?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Large-scale land acquisitions in Africa are increasing, reported often as the transfers of land for food and biofuel crop production. Only reporting agricultural acquisitions underplays potential impacts of other forms of acquisitions like tourism and conservation, which are new engines for economic growth in Southern Africa. While this shift has complex social-ecological implications, there is limited evidence of the multiple ways that land acquisitions unfold in wetland ecosystems, and implications for people and nature. This study aims to investigate local perceptions of implications of land and water acquisitions on local livelihoods in the Okavango Delta, Botswana, using in-depth interviews with 116 local respondents in Etsha 6, Khwai and Tubu villages. Findings revealed that the primary drivers of land acquisitions in the Okavango Delta were tourism and subsistence agriculture, and a new and unique land exchange (we termed land borrowing) was prevalent in Tubu, involving the borrowing of farmland in flood recessions between locals. Concessions, borrowings, and rentals were key perceived land acquisition types. Both positive and negative impacts of land acquisitions on livelihoods surfaced. The diversity of cultural grouping influenced locals’ intricate connection with riparian waters and affected how land was exchanged and governed. The disparities in benefits from land resources have negative implications for equitable resource distribution and natural resource governance, in policy and practice. This research highlights the importance of an expanded view of acquisitions and associated impacts with closer attention to power dynamics which can facilitate more nuanced implementation of targets of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity framework.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, Africa had significant increase in large-scale land acquisitions, exceeding 20 million hectares (Kleemann and Thiele Citation2015; Johansson et al. Citation2016). Some governments of the countries targeted for land acquisitions have welcomed them as foreign direct investments (FDI) that contribute to development opportunities (Woodhouse Citation2012; Kleemann and Thiele Citation2015). However, these investments are also criticized for enabling acquisitions that benefit a few individuals (Baxter and Schaefter Citation2013) while negatively impacting local communities and ecological systems (Borras and Franco Citation2010; Hall Citation2011; Messerli et al. Citation2013).

Land acquisitions for agriculture in developing countries can exacerbate rural poverty and relegate local farmers into subsistence farming (De Schutter Citation2011). The transformation of rural landscapes into protected areas and other land uses by states, can also lead to the appropriation of natural resources, which raises concerns about local livelihoods and access to resources (De Schutter Citation2011; Chung Citation2018). Additionally, this results in increased pressures, competition, and conflicts over natural resources (Messerli et al. Citation2013; Johansson et al. Citation2016). The ability of local communities to adapt to these changes is influenced by their existing vulnerabilities and social-ecological relationships (Shinn Citation2017). Nevertheless, mutually beneficial land acquisition processes between investors and host countries are encouraged (Baxter and Schaefter Citation2013) where perceived to contribute to employment, knowledge and skills transfer, increased access to capital, technology, and global markets (Baxter and Schaefter Citation2013).

The traditional focus of global land grab debates has commonly been about acquisitions for food supplies (agribusinesses, food crops, pastoral land) and biofuel crops (Daniel et al. Citation2013; van Noorloos et al. Citation2014; Nyantakyi- Frimpong and Kerr Citation2017; Salverda Citation2019). The focus on agriculture leaves newer commercial pressures, such as acquisitions for climate change mitigation and adaptation, mining concessions, tourism, and conservation, underexplored in the literature (Hall Citation2011; Zoomers and Kaag Citation2014; van Noorloos et al. Citation2014; Vogel and Raeymaekers Citation2016). This study argues that the narrative of agriculture acquisitions underplays the potential impacts of other forms of acquisitions such as those for mineral extractions (Vogel and Raeymaekers Citation2016; Lukongo Citation2018) and conservation, especially in biodiversity-rich wetlands which are seldom reported, as is the case of the Okavango Delta. While some literature focuses on quantifying mostly large sizes and scales of land grabs, the unquantifiable small-scale acquisitions remain largely undocumented (Mbiba Citation2017), yet they have both negative and positive social-ecological implications for local livelihoods and the environment. Exploring the dynamics and impacts of other forms of land acquisitions are especially important as countries seek to implement measures to achieve the targets of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, e.g. Target 3 to conserve 30% of land, water and sea by 2030) while ensuring participation in decision-making and access to justice and information related to biodiversity for all (Target 22) (Schröter et al. Citation2023). Conservation and commodification of nature which are sometimes termed ‘green grabs’, have significant implications for local communities including changes in the control over access, use, and management of land-related resources (Fairhead et al. Citation2012; Zoomers and Kaag Citation2014), wherein, acquisitions aimed at enabling and expanding wildlife habitat block off local communities from accessing and benefiting from ecosystem services in public lands (Lunstrum Citation2016).

This study employs a social-ecological systems approach to investigate land acquisitions within the Okavango Delta. While tourism and wildlife conservation have spurred economic growth in Botswana (Mbaiwa et al. Citation2008), elsewhere it has negative consequences like widespread dispossession and displacement of local communities through privatization of common resources like land, forests, and water (Devine and Ojeda Citation2017). In Botswana’s Okavango Delta, investments in tourism activities are predominantly controlled by foreign entities, international financial institutions, and donors, at the expense of the legitimate land and resource rights of local communities (Mbaiwa Citation2005). Various land exchanges evolve from these tourism investments, which poses a threat to land ownership, land reform and rights for local communities. The coexistence of indigenous activities and tourism-based activities leads to persistent land use conflicts in the delta (Darkoh and Mbaiwa Citation2009; Mogomotsi et al. Citation2020). However, there is limited evidence which documents the multiple ways that land and water acquisitions unfold, and the associated impacts for people and nature in especially tourism and conservation spaces associated with wetlands. Hence, this study contributes to land acquisition literature by investigating the perceptions of local communities on land and water acquisitions in the Okavango Delta, Botswana.

The study conceptualizes the Okavango Delta as a complex social-ecological system (SES) that undergoes dynamic changes, and as such, provides a way to integrate and analyze humans as integral parts of the system. SES approach enables the examination of interactions and feedbacks between the social and ecological systems (Schoon and van der Leeuw Citation2015). Viewing land and water as a social-ecological system wherein multiple-actor interests and motivations are at play (Adams et al. Citation2019), we combine SES thinking and a political ecology lens to explore and analyze our findings. Political ecology helps to understand power imbalances between land acquirers and local landholders, which significantly shape the nature and outcomes of land exchanges (Doss et al. Citation2014). Political ecology helps to focus social-ecological contestations over resource uses and understand the power relations underlying these contestations and how actors navigate the outcomes of environmental and resource politics (Pichler and Brad Citation2016). Therefore, an analysis of local community perceptions is necessary to understand how power, in its multiple forms, manifests in land acquisitions, and how local communities perceived social-ecological implications of these acquisitions. The local conditions and power relations that underlie land and water acquisitions are not adequately documented in literature, with limited scholarly documentation of local perceptions of land and water acquisitions in wetlands with multiple land uses and users. Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore local community perceptions on land acquisitions in the Okavango Delta, and their associated social-ecological implications on local livelihoods.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Description of the study area: Okavango Delta in Botswana

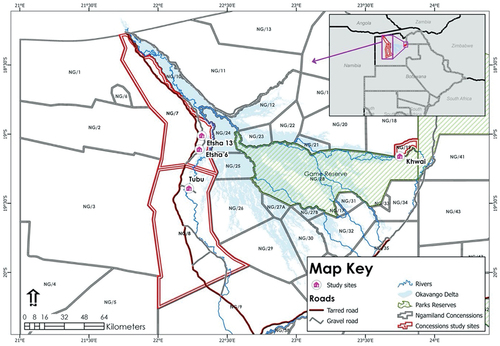

The Okavango Delta is part of the broader Okavango River basin, comprising the Cuito and Cubango catchment area in Angola, and the Kavango–Okavango catchment area in Namibia and Botswana (Mogomotsi et al. Citation2020). It is a UNESCO World Heritage site and the world’s largest inland delta with various flora and fauna (Darkoh and Mbaiwa Citation2014). The main tributaries of the Okavango Delta are Quito and Cubango rivers, which receive rainfalls of 76 and 983 mm/year, respectively (McCarthy et al. Citation2000). Rain falls between December and March, which accumulates in the Okavango river and discharges into the delta wetlands in Botswana (McCarthy et al. Citation2000). The lower delta experiences an increase in flows between May and October, and experiences dry conditions with a decrease in river flows from November to April (Akoko et al. Citation2013). Three (3) study villages were conveniently sampled as study case study sites for in-depth analysis: Selection of these study sites was based on (1) reflective recurrent natural resource conflicts, (2) geographical location within Okavango Delta World Heritage Site, and (3) Proximity to tourism concession areas and protected areas (). Khwai village is in the lower pan handle, whereas Tubu is located in the middle, and Etsha 6 in the upper pan handle of the Okavango Delta (). The Okavango Delta traditionally consists of four ethnic groups: Bayeyi, Bahambukushu, Basubiya and Basarwa – with unique languages and cultural practices which co-evolved with the Okavango Delta ecosystem.

Figure 1. Study area map including Khwai, Tubu and Etsha 6 villages in the Okavango Delta, Botswana.

2.1.1. Land concessions in the Okavango Delta, Botswana

The Okavango Delta has approximately 23 land concession areas known as Ngamiland concessions (NGs) as depicted in . Among these, 11 are managed by local communities through the Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) program, while 12 are managed by private concessionaires. Land concessions create buffer zones called wildlife management areas (WMA) around the delta, separating the delta from neighbouring communal settlements. Tubu is adjacent to NG25 (which is known as the Jao concession and managed by a private safari company) and NG26 (which is known as Abu concession and managed by a private safari company), Etsha borders NG24 and NG25, and Khwai is situated within NG19 which is managed by the government. The Khwai community owns NG18 (known as Khwai concession) through a Community Based Organization (CBO) and it is managed by a private investor. Diverse stakeholders exist within the delta: (a) local communities living next to protected areas and not practicing CBNRM but relying on subsistence agriculture; (b) local communities practicing CBNRM; and (c) private concessionaires. These three stakeholders exist within a broader governance system led by the national government of Botswana.

2.2. Methodology and data collection

Semi-structured interviews were used to collect primary data about the perceptions of households on land acquisitions. A case study design methodology approach was used to obtain in-depth appreciation of an issue in its natural real-life context (Crowe et al. Citation2011). A semi-structured questionnaire (closed-ended and open-ended questions) was administered to household heads or adults aged 18 years (regarded as adult legal age in Botswana) and above.

The Botswana Population and Housing Census of 2011 was used to select sample households, and a Taro Yamane (Citation1967) simple statistical formula was used to obtain sample size explained in the formular and :

Table 1. Population size, number of listed households, Sample size, and Response rate in the study villages.

where n = sample size

N = sample

e = margin of error (0.10)

The household list was collected from the Botswana national population and housing census (Central Statistics Office [CSO] Citation2011) to obtain the sampling frame. The household sample size was calculated using the simple Taro Yamane formular above, and subsequently households were selected by a simple random sampling method. The response rate in Tubu was 100%, while Khwai and Etsha were 77% and 41%, respectively (). Some household heads refused to be interviewed, and others were absent during the time of the survey. Our data collection took place between April 26th and May 8th which are harvesting season for subsistence farmers and a busy tourism season in all the study sites. In the end, we conducted our study with 42 households in Tubu, 39 households in Khwai, and 35 households in Etsha 6. Each interview at each household lasted for approximately 45 minutes.

2.3. Data analysis

All 116 interviews were transcribed, ensuring data accuracy and completeness to ensure data integrity. These transcripts were then uploaded on Atlas.ti for coding and analysis, employing both deductive and inductive coding. Coding involved grouping data into different major themes to make inferences about the data (Gibbs Citation2007; Teddlie and Tashakkori Citation2009). Atlas.ti facilitated the identification of key messages, grouping them into major themes deduced from research questions. Atlas.ti further facilitated the generation of texts/quotations from the interviews, which assisted with a reflective analysis of initial themes using an inductive approach (Scoratto et al. Citation2020). Generated themes encompassed types of acquisitions, direction of acquisitions, implications of land acquisitions and involved actors. These codes were inductively developed from the questionnaire and reported as novel themes, coded and categorized into main themes. Results were presented thematically combining qualitative narratives with illustrative themes, graphs, and tables to enhance data interpretation and exploration of relationships.

2.4. Positionality

As researchers, we bring our own subjectivity to the research process, and our personal experiences and biases may influence how the research question in study has been approached, how data was interpreted, and how conclusions were drawn. The first author is a PhD candidate and a Motswana national with fieldwork experience from the Okavango Delta since the past five (5) years, whereas the second and third authors are experienced researchers in social-ecological systems thinking research. Being a local who speaks and hears the local languages in the district, helped a lot with local reception during fieldwork and being welcome in research fatigued communities in the delta. To mitigate the personal biases of the researchers, the study used scientific sampling, and data collection and analysis methods.

3. Results

The first section of the results section reports on households’ socio-economic characteristics for each study village, the second section reports the nature of land acquisitions per study village, and the direction of these acquisitions. Lastly, communities’ perceptions of impacts of land acquisitions are reported.

3.1. The distribution of households by socio-economic characteristics

The study included three major cultural groups: San, Bahambukushu, and Bayeyi. The Bayeyi comprised the largest group (53%), followed by the Bahambukushu (43%) (). These tribes are originally Bantu tribes who traditionally engage in mixed subsistence activities like sorghum agriculture, hunting, fishing, harvesting wild fruits, and pastoralism (Bock Citation1998). In Khwai, the majority 77% were San (Bukhakhwe), who are known as the ‘bushmen of the river’, and traditionally engage in fishing, hunting, and collecting wild and riverine plant foods (Bock Citation1998). In Tubu, the Bayeyi were the dominant cultural group (98%), while in Etsha, both Bayeyi and Bahambukushu coexisted. Most of the respondents were unmarried, with the majority being females (63%), and the rest being males. There is generally low marriage uptake and a decline in marriages in Botswana (Dintwat Citation2010) and considering the high unemployment rate in the study areas, the reasons for this could be that dowry and wedding expenses are unaffordable to many. Formal education was not common among the respondents, and a significant proportion (66%) considered themselves unemployed. In the study area, farming is done for consumptive purposes, and there is generally a very high unemployment rate in Botswana. Of those employed (21%), many (54%) worked in Ipelegeng, which is an informal employment and a national government poverty eradication scheme, while others worked as security officers and cleaners in primary schools and private safaris. Only two respondents were employed by government.

Table 2. Distribution of households by socio-economic characteristics.

3.2. Assessing the nature, and impacts of land acquisitions in the Okavango Delta

3.2.1. The nature and directions of land acquisitions in the Okavango Delta

In Khwai, the dominant perceived types of land acquisitions were tourism land concessions (85%), leases (36%), purchases (21%) and rentals (18%), whereas in Tubu, the dominant perceived type of land acquisitions (52%) was borrowing of land. According to respondents, land borrowing involves the exchange of farmland or residential land between two persons (who are usually related) for a period of time. This form of land exchange is prominent on flood recession land and is used for molapo farming. Molapo farming is a type of traditional farming prevalently conducted on flood recessions. It is driven by water availability and is known for higher food productivity compared with dry land farming. Some respondents explained that in Tubu, land and water are traditionally viewed as shared resources and can be borrowed or gifted without financial transactions within their culture. A respondent said,

At molapo farms we plough maize and beans while at dry land farms we plough watermelons, millet and sweet reeds which take a while to be ready for harvest.

In Etsha, 38% of respondents, 33% in Tubu were unsure about the prevalent types of land acquisitions. Approximately 29% Etsha respondents reported purchase of land, while 6% attributed inheritances as prevalent land exchange types.

3.2.1.1. Local perceptions on the direction of land exchanges in the Okavango Delta

In Khwai, respondents explained that the local community operates campsites through the management of a CBO in NG19, generating revenue from self-driven tourists. Additionally, at NG18, one respondent mentioned, ‘NG18 is our business area where the local community through leases benefits from annual returns, while NG19 is the land concession that houses our village homes’. Some Khwai respondents explained that in NG19, a few local elites also own campsite land through inheritances, government allocations, or government youth development programmes. In Tubu, 50% of respondents believed that land acquisitions primarily take place between locals, similar to the majority (51%) in Etsha. However, 37% of Etsha respondents were unsure about the direction of land exchanges, a sentiment shared by 19% of Tubu respondents ().

3.2.2. Perceptions of impacts of land acquisitions on local livelihoods

Local communities stated various ways in which land acquisitions impacted livelihoods. While 48 respondents from the study (Khwai n = 4, Tubu n = 20, Etsha n = 24) did not perceive positive impacts of land acquisitions, 10 different types of negative impacts were mentioned across the three villages. On the whole, it appears that Khwai residents experienced more positive benefits, followed by Tubu and then Etsha ().

Table 3. Nature and Impacts of Land acquisitions on local livelihoods in the Okavango Delta.

3.2.2.1. Communities’ perceived positive impacts of land aquisitions in the Okavango Delta, Botswana

The most positive implication of land acquisition on local communities across all study sites was job creation and inclusions of local community in land development decisions.

(a) Increases in agricultural productivity

In Tubu and Etsha, the borrowing of land was perceived to increase crop yields due to the ability to farm on both dry and flood recession molapo farmland. Specifically, 12% of Tubu respondents(n = 5) and 6% of Etsha (n = 2) perceived that borrowing of land has improved their livelihoods and food production, while one highlighted that it promotes farming among the youth. In Khwai, where agricultural activity is limited due to high wildlife population, there were no responses related to agricultural produce.

(b) Local job creation

Most respondents from Khwai (n = 27) compared with Etsha (n = 10) and Tubu (n = 4) cited job opportunities as a positive benefit of land acquisitions. The respondents felt that local communities have job opportunities, especially the youth who are usually trained for tourism vacancies. Respondents mentioned that locals are mostly hired in the positions of canoe polers, scullery, housekeeping, cleaners, tour guides and chefs. In Tubu, respondents explained that it is uncommon for locals to be hired in tourism camps, because operations usually hire workers from head offices in Maun (256 km away).

(c) Local business opportunities

Only respondents from Khwai (n = 8) and Etsha (n = 3) reported positive economic opportunities as a result of land acquisitions. In NG19 in Khwai, individual passerby tourists regularly purchase handmade baskets, firewood, and groceries from local tuck-shops. Although respondents also sell thatching grass to safari camps, they said it seldom happens (once in 10 years) due to increased preference towards canvas materials for construction, which lowers their sales. In Etsha, respondents sold handmade baskets to passerby tourists at the river during fishing times. Other locals offered poler/canoeing services to individual tourists at the river or rented out canoe boats to tourism camps for a fee.

(d) Local food hamper and school uniform donations

Some respondents reported that they receive food monthly as donations from private safaris and lodges, while some only received seldomly or had ever received just once especially during COVID-19 lockdowns. Tubu respondents (n = 12) received the most food hampers and school uniform donations from private tourism safaris and lodges, compared with Khwai (n = 7) and Etsha (n = 2) respondents. Tubu respondents mentioned that they also receive school uniform donations from safari camps in the neighboring land concessions.

(e) Transport donations to local communities from tourism camps

Only Khwai and Tubu respondents reported to have received vehicle donations from private safaris and lodges, via a CBO in Kwai and directly to the community in Tubu. In Tubu, the vehicle helps to transport elderly members of the village to hospital visits, while in Khwai where there is no public transport, the vehicle is used to give free lifts to community members travelling to Maun, where they purchase incentives like groceries.

(f) Local scholarship and skills training

Only Khwai respondents noted skills and knowledge transfers through scholarships and short skills training for local youths, as a result of tourism acquisitions. These include short training on tourism-related courses, like animal tracking, tour guiding and chef training. Moreover, university scholarships are offered by safari camps to outstanding local students, while opportunities for continuation of basic education are offered to local students who failed junior secondary and senior secondary-level education.

(g) Monetary donations to local communities from annual returns for trusts

Only Khwai and Tubu residents cited improved livelihood changes from monetary and welfare donations. Khwai respondents reported that as a result of annual returns from the NG18 land concession, the CBO gives the elderly and less privileged community members monthly allowances of BWP600 for livelihood sustenance, while the community is financially assisted during social functions (weddings and funerals). About 28% of households (n = 11) in Khwai reported since the COVID-19 global pandemic, that these donations are not consistent. In Tubu, n = 2 households reported that monetary donations from tourism investors have assisted the community events such as Christmas and Independence Day celebrations.

(h) Local solar panel donations

Only 21% of Khwai respondents (n = 8) cited solar panel donations curtesy of tourism investors who have rental leases in NG18. These solar panels are used for electric power and charging electrical appliances such as mobile phones.

(i) Infrastructural developments

Khwai and Etsha respondents perceived benefits from infrastructural developments as a result of land acquisitions. About 23% (n = 9) Khwai respondents reported school infrastructure where local children attend for free. In Etsha, two respondents reported the refurbishment of the primary school curtesy of donations from the safari camps.

(j) Inclusions of local communities in land acquisition decisions

In total, the majority of respondents (57%) felt included in decisions regarding land and water acquisitions. However, when analyzing by village, Khwai (69%) and Tubu (62%) had higher levels of inclusion compared with Etsha (37%). Khwai respondents stated that they often attended Kgotla (a central formalized area in a traditional village used for assemblies and meetings of the leaders and the community) meetings for consultations about land developments and attended CBO annual general meetings to review applications for tourism concession leases from tourism investors. Conversely, a significant number of Etsha respondents (63%) felt excluded from such decisions. Although they acknowledged that they attend Kgotla meetings, they lamented that their meetings are often for village social issues and not for land development matters. Other respondents cited lack of consultation, arguing that developments take place in the village without knowing the owners of projects. They reported that tourism acquisitions transpire between the government and investors, without community consultations. Tubu (33%) and some Khwai respondents (18%) also believed that kgotla meetings were mere formalities, where government informs communities of decisions, not as a consultative process. A few Khwai respondents (13%) remained indifferent, feeling that their opinions were never considered, even when consulted through kgotla meetings.

3.2.2.2. Communities’ perceived negative impacts of land aquisitions in the Okavango Delta, Botswana

(a) Perceptions of negative impacts

While 45 respondents (Khwai n = 11, Tubu n = 14, Etsha n = 20) reported to not perceive any negative impacts of land acquisitions, there were 10 different types of negative impacts noted across the three villages. Most Etsha respondents (57%) compared with other study villages did not perceive negative impacts of land acquisitions. Khwai residents experienced more negative impacts followed by Tubu and Etsha ().

(b) Restrictions of access to land and water resources

Most respondents reported restrictions of access to land and its related resources as a result of land acquisitions. In Khwai, (n = 7) (18%) reported that they had a limited access to land and water resources, while in Tubu (n = 6) (14%) stated similar experiences. In Etsha, (n = 3) (9%) reported that they had limited access to land and water resources.

(c) Human wildlife conflict

All respondents showed concerns about influxes of wildlife (lions, elephants, hyenas) in the communities as a result of tourism acquisitions, resulting in destructions of homes and flood recession molapo farms in Tubu, human deaths in Khwai, and crop raiding and domestic animal fatalities in Etsha.

(d) Ecological impacts

About 18% of Khwai respondents perceived that tourism acquisitions resulted in congestion in the village. They reported increased population and vehicle movement which damaged roads, destroyed wildlife habitats (especially bird nests), and altered wildlife movement corridors. The respondents reported an increase in self-drive tourists who create many off roads, which they felt damaged the main roads. This uncontrolled vehicle movement results in noise pollution which was reported to destroy wildlife movement.

(e) Delayed local developments activities

As a result of land acquisitions, Khwai respondents (n = 2) reported delays in village development by the government, due to an expectation for investors to develop the village. One respondent exclaimed,

We have late developments because government expects investors to undertake community developments, which they don’t. We only have a mobile clinic, yet we are sitting on a pool of natural resources which are more profitable to investors than local people.

(g) Local development trust issues

All study sites exhibited lack of trust for CBOs in managing finances and vehicle donations from investors. This mistrust led to conflicts between locals and CBOs. In Khwai 46% (n = 18) of respondents cited that mistrust emanated from the unequal distribution of benefits from investors by CBOs, which result in conflicts between locals who benefit and those who do not benefit. Misuse of funds and inadequate consultation by village leaders were reported to potentially lead to the cessation of investors donations. In Etsha, 40% of respondents (n = 14) expressed some frustrations due to the absence of a functional CBO, which they believed resulted in missed economic opportunities like zero donations, and not being able to sell harvested goods and crafts to safari camps, like other neighboring villages. In Tubu, 38% (n = 16) reported that their CBO was still in the establishment process and lacked land, finances, and resources to manage under a community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) program, leading to missed opportunities like jobs and food donations from tourism operators and investors.

(h) Change of national political administration

Only Khwai 10% (n = 4) respondents viewed that the change in national political administration affects land use agreements between investors and local community. They stated that the agreements on land uses and joint venture agreements between investors and the local community have in the past negatively altered the ways in which community benefits from land acquisitions.

(i) Poaching

Three of the Khwai respondents reported poaching as a result of land acquisitions, stating that a lack of monitoring in the land concessions that are privately leased has in some ways propelled poaching of plant species and small wildlife such as birds by tourists.

(j) Nepotism

Tubu had a high number of nepotism cases (26%), compared with Etsha (9%) and Khwai (5%) villages. A common answer across study villages was that tourism operators hire employees from the head offices in Maun at the expense of locals from the Okavango Delta. Tubu respondents stated that employment opportunities from tourism operations are given to a few educated Tubu locals, or Batswana locals, which propels conflicts and influences tribalism.

(k) Power imbalances between locals and investors

Few Khwai (13%) and Etsha (11%) respondents felt that power imbalances between locals and investors are brought by land acquisitions. Khwai respondents opined that the competition for acquiring commercial land is high, therefore locals are forced to bid for commercial land against investors with financial strength. Some locals felt that tribal land is in the hands of tourism operators, while individual local community members have no land. They added that this leads to communities blaming the tourism industry operators and relying on benefits from the industry for everything, which they felt was not ideal. Etsha respondents opined that tourism operators use community land for businesses, while locals gained nothing in return.

(l) Dispossessions of land resources from local communities

Approximately 33% of respondents believed that dispossessions in local communities resulted from land acquisitions, with Tubu (50%), Khwai (38%) and Etsha (6%) having varying responses. In Tubu, locals expressed that their ancestral lands (matlotla) were claimed from farming and residential land uses by government and reallocated to private investors for tourism land uses. Tubu respondents reported that this resulted in limited access to areas which locals used to collect land-related resources (reeds, thatching grass, fish, wild fruits, and firewood) for free and unrestricted. Some Tubu respondents (n = 13) in fact noted that land had not been allocated to locals for an extended period, relegating locals to landlessness. One respondent exclaimed,

We are no longer allocated land by land board so we feel we are not given right to land; we are told that our village is on floodplains therefore we cannot be allocated land.

Khwai respondents attributed land shortages to tourism business operations occupying community land, and to government restrictions on access to protected areas which previously provided land-related resources without limitations. They also lamented about reduced access to wildlife for hunting due to conservation policies and the establishment of a game reserve and tourism camps, dispossessing them of harvest and hunting areas.

(m) Land enclosures for locals

Approximately 21% of Khwai respondents, (n = 8), 17% of Tubu respondents (n = 7), and 6% of Etsha respondents (n = 2) reported experiencing enclosures. In Khwai, respondents reported that these enclosures were linked to the establishment of protected areas bordering the village, which they felt limited their access to land and water resources. One respondent exclaimed,

We are enclosed outside the Moremi game reserve and Chobe national parks. However, these are areas we used to access freely to access resources; we cannot use the water in these areas, but we need to harvest reeds, thatching grass and tswii (water lilly) from there.

Although there were no physical fences, access often required permits and licenses, which they felt are difficult to obtain. While permits were obtained for hunting and resource harvesting, they felt that the 20-day window period was short. A few respondents said that the seasonal restrictions were difficult to wait for, leading to illegal out-of-season harvesting by locals.

(n) Resettlement of local communities

More Khwai respondents (77%) compared with Tubu (26%) and Etsha (23%) have been resettled. Khwai respondents explained that they were first resettled primarily for the establishment of Moremi game reserve in the 1960s, before settling where Khwai village is currently located. Respondents cited forceful removals, illegal home and belongings burning, and livestock killings without community agreements. A respondent explained,

We were moved from Khwega, Karabara to Xuku/hippo pool and the wildlife came and brought with it the protected areas, then we were moved to Segagama and they brought conservation policies and procedures again, and we moved to Saguni, and finally we were moved to Khwai and were told that the border between us and the government is the river between us and the game reserve. Now we hear rumors that we must move again, but we will not, if anything we would love to go back to the Moremi game reserve where we came from.

Tubu respondents attributed their resettlement to the tsetse fly disease, which killed animals and people in their previous settlements: Xukune, Jao, Handa and Tanosura, before settling in Tubu. Other respondents mentioned the 2011 floods as a reason for their resettlement, which led to a loss of homes and livestock. A few stated that they relocated themselves from Mombo to Tubu for proximity to developments and resources. In Etsha, most respondents mentioned that they were resettled from Jao due to livestock diseases, including foot and mouth and lung diseases.

(o) Local knowledge and awareness issues

About nine Etsha 6 respondents (26%) reported that they were not aware of the livelihood impacts of land acquisitions. They felt that land acquisitions in their area are private, and they take place within privately owned land. These respondents explained that they are not aware if they must benefit anything from land acquisitions as these are happening on private lands, noting that the benefits of land exchanges are enjoyed by entities that are exchanging their own land.

4. Discussion

The study investigated the nature and direction of land acquisitions, and perceived implications on local livelihoods in Khwai, Tubu, and Etsha village in the Okavango Delta Botswana. Although study sites have similar recurrent natural resources, they experience unique challenges and opportunities as a result of land and water acquisitions. Furthermore, the socio-cultural practices of various ethnic groups within these villages appears to influence their use and governance of land and water resources.

4.1. The nature and direction of acquisitions in the Okavango Delta

The primary drivers of land and water acquisitions in the Okavango Delta were tourism and subsistence agriculture. Previous studies have highlighted that various types of land acquisitions can coexist in a region, such as in Chile where conservation acquisitions have occurred alongside other acquisitions for carbon resources, forestry, and hydroelectricity (Holmes Citation2014). While tourism is the engine of Botswana’s economy, subsistence agriculture is a source of livelihood for locals, which are conflicting land use interests by different users, in the same social-ecological system. The coexistence of various types of land acquisitions in a region can make management and governance decisions challenging in terms of which and whose values to elevate and promote, which could bring about marginality to powerless land users.

Political ecology argues that the struggles over natural resources and environment, and increased marginality and vulnerability can be predicated on unequal social and political power relations (Adams et al. Citation2019). This is further compounded by the lack of awareness of the ongoing land and water exachanges by local communities living within and adjacent to those lands. For example, in the case of Etsha, although land purchases among locals were perceived as a prominent type of land acquisition by some (after the unknown category), the majority of respondents were unaware of such land transactions. This lack of awareness suggests a potential deficit in consultation and poor communication between local communities and decision-making structures within the village. When local communities perceive a lack of control over benefits from tourism and a lack of transparency, it often results in institutional power imbalances over land resources and dispossessions (Benjaminsen and Bryceson Citation2012).

4.2. Acquisitions produce positive and negative impacts

Findings revealed a complex picture of social-ecological impacts of land acquisitions in the Okavango Delta. Overall, more negative than positive social-ecological impacts of land acquisitions were identified. These findings echo previous research by Oya (Citation2013) and Dell’angelo et al. (Citation2017) that implications of land acquisitions are usually negative and have detrimental consequences which threaten their sustainability. The negative social-ecological implications translated into destructions of flora and fauna, limited access to resources, loss of trust, land dispossessions, ethnic conflicts over mineral resources, and the privatization of rights to nature, which have also been reported elsewhere in the literature (Corson and MacDonald Citation2012; Lukongo Citation2018; Wieckardt et al. Citation2022).

Dispossessions, displacements, and resettlements of rural communities, as experienced in Tubu and Khwai, were also reported elsewhere in Botswana (Molebatsi Citation2019). The re-allocation of ancestral lands (matlotla) and previous hunting and grazing lands to private tourism operations in this study has created conflicts among local communities and businesses, potentially exacerbated by the perception that communal lands are often underused and abundant which reduces social appreciation and benefits of land (Bunkus and Theesfeld Citation2018). Development discourses that justify such ‘green grabs’ can disrupt existing livelihoods in enclosures and dispossessions (Fairhead et al. Citation2012; Devine Citation2018; Wieckardt et al. Citation2022). The re-allocation of communal lands to new owners limits local access to ancestral community land which have other functions than food production (Bunkus and Theesfeld Citation2018) and wildlife conservation. It further perpetuates dominance of multinational companies and investors, business elites and a monopolized tourism sector by a few powerful actors in the Okavango Delta (Mbaiwa and Hambira Citation2020) excluding marginal social actors.

In the study site, multiple forms of power interacted in complex ways. The findings exhibit multiple conceptualizations of power as being material and discursive (Fletcher Citation2018). Power is manifested by local communities feeling dominated by powerful actors, and being excluded from material access to land resources for their previously known livelihood activities (Fletcher Citation2018), shaping how local communites understood and perceived their own access to land (reeds, thatching grass, wild fruits) and water resources (water lilly, fish) and performed. In terms of discursive power, it seems that perceptions for land acquisitions are framed differently, while communities demanded cultural and livelihood preservation, they felt that government and corporations framed acquisitions as necessary for conservation efforts and economic development. Through discursive power, certain narratives may be privileged over others, influencing public opinion and policy decisions (Fletcher Citation2018).

Across the globe, similar implications like increased competition for land, eviction of local communities, privatization of natural resources, and the violation of human rights, have been found to compromise the ability for natural resource management to be just and equitable (Borras et al. Citation2011; De Schutter Citation2011; Messerli et al. Citation2013; Edelman et al. Citation2015). A fair allocation of benefits is a key goal of distributive justice, which ensures that stakeholders’ social differences are taken into account to experience the same allocation of environmental resource benefits and burdens (Wijsman and Berbés-Blázquez Citation2022). Where benefits accrue, their distribution is found to be inequitable across study sites, with Khwai receiving more direct positive benefits of land and water acquisitions compared with Tubu and Etsha. These highlight a horizontal power asymmetry within local communities, highlighting the need for more equitable distribution of economic benefits to all local communities whose livelihoods are based on a similar shared resource and impacted by acquisitions from similar industries. The view that land acquisitions yield positive impacts on local communities and provide economic advancements in developing countries are supported by previous studies done elsewhere (Borras and Franco Citation2010; Baxter and Schaefter Citation2013; Balestri and Maggioni Citation2019).

Enhancing procedural justice (a form of justice that is process oriented and concerned with the inclusivity of practices of decision-making, gauging how participation and engagement of social groups is organised) is important in order to surface tensions of allocation of resources and enhance participatory governance (Wijsman and Berbés-Blázquez Citation2022). Some respondents from Tubu were sceptical against such acquisitions, mobilising ideological power through narratives of local or Indigenous rights and environmental stewardship.

4.3. Acquisitions are more than the size of large-scale exchanges

Land borrowing for flood recession molapo farming emerged as an important type of land acquisition and a form of land exchange in this study. This unique type of acquisition, though not explored in land acquisition literature and land grab debates elsewhere, has historical roots in the Okavango Delta in Botswana (Ngwenya et al. Citation2016). Molapo farming for which these borrowings are made significantly contributes to better yields than the common rain-fed dry land farming (Magole et al. Citation2014) and helps to improve livelihoods for vulnerable communities (Motsumi et al. Citation2012) especially for the Bayeyi tribe, who rely on water-based livelihoods. This locally governed and self-initiated approach to land acquisition reflects a form of social innovation and resilience, a means of land ownership and resource use, responding to halted government land allocations. Despite the potential environmental implications due to its non-regulatory process, this form of land use is seen as a way to enhance agricultural productivity and alleviate poverty, aligning with the concept of social innovation for improved societal outcomes (Castro-Arce and Vanclay Citation2020). It signifies a community-driven initiative to optimize land resources, fostering adaptive and integrated ecosystem management practices within this complex social-ecological system (Biggs et al. Citation2010).

Although kgotla meetings were perceived as a form of inclusion in land management and decision-making in Khwai, other concerns revealed kgotla meetings as ineffective. Power imbalances and the top-down approach by government and traditional authorities, as well as the unfair distribution of benefits from investors, were cited as causing mistrust between local communities and authorities. Lelokwane and van der Merwe (Citation2022) posit that CBNRM initiatives under which wildlife is the managed resource are sometimes unsustainable and unjust due to challenges like the misalignment between CBNRM and legislative goals devoid of community involvement in resource management. Participation and inclusion of local stakeholders in decision-making propels communication between industry and communities, and strengthens trust between local stakeholders (Agarwal Citation2001; Tuulentie et al. Citation2019). Participation of communities in decision-making is vital as a measure of citizenship rights and also as a form of empowerment and voice (Agarwal Citation2001). Participatory exclusion of stakeholders in decision-making procedures has implications on procedural injustice, which emphasizes the fairness and inclusion of local actors or communities on decision-making matters, because inclusive processes facilitate transformation of environmental governance (McCarthy et al. Citation2000).

Whereas at Tubu, respondents felt enclosed by veterinary fences, respondents at Khwai felt enclosed by adjacent protected areas, which they felt disrupted their access to previously easily accessible livelihood resources. Enclosures of livelihood assets and displacements of locals have significant impacts including loss of traditional farming practices, food insecurity, disruption of cultural identity and altered livelihoods (Borras and Franco Citation2010; Ongwang and Vanclay Citation2019; Osman and Abebe Citation2023). The exclusions of communities from customary land and water resources have implications for monetary income and non-monetary livelihoods (West et al. Citation2006; Oldekop et al. Citation2016; Holmes and Cavanagh Citation2016), and can compromise their ability to secure land rights and participate in livelihood enhancement practices such as fishing, and subsistence farming (Chu and Phiri Citation2015; Bunkus and Theesfeld Citation2018).

In Khwai, conservation enclosures as a form of land grabbing did not affect locals through physical enclosures in the form of veterinary fences, like in Tubu, where communities cited the negative implications of enclosures through veterinary fencing. In Khwai, enclosures were seemingly in the form of disruption to access livelihood assets, such as the loss of traditional farming practices, and limited access to communal lands, and competition of land with investors. The privatization of user and access rights to nature is found to create new markets and commodities from nature by competing users (Corson and MacDonald Citation2012; Wieckardt et al. Citation2022).

The fishing and hunting bans (which were bans that eliminated wildlife trophy hunting and fishing in the delta) have resulted in negative attitudes towards wildlife conservation among local communities (Yurco et al. Citation2017; Mogomotsi et al. Citation2020). The trophy hunting ban was effected in 2014 in Botswana, motivated by the 2011 areial survey of wildlife populations which showed declines in 11 large mammal species in the area, which was a decision that caused change in wildlife management like hunting and photographic conecssion (Hann Citation2015). On the other hand, the fishing ban was imposed in 2015 as a response to the influx of illegal fishermen and overexploitation of fish stocks (Merron Citation2018).

Our Findings revealed that the era post lifting of the fishing and hunting bans is also not yet well received by locals in the study areas. Respondents articulated that the lifting of these bans has further led to shortened and limited hunting, haversting thatching grass and fishing seasons, and the complex permit application processes which were previously unknown to local communities. As a result, some respondents resisted the permit applications and resorted towards illegal harvesting and hunting of resources outside legal seasons. This depicts a competing interest of stakeholders for shared resources supporting the views that land acquisitions can marginalize traditional resource users, which may accelerate the depletion of natural resources (Dell’angelo et al. Citation2017; Chung Citation2018), and have profound implications for conservation as a result of altered relationships of local communities with the environment (West et al. Citation2006).

4.4. Culture and context matter for how impacts of acquisitions manifest in place

The identification of unique social-ecological relationships and cultural significance within different tribes in the Okavango Delta sheds light on the complex dynamics of land and water acquisitions and their impact on local communities. In Khwai, the Babukhakhwe tribe identified as Basarwa ba noka or ‘bushmen of the river’, and in Tubu, the Bayeyi tribe referred to themselves as batho ba dikhuti or ‘riparian river islands people’. This cultural identity rooted in the land reflects the profound connection between people and their environment, emphasizing the intricate interplay between social heritage, identity and culture as noted by Clarke and Johnston (Citation2003) and Kana’iaupuni and Malone (Citation2006).

In these two study areas, local communities have historically relied on the resources provided by riparian rivers and communal land for their livelihood sustenance. These resources include indigenous food, wild and aquatic plants, fish, thatching grass, reeds, and flood recession molapo farming. This traditional way of life has formed the basis of their unique social-ecological relationship with the environment. However, land acquisitions for tourism purposes in these areas has significantly changed traditional livelihoods and land use patterns, resulting in altered landscapes and resource access for local communities. This transformation has disrupted the longstanding social-ecological relationships that were deeply ingrained in the use of communal land and riparian resources. Previous studies show that land concessions can result in landscape alterations and ecological transformations (Davis et al. Citation2015) with implications in limited access to land resources through enclosures of commons for locals adjacent to concessions (Biard Citation2011; Chu and Phiri Citation2015).

Contrastingly, at Etsha, the dominant tribe interviewed was the Bahambukushu, who are known for dry land farming practices that do not rely on flood recessions and seasonal flows of the delta. We perceive this cultural difference to play a crucial role in shaping perception of tourism acquisitions in the region. Many respondents in Etsha viewed tourism acquisitions as private exchanges between individuals rather than as acquisitions with community-wide benefits. This perception was influenced by the fact that the Bahambukushu community’s traditional livelihoods were seemingly less connected to the Okavango Delta’s resources. This disconnection could potentially be the reason why the majority of Etsha respondents were not well-informed about the specific land concessions in their area, the types of land acquisitions taking place, the actors involved, the presence or absence of CBNRM programs, and whether the community as a whole was benefiting from tourism acquisitions or not. These findings highlight a concerning disparity in knowledge and benefit distribution regarding land and water governance within the local communities of the Okavango Delta.

Despite the research advocating for local community participation in tourism development as essential for the sustainability of the tourism industry (Thetsane Citation2019), our findings indicated a significant gap in awareness and understanding among certain tribes, particularly those like the Bahambukushu in Etsha 6, whose traditional livelihood practices were seemingly less intertwined with the Okavango Delta’s water related resources. Using political ecology to interrogate power asymmetries and contestations over natural resources as both materialistic and symbolic (Mollett Citation2016; Adams et al. Citation2019), these findings reveal Etsha community as potentially marginalized and vulnerable to social-ecological changes in the Okavango Delta. Cultural differences perpetuated their lack of knowledge, making them vulnerable to imbalances in the ownership, negotiations, and governance of land and water resources. Conceptualizing that power can operate horizontally (Fletcher Citation2018), the above reveals power asymmetries within local communities, making Etsha and Tubu communities being burdened from implications of land acquisitions, while Khwai respondents appeared to be more benefiting from acquisitions.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

This research recognizes the Okavango Delta as a complex social-ecological system, with diverse tribal groupings whose relationships with land and water resources vary. We found out that in the Okavango Delta, culture plays an important role in the ways land and water resources are known, used, exchanged or acquired, managed and governed by local communities, resulting in their different ways of adapting to conservation and development agendas. The research found out that the primary drivers of land acquisitions in the Okavango Delta are tourism and subsistence agriculture, wherein CBNRM and non-CBNRM communities experienced different benefits and burdens from land and water resources. These divergent perceptions of benefits contributes to the global debates that focusing land grabs on size and quantity underrepresents environmental alterations, and livelihood implications of underrepresented land acquisitions. The research also found out unique land exchanges which happens on flood recession molapo farmland, which we termed ‘land borrowing’. Such findings underscore the need for future land acquisition studies to focus on local empirical data which will ensure recognition of the unique social-ecological relationships and cultural identities of different tribes. This is essential for achieving sustainable and equitable land and water governance, especially in wetlands across the world where land uses and land users are varied like in the Okavango Delta.

The research underpins that recognizing land and water as related and interconnected resources is essential, as they were both dominant factors driving land transactions and transformations in the Okavango Delta. The study unpacked various forms of exclusions of local communities from decision-making and from land access. This underscores the need for more inclusive and culturally sensitive approaches when conducting land acquisitions research, and when establishing resource management agendas of transboundary wetlands, especially the Okavango Delta. Efforts should be made to bridge the knowledge gaps about land developments, policy and reform, to ensure that all local communities are well informed and actively involved in decision-making processes that affect land-related resource governance in this region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams EA, Kuusaana ED, Ahmed A, Campion BB. 2019. Land dispossessions and water appropriations: political ecology of land and water grabs in Ghana. Land Use Policy. 87:104068. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104068.

- Agarwal B. 2001. Participatory exclusions, community forestry, and gender: an analysis for South Asia and a conceptual framework. World Devel. 29(10):1624–16. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00066-3.

- Akoko E, Atekwana EA, Cruse AM, Molwalefhe L, Masamba WL. 2013. River-wetland interaction and carbon cycling in a semi-arid riverine system: the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Biogeochemistry. 114(1–3):359–380. doi: 10.1007/s10533-012-9817-x.

- Balestri S, Maggioni MA. 2019. This land is my land! Large-scale land acquisitions and conflict events in Sub-Saharan Africa. Def Peace Econ. 32(4):427–450. doi: 10.1080/10242694.2019.1647727.

- Baxter J, Schaefter E. 2013. Who is benefitting? The social and economic impact of three large-scale land investments in Sierra Leone: a cost-benefit analysis. Report for the action for large-scale land acquisition transparency.

- Benjaminsen TA, Bryceson I. 2012. Conservation, green/blue grabbing and accumulation by dispossession in Tanzania. J Peasant Stud. 39(2):335–355. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.667405.

- Biard IG. 2011. Turning land into capital, turning people into labour: primitive accumulation and the arrival of large-scale economic land concessions in the Lao people’s democratic republic. New Proposals: J Marxism Interdiscip Inq. 5(1):10–26.

- Biggs R, Westley FR, Carpenter SR. 2010. Navigating the back loop: fostering social innovation and transformation in ecosystem management. Ecol Soc. 15(2). doi: 10.5751/ES-03411-150209.

- Bock J. 1998 July 02. About the Okavango Delta peoples. Okavango Delta Peoples of Botswana; [accessed Aug 2022]. http://anthro.fullerton.edu/okavango/index.html.

- Borras S, Franco J. 2010. Towards a broader view of the politics of global land grab: rethinking land issues, reframing resistance. Initiatives Crit Agrarian Stud Work Pap Ser. 1:1–39.

- Borras SM, Hall R, Scoones I, White I, Wolford W. 2011. Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: an editorial introduction. J Peasant Studdies. 38(2):209–216. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2011.559005.

- Bunkus R, Theesfeld I. 2018. Land grabbing in Europe? Socio-cultural externalities of large-scale land acquisitions in East Germany. Land. 7(3):98. doi: 10.3390/land7030098.

- Castro-Arce K, Vanclay F. 2020. Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: An analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. J Rural Stud. 74:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.11.010.

- Central Statistics Office. 2011. National population and housing census. Gaborone, Botswana: Ministry of Finance and Development Planning.

- Chu J, Phiri D. 2015. Large-scale lanf acquisitions in Zambia: Evidence to inform policy.

- Chung YB. 2018. The grass beneath: conservation, agro-industrialization, and land–water enclosures in postcolonial Tanzania. Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 109(1):1–17. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1484685.

- Clarke A, Johnston C. 2003. Time, memory, place and land: social meaning and heritage conservation in Australia.

- Corson C, MacDonald KI. 2012. Enclosing the global commons: the convention on biological diversity and green grabbing. J Peasant Stud. 39(2):263–283. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.664138.

- Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. 2011. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 11(100):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100.

- Daniel S. In White B, Saturnino BJr, Hall R Scoones I, & Wolford W. 2013. Situating private equity capital in the land grab debate. In: The new enclosures: critical perspectives on corporate land deals. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; p. 85–112.

- Darkoh MB, Mbaiwa J. 2014. Okavango Delta- a Kalahari oasis under environmental threats. Biodivers Endanger Species. 2(4):1–6.

- Darkoh MB, Mbaiwa JE. 2009. Land‐use and resource conflicts in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Afr J Ecol. 47:161–165.

- Davis KF, Yu K, Ruli MC, Pichdara L, D’Odorico P. 2015. Accelerated deforestation driven by large-scale land acquisitions in Cambodia. Nat Geosci. 8(10):772–775. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2540.

- Dell’angelo J, D’Odorico P, Rulli MC, Marchand P. 2017. The tragedy of the grabbed commons: coercion and dispossession in the global land rush. World Devel. 92:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.005.

- De Schutter O. 2011. How not to think of land-grabbing: three critiques of large scale investments in farmland. J Peasant Stud. 38(2):249–279. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2011.559008.

- Devine JA. 2018. Community forest concessionaires: resisting green grabs and producing political subjects in Guatemala. The J Peasant Stud. 45(3):565–584.

- Devine J, Ojeda D. 2017. Violence and dispossession in tourism development: a critical geographical approach. J Sustain Tour. 25(5):605–617. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1293401.

- Dintwat KF. 2010. Changing family structure in Botswana. J Comp Fam Stud. 41(3):281–297. doi: 10.3138/jcfs.41.3.281.

- Doss C, Meinzen-Dick R, Bomuhangi A. 2014. Who owns the land? Perspectives from rural Ugandans and implications for large-scale land acquisitions. Ferminist Econ. 20(1):76–100. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2013.855320.

- Edelman M, Oya C, Borras SM. 2015. Global land grabs: history, theory and method. London: Routledge; Taylor & Francis.

- Fairhead J, Leach M, Scoones I. 2012. Green grabbing: a new appropriation of nature? J Peasant Stud. 39(2):237–26. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.671770.

- Fletcher AJ. 2018. More than women and men: a framework for gender and intersectionality research on environmental crisis and conflict. Water security Across the Gender Divide. 35–58.

- Gibbs GR. 2007. Thematic coding and categorizing, analyzing qualitative data. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Hall R. 2011. Land grabbing in Southern Africa: the many faces of the investor rush. Rev Afr Polit Econ. 38(128):193–214. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2011.582753.

- Hann EC. 2015. From Calibers to Cameras: Botswana’s ban on trophy hunting and consequences for the socioecological landscape of Ngamiland district.

- Holmes G. 2014. What is a land grab? Exploring green grabs, conservation, and private protected areas in southern Chile. J Peasant Stud. 41(4):547–567. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2014.919266.

- Holmes G, Cavanagh CJ. 2016. A review of the social impacts of neoliberal conservation: formations, inequalities, contestations. Geoforum. 75:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.07.014.

- Johansson LE, Fader M, Seaquist JW, Nicholas KA. 2016. Green and blue water demand from large-scale land acquisitions in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 113(41):11471–11476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524741113.

- Kana’iaupuni SM, Malone N. 2006. This land is my land: the role of place in native Hawaiian identity. Hūlili: Multidiscip Res Hawaii well-being. 3(1):281–307.

- Kleemann L, Thiele R. 2015. Rural welfare implications of large-scale land acquisitions in Africa: a theoretical framework. Econ Modell. 51:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2015.08.016.

- Lelokwane M, van der Merwe P. 2022. A revised CBT strategy for Botswana: reflections from experiences of the ban on trophy hunting. Congent Soc Sci. 8(1):2081109. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2022.2081109.

- Lukongo OEB. 2018. Trans-border trade, minerals, and civil war impacts on land use and land cover change in GOMA, Eastern Congo: an integrated geospatial technologies and political economy approach. Int J Adv Robot Autom. 3(1):1–12. doi: 10.15226/2473-3032/3/1/00129.

- Lunstrum E. 2016. Green grabs, land grabs and the spatiality of displacement: eviction from Mozambique’s Limpopo national park. Area. 48(2):142–152. doi: 10.1111/area.12121.

- Magole L, Chimbari M, Cassidy L, Molefe C. 2014. Influence of flooding variation on Molapo farming field size in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. International Journal of Agricultural Research and Review.

- Mbaiwa JE. 2005. The socio-cultural impacts of tourism development in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. J Tour Cult Change. 2(3):163–185. doi: 10.1080/14766820508668662.

- Mbaiwa JE, Hambira WL. 2020. Enclaves and shadow state tourism in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. South Afr Geogr J. 102(1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/03736245.2019.1601592.

- Mbaiwa JE, Ngwenya BN, Kgathi DL. 2008. Contending with unequal and privileged access to natural resources and land in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Singapore J Trop Geogr. 29(2):155–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9493.2008.00332.x.

- Mbiba B. 2017. Idioms of accumulation: corporate accumulation by dispossession in urban Zimbabwe. Int J Urban Reg Res. 41(2):213–234. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12468.

- McCarthy TS, Cooper GR, Tyson PD, Ellery WN. 2000. Seasonal flooding in the Okavango Delta, Botswana-recent history and future prospects. South Afr J Sci. 96(1):25–33.

- Merron GS. 2018. Lake Ngami. Botsw Notes Records. 50:269–277.

- Messerli P, Heinimann A, Giger M, Breu T, Schönweger O. 2013. From ‘land grabbing’to sustainable investments in land: potential contributions by land change science. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 5(5):528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.03.004.

- Mogomotsi PK, Mogomotsi GE, Dipogiso K, Phonchi-Tshekiso ND, Stone LS, Badimo D. 2020. An analysis of communities’ attitudes toward wildlife and implications for wildlife sustainability. Trop Conserv Sci. 13:194008292091560. doi: 10.1177/1940082920915603.

- Molebatsi C. 2019. Modern era disposession. Town Reg Plann. 75(1):44–53. doi: 10.18820/2415-0495/trp75i1.6.

- Mollett S. 2016. The power to plunder: rethinking land grabbing in Latin America. Antipode. 48(2):412–432. doi: 10.1111/anti.12190.

- Motsumi S, Magole L, Kgathi DL. 2012. Indeginous knowledge and land use policy: implications for livelihoods of flood recession farming communities in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Phys Chem Earth. 50(52):185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pce.2012.09.013.

- Ngwenya BN, Thakadu OT, Magole L, Chimbari MJ. 2016. Memories of environmental change and local adaptations among molapo farming communities in the Okavango Delta, Botswana—A gender perspective. Acta Tropica. 175:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.11.029.

- Nyantakyi- Frimpong H, Kerr RB. 2017. Land grabbing, social differentiation, intensified migration and food security in northern Ghana. J Peasant Stud. 44(2):421–444. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1228629.

- Oldekop JA, Holmes G, Harris WE, Evans KL. 2016. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv Biol. 30(1):133–141. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12568.

- Ongwang T, Vanclay F. 2019. Social impacts of land acquisition for oil and gas development in Uganda. Land. 8(7):109. doi: 10.3390/land8070109.

- Osman AA, Abebe GK. 2023. Rural displacement and its implications on livelihoods and food insecurity: the case of inter-riverine communities in Somalia. Agriculture. 13(7):1444. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13071444.

- Oya C. 2013. The land rush and classic agrarian questions of capital and labour: a systematic scoping review of the socioeconomic impact of land grabs in Africa. Third World Quaterly. 34(9):1532–1557. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2013.843855.

- Pichler M, Brad A. 2016. Political ecology and socio-ecological conflicts in Southeast Asia. ASEAS-Austrian J South-East Asian Stud. 9(1):1–10.

- Salverda T. 2019. Facing criticism: an analysis of (land-based) corporate responses to the large- scale land acquisition countermovement. J Peasant Stud. 46(5):1003–1020. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2018.1439930.

- Schoon M, van der Leeuw S. 2015. Dossier: « À propos des relations natures/sociétés » − the shift toward social-ecological systems perspectives: insights into the human-nature relationship. Natures Sci Sociétés. 23(2):166–174. doi: 10.1051/nss/2015034.

- Schröter M, Berbés-Blázquez M, Albert C, Hill R, Krause T, Loos J, Mannetti LM, Martín-López B, Neelakantan A, Parrotta JA. 2023. Science on ecosystems and people to support the Kunming-Montreal global biodiversity framework. Ecosyst People. 19(1):2220913. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2023.2220913.

- Scoratto J, Pires DP, Friese S. 2020. Thematic content analysis using ATLAS. ti software: potentialities for researchs in health. Revista Brasileira De Enfermagem. 73(3):73. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0250.

- Shinn JE. 2017. Toward anticipatory adaptation: transforming social-ecological vulnerabilities in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Geographical J. 184(2):1–13. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12244.

- Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. 2009. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. London: Sage.

- Thetsane RM. 2019. Local community participation in tourism development: the case of Katse Villages in Lesotho. Athens J Tour. 6(2):123–140. doi: 10.30958/ajt.6-2-4.

- Tuulentie S, Halseth G, Kietäväinen A, Ryser L, Similä J. 2019. Local community participation in mining in Finnish Lapland and Northern British Columbia, Canada – Practical applications of CSR and SLO. Resour Policy. 61:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.01.015.

- van Noorloos F, Kaag M, Zoomers A. 2014. Transnational land investment in Costa Rica: tracing residential tourism and its implications for development.

- Vogel C, Raeymaekers T. 2016. Terr (it) or (ies) of peace? The Congolese mining frontier and the fight against “conflict minerals”. Antipode. 48(4):1102–1121. doi: 10.1111/anti.12236.

- West P, Igoe J, Brockington D. 2006. Parks and peoples: the social impact of protected areas. Annu Rev Anthropol. 35(1):251–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123308.

- Wieckardt CE, Koot S, Karimasari N. 2022. Environmentality, green grabbing, and neoliberal conservation: the ambiguous role of ecotourism in the green life privatised nature reserve, Sumatra, Indonesia. J Sustain Tour. 30(11):2614–2630. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1834564.

- Wijsman K, Berbés-Blázquez M. 2022. What do we mean by justice in sustainability pathways? Commitments, dilemmas, and translations from theory to practice in nature-based solutions. Environ Sciamp Policy. 136:377–386.

- Woodhouse P. 2012. New Investment, Old challenges. Land deals and the water constraint in African agriculture. J Peasant Stud. 39(3/4):777–794. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.660481.

- Yamane T. 1967. Statistics: an introductory analysis. 2nd ed. (NY): Harper and Row.

- Yurco K, King B, Young KR, Crews KA. 2017. Human-wildlife interactions and environmental dynamics in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Soc Nat Resour. 30(9):1112–1126. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2017.1315655.

- Zoomers A, Kaag M. 2014. The global land grab: beyond the hype. London: Zed Books.