ABSTRACT

The discipline of forestry developed in 18th century Europe from the confluence of concerns about timber supply, industrialization and a disintegration of communal land rights. Out of this history, forestry has developed into an institution-a set of conventions, norms and legal rules influencing decisions made by foresters in their professional roles-that is rooted in a particular worldview that frames forests primarily as production systems to be managed for the satisfaction of human needs and preferences. We identify four institutional foundations of forestry drawing from textbooks, histories, university curriculum, professional societies’ codes of ethics, policy documents, peer reviewed literature and the writings of prominent foresters. We explore how these foundations can contribute to limiting considerations for diverse worldviews and values and impede the discipline’s utility in combating climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental injustice. To overcome these limitations and make forestry a more diverse and inviting field capable of addressing 21st century challenges, we propose revising these foundations based on relational thinking and suggest ways such a shift in the institution of forestry could be facilitated. We argue that these revised institutional foundations can make the discipline more open to diverse worldviews, more inviting to groups traditionally underrepresented in forestry, more trusted by the general public and better able to confront the challenges forests face under global change.

Key policy highlights

We identify a need for transformative change in the traditional paradigm of forest management.

We argue that forestry based on relational thinking can help achieve more just, inclusive and sustainable futures.

We suggest that supporting changes to university curriculum, professional standards and forest policies as well as incorporating relational values into sustainable forestry certification schemes and corporate social responsibility initiatives can facilitate institutional change in forestry.

EDITED BY:

Introduction

The discipline of forestry, in its dominant modern manifestation, was born in central Europe from a confluence of concerns about timber supply, industrialization and a disintegration of communal land rights in the 18th century (Bennett Citation2015). Experts leveraging natural science and economics to manage forests for the interests of the state and private landowners replaced traditional communal forest practices. Forestry has evolved in subsequent centuries in response to newer fields and changing societal expectations (Puettmann et al. Citation2009), but the discipline has largely remained an institution rooted in a distinctly Western worldview that frames forests as resources centrally managed for the satisfaction of human needs and preferences (Huntsinger and McCaffrey Citation1995; Puettmann et al. Citation2009; Bennett Citation2015). The institution of forestry refers to the conventions, norms and legal rules that influence decisions made by foresters and forest managers in their professional roles (Vatn Citation2020). Forestry has succeeded in meeting global demand for wood fiber that has kept pace with human population growth (Betts et al. Citation2021), but it faces new challenges in unprecedented climate change and biocultural diversity loss. We believe forestry is uniquely positioned to help address these challenges but to do so requires an institutional shift; a relational turn toward inclusivity of diverse worldviews and empowered latent relational values (‘values of meaningful and often reciprocal human relationships-beyond means to an end-with nature and among people through nature’ (Himes et al. Citation2024, p. 6)) to support more just and sustainable futures (Chan et al. Citation2020).

A key finding from the Intergovernmental Science Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) assessment of the diverse values and valuation of nature (Values Assessment) was that a narrow set of instrumental values (‘values of nature entities and other-than-human beings important as means to achieve human ends or satisfy human preferences’ Himes et al. Citation2024, p. 6) of nature have typically driven decisions that have contributed to over-exploitation of ecosystems and often ignore Indigenous peoples and local communities’ worldviews (Pascual et al. Citation2022). In environmental ethics and philosophy intrinsic values (‘values of entities expressed independently of any reference to people as valuers, including values associated with entities worth protecting as ends in and of themselves’ (Himes et al. Citation2024, p. 5)) of nature are presented as an alternative to instrumental values to justify protecting the environment (Batavia and Nelson Citation2017), but intrinsic values may fail to resonate with many people (Chan et al. Citation2016) and have been used in sometimes inconsistent and contradictory ways (O’Neill Citation1992).

Historically, the discipline of forestry has largely focused on the instrumental values of forests. Some trends in forestry have tentatively incorporated the intrinsic values associated with forests into practices (Batavia and Nelson Citation2016). However, considering only instrumental or intrinsic values fails to adequately account for the diverse ways forests are important to people (Pascual et al. Citation2023). Relational values have been suggested by environmental philosophers as an alternative to the traditional dichotomy of intrinsic and instrumental values that can better account for the diverse values of nature (Muraca Citation2011, Citation2016; Chan et al. Citation2016; Himes and Muraca Citation2018). In this paper, we propose a relational turn in forestry in which the institutional foundations of the discipline are expanded to more explicitly acknowledge the meaningful relationships between people and forests which can be constitutive of identity, essential to living a good and fulfilling life and are core to reciprocal relationships of responsibility, care and stewardship with forests. Our vision of a relational turn in forestry has roots in the philosophy of Whitehead (Muraca Citation2016), feminist care ethics (Jax et al. Citation2018), eudaemonia (Muraca Citation2011; Chan et al. Citation2016), and it is informed by recent work in sustainability and social sciences (e.g. Klain et al. Citation2017; Allen et al. Citation2018; West et al. Citation2018, Citation2020; Chapman et al. Citation2019, Citation2023; Gould et al. Citation2019, Citation2023).

In Section 1 of this paper, we identify four institutional foundations of forestry drawing from textbooks, histories, university curriculum, professional societies’ codes of ethics, policy documents, peer reviewed literature, and the writings of prominent foresters. These institutional foundations are as follows: 1) forests should be managed, 2) forests should be owned, 3) forest management should be based on science,Footnote1 and 4) forests are a means to satisfying human ends. We explain each of these foundations, provide evidence for their central role in the institution of forestry, identify their strengths and briefly highlight how they can have negative consequences for inclusion, justice and sustainability.

In Section 2, we describe a relational turn in forestry and suggest revised foundations that can facilitate an expansion of conventions and norms in forestry to better reflect changes in practices and ideas that have occurred in recent decades. These revised foundations are as follows: 1) care and respect for forests, 2) forests impact communities around them in profound and relational ways, 3) traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and other ways of knowing can complement science in determining forest practices, and 4) people have diverse values of and about forests. Throughout the paper, we refer to forestry based on these new institutional foundations as ‘relational forestry’, but we do not envision relational forest as a new ‘type’ of forestry or an alternative to ecological forestry, multifunctional forestry, or scientific forestry. Rather, we use relational forestry as a convenient shorthand to refer holistically to a vision for the broad discipline of forestry where relational perspectives and relational values are embraced and a wide range of practices, from intensive plantations to ecological restoration, are possible. We recognize that many foresters and organizations already embrace some of these foundations in their approaches to forest practices, but we argue that the prevailing culture of forestry has not yet done so. It is our opinion that these revised foundations preserve the strengths of forestry while promoting transformation toward an institution that is more just and sustainable.

In Section 3, we suggest specific approaches to facilitating a relational transformation in forestry. These include supporting changes to university curriculum, professional standards and forest policies. We also suggest that incorporating relational values into sustainable forestry certification schemes and corporate social responsibility initiatives can support an institutional shift toward relational forestry. We conclude with a summary of key messages and reflect on our motivations and aspirations in calling for a relational turn in forestry.

Section 1: four institutional foundations of forestry

The foundations we identify are informed by the authors’ collective decades of experience working in forest industry, research, and education in North America. In large part, they are a synthesis of critiques leveled at forestry in recent decades (e.g. Scott Citation1998; Guha Citation2000; Puettmann et al. Citation2009; Bennett Citation2015; Franklin et al. Citation2018), reevaluated through the lens of relational values. In identifying and articulating these foundations in forestry institutions, we rely heavily on documents from organizations that have a large influence on shaping the institution of forestry, such as professional societies, academic curricula, and government agencies. We did not conduct a systematic review of scientific literature (we believe this would bias the picture toward research perspectives), but we provide evidence from multiple sources supporting the prevalence of each of these foundations. Our experience and the literature we cite draws largely from North America, but we include evidence of these foundations in Europe and other parts of the world where forestry has been spread. These foundations are most closely aligned with what Guha (Citation2000) and Scott (Citation1998) refer to as ‘scientific forestry’, and Bennett (Citation2015) and Puettmann et al. (Citation2009) more generally describe in terms of the science and profession of forestry and forest management, which is primarily preoccupied with timber production. Forestry, in this context, first developed in Germany in the late 1700s, spread globally, often as part of colonial expansion and persists as a dominant paradigm of forest management today. We recognize the prominence of these institutional foundations varies across the globe and that some of the examples we include are specific to the North American context, but we believe these institutional foundations are rooted in the common origins of forestry and have been widely maintained, all be it some more visibly than others, through disciplinary hegemony and institutional inertia.

While the discipline of forestry has evolved and forest practices in many contexts have diverged from scientific forestry and expanded beyond a narrow focus on timber production (e.g. multi-objective/use forestry (i.a., Clawson Citation1977; Takala et al. Citation2019; Zhang et al. Citation2022) ecological forestry (i.a., Seymour and Hunter Citation1999; Hays Citation2007; Franklin et al. Citation2018), close-to-nature forestry/silviculture (i.a., Schultz Citation1999; Brang et al. Citation2014; O’Hara Citation2016), closer-to-nature forest management (Krumm et al. Citation2023), and continuous cover forestry (i.a., Pommerening and Murphy Citation2004; Vitkova and Dhubháin Citation2013; Mason et al. Citation2022)), we argue that these foundations are still prevalent in contemporary forestry practices, organizations, policy, and education and are part of contemporary hegemonic narratives of forestry (Takala et al. Citation2019). Articulating these institutional foundations and reimagining them is important because if left uninterrogated, there is a danger that such conceptual building blocks may undermine progress in the discipline of forestry or mask ongoing power inequities in forest policies and practices (Howitt and Suchet-Pearson, Citation2006). Further, while various trends in forestry have given increased attention to the diverse ecosystem services that forests provide and in a few cases argued for their intrinsic value (e.g. ‘Systematic Silviculture’ described by Ciancio and Nocentini (Citation1997)), they have not engaged with the relational values of forests, which are increasingly considered an essential component of nature’s contributions to people (Dıaz et al. Citation2015; Himes and Muraca Citation2018; Pascual et al. Citation2023).

We propose that a critical evaluation of these institutional foundations highlights how many modern practices and trends in forestry no longer align with them. However, the evidence we present suggests these institutional foundations persist, and their persistency, rather than being a benign vestigial, may hamper efforts to advance the inclusivity and capability of the forestry discipline. We suggest a concerted effort to expand these foundations to better reflect changes in forest practices and education over recent decades and to facilitate further advances in the discipline built around the diverse goods and services forest provide and the diverse ways people value forests.

Foundation 1. Forests should be managed

Management is a persistent, sometimes invisible, foundation concept imbedded in most development and conservation projects (Howitt and Suchet-Pearson, Citation2006), including forestry practices. Seminal forestry literature, policies, and professional association documents consistently define forestry, to one degree or another, as managing forests (e.g. Nieuwenhuis Citation2000; Helms Citation2002; Nyland Citation2016; Deal Citation2018). Managing forests implies that people control them (Pinchot Citation1947; Holling and Meffe Citation1996; Puettmann et al. Citation2009) and through control, plan and execute practices to achieve specific objectives (Bettinger et al. Citation2016; Deal Citation2018); managing forests assumes a linear, unidirectional, and controlled movement toward defined strategic outcomes that are implied or stated to be desirable (Howitt and Suchet-Pearson, Citation2006). While deep divides exist over appropriate models for forest management, e.g. between the agronomic model of production forestry and ecological models like relying on natural regeneration, both camps typically assert that the purpose of forestry is to manage forests (Reidel Citation1970; Franklin et al. Citation2018). Even the decision to ‘do nothing’ or in some cases prohibit forest practices in particular areas (e.g. wilderness) is conceived of as a top-down control on the landscape to achieve specified objectives (Duncker et al. Citation2012).

Further, we suggest that there is a pervasive normative position in forestry that forests should be managed. Gifford Pinchot, father of the US Forest Services, was explicit that managing forests was a moral imperative. He asserted that provisions which prohibited management (cutting trees) were ‘indefensible’ (p27), and that ‘right methods of forest management’ maintained or increased the production of trees for timber (p306) (Pinchot Citation1947). Similarly, the Society of American Foresters (SAF) contemporary code of ethics states that ‘foresters have a responsibility to manage land for both current and future generations’ (SAF Code Of Ethics, Citationn.d.). The intended emphasis may be on current and the future generations, but the explicit statement that foresters have a responsibility to manage the land as an ethical principle demonstrates it is a normative position; that managing forests isn’t just descriptive of what forestry is, it is also what ought to be done.

The institutional foundation that forests should be managed has contributed to the efficient supply of forest products for human consumption. The focus of management on flexible objectives enabled the adoption of new methodologies in response to changes in societal preferences. For instance, intensively managed plantation forests effectively supply timber but can also achieve other goals such as habitat and non-timber ecosystem services (Fox Citation2000; Paquette and Messier Citation2010). Despite these advantages, management limits appropriate relationships that people (especially foresters) have with forests to those in which people are separate from and exert control over the forest. Forest management and natural resource management, more broadly, frame people and nature according to a particular Eurocentric belief system (Howitt and Suchet-Pearson, Citation2006). The privileged position of the management paradigm in the discipline of forestry silences worldviews that embrace other ways of interacting with forests, e.g. relationships of care and kinship with forests and entities that live in them. For instance, management of forests may be at odds with some Indigenous worldviews that reject clear distinctions between humans and nature and emphasize reciprocal relationships and care (Anderson et al. Citation2022, Howitt and Suchet-Pearson, Citation2006; Jax et al. Citation2018). Similarly, ecocentric worldviews that imply a moral duty toward forests are not ethically compatible with asserting control over ecosystems (Batavia and Nelson Citation2016). Further, the level of control over forests assumed in a management model may be illusory in the face of wicked problems, like adaptation to climate change, preventing species extinctions and curbing forest loss and degradation (Ludwig, Citation2001). Assuming the results of management are linear and predictable can also lead to unintended forest decline (Holling and Meffe Citation1996).

Foundation 2. Forests should be owned

‘Forests should be owned’ means that they should be under centralized control and treated as property of private parties or an organized state (Rose Citation1986). The common perception during the early development of forestry was that wood supplies were dwindling because of exploitative and wasteful practices of the peasantry and the greedy (Warde Citation2018), and the emerging discipline of forestry could provide efficient solutions for optimal sustained production of timber based on principles of natural science, economics and mathematics (Lowood Citation1990). However, implementing forestry required investments in measuring, monitoring and treatments to regiment the forest. Such investments required access to capital, commitment to long-term planning and the power to enforce management plans (Scott Citation1998; Warde Citation2018). Forests held or managed as commons lacked the centralized authority thought to be necessary for enforcing long-term planning and the capital needed for monitoring and treatments, which helped justify state take-over of communal woods (Warde Citation2018). As a result, forest land in central Europe ended up being directly managed by the state, or title was transferred to private individuals to be managed for timber production by professional foresters (Warde Citation2018). This pattern was replicated throughout the world where colonial powers spread ‘scientific forestry’ (Huntsinger and McCaffrey Citation1995; Scott Citation1998; Guha Citation2000; Bennett Citation2015).

By the 19th century, centralized ownership was an ensconced foundation of forestry. While some notable community forestry examples persist throughout Europe thanks to resilient social institutions (Jeanrenaud Citation2001), most had been dissolved by the start of the 20th century (Scott Citation1998; Fernow Citation2015). Recently, there has been renewed interest in community forests, e.g. through the US Forest Service Community Forest Program and as evident by the global trend in decentralizing governance of forests (Agrawal et al. Citation2008). However, it is our opinion that centralized ownership has largely remained an institutional foundation of forestry and can get in the way of foresters constructively engaging in community-based forest governance. In parts of North America, this foundation is so ingrained that in the authors’ experience, it can be difficult to have a conversation about forestry without hearing the phrase, ‘landowner objectives’. For instance, many forestry students in the United States are taught landowner objectives are the primary basis for forest management and planning (Bettinger et al. Citation2016). Here again, the SAF code of ethics is informative; the second principle states, ‘society must respect forest landowners’ rights …’ (SAF Code Of Ethics, Citationn.d.).

While the specific extent of landowner rights varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, they typically empower landowners to make unilateral decisions with regard to forest practices, at least within certain legal constraints. The major advantage of treating forests as property with clearly designated owners is that it reduces conflicts over contested use and facilitates objective-based management strategies and planning that have proven efficiency in business settings (Bettinger et al. Citation2016). It is also often argued that expansive and clearly defined property rights are necessary to avoid overexploitation and inefficient use of forest resources (Stroup and Baden Citation1973), or ‘the tragedy of the commons’ (Hardin Citation1968). However, there have been many examples of successful community forests that contradict such concerns (Rose Citation1986; Feeny et al. Citation1990; Bray Citation2020; Bastida et al. Citation2021), and Ostrom’s theoretical work (Ostrom Citation1999, Citation2010) is often cited as an alternative to the tragedy of the commons. However, community systems can be fragile and require constant cooperation to succeed (Dasgupta Citation2021).

Despite the operational tractability of forest ownership, it is not a universally accepted premise for forest practices. For instance, the notion of forests as property to be owned is incongruous with some Indigenous worldviews (Noble Citation2008). As Dan Shilling describes, a common thread of Native American philosophy is that ‘to speak of an individual owning land is anathema, not unlike owning another person, akin to slavery’ (Shilling Citation2018, p. 12). Even if land ownership is not, itself, problematic, this foundation limits meaningful engagement of forestry with communal forests that are central to how people in many parts of the world have interacted sustainably with forests historically (Johann Citation2007; Parrotta et al. Citation2009; Guadilla-Sáez et al. Citation2020).

Foundation 3. Forest management should be based on science

The emphasis on science as a basis for management strategies is pervasive in forest policy around the world. For instance, Canada, the European Union, and Australia all have some variation of scientific management explicitly written into their policies governing forestry (National Forest Policy Statement Citation1992; Canada Citation2015; Forestry Explained Citation2023). The Chinese Ministry of Forestry also emphasizes that forest planning and operations should be based on science (Wang et al. Citation2004). One of the US Forest Service’s 13 guiding principles states, ‘[w]e use the best scientific knowledge in making decisions and select the most appropriate technologies in the management of resources’ (What We Believe Citation2016). Beyond government policy, the SAF code of ethics states that ‘[s]ound science is the foundation of the forestry profession’ (SAF Code Of Ethics, Citationn.d.).

In many cases, it is legally required that those who prescribe forest practices have official training and maintain professional, science-based certification (e.g. in Mississippi, USA, it is illegal to practice forestry or refer to yourself as a forester unless you have a license that verifies you are ‘a person who by reason of his knowledge of the natural sciences, mathematics, economics and the principles of forestry and by his demonstrated skills acquired through professional forestry education … is qualified to engage in the practice of forestry …’ (Mississippi Board of Registration for Foresters Citation1977)). Having a degree from an accredited higher education institute with sufficient science training is usually a prerequisite to such certification. A prominent example in North America is the SAF accreditation process that certifies university forestry curricula and individual professionals (SAF Society of American Foresters Citation2021).

One of the major benefits of this foundation is that it provides an empirical basis for management and helps to ensure consistency and standards in forestry practices. However, only recognizing science as a legitimate knowledge system can exclude other worldviews and limit diversity in forestry. In recent years, there have been attempts to integrate Indigenous perspectives with sciences in university curriculum (Verma et al. Citation2016). However, historically other types of knowledge have been rejected in favor of scientific perspectives (Snively and Corsiglia Citation2001). Specifically, in Canada, First Nations’ perspectives have often been excluded in favor of scientifically established management (Willems-Braun Citation1996; Smith and Ross Citation2002; Wyatt Citation2008). Similar examples of rejecting local and Indigenous knowledge, often to the detriment of communities and ecosystems, can be found in Mexico (Sierra-Huelsz et al. Citation2020), Indonesia (Ellen et al. Citation2000), and India (Baviskar Citation1994; Ellen et al. Citation2000).

Foundation 4. Forests are means to satisfying human ends

Modern forestry was invented to satisfy human demand for timber (Scott Citation1998; Puettmann et al. Citation2009; Bennett Citation2015). Through time, the specific aims of forestry have broadened beyond timber but remain firmly planted in satisfying human needs and preferences. Forest policies around the world emphasize the role of forestry is to satisfy human needs and preferences, usually through the theme of sustaining forest production and value for current and future generations of people (e.g. National Forest Policy Statement Citation1992; Canada Citation2015; European Commission, Directorate General for Communication Citation2021). The mission of the US Forest Service is ‘to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations’ (What We Believe Citation2016), and the first principle of the SAF code of ethics concludes with a pledge to, ‘practice and advocate management that will maintain the long-term capacity of the land to provide the variety of materials, uses, and values desired by landowners and society’ (SAF Code Of Ethics, Citationn.d.). Franklin et al. (Citation2018) outlines tenets of faith for both production-oriented forest and ecological forestry that emphasize managing forests for human benefits.

Provisioning human needs now and in the future is a necessary and admirable goal. Forestry may have been the first sustainability science; because of the long-lived and slow growing nature of trees, foresters have always taken a long-term outlook. However, the emphasis of sustainability in forestry is historically focused on the provisioning of goods for human benefit. What is lacking is the room for non-instrumental values, such as the intrinsic value some people assign to forests, or the relational values derived from meaningful relationships people have with and in forests (Himes and Muraca Citation2018). A narrow focus on satisfying human needs also ignores non-anthropocentric worldviews that consider other life forms or ecosystems worthy of deep consideration (Raymond et al. Citation2023).

These four foundations are intertwined and overlap. For instance, that forests should be managed usually implies they should be managed to satisfy preferences and needs of people, specifically the people who own them. Rather than being considered entirely independent, we view these four institutional foundations of forestry collectively as the basis for many conventions and norms of the discipline. Importantly, there are communities within forestry, as well as individual foresters, who disagree with these foundations. Specifically, many foresters, forestry organizations and some scholars explicitly recognize the intrinsic value of forests beyond their ability to satisfy human preferences (e.g. Bengston Citation1994; Ciancio and Nocentini Citation1997; Batavia and Nelson Citation2017) and adopt a more biocentric or ecocentric ethic (e.g. Coufal Citation1989; Rolston and Coufal Citation1991; Nocentini et al. Citation2021). Others in the forestry community have been strong proponents for other kinds of knowledge in addition to science (Robinson and Ross Citation1997). However, such views have often conflicted with mainstream perspectives (Evans and Clark Citation2017; Carey Citation2019), and management of forests still routinely lacks integration of TEK or other ways of knowing. The thrust of this paper is to join these other voices and encourage the evolution of forestry’s institutional foundations with the goal of being more inclusive and better equipped to address the challenges of global change.

Section 2: a relational turn in forestry

A relational turn in forestry is an evolution toward a vision of forests as complexes of dynamic and constitutive relationships. This includes ecological relationships (the movement and transformation of matter and energy through the forest ecosystem), social relationships (connections between people), spiritual relationships (people’s sense of awe and sacredness toward the forest), care relationships (stewardship of natural resources and reciprocal relationships between humans and non-humans), material relationships (goods derived from forests to meet material needs and preferences) and interactions between them (the diverse ways that people interact with and intercede in the ecology of a forest). Accepting that these manifold relationships are essential to what makes a forest a forest requires rejecting real distinctions between the ecological and social in favor of understanding forests holistically as composed of continuous encounters, interactions and interpretations (West et al. Citation2020). This includes challenging dichotomies that frame forests in the light of contrasting discrete categories such as human/nature, producer/consumer, intrinsic/instrumental, social/ecological and managed/wilderness. In relational forestry, the importance of a tree visited frequently as part of a family tradition, the shelter the same tree provides to a squirrel and the monetary value of the lumber that could be milled from it are all real, essential and inexorable parts of the forest. These things represent relationships that are meaningful in material, emotional or spiritual ways, and they are as integral to the forest’s being as the physical parameters included in a forest inventory.

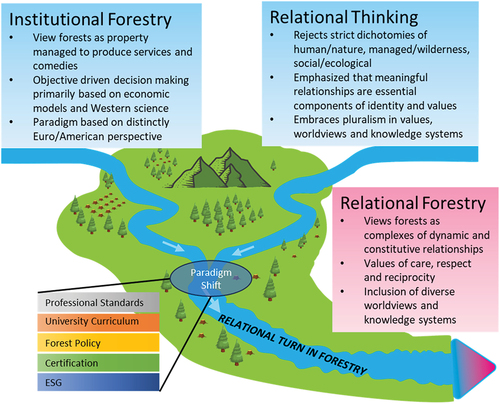

A relational turn in forestry is not a rejection of current practices. Rather, we imagine the relational turn in forestry to be like the bend in a river where two major tributaries, forestry, and relational thinking, join and transform into a deeper and broader channel (see ). Old modes of operation are still possible but take on new facets. For example, production forestry following an agricultural model is reinterpreted as one of many relationships between society and land growing trees. Production-oriented practices can still be supported, but a wider range of considerations are attended. Setting management objectives for the forest is intentionally narrowing the type of relationships under consideration, which may be necessary or prudent, but in relational forestry when such simplifications are made there is acknowledgement of what is being left out and a reflexive accounting for why, what is lost and the power dynamics involved (Gould et al. Citation2024).

Figure 1. A simplified depiction of a relational turn in forestry. The dominant institution of forestry is rooted in and continues to be based on principles that frame forests as property to be managed for satisfaction of human preferences. An infusion of relational thinking into forestry, facilitated by changes in professional standards, university curriculum accreditation, the language used in forest policy, sustainable forestry certification criteria, and corporate environmental sustainability governance (ESG) efforts could lead to a paradigm shift toward Relational Forestry. We argue that such a shift would preserve the traditional strengths of forestry while making it more just, inclusive, and better equipped to tackle 21st century challenges. This figure is an adaptation from West et al. (Citation2020).

Our observation is that most foresters experience forests as more than a series of biophysical components or timber growing factories. Being a good steward, working in the woods and being a ‘forester’ are often important components of a forester’s identity, as has been shown for natural resource professionals like farmers (Chapman et al. Citation2019; Chapman and Deplazes-Zemp Citation2023) and fishers (Kaltenborn et al. Citation2017). In fact, we suspect that relational values of forests are the primary motivation for many people who choose to pursue careers in forestry. Most foresters we know would express a deep sense of loss if they had to pursue a career outside the forest, even if compensation and benefits were equivalent or greater. The relationship between foresters and forests, we suggest, is meaningful, often constitutive of the forester’s identity and cannot, in principle, be substituted. Through these relational values, foresters experience and understand forests in a relational way.

However, the rules and norms that govern the practice and discipline of forestry impose a substantialist understanding of forests and create barriers to acting upon relational values. For example, requiring decisions about forest practices to be based on considerations of forests’ ability to produce things to satisfy human needs and preferences, as in foundation 4, encourage production optimization of goods and services (Stoddard Citation1959; Assmann Citation1970) which can minimize considerations of care, reciprocity, awe or spiritual connection people hold toward the forest (Odok Citation2019; Coelho-Junior et al. Citation2021; Yuliani et al. Citation2022). Limiting the realm of possible practices to those which improve production of a desired good or service is often justified as basing management decisions on science, as articulated in foundation 3. However, science is not politically or value neutral, and it is increasingly recognized that it is not possible for science to generate unequivocal and uncontested knowledge, leading to the ‘right’ forest practices (Giller et al. Citation2008). Increased understanding of a forest through science only provides information about potential consequences of particular practices, but the choice about the ‘right’ way to practice forestry is loaded with diverse values that are negotiated by practitioners, managers and society rarely ascribing to a singular worldview. The decision to ‘manage’ forests (foundation 2), rather than care for forests, protect forests or enrich forests implies that a limited set of those diverse values will be prioritized, namely, the instrumental benefits that forests provide which can be quantified and enumerated in scientific language. Further, when the outcomes of forest practices are measured against objectives and what objectives are relevant is determined through property ownership (foundation 1), the impacts of practices on other relationships that constitute the forest are at risk of falling by the wayside (Dorries Citation2022).

For a relational turn in forestry to happen, we believe the four institutional foundations discussed above must be modified. Here, we propose new foundations based on relational perspectives that elevate the relational values of forests. We draw some inspiration from the examples of more relational forestry practices and seek to modify the old foundations to mitigate potential negative consequences without dampening the strengths of forestry.

Foundation 1 of relational forestry: care and respect for forests

We advocate for a shift in the dominant perspective of controlling forests through management to viewing them as deserving of care and respect (Martinez Citation2018). Such a change opens forestry to more worldviews, such as those that do not view humans and nature as distinct (Anderson et al. Citation2022) and those that don’t limit moral agency to human beings (Pierotti and Wildcat Citation2000; Nelson and Vucetich Citation2018). We suggest, as others before us, that care and respect are a stronger foundation for sustainability than management based on exerting dominance and controlling ecosystems (Martinez Citation2018; McGregor Citation2018).

Practically, the adoption of this institutional foundation means asking different questions. Under a management approach a forester asks what the objectives are and sets out to achieve them; under a relational approach, the question becomes can we care for and nurture forests so that we can in turn be nurtured by the diverse goods, services and values forests provide. Similar to the way that basing interpersonal relationships, like marriage, on achieving objectives can create tension, we suggest that object driven forest practices may only be appropriate for a narrowly defined range of human/forest relationships. In recognizing that forests are constituted of a complex of continuously unfolding relationships, care and respect for forests implies that we consider the impact of forest practices on those myriad relationships. It is still reasonable to care for a forest in a way that it produces timber for harvest, although the range of impacts considered in a harvest will likely be more broad. Decisions are less likely to be made based on efficiency or maximizing objective functions and more likely to be made with deep and conservative concern about how forest practices will affect the wellbeing of the forest and all things that share relationships in it or with it. Shifting from management to care may also make forestry more inviting to traditionally marginalized groups who have historically adopted relational ways of thinking and have experienced oppression through similar constructs of control and domination implied by the language of management, e.g. women, Indigenous peoples and people of color (Fairfax and Fortmann Citation1990; McGregor Citation2018; Dorries Citation2022).

Foundation 2 of relational forestry: forests impact communities around them in profound and relational ways

This foundation is suggested as an alternative to owning forests. While there are rich philosophical and legal debates about the nature of property and ownership, Graeber and Wengron articulate two common characteristics of property (Citation2021): 1) an owner has the power of complete dominion over their property, save what is limited by ‘force of law’, which includes the power to destroy or enact arbitrary violence against their property; 2) to own property you must be able to exclude others from accessing, using or benefiting from it. If forests are considered holistically as a complex of dynamic and constitutive relationships, then owning a forest is not feasible by these standards. Certainly, a person can exclude others from the financial benefits of cutting trees and selling timber, but it is untenable to fully capture the positive ‘externalities’ of forests; benefits like stormwater interception, carbon storage, the beauty of a forested ridgeline glimpsed from the highway or the sense of awe a forest instills in a passerby can’t reasonably be kept from others. We concede that private ownership of forest components is reasonable, but it is difficult and problematic to impose ownership holistically on forests if you accept a relational view. In other words, you can own timber, but you can’t own the forest.

As an alternative, we suggest an institutional foundation that recognizes how forests impact communities around them in profound and relational ways. This foundation doesn’t exclude legal owners or custodians of the land from seeking self-interested benefits from the forest, but it does not give primacy to a relationship of domination in determining forest practices. Moreover, it is an explicit recognition that there are relationships between people and forests that transcend private ownership, such as a local community’s shared viewscape. Most foresters already consider the impacts that their actions will have on local communities and the environment, but ignoring the impact of forest practices on others in the singular pursuit of landowner objectives, particularly timber production objectives, has been at the root of many forest use conflicts and undesirable trade-offs in biodiversity and ecosystem services (Huntsinger and McCaffrey Citation1995; Guha Citation2000; Paillet et al. Citation2010; Raymond et al. Citation2023). We believe a shift toward active consideration of the impact forest practices will have on the broader community can help reduce these types of conflicts and trade-offs. In some cases, there are mandates requiring foresters to take into consideration impacts on the broader community, e.g. in the management of US Forest Service land. We believe foresters working under these mandates would be better prepared if consideration for broader impacts of forest practices on communities was more explicitly foundational to the discipline. Further, shifting emphasis to include forestry impacts on others, besides landowners, can minimize the existing dissonance between forestry and some Indigenous worldviews and make the discipline more compatible with communal forests. Making this shift will also help better align the discipline of forestry with the trend in global forest governance away from centralized control and toward community forests (Agrawal et al. Citation2008). Making this transition may be helped by embracing lessons learned in regions and countries that have turned toward community forestry in recent decades, like Nepal (Paudyal et al. Citation2017).

Foundation 3 of relational forestry: traditional ecological knowledge and other ways of knowing can complement science in determining forest practices

Science has provided great advances in forest yield, ecology, sustainability and management. However, the importance of other ways of knowing, like TEK, to natural resources management has been formally recognized by international organizations and governments for decades (e.g. the Rio Declaration and the Convention on Biodiversity (Cheveau et al. Citation2008)). While some forestry-specific entities, such as the Forest Stewardship Council explicitly encourage consideration of TEK in forestry (FSC Citation2023) and some universities have incorporated TEK into forestry programs, there are still many forestry curricula, private companies, and forest agencies that insist forestry decisions should be made based entirely or predominately on science. When and where TEK or other ways of knowing are considered, they are often constraints or complements to forestry but not part of it.

We suggest broadening the types of knowledge that are considered appropriate and legitimate for making decisions about forests. While many forest agencies and forest management texts emphasize the imperative to base forest practices on science, there is a long history of considering other types of knowledge in mainstream forestry: namely in the practice of silviculture. The Society of American Foresters (Deal Citation2018), text books (Nyland Citation2016; Palik et al. Citation2020), and some agency definitions (USFS, Citation2014) define silviculture, a central subdiscipline of forestry, as ‘art and science’. What constitutes the ‘art’ of silviculture is usually left vague but can refer to the experiential knowledge derived from practice which can be passed from generation to generation (Jain Citation2013). It may be useful for foresters engaged in practicing a relational turn in forestry to consider TEK and other ways of knowing like the ‘art’ of silviculture and to emphasize similarities between science and TEK, such as both employ observation, logic, and authority to create knowledge (Tsuji and Ho Citation2002). However, in saying that TEK can be a compliment to science or that it has parallels to silviculture, it is important to recognize that traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples should be engaged with respect and in collaboration with knowledge holders. Indigenous communities are self-determining nations with knowledge sovereignty, engaging in their own research programs and priorities, they are not ‘stakeholders’ (Latulippe and Klenk Citation2020). Indigenous knowledge is not merely supplemental information for science but is a legitimate form of knowledge for planning and decision-making in its own right (Whyte Citation2018).

Broadening forestry to be more inclusive of diverse ways of knowing can help make the discipline more inviting and lead to innovative practices. The current emphasis on science can be off-putting to people with different worldview, for example Indigenous people who may view it as ‘inaccessible and culturally irrelevant’ (Snively and Williams Citation2006, p. 230). Historically, ignoring or diminishing other ways of knowing in favor of managing forests based on science has resulted in injustices toward marginalized communities and, in some cases, practices that would be considered unsustainable because of their detrimental impacts on biodiversity (Huntsinger and McCaffrey Citation1995; Guha Citation2000; Cheveau et al. Citation2008; Nikolakis and Nelson Citation2015). There is also ample evidence suggesting other ways of knowing, like TEK, can offer new approaches and practices to natural resource management that are more sustainable and resilient to global change (Herrmann and Torri Citation2009; Burkett Citation2013; Kim et al. Citation2017; Hosen et al. Citation2020; Minahan Citation2023). Relational forestry seeks to legitimize other ways of knowing in forestry to reduce the likelihood that such injustices and degradation continue, make the discipline more inviting to a diversity of people and encourage diverse practices to address the rapidly emerging challenges of global change.

Foundation 4 of relational forestry: people have diverse values of and about forests

The institution of forestry, at its core, is about sustainably producing goods and services for the benefit of people, i.e. forests are a means to satisfy human ends. This means to an end framing reflects the instrumental value of forests to people, but insofar as forests are only considered means to human ends, other types of values associated with forests are trivialized or ignored. For instance, wilderness and old-growth forests in North America are considered by many to have intrinsic values, meaning that they are considered important for their own sake, regardless of the instrumental benefits they could provide people (Proctor Citation1995). However, in the case of US wilderness, its very definition specifying that it be ‘untrammeled by man’ is predicated on the absence of practicing forestry. Similarly, in the case of old growth, protecting its intrinsic values usually means excluding forest management (Proctor Citation1995). This reflects a long-held dichotomy in environmental philosophy that something has either intrinsic or instrumental value but can’t sustain both (Himes and Muraca Citation2018). Some scholars have tried to incorporate consideration for the intrinsic values of forests into forestry (Franklin et al. Citation2018), and pushed for a forestry ethic based on intrinsic value, seeing it as compatible with some forest practices (Batavia and Nelson Citation2016). However, scholars embracing relational perspectives reject the dichotomy of intrinsic and instrumental values in favor of value pluralism, which recognizes that forests have intrinsic, instrumental and relational values (Himes and Muraca Citation2018). Others suggest that focusing on a single value type at the exclusion of others is a major contributing factor to biodiversity loss (Pascual et al. Citation2022) and can result in unnecessary trade-offs in forest management (Himes et al. Citation2020). It is in the vein of value pluralism that we suggest shifting the emphasis in forestry from focusing on a single value type (instrumental) to explicitly considering a plurality of values. We have previously articulated that many foresters already value forests relationally, and the growth in adoption of ecological forest management and similar trends is a promising indicator that many practitioners may attribute intrinsic values to forests. Relational forestry would seek to embrace the instrumental, relational, and intrinsic values of forests.

Empowering decision-making based on these other types of values is a key leverage point for transformational changes in forestry to achieve sustainability goals (Chan et al. Citation2020). Thus, a relational turn in forestry would seek to resist and remove institutional mechanisms that prioritize instrumental value outcomes at the expense of other types of values (Spash and Vatn Citation2006; Spash and Aslaksen Citation2015). Importantly, recognizing diverse values does not minimize instrumental values of forests (Himes et al. Citation2024), and many practices developed around forests as means to human ends will still be relevant. Rather, a relational turn in forestry will make other values derived from forests more visible and ensure they are considered alongside instrumental benefits (Raymond et al. Citation2023).

We believe adopting, as an institutional foundation, that people have diverse values of and about forests could mitigate conflicts over forest practices. Such conflicts often happen when one party or group prioritizes the instrumental values of a forest and another insists on their intrinsic value (Proctor Citation1995). When viewed as an either/or dichotomy, the clash of value types leads to an impasse (Gould et al. Citation2024), but considering a plurality of values when determining forest practices may lead to compromise or elimination of unacceptable options (Himes et al. Citation2024). Further, considering relational values provides opportunities for conflicted parties to find common ground that does not exist in an either/or paradigm of intrinsic and instrumental values (Raymond et al. Citation2023).

Section 3: realizing a sustainable turn in forestry

Transformations toward a more just and sustainable future require addressing indirect drivers of change, including institutions (Chan et al. Citation2020). We have articulated four institutional foundations of forestry and suggest changes to these foundations that we believe could lead to a transformation of forestry toward supporting a more just and sustainable future. We turn now to suggesting specific approaches that can contribute, and in some cases already are, to the transformation of forestry’s institutional foundations. Our suggestions are based on our personal experiences, largely from North America, and informed by the examples we cite. The goal of these suggestions is to provide concrete advice on where we believe focused efforts could facilitate the relational turn in forestry. Some of these strategies are already being implemented to varying degrees and should be celebrated and their wider adoption encouraged. We invite others to expand and critique our list of suggestions and engage in empirical work to support or refute the efficacy of these suggestions.

Change university curriculum accreditation and standards

The shared history of forest science originating in central Europe has contributed to relative uniformity in forestry curriculum at the university level. This has been reinforced through national associations (e.g. National Association of University Forest Resources Programs; naufrp.org), professional society accreditation schemes (e.g. SAF Accreditation) and international organizations with significant engagement of forestry university faculty (e.g. IUFRO). Many forester positions require four-year degrees (e.g. Series 0460 positions in the US Forest Services) and having common curriculum requirements is essential to ensuring that foresters have the necessary knowledge and skills to perform a job. Curriculum standards, both within an institution and shared across institutions for accreditation, reinforce conventions, norms, and assumptions in the field. Historically, accreditation requirements have reinforced the four institutional foundations of forestry, but they could be modified to accommodate the foundations of relational forestry. For instance, programs could be required to teach the legitimacy of TEK alongside science or have modules on community forestry to complement traditional forest management approaches. Such classes are already part of forestry curriculum at some universities, but many forestry programs, particularly in the US, still lack such classes or they are only offered as electives. More formally incorporating relational thinking into curriculum standards and education requirements, where they are lacking, has the potential to encourage rapid changes across multiple institutions. Institutions where TEK, community forestry, complexity science and relational thinking are already being taught to forestry students can serve as examples and help guide implementation at other universities.

Change professional standards

Professional standards are common in forestry as part of professional societies and government licensure programs. As such, agreeing to conform to professional standards can be a requirement to conduct forest practices in many jurisdictions or represent a voluntary code of conduct followed by people who consider themselves ‘foresters’. Such standards provide practical and ethical guidelines but also literally spell out the norms and standards of the profession. As such, they present an opportunity for expanding the institution of forestry to be more open to relational thinking. For instance, Forest Professionals British Columbia’s Forest Stewardship Principles recognizes Indigenous, cultural, and traditional knowledge in addition to scientific knowledge as basis for understanding ecological systems and making decisions about forest practices (Association of BC Forest Professionals Citation2021). Modifying other government and organization guidelines to make space for or explicitly endorse the institutional foundations of relational forestry could facilitate a relational turn in the discipline.

Amend forest policy

Governments directly control and manage a large portion of global forests and issue guidelines or regulations for practices on private forests in many jurisdictions. As such, the language used in forest policies, laws and guidelines (e.g. voluntary ‘best management practices’ for forests on private land) set and reinforce the conventions, norms and legal requirements of practicing forestry. Often the language of such policies (intentionally or unintentionally) prioritizes specific worldviews and approaches to forest management, for example, in asserting that forest practices must be based on science or a limited set of values (e.g. instrumental cost–benefit analysis). Lobbying to create or modify forest policies that embrace, or at least do not exclude, relational approaches to forest practices can remove barriers to relational forestry. For example, as reported by Mattijssen et al. (Citation2020), the Dutch government recently began a strategic initiative which explicitly recognizes a plurality of values from forests, including relational values: ‘…forest also has a relational value. Trees give meaning to our life and contribute to our cultural identity’ (Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit Citation2020, p. 3). Adopting similar policy language broadly supporting the foundations of relational forestry in other jurisdictions would support institutional change.

Incorporate relational values into sustainable forestry certification criteria and indicators

Enrollment in voluntary forest certification programs has increased substantially in the last 30 years. Demand for sustainable forest management recognized by a certifying body (e.g. Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI), or the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC)), is driven by many factors; companies, governments and forest products manufacturers want to ensure consumers and the public that their operations are environmentally friendly, they want to reduce risk of social or legal missteps, and certification can increase market access (Moore et al. Citation2012). These forest certification programs have specific standards that must be met and verified by third-party auditors (Gutierrez Garzon et al. Citation2020). Because such a large area of working forests is enrolled in these certification programs, they significantly influence forest practice and the way practitioners approach the discipline. Most certification schemes include indicators for social, economic and environmental sustainability. In some cases, certification already accounts for aspects of relational forestry. For example, the FSC National Forest Stewardship Standards of Canada acknowledge local experts and traditional knowledge, in addition to science-based sources, as legitimate sources for identifying critical habitat (FSC Citation2018). Certification requirements are regularly reviewed and updated, providing an entry point for introducing or revising standards and indicators to support relational forestry more explicitly.

Appeal to corporate social responsibility initiatives

Timber investment management organizations (TIMOs), publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs) and forest products companies conduct a large portion of forest practices worldwide. These types of entities are all responsible to investors who are increasingly demanding greater levels of corporate social responsibility. As a result, there is increasing emphasis on environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting to increase transparency and promote corporate sustainability (Klinger et al. Citation2022). In Europe, ESG reporting may be legally required for some of these companies (EU Citation2022). We believe that ESG and sustainability reporting provide an opportunity for companies to advance relational forestry. The relational turn in sustainability is likely to impact public perceptions and expectations regarding standards for sustainable corporate behavior. Thus, companies may be inclined to consider relational forestry in their internal and published assessments of ESG and sustainability reports, which could motivate them to also put those principles into practice. We believe there is a potential synergy between ESG and relational forestry, particularly since relational values have been shown to resonate broadly with diverse groups of people (Klain et al. Citation2017). Embracing these values would provide companies with an opportunity to tap into a largely unexplored dimension of public acceptance.

Conclusion

The four institutional foundations of forestry we identified arose from a confluence of political, technological and scientific movements in 18th century Europe. These foundations have contributed to the success and spread of forestry. However, they have also contributed to the exclusion of some people and worldviews from fully engaging with the discipline. In the worst cases, these foundations have led to environmental injustices and contributed to declining forest resilience. These shortcomings have contributed to an erosion in public trust of forestry and forester’s social license to operate. Despite these occasional shortcomings, we feel strongly that the discipline of forestry, as the oldest sustainability science, can help lead the way to more sustainable and just futures. However, to face the challenges of global change, we believe it is more important than ever to have open engagement, collaboration, sharing, cross-fertilization of ideas, rediscovery of traditional practices and creation of new solutions for living sustainably with our forests. For this to happen, we believe it is critical that forestry undergo an institutional transformation. To that end, we have proposed revised institutional foundations of forestry based on relational thinking. These revised foundations are based on care, respect, consideration for community, diverse ways of knowing and a plurality of values form the basis of relational forestry. A relational shift in the institution of forestry could be facilitated by changing university curriculum requirements for accreditation, revising the language of professional standards and forest policies, embracing relational values in sustainable forest management certification criteria and indicators and addressing relational values in corporate responsibility reporting. Of course, forestry is nested within larger institutions which may still pose barriers to change. Despite these challenges, it is our aspiration in calling for a relational turn in forestry that the discipline will become more inclusive, diverse and creative. We invite others to explore the viability of our proposal and how it may be received by forestry professionals through empirical studies. We encourage discussion of our proposal and modifications or alternatives based on theory, science, traditional knowledge and experience of other researchers, foresters and practitioners. We envision relational forestry as fertile ground for growing solutions to climate change, invasive species, biodiversity loss, deforestation and demand for forest products born from the melding of forest science, TEK and other ways of knowing that support a plurality of values. Further, through relational forestry, we hope to grow our profession and make it more attractive, open and inviting to people and communities that have traditionally been poorly represented in the forestry community.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the guest editors of the special issue on a relational turn in sustainability, especially Simon West who encourages us to adapt a figure from West et al. Citation2022. We also want to acknowledge Max Schrimpf who helped design the figure. This work was part of a Directed Individual Study course in the Department of Forestry and Mississippi State University and is a contribution of the Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University. We would also like to thank the peer reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We use science throughout to specifically refer to the conceptualization of science developed in and conforming to the ‘Western’ tradition rooted in philosophy which was developed largely in western Europe and later North America and other places. We argue that the reference to ‘science’ in the context of forest management mostly refers to this tradition and is not typically inclusive of Indigenous knowledge, which some have argued should be considered science (Snively and Corsiglia Citation2001).

References

- Agrawal A, Chhatre A, Hardin R. 2008. Changing governance of the World’s forests. Science. 320(5882):1460–17. doi: 10.1126/science.1155369.

- Allen KE, Quinn CE, English C, Quinn JE. 2018. Relational values in agroecosystem governance. Curr Opin Sust. 35:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.026.

- Anderson CB, Athayde S, Raymond CM, Vatn A, Arias-Arévalo P, Gould RK, Kenter J, Muraca B, Sachdeva S, Samakov A, et al. 2022. Chapter 2. Conceptualizing the diverse values of nature and their contributions to people. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.7154713.

- Assmann E. 1970. The Principles of Forest Yield Study [Waldertragskunde]. Gardiner SH, translator. Munchen, Germany: BLV Verlagsgesellshaft.

- Association of BC Forest Professionals. 2021. Code of ethical and professional conduct: guidelines for interpretation; [accessed 2023 Sept 9]. https://www.fpbc.ca/practice-resources/standards-practice-guidelines/standards-of-ethical-professional-conduct/.

- Bastida M, Vaquero García A, Vázquez Taín MÁ. 2021. A new life for forest resources: the commons as a driver for economic sustainable development—a case study from galicia. Land. 10(2):99. Article 2. doi: 10.3390/land10020099.

- Batavia C, Nelson MP. 2016. Conceptual ambiguities and practical challenges of ecological forestry: a critical review. J For. 114(5):572–581. doi: 10.5849/jof.15-103.

- Batavia C, Nelson MP. 2017. For goodness sake! What is intrinsic value and why should we care? Biol Conserv. 209:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.03.003.

- Baviskar A. 1994. Fate of the forest: conservation and tribal rights. Econ Polit Weekly. 29(38):2493–2501.

- Bengston DN. 1994. Changing forest values and ecosystem management. Soc Natur Resour. 7(6):515–533. doi: 10.1080/08941929409380885.

- Bennett BM. 2015. Plantations and protected areas: a global history of forest management. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT Press.

- Bettinger P, Boston K, Siry JP, Grebner DL. 2016. Forest management and planning. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Academic press.

- Betts MG, Phalan BT, Wolf C, Baker SC, Messier C, Puettmann KJ, Green R, Harris SH, Edwards DP, Lindenmayer DB, et al. 2021. Producing wood at least cost to biodiversity: integrating triad and sharing–sparing approaches to inform forest landscape management. Biol Rev. 96(4):1301–1317. doi: 10.1111/brv.12703.

- Brang P, Spathelf P, Larsen JB, Bauhus J, Boncčìna A, Chauvin C, Drössler L, García-Güemes C, Heiri C, Kerr G, et al. 2014. Suitability of close-to-nature silviculture for adapting temperate European forests to climate change. Forestry: An Int J For Res. 87(4):492–503. doi: 10.1093/forestry/cpu018.

- Bray DB. 2020. Mexico’s community forest enterprises: success on the commons and the seeds of a good anthropocene. Tuscon, Arizona, USA: University of Arizona Press.

- Burkett M. 2013. Indigenous environmental knowledge and climate change adaptation (SSRN scholarly paper 2385397). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2385397.

- Canada NR. 2015. Forest management planning. Natural Resources Canada. https://natural-resources.canada.ca/our-natural-resources/forests/sustainable-forest-management/forest-management-planning/17493.

- Carey H. 2019. Early history of the forest Stewards Guild; [accessed 2023 Sept 9]. https://foreststewardsguild.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/EarlyGuildHistory_byCarey.pdf;.

- Chan KM, Balvanera P, Benessaiah K, Chapman M, Díaz S, Gómez-Baggethun E, Gould R, Hannahs N, Jax K, Klain S, & others. 2016. Opinion: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113(6):1462–1465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525002113.

- Chan KM, Boyd DR, Gould RK, Jetzkowitz J, Liu J, Muraca B, Naidoo R, Olmsted P, Satterfield T, Selomane O, et al. 2020. Levers and leverage points for pathways to sustainability. People Nat. 2(3):693–717. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10124.

- Chapman M, Deplazes-Zemp A. 2023. ‘I owe it to the animals’: the bidirectionality of Swiss alpine farmers’ relational values. People Nat. 5(1):147–161. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10415.

- Chapman M, Satterfield T, Chan KMA. 2019. When value conflicts are barriers: can relational values help explain farmer participation in conservation incentive programs? Land Use Pol. 82:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.017.

- Cheveau M, Imbeau L, Drapeau P, Bélanger L. 2008. Current status and future directions of traditional ecological knowledge in forest management: a review. The Forestry Chronicle. 84(2):231–243. doi: 10.5558/tfc84231-2.

- Ciancio O, Nocentini S. 1997. The forest and man: the evolution of forestry thought from modern humanism to the culture of complexity. Systemic silviculture and management on natural bases. The forest and man. Firenze, Italy: Accademia Italiana di Scienze Forestali; p. 21–114.

- Clawson M. 1977. The concept of multiple use forestry. Envtl. 8:281.

- Coelho-Junior MG, de Oliveira AL, da Silva-Neto EC, Castor-Neto TC, de Tavares AA, Basso VM, Turetta APD, Perkins PE, de Carvalho AG. 2021. Exploring plural values of ecosystem services: local peoples’ perceptions and implications for protected area management in the Atlantic forest of Brazil. Sustainabil. 13(3):1019. Article 3. doi: 10.3390/su13031019.

- Coufal JE. 1989. The land ethic question. J For. 87(6):22–24. doi: 10.1093/jof/87.6.22.

- Dasgupta P. 2021. The economics of biodiversity: the Dasgupta review: full report (updated: 18 February 2021). London, UK: HM Treasury.

- Deal R. 2018. Dictionary of forestry. Bethesda (MD): Society of American Foresters.

- Dıaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Larigauderie A, Adhikari JR, Arico S, Bilgin A. 2015. The IPBES conceptual framework—connecting nature and people. Curr Opin Sust. 14:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002.

- Dorries H. 2022. What is planning without property? Relational practices of being and belonging. Environ Plann D: Soc Space. 40(2):306–318. doi: 10.1177/02637758211068505.

- Duncker PS, Barreiro SM, Hengeveld GM, Lind T, Mason WL, Ambrozy S, Spiecker H. 2012. Classification of forest management approaches: a new conceptual framework and its applicability to European forestry. Ecol Soc. 17(4). doi: 10.5751/ES-05262-170451.

- Ellen RF, Parkes (Anthropologist) P, Bicker A. 2000. Indigenous environmental knowledge and its transformations: critical anthropological perspectives. London, UK: Psychology Press.

- EU. 2022. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European parliament and the council of 14 December 2022. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2464/oj.

- European Commission, Directorate General for Communication. 2021. Making sustainable use of our natural resources. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2775/706146.

- Evans AM, Clark FA. 2017. Putting the forest first. J For. 115(1):54–55. doi: 10.5849/jof.16-070.

- Fairfax SK, Fortmann L. 1990. American forestry professionalism in the third world: some preliminary observations. Popul Environ. 11(4):259–272. doi: 10.1007/BF01256459.

- Feeny D, Berkes F, McCay BJ, Acheson JM. 1990. The tragedy of the commons: twenty-two years later. Hum Ecol. 18(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00889070.

- Fernow BE. 2015. A brief history of forestry in Europe, the United States and other countries (EBook #48874). Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/48874/48874-h/48874-h.htm.

- Forestry explained. 2023. European commission. https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/sustainability/forestry/forestry-explained_en.

- Fox TR. 2000. Sustained productivity in intensively managed forest plantations. For Ecol Manage. 138(1–3):187–202. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00396-0.

- Franklin JF, Johnson KN, Johnson DL. 2018. Ecological forest management. Long Grove, Illinois, USA: Waveland Press.

- FSC. 2018. The FSC national forest Stewardship standard of Canada, forest Stewardship standards (FSS) V(1-0); [accessed 2023 Sept 9]. https://connect.fsc.org/document-centre/documents/resource/223.

- FSC. 2023. FSC principles and criteria for forest stewardship FSC-STD-01-001 V5-3; [accessed 2023 Sep 9]. https://connect.fsc.org/document-centre/documents/resource/392.

- Giller KE, Leeuwis C, Andersson JA, Andriesse W, Brouwer A, Frost P, Hebinck P, Heitkönig I, van Ittersum MK, Koning N, et al. 2008. Competing claims on natural resources: what role for science? Ecol Soc. 13(2): https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267992.

- Gould RK, Himes A, Anderson LM, Arias Arévalo P, Chapman M, Lenzi D, Muraca B, Tadaki M. 2024. Building on spash’s critiques of monetary valuation to suggest ways forward for relational values research. Environ Values. 33(2):139–162. doi: 10.1177/09632719241231422.

- Gould RK, Muraca B, Himes A, Hackenburg D. 2023. Biodiversity and relational values. En reference module in life sciences. Elsevier. 10.1016/B978-0-12-822562-2.00091-8.

- Gould RK, Pai M, Muraca B, Chan KMA. 2019. He ʻike ʻana ia i ka pono (it is a recognizing of the right thing): How one indigenous worldview informs relational values and social values. Sustainability Sci. 14(5):1213–1232. doi: 10.1007/s11625-019-00721-9.

- Graeber D, Wengrow D. 2021. The dawn of everything: a new history of humanity. London, UK: Penguin.

- Guadilla-Sáez S, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Reyes-García V. 2020. Forest commons, traditional community ownership and ecological consequences: insights from Spain. For Policy Econ. 112:102107. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102107.

- Guha R. 2000. The unquiet woods: ecological change and peasant resistance in the Himalaya. Oakland, California, USA: Univ of California Press.

- Gutierrez Garzon AR, Bettinger P, Siry J, Abrams J, Cieszewski C, Boston K, Mei B, Zengin H, Yeşil A. 2020. A comparative analysis of five forest certification programs. Forests. 11(8):863. Article 8. doi: 10.3390/f11080863.

- Hardin G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons: the population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality. Science. 162(3859):1243–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243.

- Hays SP. 2007. Wars in the woods: the rise of ecological forestry in America. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA: University of Pittsburgh Pre.

- Helms JA. 2002. Forest, forestry, forester: What do these terms mean? J For. 100(8):15–19. doi: 10.1093/jof/100.8.15.

- Herrmann TM, Torri M-C. 2009. Changing forest conservation and management paradigms: traditional ecological knowledge systems and sustainable forestry: perspectives from Chile and India. Int J Sust Dev World. 16(6):392–403. doi: 10.1080/13504500903346404.

- Himes A, Muraca B. 2018. Relational values: the key to pluralistic valuation of ecosystem services. Curr Opin Sust. 35:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.09.005.

- Himes A, Muraca B, Anderson C, Athayde S, Beery T, Gonzalez-Jimenez D, Gould R, Hejnowicz AP, Kenter J, Lenzi D, et al. 2024. Why nature matters: a systematic review of intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values. BioScience. 74(1):25–43. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biad109.

- Himes A, Puettmann K, Muraca B. 2020. Trade-offs between ecosystem services along gradients of tree species diversity and values. Ecosyst Serv. 44:101133. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101133.

- Holling CS, Meffe GK. 1996. Command and control and the pathology of natural resource management. Conserv Biol. 10(2):328–337. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020328.x.

- Hosen N, Nakamura H, Hamzah A. 2020. Adaptation to climate change: does traditional ecological knowledge hold the key? Sustainab. 12(2):676. Article 2. doi: 10.3390/su12020676.

- Howitt R, Suchet‐Pearson S. 2006. Rethinking the building blocks: ontological pluralism and the idea of ‘management’. Geogr Ann Ser B. 88(3):323–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0459.2006.00225.x.

- Huntsinger L, McCaffrey S. 1995. A forest for the trees: forest management and the Yurok environment, 1850 to 1994. Am Indian Cult Res J. 19(4):155–192. doi: 10.17953/aicr.19.4.cv0758kh373323h1.

- Jain TB. 2013. Silviculture research: the intersection of science and art across generations. Western Forester. 8–9.

- Jax K, Calestani M, Chan KM, Eser U, Keune H, Muraca B, O’Brien L, Potthast T, Voget-Kleschin L, Wittmer H. 2018. Caring for nature matters: a relational approach for understanding nature’s contributions to human well-being. Curr Opin Sust. 35:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.009.

- Jeanrenaud S. 2001. Communities and forest management in Western Europe: a regional profile of WG-CIFM the working group on community involvement in forest management. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Johann E. 2007. Traditional forest management under the influence of science and industry: the story of the alpine cultural landscapes. For Ecol Manage. 249(1–2):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2007.04.049.

- Kaltenborn BP, Linnell JD, Baggethun EG, Lindhjem H, Thomassen J, Chan KM. 2017. Ecosystem services and cultural values as building blocks for ‘the good life’. A case study in the community of røst, Lofoten Islands, Norway. Ecol Econ. 140:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.003.

- Kim S, Li G, Son Y. 2017. The contribution of traditional ecological knowledge and practices to forest management: the case of Northeast Asia. Forests. 8(12):496. Article 12. doi: 10.3390/f8120496.

- Klain SC, Olmsted P, Chan KMA, Satterfield T, Zia A. 2017. Relational values resonate broadly and differently than intrinsic or instrumental values, or the new ecological paradigm. PLOS ONE. 12(8):e0183962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183962.

- Klinger S, Bayne KM, Yao RT, Payn T. 2022. Credence attributes in the forestry sector and the role of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. Forests. 13(3):432. Article 3. doi: 10.3390/f13030432.

- Krumm F, Bauhus J, Bo Larsen J, Knoke T, Poetzelsberger E, Schuck A, Rigling A. 2023. «Closer-to-nature forest management»: was ist neu an diesem konzept? Schweizerische Zeitschrift fur Forstwesen. 174(3):158–161. doi: 10.3188/szf.2023.0158.

- Latulippe N, Klenk N. 2020. Making room and moving over: knowledge co-production, indigenous knowledge sovereignty and the politics of global environmental change decision-making. Curr Opin Sust. 42:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.10.010.

- Lowood HE. 1990. The calculating forester: quantification, cameral science, and the emergence of scientific forestry management in Germany. The Quantifying Spirit in the 18th Century. 11:315–342.

- Ludwig D. 2001. The era of management Is over. Ecosystems. 4(8):758–764. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0044-x.

- Martinez D. 2018. Redefining sustainability through kincentric ecology: reclaiming Indigenous lands, knowledge, and ethics. In: Nelson Mk, Shilling D, editors. Traditional ecological knowledge. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; p. 139–174.