?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

A study targeting the Bale Mountains National Park in Ethiopia was conducted to gain a deeper understanding of local communities’ opinion on benefits and disbenefits of protected areas and existing benefit-sharing mechanisms and to suggest future research for development direction related to the management of protected areas. Household surveys, key informant interviews and focus group discussions were tools used to collect data. The results obtained through the analysis of the factors affecting the attitude of local communities on the park and its management demonstrated that efforts should be concentrated on improving communication with local communities and short-term economic benefits as well as identifying the reasons for the unhealthy relationships and addressing them. These issues can partly be addressed through creating and supporting effective and functioning multi-stakeholder platforms for dialogue and co-production of knowledge, continuous meetings and awareness-raising campaigns and integrating more income-generating activities. The results also suggested that park management and government authorities use their authority to decide how local communities should participate in Bale Mountains National Park management initiatives. Such a top-down approach affects the sustainability of the efforts to conserve protected areas because local stakeholders lack incentives to participate. This also leads to inadequate understanding of the complex relationships between people and protected areas they depend on and the inability to tailor management responses to specific needs and conditions. The study discussed the implications of the results for future planning and management of protected areas and forwarded recommendations for policy and future research for development directions.

EDITED BY:

Introduction

The world is rapidly losing biodiversity through the degradation of ecosystems due mainly to land use change, climate change, pollution and invasion of alien species (IPBES Citation2019) and this, ultimately, brings negative impact on the healthy performance of ecosystems. Protected areas are a key approach to global ecological conservation efforts and are recognized as the most important way to protect species in their natural habitats (Watson et al. Citation2014). Over the last decades, massive efforts have been made to manage protected areas using diverse strategies (Vimal et al. Citation2021). This same study further elaborated that globally 41% of the terrestrial protected areas are managed through a strict control of human activities to conserve wild areas, 13% is dedicated to particular species or habitats and often requiring active management and 25% preserves both natural and cultural values and promotes the sustainable use of resources.

However, a review by Palomo et al. (Citation2014) and Hoffmann (Citation2022) argue that most of these protected areas are still managed as islands and lacks clear conceptual framework that integrates them into the surrounding landscape. These same studies further elaborated that protected areas have been affected by (a) both direct and indirect drivers of change or pressures (e.g. Land-use change, climate change, invasive alien species, overexploitation and sociopolitical, economic cultural changes), (b) the bias in the location and size of current protected areas (e.g. located in rural and mountainous areas without considering ecological integrity) and (c) the disconnection between protected areas and society. The third limitation particularly restricts access to several ecosystem services (Estifanos et al. Citation2020), and ignores people’s needs, provoke conflicts and can lead to less support from local communities (Woodhouse et al. Citation2018; Benetti and Langemeyer Citation2021). Similarly, Bermejo et al. (Citation2020) indicated that land-sparing strategies such as protected areas have often been sources of conflicts between local people and conservation institutions. This could be attributed to the potential of protected areas to eliminate traditional activities. In general, studies (e.g. Poudel Citation2019; Ayivor et al. Citation2020; Maxwell et al. Citation2020) demonstrated that poor representation of habitats, lack of connectivity between protected areas, lack of funds, poor management and human activities are among the major challenges of the management of protected areas.

The practice of conservation has a long history in Ethiopia which dates back to Emperor Zerea Yacob (1434–1468) (Teressa Citation2017), and Ethiopia becomes one of the few countries in the world which uses the management of protected areas as one of the strategies to conserve fauna and flora (Tefera Citation2011). In line with this, the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority, established in 2008, currently manages 14 National Parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries and Reserves covering approximately 3.9 million hectares of natural habitats, including 1.8 million hectares of forests and woodlands (van Zyl Citation2015). The Ethiopian protected areas are unique in terms of their biodiversity and contain high levels of endemism (van Zyl Citation2015). Though the country’s protected areas play an important role in the sustainable development of the national economy by providing diverse ecosystem services and tangible economic benefits to the local communities, they operate at a level substantially below their socio-economic potential. Because many of the protected areas are not legally gazetted, receive inadequate funding, are understaffed and ill-equipped (van Zyl Citation2015). In addition, all the protected areas including the Bale Mountain National Park (BMNP), the study area, are being threatened by the de facto open access of resources leading to degradation of habitats, conversion of natural habitat to agricultural lands, overgrazing by large livestock population, weak institutional and financial capacity to manage protected areas, unsustainable natural resource management, invasive species, insecure land tenure system and very low public awareness on the importance of biodiversity and healthy ecosystems to address the impact of climate change (Young Citation2012).

Teressa (Citation2017) indicated that the management, development and utilization policies and practices of protected areas in Ethiopia has been subject to a series of paradigm changes. In line with this, successive Ethiopian governments have been adopting different approaches to address the threats and protect the biodiversity of the BMNP. During the Derg socialist regime (1974–1991), strong ‘protectionist and exclusion management systems’ was applied (Ongugo et al. Citation2007). However, the local communities were not happy with this approach, and they frequently set fire to the park. This was mainly attributed to poor benefit-sharing arrangements and the local communities were not benefiting from the revenue being generated out of their resources which they have been sustaining for several years (Tadesse et al. Citation2011). While most communities viewed protected areas and wildlife positively, the lack of tangible economic benefits limits their support to parks and natural resources management (Tessema et al. Citation2010).

The state ownership of the park has often excluded the involvement of local communities and worsened the lack of clarity over their rights to receive benefits generated from the park (Jambiya et al. Citation2012). Such an approach is in contradiction with an evolving ideology that protected areas cannot survive without the support of communities (Brockington Citation2004) and their support would come through enabling conservation benefits to be distributed at a local level. This, in turn, threatened the survival of the unique and globally significant fauna and flora (BMNP Citation2007). It is increasingly recognized that biodiversity is ultimately lost or conserved at the local level, and it is therefore central that the perception of the local people should be understood, and their interests and priorities should be considered if the management of protected areas and natural resources are to be sustainable (Pratt et al. Citation2004; Yoseph Citation2015). Recognizing the importance of community engagement in protected area management, recently, the Government of Ethiopia is following a strategy of involving rural communities, the private sector and non-governmental organizations in order to increase their management effectiveness and thereby maximize the benefits provided by protected areas to the national economy (van Zyl Citation2015).

However, studies investigating the perception of local communities on park management and existing incentive and benefit-sharing mechanisms in the context of the study area are lacking (e.g. Dewu and Roskaft Citation2018). Also, in the context of the study area, factors influencing the perception of local communities and their participation in decision-making processes related to the management of protected areas are not investigated well. Information on the perception of local communities living in and around protected areas is important to integrate the diversity of management strategies that best suit the protection of biodiversity alongside the development of local community livelihoods into conservation plan (Vimal et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, as a signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), Ethiopia is obligated to implement and fulfill all its responsibilities to protect its biodiversity through sustainable use and fair distribution of benefits derived from genetic resources (IBC Citation2009) where such a study gives a brief on the works being done. Therefore, this study was conducted in the BMNP to (a) assess the perceptions of local communities on the environmental and socio-economic benefits of BMNP, (b) investigate the strength and weaknesses of existing benefit-sharing mechanisms in the perspective of local communities and (c) assess the factors influencing the attitude of local communities towards the BMNP and its management.

Material and methods

Study area

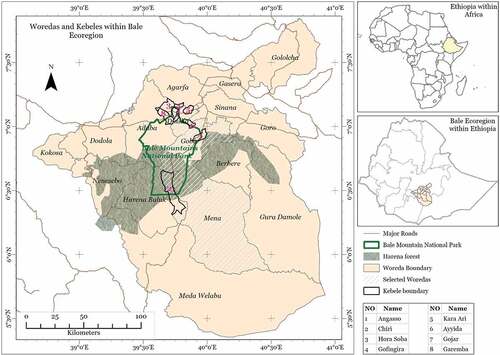

The study was conducted in BMNP, Ethiopia (). The Bale Mountains National Park is one of the biodiversity hotspot areas in Ethiopia and is located at the center of the Bale Eco-region (BER) which covers an area of 2,150 km2 (Watson Citation2013). The elevation of the park ranges from 1,500 to 4,377 m above sea level and possesses the largest afro-alpine area in Africa (Gashaw Citation2015). The BMNP has a global significance due to the rare, endemic and endangered species, which are found across all taxa and habitat types, and the hydrological system which provides water and thus economic benefits to up to 20 million downstream users (Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority Citation2017). Also, other features of the BMNP including the Afroalpine plateau, the Harenna forest, and the distinct altitudinal zones of BMNP have considerable significance to the local, national and global communities.

The BMNP exhibits diverse climatic conditions, with the plateau and its associated mountains characterized by a cool temperature and high rainfall, whereas the lowland part is characterized by a tropical warm, and dry climate. The eastern part of the BMNP possesses a bimodal rainfall and the long rainy season occurs from July to October with the highest peak in August, and the short rainy season occurs from March to June, with peak rainfall in April. The lowland part of the MBNP receive only a short rainy season, which occurs from February to June (BMNP Citation2017). This lower altitude area of the study site receives a mean annual rainfall of 600–1000 mm, whereas the higher altitudinal areas receive 1000–1400 mm of mean annual rainfall (BMNP Citation2007). The daily temperature of the study area displays a huge fluctuation (ranges from −15 to 24°C). The mean annual maximum and minimum temperature is 18.4 and 1.4°C, respectively.

The BMNP has experienced a major influx of migrants since the Citation1990s, largely driven by government changeover in 1991 (Stephens et al. Citation2001), and a combination of pull factors relating to local politics and the perceived availability of land and push factors relating to limited economic opportunities in the migrants’ areas of origin (Wakjira et al. Citation2015). Studies (e.g. Wakjira et al. Citation2015; Reber et al. Citation2018) indicated that human’s settlement and livestock have all been increasing in the BMNP at an alarming rate. It is now estimated that there are over 3,000 households in the park accounting for roughly 20,000 permanent people. The livelihood of these people and the local communities close to the BMNP mainly depends on farming, livestock rearing, and beekeeping (Teshome et al. Citation2018). In the southern parts of the National Park, coffee production is one of the major land use systems with increasing importance in terms of contributing to household livelihoods. Coffee is produced in the form of small-scale gardens and wild coffee production systems.

Such recent changes exposed the BMNP to severe human-induced threats due to agricultural expansion, livestock grazing, and increased settlement within and around its boundaries (Williams et al. Citation2004; Gashaw Citation2015). The rapid population growth, poverty and lack of government commitment to sustainably manage land and water resources, poor law enforcement and poor implementation capacity of government officials are affecting the potential of land and water resources in the park to provide ecosystem services (Endalew et al. Citation2017). Also, this has been putting the region’s unique flora, fauna and water supply for more than 20 million people living downstream areas including the communities in Somalia and Kenya at high risk (Gashaw Citation2015; Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority Citation2017).

As part of the efforts to address these challenges, the park has devised a 10-year (2017–2027) strategic plan to increase the benefits of local communities from the park through carbon credit from REDD+, community ecolodge development and other tourism related benefits and ensure equitable benefit sharing among communities associated with the park (Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority Citation2017). This even becomes more important in the face of expanding settlement within the park (Gashaw Citation2015). These coupled with the weak formal and informal institution and lack of strong commitment to implement the general management plan of the park has increased the degradation of natural resources (Petros et al. Citation2016).

Study design and sampling

The study employed a multi-stage sampling approach (Shimizu Citation2014) to select sample districts, kebeles (i.e. the smallest administrative unit) and households. During the first stage, three districts were selected purposefully from five districts bordering the BMNP. The criteria used to select the three sample districts include population density, the closeness of the districts to the park, the level of interference to the park and accessibility. In the second stage, eight kebeles were selected from the three districts based on their geographical location and direct interaction with the park, and the existence of jointly managed forests and grazing lands. In the third stage, sample households or respondents from each Kebele were selected using Slovin’s formula (EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) ) ().

Table 1. Total household and proportion of sample size in selected kebeles.

where n = Number of samples, N = Total population and e = Error tolerance (95% confidence interval or a margin error of 0.05).

Key informants (n = 9) were selected from the government (e.g. Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority, Agricultural offices, Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, Tourism Development offices) and non-governmental (e.g. Frankfurt Zoological Society) organizations. Knowledge, experience and involvement in the management of the park were some of the criteria used to select key informants. For instance, the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority is legally responsible for managing 14 national parks and protected areas, including the BMNP. The Frankfurt Zoological Society is an international non-governmental organization working on the conservation of wildlife and ecosystems focusing on protected areas and outstanding wild places. The Frankfurt Zoological Society-Ethiopia focuses on the Bale Mountains National Park and supports the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority in park management and working to build collaboration with local authorities to establish more effective protected area law enforcement.

In addition, the study employed focus group discussions to strengthen information obtained through household surveys and key informant interviews. In each selected kebele, three focus group discussions (men, women and youth) were conducted with participants having in-depth knowledge and understanding of the BMNP and its management. Each focus group consisted of five members. During the entire fieldwork, 24 focus group discussions were carried out (i.e. eight kebeles × three focus group discussions per kebele).

Data collection and analysis

The study employed semi-structured questionnaire to collect data from household heads, but either the household head’s wife or another permanently resident adult was interviewed if the former was unavailable and if he/she was not able to provide accurate information about the household. In addition, unstructured and open-ended checklists were used to collect data from key informants and participants of focus group discussions. Using these qualitative and quantitative methods (Spoon Citation2014; Nchanji et al. Citation2017; Sutherland et al. Citation2018), data such as perception of local communities on the benefits and disbenefits of BMNP, co-existence of wildlife and local communities, and on existing shared management mechanisms as well as participation of local communities in the management of the BMNP were gathered. Furthermore, secondary data on benefits of the BMNP (e.g. number and activities of community-based organizations, ecotourism associations, economic benefits from diverse activities such as control hunting, tourist guides, etc.) and existing benefit sharing mechanisms were obtained from the Frankfurt Zoological Society of Ethiopia.

Household survey data on attitudes and perception of local communities on the level of participation in decision-making, awareness of the importance of BMNP for environmental protection and livelihood, and shared management and benefit sharing mechanisms were analyzed with five possible responses or the 5-Point Likert Scale (Preedy Citation2010). This method enables those responders specify their level of agreement to a statement typically in five points: (1) Strongly disagree; (2) Disagree; (3) Neither agree nor disagree; (4) Agree and (5) Strongly agree. Then, calculated weighted average of responses was used to assess the overall perception or attitude of local communities. The internal consistency of the scale was measured by the reliability coefficient, Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach Citation1951).

In addition, the responses obtained on the 5-point Likert scale were used for three inferential statistics, correlation, One-Way ANOVA, and logistic regression analysis. Correlation analysis was conducted to assess the association between independent variables (e.g. economic benefits, participation and communications), and the dependent variable (i.e. perception and attitudes of local communities on existing shared management and benefit-sharing mechanisms). The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate the difference among the participants from the three districts in the perceptions of local community on existing benefit sharing mechanisms. Logistic regressing analysis (significance level of α = 0.05) was conducted to determine which of the socio-economic variables and household characteristics (such as age, gender, education level, landholding size, livestock number and food insecurity) significantly influence the perception and attitude of local communities towards the benefits and management of the BMNP. Descriptive statistics was used to describe the characteristics of households engaged in the study. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 20. The qualitative data gathered using key informant interviews and FGD were analyzed through topic coding and building categories, themes and patterns of relationships (Braun and Clarke Citation2006).

Results

Household characteristics of sample respondents

Most respondents in the study area were from male-headed households (334, 88.4%) and were in the age group of 29–50 years (82.1%) (). Agriculture is the main livelihood mechanism for most respondents (366, 96.6%), while a few (13, 3.4%) engaged in other economic activities such as trade and government-related jobs to support their livelihood. A considerable proportion of the respondents had a small land holding (ranged from 0.25 to 2 ha), herding large number of livestock (6,620 in total) with a mean of 17.5 (ranged from 0 to 45 livestock holding per household). Almost one-third of households (112, 29.6%) did graze their livestock inside the park and communal lands around it, and almost all (373, 98.4%) did not have enough private grazing land to graze their livestock. The results suggested that most (286, 75.5%) did not produce sufficient food from their farms and did not cover their yearly food demand. Only 25.4% of the respondents were food secure, while 74.6% of the respondents were food insecure for three and more than three months. Considering the education level, most of the respondents (149, 39.3%) had no formal education and 150 (39.6%) had a lower level of education ().

Table 2. Household characteristics of sampled respondents.

Perception of local communities on the benefits of Bale Mountains National Park

The results of key informant interviews suggested that BMNP provides both environmental and socio-economic benefits to the local communities. For example, the BMNP provided environmental benefits such as conservation of biodiversity, medicinal plants, forest honey and fuelwood, and supplied clean water and air for large number of communities. According to data obtained from the Frankfurt Zoological Society of Ethiopia, the BMNP was also important in providing economic benefits. For example, the local people get economic benefits by engaging in control hunting, tourist guides, horse renters, porters, cooks, handicrafts, coffee providers, and honey providers. In line with this, about ETB 8,946,645.55 (equivalent to US$ 170,215 based on the exchange rate on 22 September 2022) generated from 2018 to 2021 through 26 community-based organizations engaged in control hunting activities (supplementary material 1). Similarly, ecotourism association engaged in various activities (Supplementary material 2) generated ETB 5,917,696 from 2010 to 2021 (equivalent to US$ 112,587 based on the exchange rate on 22 September 2022).

Survey results indicated that the perception of local communities on the benefits of BMNP varied across benefit types (). Majority of the respondents agreed on the perceived benefit of the BMNP in providing important natural resources for their livelihoods and on the contribution of the BMNP to the conservation of biodiversity (). However, a considerable proportion of the respondents (40%) strongly disagreed and (43%) were undecided/neutral regarding the importance of BMNP to tourist attractions (). Also, only 17% of the respondents agreed on the importance of the BMNP in creating jobs. These perceptions, the disagreement on the importance of BMNP to tourist attractions and job creation, were supported by participants of focus group discussions and key informants. For example, participants of focus group discussions elaborated this as:

The BMNP had great contributions to protecting the environment and maintaining agricultural productivity. However, the BMNP authority was constrained in generating tangible economic benefits for wider communities and the limited benefits are also channeled only through kebele administrations and community-based organizations. The BMNP authority was also constrained in allocating some resources from the revenues to address some crucial problems of local communities such as lack of clean water.

Table 3. The perception of local communities on the benefits, participation, shared management and benefit-sharing mechanism. Figures indicated in the brackets represent percent values.

One of the key informants also elaborated this as:

The awareness of local communities on the importance of BMNP for their livelihood was improving. However, it was still crucial to increase the benefits of local communities from the protected area through job creation and livelihood diversification.

Furthermore, one of the key informants described this as:

The contribution of the BMNP to generate income and improve the livelihood of the local communities was limited to community-based organizations and ecotourism associations engaged in activities such tourist guides and horse renting.

The regression analyses also showed that the perception of households on the benefits of BMNP did not vary with household characteristics such as age, education level, livestock holding and family size. In summary, the results suggested that there are differences between the local communities and the BMNP authority in the perceived benefits of the park. The BMNP authority perceived that the local communities have been gaining income and benefit from the park through different ecotourism activities (Supplementary materials 2). The park authority also explained that the local communities were benefiting from controlled hunting activities organized in three different controlled hunting areas (Supplementary material 1). Some of the key informants and participants of focus group discussions also supported the idea of the BMNP authority in that they revealed the benefits obtained from the park though they mentioned that it was not enough.

Perception of local communities on existing shared management and participation

The data or information obtained from the BMNP authority indicated that there are efforts to implement shared or joint management practices through developing the general management plan using a participatory process involving a review of problems and issues carried out by park authority, a stakeholder workshop and community consultations. The benefit-sharing mechanisms in place were mainly implemented through community-based organization and kebele administration (this mainly works for benefits generated through control hunting activities, Supplementary material 1) and through different ecotourism associations (mainly for benefits generated through various ecotourism activities, Supplementary material 2). The survey results were, however, suggested that most of the respondents were not happy with the existing shared management mechanisms (). For example, more than 50% of the respondents disagreed with the key statements describing the engagement of local communities in managing the park, incentives, and the level of transparency (). In line with this, the analyses of variance revealed that the perception of local communities on existing shared management systems and benefit sharing mechanisms significantly varied among the three studied districts (F(2, 376) = 4.937, P < 0.05). For example, respondents from the Goba district better accept the existing shared management and benefit sharing mechanisms than respondents in Dinsho district.

Almost half of the respondents (47.3%) did not agree on the statement describing that local communities participate in benefit-sharing related decisions (), which seems that the decision-making system in BMNP still follows top-down approach or not inclusive. Also, the majority of respondents (49.1%) did not agree on the statement that the local communities participate when the park management team establishes community-based organizations and ecotourism associations (). However, the degree of agreement on the statement describing that local communities’ participation in developing the management systems of the park was relatively good (52.6%) (). In line with this, one of the key informants elaborated this as:

The park management teams usually encourage the local communities to participate in managing the protected areas through engaging them in environmental education, tree plantation, and outreach programs.

Factors affecting the attitude of local communities towards the Bale Mountains National Park and its management

The analyses based on the Five-point Likert Scale () suggested that lack of communication, short-term economic benefits and meaningful participation as well as unhealthy relationships with BMNP authority were the potential factors negatively affecting local communities’ attitude on the park and its management. In addition, losses in crops, livestock and human lives due to damage caused by wildlife (), negatively affected the perception of local communities on BMNP. The key informants and participants of focus group discussions also supported this and further elaborated that Common warthog (Phacochoerus africanus) was one of the problematic animals causing significant losses of crop. In line with this, one of the participants of the focus group discussions described this as:

We are very much disappointed that the authority of the BMNP did not give attention to the damage caused by wildlife. They only focus on the protection of the park and fining the local communities.

Table 4. Factors affecting the attitude of local communities towards the management of Bale Mountains National Park. Figures indicated in the brackets represent percent values.

Table 5. Agreement of respondents to statements describing costs incurred by local communities due to the presence of BMNP. Figures indicated in the brackets represent percent values.

In addition to the commonly known damage caused by wildlife, local communities incur an additional cost to get fuelwood due to restrictions to use natural resources within the park. This was supported by 86% of respondents and mentioned as one of the most important costs for local communities (). This was also supported by the participants of focus group discussions in that there are strong restrictions to access resources such as fuelwood inside the part, which consequently add costs to local communities. Furthermore, local communities incurred costs to settle in a new place due to the implementation of the new strategies of the park management. This was supported by about 78% of the respondents ().

The correlation analysis also showed that lack of communication, short-term economic benefits and meaningful participation as well as unhealthy relationships between communities and park authority negatively and significantly associated with the attitudes of local communities on the existing shared management and benefit-sharing mechanisms (r = − 0.222, P < 0.05). Results of logistic regression analysis () demonstrated that livestock holding and the number of months being a household food insecure negatively and significantly (p < 0.05) influenced local communities’ perception towards the BMNP.

Table 6. Logistic regression showing the relationship between household characteristics and attitudes towards BMNP and its management.

Discussion

Effects of household and farm characteristics on protected area management

The practice of free grazing inside the park and communal lands around it is one of the causes of the conflict between local communities and BMNP authority. This could arise from the restrictions imposed by the park authority to protect natural resources from degradation (Waweru and Oleleboo Citation2013; Fentaw and Duba Citation2017; Girma et al. Citation2018; Muhammed and Elias Citation2021). In line with this, studies demonstrated that free grazing affects the structure of the forest and wildlife in the park (Piana and Marsden Citation2014; Soofi et al. Citation2018) so that restrictions to access parks usually enforced by authorities. In the BMNP, this has resulted in continuous conflict between the park and the local communities who still believe that they have right over resources inside the park (Mekonen Citation2020).

Managers of parks and protected areas have been increasingly challenged to make resource allocation decisions that balance competing interests and needs of a growing population with a dwindling natural resource base (Lewis Citation1996; Andrade and Rhodes Citation2012). To ensure successful long-term management of public lands, the development of a relationship based on trust and cooperation between the key protected area stakeholders, namely government agencies, private interests and the public, is critical (Weladji and Tchamba Citation2003; Okech Citation2010; Kelboro and Stellmacher Citation2012). The experience in United States, for example, has shown public task force and advisory groups to be valuable in solving conflicts and assisting managers in their protected area planning and decision-making process (Lewis Citation1996). Studies (e.g. Lewis Citation1996; Weladji and Tchamba Citation2003) indicated that negotiation and extending a variety of benefits to local people supported to resolve conflicts arose due to restriction of traditional grazing. According to these studies, the mechanisms to extend benefits to local people include allowing some grazing of domestic animals within designated sections of protected areas during the drought period; allowing local people to cut thatching grass for personal usage on a regulated basis and allowing people to access water sources in the protected area.

The high level of food insecurity in the study area could increase local communities’ dependence on natural resources within the park and will be one of the key challenges for the effective management of the BMNP. Rivera et al. (Citation2002) indicated that food insecurity is one of the social fragmentations, which is the key challenge for the effective management of protected areas. This even be more important in the face of increasing human settlement within the BMNP driven by both pull (e.g. local politics and the perceived availability of land) and push (e.g. limited economic opportunities in the surrounding areas) factors. In addition, increasing population in the areas surrounding the BMNP coupled with limited livelihood diversification mechanisms could expose the park to human induced threats. The population in the areas surrounding the BMNP characterized by some unique features such as higher average household size (7.22, ranging 2–16), which is much higher than the national and regional average of 4.7 and 4.9, respectively (CSA Citation2012). The large household size can be attributed to the practice of polygamy by considerable number of households (113, 26%) (). Also, the large household size in the study area could be attributed to labor demanding agricultural practices that could encourage families to have more kids. Furthermore, the dominance of the younger population in the population structure (41.8%) together with the limited economic opportunities, increasing fragmentation of landholdings and low agricultural productivity in the area suggest that more pressure or human induced threats is expected on the natural resources in the BMNP.

In the context of the study area where there is very limited livelihood diversification mechanisms and off-farm job opportunities, and heavy dependence on natural resources, the lower level of education of people could aggravate their dependence on natural resources (Garekae et al. Citation2017). This could also force the local communities to focus on short-term economic benefits than the long-term environmental benefits of protected areas (e.g. biodiversity conservation) and increase the degradation of natural resource. This, in turn, affect efforts in biodiversity conservation in protected areas due to limited adoption of long-term conservation approaches. In line with this, Milupi et al. (Citation2023) and Orlović‐Lovren and Ružinski (Citation2011) argue that development of quality environmental education programs, tailored to specific needs in protected areas and delivering it using site specific approaches such as an adult education and other social science methodology could help improve the governance of protected areas.

However, it is also worth to mention that local ecological knowledge plays a great role in managing natural resources. For example, a study conducted in Ethiopia (Asmamaw et al. Citation2020) indicated that local communities possess diverse local knowledge which contributes to the better management of natural resources. The review by Brondízio et al. (Citation2021) shows that local ecological knowledge is making significant contributions to managing the health of local and regional ecosystems, to producing knowledge base in diverse values of nature, confronting societal pressures and environmental burdens, and leading and partnering in environmental governance. Carvalho and Frazão-Moreira (Citation2011) demonstrated that local knowledge provides new insights and opportunities for sustainable management of protected areas. This same study further elaborated that local knowledge could be an interesting tool for educational and promotional programs. Similarly, Cebrián-Piqueras et al. (Citation2020) suggested that local ecological knowledge shapes the perceptions of local communities about protected areas, which has implications for informing protected area management and landscape sustainability.

Perception of local communities on benefits, existing shared management and participation

The lack of tangible economic benefits to most of the local communities and disagreement of the local communities on the importance of BMNP to tourist attractions demonstrate that additional efforts need to be exerted to increase the tangible economic benefits and improve local communities’ awareness on the role of protected areas to tourist attractions. In line with this, the World Bank report (World Bank Citation2021) demonstrated that protected area tourism’s is key to stimulated national and local economies, especially in developing countries. Asmamaw and Verma (Citation2013) and Aseres and Sira (Citation2021) indicated that increasing the economic benefits of local communities from the protected areas improves their participation and enhances the protection of protected areas. Similarly, Chevallier and Milburn (Citation2015) and Heslinga et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that protected areas flourish when embedded in a landscape where the welfare of all stakeholders is considered. The success of conservation strategies through protected areas may lie in the ability of managers to reconcile biodiversity conservation goals with social and economic issues and to promote greater compliance of local communities with protected areas’ conservation strategies (Andrade and Rhodes Citation2012; Welteji and Zerihun Citation2018).

In addition, the lack of tangible economic benefits shows that the existing park management approach in the BMNP might not fully support to achieve the objective of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which aims to conserve biodiversity, sustainably use its components, and enable fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of biodiversity (CBD Citation2011). In line with this, Htay et al. (Citation2022) argues that a collaborative conservation and sharing more benefits with local communities are important when developing future protected areas management strategies.

However, the better agreement of local communities with the importance of BMNP to environmental conservation and associated benefits (e.g. beekeeping, better water supply, and air quality) could help improve local communities’ participation in park management. A relatively better understanding of the link between park management and environmental conservation and associated benefits could be attributed to the environmental education offered to the local communities by the authorities of the park (Ardoin et al. Citation2020). Rivera et al. (Citation2002) elaborated that ecological knowledge is key to the further advancement of initiatives designed to increase the biodiversity of agricultural landscapes within protected areas.

Disagreement between local communities and BMNP authority on contributions of the park to income generation and job creation could arise from the uneven distribution of benefits among the studied districts. For example, from districts included in this study, controlled hunting is practiced in one district (i.e. Dinsho district) and only two out of the 26 community-based organizations reside in this district. This could have a contribution to the discrepancy between local communities’ perceptions and park authority. This, in turn, suggests the importance of expanding the establishment of community-based organizations and ecotourism association and thereby improving local communities access to generated benefits.

The unsatisfaction of most of the local communities on existing shared management mechanisms could be attributed to the fact that the general management plan, designed for 2017–2027 is not fully implemented and its fruits were not realized. Also, the limited tangible or short-term economic benefits (Rivera et al. Citation2002; Locke and Dearden Citation2005), restrictions to the use of natural resources (Mombeshora and Le Bel Citation2009; Poudel Citation2019; Bansard and Schroder Citation2021), and conflicts arises from loss of crops and livestock due to damage by wild animals (Pandey and Bajracharya Citation2015; Can-Hernández et al. Citation2019; Mekonen Citation2020) could contribute to the dissatisfaction of local communities.

The spatial variability of the level of satisfaction of local communities on existing shared management, incentives, and benefit sharing mechanisms could be attributed to the difference in the level of dependence of local communities on park resources for their livelihood. For example, communities in Dinsho district are highly dependent on the resources from the park either for grazing, or fuelwood collection and they are the one affecting the park due to their illegal settlement and agricultural expansions. Therefore, the probability of developing a significant positive perception on existing shared management might be rare in this community. In summary, to build trust and improve a positive attitude of local communities towards the park and its management, a clearer, more holistic and inclusive approach to benefit sharing mechanisms needs to be implemented.

The lack of inclusiveness in decision making processes might negatively affect the sustainable conservation of biodiversity of the park as lack of control on the decision-making process may hinder their ability and willingness to support the future conservation of the park (Umuziranenge and Muhurwa Citation2017). Improving the participation of local communities is key to sustain the benefits from the park, as the participation of local communities helps to ensure the sustainable management of natural resources within the park (Iori Citation2012). It is a fact that taking part actively in protected area management and decision-making processes is a proper way of including the local communities in protected area management and this helps in developing positive attitudes and perceptions towards protected area management. Participation of local communities in protected area management is a good approach that would not only minimize the cost of management and conservation but also helps in changing the attitudes and perceptions of the local people towards protected areas, wildlife, and tourism (He et al. Citation2020). The general management plan of the BMNP (Citation2017 − 2027) also recognized the importance of meaningful participation in park management and was designed following a participatory approach. This could be seen as a good first step to improve the management of the park and enhance local communities access to derived benefits.

Factors affecting the attitude of local communities

The results suggest that improving communication between local communities and BMNP authority and short-term economic benefits are key to address the existing challenges. Interestingly, the BMNP authority did not agree that the lack of short-term economic benefits can be one of the reasons contributing to the development of negative attitudes among local communities but admitted that the benefits reached to the local communities might not be enough due to the limited capacity of the park in generating economic benefits and existing benefit sharing mechanisms (e.g. benefits are shared through kebeles and community level organization instead of direct appropriation to local communities). Studies (e.g. Iori Citation2012; Heslinga et al. Citation2019) indicated that issues related to economic benefits and benefit-sharing are usually sensitive and affect the relationship between stakeholders managing protected areas.

Damage to crops and livestock caused by wildlife might have exacerbated the negative attitude of communities towards the park. Frequent negative interactions with wildlife can lead community to resent on park and the animals that live within it (Marquardt et al. Citation1994; Can-Hernández et al. Citation2019), but a positive attitude can be developed through participation in conservation activities and inclusion in fair and equitable benefit sharing (Kolinski and Milich Citation2021). More importantly, attitudes and behaviors towards conservation area can change when interventions that address the needs of a community are implemented (Travers et al. Citation2019). The negative association of relocation and associated costs with the management of the BMNP could arise from the lack of meaningful participation of local communities when developing the long-term strategic plan. In line with this, Mamo (Citation2015) indicated that relocation of the local communities has negatively affected the relationship between the park authority and the communities because it had been done involuntarily. In contrary to this, a study in Uganda demonstrated that local communities could develop more positive attitude provided that the park management involves dialogue, conflict resolution mechanisms, education and mechanisms to increasing community resource access (Kazoora Citation2003).

The negative influence of livestock holding and the level of food insecurity on the perception of local communities could be because, those households having large number of livestock would like to graze within the park, which is not consistent with the existing management system. This, in turn contributes to developing a negative attitude towards the park and its management. The food insecurity of a household increases its dependence on natural resources and interference with the park, which could result in conflict between local communities and the authorities of the park. This, in turn, contributes to the development of negative attitudes on households that are food insecure. In summary, the results suggest that more efforts are needed to build positive attitude among communities through increasing access to tangible economic benefits, ensuring meaningful participation and building trust.

Implications for future planning and management of protected areas

The BMNP are exposed to severe human-induced threats due to complex and interlinked direct and indirect drivers. Therefore, addressing these requires focusing on the underlying causes rather than on the effects, symptoms and impacts. For instance, the provision of environmental education and engaging the local communities in tree planting are not the ultimate solution for addressing human-induced threats, but efforts must, also, be directed towards improving the tangible economic benefits to local communities. We found that park and government authorities use their power to decide how local communities should participate in BMNP management initiatives. Such a top-down approach affects the sustainability of the efforts to conserve protected areas because local stakeholders lack incentives to participate. This also leads to inadequate understanding of the complex interactions between people and protected areas they depend on, and the inability to tailor management responses to specific needs and conditions (Dewu and Roskaft Citation2018).

The results obtained through the analysis of the factors affecting the attitude of local communities toward the parks and its management demonstrated that efforts should be concentrated on improving communication with local communities, short-term economic benefits, and identifying the reasons for the unhealthy relationships and addressing them. These issues can partly be addressed through, for example, creating and supporting effective and functioning multi-stakeholder platforms for dialogue and co-production of knowledge, continues meetings and awareness-raising campaigns and integrating more income generating activities as also suggested for example by Dewu and Roskaft (Citation2018). Effective stakeholder engagement in complex resource management systems, as is the case in the BMNP and many east African countries, is thus needed to ensure the successful implementation of the long-term strategic plans. Inclusive decision-making is key to the sustainability of management plan designed for protected areas (Dewu and Roskaft Citation2018). In addition, giving more emphasis to local drivers of change when analyzing the context and setting issues for managing protected areas is crucial (e.g. Dewu and Roskaft Citation2018). Furthermore, the identification of actions should be embedded in an understanding of the broader governance system affecting protected areas management, linked to a range of governance attributes, including but not limited to participation.

Conclusions

Planning of management of protected areas requires a better understanding of the underlying causes for the existing park-people interactions and conflict. Our analyses of the collected data suggest that the ‘park-people interaction and conflict’ in the BMNP mainly arises from the dominance of free grazing system in livestock management practices, restriction on the use of resources inside the protected areas, food insecurity and high level of local communities dependence on natura resources, inadequate contribution of the park to income generation and job creation, limited access of communities to generated economic benefits, crop and livestock damages caused by wildlife, and relocation of communities after limited consultation. Therefore, improving livestock farming system with higher productive animals and shifting free grazing to cut and carry system through improved livestock feed development within the park; improving agricultural productivity and food security through introducing improved crop and land management; establishing a good communication and explaining the BMNP goals, intensions and interests through organizing multi-stakeholder platforms; minimizing dependency on forest to the vulnerable people through skill-based training programs and integrating income generating activities within the park while maintaining the ecosystem and ecosystem services; enhancing local communities access to generated benefits through developing infrastructures such as water points; and introducing buffer zone management to reduce crop and livestock damage by wildlife will help to reduce the existing conflict between park authority and local communities in the BMNP.

To support the efforts of the BMNP authority in addressing the causes of the ‘park-people conflict’, we suggest that future research for development initiatives should focus on:

Finding ways of integrating initiatives designed for protected area management with livelihood diversification, following a systems approach when evaluating long-term strategic plans and investigating options for addressing the underlying causes of human-induced threat on protected areas.

Exploring ways of ensuring active involvement of all stakeholders at all levels of protected area management, avoiding the focus on associations or groups who are directly benefiting from the protected areas.

Exploring ways of addressing the additional costs incurred by local communities due to the restriction of using natural resources within the park.

Investigating the challenges and opportunities of the use of platforms and continuous meetings and awareness-raising campaigns and assess ways of incorporating multiple interests and agency in dialogues on the management of protected area to build trust in planning and implementation of long-term strategic plans designed to sustainably manage protected areas.

Investigating mechanisms for improving park-community interaction to build a healthy relationship and build sense of ownership among local communities.

Further similar studies are required to strengthen and refine the key suggested recommendations, as the findings of this study were based on only data collected from three districts surrounding the Bale Mountain National Park.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [Endaylallu Gulte] and [Wolde Mekuria] all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics and consent

Household survey, key informant interviews and focus group discussions data presented in this study were collected as part of research activities conducted based on the International Water Management Institute (IWMI’s) Research Ethics Policy and the CGIAR Research Ethics Code and Responsible Data Guidelines. Participants were informed of the nature and purpose of research activities through a verbal statement in local language and, if they were willing to participate, they were asked to give verbal consent.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (720.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the EU funded SHARE II project for providing financial support. We are also very thankful for Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) of Ethiopia for providing secondary data on benefits of the Bale Mountains National Park and benefit sharing mechanisms. Furthermore, we are grateful for the local communities for their support during field work. We are thankful to Mulugeta Tadesse for preparing the study area map.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2023.2227282

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrade GSM, Rhodes JR. 2012. Protected areas and local communities: an inevitable partnership toward successful conservation strategies? Ecol Soc. 17(4):14. doi: 10.5751/ES-05216-170414.

- Ardoin NM, Bowers AW, Gaillard E. 2020. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: a systematic review. Biol Conserv. 241:108224. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224.

- Aseres SA, Sira RK. 2021. Ecotourism development in Ethiopia: costs and benefits for protected area conservation. J Ecotourism. 20(3):224–16. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2020.1857390.

- Asmamaw D, Verma A. 2013. Ecotourism for environmental conservation and community livelihoods, the case of the Bale Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. J Environ Sci Water Resour. 2(8):250–259.

- Asmamaw M, Mereta ST, Ambelu A, Bhadauria T. 2020. The role of local knowledge in enhancing the resilience of dinki watershed social-ecological system, central highlands of Ethiopia. PLoS One. 15(9):e0238460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238460.

- Ayivor JS, Gordon C, Tobin GA, Ntiamoa-Baidu Y. 2020. Evaluation of management effectiveness of protected areas in the Volta Basin, Ghana: perspectives on the methodology for evaluation, protected area financing and community participation. J Environ Pol Plan. 22(2):239–255. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2019.1705153.

- Bansard J, Schroder M. 2021. The sustainable use of natural resources: the governance challenge. Manitoba (Canada): International Institute for Sustainable Development.

- Benetti S, Langemeyer J. 2021. Ecosystem services and justice of protected areas: the case of Circeo National Park, Italy. Ecosyst People. 17(1):411–431. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2021.1946155.

- Bermejo LA, Lobillo JR, Molina C. 2020. People and nature conservation: participatory praxis in the planning and management of natural protected areas. In: Baldauf C, editor. Participatory Biodiversity Conservation. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-41686-7_9.

- BMNP. 2007. Bale mountains national park: general management plan 2007-2017. BMNP with frankfurt zoological society, Ethiopia. Manage Plan. 176(20):19–20.

- BMNP. 2017. Bale Mountains National Park general management plan (2017- 2027). Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101.

- Brockington D. 2004. Community conservation, inequality, and injustice: myths of power on protected area management. Conserv Soc. 2(2):412–432.

- Brondízio ES, Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y, Bates P, Carino J, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Ferrari MF, Shrestha UB, Reyes-García V, McElwee P, Molnár Z, Samakov A. 2021. Locally based, regionally manifested, and globally relevant: indigenous and local knowledge, values, and practices for nature. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 46(1):481–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-012127.

- Can-Hernández G, Villanueva-García C, Gordillo-Chávez EJ, Pacheco-Figueroa CJ, Pérez-Netzahual E, García-Morales R. 2019. Wildlife damage to crops adjacent to a protected area in Southeastern Mexico: farmers’ perceptions versus actual impact. Hum–Wildl Interact. 13(3):11.

- Carvalho AM, Frazão-Moreira A. 2011. Importance of local knowledge in plant resources management and conservation in two protected areas from Trás-os-Montes, Portugal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-7-36.

- CBD. 2011. Strategic plan for biodiversity 2011–2020 and the Aichi targets “Living in Harmony with Nature”. Canada: Secretariat of the convention on biological diversity World Trade Centre.

- Cebrián-Piqueras MA, Filyushkina A, Johnson DN, Lo VB, López-Rodríguez MD, March H, Plieninger T, Peppler-Lisbach C, Quintas-Soriano C, Raymond CM, Ruiz-Mallén I. 2020. Scientific and local ecological knowledge, shaping perceptions towards protected areas and related ecosystem services. Landscape Ecol. 35(11):2549–2567. doi: 10.1007/s10980-020-01107-4.

- Chevallier R, Milburn R 2015. Increasing the economic value and contribution of protected areas in Africa.

- Cronbach LJ. 1951. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 16(3):297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555.

- CSA. 2012. Population projections for Ethiopia, 2007-2037. Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Agency.

- Dewu S, Roskaft E. 2018. Community attitudes towards protected areas: insights from Ghana. Oryx. 5(3):489–496. doi: 10.1017/S0030605316001101.

- Endalew M, Lemma T, Gonfa K 2017. Policy gaps towards implementation of participatory forest management: the case of Bale eco-region. Technical report. 04. See publication at: www.researchgate.net/publication/320226626.

- Estifanos TK, Polyakov M, Pandit R, Hailu A, Burton M. 2020. The impact of protected areas on the rural households’ incomes in Ethiopia. Land Use Policy. 91:104349. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104349.

- Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority. 2017. Bale Mountains National Park, general management plan 2017 – 2027. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority.

- Fentaw T, Duba J. 2017. Human–wildlife conflict among the pastoral communities of southern rangelands of Ethiopia: the case of Yabello protected area. J Int Wildl Law Policy. 20(2):198–206. doi: 10.1080/13880292.2017.1346352.

- Garekae H, Thakadu OT, Lepetu J. 2017. Socio-economic factors influencing household forest dependency in Chobe enclave, Botswana. Ecol Process. 6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13717-017-0107-3.

- Gashaw T. 2015. Threats of Bale Mountains National Park and solutions: Ethiopia. J Phys Sci And Environ Stud. 1(2):10–16.

- Girma Z, Chuyong G, Mamo Y. 2018. Impact of livestock encroachments and tree removal on populations of mountain nyala and Menelik’s bushbuck in Arsi mountains national Park, Ethiopia. Int J Ecol. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2018/5193460.

- He S, Yang L, Min Q. 2020. Community participation in nature conservation: the Chinese experience and its implication to national park management. Sustainability. 12(11):4760. doi: 10.3390/su12114760.

- Heslinga J, Groote P, vanclay F. 2019. Strengthening governance processes to improve benefit-sharing from tourism in protected areas by using stakeholder analysis. J Sustain Tour. 27(6):773–787. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1408635.

- Hoffmann S. 2022. Challenges and opportunities of area-based conservation in reaching biodiversity and sustainability goals. Biodivers Conserv. 31(2):325–352. doi: 10.1007/s10531-021-02340-2.

- Htay T, Htoo KK, Mbise FP, Røskaft E. 2022. Factors influencing communities’ attitudes and participation in protected area conservation: a case study from Northern Myanmar. Soc Nat. 35(3):301–319. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2022.2032515.

- IBC (Institute of Biodiversity Conservation) 2009. Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Ethiopia’s 4th country report. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa.

- Iori GF 2012. Analysis of the current status of the simien mountains in Ethiopia: managing the paradox between community-based tourism, nature conservation and national parks [ Doctoral dissertation]. NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences.

- IPBES. 2019. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. In: Brondizio ES, Settele J, Díaz S, and Ngo HT, editors. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat. p. 1148. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3831673.

- Jambiya GR, Shemdoe R, Tukai DK, Dokken T 2012. The context of REDD+ in Tanzania: drivers, agents, and institutions [ Unpublished project document].

- Kazoora C. 2003. Conflict resolution in the namanve peri-urban reforestation project in Uganda. Nat Res Conflict Manage Case Stud: Anal Power, Participation Protected Areas. 39:39–58.

- Kelboro G, Stellmacher T 2012. Contesting the national park theorem? Governance and land use in nech sar national park, Ethiopia (No. 104). ZEF Working Paper Series.

- Kolinski L, Milich KM. 2021. Human-wildlife conflict mitigation impacts community perceptions around kibale national park, Uganda. Diversity. 13(4):145. doi: 10.3390/d13040145.

- Lewis C. 1996. Managing conflicts in protected areas. Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK: IUCN; p. xii + 100.

- Locke H, Dearden P. 2005. Rethinking protected area categories and the new paradigm. Environ Conserv. 32(1):1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0376892905001852.

- Mamo Y. 2015. Attitudes and perceptions of the local people towards benefits and conflicts they get from conservation of the Bale Mountains National Park and Mountain Nyala (Tragelaphus buxtoni), Ethiopia. Int J Biodivers Conserv. 7(1):28–40.

- Marquardt M, Infield M, Namara A. 1994. Socio-economic survey of communities in the buffer zone of lake mburo national park. Lake mburo community conservation project. Kampala. Monbiot: Uganda National Parks.

- Maxwell SL, Cazalis V, Dudley N, Hoffmann M, Rodrigues AS, Stolton S, Watson JE, Woodley S, Kingston N, Lewis E. 2020. Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature. 586(7828):217–227. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2773-z.

- Mekonen S. 2020. Coexistence between human and wildlife: the nature, causes and mitigations of human wildlife conflict around Bale Mountains National Park, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Ecol. 20(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12898-020-00319-1.

- Milupi DI, Mweemba L, Mubita K 2023. Environmental education and community-based natural resource management in Zambia.

- Mombeshora S, Le Bel S. 2009. Parks-people conflicts: the case of Gonarezhou National Park and the Chitsa community in south-east Zimbabwe. Biodivers Conserv. 18(10):2601–2623. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9676-5.

- Muhammed A, Elias E. 2021. Class and landscape level habitat fragmentation analysis in the Bale mountains national park, southeastern Ethiopia. Heliyon. 7(7):e07642. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07642.

- Nchanji YK, Levang P, Jalonen R. 2017. Learning to select and apply qualitative and participatory methods in natural resource management research: self-critical assessment of research in Cameroon. For Trees Livelihoods. 26(1):47–64. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2016.1246980.

- Okech RN. 2010. Wildlife-community conflicts in conservation areas in Kenya. Afr J Conflict Resolut. 10(2). doi: 10.4314/ajcr.v10i2.63311.

- Ongugo P, Njguguna J, Obonyo E, Sigu G 2007. Livelihoods, Natural Resource Entitlements and Protected Areas: the case of Mount Elgon Forest in Kenya. Kenya IFRI Collaborative Research centre. [accessed 2020 Oct 20]. http://www.cbd.int/doc/case-studies/for/cs-ecofor-ke-02-en.pdf.

- Orlović‐Lovren V, Ružinski N. 2011. The role of education in protected area sustainable governance. Manag Environ Qual: Int J. 22(1):48–58. doi: 10.1108/14777831111098471.

- Palomo I, Montes C, Martin-Lopez B, González JA, Garcia-Llorente M, Alcorlo P, Mora MRG. 2014. Incorporating the social–ecological approach in protected areas in the Anthropocene. BioSci. 64(3):181–191. doi: 10.1093/biosci/bit033.

- Pandey S, Bajracharya SB. 2015. Crop protection and its effectiveness against wildlife: a case study of two villages of Shivapuri National Park, Nepal. Nepal J Sci Technol. 16(1):1–10. doi: 10.3126/njst.v16i1.14352.

- Petros I, Abie K, Esubalew B. 2016. Threats, opportunities and community perception of biological resource conservation in Bale Mountains National Park, a case of Dinsho district, Ethiopia. Int Res J Biol Sci. 5(4):6–13.

- Piana RP, Marsden SJ. 2014. Impacts of cattle grazing on forest structure and raptor distribution within a neotropical protected area. Biodivers Conserv. 23(3):559–572. doi: 10.1007/s10531-013-0616-z.

- Poudel HK. 2019. Park people conflict management and its control measures in Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Int J Food Sci Agric. 3(3):179–182. doi: 10.26855/ijfsa.2019.09.005.

- Pratt DG, MacMillan DC, Gordon IJ. 2004. Local community attitudes to wildlife utilisation in the changing economic and social context of Mongolia. Biodivers Conserv. 13(3):591–613. doi: 10.1023/B:BIOC.0000009492.56373.cc.

- Preedy VR. 2010. Handbook of disease burdens and quality of life measures. R. R. Watson, editors. Vol. 4, New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78665-0.

- Reber D, Fekadu M, Detsch F, Vogelsang R, Bekele T, Nauss T, Miehe G. 2018. High-altitude rock shelters and settlements in an African alpine ecosystem: the Bale Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. Hum Ecol. 46(4):587–600. doi: 10.1007/s10745-018-9999-5.

- Rivera VS, Cordero PM, Cruz IA, Borras MF. 2002. The Mesoamerican biological corridor and local participation. Parks. 12(2):42–54.

- Shimizu I. 2014. Multistage sampling. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. doi: 10.1002/9781118445112.stat05705.

- Soofi M, Ghoddousi A, Zeppenfeld T, Shokri S, Soufi M, Jafari A, Waltert M, Qashqaei AT, Egli L, Ghadirian T. 2018. Livestock grazing in protected areas and its effects on large mammals in the Hyrcanian forest, Iran. Biol Conserv. 217:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.11.020.

- Spoon J. 2014. Quantitative, qualitative, and collaborative methods: approaching indigenous ecological knowledge heterogeneity. Ecol Soc. 19(3). doi: 10.5751/ES-06549-190333.

- Stephens PA, d’Sa CA, Sillero-Zubiri C, Leader-Williams N. 2001. Impact of livestock and settlement on the large mammalian wildlife of Bale Mountains National Park, southern Ethiopia. Biol Conserv. 100(3):307–322. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00035-0.

- Sutherland WJ, Dicks LV, Everard M, Geneletti D. 2018. Qualitative methods for ecologists and conservation scientists. Methods Ecol Evol. 9(1):7–9. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12956.

- Tadesse D, Williams T, Irwin B. 2011. People in national parks – joint natural resource management in Bale Mountains National Park – why it makes sense to work with local people. J Ethiopian Wildl Nat Hist Soc Walia-Special Ed Bale Mountains. 257–268.

- Tefera M. 2011. Wildlife in Ethiopia: endemic large mammals. World J Zool. 6(2):108–116.

- Teressa DK. 2017. Ethiopia: changes from “people out approach” protected area management to participatory protected area management? Insight from Ethiopian protected areas. J Environ Sci, Toxicol Food Technol. 11(2):49–55. doi: 10.9790/2402-1102014955.

- Teshome Y, Urgessa K, Kinahan AA, Belay H, Assefa S. 2018. An assessment of local community livelihood benefits as a result of Bale Mountains National Park, Southeast Ethiopia. Int J Environ Sci Nat Resour. 15(5):133–140. doi: 10.19080/IJESNR.2018.15.555922.

- Tessema ME, Lilieholm RJ, Ashenafi ZT, Leader-Williams N. 2010. Community attitudes toward wildlife and protected areas in Ethiopia. Soc Nat. 23(6):489–506. doi: 10.1080/08941920903177867.

- Travers H, Archer LJ, Mwedde G, Roe D, Baker J, Plumptre AJ, Rwetsiba A, Milner-Gulland EJ. 2019. Understanding complex drivers of wildlife crime to design effective conservation interventions. Conserv Biol. 33(6):1296–1306. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13330.

- Umuziranenge G, Muhurwa F. 2017. Ecotourism as potential conservation incentive and its impact on community development around Nyungwe National Park (NNP): rwanda. Imperial J Interdiscip Res. 3(10):2454–1362.

- van Zyl H 2015. The economic value and potential of protected areas in Ethiopia. report for the Ethiopian wildlife conservation authority under the sustainable development of the protected areas system of Ethiopia programme (independent economic researchers, cape town, South Africa).

- Vimal R, Navarro LM, Jones Y, Wolf F, Le Moguédec G, Réjou-Méchain M. 2021. The global distribution of protected areas management strategies and their complementarity for biodiversity conservation. Biol Conserv. 256:109014. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109014.

- Wakjira DT, d’Udine F, Crawford A 2015. Migration and conservation in the Bale Mountains Ecosystem. IISD report. 111 Lombard Avenue, Suite 325 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

- Watson C 2013. Forest conservation for communities and carbon: the economics of community forest management in the Bale Mountains Eco-Region, Ethiopia [ Doctoral dissertation]. The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE)).

- Watson JE, Dudley N, Segan DB, Hockings M. 2014. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature. 515(7525):67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature13947.

- Waweru FK, Oleleboo WL. 2013. Human-wildlife conflicts: the case of livestock grazing inside Tsavo West National Park, Kenya. Res Humanit Sociual Sci. 3(19):60–67.

- Weladji RB, Tchamba MN. 2003. Conflict between people and protected areas within the Bénoué Wildlife Conservation Area, North Cameroon. Oryx. 37(1):72–79. doi: 10.1017/S0030605303000140.

- Welteji D, Zerihun B. 2018. Tourism–agriculture nexuses: practices, challenges, and opportunities in the case of Bale Mountains National Park, Southeastern Ethiopia. Agric Food Secur. 7(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s40066-018-0156-6.

- Williams S, Vivero JL, Spawls S, Anteneh S, Ensermu K. 2004. Ethiopian Highlands. In: Mittermeier RA, Robles-Gil P, Hoffmann M, Pilgrim JD, Brooks TM, Mittermeier CG , and Fonseca G, editors. Hotspots revisited: earth´s biologically eichest and most endangered ecoregions. Mexico: CEMEX; p. 262–273.

- Woodhouse E, Bedelian C, Dawson N, Barnes P. 2018. Social impacts of protected areas: exploring evidence of trade-offs and synergies. In: Schreckenberg K, Mace G, Poudyal M, editors. Ecosystem Services and Poverty Alleviation. Routledge. p. 222–240.

- World Bank. 2021. Banking on protected areas: promoting sustainable protected area tourism to benefit local economies. Washington: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35737License:CCBY3.0IGO.

- Yoseph M. 2015. Attitudes and perceptions of the local people towards benefits and conflicts they get from conservation of the Bale Mountains National Park and Mountain Nyala (Tragelaphus buxtoni), Ethiopia. Int J Biodivers Conserv. 7(1):28–40. doi: 10.5897/IJBC2014.0792.

- Young J 2012. Ethiopian Protected Areas, a ‘Snapshot’, March 2012; a reference guide for future strategic planning and project funding [Case]. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa.