard dogs) or indirectly (over-harvesting of bamboo, the main foodplant; Bhatta et al. Citation2020; Bista et al. Citation2022).

2.2. Research design

The paper is predicated on the theoretical principle that sustainable development must both alleviate poverty and maintain environmental quality (Shi et al. Citation2019). This can only be achieved where the utilization of ecosystem goods and services is commensurate with their supply (Balvanera et al. Citation2022). To understand the link between supply and demand for the ecosystem services, and benefits gained, we used a mixed-methods research approach (Denscombe Citation2008), a social research approach with components of both the qualitative and quantitative research (Tashakkori et al. Citation1998). The social research tools used included Focus Group Discussions (FGDs; Morgan and Spanish Citation1984; Schaafsma et al. Citation2017), Key Informant Interviews (KIIs; Holloway and Galvin Citation2016), semi-structured questionnaire surveys (Mukherjee Citation1997; Longhurst Citation2003) and participant observation (Kawulich Citation2005; Dewalt and Dewalt Citation2011). The results from these techniques were compared and combined with each providing some unique information while also corroborating or contrasting with information obtained with other approaches. The aim was to quantify the income respondents had been receiving from ecosystem services identified as being the most important to the communities surveyed (bamboo, medicinal plants, firewood, fodder and bedding for animals; Bhatta et al. Citation2020), trends in their use by respondents and in their availability and the drivers of change in resource flows. We provided research participants with a copy of a Plain Language Project Information sheet and also explained in the local language the research aims, methodology, the background of the investigators and the research ethics principles being followed. The necessary information was then recorded digitally, by taking notes, and in survey questionnaires. All the research respondents signed an informed consent form before the research proceeded further. Human research ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Charles Darwin University (H17030). Study permits were obtained from the relevant line agencies in Nepal.

2.3. Research methods

2.3.1. Data collection and sampling strategy

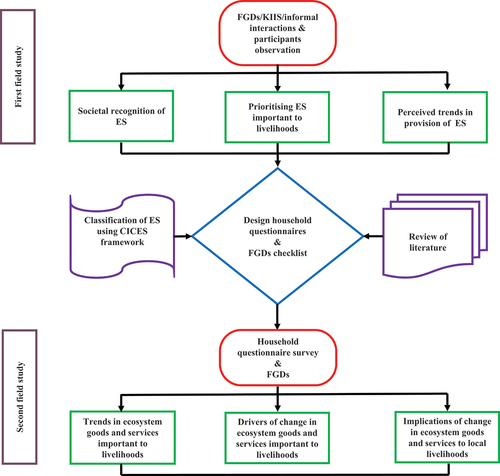

We started by holding informal discussions with the traditional village chiefs, local leaders and village elders who then nominated people they thought would participate constructively and provide reliable and relevant information. All information was collected in Khas bhasa, the local language with the help of locally hired research assistants. These were university students, the majority of whom came from the study region and were familiar with the local language, culture, conservation practices and livelihood conditions. Qualitative data were collected in two phases (). From November 2017 to January 2018, we conducted a total of six FGDs (56 participants: 68% M, 32% F), three outside and three inside the Protected Area (PA), and 15 KIIs (67% M and 33% F). A second set of six FGDs were conducted from August to October 2019, three inside and three outside the PA (56 participants, 64% M, 36% F; Tables S1 and S2). Participants in FGDs and KIIs were chosen based on their in-depth understanding and experience in the local landscape with respondents selected on the basis of their position within the village governance structure and their traditional and professional experience (Table S1).

Figure 2. The methodological approach used in this study for assessment on changes in livelihoods resources derived from red panda habitats. Acronyms: FGDs – Focus Group Discussions, KIIs – Key Informant Interviews, ES – Ecosystem Services, CICES – Common International Classification of Ecosystem Service.

Quantitative data were collected from August to October 2019 through a semi-structured household questionnaire (Table S3). The household survey questionnaires aimed to build on the information collected from the first field trip and improve understanding of the use and availability of ecosystem goods and services obtained from red panda habitat. They were piloted with 12 households before finalization. Participants in the survey were purposively sampled, a non-random sampling technique by which respondents are selected on the basis of experience and knowledge of the subject (Tongco Citation2007). Purposive sampling was needed to ensure that those with relevant long-term experience of changes in ecosystem availability and use were sampled who could then provide detailed descriptions of trends over time, which is the primary aim of sampling purposively (Etikan et al. Citation2016). The survey involved a single-visit household questionnaire. In total, 243 out of 334 households (145 out of 220 within the PA (66%) and 98 out of 114 outside the PA (86%) in 11 locations were sampled for the survey (Table S2). We interviewed the oldest members of the family in the household survey if available but included other senior household members when necessary.

2.3.2. Design of focus group discussions

We asked participants in FGDs to discuss the changes in ecosystem service provision from red panda habitats in the past two decades. FGDs during the first field visit discussed trends in all ecosystem services (described in Bhatta et al. Citation2020). During the second field visit, the discussion focused on the services that the villagers considered important to their livelihoods and considered both trends and drivers of change in use and availability. The participants also discussed the implications of such changes to local livelihoods. The information gathered from FGDs was then triangulated with information from the KIIs and from field observations.

2.3.3. Survey design

The questionnaire (Table S3) consisted of two parts. First, we asked about the quantity (in local units) of ecosystem goods harvested annually from red panda habitats. We then collected information on the local market unit price (Table S4) of the six focal provisioning services (bamboo, medicinal plants, firewood, fodder, bedding for animals and tourism; from Bhatta et al. Citation2020) to enable the calculation of the annual monetary return from these services. We also asked the household respondents for the annual income they had been generating from transhumance and ecotourism activities in and around red panda habitats. Income from transhumance was derived from selling goats, sheep, their wool and associated products. Ecotourism income was derived from tourist guiding, boating, horse riding and provision of accommodation.

In the second part of the questionnaire, we collected the opinions of the household survey informants on the importance of these ecosystem goods and services to the daily requirements of the community in and around the red panda habitats and how their use (demand) and availability (supply) has changed in the last two decades. Opinions on changes were assessed using scales with three categories: changes in use (more/increase, no change/stable, less/decrease); changes in availability (more abundant/increase, no change/stable, less abundant/decrease).

2.3.4. Data analysis

We used information on income to calculate the mean, standard deviation, the minimum and maximum economic value of ecosystem goods and services from mountain habitats of red panda both inside and outside the PA. We tested for differences between the inside and outside the PA using the Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test (Kruskal and Wallis Citation1952), a non-parametric statistical analysis test.

To assess perceived trends in ecosystem service use and availability, we calculated the percentage of responses in each response category (‘less use’, ‘no change’, ‘more use’). Responses on trends in the last 20 years were only included for respondents of age 35 or above so they would have been at least 15 years old when the trend period began. As with income, we tested differences between inside and outside the PA using the Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test based on the numbers in each category (Kruskal and Wallis Citation1952).

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Of the 243 respondents interviewed to determine which ecosystem goods and services were perceived as important to the community (Section 3.2) and the monetary returns from ecosystem goods and services (section 3.3), the average age was 42 years with a male bias (62%; Table S2). Of these, 176 were included in analyses of perceived trends in the use and availability of ecosystem goods and services (97 inside, 79 outside the PA; section 3.4) because they were older than 35 so had personal experience of change in their lifetime. This group had an average age of 47 of whom 68% were men and 65% had not completed any formal education (Table S2).

3.2. Utilisation of ecosystem goods and services

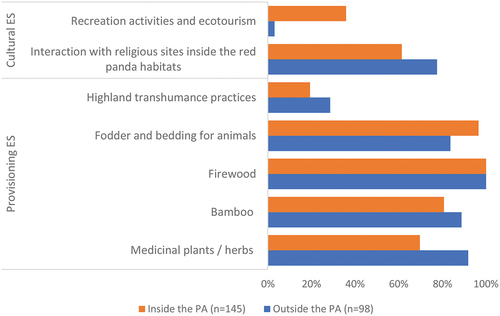

All households, both inside and outside the PA, relied on wild plants from red panda habitats for materials or energy () —particularly firewood (100% of households), fodder and bedding for animals (91%), bamboo (84%), and medicinal plants (79%). About 23% of households used upland pastures for seasonal transhumant grazing and around 68% of households said that they perform religious practices in and around these habitats. Almost 36% of households inside the PA were involved in tourism and recreational activities but only 3% of households were active in such activities outside the PA.

3.3. Monetary returns from ecosystem goods and services

Our survey indicated that households inside the PA generated greater annual economic income from ecosystem services (US $2718/household/year) than those living outside the PA (US $2538/household/year). Households inside the PA derived more income from recreation, seasonal grazing, and fodder and bedding for animals, but less for medicinal plants and firewood (see ).

Table 1. Monetary value of key ecosystem goods and services obtained from red panda habitats inside and outside a PA in western Nepal.

3.4. Perceived trends in use and availability

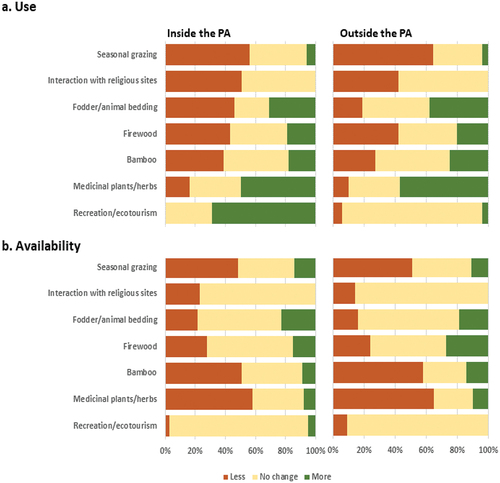

Household survey respondents both inside and outside the PA believed there had been strong declines in the use of upland pastures for grazing and in the interaction with religious sites, many of which were visited when travelling to and from the pastures (). Opinions were more divided about trends in the collection of bamboo, firewood and of fodder and bedding for animals, suggesting little change in use. The collection of medicinal plants had increased greatly. Only for recreational opportunities was there a significant difference between inside and outside the PA, with use greatly increased within the PA ().

Figure 4. Trends in the utilization of ecosystem goods and services of significance to livelihoods in red panda habitats in western Nepal from 2000–2020 and their availability to those utilizing them.

Table 2. Perceived changes in the use and availability of ecosystem goods and services from red panda habitats inside and outside a PA in western Nepal.

Survey participants considered that the supply of bamboo, medicinal plants and seasonal grazing had declined greatly, though views on grazing were slightly more mixed. Most thought that religious shrines and other sites had continued to be paid appropriate respect, though some thought religious observance at such sites had declined. There was a range of views on the availability of fodder/animal bedding and firewood, with no clear view on whether there had been change, and the availability of recreational/ecotourism opportunities was considered by virtually everyone (95%) to have remained constant. No differences between inside and outside the PA were significant except for recreational and ecotourism activities inside the PA (Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, P < 0.05; ).

3.5. Drivers of change

Qualitative information on drivers of change in availability and use of the main ecosystem services used directly by communities was obtained from the 12 FGDs, with the same drivers of change emerging from discussions both inside and outside the RNP. Drivers were strongly connected, both among those influencing availability and those affecting use, as well as between them. It was not possible to attribute quantitatively the extent of influence. Nevertheless, the construction of new roads linking what was once an extremely remote region with settlements in the lowlands to new markets for both goods and people seemed to underpin many of the changes people said they had observed. One FGD participant described how:

We used to take our cattle, sheep and goats to the lowlands during winter, selling and exchanging goods including wool and its products, goat and sheep for meat, traditional medicines, and obtaining groceries. We would then return to our upland pastures in summer. The cattle were our means of transport. New roads made access to the market, transportation, and other daily requisites easy, altering the transhumant lifestyle or leading to its abandonment.

The other reason that many FGD participants mentioned for the decline or abandonment of transhumance was a lack of labor because many younger people preferred cash crop farming, mainly tree fruits such as apples, as well as goat farming in the village, education, ecotourism, and national and foreign employment opportunities. Only one FGD participant outside the PA thought young people in their village were interested in continuing transhumance, but with modifications such as using modern techniques to improve the breed of animals.

In any case, notwithstanding improved access, transhumance down to the lowlands was becoming more difficult because of government policy that allowed control of government forests to revert to local communities:

In the past, we used to take our cattle to the lowlands but now we are not allowed to graze there since the lowland communities have taken back control of their communal forests. We are compelled to keep our cattle near our villages, which creates pressure on local resources and the upland pastures.

Additional pressure was being exerted on upland pastures because, in the absence of traditional governance, they had become overused common pool resources with people coming from further away in the district to use the same pastures, more than making up for reduced grazing by the villagers themselves.

Increased accessibility had several other flow-on effects. For example, improved accessibility of the region has also contributed to an increase in demand for medicinal plants in and around the red panda habitats, sometimes for species of which there is no local knowledge about sustainable harvest. One respondent described how:

For the last 10 years, middlemen, vendors and dealers have been coming to our village and demanded large volumes of medicinal plants (sometimes we get money in advance as well). The demand for individual medicinal plants fluctuates from year to year and the price accordingly. Sometimes they show us photographs of plants we have not collected for commercial purposes before and ask us to collect that particular species.

Demand for medicinal plants people had not collected traditionally had meant some plants had been over-collected simply through inexperience. Also, as with the upland pastures, medicinal plant harvesting was affected by poor governance and a lack of monitoring (Bhatta et al. Citation2022a). A respondent from outside the PA described how:

People from other villages and even from adjoining districts illegally collect medicinal plants in large volumes from our areas. Medicinal herb traders seek permission from local authorities but collect beyond the permitted amount. There are inefficient and weak law enforcement mechanisms in and around the red panda habitats.

Another change linked to accessibility was the decline in bamboo availability. While some people considered that the use of bamboo had declined as transhumance had become less prevalent, some people said that they had been harvesting more bamboo than previously. The trend data on availability suggests the impressions of the latter group may have been a closer reflection of the situation on the ground with participants in the FGDs suggesting that extra bamboo was being cut for fodder for animals kept in stalls in the village that would otherwise have been on upland pastures. Another factor that may have reduced bamboo availability despite little change in harvesting rate may have been a flowering event – such events occur at decadal intervals and result in death of all adult plants and their gradual replacement with a new generation (Tewari Citation1993), with impacts on both pandas and people (Bista et al. Citation2017).

Pressures to abandon transhumance were highest within the RNP, where not only was grazing somewhat restricted by regulations but incomes from tourism had increased with the new road, making transhumance even less able to compete for time and labour. A consequence, again felt most keenly within the RNP, was less religious interaction with nature, although they still managed to perform major religious rituals or ceremonies. As one FGD participant noted:

We have hundreds of religious/holy sites on the transhumance routes where our rituals show honor and reverence for our gods and goddesses for the betterment of herds, a safe trip, and continuing security and health of families back home. The reduction transhumance has limited our interaction with most of those sites.

Only some of the drivers were independent of changed accessibility. For example, changes in weather patterns, particularly an increased frequency of exceptionally high snowfalls, flooding rains and drought, were also seen as driving change in both the availability and use of ecosystem services. Such changes may also explain perceived increases in the frequency of forest fires, which affect the availability of many forest resources such as bamboo, fodder, firewood and medicinal plants, and in animal disease, which has had implications for transhumance.

4. Discussion

An earlier study (Bhatta et al. Citation2020) identified, categorized and prioritized the ecosystem goods and services currently derived from the red panda habitats by local communities in and near RNP in western Nepal. While many people away from the mountains also depend on the goods and services produced by mountain ecosystems (Gentle and Maraseni Citation2012), for all users the ecosystem is a common-pool resource. Because resources are predictably found in dense and discrete patches, sustainable use of these resources does not arise naturally but depends on effective local governance (Moritz et al. Citation2018). Degradation of such governance increases the risk of unsustainable use and resource depletion (Ostrom Citation2007) and it is the local users, who gain directly from the services provided, who also suffer most immediately when they are depleted and have the greatest direct influence on their provision. In this study on the significance of the contribution of these goods and services to local livelihoods and trends in their use and availability over the past two decades, we show that human use of the red panda habitats of western Nepal is changing rapidly with implications for both the panda and the people who rely on the ecosystem goods and services provided by its habitat. Our study complements the increasing knowledge of the ecological requirements of the panda itself (DNPWC & DFSC Citation2018; DNPWC Citation2012) and will allow important refinements to the interventions, community-based conservation initiatives and other species-based monitoring and conservation programs and approaches currently practiced (Bista et al. Citation2016; Bista Citation2018).

4.1. Provision of ecosystem goods and services from red panda habitats

While there appears to have been little traditional connection between red pandas and people in Nepal (Glatston and Gebauer Citation2022), the wellbeing of both red pandas and the people amongst whom it lives have traditionally been inseparable because of reliance on forest ecosystem services. Firewood, medicinal plants, bamboo, fodder and bedding for domestic animals have long been obtained from the red panda habitat, and the habitat has sustained flocks of livestock on their annual migrations to and from upland pastures. The habitat is also integral to religious practice and provided recreational opportunities for tourists (Bhatta et al. Citation2020). Of these services, we found that firewood, fodder and bedding for animals created the greatest income for communities both inside and outside the PA. Such reliance of rural communities on the natural environment is common in developing nations (Vira and Kontoleon Citation2012) with 80% of the population in Nepal obtaining food, fiber, freshwater and medicine from the forest (DNPWC & BCN Citation2012) and about 64% of households using firewood as the main source of energy for cooking (CBS Citation2012). For cash income, however, communities outside the PA relied primarily on medicinal plants and those inside the PA on tourism. Both are important to Nepal more generally: in 2014 Nepal traded more than ten thousand tons of medicinal and aromatic plants with a total value estimated at US$ 60 million to over 50 countries (Ghimire et al. Citation2015); in 2018, the country created more than US$2 billion in tourism revenue which supported over one million jobs (WTTC Citation2019). And, just as in the country as a whole, tourism was providing more income at the time of the study than plants, and, was gradually replacing conventional sources of income (Fleming and Fleming Citation2009; He et al. Citation2018).

FGD participants explained that most of the resources were extracted from government forest. In 1957 forests were nationalized and traditional use regulation and dispute resolution was abandoned (Adhikari Citation1990; Bhatta et al. Citation2010). Since then, there has been little local participation in management (Poudyal et al. Citation2020) and regulation of use has been ineffective (Shrestha Citation1999; Chaudhary et al. Citation2016) resulting in a “tragedy of commons” (Hardin Citation1968). Because people felt that their use of resources was more constrained within the PA, as has also been found in Bardia National Park in south-western Nepal (Shova and Hubacek Citation2011), there was an increase in the illegal extraction of resources from the government forests by natural resource dependent marginalized and vulnerable groups who gained little from biodiversity protection within the PAs (Acharya et al. Citation2008; Bhatta et al. Citation2010). More recently, there has been a shift in the management of the PAs from the nature-centric “fine and fence approach” (Heinen and Kattel Citation1992; Bhattarai et al. Citation2017) to more participatory human-centered paradigms (e.g. Paudel et al. Citation2007; Spiteri and Nepal Citation2008). Recent examples of participatory policy initiatives linking conservation and livelihoods in and around PAs were the management of buffer zone and community forests. Similarly, the collaborative approach to forest management and governance practiced in the communal forests, which include the participatory forest management regimes undertaken under community, collaborative and leasehold forestry management systems, in conservation areas and buffer zones (Poudel Citation2019) have been demonstrably more effective than had been the top-down state governance that the communal systems replaced (Acharya Citation2002; Shrestha and Shrestha Citation2010; Pathak et al. Citation2017; Paudyal et al. Citation2017) since their formalization in the 1980s (Gilmour and Fisher Citation1991). However, it was apparent that participatory approaches had not prevented all over-exploitation. The weak legal and organizational capacity of local institutions, heavy emphasis on infrastructure development, and the limited participation of deprived populations and marginalized groups have reduced the effectiveness of participatory governance elsewhere in Nepal (Paudel et al. Citation2007; Acharya et al. Citation2008). In our study, medicinal plants continued to be collected from within the PA, apparently without constraint, and communities close to the park boundaries are often pressured to collect illegally (Karanth et al. Citation2006; Thapa and Chapman Citation2010). While our research showed that communities close to the park were able to take advantage of tourism opportunities, park regulations did not appear to have stopped exploitation of other ecosystem goods or services. As a result, red pandas and their habitat are still likely to be under pressure under both tenures.

4.2. Trends in ecosystem goods and services

Of the 53 provisioning and cultural ecosystem goods and services identified as being obtained from red panda habitats in the earlier study (Bhatta et al. Citation2020), seven were considered particularly important to local livelihoods: bamboo, medicinal plants, firewood, fodder and bedding for animals, transhumance, recreational activities and ecotourism, and interactions with religious sites. The greatest contrast between demand and availability over the last two decades has been for medicinal plants, some of which were considered to be over-exploited by FGD participants. For bamboo, use was thought to have stayed the same but availability had declined whereas the condition of upland pastures had declined despite a reduction in usage. Little change in the availability of the other services was noted but there had been changes in the use of the landscape within the national park where people had shifted from transhumance and pastoralism to tourism as a source of income, a change that could benefit the red panda by reducing bamboo use. The picture painted by the FGD’s and household survey was of a society in transition, particularly within the PA, with transhumance being replaced by other forms of income. The trends noticed were in keeping with regional (e.g. IPBES Citation2018; Wester et al. Citation2019) and global assessments (e.g. MEA Citation2005; Díaz et al. Citation2019) of the demand for medicinal plants and nature-based tourism and for national trends for services like firewood and fodder (Panchase mountain ecological region of western Nepal, Adhikari et al. Citation2019; central mid-hills of Nepal, Paudyal et al. Citation2015).

4.3. Impacts of change on local livelihoods and the red panda

At the time of the survey, income from ecotourism in Nepal had been growing rapidly (DNPWC Citation2012), benefiting people living in PA buffer zones (Acharya et al. Citation2008) although not those outside the immediate vicinity of the parks (MoFSC Citation2017). Even near parks in Nepal, the greatest benefits were in places receiving international tourists (Paudel et al. Citation2007). The reason that people in communities around RNP continued to rely on the park for many goods and services may be because most tourists were Nepalese who had lower spending power. Nevertheless, there was a marked decline in transhumant pastoralism which was having consequences not only for the ways in which mountain communities were earning their living but potentially also on their traditional and cultural identity (Negi Citation2007; Gentle and Thwaites Citation2016; Bhatta et al. Citation2020) since fewer people were visiting shrines or maintaining the religious practices associated with journeys to and from the mountain pastures.

How these social changes were affecting the red panda population is unclear. Transhumant grazing has been associated with attacks by livestock guard dogs on red pandas both in our study locations (Bhatta et al. Citation2014; Sharma et al. Citation2014b) and elsewhere in Nepal (Williams Citation2003) so potentially a decline in the practice of transhumance could benefit the panda. However, the ongoing loss of bamboo, the panda’s sole food source, and disturbance that may arise from medicinal plant collection, which occurs largely during the spring breeding season of the panda (Roberts and Gittleman Citation1984), could be having a negative effect depending on whether trends in panda populations were being driven by food availability or predation.

4.4. Key drivers of change

Many of the drivers of change identified in the FGDs are common to poor rural communities in the broader region (MEA Citation2005; IPBES Citation2018; MoFE Citation2018; Díaz et al. Citation2019; Wester et al. Citation2019). Until recently, there had been limited opportunity to substitute reliance on ecosystem goods and services (Roe Citation2008), with poverty driving declines in natural resources (Squires Citation2014). Where opportunities had arisen to make additional money, such as for high-value medicinal plants, the collection had tended to be unsustainable because those collecting the plants were receiving a small fraction of their market value (Olsen and Bhattarai Citation2005; Ghimire et al. Citation2008). Similarly, the opportunities becoming available from infrastructure development, particularly the roads that were improving access to markets, were poorly regulated leading to environmental damage that can offset short-term advantages (Chaudhary et al. Citation2016; MoFE Citation2018). Underpinning the negative effects of these drivers of change has been a weakness in institutional arrangements that has meant that resources were harvested without constraint or monitoring (Fleischman Citation2014; Barnes and van Laerhoven Citation2015; Bhatta et al. Citation2022a), compromising the sustainability of traditional resource use and degrading biodiversity, habitats and the viability of rural livelihoods (Squires Citation2014; Uprety et al. Citation2016). In particular, the replacement of traditional forms of governance, such as that used to manage use of upland pastures (Aryal et al. Citation2013), with poorly administered state governance (Bhatta et al. Citation2022a) has meant resources like grasslands and medicinal plants have become common pool resources with little or no control on their exploitation (Ojha et al. Citation2019). Exactly the same process has happened in places like Inner Mongolia (Briske et al. Citation2015) and elsewhere in mountainous regions of the Asia-Pacific (ADB Citation2017) where conventional livelihoods and cultures are being transformed (Dutta and Bilbao-Osorio Citation2012). In the process, traditional bonds between people and nature have been removed (Oviedo and Jeanrenaud Citation2007) compromising rich biological and cultural diversity (Dudley et al. Citation2010) as new cultural influences become pervasive (IPBES Citation2018). How such changes will affect the panda and its habitat will depend on the quality of the governance of the ecosystems and the services they provide. Currently, high levels of rent-seeking are hampering a desire by local communities for greater control of resource use and more equitable benefit-sharing (Bhatta et al. Citation2022a), but there is widespread acceptance of the concept of payment for ecosystem services (Bhatta et al. Citation2022b).

4.5. Research implications and recommendations

Three main questions arise from the research concerning the sustainability of the use of red panda habitat in western Nepal, questions that are likely to apply across the species range. The most important highlights the need for much greater knowledge of the demand and supply, distribution and abundance, consumption patterns, trade, and threats involved in the industry surrounding medicinal plants (Ghimire et al. Citation2008). Existing legislation, plans, and policies to regulate and manage these plants have been ineffective in mountainous parts of the country (Olsen and Helles Citation1997; Larsen et al. Citation2000) leading to rapid over-exploitation of the plants. Such research would need to consider individual medicinal plant species, as some harvest may be more harmful or sustainable than others and, from the perspective of red panda conservation, would need to consider which aspects of the medicinal plant industry are likely to have the greatest impact on panda conservation. There is also a strong need for local involvement in this research as well as in the regulation and monitoring of harvesting (Poudyal et al. Citation2020).

A second area of research is the interaction between bamboo use by pandas and people. Bamboo mortality following flowering is now considered a threat to the red panda (Williams et al. Citation2011; Bista et al. Citation2017). The research question thus concerns how human take of bamboo is exacerbating the declines driven by mass flowering events – there may be a risk from overharvesting as new stands germinate from seeds which could hugely reduce or even eliminate bamboo across large parts of the landscape where it occurred previously.

Third, changes in and around the study region to improve the accessibility and connectivity of remote communities are likely to be having multiple flow-on effects that are not fully understood. Modifications to improve the provision of a single service can have consequences for multiple services delivered by the ecosystem (MEA Citation2005). However, rarely it is possible to optimize all ecosystem benefits so trade-offs are necessary (Polasky et al. Citation2008; Smith et al. Citation2012; King et al. Citation2015). While trade-offs between existing and future use of the same ecosystem goods and services (Carpenter et al. Citation2006; Rodríguez et al. Citation2006) do not necessarily always have negative impacts (Bennett et al. Citation2009; Turkelboom et al. Citation2016), there needs to be a full understanding of the scope of influence that changes can bring to a community. In our example, a positive impact could be argued for RNP (Bhatta et al. Citation2020), and for other red panda habitats of Nepal (Bista Citation2018) because seasonal transhumant grazing is being replaced as a livelihood by nature-based tourism with potential benefits for biodiversity conservation (Lindsey et al. Citation2007; Baral et al. Citation2017). However, the same loss of transhumance as a livelihood and lifestyle could be considered to be a negative outcome as it is a practice that annually reaffirmed cultural and religious ties to the red panda habitat. But nor should the change in practice be attributed solely to the rise of tourism as a livelihood as it is also being driven by reduced access to lowland pastures in winter, a consequence of novel communal forest management (Gentle and Thwaites Citation2016) that has replaced traditional governance institutions that allowed visiting pastoralists to graze in forests and may have benefitted both pastoralists and local communities (Singh et al. Citation2015).

This set of three research findings highlights the need for studies aiming to further red panda conservation to expand in their breadth to consider more than distribution, habitat requisites, and threats. The research also needs to be geographically specific given that the social and cultural milieu within which the panda exists will vary from place to place (DNPWC & DFSC Citation2018), just as we found to be the case inside and outside RNP. Understanding the values of ecosystem goods and services from habitats then allows the development of management interventions that are appropriately targeted for the communities and threats at each location. This is particularly true for red panda habitat that falls outside PAs, as is the case for nearly 70% of red panda habitats in Nepal (MoFSC Citation2014b).

The sustainable management of ecosystem goods and services from the red panda habitat is possible if policymakers appreciate the root causes and impacts of unsustainable usage, line agencies implement comprehensive and targeted policies effectively, and communities understand and embrace the reasons for policy change both outside and inside PAs. Similarly, PA management plans should consider local context to ensure they have support from communities around the park. While there is a de facto recognition of greater community use of PAs than is acknowledged by the National Parks Act, the legal changes have not yet been implemented to accommodate community perspectives (Bhattarai et al. Citation2017). Similarly, community forestry, including ceding greater control of forests to local communities including effective governance and the implementation of appropriate compliance measures aimed to reduce over-exploitation of forest resources (Ranjit Citation2019), has not yet been implemented on a large scale in Nepal’s mountainous regions. Our approach of linking biological diversity, ecosystem services, and livelihoods may be useful in other red panda habitats as well as being applicable to the conservation of other threatened and flagship species in elsewhere in Nepal and in mountainous regions everywhere.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a synopsis of perceived trends in supply and demand for ecosystem goods and services obtained from red panda habitat that are considered significant to the livelihoods inside and outside a PA in the north-western mountains of Nepal. Assessment of variation in use and availability of the ecosystem goods and services from these mountain landscapes in the past two decades provides an understanding of drivers of change in the habitat and likely trends if these drivers persist. Understanding changes in the flows of ecosystem goods and services from red panda habitat, and the factors underlying those changes, may be relevant simultaneously to the protection of the red panda, its habitat and associated biodiversity, to the sustainability of the use of ecosystem goods and services, and to the improvement of local livelihoods. In this context, this study provides a cornerstone for formulating holistic red panda habitat governance approaches and strategies at the nexus of biological diversity, ecosystem services and livelihoods.

Credit authors statement

Manoj Bhatta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original draft preparation, Project administration.

Kerstin Zander: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Original draft preparation, Supervision.

Stephen Garnett: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Original draft preparation, Supervision.

Supplementary Materials

Download PDF (604.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions and support of local communities, key informants, focus group discussants, participatory three-dimensional mapping participants, and household survey respondents. We are thankful to the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and the Department of Forests and Soil Conservation, Nepal for providing research approval. We are equally grateful to District Forest Office, Jumla, Rara National Park (RNP), Mugu, and RNP buffer zone committee members for their constant assistance and cooperation in data collection. Special thanks to Field Research Assistants, Dikra Prasad Bajgai (team leader), Madan Subedi, Bhim Fadera, Raj Bauwal, and Dipesh Acharya for their efforts and integrity during the fieldwork. Our thanks and appreciation to Er. Abhishek B.C., executive chairman of Pact Consultant (P.) Ltd., Kathmandu, Nepal who facilitated with arrangements of field assistants and provided office space during the planning phase of the field study. We are equally indebted to Dr. Beau Austin and Rohan Fisher for their constant support in preparing and designing data collection tools and techniques. The research was supported by the Australian Postgraduate Award, postgraduate research funding under the College of Engineering, IT, and Environment of Charles Darwin University, Australia. Human research ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Charles Darwin University (H17030).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2022.2107079

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Acharya KP. 2002. Twenty-four years of community forestry in Nepal. Int for Rev. 4(2):149–156. doi:10.1505/IFOR.4.2.149.17447.

- Acharya KP, Adhikari J, Khanal DR. 2008. Forest tenure regimes and their impact on livelihoods in Nepal. J Livelihood. 7:6–18.

- Acharya RM, Maraseni T, Cockfield G. 2019. Global trend of forest ecosystem services valuation – an analysis of publications. Ecosyst Serv. 29:100979. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100979.

- [ADB] Asian Development Bank. 2017. A region at risk: the human dimensions of climate change in Asia and the Pacific. Asian Development Bank.

- Adhikari J. 1990. Is community forestry a new concept? An analysis of the past and present policies affecting forest management in Nepal. Soc Nat Resour. 3(3):257–265. doi:10.1080/08941929009380723.

- Adhikari S, Baral H, Sudhir Chitale V, Nitschke CR. 2019. Perceived changes in ecosystem services in the Panchase Mountain Ecological Region, Nepal. Resources. 8(1):4. doi:10.3390/resources8010004.

- Aryal A, Brunton D, Pandit R, Kumar Rai R, Shrestha UB, Lama N, Raubenheimer D. 2013. Rangelands, conflicts, and society in the Upper Mustang Region, Nepal. Mt Res Dev. 33(1):11–18. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-12-00055.1.

- Balvanera P, Brauman KA, Cord AF, Drakou EG, Geijzendorffer IR, Karp DS, Martín-López B, Mwampamba TH, Schröter M. 2022. Essential ecosystem service variables for monitoring progress towards sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 54:101152. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2022.101152.

- Baral H, Jaung W, Bhatta LD, Phuntsho S, Sharma S, Paudyal K, Zarandian A, Sears R, Sharma R, Dorji T. 2017. Approaches and tools for assessing mountain forest ecosystem services. Working paper. Bogor (Indonesia): Center for International Forestry Research.

- Barnes C, Van Laerhoven F. 2015. Making it last? Analysing the role of NGO interventions in the development of institutions for durable collective action in Indian community forestry. Environ Sci Policy. 53:192–205. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2014.06.008.

- Bennett EM, Peterson GD, Gordon LJ. 2009. Understanding relationships among multiple ecosystem services. Ecol Lett. 12(12):1394–1404. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01387.x.

- Bhatta M, Garnett ST, Zander KK. 2022b. Exploring options for a PES-like scheme to conserve red panda habitat and livelihood improvement in western Nepal. Ecosyst Serv. 53:101388. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2021.101388.

- Bhatta L, Lian K, Chun J. 2010. Policies and legal frameworks of protected area management in Nepal. Sustain Matters. 1:157–188.

- Bhatta M, Shah KB, Devkota B, Paudel R, Panthi S. 2014. Distribution and habitat preference of red panda (Ailurus fulgens fulgens) in Jumla district, Nepal. Open J Ecol. 4(15):989. doi:10.4236/oje.2014.415082.

- Bhatta M.Zander KK, Austin BJ, & Garnett ST. 2020. Societal recognition of ecosystem service flows from red panda habitats in Western Nepal. Mt Res Dev. 40(2):R50–R60. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-19-00061.1.

- Bhatta M, Zander KK, Garnett ST. 2022a. Governance of forest resource use in western Nepal: current state and community preferences. Ambio. 51(7):1711–1725. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01694-9.

- Bhattarai BR, Wright W, Poudel BS, Aryal A, Yadav BP, Wagle R. 2017. Shifting paradigms for Nepal’s protected areas: history, challenges and relationships. J Mountain Sci. 14(5):964–979. doi:10.1007/s11629-016-3980-9.

- Bista D. 2018. Communities in frontline in red panda conservation, eastern Nepal. Himalayan Nat. 1:11–12.

- Bista D, Bhattrai B, Shrestha S, Lama ST, Dhamala MK, Acharya KP, Jnawali SR, Bhatta M, Das AN, Sherpa AP. 2022. Bamboo distribution in Nepal and its impact on red pandas. In: Glatston AR, editor. Red panda. Biology and conservation of the first panda. New York: Academic Press; p. 353–368.

- Bista D, Paudel P, Ghimire S, Shrestha S. 2016. National survey of red panda to assess habitat and distribution in Nepal. Final report submitted to WWF/USAID/Hariyo Ban Program.

- Bista D, Shrestha S, Sherpa P, Thapa GJ, Kokh M, Lama ST, Khanal K, Thapa A, Jnawali SR, Yue B-S. 2017. Distribution and habitat use of red panda in the Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape of Nepal. PLoS One. 12(10):e0178797. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0178797.

- Briske DD, Zhao M, Han G, Xiu C, Kemp DR, Willms W, Havstad K, Kang L, Wang Z, Wu J, et al. 2015. Strategies to alleviate poverty and grassland degradation in Inner Mongolia: intensification vs production efficiency of livestock systems. J Environ Manage. 152:177–182. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.036.

- Carpenter SR, Bennett EM, Peterson GD. 2006. Scenarios for ecosystem services: an overview. Ecol Soc. 11(1):art29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267787

- CBS. 2012. National population and housing census 2011. Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics. National Planning Commission Secretariat, Government of Nepal.

- Chaudhary RP, Paudel KC, Koirala SK. 2009. Nepal Fourth National Report to the convention on biological diversity. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation.

- Chaudhary RP, Uprety Y, Rimal SK. 2016. Chapter 12.2.-Deforestation in Nepal: causes, consequences, and responses. In: Shroder JF & Sivanpillai R, editors. Biological and environmental hazards, risks, and disasters. Boston, MA: Academic Press.

- DDC. 2013. District profile analysis. Jumla: District Development Committee.

- DDC. 2016. Mugu district development plan 2017–2018. Jumla: District Development Committee.

- de Groot RS, Alkemade R, Braat L, Hein L, Willemen L. 2010. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol Complexity. 7(3):260–272. doi:10.1016/j.ecocom.2009.10.006.

- Denscombe M. 2008. Communities of practice: a research paradigm for the mixed methods approach. J Mix Methods Res. 2(3):270–283. doi:10.1177/1558689808316807.

- Dewalt KM, Dewalt BR. 2011. Participant observation: a guide for fieldworkers.

- DNPWC 2012. Annual report 2011–2012 (in Nepali). Kathmandu: Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation.

- DNPWC & BCN. 2012. Conserving biodiversity & delivering ecosystem services at important bird areas in Nepal. Cambridge: Birdlife International.

- DNPWC & DFSC. 2018. Red panda conservation action plan for Nepal 2019–2023. Kathmandu: Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and Department of Forests and Soil Conservation.

- Dudley N, Bhagwat S, Higgins-Zogib L, Lassen B, Verschuuren B, Wild R. 2010. Conservation of biodiversity in sacred natural sites in Asia and Africa: a review of the scientific literature. In: Verschuuren B, Wild RA, McNeely J, Oviedo G, editors. Sacred natural sites: conserving nature and culture. London and Washington (DC): Earthscan; p. 19–32.

- Dutta S, Bilbao-Osorio B. 2012. Living in a hyperconnected world. The global information technology report.

- Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. 2016. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat. 5(1):1–4. doi:10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11.

- Fleischman FD. 2014. Why do foresters plant trees? Testing theories of bureaucratic decision-making in Central India. World Dev. 62:62–74. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.008.

- Fleming B, Fleming JP. 2009. A watershed conservation success story in Nepal: land use changes over 30 years. Waterlines. 28(1):29–46. doi:10.3362/1756-3488.2009.004.

- Gentle P, Maraseni TN. 2012. Climate change, poverty and livelihoods: adaptation practices by rural mountain communities in Nepal. Environ Sci Policy. 21:24–34. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.03.007.

- Gentle P, Thwaites R. 2016. Transhumant pastoralism in the context of socioeconomic and climate change in the mountains of Nepal. Mt Res Dev. 36(2):173–182. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-15-00011.1.

- Ghimire S, Awasthi B, Rana S, Rana H, Bhattarai R. 2015. Status of exportable, rare and endangered medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) of Nepal. Kathmandu: Department of Plant Resources.

- Ghimire SK, Sapkota I, Oli B, Rai-Parajuli R. 2008. Non-timber forest products of Nepal Himalaya: database of some important species found in the mountain protected areas and surrounding regions.

- Gilmour DA, Fisher RJ. 1991. Villagers, forests, and foresters: the philosophy, process, and practice of community forestry in Nepal.

- Glatston A, Gebauer A. 2022. People and red pandas: the red pandas’ role in economy and culture. In: Glatston AR, editor. Red panda. Biology and conservation of the first Panda. New York: Academic Press.

- Glatston A, Wei F, Than Zaw Sherpa A. 2015. Ailurus fulgens (errata version published in 2017). The IUCN red list of threatened species. e. T714A110023718. [accessed 2020 Aug 10]. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T714A45195924.en.

- Government of Nepal. 1979 Sep 10. Himalayan National Park Rules, 2036 (1979). Nepal Gazette 2036.05.25.

- Government of Nepal. 2019 Oct 14. The Forests Act, 2019 (2076). Nepal Gazzette. 2076(06.27).

- Hardin G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science. 162(3859):1243–1248. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243.

- He S, Gallagher L, Su Y, Wang L, Cheng H. 2018. Identification and assessment of ecosystem services for protected area planning: a case in rural communities of Wuyishan National Park pilot. Ecosyst Serv. 31:169–180. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.04.001.

- Heinen JT, Kattel B. 1992. Parks, people, and conservation: a review of management issues in Nepal’s protected areas. Popul Environ. 14(1):49–84. doi:10.1007/BF01254607.

- Holloway I, Galvin K. 2016. Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. 4th ed. Chichester (UK); Ames (IA): John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- IPBES. 2018. The IPBES regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Asia and the Pacific. In: Karki M, Senaratna Sellamuttu S, Okayasu S, Suzuki W, editors.Secretariat of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn. 612. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3237373.

- IPBES. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem servicesDíaz S, Settele J, Brondízio ES, Ngo HT, Guèze M, Agard J, Arneth A, Balvanera P, Brauman KA, Butchart SHM, et al., editors. Bonn: IPBES Secretariat. 56.

- Karanth KK, Curran LM, Reuning-Scherer JD. 2006. Village size and forest disturbance in Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary, Western Ghats, India. Biol Conserv. 128(2):147–157. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.024.

- Kawulich BB. 2005. Participant observation as a data collection method 6.

- King, E, Cavender-Bares J, Balvanera P, Mwampamba, TH, Polasky S. 2015. Trade-offs in ecosystem services and varying stakeholder preferences: evaluating conflicts, obstacles, and opportunities. Ecol Soc. 20:15.

- Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. 1952. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 47(260):583–621. doi:10.1080/01621459.1952.10483441.

- Lamsal P, Kumar L, Atreya K, Pant KP. 2018. Forest ecosystem services in Nepal: a retrospective synthesis, research gaps and implications in the context of climate change. Int for Rev. 20(4):506–537. doi:10.1505/146554818825240647.

- Larsen HO, Olsen CS, Boon TE. 2000. The non-timber forest policy process in Nepal: actors, objectives and power. For Pol Econ. 1(3–4):267–281. doi:10.1016/S1389-9341(00)00013-7.

- Lindsey PA, Alexander R, Mills MGL, Romañach S, Woodroffe R. 2007. Wildlife viewing preferences of visitors to protected areas in South Africa: implications for the role of ecotourism in conservation. J Ecotourism. 6(1):19–33. doi:10.2167/joe133.0.

- Longhurst R. 2003. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Key Methods Geogr. 3:143–156.

- Måren IE, Karki S, Prajapati C, Yadav RK, Shrestha BB. 2015. Facing north or south: does slope aspect impact forest stand characteristics and soil properties in a semiarid trans-Himalayan valley? J Arid Environ. 121:112–123. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2015.06.004.

- Maselli D. 2012. Promoting sustainable mountain development at the global level. Mt Res Dev. 32(S1):S1. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-11-00120.S1.

- MEA. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. millennium ecosystem assessment. Washington (DC): World Resources Institute.

- MoFE 2018. Nepal sixth national report to the convention on biological diversity. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment, Singha Durbar.

- MoFSC. 2014a. Nepal fifth national report to convention on biological diversity. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar.

- MoFSC. 2014b. Nepal national biodiversity strategy and action plan 2014–2020. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar.

- MoFSC. 2017. Forest investment program: investment plan for Nepal. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar.

- Morgan DL, Spanish MT. 1984. Focus groups: a new tool for qualitative research. Qual Sociol. 7(3):253–270. doi:10.1007/BF00987314.

- Moritz M, Behnke R, Beitl CM, Bird RB, Chiaravalloti RM, Clark JK, Crabtree SA, Downey SS, Hamilton IM, Phang SC, et al., 2018. Emergent sustainability in open property regimes. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 115:12859–12867.

- Mukherjee N. 1997. Participatory appraisal of natural resources. New Delhi (India): Concept Publishing Company.

- Negi CS. 2007. Declining transhumance and subtle changes in livelihood patterns and biodiversity in the Kumaon Himalaya. Mt Res Dev. 27(2):114–118. doi:10.1659/mrd.0818.

- Ojha HR, Ghate R, Dorji L, Shrestha A, Paudel D, Nightingale A, Shrestha K, Watto MA, Kotru R. 2019. Governance: key for environmental sustainability in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. In: Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha AB, editors. The Hindu Kush himalaya assessment. Cham: Springer International Publishing; p. 545–578.

- Olsen CS, Bhattarai N. 2005. A typology of economic agents in the Himalayan plant trade. Mt Res Dev. 25(1):37–43. doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2005)025[0037:ATOEAI]2.0.CO;2.

- Olsen CS, Helles F. 1997. Medicinal plants, markets, and margins in the Nepal Himalaya: trouble in paradise. Mt Res Dev. 17(4):363–374. doi:10.2307/3674025.

- Ostrom E 2007. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 104:15181–15187.

- Oviedo G, Jeanrenaud S. 2007. Protecting sacred natural sites of indigenous and traditional peoples. In: Mallarach J-M , Papayannis T, editors. Protected areas and spirituality: proceedings of the first workshop of the Delos initiative. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- Palomo I. 2017. Climate change impacts on ecosystem services in high mountain areas: a literature review. Mt Res Dev. 37:179–187.

- Panthi S, Coogan SCP, Aryal A, Raubenheimer D. 2015. Diet and nutrient balance of red panda in Nepal. Sci Nat. 102(9–10):54. doi:10.1007/s00114-015-1307-2.

- Pathak B, Xie Y, Bohara R. 2017. Community based forestry in Nepal: status, issues and lessons learned. Int J Sci. 3(3):119–129. doi:10.18483/ijSci.1232.

- Paudel NS, Budhathoki P, Sharma UR. 2007. Buffer zones: new frontiers for participatory conservation. J Livelihood. 6:44–53.

- Paudyal K, Baral H, Burkhard B, Bhandari SP, Keenan RJ. 2015. Participatory assessment and mapping of ecosystem services in a data-poor region: case study of community-managed forests in central Nepal. Ecosyst Serv. 13:81–92. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.01.007.

- Paudyal K, Baral H, Lowell K, Keenan RJ. 2017. Ecosystem services from community-based forestry in Nepal: realising local and global benefits. Land Use Pol. 63:342–355. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.01.046.

- Peters MK, Hemp A, Appelhans T, Becker JN, Behler C, Classen A, Detsch F, Ensslin A, Ferger SW, Frederiksen SB. 2019. Climate–land-use interactions shape tropical mountain biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Nature. 568(7750):88–92. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1048-z.

- Polasky S, Nelson E, Camm J, Csuti B, Fackler P, Lonsdorf E, Montgomery C, White D, Arthur J, Garber-Yonts B, et al. 2008. Where to put things? Spatial land management to sustain biodiversity and economic returns. Biol Conserv. 141(6):1505–1524. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.03.022.

- Poudel DP. 2019. Migration, forest management and traditional institutions: acceptance of and resistance to community forestry models in Nepal. Geoforum. 106:275–286. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.09.003.

- Poudyal BH, Maraseni T, Cockfield G. 2020. Scientific forest management practice in Nepal: critical reflections from stakeholders’ perspectives. Forests. 11(1):27. doi:10.3390/f11010027.

- Price M. 2015. Mountains: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ranjit Y. 2019. History of forest management in Nepal: an analysis of political and economic perspective. Econ J Nepal. 42(3–4):12–28. doi:10.3126/ejon.v42i3-4.36030.

- Rasul G, Chettri N, Sharma E. 2011. Framework for valuing ecosystem services in the Himalayas. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) technical report. Kathmandu (Nepal): ICIMOD.

- Roberts MS, Gittleman JL. 1984. Ailurus fulgens. Mammal Species. (222):1. doi:10.2307/3503840.

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez D, Bomhard B, Butchart SHM, Foster MN. 2011. Progress towards international targets for protected area coverage in mountains: a multi-scale assessment. Biol Conserv. 144(12):2978–2983. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.08.023.

- Rodríguez JP, Beard TD, Bennett EM, Cumming GS, Cork SJ, Agard J, Dobson AP, Peterson GD. 2006. Trade-offs across space, time, and ecosystem services. Ecol Soc. 11(1):art28.

- Roe D. 2008. Trading nature: a report, with case studies, on the contribution of wildlife trade management to sustainable livelihoods and the millennium development goals.

- Romeo R, Vita A, Testolin R, Hofer T. 2015. Mapping the vulnerability of mountain peoples to food insecurity.

- Schaafsma M, van Beukering PJH, Oskolokaite I. 2017. Combining focus group discussions and choice experiments for economic valuation of peatland restoration: a case study in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Ecosyst Serv. 27:150–160. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.08.012.

- Sharma HP, Belant JL, Swenson JE. 2014b. Effects of livestock on occurrence of the Vulnerable red panda Ailurus fulgens in Rara National Park, Nepal. Oryx. 48(2):228–231. doi:10.1017/S0030605313001403.

- Sharma E, Molden D, Rahman A, Khatiwada YR, Zhang L, Singh SP, Yao T, Wester P. 2019. Introduction to the Hindu Kush Himalaya assessment. In: Wester P, Wester P, Wester P , Wester P, editors. The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: mountains, climate change, sustainability and people. Cham: Springer International Publishing; p. 1–16.

- Sharma HP, Swenson JE, Belant JL. 2014a. Seasonal food habits of the red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in Rara National Park, Nepal Hystrix. Italian J Mammal. 25:47–50.

- Sherpa AP, Lama ST, Shrestha S, Williams B. , Bista D. 2022. Red pandas in Nepal: a community-based approach to landscape-level conservation. In: Glatston AR, editor. Red panda. Biology and conservation of the first Panda. New York: Academic Press.

- Shi L, Han L, Yang F, Gao L. 2019. The evolution of sustainable development theory: types, goals, and research prospects. Sustainability. 11(24):7158. doi:10.3390/su11247158.

- Shova T, Hubacek K. 2011. Drivers of illegal resource extraction: an analysis of Bardia National Park, Nepal. J Environ Manage. 92(1):156–164. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.08.021.

- Shrestha V. 1999. Forest resources of Nepal: destruction and environmental implications. Contrib Nepalese Stud. 26:295–307.

- Shrestha B, Shrestha S. 2010. Biodiversity conservation in community forests of Nepal: rhetoric and reality. Int J Biodivers Conserv. 2:98–104.

- Shrestha B, Ye Q, Khadka N. 2019. Assessment of ecosystem services value based on land use and land cover changes in the transboundary Karnali River Basin, Central Himalayas. Sustainability. 11:3183.

- Singh RK, Singh A, Garnett ST, Zander KK, Lobsang, Tsering D. 2015. Paisang (Quercus griffithii): a keystone tree species in sustainable agroecosystem management and livelihoods in Arunachal Pradesh, India. Environ Manage. 55(1):187–204. doi:10.1007/s00267-014-0383-y.

- Smith FP, Gorddard R, House APN, Mcintyre S, Prober SM. 2012. Biodiversity and agriculture: production frontiers as a framework for exploring trade-offs and evaluating policy. Environ Sci Policy. 23:85–94. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.07.013.

- Spiteri A, Nepal SK. 2008. Distributing conservation incentives in the buffer zone of Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Environ Conserv. 35(1):76–86. doi:10.1017/S0376892908004451.

- Squires D. 2014. Biodiversity conservation in Asia. Asia Pac Policy Stud. 1(1):144–159. doi:10.1002/app5.13.

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, Teddlie BC. 1998. Mixed methodology: combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications.

- Tewari DN. 1993. A monograph on bamboo. India: Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education, Dehra Dun.

- Thapa GB. 1996. Land use, land management and environment in a subsistence mountain economy in Nepal. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 57(1):57–71. doi:10.1016/0167-8809(96)88021-2.

- Thapa S, Chapman DS. 2010. Impacts of resource extraction on forest structure and diversity in Bardia National Park, Nepal. For Ecol Manage. 259(3):641–649. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2009.11.023.

- Tongco MDC. 2007. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobotany Res Appl. 5:147–158. doi:10.17348/era.5.0.147-158.

- Turkelboom F, Thoonen M, Jacobs S, Berry P. 2016. Ecosystem service trade-offs and synergies. Ecol Soc. 21(1):43. doi:10.5751/ES-08345-210143.

- Uprety Y, Poudel RC, Gurung J, Chettri N, Chaudhary RP. 2016. Traditional use and management of NTFPs in Kangchenjunga landscape: Implications for conservation and livelihoods. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 12(1):19. doi:10.1186/s13002-016-0089-8.

- Vira B, Kontoleon A. 2012. Dependence of the poor on biodiversity: which poor, what biodiversity. Wiley Online Library.

- Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha AB. 2019. The Hindu Kush Himalaya assessment. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Williams BH. 2003. Red panda in eastern Nepal: how do they fit into ecoregional conservation of the eastern Himalaya. Conserv Biol Asia. 16:236–250.

- Williams BH, Dahal BR, Subedi TR. 2011. Project Punde Kundo: community-based monitoring of a red panda population in eastern Nepal. Red Panda. Elsevier.

- WTTC. 2019. Travel and tourism economic impact 2019. World Travel and Tourism Council. [accessed 2020 Nov 4]. https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact.