ABSTRACT

Resilience has become increasingly popular in sustainability research and practice as a way to describe change. Within this discourse, the notion of resilience as the capacity of people, practices and processes, to persist, adapt or transform is particularly salient. The ability to bounce back from shock (persistence) or to take adaptive measures to cope with change are most commonly attributed to resilience, but at the same time, there is a strong push for a transformation agenda from various social and environmental movements. How capacities for resilience are enacted and performed through social practices remains relatively underexplored and there is potential for more dialogue and learning across disciplinary traditions. In this article, we outline the ‘Resilience Capacities Framework’ as a way to a) explicitly address questions of agency in how resilience capacities are enacted and b) account for the dynamic interactions between pathways of persistence, adaptation and transformation. Our starting point is to conceptualise future pathways as co-evolved, whereby social and ecological relationships are shaped through processes of selection, variation and retention, enacted in everyday practices. Drawing on theories of bricolage and structuration, we elaborate on the role of actors as bricoleurs, consciously and non-consciously shaping socio-ecological relationships and pathways of change. Informed by cases of rural change from mountain areas, we explore the extent to which an approach focusing on agency and bricolage can illuminate how the enactment of resilience capacities shapes intersecting pathways of change.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

Rashtak, a red winter wheat variety, sways in the wind at 2,400 m in the Pamir Mountains of Central Asia, where the cold is biting and the soils are bare. Rashtak has been selected over millennia, for its sweet and nutty taste, and its hardiness to frost and poor soils at high altitudes. Special among the 151 wheat varieties domesticated in the Pamirs, Rashtak is celebrated during the Persian New Year when it is made into Baht, a festive porridge. In the 1990s, a development intervention introduced ‘higher-yielding’ F1-hybrid varieties of wheat to improve production. Production increased in the first year, but declined in the following years due to lack of agro-chemical inputs, and eventually wheat cultivation was abandoned completely in some valleys. Rashtak, along with other traditional landrace varieties, was nearly lost. One remote community saved Rashtak over the years, and communities from far and wide received the red flour to make Baht at Nawruz. In recent years, this community has been supported by development aid in the formation of a ‘Village Technology Group’, whose main mandate is to manage the traditional seed variety and to further experiment with conserving and enriching biological and cultural diversity.

Moving halfway across the world to another mountain range, to the Austrian Alps, Monika and Josef (Sepp) RieserFootnote1 remain one of the few farming families in the Gastein Valley who milk their dairy cows and process all the milk high up at the summer pasture at Präau Hochalm. Alm is a managed Alpine grazing area; Hoch denotes the ‘high’ summer pasture as opposed to pastures closer to the valley. This land has been farmed for over 1000 years, and the Rieser Family has been managing this part of the mountain for 400 years, and the current Alm Hütte (Pasture hut) at 1808 m in use today is 150 years old. Austria has the highest percentage share of utilized agricultural area in Europe, at over 26.5% (Eurostat Citation2020). In total, 92.7% are family farms (Niedermayr et al. Citation2015), but these numbers are declining. Family farming, food sovereignty and agroecological and organic farming practices are widely seen as important strategies for food system resilience. It is interesting, therefore, to think about how family farms succeed – what practices do they maintain and what others change? Präa SeppFootnote2 describes a situation in which he changed a key farming practice in order to maintain a lifestyle which makes sense to him and his family and their landscape.

A few years ago, we suddenly had a lot of snow here on the Alm in August. The dairy cows hadn’t finished their 60 days at the summer pasture (necessary for subsidies), so I had to bring them down to the pastures around the hunter’s hut to graze (about 2 km down the mountain) and back up to the Alm two times a day to be milked. Four times, up and down. This didn’t make sense.

I recalled a conversation with a guest from New Zealand a few years ago. He asked me how often we milk the cows, and I replied, ‘twice a day, obviously!’ The New Zealander replied: ‘What do you mean, obviously? We only milk once a day’. This sounded crazy – everyone milks their cows twice a day here. But I filed this idea away in the drawer of ideas I have in my mind. When I hear something interesting, and if it makes sense, I put it in that drawer in my head, until it might be useful. I have a lot of time to think, in my work, which involves a lot of physical work. I ran through different scenarios, and carefully considered all the risks. Then that day in August in 2018, when it snowed at the summer pasture, I decided to try it out.

I simply didn’t bring the animals up in the evening to be milked. Since the cows had had a tough summer, when they returned to the home pastures around the farm, I continued to only milk them once a day, to give them time to recover. After 1.5 months, I could see that this worked, and we stuck with it.

Our cows produce a bit less milk, but it’s enough. It’s enough to have a good life. And the cows are not disadvantaged, they also have a bit more for themselves. More time to graze, more time on the pastures. Now, I have more time for other farm activities, which easily makes up for slightly lower milk quantity, but importantly also time for myself. And, we still produce a high-quality food product.

Adapting to milking only once a day enabled the Riesers to continue their extensive and transhumant way of farming, avoiding the intensification strategy that most of the other farms in the valley have taken on. In changing the daily milking practice, Sepp broke a tradition in order to maintain a way of life, an identity, that is considered traditional: processing of Alm milk on the summer pasture.

These vignettesFootnote3 illustrate in different ways how every-day practices define pathways of resilience, as the capacity to deal with change, through persistence, adaptation or transformation. The first vignette addresses collective agency and the latter individual agency. Farmers are continuously (re)inventing their daily practices in order to (re)create relationships that enable their farming resilience over time (Darnhofer Citation2021). Some valued practices persist (making cheese at summer pastures), while others adapt to changing circumstances (only milking once a day). Other new practices are enacted in order to fundamentally reconfigure relationships while maintaining the core identity of what it means to be a farmer. Both the elements of ‘doings’ and ‘sayings’ (see also Practice Theory, for example Kemmis et al. Citation2013) in everyday practices are crucial to understanding how farmers experience and adapt to change. Together, these dynamics of persistence, adaptation and transformation, played out in practices, and sometimes through institutions, are resilience capacities. But what these capacities are, who has them, and how they are enacted remains a major research gap. In this paper, we present the Resilience Capacities Framework, incorporating theories of bricolage and agency (structuration theory), in order to advance thinking about how capacities are enacted, enabled and constrained in contexts of uncertainty. The notion of bricolage is invoked to describe processes of experimentation and cobbling together of social practices in order to create something new (Cleaver Citation2012). Bricolage arrangements are not just pragmatic adaptations but are invested with meanings and authority. The purpose of presenting this framework is to open up the space to explicitly consider a) the role of agency in resilience capacities, and b) understanding future pathways as interacting dynamics of persisting, adapting and transforming.

1.1. Conceptualisations of resilience

Resilience has become a popular term over the past decade within research, policy and practice to address complex challenges such as disaster risks, food insecurity and climate change impacts in the context of implementing the global sustainable development agenda (Reyers et al. Citation2022). Resilience definitions and approaches abound (1) as a non-normative measure (Anderies et al. Citation2013; Quinlan et al. Citation2016), (2) as a normative approach to guide change processes (Redman Citation2014), (3) as a process (Darnhofer et al. Citation2016; Darnhofer Citation2021) and (4) as a capacity (Béné et al. Citation2015; Brown Citation2015; Folke et al. Citation2016). We focus on the latter two: resilience as a process and capacity of responding to change, and we situate ourselves within the social-ecological systems tradition of resilience-thinking, which assumes that 1) social and ecological dynamics are deeply intertwined, and 2) interact across scales, 3) through a process of coevolution (Haider et al. Citation2021). A co-evolutionary framing of resilience (Haider et al. Citation2021) laid out a structural macro foundation of how these different capacities emerge, but does not enable a micro-agency aspect of the emergence and interactions of different pathways and how they are performed. Agency perspectives have been prominent in literature on deliberate transformations (e.g. Westley et al. Citation2011, Citation2013; Scoones et al. Citation2020; Charli-Joseph et al. Citation2022), but remain scarce in relation to resilience capacities. Existing definitions and frameworks on resilience capacities from a social-ecological perspective have remained structural, lacking theories of agency. We expand on this critique in section 1.2, and the Resilience Capacities Framework (RCF) we present in this paper is innovative in integrating insights into human agency derived from Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory. The framework we introduce speaks directly to two recently identified frontiers of resilience science: resilience as i) transformational capacities and ii) as relational and co-evolutionary (Folke et al. Citation2021).

Furthermore, the RCF challenges the notion of distinct pathways of persistence, adaptation and transformation, building on divergent conceptualizations in sustainability literature (Fazey et al. Citation2018). Conceptualising these processes is fraught with difficulty. On the one hand, there is a risk of each of these pathways being monumentalized as distinct strategies, and, on the other hand, there is the risk of blurring conceptual boundaries between them.

Persistence, or absorptive capacity, is often described as the ability to absorb shock. For example, a household can withstand a drought, and has high resilience if it can bounce back from shock quicker (Alinovi et al. Citation2010). Definitions of resilience quite often stop here, as the capacity of a person, household, or system, to bounce back from shock in the short term. Robustness has been used analogously, representing short-term responses to uncertainty and the ability to withstand stresses and shocks (Nicholas-Davies et al. Citation2021).

Adaptive capacity entails having the necessary resources to adapt and learn (Brown and Westaway Citation2011), and has been widely cited as a source of resilience (Gallopín Citation2006) since it enables the ability to adapt to a range of environmental and social contingencies. Adaptation is increasingly recognized as being insufficient for dealing with climate change and large-scale environmental changes. It is now widely accepted that radical transformations are required to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss, to overcome the hegemonic values, institutions and economies that constitute the system that have led to the current interacting crises that the world faces (Haverkamp Citation2021).

Transformation is a shift to a substantively new system, often intentionally, and involving priorities different to the status quo, leading to changes across multiple scales. Transformation has recently taken a prominent place in development discourse (Sachs et al. Citation2022), and is generally used to denote a progressive direction, a normatively positive ‘transformation to sustainability’ (Elmqvist et al. Citation2019). We question, however, the dominant focus on transformation and lack of criticality on whether and when transformation is ‘good’ or in what circumstances it would be important to nurture adaptive or persistent characteristics and dynamics rather than transform them. Scoones et al. (Citation2020) make the distinction between structural, systemic and enabling approaches to transformation. Enabling approaches to transformation emphasize a focus on practice and agency (Scoones et al. Citation2020).

1.2. Resilience critique and positioning resilience in ontological politics

Important critique has been leveraged against resilience thinking in i) its ‘inability to appropriately capture and reflect social dynamics in general and issues of agency and power in particular’ (Béne et al. Citation2014) and ii) its alleged role in supporting the status quo of a linear sustainable development trajectory due to its focus on persistence (Watts Citation2011; Cote and Nightingale Citation2012). There is a growing body of research which addresses both processes of power and agency in social-ecological resilience (Brown and Westaway Citation2011; Boonstra Citation2016; Cooke et al. Citation2016; Walsh-Dilley et al. Citation2016a), as well as the relationships between persistence, adaptation and transformation in research and practice (Reyers et al. Citation2022).

Resilience has been critiqued as a buzzword, for being a polysemous concept creating ‘semantic blur’ (Simon and Randalls Citation2016). Given the ever-unfolding theorization of resilience, it is worth explicitly setting out the position that this paper takes. Social-ecological resilience evolved with ecological theories of complex adaptive systems theory, in which resilience can imply both a system state (absorptive capacity) and a desirable future state (adaptive or transformative capacity). We embrace the notion of ‘resilience multiples’ as articulated by Simon and Randalls (Citation2016), where resilience has ontological flexibility, and requires specification at the point it is applied. This flexibility has been the source of further critique: that non-normative resilience risks maintaining the status quo (Swyngedouw Citation2010). While it is true that the uncritical use of the term resilience can lead to co-option of the term, it has been argued that the explicit and normative negotiation of absorptive, adaptive and transformative capacities enables an alternative, and potential transformative framing. ‘Resilience always involves choices and demands, even if the choice is to continue on current paths, perhaps perversely (Simon and Randalls Citation2016, p. 15)’. Our aim with this paper is to contribute to the articulation of absorptive, adaptive and transformative capacities in the face of change, using critical social theories of structuration and bricolage.

1.3. Resilience multiples: enter agency and bricolage

Some resilience literature has focused on the role of agency in generating change (Brown and Westaway Citation2011; Olsson et al. Citation2014; Szaboova et al. Citation2018), but exactly what resilience capacities are and who has them remains somewhat opaque. We argue for a more granular approach to conceptualise and unpick the multiple processes which entwine to produce change. The framework we lay out in the following section builds off these efforts to offer social theories of bricolage and agency to understand how resilience emerges in the face of uncertainty and change. In this paper, we further build on this critical body of work and aim to address two main research gaps: 1) how theories of agency can help specify how resilience capacities are enacted; and 2) that persistence, adaptation and transformation are often theorized and measured or assessed as independent outcomes or processes, rather than as relationally constituted. The proposed Resilience Capacities Framework is situated as part of the broader ‘relational turn’ witnessed within sustainability science, which also enables the bridging of the structure-agency divide (West et al. Citation2020; Darnhofer Citation2020). In this paper, we do not explicitly consider more-than-human agency, and instead draw on social-theories of agency and bricolage to address these respective gaps and ask the following questions: How do resilience capacities help foster locally appropriate deliberative change processes? And can the resilience capacities framework help enable resilience thinking to be better used in sustainable development practice?

We draw on Frances Cleaver’s conceptualisation of bricolage. This builds on anthropological insights into how people use and combine available materials to adapt or innovate (Levi-Strauss Citation1966) and how the resulting arrangements are legitimised and carry authority (Douglas Citation1987). Cleaver and colleagues bring these insights into engagement with social theories, such as structuration (Cleaver Citation2001, Citation2002, Citation2012; De Koning Citation2011, Citation2014; Whaley Citation2018). Bricolage is a theory of social practice explaining how actors/bricoleurs necessarily improvise in responding to changing conditions. In doing so, they use the resources at their disposal and fashion adaptations which work pragmatically and fit their social and cognitive worlds. When repeated or accumulated over time and space, such practices may become institutionalised as social norms or collective arrangements. Both individual practices and institutionalised arrangements carry meanings and power relations which shape the possibilities for persistence, adaptation, or transformation. Cleaver (Citation2012) in her work on institutional bricolage calls the resulting arrangements a ‘patchwork of the new and the second-hand’ (p. 46) suggesting that ‘borrowing well-worn practices, symbols and relationships offers a fast route to weaving new arrangements into the social fabric’. Bricolage has been used to describe the role of social innovation in transformations to sustainability, as a heuristic guiding innovation that breaks away from unsustainability path-dependence (Olsson et al. Citation2017).

The paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we introduce the resilience capacities framework, where resilience is a process of filtering which helps explore how plural pathways are enacted and performed. First, we use bricolage and structuration theory, to describe how practices are filtered, and how discursive and practical agency is both relational and dynamic. Second, we use the concept of institutional bricolage to describe how future pathways are performed through the interacting dynamic capacities of persisting, adapting and transforming. Third, we present practical applications of the resilience capacities framework returning to the cases in Tajikistan and Austria. Lastly, the paper concludes with reflections on how understanding how resilience capacities are enacted and performed can help inform alternative sustainable development pathways.

2. Resilience capacities framework – theoretical conceptualization

To address the identified gaps in resilience thinking described above, we build on the coevolutionary resilience framework previously developed by Haider et al. (Citation2021) and expand it with insights from bricolage and social agency theories. The resilience capacities framework provides a conceptual guide to understanding how dynamics of persisting, adapting and transforming are enacted. Daily practices are used here as analytical units to observe change processes since practices are recognized as a useful proxy to operationalize relationalities, through bridging structure and agency (Whaley Citation2018), social and ecological dualities (Haider et al. Citation2021), and constituting the fabric of everyday resilience (Brown Citation2015). Brown (Citation2015) anchors resilience in a set of practices – which she terms ‘everyday forms of resilience’ – that represent the strategies and struggles of people dealing with change.

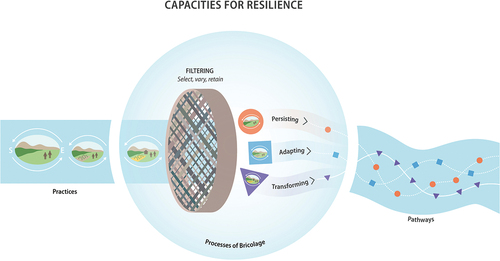

In the left–right continuum of , practices are first conceptualized as social (S)-ecological (E) relationships and then lose the ‘S-E’ construction and are represented only by daily practices themselves (such as milking, cultivating). Practices are filtered through co-evolutionary processes of selection, retention and variation based on different structural factors. These include endogenous or exogenous social and ecological dynamics (Haider et al. Citation2021) but also agency, variably exercised as discursive or practical, in relational and dynamic ways. The filtering represents ‘resilience as capacity to … ’ in which certain practices are enabled to continue, while others change and still others are discontinued through a process of bricolage. Bricolage goes beyond the practical cobbling together of ‘what works’ in a given context, and through structuration theory can help attribute meaning and authority to practices, explaining their capacities to respond to change (resilience). The emergent practices are represented by the dynamics of persisting, adapting or transforming, graphically presented in with circles, squares and triangles, respectively. These interacting capacities to persist, adapt and transform form pathways of resilience. Importantly, resilience is not an outcome, or a fundamental characteristic that a pathway or a system has, rather resilience is the process of the ever-changing capacity to respond to change (Darnhofer Citation2021),Footnote4 represented by the entirety of . In the following sections, we elaborate on bricolage and social theories of agency, and how they can be used to understand resilience as a process that is constantly being remade.

Figure 1. Resilience is the process of the ever-changing capacity to respond to change, through interacting dynamics of persisting, adapting and transforming. Bricolage and structuration theory help describe how practices are filtered and re-assembled to enact resilience capacities. Capacities to persist, adapt and transform are continuously interacting and being negotiated over time through processes of bricolage to form resilient pathways. Illustration by Azote.

2.1. Filtering and bricolaging practices

Bricolage enables an understanding of how practices change over time, while structuration theory complements bricolage to more specifically describe praxis and power, and how agency is relationally and dynamically constituted. Understanding agency requires us to explain how people can creatively improvise and innovate and at the same time reproduce taken-for-granted practices and unequal relationships of power. Individual and collective agencies are interwoven: individual agency (performed in practice) is the medium through which institutions are animated in practice (by individual bricoleurs).

2.1.1. Structuration theory: consciousness and power

Social structures are consciously reproduced through the agency of individuals who act in relation to structural rules and resources, and practice is key in mediating this integration. Sociologist Anthony Giddens developed ‘structuration theory’ in which he identifies ‘knowledgeability’ and ‘capability’ as the basic characteristics of human agency (Giddens Citation1984). Knowledgeability concerns the understanding, information and the reflexive ability to monitor the ongoing processes of social life. Capability refers to the capacity of individuals ‘to command relevant skills, access to material and non-material resources and engage in particular organising practices’ (Long Citation2001, p. 49, See Whaley Citation2018, p. 147–151 for an elaboration). Key to structuration theory, and significant to understanding agency, is the idea that actors are motivated to act by different kinds of consciousness: discursive, practical and unconscious. Discursive consciousness includes actions and beliefs which agents are able to self-consciously describe and scrutinise, as illustrated in the introductory vignette where Präa Sepp explains how he stores ideas around farming practices and retrieves them when required. The unconscious realm encompasses feelings and emotions which often unknowingly motivate actions. Finally, practical consciousness is the tacit knowledge, embedded in taken-for-granted habits, routines and precedents. For Präa Sepp, milking cattle twice a day was an unquestioned routine, part of practical consciousness, until the point that circumstances brought it into discursive scrutiny. In this paper, we focus on agency in everyday practices as key to understanding institutional functioning and development, and resilience in farming families and communities.

In Giddens’ formulation, individuals exercise agency in a recursive relationship with the ‘system’ of institutions – the state, legal systems, economic institutions – and subject to the configuration of rules and resources (the social structure). Agency is linked to power through the variable ability of different actors to deploy material (allocative) and non-material (authoritative) resources. Allocative resources refer to command over things, such as an individual’s position in relation to the means of production (for example, a blacksmith’s capacity to produce their own tools). Authoritative resources refer to command over people in organisations and institutions (for example, the authority of a donor or development agency over project beneficiaries such as in the example with the VTGs, or the authority of a traditional leader to bestow legitimacy on collective action in a community). Authoritative resources often carry ideas about proper behaviour and desirable social orders, the proper place of individuals with different social identities (gender, generation, ethnicity), and visions of desired futures. In this way, the exercise of agency is shaped by power dynamics, including the power implicit in the societal allocation of resources (through governance arrangements), the power adhering to particular social and political roles, functions and regulations, and the power to challenge boundaries, or to resist and subvert institutional arrangements.

2.1.2 Relational and dynamic agency

Further enriching our understanding of agency is the work of social theorists who focus on its relational nature, meaning that agents are always situated in manifold social relations (Burkitt Citation2016). Over-focussing on the actions of individuals can lead us to overlook both the networks of interdependence in which agency is exercised, and the collective arrangements through which agency is often shaped and channelled (Charli-Joseph et al. Citation2022). People live their lives in complex webs of relationships, and inhabit multi-layered social identities which entail rights and obligations in respect to others (Schnegg and Linke Citation2015). Such a conceptualization fits well with the complex adaptive systems ontology underpinning resilience thinking. Furthermore, actors are often reliant on others for tasks and actions that they are not knowledgeable about or capable of themselves. As we will see below, the ability of the Pamir farmers to continue to cultivate and consume Rashtak is dependent on the knowledge and capabilities of the local blacksmith and miller. From a relational perspective, the actions of an individual are shaped by variable degrees of autonomy and interconnection in groups and collectivities (Burkitt Citation2016), and agency can be understood as both enabled and constrained by these interdependencies. Emotional and embodied connections to the natural and social worlds also shape agency in both conscious and non-conscious ways, as suggested in the opening vignette where the continued cultivation of the Rashtak wheat variety is implicitly and inextricably linked to particular environments and specific cultural celebrations.Footnote5 Taking a relational agency lens to the filtering of practices thus links the actions and decisions of socially and ecologically embedded actors to networks and collectivities. An inherent limitation of conceptualizing agency based on social theory is that it perpetuates a dichotomy between social and ecological processes. We point to complementary work by Darnhofer (Citation2020) who uses a process-relational perspective and draws on work from new-materialism to extend agency to more-than-humans as a way to make openings for change more visible. We maintain, however, that structuration theory has enabled a more detailed and nuanced perspective of how capacities are enabled or constrained, not yet afforded by more relational theories.

2.2. Bricolage, capacities and future pathways

How does the exercise of agency shape resilient pathways, and how does a focus on agency and people’s practices help us to understand the possibilities for transformative change? We move now to describe how different practices shape development pathways through processes of bricolage. Here, we draw on the concept of institutional bricolage as developed by a number of authors over the past two decades or so (Cleaver Citation2001, Citation2002, Citation2012; De Koning Citation2011, Citation2014; Whaley Citation2018; Mayaux et al. Citation2022). Institutional bricolage is conceived of as a process through which people adapt to the contingencies of everyday life and changing environments, by assembling or reshaping socio-institutional arrangements, drawing on the materials and resources available to them. They might use components (practices, rules, roles, relationships, symbols) from a variety of origins, and these are reused, reworked or refashioned to perform new functions. These adapted configurations are attributed meaning and authority by drawing on tradition, analogies to other orders, powerful actors and discourses, and accepted ideas about ‘the right way of doing things’. The resulting arrangements are dynamic hybrids of ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’, formal and informal elements (Cleaver Citation2012).

This work has been applied to the governance of natural resources, to agriculture; urban development; service delivery; conservation (for example, van Mierlo and Totin Citation2014; Frick-Trzebitzky Citation2017; Benjaminsen Citation2017; Hassenforder and Barone Citation2019; Gebara Citation2019; Karambiri et al. Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2021). These and related papers show the ways in which institutions are pieced together from a variety of sources, resulting in blended arrangements which sometimes reinforce and sometimes reshape existing social structures and relationships. The concept has been taken up in aligned fields (including those originating in different academic traditions) and applied to thinking about payment for ecosystem services, adaptive governance, and sustainability. Here, a bricolage lens helps to draw attention to the role of power process and meaning in governance dynamics (Van Hecken et al. Citation2015; Ishihara et al. Citation2017; Cleaver and Whaley Citation2018). A particular focus of the broader institutional bricolage literature has been to understand how such targeted interventions to establish farmer associations, water user organisations, income generating groups, forest management committees and the like develop into hybrid arrangements, unevenly and intermittently implemented, often with outcomes unintended by planners (Whaley et al. Citation2021).

An example which illustrates some of the key elements of institutional bricolage is offered in the work of Tavengwa Chitata and colleagues, which traces the management of a smallholder irrigation scheme in Zimbabwe, evolving over the last 40 years or so (Chitata et al. Citation2021, Citation2022). In this scheme, farmers draw on the formalised mechanisms (the constitution and associated rules) of their registered cooperative, as well as those derived from accepted social norms and cultural traditions to collect funds, manage the infrastructure, and distribute water. Different logics are blended in the daily practice of water management. These include economic rationalities concerning the control and distribution of water in the interest of crop production, combined with the moral-ecological imperatives to care for each other, for the infrastructure, for nature (water, algae, soil), and for the ancestral spirits. One result of these blended arrangements is that the formalised sanctions for non-payment or free riding specified in the by-laws of the scheme, are infrequently applied and often modified in favour of the offender. A number of different sources of authority (state agents, founding members of the scheme, Chiefs, God, the ancestors and spirits) and discourses are drawn upon to legitimise adapted arrangements. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated an ongoing crisis of government water service provision, as infrastructure was not maintained by state agents and several of the boreholes providing irrigation and drinking water in the community broke down. The farmers reacted by expanding the rules of access in the irrigation scheme, to include those drawing water for domestic purposes and artisanal miners operating in the areas, justifying this with reference to a variety of overlapping crisis discourses and livelihoods imperatives (Chitata et al. Citation2023). The case illustrates the ways in which collective arrangements for the management of a resource are often formed adaptively and dynamically, drawing on a diversity of mechanisms, sources of authority and rationalities. Adaptations to management are practical, embodied in the everyday actions and capabilities of the farmers, discursively informed and legitimised. However, they do not affect everyone equally – adapted management mechanisms drawn from the social setting may benefit those already advantaged in social structures. In this case, the founding farmers of the scheme, traditional leaders and government officials are predominantly men, and the authority of patriarchal and cultural social hierarchies overlaps and intersects with that of the state. The case raises pertinent questions about the resources that enable individuals to act as bricoleurs, and the extent to which such blended and adapted arrangements, enacted through everyday practices, can further progressive social and environmental changes.

A bricolage perspective helps to enrich the explanation of how future pathways are produced in the interplay of social–ecological relationships and the variation, selection and retention of daily practices.

Focussing on this interplay between the agency of bricoleurs and social structure helps us to explain how certain aspects of development interventions are incorporated into local arrangements, others reshaped, transformed or rejected. The resilience capacities framework enables an elaboration of how such change occurs by bringing a focus on processes of bricolage (Cleaver Citation2012) into engagement with coevolution (Haider et al. Citation2021). By bringing the two approaches together in the framework, we can conceptualise bricolage as a process of piecing together in which different configurations of practices are selected, retained and adapted by actors (practically and discursively) to shape future pathways.

3. Resilience capacities framework – practical applications

What would applying the resilience capacities framework look like in practice? Here, we apply it to two cases of rural development in the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan, where innovative ‘Village Technology Groups’ (VTGs) have recently been instituted. First, we analyse the consequences of a past intervention, and secondly apply the framework to understand how resilience capacities unfold in future visions. VTGs were established in the mid 2010s by a donor supporting selected successful practices in communities, some of which were innovations, and others adaptations of tradition.Footnote6 Examples of VTGs in the Pamirs include the continued cultivation of traditional wheat varieties (as in the introductory vignette in this paper), new marketing of traditional medicines, communal tool exchange or maintenance and innovation of water mills.

The anecdotal data used here is based on 10+ years of research in the Pamir region (Van Oudenhoven and Haider Citation2015; Haider and van Oudenhoven Citation2018; Haider et al. Citation2019). In 2016, the author/s participated in a large community-led cooking festival which was held with VTG representatives from each of the different valleys in the Tajik Pamirs, and future visions were developed and captured by a local watercolor artist.

3.1. Filtering and bricolaging practices – applications

The vignette in the introduction described the ritual of Baht-ayom made with the red wheat Rashtak, a sweet porridge prepared for Nawruz, the Persian new year. The land-race variety Rashtak was prevalent in the Pamirs until the mid 1990s, when a development intervention intended to improve production with F-hybrid varieties was introduced. This historical case, documented in Haider et al. (Citation2019), provides an interesting example to work through the resilience capacities framework. In most communities, the new seeds were accepted, tried and the old seeds were lost. The new seeds were successful for a few years, after which they failed due to myriad reasons: failure to regularly apply agrochemical inputs, the inability to save the seeds from year to year, and the poor taste and quality of the new wheat were cited as the most common examples. After the F1-hybrids failed, most of the communities did not bring back traditional varieties, but rather let their fields permanently fallow, or converted to grassland for hay-making and grazing. While the f1-hybrid seed intervention should not have been irreversible, it shifted enough of the values, environment, economy and social structures in the communities so that they did not go back to grain cultivation. Today, the communities in this valley are dependent on food aid from the World Food Programme in the form of foreign flour. Baht-ayom is still celebrated, where the porridge made from this imported flour is supplemented with sugar and fat to add flavour. A harvest dance is performed by school children in which traditional music and practices are celebrated and passed on between the generations, adapting practices based on available resources. The development pathways could be conceptualized as being dominated by an adaptive pathway: the communities adapted to a new social-political reality in which foreign aid provides substitutable goods. The adaptation is a kind of acceptance of structural change, presented as continued tradition.

Rashtak continues to be cultivated in one remote community of the valley, where there is now a Village Technology Group. This community also accepted and tried the improved variety in the 1990s, but without giving up Rashtak. Processes of variation continue year to year (dozens of landrace seed varieties are sown together), selection (of Rashtak), retention (of the seed and practices despite external pressures to adopt new seeds) are supported by allocative and authoritative resources. The strong practical consciousness embedded in the spiritual, ecological and communal relations that comprise the practice of cultivating, harvesting and celebrating Rashtak are enabled through the community having some autonomy of allocative resources. The practical consciousness enabled the cultivation and celebration of Rashtak to continue because the community maintained control of allocative resources and resisted the new seeds and agrochemical inputs offered to them. The community’s filtering and bricolaging to maintain certain valued practices is relationally embedded. Rashtak is grown in rotation with mach, a grass-pea, which has ecological benefits for soil quality. ‘We rotate lands mach and wheat so that the nutrients can be given back to the soil’. Giving up one variety would have consequences for mach and for the soil. Moreover, allocative resources are collectivity owned. For centuries, there has been a communal blacksmith who makes specialized agricultural tools used for cultivation of traditional varieties, and a miller who mills all the grain for reciprocal exchange. Through this, allocative and authoritative resources are entangled: the community manages to retain control over their material (labour and technology) and non-material means of production and corresponding meanings. The continuation of the tradition of cultivating, harvesting and celebrating Rashtak and Baht-ayom reinforces certain social-norms around traditions and maintenance of related spiritual practices and language. The introduction and external support for village technology groups further supports the practices through financial support and social approval, which reinforces the norms. Bringing these explicit conceptualizations of agency into the framework allows us to better understand why this landrace wheat was maintained.

The development pathway could be described as an interplay between the dynamics of persistence and transformation.

3.2. Bricolage, capacities and future pathways – applications

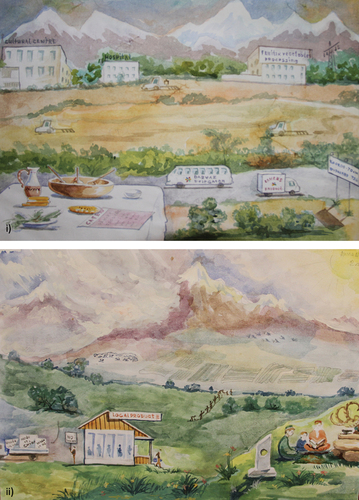

How does the bricolage of different capacities play out to shape development pathways? Presenting two future visions from two village technology groups, we draw on the resilience capacities framework to work through these empirical examples. The village technology groups are great examples of institutional bricolage: they are formed based on novel combinations of ‘old’ practices that have been successful along with new technology, knowledge or networks that keeps them relevant or allows them to change to new circumstances. Bricolage is an inherently dynamic and adaptive process shaped by creative bricoleurs, who skilfully assemble arrangements to fit their social circumstances and ensure their acceptability. But this very requirement for social fit also constrains the possibilities of arrangements made through bricolage. In the reworking of the existing institutional arrangements, actors innovate, but they do so within the limits of their resources (individual and societal), their social circumstances and what is perceived as legitimate. In other words, social structure (a socially produced set of rules, accepted roles and resource allocations) both constrains and enables creative bricolage. Bricolage processes take place over time, with bricoleurs both responding to and drawing legitimacy for their arrangements variously from tradition and precedent, changing development policies, political and social discourses and economic and environmental events and phenomena. In panel i of , we continue to follow the VTG conserving Rashtak. The second vision, in panel ii, is another VTG, working with foraging of mountain herbs.

Figure 2. Two alternative future visions for the Pamirs. (i) A vision from the village technology group harvesting Rashtak, and can be called ‘traditional innovations’. (ii) A vision from the village technology group from Ishkashim valley who sell wild herbs and medicinal plants and can be called ‘food sovereignty’. Water color by Yorali Berdov.

The painting in image i combines old and new elements, where capacities of persistence, adaptation and transformation intertwine. At the foreground, local, traditional and nutritious food is valued and presented on the table of a new local restaurant. In this vision, livelihoods can be made from celebrating local food and culture. A food truck transports local food products, particularly milk products, between different valleys, and a factory is featured to help preserve food products, such as drying fruit. More land is being used, and small tractors are available which are able to work on small plots of land and steep slopes. A cultural centre and hospital have been built to enhance well-being and celebrate local culture. This vision captures how practices have been filtered to preserve some valued traditions, whilst, through processes of bricolage, these are blended together with new structures such a restaurant and cultural centre, or trucks that transport milk between valleys.

In contrast, the ‘Food Sovereignty’ vision (panel ii, ) is primarily characterized by dynamics of persistence. Local products are sold at a small local shop, and few imports are necessary. In the background, one can see clouds which represent the changing climate, and people up on the hillside collecting wild foods in order to compensate for the losses in crop productivity due to climatic changes. There is an increase in rainfed agriculture, particularly fodder crops, in the land above the irrigation channel. The irrigation channel itself is maintained through hashar, collective work around irrigation. To the right of the image is a family reading together between a spiritual shrine and a sun-dial which is an important part of the local way of telling time (see also Kassam Citation2009), representing intergenerational knowledge exchange, ritual and spiritual freedom. The head of the village technology group explicitly brings these traditions into collective discursive consciousness: ‘Because this young generation have a future and we are trying to teach them to make sure they don’t forget their tradition to continue in the future. We are attracting young people, we don’t want to forget, or to lose that tradition’.

4. Reflections and implications for practice

So far, we have drawn on the empirical material to consider the ways in which allocative and authoritative resources are deployed through processes of bricolage to shape the development pathways of a community. In this section, we further explore the interplay of agency and resilience capacities and the implications for sustainable development.

4.1. Practical consciousness as key enabler of resilience capacities

The case of the village technology group explored in this paper emphasises the importance of considering agency as comprised of both practical and discursive consciousness. Development interventions, which are often shaped around ‘sayings’ – public written and verbal articulations of needs and proposed solutions – could apriori recognise practical agency and consider this in the design and implementation of interventions. The Village Technology Groups are an example of the interplay between practical and discursive agency, where the intervention facilitates practical agency being brought into discursive scrutiny. In the donor-NGO-community power dynamic in the Pamirs, we can see how in this case the Donor has used authoritative resources to translate practical consciousness (the practices around baht-ayom) to discursive consciousness through the formation of Village Technology Groups.

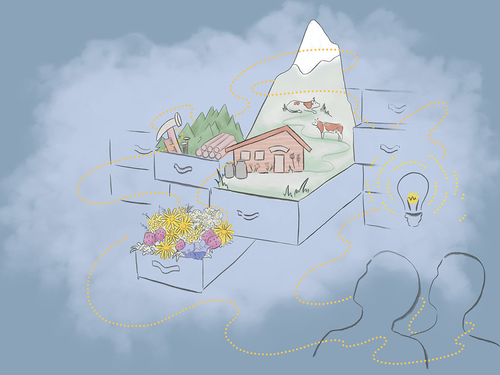

Akin to ‘facilitated bricolage’ (Whaley et al. Citation2021), the resilience capacities framework could help actors (farmers, development agency, funders) jointly filter and re-assemble practices, reflexive of how practices change, and thereby bring more practical consciousness into discursive consciousness. The continuous experimentation of practices is a key component of resilience, and rather than this appearing as a linear trajectory of trial-and-error with strong path-dependencies (as we saw in the case of the lost seed variety), a resilience capacities approach would encourage the notion of a ‘drawer of ideas’ (introduced by Präa Sepp) in which ideas and practices are stored and filtered when they are needed, which enables creative responses in the face of uncertainty ().

Figure 3. Präa Sepp’s drawer of ideas provides a powerful metaphor to unpack the black-box of capacity: who has it, how it is acted on. Which ideas about practices get put in the box in the first place, how are they filtered, what processes emerge from the cobbling together of different ideas and practices. Illustration by Azote.

4.2. Intertwined bricolage of persistence, adaptation and transformation

The drawer of ideas () is a metaphor for bricolage, in which Präa Sepp draws on place-specific cultural and social resources, and different ideas and resources from other places and contexts, and cobbles these together to make them work for him, in his context. Cultural traditions, for example, can be both a resource and a constraining factor in bricolaged arrangements. Returning to the opening vignette of dairy farming in the Alps, the cultural tradition of milking cows twice a day is widely accepted as the right way of doing things. But when Präa Sepp is faced with the need to adapt to changing conditions, he finds out that he can change those established practices. And yet, he changes his daily practices in order to maintain a way of life and production (extensive transhumance) that is widely considered to be traditional. However, Sepp does not see alpine milk-processing as ‘traditional’; rather, it enables the life he wants for himself, his family, his livestock and the landscape. Filtering which old practices to maintain, and when and which new practices to try and to adopt are central to enacting resilience capacities. While the practice of milking once a day is characterised by adaptive capacities, it is part of a larger transformative capacity and movement since it resists the authoritative dominance of a discourse of growth and shows that alternative modes of production are possible. Präa Sepp says: ‘we [farmers] are being led in a completely other direction, not towards sustainability. Rather, always in the direction of more, more, more’. Milking once a day is one of the many daily practices which enables a more extensive, subsistence-based lifestyle, and arguably also contributes to more systemic change against the status quo.

There is also hard work involved in the exercise of agency and resistance. One day, as I (Jamila) was in the cheese room stirring the cheese with a hand-crafted wooden whisk, Sepp exclaimed:

‘It is so difficult. It is really so difficult!’

‘What’s difficult?’

‘To be so stubborn… to preserve certain old things. Because you have to be very consistent and have a will of your own to say: no, it can stay, and not the requested, or “would-liked-to-be-seen-easy-to-clean-stainless-steel-thingymabob”, which then gets cold in your fingers and hands. But it could be that my [wooden] whisk can’t be washed so cleanly and so… Difficult. But I like it [the whisk] too, you know. Laughs. And if it ever broke, I would make one again. But yes, yes, you have to have a certain stubbornness’.

As researchers engaged in sustainability outcomes and pathways, it seemed to us that this kind of daily decision to maintain a certain tool is important to the individual but it is unclear how important it is to changing or challenging social structures or wider political economies. When discussing this together with Sepp, he said ‘If you don’t change the small, you won’t influence the whole’.

4.3. Contribution of resilience capacities framework to sustainable development

How can the resilience capacities framework contribute to informing interventions that aim to implement sustainable rural development? Reyers et al. (Citation2022) conduct a review of whether and how resilience thinking has reshaped sustainable development practice, and conclude that dominant applications diverge substantially from the science. In particular, there are various shifts that can be made in order to more meaningfully integrate resilience thinking into policy and practice. Here, we posit that the resilience capacities framework speaks directly to four of these shifts and could therefore help to foster context-sensitive deliberative change processes. We reflect on the following four shifts (from Reyers et al. Citation2022): 1) From capitals to capacities, 2) from objects to relations, 3) from outcomes to processes and 4) from generic interventions to context sensitivity.

From capitals to capacities: Reyers et al. identify that while there has been a shift in discourse from capitals to capacities, there remains a dearth of indicators or metrics that can measure progress on building capacities over resource capital, in large part because of linear and static design and evaluation schemes. The Resilience Capacities Framework (RCF) casts light on allocative and authoritative resources and how they are enacted to constrain or enable actions is an explicit way to move from capitals to capacities in a relational way.

From object to relational: The RCF enables an understanding of agency not as something that an actor has, but rather a capacity that is relationally constituted through the distribution of enabling and constraining capacities.

From outcomes to processes: Using bricolage, the RCF enables a more process-based perspective in centring the messy cobbling together dynamics of persistence, adaptation or transformation in processes of resilience-making.

From interventions to context sensitivity: the coevolutionary dynamics underpinning the resilience capacities framework enable an understanding of how interventions interact with context, and that the changing context in-turn changes the scene for future interventions. In other words, the intervention and context co-evolve, invoking context sensitivity rather than dependence.

4.4. Resilience capacities framework as normative, situated and political

The resilience capacities framework is a contribution within the broader discourse of reframing development from a resilience perspective. It is flexible and open, and therefore also normative, situated and political. The framework should be seen as an invitation to all researchers engaging with social theory, to expand and/or change the framework to make it work for specific purposes. We use structuration theory to bring in agency, but other theories could be used. For example, using the framing of Practical Rationality (Sandberg and Tsoukas Citation2011) reveals the logic of practice theory by focusing on i) entwinement (coevolution) and ii) temporary breakdown (interventions or branch points). We hope that RCF can foster engagement with different social theoretical approaches and so complement and enhance understandings of resilience. Engagement with the RCF should reflect on its positionality within the context of intervention. The normative stance of resilience must always be articulated at the point of intervention, it will always involve choices and the role of any researcher or practitioner is to make these choices visible. We hope thereby that the resilience capacities framework opens up new creative spaces for resilience-making, as oppose to obscuring them.

Implications and recommendations for rural development: The RCF illustrates how processes of resilience are enacted through bricolage. What does this enhanced conceptual understanding mean for practical rural development interventions? Useful approaches gleaned from experiences of facilitating bricolage (Whaley et al. Citation2021) include working with a plurality of actors, arrangements and practices and creating a flexible enabling environment that supports the exercise of local agency and experimentation.

5. Conclusions for theory and practice

Resilience is the capacity to respond to change through persisting, adapting and transforming. In this paper, we have proposed drawing on bricolage and structuration theories to deepen existing conceptualisations of resilience capacities. Giddens’ structuration theory usefully breaks down capacity into knowledgeability and capability which are motivated by practical or discursive consciousness and enabled or restricted by allocative and authoritative resources. Thus, through structuration theory, we are better able to explain how certain practices are filtered and re-assembled, resulting in entangled pathways of resilience. Bricolage theory helps us both a) scale up individual agency to institutional and b) provides a framing to conceptual and analyse entangled dynamics of persistence, adaptation and transformation over time. We envision that the Resilience Capacities Framework can be useful in the process of facilitating bricolage, and in communicating and scaling existing best practices through translation from practical to discursive consciousness. A practical implication is to acknowledge that the key to resilience (capacity to respond to uncertainty) is to maintain open, flexible spaces in which trial and error of practices is encouraged, and the often messy process of bricolage is enabled. As a final reflexive note, the development of resilience theory itself is constantly undergoing a process of filtering and bricolage as part of the knowledge–practice interface to remain relevant to the most pressing sustainability questions of our time.

Acknowledgements

Thank-you to the communities in the Pamirs for participating in the workshops and for sharing your knowledge. Monika and Sepp Rieser, thank-you for welcoming me into your home, teaching me how to milk cows, make butter and cheese and for sharing your experiences. Ika Darnhofer, I am grateful for our exchange on the drawer of ideas. Thank you to Blanca Gonzalez, Amanda Jonsson, Romina Martin, Liz Drury O’Neill and Courtney Adamson for valuable comments on the manuscript. Thank you to the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their time and valuable suggestions which helped improve the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Ethical procedures were followed and approved according to Stockholm University protocol. Anonymity was agreed in the initial data collection. Over time, the work transitioned to a co-production process, and the research participants wished to be named for their ideas and contributions. A formal ethical amendment was approved to reflect this co-productive turn.

2. Sepp identifies as ‘Präa Sepp’ which represents the name of his farm and land. He drops the ‘u’ from Präau to remain closer to the spoken dialect. ‘There is only one Präa Sepp, but many Josef Riesers’. In this way, Präa Sepp also offers an intergenerational perspective.

3. Vignette 1 (Pamirs) is grounded in over a decade of research in the Pamir Mountains (see also Van Oudenhoven and Haider Citation2015; Haider et al. Citation2019).Vignette 2 (Austrian Alps) draws on primary data from an on-going research project on Alpine dairy farming resilience.

4. ‘Resilience is then not seen as a property, attribute, or essence of a “stable” farm; it is not a substance, a “thing” that can be measured. Rather, resilience continually emerges out of the configuration of tangible and intangible relations and the ever-changing dynamics of these processes. In other words, a farm “is” not resilient, but farming resilience is continuously made and re-made (Darnhofer et al. Citation2016). Resilience is then not about maintaining specific functions, structures, or feedbacks, or about avoiding thresholds, it is about enabling ongoing, creative, and responsive change’ (Darnhofer Citation2021, p. 6).

5. While in this paper we focus our conceptualization on social theories of agency, we acknowledge the ‘relational turn’ in sustainability science (West et al. Citation2020) and the need to extend relational understandings of agency to the more-than-human actors (Whatmore Citation2006), as actants as opposed to just actors, and to go beyond interactions and to think about intra-actions (Barad Citation2007). The resilience capacities framework purposefully embeds relational ambiguity in order to account for these diverse conceptualisations.

6. The donor called this ‘positive deviance’ behaviour: an approach to social change which supports practices in communities which are uncommon but successful in problem solving.

References

- Alinovi L, Mane E, Romano D. 2010. Measuring household resilience to food insecurity: application to palestinian households. In Agricultural Survey Methods. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; p. 341–15. doi: 10.1002/9780470665480.ch21.

- Anderies J, Folke C, Walker B, Ostrom E. 2013. Aligning key concepts for global change policy: robustness, resilience, and sustainability. Ecol Soc. 18(2). doi: 10.5751/ES-05178-180208.

- Barad K. 2007. Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Béné C, Frankenberger T, Nelson S. 2015. Design, monitoring and evaluation of resilience interventions: conceptual and empirical considerations. Institute of Development Studies. [accessed 2023 Feb 7]. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/6556.

- Béné C, Newsham A, Davies M, Ulrichs M, Godfrey‐Wood R. 2014. Review article: Resilience, poverty and development. J Int Dev. 26(5):598–623. doi:10.1002/jid.2992.

- Benjaminsen G. 2017. The bricolage of REDD + in Zanzibar: from global environmental policy framework to community forest management. J East Afr Stud. 11(3):506–525. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2017.1357103.

- Boonstra WJ. 2016. Conceptualizing power to study social-ecological interactions. Ecol Soc. 21(1):rt21. doi: 10.5751/ES-07966-210121.

- Brown K. 2015. Resilience, development and global change. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203498095.

- Brown K, Westaway E. 2011. Agency, capacity, and resilience to environmental change: lessons from human development, well-being, and disasters. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 36(1):321–342. doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV-ENVIRON-052610-092905.

- Burkitt I. 2016. Relational agency: relational sociology, agency and interaction. Eur J Soc Theory. 19(3):322–339. doi: 10.1177/1368431015591426.

- Charli-Joseph L, Siqueiros-García JM, Eakin H, Manuel-Navarrete D, Mazari-Hiriart M, Shelton R, Pérez-Belmont P, Ruizpalacios B. 2022. Enabling collective agency for sustainability transformations through reframing in the Xochimilco social–ecological system. Sustain Sci. 1:1215–1233. doi: 10.1007/s11625-022-01224-w.

- Chitata T, Kemerink-Seyoum J, Cleaver F. 2021. Engaging and learning with water infrastructure: Rufaro irrigation scheme, Zimbabwe. Water Altern. 14(3):690–716. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol14/v14issue3/640-a14-3-3.

- Chitata T, Kemerink-Seyoum J, Cleaver F. 2022. ‘Our humanism cannot be captured in the bylaws’: how moral ecological rationalities and care shape a smallholder irrigation scheme in Zimbabwe. Environ Plan E. 251484862211379. doi: 10.1177/25148486221137968.

- Chitata T, Kemerink-Seyoum J, Cleaver F. 2023. Together strong or falling apart? coping with covid-19 in Rufaro smallholder irrigation scheme, Zimbabwe. Int J Commons. 17(1):87–104. doi: 10.5334/ijc.1194.

- Cleaver F. 2001. Institutional bricolage, conflict and cooperation in Usangu. IDS Bull. 32(4):26–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2001.mp32004004.x.

- Cleaver F. 2002. Reinventing institutions: bricolage and the social embeddedness of natural resource management. Eur J Dev Res. 14(2):11–30. doi: 10.1080/714000425.

- Cleaver F. 2012. Development through bricolage : rethinking institutions for natural resource management. London: Routledge.

- Cleaver F, Whaley L. 2018. Understanding process, power, and meaning in adaptive governance: a critical institutional reading. Ecol Soc. 23(2):art49. doi: 10.5751/ES-10212-230249.

- Cooke B, West S, Boonstra WJ. 2016. Dwelling in the biosphere: exploring an embodied human–environment connection in resilience thinking. Sustain Sci. 11(5):831–843. doi: 10.1007/S11625-016-0367-3/FIGURES/3.

- Cote M, Nightingale AJ. 2012. Resilience thinking meets social theory. Prog Hum Geogr. 36(4):475–489. doi: 10.1177/0309132511425708.

- Darnhofer I. 2020. Farming from a process‐relational perspective: making openings for change visible. Sociol Ruralis. 60(2):505–528. doi: 10.1111/soru.12294.

- Darnhofer I. 2021. Farming resilience: from maintaining states towards shaping transformative change processes. Sustainability. 13(6):3387. doi: 10.3390/su13063387.

- Darnhofer I, Lamine C, Strauss A, Navarrete M. 2016. The resilience of family farms: towards a relational approach. J Rural Stud. 44:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.01.013.

- De Koning J (2011). Reshaping institutions: bricolage processes in smallholder forestry in the Amazon. Wageningen University (PhD Thesis). http://edepot.wur.nl/160232.

- De Koning J. 2014. Unpredictable outcomes in forestry—governance institutions in practice. Soc Nat. 27(4):358–371. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2013.861557.

- Douglas M. 1987. How institutions think. London: Routledge.

- Elmqvist T, Andersson E, Frantzeskaki N, McPhearson T, Olsson P, Gaffney O, Takeuchi K, Folke C. 2019. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat Sustain. 2(4):267–273. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0250-1.

- Eurostat. (2020). Eu’s organic farming area reaches 14.7 million hectares. [accessed 2023 Feb 7]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20220222-1.

- Fazey I, Schäpke N, Caniglia G, Patterson J, Hultman J, van Mierlo B, Säwe F, Wiek A, Wittmayer J, Aldunce P, et al. 2018. Ten Essentials for action-oriented and second order energy transitions, transformations and climate change research. Energy Res Social Sci. 40:54–70. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.11.026.

- Folke C, Biggs R, Norström AV, Reyers B, Rockström J. 2016. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol Soc. 21(3). doi: 10.5751/ES-08748-210341.

- Folke C, Haider LJ, Lade SJ, Norström AV, Rocha J. 2021. Commentary: resilience and social-ecological systems: a handful of frontiers. Glob Environ Change. 71:102400–103780. doi: 10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2021.102400.

- Frick-Trzebitzky F. 2017. Crafting adaptive capacity: institutional bricolage in adaptation to urban flooding in Greater Accra. Water Altern. 10(2):625–647.

- Gallopín GC. 2006. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob Environ Change. 16(3):293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004.

- Gebara MF. 2019. Understanding institutional bricolage: what drives behavior change towards sustainable land use in the Eastern Amazon? Int J Commons. 13(1):637. doi: 10.18352/ijc.913.

- Giddens A. 1984. The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. USA: University of California Press.

- Haider LJ, Schlüter M, Folke C, Reyers B. 2021. Rethinking resilience and development: a coevolutionary perspective. Ambio. 50(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13280-020-01485-8.

- Haider LJ, van Oudenhoven FJW. 2018. Food as a daily art: ideas for its use as a method in development practice. Ecol Soc. 23(3):14. doi: 10.5751/ES-10274-230314.

- Haider LJ, Boonstra WJ, Akobirshoeva A, Schlüter M. 2019. Effects of development interventions on biocultural diversity: a case study from the Pamir mountains. Agric Human Values. 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10460-019-10005-8.

- Hassenforder E, Barone S. 2019. Institutional arrangements for water governance. Int J Water Res Dev. 35(5):778–802. doi: 10.1080/07900627.2018.1431526.

- Haverkamp J. 2021. Collaborative survival and the politics of livability: towards adaptation otherwise. World Dev. 137:105152. doi: 10.1016/J.WORLDDEV.2020.105152.

- Ishihara H, Pascual U, Hodge I. 2017. Dancing with storks: the role of power relations in payments for ecosystem services. Ecol Econ. 139:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.04.007.

- Karambiri M, Brockhaus M, Sehring J, Degrande A. 2020. ‘We are not bad people’ – bricolage and the rise of community forest institutions in Burkina Faso. Int J Commons. 14(1):525–538. doi: 10.5334/ijc.1061.

- Kassam K-A. 2009. Viewing Change Through the Prism of Indigenous Human Ecology: Findings from the Afghan and Tajik Pamirs. Hum Ecol. 37(6):677–690. doi: 10.1007/s10745-009-9284-8.

- Kemmis S, Wilkinson J, Edwards-Groves C, Hardy I, Grootenboer P, Bristol L, editors. 2013. Changing Practices, Changing Education. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-4560-47-4_2.

- Levi-Strauss C. 1966. The savage mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Long N. 2001. Development sociology: actor perspectives. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Mayaux P-L, Dajani M, Cleaver F, Naouri M, Kuper M, Hartani T. 2022. Explaining societal change through bricolage: transformations in regimes of water governance. Environ Plan E. 251484862211436. doi: 10.1177/25148486221143666.

- Nicholas-Davies P, Fowler S, Midmore P, Coopmans I, Draganova M, Petitt A, Senni S. 2021. Evidence of resilience capacity in farmers’ narratives: Accounts of robustness, adaptability and transformability across five different European farming systems. J Rural Stud. 88:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.07.027.

- Niedermayr J, Quendler E, Resl T. 2015. ‘Family farming in Austria definition, characteristics and developments. J Agric for. 61(4). doi: 10.17707/AgricultForest.61.4.08.

- Olsson P, Galaz V, Boonstra WJ. 2014. Sustainability transformations: a resilience perspective. Ecol Soc. 19(4). [accessed 2023 June 1]. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269651.

- Olsson P, Moore M-L, Westley FR, McCarthy DDP. 2017. The concept of the Anthropocene as a game-changer: a new context for social innovation and transformations to sustainability. Ecol Soc. 22(2). doi: 10.5751/ES-09310-220231.

- Quinlan AE, Berbés-Blázquez M, Haider LJ, Peterson GD. 2016. Measuring and assessing resilience: broadening understanding through multiple disciplinary perspectives. J Appl Ecol. 53(3):677–687. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12550.

- Redman C. 2014. Should sustainability and resilience be combined or remain distinct pursuits? Ecol Soc. 19(2). doi: 10.5751/ES-06390-190237.

- Reyers B, Moore M-L, Haider LJ, Schlüter M. 2022. The contributions of resilience to reshaping sustainable development. Nat Sustain. 5(8):657–664. doi: 10.1038/s41893-022-00889-6.

- Sachs JD, Kroll C, Lafortune G, Fuller G, Woelm F. 2022. Sustainable development report 2022. Cambridge University Press.

- Sandberg J, Tsoukas H. 2011. Grasping the logic of practice: theorizing through practical rationality. Acad Manag Rev. 36(2):338–360. doi: 10.5465/amr.2009.0183.

- Schnegg M, Linke T. 2015. Living institutions: sharing and sanctioning water among pastoralists in Namibia. World Dev. 68:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.024.

- Scoones I, Stirling A, Abrol D, Atela J, Charli-Joseph L, Eakin H, Ely A, Olsson P, Pereira L, Priya R, et al. 2020. Transformations to sustainability: combining structural, systemic and enabling approaches. Curr Opin Env Sust. 42:65–75. [Preprint]. doi: 10.1016/J.COSUST.2019.12.004.

- Simon S, Randalls S. 2016. Geography, ontological politics and the resilient future. Dialogues Hum Geogr. 6(1):3–18. doi: 10.1177/2043820615624047.

- Swyngedouw E. 2010. Apocalypse forever? Theor Cult Soc. 27(2–3):213–232. doi: 10.1177/0263276409358728.

- Szaboova L, Brown K, Chaigneau T, Coulthard S, Daw TM, James T. 2018. Resilience and wellbeing for sustainability. In: Schreckenberg K, Mace G, and Poudyal M, editors. Ecosyst Serv Poverty Alleviation. London: Routledge; p. 273–287.

- Van Hecken G, Bastiaensen J, Windey C. 2015. Towards a power-sensitive and socially-informed analysis of payments for ecosystem services (PES): addressing the gaps in the current debate. Ecol Econ. 120:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.10.012.

- van Mierlo B, Totin E. 2014. Between script and improvisation: institutional conditions and their local operation. Outlook Agric. 43(3):157–163. doi: 10.5367/oa.2014.0179.

- Van Oudenhoven F, Haider J. 2015. With our own hands : a celebration of food and life in the Pamir mountains of Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Netherlands: LM Publishers.

- Walsh-Dilley M, Wolford W, Mccarthy J. 2016a. Rights for resilience: food sovereignty, power, and resilience in development practice. Ecol Soc. 21(1). doi: 10.5751/ES-07981-210111.

- Wang RY, Chen T, Wang OB. 2021. Institutional bricolage in irrigation governance in rural northwest China: Diversity, legitimacy, and persistence. Water Altern. 14(2):350–370.

- Watts MJ. 2011. Ecologies of rule: African environments and the climate of neoliberalism. In: Calhoun C, and Derluguian G, editors. The deepening crisis: governance challenges after neoliberalism. New York, USA: New York University; p. 67–91. doi: 10.18574/nyu/9780814772805.003.0004.

- West S, Haider LJ, Stålhammar S, Woroniecki S. 2020. A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosyst People. 16(1):304–325. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2020.1814417.

- Westley F, Olsson P, Folke C, Homer-Dixon T, Vredenburg H, Loorbach D, Thompson J, Nilsson M, Lambin E, Sendzimir J, et al. 2011. Tipping toward sustainability: emerging pathways of transformation. Ambio. 40(7):762–780. doi: 10.1007/s13280-011-0186-9.

- Westley F, Tjornbo O, Schultz L, Olsson P, Folke C, Crona B, Bodin Ö. 2013. A theory of transformative agency in linked social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc. 18(3). doi: 10.5751/ES-05072-180327.

- Whaley L. 2018. The Critical Institutional Analysis and Development (CIAD) framework. Int J Commons. 12(2):137–161. doi: 10.18352/ijc.848.

- Whaley L, Cleaver F, Mwathunga E. 2021. Flesh and bones: working with the grain to improve community management of water. World Dev. 138(1):105286. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105286.

- Whatmore S. 2006. Materialist returns: practising cultural geography in and for a more-than-human world. Cult Geogr. doi: 10.1191/1474474006cgj377oa.